Work in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) has evolved rapidly in recent years. It has become increasingly relevant as the social-political zeitgeist has highlighted disparities experienced by demographic groups (e.g., #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, and Love is Love). Organizations have spent billions of dollars on DEI interventions in the past decade. However, the recent politicization and subsequent polarization of racial, gender, and sexual identity issues has led to resistance and backlash toward DEI. Some societal tensions have also entered the workplace, affecting interpersonal relationships critical for organizational success (Devine & Ash, Reference Devine and Ash2022). With the embrace of DEI-related initiatives, practitioners and researchers are increasingly met with hostility and tension when addressing issues surrounding the intricacies of social group differences (Singal, Reference Singal2023).

Illustrating these tensions, at a recent inclusive leadership conference hosted by a large American university, participants consisting of high-level DEI and human resource officers, many of whom were affiliated with Fortune 500 companies, engaged in a discussion highlighting the concerning trend that terms such as psychological safety, discrimination, diversity, and inclusion have become “weaponized.” One DEI executive from a local company stated:

On the subject of [diversity training] we just launched a huge what we call “feel good leaders” program… and it got a huge positive response and people don’t even realize they are getting DEI training as part of it. We didn’t launch it as that although that’s kind of what it is…it’s just kind of in the packaging. We have gotten great feedback

Organizations often employ training to address DEI issues (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Spell, Perry and Jehn2016; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Corrington, Dinh, Hebl, King, Ng, Reyes, Salas and Traylor2019; Pendry et al., Reference Pendry, Driscoll and Field2007). However, as this New York Times headline, “What if diversity training is doing more harm than good?” illustrates, there is concern about the value of diversity training (Singal, Reference Singal2023). Whereas DEI training is intended to improve peer interactions and cultivate a universal sense of belonging, initiatives may not consistently deliver the anticipated effectiveness for organizations (Burnett & Aguinis, Reference Burnett and Aguinis2023). Scientists and practitioners have explained why some diversity training programs may not meet expectations. Diversity training may not succeed because it communicates to majority group participants that they are at least partially responsible for the plight of the minority (Dobbin & Kalev, Reference Dobbin and Kalev2016). Second, the content of diversity training often attempts to educate and change the way employees see social issues rather than targeting specific problems the organization would like to solve (Georgeac & Rattan, Reference Georgeac and Rattan2023). Third, diversity training is often a reaction to a critical incident, resulting in an organizational mandate for all employees to attend training (Devine & Ash, Reference Devine and Ash2022). Thus, it is often expressed or viewed as remedial and punishment. This has been exemplified in several diversity-related training programs the authors have attended, which were often received negatively by attendees who felt obligated to participate in sessions they believed were intended to address the misconduct of a small group of individuals. Diversity training may tokenize some group members (e.g., women and LGBTQIA+; Rawski & Conroy, Reference Rawski and Conroy2020). These reasons may suggest that diversity training may not always be as effective as researchers and practitioners hope, or worse, may stir backlash. However, diversity training can be effective when designed and delivered appropriately (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Spell, Perry and Jehn2016). Cheng et al., (Reference Cheng, Corrington, Dinh, Hebl, King, Ng, Reyes, Salas and Traylor2019, p. 2) aptly observed, “The question must shift from whether or not diversity ‘works’ to more careful considerations of for whom, how, when, where, and in what way (or to what end) does each training work?”

We suggest that the who, how, when, where, and in what way questions can be partially addressed by considering how the training is packaged or framed. The framing effect is a cognitive bias in which the presentation of information influences how people react. How the content is portrayed can impact how the training is perceived. Training described as broadly featuring such topics as race, gender, lifestyle, and personality differences in the workplace is more positively perceived than training described as narrowly featuring only topics relevant to race (Holladay et al., Reference Holladay, Knight, Paige and Quiñones2003). We believe that a potentially highly influential and overlooked type of framing considers the training participant’s moral foundation and values. We contend that individuals’ moral foundations, which shape their perceptions of right and wrong, influence how they perceive and respond to different components of diversity training. We address how scholars and practitioners can leverage morality-based decision processes to enhance diversity training effectiveness by considering how training programs, from design to implementation, can be appropriately framed to appeal to participants across the moral spectrum. In this article, we review the moral foundation’s framework, discuss why it is important to consider moral framing when developing and delivering diversity training programs and provide recommendations for managers.

A brief overview of the moral foundations and framing

Why do some participants leave diversity workshops feeling compassion and gratitude, but others leave the same workshop feeling disgruntled or angry? This may partly be due to the moral lens through which they perceive the training experience. Moral psychology and social justice researchers have agreed that morality concerns harm, rights, and justice (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012). Morals are developed over an individual’s lifespan. They can be seen as an accumulation of social learning and self-learning processes that are judged and affirmed by the self and others through social interactions and experiences (Haidt, Reference Haidt2007). Moreover, morals are social conventions that provide individuals with a standardized framework for evaluating persons, situations, and actions made by the self and others (Bandura, Reference Bandura, Kurtines and Gewirtz1991; Sawyerr et al., Reference Sawyerr, Strauss and Yan2005).

After reviewing the anthropological literature, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009) presented theoretical and empirical reasons for believing that five psychological systems provide the foundations for the world’s many moral frameworks. They explained that these psychological systems provide the foundations for individuals when they consider what is right and wrong. Individuals endorse varying degrees of the five moral foundations that influence how they perceive and interpret events around them. They labeled these the five foundations of morality. These foundations represent both values and virtues. Individuals experience strong positive emotions when circumstances are consistent with their strongly held morals and conversely experience negative emotions when situations are inconsistent with these morals (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009).

Graham and colleagues” (2009) moral foundations theory describes five foundational pillars that serve as the basis for moral beliefs and evaluations across cultures:

-

1. Care: Individuals who value care are sensitive to avoiding harm toward others. They support actions that relieve or reduce harm and promote the well-being of others, focusing on the welfare of individuals.

-

2. Fairness: Individuals who value fairness are sensitive to issues of equality, equity, and justice, including reciprocity and social justice.

-

3. Loyalty: Individuals who value loyalty and their in-group focus on cooperation, trust, cohesion, and recognition among members within an in-group. They emphasize that the needs of the group are above the needs of the individual (i.e., group over individual rights). They also tend to have distrust of and behave cautiously toward members of perceived out-groups.

-

4. Authority: Individuals who value authority and respect focus on the virtues of both subordinates (e.g., respect for authority and obedience) and authorities (e.g., protection and leadership). They value laws, rules, and order. Dissent against authority is seen as immoral.

-

5. Purity: Purity is described by benevolence—acting without any trace of evil or selfish motives. Intentions are pure when free of self-interest, egoism, cruelty, spite, and dishonesty. The moral purity belief is that individuals are born with an inherent goodness or purity, which can be corrupted or lost over time through negative experiences or exposure to negative influences (including harassment, discrimination, or unfairness, as examples).

Individuals use moral lenses to judge people and events (Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2019; Haidt, Reference Haidt, Davidson, Scherer and Goldsmith2003). Individuals evaluate diversity training programs depending on the moral foundation for the training. For example, diversity training that narrowly focuses on racial disparities may be viewed from a compassionate lens when a person holds strong fairness morals. In contrast, diversity training programs framed toward group disparities may elicit discontent from participants with strong loyalty and in-group beliefs, promoting the exclusion of out-group members. They may see attention toward out-group members as exclusionary, if not threatening to their and other groups. Additionally, some employees who strongly endorse in-group morals may be disappointed by diversity training framed as necessary to level the playing field. This may be seen as a punishment toward their in-group.

Differences in morality and the social divide

Whereas research on the moral framing of DEI training may be limited or nonexistent, scholars have studied the importance of the five moral foundations and framing within the political psychology literature (Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2013; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Koleva et al., Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012). Scholars have theorized that liberals and conservatives hold dissimilar priorities among the five moral foundations. Liberals rely more on the care and fairness foundations, whereas conservatives rely on the five foundations, including loyalty, authority, and purity, equally (Haidt, Reference Haidt2007). This is not to say that liberal individuals do not value the other three foundations; rather, care and fairness are most important to them in evaluating moral relevance (Haidt, Reference Haidt2008).

Although more liberal-leaning and conservative-leaning individuals may often disagree on what is and is not morally acceptable, evidence suggests this is partly due to how messages are framed (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). Theorizing on moral framing suggests that this occurs because messaging is more likely to resonate with individuals when aligned with a person’s moral convictions (Aquino & Reed, Reference Aquino and Reed2002). When messaging appeals to an individual’s moral convictions, they are more likely to respond positively and evaluate the messages favorably, even if they might typically oppose this position (Kovacheff et al., Reference Kovacheff, Schwartz, Inbar and Feinberg2018). Accordingly, messaging that is morally reframed to align with an individual’s moral convictions may be more effective in generating support and positive attitudes.

Immigration and environmental policies emphasize the care and fairness foundations and garner support from liberals, who have strong care and fairness moral convictions (Bloemraad et al., Reference Bloemraad, Silva and Voss2016; Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2013). In contrast, these immigration and environmental policies couched in care and fairness foundations were repudiated by conservatives who strongly value loyalty, authority, and purity. However, when the policy is reframed within not only the care and fairness foundation but also in the additional foundations that are valued by conservatives (e.g., loyalty, authority, and purity), they are more likely to endorse these policies (Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2013). Individuals are likely to evaluate diversity training initiatives more positively or negatively based on how well the training content and framing align with their moral reasoning. Training efforts framed to resonate primarily among the moral frame of members from one subgroup (e.g., conservatives or liberals) rather than the organization’s population are likely to experience limited success and may even exacerbate intergroup conflict.

Framing diversity training initiatives

To better understand the utility of framing, we emphasize research has effectively demonstrated that emphasizing or downplaying aspects of a message can alter individuals’ attitudes and beliefs about an issue. For example, when affirmative action is framed as enhancing diversity, it is more favorably received than when it is framed as compensating for past injustices (Kravitz et al., Reference Kravitz, Klineberg, Avery, Nguyen, Lund and Fu2000). Consider a narrative for a diversity training program that suggests that a racial minority group (e.g., Black people) has been systematically wronged by majority group members (e.g., White people) in society. Whereas this may appeal to some training attendees, particularly those with strong fairness moral convictions, this may alienate those who hold strong loyalty and authority moral convictions. Moreover, members of other nonmajority groups (e.g., women, LGBTQIA+, disabled individuals, and other groups) may feel further devalued by the organization and the training initiative, as it fails to address their experiences as nonmajority members. In addition, the members of the nonmajority groups that the training purportedly attempts to help may perceive the training as unwanted attention to their disadvantaged status (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Corrington, Dinh, Hebl, King, Ng, Reyes, Salas and Traylor2019). Thus, whereas designer intentions for this type of training are admirable, they may not move the needle in a positive direction. This presents a notable challenge, especially for training attendees who stand to gain much from the training but might resist due to messaging that conflicts with their moral convictions. Researchers and practitioners can address these challenges and enhance the overall efficacy of diversity training programs by assessing how the training is morally framed and its alignment with the various audiences within an organization.

Moral reframing is not new and has been leveraged to increase support for political messaging in several scientific reports. Messaging aligned with individual values influences attitudes toward political messaging (e.g., environmental conservation; Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2013). Conservatives displayed more pro-environmental attitudes when the message was designed in line with a purity moral foundation (emphasizing impurity of pollution and contamination) than when it was couched in terms of care (humans need to protect the environment for future generations). Liberals were equally positive with both moral frames. These findings suggest that moral reframing may help the messaging appeal to individuals with different emphases regarding their moral perspectives. In another study examining the moral reframing of U.S. immigration policy (Voelkel et al., Reference Voelkel, Malik, Redekopp and Willer2022), researchers found that framing immigration policy arguments using language grounded in the loyalty foundation resonated with participants and increased support for legal immigration. Together, these studies suggest that moral reframing can have a significant impact when communicating with audiences who may not share the same moral convictions.

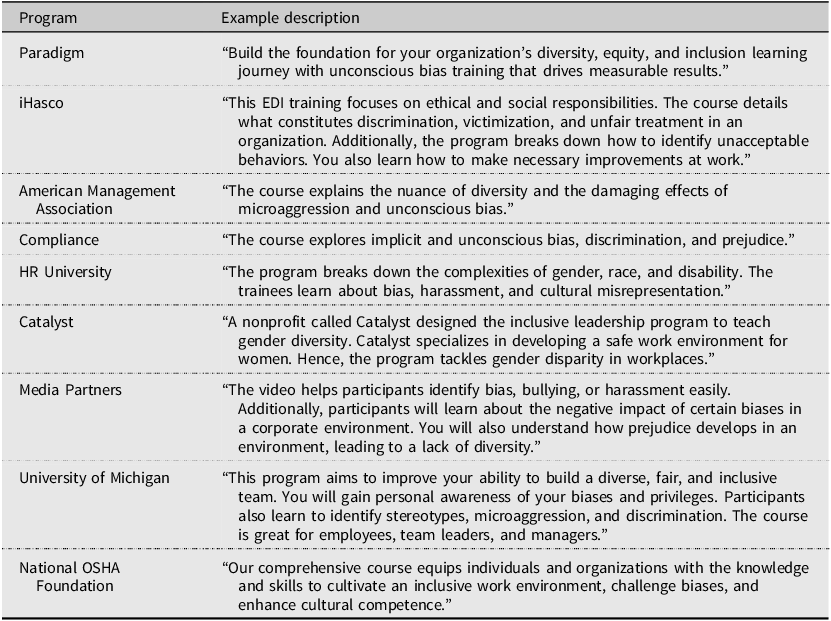

We contend that diversity training initiatives have a similar opportunity for moral framing that may enhance effectiveness and training buy-in. Those who endorse and design workplace diversity training programs often hold strong care and fairness morals, and their framing of the initiative toward care and fairness may positively impact those who also strongly hold these values. We conducted a straightforward online search for some of the most popular diversity training programs, categorizing them based on the moral foundations they represented. Most of these programs were framed around the principles of fairness and care/harm. We provide examples of these training program descriptions in Table 1.

Table 1. Example Diversity Training Program Descriptions

Onyeador et al. (Reference Onyeador, Mobasseri, McKinney and Martin2024) offered support for moral framing grounded in the care and fairness foundations. They used a qualitative approach to explore the advertised content of diversity training programs by analyzing data from 163 public descriptions of training programs in a vendor database maintained by the Society for Human Resource Management. They found that many programs focused on identifying and counteracting individuals” implicit biases. Another identified common theme was fostering intergroup relations, emphasizing workplace civility and inclusivity. These themes align with the moral foundations of care and fairness, centering on reducing unfair practices, caring for others from diverse backgrounds, minimizing harm, and understanding systemic racism.

Framing diversity training programs around these moral foundations may resonate with individuals who share these moral convictions. This narrow scope may not appeal to broader audiences with different moral orientations (Feinberg & Willer, Reference Feinberg and Willer2019; Holladay et al., Reference Holladay, Knight, Paige and Quiñones2003). Whereas many participants are likely to adhere to care and fairness virtues, which are important levers in attitude and behavior formation, individuals vary regarding loyalty, authority, and purity foundations. As diversity and inclusion issues are typically presented through the lenses of fairness and care values, these training initiatives” moral messaging and framing are likely to readily align and resonate with those with strong care and fairness moral foundations. This may create dissonance for those who also value loyalty, authority, and/or purity to an equal or higher degree if it is counter to their moral foundations. This can influence thoughts, affect, and attitudes toward the training—to the detriment of training effectiveness.

How does morality shape evaluations of diversity training programs?

We have argued that differences in moral foundations can alter how a training attendee may perceive diversity training programs. This has primarily been based on assumptions that findings in the political psychology literature on moral messaging would also apply to workplace diversity programs. Hence, we examined whether employee differences in moral foundations influenced their evaluations of diversity workshops framed or packaged differently. Using email vignettes inviting them to participate in a workshop, we assessed whether participants supported or opposed a training program and whether they would likely attend when the training was framed using different moral lenses. We present the methods in the technical appendix and provide the data, code, and analyses in an Open Science Framework (OSF) repository, which can be found using the following link: https://osf.io/eay8u/?view_only=04eb0aadd12c4661ac4833101cd1841a.

Descriptive statistics showed that, overall, employees would be generally supportive and willing to attend these workshops regardless of moral frame (percentages all over 50% endorsing support and attendance and means greater than 3 on a 5-point scale). At first glance, this might imply that the framing of diversity training programs has little effect on how training is perceived, or perhaps a care or fairness frame may work for everyone. These descriptives are informative but overlook the potential impact of individual differences in moral foundations on respondent evaluations. To further explore this, we explored the relationships between the five moral foundations and ratings of support and the likelihood of attending each training program.

As shown in Table A1 of the technical appendix, respondent support for the training and the likelihood of their attendance may depend on their moral framework (see also Technical Appendix Figures A2 and A3). Employees with strong care and fairness moral foundations tended to be more supportive of the training programs and were likelier to attend them, regardless of the moral framing used. Higher authority and purity respondents were also less supportive and less likely to attend training programs framed within care and fairness morals.

A different story emerges for the loyalty-, authority-, and purity-framed emails. Specifically, the five moral foundations were related to the likelihood of supporting and attending training workshops framed in messaging around loyalty, authority, and purity. For example, when framed around loyalty (e.g., “In this workshop, we will discuss how to build a stronger community, how to create solidarity in the workplace, ways to improve loyalty to the company and to each other, and strategies for working in effective teams”), those with care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity frames indicated a greater likelihood to attend.

Alternatively, when framed in terms of care or fairness, only those with care and fairness frames were supportive or likely to attend. These findings are consistent with the perspective that employee morals may be linked to the moral frame used within diversity training programs.

We also asked respondents to rate whether they supported and would be likely to attend a training program that explicitly mentions diversity, equity, and inclusion. We included this framing for two reasons. First, scholars have often lamented the use of broad claims made by diversity initiatives that do not necessarily link to outcomes purported, which may have increased skepticism toward diversity programs (Onyeador et al., Reference Onyeador, Mobasseri, McKinney and Martin2024). Second, diversity training has recently attracted considerable attention from scholars and practitioners, as the politicization of DEI initiatives may have generated backlash and opposition to diversity programs (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Corrington, Dinh, Hebl, King, Ng, Reyes, Salas and Traylor2019).

Our findings reveal a pattern similar to both the care and fairness framings. Individuals who highly value care and fairness were more likely to support and attend the DEI-framed workshop. In contrast, those who place higher importance on authority and purity were more likely to oppose and avoid the DEI workshop.

Practical applications of moral reframing in diversity training

Drawing on evidence from the diversity training and moral psychology literatures and our findings, it would be useful for scientists and practitioners to consider moral framing when developing diversity-related training initiatives. How training is framed or packaged can impact the support given to it and the individual’s likelihood of attending.

We advocate messaging and framing training initiatives in terms of all five moral frames, not only the traditional moral dimensions of care and fairness. Accordingly, we discuss each moral foundation within the context of diversity training and outline how researchers and practitioners can structure training initiatives to encompass a wide range of moral perspectives.

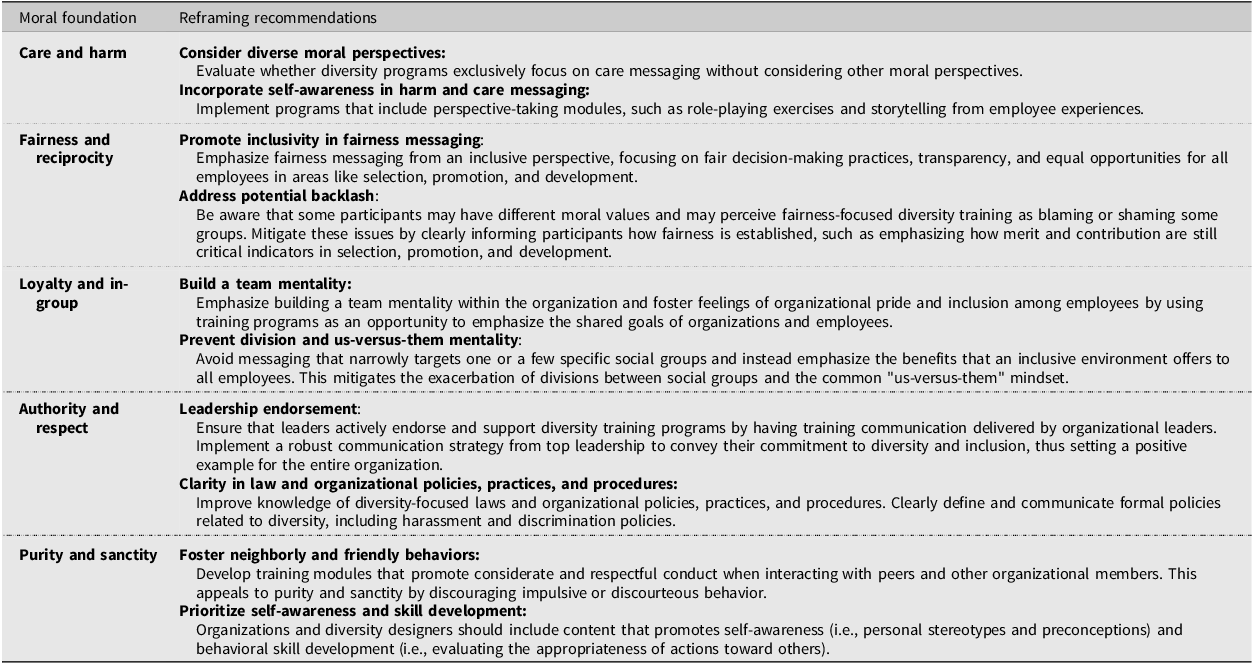

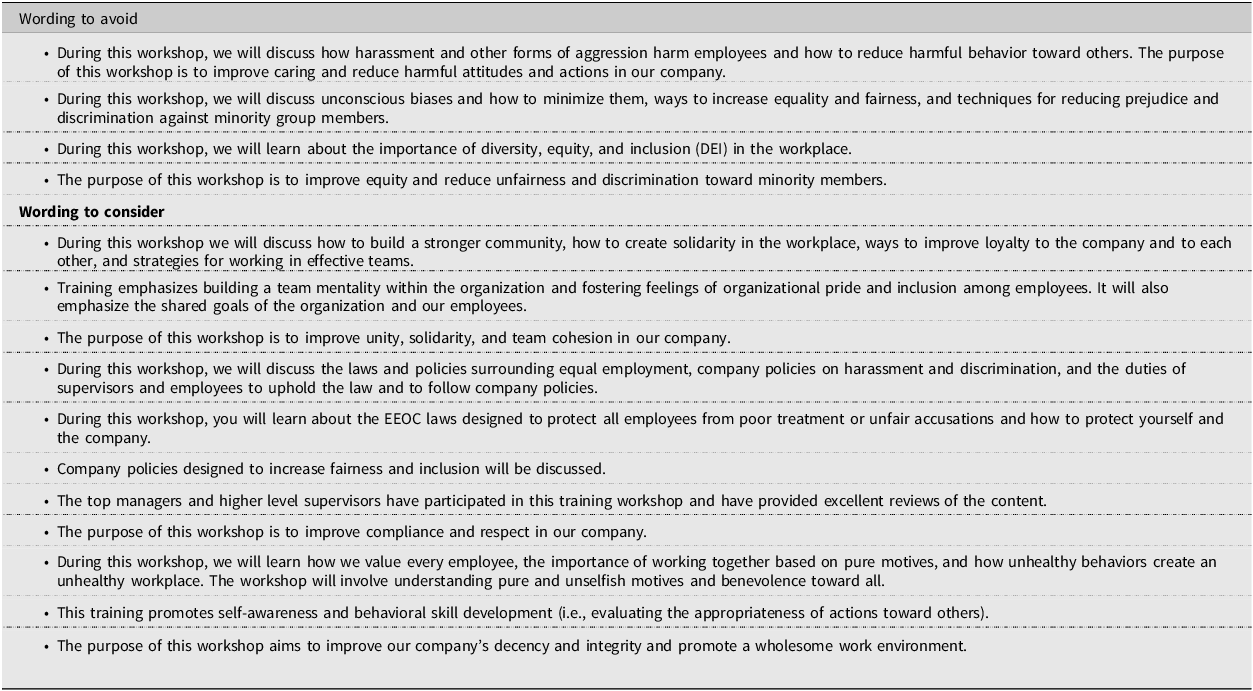

We present a summary in Table 2. Additionally, in Table 3, we present examples of how to effectively frame and package diversity training programs to improve the overall messaging of training efforts and maximize buy-in.

Table 2. Reframing Diversity Training Within a Moral Foundations Framework

Table 3. Ways to Effectively Frame/Package Diversity Training Initiatives to Maximize Buy-In

Frame 1: care and mitigating harm

Framing diversity training within the care and harm mitigation moral foundation highlights the need to reduce harm toward minority group members and provide care through organizational support mechanisms (e.g., employee resource groups). Many diversity training offerings are embedded within the care moral foundation. As is common in diversity training, harm-reducing messaging may include a discussion of how all individuals carry implicit and explicit biases that affect decision-making processes (i.e., selection, promotion, and delegation of responsibilities), which may harm employees from different social groups. Accordingly, care messaging attempts to legitimize the experiences of one group by encouraging others to understand the subjective experience on a personal level.

Whereas care-focused diversity training programs positively affect participant and organizational outcomes, they may not resonate with the moral values of participants who hold different beliefs, diminishing their effectiveness. Therefore, we recommend that managers and training designers consider all moral perspectives when developing and implementing diversity training programs rather than relying on care or harm reduction narratives.

Frame 2: fairness and reciprocity

Alongside messaging around care and harm reduction, diversity training frequently incorporates the fairness and reciprocity moral foundation that emphasizes equitable treatment, the prevention of discrimination, fair workload distribution, and accountability. This may partly be due to design decisions that lean heavily on care and fairness morals. Fairness messaging in diversity training often emphasizes the disparities and mistreatment felt by minority groups in comparison to majority group members (e.g., white men; Bloemraad et al., Reference Bloemraad, Silva and Voss2016). For participants with strong fairness morals, this type of diversity training can evoke sympathy or compassion for minority group members and shame or guilt for belonging to a majority group. Conversely, our results illustrate that those prioritizing loyalty, authority, purity values, and fairness may oppose such programs, perceiving them as blaming or shaming majority groups for organizational inequities (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Corrington, Dinh, Hebl, King, Ng, Reyes, Salas and Traylor2019). This can result in the backlash mentioned by some participants when describing diversity training. As such, when discussing fairness, designers might emphasize reciprocity or “what’s in it for me” that is achieved through fairness instead of merely leveling the playing field.

Frame 3: loyalty and in-group

As previously discussed, the loyalty and in-group moral foundation refers to the value placed on in-group members and those who sacrifice for the in-group while disliking or harboring negative feelings toward those who betray or harm the in-group (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011). At a superficial level, this may appear at odds with diversity training initiatives, which often advocate that out-groups should be celebrated and included—and that resources should be shared with others outside of the in-group. The training initiative may succeed more by reframing diversity and inclusion and appealing to loyalty. Research indicates that training initiatives closely aligned with reinforcing a superordinate organizational identity (i.e., the organization or work unit) can reduce in-group distinctions and foster a sense of belonging by portraying employees as members of the organizational in-group. This aligns well with Shore et al.’s (Reference Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Ehrhart and Singh2011) inclusion framework that highlights the importance of instilling a sense of belonging and feelings of being an insider of the organization.

We recommend that loyalty framing be leveraged when designing diversity training programs to foster a collective organizational identity and increase training buy-in. Appealing to loyalty and in-group moral foundation requires reframing around common conceptions of what constitutes in-group members. This involves bringing to the forefront a higher level of organizational identity and membership, as opposed to organizational silos, gender groups, racial groups, and so forth. Loyalty-focused messaging emphasizes the organizational community, building a team mentality, and fostering feelings of organizational pride and belonging.

When higher order organizational identity is achieved, we can expect employees to be more professional and forge stronger interpersonal relationships because the in-group now includes all organization members. Cultivating a collective organizational identity prevents a common drawback observed in diversity training initiatives—the exacerbation of divisions between social groups and the common us-versus-them mindset often found in siloed organizations (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Spell, Perry and Jehn2016).

Frame 4: authority and respect

Those who value authority are concerned with social hierarchies, obedience to rules and regulations prescribed by legitimate authority (e.g., organizational policies, leaders, supervisors), and respect toward traditions and norms (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011). Reframing diversity training initiatives in terms of authority involves emphasizing leader-supported organizational rules and norms. Training initiatives are more successful when leaders support and behave consistently with the training materials (Smith-Jentsch et al., Reference Smith-Jentsch, Salas and Brannick2001). Employees who endorse authority morals may support diversity training when they perceive their supervisor and organizational leadership authentically support the training program. When employees perceive that leaders do not support or value diversity or that the organization is engaging in diversity training to maintain a positive public image, this may undermine the training program and create resentment or backlash. To develop an effective diversity training program, it is imperative to involve leadership in its development and to ensure they actively endorse the program through effective communication (e.g., implementing a communication strategy from the top) and serving as role models (e.g., setting a positive example).

Reframing diversity training initiatives within the framework of the authority moral foundation may also include improving knowledge of diversity-focused laws and organizational policies. This may involve communicating formal policies related to diversity (e.g., harassment and discrimination) that are clearly defined, easily understood, and regularly disseminated and providing an explanation of the procedural steps that occur in the event of a report or violation (Becton et al., Reference Becton, Gilstrap and Forsyth2017). For example, emphasizing Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) laws and their protections could be helpful. The laws enforced by the EEOC prohibit workplace harassment because of race, color, national origin, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), religion, disability, age (age 40 or older), or genetic information. The laws enforced by the EEOC also protect individuals from being harassed or punished at work and from retaliation if a complaint is made.

Moreover, because employees who value authority and respect adhere to traditions and consistency, it might be unwise for organizations to consider one-off diversity training sufficient for sustained change. Whereas a single diversity training session may positively impact reactions and produce changes to immediate attitudes, follow-up training and interactions are instrumental to increasing the sustainability of favorable outcomes (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Spell, Perry and Jehn2016). To further build organizational norms that foster diversity, training programs should be consistently and regularly provided to establish a lasting “tradition” of diversity and togetherness/cohesion.

Frame 5: purity and sanctity

Participants of diversity training workshops may also hold strong purity moral values that conflict with an emphasis on destructive behaviors or harm. Instead, those with this moral frame would emphasize doing good, being kind, and being honest. Reframing training initiatives from the perspective of purity is a challenge. If diversity training includes components such as asking participants to recognize their biases and stereotypes, it may be seen as bringing up negative experiences and negative behavior.

Alternatively, training could be framed as promoting honesty, goodness, and selflessness. Because those endorsing a purity frame aligned with those endorsing authority and loyalty, these frames could also appeal to those endorsing purity. Training developers can reframe diversity training within the purity moral foundation in several ways. First, training design might include awareness and skill development in monitoring impulsive or self-interested behavior. Second, organizations and trainers could develop participants’ abilities to consider the perspectives and experiences of others by fostering perspective taking and empathy. Third, appealing to kindness and goodness motives, such as ways to behave in considerate and respectful ways, would be valuable.

Research implications of moral reframing in diversity training

We have suggested that DEI training packaging matters. Empirical work examining various combinations of framing the moral foundations would be useful in identifying optimal approaches across individuals, work groups, organizations, and nations. For example, individuals differ in the extent to which they are willing to present arguments framed as inconsistent with their prioritized moral foundations (Isiminger & Giner-Sorolla, Reference Isiminger and Giner-Sorolla2024). Work is needed to inform theory and identify mechanisms that affect trainees and trainers.

Empirical work may discover that different approaches are needed in different contexts. For example, multinational organizations may need to employ country-relevant approaches to frame the training.

The success of diversity training is often limited when trainees perceive it as communicating that they are at least partially responsible for the plight of others (Dobbin & Kalev, Reference Dobbin and Kalev2016). As moral reframing minimizes angst against individuals prioritizing different values (Doherty & Kiley, Reference Doherty and Kiley2016), research might identify means for minimizing the reactions reflecting what some participants identify as a “blame game.”

Devine and Ash (Reference Devine and Ash2022) offered multiple opportunities for empirical research. We emphasize three of their suggestions. They called for efforts to utilize behavioral and systems-level outcomes to assess training effectiveness. As diversity training often stems from a critical incident (Devine & Ash, Reference Devine and Ash2022), morally framed DEI training might be more effective than traditional DEI training programs in yielding differences in post-training critical incidents—perhaps less if trainees improve their behavior or more if trainees become more sensitive to dysfunctional behavior. They also advocated including trainees who are socially connected within an organization as opposed to trainees who were mandated or volunteered to attend. Framing might be less effective among workers who know one another. Studies could lead us to understand how framing, group membership, and social identity work together to influence responses to DEI training. They also encouraged pairing cultural competence training with DEI training. Moral framing is likely to extend the impact of cultural competence training.

Conclusion

Leveraging moral reframing in training programs creates the opportunity to appeal to participants of various social identity groups. Whereas diversity training content has often focused narrowly on racial or gender differences, moral reframing presents an opportunity to enhance inclusiveness and belonging by valuing more, if not most, participants and their identities. For minority group members, this may also reduce feelings that the initiative is superficial or just for show. From an organizational standpoint, this is critical in developing and fostering interpersonal relationships, communication networks, and the many ideas available in the workforce. Moreover, it contributes to the sense of a superordinate shared identity, whereas valuing and respecting the multitude of social identities present in a diverse workforce.

Reframing diversity training within multiple moral frameworks may be an effective way to resonate with a broad audience and increase the effectiveness of diversity training programs. Well-intentioned training developers might be more likely to view the world through a care or fairness moral lens and develop training programs consistent with this moral perspective and packaged as such. This approach may not resonate with a portion of the population that brings diverse backgrounds and moral frameworks to the workplace, namely those who strongly endorse loyalty, authority, and purity. Interestingly, those with a care or fairness frame are not turned off by the authority, loyalty, or purity frames, further suggesting the value of diversity training that is packaged and delivered utilizing multiple moral frames. Hence, we recommend that organizations and developers of diversity curricula design diversity training and market it considering the five moral frames.

Acknowledgements

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose. Parts of this manuscript were previously presented at the 37th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Seattle, Washington, April 2022. The study presented in this manuscript was supported by research funding from the University of Houston, Division of Research. We would like to thank the Division of Research for their support in this study.

Appendix

Methods

Participants

We conducted a short supplementary study to further elaborate on the phenomena discussed. A total of 300 participants were recruited through the online platform Prolific. Participants were required to work at least part time (20 hours per week), be 18 years or older, and be fluent in English to ensure comprehension of study vignettes and questions. Participants were only included if they previously completed surveys via Prolific and were not flagged by the platform. One participant was excluded for failing attention check items, resulting in a final sample of 299. The gender breakdown indicated that 50.8% of participants identified as male, 48.8% as female, and 0.3% selected other. The racial composition consisted of 76.9% participants identified as White, 8.4% as Asian, 7.4% as Black or African American, 5.7% as Hispanic/Latino, 1.0% as Other, and 0.3% as American Indian or Alaskan Native. Regarding education, 48.2% of participants had a 4-year degree, 16.4% held a professional degree, 13.7% had some college, 10.0% were high school graduates, 9.4% had a 2-year degree, and 2.0% held a doctorate, with 0.3% missing responses.

Procedures

Following consent procedures, participants were told they would be reading emails inviting them to attend a workshop in their organization. They were asked to read each email carefully and respond to each question as honestly as possible. Next, participants were shown six emails, five for each moral foundation (care, fairness, authority, loyalty, and purity) and one that stated the training was for a general diversity, equity, and inclusion workshop. The DEI frame was included to assess how participants perceived DEI training when explicitly described as a DEI program. This enabled us to understand the valence and motivation elicited by morally framed emails compared to a standard DEI frame (Colquitt et al., Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000). The presentation order for the six email vignettes was randomly ordered to mitigate ordering effects. After each email, participants were asked to rate whether they would support the offered workshop and the likelihood of attending it. After providing ratings for each email vignette, participants were asked to complete a survey that measured the five moral foundations and demographic characteristics. We provide the email vignettes in Technical Appendix A.

Measures

Participants rated email vignettes using two items developed for this study. Support was measured with, “Would you support or oppose this type of training being offered by your company?” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly oppose to 5 = strongly favor. Participants were also asked about their likelihood of attending a workshop with, “How likely would you be to attend this training if it was offered by your company?” with a scale ranging from 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely. To measure individual differences in the five moral foundations, we used the moral foundations questionnaire developed by Haidt et al., (2022). Example items for the harm/care foundation include, “Caring for people who have suffered is an important virtue” and “Everyone should try to comfort people who are going through something hard.” Example items for the fairness foundation include, “It makes me happy when people are recognized on their merits,” and “The effort a worker puts into a job ought to be reflected in the size of a raise they receive.” Example items for the authority foundation include, “I think it is important for societies to cherish their traditional values,” and “I believe that one of the most important values to teach children is to have respect for authority.” Example items for the loyalty foundation include, “It upsets me when people have no loyalty to their country,” and “I think children should be taught to be loyal to their country.” Example items for the purity foundation include, “It upsets me when people use foul language like it is nothing,” and “I think the human body should be treated like a temple, housing something sacred within.”

Analyses

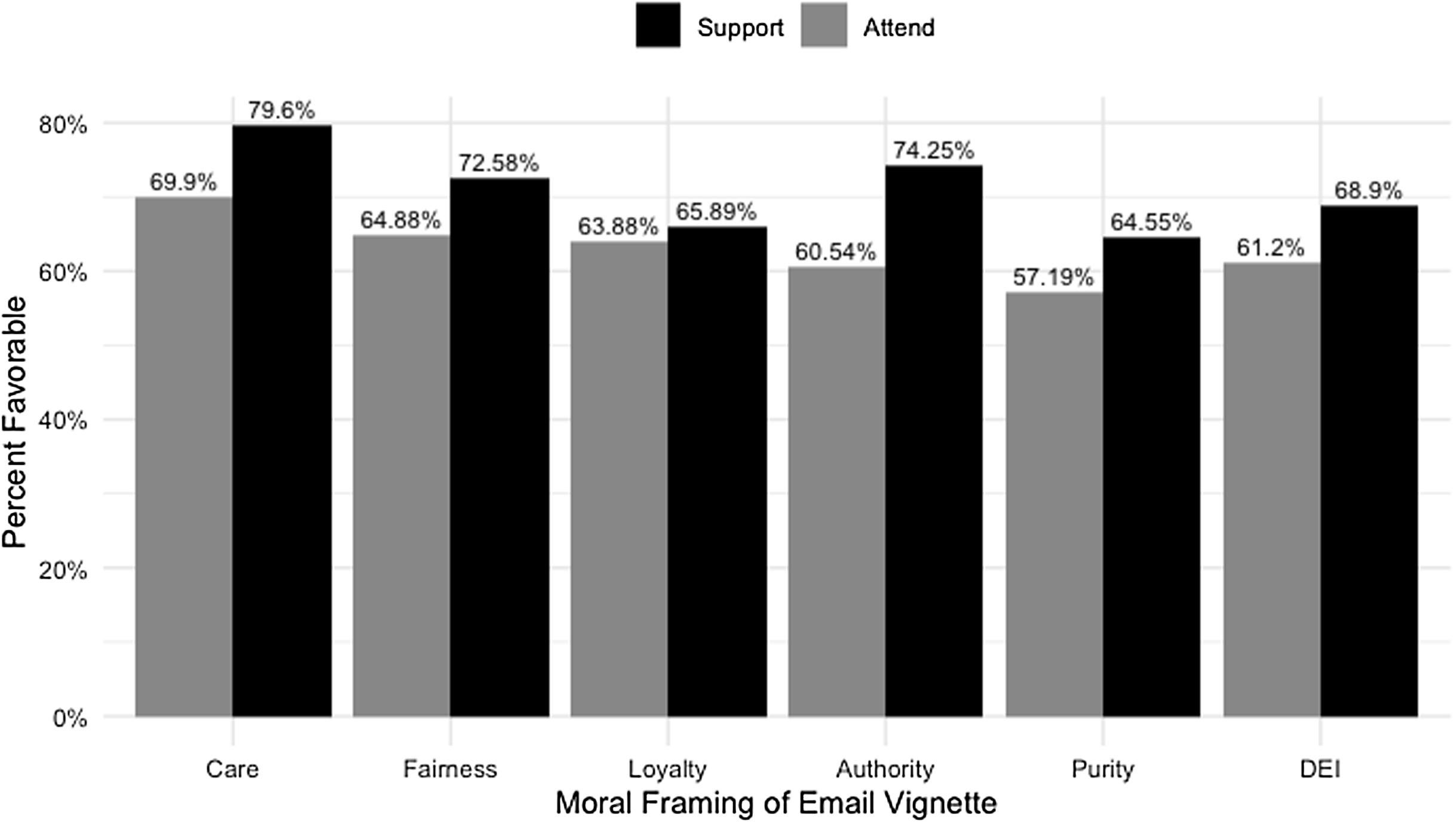

The analyses supplement the arguments that individuals with different moral frameworks evaluate diversity training based on the moral framing used. To this end, we provide descriptive statistics and correlations to illustrate how moral framing can influence support and intentions to attend a diversity workshop. Additionally, for illustrative purposes, we also offer a table that provides the percentage of the participants who were likely to support or attend the workshop as indicated by a rating of 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale (Technical Figure A1). Results are presented in Technical Appendix Table A1.

Results

Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and internal consistency (alpha) are presented in Technical Appendix Table A1. As shown in Technical Appendix Table A1, participants rated the care-framed email as the most positive for both support (M = 4.08, SD = 1.03) and the likelihood of attendance (M = 3.76, SD = 1.29). Workshops framed using purity language were rated as the lowest in support (M = 3.75, SD = 1.14) or attendance (M = 3.46, SD = 1.40). Fairness-, loyalty-, and authority-framed workshops were rated between care and purity (see Technical Appendix Table A1). Interestingly, emails that framed workshops explicitly using DEI language also had low support (M = 3.81, SD = 1.27) and likelihood of attendance (M = 3.50, SD = 1.50), similar to those of purity. We also examined these differences by conducting a repeated measure ANOVA using a linear mixed-effects model for repeated measures to account for the nesting of ratings within the individual. Omnibus tests indicate significant differences in support (F(5, 1490) = 7.78, p < .001, ηρ 2 = .03) and the likelihood of attendance (F(5, 1490 = 4.64, p < .001, ηρ 2 = .02). Post hoc tests using Bonferroni corrections further indicate significant differences in support ratings between care framing and purity (p < .001), loyalty (p < .001), and DEI (p < .01), as well as purity and authority (p < .01). Postdoc tests for differences in the likelihood of attendance ratings showed care framing significantly differed from purity (p < .001), authority (p < .05), and DEI framing (p < .01).

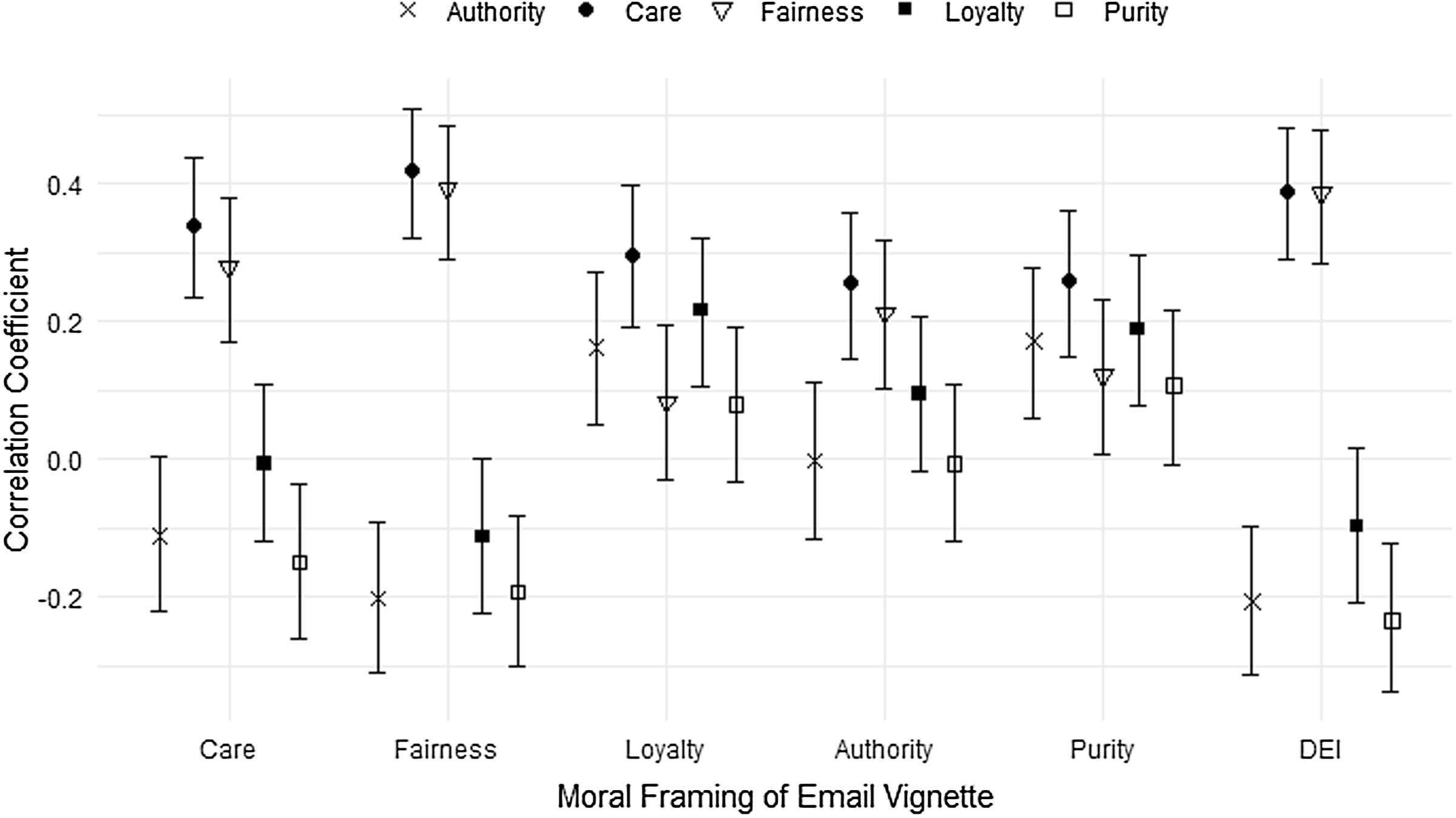

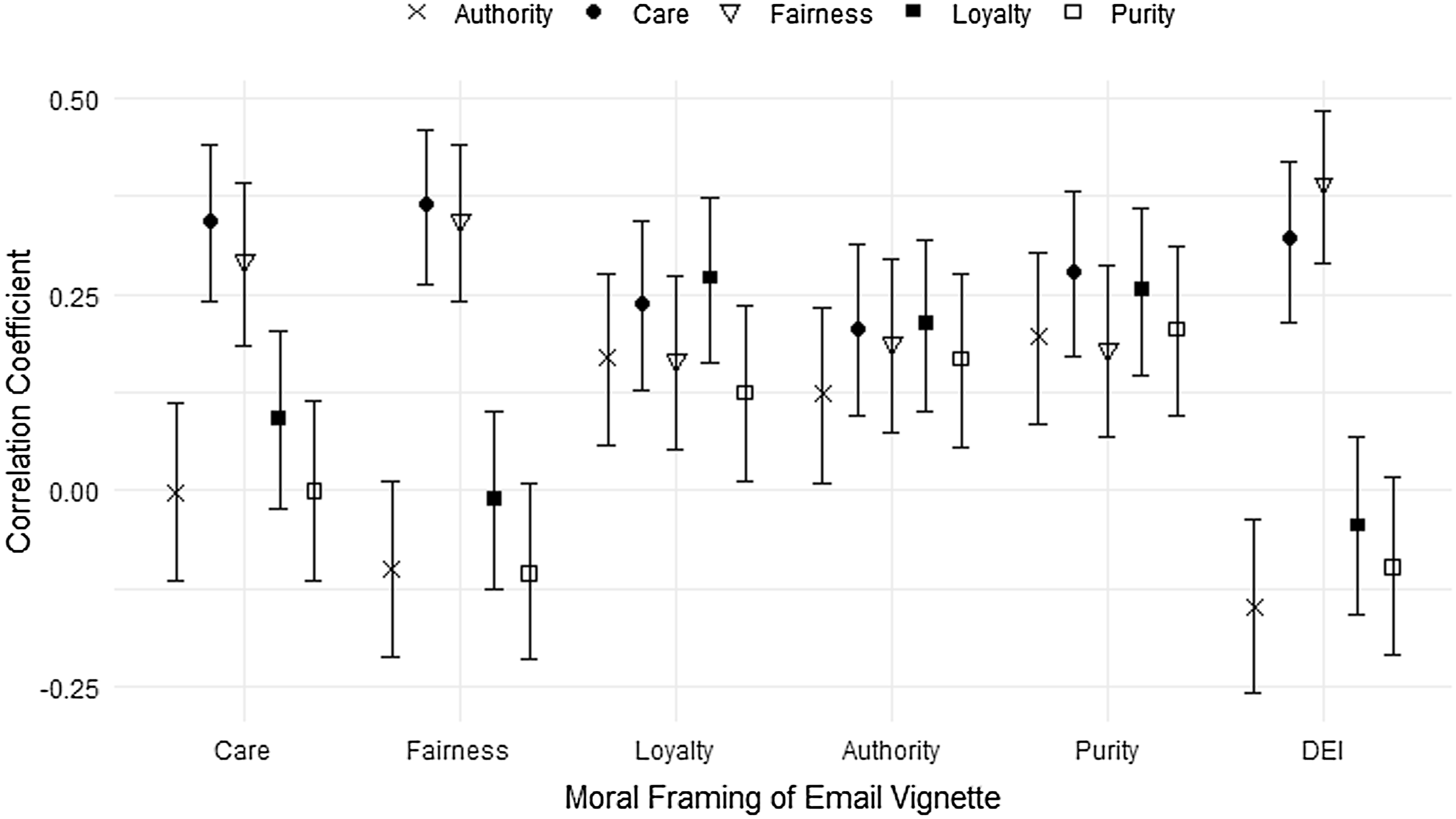

The relationships between individual differences in the five moral foundations were related to support and the likelihood of attending in different ways. There was a positive relationship between care and support and attendance for all framing types (r = .21 − .42, p < .01). Fairness was positively related to support and attendance for the various frames (r = .12 − .39, p < .01) but unrelated to supporting a loyalty frame. Loyalty was positively related to supporting loyalty (r = .12, p < .01) and purity (r = .19, p < .01) frames, as well as likelihood for attending loyalty- (r = .27, p < .01), authority- (r = .21, p < .01), and purity-framed (r = .26, p < .01) workshops. However, loyalty was not related to other frames regarding support or likelihood of attendance. Authority was positively related to supporting loyalty- (r = .16, p < .01) and purity-framed (r = .17, p < .01) workshops, as well as the likelihood of attending loyalty- (r = .17, p < .01), authority- (r = .12, p < .05), and purity-framed (r = .20, p < .01) workshops. Authority was negatively related to supporting fairness (r = −.20, p < .01) and both supporting (r = −.21, p < .01) and attending (r = −.15, p < .01) DEI-framed workshops. Purity was positively related to the likelihood of attending loyalty- (r = .13, p < .05), authority- (r = .17, p < .01), and purity-framed (r = .21, p < .01) workshops. In contrast, purity was negatively related to supporting care- (r = −.15, p < .01), fairness- (r = −.19, p < .01), and DEI-framed (r = −.23, p < .01) workshops.

Summary

Our results suggest that employees generally support and are likely to attend workshops framed using one of the five moral foundations or with DEI language. Care language was rated more positively in terms of both support and likelihood of attendance, with purity as the lowest rated. Interestingly, correlation analyses indicate support and likelihood of attendance are related to an individual’s moral foundations, such that those who were high in care were likely to support and attend the differently framed workshops. In contrast, authority and purity were positively related to support and attendance to frames closely associated with authority and purity but negatively related to support and attendance for care, fairness, and DEI framing language. Together, these results suggest that employee evaluations of DEI workshops may, in part, be related to how workshops are framed.

Table A1 Means, Standard Deviations, Intercorrelations, and Internal Consistency of Study Variables

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01. Cronbach’s alpha presented in diagonal.

Figure A1 Percentage of Support and Likelihood of Attendance for Emails Framed in the Five Moral Foundations

Note. Values indicate the percentage of support and the likelihood of attending. Percent favorable represents respondents who indicated a 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure A2 Relationship Between Moral Foundation Dimensions and Support Ratings Across Different Moral Training Frames

Note. Framing conditions are presented on the x-axis, correlation coefficients (r) are presented on the y-axis, symbols represent individual differences in the five moral foundations.

Figure A3 Relationship Between Moral Foundation Dimensions and the Likelihood of Attending Ratings Across Different Moral Training Frames

Note. Framing conditions are presented on the x-axis, correlation coefficients (r) are presented on the y-axis, symbols represent individual differences in the five moral foundations.