Introduction

The unprovoked full-scale attack by the Russian Federation against Ukraine on 24 February 2022 undermined the global legal order and, unlike isolated local armed conflicts and their latent support by the governments of the states concerned, became the first real war in the centre of geographical Europe in the twenty-first century with the open participation of European and non-European countries, along with arms supplies, humanitarian aid, sanctions decisions and global political pressure.

The war has had and continues to have a tremendous destructive impact on Ukraine. As of the beginning of 2025, almost three years after the start of the war, about 270,000 km2 of Ukraine’s territory was affected by the war, either through direct hostilities, mining of combat areas or as a result of shelling (Kyiv School of Economics 2023). However, the front line is constantly moving. The area of the temporarily occupied territories at its peak reached 125,000 km2 or 20.7% of the total territory of Ukraine, which is larger than the territory of Bulgaria, Hungary or Austria. As of January 2025, more than 154,151 crimes of aggression and war crimes committed by Russian troops have been documented in Ukraine (Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine 2025); 40,848 civilian casualties (9,824 killed and 24,223 injured) in the territory controlled by the Ukrainian government have been recorded since 24 February 2022 (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 2024); 19,546 children have been deported and/or forcibly displaced (Children of War 2025).

However, the consequences of the war go far beyond the territory of Ukraine in terms of humanitarian, environmental and food crises, and are long-lasting. Millions of Ukrainians became forcibly internally displaced persons or refugees, which put a significant burden on the host countries. The blockade of seaports and shelling of grain terminals have led to high risks of famine in countries that import Ukrainian grain. The blowing up of the Kakhovka dam by the Russian military caused an environmental disaster and pollution in the Black Sea, which was felt by all countries in the area. Moreover, the protracted war has demonstrated that the guarantees of global security are in ruins, and the global legal order is in a vulnerable state.

The war has become a turbulent time not only for the state and society. Crime and other illicit practices are particularly sensitive to social upheavals. At the same time, their adaptability is much more flexible than that of formal institutions. It is not surprising that the war has also had significant criminological consequences, transforming local and regional criminal trends.

Illicit economies in wartime have also undergone significant transformations, inevitably linked to changes in economic and business activities during martial law and mutations in general crime in the background of the war.

The intersection between conflicts and an intensification of high-profit criminal activities has been stressed by numerous international institutions and academic experts. Conflicts and crime have become more complex and deadlier (International Institute for Strategic Studies 2022; Interpol 2022). The historical experience of previous wars and armed conflicts has repeatedly evidenced the flourishing of illicit trade against the backdrop of war (Andreas Reference Andreas2013). Long-lasting contemporary wars demonstrate that, in their course, the illicit economy can become a dominant part of the official economy. In particular, in 2017–2018 in Afghanistan, the opiate economy was worth between 6 and 11% of gross domestic product (GDP), and it exceeded the value of the country’s officially recorded licit exports of goods and services (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2019).

Scholarly studies on the phenomenology of illicit trade in the context of armed conflicts, civil and international wars as their extreme form, are focused on the model of greed and grievance as motivating factors of conflicts for control of the resources (Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004), analysing the engagement of non-state actors (insurgents) in the redistribution of illicit trade flows (Olsson and Fors Reference Olsson and Congdon Fors2004). Previous research also reveals the supply by individual countries (or with the tacit consent of countries) of illegal items to combatants in order to evade the embargo (in particular, weapons) (Phythian Reference Phythian2000). Scholars emphasize that illicit trade serves as a crucial source of funding and support for insurgent groups (Abdulai Reference Abdulai2022). Due to the uniqueness of the conflicts and the peculiarities of the local illicit trade, specific terminology is emerging, e.g. “narco-guerillas”, “blood diamonds” and “conflict timber”. However, the main hypothesis and main finding are the same – illicit economies drive conflicts (Bhatia Reference Bhatia2021). Such a methodological approach would probably be appropriate for assessing illicit trade in Ukraine in the context of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine, launched in 2014.

However, the full-scale Russian–Ukrainian war of 2022 is more complicated – both in its geopolitical dimension, hybridity of forms and composition of the participants involved. It combines features of the classical understanding of war as aggression and the so-called new war (Kaldor Reference Kaldor2012) as a fusion of war, massive human rights violations and organized crime, therefore requiring another paradigmatic approach. The starting point for studying the relationship between illicit trade and war should be the understanding that armed conflict (war) is not only a consequence of criminal acts and a tool for fighting for resources. War is also a cause of transformations in crime and illicit markets (or at least a background phenomenon since the search for direct correlations may not always be evidence-based).

Although the issues of illicit economies and illicit trade have long been the focus of attention, the specifics of their functioning and, even more so, their counteraction in connection with such extraordinary and poorly predictable events as military conflicts and wars, are insufficiently developed – both in terms of methodology, epistemology and ontology of research. The criminological study of war is still in its infancy and needs to be rethought (McGarry and Walklate Reference McGarry and Walklate2019). However, in recent decades, the scientific field of “criminology of war” has been actively developing (Dryomin Reference Dryomin2022). There is limited academic research that demonstrates how the scientific findings of war and crime interact at a conceptual level. Several recent international publications were devoted to tobacco smuggling (GLOBSEC 2022), organized criminal economies in Ukraine in 2022 (Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime 2023), illicit alcohol (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2022), the illegal arms trade (Galeotti and Arutunyan Reference Galeotti and Arutunyan2023), illegal logging (Hrynyk, Biletskyi, and Cabrejo le Roux Reference Hrynyk, Biletskyi and Cabrejo le Roux2023) and drug trends (Kupatadze Reference Kupatadze2024; Scaturro Reference Scaturro2024). The relevance and practical value of these and other studies of this subject should be recognized. However, the war in Ukraine, in a global and, at the same time, divided world has created new problems not only in the security sphere but also in the economic sphere, which require new approaches.

The purpose of this research is not only to describe the state of illicit trade during the war but also to identify and explain the existing trends in terms of the dichotomy “war as a cause and consequence of crime”, as well as to highlight difficulties in countering it stemming from martial law. To drive forward the ideas of how conflict can exacerbate risks to illicit trade, this research also aims to study the relationship between conflict and illicit trade within the theoretical framework of the concept of the structure of illicit trade, distinguishing the types of illicit trade based on the criteria of the legal status of civil circulation of trade items (free, restricted, prohibited) and legal liability for the violation of their production and circulation provided by national law (criminal for serious offences or liability for misdemeanours).

Despite the clear specificity of the Russian–Ukrainian war, the study of illicit trade trends will reveal important patterns, both theoretical and applied, for the further development of research on wartime crime and the practice of countering it. The realities of the full-scale war will also reveal criminological “lessons” that can be learned by the international community in responding to other geodimensional conflicts. The findings of the study will also have a broader scope in the context of studying the links between organized crime and economic crime, as well as international crimes and crimes against peace and security.

From a practical point of view, the study’s findings can be used to develop recommendations for countering illicit trade in very specific armed conflict and war situations as a kind of crisis management that will resonate in post-conflict reconstruction. The idea is not only to reduce illicit trade and neutralize its “war” factors. It should be reoriented to the legal channel, increasing state budget revenues, living standards, de-shadowing the economy as a whole, and maintaining law and order. An important task of policy and law enforcement practice is to prevent the spread of illicit business transactions to post-war relations, when the state and society are no less vulnerable and organized crime is no less thirsty for profit.

Research Methodology

The methodology of criminological research on war is not well established. It contains gaps and is characterized by a lack of universalism, as each armed conflict, and even more so a war, has its own authentic specifics.

The actual circumstances of the war create additional problems for the research due to the lack or limited availability of official and/or alternative data from the temporarily occupied territories or territories of active hostilities, the secrecy of military-sensitive information, as well as threats to the personal safety of researchers conducting observation or data collection in war.

From the sociological aspect, the issue of war and its impact on society is studied within the framework of “polemology” (Bouthoul Reference Bouthoul1968). Polemology in its classical interpretation focuses on established social facts. The modern military situation, which is rapidly changing and is conditioned by the widespread use of technical means both to commit and conceal traces of war crimes, requires close attention to the study of events currently taking place. Today, it is obvious that war in the current dimension is a dynamic combination (system) of facts, among which the most significant are the deaths of civilians and the destruction of human infrastructure. The subject of polemology and criminology of war will be incomplete if it excludes the interpretation of socially significant facts from the criminological point of view in real time. Mandatory legal recording of war crimes, as well as criminological assessment of the state and development of society, should be the subject of modern criminological research. Within the framework of this doctrine, it is important to study and eliminate criminogenic factors and criminal practices as consequences of war (Dryomin Reference Dryomin2024).

A complex methodology exploiting both qualitative and quantitative methods, as well as an interdisciplinary approach in order to obtain comprehensive and representative empirical data, is applied for the study.

The sources of quantitative empirical data are: the Unified Report on Criminal Offences in Ukraine, the Unified Report on Persons Who Committed Criminal Offences for 2018–2024 (Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine); the Report on Persons Brought to Criminal Responsibility and Types of Criminal Punishment for 2018–2023 (State Judicial Administration of Ukraine); and official letters of the State Customs Service of Ukraine on requests for public information dated 15 August 2023 and 25 August 2023.

The source of qualitative empirical data is the Unified State Register of Court Decisions, which contains full, non-personalized texts of court decisions issued by Ukrainian courts of various levels. The sample of court decisions on offences relevant to illicit trade was formed in a stepwise manner. Out of 4,531 available court decisions on the cases referred to illicit trade for the period from 1 April 2022 to 31 August 2023, 126 verdicts were selected and studied using content analysis of the legal texts. The case study was applied to the most typical cases from the identified sample. Content analysis was also used to study statements and notifications for the period from 24 February 2022 to 31 January 2025 published on the official web portals of the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine, the National Police of Ukraine, the State Bureau of Investigation, the Security Service of Ukraine, the Bureau of Economic Security, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, the National Agency of Corruption Prevention, the Defence Intelligence of Ukraine and local law enforcement agencies regarding criminal offences related to illicit trade.

Illicit trade involves a much wider range of illegal activities, as well as closely intertwined legal activities, than is recorded in government crime or administrative offence reports and is, therefore, more difficult to monitor. The problem of latency is compounded by standards of presumption of innocence and, in some cases, the failure of the formal criminal justice system to detect and investigate the relevant illegal acts. To fill such gaps, this research used alternative sources, including journalist investigations and surveys of non-governmental organizations.

Doctrine Interpretation and Ukrainian Dimension of Illicit Trade before the Full-Scale War

The definition of illicit trade is absent at the regulatory level and, therefore, lacks legal certainty. This puts the academic approach in the spotlight. In the academic literature, illicit trade is usually considered as part of a broader concept of the unrecorded (informal, shadow, illegal) economy (Mazur Reference Mazur2006; Popovych Reference Popovych2001; Turchynov Reference Turchynov1996). One of the broadest definitions of the shadow economy includes “economic activities and the income derived from them that circumvent government regulation, taxation or observation” (Dell’Anno and Schneider Reference Dell’Anno and Georg Schneider2009). Smith uses the definition “market-based production of goods and services, whether legal or illegal, that escapes detection in the official estimates of GDP” (Smith Reference Smith1994:18). The purely “criminal” component is usually connected with organized crime and proceeds from areas outside the official economy. The other component is mediated by economic (white-collar) crime and uses the infrastructure of the formal economy. “The informal economy is now seen as a universal feature of industrialized countries, encompassing everything from home-based self-sufficiency to the criminalization of the economy” (Hart Reference Hart, Guha-Khasnobis, Kanbur and Ostrom2006).

Scholarly developments on the illegal economy mediate the authorial conceptual understanding of illicit trade. In a narrow sense, illicit trade involves the activities of collective and individual actors in the sale and purchase of goods and services to meet demand and make a profit with the violation of the current laws (legislation). However, this approach significantly limits the possibilities of a criminological systemic–structural approach to studying trends in illicit trade.

To achieve the objectives of this study, a broader approach is proposed, according to which illicit trade means the movement of goods and/or services from producer to consumer and deals not only with a sale or purchase but also auxiliary or intermediary operations with the prohibited items or the violation of the procedure of production, transit, distribution and/or possession. Such a broad approach is used in the practice of the World Health Organization. Illicit trade is defined in Article 1(а) of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control as “any practice or conduct prohibited by law and which relates to production, shipment, receipt, possession, distribution, sale or purchase including any practice or conduct intended to facilitate such activity” (World Health Organization 2005).

Illicit trade is more extensive than illegal trade since, in addition to crimes and offences, it forms the grey areas of commerce (Shelley Reference Shelley2018) and includes harmful activities that are not regulated by law, not formally prohibited, or even legal as a part or stage of trading.

Given the diversification of illicit trade, it is reasonable to divide it into two groups that are relatively homogeneous in terms of the specifics of its mechanisms. The key criterion for distinguishing is the legal status of civil circulation of trade items (free, restricted, prohibited). An accessory criterion is the type of legal liability (criminal for serious offences or administrative for misdemeanours) provided by national law:

І. Illicit (criminal) trade (or criminal trade outside the economic sphere) – relates to trade in goods and/or services that are completely withdrawn from civil circulation (human trafficking, migrant smuggling, organization of prostitution, drug trafficking, trade in personal data or other confidential or secret information, etc.) or those that are in limited civil circulation (trade in weapons, potent drugs, endangered plants and animals, etc.). This group of illicit trade predominantly entails criminal liability.

ІІ. Illicit (illegal) trade (or illegal trade within the economic sphere) – relates to trade in goods and/or services that are in civil circulation (their production or sale is not prohibited or restricted), but with violation of the procedure of production, circulation or sale and/or with concealment from accounting and taxation (trade in excisable goods, counterfeit products, cultural property, subsoil and mineral resources, etc.). Illegal trade within the economic sphere involves both criminal and administrative liability, depending on the assessment of the public danger, the severity of the damage caused, and the elements of offences specified in the relevant laws. It is essential that both crimes and misdemeanours of this group have a similar mechanism of commission with the receipt of illegal profits, the formation of the delinquent’s personality and deterministic links, and, depending on the willfulness of the legislator, can migrate from the category of crimes to the category of misdemeanours and vice versa.

Understanding the mechanisms of illicit trade within each group is not only of academic but also practical importance, affecting the distribution of functional responsibilities and competencies of law enforcement agencies, the specifics of documenting and investigating related crimes, and the development and application of relevant preventive measures.

The peculiarity of illicit trade in Ukraine is conditioned by the contradictions of the Soviet-era administrative-command economy (Chernyavsky Reference Chernyavsky2015), as well as the primary concentration in legal production and consumption in the absence of market relations per se. The shadow economy in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which until 1991 included Ukraine, emerged in a context of strict regulation of trade and scarcity, concentration of key resources in the hands of the state and state officials, and a ban on entrepreneurial activity and foreign trade. The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and the collapse of the USSR in 1991 triggered a real boom in illegal markets throughout the former Soviet Union.

The opening of the eastern borders greatly increased the movement of people, goods and capital between the two previously separate parts of Europe, and thus the circulation of illicit goods and dirty money (Fijnaut and Paoli Reference Fijnaut and Paoli2004). Located in the geographical centre of Europe, Ukraine has become a buffer zone for transnational illicit trade. It is a country with a weak legal system, strong bureaucracy and corruption, but at the same time with a developed industrial and transport infrastructure, long stretches of porous land borders, and river and sea ports. These circumstances have created preconditions for the formation of criminal hubs on the territory.

Before the full-scale armed invasion, Ukraine had a stable illicit trade sector, which was linked to the general shadowing of the economy. The following points are key to understanding its essence.

Firstly, the collapse of the Soviet Union at the first stage of reforms led to the destabilization of government, administration and the economy. Against the backdrop of the de facto deinstitutionalization of official state bodies, a “new” economy was formed based on informal or illegal rules of behaviour. The niches of total shortages of goods and services were filled by the so-called “tsekhovyky”, who worked without official permits but supplemented the legal economy. “The shadowy actors” extensively used corrupt connections, embezzlement and their own official position. Criminal ideology became the basis for the formation of a new wave of economic organized crime. The so-called “new” crime, as a young system with great flexibility and adaptability, has become a link between traditional criminal activity and its values and modern forms of organized economic crime that demonstratively spread its standards of behaviour. The criminal situation in the economy in those years was largely determined by organized forms of economic crime. There was an interconnected process: representatives of criminal business infiltrated government structures, and the government cooperated with criminal business by providing illegal services and privileges. Thus, new informal but binding “rules” of behaviour in the economic sphere, especially in illicit trade, were formed. In such a way, illicit trade and related informal practices in Ukraine have gone through an irreversible process of institutionalization and have acquired stable forms close to formal social institutions and legal trade (Dryomin Reference Dryomin2009:388–91).

Institutionalization means a quantitative and qualitative transition from isolated cases to the formation of a structured system and the actual replacement of dysfunctional/insolvent formal institutions. When state institutions do not perform their functions properly, especially when the rule of law is not ensured or economic activity of entities within the framework of formally defined rules leads to high transaction costs, then criminal organizations become effective, guaranteeing, organizing and streamlining the production, exchange and redistribution of resources (Boyko Reference Boyko2008).

The institutionalization of illicit trade became possible due to the functionality of the shadow economy in Ukraine, which during the post-socialist transition and waves of economic crises in the 1990s and 2010s had a compensatory value, providing informal employment, serving as a way to accumulate initial capital, reducing social tensions caused by significant economic differentiation of population strata, discarding outdated norms of economic activity regulation and “groping” for innovations (Melnychuk Reference Melnychuk2012). However, the short-term constructiveness of the shadow economy at the initial stages of market modernization in the former socialist countries turned into long-term destructiveness, hindering the formation of an effective market economy model and becoming a threat to Ukraine’s economic security.

A tangible trend in recent years has also been the digitalization of illicit trade using cryptocurrencies, remote access to accounts, and online “agreements” on sales and purchases, in particular in the field of drug and arms trafficking, etc.

Secondly, illicit trade is based on the economic laws of supply and demand. From this perspective, Ukraine has traditionally been a supplier of human trafficking, excisable goods (alcohol, tobacco), natural resources (timber, amber), a recipient and transit country for drugs (cocaine, heroin, synthetics) and counterfeit and smuggled industrial products.

The trade is facilitated by the long-term interaction of a large number of persons within the organizational structure typical of organized forms of crime, which includes several levels and structural units with a hierarchical structure of the management and a network structure of regional branches, the presence of legal links to disguise criminal activity and diversify assets, well-developed money-laundering mechanisms, and the establishment of channels and distribution markets. The involvement of state employees in illicit trade as organizers of schemes or persons facilitating the implementation of schemes based on bribery relations was typical, as corruption in Ukraine is often perceived by officials as a source of constant income, and corrupt actions become clichés. At the same time, corruption is characterized by the highest level of latency, which is due to the difficulty of detecting certain offences (because of the interest of both parties, the existence of extensive friendly relations, etc.) and, accordingly, punishing the perpetrators (Shostko Reference Shostko2018).

The demand for illicit goods and services in Ukraine is fuelled by the low consumer culture of the population, which was formed during the Soviet shortages, legal nihilism, and artificial hype that can be created by dealers, in particular by promoting new “fashionable” synthetic drugs or taking advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the high demand for medical supplies was not met by the public or legal private sectors.

Thirdly, illicit trade in Ukraine is driven by large-scale illicit financial flows and the circulation of dirty capital generated outside the trade sector, including through informal employment or corruption, tax evasion, abuse in the banking and financial sectors, public procurement and public spending, etc. The conversion of power into money and money into power makes it possible to illegally finance political parties or influence political processes and decision-making. A significant share of illegal trade in Ukraine is related to smuggling, which in turn is caused by differences in tax systems/tax pressure between neighbouring and other jurisdictions.

Last but not least, before the full-scale war, Ukraine has already had an experience with illicit trade and countering it in the context of the armed conflict caused by Russia’s undeclared attack since 2014.

Thus, at the beginning of 2014, self-proclaimed pseudo-republics – Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics – were formed in smaller parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the eastern part of Ukraine with military, armed, financial and informational support from Russia. These pseudo-republics were recognized as terrorist organizations in Ukraine, and an anti-terrorist operation was launched. The quasi-border contact line has become a de facto grey zone with active illegal trade.

The highest intensity of illicit trade in the anti-terrorist operation zone occurred in 2015. The gross profit of illicit traders – excluding bribes, travelling expenses, and taxes of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics – could reach 200–250% of the amount spent on goods in 2015 (NAKO – Independent Anti-Corruption Commission 2017). Certain districts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions have turned into an inexhaustible source of counterfeiting. In 2016–2017, its own production appeared here – both industrial (Hamaday Tobacco Company, Luhansk Tobacco Factory) and as small businesses. Most of the cigarettes produced in Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics illegally ended up on the border territories of the Russian Federation and neighbouring Ukrainian regions (Ukrainian Institute for the Future 2020).

At the same time, the Russian Federation illegally annexed the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a peninsula within Ukraine. Trade with Crimean businesses became essentially illegal, including through the violation of economic sanctions.

The full-scale invasion of 2022 and the prolonged war have significantly changed the ecosystem of illicit trade in Ukraine and in the region.

Illicit Trade in Wartime: Booming vs Extinction

Criminal Trade Outside the Economy in Wartime

Trade in Drugs and Pharmaceuticals

Before the full-scale war, drugs used to enter Ukraine through a wide network of couriers by air, sea, land transport and post. Ukraine was a transit country for smuggling heroin from Asia, psychoactive compounds from China, and cocaine from Latin America and Europe.

Since 24 February 2022, due to the closed airspace and sea borders, destroyed road infrastructure and active front line, traditional drug routes have been disrupted. The Russian naval blockade caused Odesa to lose its role as a smuggling hub in the Black Sea, affecting incoming drug flows and shifting drug smuggling to the western border, in particular with Poland. The war may also have displaced drug trafficking routes from and through Ukraine towards the Balkan region (Scaturro Reference Scaturrо2023).

As a result of the shift of transnational drug channels to bypass Ukraine, the quantity of all types of seized drugs on completed proceedings decreased by 16% in 2022–2023 compared to 2021. In 2024, the quantity of seized drugs slightly increased, but still remained below the 2021 level.

The majority of seizures were made regarding drugs carried by automobile transport – about 60%; the postal service was also a considerable channel. There have also been changes in the structure of imports and exports of drugs in Ukraine. In particular, the number of detected cases of importation into Ukraine in wartime was more than three times higher than the number of cases of exportation (State Customs Service of Ukraine 2023, 2025).

Although heroin and cocaine availability within Ukraine after the full-scale invasion appears to have declined, synthetic drug production and use appear to have been less affected (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction 2023). Production centres for synthetics have moved closer to the frontline regions (State Bureau of Investigation of Ukraine 2023).

Among all recorded drug-related criminal offences (Articles 305–320 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), three types of crimes had the highest share in 2022–2023:

Illegal production, manufacture, purchasing, storage, transportation, or sending of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances, or their analogues not for selling purposes (Article 309);

Illegal production, manufacture, purchasing, storage, transportation, sending or sale of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances or their analogues (Article 307); and Planting or cultivation of opium poppy or cannabis (Article 310, minor offence).

The shares of the three above-mentioned types of crime for 2022 and 2023 were 59% (52%), 29% (37%) and 5% (1.5%), respectively.

The law enforcement agencies focus largely on detecting petty crimes committed by drug users. It can be argued that the desire to produce favourable “reports” is frequently a primary motivator behind law enforcement actions, leading them to shift their focus from combatting drug traffickers to targeting drug addicts.

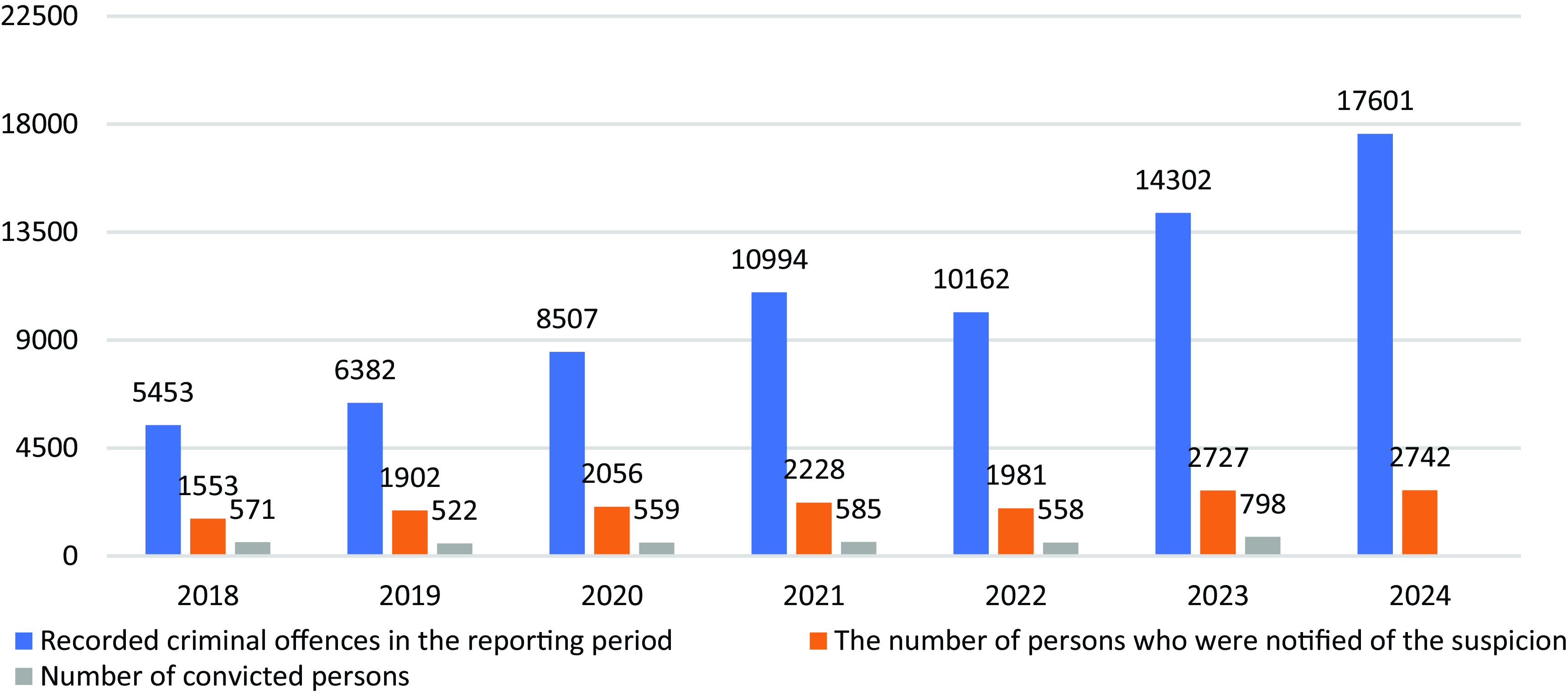

Since 2018 (except for 2022), we can observe an increase in the number of registered criminal offences that are related to drug trafficking – Article 307 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (see Figure 1). However, other indicators show only a slight upward fluctuation.

Figure 1. Illegal production, manufacture, purchasing, storage, transportation, sending or sale of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances or their analogues (Article 307 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), 2018–2024.

Source: Own study – based on statistics provided by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine (https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-zareyestrovani-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-ta-rezultati-yih-dosudovogo-rozsliduvannya-2; https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-osib-yaki-vchinili-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-2) and the State Judicial Administration of Ukraine (https://court.gov.ua/inshe/sudova_statystyka/).

Data on the involvement of organized crime groups among all recorded drug-related crimes showed approximately the same amount in 2021 and 2022. The number of members of organized crime groups that were officially notified of the suspicion decreased almost two times in 2022 and in the next two years returned to the 2021 level. During 2022–2023, the proportion of accused organized crime groups among all convicted persons was only 0.3 %.

More than 47 % of the total number of convicts for drug crimes were released from punishment in 2023.

Our research has revealed that certain police officers cover up the leadership of drug criminal groups from detection or are themselves directly involved in such criminal business or take part in it.

Considering an increase in the number of drug users, predominantly opioid users, from 14.7 (2017) to 17 (2022) per 10,000 population (Institute of Forensic Psychiatry of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine 2023) in Ukraine and the tiny number of convicted traffickers (see Figure 1), there is evidence of a growing latent drug market. Evidently, this led to the rise in the illegal income of criminals and those who protect them from detection, which is then reinvested in further criminal activity.

The illicit market of counterfeit pharmaceuticals is closely related to the illicit drug market.

Due to imperfections in the laws regulating the pre-trial and trial stages, there are difficulties in proving the facts of the turnover of counterfeit medicines in Ukraine. An analysis of the official reports revealed that only 19 criminal offences were recorded under Article 321-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (“Counterfeiting of medicines or the trafficking of counterfeit medicines”) in 2021, 16 in 2022, 26 in 2023, and 14 in 2024. According to judicial statistics, during 2021–2023, only one criminal actor was sentenced.

At the same time, the volume of illicit medicines markets in Ukraine amounts to more than €97 million per year (Levchenko Reference Levchenko2022). The “black” market is represented by counterfeit medicines that are manufactured illegally and distributed through offline and online networks. The “grey” market consists of the importation of drugs without complying with the rules of transportation, temperature conditions, and outside the official supply chain. Medical staff are sometimes involved in these schemes, offering unregistered medicines to their patients, over-the-counter medicines, or analogues of expensive drugs at a lower price from unofficial dealers.

The coronavirus pandemic and the resulting need for pharmaceuticals have intensified the illicit trade in pharmaceuticals, including through online sales. Since the outbreak of the war, the Government of Ukraine has simplified pharmacy operations and reduced control over them to meet the emergency needs for certain medicines. However, this has led to an increase in the activity of online pharmacies, which are considered to be the main source of sales of counterfeit medicines (Pashkov and Gnedyk Reference Pashkov and Gnedyk2022).

The war-driven shortage of certain types of medicines, mostly imported, for the treatment of cancer, hepatitis and HIV, has increased the demand for these medicines on the illicit market and led to new schemes for importing counterfeit drugs in bulk under the guise of humanitarian aid.

Illegal Movement of Conscripts across the State Border as Trade in Services

Since the outbreak of the war, the closure of border crossing points with Russia and Belarus and the cessation of traffic on sea and air routes have reduced the level of illegal migration in Ukraine. However, the introduction of martial law in Ukraine and a travel ban for men aged 18 to 60 years, who are liable for military service, created a new criminal market of services of high demand from conscripts trying to avoid military service by fleeing the country.

The examined official data demonstrated the increasing number of proceedings under Article 332 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Illegal movement of persons across the state border” almost four times in 2022 and more than nine times in 2024 in comparison with the pre-war 2021 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Illegal movement of persons across the state border (Article 332 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), 2018–2024.

Source: Own study – based on statistics provided by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine (https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-zareyestrovani-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-ta-rezultati-yih-dosudovogo-rozsliduvannya-2; https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-osib-yaki-vchinili-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-2) and the State Judicial Administration of Ukraine (https://court.gov.ua/inshe/sudova_statystyka/).

In 2022, the State Border Guard Service detained 9,926 Ukrainian citizens, men of military age; 53% of them were detained at border crossing points, with the rest outside of border crossing points (Bratko, Veretilnyk, and Ovchar Reference Bratko, Veretilnyk and Ovchar2023:11). The number of conscripts who managed to leave Ukraine illegally is likely to be many times higher. As a rule, they are legalized abroad by obtaining temporary protection status and, therefore, it is currently impossible to identify them as illegal immigrants without an appropriate official investigation, as well as to establish their exact number.

Trafficking services outside of border crossing points are mostly offered by groups whose members are residents of border regions in western or southwestern Ukraine. “Clients” are found through a network of personal contacts or by posting adverts in Telegram channels.

In some cases, conscripts were smuggled through the non-controlled territory of Ukraine, as well as the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea to the territory of the Russian Federation (National Agency on Corruption Prevention 2022).

However, corruption among persons obliged to exercise control at official checkpoints in full compliance with their functional responsibilities is more widespread. This sphere of activity does not belong to the service sector, as it is carried out on the basis of special legislation on the state border and the state border service, which refers to ensuring national security through control. In fact, due to corrupt officials, the formal mechanism for checking and controlling the movement of people, transport and cargo has become a type of criminal business. In this case, illegally obtained or forged documents for entitlement to travel under the guise of those released from military service for health reasons, disabled persons or persons accompanying them, volunteers, and drivers providing passenger transport are in higher demand (Melnychuk Reference Melnychuk2023).

Depending on the complexity of the scheme and the degree of legality of the border crossing, the cost of such a “service” ranges from US$1,000 to $20,000.

Despite the involvement of organized crime groups, the market for the smuggling of conscripts is not hierarchical. Schemes sometimes emerge sporadically and locally, but after successful approbation, they become clichés and are entrenched as criminal practices.

Significant discretion in the competencies of officials who make decisions or participate in the processes of crossing the state border by men liable for military service allows corruption schemes to be implemented with the participation of military commissars, employees of medical commissions, local state administration and law enforcement.

Indirect but eloquent evidence of the involvement of the senior staff of the territorial recruitment centres in the scheme of conscription evasion and transferring conscripts abroad is the millions of their unjustified assets obtained during the war, which were revealed by the National Agency on Corruption Prevention while lifestyle monitoring.

Illegal movement of conscripts across the state border reflects not only the supply and demand of the illegal services caused by the war but also the extent of corruption and abuse of influence at the highest levels of government and political positions. For example, a current Ukrainian member of parliament (MP) received a notice of suspicion of influence peddling. According to the investigation, the MP, in consideration for the bribe, ensured that the authorized officials of the regional military administration made a decision to allow the conscripts to travel outside Ukraine during martial law (National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine 2023). In another case, a current MP sent letters on his own behalf to the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine to grant permission for men to leave the country under the guise of drivers who were supposed to accompany him abroad. However, 18 men of conscription age crossed the state border without him, as he was either already abroad or had not left the country at all at the time of their crossing (State Bureau of Investigation of Ukraine 2025).

According to the assessments of the duration of the threats, trade in services for the transfer of conscripts abroad is short term. It is assumed that if martial law is cancelled and restrictions on travel from Ukraine are removed, there will be no prospects for the development of this specific war-related illicit market. However, even after the war ends, there is a threat of new waves of illegal migration after the resumption of the functioning of border crossing points on the air and sea routes. Attempts to cross the state border by persons involved in war crimes and anti-Ukrainian activities to avoid responsibility are also possible in the foreseeable future.

Human Trafficking

The main risks of intensification of human trafficking are associated with the vulnerable position of Ukrainian refugees and internally displaced persons, the amount of which ranges from 11 to 14 million during the war.

The majority of persons fleeing the war are women, children and persons with disabilities. All are ideal potential victims for criminal networks. Many Ukrainians, especially in the early days of the war, crossed the border without properly validated identity documents. In addition, minors received an extraordinary possibility to travel with relatives or even strangers without formalized parental permission. Many travelled without having any idea of their final destination, without knowledge of the language or laws of the host state, which deepened pre-existing vulnerabilities.

According to the survey conducted by the International Organization for Migration between July and August 2022, every second Ukrainian (59%) risks getting exploited, being willing to accept at least one type of risky job offers abroad or in Ukraine. Almost a half of this risk group would accept a risky job offer abroad: to work without official employment and even in locked premises, being unable to leave a workplace freely; to irregularly cross the border; and to give their passports, phones and personal belongings to an employer (International Organization for Migration 2022).

So far, international organizations and government agencies of European countries have not recorded a considerable increase in cases of labour, sexual and other exploitation of displaced Ukrainians. However, in early 2023, the first high-profile case of dismantling the Ukrainian refugee exploitation network in Spain was reported (Ministerio del Interior de España 2023).

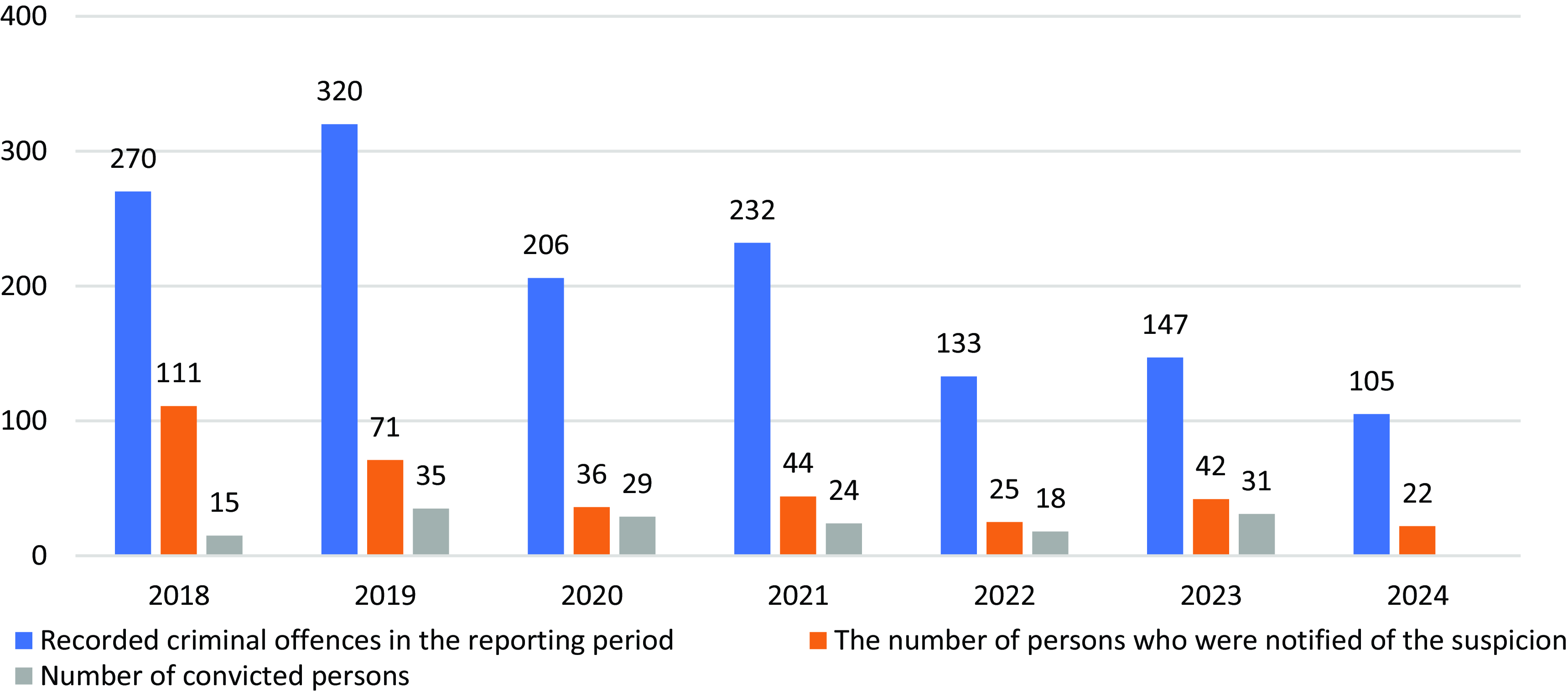

National law enforcement practice and statistical observations record a decrease in detected cases of human trafficking. This may illustrate the difficulties in assessing the scale of human trafficking during the war, given the natural decline in the state’s capacity to detect and prosecute such cases, as well as the potential concealment of human trafficking under the guise of war crimes, especially those involving sexual violence in the occupied regions. Thus, in 2022 and 2024, there were almost two times fewer recorded crimes than in 2021 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trafficking in human beings (Article 149 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), 2018–2024.

Source: Own study – based on statistics provided by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine (https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-zareyestrovani-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-ta-rezultati-yih-dosudovogo-rozsliduvannya-2; https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-osib-yaki-vchinili-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-2) and the State Judicial Administration of Ukraine (https://court.gov.ua/inshe/sudova_statystyka/).

The low number of convictions, comparing with the number of registered criminal offences, is evidence of general problems in the criminal justice system as well as specific problems: changes in particular legislation and imperfect edition of the Article 149 “Trafficking in human beings” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, understaffing and employee turnover of special units, weak intelligence and operational work.

It is also important to bear in mind that it usually takes some time for trafficking to be discovered, as people remain exploited for some time; for example, victims of trafficking may be held for a month or sometimes for years. In fact, many victims do not realize that they are being exploited (Dean Reference Dean2022).

Human trafficking is mostly committed in organized forms. However, the indexes of detecting organized crime groups involved in this crime are very low in Ukraine. The analysis of reports of judicial statistics revealed that in 2020 six people were convicted for this crime within an organized crime group (out of 29 of all convicted persons for this crime), the next year there were five criminal actors (out of 24), and in 2022–2023 no member of organized crime groups was convicted.

Along with the risks of the traditional human-being market, a new slavery market directly related to the war appeared, facilitated by the state-aggressor as a collective criminal. Not accidentally, the United States put Russia into a list of countries engaged in human trafficking or forced labour in 2022:

Russia-led forces forcibly moved thousands of Ukrainians, including children, to Russia through “filtration camps” in Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine, where they were deprived of their documents and forced to take Russian passports. Once in Russia, thousands of Ukrainians were forcibly transported to some of Russia’s most remote regions, and Russian authorities reportedly forcibly separated some Ukrainian children from their parents and gave the children to Russian families (United States Department of State Publication Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons 2022).

The forced movement is the state policy of Russia and is centrally coordinated by its government. Illegally transferring and deporting people is a grave violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention and constitutes a war crime.

In addition, car mechanics in the occupied territories have been forced to do slave labour for the repair of military equipment, as well as civilians being forced to dig trenches or clear rubble.Footnote 1

Forced involvement in military actions as a form of exploitation has also become widespread in occupied territories and Donetsk and Luhansk People’s pseudo-Republics. Since the beginning of 2022, the aggressor state has forcibly mobilized 55,000 to 60,000 men into its army in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine (Defence Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine 2023).

Thus, citizens of Ukraine in the Russia-occupied territories appeared to be the most vulnerable to trafficking during the war.

Illegal Trade Within the Economy in Wartime

Trade in Excisable Goods

Excisable goods in Ukraine include ethyl alcohol, alcoholic beverages, beer, tobacco products, liquids for e-cigarettes, cars, car bodies, motorbikes, liquefied gas, petrol, diesel fuel, other fuel material and electric power (Clause 215.1 of Article 215 of the Tax Code of Ukraine).

Before 24 February 2022, Ukraine itself suffered from cigarette smuggling, which came from Belarus, Transnistria, and Donetsk and Luhansk People’s pseudo-Republics. A separate direction was the transit smuggling of cigarettes from China and the United Arab Emirates – this illegal international channel used to pass through Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea and then went to the EU countries (Nikiforenko and Vikhtiuk Reference Nikiforenko and Vikhtiuk2021).

With the beginning of a full-scale invasion, the main channels of illegal cigarette supply to Ukraine from the Belarus and Russia sections of the border, sea routes and temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine were blocked. Simultaneously, the import of illicit tobacco products to the EU and other countries from Ukraine has reduced.

Due to the war, in March 2022, the whole legal tobacco market in Ukraine fell by 10% (Shtuka Reference Shtuka2022). This is in line with a general tendency in the Ukrainian domestic market, where total measured cigarette consumption has been declining since 2018 (KPMG 2023). Meanwhile, the average annual level of the illicit cigarette market increased from 10% in 2020 to almost 22% in 2022 (Kantar Ukraine Reference Ukraine2022).

Tax losses to the State Budget of Ukraine in 2023 from the illicit tobacco market are estimated at approximately €537 million (Ukrainian hryvnia [UAH] 21 billion) (European Business Association 2023).

The vast majority of the illicit market consists of cigarettes produced at Ukrainian enterprises, labelled for sale in duty-free shops or for export, and counterfeiting cigarettes (Kantar Ukraine Reference Ukraine2022). Most illicit tobacco is sold in markets and shops next to the legal cigarettes.

Duty-free cigarettes are produced without excise stamps, resulting in no tax being paid upon their sale. Typically, they are distributed through market retailers, as well as anonymous websites and Telegram channels. This practice has had a damaging impact on the Ukrainian economy. On 1 October 2023, the law (Law of Ukraine 2023) entered into force, which prohibits the manufacture of tobacco products and liquids for e-cigarettes with the purpose of sale in the duty-free regime and actual sale of such products until the end of martial law. It would seem that this might make one of the biggest illegal schemes not to work. However, this is not entirely true. In September 2024, Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine detectives together with border guards found and seized two million packs of cigarettes with duty-free labelling worth UAH 165 million (€3,720,000) in sea containers in one of Odesa’s ports (Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine 2025).

New routes for tobacco smuggling importation have arisen; for instance, the organizers of the scheme have “laid” routes through Europe. In the accompanying documents for the European control services, it is noted that the goods are allegedly transiting to third countries and, later, trucks with cigarettes (from Belarus) enter Ukraine from EU countries under the guise of empty transport (State Bureau of Investigation of Ukraine 2022).

Another important tendency is that the illegal manufacturing of cigarettes partially moved from the eastern and central regions of Ukraine to the western part of the country and to neighbouring countries in 2022–2024. For example, in October 2022, employees of the National Tax and Customs Service of Hungary caught a rubber mattress with 10,000 packs of smuggled TM Compliment cigarettes manufactured at the Vynnyku tobacco factory (Lviv region) in the Tisza River on the border with Ukraine (Varianty 2022).

The activity of the law enforcement agencies aimed at combatting illegal manufacturing of tobacco products in Ukraine in 2022–24 has intensified. State agencies detected a number of places of production of illicit tobacco products, seized significant quantities of counterfeits of well-known brands, raw materials, equipment and packaging used in the production of illicit tobacco.

However, investigations often take too long before the cases are sent to courts. As a result, reviews of the cases by courts are not always effective. It seems that the appearance of active work is being created that does not affect the real schemes. Despite large-scale searches and investigations, there are increasingly frequent reports of the resumption of illegal tobacco production operations.

It should be stressed that, unfortunately, the fight against illicit tobacco products in Ukraine is experiencing difficulties. Quite often, high-ranking officials (including top officers of law enforcement agencies, some local council members, and people’s deputies) are trying to participate in the illicit tobacco business instead of fighting it.

The significant difference in excise tax administration in neighbouring countries induces transnational illicit trade. That is why it is believed that making excise tax on tobacco products in European countries equal would make smuggling unprofitable. Increasing the excise tax on tobacco may also be a powerful tool for reducing tobacco use. On the other hand, high excise taxes (especially if they are increased too fast) make illicit trade within the country profitable.

One of the positive solutions to partially reduce the level of illicit tobacco products is digital cigarette labelling along with a system of tracking the movements and circulation of each pack of cigarettes, which is to be introduced in 2026.

Some shifts in trends during wartime are also observed in the illicit fuel trade compared to the pre-war period. In 2020, the share of the illicit gasoline market in Ukraine was 25%, diesel fuel 19%, and autogas 34%, as a result of which budget losses due to non-payment of taxes were estimated at UAH 20 billion every year (€656.5 million) (Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine 2021).

In 2022, petrol prices nearly doubled following the aggressive actions of Russia, leading to a significant shortage of fuel. The largest oil refineries were destroyed by Russian missiles. The Ukrainian government and private businessmen went to extraordinary efforts to organize the import of fuel and lubricants across Ukraine’s western borders. A special anti-crisis task force made up of civil servants and businessmen was set up. New legislation came into force and temporarily cancelled the excise tax on fuel and reduced the value-added tax (VAT) rate from 20% to 7%. For the most part, the fuel shortage problem was resolved at the beginning of 2023. According to the experts, the shadow market share during this period decreased to 10–11% (Kuchabskyi Reference Kuchabskyi2023). Since July 2023 the VAT tax rate for fuel and other oil products has returned to 20 %. This may cause activation of the shadow market.

Criminal liability is provided for illegal manufacturing, storage, sale or transportation for the purpose of sale of excisable goods (Article 204 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine). A decrease in registered crimes by 25% and individuals who committed them by 42% has been observed in 2022 when compared to 2021 (see Figure 4). During this period, the conviction rate fell by 4.5 times. Further, in the next two years, a significant increase in the number of reported offences can be noticed. However, the number of suspected criminal actors is three times smaller than the number of facts of criminal offences.

Figure 4. Illegal manufacturing, storage, sale or transportation for the purpose of sale of excisable goods (Article 204 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), 2018–2024.

Source: Own study – based on statistics provided by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine (https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-zareyestrovani-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-ta-rezultati-yih-dosudovogo-rozsliduvannya-2; https://gp.gov.ua/ua/posts/pro-osib-yaki-vchinili-kriminalni-pravoporushennya-2) and the State Judicial Administration of Ukraine (https://court.gov.ua/inshe/sudova_statystyka/).

It is worth noting that Article 204 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine is not clear enough, making it difficult to apply in practice. Since offences under Article 204 (first and second paragraphs) belong to non-serious crimes, many covert investigative actions cannot be used to detect them. The absence of clear criteria allows some corrupt investigators to alter the qualification of the offences and apply Article 177-2 of the Code on Administrative Offences of Ukraine “Production, purchase, storage or sale of counterfeit alcoholic beverages or tobacco products” and close criminal cases on that basis. According to the official data, the number of persons liable under the above-mentioned article in 2022 has decreased almost 20 times compared to 2021, and the amount of the imposed fine for the foreseen violation was a total of UAH 1020 (€25). We may conclude that this type of legal responsibility does not prevent illicit trade in tobacco and alcohol products or fill the budget.

Criminal networks active in this business are usually not detected. Billion losses of the state due to the existence of the illicit market do not correlate in any way with what the state returns through fines and confiscation.

Abuse of Humanitarian Aid

The humanitarian crisis caused by the war and the need to support Ukraine’s armed forces have necessitated the involvement of a variety of humanitarian aid, mostly imported from abroad. To facilitate and speed up its delivery to Ukraine, import procedures have been significantly simplified, and import tax exemption has been introduced. For the period of martial law, in Ukraine, goods are recognized as humanitarian aid on a declarative basis and do not require a specific decision of authorized state bodies.

The established preferential border control regimes and significant flows of humanitarian aid have also made it attractive to illegally receive, distribute and use it for profit. The study of the collected empirical data revealed that the most typical abuse of humanitarian aid was primarily the sale of humanitarian aid, military clothing or supplies through markets, chain stores or Internet sites, which were donated to pseudo-volunteer organizations for free, misappropriated or declared as direct assistance to the army following its needs (Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine 2023). Often, at the first stage of the criminal schemes, the offenders collected donations from the public or volunteer funds for their own profit. Subsequently, they imported bulletproof vests, helmets, knee pads, thermal imagers, optical sights, unmanned aerial vehicles, etc., and sold them on the domestic market of Ukraine at prices three times higher than the purchase price (Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine 2022).

Another notable trend is the importation of commercial products under the guise of humanitarian aid in order to use the preferential import regime and avoid taxation.

A typical pattern in the abuse of humanitarian aid, as well as in the above-mentioned illegal movement of conscripts across the border, is the involvement of heads of local military administrations, mayors and other officials responsible for receiving or distributing aid. Schemes for clearing goods under the guise of humanitarian aid with the participation of customs officers have also become widespread during the war (State Bureau of Investigation of Ukraine 2024).

The high risk of abuse of humanitarian aid resulted in the prompt introduction of legal liability. At the beginning of the war the Criminal Code of Ukraine was supplemented by Article 201-2 “Illegal Use of Humanitarian Aid, Charitable Donations, or Gratuitous Aid with the Purpose of Obtaining Profit”, which enables law enforcement agencies to respond to abuses committed by a significant amount – 350 tax-free minimum incomes (approximately €10,500).

Based on our analysis of data obtained from official reports of law enforcement agencies and the courts, 384 criminal offences as illegal use of humanitarian aid were registered in 2022. In all, 92 persons received official notices on suspicion, and two persons were convicted. During 2023, 189 criminal offences were registered, but only 52 persons received official notices of suspicion, and 21 were convicted. In 2024, there was a slight downward fluctuation: 107 crimes were registered, and 40 persons received official notices on suspicion.

A study of court documents available in the Unified State Register of Court Decisions of Ukraine for the period from 1 May 2022 (the date of the new article of the Criminal Code of Ukraine came into force) to 31 August 2023 revealed information on 22 verdicts using this article, under which 26 people were convicted. It is noteworthy that only one sentence concerned a person who committed a crime as part of an organized crime group, although by its nature and modus operandi such criminal activity is usually carried out in organized forms.

The analysis showed that the risk factors of humanitarian aid trafficking include: the lack of clear guidelines for donors on labelling of aid goods that would be applied throughout the logistics chain and enable tracking of these goods; the lack of regulatory requirements for accounting and reporting on the results of humanitarian aid distribution, as well as proper control over the activities of regional humanitarian headquarters and humanitarian aid distribution points; and the inability to track the distribution of humanitarian aid in “hot spots”, as distribution in areas of active hostilities directly depends on the logistical ability to deliver food, clothing, medicines, etc., as well as on the safety of movement.

Challenges for Counteraction

Counteracting illicit trade, especially its organized forms, has always been problematic given the functionality of the shadow economy in Ukraine against the background of weak social and state formal institutions. The state’s declared policy of unshadowing and combatting corruption has been largely offset by the presence of groups interested in continuing shadow trade, including those in power and the political hierarchy. Along with the high adaptive capability of traffickers who “work” in organized forms and keep up with the latest technologies, law enforcement agencies in Ukraine are mostly associated with inertia.

A comparative analysis of the trends in illicit trade in Ukraine before and after the outbreak of full-scale war shows that the trade has changed significantly, or new ones have emerged. At the same time, the rootedness of illegal practices in the minds of the people and in everyday practice remains almost unchanged. The continuation of typical criminal practices during the war has exposed the systemic problems of Ukrainian society – the lack of real political will to combat organized and white-collar crime, high-level corruption associated with the willingness to knowingly provide and receive illegal benefits despite extraordinary circumstances, lack of transparency in decision-making, and inability of the judicial system to function with integrity and independence.

This entrenched nature of illegal practices, combined with the unrealized inevitability of liability, is one of the biggest challenges for the entire system of combatting crime in Ukraine and illicit trade in particular.

A significant problem is also the lack of institutional provision for counteraction, which has been exacerbated during the war. Since the beginning of the invasion, the issues of national security, protection of territorial integrity and combatting war crimes have come to the forefront of the system of protecting national interests, which is fully reasonable in the context of full-scale armed aggression. In law enforcement agencies, this was reflected in the departure of some employees to the Armed Forces of Ukraine and a shift in priorities to the identification, documentation and investigation of war crimes, patrolling, and neutralizing the aggressor’s sabotage groups in the combat zones.

Amidst constant shelling, the performance of professional duties by the competent authorities is directly linked to the (in)possibility of ensuring personal safety and the need to stay in shelters during numerous air alerts. The destruction or damage to critical infrastructure, including electrical substations, and the lack of electricity make it physically impossible to access the necessary databases and registers, including the Unified Register of Pre-trial Investigations, and to conduct relevant investigative actions, including those requiring technical recording.

Counteracting illicit trade is a holistic, interdisciplinary mechanism and, therefore, requires a strategy that simultaneously addresses all its major functions, including illicit production, transit, and consumption of contraband and counterfeit goods, as well as their enabling and facilitating functions. If one link of this mechanism does not work or works improperly, the effect of integrity and consistency is destroyed (TraCCC 2023).

The most “weak link” in the fight against cross-border illicit trade in Ukraine is the customs service, which, unlike the task of countering the illegal movement of goods, facilitates it. It is impossible to move goods across the border in large volumes without “collaboration” between customs officers and smugglers. During the war, new opportunities for corruption at customs have appeared around the grain corridor within the Black Sea Grain Initiative and in river ports near the Romanian border, which have taken over some of the cargo traffic after the naval blockade. Corrupt practices have also been detected at customs concerning extortion or bribery for the importation of humanitarian aid, in particular, power generators – so needed in Ukraine during attacks on power infrastructure.

Numerous public scandals involving customs officers do not find their logical conclusion in court verdicts. Officer suspected of corruption appeal against their suspension or dismissal and are reinstated. Moreover, journalistic investigations and disclosure of information by MPs based on the results of inspections confirm the direct involvement of top officials (both current and dismissed) in the covering up of illegal schemes at customs and creating extensive criminal and corruption networks at individual customs offices. From a business perspective, customs have been the most corrupt sector for four years in a row (National Agency on Corruption Prevention 2025).

It seems that there are no institutional changes at Ukrainian customs yet, while the current legislative framework is largely sufficient for such changes. Some optimism is inspiring new bills reforming the State Customs Service of Ukraine. On 22 August 2024, the Law of Ukraine “On Amendments to the Customs Code of Ukraine Concerning the Implementation of Certain Provisions of the European Union Customs Code” was adopted (Law of Ukraine 2024a). It will bring Ukraine closer to the EU’s customs legislation. Another bill “On Amendments to the Customs Code of Ukraine Concerning the Establishment of Peculiarities of Service in the Customs Authorities and Certification of Customs Officials” came into force on 31 October 2024 (Law of Ukraine 2024b). It provides for an independent committee to select the new head of the service, audits by external experts, one-time recertification of all customs staff, limited influence of the Minister of Finance, and other changes.

During the war, the work of the newly established Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine in 2021, as the unified body responsible for detecting and investigating economic crimes, was also found to be unsatisfactory. The Bureau was created after lengthy discussions to optimize the criminal justice system, which would eliminate duplication of functions of law enforcement agencies in the area of economic security. Since the outbreak of the war, the Bureau’s priorities have included, among other things, identifying and stopping the activities of those companies engaged in illegal trade with Russia and Belarus. As a result of poor performance and suspicions of political influence, the head of the Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine was dismissed, and the body, although newly created, had to be rebooted in line with Ukraine’s anti-corruption bodies.

The first step was taken by passing the law (Law of Ukraine 2024c), according to which the Economic Security Bureau of Ukraine staff will be recertified, and the head will be elected by a commission consisting of 50% international experts who will have a major predominant vote. The Civil Oversight Council will precisely monitor the Bureau’s activity.

Illicit trade is widely recognized as a transnational criminal activity executed by sophisticated enterprises (Viano Reference Viano1999). However, in 2022, only around 3% of all disclosed organized crime groups had transnational links, and in 2024 – less than 2%. Currently, tackling organized crime is restricted to identifying the lower echelons of criminals. Only those directly responsible perpetrators of the crimes are brought to justice, and they often evade substantial punishment due to certain legal loopholes. It should be noted that over the past 10 years, Ukraine has created a fairly developed legislative and institutional framework for combatting corruption. However, simultaneously, no comprehensive approach to curbing corrupt practices and organized crime has been implemented. The newly created anti-corruption institutions, as well as law enforcement agencies, are not “sharpened” to search for and identify organized criminal networks (Shostko Reference Shostko2024:129).

A significant time lag between the emergence of a specific shadow phenomenon and the legislative response to it, as well as legislative shortcomings in the form of legal conflicts and gaps in the law inherent in Ukraine, remain a criminogenic factor during the war.

For example, at the beginning of the war, all imported goods in the country (including those that did not have the status of humanitarian aid) were exempt from VAT, excise duty and customs duties for the duration of martial law. The so-called zero customs clearance was intended to prevent a shortage in the domestic market in the context of its sharp destabilization as a result of the hostilities. However, an analysis soon showed that a large number of imported goods were not necessities and not essential for the smooth operation of the economy. In particular, premium cars with a customs value of more than UAH 1 million (approximately €24,000) were cleared without paying customs duties (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2022). Such cars were likely to be resale vehicles, which clearly indicated the abuse. Three months after the introduction, these privileges were cancelled, but, by that time, significant losses to the state budget had already been recorded.

These are just some of the problems of counteraction in wartime, the real consequences of which can be comprehensively assessed after the war.

Conclusions

The audacious invasion of Russia in early 2022 and the full-scale war in Ukraine have significantly changed the landscape of both domestic illicit trade in Ukraine and the relevant transnational illicit flows of goods, services and money.

Our study revealed the relationship between the war and illicit trade within the theoretical framework of the concept of structure of illicit trade, distinguishing the types of illicit trade based on the criteria of the legal status of civil circulation of trade items and legal liability for the violation of their production and circulation provided by national law. Such a study can be useful for understanding the development of illegal trade against the background of similar exceptional social crises and is not limited to the scenario identified in the Ukrainian context, given the multifactorial nature of criminal adaptation to new social conditions.

The types of illicit trade selected for the study are not exhaustive for peacetime or wartime. However, they clearly demonstrate how the shadow economy, organized crime and corruption exploit exceptional social circumstances in the short term to generate profits and in the long term to spread influence.

In Ukraine, as an example of a society in ongoing transition, the war did not directly trigger the emergence of large-scale illicit trade, as in such societies, even under standard conditions, the share of the shadow economy is usually quite significant, and corruption and organized crime function as social institutions. However, the war has become a factor of extraordinary institutional and legal changes, which has led to the search for new criminal opportunities in the war economy in the face of the destruction or suspension of usual criminal schemes.

This study highlights the most notable transformations and trends of illicit trade in wartime in Ukraine. They are the following.

Illicit trade dependent on infrastructure and logistics experienced the most devastating impact. In the first weeks of the war, Russian troops carried out massive shelling of aviation infrastructure, primarily airfields, not only for military but also for civilian and military–civilian purposes. Later, railway infrastructure, including power substations, became the target of active attacks. Road infrastructure facilities suffered the greatest destruction, both in absolute and value terms. Closed sea and airspace made the land routes and automobile transport the main means in illicit trade flows.

Transnational illicit trade routes have shifted to bypass Ukraine, while domestic smuggling routes have moved to its western and southwestern borders, as traditional trafficking runs through the occupied territories, and the frontline is constantly moving under active shelling. Mined areas, checkpoints, curfews and enhanced patrolling have significantly reduced the mobility of criminal groups involved in illicit trade. Trade in the grey zone between the government-controlled territories and the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s pseudo-Republics is no longer viable.

At the beginning of the war, illicit trade that fed on the legal economy was seriously affected, as there was a significant economic downturn and considerable restrictions on banking transactions, including currency transfers. At the same time, criminal trade, despite the loss or freezing of its former opportunities, seems to have quickly found new niches. High concentrations of shadow cash and the availability of money laundering have linked the legal and illicit economies, which have begun to function in a manner of communicating vessels.

As the war moved into a protracted phase, the primary disorientation of traffickers turned into the introduction of new schemes, both in the criminal and economic sectors, based on habitual corruption and institutional and psychological readiness for criminal activity in the new environment.

A typical pattern of illicit trade during the war is the involvement of the officials of local military administrations, mayors and other officials having discretion in the competencies and responsibility for making decisions under martial law.

Despite the involvement of organized crime groups in illicit economic activities, some illicit markets (for example, smuggling of conscripts as a trade in illegal services) are not hierarchical. Schemes sometimes emerge sporadically and locally, but after successful approbation, they become clichés and are entrenched as criminal practices.

Illicit trade in wartime, regardless of additional transaction costs and security risks, has remained profitable. Some of its segments perform a compensatory function – providing medicines, petrol (oil products), military ammunition, etc. – when the state cannot cope with domestic demand and operational needs.

Although the availability of heroin in Ukraine appears to have decreased since the full-scale invasion, the production and use of synthetic drugs have been less affected. The importation of precursors has increased, and production centres for synthetic drugs have moved closer to frontline regions.

Compared to the decline of the legal market of cigarettes and alcohol, the illicit market of these products has not decreased accordingly.

Trade in humanitarian aid and smuggling of conscripts became new considerable war-related illicit markets. However, in perspective, these illicit markets are short term, and, with the end of the war, the risks are expected to decrease.

The expected risks of large-scale traditional trafficking in human beings by organized crime groups, which often accompany armed conflicts and wars, have not been realized so far or at least have not been empirically confirmed in the context of the war in Ukraine. At the same time, a new slavery market directly related to the war appeared in occupied territories out of the policy of the aggressor state and the vulnerability of Ukrainian citizens having residence in these territories. Forced deporting to Russia and acquiring Russian passports, forced labour and forced mobilization into military actions are the manifests of exploitation.

It is expected that as the war continues, the risks of establishing new transnational links of organized illicit trade, which has largely been refocused since the beginning of the war from Russia to Western Europe, and the export of criminal practices with the flow of Ukrainian refugees are likely to increase resulting in the imposition of an additional burden on law enforcement agencies in involved states, especially those neighbouring Ukraine.

Despite the significant efforts made to reform Ukrainian customs, the complete failure of customs and the consequent spread of smuggling remain the most serious institutional problem and an impediment to Ukraine’s desire to join the EU.