On 21 February 1907, an ocean-liner carrying pilgrims from the Hijaz docked in Bombay. Since the city had long been a central node in Hajj networks, such an arrival would typically have gone unnoticed.Footnote 1 But flying from the mast of the SS Shah Noor was a strange pennant that prompted speculation as far away as Allahabad, where the newspaper The Pioneer mused about the meaning of ‘a green flag of goodly proportions’ that bore a white square inlaid with a green star.Footnote 2 Unknown even in the ports in Bombay, which had grown accustomed to naval insignia of all kinds, the peculiar ensign led some to wonder whether the ship had flouted nautical conventions in hoisting it. The resolution of this ‘mystery’ (as The Pioneer excitedly characterized the episode) immediately exposed peculiarities of its own.Footnote 3 It emerged that the ensign was not associated with any of the ship’s high-profile pilgrims, including the nawabs of Radhanpur and Bahawalpur,Footnote 4 but instead with an Irishman, one Lt. Colonel John Pollen, who had remained in the port city of Jeddah as his companions visited nearby Mecca. Telling tall tales about a universal language and the destiny of humankind, he had probably become something of a curiosity among the captains of the port, who banded together to elect him honorary admiral of the Jeddah fleet. As the nominal commander of some forty ships, Pollen had thus secured the right to choose an ensign for his next voyage. He selected a design that belonged to no one nation but instead to a language that could, he insisted, promote understanding across all nations (Figure 1). This ‘language of hope’, Pollen explained to audiences in India, was appropriately called Esperanto, or One Who Hopes.Footnote 5

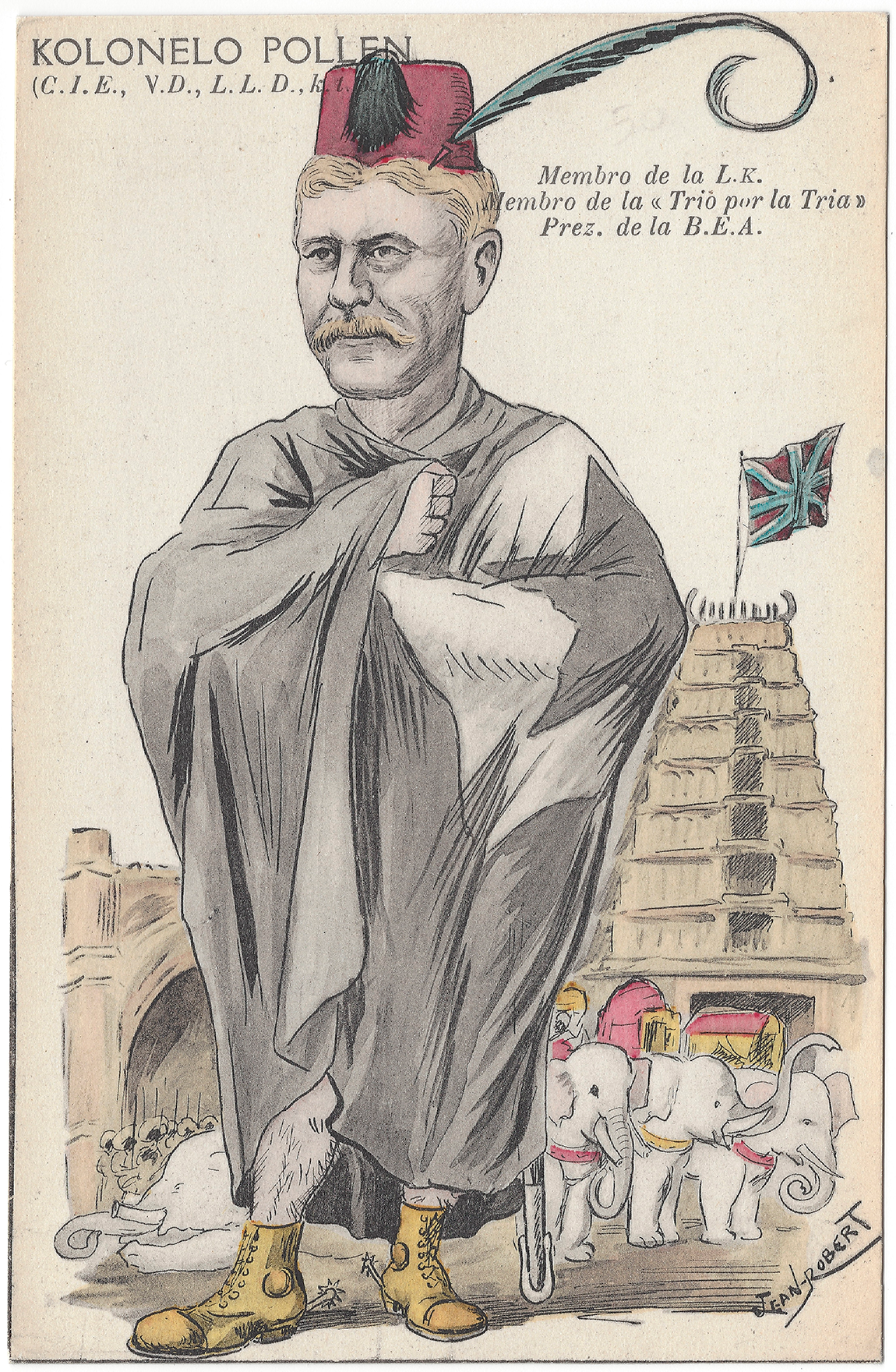

Figure 1. Postcard depicting a caricature of John Pollen in ‘Oriental’ dress against a fanciful Indian backdrop, captioned in Esperanto and signed by the artist Jean Robert. Published by Sino A. Farges, Esperanto Office, 36 Victor Hugo St, Lyon, n.d., c. 1910s. (Author’s collection.)

Pollen, who had recently completed a distinguished career in the Indian Civil Service and now returned to India as a private citizen,Footnote 6 did not introduce the Esperanto movement to India, where interest had been incubating among select groups for some time. His flamboyant arrival nevertheless marks the moment that a sizeable number of its residents, both Indian and British, became acquainted with Esperanto’s intriguing premise: that a constructed language, designed to be easy to learn, could be mastered within weeks. The ensuing rise of Esperanto in India has received scant scholarly attention,Footnote 7 in sharp contradistinction to the several studies addressing its contemporaneous popularity in Europe and other geographies.Footnote 8 This imbalance is excusable, to an extent, since Esperanto in India would enjoy less widespread and more fleeting popularity than it would elsewhere. Even so, India’s brush with the language reveals much about the broader movement and still more about Indian society at the zenith of British rule. The latter consideration propels this study, which uses the Esperanto movement to interrogate broad relationships between language and class in India as well as more specific relationships between Indian Esperantists and the wider Esperanto movement that courted them and that they courted in turn.

Probal Dasgupta has helpfully noted that modern Esperanto represents not just a language but a culture that transcends a grammar or lexicon.Footnote 9 The argument I develop here is not dissimilar insofar as it maintains that the Indians who gravitated to the early movement sought something beyond the language itself. But whereas Dasgupta refers to a discursive literary and intellectual tradition that has gestated within Esperanto communities for a century or more, the nascent movement that Indians encountered in the early twentieth century was far more malleable. They could use it in service of their needs, and what they needed most was an international community amid international precarity. The appeal of Esperanto in India thus had comparatively little to do with the relative simplicity of its grammar: it derived from its promise to anchor Indian learners or would-be learners to the subcontinent and the wider world in equal measure.

This versatility would resonate mostly strongly with Parsis and Theosophists, two frequently intersecting socio-religious groups that had deep roots in India but strong ties to other regions. It also explains the passion of Pollen himself, whose Irish background and Indian connections left him vulnerable to and alienated by shifting nationalist and imperialist forces.Footnote 10 Though Pollen – who dominates our available sources – should not eclipse more archivally elusive Indian Esperantists, nor should he be side-lined when many both within and beyond India accepted him as the face of the Indian Esperanto movement. My compromise is to write this study around him rather than about him (to tweak a distinction from Dipesh Chakrabarty) and to ask why a European figurehead should resonate so strongly.Footnote 11 The answer, I suggest, accords with what I believe resonated with Esperanto itself: its perceived Europeanness or, more precisely, its perceived near-Europeanness. Ostensibly global but bound both linguistically and institutionally to Europe, Esperanto emerged as an internationalist symbol with which certain Indian groups – regarded by most Indians as Europeanized and by most Europeans as Indian – could maintain and proclaim both parts of their identity. Esperanto, in short, was a language that was as much metaphorical as literal: it was a conceptual space in which and through which Indians could negotiate socio-cultural divisions and locate a community, and ultimately themselves, within an evolving empire and world.

I

Indians were not wrong to sense a European quality in Esperanto. Conceived as a language for all humanity, Esperanto was from its creation in 1887 intimately connected to trends in European society and political thought. Humphrey Tonkin and others have tied its emergence to the antisemitism experienced by its inventor, L. L. Zamenhof, who believed that a shared language could foster understanding across communities and nations.Footnote 12 The concept was nothing particularly new in Europe, since French and, increasingly, English were already widely spoken among the educated elite. But both languages were unsatisfactory for Zamenhof since they privileged the already-hegemonic nations in which they were natively spoken. Instead, a neutral language – one shorn of political associations – was necessary to ensure a balance of power and prevent the erosion of local languages and cultures. This was again not a proposition unique to Zamenhof. Others had already (and perhaps somewhat fancifully) considered reviving Latin, which had for centuries served as Europe’s lingua franca and was still widely taught in its classrooms.Footnote 13

Even the idea of an artificial language had gained some traction in Europe before Zamenhof developed Esperanto, most notably through the efforts of the German priest Johann Martin Schleyer, whose creation, Volapük, gained prominent and enthusiastic followers at conventions held over the 1880s.Footnote 14 But Esperanto was different from Volapük in critical respects, and its fortunes would be different, too. Whereas the latter emerged from a Catholic worldview (Schleyer attributed his inspiration to a vision), Esperanto was not tied – or at least not directly – to any one community or conviction. To be sure, Zamenhof’s Jewishness would, as Ulrich Lins has explored, often be erroneously applied to the language he created, fostering a supposed link between it and European Jewry that Joseph Goebbels and others would later exploit.Footnote 15 Ostensible connections with communism would prove no less intransigent.Footnote 16 But for its supporters at any rate, Esperanto knew no communal, national, or even ideological boundaries.

A still more important difference from Volapük lay in the structure of the language itself. For Zamenhof, rejecting French and English as an international language was necessary to destabilize cultural and geopolitical hegemonies, but it was also an opportunity. Learning French or English (or certainly Latin) required years of study; a language that could be learned quickly and easily would, by contrast, be immediately available to all. Here, Volapük had come up short: although its grammar is more regular than in most European languages, its fourfold case system and heavy agglutination recall the more challenging aspects of Schleyer’s native German. In creating Esperanto, Zamenhof sought to avoid such complexities by minimizing inflection for person, case, and grammatical gender and anchoring the grammar around sixteen simple rules.Footnote 17 Morphologically, too, Esperanto would contain a limited number of roots that could generate a full lexicon through the predictable application of affixes. The result was far simpler than Volapük but nevertheless shared with it a fundamental reliance on European languages. This is especially pronounced in the lexicon, which contains mostly Latin and Germanic elements with a smattering of Slavic and Greek.Footnote 18

This heavy indebtedness to European source languages was a direct consequence of Zamenhof’s belief that prospective learners could absorb the language more quickly if they did not need to acquire vocabulary from scratch. The assumption that these individuals would already know European languages further underscores the Eurocentric slant of the project, and indeed, Esperanto was in its earliest years largely a European phenomenon: initially restricted to Eastern Europe (Zamenhof wrote his first work on Esperanto in Russian), interest in the language soon extended to Western Europe, gaining visibility at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris and culminating in the first World Esperanto Congress in northern France in 1905. Esperanto would thereafter thrive in Western Europe, a region that would host eight of the nine Congresses that met before the First World War.Footnote 19

But despite the European dimensions of Esperanto both as a language and as a movement, early Esperantists were not limited to Europe. Esperanto societies would soon emerge in Latin America and North Africa,Footnote 20 but especially notable is the case of Japan. One of the country’s earliest Esperantist journals, Japana Esperantisto, reported that committed Japanese learners with no prior knowledge of a European language could acquire Esperanto in a single month – a claim that was picked up by and celebrated by British Esperantists immediately prior to Pollen’s voyage to India.Footnote 21 Although the European flavour of Esperanto surely appealed to Meiji-era Occidentalism, clear political linkages are hard to draw between early proponents of the movement in Japan. Ian Rapley notes that their number included an ardent Russophile, a nationalist historian, and an anarchist, leading him to conclude that interest in Esperanto was not linked to any one movement but rather to the country’s prominence following the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5).Footnote 22 Japan’s victory had shocked most international observers, making Esperanto an ostensibly easy means for Japanese thinkers to speak to the world – whatever it was they wished to say – now that they had its attention.

II

The two factors influencing the popularity of Esperanto in Japan – interest in Europe and an enhanced role on the global stage – have clear analogues in India. But these parallel cases ultimately diverge, enabling us to locate the appeal of Esperanto in India with some precision. Indian intellectual engagements with Europe before the First World War tended to flow back to Britain owing to the realities of colonial rule. In the political realm, similarly, widespread calls for complete independence (Purna Swaraj) were still some years off, and even vehement nationalists usually sought to define or redefine India’s political status within the structure of the British empire. The prospect of dialogue with France, Germany, or Russia that drove many Japanese toward Esperanto simply did not apply to most Indians, for whom dialogue with Britain, their geopolitical gatekeeper, was of paramount importance. Better to invest in English, surely, than in a language few in Britain knew or even knew about.

It is therefore unsurprising that early Esperantists in India came from communities that were not particularly interested in learning English – either because they sought to challenge its hegemony or because they were already proficient in it. An example from the former (and rarer) is the Bombay-based French teacher Louis Peltier, whose embrace of Esperanto in 1903 positions him as the movement’s first documented supporter in the subcontinent.Footnote 23 I will speculate as to the reasons for his interest later on, but for now we might wonder whether he saw Esperanto as a middle ground in the battle between English and French for global influence, especially since we know from the work of Samuel Berthet that British authorities often regarded Peltier and other French instructors with suspicion.Footnote 24

What is clear is that by 1905 the movement was beginning to garner real attention in India. Not all of it was good: an article in an Indian newspaper, reproduced from The Times, argues that Esperanto visually resembles ‘a peculiar form of Rumanian’ and grammatically constitutes ‘a most annoying language’.Footnote 25 But others took to the movement with gusto, including I. B. Banerjea and T. Adinarayana Chettiar, who (based in Calcutta and Salem, respectively) are the earliest Indian Esperantists on record.Footnote 26 Esperanto groups would emerge that same year in Bombay and Udupi, the latter in the Mysore region where the early movement saw impressive growth.Footnote 27 This was especially true for the mining district of the Kolar Gold Fields, where the first Indian Esperanto journal, La Pioniro (The Pioneer), went to press in 1906.Footnote 28 Scattered references to the journal and the Kolar Gold Fields Esperanto Club that produced it allow us to sketch out the priorities of early Esperantists in India. One such reference appears in The Times of India, which, speculating as to why a mining district should take to an experimental language with such zeal, maintains that it is only logical that ‘an important industrial centre’ like the Kolar Gold Fields would seek ‘a means of bringing technical, commercial, and scientific men of all countries into touch with one another’.Footnote 29 The assessment is substantiated by statements from the Club itself, suggesting that the presumed benefits of Esperanto were not for those actually labouring in the mines. Its value instead lay squarely with the elite,Footnote 30 in this case with engineers who sought to engage with the international scientific community in which they saw themselves as participants.Footnote 31 The priorities of the Kolar Gold Fields Club anticipate those of the Esperantists who would follow. Unlike Peltier, whose connection to Esperanto presumably owed to teaching French in an anglophone political domain, Esperantists of the Kolar Gold Fields maintained that English – and, indeed, Britain itself – worked in tandem with Esperanto rather than in opposition to it. We see evidence for this British connection in its motto, taken from Milton and translated into Esperanto, and especially in its policy that only those who were already members of the London-based British Esperanto Association could be ‘real members’ of the Kolar Gold Fields Esperanto Club, all others being ‘only “group members”’ (nur ‘Grupanoj’).Footnote 32 Not surprisingly, therefore, the names of members who have come down to us – R. F. Vaughan, C. E. Jeffrey, Graham White, etc. – suggest a composition that was overwhelmingly, and perhaps exclusively, British or Anglo-Indian.Footnote 33

Things were not much different at the opposite end of the country, where in July 1906 another Esperanto organization was formed in Calcutta that comprised mostly local British or Anglo-Indian individuals.Footnote 34 Although it was far from the first such organization in India, its very name, the Esperanto Society of India, suggests that it saw itself as uniting or even subsuming all others. These all-India pretensions were apparently recognized by the Second World Esperanto Congress, which invited two Society members, C. S. Middlemiss and G. E. Pilgrim, to Geneva in August 1906 as the first representatives to the Congress from India.Footnote 35 In most practical respects, however, the society in Calcutta paralleled rather than superseded the one in the Kolar Gold Fields. Calcutta Esperantists’ answer to La Pioniro was La Stelo de l’Oriento (The Star of the East), which the Society aggressively distributed to English-language newspapers in the summer of 1907. The Englishman mercilessly mocked the gesture, writing dryly that ‘we have not yet progressed in the acquirement of that “universal language”, and we are therefore unable to appreciate its “simplicity of expression”’.Footnote 36 The Civil & Military Gazette similarly drew attention to a policy whereby those interested in Esperanto would need to pay the Esperanto Society before receiving promotional literature.Footnote 37

Emerging in parallel with these British- and Anglo-Indian-dominated groups were examples of strong Indian participation in the movement. Though we have little information about the organizations then arising in places like Agra and Punjab,Footnote 38 we do know that by 1907 an Anglo-Gujarati-Esperanto paper appeared in Surat and that Indians held all major leadership positions in an Esperanto group in nearby Jetpur.Footnote 39 This expansion of Esperanto in India explains the sense of optimism among Esperantists in 1906 and 1907 despite the bad press. What was more, the press was now not altogether bad. The Madras Weekly Mail noted ‘[a] large number of Esperantists…scattered all over India’,Footnote 40 a point predictably echoed by The British Esperantist, which, citing La Stelo de l’Oriento, declared (in Esperanto) that ‘our cause is progressing in India’.Footnote 41 Though its tone was breathless, The British Esperantist was right that Esperanto was on the rise, so much so that at least one Christian missionary attempted to ride the tailwinds of its popularity and introduce the language into a school curriculum in 1906, presumably eyeing its learners as receptive to her own message of global salvation.Footnote 42 While this example likely introduced the language to less-privileged groups, there is on the whole little evidence that the movement tended to include, or even to target, non-elite Indians. Among the first members of the Esperanto Society of India, we are told, were ‘government officials, military men, police officers, engineers, and educated Indians’,Footnote 43 and Esperanto organizations in India during this time differ only in the proportions allotted to these respective groups. These organizations were thus akin to many other clubs, institutions, and media and entertainment places that were dominated by whites but nominally open to Indians of certain backgrounds. As in these other spaces, knowledge of English also appears to have served as a means of social gatekeeping – although in this case somewhat ironically given the tenets of the movement.

That much of this information comes to us from and is celebrated in British Esperantist literature reveals how Esperantists in the metropole now felt compelled to demonstrate that their movement had found success not just in India but also among Indians. In describing one organization in Travancore, for instance, The British Esperantist writes that ‘only one of the members is European’ and excitedly adds that ‘soon we hope to be able to announce more details’.Footnote 44 This attempt to underscore Indian involvement must be located within a broader defensive campaign to represent Indians as participants in the British empire, a need that arose amidst increasing nationalist collaboration in India, epitomized by the Swadeshi movement and the public airing of frustrations with many British policies. Though such efforts would surely (and correctly) strike the modern reader as tokenistic and paternalistic, they were consistent with some British Esperantists’ tendency to see the British empire as an advocate for rather than an opponent of its vision of global amity. The belief that imperial structures could be utilized to forward Esperanto returns us to the moment that did more than any other to popularize the Indian movement during this time: John Pollen’s dramatic arrival in Bombay.

III

Pollen had arrived in a land in which he was in no sense a stranger. Records from his three-decade career in the Indian Civil Service detail his many posts, his rich knowledge of Indian history and languages, and his numerous Indian associates.Footnote 45 A family album depicting that time – generously shared with me by his descendants Sarah Almirall and William Tang – meticulously illustrates these connections, but it exposes, too, how much of his life in the Indian Civil Service had unfolded independently of Indian society (Figures 2–4). There is strong evidence to suppose that these divisions, deeply entrenched within the logic of imperialism, frustrated Pollen, whom sources represent as trying to draw nearer to Indian interlocuters in ways that would often challenge social expectations. (His predecessor in one of his posts, for instance, writes that ‘Indians found some difficulty in fathoming what was going on in what was clearly a very shrewd head, behind that benevolent smile.’Footnote 46) It is tempting, then, to see his post-retirement return to India as an attempt to renegotiate, if by no means eradicate, these divisions, a task that for him now seemed possible owing to his connections from the Service and the promise of Esperanto.

Figure 2. John Pollen (rear, second from right) attending the Fancy Dress Ball in Karachi, 13 October 1885. (Image from a family album of Sarah Almirall and William Tang, descendants of John Pollen.)

Figure 3. John Pollen (second row, fifth from right) with troops in India, unknown location, c. 1885. (Image from a family album of Sarah Almirall and William Tang, descendants of John Pollen.)

Figure 4. John Pollen (front centre) with companions during his India years, c. 1885. (Image from a family album of Sarah Almirall and William Tang, descendants of John Pollen.)

Pollen had publicly articulated a special relationship between India and Esperanto about a year before he hoisted the green and white ensign on the Shah Noor. After attending a lecture on Indian linguistics in London, he had mused to those present that Esperanto would become a global language within twelve years and would offer immense benefits to the people of India. His remarks had been immediately eviscerated by George Birdwood, an Anglo-Indian academic and administrator, who expressed that ‘Esperanto was most cumbrous and inefficient…[,] a jargon of insanity.’Footnote 47 Such raw intensity reflected Birdwood’s belief that Esperantists aimed to replace all languages, thereby stripping humanity of its linguistic richness. Pollen remained sanguine: ‘I have always welcomed attacks on “Esperanto” because I know it can withstand attack’,Footnote 48 he would later say.

Countering the misconception that Esperanto should or even could supplant Indian languages would prove central to the message Pollen took to India. He laid out his arguments during a breakneck lecture tour that took him to schools, colleges, societies, and YMCAs. Pollen supplemented his lectures with letters to the editors of The Times of India and The Bombay Chronicle in which he laid out his ideas, decrying the ‘profound ignorance [that] prevails’ regarding Esperanto’s purpose and emphasizing that, far from replacing Indian languages, it would promote their study and ensure their protection.Footnote 49 The logic, he explained, was that the streamlined experience of learning Esperanto could safeguard them from the degradation they would sustain as lingua francas. Illustrating the second point through racially charged examples that overlooked European maladroitness with foreign languages, he suggested that the Japanese were liable to destroy English and lamented the ‘Pidgin-English which the Chinese and the Hottentots have produced’. Esperanto, by contrast, was a shared domain that was ‘ready – nay willing – to be experimented upon’.Footnote 50 In representing Esperanto as the protector of both English and Indian languages, Pollen championed Esperanto as a meeting point for colonizer and colonized: a domain accessible to both and detrimental to neither.Footnote 51 The claim recalls what Guilherme Fians has, albeit in a very different context, identified as Esperanto’s capacity to be neither hegemonic nor counter-hegemonic but instead to offer a ‘linguistic alternative’ that sidesteps both poles.Footnote 52

But Pollen’s argument for Esperanto was not simply an argument for protecting other languages. Esperanto, he insisted, had a special relationship to India that hinged for him on two points, the first being that Esperanto was derived from the ‘best of Aryan languages’,Footnote 53 an idea that grew out of his insistence that the language was ‘really “reformed Aryan” and as such ought to commend itself to Indians’.Footnote 54 Whether deliberately or inadvertently, these remarks muddle two senses of the word ‘Aryan’. One is a now-outmoded designation for the entire Indo-European language family, whose Western branches, as we saw, Zamenhof mined for Esperanto’s lexicon and whose Eastern ones (which include most languages of Iran and northern India) he largely ignored. But ‘Aryan’ could also refer more specifically to the Eastern branch, now known as Indo-Aryan, instilling Pollen’s remarks with the false impression that Esperanto included Indic elements. Even if we give Pollen the benefit of the doubt and assume that he meant the more capacious sense of the word, we might ask why the ‘best of Aryan [i.e. Indo-European] languages’ should include several languages from Europe and none from India.Footnote 55

The second link Pollen drew between India and Esperanto revolved around the linguistic history of the subcontinent. He insisted that many Indians had already demonstrated their receptiveness to a common language through their use of Hindustani, a north Indian vernacular that was for him a regional forerunner to what Esperanto promised on a global scale: it had not, or so he claimed, supplanted local languages but rather enabled disparate groups to speak to one another.Footnote 56 Pollen, intimately familiar with India as he was, must have known that knowledge of Hindustani was limited beyond northern India; it was a regional lingua franca and not a national one. That he made no attempt to highlight Esperanto’s potential to do what Hindustani had not and ensure national communication underscores that its value for him lay in connecting Indians not with one another but with the world.

After all, it was only by connecting with the world through Esperanto that Indians could – or so Pollen insinuated during his tour – participate in global modernity. He would in later years make the point explicitly: ‘There is no reason why Esperanto should not prove to the civilized world what Urdu proved to “the warring world of Hindustan”.'Footnote 57 The linguistic parallel (if not its civilizational undertones) resonated in northern India, even among individuals with no apparent interest in Pollen’s broader message. Notably, in a speech delivered in Allahabad days before Pollen and the Shah Noor docked in Bombay, the political activist Muhammad Ali Jauhar characterized Indian Muslims’ use of Urdu as ‘a long established Esperanto handed down to them by their ancestors’.Footnote 58 The fact that he used the word ‘Esperanto’ at all suggests that the movement’s message had become newsworthy enough that Jauhar could trust his audience to get the reference; that he did so to refer to a shared language suggests that the particulars of that message were actually getting through.Footnote 59

Pollen’s belief in an Esperanto–Hindustani connection was shared by many British Esperantists in the metropole, notably by the Scottish shipping magnate Knight Watson and a certain ‘Yorkshire Esperantist’, the latter characterizing Zamenhof’s creation as ‘an imitation of the experiment so successfully made by the conqueror Akbar when he wielded the camp jargon of his polyglot armies into the Hindustani of our own day’.Footnote 60 Such statements reveal a blueprint for the Esperanto movement more than a history of the Hindustani language: the point was that just as the Yorkshire Esperantist’s (decidedly ahistorical) Akbar had promoted Hindustani in the sixteenth century, so too would someone of influence need to champion Esperanto in the twentieth. The goal of winning over such powerful individuals was surely one of the reasons Pollen visited spaces frequented by elite Indians, many of whom he knew from his years in the Indian Civil Service,Footnote 61 including the nawabs of Radhanpur and Bahawalpur whom we saw accompany him on the Shah Noor. Among his other acquaintances was Ranjitsinhji (r. 1907–33) – the maharaja of Nawanagar and the so-called father of Indian cricket – whom Pollen congratulated (in Esperanto, naturally) upon his accession to the throne.Footnote 62 Whether these particular individuals warmed to Esperanto is unclear, though we know that royals from Palanpur and Dharwar made generous donations to the cause and that Pollen would – on behalf of the aforementioned World Esperanto Congress at Cambridge – ebulliently thank Sir Muhammad Rasul Khanji Babi, the nawab of Junagadh (r. 1892–1911), for his ‘kind telegram of good wishes’.Footnote 63

The prominence that the Esperanto Congress afforded to Khanji’s telegram demonstrates how Esperantists identified socially prominent Indians as important for the movement in Europe no less than in India, a point that Pollen himself reinforced through the illuminated images he presented to the Congress purporting to show Indian maharajas enraptured by his mission.Footnote 64 This was a savvy promotion strategy: if Esperanto was to be regarded as a noteworthy international language, it needed noteworthy international supporters, and the figure of the Indian maharaja – so celebrated in the Orientalist discourse of the time – was guaranteed to garner public interest. This was especially so when the media were already primed to represent the Esperanto Congress as an exotic spectacle, with one journalist emphasizing how a ‘Turk and a number of Indians in national costume add considerably to the effect of this new kind of circus’.Footnote 65

Whether it was more to secure their influence at home or to utilize their novelty abroad, the emphasis Pollen placed on elite Indians was at the expense of other groups, who do not appear to have taken to Esperanto in any greater numbers than they did before his arrival. This is not to say that he did not extend overtures to less privileged communities. A year after returning from India (which he left with conspicuously little pageantry), Pollen outlined a plan by which lascars – a class of South and Southeast Asian labourers who sought work in the global shipping industry – could learn Esperanto at a local charity during their stays in London.Footnote 66 It is unclear whether the opportunity appealed to many lascars, though one imagines that few in this community, one of London’s most indigent, would have identified the language as a logical means of advancement. Pollen would later make a similarly unlikely proposal in 1915, when he identified Esperanto as a means by which Scottish prisoners could seek to improve their abject living conditions.Footnote 67 Neither scheme appears to have been implemented or, at any rate, successful.

As this cycling from India to the Indian diaspora to Scottish prisoners demonstrates, Pollen after his return to Britain would gradually, though never wholly, distance himself from India, the region where he had spent his career and later returned (in his words) ‘as a poor pilgrim, a pensioner’.Footnote 68 Though his obsessions seem to have floated rather freely during this time, they would soon coalesce around another region of long-standing personal interest: Russia. The story of Esperanto in Russia is very different from the one under consideration here and has in any case been the subject of some important scholarship.Footnote 69 Even so, understanding Pollen’s attraction to the country as an Esperantist helps us isolate what he had hoped to achieve in India. Pollen’s affections for the two countries were tightly intertwined: indeed, his fascination with Russia was in full force some two years before he boarded the Shah Noor, when he visited the country and witnessed the events of Red Sunday in 1905.Footnote 70 The interlocking nature of his interests is perhaps best summarized by his friend and fellow Slavophile Francis Petherick Marchant, who recalled how Pollen ‘used to say he worked at Russian grammar in middle age, when riding a camel in India’.Footnote 71 The Russian empire unquestionably held a certain cachet for Pollen, since it was there that the Esperanto movement was born. But while his new passion probably owed something to reverence – and certainly a great deal to inquisitiveness – it also recalled the factors that had persuaded him to champion Esperanto in India. Pollen’s arguments about the role of Hindustani in India could be easily transposed onto that of Russian in the Russian empire, and the international marginalization that Russia had sustained despite its large population and cultural prominence invites obvious parallels with the subcontinent.Footnote 72 And here, too, the broader structures of empire offered readymade means through which the Esperanto movement could be disseminated and its networks strengthened.

IV

Though details from Pollen’s biography can help to connect the disparate nodes of his eccentric career, his visit to India – bookended by his ostentatious arrival and his largely unnoticed departure – feels fleeting. And fleeting though it may have been, the intense media scrutiny it engendered brings an otherwise hazy local Esperantist movement into sharper focus. Records of his talks reveal that some who attended, like a certain Miss Engineer,Footnote 73 were already committed Esperantists and apparently spoke the language fluently. Similarly, advertisements that correlate with his arrival reveal that Esperanto dictionaries and a textbook were already available in India,Footnote 74 and a flurry of additional marketing over his visit suggests that such materials would only proliferate.Footnote 75

Pollen himself makes clear that he did not bring these texts to or even arrange for their publication in the subcontinent; they were instead products of local publishers, especially D. B. Taraporevala & Sons (in Bombay) and Thacker, Spink & Co. (in Calcutta),Footnote 76 to whom Pollen would refer individuals seeking Esperantist literature.Footnote 77 The cost of introductory texts was relatively cheap: seven annas for a book called First lessons in Esperanto at a time when a daily newspaper cost four annas and a play or novel cost eight.Footnote 78 More advanced materials were more expensive: A student’s complete text book in Esperanto was priced at one rupee, five annas (or three times that of First lessons), and a two-volume bilingual dictionary fetched two rupees, ten annas (or six times First lessons). This sharp price increase suggests that committed Esperantists were expected to offset the affordability of materials aimed at attracting the broader reading public – and specifically the English-reading public – to the movement. Pollen, for his part, had aimed at widening Esperanto’s reach across the demographic, a charge that took him to organizations like the Prarthana Samaj (a Bombay-based Hindu reform organization) and the YMCA and YWCA.Footnote 79 Since these organizations convened lectures on wide-ranging topics, their granting a platform to Pollen should not imply their acceptance of his message. And yet Pollen surely reasoned that these venues – each tied to imperial and even global networks – might show cautious interest in Esperanto’s promise to foster and fortify transregional connections.

Pollen also targeted two groups with members known to be Esperantists: Bombay Parsis (such as Miss Engineer) and the Theosophical Society.Footnote 80 The first a historically Zoroastrian community prominent in business and the other a mystical society fascinated by Western occultism and Indian religions, both groups had strong knowledge of English and deep ties to Western organizations, and, indeed, the Theosophists included many Westerners among their ranks. The Parsis’ and Theosophists’ long-standing interest in Esperanto is intriguing when we note that the French teacher Louis Peltier (whom we encountered as the first documented Esperantist in India) interacted extensively with both.Footnote 81 As many Parsis were themselves Theosophists, it is unclear who pushed whom toward Esperanto, or whether, as seems likely, interest in the movement derives not from any one group but instead from their dynamic interactions. (We might wonder, further, whether Peltier is unambiguously India’s first Esperantist or whether his affinity for the movement emerged from a broader dialogue in which he was only one participant.)

Whatever their contributions to the origin of Esperanto in India, the Theosophists and Parsis would, after Pollen’s departure, herald its future. For Theosophists, the embrace of the language would occur gradually but play out at the institutional level: though the Theosophist journal Sons of India stated in 1909 that it would ‘[f]or present…suspend judgement’ on Esperanto,Footnote 82 it at the same time commissioned an article on the topic from Jehangir N. Unwalla. The Society would later seem to lean into the movement, arranging for an Esperanto translation in 1913 of At the feet of the master, a foundational Theosophist text attributed to the teenage mystic Jiddu Krishnamurti.Footnote 83 One imagines that the language of Esperanto, theoretically available to all but actually known by few, might have appealed to an organization that regarded itself as at once universal and esoteric. At the same time, Unwalla, who was also a Parsi, pointed to a more mundane motivation. He claimed that for Theosophists ‘a common yet simple medium of intercommunication is an unavoidable necessity. That medium is Esperanto as has been proved without the shadow of a doubt by its success and adoption by persons of all classes in the whole of Europe educated and partly educated.’Footnote 84

The importance that Unwalla attached to Europe, both as an example that India might emulate and as a cultural domain to which Esperanto was intrinsically tied, differs from the emphasis he had laid earlier on ‘the utility of Esperanto among the hundreds of peoples living in India with their various dialects and languages’.Footnote 85 While by no means mutually exclusive, these two claims establish an unwavering allegiance to Esperanto as the throughline of his evolving rhetoric and echo Pollen’s emphasis on the global rather than local benefits of Esperanto. Indeed, Unwalla’s commitment to Esperanto would outlive his commitment to the Theosophical Society, with which he would part ways, possibly amid acrimony, in 1913.Footnote 86 By this time, he had already begun to advocate for Esperanto on its own terms. Developing a modest Esperanto programme at Central Hindu College, where he served as an English professor, Unwalla was in 1914 educating ‘about fifty or sixty students’ in the language,Footnote 87 seemingly addressing a concern, earlier articulated by Pollen, that Esperanto would only enter school curricula once it was entrenched in universities.Footnote 88 One of his students would write an article touting the merits of Esperanto for the leading Hindi journal Sarasvatī, reflecting – at least according to Esperantist sources – the interests of the journal’s editor, the Hindi literary giant Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi.Footnote 89

Paralleling Unwalla’s activities are those of his fellow Parsi and colleague at Central Hindu College, Irach J. S. Taraporewala (not directly related to the D. B. Taraporevala above).Footnote 90 A comparative linguist, Taraporewala recalled attending the International Congress of Orientalists in Athens in 1912, and his reflections merit quoting at some length:

I never felt the necessity of such a dear language as our Esperanto so powerfully as in Athens during the Congress. Officially five languages were allowed – English, German, French, Italian and Greek. The three opening speeches of the Congress were in Greek, but only very few of the members could understand them. During only one sitting, in a discussion regarding one subject, there were used four languages. The chief speech was in Italian; a German Professor criticised it in German; the chief speaker answered in French; and the president summed up the whole discussion in English. Only a few members were capable of understanding well all the four, and the majority could understand only one. Further comments are useless.Footnote 91

Taraporewala downplays that he had himself added to the multilingual melee, delivering, as related by Unwalla, ‘his “maiden speech” in Esperanto before a distinguished assembly of one thousand delegates’.Footnote 92 If his aim was really ensuring ‘understanding’, it is curious that he should deliver his remarks in a language less widely understood than the other five. But literal comprehension was of course not really his aim. Unwalla tells us further that Taraporewala spoke ‘dressed in his Parsi uniform, and as the only Indian there present he was welcomed and cheered enthusiastically by all’.Footnote 93 Unwalla emphasizes this point, illustrating how Esperanto enabled Indians from a particular social location to present themselves in the global spotlight. Taraporewala’s choice of Esperanto, like his choice of dress, marked him as different from his audience even as it challenged their expectations of Indianness. There would, after all, have been a measure of intelligibility in his words, the vast majority of which would have been recognizable to European linguists in meaning if not in form. The result recalls Homi Bhabha’s idea of mimicry (‘almost the same, but not quite’) and specifically his notion of ‘not quite/not white’.Footnote 94 Rosie Thomas has fruitfully extended the ‘not quite/not white’ concept to racial liminality in early Indian film, particularly to non-Indian actresses playing Indian roles in performances she interprets as simultaneously recognizable and inscrutable.Footnote 95 Taraporewala’s performance appears similar: had he delivered his remarks in English or Gujarati (the languages most associated with Bombay Parsis), he would have gravitated toward either the European or the Indian pole and thereby disrupted the balance. Esperanto allowed him to maintain, even as it allowed him to challenge, both extremes.

The passionate case that Taraporewala made for Esperanto is all the more remarkable for defying a by then perceptible erosion in the language’s popularity in India, where the promise of Esperanto that so many had confidently predicted was simply not coming to pass. The Theosophical Society’s enhanced commitment to the language notwithstanding, public advertisements for Esperanto materials had been on the decline since Pollen’s visit and had all but evaporated by 1911 or 1912.Footnote 96 The Athens conference would also prove at odds with larger political currents about to engulf Europe: indeed, not two years after these scholars locked horns on academic minutiae, they would find themselves divided by matters of significantly higher stakes.

V

The First World War, when it came, would put to the test the logic and relevance of almost all global organizations and ideas. Having already lost its footing, Esperanto – a movement with hope enshrined in its very name – seemed potentially out of place in a world now facing destruction on an unprecedented scale. Pollen, for one, was not deterred. Delivering an impassioned speech at an emergency meeting of the British Esperanto Association in September 1914, he attempted to turn the narrative of recent events on its head by insisting that the violence merely confirmed the inanity of the current global order. Had the warring parties known Esperanto, he explained, then they could have understood one another and prevented Europe from becoming ‘lashed into blood’.Footnote 97 But even amid the bleakness of war, he insisted that learning the universal language could facilitate British troops’ communication with their allies. French Marines, he claimed, had shown a penchant for the language, and Russia and Japan had respectively birthed the movement and taken to it with enthusiasm.

Though India does not appear in his remarks, his remarks did appear in India,Footnote 98 making their way into a Times of India piece when no major British newspaper bothered to publish them.Footnote 99 This speaks more to Pollen’s enduring celebrity in India than it does to any enduring commitment to Esperanto among Indians. In the wake of the war, we read – again in The Times of India – of Esperanto’s ‘untimely grave’, and in a 1922 review of a new Esperanto dictionary we find more bitingly still that: ‘It argues a courage, or a faith, greater than we believed to exist, to publish at the present time an English–Esperanto dictionary…That is all we can say. If there are any Esperantists left, they know where to turn for a dictionary.’Footnote 100 Even Taraporewala, who on the eve of the war had vociferously defended Esperanto against a European professor’s charge that it ‘was all folly and nonsense, and that Esperanto was artificial and ought to die away’,Footnote 101 had changed his tune. In a kind of post-mortem of the movement included in his Elements of the science of language, Taraporewala describes how Zamenhof had of necessity prohibited the abrogation of Esperanto’s core grammatical rules, since to do otherwise would be to welcome divisions that could threaten the movement’s raison d’être. At the same time, he writes, ‘this very prohibition was the “seed of death” for Esperanto. It, as it were, made the skeleton of the language rigid and fossilized; and if the skeleton does not grow and develop with the needs of the body, death must inevitably ensue.’Footnote 102

It did not help that the organization that had sustained Esperanto in India was itself neither growing nor developing. Another Times of India book review, this one discussing a new history of the Theosophical Society, draws a parallel between the Society and Esperanto, characterizing each as ‘an intellectual hybrid’ that was, owing to its artificiality, doomed to die.Footnote 103 Death also came in a more literal sense when Zamenhof himself passed away in 1917, robbing the movement of its figurehead. Pollen and Unwalla were now also showing their age: even before the war, in 1912, Pollen had noted that he was ‘the oldest Esperantist in the room’, and The British Esperantist affectionately remarked the same year that ‘Mr. Unwalla, though no longer young in body, is still young at heart, and cheerful and eager for our cause.’Footnote 104 Although new generations of Esperantists were arising in Europe and even galvanizing movements in places like China,Footnote 105 no obvious leader had emerged in India, where language activists increasingly offered nationalist solutions to what Esperantists insisted were international problems.

This injection of nationalism into language politics played out on a global scale: a consensus emerged across national borders that facilitating communication (a key goal of the Esperanto project) was best achieved by reforming national languages, especially through the simplification or substitution of scripts and the bridging of written standards and vernacular forms.Footnote 106 In India, this trend would bring the long-simmering Hindi–Urdu controversy to a boil, as Hindustani – the lingua franca much fetishized by Esperantists – increasingly bifurcated into the polarized registers of Hindi (written in Devanagari, associated with Hindus, and Sanskritic in vocabulary) and Urdu (written in Nastaliq, associated with Muslims, and Perso-Arabic in vocabulary).

As the ostensibly common language of Hindustani proved uncommonly divisive, Esperanto did manage to present itself, albeit briefly, as a dark horse candidate for the Indian lingua franca. This was effectively an audition for the role that Unwalla had briefly envisioned for it a decade earlier, but here, as before, Esperanto faced tough competition. Some maintained that the Sanskritized register of Hindustani offered the most politically salient representation of India’s identity, while others advocated for more neutral forms or even for a continued role for English (its colonial associations notwithstanding).Footnote 107 A conversation following a lecture at the East India Association in London in 1920 illustrates the multiplicity of positions among the Anglicized middle class. Most audience members agreed that the supremacy of English among the Indian elite was regrettable, prompting C. B. Rama Rao to propose a regulatory committee promoting Hindustani and Krishna Govinda Gupta to float a resolution proscribing the use of English among Indian officials.Footnote 108 Only two attendees, a certain Lady Katharine Stuart and a Professor Bickerton, advocated Esperanto, after which The Englishman tells us that the speaker showed impressive restraint by not ‘falling upon this suggestion and tearing it to bits’.

However risible their idea may have seemed to some, Lady Katharine and Professor Bickerton were not alone. In the autumn of 1921, the League of Nations weighed a resolution promoting the teaching of Esperanto that was signed by thirteen delegates,Footnote 109 including Khengarji III, the maharaja of Kutch, further attesting to the appeal of the language among Indian royalty (including, as we have seen, the former nawab of nearby Junagadh). Unfortunately for Khengarji, his enthusiasm was not shared by the Government of India; to the contrary, the Bombay Chamber of Commerce stated that it was – as paraphrased by The Times of India – ‘strongly of opinion [sic] that no steps should be taken by Government to teach Esperanto in schools in India until it was in common use in other parts of the world and, further, until the Indian budget showed a surplus which was not required for defence, sanitation and ordinary vernacular and English education’.Footnote 110 That surplus, the reader could reasonably conclude, was unlikely to appear soon, if ever.

VI

By contrasting ‘ordinary’ education, defence, and sanitation with Esperanto, the Bombay Chamber of Commerce located the latter firmly outside the bounds of the essential. It was a luxury and, as such, something for which interested individuals should not expect state support. Declaring Esperanto a frivolity was an affront to a movement that promised nothing less than global communication at a time of global possibility. But if the Chamber had uncharitably translated the ideals of the movement, it had accurately captured how many in India now saw the study of Esperanto as an elite pastime rather than a viable policy. The cause seemed nothing if not impractical, especially since those most invested in the movement could already claim some access to the international, and specifically the imperial, connections it dangled.Footnote 111

What now appeared as a fundamental contradiction in the Indian Esperanto movement had of course once been one of the main factors behind its appeal. Though there is little indication that Indians’ interest in the language was a mere hobby or their belief in its potential as an international language a mere flight of fancy, these convictions had stood alongside Esperanto’s perceived ability to designate for its speakers (or potential speakers) a place in an international social sphere in which they were already participants. Parsis, Theosophists, and even Pollen could all attest to this conundrum, since each was located personally, professionally, or even spiritually within the subcontinent while participating in networks that led to Europe and usually to Britain. But whether in Europe or the subcontinent, each also existed in a liminal state for which both the cause and the structure of Esperanto – European but global, familiar but foreign – proved resonant. English may have held the keys to the metropole, but it also threatened to turn the lock on Indian elements that many wished to retain and that Esperanto seemed to preserve. Esperantists’ various interpretations of the link between Esperanto and India illustrate this tension, as Pollen (a non-Indian) articulated the language’s essential Aryan-ness even as Indian elites embraced its near-Europeanness. Esperanto, then, offered a readymade illustration of the transregional entanglements in which groups like the Parsis and Theosophists were enmeshed, equipping them not so much with a community that could encompass the globe – as per their stated objectives – but with a means to mark their location within it.

But as non-cooperation reshaped Indians’ relations with the world and with one another after the First World War, the Esperanto movement struggled to keep pace. In this respect, interestingly, Esperanto’s fate in India would diverge from elsewhere in Asia. Not only would the movement come into its own in places like Indonesia during the interwar years,Footnote 112 but it would also see remarkable adoption where it had long enjoyed a foothold, notably in Japan, where a cause long associated (as in India) with the privileged elite was forced to accommodate a new generation of Esperantists keen to tie the language to socialism and other causes.Footnote 113 In China, many Esperantists’ passionate commitment to anarchism similarly gave the language a new and enduring relevance.Footnote 114 But in India, the Esperanto movement failed to engage with trends that might have sustained it – most critically ascendant Indian nationalism – and so saw its imperial and European links, once an advantage, emerge as a vulnerability. In 1919, the linguist Syamacharan Ganguli pulled no punches in exposing the Eurocentrism of the project and the language:

English grammar is simple enough, but it is less simple than that of Esperanto, which is however less simple in certain respects than that of the Asiatic languages, Persian, Hindustani, and Bengali, which Dr. Zamenhof apparently had no knowledge of. These three languages have no distinction of he, she and it, as Esperanto, like English, has. Nor has Bengali, like English and Esperanto, a distinction of number in verbs. Esperanto is thus not as simple in its grammatical structure as it is possible for a language to be.Footnote 115

But in a turn anticipated by Taraporewala’s experience in Athens, Esperanto maintained relevance for some Indians living outside the subcontinent and especially outside the empire where – as in China, Japan, and Indonesia under Dutch rule – the hegemonic language was not a major European language like English or French.Footnote 116 Most notable is the Tagore disciple-turned-Swedophile Lakshmiswar Sinha, who would become among the first Indians to produce a sizeable body of work in the language. Living in Sweden, Sinha was less concerned about promoting Esperanto among Indians than in using it to educate non-Indians about his homeland, producing texts on the life of the Maratha warrior-king Shivaji (d. 1680) and folklore from his native Bengal.Footnote 117 These works demand attention that exceeds the scope of the present study; what matters here is that they give the lie to an assertion found in Enciklopedio de Esperanto – a kind of Esperantist retrospective of the early movement published in 1933 – in which the entry’s author, the Russian Esperantist Ivan Ŝirjaev, equates the Indian movement with Pollen, during whose life, he writes, ‘[t]he movement grew ceaselessly…, but everything halted after his death in 1923’.Footnote 118 Ŝirjaev not only minimizes Sinha (whom he mentions peripherally) but also obscures figures like Unwalla, whose activities in India we have seen predate Pollen’s, and Taraporewala, who was among the first to represent the Indian face of the movement in Europe. We have seen, too, that far from ‘gr[owing] ceaselessly’ during Pollen’s life, the Indian Esperanto movement had in fact floundered for about a decade before his death.

Though it plays fast and loose with the facts, Ŝirjaev’s characterization nevertheless reinforces the widespread sense that Pollen embodied India’s encounter with Esperanto. I have to a cautious extent endorsed this view in this article, which has maintained that Pollen’s visit – though it was by no means synonymous with Esperanto in India – illustrates the near-European appeal of the language and exposes, albeit inadvertently, the key role of Indians within the movement. In a more tragic way, too, the circumstances of Pollen’s death evoke the fraying connection between India and Esperanto. Embodying the language to which he had remained steadfastly committed, Pollen went missing in June 1923, his ‘strange disappearance’ prompting a minor sensation in The Times of India, which joked, darkly, that he might have been murdered for speaking to a stranger in Esperanto.Footnote 119 A month later, his body was finally found ‘on the shore of Solway Firth’,Footnote 120 a hundred kilometres from where he had last been sighted sporting an Esperanto lapel pin on the Isle of Man.Footnote 121 Even in death, then, Pollen serves as an apt if macabre metonym for the Esperanto project in India: adrift between two shores, his body asserted belonging and sought recognition even as it was carried away, and lost, amid powerful, shifting currents.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Akshara Ravishankar and Ünver Rüstem for reading earlier drafts of this article and offering predictably astute and helpful suggestions. I also owe a great debt to the two anonymous reviewers, whose incisive remarks and expertise on the history of Esperanto have greatly enhanced my own analysis. I am particularly grateful to the second reviewer for encouraging me to consider the relationship between Esperanto and empire more closely. Rachel Leow has proved an exceptionally patient and observant editor, whether by catching an error or navigating the larger complexities of the publication process. I am grateful, too, to Linda Randall for her diligence and care in copy-editing. Remarks from Bipasha Bhattacharyya, whose work on the Esperanto movement in India came to my attention after the last substantial revision of this piece, prompted me to attend with particular care to my Esperanto translations and transliterations in the course of final corrections. One especially enjoyable aspect of this project was working with Sarah Almirall and William Tang, fourth- and fifth-generation descendants of John Pollen, whose careful safeguarding of family materials enabled me to add texture and depth to my discussion of their ancestor. For their reply to my initial inquiry and their willingness to entrust their precious family artefacts to my examination, I am immensely grateful.