1. Background

Managed competition plays an important role in the healthcare system of several countries, such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland (Enthoven, Reference Enthoven1993; Enthoven and van de Ven, Reference Enthoven and van de Ven2007; Van de Ven et al., Reference Van de Ven, Beck, Buchner, Schokkaert, Schut, Shmueli and Wasem2013). Based on the theory of managed competition, health insurers function as the prudent purchasers of care on behalf of their enrollees (Bes, Reference Bes2018; Boonen and Schut, Reference Boonen and Schut2011; Enthoven and van de Ven, Reference Enthoven and van de Ven2007). Health insurers should negotiate each year with healthcare providers about the price, quantity, and quality of care (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Curfs, Groenewegen and de Jong2017; Stolper et al., Reference Stolper, Boonen, Schut and Varkevisser2019). As health insurers compete with each other in the health insurance market, it is expected that they have an incentive to offer an attractive health insurance policy. Health insurers are therefore expected to be striving for lower prices and higher quality of care during the negotiations with healthcare providers (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Curfs, Groenewegen and de Jong2017; Enthoven, Reference Enthoven1993; Stolper et al., Reference Stolper, Boonen, Schut and Varkevisser2019). In practice, however, from the Dutch experience, it appears that in these negotiations, it is mainly the price and quantity of care that play a role. Quality considerations play only a minor role (Stolper et al., Reference Stolper, Boonen, Schut and Varkevisser2019).

Managed competition has played a role in Dutch healthcare, the focus of this study, since the introduction of the Health Insurance Act (HIA) in 2006 (Van de Ven and Schut, Reference Van de Ven and Schut2008). Since then, basic health insurance has been obligatory for everyone who legally lives or works in the Netherlands (Van de Ven and Schut, Reference Van de Ven and Schut2008; Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). Everyone aged 18 and above contributes to the cost of healthcare through premiums, contributions, and taxes (Van de Ven and Schut, Reference Van de Ven and Schut2008; Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). Citizens are free to choose between different health insurance policies offered by private health insurers (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). The government determines the content of the basic health insurance package, which includes many necessary medical treatments, medicines, and aids (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). Although there is a legal requirement to offer the same general cover in every basic health insurance policy, the premiums and conditions may differ. Health insurers are free to contract, selectively, with healthcare providers. They can offer health insurance policies with restrictive conditions that are usually offered at a lower premium and which, mostly, do not fully reimburse care from non-contracted providers.

The introduction of the HIA meant a new role and a change of tasks for health insurers. In this model of regulated competition, health insurers should not only ensure that costs are paid but also act as efficient, customer-oriented directors of care. However, they are obliged to accept everyone for the basic health insurance regardless of their health status or other characteristics (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). In addition, the health insurer has been assigned significant responsibility for the quality, accessibility, and affordability of care. Furthermore, health insurers have a duty of care, meaning that their enrollees have access to all care from the basic health insurance package within a reasonable time and travelling distance (Zorginstituut Nederland, 2023). Furthermore, health insurers are expected to provide good information to their enrollees on policies, costs, reimbursements, and waiting times for care and support (NZa, 2023).

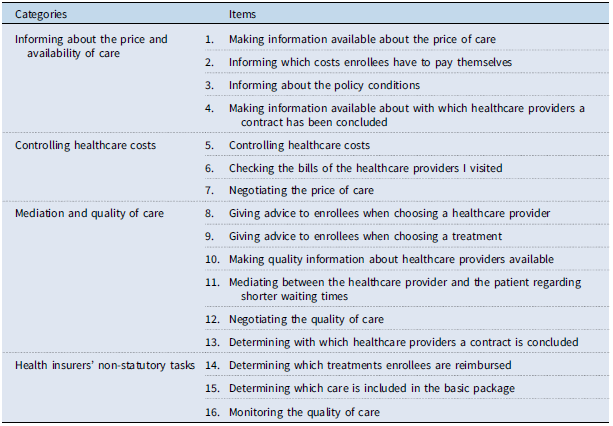

Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015) divided various tasks undertaken by health insurers into three statutory categories (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). These are ‘controlling healthcare costs’, the ‘mediation and quality of care’, and ‘informing about the price and availability of care’ (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). In addition, a fourth category, ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’, has been assigned, which includes tasks that health insurers do not actually have, according to the HIA, but which could be potential tasks of health insurers. The study has indicated that there are misconceptions among enrollees about the current tasks of Dutch health insurers (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). It was found that the tasks of insurers, as stated in the HIA, are not always in line with the expectations of their tasks according to enrollees (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). In addition, enrollees may feel that the tasks of the insurer are not always carried out (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015).

These mismatches between the performance of tasks by health insurers and the expectations and experiences of enrollees may be related to trust in health insurers. The most used definition of trust found in the healthcare literature is ‘the optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the truster believes the trustee will care for the truster’s interests’ (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). Trust is one of the key elements for enabling the social licence to operate (SLO) (Boutilier and Thomson, Reference Boutilier and Thomson2011; Gehman et al., Reference Gehman, Lefsrud and Fast2017; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015; Wilburn and Wilburn, Reference Wilburn and Wilburn2011). SLO can be defined as a contractarian basis for the legitimacy of a company’s specific activity or project (Demuijnck and Fasterling, Reference Demuijnck and Fasterling2016). The trust of enrollees in health insurers is vital for the insurers’ SLO as purchasers of healthcare (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel and de Jong2012; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). Nevertheless, different studies have shown that trust among the Dutch enrollees in health insurers is low (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel and de Jong2012; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015; Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, Brabers and Jong2022).

The effective purchasing of care by health insurers may be hampered when public trust in health insurers is low (Boonen and Schut, Reference Boonen and Schut2009; Varkevisser and Schut, Reference Varkevisser and Schutn.d). Low trust in the health insurer may result in people being less inclined to choose policies with restrictive conditions. In this type of health insurance policy, the health insurer chooses, through selective contracting, which healthcare providers enrollees can receive treatment from without having to pay a co-payment, in addition to the mandatory deductible. But with low trust in their health insurer, enrollees may not feel that health insurers are contracting the best healthcare providers for them. In addition, low trust plays a negative role in the willingness to receive healthcare advice from the health insurer (van der Hulst et al., Reference Van der Hulst, Brabers and de Jong2023). Both policies with restrictive conditions and healthcare advice are instruments that may enable health insurers to steer enrollees to preferred providers. If these instruments cannot be used, this could lead to a weakening of the bargaining position of health insurers towards healthcare providers and may result in health insurers being restrained in their ability to steer on cost and/or quality of care.

This study focuses on the extent to which enrollees’ perceptions of the tasks of health insurers are related to their trust in them. This research will provide more clarity on the reasons why trust in health insurers in the Netherlands is low and thus reveal opportunities to increase this trust. The aim of this study is, therefore, to examine whether a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations about the health insurer’s tasks and their perceptions of what they actually do may be a reason why trust in health insurers in the Netherlands is low. While our study primarily examines the Dutch situation, it may also offer valuable insights for other countries with healthcare systems based on managed competition. The main research question of this study is: ‘What is the relationship between enrollees’ perceptions of the tasks of health insurers and enrollees’ trust in them?’ To answer this question, we formulated three subsidiary research questions. First, what is the relationship between any mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and those as defined in the HIA and their trust in health insurers? Second, what is the relationship between any mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed and their trust in health insurers? And, third, what is the influence of the importance enrollees attach to certain tasks on the relationship between any mismatch between enrollees’ expectations and what they see is actually performed and their trust in health insurers?

1.1 Hypotheses

Based on the expectation that enrollees who believe that health insurers are not performing their expected tasks have less trust in them compared to enrollees who do (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015), we hypothesise:

H1: Enrollees who show a higher degree of mismatch between their expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks as defined in the HIA will have less trust in health insurers.

Research has also shown that the tasks expected of an insurer according to enrollees are not always in line with those they believe are actually performed (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). This is because enrollees’ perception of the health insurer’s actual performance is based on personal experience and information obtained either from others and through the media (Van der Schee, Reference Van der Schee2016). Enrollees’ views on the health insurers’ performed tasks are expected to influence their trust. More than the insurers’ objective purchasing behaviour, perception influences the level of trust in the insurer (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019). If the perception is not in line with the expectation about the health insurer, then we expect this to influence enrollees’ trust in them. We expect that if there is a higher degree of mismatch between the enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks they believe are actually performed, then enrollees will have less trust in health insurers. This results in the following hypothesis:

H2: Enrollees who show a higher degree of mismatch between their expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed will have less trust in health insurers.

As everyone has different norms and values, enrollees’ opinions on the importance of tasks can differ. As a result, the interest in specific topics or activities can differ per person (de Groot et al., Reference De Groot, Bondy and Schuitema2021). Enrollees may feel that, for a certain task, there is a mismatch between what the health insurer does according to them versus what they expect. If they, in addition, consider that task to be important, then trust may be affected more than for less important roles. This results in the following hypothesis:

H3: The more important enrollees consider a task, the higher the impact of the mismatch between their expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed on trust in health insurers.

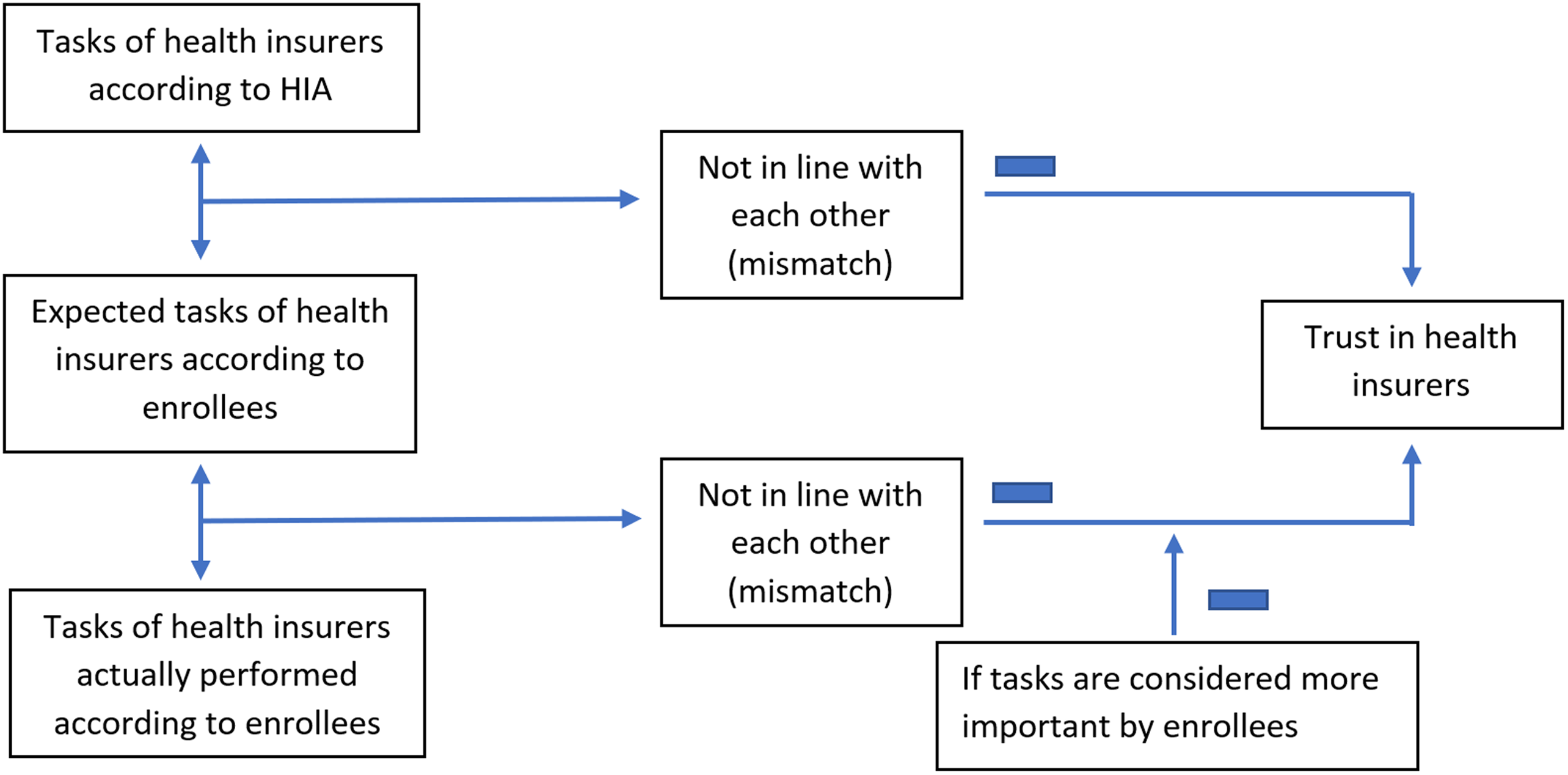

The hypotheses are visualised in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1. When the factors on the left are not in line with each other, this has a negative influence on trust in health insurers. The minus sign indicates, therefore, a negative relationship.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

Data were collected using the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, an access panel managed by Nivel (the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research) (Brabers and de Jong, Reference Brabers and de Jong2022). The panel collects citizens’ opinions, knowledge, expectations, and experiences regarding healthcare. At the time of the study, November 2021, the panel had approximately 11,500 members from the general Dutch population aged 18 and over. Their background characteristics, such as age, gender, education level, and self-reported health status, were recorded at the start of their membership. People can join the panel by invitation only. Data have been assessed, processed, and pseudonymised in accordance with the panel’s privacy policy, which corresponds to the General Data Protection Regulation.

Under Dutch law, approval of a medical ethics committee is not required to conduct research with the panel (Brabers and de Jong, Reference Brabers and de Jong2022). Informed consent is obtained from the participants to the panel as follows: an intended participant receives an invitation to participate in the panel, including information about the purpose, scope, method, and use of the panel. Based on that information, a participant can give permission to participate in the panel. This is a written consent that since 2020 can also be given digitally. Participants are asked to complete a questionnaire a few times a year. Prior to each survey, the participants receive information on the subject and the length of the survey. Participation is voluntary, and members are not obliged to participate in the survey or answer any questions in the survey. They can stop their membership at any time without giving a reason.

2.2 Questionnaire

In November 2021, a questionnaire was sent to a sample of 1,500 members of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel. This was a representative sample of the adult population in the Netherlands with regard to age and gender. The questionnaire was developed by three of the authors of this article (FH, AB, and JDJ), who each have expertise on this research topic and in conducting research based on surveys. A draft version of the questionnaire was submitted to the programme committee of Nivel’s Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, who had the opportunity to provide feedback. The committee consists of representatives from different healthcare stakeholders, including the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS), the Dutch Consumers Association, and ‘Zorgverzekeraars Nederland’, the umbrella organisation of health insurers. The questionnaire could be filled in online or by post, depending on personal preference. The panel members could fill in the questionnaire from the 4th of November until the 1st of December 2022. Completing the questionnaire should have taken respondents approximately 15–20 minutes. A maximum of two reminders were sent to respondents who had not yet completed the online questionnaire and one reminder to those who had not yet completed the paper questionnaire. The questionnaire was completed by 837 panel members, a response rate of 56 per cent. The online questionnaire was completed by 698 respondents (83 per cent) and the paper questionnaire by 139 respondents (17 per cent, most of them elderly).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Trust in health insurers

Trust in health insurers was measured using the Health Insurer Trust Scale (HITS), a validated scale to measure patients’ trust in health insurers, developed by Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Hall, Dugan, Kidd and Levine2002) (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Hall, Dugan, Kidd and Levine2002). This assumes that trust in a health insurer is based on four dimensions: (1) fidelity – caring for the subject’s interests or welfare; (2) competence – making correct decisions and avoiding mistakes; (3) honesty – telling the truth and avoiding intentional falsehoods; and (4) confidentiality – the proper use of sensitive information (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Hall, Dugan, Kidd and Levine2002). We used the validated Dutch translation of this scale for this study (Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Delnoij and Groenewegen2007). The scale consists of 11 items (Table 1). The 11 questions of the HITS were asked with respect to health insurers in general. The response categories for every item are completely agree (score 5), agree (score 4), neutral (score 3), disagree (score 2), and completely disagree (score 1). The scoring is reversed in the case of a negative question (items 2, 4–7, and 9). Trust is measured by the sum of the 11 item scores ranging from 11 to 55. A higher score indicates more trust. A score has only been calculated if the respondents have replied to all the statements on the scale. The scores of respondents who completed the scale partially (n=14) or not at all (n=60) were converted to missing scores.

Table 1. Health Insurer Trust Scale (HITS) (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Hall, Dugan, Kidd and Levine2002)

2.3.2 The tasks of health insurers

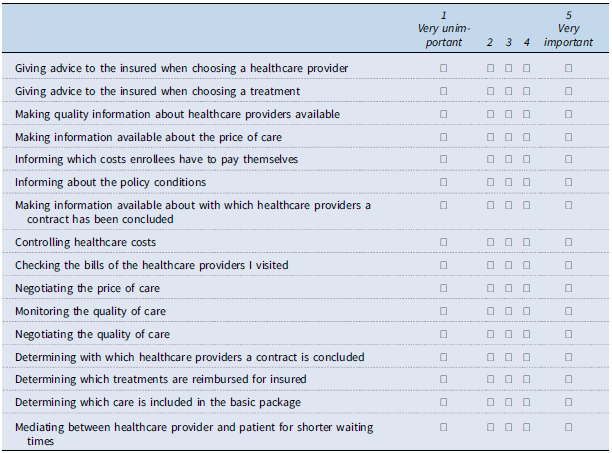

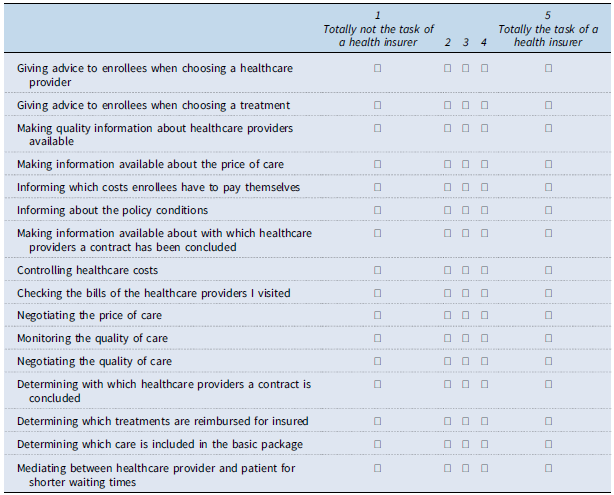

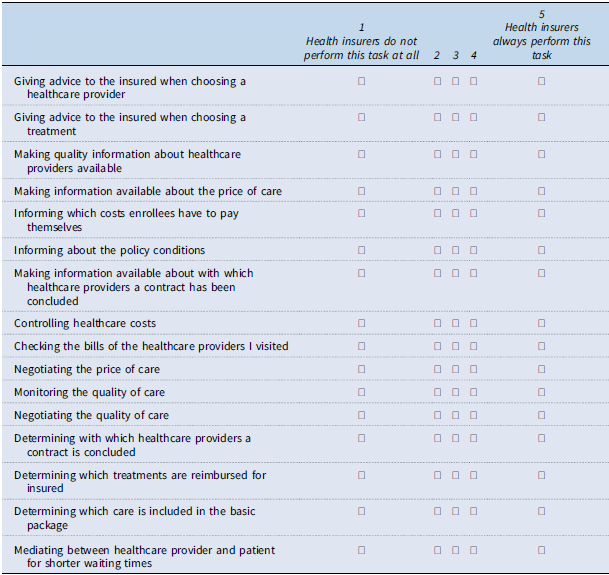

Three questions were asked in order to gain insight into the views on the tasks of health insurers. Each question had to be answered for the 16 different tasks presented in Table 2. As the tasks may be seen as shared tasks between the health insurer and other parties within the healthcare sector, such as healthcare providers or the government, a 5-point Likert scale was applied for the answer options for each question to include this aspect.

Table 2. List of proposed tasks of the health insurer derived from Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015)

First, the respondents were asked to indicate to what extent health insurers have to perform these tasks. For these questions, a score of 1 on the 5-point Likert scale meant ‘totally not the task of a health insurer’, while a score of 5 meant ‘totally the task of a health insurer’.

Second, the respondents were asked to indicate to what extent health insurers actually perform these tasks. For these questions, a score of 1 on the 5-point Likert scale meant ‘health insurers do not perform this task at all’, while a score of 5 meant ‘health insurers always perform this task’.

Third, the respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they think it is important that health insurers perform these tasks. For these questions, a score of 1 on the 5-point Likert scale meant they thought it was ‘very unimportant’, while a score of 5 meant ‘very important’.

The 16 tasks presented in Table 2 were derived from the study of Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015) (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). The list of tasks in the study of Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015) was drawn up, based on discussions with the Dutch Healthcare Authority, by three Nivel researchers, including two of this study’s authors, AB and JDJ. The list consists of tasks that, according to the HIA, must actually be performed and of those tasks that do not have to be performed. In order to keep the number of questions manageable for the respondents in the current study, the number of tasks was reduced from 26 to 16 tasks, as presented in Table 2. The choice of these 16 tasks resulted from discussions between three researchers (FH, AB, and JDJ), all of whom have expertise in the Dutch healthcare system. These tasks were divided in four categories, as was also done by Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015) (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015). These four categories are (1) informing about the price and availability of care, (2) controlling healthcare costs, (3) mediation and quality of care, and (4) health insurers’ non-statutory tasks. Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the reliability of the categories used for this study (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951). All categories met the requirement of an acceptable alpha value of 0.6 or higher (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Mo and Sun2012).

2.3.3 Mismatch scores

For examining the first research question, we investigated the degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks of the insurer as defined in the HIA. This was calculated by subtracting the score of the extent to which, according to enrollees, health insurers have to perform a task from the score of the extent to which, according to the HIA, it is a task of the insurer.

The scores to the question about the extent to which, according to enrollees, an item is a task of the insurer were added up for each category. After that, the mean score of each category was calculated. In case of a missing value, a respondent was still included if they completed at least 66 per cent of the questions of this category. In this case, the mean score was calculated by adding up the completed scores and dividing by the number of questions the respondent completed.

We then determined the extent to which, according to the HIA, an item is a task of the insurer. The items in the first three categories of Table 2 (informing about the price and availability of care, controlling healthcare costs, mediation and quality of care) achieved a score of 5, meaning that this, according to the HIA, was a task of the insurer. The items in the last category of Table 2 (health insurers’ non-statutory tasks) achieved a score of 1, meaning that this, according to the HIA, was not a task of the insurer.

In summary, this meant, for example, for the category ‘informing about the price and availability of care’, the following:

-

Degree of mismatch =

$ {{\rm{A}}_i} - {{\rm{\;}}{{\sum {B_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{C}}_i}}}}$

, where:

$ {{\rm{A}}_i} - {{\rm{\;}}{{\sum {B_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{C}}_i}}}}$

, where:-

○ Ai = The extent to which the category is among the tasks of the insurer according to the HIA = 5 (or = 1 for non-statutory tasks)

-

○ ΣBi = Sum of the scores of the extent to which health insurers have to perform the tasks of this category according to enrollees

-

○ Ci = The number of questions in this category that the respondent has filled in

-

A greater difference between Ai and

![]() ${{\sum {B_i}}}\over{{{C_i}}}$

meant a higher mismatch score. This means that a mismatch score could potentially be negative. For the analyses, the mismatch scores were converted into absolute values. This was carried out because the influence of the presence of a mismatch on trust was examined, without giving any direction.

${{\sum {B_i}}}\over{{{C_i}}}$

meant a higher mismatch score. This means that a mismatch score could potentially be negative. For the analyses, the mismatch scores were converted into absolute values. This was carried out because the influence of the presence of a mismatch on trust was examined, without giving any direction.

Next, for the second research question, we examined the degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see as actually performed. This was calculated by subtracting the score, according to enrollees, of the extent to which a task is actually performed from the score of the extent, according to enrollees, to which an item is a task of the insurer.

The scores of the questions relating to the extent, according to enrollees, to which a task is actually performed, and the extent to which, according to enrollees, an item is a task of the insurer were added up for each category. After that, the mean score of each category was calculated. In case of a missing value, a respondent was still included if they completed at least 66 per cent of the questions from this category. In that case, the mean score was calculated by adding up the completed scores and dividing by the number of questions the respondent completed.

In summary, this meant the following:

-

Degree of mismatch

$ = {\rm{\;}}{{{\sum {D_i}}}\over{{{E_i}}}} - \;{{{\sum {F_i}}}\over{{{G_i}}}},\;$

where:

$ = {\rm{\;}}{{{\sum {D_i}}}\over{{{E_i}}}} - \;{{{\sum {F_i}}}\over{{{G_i}}}},\;$

where:-

○ ΣDi = Sum of the score of the extent, according to enrollees, to which health insurers have to perform the tasks of this category.

-

○ Ei = Number of questions in this category that the respondent has filled in.

-

○ ΣFi = Sum of the score of the extent, according to enrollees, to which health insurers actually perform the tasks of this category.

-

○ Gi = The number of questions in this category that the respondent has filled in.

-

A greater difference between

![]() ${{\sum {D_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{E}}_i}}}$

and

${{\sum {D_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{E}}_i}}}$

and

![]() ${{\sum {F_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{G}}_i}}}$

means a higher mismatch score. Again, the mismatch scores were converted into absolute values because the influence of the presence of a mismatch on trust was examined, without giving any direction.

${{\sum {F_i}}}\over{{{{\rm{G}}_i}}}$

means a higher mismatch score. Again, the mismatch scores were converted into absolute values because the influence of the presence of a mismatch on trust was examined, without giving any direction.

2.3.4 The importance, according to enrollees, of the task

With regard to the third research question, the respondents were asked to indicate to what extent the respondent thinks that it is important that health insurers perform these tasks. This was measured to include in the analysis what an enrollee attaches more value to. For these questions, a 5-point Likert scale was used (‘very unimportant’ = score 1; ‘very important’ = score 5).

For each category, the scores of the questions about the extent to which the respondent thinks that it is important that health insurers perform specific tasks were added up. After that, the mean score of each category was calculated. A higher score meant that this task was considered by enrollees as more important. Also here, where there was a missing value, a respondent was still included if he completed at least 66 per cent of the questions of this category. In that case, the mean score was calculated by adding up the completed scores and dividing by the number of questions the respondent completed.

2.3.5 Background variables

The background variables that are known from the panel members, and are included in the analyses, concern: age (continuous); gender (0 = male, 1 = female); educational level (1 = low – that is none, primary school, or pre-vocational education, 2 = middle – that is secondary or vocational education, 3 = high – that is professional, higher education, or university); self-reported health status (1 = bad/fair, 2 = good, 3 = very good/excellent); and self-reported use of care (1 = none/very little, 2 = little, 3 = much/very much).

2.3.6 Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the characteristics of the respondents. Multivariate regression analyses were used to test if, for all four categories of tasks, both mismatch scores were significantly related to trust in the health insurer. In these analyses, the relevant mismatch score was the independent variable, while trust was the dependent variable. Gender, age, education level, self-reported general health of the respondent, and the self-reported amount of use of care were used as control variables. This is because some other studies found associations of these characteristics with trust (Bailey and Leon, Reference Bailey and Leon2019; Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dugan, Zheng and Mishra2001; Li and Fung, Reference Li and Fung2013). To examine the third hypothesis, we examined, for all four categories, the interaction effects between the mismatch – as used in H2 – and the importance someone attaches to the tasks. Trust was once more the dependent variable for these analyses. For all regression analyses, age was centred around the mean. In addition, for the regression analysis related to the examination of hypothesis 3, the mean importance scores were subtracted by one. This was carried out so that the intercept of these models relates to someone of average age with a mean importance score per category of 1. A significance level of 5 per cent (p ≤ 0.05) was maintained for these analyses. All analyses were performed using STATA version 16.1.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

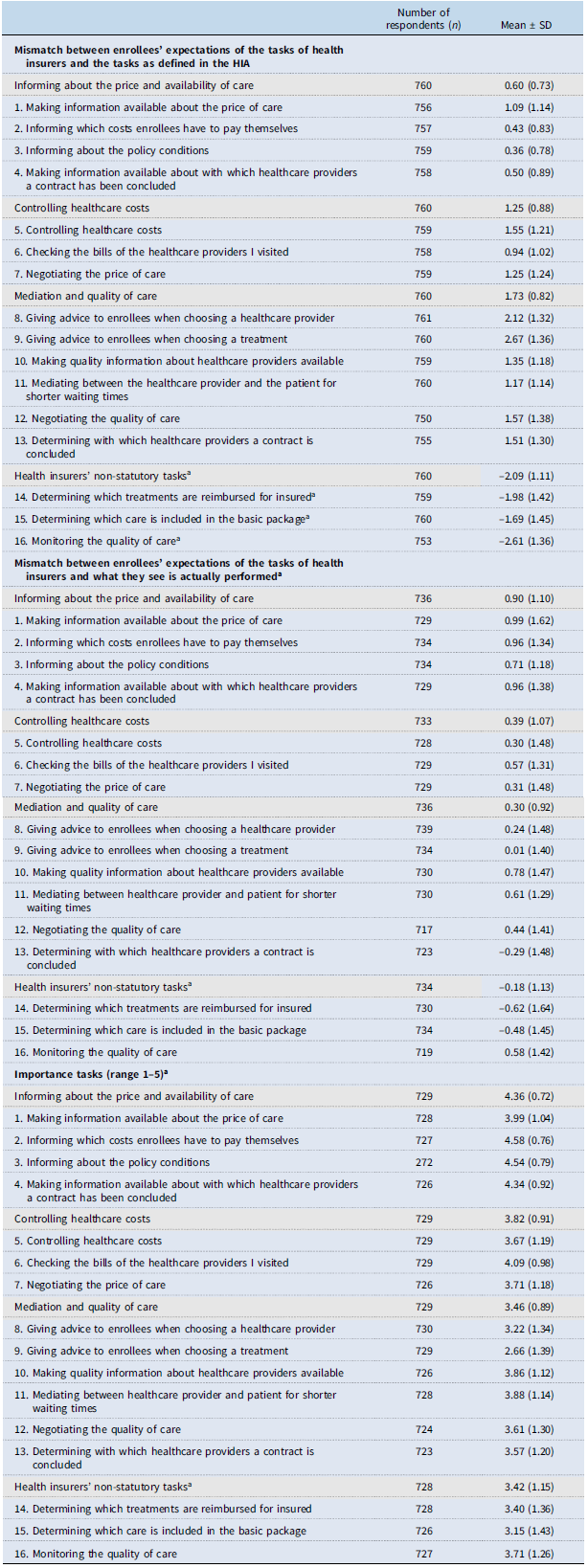

The questionnaire was sent to 1,500 members of the Dutch Healthcare Consumer Panel. After sending the reminders, 837 questionnaires were received (56 per cent). Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the respondents, the mean score measured on the Health Insurer Trust Scale, and the generated mismatch and importance scores of the categories of tasks. The mean mismatch scores on all individual tasks are shown in Appendix A.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the respondents

a Education: Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Middle = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher education or university.

b For regression analyses, only absolute values of the mismatch scores were used, but this table shows the actual values to provide insight into the direction of the mismatches.

c A higher score means more importance: scores range between 1 (very unimportant) and 5 (very important).

3.1.1 Mismatch scores

Looking at the mean mismatch scores on all individual tasks (Appendix A), it is apparent that advice on choosing a healthcare provider or treatment is something that enrollees least expect from the health insurer. Enrollees must expect the health insurer to inform them about policy conditions and the costs insured have to incur. Nevertheless, according to enrollees, the actual performance of the tasks related to providing information on costs, contracting, and prices deviates the most from their expectation of this performance.

3.2 Hypothesis testing

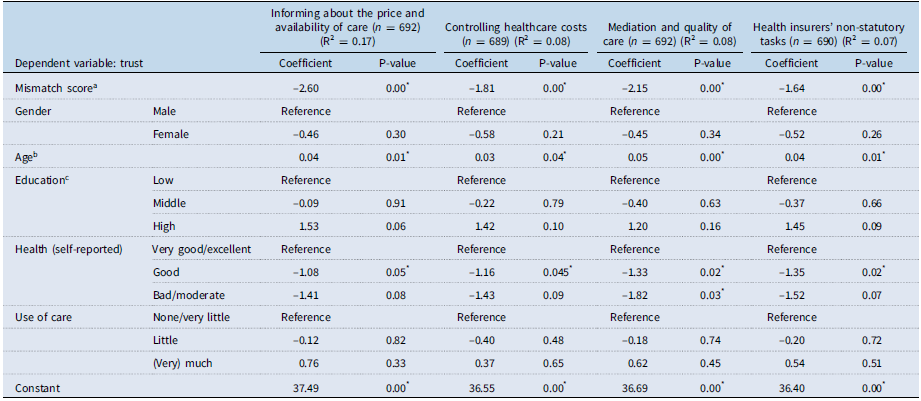

H1: Enrollees who show a higher degree of mismatch between their expectation of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks as defined in the HIA will have less trust in health insurers.

For the categories, ‘controlling healthcare costs’, ‘mediation and quality of care’, and ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’, a significant relationship was found (p = 0.00) (Table 4). For the categories ‘controlling healthcare costs’ and ‘mediation and quality of care’, the negative estimated coefficient indicated that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks of the insurer as defined in the HIA was related to less trust in the health insurer (Table 4). For these two categories, the results are in line with H1.

Table 4. The relationships between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks as defined in the HI and trust in the insurer, examined with regression analysis

* Significant p-value (p < 0.05);

a . Absolute value, ranging between zero (no mismatch) and four (greatest mismatch);

b . Centred around the mean;

c . Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Middle = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher education or university.

The results are not in line with H1, however, for the other two categories. The results for the category, ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’ showed that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks of the insurer, as defined in the HIA, is related to more trust in the health insurer (Table 4). For the category, ‘informing about the price and availability of care’, no significant relationship was found between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks of the insurer as defined in the HIA and trust in the health insurer (p = 0.543) (Table 4).

Furthermore, for all categories, significant relationships were found between trust and the control variables age and self-reported health (Table 4). In general, older enrollees and enrollees in very good or excellent health had more trust in health insurers than younger enrollees and those in good, bad, or moderate health. However, the effect of age on trust in the health insurer was small.

H2: Enrollees who show a higher degree of mismatch between their expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed will have less trust in health insurers.

A significant relationship was found for all four categories (p = 0.000) (Table 5). The negative coefficients mean that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and, according to enrollees, the actual tasks performed was related to less trust in the insurer (Table 5). These results are in line with the second hypothesis.

Table 5. Relationships between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed and trust in the insurer, examined with regression analysis

* Significant p-value (p < 0.05);

a . Absolute value, ranging between zero (no mismatch) and four (greatest mismatch);

b . Centred around the mean;

c . Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Middle = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher education or university.

In addition to this, all categories found significant relationships between trust and the control variables age and self-reported health (Table 5). Older enrollees and enrollees in very good or excellent health had more trust in health insurers than younger enrollees and those in good health. However, also in this analysis, the effect of age on trust in the health insurer was small.

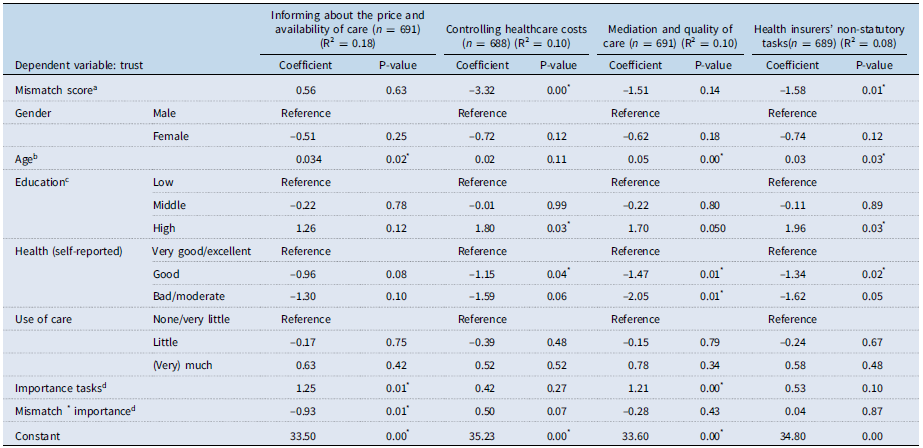

H3: The more important enrollees consider a task, the higher the impact of the mismatch between their expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed on trust in health insurers.

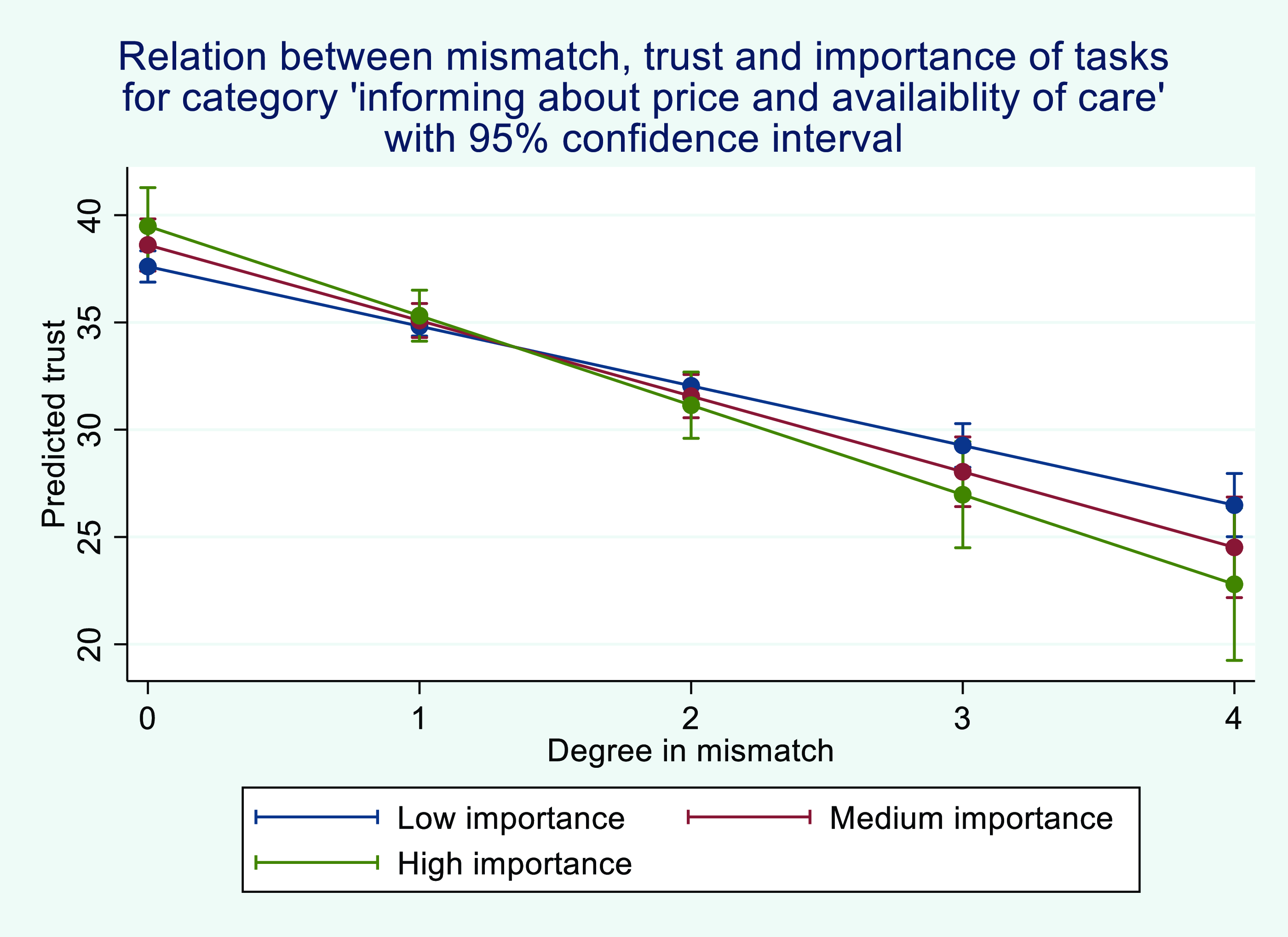

For the category ‘informing about the price and availability of care’, a significant relationship was found for the interaction variable (mismatch * importance) and trust in the insurer (p = 0.01) (Table 6). The negative coefficient means that a mismatch has a more negative effect on trust if a task was seen as more important (Figure 2). For this category, the results are in line with H3. For the categories ‘controlling healthcare costs’, ‘mediation and quality of care’, and ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’, no significant relationship was found for the interaction between importance and the mismatch score on trust (p > 0.05) (Table 6). For these categories, the results do not support H3.

Table 6. The relationships between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and what they see is actually performed, taking into account the importance to enrollees of a task, and trust in the insurer, examined with regression analysis

* Significant p-value (p < 0.05);

a . Absolute value, ranging between zero (no mismatch) and four (greatest mismatch);

b . Centred around the mean;

c . Low = none, primary school, or pre-vocational education. Middle = secondary or vocational education. High = professional higher education or university;

d . Tasks that are important for insurers to perform: scores range between 0 (very unimportant) and 4 (very important), because the scores were calculated minus one for interpretation reasons.

Figure 1. The conceptual model of this study.

Figure 2. The relationship between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks they see actually performed in the category ‘informing about the price and availability of care’, taking into account the importance to enrollees of these tasks. * Low importance = average score on importance minus one time the standard deviation on importance. Medium importance = average score on importance. High importance = average score on importance plus one time the standard deviation on importance.

4. Discussion

We found different relationships between the enrollees’ perception of the tasks of health insurers and their trust in health insurers. In general, we found a relationship between a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations about the tasks of health insurers and their tasks, as stated in the HIA, and trust. Furthermore, we found that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks they see are actually performed was significantly related to less trust in the insurer. Lastly, the interaction between the importance of a task and a mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks they see actually performed was only significantly related to trust for the category ‘informing about the price and availability of care’.

Regarding the first subsidiary research question, the results for the categories ‘controlling healthcare costs’ and ‘mediation and quality of care’ show that the more enrollees think health insurers should not be responsible for these roles, the less trust they have in health insurers. This is in line with our first hypothesis. There may be two reasons why enrollees expect less than what the insurer, according to the HIA, is obliged to do. They may not be aware that this is a statutory duty of the health insurer or they feel it is not a task of the health insurer, either because they do not see its importance or feel it should be a task of another party. It is not clear why a relationship with trust was found for the categories, ‘controlling healthcare costs’ and ‘mediation and quality of care’, but not for ‘informing about the price and availability of care’. A possible explanation may be that enrollees, whether or not they trust health insurers, generally find it appropriate to be well informed about price and accessibility of care. This may be shown by the lower average mismatch score for this category than for the other categories.

For the category, ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’, a mismatch means that enrollees think it should be the health insurers’ role, when according to the HIA, it is not. We found that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers of a health insurer and the tasks of the insurer, as defined in the HIA, is related to more trust in health insurers. This is not in line with our hypothesis, as we expected this mismatch to be related to less trust. We could not indicate causation in this study, but an explanation could be that the relationship is running in the other direction. Enrollees with more trust in health insurers may be more likely to feel that health insurers should perform these tasks. This is because trust is one of the key elements for achieving the SLO (Boutilier and Thomson, Reference Boutilier and Thomson2011; Gehman et al., Reference Gehman, Lefsrud and Fast2017; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015; Wilburn and Wilburn, Reference Wilburn and Wilburn2011).

Regarding the second subsidiary research question, we found in line with our hypothesis 2 that for all categories, a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks enrollees believe are actually performed is related to less trust in the insurer. Literature suggests that enrollees’ perception affects the amount of trust in the insurer (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019). If the perception is not in line with the expectation of the insurer, this leads to unmet expectations, which has a negative effect on trust (Li, Reference Li2008). These results are in line with those of Hoefman et al. (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015).

From Appendix A, it can be seen that especially in the area of information provision, enrollees’ expectations are higher than their experience. A possible explanation is that enrollees are not always well informed about certain aspects of their health insurance. For example, research shows that a large proportion of enrollees are not aware that their insurer does not have a contract with their healthcare provider (Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, 2023). In addition, previous research showed that a large group of enrollees were not aware in advance that they had to make a co-payment when they visited a non-contracted provider (van der Hulst et al., Reference Van der Hulst, Holst, Brabers and de Jong2022). These are signals of possible information deficiencies by health insurers, which we may also see reflected by the higher mismatch scores related to information provision. Future research and policy interventions could focus on improving health insurers’ means of effectively reaching enrollees with this kind of information, as this might also have a positive influence on trust in the health insurer.

Lastly, regarding the third subsidiary research question, our study showed that the greater the importance enrollees attach to health insurers informing them about the price and availability of care, then the greater impact a mismatch between the expected versus the actual information provided has on trust in the health insurer. This is in line with hypothesis 3. The reasons why this effect was found for this category, and not for the other categories, is possibly because receiving information about the price and availability of care is of personal interest for enrollees when they use care. As stated earlier, a higher mismatch score may mean that enrollees feel that they were being poorly informed. This could result in incurring more costs than expected. Enrollees with a more negative experience as the result of poor information will probably see this role as more important. At the same time, their trust in health insurers is affected the most. Nevertheless, for the other categories, no interaction effect was found between importance and this mismatch on trust in the health insurer, which is not in line with our third hypothesis. This may be because any mismatch in these categories is less directly related to a personal negative consequence.

If we consider the characteristics of the respondents, we found that age and health status were positively related to trust in health insurers. In the context of research on reasons why trust in health insurers in the Netherlands is low, our study therefore shows that younger people and people with poorer health are groups on which more attention can be focused in follow-up research on the topic. These findings are in line with literature. Several studies confirm the relationship between age and trust in general by finding that older people are more trusting than younger people (Bailey and Leon, Reference Bailey and Leon2019; Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dugan, Zheng and Mishra2001; Li and Fung, Reference Li and Fung2013). Furthermore, the study of Goold et al. (Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006), which specifically focused on predictors of trust in health insurers, had found an association between health status and trust in health insurers (Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006).

Here, we examined the presence of a mismatch without giving the direction of this mismatch. The focus was specifically on whether a deviation from the expectation of the health insurers’ tasks is related to trust. However, Appendix A may provide some more insight into the direction of each task’s mismatches by showing whether the mean of the calculated mismatches is positive or negative. It shows that the mean mismatch scores are mostly positive and that particularly negative mismatch scores can be seen for the category ‘health insurers’ non-statutory tasks’. However, with respect to the mismatch between enrollees’ expectations and the tasks as defined in the HIA, it should be noted that the negative mean mismatch score for this category is due to defining Ai = 1 in the formula, whereas Ai is defined as 5 for other categories. As explained in the Methods section, this is because a score of 1 indicates it is not a task of the health insurer, whereas a score of 5 indicates it is. Future research could focus on whether the relationship between trust and a mismatch between task performance and expectations is different when enrollees think health insurers fall short in their tasks than when they think health insurers do more than they would prefer. Furthermore, conducting qualitative research, such as interviews with enrollees, can provide additional insight into why enrollees’ trust in health insurers is generally low and can verify whether enrollees cite their perceptions of task performance as one of the underlying aspects.

Mismatches that result in lower trust in health insurers may have implications for the healthcare system. For example, people may not choose policies with selective contracting if there is a lack of trust in the relationship between the enrollee and insurer (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel, Curfs, Groenewegen and de Jong2013; Boonen and Schut, Reference Boonen and Schut2011). In addition, a low level of trust plays a negative role in the willingness to receive healthcare advice from the health insurer (van der Hulst et al., Reference Van der Hulst, Brabers and de Jong2023). Policies with selective contracting and healthcare advice are both instruments that enable health insurers to direct their enrollees to preferred providers. The ability to channel enrollees is of crucial importance if health insurers are to act as prudent healthcare purchasers (Boonen and Schut, Reference Boonen and Schut2011; Pauly, Reference Pauly1987; Sorensen, Reference Sorensen2003; Wu, Reference Wu2009). If these instruments cannot be used to channel enrollees, then the bargaining power of health insurers over healthcare providers may weaken. As a result, health insurers will be restrained in their ability to influence costs and/or the quality of care.

Enrollees’ idea of the actual role of an insurer is formed by personal experience, information from others, and information through various media (Van der Schee, Reference Van der Schee2016). A potential solution to reduce misconceptions, therefore, could be through providing better information about the roles the health insurer has in the healthcare system and the importance of these roles. Both health insurers themselves and also the government may need to improve information about the insurer’s roles. This is evidenced, for example, by the study of Potappel et al. (Reference Potappel, Victoor, Curfs and de Jong2018), which found that more than half of the enrollees are not aware that health insurers make price information about treatments publicly available (Potappel et al., Reference Potappel, Victoor, Curfs and de Jong2018). Furthermore, as can be seen in Appendix A, the highest mean score of the mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks as defined in the HIA was found for ‘Giving advice to enrollees when choosing a treatment’. This is in line with previous research, which already showed that many enrollees do not yet seem to be aware of this role of the health insurer (Holst et al., Reference Holst, van der Hulst, Brabers and de Jong2022). In our study, we found that lower expectations about tasks within the category ‘mediation and quality of care’ is negatively associated with the amount of trust in the health insurer. This may indicate that it is important for health insurers and the government to emphasize this advisory role, as it can serve as a means of increasing trust in the health insurer. Future research could focus on the current state of information provision about the health insurer’s roles and how best to reach enrollees with this type of information.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is that this is one of the first studies in this area. There is not much literature available on public trust in health insurers. The insight this study offers into this relationship is important in order to achieve a better understanding of where the problem of trust in health insurers comes from. In addition, a strength of this study is that a validated questionnaire was used to measure trust. Furthermore, the data were collected both on paper and online. This makes it accessible for most respondents, even those with low digital skills, to participate in this study, and it reduces non-response bias (Berg, Reference Berg2005). This is demonstrated by the fact that paper questionnaires were, for the most part, completed by the elderly, making it likely this group would not have participated if the questionnaire had only been offered online.

A limitation of this study is that the respondents were not completely representative for the Dutch population of 18 years and older, based on age, gender, and educational level. Our respondents are relatively older and more highly educated compared to the general Dutch population (CBS, 2021; CBS, 2022). This could affect the level of trust we measured, as several studies have found a relationship between age or level of education with trust (Bailey and Leon, Reference Bailey and Leon2019; Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dugan, Zheng and Mishra2001; Li and Fung, Reference Li and Fung2013). However, our regression results are not expected to have been affected, as all subgroups are sufficiently large to perform association analyses. Another limitation is that our data were obtained using a cross-sectional study design, and as such, this study cannot demonstrate causal relationships. A third limitation is the low R² values of our regression models. However, our research focuses on one specific explanation for low trust in health insurers while trust is a complex construct determined by multiple influences. As the low R² values indeed suggest other variables and explanations also play a role, further research could aim to identify and understand these additional factors. A further limitation is that in this study, we did not look at the experience people have with their current health insurer, while this could influence both trust and the mismatch. We were not able to include this, as we did not have background information on this.

Lastly, a limitation is that there was no officially validated questionnaire used to measure the perceptions of insurer tasks. However, the original questionnaire derived from Hoefman et al. (Reference Hoefman, Brabers and De Jong2015) was based on discussions with the Dutch Healthcare Authority. Furthermore, the involvement of the programme committee of Nivel’s Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, which includes representatives from different healthcare stakeholders who had the opportunity to provide feedback on the questionnaire, increases its validity. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the reliability of the task categories used for this study, which showed all categories met the requirement of an acceptable alpha value of 0.6 or higher (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Mo and Sun2012).

5. Conclusion

This study confirms that mismatches regarding the tasks of the health insurer are related to trust. For the categories ‘controlling healthcare costs’ and ‘mediation and quality of care’, a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks of the insurer as defined in the HIA is related to less trust. Furthermore, this study shows that a higher degree of mismatch between enrollees’ expectations of the tasks of health insurers and the tasks they see actually performed is related to less trust in the health insurer. These results emphasise the importance of reducing enrollees’ misconceptions as trust in health insurers is necessary to fulfil their role as purchasers of care. Our study focuses on the Dutch situation but also provides valuable insights for other countries with healthcare systems based on managed competition. By understanding and addressing the misconceptions about the tasks of the insurer in the healthcare system, policymakers or other stakeholders can enhance trust in health insurers, potentially leading to a more effective healthcare system. In this context, our study highlights the importance of clear communication about the responsibilities of health insurers in the healthcare system.

Data availability

The data may only be used under the conditions laid down in the privacy regulations of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel. Therefore, the dataset is available on request from Prof. Judith D. de Jong (j.dejong@nivel.nl), project leader of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel, or the secretary of this panel (consumentenpanel@nivel.nl). The Dutch Health Care Panel has a programme committee, which supervises the processing of the data of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel and decides about the use of the data. This programme committee consists of representatives of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, the Health Care Inspectorate, Zorgverzekeraars Nederland (Association of Health Care Insurers in the Netherlands), the National Health Care Institute, the Federation of Patients and Consumer Organisations in the Netherlands, the Dutch Healthcare Authority and the Dutch Consumers Association. All research conducted within the Consumer Panel has to be approved by this programme committee. The committee assesses whether a specific research fits within the aim of the Consumer Panel, which is to strengthen the position of the healthcare user.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Dutch Health Care Consumer Panel who filled out the questionnaire.

Financial support

The data collection of this study was funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A. The mean mismatch scores on all individual tasks

Appendix B. Questionnaire about the tasks of the health insurer (translated)

We would like to ask you questions about the tasks of health insurers. These questions seem very similar. However, they are different. Please read the questions carefully and answer them all.

Table B1. Below are several tasks. To what extent do you think these are tasks that health insurers have to perform? Please indicate this per task

Table B2. To what extent do you think health insurers actually perform these tasks? Please indicate this per task

Table B3. To what extent do you think it is important that health insurers perform these tasks? Please indicate this per task