Introduction

Scholars have been focusing on the influence of emergencies on intergovernmental relations (IGRs) in multilevel systems, combining the studies on IGRs to those on the politics of crisis. During crises, centralisation of processes typically occurs (Peters, Reference Peters2011). In some decentralised systems, crises may promote greater coordination and cooperation between levels of government, with more or less lasting effects, while in others they may lead to more conflictual policymaking (Schnabel and Hegele, Reference Schnabel and Hegele2021; Steytler, Reference Steytler2021; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Kuhlmann, Laffin and Wayenberg2022).

The architecture of the Italian multilevel system and its IGRs, together with the significant impact of some recent crises in the country, make Italy a favourable context in which to test IGRs-related theories and hypotheses. During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, policymaking processes were centralised, and subnational actors marginalised from them (Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021; Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini and Lippi2022). These trends seem to have been more pronounced during the technical government led by Mario Draghi (2021–2022), than during the Conte II government (2020–2021) (Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021). Moreover, scholars argued that the involvement of technicians and experts in the policymaking depoliticised decisions and caused concerns in terms of accountability during the health crisis (Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020; Capano, Reference Capano2020; Ieraci, Reference Ieraci2020, Reference Ieraci2023; Galanti and Saracino, Reference Galanti and Saracino2021). The paper explores the Italian IGRs in times of crisis and in particular the hypothesis that technical governments lead to a greater degree of centralisation in decision-making in comparison with political ones. To support this hypothesis, the paper compares the state of Italian IGRs in two different types of crises that severely affected the country: the financial-economic crisis (2008–2013) and the pandemic (2020–2020), which both had an international impact. Yet the two crises were characterised by different policy areas, with the former crisis being mainly economic and the latter health related. This aspect enables the evaluation of IGRs in two distinct crisis contexts, characterised by varying levels of autonomy and authority of the Italian regions, which is higher in the health policy area and consequently resulted higher during the pandemic, because of the regionalization of healthcare and services. Moreover, in both crises, there was an alternation between a political and a technical government: the Berlusconi IV government (2008–2011) was followed by the Monti government (2011–2013); the Conte II government (2020–2021) was followed by the Draghi government (2021–2022).

The paper thus considers three distinct contrasts: firstly, between two crises; secondly, between political government and technical government; and thirdly, between two policy domains. The aim is to investigate whether there is a difference in the interactions between subnational governments and technical or political governments during crises, with a focus on the engagement of regions in national decision-making processes. After a discussion on the role of technicians and technocracies in decision-making, with an emphasis on their involvement in emergency contexts (next paragraph), the research question is formulated and followed by a description of the analysed periods. The subsequent sections present the data and methods that were used in the analysis and some conclusions.

Experts, technicians and technocracies

There is agreement that in contemporary democracies the action of technocracies and experts in the decision-making process is relatively extensive and that this intervention challenges representative democracy (Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020). Recently, some research aimed at the Italian case (Capano, Reference Capano2020; Galanti and Saracino, Reference Galanti and Saracino2021; Ieraci, Reference Ieraci and Tebaldi2022, Reference Ieraci2023) pointed out how in crisis management, government action loses autonomy and there is a process of delegating the political decision-making to experts and technocrats, who are often invocated to resolve crises by the public opinion, as a manifestation of an ‘anti-politics’ attitude (Mete, Reference Mete2022).

If one conceived a decision-making process as a complex dynamic, which starts from the identification of end-values, passes through the allocation of the appropriate means for those ends, and finally carries out the implementation program for achieving the end-values, at its initial stage one would find a very complex network of actors. This sort of logic is also evoked by policy network approaches (Rhodes and Marsh, Reference Rhodes and Marsh1992; Smith, Reference Smith1992; Giuliani, Reference Giuliani, Capano and Giuliani1996), although other approaches have stressed the cognitive character of the process, in which a network of public and private actors contribute to generate and maintain the cultural framework within which the ends-values are identified (Haas, Reference Haas1992, 2; Zito, Reference Zito2001; Dunlop, Reference Dunlop, Howlett, Fritzen, Wu and Araral2013; Weiss, Reference Weiss1980; Sabatier, Reference Sabatier1988, Reference Sabatier, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith1993, Reference Sabatier1999).

If the goals-values identification may result as the outcome of complex interactions among actors embedded in a policy-network, a crucial phase of the decision-making process is the selection of the appropriate means for those goals-values by technocracies or technicians, which occupy a key position in policy advisory system in contemporary decision-making (Galanti, Reference Galanti2017, 251 and 259; Caselli, Reference Caselli2020). Indeed, technocracies and experts ultimately hold the technical knowledge which can be used to support the choices over values.

There are unquestionably ambiguities in the use of categories such as ‘technocracy’ and ‘experts.’ This difficulty was rightly emphasised by Lanzalaco (Reference Lanzalaco2022, 289), according to whom technocracy has also been identified with ‘the use of experts and technicians in policy formulation (expertise politics), [and] as a method of decision-making (technocratic decision making).’ We can accept the observation that technocracies, thus understood as highly professional and autonomous administrative apparatuses, differ from expertise in the broad sense because the former have an extensive and almost direct coercive capacity. Technocracies normally control fairly extensive administrative apparatuses, to which policy implementation and social control capacities are attributed. It is no coincidence that decades ago Lowi defined administration as rationality applied to social control (Lowi, Reference Lowi1969, 27).

However, both technocracies in the narrow sense (administrative bodies endowed with a direct capacity for coercion) and in a broader sense (experts and technicians supporting political decision-makers) in practice intervene in politics through the use of resources such as knowledge, know-how, technical expertise, and protocols of action recognised by scientific and epistemic communities. The foundation of their authority to make decisions, or at the very least to determine their content, is found precisely in this ‘superior rationality’ and in the process of ‘depoliticisation’ by which technocracies remove ‘politics’ from ‘policy’ (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020). If the capacity for action of technocracies and experts remains relatively autonomous in the decision-making process, the formal distinction between technocracies and the system of expertise may ultimately be of little importance. Technocrats and experts authoritatively control the resource ‘know-how’ or the ‘intelligence needs’ of politics (Lasswell, Reference Lasswell, Lasswell and Lerner1951), which in all contexts remains relatively independent of the resources of power (coercion, administrative capacity, executive control and the like), as it has been underlined through the decades by many scholars (Snow, Reference Snow1961; Meynaud, Reference Meynaud1969; Gunnell, Reference Gunnell1982; Radaelli, Reference Radaelli1999; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020; Tortola and Tarlea, Reference Tortola and Tarlea2021).

Whilst studies over the relevance of technocracies within the decision-making process are copious,Footnote 1 not much attention has been directed towards the leading capacity of technocrats and technocracies at the central government level, although their role has been growing in the last decades. For instance, Alexiadou and Guanaydin (Reference Alexiadou and Guanaydin2019) argued that technocrats are preferred over experienced politicians when the latter lack commitment to policy reform, and therefore it is questionable whether technocratic governments really challenge the democratic process although they certainly loosen the accountability ties between voters, parties and cabinets (Pastorella, Reference Pastorella2015). Economic crises favour the appointment of technocratic cabinets because of this loosened tie, which possibly make them capable of drastically dealing with policy reform, as shown for instance by the Belgium case (Brans et al., Reference Brans, Pattyn and Bouckaert2016). Recently, the role of technocrats in the Italian ‘State machinery’ since the early 1980s to the present has been scrutinized to disclose how top-government positions have been assigned to them, and also how the intra-state institutional relations have been reshaped and the executive powers strengthened (Cozzolino and Giannone, Reference Cozzolino and Giannone2021).

Governments and decisions in two crises in Italy

The economic crisis and the pandemic affected multiple countries simultaneously and required extraordinary measures to be addressed. In both instances, Italy emerged as one of the countries most affected in Europe. The key distinction between the two crises resides in the different policy arena they activated: the former was an economic-financial arena, while the latter was predominantly a healthcare one – at least for the first part of the pandemic. This distinction is fundamental to understand the role of regions in policymaking, particularly in Italy where the regions have differing levels of authority over the two policy domains, low or absent with respect to economic policy decisions, high and relevant with respect to the organisation of the healthcare system and the provision of healthcare services within their territories.

During both crises, a change of government occurred in the middle of the emergency and, as a result, a political government was followed by a technical one.Footnote 2 When the global economic crisis of 2008 hit Italy, a partisan government led by Silvio Berlusconi was in office. The internal tensions within the ruling centre right coalition (Hine and Vampa, Reference Hine and Vampa2010) and the external pressures of international and European institutions on the country's economic and financial conditions (Jones, Reference Jones, Bosco and McDonnel2012) opened a ‘double crisis’ (Wratil and Pastorella, Reference Wratil and Pastorella2018) that led to the resignation of Berlusconi and the replacement of his government with the technical government led by Mario Monti in 2011, which was favoured by an expansion of powers of the then President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano (Fusaro, Reference Fusaro, Bosco and McDonnell2012; Tebaldi, Reference Tebaldi2023). Monti's technical government was created with the intention of re-establishing the country's credibility in the eyes of the European and international institutions (Wratil and Pastorella, Reference Wratil and Pastorella2018). During the pandemic, the fall and replacement of the Conte II government with the technical government led by Mario Draghi followed a similar path. The external pressures were associated with the necessity of successfully engaging with the European institutions to define the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP),Footnote 3 a unique opportunity to finance the socio-economic recovery of the country linked (but not only) to the health crisis (Garzia and Karremans, Reference Garzia and Karremans2021). The conflict within the ruling majority, particularly the lack of support of Matteo Renzi's Italia Viva, ultimately resulted in the government's collapse. Once again, the President of the Republic, at the time Sergio Mattarella, played a significant role in the decision to appoint a technical government under the leadership of a technocrat thereby avoiding national elections (Tebaldi, Reference Tebaldi2023).

The Berlusconi IV government was formed following the 2008 national elections and it was a purely partisan cabinet. The Prime Minister and the Ministers were all members of the centre right institutionalised parties, namely Popolo delle Libertà, Lega Nord and other minor ones. In contrast, the Conte II government was a partisan cabinet formed in the wake of an internal political crisis within the previous ruling coalitionFootnote 4 and composed by the valence populist Movimento 5 Stelle in coalition with the centre-left party Partito Democratico and the minor centre-left forces. The composition of the government was therefore mixed, including both institutionalised and de-institutionalised parties, as well as non-hierarchical partisans and a Prime Minister with a ‘hybrid profile’ (Camerlo and Castaldo, Reference Camerlo and Castaldo2024).Footnote 5 In addition, the Conte II government was considered weak due to the inexperience of the Movimento 5 Stelle members and the presence of many low-ranking profiles in the government (Capano, Reference Capano2020).

In examining the two technical governments led by Monti and Draghi, it is important to acknowledge that they were not merely ‘caretaker technocratic governments’ (McDonnell and Valbruzzi, Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014); rather, they were fully legitimized ‘with a mandate to change the status quo’ (Garzia and Karremans, Reference Garzia and Karremans2021, 108). The establishment of the technical governments entailed an expansion of the government coalitions towards the centre of the political spectrum. The two leaders were technocrats ‘lent’ to politics, who enjoyed cross-party support, thereby marking a relative suspension of party conflict in Parliament and in the public eye. The Monti government received support from a very heterogeneous coalition composed by all parties except for Lega Nord and Italia dei Valori. Draghi was supported by all parties in Parliament with the exception of Fratelli d'Italia. However, Italian parties tried to show no commitment with Monti's unpopular austerity policies, even if tacitly agreeing on them; instead, they supported Draghi's presidency with the aim of profiting from its distributive – thus popular – policies (Garzia and Karremans, Reference Garzia and Karremans2021; Marangoni and Kreppel, Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022). The Monti government was ‘fully technocratic,’ with no minister holding party affiliation (McDonnell and Valbruzzi, Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014),Footnote 6 while the Draghi government was a ‘technocratic-led partisan’ one (McDonnell and Valbruzzi, Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014), including eight experts assigned to key ministries (Garzia and Karremans, Reference Garzia and Karremans2021).

Much more remains to be said about how these governments behaved with regards to IGRs. Decision-making processes are typically recentralised in times of great emergency and high uncertainty, even if the characteristics of the centralisation and their impact on IGRs ultimately vary from country to country (‘t Hart et al., Reference ‘t Hart, Rosenthal and Kouzmin1993; Peters, Reference Peters2011; Boin et al., Reference Boin, t'Hart, Stern and Sundelius2016; Steytler, Reference Steytler2021). For instance, during the pandemic a strengthening of coordination and cooperation between levels of government was observed in some countries, while in others, a marginalisation of subnational and local governments in decision-making processes came to light (Schnabel and Hegele, Reference Schnabel and Hegele2021; Steytler, Reference Steytler2021; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Kuhlmann, Laffin and Wayenberg2022). Centralisation of policymaking occurred in Italy during the economic-financial crisis in 2008–2013 (Bolgherini, Reference Bolgherini2014; Raudla et al., Reference Raudla, Douglas, Randma-Liiv and Savi2015) and the pandemic in 2020–2022 (Baldi and Profeti, Reference Baldi and Profeti2020: Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021; Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini and Lippi2022). This centralisation was particularly evident in the context of highly technical decisions (Marangoni and Kreppel, Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022). The technical-scientific content of decisions and the involvement of expert committees can marginalize the representative political institutions (government and parliament at the centre, and regions at the periphery) to establish the expertise itself as the exclusive principle of legitimisation of decision-making (Collins and Evans, Reference Collins and Evans2002; Pellizzoni, Reference Pellizzoni and Pellizzoni2011, 16–17). Among the challenges that technocracies present to representative democracy, there is not only the depoliticization of decision-making, but also their anti-pluralist nature (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020). Technocracies are an example of ‘unmediated politics’ in which the exercise of power does not need intermediate structures, as parties or representative institutions, either mobilization of consent to legitimise its decisions in their envisioned unitary society (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). Considering the centralisation occurring during crises and the tendency for technicians to depoliticise and diminish pluralism in decision-making, our research question examines whether in Italy the shift from political to technical governments during the economic crises and the pandemic further marginalized the regions in the decision-making process – that is to say whether this shift led to further centralization of the policymaking. To this aim, the level and forms of participation of regions in national decision-making processes during the economic crisis and the pandemic were investigated. The comparison of the two crises allows for the evaluation of the influence that the policy domain and the characteristics of different emergencies might have had on IGRs. The findings were thus derived from the two emergency contexts (economic crisis and pandemic), the two different types of government (political and technical), and the two different policy areas (economic policy and health policy).

Data and method

The analysis focuses on the IGRs between the central government and the regions during the economic-financial crisis of 2008 and the pandemic crisis of 2020. The aim is to investigate whether technical governments are more likely to further marginalise regions in decision-making than political governments. The beginning and end of the two periods of analysis correspond with key events: in the case of the economic crisis, the bankruptcy of the U.S. bank Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 and the general elections on 25 February 2013; in the case of the pandemic crisis, the beginning of the state of emergency in Italy on 20 January 2020 and its end on 31 March 2022.

We selected three different decision-making loci where the subnational governments’ representatives have access: (1) the so-called ‘conference system’; (2) the national legislative activity at the central level; and (3) public organizations or agencies created ad hoc by the central government to deal with the crisis. The conference system includes three intergovernmental councils.Footnote 7 The Unified Conference (Conferenza Unificata – CU) and the State-Region Conference (Conferenza Stato-Regioni – CSR) are both provided for by national law and are committed to vertical cooperation. The Conference of the Autonomous Regions and Provinces (Conferenza delle Regioni e delle Province Autonome – CR) is a private organisation devoted to horizontal cooperation between regions. Data were collected on the activities of the three conferences during the two periods of analysis 2008–2013 and 2020–2022 and distinguished by the government in power with respect to meetings held, agenda points related to the crisis,Footnote 8 and public documents. The analysis focuses on the frequency rate of the sessionsFootnote 9 and the relevance of issues related to the two crises for each conference in each period.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the documents of the CR have been analysed in order to better understand the characteristics of the relationship between central and regional governments: 42 documents issued under the Berlusconi IV government; 27 documents under Monti's government; 61 documents under the Conte II government; 44 documents under Draghi's government. The documents have been classified in six non-exclusive categories based on their contents: opinions, proposals of contents and/or priorities, amendments, requests for meetings, requests for action or funding, reports. All the information and the documents were collected from the official page of the CR, that also includes a section dedicated to the meetings of the CSR and the CU.Footnote 11 Secondly, the analysis moves to the national legislative activities produced by the central government (decrees, decree-laws, legislative decrees, resolutions, ordinances) related to the economic crisis or the pandemic. The dataset is composed of 75 legislative activities for the economic crisis, 483 legislative activities for the pandemic collected on the online databases of Gazzetta Ufficiale Footnote 12 and Normattiva.Footnote 13 The aim is to assess the level and forms of the regions’ participation in national decision-making. Finally, the analysis focuses on the public organizations and agencies created ad hoc by the central government to deal with the crises. Because of the lack of data related to the 2008 economic crisis, this section discusses on the composition and governance of some ad hoc bodies established during the pandemic as an example of the centralisation dynamics.

Dynamics of centralization during the two crises

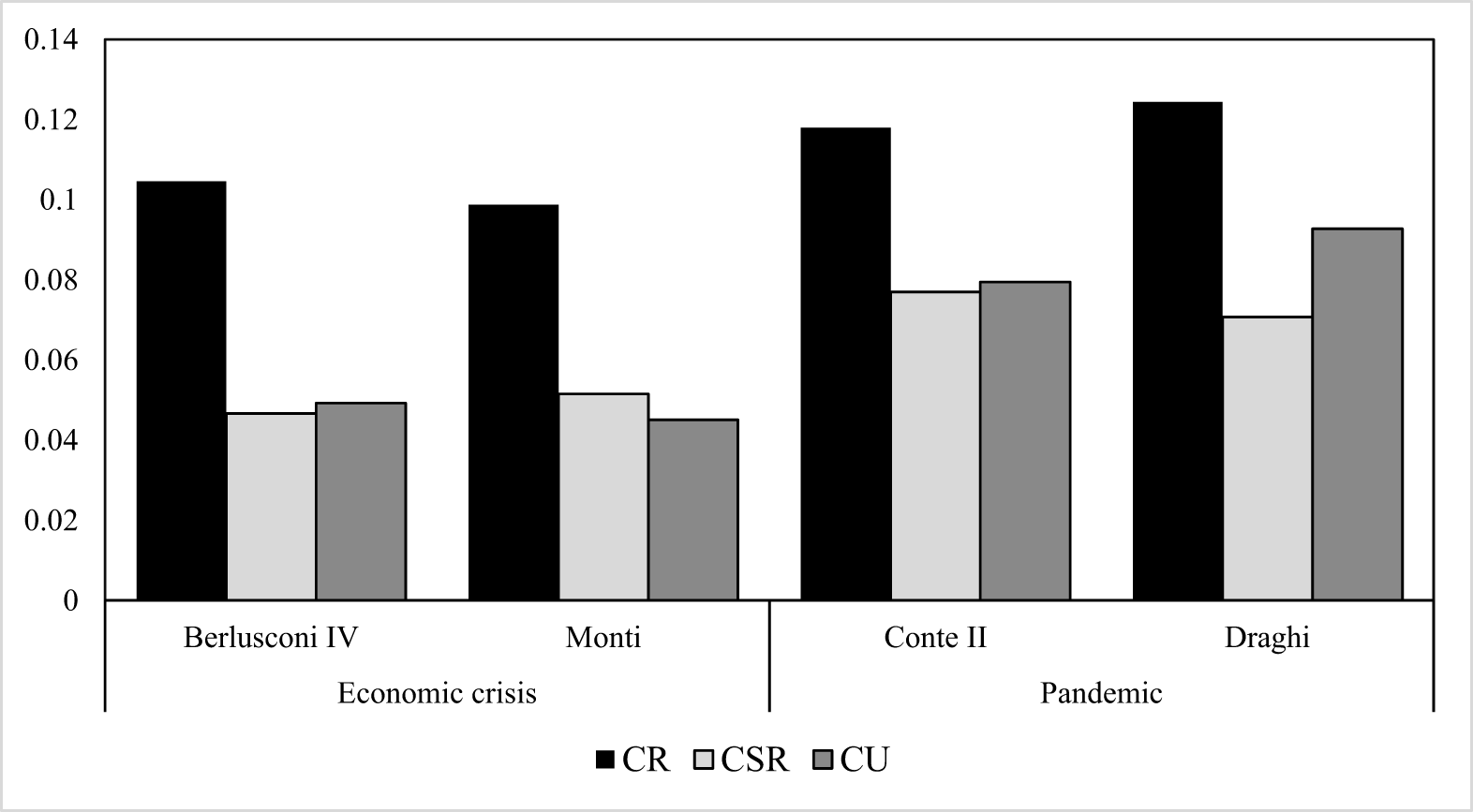

The frequency of meetings of the conferences and the relevance of issues related to the crisis discussed within them show some differences between the two crises. The ratio of the frequency of the meetings is that it is assumed that the more frequent the meetings are the more involved in the crisis management the regions should result. During both crises, the frequency of meetings was quite similar among the political and technical governments (Figure 1). A comparison of the conferences reveals that the CR held a greater number of meetings, regardless of the type of government in power or the nature of the crisis. However, the frequency of all conferences’ meetings was generally lower during the economic crisis than during the pandemic. Given that the three conferences held meetings more frequently in 2020–2022, it is suggested that the regions were consequently more involved during the pandemic than the economic crisis.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Frequency of the meetings of the three conferences by government and type of crisis.

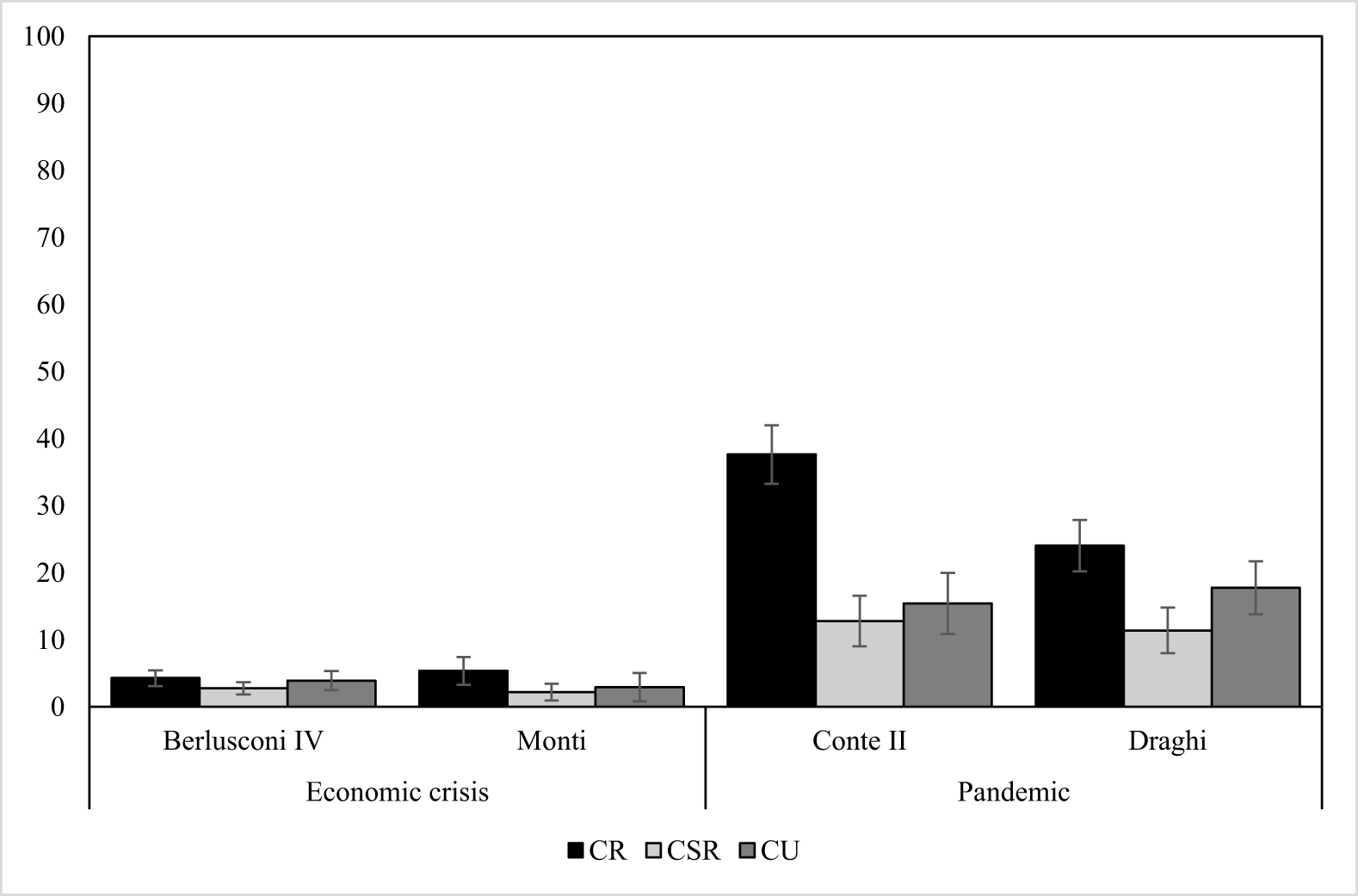

Figure 2 reports the relevance of the issue crisis in each conference by government and type of crisis, as well as its 95% confidence intervals. Little relevance was given by the three conferences to the economic crisis under either the political or the technical governments: the highest percentage of the APs on the crisis is that of the CR (5.3%) under the Monti government. The relevance of the crisis within the conference system was higher during the pandemic than the economic crisis, in the former case consistently exceeding double digits in all conferences. The highest values are observed in the CR's activity under both the Conte II (37.6%) and Draghi (24.0%) presidencies. Moreover, the relevance tends to decrease with the transition from a political to a technical government. This phenomenon was particularly evident in the CR's activity: the relevance of the issue dropped from 37.6% under the Conte II government to 24% under the Draghi government.

Figure 2. Relevance of the crisis in the three conferences by government and type of crisis (%).

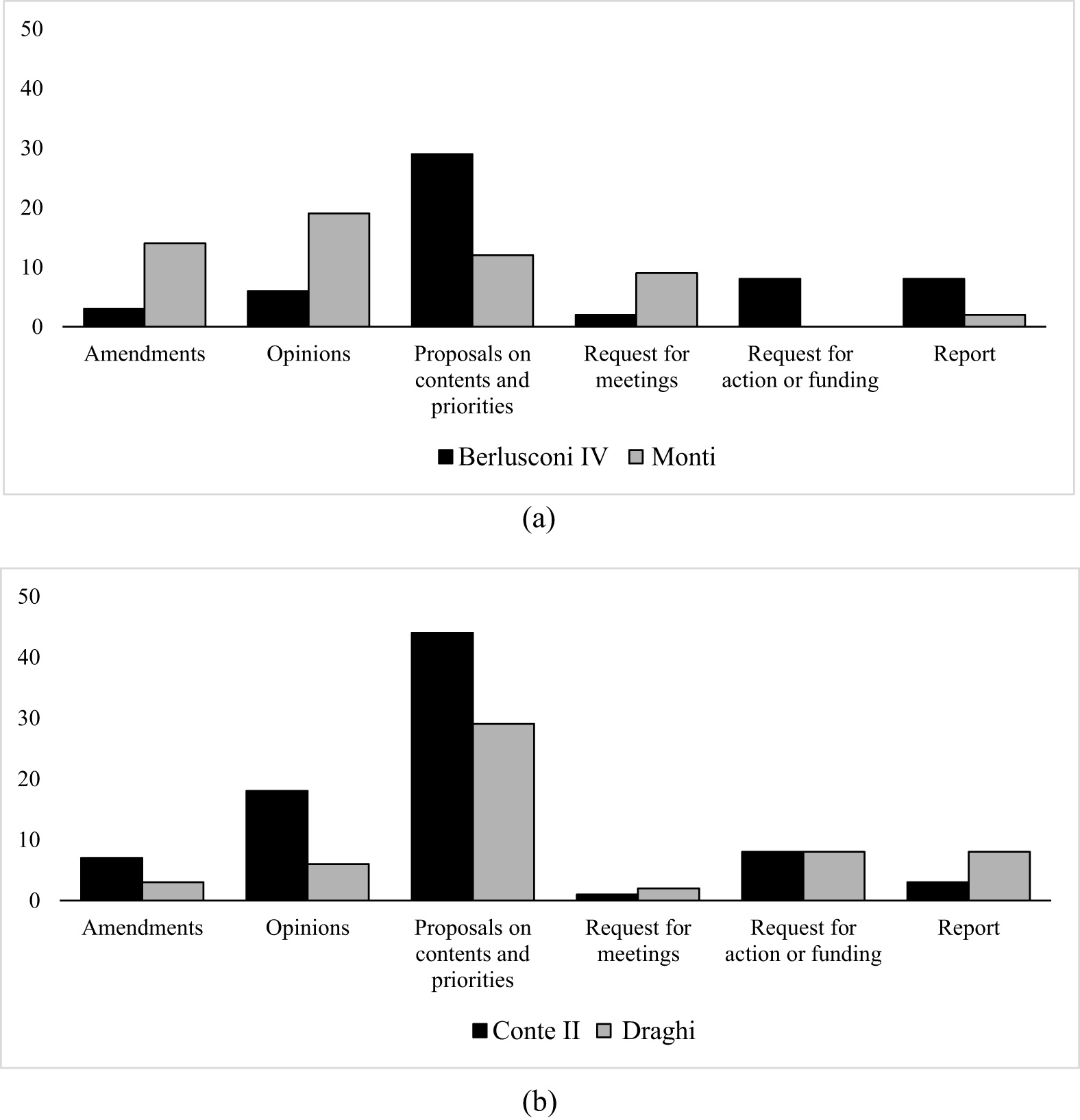

The analysis of the documents produced by the CR brought out some similarities as well as some differences between the two crises by type of government (Figures 3a and 3b). When considered as a unitary period, a comparison between the crises shows that regions in the CR primarily focused on proposing the contents and priorities to the central government (44.9% during the economic crisis; 69.5% during the pandemic) and/or providing opinions on national legislative activity (43.5% during the economic crisis; 22.9% during the pandemic). When a technical government was in power, the CR conveyed more requests for meeting with the national executive than under a political government. During the economic crisis, the requests for meetings mostly focused on financial reforms and retrenchment policies. Indeed, since Monti's technical government was appointed, regions asked for a fruitful confrontation to ‘urgently reform the institutional system and reduce the related costs with proposals drawn up jointly by the various levels of government’ (Document Prot. n. 5032/CR, meeting 17 November 2011).Footnote 15 Regions made a strong case for a direct confrontation with the government, and Monti himself was the subject of their criticism due to the potential impact of his policies on citizens’ well-being: ‘(the CR) requests an urgent meeting with the Prime Minister, Prof. Mario Monti (…) Failure to do so can only result in the central state being directly responsible for guaranteeing the provision of essential services’ (Document 12/167/CR01/C2, meeting 29 November 2012).Footnote 16 During the pandemic, the number of requests to meet with the Prime Minister is lower than that observed during the economic crisis. This can be attributed to the fact that the frequency of meetings between the national and subnational governments within the conferences was higher in 2020–2022 than in 2008–2013. The most common request was ‘to initiate a permanent technical-political confrontation, to be implemented through thematic meetings’ regarding the local public transport (Document 22/32/CR7bis-a/C3-C4, meeting 2 March 2022). During the pandemic, the documents were proactive in relation to the policymaking process under the political government, as they were mostly concerned with proposals, opinions, and amendments. By contrast, the documents seem to imply a greater marginalisation of the regions under the technical government, since they mostly provided reports, requests for meetings and for action or funding. However, the same cannot be said with respect to the economic crisis, when there was no clear indication of any difference in the IGRs depending on the type of government (whether political or technical) when comparing the relative documents produced by the CR.

Figure 3. (a) Number of CR documents by category and government during the economic crisis. (b) Number of CR documents by category and government during the pandemic.

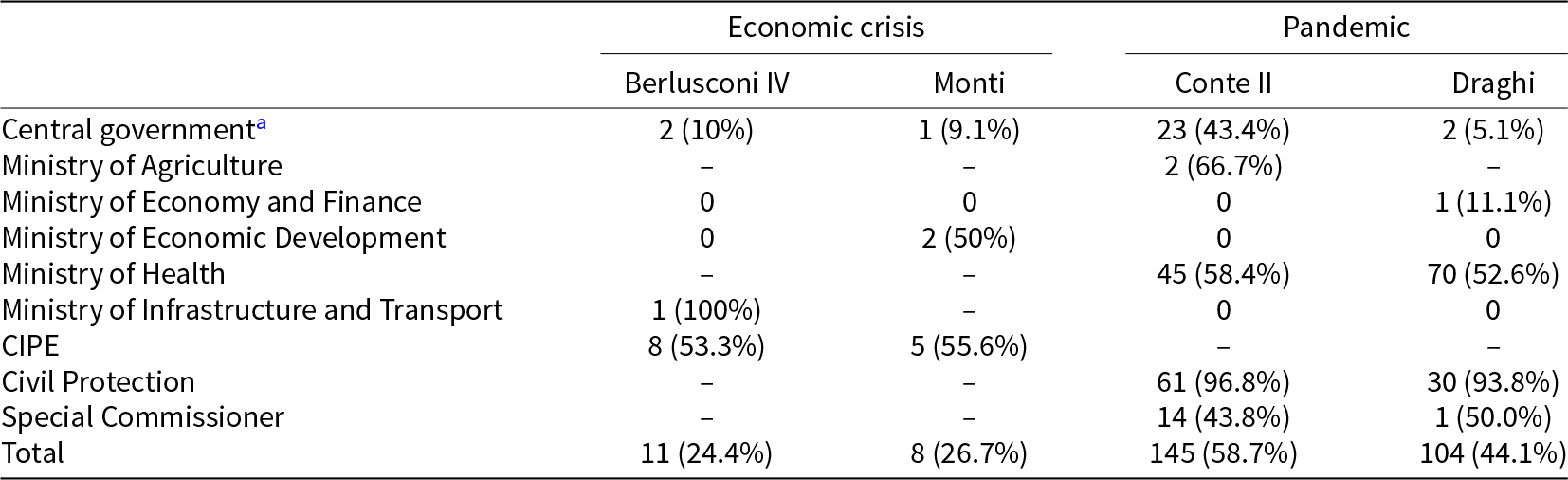

With regards to the period 2008–2013, 75 legislative activities concerning the economic crisis have been collected; of these, 19 (25.3%) reported in their preambles a mention to regions’ participation in their decision-making. The legislative activities mentioning the regional participation (Table 1) refer to the agreements and understandings that were approved in the CSR, as well as meetings held with the Minister of Regional Affairs. The Interministerial Committee for Economic Planning (CIPE) is the institution that most frequently interacted with the regions under both presidencies, while the central government did so to a much lesser extent. Overall, the regions’ involvement rate in the legislative activities addressing the crisis was 24.4% during the Berlusconi IV government and 26.7% during the Monti government. During the pandemic, regional participation in national decision-making was more evident than in the economic crisis. Of the 483 legislative activities on the pandemic collected, half of them (249 in absolute number, 51.6%) mention the regions in the preamble as part of the decision-making process. During both governments, the Civil Protection and the Ministry of Health – the two actors typically responsible for the management of the emergency (Ieraci, Reference Ieraci and Tebaldi2022, Reference Ieraci2023) – were the most inclined to involve regions in the decision-making process. Regions’ participation declined under the Draghi presidency, particularly with regards to the central government's activity. The increase in the number of Ministry of Health's activities mentioning regional participation during the Draghi government is affected by the procedures to adopt restrictive measures during that time, which required the involvement of the regional presidents to assess the risk zone for their respective territories. Overall, the regions’ participation in decision-making in the legislative activities addressing the pandemic was 58.7% under the Conte II presidency and 44.1% under the Draghi one.

Table 1. Crisis-related legislative activities mentioning regions in their preamble by actor, government in office and type of crises

a Central government includes the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministries.

Percentages are calculated on the total number of legislative activities related to the crisis by actor.

Source: Our elaboration.

The way regions were involved in the decision-making differed between the two crises. Regional involvement was more ‘institutionalized’ during the economic crisis than during the pandemic. In 2008–2013, subnational governments were mainly involved through the Minister of Regional Affairs and the CSR. In a limited number of occasions, individual participation was observed; furthermore, no specific role was designated for the CR. In contrast, during the pandemic, the channels of regional involvement were less institutionalised and more flexible. Indeed, the CR assumed a more significant role, with approximately half of the mentions of regional participation referring to it (116 out of 234), particularly during the Conte II government (73.3%).

The last section of analysis focuses on the organisations created ad hoc by the central government to deal with the crisis. In crisis management, Italian executives resorted to experts recruited from within administrations and state agencies, with respect to well-defined policy areas (Ieraci, Reference Ieraci and Tebaldi2022, Reference Ieraci2023). This is ultimately one of the possible modes of intervention of ‘scientific advisory committees,’ as also recently argued by Capano et al. (Reference Capano, Casula, Malandrino, Terlizzi and Toth2023). The lack of involvement of the regions in the composition of these organisations can be understood as a further measure of the centralisation of powers. During the 2008 economic crisis, the central government established several technical task forces. For instance, the ‘Unit for the Protection of Employment,’ which was created by the Minister of Welfare, was composed by ministerial technicians and the presidents of the employment sector's main organisations. Another notable example was the ‘Committee for the Safeguard of Financial Stability,’ which was established on 7 March 2008. The Committee was chaired by the Minister of Economy and Finance and composed of the Bank of Italy, the National Commission for Companies and the Stock Exchange (Commissione nazionale per le società e la borsa – Consob) and the Institute for the Supervision of Private Insurance (Istituto per la vigilanza sulle assicurazioni private – Isvap). It held meetings at least twice a year or as required in periods of systemic financial crisis. Unfortunately, it is not possible to further discuss the composition and governance of these organisations due to the limited availability of data on the 2008 economic crisis. However, several ad hoc organisations were established during the pandemic too. The composition of some organisations did not include subnational governments, as the ‘Ministry of Health Task Force,’ the ‘Committee of economic and social experts,’ the ‘Unit for the completion of the vaccination campaign and other measures to combat the pandemic.’ Nonetheless, regions participated in the ‘Control Room State-Regions-Local Authorities,’ the ‘Technical Control Room for the analysis of data,’ and the ‘Political Task Force Covid-19 Emergency Working Group – Phase 2’. The renowned Scientific and Technical Committee (STC) ensured the involvement of one regional representative, whose profile was distinctly technical rather than political. The governance of the NRRP and the establishment in October 2021 of the Control Room for the NRRP (Decree 77/2021), chaired by Draghi himself, represents a particularly intriguing case study. The Control Room was designed by the central government as the main political steering body for the interventions of the NRRP. In the transition from the Conte II government to the Draghi government, the NRRP governance underwent a notable shift towards a greater centralisation also adopting a hierarchical structure (Guidi and Moschella, Reference Guidi and Moschella2021; Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021). In the absence of any initial provisions for the involvement of regions in the Control Room, the documents of the conferences reveal that subnational governments exerted pressure on the central government to ensure their participation in Control Room meetings (Ripamonti, Reference Ripamonti2023). Consequently, subnational governments have become integral contributors to the composition of the NRRP Control Room, specifically in matters pertaining to regional interests. Moreover, another technocratic initiative introduced by Draghi was the establishment of a Technical Secretariat, which consists exclusively of technicians and experts who are responsible for supporting the activities of the Control Room.

It can be concluded that the findings of the three analyses are somewhat nuanced. An analysis of the variations in the IGRs with different governments during two distinct crises suggests that there was a further centralisation of powers under technical governments, particularly during the pandemic. Conversely, during the economic crisis, the differences between the two types of governments were not significant enough to draw the same conclusions as observed in the health crisis. These findings can be connected to the nature and some of the characteristics of the two crises.

Firstly, the main factor explaining IGRs in times of emergency can still be considered the policy domain of the crisis itself. The results on the conference system activities and the central government legislation showed that regions were overall less involved during the economic crisis than during the pandemic, regardless of the type of government in office. In the whole 2008–2013 period, there was little involvement of the regions in formulating the economic and financial policies. Since regions have no powers with regard to economic policy, it proved even more challenging for them to participate in an emergency situation already characterised by centralisation per se. Conversely, the pandemic was a ‘boundary spanning’ crisis (Carter and May, Reference Carter and May2020) that hit several policy areas under the control of regions. Therefore, although in a context of centralisation of powers, regions could have been more involved in national policymaking because of their responsibility in the healthcare sector.

Secondly, the greater centralisation of decision-making during the economic crisis can also be partly explained by the characteristics of the two emergencies. The 2008 economic crisis, in fact, had an indirect impact on subnational governments. In order to address the economic crisis, a centralised approach was required, firstly with regard to state finances and secondly in terms of the redistribution of internal economic resources. These decisions were made by a small group of key actors, the majority of whom were involved in economic policy: Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, Ministry of Economy and Finance, Ministry of Economic Development, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Education and the CIPE. The impact of these decisions on the lives of citizens was rather indirect. The regions were not asked to directly implement any policy program, but rather to adapt to the reduction of resources imposed by the crisis. On the contrary, during the pandemic the involvement of subnational governments was extremely important to monitor the respect for the new rules and restrictions set by the national government. Above all, the regions came into play directly in the management of the implementation programmes to combat the emergency. The ‘agencies’ responsible for implementing anti-crisis policies (hospitals, vaccination centres, medicines, medical and hospital staff, police forces) were directly controlled by the regional governments (particularly in the case of the national health service which in Italy is regionalised) or allocated and operating within the regional territory. Thus, the regional presidents and the conference system became a ‘counter-power’ capable of altering the balance and affecting the success of anti-pandemic policies to the point that the technical governments were forced to involve them to a partial extent. The health crisis affected various dimensions, from individuals’ health and freedom of movement to the labour market and the production of goods and services. Therefore, very different actors had been called to action during the pandemic: Ministry of Health, Ministry of Agriculture Food and Forestry, Ministry of Tourism, Civil Protection, Special Commissioner for the COVID-19 crisis, Department of Sport, and others. It can be argued that the nature of the two crises resulted in the economic crisis triggering less pluralistic decision-making and power arena than the pandemic did.

Thirdly, the hypothesis concerning the possibility of a further centralisation under technical governments in comparison with political governments is not as evidently supported by the results for the 2008–2013 period, as regions were only marginally involved irrespective of the type of government in office. Instead, a greater centralisation by the hands of the technical government was found in the context of the pandemic. The relevance of the issues within the three conferences as well as the number of legislative activities involving subnational actors for their approval showed lower values if compared to what happened during the Conte II government. For instance, the greater relevance of the ‘crisis’ issue in the conference system under political governments and the increased demands for meetings with the Prime Minister under technical governments were particularly evident in the context of the pandemic crisis. The anti-pluralistic nature of technical governments (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020) manifested itself particularly in the context of the pandemic crisis. It is important to note that while the initial phase of the crisis, during which the Conte II government was in power, was marked by significant uncertainty and unpreparedness, Draghi's technical government assumed power at a time when the vaccination campaign had just been initiated, contagions were declining, and the predominant public concern had shifted to the socio-economic recovery of the country.

Conclusion

This research addressed the broad issue of vertical IGRs in a decentralised system and in times of crises, taking into consideration the alternation between a partisan and technocratic government during the economic crisis and the recent pandemic. The literature has addressed the topic from different point of views highlighting the centralising effect that crises (Lipscy, Reference Lipscy2020; Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Kuhlmann, Laffin and Wayenberg2022; Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini and Lippi2022) and technocracies (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020; Ieraci, Reference Ieraci and Tebaldi2022, Reference Ieraci2023; Marangoni and Kreppel, Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022) may have. These two aspects were combined in our research design by asking whether in emergency situations, where subnational levels of government are usually marginalised, the shift from a political to a technical government leads to even greater centralisation. In relation to Italy, it was already argued that there was a centralisation of decision-making processes during the two crises (Bolgherini, Reference Bolgherini2014; Raudla et al., Reference Raudla, Douglas, Randma-Liiv and Savi2015; Baldi and Profeti, Reference Baldi and Profeti2020: Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021; Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini and Lippi2022). Nevertheless, a comparison between these two periods, focusing on the transition from a political to a technical government within them, offered a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. For instance, the study found that, in the conference system, the CR played a more significant role than institutionalised conferences during the pandemic. Furthermore, when regional participation in the national decision-making process was observed, it was often the president of the CR who was involved. In contrast, during the economic crisis there were less, but formal interactions between the central government and the regions. The findings suggest that the actors employed a variety of channels in their relationship, with a greater degree of rigidity and formality in the context of the economic crisis, and a greater degree of flexibility and autonomy in the context of the pandemic. However, the main finding of the research is that the policy domain appears to be the primary dimension influencing the IGRs, with the type of government being the secondary factor. The comparison between two different emergencies in Italy, the economic crisis and the pandemic, showed that the specific policy-domain of the crisis was a key intervening explanatory factor for IGRs. Indeed, a process of further centralisation of powers under a technical government was observed during the 2020–2022 pandemic period. It is important to note that Italian regions are responsible for the organisation and provision of healthcare services and the pandemic was first and foremost a health crisis. The influence of the type of government and the policy domain on centralisation was particularly evident in the design of the NRRP's governance by the Draghi government (Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021).

The hypothesis on the further centralisation under technical governments during crises has thus been partially supported. However, it is important to note that the results achieved should not be regarded as a limitation, but rather as a preliminary step towards a more profound understanding of IGRs in Italy. From this perspective, a comparison with different decentralised systems may provide new insights on the issue under discussion, namely the prevalence of the policy domain as an explanatory factor for IGRs during crises. Additionally, further research on the Italian case could address crises of various natures, such as the environmental crisis or the migration crisis, that challenge the relations between state and regions in different ways.

Funding

The research has been funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, through the PRIN 2020 Project DEMOPE [grant number D61-RPRIN22-DEGIO_01].

Data

The replication dataset is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/ipsr-risp.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the guest editors of the special issue “The politics of polycrisis: institutions and political actors in turbulent times”, which this work is part of, and the anonymous reviewers’.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.