For some years the study of material culture has flourished. Scholars are starting to ask questions about how objects were used, the meanings they convey and what they tell us about people's beliefs and values.Footnote 1 Very recently, Margaret Murphy has written about material culture and identity in high to later medieval Ireland, and there is substantial work on the early modern era which inter alia makes use of wills and inventories in which objects and spaces might be mentioned or described.Footnote 2 This present case study primarily uses inventory evidence for the possessions of households in later fifteenth-century County Dublin (see figure 1), an area largely characterised by rural settlement. Because household goods are often only indifferently recorded, its focus is less on individual cases as with larger patterns of consumption between social groups. In particular, by making comparison with inventories from later medieval England and from the wine-growing Gers region of south-west France in the mid fifteenth century, it explores both how far like evidence from County Dublin fits within and helps suggest wider European ‘peasant’ and ‘bourgeois’ patterns of consumption. By extension, it will explore the boundaries between the urban and the rural and how far a hybrid suburban identity can be discerned. In some cases a combination of close reading and statistical analysis can be used to recover occupational identities, something that the source does not specifically record.Footnote 3 In a few instances it is possible to comment on the significance of the material culture of specific households.

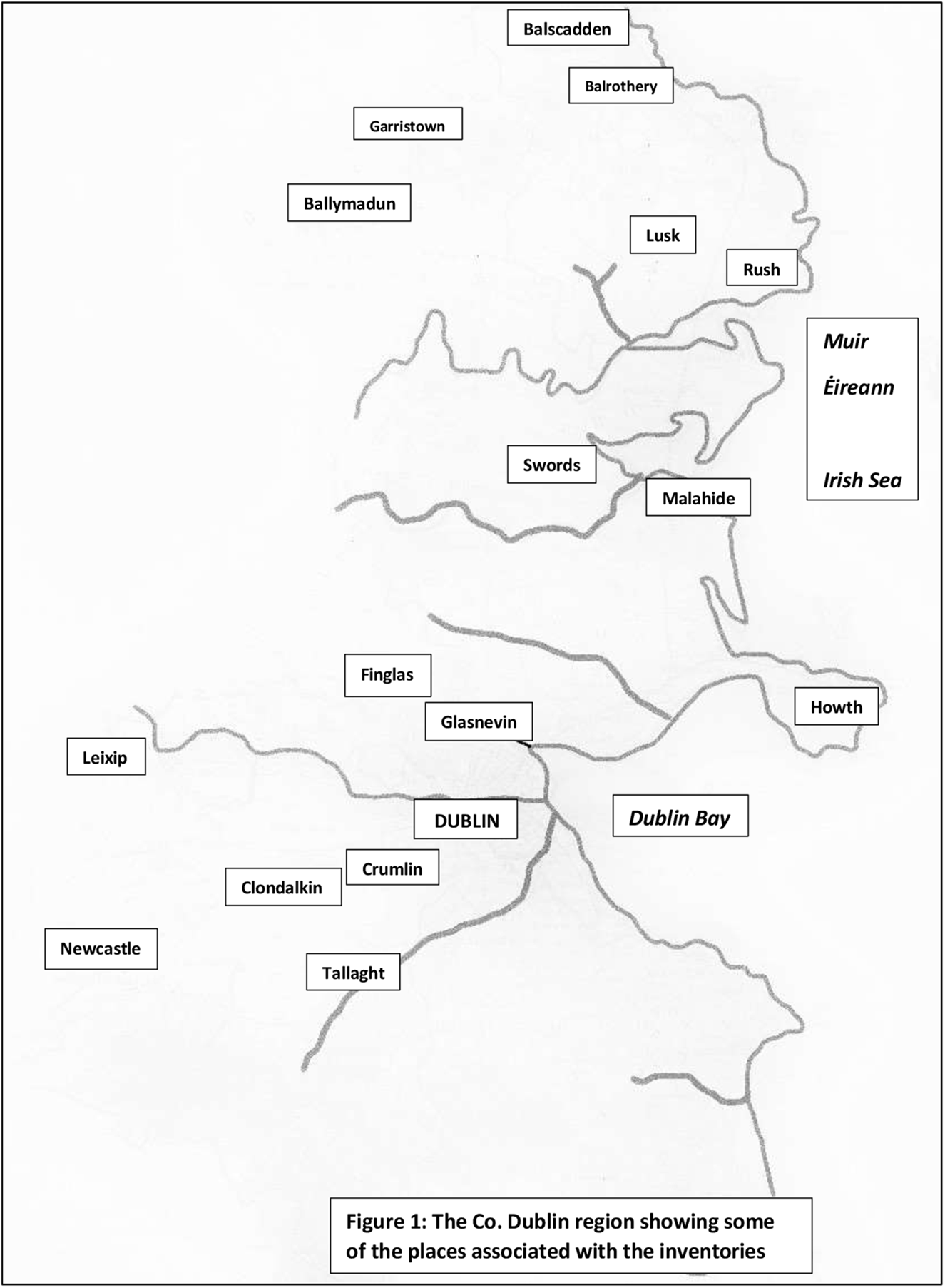

Figure 1. Map of County Dublin region showing some of the principal locations associated with inventories.

I

The study uses a remarkable later fifteenth-century episcopal register containing wills and inventories from the diocese of Dublin.Footnote 4 This was transcribed and published in record type, so preserving abbreviations, with added translation by Henry Berry (he later changed his surname to Twiss) in 1898.Footnote 5 The collection contains seventy-one inventories of possessions, including debts owing and owed, together with associated wills, including a number of married women's wills.Footnote 6 Over the past thirty years, several scholars have made valuable use of the wills, which by their nature are focused on death and pious provision.Footnote 7 For example, Murphy discusses the substantial post-mortem provision by Lady Margaret Nugent for her parish church of St Michan's. Her observation that ‘her material possessions were … to be used to enhance the particular space she was to occupy in death’ complements, as we shall see, Lady Margaret's life-time concerns suggested from her inventory.Footnote 8 Less attention has hitherto been paid to these inventories, which better reflect pre-mortem material circumstances. Aside from Berry's introduction, they have only more recently been exploited. They are used by Margaret Murphy and Michael Potterton in their socio-economic survey of the medieval Dublin region and by Slattery in his social history of late medieval Dublin, while Sparky Booker has deployed entries respecting debts to illuminate connections between native Irish and Anglo-Irish.Footnote 9 Compiled following a testator's demise, the inventory assessed the value of the household's moveable assets and any income due from debts owed or outstanding debts that required payment. From this were calculated the value of the testator's assets that were expendable for the benefit of their soul, thus one-third, two-thirds or the whole depending on whether they left a spouse or children or neither, following the convention of legitim. This is made explicit since many inventories include a ‘porcio defucti [the dead's part]’ entry.Footnote 10

The probate evidence extends chronologically from 1457/8 to 1483, but is mostly concentrated in the period 1471–8. Often, an inventory is drawn up in the name of a husband and wife, but the associated will relates to only one of the couple. In all cases, table 1 (below) uses the name of the will-maker as a shorthand to identify inventories. Eleven inventories can be identified with residents of the walled city of Dublin, including Archbishops Tregury and Walton and several merchants. Six further inventories, and possibly a seventh, are associated with the extramural parish of St Michan's, which included Oxmantown. Another three pertain to the extramural parishes of St Nicholas Without and of St Kevin, and four more to Glasnevin and Crumlin, villages just outside the medieval city. There are three inventories for Swords and one for the port of Malahide, both communities that might be thought of as having urban characteristics.Footnote 11 Forty inventories relate to rural locations and a further three carry no specific evidence of location, but may well be rural. It follows that at least two-thirds of the sample relate to persons from rural communities. Less than one in five inventories relates to persons resident within the walls of the city of Dublin, including the two archbishops (see figure 1 above). Booker uses naming evidence to show connections between the English of Ireland and native Irish, but her methodology suggests only a few inventories, all rural, were associated with native Irish.Footnote 12 It follows that the comparatively affluent population represented in the register were predominantly Anglo-Irish, exclusively so in the case of Dublin itself.

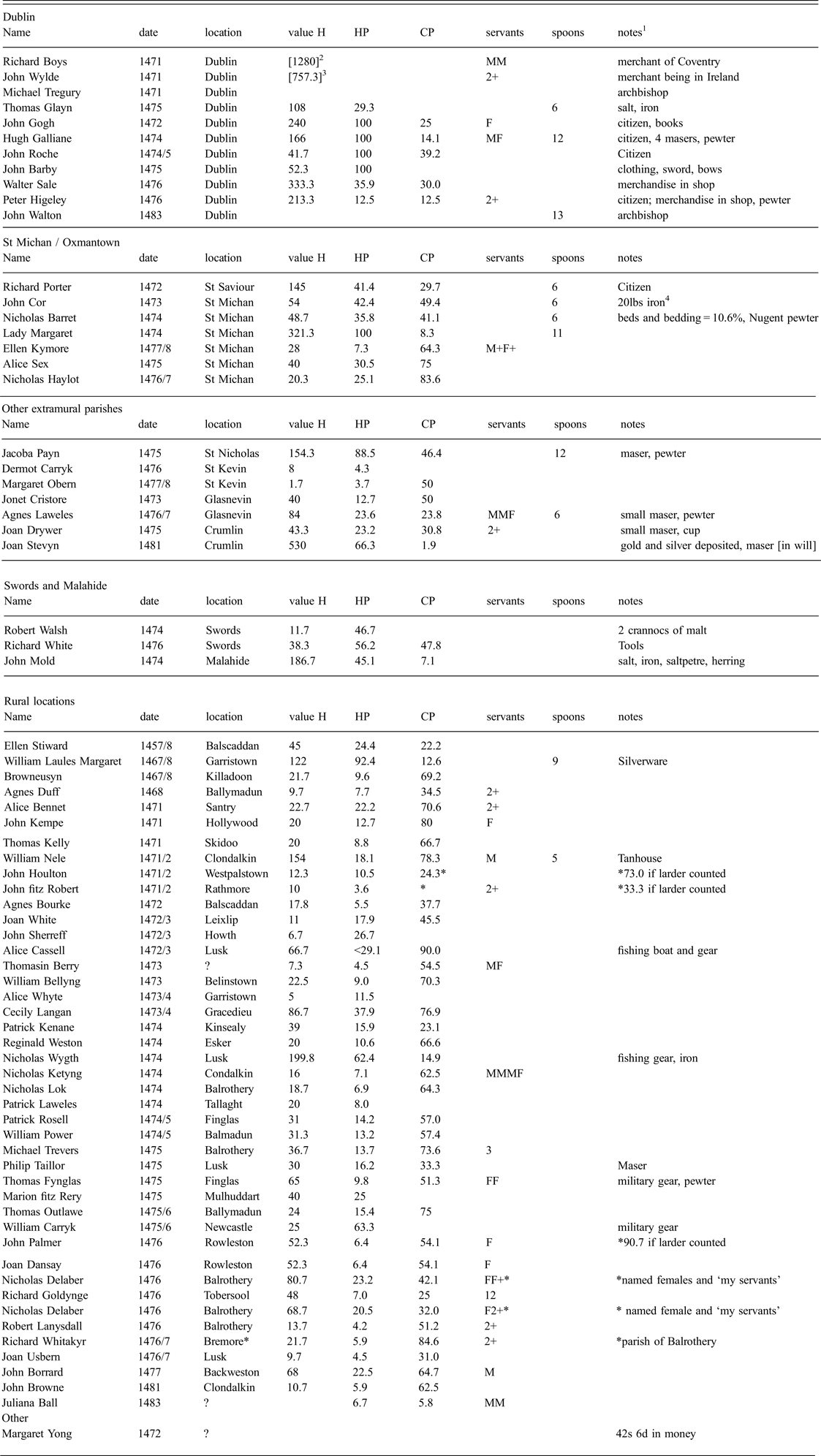

Table 1. Analysis of County Dublin Inventories.

Abbreviations

Value H = Total value of household possessions inventoried expressed in shillings

HP = percentage of household possessions to all inventoried possessions

CP = percentage of cooking-related utensils to all “inside” or household possessions inventoried

M = male servant

F = female servant

+ = or more

Source: Berry (ed.), Register of wills.

1 Notes record possessions and other observations considered worthy of remark.

2 Inventory includes only merchandise valued at £64.

3 Inventory includes only merchandise valued at £37 17s. 4d.

4 Household items valued at 20s. are noted at the end of the list of debts owing. There is an additional list of goods given to his daughter without valuation. These include cooking utensils, bedding, a tablecloth, towels, a further six silver spoons and a cow. It follows that goods in the house are undervalued.

Nearly all the inventories are complete, but vary in the information recorded. Two characteristics are especially noteworthy. Unlike the stray 1438 inventory of the prosperous Dublin baker, Richard Codde, many fifteenth-century inventories from England, three-fifths of inventories for the city of Valencia in the period 1370–1490 or nearly half the inventories from Gers, the County Dublin inventories do not distinguish separate rooms.Footnote 13 Most peasant homes were probably rectangular house-plus-byre structures without much internal division, but this would not be true of Dublin. Similarly, only a minority of rural inventories from the hinterland of Valencia or from the Gers sample record spatial divisions, unlike majorities associated with Valencia itself or Vic-Fezensac (Gers).Footnote 14 The second characteristic is that house furnishings are regularly subsumed as ‘instrumenta domus’ or ‘utensilia domus.’Footnote 15 This is not true of inventories from late medieval England or the remarkably detailed Gers sample. The absence of explicit spatial divisions, the bundling together of instrumenta domus, and, as we shall shortly see, the ordering and valuation of moveables, suggest the same appraisers were employed or that they followed an established brief.Footnote 16

Valuations are regularly rounded to pounds or fractions of a pound sterling or, more commonly, marks and fractions of a mark 160d. or two-thirds of a pound), a unit of reckoning. Thus, Nicholas Wygth of Lusk's cows were valued at 10s. (half of a pound), as were his sheep. His sea nets were valued at 40s. (£2), but the ship's gear at 13s. 4d. (1 mark), and the boat at 26s. 8d. (2 marks).Footnote 17 Other inventories value twenty lambs, three bullocks, a horse, pewter vessels, a brass pot, or household stuff, all at 3s. 4d. (a quarter of a mark). The sums of 6s. 8d. (half a mark), 5s. (one-quarter of a pound) or 20d. (one-eighth of mark) are also common. Valuations were not arbitrary: cows tended to be valued at around 5s. each and sheep at 4d. or 6d. each — which probably reflects whether or not they had been shorn. Pigs and, as might be expected, horses appear somewhat more variable in value. It follows that valuations are still useful indicators of relative wealth.

The inventories almost always begin outdoors, sometimes with the haggard — an enclosure for storing grain — but more often with livestock and crops.Footnote 18 This may reflect that most wealth usually comprised livestock, grain or merchandise rather than household goods. This pattern is not found in most later medieval English peasant inventories nor is it usual within the small sample from Gers. Possessions are often valued by type. Nicholas Wygth's inventory commences with livestock before moving to nets, ship's gear and a part share in a boat. Other than chests, wooden items, liberally recorded in the Gers sample, are little noticed whether outdoors or within.Footnote 19 Thus, farming equipment, predominantly made of wood, is almost absent. A plough coulter and wooden yokes noted in the prosperous agriculturalist Robert Lanysdall of Balrothery's will are missed from his inventory.Footnote 20 It may be that in some instances, farm equipment such as ploughs and carts have gone unrecorded because they constituted principalia, the more important possessions provided along with other fixtures and fittings included in the rent, and hence the property of the landlord.Footnote 21

Having begun outside, the appraisers progressed indoors, listing vessels made of brass or lead, iron, household utensils, and finally gold and silver (i.e. coin). Ceramics, intrinsically of little monetary value, are never recorded. Bedding, such as feather beds, blankets, sheets and coverlets, may also be under-recorded but is hardly noticed outside Dublin. Lady Margaret Nugent was unusually well provided with bedding. The chief justice and Dubliner, John Chever, left a canopied bed to the earl of Ormond, whom he had served when in London early in his career, but atypically, Chever's will is unaccompanied by an inventory.Footnote 22 John Roche possessed a pair of blankets and three sheets and John Barby, also of Dublin, possessed a pair of sheets.Footnote 23 An appended note shows Nicholas Barret of St Michan's parish had provided his daughter with bedding, but none is recorded in the inventory.Footnote 24 The picture that emerges of homes, particularly outside of Dublin, apparently devoid of furnishings beyond the most essential may in part be an optical illusion created by the sources. Nevertheless, the value of ‘household utensils’, particularly in the countryside, is often small. The very wealthy Dublin merchant Walter Sale had ‘utensils and ornaments of the house’ to the value of 100s. and his fellow Dubliners John Gogh and Richard Porter both had ‘household utensils’ valued at 40s. In contrast, the household goods of Richard White of Swords were valued at only 2s. Footnote 25 Valuations of 6s. 8d. or 3s. 4d. are common. Where chests are recorded, this tends to deflate the value of the ‘household utensils’. Lady Margaret Nugent's inventory, which unusually itemises numbers of household furnishings, tellingly has no ‘household utensils’ entry.

II

Probate inventory evidence from later medieval England and from the Gers region of south-western France suggests that distinctive models of consumption characterised different social groups. The ‘peasant’ model is characterised as prioritising investment outdoors in the form of livestock, grain and agricultural equipment. In comparison to the homes of artisans, who owned their own workshops and provided goods and services for profit, and merchants, their houses appear relatively spartan with limited investment in bedding or other furnishings and a focus on cooking utensils. Conversely, ‘bourgeois’ houses, where place of work and place of residence usually coincided, are characterised by a high proportion of investment on the domestic space, as opposed to the shop or workshop, and greater expenditure on beds and bedding than on pots and pans. Mercantile households shared the bourgeois concern to invest in domestic furnishings, particularly beds and bedding, but most wealth was invested in trade stock.Footnote 26 These differences in patterns of consumption between social groups are statistically measurable where valuations are given. They may represent wider western European patterns. This is suggested impressionistically from the small sample of rural and urban inventories from the Gers region of France which lack valuations, though three of the nine inventories from the small town of Vic-Fezensac follow a peasant model. Separate chambers for sleeping were much more common in late medieval Valencia than the surrounding rural hinterland, which likely also indicates greater investment in beds and bedding.Footnote 27

Utilising a like methodology, these patterns can be tested against the County Dublin sample in terms of relative proportions of investment in the domestic — such as cooking utensils and furnishings — and the external — livestock, trade goods, and tools. It is not possible to offer an analysis of relative investment between kitchen or cooking utensils and beds and bedding since though cooking and brewing vessels are regularly itemised, as already noticed, other households goods fall under the catch-all ‘utensilia domus’. Instead, the value of itemised brass (i.e. latten) cooking pots and pans are here compared to the assigned value of household goods to provide a proxy for cooking/kitchen to beds and bedding ratio.

The broad trajectory of peasant and bourgeois patterns of material consumption described for later medieval England and suggested for Gers in south-west France mirrors patterns observed in later fifteenth-century County Dublin. This is apparent from a comparison of mean ratios of values of domestic goods to all movables. For the rural sample, the mean is 17.8 per cent. If three cases with atypically high ratios (William Laules, Nicholas Wygth and William Carryk) are excluded, it falls to 13.7 per cent.Footnote 28 Although agricultural equipment is hardly ever noticed, horses, livestock, and various grains invariably are. For Dublin city, the picture is more complex. Three inventories display a mercantile pattern, but four others — including those of three citizens — only record household goods. The next part of our analysis will interrogate the evidence more closely by distinguishing patterns for particular types of settlement, commencing with Dublin, moving to the transpontine district of Oxmantown, then to other localities in the vicinity of Dublin, then to the boroughs of Swords and Malahide, and finally to other rural communities. Persons are assigned to each of these heads primarily on the evidence of where they asked to be buried.

Dublin's identity as a trading community with strong commercial ties across the Irish Sea is apparent from the sample, which includes both Irish merchants and, in two instances, men who were probably only temporary residents. Thus, the inventories of the Coventry merchant and sometime mayor, Richard Boys, resident in Dublin at the time of his death, and John Wylde, described as a ‘merchant, being in Ireland’, list only merchandise. The lack of recorded furnishings or cooking utensils suggest these men were only hosted in Dublin.Footnote 29 Boys appears more connected to Ireland. His inventory describes him as both ‘of Coventry’ and ‘remaining behind and staying in Ireland.’ His will made provision for a chantry in St Michael's, Coventry and referenced his property in and near Coventry, but he also owned a shop in Dublin and two apprentices named in his will may have been local lads since both have Irish surnames — Donnalli (Donnelly) and Martyn (Martin).Footnote 30 Wylde's will made provision within Dublin only, including a contribution to the work at St Audoen's, and named two Dublin merchants as his executors. Both men requested burial in the city's Dominican friary.Footnote 31

Peter Higeley's more characteristically mercantile inventory records large quantities of salt, iron and leather, implicitly his stock in trade. A citizen, he also possessed household utensils, including brass vessels and pewterware, worth over ten pounds, a classic mercantile pattern: only a minority of wealth was invested in domestic furnishings, but their overall value is still substantial. The same is true of the inventories of Walter Sale and Thomas Glayn. Though merchandise in Sale's shop was valued at £27, he possessed brass vessels, plate and household items worth some £17. Glayn's brief inventory includes salt and iron to the value of £13.Footnote 32

Of five further inventories of persons who requested burial in Dublin, four record only possessions within the house so offering limited evidence of occupation.Footnote 33 Three are described as citizens. John Gogh, a married man with young children, is likely the person appointed second baron of the Irish Exchequer in 1445 who performed legal services for Waterford and was still active in 1467.Footnote 34 His will shows substantial property in Waterford and a bequest of a missal to Christ Church Cathedral. His frustratingly brief inventory records unspecified books worth £2. Books are otherwise not noted within the inventory sample, nor much noticed in wills: two books of account are referenced in the wills of the merchant, Peter Higeley, and the lawyer, John Chever, and four books are described in Archbishop Walton's will.Footnote 35

The inventory of Hugh Galliane lists utensils for cooking and dining including pewterware, four masers, two silver cups and a ‘nut’ or cup made from a coconut shell. This is an atypical assemblage — nuts and pewter vessels are rarely noticed. Galliane's four masers, turned maple bowls often fitted with a silver rim, were together only valued at 16s., but no other inventory records more than one of these prestigious items.Footnote 36 Galliane's bequests of one of the masers to his wife and two pots with large rims to his daughter Joan could suggest these utensils were indeed for domestic use. However, the mention of debts owing to Galliane for pots suggests another explanation. Katherine Tanner owed 2s. 6d. for a vessel known from its shape as a bell (‘bellam’) and the tailor, John Morice owed 3s. for a pot (‘ollam’). Much of Galliane's rich collection of utensils may thus represent his stock in trade. Consequently the proportion of goods associated with the house rather than to trade may been inflated and would in fact correspond to the mercantile model.

The citizen John Roche's inventory records only household possessions valued at 41s. 8d.. Neither will nor inventory offer direct indication of Roche's occupation. Roche's own debts are considerably outweighed by debts owed. The roll call of his debtors is impressive: a former mayor, the vicar of Naas (County Kildare), a tailor who owed 8s. 4d., a man from the port of Drogheda who owed 9s. 10d. and Gerald FitzGerald, constable of Dublin Castle and heir to the earldom of Kildare, who owed £2 13s. 4d. (‘debet de claro iiij marcas’). Roche described his ‘cottage’ as above the east gate of the city, a strategic position to catch passing traffic. In addition to cooking pots and a small pan (‘parva patella’), his possessions unusually included a spit with two iron tripods.Footnote 37 This suggests that Roche was a cook with a prosperous clientele of visitors and residents who offered roast meats or poultry in addition to other cooked foods. Implicitly some of his regular clients were slow to pay. We may note also that Roche's household goods to all goods valuation is consequently overstated: the actual proportion would be in line with the artisanal model.

John Barby likely boarded in furnished accommodation; save for a pair of sheets valued at 2s., his inventory lacks both household goods and cooking utensils. It does, however, record several items of clothing including four gowns (‘juppas’) and a sleeveless tunic (‘colobium’), together with a sword and strap, and two bows. These last suggest that he served as a man-at-arms presumably associated with Dublin Castle.Footnote 38 At his death, 2s. of his salary was outstanding. The final Dublin inventory, that of Walter Sale, records unspecified merchandise in his shop together with debts, implicitly owed to Walter, valued at £27. ‘Domestic’ goods represent only some third of all his possessions by value. His inventory, however, is brief and atypically the debts owing to Sale have not been listed separately and individually. The laconic ‘mercemoniis’ could represent an artisan's stock in trade, but an entry in the city assembly rolls for 1461–2 usefully describe him as a merchant.Footnote 39

The Dublin inventories appear broadly to fit artisanal and mercantile models of consumption, though the evidence does not allow comparison of investment in beds and bedding to investment in the contents of kitchen or in cooking utensils. The cruder measure of the relative value of cooking utensils to all household possessions is available in only four instances, but these tend to be significantly lower than the equivalent proportion for rural locations. The highest proportion (39.2 per cent) is associated with John Roche whose cooking utensils were likely his tools of trade. The mean for the other three inventories is 23 per cent. This compares to an equivalent rural mean of 54 per cent.Footnote 40

Two further markers of difference between town and countryside relating to silver spoons and servants are, unlike the statistical measures, probably more culturally specific. In an English context, the possession of silver spoons is strongly associated with townsfolk, but they are rarely found in peasant homes before the late fifteenth century. This pattern is mirrored in the County Dublin sample, but not the small sample from Gers. Only four of forty rural inventories noticed silver spoons, compared to seven of the eighteen for Dublin and Oxmantown.Footnote 41 Servants may be noticed in inventories in respect of debts, presumably for outstanding wages or in wills as recipients of bequests. Servant-keeping was commonplace in northwest European towns and cities, but much less so in the countryside.Footnote 42 This also appears true of the County Dublin sample. Five of the nine Dubliners discussed above are documented to have employed servants, a higher proportion than the one in three individuals found within the larger rural sample.Footnote 43 This proportion is still noteworthy and probably reflects the relative prosperity of peasant families in the sample and the level of animal husbandry practised where live-in servants of either sex were an asset.

III

In order to explore whether bourgeois characteristics extended beyond the city walls, this section will explore fourteen inventories drawn from the vicinity of the walled city of Dublin. The inventories relate to an unusually mixed population. Six concern parishioners of St Michan's. A seventh requested burial in the Dominican friary of St Saviour also in Oxmantown, but there are additional reasons for surmising his locality. Oxmantown Green served as common pasture and there is archaeological and documentary evidence for fishing, tanning and retail in the later medieval period.Footnote 44

Ellen Kymore with her husband, John Bulbeke, principally grew grain: that in their haggard was valued at £10 and grain growing in the field at £5. They also kept three horses and some cows and pigs. Their debts included payments of 22s. for land rent and 12s. for wages for their servants. Household utensils were valued at 10s. which, together with brass vessels (18s.), gave a total value of domestic goods of 28s., only 7.3 per cent of all goods.Footnote 45 Although the equivalent means for Alice Sex and Nicholas Haylot are higher — 25.1 and 30.5 per cent respectively — they only modestly exceed the rural mean. Alice Sex and her husband Richard Bull had grain in the fields to the value of £4, but also two cows with calves and a pig. Haylot and his wife Anne Rede were even less affluent, having only £2 of grain between the fields and their haggard, though slightly more livestock including sheep.Footnote 46

The statistical measures suggest a bourgeois model in respect of the remaining St Michan's inventories of Nicholas Barret, Richard Porter, John Cor and Lady Margaret Nugent, the prosperous widow of Sir Thomas Newbery, a merchant and several times mayor of Dublin.Footnote 47 The proportional values of domestic to all possessions — 35.8, 41.4, 42.4, and 100 per cent respectively — exceed the rural mean. The cruder benchmark of cooking to all domestic possessions of 41.1, 29.7, 49.4, and 8.3 per cent respectively are below the 54.0 per cent mean for all rural inventories, but in the cases of Barret and Cor only modestly so. However, if we add the entry ‘in utilensibus domus’ appended at the very end of Barret's inventory, the domestic to all possessions proportion rises 50.5 per cent and cooking to all domestic possessions is consequently reduced. However, whilst the four inventories may show bourgeois characteristics, closer reading suggests that Lady Margaret alone is without ambiguities.

A section of Barret's inventory between the listing of debts owing and debts owed begins ‘memorandum quod hec sunt bona que dedit filie sue [note that these are the goods that he gave to his daughter]’. There follows a list of possessions transferred the previous Pentecost to Barret's daughter, Joan, perhaps by way of dowry provision. These goods are unvalued because no longer part of Barret's estate, but some, including the brass bell weighing 230lbs and the brass ‘patenam’ (pan) holding twenty gallons, were probably of significant value. Other possessions gifted include a cow, six silver spoons — implicitly additional to the six in the main inventory — bedding, a tablecloth and towels. These last represent possessions otherwise encompassed under the generic label of ‘household utensils’. Barret's household to all possessions valuation proportion would consequently have been even higher less than a year before his death, but the cow is of note. According to the inventory proper, Barret possessed grain in his haggard and a parcel of land under oats. He also kept some pigs. This modest investment in agriculture sits uneasily alongside his dozen silver spoons or his strikingly large quantity of brass vessels. Barret's cultural identity is also suggested by his testamentary provision for his funeral of 40d. for bread and ale together with a further 40d. for the purchase of wine and spices, which last are a quintessentially bourgeois affect.Footnote 48 Peasants provided bread and ale alone.

In addition to the possessions transferred to his daughter, a further memorandum of agreement between Barret and his sons John and Thomas concerns real estate. It provides that Barret's widow, Joan, have their house and his daughter, also Joan, be provided with £10 of rent income for the house or alternatively ‘out of the rent of the old hall of Sir Edward Howet’. Thomas Barret was to inherit property in Finglas. The debts owing to him give further clues. Twenty-four debtors owing a range of debts, but mostly of several shillings, are recorded. Some debts are simply for sums of money, but many are said to be in relation to quantities of grain, some in relation to silverware including a silver girdle and a silver cup, and in one instance a crannoc of salt. These are mostly debts incurred on borrowing against security. In the case of the silver cup, the silver girdle, the silver spoon and the silver ring together with a pair of beads, the debt is described as being ‘super’ or ‘on’ the named item. In other instances, the debt owed was stated to be a quantity, usually an acre or acres of wheat. Edmund Walsh's debt, for example, was said to concern three acres of wheat and barley worth 13s. 4d., but additionally ‘unam acram frumenti in pigner[agium] per iijs’ — that is an acre of wheat in pledge for 3s. Barret, thus, lent money to a variety of borrowers including peasant agriculturalists, a fisherman, a priest and a couple of women including the abbess of St Mary de Hogges. In return, they promised payment in the form of crops or pawned items of value to be redeemed later. The 12s. in silver noticed in the main part of Barret's inventory probably represents ready cash to make loans and some of his silver spoons may represent unredeemed pledges. Barret was, thus, a landlord and pawnbroker/moneylender as much as an agriculturist.Footnote 49 Moneylending is not specifically an urban occupation, but it is an important service trade that may periodically have drawn country folk into Dublin

John Cor's inventory also presents ambiguities. Besides 40s. worth of grain in his haggard, Cor possessed five cows, five sheep and three pigs. Such, albeit modest, investment in agriculture sits uncomfortably with membership of the city's franchise or his possession of six silver spoons, a girdle studded with silver, and a drinking vessel [‘craterem’] valued at 6s. 8d. Together with the value of brass vessels and the ‘instramenta domus’, these explain a household to all goods proportion well above the peasant mean. There is little more that can be gleaned about Cor. He appears to have died childless and so entrusted his widow, Joan Alleyn, the task of disposing of half of his moveable goods for the benefit of his soul. Besides generous provision of two marks (£1 6s. 8d.) to cover expenses ‘circa corpus meum [around my body]’ on the day of his burial, his only specific bequests were to his parish church, the priest and the clerk. The absence of recorded debts or of named beneficiaries denies any window onto the socio-economic networks within which Cor operated.Footnote 50

Similarly problematic is the inventory of Richard Porter. His possible association with Oxmantown is surmised not so much by his choice of burial in Dublin's Dominican friary, which suggests spiritual affinity to the order rather than the locality, but by the very ambiguities of his inventory. Some possessions are characteristically peasant. He owned seventeen cows and 100 sheep besides a quantity of grain, an investment in agriculture that exceeded many rural agriculturalists. In his will, he made bequests to the churches of Castleknock, Clonsilla and Mulhuddart to the north-west of the city, which might suggest he held land there, even though his residence actually lay beyond Oxmantown. Other possessions are more characteristically bourgeois. His inventory itemises not only brass pots, but two pans (patellae), three spits (verua), in addition to gold, presumably coin, silver spoons, and ‘household utensils’ valued at 40s.Footnote 51 The cooking utensils suggest a much wider range and sophistication of cooking, including roasting meats, than the ubiquitous pottage suggested by the possession of only one or more brass pots. The rural inventories in the sample invariably value ‘household utensils’ at substantially lesser sums. Porter's inventory, thus, differs from that of most other peasant agriculturalists.

None of the Oxmantown inventories appear to relate to merchants or artisans evidenced by their tools or stock in trade, though Lady Margaret Nugent was a merchant's widow. Three represent characteristically peasant households, but all bar Lady Margaret's were engaged in agriculture to some degree. Richard Potter, who may have lived beyond Oxmantown, was indeed a substantial agriculturalist, but John Cor and Nicholas Barret hint at a more complex picture. Barret was a moneylender and landlord; agriculture could not have been his major source of income. Cor was a freeman of the city, though the nature of his livelihood surely cannot be explained by his modest agricultural interests. It is tempting to suggest that we have evidence here for a suburban economy in which for some agriculture might supplement other activities, but was not the sole or even the primary means to a livelihood.

A further, if slightly arbitrary group of seven inventories was chosen to explore how far suburban characteristics are replicated in other locations neighbouring the walled city. It comprises three inventories from the suburban Dublin parishes of St Kevin (Dermot Carryk and Margaret Obern) and of St Nicholas (Jacoba Payn), and two each from Glasnevin (Jonet Cristore and Agnes Laweles) and from Crumlin (Joan Drywer and Joan Stevyn). Of these, both from St Kevin's parish and, less markedly, that of Jonet Cristore from Glasnevin, had domestic proportions by worth below the rural mean.

Jonet Cristore and her husband Geoffrey Fox appear prosperous peasant agriculturalists with at least thirty acres of land devoted to grain production, a flock of some forty sheep and lambs, as well as cows and pigs. By her will, Jonet made two bequests each of three and a half yards of cloth, probably of her own weaving. No servant is noticed.Footnote 52 Dermot Carryk of St Kevin's parish likewise held at least thirty acres of arable together with sheep, cows, five horses and a pig, but his household goods were valued at only 8s. He owed £1 5s. 4d. in rent.Footnote 53 Much more modest were Margaret Obern's possessions. Also of St Kevin's, she had little over four acres of arable, a cow and eight sheep. The only household goods noticed were a pan worth 10d. and a chest worth 1s. Neither husband nor children are mentioned in her brief will.Footnote 54 On the anecdotal evidence of these two last inventories then, the parish of St Kevin appears quintessentially agricultural.

The remaining four persons within the sample show characteristics associated with an urban or bourgeois context. Jocoba Payn, together with her husband, John Kyng, and the widow, Joan Stevyn, possessed high proportions of domestic goods by value (88.5 and 66.3 per cent). Payn also owned a dozen — presumably silver — spoons valued at 20s.Footnote 55 Agnes Laweles and her husband Geoffrey Fox likewise owned six silver spoons together with a maser and a horn, accoutrements more often associated with bourgeois society. Joan Drywer similarly possessed a maser and a cup (‘craterem’). Laweles and Drywer both kept servants: Laweles and her husband owed payments to two named male servants and one female, Margaret Laweles, so presumably kin. Drywer similarly owed money to ‘her servants’ (‘servis suis’).Footnote 56

Slattery credibly identifies Jacoba Payn as a brewster and innkeeper.Footnote 57 The inventory, shared with her husband, records a range of household utensils entirely lacking from most other inventories. Most relate to brewing, cooking, drinking and dining. These will be discussed in more detail later. Access routes are common locations for inns that might accommodate travellers and Payn's house in the Dublin parish of St Nicholas Without the Walls was probably located on St Patrick's Street, a principal route into the city through St Nicholas's Gate. All point to Payn and her husband running a hostelry closely tied to Dublin and essentially urban in nature.

The Crumlin widow Joan Stevyn had grain worth £8 in her haggard and sixteen acres of land given over to growing wheat and barley. She possessed seven horses, but her sheep and pigs were valued at only 5s., suggesting modest numbers. Besides brass vessels, her household utensils were worth only 6s. 8d. No debts are recorded and her will makes no notice of servants, but suggests that she was living with her son and heir, John Mastoke, at the time of her death. She also mentions another son, Patrick. Thus far, the Stevyn-Mastoke household conforms to a peasant model, but the inventory includes an additional clause. This reads: ‘Item, the said Joan has in gold and silver [presumably coin] deposited with Agnes Wodbon, of Dublin, married woman [‘mulierem’], for safe keeping, £26 13s. 4d.’, a sum nearly twice the total value of her other goods.Footnote 58 Her unusually detailed associated will provides more detail. Joan was evidently a landowner as she left all ‘my messuages, lands, tenements, rents, and services’ in Crumlin to her son John. She bequeathed a maser with a silver gilt band, said to be in the possession of her younger son, Patrick, to St Mary de Hogges, the Arroasian nunnery located to the east of the walled city. She provided that possessions other than the money with Agnes Wodbon be equally divided between her sons. All her (unspecified) possessions, implicitly comprising or at least including the money, were to go to John. Unexplained is how this was in her possession in the first place or why Wodbon had custody. The will of Joan Drywer, the other Crumlin resident, notices her two daughters, but no husband. Aside from her cup and maser, Drywer's inventory records quantities of grain, two cows and four horses, a characteristically peasant pattern.

The final inventory within the subset is that of Agnes Laweles of Glasnevin. As noted, Agnes and her husband Geoffrey Fox possessed spoons, a maser, a horn and small quantities of pewterware. They also had brass pots worth 20s., (unspecified) household utensils also worth 20s. and they employed servants. Agnes's will evidences some additional household items. She left her daughter, Joan, a cupboard, a chafing dish and a kneading trough. Her other daughter, Rose, received in addition to her maser, horn and pewterware, a mash tub used in the brewing of ale. Implicitly the household brewed and produced its own bread, work that may in part have fallen to their female servant. Much of their wealth was invested in agriculture, including thirteen cows, thirty sheep — the couple also employed a shepherd — and eight horses. They had grain in their haggard and eighteen acres of arable. The inventory also records forty yards of linen cloth valued at 10s. This may represent Agnes Laweles's own handiwork.Footnote 59 The couple were evidently substantial agriculturalists whose labour needs readily explain their employment of three servants and a shepherd. Their prosperity may in part explain their maser and pewterware.

On balance, only St Michan's parish, both a transpontine extension of Dublin's walled city and an area of cultivated fields that lay beyond, contained suburban elements. The very proximity of Oxmantown to the walled city and its markets may have both facilitated and encouraged emulation of bourgeois culture.Footnote 60 The inventory sample suggests that many, perhaps most, inhabitants had agricultural connections. Some were essentially peasant agriculturalists or no doubt labourers, but some also had interests that tied them to the city. The ‘other extramural parishes’ sample is small, but still permits some deductions. Jacoba Payn's hostelry, located in St Nicholas Without parish, is very much an extension of the walled city; its clientele were likely both visitors to Dublin and locals. The Laweles-Fox household combines both peasant and bourgeois characteristics. It is, thus, tempting to see analogy with Oxmantown, but this may simply be an especially affluent peasant family. The other Glasnevin inventory, the two Crumlin inventories, pace the anomaly of Joan Stevyn's deposited specie, and the two from St Kevin's parish, despite its proximity of the walled city, are characteristically peasant. Thus, though the city of Dublin extended beyond its walls, slightly more distant localities such as St Kevin's parish or Crumlin show little apparent influence of bourgeois culture.

IV

The sample for the boroughs of Swords and Malahide is frustratingly tiny. The two Swords households demonstrate comparatively high proportions of domestic possessions to all possessions — 46.7 per cent for Robert Walsh and 56.2 per cent for Richard White. Such proportions could represent artisanal households. Save for a horse (‘affrum’), White's inventory lacks all reference to livestock or grain, but does include ‘my tole’ (tool) valued at 4s. 4d. and six large augers or drills (‘penetralia’). He also possessed a cart and the body of a cart. The implication is that White was a cartwright and the cart and the body of a cart were products of his craft. The 40lbs of yarn recorded probably represents his wife's labour.Footnote 61 The lengthy list of his debtors included six persons from outside Swords and sixteen residents. Most debts were for sums of several shillings, but John Gallane of Swords owed £2 8s. 7d. These are likely unpaid debts from work done by White. Total debts amounted to £10 11s. 7d., considerably in excess of White's total possessions. White then was likely an artisan, but his craft was not specifically urban.Footnote 62

Robert Walsh's inventory and will are less informative. The inventory records a total valuation of merely £1 12s. 4d., though the itemised goods add up to only £1 5s., a shortfall probably explained by the accidental undervaluation of his six cows. He also possessed ten sheep and two crannocs (measures) of malt. I have counted the malt as for brewing and hence ‘domestic’, but it may be a product of grain production. On balance, Walsh looks to have been a peasant agriculturalist of modest means. He was owed several small debts mostly of a few pence or a couple shillings totalling 11s. 7d., but he owed William Algere of Swords 5s. 8d.Footnote 63

According to his inventory, John Mold of Malahide kept a few pigs and sheep and had grain worth £2 in his haggard. He apparently traded inter alia in iron, herrings and salt. From their quantities — the iron weighed half a ton — these were evidently stock in trade. As Peadar Slattery has observed, Mold's debts included sums to two Conwy persons and a John Baly of Bristol, suggestive of trading ties to North Wales and Bristol. It is, however, a record of his 1468 sailing to Chester on the Trinity of Malahide that confirms his interests across the Irish Sea.Footnote 64 Mold also possessed three fishing nets, £6 13s. 4d. in coin and, in addition to a vessel of brass and one of lead, household items valued at 40s., a domestic to all possessions proportion of 45.1 per cent.Footnote 65 If the unusually large amount of coin were to be classed as part of the mercantile business, then this proportion would be considerably lower. Even without the coin, the cooking to all household proportion would still only be 25 per cent, well below the rural mean, but in line with the pattern found in Dublin inventories.

This tiny sample can be at best only suggestive. One of the two Swords inventories appears artisanal, but hardly suggests that Swords was characteristically urban. Richard White was probably a cartwright who made farm equipment, not specifically an urban craft. Robert Walsh looks much like many other peasant agriculturalists within the inventory sample. Only the Malahide merchant, John Mold, hints at the port constituting an urban community. Merchants are quintessentially an urban phenomenon and the two pounds’ worth of household utensils (‘instrumenta domus’) represents a comparatively high investment in the furnishing of his home. His wife Maud Olifer may have augmented the household income by brewing, suggested by the leaden vessel. His possessions also show that agriculture and fishing were further sources of income. This reflects the way most households depended upon a range of economic activities to get by, but may qualify our initial suggestion of Malahide's urban identity.

V

There are forty-three inventories and accompanying wills associated with rural settlements not already noticed. Unusually, the inventories of Juliana Ball, for whom no will survives, and Thomasin Berry cannot be tied to a location, but they show rural, peasant characteristics. I have excluded the inventory of Margaret Yong, which records only a sum of money. Her will associates her with a parish dedicated to the Virgin, a parochial dedication not found in Dublin.Footnote 66 Most inventories demonstrate peasant characteristics. Proportions by value of domestic to all possessions are low: thirty-six (83.7 per cent) had a proportional value of 25 per cent or less.Footnote 67 Similarly, where this can be calculated, the ratios of the value of cooking utensils — usually brass pots — to all domestic movables are comparatively high. Most rural inventories notice grain in the haggard or the fields, and numbers of pigs, cows, horses, and sheep. Goats and poultry, however, are absent despite the latter's likely ubiquity.Footnote 68 So commonplace was the possession of sheep that the appraisers of the goods of Michael Trevers of Balrothery recorded ‘oves non habet [he does not have sheep]’ lest it be thought that they had been careless.Footnote 69

The contents of the house are generally very limited. This perhaps represents a cultural predeliction that saw livestock and grain as the most important possessions, hence the practice of beginning rural inventories ‘outside’ before finally moving indoors. Such a pattern is found in the memorandum rolls from nearly two centuries earlier and a similar ordering is common in later medieval English escheators’ lists.Footnote 70 Household possessions mostly comprised brass pots, including ‘bells’, and sometimes pans. In three cases, the contents of the larder (larderium) are valued. Chests, coffers and silver spoons are uncommon. Bedding is not specified, though by her will Joan Dansay of Rowleston left a blanket to her servant Margaret.Footnote 71 This is further indication that some household goods including bedding, wooden and ceramic cooking utensils, wooden eating utensils, and some furniture — all items regularly itemised in the much fuller inventories from the Gers region — may disappear under the generic ‘household utensils’ heading. Fixed items built into the fabric of the house such as beds would likely go unrecorded as would any furnishings provided as principalia within the rent.Footnote 72 Later medieval English evidence might suggest such principalia comprised trestle tables and some basic furnishings such as stools, but also brass pots, the one item invariably included in the County Dublin inventories.Footnote 73 Household furnishings were, thus, probably not as limited as the inventories imply, but still basic given the generally low values found for ‘household utensils’.

Rather than discuss the majority of inventories that, using the statistical indicators and more specifically from the types of possessions recorded, satisfy a peasant model, I will focus on the small number that less obviously conform. Later medieval English probate inventories suggest that the presence of silver spoons was often an urban characteristic, at least before the late fifteenth century.Footnote 74 Silver spoons, which are unlikely to be subsumed as ‘household utensils’, are found in the County Dublin sample, but only four of the forty-three rural inventories record spoons. These four inventories, three of which otherwise statistically show peasant characteristics, merit further scrutiny. William Nele of Clondalkin was a prosperous agriculturalist with horses, cattle, pigs and eighteen acres under wheat, barley and oats. He possessed some relatively valuable brass vessels, including four ‘bells’, but nearly a third of his wealth was invested in a tanhouse. Nele, thus, combined agriculture with rural industry. His five spoons, alongside his four chests and a coffer, signal his comparative wealth.Footnote 75 Michael Trevers of Courtlough — the man with no sheep — grew grain and owned cattle, pigs and nine horses. Only three other rural households record more horses. His will notices two lead vessels not mentioned in the inventory. Seven different people, some local, owed him money ranging from 1s. 6d. to £3 1s. 8d., so he may also have lent money; his spoons may have been acquired as pledges, but they may simply reflect his wealth.Footnote 76

Personal wealth may also explain Richard Goldynge of Tobersool's ownership of a dozen spoons worth 16s. Goldynge's livestock comprised cattle, pigs, a few sheep and a remarkable sixteen horses — only Archbishop Tregury possessed more. He held fifty-four acres of arable, though his household utensils were valued at only 20s. Footnote 77 In peasant households, then, silver spoons were uncommon, but where found they tend to signify particular wealth: Nele, Trevers and Goldynge were three of the four wealthiest persons within our rural sample. The fourth case is entirely anomalous. William Laules of Garristown owned two cows and two bullocks, but no other livestock, no haggard and no grain are noticed. However, he owned a small, but extraordinary assemblage of silverware that might otherwise grace an aristocratic household. Besides silver spoons, there was a silver cup valued at 40s., a silver girdle worth 20s., and a silver scutcheon [‘scotcheon’] valued at 26s. 8d. Garristown seems an implausible location for a silversmith. The inventory omits record of debts, so it is just possble that Laules traded as a moneylender or pawnbroker. His will provides no further clues.Footnote 78

Other atypical possessions may also be noticed within the rural sample. Uniquely within the rural subset, Philip Taillor of Lusk owned a maser. Nothing else about Taillor's inventory or his will suggests he was anything other than a moderately substantial peasant agriculturalist with the usual mixture of livestock and grain.Footnote 79 Two further Lusk inventories (Cassell and Wygth) are of interest because they give evidence for fishing alongside agriculture. The chapelry of St Maurus, Rush within the larger parish was a port and fishing community known ‘for the great quantities of ling … taken and cured by the inhabitants’ since the sixteenth century, but implicitly earlier.Footnote 80 The probate evidence shows that herring were also caught, hence the sea nets that are noticed. Alice Cassell, the wife of John Calff, was presumably a resident of Rush since she left ‘unum peplum’, likely a veil or cover, to the image of the Virgin in the chapel. The couple had some sheep, pigs, cows and a single horse, but also possessed a small boat (‘naviculam’) valued at £4 or slightly more than a third of all goods by value, fourteen sea nets, and gear worth 2s. 8d. ‘Household utensils’ are valued at only 6s. 8d. The inventory also records a number of debts amounting to nearly £4. Cassell and her husband evidently combined keeping livestock with fishing, a peasant cultural model common enough in coastal communities.Footnote 81

Nicholas Wygth also remembered St Maurus’ chapel and combined agriculture and fishing. He owned thirty sheep, three cows and a pig in addition to grain in the haggard and possessed a dozen sea nets (‘retina marina’), a quarter share of a skiff (‘unius scaffe’), and associated gear (‘suppellectilia navis’). He was owed eighty hooks ‘of lente takyll’ (Lent is the season of greatest demand for fish; the tackle was perhaps used for ling). Wygth's interests evidently extended beyond these twin activities: his inventory records twelve stones of iron and, more significantly, gold and silver, implicitly coin, to the value of £8. This is an unusually large amount of specie to keep, particularly as agriculturalists tended to invest any surplus in livestock or equipment. As in the case of Nicholas Barret of St Michan's parish, the clue may lie in the list of debts owing. Twenty-five named persons are recorded, a few in relation to more than one debt. Besides the fishing hooks, most comprise small money sums or quantities of grain. In two instances, the debt was for a stone of fimble hemp used for spinning into fibre to be woven into hempen cloth used for sails.Footnote 82 The number and precision of debts suggests the appraisers followed a ledger or account book. Wygth thus appears to have combined pawnbroking with fishing and agriculture. Despite his £8 in ready cash, his ‘household utensils’ were valued at only 10s. In essence, this looks like a peasant household.Footnote 83

Our final category of uncommon possessions comprises arms and fighting gear. The inventories of William Carryk and Thomas Fynglas merit attention. Carryk of Newcastle Lyons does not fit a peasant model since only a third of his movables by value were associated with agriculture. He had one acre of wheat and two of oats. He also had loose oats worth 4d., but no livestock other than a horse. His ‘domestic’ goods were even more minimal. Besides a chest valued at 1s., he had ‘household utensils’ worth 2s. and no brass pots. What Carryk did possess was a sword, a doublet of defence (‘deploidum defensibilem’) and a hauberk or shirt of mail probably worn over the padded doublet of defence.Footnote 84 Carryk then was no peasant agriculturalist, but, like the Dubliner John Barby, a man at arms. Unlike Barby, he was not an employee, but the holder of a castle — a tower-house in modern parlance — of which there were several at Newcastle Lyons: his will refers to ‘my castle and my chief residence’ with other land and properties to his name as well.Footnote 85 Modern scholarship understands such structures as domestic as much as defensive. Carryk's military gear and relative paucity of household goods might here suggest that defence was to the fore as befitted the circumstances prevailing at the time of his death in 1477.Footnote 86

The inventory of Robert Fynglas and his wife Rose FitzEustace of Finglas records two doublets of defence, a third still being made and a helmet (‘galeam’). The name FitzEustace may provide a clue to the level of society represented here since Rose was likely a member of one of the most important Anglo-Irish families. Robert Fynglas of Finglas was himself apparently from an established family that subsequently rose to prominence in the law.Footnote 87 The couple enjoyed substantial livestock including fourteen horses (a dozen draught horses [‘afros’] and two ‘equos’, presumably riding horses), cows, pigs and sheep, comprising thirty-three sheep and nineteen lambs. They had grain worth £20 in their haggard and forty acres under wheat and barley. The household is distinguished from those of other especially prosperous peasant agriculturalists by the military accoutrements, but also by six pewter vessels (‘scutellas plectri’).Footnote 88

VI

Our analysis privileges broader patterns of consumption between town and country. The laconic nature of most inventories in respect of household furnishings makes it very hard to offer much by way of analysis of the cultural consumption of textiles, furniture beyond chests, clothing and the like. In contrast, the possession livestock other than goats and poultry appears very consistently recorded, hence the appraiser's comment about the man with no sheep. The same is true of grain. This points not just to the economic significance of such possessions, but their cultural importance in a predominately mixed agrarian economy, a suggestion reinforced by the ordering of inventories starting outdoors. Whereas wooden, ceramic and textile possessions are scarcely noticed, metal goods appear generally well recorded: quantities of iron, silverware, including spoons, pewterware, tin (in one instance), lead and vessels made of lead, but especially brazen vessels are regularly found.

The use and significance of the full range of lead and brass vessels, especially the so-called bells, merits further research. Berry notes ‘the pecia co-operta, or covered piece, was familiarly known as a “bell”’, but this appears of little help here. An unreferenced work describes the medieval use of bell-shaped brass, rather than the more usual ceramic, fire-covers or curfews to keep the embers of the fire glowing when not in use. Iron curfews are noticed in an early fifteenth-century inventory from Marseilles.Footnote 89 Medieval ceramic curfews from the Netherlands, which were bell-shaped and had a hook at the top to allow suspension above the fire, are termed ‘vuurkloken’ or fire bells.Footnote 90 This offers a more convincing explanation. Vessels of lead may be associated with brewing, though brass vessels might also be used.Footnote 91 Brass vessels may have been used for food storage, including of milk, and in butter making.Footnote 92 Brass cooking utensils are hardly specific to the region, but the frequency and the care with which brazen utensils, including ‘bells’, are noticed within otherwise rather laconic documents, and hence the proportion of wealth so invested, appears culturally distinctive. No doubt numbers of the larger vessels represented cauldrons, a versatile cooking vessel that has deep and symbolic roots in Irish culture.Footnote 93

Unlike wills, the inventories tend to offer limited opportunity to observe gender difference. In several instances where an inventory is associated with a woman's will, the inventory is specifically attributed to both husband and wife. The inventories of both Peter Higeley and Richard Porter specify that they represent the property of husband, wife and their children. It is apparent that the inventories record joint assets held equally by husbands, wives and children; a significant purpose of the inventory was to determine the value of assets that might be devoted for the benefit of the deceased's soul following the conventions of legitim. One slight exception to this is the inventory of Ellen Stiward, a married woman, which atypically commences by listing a set of beads, a ring and a box, implicitly items personal to Ellen, and which she specifically bequeathed to her daughter by her will, before moving to a conventional listing of grain, livestock, and household utensils, though two small fish pans are described and a further set of beads, five rings, and a brooch are also listed.Footnote 94

Two exceptionally informative inventories merit particular attention — those of Lady Margaret Nugent and Jacoba Payn. Both were located just outside the walled city, but very much reflect the rich material culture that the city could provide to those with the necessary resources. Lady Margaret, the wealthy widow of a leading Dublin citizen, possessed only household items, but her array of possessions speaks to an haute bourgeois identity. These included silverware, a feather bed and, uniquely within the County Dublin collection of wills and inventories, several cushions.Footnote 95 It is possible that cushions were otherwise subsumed under ‘household utensils’, but these were part of an expensive set of decorative furnishings for a bench that signals, status, comfort and perhaps a concern to entertain visitors. Only the two archbishops are also associated with feather beds, an indication of their high cultural value. She also possessed a bed of buckram with three curtains of the same material and coverlets of Arras tapestry, a high-status material that was implicitly imported.

Other markers of status are found in her collection of silverware and jewellery. She possessed a coconut shell encased in silver, an especial indicator of social aspiration and sophistication at this period.Footnote 96 Another quintessential marker of status was her silver salt cellar. Archbishop Tregury's is the only other inventory to record these. Lady Margaret's possession of two sets of coral prayer beads and a small brass holy water vessel also speak to contemporary devotional fashions. Katherine French, writing of a London merchant's widow from eighteen years later, further suggests that besides the efficacy of holy water, the juxtaposition of coral beads and a ‘nut’ may have been to draw upon their supposed healing powers.Footnote 97

Both Lady Margaret and the Kyng-Payn household possessed pewter vessels. Pewterware, commonly found in English bourgeois households by this period, was uncommon and a couple of examples are rural. Agnes Laweles of Glasnevin, for example, had pewterware to the value of 3s. 4d. and also bequeathed three pewter dishes and a pewter platter to her daughters Rose and Joan respectively.Footnote 98 There is some overlap with the few households which also possessed masers, another marker of status and bourgeois sociability. None, however, approached the 16s. valuation of the Kyng-Payn maser which suggests this was an especially prestigious object perhaps used for communal drinking of ale.Footnote 99 This would accord with the indications that the household supported a hostelry. Several possessions relate to brewing, notably a brew pan and wooden brewing vats; to drinking, including three pewter pint pots, and to the preparation and consumption of food, including roast meats. There are five spits — an item otherwise scarcely found — plentiful cooking utensils, six candlesticks, suggestive of entertaining after dark, a chafing dish for keeping food warm, and seven quarters of beef. It is less apparent how far the more modest quantities of bedding and napery recorded were also for the use of customers, but this was clearly a well-provided establishment that provided for a clientele familiar with bourgeois values or aspired to the same.

VII

The County Dublin inventory collection allows broad distinctions between peasant, bourgeois, and mercantile patterns of material culture to be discerned both from necessarily crude statistical data and also through material cultural evidence. For example, silver spoons are noticed in eight of eighteen Dublin — including the parishes of St Michan and St Nicholas Without — wills and inventories (44.4 per cent), but in only five of fifty-two (9.6 per cent) other inventories, including Malahide and Swords. These five instances all relate to unusually prosperous rural households. The broader peasant, bourgeois and mercantile patterns of investment maps well onto what might be expected from other sources. Dublin shows up as a busy commercial settlement with trade links across the Irish Sea. Although the city inventory sample is small, it includes a professional cook and a well-stocked hostelry just outside a city gate. The concentration of silverware, pewterware, masers and even a couple of coconuts, as well as evidence for beds and bed furnishings, reflects not merely the affluence of some households, but the availability of luxury goods, some imported, but some probably manufactured locally. The ready presence of servants also reflects the city's economic activity and its capacity to attract migrant labour. There is only modest evidence, most apparent in St Michan's parish, for a pattern of consumption that could be characterised as suburban. Neither Swords nor Malahide demonstrate much evidence for developed urban economies, though our samples are vanishingly small. John Mold of Malahide may well have traded as a merchant and had links to Bristol and Conwy, but his livelihood also depended on agriculture and fishing.

Most inventories reflect an agrarian economy and a predominantly peasant cultural model of consumption that mirrors the findings of the monumental Dublin region survey by Murphy and Potterton. Mixed husbandry appears widespread. Most households possessed one or more cows, the mean herd size being six and the largest comprising twenty. Nearly as ubiquitous were pigs, sheep and horses. Holdings of pigs mirrored those of cattle. The largest recorded sheep flock was rounded to 100, but the mean was a quarter of that and numbers of peasant agriculturalists possessed only a dozen or fewer. The mean number of horses was six and only a handful of households had nine or more. Other livestock and poultry are not recorded. Grain production was equally ubiquitous. Wheat is most frequently noticed, followed by oats and then barley.Footnote 100 There is limited evidence for rural craftwork or rural industry: brewing and flax spinning were probably women's activities, a tanhouse is noted at Clondalkin and fishing is evidenced at Lusk. What the probate evidence demonstrates, however, is how comparatively prosperous a small number of peasant agriculturalists were. In line with the prevailing cultural model, this is reflected in the quantity of livestock, particularly horses, and to some degree in their employment of servants. A few peasant agriculturalists possessed silver spoons, but only the Laweles-Fox household of Glasnevin even begins to show significant bourgeois tendencies. Despite the at times frustratingly laconic nature of the inventories in the County Dublin collection, a picture nevertheless emerges of the region's society and material culture at the end of the middle ages. It tends to confirm the value of inventories as a source to distinguish peasant and bourgeois patterns of consumption and also allows useful comparison with other regions of Europe where similar evidence survives.