The unveiling of Uganda’s national independence monument and flag was intended to solidify national unity. If anything, their promotion illustrated just how fractionalized Uganda’s politics had become by the early 1960s. The independence monument was unveiled on 17 November 1962, just off Speke Road and Nile Avenue in central Kampala.Footnote 1 The Freedom Statue’s designer was a Luyia sculptor from Kenya, Gregory Maloba, who had studied art at Makerere University.Footnote 2 Maloba’s use of space and geometry drew from central and eastern Africa’s artistic traditions. He refashioned pre-colonial form with the religious tableaux of the modernist sculptor Jacob Epstein, whose ‘Christ in Majesty’ displayed many geometrical features recreated in Uganda’s national monument.Footnote 3 The monument compared the creation of Uganda to a mother giving birth to a child, an adaptation of the Virgin Mary’s birth of Jesus (Figure 1). In the monument, the child extends its arms and hands into the air, elevated by an erect mother, whose recent birth and struggle is signified by the intermittent placement of a kikoi, or wraparound.

Figure 1. Uganda’s Independence Monument. Photograph by author.

Revealing Uganda’s national statue did not go as planned (Figure 2). The monument had been draped with a large flag of Uganda’s recently created national colours. The flag, however, became stuck during its removal, creating unease and tension among the officials and the audience. Government officials, including the minister of community development, rushed to aid Prime Minister Obote while Uganda’s Police Band performed to distract the audience from undue commotion.Footnote 4 The cloth eventually had to be ripped apart before the mother and child were revealed. The band then played Uganda’s recently penned national anthem. Once Prime Minister Obote began addressing the crowd of approximately 1,000 people, including Uganda’s legislators, he offered comedic relief by underscoring the metrics of maternity: ‘You know when a child is born, you cannot see it at once. That is why it took two minutes to unveil the statue.’Footnote 5

Figure 2. Prime Minister Obote and party ministers struggled to unveil Uganda’s national monument, 17 November 1962. From Adam Seftel, ed., Uganda: the bloodstained pearl of Africa: and its struggle for peace: from the pages of DRUM (Lanseria, South Africa, 1994).

A short recess for the ceremony had disrupted a vitriolic debate in Uganda’s parliament – only 700 metres away – between the country’s leading political parties: the Uganda’s People’s Congress (UPC) and the Democratic Party (DP). Prime Minister Obote was a member of the UPC. The parties had been busy that morning accusing each other of religious sectarianism, harassment, and corruption. When parliament reconvened after the awkward unveiling ceremony, the DP possessed control of the floor. The UPC and the Kiganda royalist party, KY (Kabaka Yekka, King Alone),Footnote 6 had recently unified to overturn the DP’s electoral victories throughout the country. The earlier elections had enabled the DP to appoint Benedicto Kiwanuka as the country’s first prime minister – a position he held for only several months.

The botched unveiling of Uganda’s national monument inspired Kigezi’s DP representative to talk about party mottos on the floor of parliament. The representative argued that Kabaka Yekka (KY) should more appropriately rename itself Buganda Yekka (Buganda Alone) due to its parochialism.Footnote 7 Kigezi’s DP minister next ridiculed the motto of the UPC, ‘Backward never, forward ever’. The UPC’s motto was borrowed from the title of the powerful chief Hamu Mukasa’s Protestant history of Uganda, Simuda nyuma, or No turning back; ever forward. Kigezi’s activist wittingly noted that the motto for UPC–KY should more accurately state, ‘Upward never, forward ever with truth and justice’.Footnote 8 Truth and justice was the motto of the DP.

Following the minister’s criticism of party slogans, the floor erupted with mutual allegations. Kigezi’s UPC member accused the DP of ‘beating up’ UPC members in their district. Another UPC activist, D. M. Kimaswa, a representative for Bugisu, argued that ‘every bit of violence in this country’ was the result of the DP.Footnote 9 The DP’s Acholi representative, Alex Latim, asserted that legislation was necessary for ‘controlling violence all over Uganda’. Public monuments were not only difficult to unveil: their creation animated far-reaching debates about political and sectarian violence on the eve of independence.

This article explores the politics of pageantry in colonial Uganda. Political debates surrounding Uganda’s national monument were not unique. They harkened back to much older debates about the politics of colours and design patterns. As activists looked toward independence, they simultaneously worked to create, standardize, and circulate national material culture. In imperial and Ugandan historiography, flags are often associated with the pageantry of conquest or eventual post-colonial state building. And while a modest body of literature exists on colonial and post-colonial flags, we know little about how internal debates accompanied their creation.Footnote 10 Drawing from the national press and the private papers of anti-colonial organizers in Uganda, particularly the papers of Benedicto Kiwanuka,Footnote 11 whose Democratic Party was at the centre of debates over Uganda’s post-colonial flag, this article pushes us past a superficial association of flags with either conquest or liberation into the ideational worlds that undergirded their hoisting. It expands the registers with which we approach cultural and intellectual history writing, moving us beyond a world of texts into a highly contested visual arena where competing patterns, colours, and decorum animated political mobilization and dissent. Political debates about flags and national material culture were shaped by much deeper ideas about the theologies of colour.

The article begins by outlining how flags and colonial expansion have often been described following predictable tropes about conquest and the imposition of imperial material culture. The early African creation of religious flags, including the ‘Ichabod’ flag, though, shows how converts produced and paraded flags on their terms. After discussing religious flags during the late nineteenth century, we will see how political and historical pluralism in early colonial Buganda resulted in the proliferation of several flags in public life. The practice of waving flags coincided with public debates about regnum succession and royal authority. Into the 1950s, competing moral projects in Buganda and Uganda, more broadly, translated into colliding efforts to manufacture national flags and colour palettes. Far from ushering communities into fictionalized worlds of post-colonial unification, a history of flags and pageantry enables us to see political projects and aspirations that were consistently silenced in the national histories of the state.

I

European and American military commanders were preoccupied with hoisting imperial flags throughout the nineteenth century. Flags were believed to symbolize or embody national ownership and the advancement of imperial priorities over communities and the natural world. Following the Anglo-American treaty of 1849, the government of the United States deployed a small naval fleet along the western African coast. As the naval commander Andrew H. Foote summarized, by expanding the ‘rights of the American flag’, the United States would improve ‘the condition of Africa in checking crime, and preparing the way for the introduction of peace, prosperity, and civilization’.Footnote 12 At a time when the United States was on the brink of civil war, Foote used 390 pages to illustrate the extent to which the American flag signified the end of transatlantic slavery, or ‘the suppression of this iniquitous traffic, or even preventing the use of our flag in the trade’.Footnote 13

The expansion of colonial empires and international missionary movements throughout the late nineteenth century also heralded a moment for the creation and circulation of flags. The Anglican periodical Church Missionary Gleaner covered the proliferation of Christian and British flags. Protestant missionaries debated the relationship between the British flag in foreign lands and conversion rates. While missionaries could see their work benefiting from the world of empire and its hoisted emblems, they also believed that the absence of empire did not necessarily restrict the success of their mission. As one Anglican missionary in the early twentieth century asserted, when contrasting the presence of churches in Hong Kong and China:

What then about China? Do Missions thrive under the British flag, but fail in China? No, thanks be to God! All through the vast Empire of China we see the same thing; congregations gathered out here and there, more scattered, it may be, than in the colony of Hong Kong, but comprised of tens of thousands of men and women, called of God into the wonderful light of His Gospel.Footnote 14

Missionaries, though, were anxious about seeing competitive flags, especially prayer flags in rural villages where ‘pagan gods’ were believed to influence the daily affairs of communities. British medical workers in Punjab used poetry to condemn public healers whose shrines donned colourful banners. One published poem noted:

It is not without reason, then, that historians of nationalism and empire have often associated the global history of flags with the expansion of republican revolutions and colonialism. Eric Hobsbawm argued that flags increasingly symbolized European state power during the continent’s republican moment throughout the nineteenth century: ‘In the absence of monarchies, the flag itself could become the virtual embodiment of state, nation and society.’Footnote 16 Partha Chatterjee has shown how the East India Company used its flag to symbolize the protection of the company’s Indian intermediaries in West Bengal, even as the region’s nawab, or native governor, advocated for sovereignty.Footnote 17 Similarly, Duncan Bell’s history of Anglo-American racial utopias illustrates how ideas about the expansion of American and British flags were believed to create a world of ‘abiding peace throughout the oceans and seas of the world’.Footnote 18

But flags were not simply the concern of republican revolutionaries and Euro-American colonizers. Nor do the genealogies of modern flags trace neatly to Europe. Throughout the late nineteenth century, Ottoman administrators negotiated flag displays throughout northern Africa.Footnote 19 James Brennan has shown how the production of the sultan of Oman’s flag in colonial Kenya was interconnected with coastal authority in eastern Africa. As he notes: ‘It was through such symbols, above all the Sultan’s flag, that an Arab and Swahili elite theorized the contours and content of coastal sovereignty.’Footnote 20 By the early twentieth century, flags in eastern Africa seem to have taken on almost mystical or spiritual-like properties. Following the Mahdi conflicts in late nineteenth-century Sudan, numerous millennial movements emerged. One movement was organized by the hunter Mohamed Wad Adam. According to the missionary A. E. Richardson, Adam believed himself to be the prophet Jesus, who, after receiving divine inspiration, ‘hoisted a flag’.Footnote 21

Understanding that kingdoms in Uganda had begun developing flags before European exploration helps us begin to understand why they were so intensively debated and appropriated throughout the early colonial period. Flags were seldom understood in ways that easily conformed to colonial control. The processes of creating national and royal material culture were far more fraught and diversified than historians have often described. Rather than seeing flags as instruments that announce singular political authority, it is more helpful to think about flags as transmutational, giving life and significance as they are bruised and battered by political winds of varied origins.

II

Eastern African Christians incorporated flags into their liturgies and political processions. Religious converts defined the terms and histories by which they produced and paraded flags. In no case was this clearer than in the display of the ‘Ichabod’ flag, created by the Malawian Christian William Henry Jones. The hagiographies surrounding the creation of this flag permeated Protestant political imagination and what was believed to be at stake in the Protestant conversion of the eastern African kingdom of Buganda. According to missionary accounts, Jones had been captured by Omani slave raiders before being serendipitously rescued by a British cruiser.Footnote 22 By the early 1860s, Jones was sent to the Christian village of Saharanpur in northern India, where he was placed under the tutelage of Revd W. S. Price. He learned blacksmithing from Price and, following baptism, took the name William Henry Jones. Examining Jones’s vision for one of eastern Africa’s first religious flags helps us think about the earliest ways in which converts organized public mobility and memory. Flags were quickly enveloped in older and more expansive debates about regional and international power.

Jones returned to eastern Africa in 1864, where he was one of two native clergymen appointed to work with Bishop Hannington, who by the early 1880s was strategizing the Anglican conversion of Buganda following the arrival of Protestant missionaries in 1877. Hannington ordained Jones in 1885, shortly before they began their well-publicized journey into Uganda’s interior. Hannington and Jones reached Busoga, on Buganda’s eastern border, by October of the same year. For reasons that have been discussed extensively,Footnote 23 Kabaka (King) Mwanga II ordered the execution of Hannington and several in their caravan. Jones survived. Historians of Uganda generally agree that Mwanga believed that the eastern direction from which Hannington approached was customarily forbidden to visitors.Footnote 24 Earlier traders had reached the kingdom via the western front, through Kagera, in north-western Tanzania.

Following Hannington’s death, Jones returned to western Kenya, reconvening with a section of the caravan that had remained in Kavirondo. Once in Kavirondo, Jones and his cohort crafted a large blue flag, which commentators suggested signified mourning. In large white letters, the word ‘Ichabod’ was stitched (Figure 3). The word Ichabod, or Ikabodi in Kiswahili, recalled the biblical story of the military defeat of Israel by the Philistines. According to the account of I Samuel, the Philistines militarily defeated the Israelites, resulting in the death of over 30,000 Israeli foot soldiers. In the process, the Ark of the Convent of Moses was captured and its two priests, the brothers Hophni and Phinehas, were killed. When news of the capture of the Ark and the death of the two priestly brothers reached their father, Eli, who was the kingdom’s principal judge for around forty years, he fell out of his chair and died from a neck injury. Due to the trauma of the war, the loss of the Ark, and the death of both her father-in-law and husband, Phinehas’s unnamed wife died during childbirth. Before dying, though, she named her son ‘Ichabod’, or Ikhavod, meaning ‘without glory’. The biblical text stated: ‘She named the child Ichabod, meaning, “The glory has departed from Israel”, because the ark of God had been captured and because of her father-in-law and her husband.’Footnote 25

Figure 3. Eastern Africa’s nineteenth-century Christians used the Ichabod flag during the procession of Bishop Hannington’s murdered body from Uganda to Kenya. The flag was kept in CMS House, Oxford, for an extended period before being relocated to St Paul’s Cathedral, Namirembe, Uganda. Image provided by Ken Osborne, CMS House, Oxford.

The biblical story, for Jones, chronicled profound loss and the uncertainty of new beginnings, seen in the departure of God’s presence and the death of his priests. With their flag hoisted, Jones and his mourning caravan marched 500 miles to the Kenyan coast. The missionary E. C. Dawson underscored the disarray with which Christians and distraught women lamented the bishop’s death in his official account of Hannington’s life and martyrdom, noting how African Christians created the flag before the large-scale arrival of additional British missionaries in Uganda.Footnote 26 In the Church Missionary Gleaner, the march of the flag illustrated for their British readers at home one of the most moving stories in the history of African Christianity. Like Dawson’s account, the Gleaner was careful to illustrate how the flag had been created and carried by African coverts:

As the two Englishmen in charge of the mission station hastened forward, they met a kilangozi, or guide, bearing aloft this blue flag, with its white-lettered inscription Ichabod, ‘The glory is departed’ (1 Sam. iv.21). ‘Nothing’, says Mr. Stock in his History of the C.M.S., ‘more touching than the incident of that flag – made by African hands alone, and carried by them five hundred miles – is recorded in this book.’Footnote 27

British missionaries did not write partisan accounts in a vacuum. They penned them alongside Buganda’s late nineteenth-century chiefs, who actively used newfound literacy to standardize histories of the region’s deep past.Footnote 28 The Protestant historian and chief Hamu Mukasa, with Revd J. D. Mullins, recounted that James Hannington was among Uganda’s first martyrs. Their account also accentuated the story of the Ichabod flag, which was preserved in the Church Missionary House in Salisbury Square. Like Protestant writers in the Church Missionary Gleaner, Mullins and Mukasa suggested that God’s glory had not departed with the bishop’s death:

It was a melancholy procession which made its way at length to the mission stations on the coast. At its head was carried a mournful flag of blue trade-cloth, which bore in white letter the word ‘Ichabod’. Their sorrow made the inscription natural to those Africans, but never was [a] motto more mistaken. Indeed, ‘the glory’ had not departed. Hannington did more for Africa by his death than in his life. Within a few weeks after the news came to England, fifty men had offered themselves to the Society for service in the mission-field; and Hannington’s name has continued ever since to be an inspiration to many.Footnote 29

Hannington’s martyrdom was used to legitimize eastern Africa’s Protestant hierarchy. His death was referenced on public occasions, commemorated in the Anglican calendar, and invoked during the expansion of Anglican architecture, including the opening ceremony of the Anglican Cathedral of Mombasa.Footnote 30 In Buganda, Protestant writers like Hamu Mukasa reworked Hannington’s death to legitimize their role in the colonial state. Such histories were interwoven with claims about royal authority following the state execution of Muslim and Christian converts throughout the late nineteenth century.Footnote 31

Fewer writers reflected more on early Christianity in Uganda and Hannington’s death than Apolo Kaggwa, a Protestant convert and prime minister (Katikkiro) of Buganda throughout the early 1900s. He benefited extensively from his proximity to the colonial state through a large salary and the gift of landholdings in Uganda. He was also one of Buganda’s most influential historians. His history of the kings of Buganda, Bassekabaka be Buganda, was the most read book in colonial Buganda other than the Bible.Footnote 32 Kaggwa deployed his biography of Kabaka Mwanga II to show how he (Kaggwa) had attempted to save Hannington’s life.

[K]abaka Mwanga was informed that a European Bishop Hannington was coming from Busoga and was at Luba’s. Upon receiving this information he became angry and said ‘A European to approach from that direction has come through a wrong side (manju).’ He then sent out Lwanga Wakoli to go and kill him. By this time there was a young boy who was the Omuwanika Omuto, one Apolo Kagwa, who upon hearing that was going to happen, sent out Mako Sekajija to tell Rev. Mackay that the Kabaka had sent out people to Busoga to murder the Bishop. Upon hearing this Rev. Mackay came up to the Kabaka with presents to try and induce the Kabaka not to order for the murder of the Bishop. Presents were accepted but the Kabaka did not change his mind to excuse him but confirmed his original order.Footnote 33

While Kaggwa was unsuccessful in saving Hannington’s life, he effectively presented himself as a trustworthy guardian of Protestant political priorities. As Kaggwa told the story, the Ichabod flag would soon give way to the ‘flag of the United Kingdom’, which Kabaka Mwanga II believed symbolized the protection of his kingdom.Footnote 34 How flags were internally debated among neighbouring kingdoms during the early colonial period is a topic that requires additional research. By the time Buganda signed its colonial agreements in 1894 and 1900, the kingdom had already undergone significant debates about the connection between flags and religious authority. Public debates about power, authority and theologies of ‘glory’ were intermingled. But as we will now see, Catholic political thinkers created their own flags in early colonial Uganda.

III

Contestations surrounding the early colonial flag continued during Kabaka Mwanga II’s regency and throughout his son’s sovereignty. British officials saw the Union Jack as embodying political stability structured around Protestant power. The process of hoisting colonial flags, however, reified political and religious divisions within the kingdom. Religious communities had different ways of talking about flags and their larger political significance. To respond to the Protestant chiefs who now controlled most of the private landholdings and government posts in Buganda, Catholic converts created their own flags to challenge Protestant authority.

The British mercenary Frederick Lugard worked incessantly to ensure that the flag of the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was displayed throughout southern and western Uganda, areas occupied by the pre-colonial kingdoms of Buganda, Bunyoro, Tooro, and Ankole. According to the colonial administrator and botanist Harry Johnston, Lugard used the maxim gun in Buganda to force ‘the French party (as the Roman Catholics styled themselves)’ from the king’s court during the early 1890s, enabling Buganda’s Protestant chiefs to secure military control of the state.Footnote 35 When Mwanga fled the kingdom’s capital (present-day Kampala) with his Catholic supporters following the battle of Mmengo (1892), the defining battle of Buganda’s sectarian civil war, Lugard hoisted the flag of the IBEAC, the first colonial flag to wave over a kabaka’s palace. The Union Jack, which differed only slightly, replaced it in 1894.

Like Lugard, Winston Churchill, then Great Britain’s young under secretary of state for the colonies, argued that ‘[u]nder the shelter of the British Flag, safe from external menace or internal broil, the child-King [Kabaka Chwa] grows to a temperate and instructed maturity’.Footnote 36 In Churchill’s estimation, under the British flag, ‘[p]eople, relieved from the severities and confusions of times not long ago, are apt to learn and willing to obey’.Footnote 37 Consistent with Lugard’s and Churchill’s vision of the Union Jack, colonial administrators regularly featured flags when they began producing photographic evidence to illustrate the progress of Christian civilization in Uganda. J. F. Cunningham’s Uganda and its people was one of the earliest accounts of colonial administration in southern Uganda. In the book, the flagpole was featured in the photographs of Police Hill, which included a hospital and the police barracks in Entebbe. Flags signified the advent of development, scientific modernity, and unwavering justice.Footnote 38

But Kabaka Mwanga and Baganda Catholics had very different ways of remembering and conceptualizing the role of flags in public affairs. Lugard’s account included several extensive sections on the anxieties and suspicions with which Mwanga and Catholics approached colonial flagging strategies.Footnote 39 Lugard asserted that Catholics appeared ‘nervously afraid of a flag, understanding that it means that they give away their country, and the Wa-Fransa [Baganda Catholics] are prepared possibly to fight sooner than accept it’.Footnote 40 It was also Lugard’s understanding that Catholics believed that his military went about with crates full of flags, which chiefs would be forced to fly in their respective territories.Footnote 41 At one point, Lugard recalled, he had to stop using the word ‘flag’ entirely, to prevent the kingdom from experiencing a ‘horrible civil war’.Footnote 42

Mwanga raised his flag to challenge the authority of Lugard’s. Mwanga inherited his standard from his father Kabaka Muteesa I (r. 1856–84) (Figure 4). It was hoisted in the capital late at night in July 1892, during a ceremony that included the beating of the kingdom’s war drums.Footnote 43 A group of informants warned Lugard that the flag had been used by Muteesa I to declare seasons of war and expansion. The flag itself was approximately 12ft square. The colour of the background of the flag was red, four years before the creation of Zanzibar’s red flag. A large shield was sewn on the left side. To its right, two crossing spears formed an x-shaped pattern. Both emblems were white. When Lugard later commented on the contentious nature of flags in Buganda, he recalled, ‘The country, I said, is British by treaty, but the king flies a flag of his own. If I mention the word “flag” there is talk of war.’Footnote 44

Figure 4. The flag of Kabaka Muteesa I and Kabaka Mwanga II, Buganda, late 1892. Illustration in Frederick D. Lugard, The rise of our east African empire: early efforts in Nyasaland and Uganda (2 vols., London, 1968).

By the mid-1890s, Catholics had also created a flag to represent their interests, a replication of the national flag of France.Footnote 45 It was only after the religious wars of Mmengo that Catholics in Buddu were reluctantly willing to recognize the authority of the British flag,Footnote 46 although they refused to both hoist the flag of the IBEAC and to offer Lugard food during his march into Buddu.Footnote 47 According to the Catholic biographer, Joseph Kasirye, the leadership of the White Fathers refused to touch or distribute the flag, which represented for them the use of state violence against converts.Footnote 48 By the end of the religious conflicts, Lugard triumphantly recalled: ‘So at last the British flag flew over Uganda, over both creeds alike, and the national distinctions of Fransa [French] and Ingleza [British] were abolished.’Footnote 49 Lugard’s reading of the situation, though, was wishful thinking. When Uganda’s southern flag extended beyond Buganda, African communities quickly understood it as a piece of fabric that reinforced Protestant and British power in Buganda. As Michael Twaddle has shown, when the Muganda military general Semei Kakungulu organized an army to incorporate eastern Uganda into the central administration of the colonial Protectorate, he saw himself conquering lands in ways that were consistent with the mid-nineteenth century (okuwangula ensi).Footnote 50 Kakungulu’s eastern Ugandan military expedition included 150 guns, large amounts of powder and shot, and a government flag (bendera ya Govumenti). In Budaka, near Mbale, Protestant chiefs and servants under Kakungulu’s authority converted to Catholicism to secure protection at the Mill Hill mission.Footnote 51 Kakungulu and the British official in the area, W. R. Walker, argued passionately and publicly over who had the authority to fly the Union Jack at their respective headquarters. On one occasion, Walker, who was furious with Kakungulu for flying the flag at his fort, arrived with a saw to fell the flagstaff, which Walker argued undermined his authority in the region. It was only after Catholic missionaries talked the matter over with Kakungulu that he was willing to co-operate with Walker. After dealing with Lugard during the religious wars, Catholic interlocutors were all too aware of what was at stake in the hoisting of the British flag.

When flags were produced and circulated in early colonial Buganda, they were not simply imposed upon passive and subjugated communities. Competing devotees created, disputed, and fought with vigour to hoist and lower political banners. While British administrators had a clear vision of what was at stake in having the winds of change flap the flags of the IBEAC and the Union Jack, they could not control the terms upon which the poles were erected. In time, as we will now see, the production of a national flag for post-colonial Uganda resurrected older debates about inclusion, exclusion, and religious authority.

IV

Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, Ugandans studied the creation of post-colonial flags in Africa and beyond by reading international newspapers and listening to radio coverage.Footnote 52 When the time came for Uganda to produce its own post-colonial flag under the leadership of the DP and the party’s president, Benedicto Kiwanuka, the UPC and KY accused them of institutionalizing their movement’s colours, especially green, in the national flag. When the UPC and KY secured control of parliament within a year, they too used their parties’ colours to welcome the era of Uganda’s independence. The red and black of Uganda’s eventual flag were the principal colours of the UPC, while yellow was a homage to KY. The earlier flag design, which featured DP’s green, was quickly tossed aside.

Among the public, it was believed that the DP was the country’s largest Catholic party, while the UPC and KY constituted a Protestant coalition between Anglican conservatives in Buganda and republicans in northern Uganda who sought to maintain state power and disrupt Catholic mobilization. Because the competing visions for Uganda’s flags were overtly partisan, flags and party symbols and colours were publicly burnt and used to identify political and religious loyalties and orchestrate acts of intimidation and violence. Banners and party symbols were deployed as speaking props and attracted considerable debate in assemblies and the national press.

Uganda’s national flag did not represent the actualization of the post-colony after a long, tedious march toward independence. The constituencies of the three leading political parties – the DP, UPC, and KY – saw in the flag and party colours the possibility of preserving or eroding the state’s religious and colonial hierarchies. The previous section showed how efforts to standardize Uganda’s earliest colonial flag accompanied political rupture and unsettlement in Buganda. Throughout the colonial period, Uganda’s national flag was flown at administrative buildings throughout Entebbe and at district headquarters throughout the country, police posts, hospitals, and carceral sites. By the late 1950s, communities were fully aware of what was at stake in controlling the production of national material culture.

On 18 November 1961, Benedicto Kiwanuka, the president of the DP and chief minister of Uganda, introduced a motion to form a committee to create Uganda’s national flag, anthem, and coat of arms.Footnote 53 When the party publicly announced the terms of the committee and the process for receiving and reviewing recommendations, artists and concerned writers filled the national press with ideas. One editorial, written by Henry Ojok, noted that it was commonly known that party members were arguing that their respective party’s colours should become the colours of the national flag, a notion that he rejected.Footnote 54 For Ojok, Uganda’s national flag should incorporate four colours. Blue symbolized Uganda’s lakes and rivers, which were sources for fishing, industry, power, communications and recreation. Green signified ‘[f]ertile motherland on which we depend for food and wealth’. White, following the Hague Conventions of the early twentieth century, was the ‘most appropriate symbol for peace in the country’. And gold symbolized the mineral wealth of the country. Ojok argued that the crested crane should also be placed on the flag to symbolize the beauty of Uganda, like Uganda’s colonial flag, which also featured the crested crane.Footnote 55 He then went into great specificity to describe the placement and size of the flag’s patterns. Ojok was not alone. Members of the Teso District Council General Purposes Committee argued that Uganda’s national flag should feature blue to represent Uganda’s water, and green to draw attention to vegetation. They also argued that the crested crane would symbolize continuity with the past.Footnote 56

The DP’s National Flag Committee forwarded its recommendation by 21 March 1962. The flag would be comprised of three vertical bands of green, blue, and green, separated by narrow gold bands. In the middle of the blue central band, a gold crested crane would be placed. One DP activist explained that ‘the green in the flag represented Uganda’s vegetation, while the blue represented the Nile River, which flows through the country from the south to north. The gold represents the sun, while the crested crane is Uganda’s nation emblem’ (Figure 5).Footnote 57

Figure 5. The national flag of the Democratic Party. The proposed designs for Uganda’s post-colonial flag reflected the colours and patterns of Uganda’s last colonial political parties. The country’s first post-colonial flag featured the party colours of the DP, notably green. The eventual and final flag donned the colours of the UPC and KY: black, red, and yellow. Source: artistically reproduced by Saleh Ssennyonjo.

Once the committee announced its recommendation, Uganda’s business sector busied itself with marketing Uganda’s national banner. The Uganda Argus contained hundreds of purchasing advertisements for flags, pennant streamers, and hardboard shields with the country’s new national colours.Footnote 58 One could purchase a drop banner with a blue top over a gold crested crane with a tail of blue and green.Footnote 59 Multiple sizes and varieties were available for individuals and businesses to purchase. At Drapers Limited, for instance, one could purchase 3ft x 2ft national flags for 41.10 East African shillings, wool car flags for 8.95, or plastic hand flags for 2.75.Footnote 60 By September 1962, the decorations for Uganda’s independence celebrations were produced by a team of 200 workers with ‘an undesignated Asian firm in Industrial Kampala’.Footnote 61 To build upon the excitement of Uganda’s new flag, theatre owners also capitalized on the moment. In Kampala’s cinemas in early September 1962, Duilio Coletti’s Under ten flags was screened, which portrayed a German ship’s utilization of different flags and disguises to out manoeuvre the British navy during the Second World War.Footnote 62

Dissenting activists criticized the flag. Uganda’s crested crane was looked upon with suspicion. One writer in Njeru, outside of Jinja, E. Benada, scathingly commented that the DP’s crane was ‘a grotesque caricature with a Khrushchev jaw for a beak, and something that looks like an anvil turned upside down for a crest’.Footnote 63 It was an unusual criticism against Uganda’s foremost anti-communist party. According to Benada, Ugandans ‘do not want distorted incompetencies that pass for so called modern art in our flag’. The Protestant centrist E. M. K. Mulira and the intellectual Rajat Neogy co-authored a piece in the national press, arguing that Uganda’s crane was ‘not entirely free of semi-colonial associations’, recalling the crane’s use in Uganda’s flag from 1914 onward. The two proceeded to complain that Uganda’s crane was being overly commercialized by Kampala’s entrepreneurs, who now used the crane to scandalously market cigarette brands, hotels, and restaurants.Footnote 64

Members of the UPC argued that their views on the national flag were completely ignored. The Munyankore litigator Grace Ibingira, who served in numerous key roles in the UPC, including secretary-general during the mid-1960s, suggested that the DP had selected green and white because it was their party’s primary colours.Footnote 65 The DP responded immediately with printed rebuttals and a series of public talks in Kampala.Footnote 66 The Democratic chairman of the National Flag Committee, William Senteza Kajubi, criticized Ibingira. After expressing his shock at the publication of Ibingira’s article in the Argus, Kajubi noted that the UPC attorney only showed up on two occasions during the committee’s ten days of deliberation. Ibingira arrived only toward the very end, ‘when the question of the national colours had been decided and only the design had to be discussed’.Footnote 67 Kajubi noted: ‘The colours of green, blue and gold were unanimously agreed upon by all those who attended the meetings, including the other representatives of the UPC. These three colours were selected not to represent certain political parties, but to reflect particular aspects of our country.’Footnote 68

Despite Kajubi’s retort, Ibingira’s accusations were not without reason. As much as partisan DP historians tried to dissociate their vision for the national flag from the party’s, their explanation of the proposed national colours consistently reworked the DP’s literature and ethos. Whether talking about the flag of the DP or Uganda’s proposed national flag, DP activists argued that green represented the hope of political change, the prophetic unravelling of Uganda’s skewed order (Figure 6). In his autobiographical reflection on the early beginnings of the DP, partisan Lwanga Lunyiigo recalled: ‘A party motto – TRUTH AND JUSTICE was coined and a party flag unfurled – the White and Green flag, the white representing perseverance and the green, hope – a truly prophetic package!’Footnote 69

Figure 6. Benedicto Kiwanuka hoists the Democratic Party’s flag, likely after the party’s electoral victories in 1961. Source: Benedicto Kiwanuka Private Papers, Kampala.

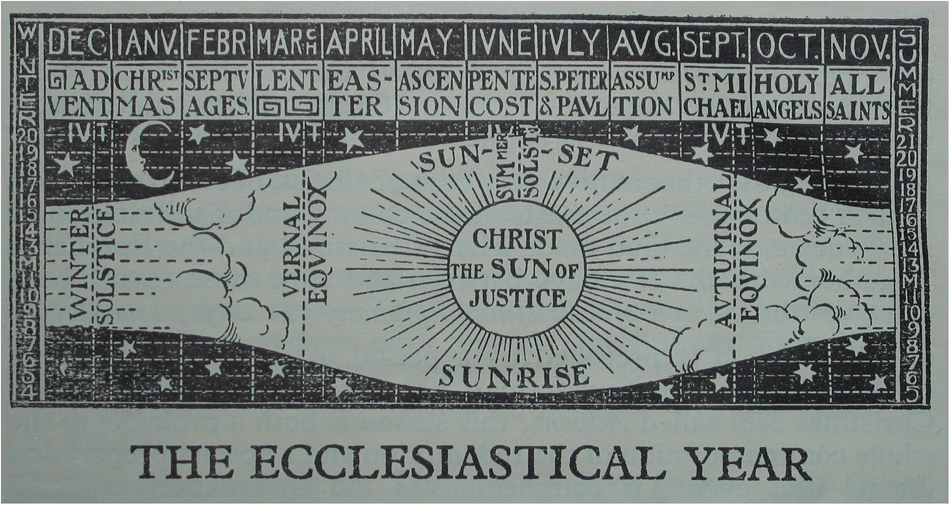

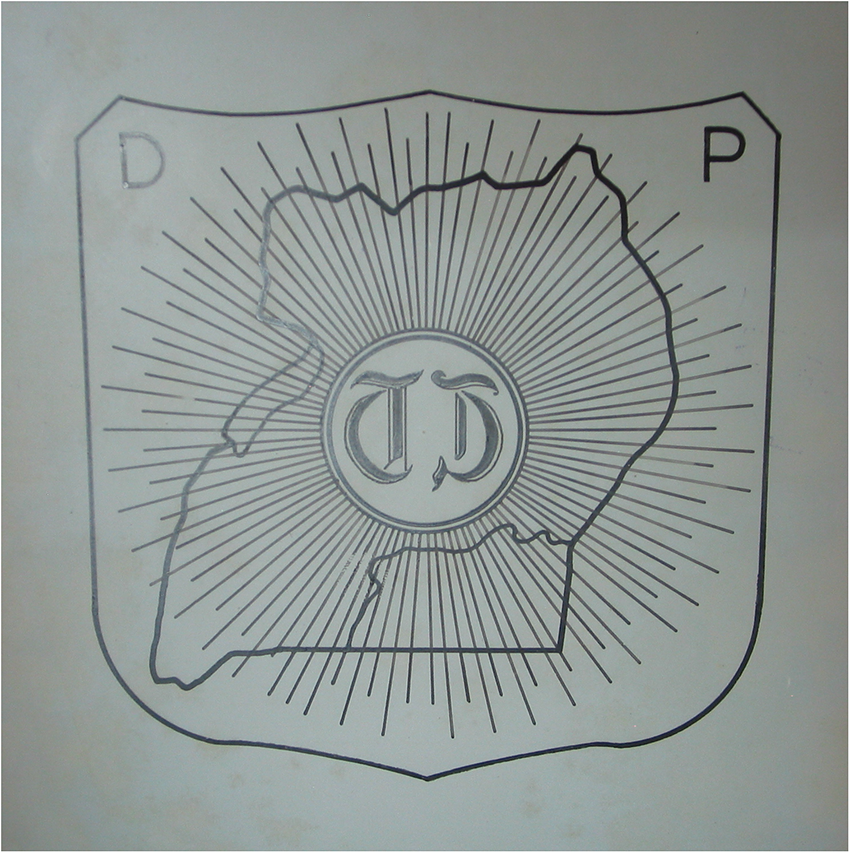

As a devout Catholic, Kiwanuka had also drawn from Buganda’s Catholic material culture in 1959 to develop the party’s symbols and his thoughts about national emblems. One of the DP’s principal logos incorporated the sun, whose light blanketed a map of Uganda. In the centre of the sun, the letters ‘T’ and ‘J’ were placed, an abbreviated form for truth and justice. Kiwanuka’s private library and papers show that the imagery drew directly from the Catholic Missal, which included an illustrated ecclesiastical year that revolved around ‘Christ, the Sun of Justice’.Footnote 70 The Party’s logo identically replicated the pattern of the missal’s sun and its rays (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. The ecclesiastical year, in Benedicto Kiwanuka’s daily missal (Dom Gaspar Lefebvre, OSB, Saint Andrew daily missal with vespers for Sundays and feasts (Bruges) (housed in Benedicto Kiwanuka’s private library).

Figure 8. Emblem of the Democratic Party. The design incorporated the Christ monstrance of Kiwanuka’s missal, c. July 1959. Source: Benedicto Kiwanuka Private Papers, Kampala.

Kiwanuka also communicated to the Catholic missionary Tarcisio Agostoni, who worked in northern Uganda, that the DP needed to develop imagery that portrayed the opposition ‘as darkness’.Footnote 71 Agostoni argued that ‘the sun is equal for all: it rises for all and sets down for all. Jesus himself when pointing out that the Father in heaven loves all men indistinctly, he said tha[t] God let the sun to rise over the good and over the sinner in the same time without distinction’.Footnote 72 Without God’s light, ‘there is no life, not heat, no crops, no rain no light on earth [sic]’. Similarly, continued Agostoni, the DP, as God’s political instrument on earth, would foster the economic and industrial development of Uganda.

The colours, rays, light, and patterns of the DP aimed to symbolize God’s blessing on Kiwanuka and his party. Symbols were remarkably versatile and could be adapted for party and national purposes. But there was more at stake in party iconography and a national flag than symbolizing green pastures, white tranquillity, blue rivers, and golden-crested cranes. The patterns accentuated God’s work in Uganda: the possibility of political salvation and economic liberation. By incorporating the DP’s colours, Kiwanuka and his Catholic allies reimagined a post-colonial state no longer anchored in Protestant spiritual authority.

V

Behind waving banners were deeper reflections about God, colour, and political order. By looking closely at how colours were infused with theological meaning, we can develop new ways of thinking about how hues were politically theorized in the intellectual histories of late colonial Africa. Debates about flag colours were not merely the outcome of decolonization. Nor was flag production simply a political exercise to complete a checklist toward legitimate state formation. Deeper spiritual epistemologies – shaped by decades of sectarianism – resulted in fundamentally different ways of understanding the moral significance of hues.

Following the DP’s electoral victory in March 1961, Buganda’s ruling government boycotted national politics. In partnership with the UPC, the newly formed Kabaka Yekka party and the Buganda government orchestrated a second national election on the eve of independence. The fanfare of the election included KY activists hanging the DP flag in effigy. KY and the UPC brokered an arrangement whereby only KY would stand for seats in Buganda, and the UPC for those outside of Buganda. The arrangements brought about the desired outcome. During a second round of elections in early 1962, KY won 65 out of 68 seats in the Lukiiko (Buganda parliament), which then forwarded 21 KY representatives to the National Assembly. The kingdom of Buganda had maintained its insistence on indirect appointments to the national body. Beyond Buganda, the UPC secured 37 seats to the DP’s 22 seats.Footnote 73 After the elections, Milton Obote was appointed prime minister, ousting Benedicto Kiwanuka from his short-lived position.

Once in power, the UPC quickly moved to change Uganda’s national flag. They legitimized the decision by citing technical challenges concerning the production of the DP’s design. It was argued that the DP’s flag needed to be approved by ‘technical experts in Britain’.Footnote 74 The UPC representative, Grace Ibingira, argued that the DP’s particular shade of green ‘will fade in a tropical climate and that the shade of blue cannot be adequately reproduced in the material suitable for flags’.Footnote 75 He continued: ‘In light of this advice, given by the technical experts, the Government has decided the design shall be reviewed in order to avoid these difficulties.’Footnote 76

The UPC’s new flag committee was chaired by Ibingira. It soon recommended that Uganda’s national flag have horizontal stripes, removing the earlier vertical design. The latest national colours would be placed sequentially on a six-striped banner: black, red, yellow; and again, black, red, yellow. The flag would maintain the crested crane superimposed on a white circle. The UPC suggested that black, red, and yellow represented ‘the sunshine and the brotherhood of man’.Footnote 77 Contrary to what Kiwanuka, Kajubi, and Agostoni wished, God’s light in post-colonial Uganda would be channelled through the UPC. The new flag was advertised in the Uganda Argus on 16 June, less than three months after the DP had displayed theirs (Figure 9).Footnote 78

Figure 9. Uganda’s new national flag featured the party colours of the Uganda People’s Congress and Kabaka Yekka: red, black, and yellow. It was first advertised in the national press in June 1962.

The UPC quickly began rehearsing the hoisting of Uganda’s new national flag, the difficulties and delays of which created a spectacle.Footnote 79 The Union Jack was eventually lowered, and the new flag was raised during a ceremony at 11.45 pm on 8 October 1962. According to one account, the event at Kololo Stadium attracted over 50,000 people, who ‘stood in silence’ as the ceremony unfolded.Footnote 80 In the press, writers and companies rejoiced as Uganda would now ‘hoist the National Flag among those of other nations at the United Nations’.Footnote 81 Nyanza Motors, similarly, ‘pray[ed] that the Flag of Uganda may fly high in the Comity of Nations’.Footnote 82

But prayers did not quell public debates about the flag. Writers with the Uganda National Congress, Uganda’s oldest political party, praised the ruling government for adopting the colours of Uganda’s oldest national party but asserted that Uganda’s head of state should be one of Uganda’s pre-colonial monarchs.Footnote 83 One Catholic activist in western Buganda, Kostante Lwango, argued that ‘the mere hoisting of the Uganda flag will be meaningless’ if Ugandans fail to ‘respect the dignity of his fellow man regardless of his standard’.Footnote 84 Lwango went on to note that Catholics and members of the DP were being discriminated against in public hospitals.Footnote 85 In the northern Ugandan town of Lira, one writer, who designated himself anonymously with the initials K. C., lamented the treatment of Uganda’s flag after the independence ceremonies: ‘Now the newly elected Uganda Government says that everyone must honour our national flag, but if some people tear, throw and steal those flags as I mentioned above then what we should mean an honour or an insult? Truly, it is a great insult to our nation.’Footnote 86 As opposed to serving as a single point of reference around which to animate national spirit, Uganda’s waving banner illustrated just how varied political opinion was about authority and political decorum throughout the country on the eve of independence.

For their part, the DP refused to acknowledge the national flag, the creation of which dominated Uganda’s first National Assembly debate. One DP activist argued that Uganda’s new flag contained UPC and KY colours, asserting further: ‘[If that] [i]s…cooperation in a progressive society, Uganda has no hope of a survival of a two party democratic system.’Footnote 87 The DP legislator, Senteza Kajubi, was more forceful: ‘The national executive of the DP deplores and protests in the strongest possible terms against the Government’s unilateral and completely arbitrary action in disregarding all recommendations made by the legally constituted committee set up by the Governor in Council to consider the question of the national flag.’Footnote 88 To sustain his argument, Kajubi walked his audience through various tropical nation-states that incorporated green into their national materiality, including India. He argued that suggesting that green was technically disadvantaged due to warmer climates was absurd. Regarding blue, he reminded the audience that the uniforms of Uganda’s colonial police force and the Union Jack were both blue. He underscored the unintended consequences of the UPC’s decision: ‘We cannot afford to have a new flag each time a new government comes into power, and although the colours have been chosen for other reasons we cannot disregard the political affiliations that they have.’Footnote 89

In parliamentary debates that unfolded over several days, the question of the national flag continued to instigate open protest. The Opposition member J. S. M. Ochola demanded that the UPC produce one piece of evidence to demonstrate that the DP’s colours would fade – any more than the UPC’s – with exposure to the sun.Footnote 90 He called attention to the flags of Tanganyika and Sudan, which featured green. After mistakenly referencing the use of green in the Union Jack, his comments were silenced by mockery and laughter. Once the laughter dissipated, he stated that he failed to see how Obote, ‘the most evil minded person[,] can say that the original committee was either DP or UPC and that [the new committee] represented anything but the national feelings of Uganda’.Footnote 91

Debates about the flag encompassed more than reflections on the science of blanching and political representation. There were noticeable discourses surrounding aesthetics and symbolism. After Ochola concluded, Grace Ibingira walked onto the floor and waved both flags above his head. During the performance, he noted: ‘Anyone who thinks that this dull thing (pointing at the old design) is better than this (holding up the new flag) must have something wrong with his aesthetic sense.’Footnote 92 The DP only insisted on the supposed illegitimacy of the new national banner, Ibingira continued, because they were ‘persecution mania ridden’. They were a party that ‘wanted everyone to wear white and green as well’.

The colour black was especially contentious. One UPC activist argued that black represented the voice of God.Footnote 93 The DP, by contrast, argued that the colour signified death. The UPC’s rationale was shaped by a particular Protestant reading of the Bible, especially the Old Testament. The Hebrew Bible often associated darkness with theophany, or God’s presence, spanning from the Exodus narratives to the construction of the Solomonic Temple.Footnote 94 The earlier Jewish association of darkness with God’s presence shaped how early Christian writers described God’s presence during Jesus’ crucifixion, which unfolded within the envelopment of dark clouds. Throughout the first century, canonical writers, notably St Paul, associated light with the appearance of Satan and demons, not God.Footnote 95 By the fourth century, though, Christian thinkers’ approach had shifted. Following debates about substance and the Trinitarian Godhead, Orthodox theologians with imperial support associated substance with light and light with God.Footnote 96

The Protestant prioritization of the study of the Bible enabled Ugandan converts to move back beyond the fourth century CE, by contrast, to an earlier time when God spoke to his people in darkness. The annotated Bible of the Protestant activist Ignatius Musazi, who co-founded the Uganda National Congress, specifically underlined I Kings 8:12. The text reminded readers that in the past, God dwelt and spoke in ‘thick darkness’.Footnote 97

A larger literary corpus shaped Kiwanuka’s theology of Black. Kiwanuka was wary of the colour scheme of the UPC and Uganda’s new flag, including its incorporation of black. This warrants emphasis, as Kiwanuka’s thinking does not easily conform to how many African intellectuals approached Black identity during the 1950s. Activists like Kwame Nkrumah and Milton Obote saw in black material culture a way to celebrate and champion Black political identities in a world of racial violence and colonial discrimination.Footnote 98 Similarly, in the context of Sudan, Christopher Tounsel has convincingly shown how Blackness and Christianity ‘became dominant identities that southerners of different ethnicities used to distinguish themselves from an enemy that was often framed as Arab and Muslim’.Footnote 99 Kiwanuka, by contrast, deployed the anti-Black rhetoric of the classical canon to criticize Obote’s public authority.

Kiwanuka’s annotated library shows that by 28 June 1953, he was reading the works of Frederick William Faber, an Anglican songwriter who had converted to Catholicism during the mid-nineteenth century. Faber’s work, The creator and the creature, specifically used the metaphor of black to signify the loss of childhood innocence and divine separation. Black, for Faber, captured the weightiness of growing old, of becoming bitter and cynical with time, and God’s judgement on the unrepentant:

But when we cease to be children and to be childlike, there is no more this simple enjoyment. We ask questions, not because we doubt, but because when love is not all in all to us, we must have knowledge, or we chafe and pine. Then a cloud comes between the sun and the sea, and that expanse of love, which was an undefined beauty, a confused magnificence, now becomes black and ruffled, and breaks up into dark wheeling currents of predestination, or mountainous waves of divine anger and judicial vengeance, and the white surf tells us of many a sunken reef, where we had seen nothing but a smooth and glossy azure plain, rocking gently to and fro, as unruffled as a silken banner.

Kiwanuka’s copy of the book included two comments in this specific section, demonstrating the closeness with which he reflected on its meaning and implication.Footnote 100

Into the mid-1960s, Kiwanuka associated black with social and theological depravity and the collapse of democracy. On 2 August 1967, he delivered a speech to the Students Guild of Makerere University College.Footnote 101 In section 13 of the ten-page address, he explored the veneer of democracy: of superficially maintaining institutional governance while leaders and presidents ‘put themselves above the law’.Footnote 102 In such a society, Kiwanuka noted: ‘[m]en and women are thrown into gaol at the caprice of a single person. A local Police Commander may arrest and detain a citizen at the request of another, because of a dispute over a girl; or because he owes that other some money and the other is tired of being constantly bothered about it.’Footnote 103 Once incarcerated, Kiwanuka continued, one’s partner does not know when – or if – their loved one will return. The courts are unavailable, ‘and your future is as black as that of the devils in Hell’.

Kiwanuka’s ideas were shaped by the books he was reading. The concept of black devils in hell resonated with the medieval writer Dante Alighieri’s description of Satan and hell in Inferno.Footnote 104 When Dante described the three faces of Satan, he used the colours black, yellow, and red – the colouration of Uganda’s national flag under the UPC government.Footnote 105 Kiwanuka encountered Dante during his education, and his remaining library shows that Dante’s philosophy was cited to help explain the development of modern political thought in R. H. S. Crossman’s Government and the governed, among Kiwanuka’s most annotated texts from the period.Footnote 106

If black devils provided a literary or theological context for explaining the horrors of imprisonment to Makerere’s student body, black could also be used to think more broadly about social isolation, violence, or, again, death. In his 1953 reading of Homer’s Iliad, Book I, for instance, Kiwanuka noted the anger and ‘black passion’ that caused the eyes of Agamemnon – who was killed by his wife’s lover – to become ‘like points of flame’.Footnote 107 The colour black had similarly negative associations in the Greek poem, including the ‘black look’ of Achilles.Footnote 108 Kiwanuka’s library also shows that he studied Percy Shelley’s poem, ‘Ode to the West Wind’, which associated loss and moral orientation with pigmentation. The poem was published in 1820. The opening tercet recounted the death of leaves in autumn. Yellow, black, and red – the principal hues woven into Uganda’s national flag – described ‘pestilence-stricken multitudes’ and the ‘dark wintry bed’.

Beyond his familiarity with Western literature, Kiwanuka’s conception of black was also shaped by the international politics of the period. In the Ugandan press, activists noted that the donning of black flags in the Yemeni port city of Aden signified ‘the death of freedom’.Footnote 109 Kiwanuka also associated black with the destructive policies of Germany’s Nazi state and the Blackshirts of Mussolini’s Italy. In his late colonial political commentary, ‘1962 Uganda Elections’, Kiwanuka commented twice on the violent policies of the two fascist regimes. In the first instance, Kiwanuka argued that the DP had been marginalized in national politics because of the problematic association of their movement with public Catholicism, an error that the Lukiiko and the Colonial Office failed to correct. Likewise, he continued, ‘Hitler and Mussolini could not have risen to those heights from where they unleashed the most devastating war mankind had known had the League of Nations, which in our case is the Colonial Office, behaved differently.’Footnote 110 In a second context, Kiwanuka underscored the untrustworthy leadership qualities of Hitler and Mussolini, both of whom ‘throve on the deceit in their time’.Footnote 111

By thinking closely about competing political theologies in late colonial Uganda, we see just how philosophically complex approaches to colours and pageantry could be. Strong feelings about decorum were animated as activists combed their Bibles and libraries, looking for ways to bolster and undermine the authority of political parties. As much as flags were a claim on public space and state resources, they signified sweeping efforts to standardize specific moral visions of light and pigmentation.

VI

With much at stake in maintaining Uganda’s flag, the UPC passed laws to protect and regulate it by September 1962, one month before independence. The law aimed to ‘provide for the punishment of anyone found guilty of ridiculing or bringing into contempt the flag or the coat of arms’.Footnote 112 The law also provisioned a maximum sentence of two years for abusing the flag and deportation for non-citizens who desecrated it. A fine of up to 1,000/- and six months’ imprisonment would be applied to businesses and traders who used the national flag without permission.

As the new principal symbol of the state, the UPC distributed the flag throughout Uganda. Flags were hoisted throughout the country to assert the power of Uganda’s newly formed, independent state and solicit political unity. Like Uganda’s nineteenth-century state builders, colonial officials, and international diplomats, Obote mandated that his vehicle be accompanied by a flag, which, according to Abu Mayanja, evoked ‘friendly, open-handed waves’, the hand gesture of the UPC.Footnote 113 When three of the DP’s members of parliament crossed the floor during the mid-1960s, they were keen to note that they did so for the purpose of ‘forget[ting] our past bitterness and differences and join[ing] together as brothers and sisters under one flag’.Footnote 114 Uganda’s flag was intentionally placed on Apolo Kaggwa Road in Buganda to symbolize the state’s authority over the country’s most powerful kingdom.Footnote 115 In Kigezi, on the border of Rwanda, Uganda’s new flag accompanied the military, which demonstrated ‘the determination of the Government to maintain the peace along our frontiers’.Footnote 116 And in Acholiland, DP activists brought a formal case against the secretary general of the district council, W. O. Lutara, after his car was seen sporting a UPC flag in the parking lot of his home.Footnote 117

The flag of Uganda’s newly formed post-colonial government was unable to unquestionably command allegiance or replace party banners and partisan symbols. Throughout Buganda during the early 1960s, communities continued to hoist the kingdom’s flag above Uganda’s. KY organized dozens of parades and victory marches throughout the early 1960s, where cars, buses, and lorries were decorated with leaves, twigs, and brown and yellow KY flags.Footnote 118 In one case, the KY activist ‘Jolly Joe’ Kiwanuka demanded that everyone in Buganda boycott Benedicto Kiwanuka’s swearing-in ceremony after a DP activist dared to remove a KY flag from Buganda soil.Footnote 119 The proliferation of royal patriotic banners in Buganda compelled the eastern Ugandan DP representative for Sebei and Bugisu to argue that ‘the national flag should be withdrawn from Buganda’.Footnote 120

Political parties throughout the 1960s accused each other of turning ordinary social functions into opportunities to distribute party propaganda and hoist party flags, whether at government sites, markets, weddings, funerals, or public schools.Footnote 121 During the late 1960s, the DP president for the Bukedi District Branch, S. D. Orach, drafted a lengthy letter to the editors of Uganda Argus and the vernacular newspapers Munno and Taifa Empya. Orach’s letter challenged the political credibility of the Muslim activist Haji B. Wegulo, the latter of whom had accused the DP of consistently taking the law into their own hands in eastern Uganda. Orach refuted Wegulo’s claim that the DP was guilty of ‘turning market gatherings, weddings, burials, and Ceremonies and beer parties into DP political rallies’.Footnote 122

Late colonial Uganda constituted a moment of proliferation for regional flags and party symbols, reflecting the various political projects circulating during the period. The separatist kingdom of Rwenzururu created and hoisted its flag of independence to distance itself from Uganda and the kingdom of Tooro. To marshal Kisoga solidarity and silence Sebei secessionists, patriots in Busoga also hurried to select ‘suitable colours’ and symbols for their newly created flag.Footnote 123 In the northern Ugandan township of Lira – the political power base of Milton Obote – the UPC had created and distributed their party’s symbol, an open hand, and costumes sewn with fabric dyed in the UPC colours of red and black. Party costumes were kept hanging in the office of government officials, should they be required at a moment’s notice. The material culture of the UPC was comprehensive. Indeed, the UPC produced miniature costumes for babies ‘in case a mother brings her child along’.Footnote 124

In the same area, the DP’s symbols and banners raised controversy. In 1957, Uganda’s Legislative Council created the terms and by-laws for selecting party symbols. The Elections Ordinance of 1957 noted: ‘For the purpose of assisting persons to identify candidates when voting, each candidate shall be entitled to associate himself, while electioneering, with such symbol as the returning officer shall allot to him.’Footnote 125 Clear guidelines regulated the display of flags and materiality:

No person shall in a polling division furnish or supply any loud speaker, bunting, ensign, banner, standard, or set of colours, or any other flag, to any person with intent that it shall be carried, worn, or used on a motor car, truck or other vehicle, as political propaganda, on polling day, and no person shall, with any such intent, carry, wear or use, on a motor car, truck or other vehicle any such loud speaker, bunting, ensign, banner standard or set of colours or any other flag on polling day.Footnote 126

By 1958, Uganda’s election committee had selected thirty-two symbols from which registered parties could identify their candidates.Footnote 127 ‘These were selected’, one report noted, ‘on the basis of being easily identifiable by the bulk of the people and yet without any particular local association such as clan affiliation.’Footnote 128 The shortlist of symbols included, although was not limited to, a key, a motor car, a box of matches, a bicycle wheel, an open book, and a hut. In Lango, though, the parochial character of the symbols – or the ‘local association’ – was not as readily dismissed as the committee suggested. The symbol selected by the DP was a farming hoe. However, UPC activists noticed that the DP’s hoe was Kiganda in design, not Nilotic. The UPC activist, Mr Otim, observed that ‘the Langi use a spade-like implement and they work with it by making a pushing, rather than a chopping movement’.Footnote 129 Otim continued: ‘Some people do not like this hoe symbol…They say it is a Baganda-type hoe. It is not that they do not like the Baganda. But they do not like what the Baganda are trying to do about breaking away from the rest of Uganda.’Footnote 130 A Kiganda hoe symbolized the southern control of agricultural production throughout northern Uganda.

The fragmentary production of flags and party symbols reflected and embodied the regional character of national politics in late colonial Uganda. Activists, colours, flags, and symbols highlighted and reinforced much older debates about religious loyalties and parochial power. It was not without reason that both the UPC and DP destroyed each other’s flags. At the UPC’s headquarters in Kampala, the DP flag was publicly burned.Footnote 131 In Gulu, three UPC supporters climbed the Tree of Liberty to pull down a DP flag.Footnote 132 By contrast, DP taxi drivers were accused of driving around the district and destroying UPC flags in Busoga.Footnote 133 Various flags commanded allegiance during Uganda’s national moment. Creating a national banner deepened political fractures, redirecting party loyalties away from the state.

VII

This article has shown how far-reaching debates about flags, philosophies of colour, and party symbols animated politics in colonial Uganda. Competing flags served as focal points around which activists disputed and engineered authority. Arguments about flags and material culture were principal motors of Ugandan politics. The creation of parochial and national material culture raised equally complex questions about the meaning and associations of colour. Activists imposed their respective party’s colours onto Uganda’s national banner to signify the ownership of Uganda. By drawing from ideas about aesthetics, international politics, Christian liturgy, and Dante’s Inferno, intellectuals used national pageantry to imagine who would govern post-colonial Uganda.

Studying the politics of pageantry in twentieth-century Uganda helps us expand the empirical registers with which we write the intellectual histories of Africa. Aspiring colonial governments erected flags to signify ownership over contested areas among competing empires. Eastern African kings, converts, and chiefs created their own flags and ways of talking about and disputing their deeper meanings and histories. An intellectual history of flags is crucial because it opens new possibilities for thinking about political projects that were silenced by the state. And while the flags of failed parties were difficult to fly, triumphant national banners illustrated competing political visions just as much as they symbolized national unification. The winds of political change fluttered many flags.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their critical suggestions. I also thank Rachel Leow, J. J. Carney and Ssalongo George Lutwama Mpanga for their suggestions. Omissions remain solely my own.