1. Introduction

Industries that produce and market harmful consumer products are a major driver of the rising global burden of preventable death and disease (Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). Globally, the products and practices of the tobacco, ultra-processed food and drink, and alcohol industries are reportedly responsible for around 9.1 million, 3.1 million, and 2.4 million deaths, respectively (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network 2019; Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). Accordingly, these three industries alone likely account for over one quarter of preventable deaths worldwide (Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). Considerable public health concern has also been raised about the substantial health burden of many other widely marketed harmful consumer products, including gambling and electronic cigarettes (Abbott Reference Abbott2017; Besaratinia and Tommasi Reference Besaratinia and Tommasi2019).

Most policy efforts to address the burden of preventable death and disease attributable to harmful consumer product industries, ie. ‘industrial epidemics’ (Majnoni d’Intignano Reference Majnoni d’Intignano1995; Jahiel and Babor Reference Jahiel and Babor2007), have tended to focus on industry-specific measures (Lee and Freudenberg Reference Lee and Freudenberg2022). Key examples include product and packaging regulations, marketing restrictions, and taxes levied on specific products. These policy actions are important, and, in some cases, have substantially improved population health outcomes (Peruga et al., Reference Peruga, Lopez, Martinez and Fernandez2021). Nevertheless, the limited success in addressing industrial epidemics highlights how such epidemics are shaped to a considerable degree by government policies and regulations that extend beyond the traditional boundaries of public health policy (Friel et al., Reference Friel, Collin, Daube, Depoux, Freudenberg, Gilmore, Johns, Laar, Marten, McKee and Mialon2023).

Given the above considerations, this paper focuses on competition regulation and its relationship with industrial epidemics, a topic which has received relatively little attention in the public health literature. This is an important research gap because, as we argue below, the influence of competition regulation on health outcomes is likely considerable. Broadly speaking, competition regulation plays a central role in determining which firms are legally allowed to build scale and power (eg. via merger control), as well as what these firms can do with this power according to the rules of the market (eg. through the regulation of abuses of market power or dominance) (Paul Reference Paul2020; Meagher Reference Meagher2021). As such, competition regulation can be understood as an important tool for preventing and redressing high levels of industry concentration and excessive corporate power (Khan and Vaheesan Reference Khan and Vaheesan2017; Holmes and Meagher Reference Holmes and Meagher2023).

A growing body of work in the public health literature highlights how high levels of industry concentration and excessive corporate power in harmful consumer product industries can generate devastating impacts on health and equity (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Baker and Sacks2021; Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). For instance, research has shed light on the ways in which excessive corporate power in the highly concentrated ultra-processed food, alcohol, and tobacco industries likely propagates industrial epidemics through driving harmful patterns of consumption, and undermining the capacity and willingness of governments to respond through effective policy and regulatory measures (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Smith, Garde, Grummer-Strawn, Wood, Sen, Hastings, Perez-Escamilla, Ling, Rollins and McCoy2023; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Williams, Baker and Sacks2023; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Holden, Eckhardt and Lee2018; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Eckhardt and Holden2016).

Notwithstanding its potential, concerns have been raised about how competition regulation in many jurisdictions may be impeding efforts to address diverse societal challenges, not least climate breakdown and widening economic inequities (Meagher Reference Meagher2020; Teachout and Khan Reference Teachout and Khan2017). Underpinning these concerns is the emerging consensus that, in diverse sectors, competition regulation has generally tended to accommodate, rather than constrain, rising levels of market and economic power held by private business actors (Crouch Reference Crouch2011; Meagher Reference Meagher2020; Newman Reference Newman2022; De Loecker and Eeckhout, Reference De Loecker and Eeckhout2017; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Karouzakis, Sievert, Gallasch and Sacks2024).

One commonly proposed explanation behind this trend is that the goal of competition policy in many jurisdictions has been increasingly shaped by a neoliberal discourse that has shifted the focus of competition regulation onto a narrow set of economic concerns relating to so-called ‘consumer welfare’, notably high consumer prices and restrictions in output (Crouch Reference Crouch2011; Meagher Reference Meagher2020; Newman Reference Newman2022; Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011). Other explanations include the widespread lax enforcement of competition law, and the orientation of competition regulation towards nationalist economic and industrial policy goals (eg. increasing the global competitiveness of domestic firms and industries) (Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011). Yet, there appears to be little consensus on the likely public health implications of high market power and industry concentration in harmful consumer product industries (Crane Reference Crane2005; Hammer Reference Hammer2000; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Williams, Nagarajan and Sacks2021). As such, it is difficult to assess the influence of current models of competition regulation on health, let alone prescribe health-promoting alternatives.

Given the abovementioned considerations, this paper aims to examine potential opportunities for synergies between competition regulation and the objective of addressing the rising global burden of industrial epidemics. Hereinafter, the paper is structured into five main parts. In the next section, we highlight how the normative goals of competition policy in many jurisdictions are often at odds with the public health objective of reducing the consumption or use of harmful consumer products. We then argue that this is primarily because the current goals of competition policy, particularly those shaped by the prevailing neoliberal discourse, very often legitimise rising industry concentration and market power, and delegitimise the consideration of social policy objectives (Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011; Meagher Reference Meagher2020). In the next section, we outline why this is problematic for public health by identifying several mechanisms by which high levels of industry concentration and market power in harmful consumer product industries likely result in an overall increase in adverse health outcomes.

In the third section, we use the illustrative example of the global beer industry to highlight important ways by which competition regulation, taken as a whole, has facilitated rising industry concentration and market power in a key harmful consumer product industry. Specifically, we draw several insights from several regulatory decisions made by various competition authorities involving Anheuser-Busch InBev, the world’s largest beer company at the time of writing.

In the fourth section, we turn our attention towards potential avenues through which synergies between competition regulation and public health policies regarding harmful consumer product industries could potentially be found and enhanced. These avenues include stronger merger regulation, as well as the integration of sustainability and social policy objectives into competition regulation more broadly. Finally, we outline several opportunities for public health researchers and advocates to take part in discussions on, and ideally help to shape, competition regulation around the world.

2. The normative goals of competition policy

The stated goals of competition policy vary considerably around the world. In broad terms, competition policy goals in most jurisdictions are shaped by similar neoliberal or nationalist economic discourses (eg. growth of domestic companies), with competition policy goals in some jurisdictions also shaped to a limited extent by social policy discourses (eg. those relating to protecting jobs) (Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011; Freyer Reference Freyer2006; Njisane and Ratshisusu Reference Njisane, Ratshisusu, Bonakele, Fox and Mncube2017).

It is the neoliberal discourse, which ostensibly frames competition-related concerns around ‘consumer welfare’, that has increasingly come to shape the normative goals of competition policy worldwide (OECD 2022, 2023). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) notes that most competition authorities currently use some form of the so-called ‘consumer welfare’ standard to meet their competition policy goals (OECD 2022, 2023). Notwithstanding its many variations, this standard generally places the focus of competition regulation on protecting consumer prices, and increasing output and consumer choice (ICN 2011; OECD 2023). A small number of jurisdictions, such as Australia and Canada, use a ‘total welfare’ standard, which places the focus on maximising the sum of consumer and producer ‘welfare’, rather than just ‘consumer welfare’. Yet in practice, the distinction between the ‘consumer welfare’ and ‘total welfare’ standards is not always clear (Vickers Reference Vickers2024; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Karouzakis, Sievert, Gallasch and Sacks2024).

The ‘consumer welfare’ standard is underpinned to a considerable extent by neoclassical economic theory (Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011), which, among other things, assumes that ‘consumer welfare’ is maximised when the overall use or consumption of any given product or service is maximised (Newman Reference Newman2022). While some jurisdictions, such as the European Union (E.U.), consider other components of ‘consumer welfare’, including innovation or product quality, these are rarely analysed as rigorously as effects on price or output in competition assessments (OECD 2013).

In the neoclassical analysis of ‘consumer welfare’, neither the nature of the product or service in question, nor the way in which its use or consumption is distributed, are typically considered. Yet, from a public health standpoint, these are clearly very important issues to consider when determining the extent to which the goal of maximising the use or consumption of any given product or service supports or undermines the objective of promoting the welfare of citizen-consumers. Certainly, the goal of increasing the availability and affordability of health-promoting products and services (eg. healthy foods) would likely be synergistic with many public health policies (assuming that market competition is indeed an appropriate mechanism to coordinate the provision of the products or services in question). In contrast, the goal of maximising the use or consumption of harmful consumer products is starkly inconsistent with public health policies (eg. marketing restrictions and so-called ‘sin’ taxes) and international frameworks (eg. the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control) designed to address the harms associated with the consumption or use of such products (Crane Reference Crane2005).

Neoclassical and neoliberal economic theories both promote market competition as the most appropriate and efficient arrangement for organising social and economic activities (Watson Reference Watson2018; Crouch Reference Crouch2011). However, while neoclassical economic theory views perfect competition as the optimal way to maximise ‘consumer welfare’, many proponents of neoliberalism are willing to tolerate marked deviations from this ideal. Such divergence from neoclassical economic theory is justified with different lines of argument. These include arguments that centre on raising doubt about the efficiency and purpose of government regulation (Buchanan and Tullock Reference Buchanan and Tullock1962; Bork Reference Bork1978; Stiglitz Reference Stiglitz, Bonakele, Fox and Mncube2017; Stigler Reference Stigler1971), as well as emphasising the purported economic efficiency of dominant firms (Baumol Reference Baumol1982; Meagher Reference Meagher2020). More broadly, many proponents of neoliberalism perceive deviations from perfect competition as necessary to promote innovation (Varian Reference Varian2016; Hovenkamp Reference Hovenkamp2008), to build and protect the global competitiveness of domestic firms and industries (Lancieri et al., Reference Lancieri, Posner and Zingales2022; Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011), and, perhaps most critically, to maximise shareholder value (Crouch Reference Crouch2011).

Despite the divergence between neoclassical and neoliberal views on competition, the ‘consumer welfare’ standard has been instrumental in legitimising the neoliberal approach to competition regulation, primarily by shifting the focus of competition regulation towards a narrow set of economic considerations, and by promoting a highly technical economics-based approach to assessing such considerations (Buch-Hansen and Wigger Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011; Freyer Reference Freyer2006; Meagher Reference Meagher2020; Gstalter Reference Gstalter2005). Indeed, in the U.S., it has been argued that the ‘consumer welfare’ standard became a valuable tool to legitimise and normalise a pro-monopoly approach to competition regulation (Orbach, Reference Orbach2014), with its emergence marking a major shift away from the ‘Golden Era of Antitrust’ between the 1940s and 1970s, in which high market and industry concentration were widely perceived as being an economic and political threat (Stucke and Ezrachi, Reference Stucke and Ezrachi2017; Fox, Reference Fox2023). In other jurisdictions, including within the E.U. where states have often long tolerated highly concentrated industries, the ‘consumer welfare’ standard has instead served to shift focus away from the consideration of social and industrial policy objectives in competition regulation (Buch-Hansen and Wigger, Reference Buch-Hansen and Wigger2011; Freyer, Reference Freyer2006). In the next section, we outline why rising levels of market power and industry concentration in harmful consumer product industries are particularly problematic from a public health standpoint.

3. High levels of industry concentration and market power in harmful consumer product industries: A blessing or a curse?

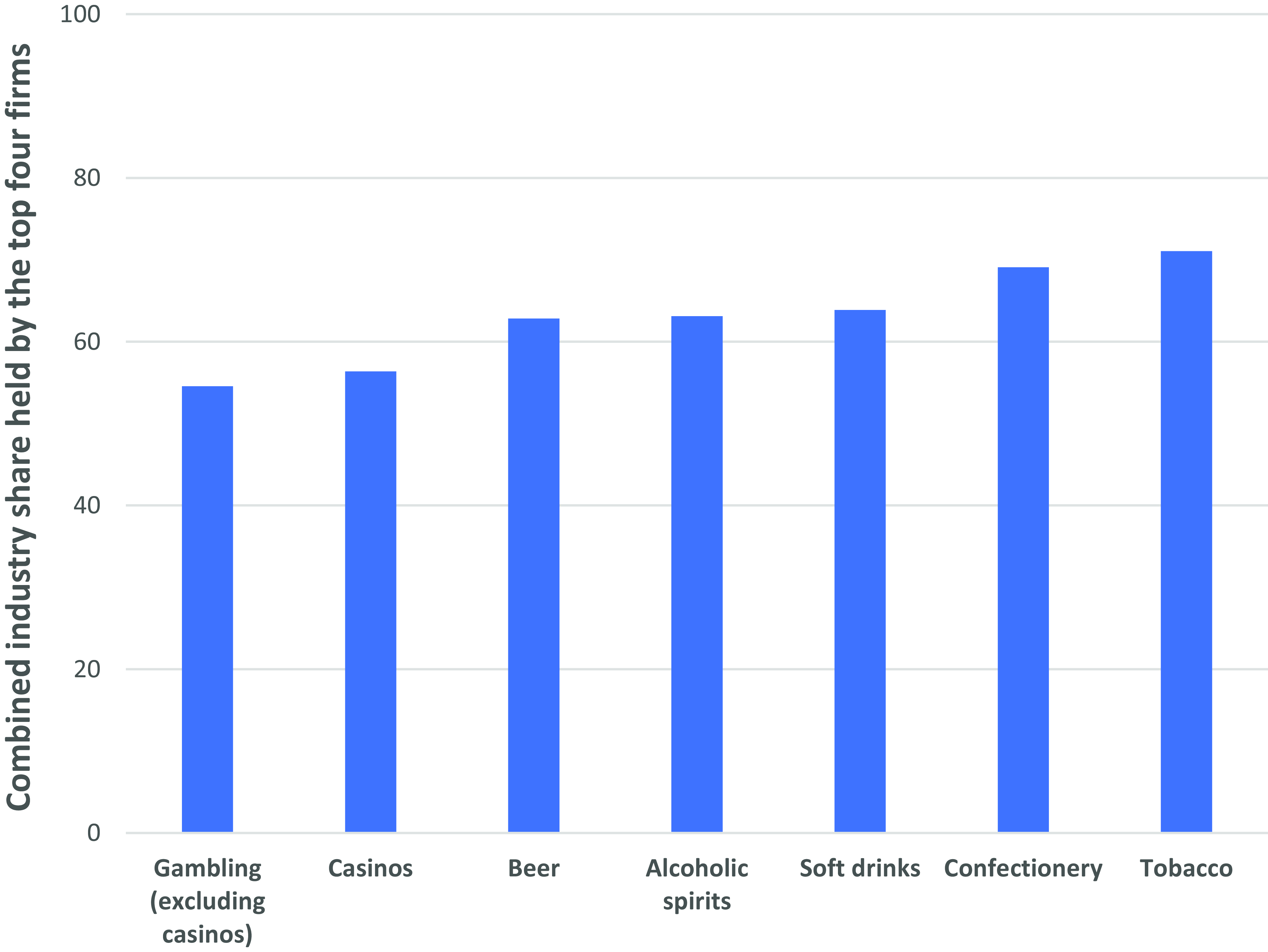

As has been the case for many industries across the global economy (De Loecker and Eeckhout, Reference De Loecker and Eeckhout2017; UNCTAD, 2018), industry concentration and market power have either risen or remained at high levels in many harmful consumer product industries in recent decades (Howard, Reference Howard, Patterson and Hoalst-Pullen2013; Babor et al., Reference Babor, Holder, Caetano, Homel, Casswell, Livingstone, Edwards, Österberg, Giesbrecht, Rehm, Graham, Room, Grube, Rossow, Hill and Thomas2010; Tobacco Tactics, 2023; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Williams, Baker and Sacks2023). As of 2020, only a small number of firms dominated several key harmful consumer product industries at the global level (see Figure 1). These industries can be understood as being comprised of a patchwork of highly concentrated market structures, in which the market power of the dominant firms is often excessive, at least insofar as they have the capacity to shape market conditions to advance their own material interests with minimal regard to interests of others (Meagher, Reference Meagher2020). While there are likely factors behind the rising and/or high levels of concentration and market power in many harmful consumer product industries, it should be noted that many competition authorities and courts have effectively allowed such trends to take place despite their regulatory powers.

Figure 1. Estimated top four-firm concentration ratios of a selection of harmful consumer product industries at the global level, 2020.

Data sourced from Compustat North America and Global databases, accessed via Wharton Research Data Services. Figure includes data for publicly listed companies on major stock exchanges around the world that require reporting in a currency listed on the U.S. Federal Reserve Board’s publicly accessible foreign exchange rates table. Both the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) sub-industry level and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) at the six-digit level were used to categorise firms into industries, with the latter used when the GICS was considered to be insufficiently granular. Categorisation was as follows: Gambling (excluding casinos) = NAICS 713290; Casinos = NAICS 713210; Soft drinks = GICS 30201030; Beer = GICS 30201010; Alcoholic spirits = NAICS 312140; Confectionery = NAICS 311351 + 311352 + 3113 (for identified confectionery firms); Tobacco = GICS 30203010.

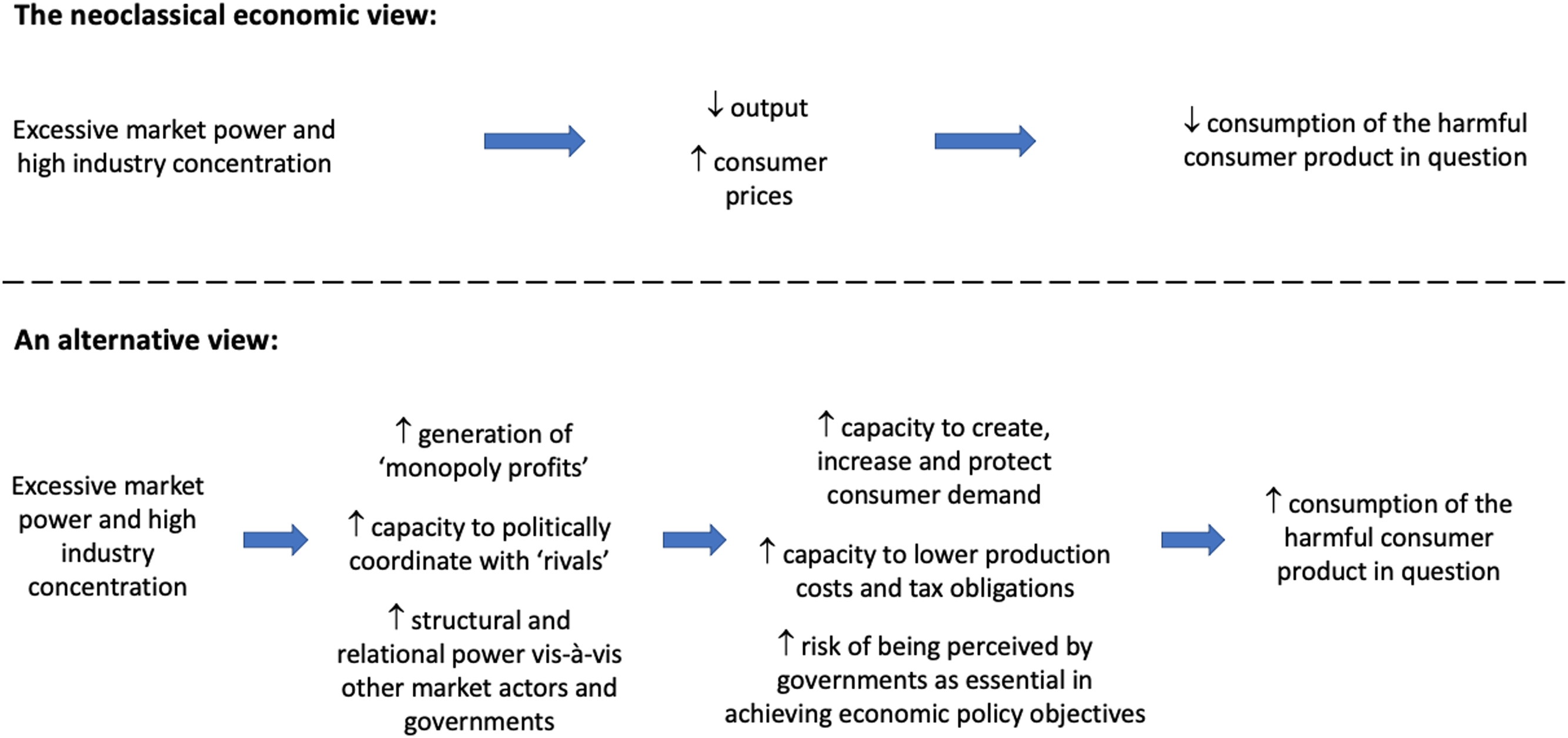

In essential industries such as life-saving pharmaceuticals and healthy foods, public health advocates and proponents of neoclassical economic theory would likely agree that high levels of industry concentration and market power may impede the availability and affordability of the products or services in question. Yet, there appears to be a lack of consensus on the likely effects of high levels of industry concentration and market power on consumption levels in harmful consumer product industries. This is because the prevailing neoclassical view assumes that, regardless of the product or service in question, excessive market power invariably leads to an overall reduction in output and an increase in consumer price compared to what would occur under competitive conditions (Stigler, Reference Stigler1956). In this respect, it is generally assumed that a monopolist or oligopolist will seek to maximise its profits by restricting its output to the extent that it can charge prices at a level above both marginal revenue and marginal cost (Mansfield, Reference Mansfield1975). It follows, then, that proponents of this view would likely contend that accommodating market power in harmful consumer product industries would be advantageous for public health in that it would facilitate a reduction in consumption-related health harms (Hammer, Reference Hammer2000; Crane, Reference Crane2005; Gulbrandsen and Skeath, Reference Gulbrandsen and Skeath1999).

However, the neoclassical view on the effects of concentration and market power in harmful consumer product industries has a number of important shortfalls (see Figure 2). With the exception of certain types of state-owned enterprises (Stockwell et al., Reference Stockwell, Sherk, Norstrom, Angus, Ramstedt, Andreasson, Chikritzhs, Gripenberg, Holder, Holmes and Makela2018), it largely ignores that monopolists and oligopolists in harmful consumer product industries tend to use their power to aggressively drive and maintain sales growth (and thus consumption) in order to maximise profits. Indeed, dominant firms in these industries spend many billions of dollars every year on marketing practices (Stuckler et al., Reference Stuckler, McKee, Ebrahim and Basu2012; Moodie et al., Reference Moodie, Stuckler, Monteiro, Sheron, Neal, Thamarangsi, Lincoln and Casswell2013), primarily to ‘create desires’ and ‘to bring into being wants that previously did not exist’ (Galbraith, Reference Galbraith1958). The combined marketing expenditure of just six ultra-processed food (Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Coca-Cola), alcohol (Anheuser-Busch, Diageo), and gambling (Flutter Entertainment) corporations exceeded US$33 billion in 2023 alone (Statista, 2024a; PepsiCo, 2024; Innes, Reference Innes2024; Statista, 2024b; AdAge, 2024) – a sum approximately five times larger than the World Health Organization’s approved budget for 2024 and 2025 at the time of writing (WHO, 2024b).

Figure 2. A diagrammatic depiction of the different views on the net effect of excessive market power and high industry concentration on the consumption of harmful consumer products.

To be sure, in some contexts, firms with excessive market power in these industries can and do raise prices above what would be possible under more competitive conditions. But even if they do raise prices, it is likely that there will likely still be more demand for the product or service in question compared to alternative scenarios in which they have less market power. This is because under such conditions, the same firms would have less capacity to generate ‘monopoly profits’, and therefore less funds to allocate towards creating and maintaining mass demand over an extended period. In harmful consumer product industries such as tobacco, there is also the issue of addiction and its effect on the price elasticity of demand (Truth Initiative, 2018).

Another shortfall of the neoclassical view is that it does not take into account that dominant firms in harmful consumer product industries use a range of strategies to maximise profits beyond manipulating consumer prices. Such firms, for instance, are often able to leverage or take advantage of their extensive monopsony power vis-à-vis suppliers and workers, as well as facilitatory government policies (eg. agricultural subsidies), to increase their net profit margins (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Williams, Nagarajan and Sacks2021). As such, in industries such as ultra-processed foods, dominant firms are often able to sell products at lower prices but with higher profit margins compared to smaller rivals, along with other companies that sell healthier alternatives (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Williams, Baker and Sacks2023).

The neoclassical view also overlooks the influence of government policies on the consumption of harmful consumer products. In reality, firms active in these industries are incentivised to undermine any form of government intervention that could reduce demand for their products, thereby restricting the extent to which they can generate profits. High industry concentration and excessive market power increase the risk of such public policies and regulations being blocked, weakened, or delayed (Teachout and Khan, Reference Teachout and Khan2017; Cowgill et al., Reference Cowgill, Prat and Valletti2023). For instance, firms with excessive market power can allocate considerable funds and resources to political practices, such as lobbying, political contributions, shaping research, and funding front groups, that seek to influence political, policy, and regulatory decision-making in their favour (Teachout and Khan, Reference Teachout and Khan2017; Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). For example, research has shown that, between 1998 and 2020, the ultra-processed food, gambling, tobacco, and alcohol industries spent more than US$3.3 billion on lobbying in the U.S. alone, with this expenditure concentrated among the leading corporations (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Cullerton and Lacy-Nichols2024). Relatedly, high industry concentration can facilitate political coordination among ‘rivals’ with a shared interest in shaping the same policies and regulations around the world (Teachout and Khan, Reference Teachout and Khan2017; Slater et al., Reference Slater, Lawrence, Wood, Serodio and Baker2024).

High industry concentration and excessive market power can also provide firms in harmful consumer product industries with considerable structural power vis-à-vis governments (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Smith, Garde, Grummer-Strawn, Wood, Sen, Hastings, Perez-Escamilla, Ling, Rollins and McCoy2023; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Holden, Eckhardt and Lee2018). Some governments, for example, opt to weaken, delay, or remove public health regulations on large corporations active in harmful consumer product industries because of the real or perceived importance of these industries in achieving various economic policy objectives (eg. generation of foreign exchange, economic growth) (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Holden, Eckhardt and Lee2018; Baker et al., Reference Baker, Zambrano, Mathisen, Singh-Vergeire, Escober, Mialon, Lawrence, Sievert, Russell and McCoy2021). For similar reasons, many governments actively support their domestic corporations in blocking and challenging the implementation of public health regulations in other countries. It has been documented, for instance, that Switzerland’s State Secretariat for Economic Affairs has applied considerable pressure on several Latin American countries to reverse their health-promoting food labelling regulations on behalf of Nestlé, the world’s largest ultra-processed food corporation (Kollbrunner, Reference Kollbrunner2022). Switzerland has also submitted ‘trade concerns’ regarding these regulations to the World Trade Organization (Kollbrunner, Reference Kollbrunner2022).

More broadly, the neoclassical view fails to consider the ways in which the effects of industry concentration and market power are distributed, particularly among different social groups and countries. It is plausible, for instance, that a dominant firm in a harmful consumer product industry could decide to restrict output and increase prices in one region, while opting to leverage its market power to pursue an aggressive growth strategy in another. As we highlight in the next section, it appears that such dynamics have been playing out across the global beer industry in recent years.

3.1 The global beer industry and the rise of Anheuser-Busch InBev

In 2019, alcohol consumption resulted in an estimated 2.6 million deaths worldwide, with the majority of these relating to non-communicable diseases and injuries (WHO, 2024a). The highest levels of alcohol-related deaths occurred in the European and African regions (as defined by the World Health Organization), with approximately 53 and 52 deaths per 100,000 people, respectively. During the same year, an estimated 400 million people around the world lived with alcohol use disorders (WHO, 2024a).

The global alcohol industry is recognised as a key driver of alcohol-related deaths and disease (Gilmore et al., Reference Gilmore, Fabbri, Baum, Bertscher, Bondy, Chang, Demaio, Erzse, Freudenberg, Friel, Hofman, Johns, Abdool Karim, Lacy-Nichols, de Carvalho, Marten, McKee, Petticrew, Robertson, Tangcharoensathien and Thow2023). Like many other harmful consumer product industries, the global alcohol industry has become increasingly concentrated in recent decades (Jernigan and Ross, Reference Jernigan and Ross2020). This has especially been the case for the global beer industry. According to the data sourced from Compustat (Refinitiv, 2021), the combined share (by revenue) held by the four largest companies in the global beer industry increased from approximately 49% in 2000 to nearly 63% in 2020.

The global volume of beer sales remained relatively steady over most of this period. According to Euromonitor International’s Passport database (Euromonitor International, 2023), the global volume of beer sales increased from approximately 186 billion litres in 2009 (the earliest year with available data) to 198 billion litres in 2023, with a considerable dip occurring during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. To be clear, this trend does not necessarily undermine the arguments made in the previous section. Indeed, it could be argued that global levels of beer consumption and corresponding harms would likely be considerably lower in a counterfactual situation in which the industry’s main players did not have the power to impede alcohol policy worldwide, nor to aggressively expand across the global South (a point to which we return below).

One important factor behind the increasing concentration of the global beer industry has been the growth of Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev) and the consolidation of its position as the world’s largest beer company via mergers and acquisitions (see Figure 3). When Belgian company Interbrew, AB InBev’s predecessor, became publicly listed in 2000, it was the sixth largest publicly listed beer company in the world with an approximate industry share of 5%. By 2020, AB InBev was by far the world’s largest beer company with an approximate industry share of 28%.

Figure 3. Three key mergers undertaken by Anheuser-Busch InBev since 2004.

Data sourced from company websites, media releases, and Compustat North America and Global databases (accessed via Wharton Research Data Services). Estimated share of global beer industry = calculated industry share in the year prior to the transaction.

Several important insights can be drawn from the regulatory decisions made by various competition authorities involving AB InBev. For instance, many of these regulatory decisions were informed by the ‘consumer welfare’ standard and, thus, at face value, went against the objectives of various existing alcohol-related public health policies (United States District Court, 2008, 2016; European Commission, 2016b; Competition Bureau Canada, 2016; ACCC, 2016). As an example, one of the primary concerns raised by U.S. competition authorities in their assessment of the 2008 InBev and Anheuser-Busch merger was that the transaction would potentially result in ‘higher beer prices to consumers’ in certain parts of the country (United States District Court, 2008). Most U.S. states had alcohol control policies in place to reduce alcohol consumption and related harms at the time of these comments (Blanchette et al., Reference Blanchette, Lira, Heeren and Naimi2020).

Similarly, then-Commissioner Margrethe Vestager made the following statement when explaining the decision made by the European Commission to approve the merger between AB InBev and SAB Miller on the condition that most of SAB Miller’s business operations in Europe be divested (European Commission, 2016b):

‘[This] decision will ensure that competition is not weakened in [EU] markets and that EU consumers are not worse off. Europeans buy around 125 billion euros of beer every year, so even a relatively small price increase could cause considerable harm to consumers’. [emphasis added]

At the time of Vestager’s comments, all European countries had at least some laws and regulations in place to address alcohol-related harms, some of which directly centred on reducing alcohol consumption (Eurocare, 2016). Just one year beforehand, the Court of Justice of the European Union had also held that Scotland’s introduction of Minimum Unit Pricing, designed to increase the price of cheap alcoholic drinks, was an appropriate public health measure in that it was ‘capable of reducing the consumption of alcohol in general and the hazardous or harmful consumption of alcohol in particular’ (Case C-333/14 Scotch Whisky Association and Others v Lord Advocate and Advocate General for Scotland, 2015; Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2016).

In various jurisdictions, AB InBev was also subject to several decisions relating to abuses of market dominance and cartel behaviour, which effectively served to increase the output of beer and reduce beer prices. For example, in 2019, the European Commission fined AB InBev 200 million euros for restricting cheaper imports of some of its beer products from entering Belgium (European Commission, 2019). Similarly, competition authorities in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Mexico fined and enforced behavioural remedies on AB InBev or one of its subsidiaries for arranging the exclusive sale of its alcoholic products with retailers (Global Competition Review, 2023, 2022, 2013; OECD and IDB, 2010). Furthermore, the German and Indian competition authorities fined participants of two separate beer cartels, both involving AB InBev, for increasing beer prices and, in the case of India, restricting supplies and dividing the country’s beer market amongst themselves (Global Competition Review, 2021, 2014).

The extent to which the above decisions have since affected beer consumption and related harms has likely been varied. For instance, the decisions relating to addressing import restrictions, exclusive dealing arrangements, and price-fixing beer cartels may have increased the affordability and availability of beer within the jurisdictions in question, at least in the short term. At the same time, though, these decisions might have also reduced the overall capacity of AB InBev to generate ‘monopoly profits’, in turn reducing its capacity to aggressively expand elsewhere and to undermine public policy globally.

In comparison, many competition authorities opted to impose a range of structural remedies involving divestitures as part of approving the InBev and Anheuser-Busch merger and the AB InBev and SAB Miller merger (Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, 2023; United States District Court, 2008; European Commission, 2016a). At best, these remedies might have potentially prevented rising concentration and market power within the respective jurisdictions, to some extent. Yet, taken as a whole, the merger remedies enforced on AB InBev clearly failed to curb rising concentration and market power at the regional and global levels. As we discuss in the next section, the consideration of a broader range of concerns beyond ‘consumer welfare’ may have enabled the imposition of more robust structural remedies on AB InBev, and, perhaps more importantly, provided legitimate reasons to prevent these mega-mergers from happening in the first place.

The incapacity or unwillingness to address rising concentration and market power in the global beer industry has arguably had far-reaching consequences for health. For instance, AB InBev’s growing dominance around the world has likely played an important role in bolstering its capacity to generate substantial operating profits, which, between 2005 and 2024, increased in nominal terms from US$3.9 billion to US$21.1 billion (Statista, 2025). The generation of substantial profits, in turn, has enabled the company to allocate extensive financial resources (in the form of retained earnings and cheap external finance) towards driving the consumption of its products and related harms in diverse contexts. AB InBev’s US$100 billion-plus mega-merger with SAB Miller, for instance, exemplifies the company’s aggressive and well-resourced expansion across emerging markets in the global South (Collin et al., Reference Collin, Hill and Smith2015; Hanefeld et al., Reference Hanefeld, Hawkins, Knai, Hofman and Petticrew2016). In recent years, AB InBev has also invested many billions of dollars – including more than US$7 billion in 2024 alone (Meddings, Reference Meddings2025) – into marketing practices designed to manufacture and maintain consumer demand. This has included large investments into strategies such as ‘social norms marketing’ campaigns aimed at increasing the social acceptability of alcohol, as well as a range of ‘corporate social responsibility’ initiatives (eg. ‘Beers for Africa’) (Movendi International, 2022).

Along with its many front groups, a body of work has exposed how AB InBev has leveraged its extensive resources and structural power vis-à-vis many governments to undermine policies aimed at addressing alcohol consumption and related harms (Movendi International, 2022). For example, in 2012, two years prior to the 2014 Football World Cup in Brazil, AB InBev and the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) successfully overturned a ban on alcohol sales in sport stadiums in Brazil, which was implemented to curb the country’s excessively high rates of football-related violence (Robiana et al., Reference Robiana, Babor, Pinksy and Johns2020). During the same year, the Brazilian government also postponed a tax increase on beer reportedly following a meeting between executives from AB InBev and the country’s finance minister (Robiana et al., Reference Robiana, Babor, Pinksy and Johns2020). Moreover, research has exposed how AB InBev and other large alcohol corporations have sought to shape public and policy narratives in diverse contexts to advance their own material interests, such as by funding front groups tasked with influencing public discussions on ‘responsible drinking’, and by undermining the generation and dissemination of scientific evidence on alcohol-related harms (Movendi International, 2022).

4. Finding synergies in the regulation of harmful consumer product industries

The case of AB InBev and the global beer industry sheds some light on how competition regulation has largely tolerated rising industry concentration and market power in harmful consumer product industries. We argue that such tolerance has, in turn, likely facilitated the rising global burden of death and disease associated with such industries (through the pathways and mechanisms outlined in Figure 2). Nevertheless, as the emergence of the ‘consumer welfare’ standard has shown, competition law and policy are amenable to change under the right social and political conditions. With this in mind, this section highlights several potential avenues through which competition regulatory tools could be used to work more synergistically with public health policies targeting harmful consumer product industries, both within and across jurisdictional borders.

Stronger merger control to prevent rising levels of industry concentration and market power represents one avenue through which competition regulation could potentially help to address the rising global burden of industrial epidemics. In this respect, it is promising that several jurisdictions, including the U.S., Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, have reportedly begun various processes to strengthen their respective merger policies (UK Government, 2022; ACCC, 2023; Competition Bureau of Canada, 2022; U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, 2023).

Recent developments regarding merger regulation in the U.S. have the potential to be particularly significant (Hearn et al., Reference Hearn, Hanawalt and Sachs2023). (Time will tell how the 2024 U.S. presidential election of Donald Trump will affect such developments.) Notably, in 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden signed an executive order on competition policy, which, inter alia, called on the country’s competition authorities – the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division – to challenge ‘bad mergers’ permitted under previous administrations (Hearn et al., Reference Hearn, Hanawalt and Sachs2023; President J. Biden, 2021). In a related development, the FTC and U.S. DOJ published a new set of merger guidelines in 2023 that could help revive the country’s merger law in accordance with how it was often applied in the post-Second World War period prior to the rise of the ‘consumer welfare’ standard (U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, 2023; Fox, Reference Fox2023). During this period, which has been referred to as the zenith of the ‘socio-political model of antitrust’ in the U.S. (Bogus, Reference Bogus2015), merger control was often used to prevent economic concentration in the pursuit of multiple political and economic goals (Fox, Reference Fox2023).

The following beer merger case provides an illustration of this more robust regulatory approach to merger control in action. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a decision made by the DOJ to block a merger involving Pabst Brewing Company, the country’s 10th largest beer company, and Blatz Brewing Company, the country’s 18th largest beer company (United States v. Pabst Brewing Co., 1966). The Court contended that the ‘merger took place in an industry marked by a steady trend toward economic concentration’, and, if not blocked, would result in ‘greater and greater concentration of the beer industry into fewer and fewer hands’ (United States v. Pabst Brewing Co., 1966). Clearly, the above decision provides a stark contrast to the merger control decisions to which AB InBev has been subjected in recent decades.

Regarding the international coordination of mergers, there could be substantial public health benefits in implementing new mechanisms to overcome the failure of current merger control frameworks in addressing the consequences of excessive market power in diverse jurisdictions, especially in the global South (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Karouzakis, Sievert, Gallasch and Sacks2024). Such mechanisms could include a United Nations Convention to govern cross-border mergers (ETC Group, 2017), which ideally would be aligned with important health-promoting international legal, policy, and normative frameworks (eg. the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes).

Another potential way to increase synergies between competition policy and public health policies targeting harmful consumer product industries could be to ensure that public health considerations explicitly fall within the scope of sustainability objectives that some jurisdictions are beginning to incorporate into their competition regulatory frameworks (Hearn et al., Reference Hearn, Hanawalt and Sachs2023). The Netherlands, for instance, has recently sought to replace the ‘consumer welfare’ standard with a broader ‘citizen welfare’ standard, in which ‘sustainability gains for society as a whole’ can be taken into account (Loozen, Reference Loozen2023; ACM, 2021). Arguably, a strong case could be made for any ‘citizen welfare’ standard to integrate concerns relating to the adverse impacts of industrial epidemics on citizens and their communities.

Yet, for the moment, the consideration of sustainability objectives in competition regulation in the Netherlands and elsewhere mostly involves deciding if a particular anti-competitive agreement should be permitted on sustainability grounds (Schinkel and Treuren, Reference Schinkel and Treuren2020; Hearn et al., Reference Hearn, Hanawalt and Sachs2023). While approving anti-competitive agreements on sustainability grounds may yield public health benefits, at least in some cases, critics point out that such benefits are almost always outweighed by the risks of such agreements, which often amount to little more than marketing and public relations spin (Schinkel and Treuren, Reference Schinkel and Treuren2020). Moreover, as argued by critics of a longstanding anti-competitive agreement in Australia that allowed the commercial milk formula industry to self-regulate its marketing practices, such agreements are rarely an appropriate substitution for mandatory regulatory measures (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Smith and Baker2015).

A more robust sustainability-oriented approach could be to directly address unsustainable business practices (Holmes and Meagher, Reference Holmes and Meagher2023; Iacovides and Vrettos, Reference Iacovides, Vrettos, Holmes, Middelschulte and Snoep2021). Holmes and Meagher (Reference Holmes and Meagher2023) outline how this approach could be operationalised in the European Union, along with other jurisdictions with similar provisions, through the use of existing laws that target abuses of dominance (Holmes and Meagher, Reference Holmes and Meagher2023). As an illustration, the authors contend that Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union could potentially be used to target dominant firms that externalise costs onto third parties and society where there is a reasonable connection between such externalities and the competitive structure of the market in question (Holmes and Meagher, Reference Holmes and Meagher2023). In this respect, we argue that externalities should include the health-related externalities that characterise industrial epidemics, along with environmental and other social externalities related to unsustainable production methods (eg. intensive agriculture), tax avoidance, and poor wages and working conditions.

The growing convergence of competition law and social policy in some jurisdictions, particularly in Africa, represents a third avenue through which competition regulation could potentially work more synergistically with public health policies targeting harmful consumer product industries (Naidu et al., Reference Naidu, Tzarevski and Nxumalo2023). This is perhaps particularly relevant for many countries in the global South, whose citizens have been increasingly exposed to the harmful and exploitative practices of foreign corporations seeking to aggressively drive demand for harmful consumer products (Moodie et al., Reference Moodie, Stuckler, Monteiro, Sheron, Neal, Thamarangsi, Lincoln and Casswell2013). Similar to Crane’s (Reference Crane2005) proposed ‘harm-reduction’ model for competition regulation (Crane, Reference Crane2005), one approach could be for the jurisdictions that have already integrated social policy objectives into their competition regulatory frameworks to also ensure that existing public health policies are taken into account. Under such conditions, competition authorities could be given the power to block mergers involving dominant foreign corporations active in harmful consumer product industries if it could be shown that the transaction in question would likely undermine the country’s existing public health policies and obligations. Alternatively, there could also be merit in mandating competition authorities in the relevant jurisdictions to take into account a broader range of harms when determining the extent to which mergers or other practices involving firms active in harmful consumer product industries undermine the social policy objectives that they are already entrusted to consider (eg. protecting the economic welfare of disadvantaged social groups) (Naidu et al., Reference Naidu, Tzarevski and Nxumalo2023).

5. Opportunities for public health researchers and advocates to engage with the competition regulatory agenda

To facilitate constructive engagement with competition policy communities, public health researchers and advocates could seek to become more familiar with the language and ideas that permeate discussions on competition regulation around the world, including those introduced in this paper. This process could involve, inter alia, promoting collaborative research projects on health and equity involving key interest-holders in the public health and competition policy communities, incorporating modules on competition and other multi-sectoral policy frameworks into public health research training, and by attending and networking at conferences and workshops on competition law and policy.

There could also be considerable merit in developing a network of values-aligned organisational actors to both monitor major competition cases around the world, as well as to support contributions to public consultations on cases with clear relevance to health and equity. For example, if another proposed mega-merger between major beer corporations were to be announced, this network could aim to coordinate submissions to public consultations across multiple jurisdictions, emphasising the likely effects of the transaction on health and equity. Inspiration for this work can be found in precedent cases in which third-party submissions have had some influence on competition regulatory decisions. As an illustrative example, in 2002, a submission from the civil society organisation Treatment Action Campaign reportedly influenced a condition placed by South Africa’s competition authorities on a merger between GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Aspen Pharmacare (Raslan, Reference Raslan2016). The condition was that GSK had to grant licenses to a number of generic companies to manufacture or import Abacavir, a treatment against the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, on favourable terms (Raslan, Reference Raslan2016).

More broadly, we encourage public health research on competition regulation to be incorporated into wider efforts seeking to shape markets and commercial systems for the betterment of health and equity (Friel et al., Reference Friel, Collin, Daube, Depoux, Freudenberg, Gilmore, Johns, Laar, Marten, McKee and Mialon2023). Through curbing excessive corporate power, competition policy has the potential to play an important role in addressing the wide range of harms associated with harmful commodity industries. In some sectors and contexts, curbing excessive corporate power is also a necessary (but not sufficient) step in enabling health-enabling business and economic models to flourish, such as those in which well-being (Wellbeing Economy Alliance, 2023), solidarity (Geiger and Gross, Reference Geiger and Gross2023), and socio-ecological justice are normalised and institutionalised (Schmelzer et al., Reference Schmelzer, Vetter and Vansintjan2022). Discussions on how to invigorate or reorient competition regulation along these lines (including the opportunities outlined in the previous section) are invariably technical, contested, and complex. Nevertheless, it is important that public health researchers and advocates actively engage in such discussions, and elevate ideas, narratives, and alternatives centred on health and equity.

6. Conclusion

In recent decades, competition regulation has arguably facilitated the rising global burden of death and disease associated with harmful consumer product industries insofar as it has generally tolerated rising industry concentration and market power in these industries. One important reason for such tolerance of industry concentration and market power has likely been the rise of the ‘consumer welfare’ standard. In many cases, this standard has been used by proponents of neoliberalism to narrow the focus of competition regulation onto a narrow set of concerns mostly relating to consumer price and output.

Recent developments around the world, though, shed some light on avenues through which competition regulation could potentially work more synergistically with public health policies targeting harmful consumer product industries. These include stronger merger control to prevent market and economic concentration, as well as the incorporation of sustainability and social policy objectives into competition regulation more broadly. While discussions on how to reorient competition regulation along these lines are invariably contested and complex, public health researchers and advocates can and should play a supporting role in pushing for a paradigm shift that can enable such transformative action.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Institute for Health Transformation (IHT) seed funding grant. Gary Sacks is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellowship (2021/GNT2008535). He is also a researcher within NHMRC Centres for Research Excellence entitled Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE-FRESH) (2018/GNT1152968), and Healthy Food, Healthy Planet, Healthy People (2021/GNT2006620) (Australia). Katherine Sievert is supported by an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.