IntroductionFootnote 1

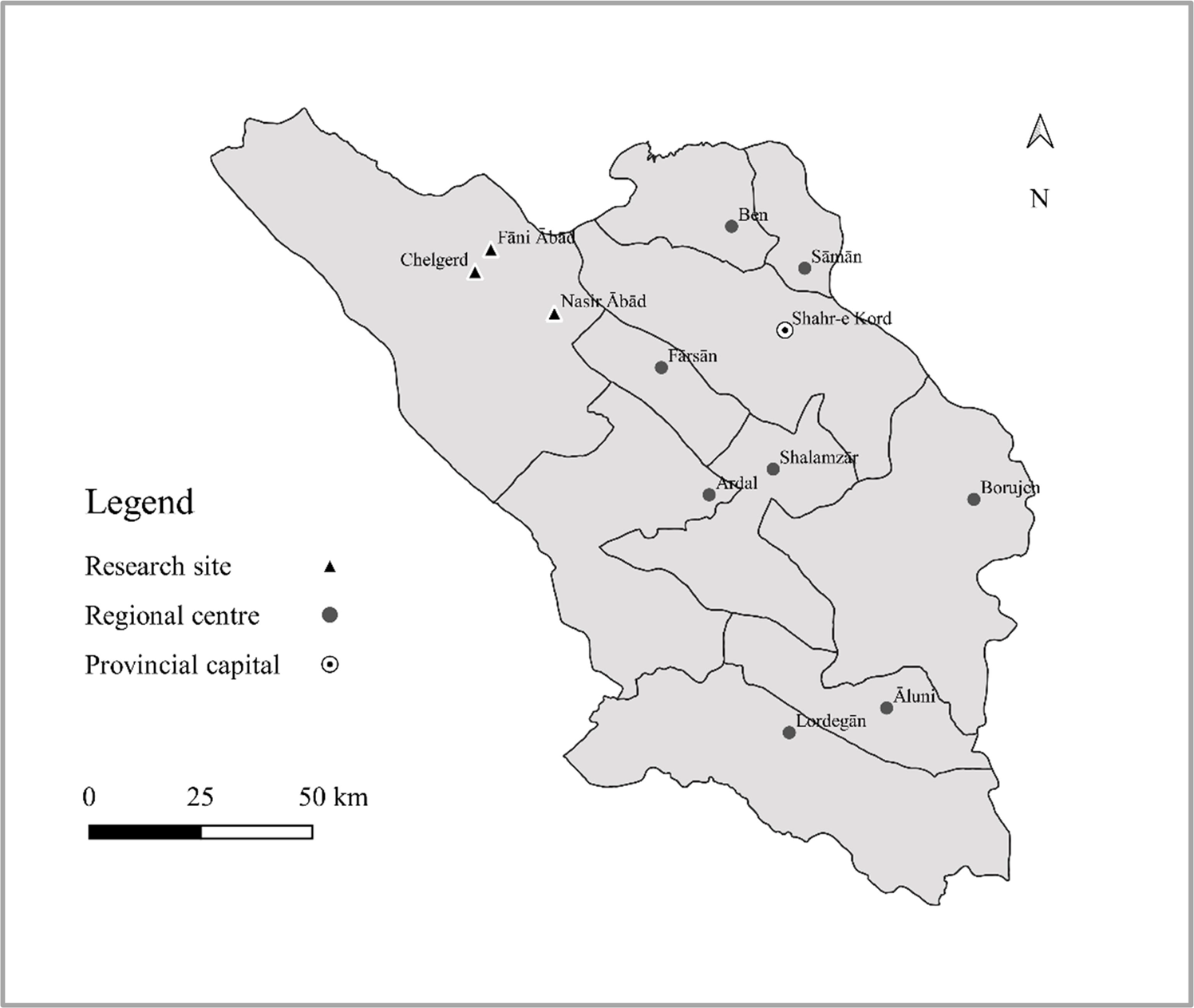

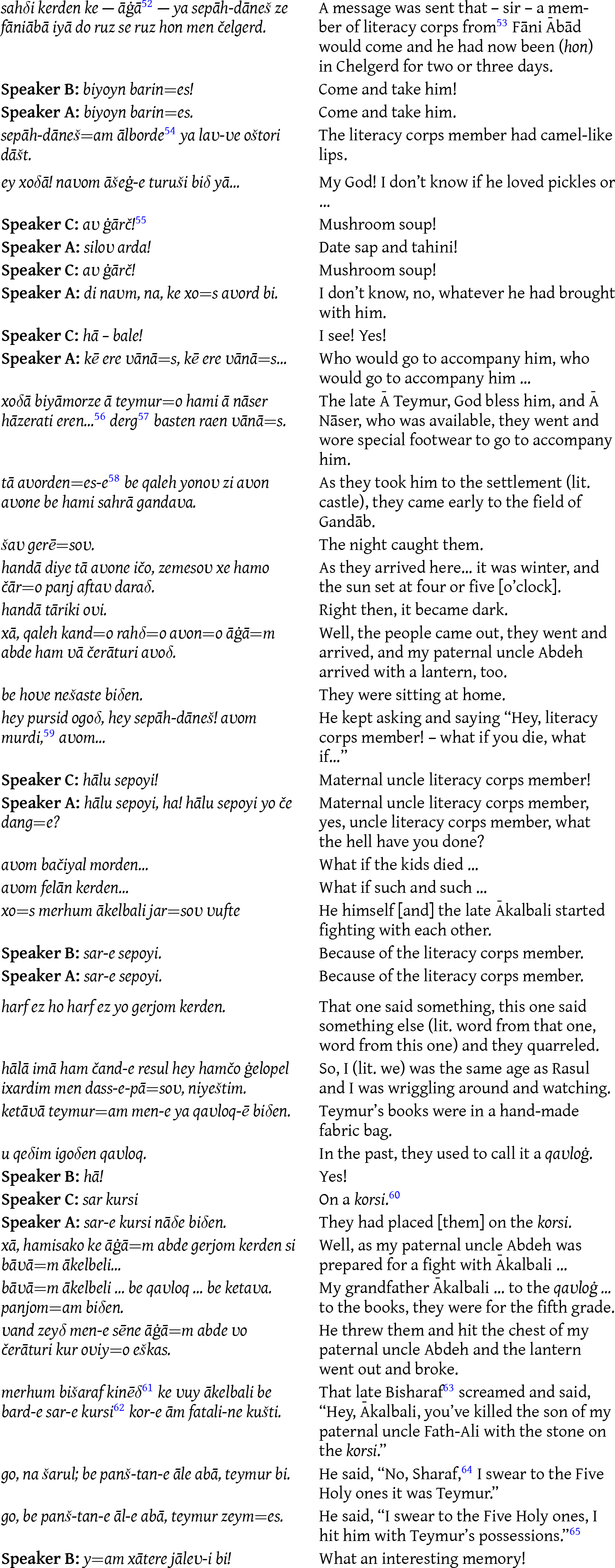

The Zagros Mountains of southwest Iran, and the foothills to both sides, are the domain of the Bakhtiari tribe (B. ēl, P. il). Their homeland spans parts of several provinces of Iran: Khuzestan, with Masjed Soleymān and Izeh as major centers; Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari (henceforth C&B), where Kuhrang and Ardal have been historically important; the eastern third of Lorestan Province, where the Bakhtiari cities of Aligudarz, Aznā, and Dorud are located; and smaller parts of Isfahan and Markazi provinces (Figure 1). Moreover, a considerable portion of Bakhtiari people have migrated to the major cities in the western part of Isfahan Province over the past several years. Numbering over one million people,Footnote 2 the Bakhtiari are a well-organized sociopolitical confederation divided into two main branches, the Haflang (P. haft lang) and Chārlang (P. čahār lang), each of which is hierarchically divided into different parts (bāb or boluk).Footnote 3 At the heart of the Bakhtiari homeland, the district of Kuhrang in C&B Province is dominated by the Haflang, among whom the Bavadi (autonym: bāʋāδi; P. bābādi) are one of the largest bāb.

Figure 1. The Bakhtiari homeland and language area (based on Anonby and Asadi, 2018: 22)

This paper explores the Bakhtiari dialect of the Bavadi within its social and cultural context. The study opens with an account of our approach to the research, and a description of the Bavadi people in society and history. A précis of research on the wider Bakhtiari language, from the earliest work until the present, frames our investigation into the Bavadi dialect. The core of the paper consists of a grammatical description, focusing on salient aspects of phonology and morphosyntax. This description is based on our analysis of collected oral texts and complemented by a representative set of lexical and grammatical data elicited using the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI) language data questionnaire.Footnote 4 Along with the better known and described genre of the folktale, we include two texts of a basic type, which, although arguably the most common use of spoken language, rarely features in descriptions of Iranian languages: free conversation among several speakers.

Documentation

Our field research was conducted in the provincial sub-district (šahrestān) of Kuhrang, in the northwest quarter of C&B Province, in late September 2017. We visited three places: Fāni Ābād, home to 43 families and a population of 157; Nasir Ābād, home to 241 families and a population of 885; and the town of Chelgerd, the capital of Kuhrang, home to 753 families and 2,989 individuals.Footnote 5 Figure 2 depicts the research sites.

Figure 2. Research sites for this study, located in C&B Province. Map by Mortaza Taheri-Ardali, 2022.

This research was conducted in the context of an ethnographic expedition organized by Dr. Mohammad Hakim-Azar, professor at the Islamic Azad University of Shahrekord, in conjunction with the local governor Mr. Ali Badri in Kuhrang. After twenty minutes travelling uphill from Shahrekord toward the northwest, we entered “the land of the Bakhtiari” (B. xāk-e baxtiyāri), an informal designation for an area of roughly 75,000 km2 stretching across the Zagros range all the way to the outskirts of Dezful, Shushtar, and Rām Hormoz in Khuzestan.Footnote 6 We passed through about a dozen villages on the way to Chelgerd, itself the seat of Kuhrang šahrestān, at the source of the Zāyandeh Rud River. Bakhtiari carpets, alpine honey, wild celery, mountain leek, dairy products, and natural salt are some of the renowned souvenirs of this region. Surprisingly, despite the cold climate, the Salt Valley (B. dare neʋek, P. darre namak), as shown in Figure 3, is a well-known place close to Chelgerd, which produces natural salt.

Figure 3. The Salt Valley, a source of natural salt near Chelgerd. Source: Photo © Mortaza Taheri-Ardali 2021.

Chelgerd is an attractive town, set in a valley bounded by mountains. For centuries, it has functioned as an economic hub (along with Ardal, Izeh, Lāli, Gotvand, and Masjed Soleymān) supplying nomads with goods.Footnote 7 In Chelgerd, we walked along the main street, lined by rows of shops selling locally produced Bakhtiari goods. Nowadays, while still a center that supplies the nomads and adjacent villages, the town’s economy revolves more around tourism, which thrives year-round, attracting holiday-makers from Isfahan, Khuzestan, and the rest of the nation. The Kuhrang tunnel spillway (P. ābšār-e tunel-e kuhrang) is one of the main tourist attractions in the area, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The town of Chelgerd as seen from the top of the Kuhrang tunnel spillway (P. ābšār-e tunel-e kuhrang). Source: Photo © Mortaza Taheri-Ardali 2017.

In Fāni Ābād and Nasir Ābād, we were welcomed by men in typical Bakhtiari clothing, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6: the tall rounded felt hat (B. kolah xosraʋi, P. kolāh-e xosraʋi), a straight, knee-length, sleeveless tunic of natural white wool with vertical indigo stripes (B. čuqā, P. čuġā), and wide, black pants (B. šaʋlār dabit, P. šalʋār-e dabit).Footnote 8 Houses (tu) made of stone, mud, and mud bricks are still typical in these villages. We found no traditional black goat-hair tents (B. bohoʋn, P. siyāh čādor), but we still saw the occasional flock of sheep and goats on the mountainside pastures.Footnote 9

Figure 5. Conducting fieldwork with Bakhtiari people wearing traditional clothes in Nasir Ābād. Source: Photo © Mortaza Taheri-Ardali 2017.

Figure 6. Conducting fieldwork with Bakhtiari people wearing traditional clothes in Fāni Ābād. Source: Photo © Mortaza Taheri-Ardali 2017.

The settlements’ names (e.g., mostly with the suffix -ābād) in the region nearby are relatively recent formations. Large-scale sedentarization of the nomads – forced upon the Bakhtiari by the shahs of the 20th century and continuing for economic reasons today – has deeply altered the tribes’ livelihood and lifestyle. Needless to say, schooling, media, and extensive contact with larger Persian-speaking cities have affected the linguistic structures of Bakhtiari in this region.Footnote 10 However, according to our observations, among those who have retained a nomadic lifestyle, the original Bakhtiari structures are more intact.

In contrast to many areas of Iran, where villages have been emptied of young people, the villages we visited in Kuhrang were vibrant. The inhabitants were from all age groups, and many families had highly educated members working in the cities of Isfahan and Khuzestan Provinces as professionals.

The Bavadi

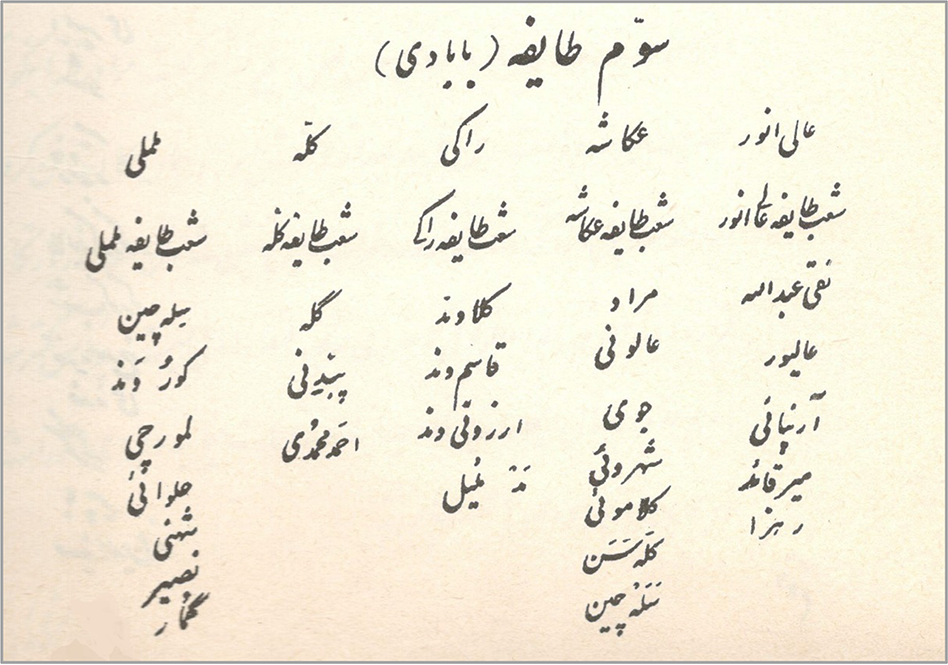

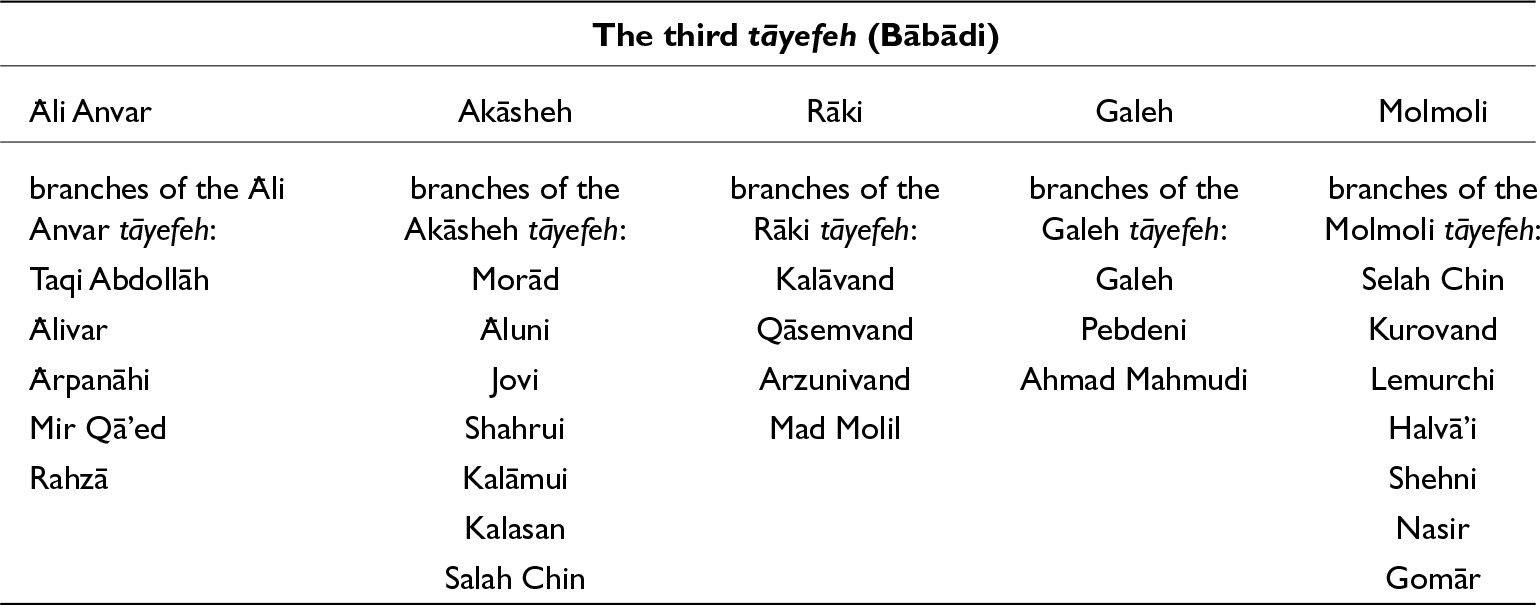

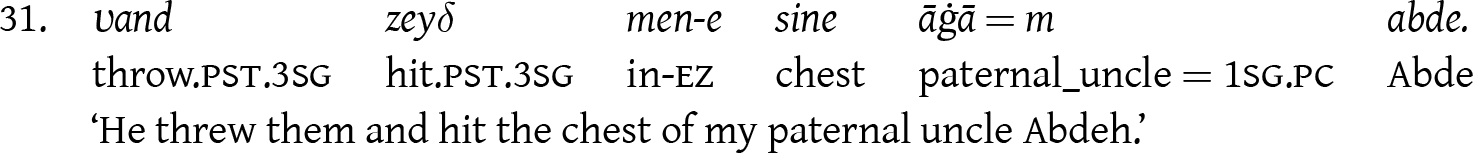

Bakhtiari is renowned for its numerous hierarchical and interlocked tribal units, reflecting a substantial degree of lineal segmentation at different levels.Footnote 11 Accordingly, the tribe is comprised of two main divisions (šāxe), Haflang and Chārlang, each with its own distinctive linguistic features that are defined both socially and areally. After šāxe, from largest to smallest, bāʋ, tāefe, tire, taš, korebaʋ, bohoʋn, and māl are considered as various levels in this highly organized ethnic group. In response to the question of če kasi? (who are you?), most Bakhtiari people are able to provide their lineage. Nevertheless, the groupings and labels vary in the literature as well as among the Bakhtiari population itself. Bavadi, as the primary focus of this research, is among the largest bābs in Haflang. Most Bavadi have their base in Chelgerd and neighboring villages, as well as in Masjed Soleymān, Izeh, and other cities in C&B and Khuzestan provinces. According to Ali Qoli Khān Bakhtiari Sardār As’ad (1361/1982), the seminal reference in this regard, Figure 7 and the corresponding Table 1 depict the internal organization of Bavadi.

Figure 7. Internal organization of the Bavadi (Bakhtiari Sardār As’ad, 1361/1982: 534)

Table 1. Transliteration/translation of Figure 7

The Bavadi speak a dialect of Bakhtiari, a language grouping classified as Southwestern within the Iranian family.Footnote 12 More specifically, this language belongs to the Lori continuum in which three main high-level varieties have been identified: Northern Lori, Bakhtiari, and Southern Lori.Footnote 13 As regards Persian within Southwestern Iranian, present-day Persian is a sister – rather than a parent – to varieties such as the Lori group, Lārestāni, Bandari, Kumzari,Footnote 14 Bashkardi, Sistani,Footnote 15 the Fārs group,Footnote 16 and Garmsiri.Footnote 17

With respect to other Bakhtiari varieties, Bavadi shows both similarities and differences in lexicon, phonology, and morphosyntax. As the intention here is to show differences with Persian, diachrony is integrated into this grammatical description.

Literature review

Well over a century ago, pioneering orientalists showed interest in the Bakhtiari language. In 1910, Oskar Mann made general remarks on Bakhtiari based on some texts, as part of a larger work in the Lori language domain.Footnote 18 Valentin Zhukovskij’s extensive collection of Bakhtiari songs and poetry was published posthumously in 1922.Footnote 19 This was followed by the work of another Russian linguist, Y.N. Marr, who published short specimens of Bakhtiari literature.Footnote 20 A lion’s share of early Bakhtiari documentation was carried out by the British Iranist and military officer David L.R. Lorimer (1876–1962), who published his wide-ranging collection of Bakhtiari texts with meticulous philological analyses in 1922; further unpublished materials from his collection have been made available by Vahman and Asatrian.Footnote 21 While the geographic provenance of earlier works on Bakhtiari was unclear, Lorimer’s publications indicated that his data was chiefly from Masjed Soleymān in Khuzestan. This is where he served as a British officer.

After a long hiatus, the study of Bakhtiari was continued, this time within modern linguistic frameworks, through three sketch grammars in the context of overviews of the larger Lori group: Kerimova, Windfuhr, and MacKinnon.Footnote 22 All these studies rely heavily on Lorimer’s data. In addition, Lecoq provided a very brief overview of Bakhtiari linguistic structures in the benchmark volume Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum in 1989.Footnote 23 In contrast, the wide-ranging Bakhtiari Studies: Phonology, Text, Lexicon by Anonby and Asadi (2014) is based on a substantial new dataset from a Haflang dialect in the area of Masjed Soleymān in Khuzestan.Footnote 24 In a companion volume, Anonby and Asadi elaborate a systematic orthography for Bakhtiari built on the phonological analysis of the first volume.Footnote 25 Up to that point, almost all studies had been based on the varieties of Bakhtiari spoken in Khuzestan. Anonby and Taheri-Ardali brought together previous research through a global overview of the language and, while their main focus was on Bakhtiari of Masjed Soleymān, they also included a glossed text from Bakhtiari of Ardal in C&B Province.Footnote 26

Persian-language publications about Bakhtiari include, but are not limited to, the collections of poems, proverbs, idioms, riddles, folk tales, and glossaries by writers such as Davari, Afsar Bakhtiari, Salehi, Abdollahi Mowgu’i, Kiani Haft Lang, Madadi, Ra’isi, Sarlak, Foroutan, Khosravinia, and Ghanbari Odivi, among others.Footnote 27 So far, materials published on Bakhtiari are primarily of the Bakhtiari varieties of Khuzestan.

Since the establishment of linguistics departments at various Iranian academic institutions in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the above-mentioned works have been followed by descriptions of the linguistic structures mostly in the form of master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, books, and articles. The following linguistic works on Bakhtiari are worth mentioning: Alizadeh Gelsefidi, Eidy, Khosravi, Zolfaghari, Taheri, Rezai and Amani-Babadi, Taheri-Ardali, Aliyari Babolghani, Rezai and Shojaee, Talebi-Dastenaei and Ghatreh, Atashabparvar, Sadeghi, and Taheri-Ardali, Anonby, and Zaheri-Abdevand, among others.Footnote 28

The Bakhtiari varieties of C&B Province are currently studied in the framework of the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI) research program, and a number of related articles have been published.Footnote 29 Taheri’s Guyesh-e bakhtiāri-ye kuhrang, Anonby and Asadi’s Bakhtiari Studies: Phonology, Text, Lexicon, and Anonby and Taheri-Ardali’s book chapter “Bakhtiari” are the most relevant studies to the current research. Therefore, they are mentioned in different sections of the article below.

Grammatical outline

In this section, we provide an outline of the linguistic system of Bavadi Bakhtiari. While our presentation of the system is framed by phonological and morphological paradigms, the description of syntax in particular draws heavily from the texts that follow.

Phonology: vowels

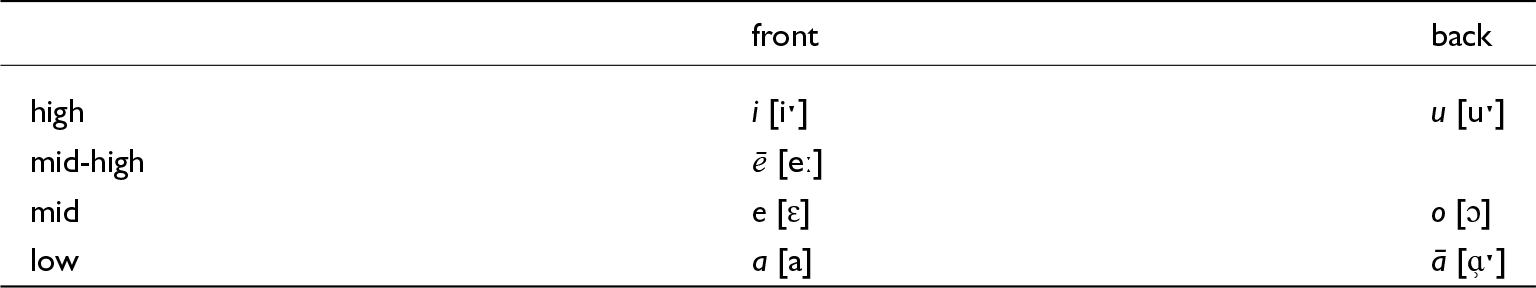

Across the Bakhtiari-speaking area, there is significant variation in the vowel inventories. In the areas where Bakhtiari has been in close contact with Persian varieties, the vowel system tends to pattern with Persian.Footnote 30 The Bakhtiari dialect in question, Bavadi, is a typical of the language and can be considered its prototype in the region. According to our data, Bavadi Bakhtiari displays a basic inventory of seven simple vowels i ē e a ā o u, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Vowel phonemes

All of the vowels occur in both open and closed syllables, for example, di “smoke,” liš “ugly,” hird “small,” ču “wood,” mur “ant,” gušt “meat,” tē “eye,” šēr “lion,” bepēčn “wrap,” se “three,” mel “hair,” lešk “branch of a tree,” to “you” (sg.), qol “boiling,” hošk “dry,” na “no,” pas “behind,” darf “dish,” dā “mother,” pār “last year,” and ʋāst “wait.”

The vowel ē is a mid-high, front unrounded vowel, which occurs in all syllable positions in the data, as in ēl “tribe,” ēleʋār “jaw,” mēre “husband, man,” sēste “hawthorn,” mēš “ewe,” and botē “maternal aunt.” Minimal sets include bēδ “willow tree” vs. biδ “be.pst”; sšēr “lion” vs. sšer “a short while”; čēl “mouth’” vs. čel “arm”; and sēr “full” vs. sir “wild garlic, garlic.” Bavadi speakers we consulted make a clear distinction between dēr “late, long,” and dir “far” (cf. P. dir and dur, respectively). Furthermore, they also distinguish between ē and the segment ey (see below), e.g., tē “eye” vs. tey “before.” In light of the evidence provided here, we posit that ē is a separate phoneme in Bavadi. This differs from the system in the Masjed Soleymān dialect of Bakhtiari, for which Anonby and Asadi analyze historical ē as a vowel-glide sequence ey rather than a unitary mid-high vowel ē. In line with Taheri, however, our data shows ē as a separate phoneme in Bavadi.

It is not uncommon in Bakhtiari to witness the occurrence of underlying h after the vowels a, e, and o within a coda. However, typically h is realized in this position as the length on the preceding vowel and loses its consonantal pronunciation, e.g., kah k[aː], “chaff,” peh p[ɛː] “fat (n.),” mahde/mehde m[aː]δe/m[ɛː]δe “stomach,” and koh k[oː] “mountain.”Footnote 31 In all these cases, there is no phonological contrast between the form with the lengthened vowel and the form with no lengthening, including the vowel [ɛː]. In other words, despite the fact that the articulation with the phonetic long vowel in the above-mentioned cases is phonetically more usual, there is no minimal pair available to show the contrast between the long and short forms. That said, the phoneme ē [eː] has a phonetic quality that differs from that of eh [ɛː], as mentioned in the examples above. In spite of this, the occurrence of ē in the younger generations, whose language is directly influenced by Persian, is unstable and sometimes merges with the typical high back vowel i. We cannot establish a parallel underlying distinction between [oː] and [ɔ] in Bavadi, similar to the findings of Anonby and Asadi and Anonby and Taheri-Ardali.Footnote 32 The former, i.e., [oː], occurs rarely and speakers do not distinguish the two sounds perceptually. As a case in point, the second vowel in kolo k[ɔ]l[oː] “locust,” when pronounced in isolation, is significantly longer than the first vowel, but this extra lengthening is based on the utterance-final position and is not phonemically distinctive. In other cases where a phonetically long “o” is heard, such as in pohδ [phoːð̞] “cooked,” lohδ [loːð̞] “naked,” sohδ [soːð̞] “burned,” sohr [soːɾ] “red,” and gahp [gaːp] “big,” there is an underlying h in the coda. This alternation – realization of h in codas as length on the preceding vowel – is prevalent in Bakhtiari, as discussed above. Our finding on this matter is in contrast with Taheri (1389/2010), who considers the long mid vowel ō as a separate phoneme in Bakhtiari of Kuhrang. Overall, as in Middle and Early New Persian, the Bakhtiari variety under investigation has retained the long mid vowel ē. However, the present-day Bavadi Bakhtiari, like Persian and many other Southwestern languages, has lost historical ō as a separate phoneme.

Nasalized vowels are evident in Bavadi, but are not phonemically contrastive. Underlyingly, they can be considered vowel-ʋ sequences, for which the sequence oʋ is the most probable interpretation, such as in hoʋe [hõw̃ɛ] “house,” šoʋe [ʃõw̃ɛ] “comb, shoulder,” and zoʋ [zõːu] “tongue.”

Following Anonby and Asadi (2014), our data shows that vowel sequences in Bavadi are more widely available and varied than those in Persian. Nevertheless, in urban areas and areas where Bakhtiari is under the direct influence of Persian, the vowels are produced more like Persian simple vowels than Bakhtiari vowel-glide sequences. Noted vowel-glide sequences in our data, as already observed by Anonby and Asadi (2014), are ey (tey “before,” seyl “flood”), ay (say “dog,” ay “if”), āy (pāy “clean, all,” sarʋālāy “steep,” fāyδe “profit”), oʋ (hendoʋe “watermelon”, siloʋ “date sap,” yonoʋ “these”), aʋ (laʋ “lip,” aʋ “water,” aftaʋ “sun”), and oy (poy “clean,” goy “you said,” toyniden “to toss”).

There are some phonetic differences between Bavadi Bakhtiari and Modern Persian in the remaining vowel sounds, especially in the back low vowel ā [ɑ̹ˑ], which is slightly more rounded than its Iranian Persian counterpart. In the transcribed texts (see below), instability among oʋ~un~uʋ can be seen in a few items: pā=soʋ “their feet,” zāniyun “(place name),” ġorbatun “the blacksmiths,” ya meyδuʋ-ē “a circle,” xomun “ourselves,” čārtā=sun “four of them,” gahp=moʋ “our leader,” and ramezoʋ “(man’s name).” This suggests that a transitional situation exists, variably capitulating to the pronunciation of their colloquial Persian counterparts: -un, -sun, and -mun, as in meydun “circle,” čārtā=sun “four of them,” and bozorg=emun “our leader,” respectively. In a comparable manner, the impact of Persian at the lexical and morphological level is also evident, as other examples of instability are discernible, such as in the words kuče “alley” and mēdoʋ “s/he knew” (cf. the expected Bavadi forms kiče and edoʋe, respectively), which are produced similarly to their Persian structures in the data.

Vowel diachrony

In examining the vowel diachrony of Bavadi, several noteworthy developments distinguish its vowel system from that of Persian. This subsection focuses on the phonological changes affecting original high back vowel *ū and low back vowel *ā, as well as the influence of pharyngeals on vowel coloration.

An original high back vowel *ū is fronted, most often in a pre-coronal position (cf. mi “hair”), as in pil “money,” andirin “abdomen,” tit “mulberry,” pine “pennyroyal” (flower sp.), and hin “blood.” The original low back vowel (*ā) generally remains, e.g., in hāga “egg” and bāyi “arm,” but is raised and rounded in historical pre-nasal context, as in zamoʋ “time, era,” heyʋoʋ “animal,” and šom “evening.” The vowel *ā is fronted before h, as in kolah “hat,” mah “moon,” and šah “black,” but not in sšāh “king,” an item typically used in Persian-sensitive registers of the language.

The coloration of vowels influenced by pharyngeals in Bavadi exhibits several notable reflexes. Syllable-final iʕ becomes ah in words like mahδe “stomach” (< Ar. miʕda). Cross-syllabic aʕ and aḥ are reflected as ā in words such as mālam “teacher” (< Ar. muʕallim), māhāl (< Ar. maḥāl, meaning “places,” as seen in the toponym čār māhāl “Chahar Mahal”), amārat (otherwise emārat in Persian < Ar. ʕimārat, meaning “building”), and sehāʋ (< Ar. ṣāḥib, meaning “owner”).Footnote 33

Phonology: consonants

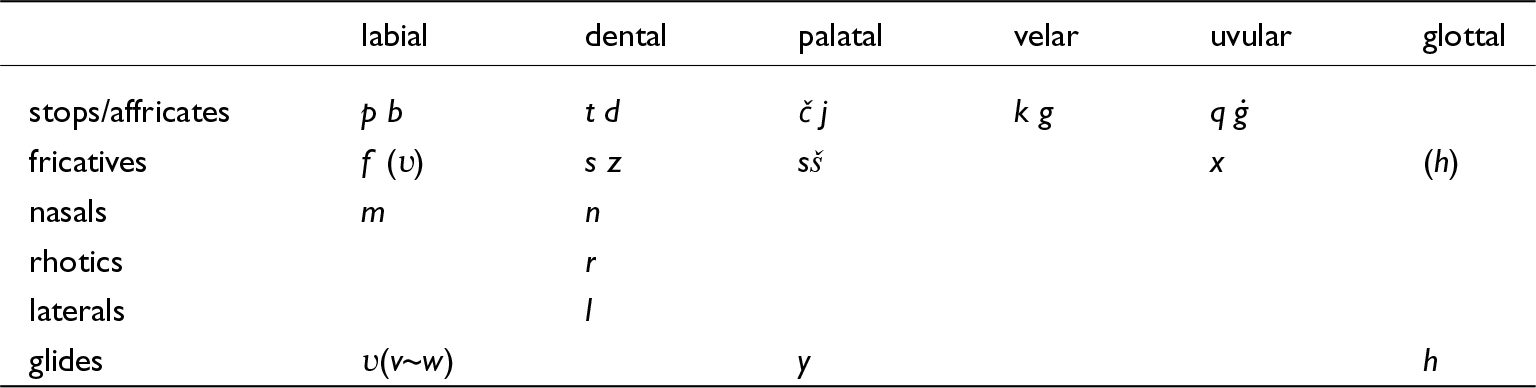

The consonant inventory of Bavadi is detailed in Table 3. This inventory includes a range of consonantal sounds that highlight the influence of historical and regional linguistic developments to Bavadi Bakhtiari.

Table 3. Consonants. The pairs of consonants are voiced and voiceless respectively

In Bakhtiari, the phoneme d is pronounced as [d] in word-initial positions (e.g., di “else”) and in final positions following non-glide consonants such as nd in jend “jinn” and rd in dard “pain.” It also occurs in clusters before a vowel, as in gajdin “scorpion” and abde, a proper name. In addition, d is sometimes realized as [ð̞], particularly in postvocalic positions, such as in doδar “girl, daughter,” diδi “you saw,” fešnāδen “to send,” and bāʋāδi “Bavadi.” The allophone [ð̞] also appears after the glides ʋ, y, and h, as in eyδ “Eid,” meyδun “plaza,” ezeyδ “he was hitting,” zeyδom “I hit,” ezeyδen “they were hitting,” esteyδom “I grabbed,” and in hδ as found in sohδ “it burned,” lohd “naked,” and sohδen “to burn.” This variation supports analyzing [ð̞] as an allophone of d in Bakhtiari. For clarity, we use the symbol δ or “Zagros d” in our transcription to reflect this phonological trait, which distinguishes Bakhtiari from Persian. However, we do not intend to imply that δ is a separate phoneme in the Bakhtiari dialect studied.

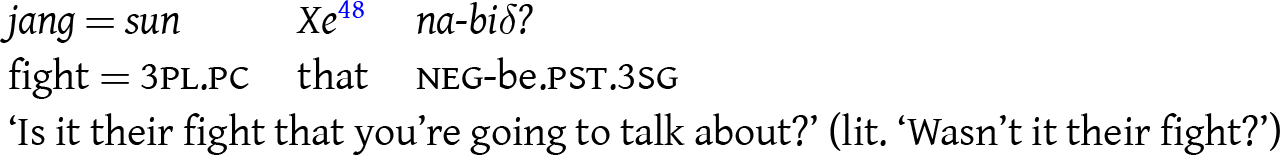

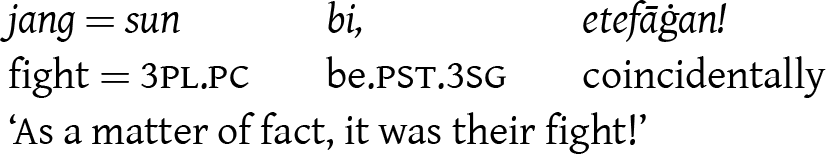

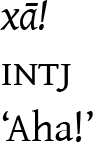

Bavadi Bakhtiari has the uvular consonants, i.e., voiced plosive ġ and voiceless plosive q as two separate phonemes.Footnote 34 The consonant q has frequent occurrences in the data, including qaleh “castle,” qarā “sour whey,” qāli “carpet,” qarz “loan,” qeδim “long past,” qaʋr “grave,” qoyum “hard,” qaʋl “promise,” qaʋloq “fabric hand-made bag,” maqāš “tongs,” qahr “wrath,” qoroʋ “Qur’an,” āqel “wise,” qāter “mule,” and qoδu “foal.” Examples for the consonant ġ are as follows: ġār “cave,” ruġen “ghee,” ġorbatoʋ “blacksmiths,” šuluġ “crowded,” and jeġele “a child boy,” and also include words spelled with ق <q> in Persian orthography, such as ġāšoġ “spoon,” āġā “dad,” ġašang “pretty,” and ġārč “mushroom.” The following examples with ġ prove that it is not etymological: ġalb “heart” (< qalb), ġaʋz “joy” (< zawq), feġat “only” (< faqat), aġaʋ “behind” (< ʕaqib), rafiġ “friend” āšeġ “in love” (< ʕāshiq), hayġat “truth” (< haqiqat), etfāġan “accidentally” (< ettefāqan).Footnote 35

The minimal pairs are ġor “bell” vs. qor “throat,” ġil “pitch” vs. qil “deep,” and qol “boiling” vs. ġol in ye ġol do ġol “a local game played with stone.” In addition, there are a couple of near minimal pairs that show that these two are separate phonological consonants in Bavadi. To name a few: qoroʋ “Qur’an” vs. ġorbatoʋ “blacksmiths,” qāli “carpet” vs. ġāšoġ “spoon,” ġaʋz “joy” vs. qaʋloq “fabric hand-made bag.” This accords with the analysis of Anonby and Asadi (2014) but in contradiction with Taheri (2010), in which a single phoneme is proposed for both the voiced and voiceless uvular stops in Bakhtiari of Kuhrang.

In the Bavadi data, the segment [ʒ] occurs only in a few words and only as a dissimilated form of the phoneme j when it occurs as the first segment in a word-internal cluster. Examples include gajdin “scorpion,” hijdah “eighteen,” and majma “large tray.” Hence, in contrast with Bakhtiari of Masjed Soleymān, we do not qualify ž as a separate phoneme in Bavadi.Footnote 36

The phoneme ʋ has an allophonic range among [v], [ʋ], and [w].Footnote 37 Examples are as follows: [v]orzā “bull,” se[v]ēl “mustache,” do[ʋ~w]ā “groom, son-in-law,” bā[ʋ~w]ā “father,” a[ʋ~w]oδ “he came,” and a[ʋ~w]om “I came.” Moreover, ʋ forms diphthong-like sounds, most frequently aʋ, as in aʋ “water,” raʋ “go,” daʋ “playfield,” haʋ “scream,” šaʋ “night,” šaʋlār “trousers,” raʋraʋ “ligament,” aʋlāδ “children,” daʋr “around,” qaʋl “promise,” yonoʋ “these,” siloʋ “date sap,” etc. As a vowel-glide sequence, we find the plural morpheme -oʋ, e.g., široʋ “lions” and plural enclitic pronouns -moʋ, -toʋ, and -soʋ.

Following Anonby and Asadi (2014) and Anonby and Taheri-Ardali (2018), the glottal stop, which behaves like a glide in many languages, is not phonemic in Bavadi Bakhtiari.Footnote 38

Consonant diachrony

The following historical sound changes are observed in Bavadi but not Persian, helping to reduce Bavadi’s intelligibility to native Persian speakers, even when cognate lexical items are used.

Original nasals shift to ʋ in intervocalic positions, e.g., doʋa “groom, son-in-law” (cf. P. dāmād), hoʋe “house” (P. xāne), joʋe “shirt” (P. jāme), aʋo(δ) “he came,” (P. āmad), hendoʋe “watermelon” (P. hendaʋāne), zoʋi, zuʋi “knee” (P. zānu), ramezoʋ “(man’s name).” This rule applies to newly borrowed words only in final position, e.g., telefoʋ “telephone.”

*The change *š > s in isā ‘you’ (cf. Persian šomā) and in the third-person pronominal clitics, singular =s and plural =soʋ, are attested in the data.

*d softens after vowels and glides in the following ways: it becomes the interdental approximant δ, as in šāδ “happy,” esbiδ “white,” seδā “voice,” zeyδ “hit.pst.3sg”; changes to y, as in keyʋenu “lady” (P. kadbānu) and biy-om “I was”; or is lost altogether, as in zi “soon,” doʋɑ “groom, son-in-law,” and xo =s “him/herself.”

Other stops also weaken or disappear postvocalically: -*b- > ʋ or is lost entirely, as in ču “wood,” zoʋ “tongue,” ruʋā “fox,” soʋah “tomorrow,” keyʋenu “lady” (P. kadbānu), aʋ “water,” and šaʋ “night”; and -*g-, -*k- > y, as in say “dog,” jiyar “liver,” zendeyi “life,” poy/pāy “clean, all” (cf. P. pāk), and doyδor “doctor.”

*x tends to weaken in certain contexts. Initial *x- > h in some words, such as hin, xin “blood,” hošk “dry,” hāga “egg,” hiz “jump, attack” (P. xiz), and har “donkey,” but not in xoʋsiδ “sleep.pst” and xeriδ “buy.pst.” The cluster -xr- > hr in tahl “bitter” and sohr “red.” Medial -xt- weakens in doδar “girl” and sohδen “to burn,” but not in deraxt “tree” and baxtiyāri “Bakhtiari.”

Medial *-ft- is subject to becoming weak in gom “I said” and ra(h)δim “we went,” but not in čaft “knee-pit,” aftaʋ “sun,” roftan “to sweep,” and ʋufte “it fell” (P. oftād).

Morphosyntax: noun phrase

Nouns may take the following suffixes and clitics: plural markers -oʋ, -ā, yal/-gal; definite marker -(ek)e; indefinite marker -i, -(e)y; object marker =(n)e; ezafe linker -e; pronominal clitics =om “1sg.pc,” =et “2sg.pc,” =es “3sg.pc,” etc.; conjunctive =o/=yo/=ʋo “and”; particle =am “also”; and copulas =(o)m, =i, =ya, etc.

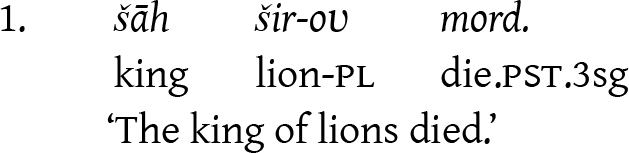

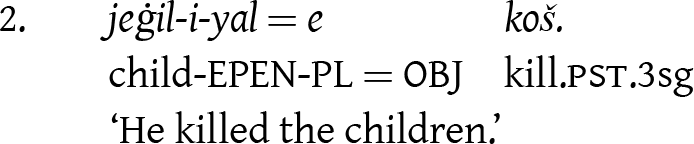

Number

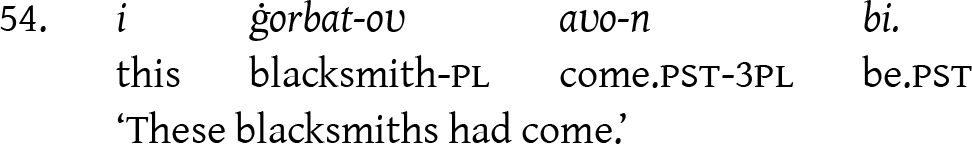

There are three plural markers, all stressed: -(h/ʋ/y)ā, -oʋ, and -yal/-gal.Footnote 39 A few examples include: ketāʋā “books,” hoʋehā “houses,” gerduʋā “walnuts,” baxtiyāriyā “Bakhtiari people,” široʋ “lions,” loroʋ “Lors,” ġorbatoʋ “blacksmiths,” jeġeliyal “children,” zangal “women,” and bozgal “goats.” In addition, the following sentences are taken from the transcribed texts:

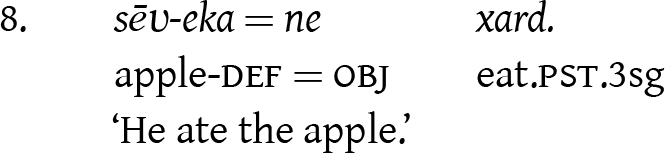

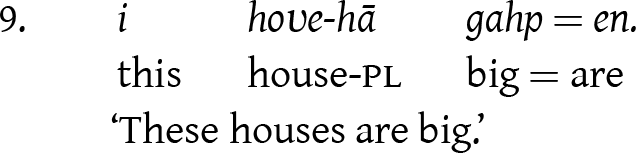

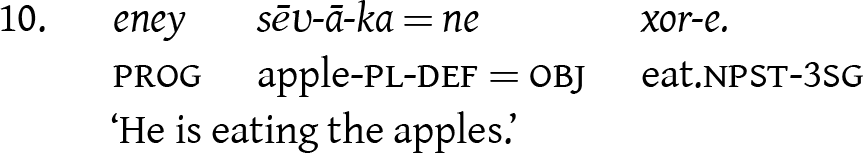

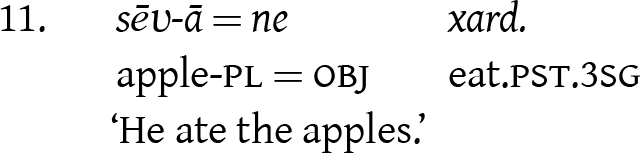

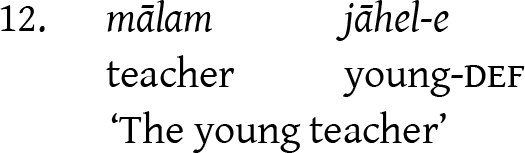

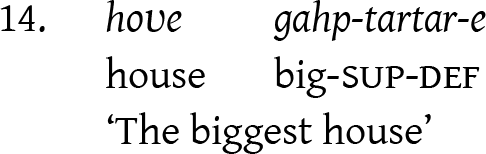

Definite marker

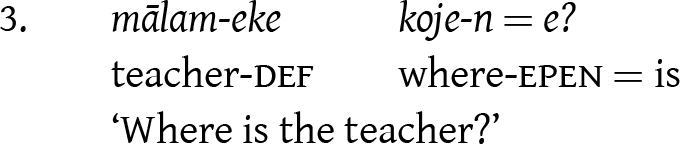

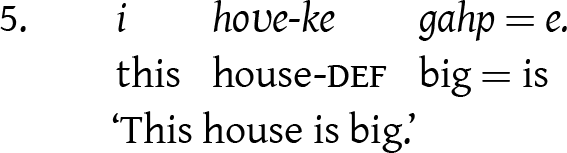

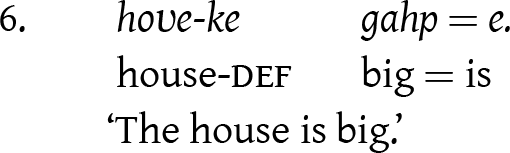

In Bakhtiari, the definite marker is typically expressed as the stressed -e, with an allomorphic variant -(e)ke/(e)ka.Footnote 40 The choice between -e and -(e)ke/(e)ka depends on discoursal factors, with -(e)ke/(e)ka often used for emphasis or in specific syntactic environments. For example, in mālam-eke koje-n=e? “Where is the teacher?” (example 3), the definite marker -eke emphasizes the definiteness of “teacher,” while in mālam-e koje-n=e? “Where is the teacher?” (example 4), the simpler -e serves the same purpose with less emphasis. Similarly, the phrase i hoʋe-ke gahp=e “This house is big” (example 5) uses -ke to emphasize “house,” while in hoʋe-ke gahp=e “The house is big” (example 6), the same marker is used without the demonstrative pronoun i to denote definiteness more generally. These examples illustrate the flexibility of the definite marker in Bakhtiari, allowing speakers to modulate emphasis and definiteness depending on the context.

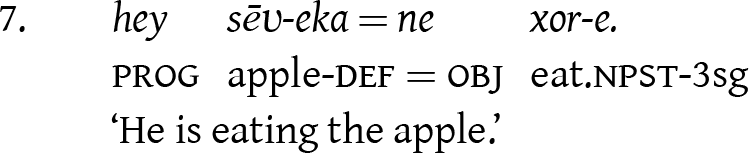

The definite marker precedes the object-marking clitic -(n)e. This structure is seen in both present and past tense structures (examples 7, 8, 10 and 11). The interaction between the definite marker and object marker in Bakhtiari is a clear point of difference from Persian. The definite marker precedes the object marker in singular and plural nouns in Bakhtiari. However, the definite marker is absent between the plural marker and the object marker in Persian.Footnote 41 It is worth noting that the definite marker may or may not be attached to plural nouns (example 9).

In Bakhtiari, as in colloquial Persian, the definite marker can be affixed to a noun phrase that includes both a noun and an adjective, functioning to indicate definiteness across the entire phrase. This pattern is particularly interesting because it shows how definiteness is extended to the whole noun phrase, rather than just the noun itself.

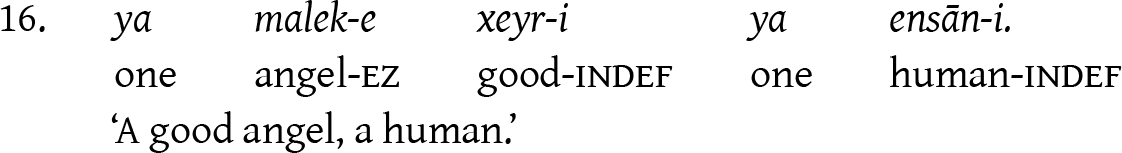

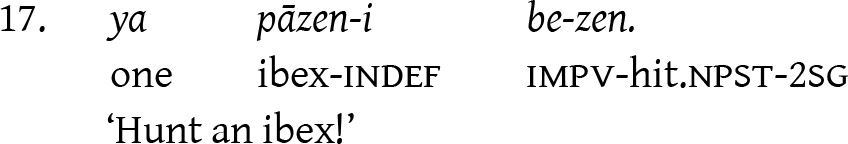

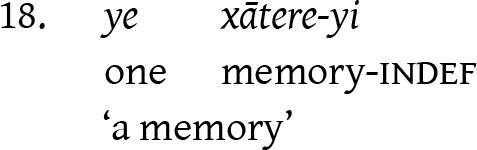

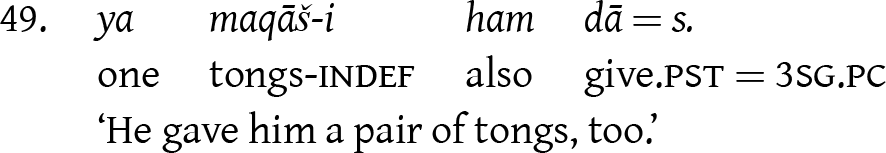

Indefinite marker

Indefiniteness in the Bakhtiari dialect is often marked by an unstressed suffix -i attached to the noun, and is typically also accompanied by the numeral ya or ye meaning “one” preceding the noun. This construction serves to indicate that the noun is indefinite, referring to a non-specific entity.

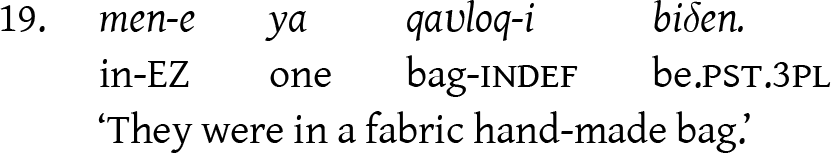

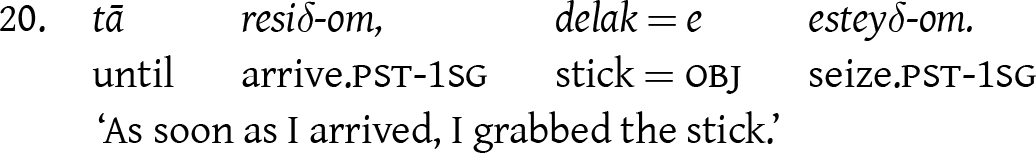

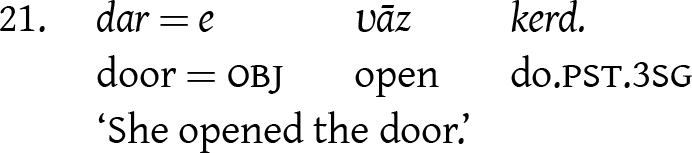

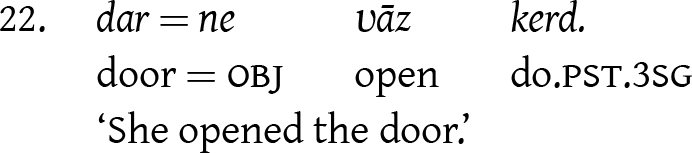

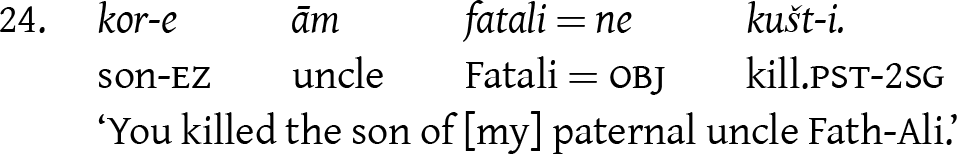

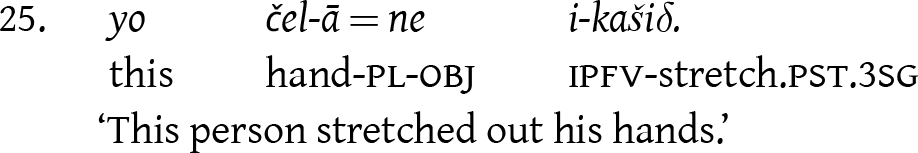

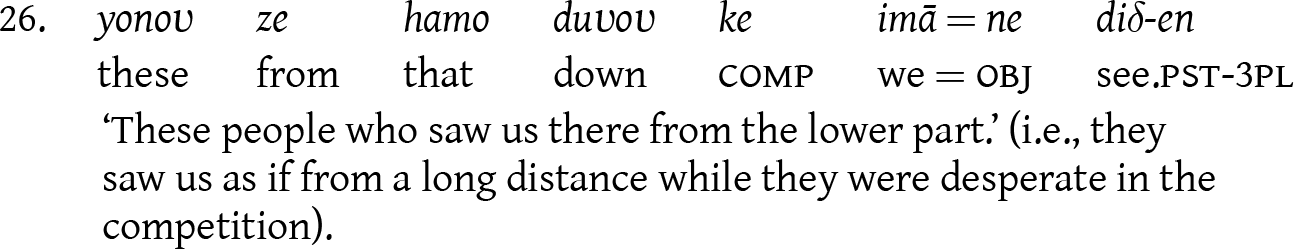

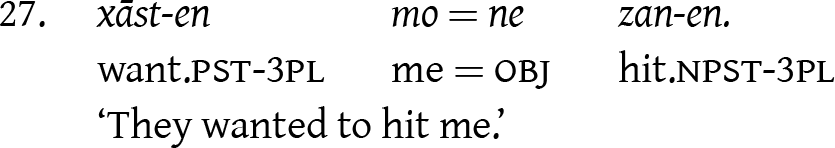

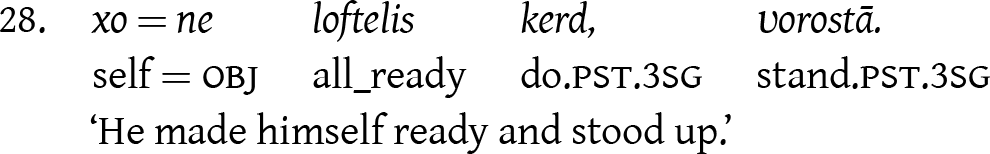

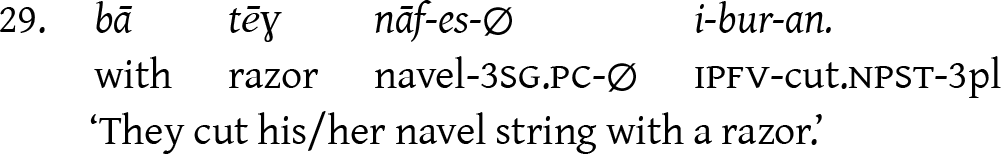

Object marking

Specific direct objects are marked by =e or =(e)ne. The following examples (20–28) highlight how Bakhtiari marks direct objects with the enclitic =e or its variant =ne. The clitic attaches to the noun or pronoun functioning as the direct object. In general, several semantic and discoursal features play a crucial role in the occurrence of object marking, including but not limited to definiteness, specificity, animacy, topicality, and emphasis. There are distinct instances in which Bakhtiari diverges from Persian in its object marking patterns, as exemplified in example 29 below. A comprehensive analysis of these divergences could provide deeper insight into the syntactic and semantic nuances that distinguish Bakhtiari from Persian.

The ezafe linker

As in Persian, ezafe (-e) acts as a link with modifiers, e.g., kor-e gahp “big boy” and dar-e hoʋe “the door of the house.” In addition to nouns, ezafe is also suffixed to some prepositions, e.g., men-e raʋraʋ-e pā=s “within his ligament” and jāneʋ-e xoδā “in the direction of God.” This linker is realized as zero when attached to vowel-final words: hoʋe gahp “big house,” šāširoʋ “king of lions,” and piyā duši “the man we met/saw yesterday.”

Prepositions

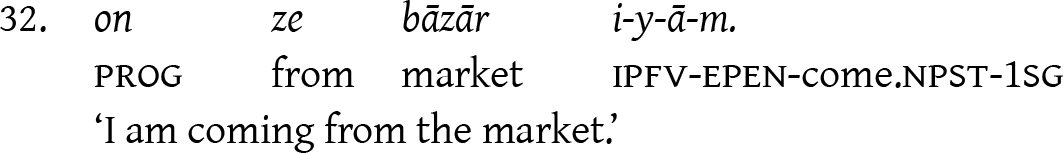

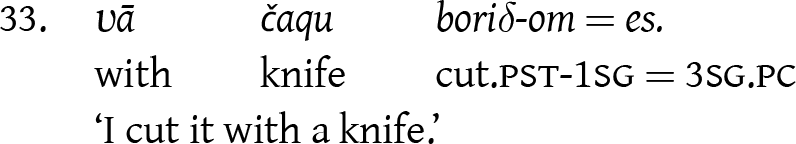

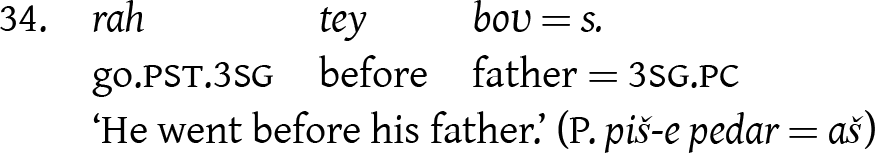

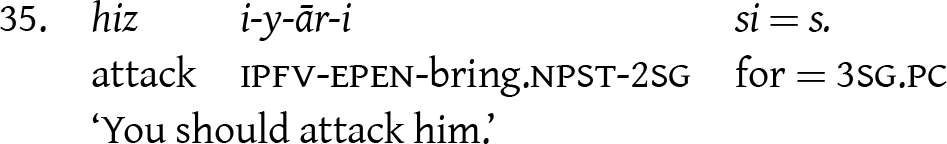

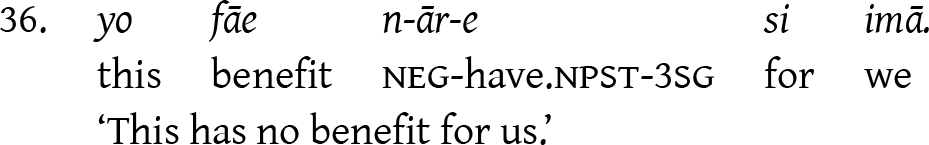

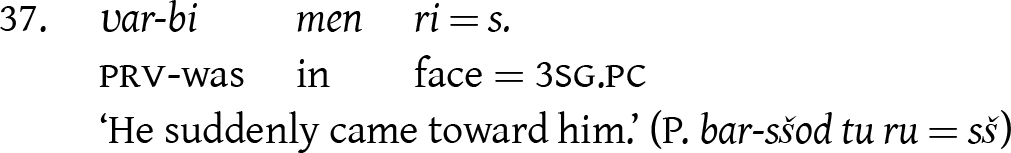

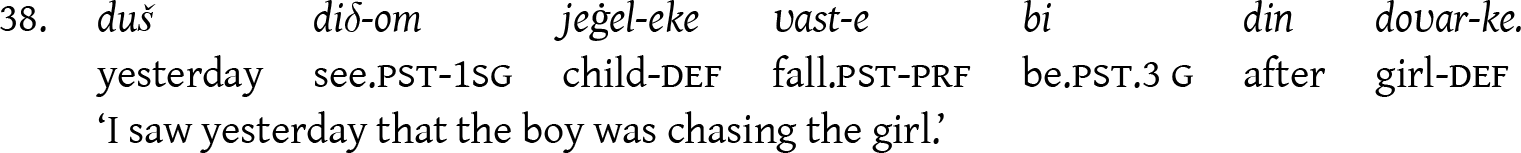

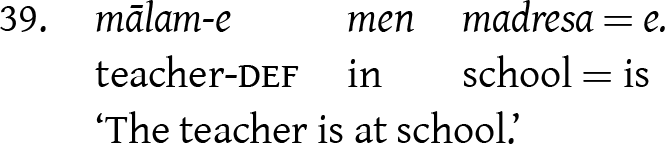

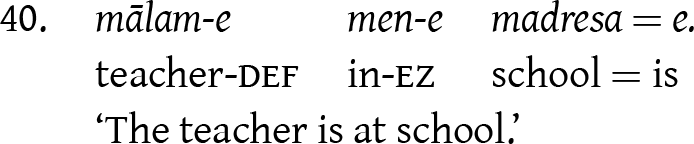

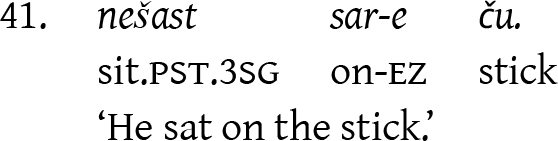

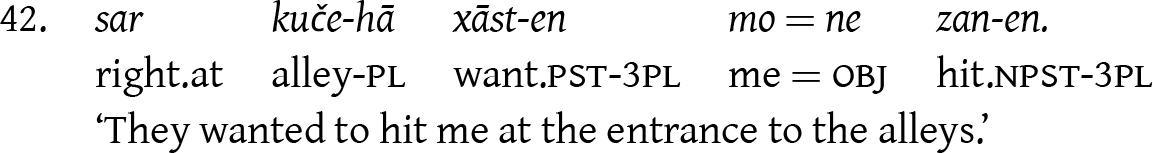

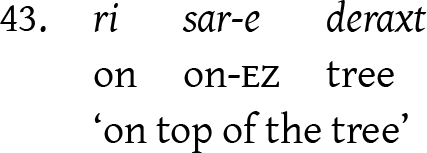

With the exception of the object marker, which functions as a postposition, all other adpositions in the dialect are prepositions. Frequently used prepositions include ʋā “with, to,” ri “on,” si “for, to,” tey “before,” ze “from,” men “in,” be “to,” and tā “until.” Some prepositions in Bavadi are simple and occur without an ezafe (examples 32–36). Another group of prepositions may link to their complement through an ezafe (examples 37–42). Additionally, there are prepositional expressions formed by the combination of simple prepositions, as demonstrated in example 43.

Pronouns

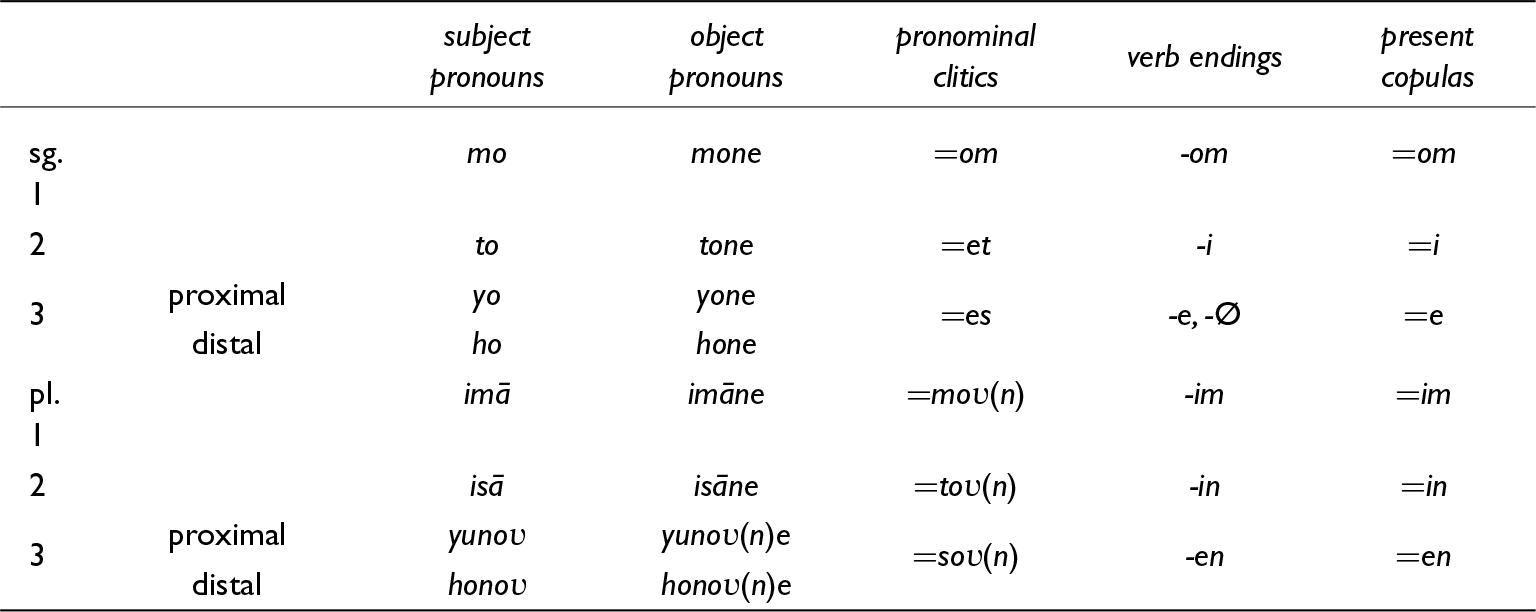

There are two basic sets of personal pronouns: independent and enclitic (oblique), as shown in Table 4. The object set is constructed by adding -ne to subject pronouns.

Table 4. Pronouns, verbal endings, and copulas

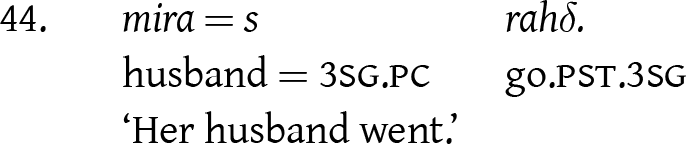

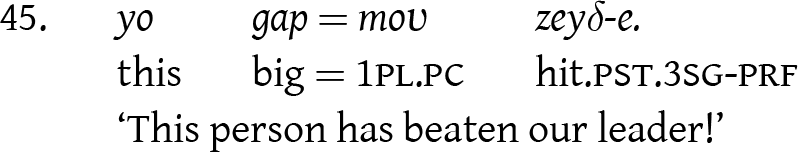

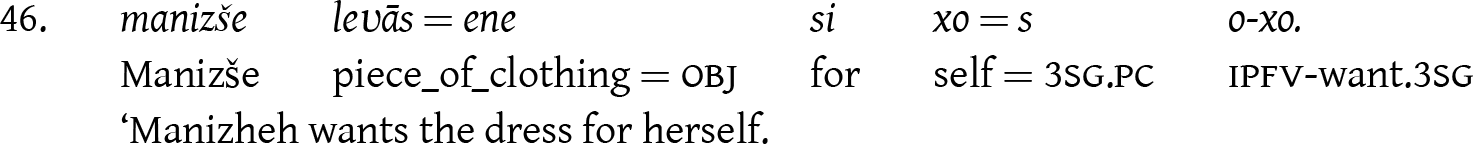

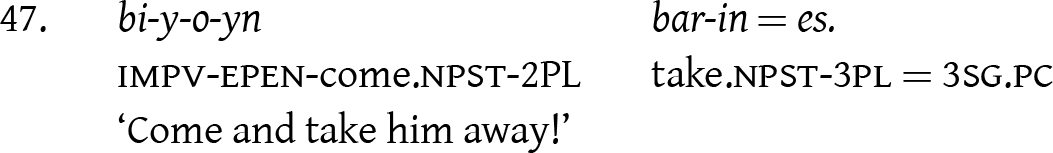

In Bavadi, pronominal clitics play a crucial role by marking various syntactic functions and relationships within sentences. These clitics are used to denote possession, direct and indirect objects, and the objects of prepositions, as well as to convey experiential states. The pronominal clitics may function to indicate possession and are used to mark relationships between nouns and their possessors, as illustrated in the examples 44–46.

In addition, the following examples highlight how direct objects are represented through pronominal clitics, which are attached to the verb to explicitly mark the recipient or target of the action.

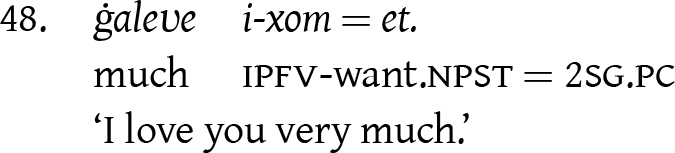

Example 49 shows how, in Bavadi, the indirect object is indicated through pronominal clitics attached to the verb.

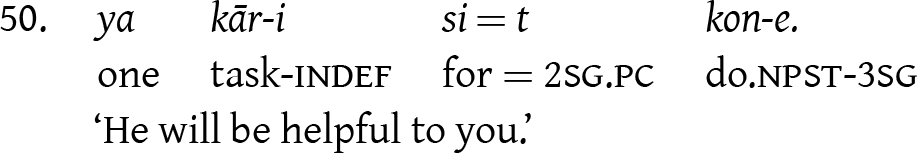

Example 50 and 51 illustrate how prepositions in Bavadi interact with pronominal clitics to specify the objects related to the prepositional phrases.

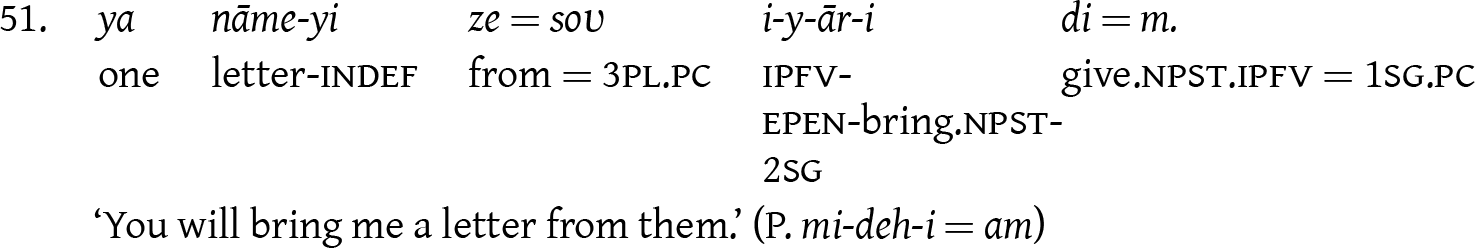

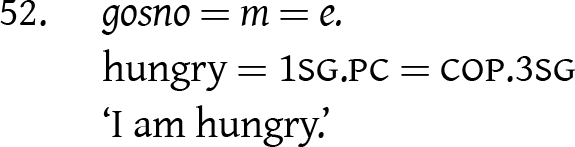

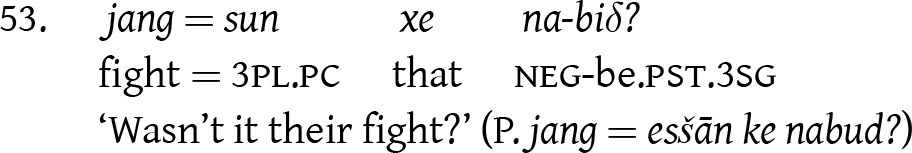

Examples 52 and 53 demonstrate how Bavadi uses experiential constructions, employing clitics and copula verbs to convey the subject’s relationship to the described state or event.

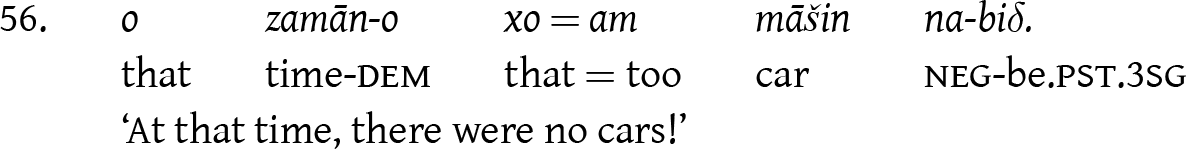

Deixis

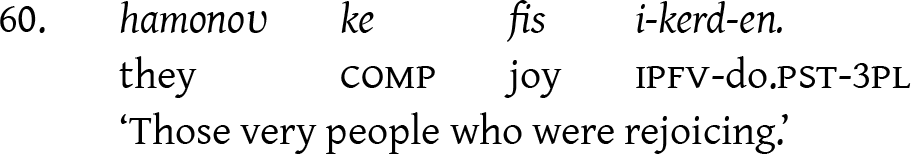

In Bavadi, as in many other languages in the region, there are distinctions between near deixis and far deixis demonstratives. These demonstratives include i “this,” o “that,” yunoʋ “these,” and honoʋ “those.” As in Persian, singular demonstrative adjectives qualify plural nouns. Demonstrative adjectives are accompanied by the optional discontinuous suffix -o, which takes the stress;Footnote 43 the latter is similar to the definite marker -e. Other typical markers of deixis are ičo “here,” očo “there,” hamonoʋ “those very,” and hamčo “over there.”

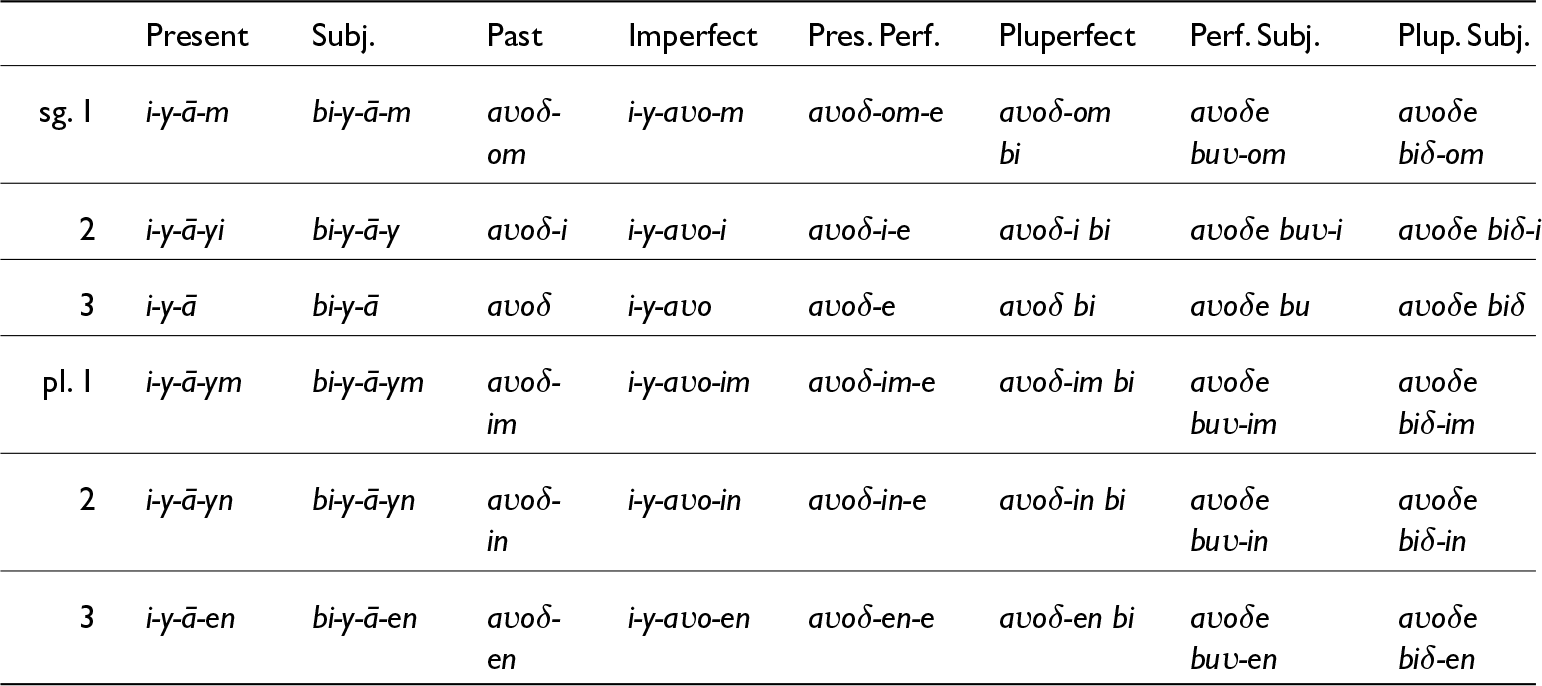

Morphosyntax: verb phrase

This section explores the morphological and syntactic features that define the verb phrase, focusing on the stems and affixes in constructing various forms. We also examine the formation and use of different tenses, progressives, and the stative verbs. Additionally, this section explores how optative and modal verbs are constructed and employed within the verb phrase.

Stems

There are two verb stems in Bavadi Bakhtiari: the non-past stem serving the present-future tense in both indicative and subjunctive moods, and the past stem, which is employed in all past tenses. The following is an example: e-n-om (ipfv-put.npst-1sg) “I place”; nehāδ-om (put.pst-1sg) “I placed.”

Affixes

The imperfective marker is the prefix i- or -e, as in i-zeyδ “he was hitting” and e-zeyδ-en “they were hitting.” The subjunctive be- applies to the imperative, be-zen “hit!”; subjunctive, be-zen-om “I would hit”; and optative be-zayδ-om “may I hit.” It is superseded by the negative morpheme nV-. There are lexical prefixes, or preverbs, including ʋer-/ʋar- and der-, as in ʋer-ār- “bring forth” and der-ār- “bring out.” Unlike Persian, the negative morpheme is followed by the preverbal element:

Personal endings are listed in Table 4. The third person singular ending is normally -e in present tenses and zero in past tenses.

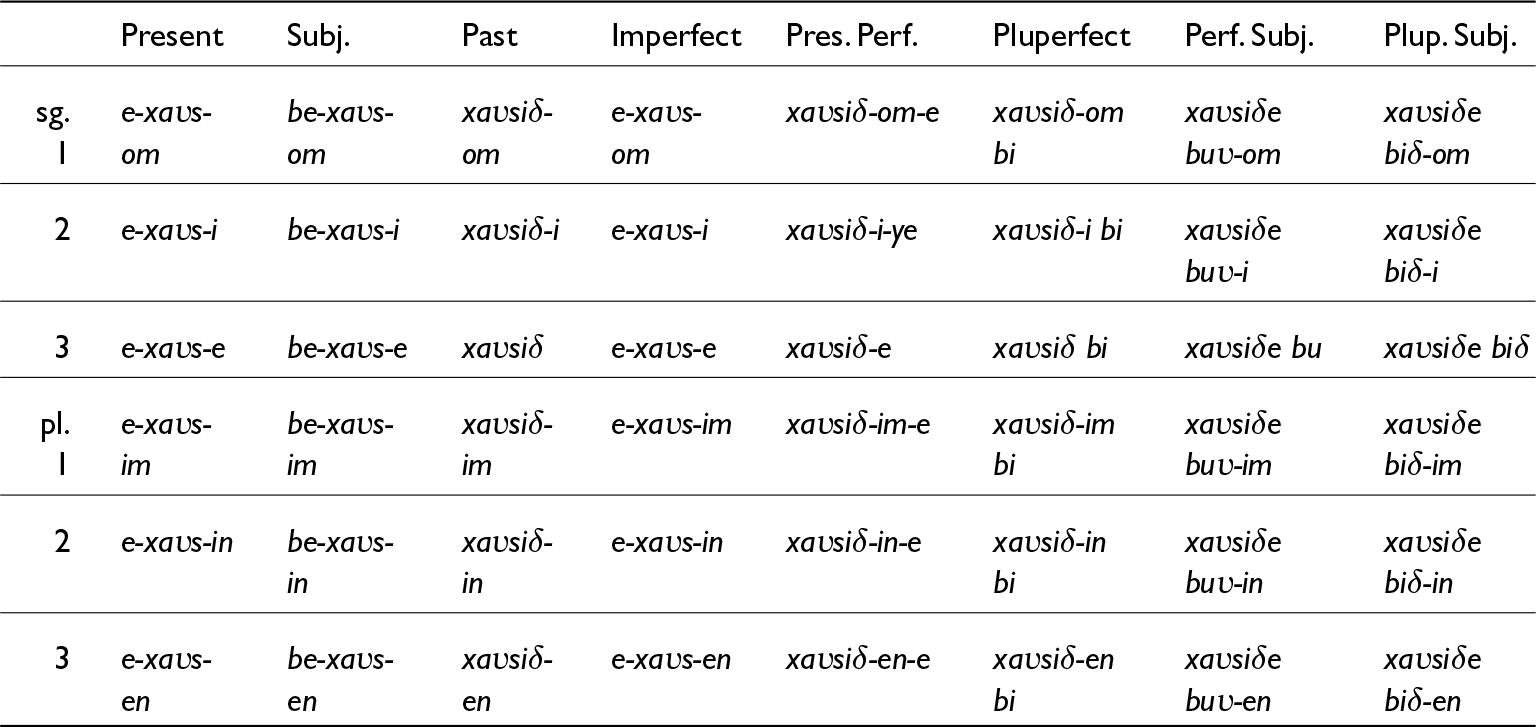

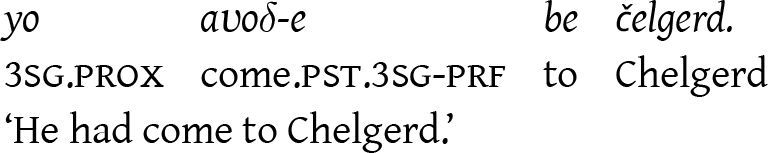

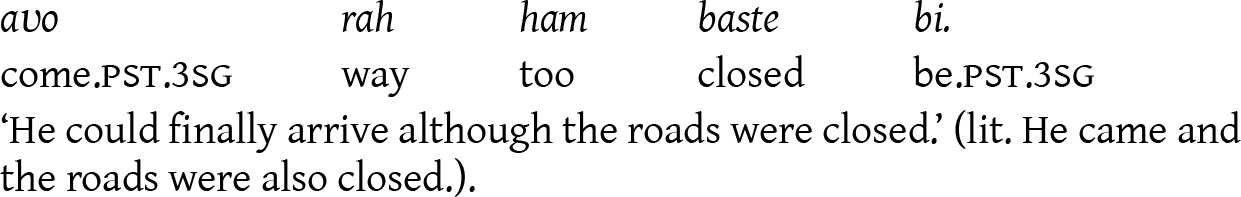

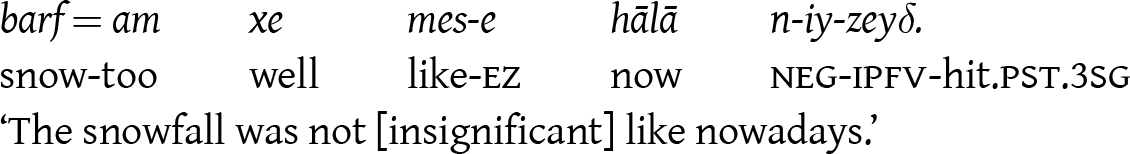

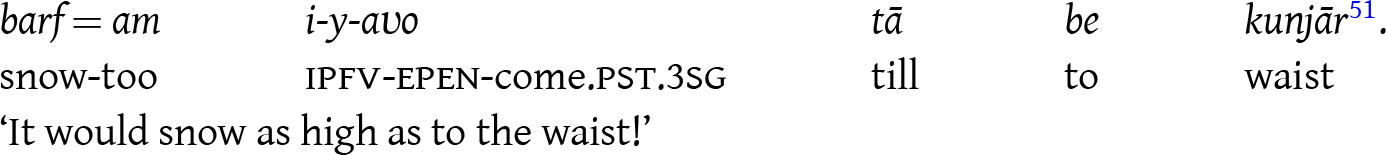

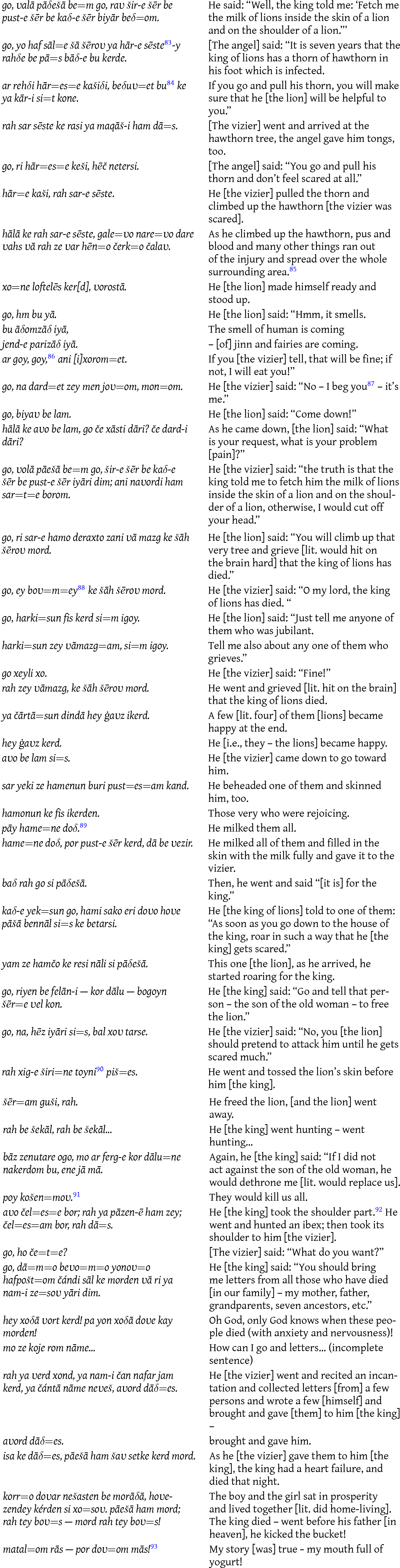

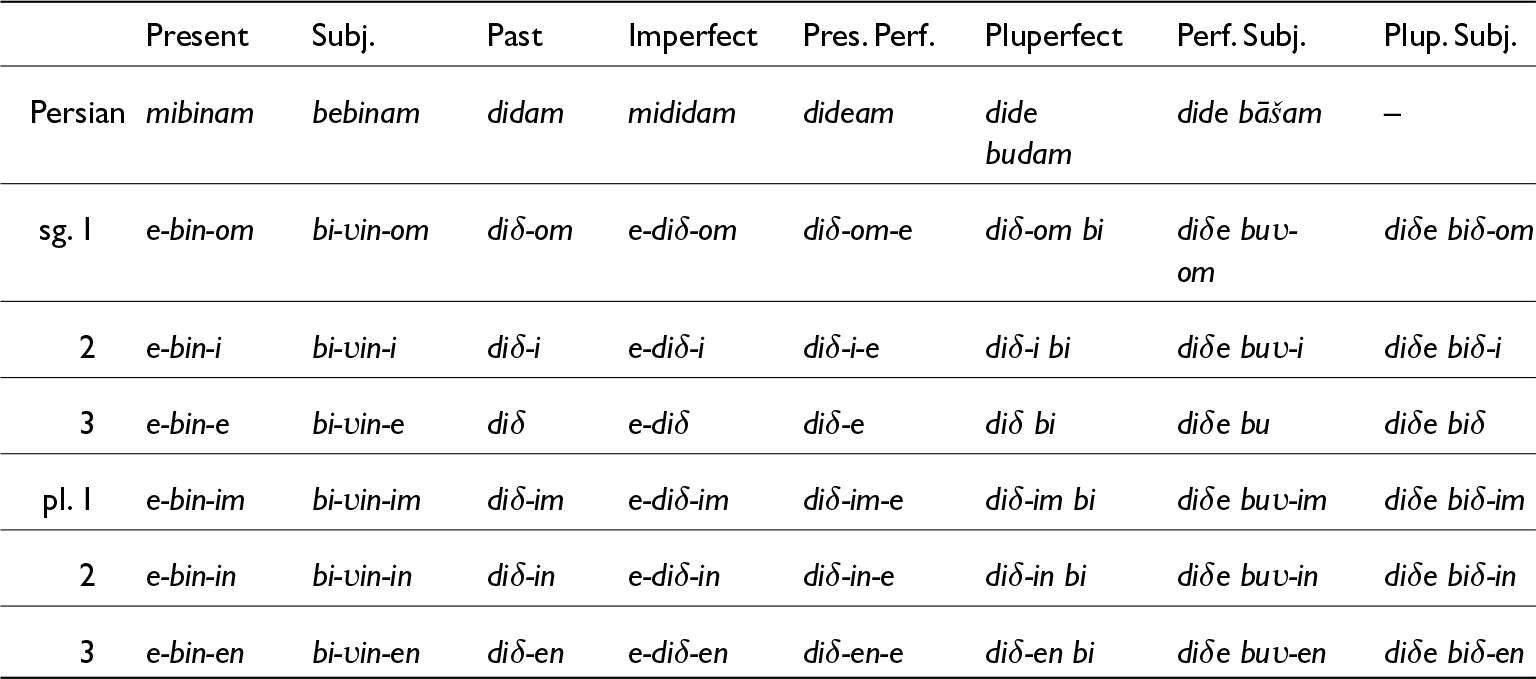

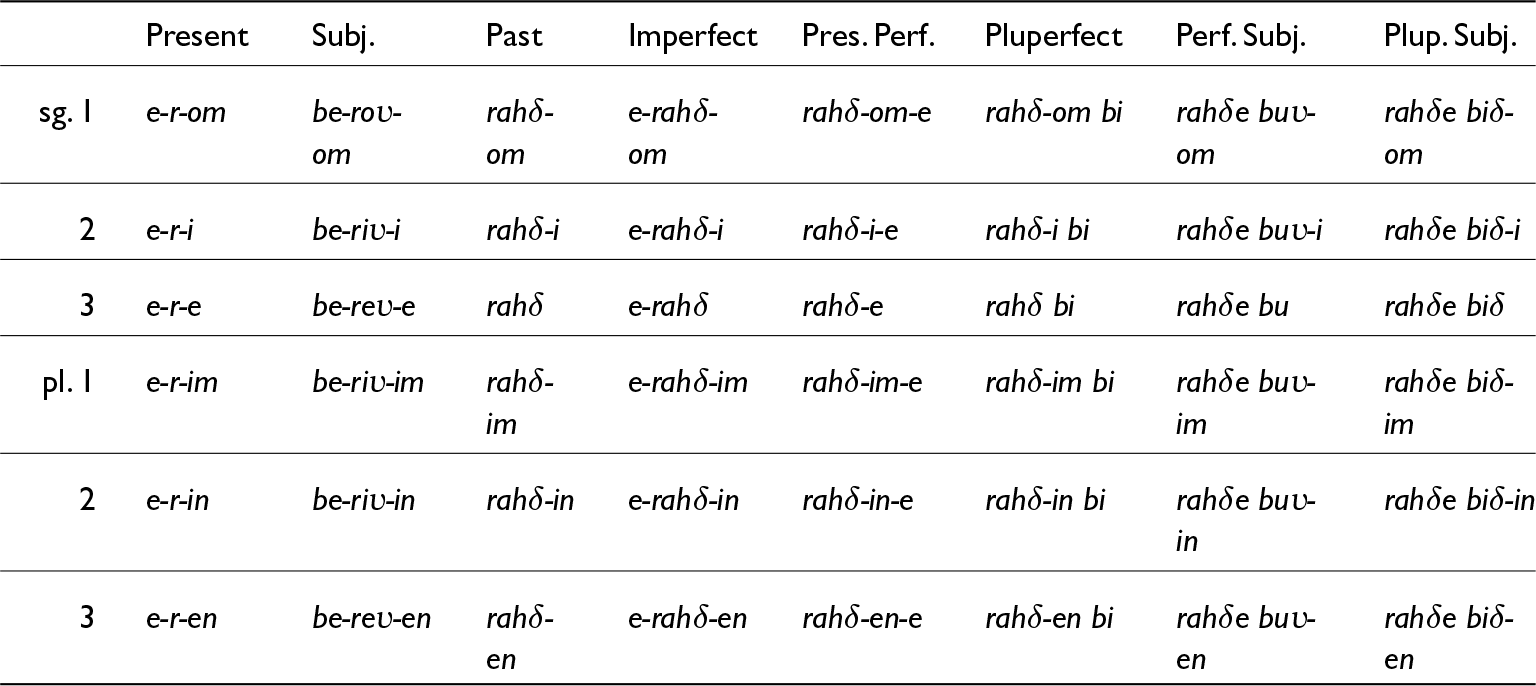

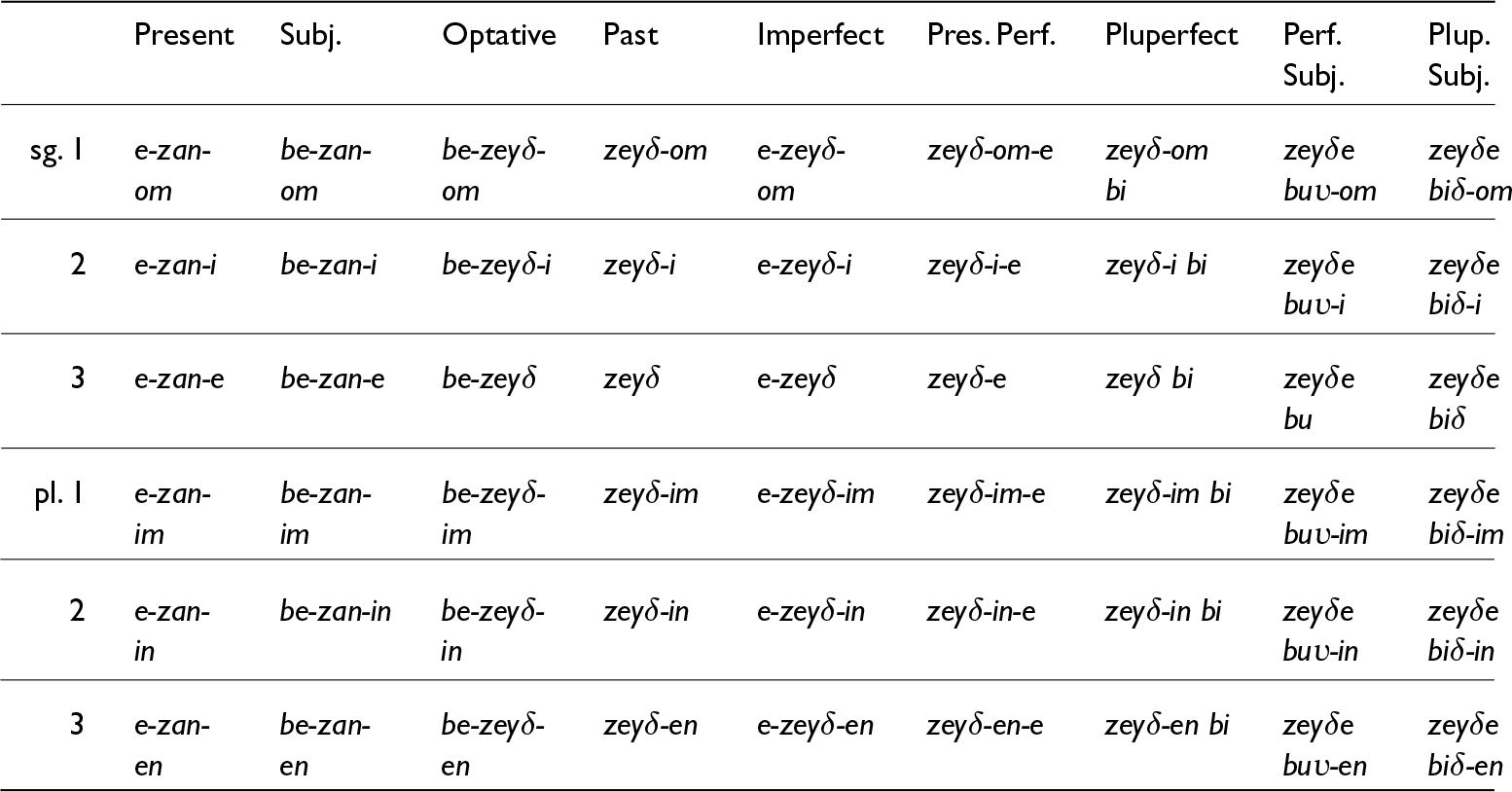

Tenses

Table 5 summarizes the verb structures that occur in the data, offering an overview of the various prefixes, stems, and suffixes used across different tenses in Bavadi. This table outlines how specific morphological elements combine to form each tense, from the present indicative to the pluperfect subjunctive. For a more examples of these structures, including specific conjugations and variations, refer to the paradigms presented in Tables A1–A5 in the Appendix.

Table 5. Verb Forms in Bavadi

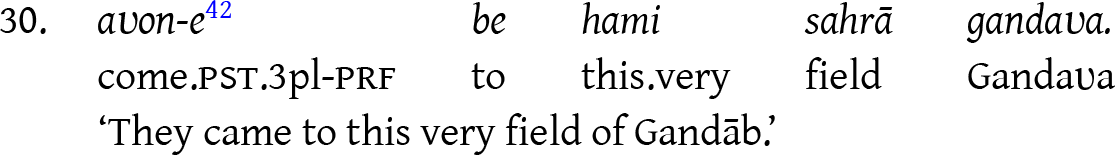

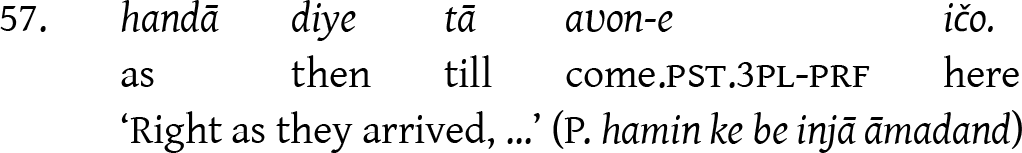

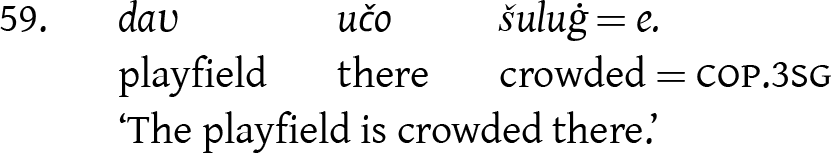

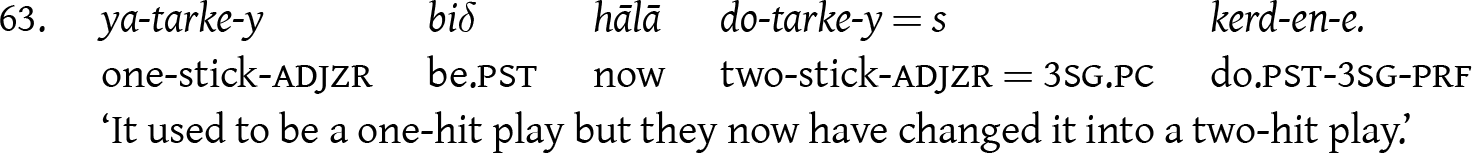

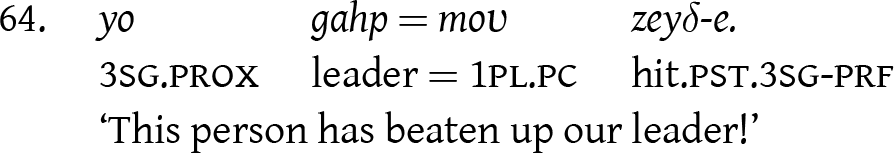

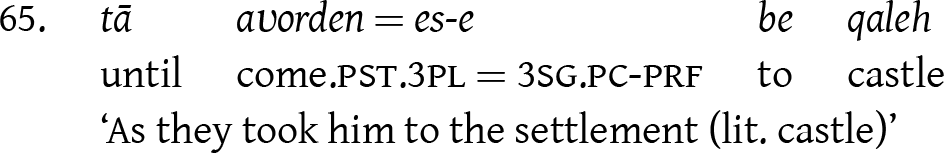

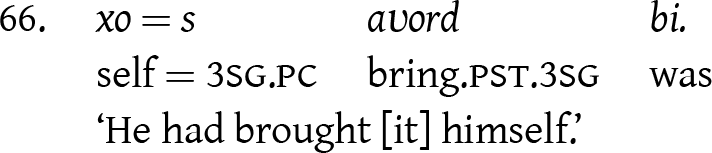

The present perfect is formed by attaching -e to the person marking on the past morpheme, as illustrated in examples 63 and 64. This present perfect ending carries the stress. In contrast to Persian, the suffix -e is added not only after the person marking but also after the pronominal clitics, as in example 65.

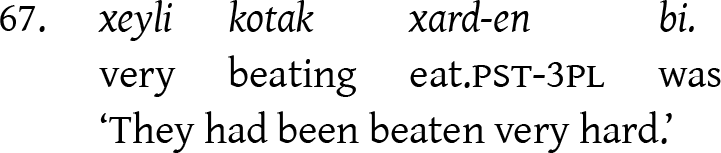

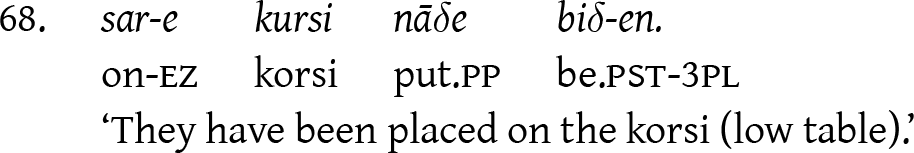

Pluperfects are based on the past tense plus bi, the third person singular of “be” as shown in examples 66 and 67. This differs from the Persian pluperfect, which inflects the auxiliary “be,” as Bakhtiari marks the perfect stem and leaves the auxiliary uninflected. Pluperfect may also be expressed in the Persian form, with the past participle of the main verb and inflected past copulas as in example 68.

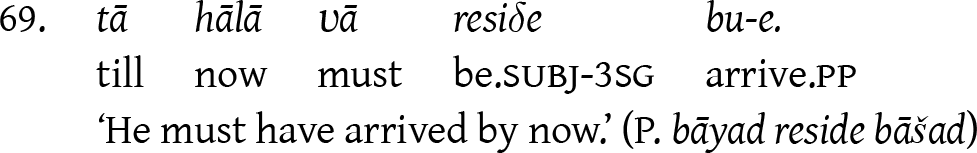

The perfect subjunctive employs the past participle of the main verb followed by the subjunctive forms of “be” as auxiliary.

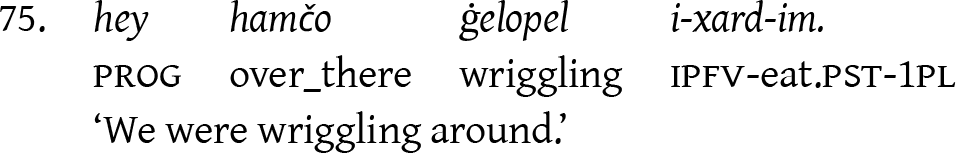

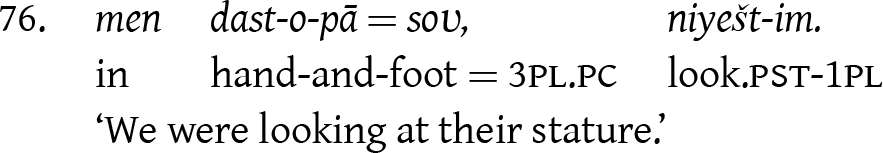

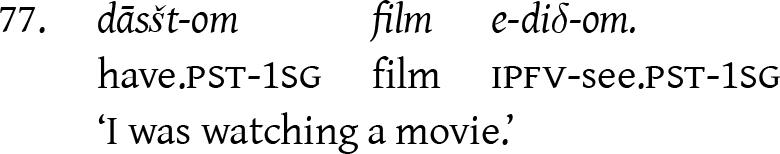

Progressives

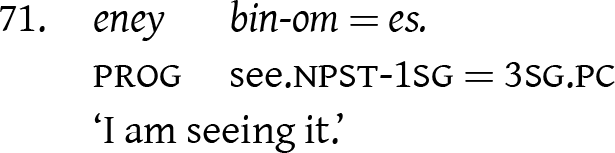

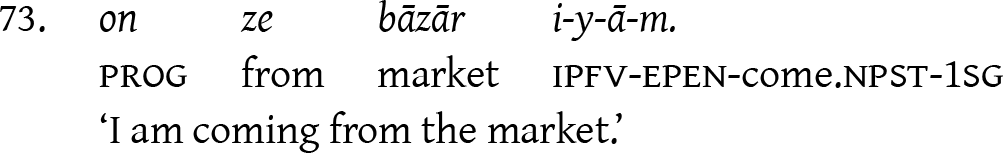

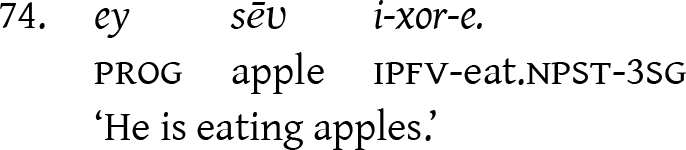

The progressives are built with an auxiliary that appears before the imperfect form. The auxiliary is often (h)ey, en, or both. Occasionally, Persian forms with the auxiliary verb dāštan “to have” are encountered in the data. Note that the imperfective prefix is omitted in examples 70 and 71.

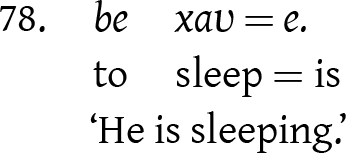

Stative verbs

Unlike dynamic verbs, which are used to form progressive constructions, stative verbs are typically expressed using be. The following examples illustrate this construction.

Optative

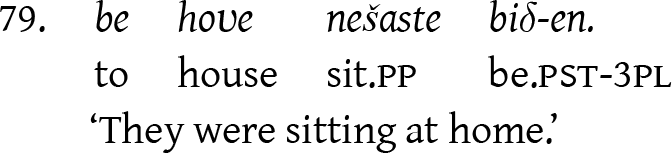

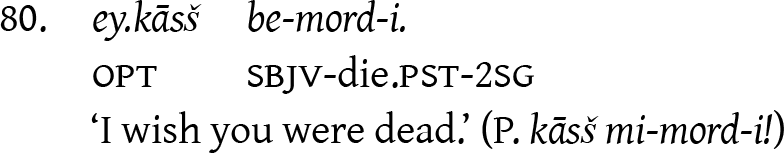

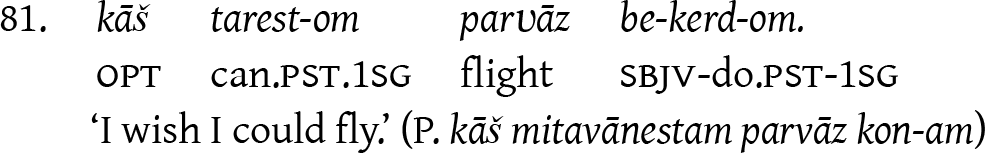

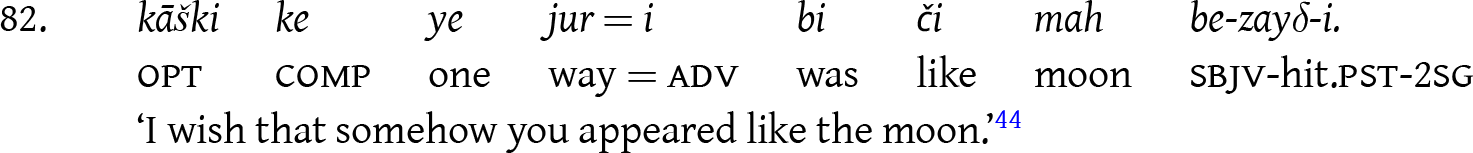

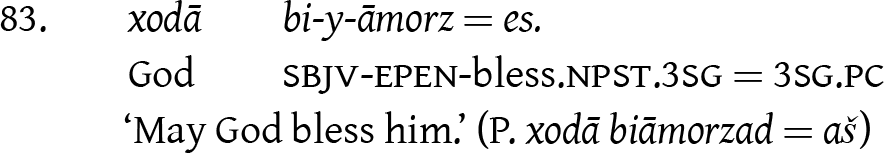

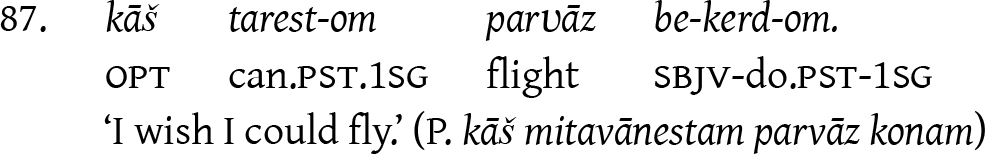

In the data, we were able to identify an optative form not documented elsewhere: be- + past stem + endings. See examples 80–82 and 87.

Another optative form in Bavadi is formed on the present stem + ā + ending + bā, the optative third person singular of “be” (cf. P. bād). In the data, this form occurs only in the negative and typically in the second person singular, e.g., na-zan-ā-t bā “may you not hit” or “I wish you didn’t hit,” but the morphology may be extended for other persons as well: 1sg. na-zan-ā-m bā, etc.Footnote 45 In the following sentence, copied from Persian, the optative mood is formally indistinct from the subjunctive:

Modal verbs

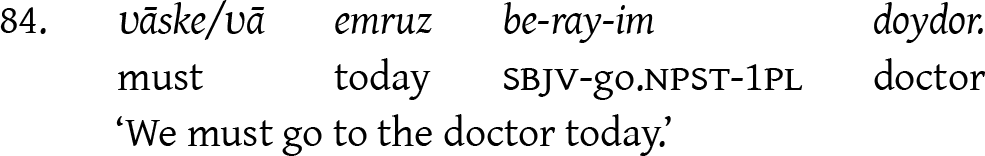

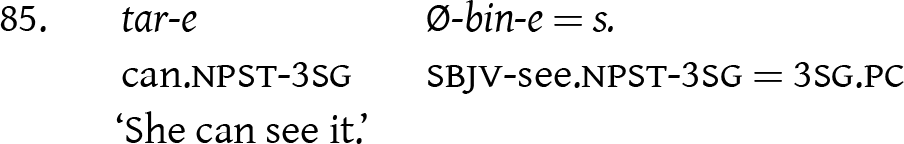

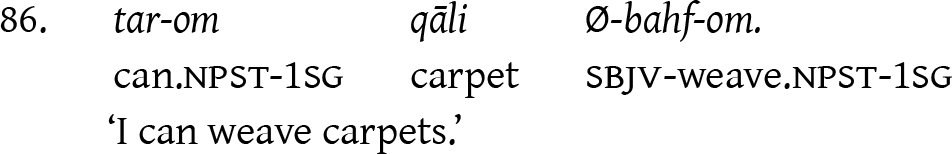

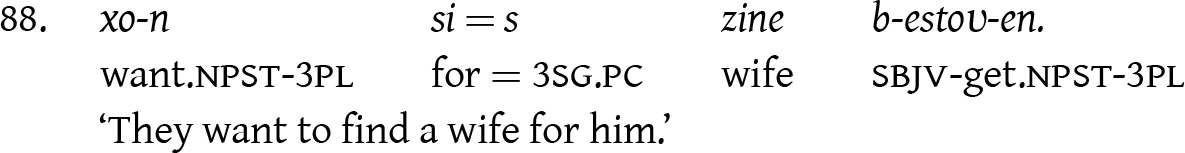

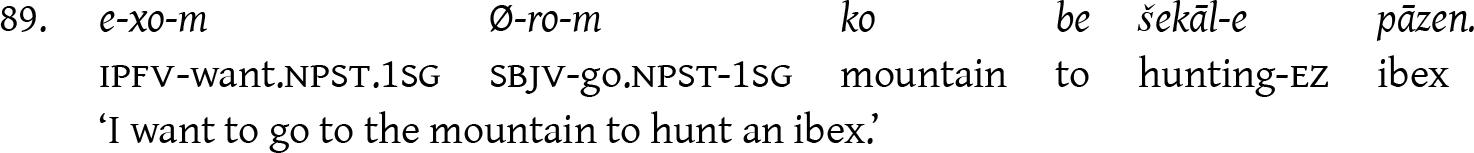

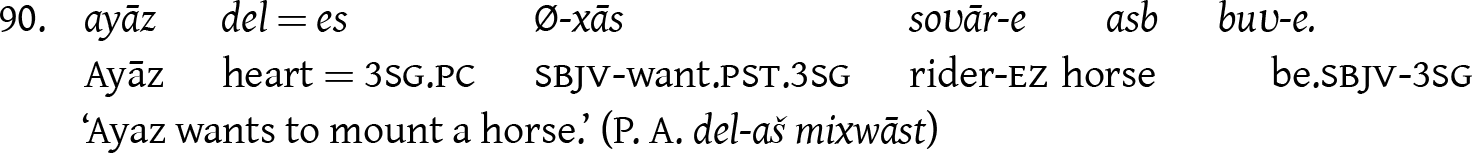

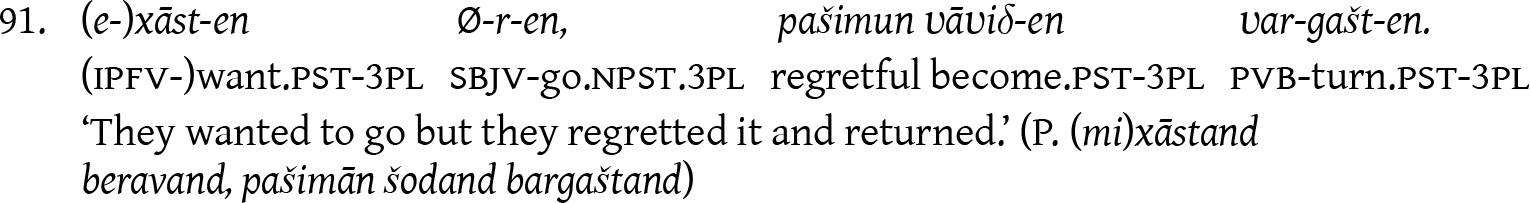

Major modals in Bavadi, which are usually conjugated without modal prefixes, are: ʋāske, ʋā “must”; tar- as in tarest- “can”; and xo- as in xāst- “want.” Modal verbs are followed by the subjunctive of the main verb. Note the subjunctive appear without the modal prefix be- in examples 85, 86, and 89–91.

Texts

Here, we present three of the oral texts collected in the course of our research on Bavadi Bakhtiari. For the first portion of each text, we provide a window into an array of its linguistic structures through full interlinear glossing. In the interest of space, the remainder of the texts are presented in a parallel Bakhtiari-English format.

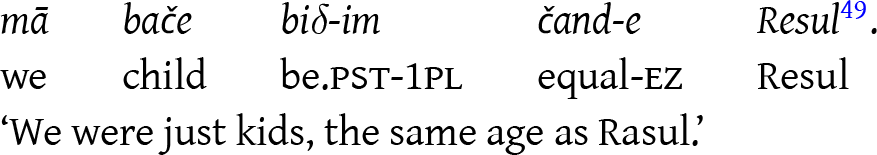

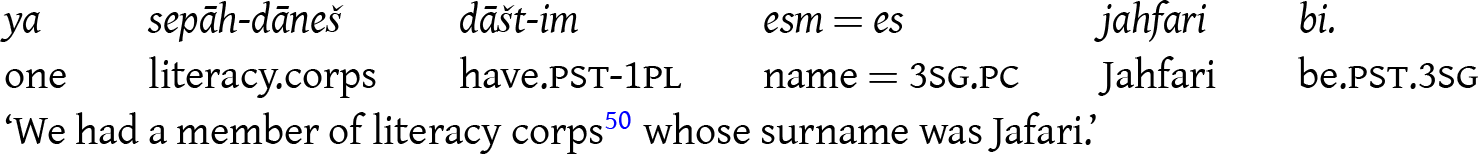

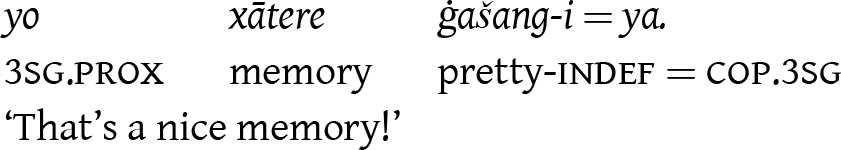

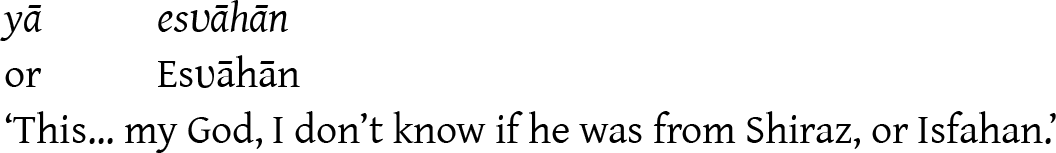

ĀkalbaliFootnote 46 “Ākalbali man’s name”

The name Ākalbali “man’s name” was recorded in Fāni Ābād. The speakers are Ardeshir Parvizi, age forty-nine, who serves as the main storyteller (Speaker A), Bizhan Parvizi, age fifty-six (Speaker B), and Nowzar Farhādi, age forty-seven (Speaker C), all from the Bavadi community. The narrative describes a memory from approximately forty years previous, involving a few local villagers and a member of the literacy corps sent to educate the population. The main speaker, Ardeshir Parvizi, was an eyewitness to the event.

Speaker A

Speaker B

Speaker A

Speaker B

Speaker A

Speaker C

Speaker A

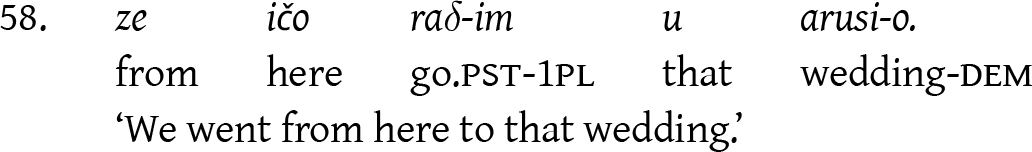

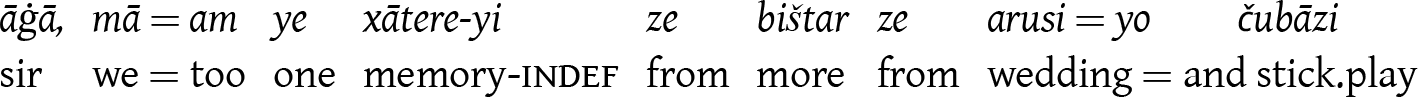

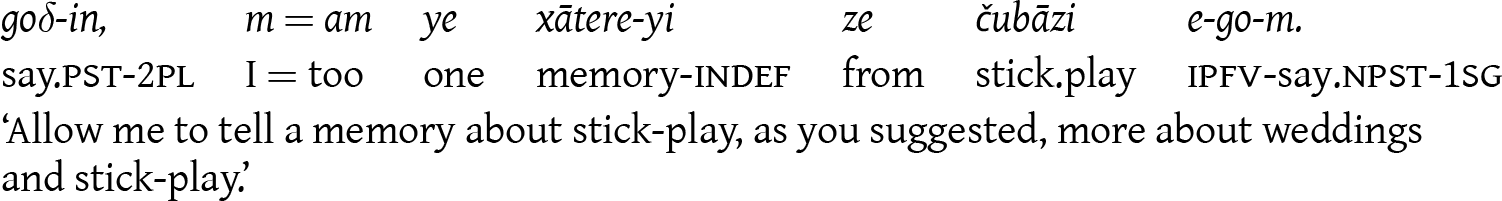

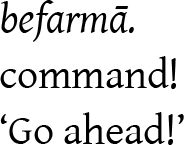

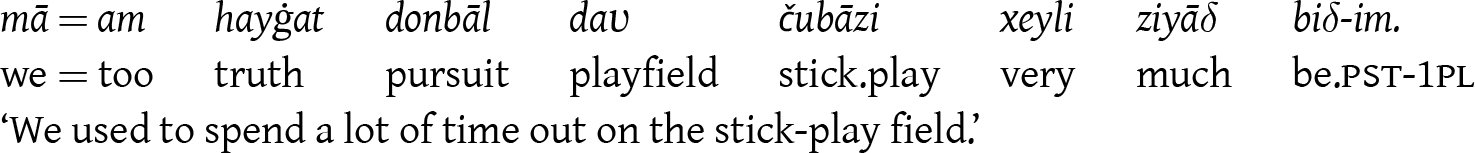

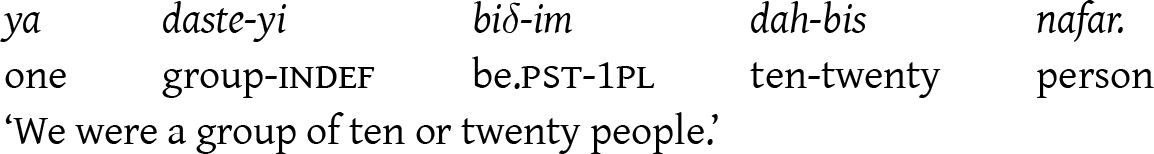

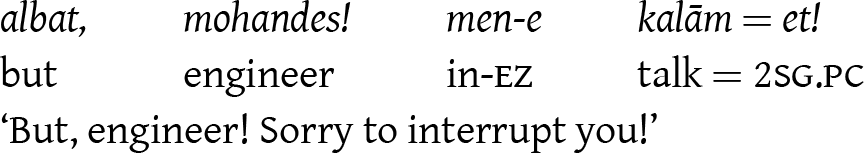

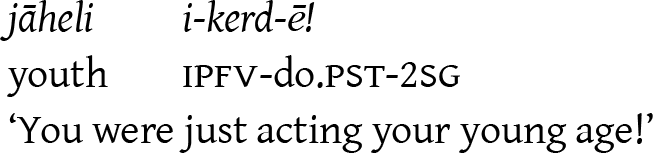

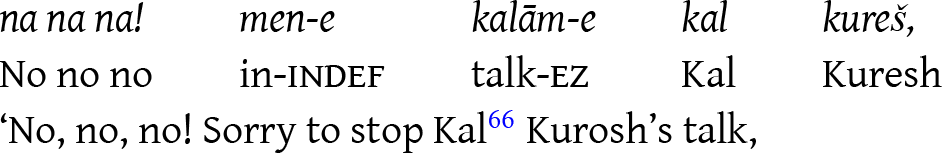

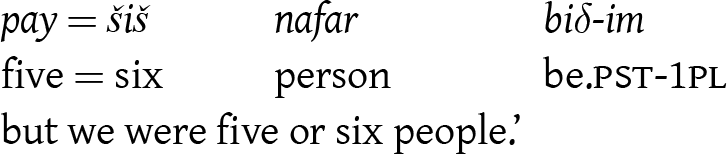

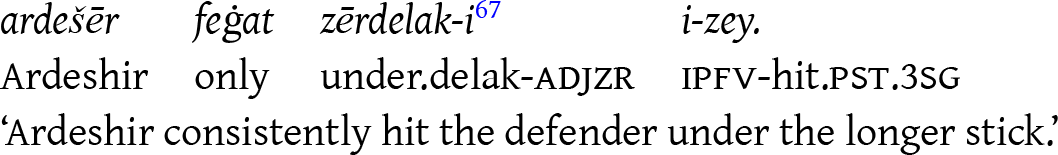

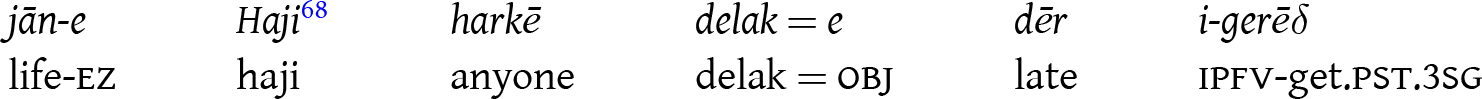

Chubāzi “stick-play”

Chubāzi “stick-play” was recorded in Fāni Ābād. The speakers are Kurosh Farhādi as the main storyteller, age forty-seven (Speaker A), Bizhan Parvizi, age fifty-six (Speaker B), Nowzar Farhādi, age forty-seven (Speaker C), and Ardeshir Parvizi, age forty-nine (Speaker D). This text is a lively exchange about an incident that took place at a wedding ceremony about twenty years previous.

Chubāzi, literally “stick-play,” is a traditional game played by Bakhtiari people at wedding ceremonies. A struggle plays out between two men: an attacker who holds a short stick (tarke) and a defender who holds a long, thick stick (delak), one-and-a-half meters long. The defender protects his legs and feet using only the long stick. Before any attack, the players dance to the music of the drum (dohol) and trumpet (karnā). The game was traditionally a one-hit play, that is, the hitter had the chance to hit the opponent only once, but nowadays the hitter is usually allowed to attack twice in a row.

Speaker A

Speaker B

Speaker A

Speaker C

Speaker B

Speaker C

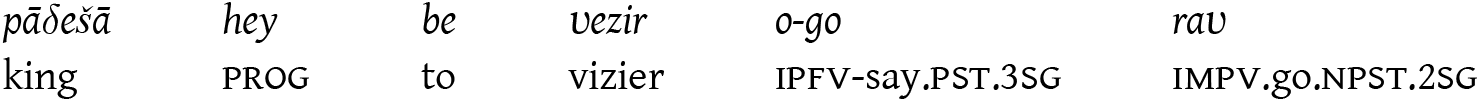

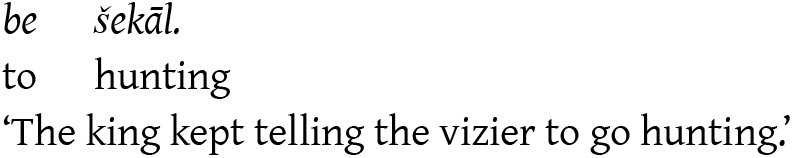

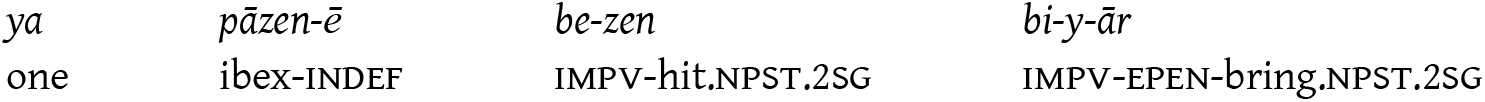

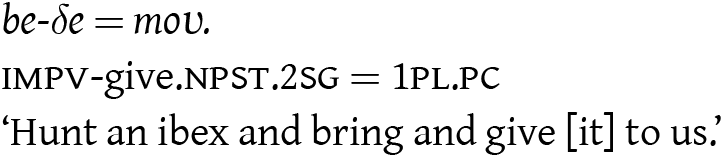

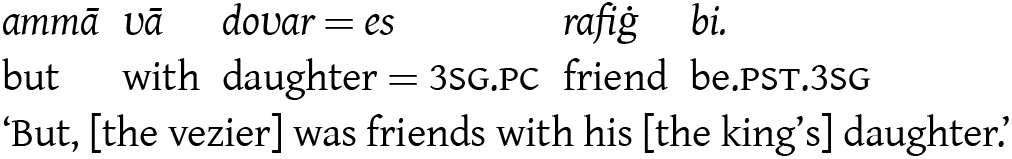

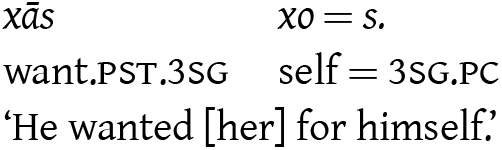

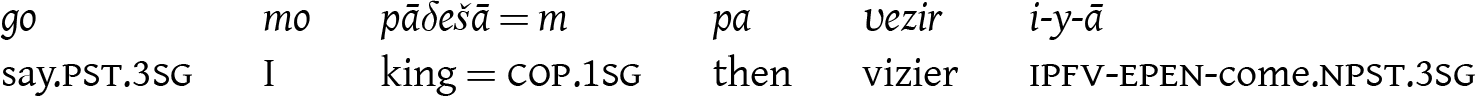

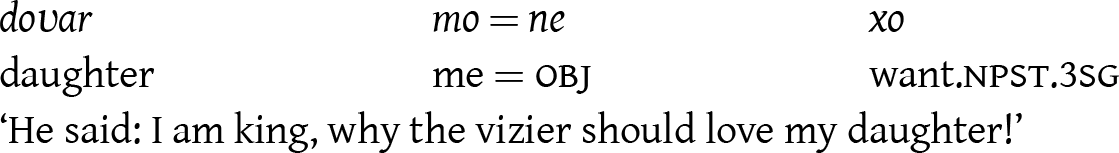

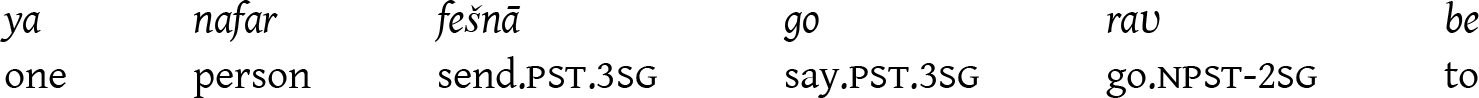

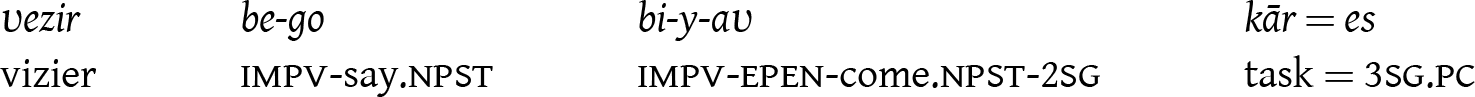

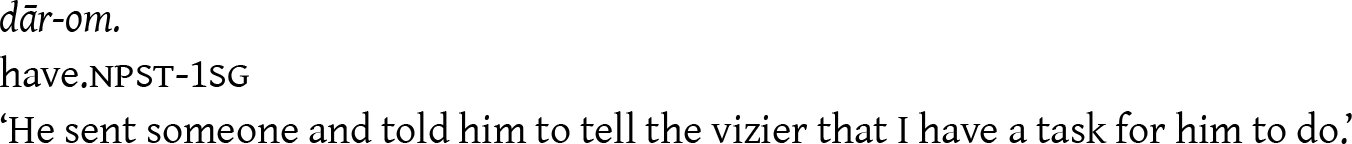

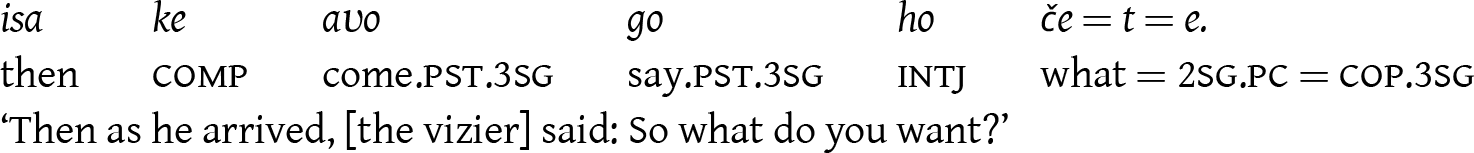

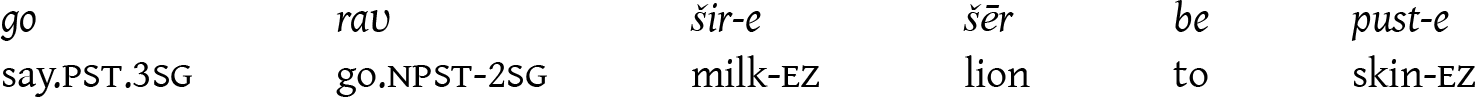

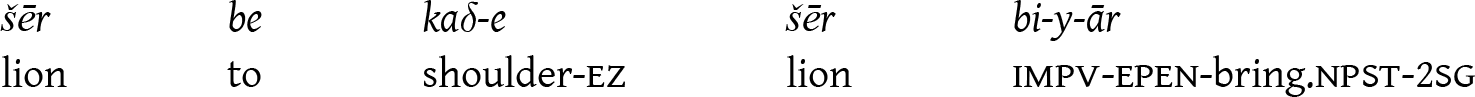

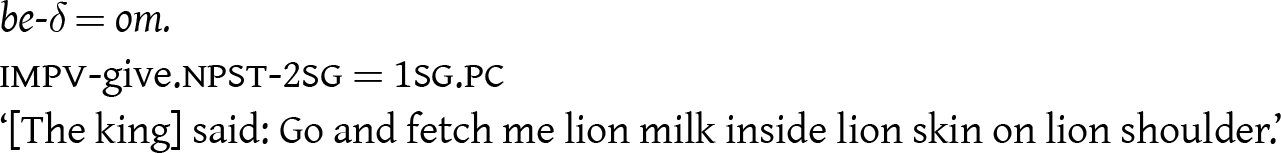

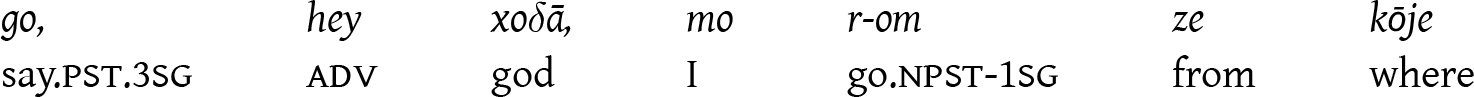

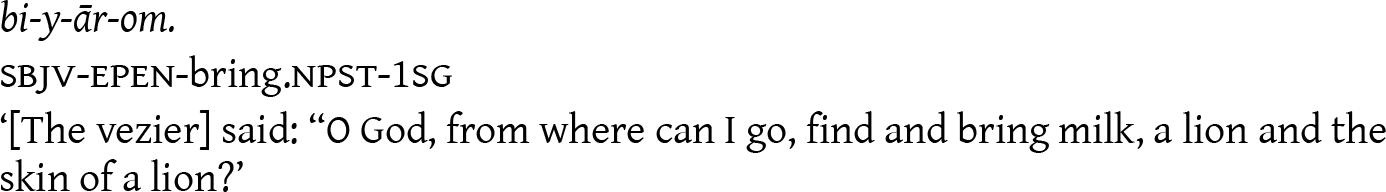

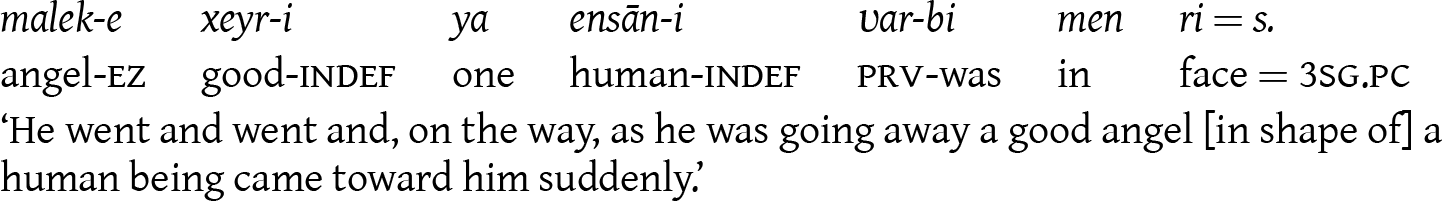

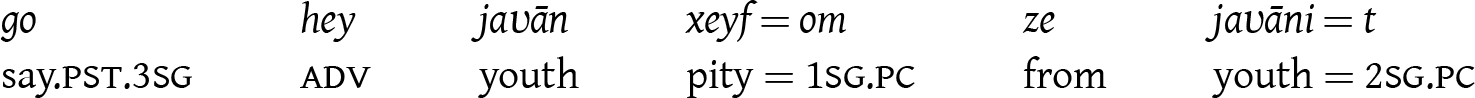

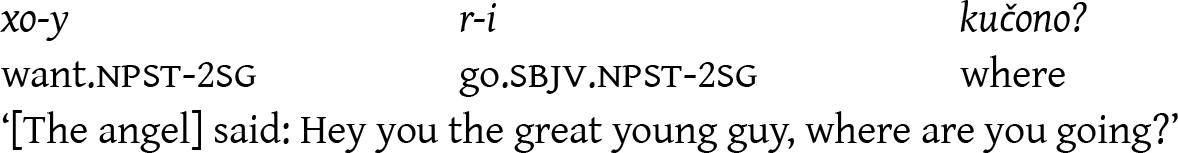

Kačal o pāδešāh “The bald vizier and the king”

Kačal o pāδešāh “The bald vizier and the king” was recorded in Nasir Ābād. The storyteller is Jahān Afruz Nasiri, age sixty. This text is a fairy tale that the storyteller heard as a child from her parents.Footnote 82 In this text, the storyteller delivers a monologue, so there are no exchanges between speakers.

Conclusion

This paper presents the linguistic description of the Bavadi dialect of Bakhtiari spoken by the Bavadi clan in the Kuhrang district, located in the heart of the Bakhtiari homeland in Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province, Iran. The analysis provided here is based mainly on three texts: one from the controlled and formulaic genre of folktales and two from free conversations among groups of speakers. By examining its phonological, morphological, and syntactic characteristics, this study highlights the unique features of Bavadi Bakhtiari and its significance within the broader context of Iranian linguistics.

Our analysis reveals several key findings: Bavadi Bakhtiari is distinguished by its seven vowels and twenty-two consonants. Phonologically, the dialect retains the long mid vowel ē as a distinct phoneme, while its back vowel counterpart has merged with other phonemic categories. The glottal stop does not function as a separate phoneme, but the uvular consonants, including the voiced plosive ġ and the voiceless plosive q, are distinct phonemes. The consonant [ð̞] is treated as an allophone of d, which we have transcribed as δ or “Zagros d” to reflect its unique role compared to Persian. In terms of morphosyntax, we analyzed the nominal and verbal constructions within this dialect. In particular, Bavadi exhibits an optative form (be- + past stem + endings). Also, the negative morpheme precedes the preverbal element, contrasting with Persian, as illustrated in examples such as na-der-aʋoδ-e. Furthermore, definiteness, indefiniteness, object marking, and some other aspects of verbal constructions exhibit distinctive features that set Bavadi apart from Persian and other Southwestern Iranian languages.

These findings advance our understanding of Bavadi and enrich our knowledge of the linguistic diversity within the Iranian language family. We bear in mind that Bavadi has countless linguistic patterns and features that require further exploration from both theoretical and applied perspectives. Future research could benefit from both synchronic and diachronic studies of Bavadi and other dialects within the Lori continuum, employing experimental methods and comparative analyses with related dialects. Exploring the impact of language contact and sociolinguistic factors will further illuminate the complexities of Bakhtiari and its role within the Iranian linguistic arena. Preserving such languages and dialects is crucial to maintaining linguistic diversity and cultural identity, as they embody unique historical knowledge and social practices. The loss of these dialects would mean not only the disappearance of distinctive linguistic features but also the erosion of the cultural heritage and traditions they carry.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of in-depth dialectal research to understanding the rich linguistic status of Iran and contributes to ongoing efforts to document and analyze the region’s diverse dialects.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/irn.2025.2.

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Mohammad Hakim-Azar of the Islamic Azad University of Shahrekord for organizing our trip to Kuhrang; the local governorship (farmāndāri) of Kuhrang, especially its deputy Mr. Ali Badri; Mashhadi Vali Badri, patriarch of the Badri clan in Chelgerd; Mr. Alizamen Nasiri Galeh, the village head (dehyār) of Nasir Ābād; and Ardeshir Parvizi and Ali Ansari, who hosted us in Fāni Ābād and Nasir Ābād, respectively. Many thanks also to Bakhtiari speakers Ardeshir Parvizi, Kurosh Farhadi, Bizhan Parvizi, Nowzar Farhadi, and Ms. Jahan Afruz Nasiri, who provided us with the Bakhtiari texts. We are also grateful to Amir Amani-Babadi, Mohammad Faramarzi, Sajjad Amani-Babadi, Maryam Amani-Babadi, and Malektaj Amani-Babadi for their valuable assistance in transcribing and interpreting the texts.

Appendix

Table A1. Conjugation of ‘see’

Table A2. Conjugation of ‘go’

Table A3. Conjugation of ‘come’

Table A4. Conjugation of ‘hit’

Table A5. Conjugation of ‘sleep’