Introduction

This special issue originated from the observation that in past decades of research on comparative politics in Europe, Italy has tended to be viewed by both Italians and non-Italian observers as sui generis. Often (although not always), this perspective has adopted an implicitly or explicitly negative view of “Italian circumstances”: Italian governments were shorter-lived than those elsewhere and were very ineffective in steering public policies (Di Palma, Reference Di Palma1977; Cassese, Reference Cassese1980), Italian unemployment was persistently higher than in neighboring economies (Saint-Paul, Reference Saint-Paul2002) and corruption levels in the public sector were extraordinarily high (Heidenheimer, Reference Heidenheimer1996).

These differences often showed up in the way that researchers treated the Italian case from a comparative perspective. On the one hand, those who focused on Italy often explicitly described it as an “anomaly” or “outlier,” or at least treated the appropriateness of the “anomaly” or “outlier” designation as a research question in its own right (e.g. Pujas and Belton, Reference Pujas and Belton1999; Naticchioni, Ricci & Emiliano Rustichelli Reference Naticchioni, Ricci and Rustichelli2008; Bull and Newell, Reference Bull and Newell2009) – for an overview of the use of term “anomaly,” see Sassoon (Reference Sassoon2013). On the other hand, those studying cross-national developments in European parliamentary democracies were unsure of its classification in comparative perspectives, sometimes placing it in studies alongside the more established Western European democracies and early Common Market members but at other times grouping it together with the late-developing democracies of Southern Europe (e.g. Pasquino and Valbruzzi, Reference Pasquino and Valbruzzi2010, in which Italy was still considered an anomaly.)

More recently, or perhaps perennially, some of these and similar pieces of received wisdom about Italian differences have been called into question. This is due in part to changes within Italy; however, it also reflects the ongoing changes in the politics and economics of other European countries, which are also not what they used to be.

Thus, whereas until the 1970s British commentators had regularly identified Italy as a path to be avoided, a growing trend in British debates ensued soon after that noted (usually with horror) that Britain had fallen behind Italy on certain economic, social or political indicators (Costa, Reference Costa2018). In the 1990s, following the collapse of the party systems associated with the Second Italian Republic and the adoption of new electoral laws, Italy’s famously short-lived governing coalitions disappeared, replaced by governments that lasted the full-length of the electoral period – several of them led by businessman-turned-politician Silvio Berlusconi. However, while Berlusconi's governments may have lasted, he himself seemed to be an anomalous figure the first time he trod the stage of Italian politics, leading a provocatively flamboyant lifestyle and being prone to pronouncements that flouted conventional political wisdom – fighting indictments that seemingly would have toppled politicians elsewhere. In hindsight, his political style appears less anomalous and more akin to a direct precursor to (and probable inspiration for) the personalistic politics of future successful outsider businessmen-turned-politicians, most notably Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. In economic terms, Italy also appears to have become more like its neighbors. Whereas prior to the 1990s, Italy’s economy had suffered relatively high inflation rates compared to other EC counties, and by the 1990s, the country had implemented major economic and social reforms that enabled it to achieve the economic convergence with its neighbors that was required for founding members of the Eurozone (Sandholtz, Reference Sandholtz1993; Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2000). Whereas through the 1970s many Italian citizens emigrated to Northern Europe and beyond, by the 1990s Italy had been joined by a flood of migrants from less economically developed countries (Gomellini and O'Grada, Reference Gomellini and O'Grada2011). Such political and economic changes have prompted reassessments of the Italian case, with new tendencies to regard Italy as a “normal” polity (Newell, Reference Newell2010), or – in an even more unexpected turn of events – as a forerunner whose experiences can shed light on subsequent developments elsewhere (Schulz, Reference Schulz, Beretta, Berkofsky and Rugge2014; Musella, Reference Musella2020).

These and other anecdotal observations inspired this special issue, whose articles directly tackle the questions of how much the Italy of today resembles its neighbors and what can be learned by viewing Italian policies, economics and politics as part of the same continuum as that of Italy’s neighbors, rather than as being on some alternative dimension. To the extent that there is more similarity between these countries today than in the past, the articles in this issue seek to determine why and how this convergence has occurred and, therefore, what we can learn from the Italian case. When these differences are deemed to have remained strong, the articles seek to identify the origins of these differences.

We begin this introduction by offering some thoughts about how key terms are used throughout the special issue. While the terms themselves are not novel, what is new here is our effort to distinguish between some of these terms, which are sometimes used interchangeably and without regard to their distinctive implications.

This paper is structured as follows. In the following section, a four-sided conceptual distinction is proposed, starting from the dichotomy between “outlier” and “anomaly” in reference to Italy. The “Italy and its “pervasive” anomalies: a real story?” section problematizes the long-lasting scholarly tradition of defining the Italian case as anomalous. In the “The critical 1992–94 juncture and the fall of the First Republic: the opportunity for a new Italian path?” section, the evolution of Italy in the last three decades is considered from the perspective of the conceptualization developed in Section 2. The “The content of the special issue” section summarizes the content of the special issue.

Evaluating the Italian case: a conceptual problem

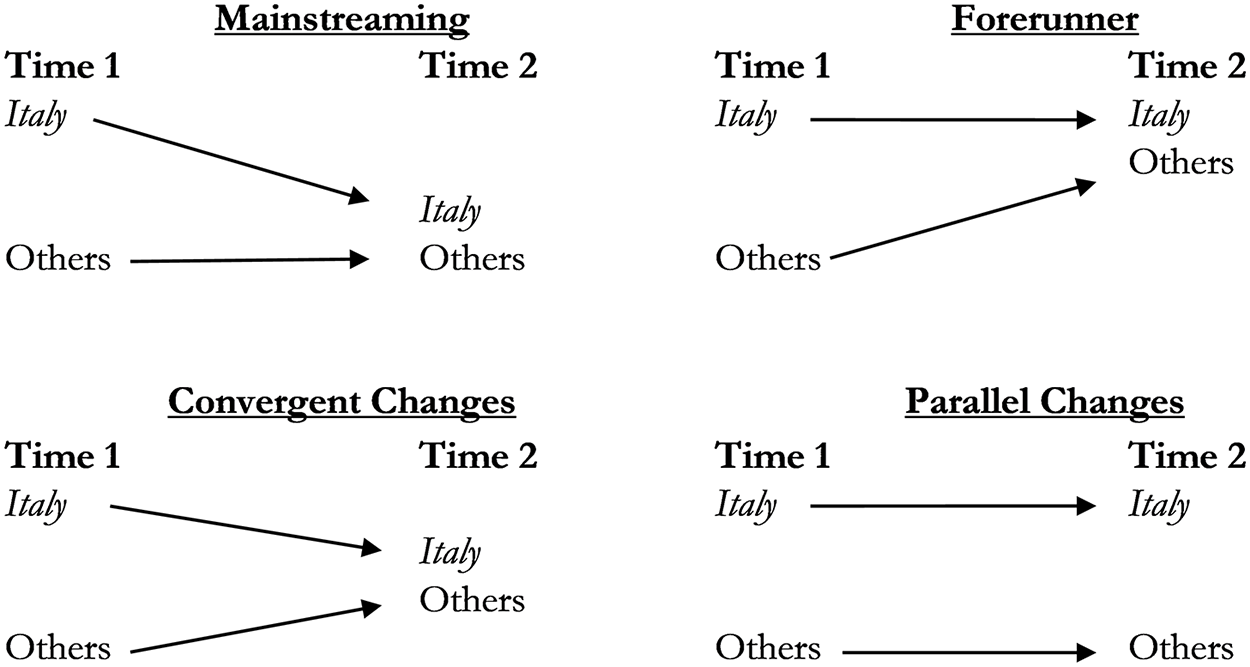

Most of the articles in this issue view Italy comparatively by determining how similar or different Italy is to its neighbors in terms of some specific political or policy aspects. Much of the emphasis in previous comparative studies has been on the “otherness” of Italy; that is, Italy as an anomaly or Italy as an outlier. The articles that follow take these differences as a starting point. They determine whether past differences have continued and, if not, explore why such differences have diminished. Logically, there are three main ways to explain such a convergence: Italy has changed to become more like its neighbors (mainstreaming), other countries have shifted to become more like Italy (Italy as a forerunner), or all countries moved in comparable ways under pressure from similar economic or political pressures (parallel changes).

In this section, we elaborate on the meaning of some of the key terms that will be used in the assessments. We begin by laying out the differences between an anomaly and an outlier. In assessments of Italian politics, economics and society, these labels have been used frequently and often interchangeably and without precision. However, although anomalies and outliers may have similar computational impacts, they have different substantive implications.

Italy as an outlier vs. an anomaly. Social scientists commonly classify cases in terms of their values on key variables of interest and then fit models to try to explain differences and similarities between the cases. In statistical terms, both an outlier and an anomaly are lonely points on the scatterplot that do not fit with a model that otherwise does a good job of predicting the other points in the plot. However, “anomaly” and “outlier” designations offer different explanations for why these lonely points exist.

According to the Concise Oxford Dictionary, “anomaly” is defined as “something that deviates from what is standard, normal, or expected.” In biology, an anomaly is a marked deviation from the normal standard, especially as a result of congenital defects. In economics, an anomaly is an empirical result that is inconsistent with respect to the theory or model. In political science, an anomaly is very often considered something that should not happen according to theoretical expectations or as an irregular/singular phenomenon that should be classified as an exception with respect to the universe of analyzed cases. In this case, the difference seems to be structural, and the expectation is that this diversity will persist over time.

Whereas an anomaly can be considered a persistent difference in kind, an outlier is a difference in degree. In other words, unlike an anomaly, an outlier can be adequately described using the same scales that apply to other cases; however, it displays an unusual and poorly predicted combination of values on these scales. There can be multiple outliers in a single dataset. Because the persistence of differences is a key distinction, determining whether the label “outlier” or “anomaly” is a more appropriate designation should be easier to assess with longitudinal data than with data from a single time point.

An anomaly can be treated as a singularity, one that should be best excluded from comparative analysis because it does not have implications for other cases. In contrast, the presence of an outlier poses a challenge to a model and to the assumptions that generated it. There are two common ways to deal with outliers in quantitative (and other) models. The first is a theory-building strategy that involves conducting a case study of the outlier to identify variables that are missing from the model. Adding these additional variables to the original model then improves the model fit, making the outlier case fit with the rest of the distribution, albeit at the cost of reducing model parsimony. The second common way to treat an outlier case is to control for it by inserting it as a dummy variable in the model. For example, this strategy has been used with the United States in models of electoral turnout (Jackman, Reference Jackman1987). This strategy nominally improves model fit in quantitative analysis and preserves model parsimony, but it sheds no light on why the unusual case differs from the rest. From the viewpoint of comparative politics analysis, the outlier is more useful when it is regarded as a puzzle with a valuable solution rather than an annoyance (Rogowski, Reference Rogowski1995).

As this suggests, viewing cases as an anomaly is not a fruitful analytical perspective for comparative political analysis. It is thus a perspective that should be used extremely sparingly, thus ensuring that the label is not applied merely to avoid the work of revising existing models to account for omitted variables that are driving underlying relationships. Thus, in the case of apparent outliers, it should usually be possible to evaluate existing differences in terms of degrees that can be theoretically and empirically justified and explained. Even in the case of political or policy differences that persist over time, the differences may look less anomalous if analyses focus on why these differences persist in the presence of changes that seemed likely to erase some of the differences.

As we detail in the next section, Italy has long been viewed – or even stereotyped – as one of those lonely points on the scatterplot. The question raised by the contributions in this special issue is whether and how its distinctiveness was due to differences in degree in factors that might change over time. If longitudinal analysis reveals that differences between Italy and its neighbors are diminishing, persisting or increasing in any given area of interest, this would then raise questions about what is driving these dynamics. We posit four logically likely scenarios as to how such changes might unfold.

Italy going mainstream. Under this scenario, convergence has occurred primarily because Italy has adjusted its politics, economics or policies in ways that resemble other countries in the relevant reference group. Italy has changed more than other countries. For instance, this might happen due to Italy needing to conform to European Union (EU) regulations that are written to resemble practices that are more like those in other countries than like previous Italian practices. This path indicates that Italy is converging toward a shared model and thus becoming more like other comparable countries.

Italy as a forerunner. Under this scenario, convergence has occurred primarily because other countries have moved in Italy’s direction. What had once seemed unusual about certain aspects of Italian politics or economics now seems to have been prophetic. For some reason(s) – either those that had originally driven the Italian circumstances or those that had not – political or economic circumstances in other countries are now looking more like those previously experienced in Italy. Italy has changed less than other countries.

Italy and other countries undergo convergent changes. Under this scenario, there is a common process of change both in Italy and in the other countries, which results in a kind of symmetrical effort towards the reduction of actual differences. This could happen when large-scale external disruptions force similar changes upon all countries. For instance, a global economic shock or crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, could force all governments to try out similar and convergent solutions. This also could happen more gradually and possibly be engineered by transnational institutions such as the EU, which serve as forums to negotiate and foster policy and political convergence.

Italy undergoing parallel changes. Under this scenario, change has occurred due to major political or policy transformations in both Italy and its neighbors; however, the results show that the previous differences have been maintained, and thus that Italy remains an outlier on a specific political dimension or in a specific policy field. These four scenarios are visually depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Italy in comparative perspective: four possible dynamics of convergence/divergence.

Italy and its “pervasive” anomalies: a real story?

Viewing Italy as an anomalous country is something that belongs to the country’s national intellectual and political history and is a diagnosis that has not been restricted to the political dimension alone. As is well known, the Italian political system that developed after the end of World War II until its fall in the 1992–94 period has been characterized by certain political features that many observers and scholars have defined as anomalies, such as the lack of alternation in government, the presence of the stronger Communist party in the Western world, symmetric bicameralism and the centrality of Parliament in policymaking (Galli, Reference Galli1975; Farneti, Reference Farneti1983; Crainz, Reference Crainz2009; Castronovo, Reference Castronovo2018). However, l'anomalia italiana (the Italian anomaly), summarized as a fundamental diversity of the country in some of Italy’s socio-economic-political-cultural dimensions, has been a recurrent theme addressed by scholars and intellectuals since the Unification in 1861.

Since the unification of the country, many observers have underlined the anomaly of the lack of a clear national identity nurtured by a weak state (Tessitore, Reference Tessitore2013). This combination has favored the consolidation of what was, according to a long-lasting and consolidated perspective, considered the anomalous divide between the North and the South of the country (Gramsci, Reference Gramsci1966; De Rosa, Reference De Rosa2004), which has been based on a cultural differentiation between the two parts of the country (Banfield, Reference Banfield1958) and in the diverse level of civicness (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1993). This original anomaly has persisted over time and has been the main driver of other persisting differences in a comparative perspective, ones that very often have been described as anomalies. For example, the weakness of Italian institutions has always been considered an anomaly: the Italian State has been considered so incapable of doing its job that it has been described as “nowhere to be found” (Cassese, Reference Cassese1998), while the weakness of government in policymaking during the First Republic was so evident that it raised the question “Does government exist in Italy?” (Cassesse Reference Cassese1980). Furthermore, the Italian pension system has been defined as anomalous not only because of the existence for many years of the so-called “baby pensions” but also because of the significant fiscal spending used to cover the pension system (D'Apice and Fadda, Reference D'Apice and Fadda2003) and the low presence of active labor policies (Ranci, Reference Ranci2004; Ferrera et al., Reference Ferrera, Jessoula and Fargion2013). Additionally, Italian public debt has been considered anomalous since the end of the 1980s (Pasinetti, Reference Pasinetti1998).

Overall, there is the impression that every dimension that is not seen as normal is considered an anomaly. Thus, the following picture emerges from the literature: the country has considered itself, for many decades, very different from its neighbors in terms of its (in)capacity to have normal politics, a normal public debt, a normal state, normal welfare – with “normal” meaning ‘roughly similar to other countries which have been operating with democratic politics and market-based economies since at least 1945’. This common perception has been certified by the aspirations of some well-known Italian politicians who have written books on their disappointment with the evolution of the country. The most relevant case is represented by former president of the Republic, former prime minister, former Minister of the Treasury and former President of the Italian National Bank, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, who has written a book titled “It is not the country I have dreamt” (Ciampi, Reference Ciampi2010).

This constant tendency to label as an “anomaly” everything that is not like others could represent a common cultural trait that suggests a sense of national inferiority. Whatever the reason, the fact that different types of phenomena and effects are defined as anomalies that indicate the structural diversity of the country is interesting. Nevertheless, if we include in the analysis the distinction proposed above between outlier and anomaly, it appears that some of the cited anomalies simply indicate a difference in degree between Italy and other countries. State capacity and public debt are certainly differences in terms of degree, whereas the cultural differences and the North/South divide can be considered more structural than eternal when seen from a diachronic perspective and when time is the major variable considered. Thus, Italy could be deemed an outlier in terms of these dimensions.

This could also be applied to the so-called political anomalies of the First Republic: The lack of alternation, the centrality of Parliament, the presence of the more powerful communist party in the Western democracies and symmetric bicameralism all look more like anomalies structuring a deviant political system if the time perspective is limited. From a broader standpoint, these variations may look more like differences in degree, which then opens the way for comparative theoretical and empirical analysis focused on how much and why Italy has changed along these dimensions.

After the systemic fall that occurred in Italy between 1992 and 1994, some apparent anomalies clearly disappeared, demonstrating that they were not intractable differences – and thus also raising the question of whether prior diagnoses of “anomaly” were analytically inappropriate or even potentially misleading. Indeed, this radical systemic reorientation illustrates that one of the possible drawbacks of using the “anomaly” diagnosis is that it could obscure tensions that may make certain arrangements difficult to sustain. In another interesting twist, developments in some areas of Italian politics since the mid-1990s make it seem likely that Italy could now be considered an interesting case from a comparative perspective more for its being a forerunner than for being a deviant or anomalous case. These topics will be discussed in the section below.

The critical 1992–94 juncture and the fall of the First Republic: the opportunity for a new Italian path?

The turmoil in the Italian political system at the beginning of the 1990s represented a significant watershed moment in the evolution of Italy’s historical dynamics. From the perspective of this special issue, the systemic crisis of the 1992–94 is interesting for its consequences on some characteristics assumed to be anomalies and in terms of new paths that have been opened that break historical legacies. On the other hand, and perhaps not surprisingly, many of the new components of the Italian political systems have been, again, considered “new” anomalies.

For example, the following have been considered anomalous aspects of the Second Republic:

- The lack of agreement on the rules of the game (Bull and Pasquino, Reference Bull and Pasquino2007; Bull and Newell, Reference Bull and Newell2009);

- The never-ending transition and stretching of the constitutional rules pursued by governments against Parliament (Guzzetta, Reference Guzzetta2019);

- The pivotal political role held by a media tycoon (Statham, Reference Statham1996; Mancini, Reference Mancini1997; Pujas and Belton, Reference Pujas and Belton1999); and

- The patrimonialism and populism of Berlusconi leadership (Edwards, Reference Edwards2005).

However, political and economic developments over the past two decades raise questions about the continued utility of characterizing the Italian system solely or even primarily in terms of its supposedly anomalous qualities. In recent years, we have seen that populism, the politicization of the rules of the game, the emergence of tycoons as political leaders and the stretching of constitutional rules have characterized many other democratic systems (from the US to the UK, from Hungary to France, etc.). Thus, it is better to assess the path of the so-called Second Republic in a different, finer-grained way by following the conceptual framework we have proposed above (Italy as forerunner, Italian mainstreaming or Italy undergoing parallel or convergent changes).

These analytical lenses help us better grasp not only the characteristics of change that the Italian political system has undergone after the 1992–94 crisis but how it has expressed novel political processes and dynamics.

According to this point of view, Italy can be considered a forerunner with respect to the following dynamics:

1. The complete renewal of the new party system with high electoral volatility.

2. The first personal party.

3. Berlusconi, who was not only the first tycoon to win in politics but also the first case of a national political leader in a major democracy coming directly from society without any political experience.

4. The first populist party to rule a Western democratic country (the Five Star Movement – M5S).

5. The first post-fascist party to rule a Western democratic country.

6. New forms of party–supporter linkage, including the emergence of a digital “platform party” (M5S) and the first widespread adoption of party “primaries” in a parliamentary system.

7. The first Western European country to reform pension policy structurally.

8. The first European country to reframe migration policy in securitarian terms in the mid-2010s.

This list shows that the recent Italian case deserves more attention from a comparative perspective because it has experienced events, dynamics and phenomena that, while very often considered peculiar to the Italian case (and thus potentially like anomalies) in the first appearance, have become – in the medium term – more common and shared among democratic countries. For example, the Berlusconi case cannot be considered an Italian anomaly after Donald Trump in the United States, or Andrej Babiš in the Czech Republic (another case involving the founder of a personalistic party). The emergence of a new party system and electoral volatility, while based on a shocking fall of the previous system, is simply a more evident manifestation of the complex process of the deinstitutionalization of European party systems (Chiaramonte and Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2022). The huge electoral success of a populist party like M5S and post-fascist parties like Brothers of Italy signal something that could happen in various other countries in Europe. Overall, the political effects of the 1992–1994 Italian crisis are significant indications of what can occur in a structured democratic system when it falls into a crisis of legitimization. Italy was simply the first to enter into this process.

The fact that Italy has been a forerunner in reframing migration can be included among the consequences of the process of transition that a political system must undergo after the previous system has been shown to be incapable of persisting over time. Furthermore, this case shows how, in a changing-party system, issue framing is a strategic resource for the political battle and how this can push towards a radicalization of political discourse that fuels populistic dynamics – a dynamic that is not unique to Italy, though it may have come to the fore here earlier than in other countries.

When focusing on Italy’s capacity to come first in structurally redesigning pension policy, the picture appears to be different. This reform, which operated in two main steps in 1995 and 2012 under two “grand coalitions,” is, first, the consequence of the effects of decisions made decades before that introduced a risk of significant losses for future generations. These decisions, if not reversed, would have made the Italian pension system financially unsustainable in a few years. Thus, there were compelling grounds for making radical changes. Despite this, the reforms were possible only due to the presence of technocratic governments supported by big coalitions (the Dini government in 1995 and the Monti government in 2012). This can be considered an indicator of how redistributive policies (especially between generations) become politically intractable when democratic systems are not sufficiently institutionalized or undergo a period of political instability. Thus, Italy has been a forerunner in pension reform exactly because of the crisis of its political system.

Regarding the potential convergent dynamics through which Italy has “mainstreamed” to become like other countries, there are several relevant dimensions that could be mentioned.

First, the anomaly of no meaningful alternation in governments seems to have been completely overcome. The 30 years of the so-called Second Republic are characterized by alternations in government. Moreover, what occurred involved a dynamic of recurrent and constant alternation in government: no outgoing government won its next election. Second, despite this alternation, in terms of longevity Italian governments have been a bit more stable compared to the past, especially between 1994 and 2012. While the initial changes post-1994 might look like mainstreaming, based on more recent developments we might even see this as parallel convergence, because while Italy is seeing increased alternation of governing parties, many of its neighbors have seen less of this, due in part to multiparty coalitions that are designed to keep out “radical” parties of the left or the right – just as used to be the case in the Italian First Republic. Other relevant convergent dynamics of Italy “catching up” may be fuelled by the choice to join the Euro and Schengen zones. Implementing these decisions required Italy to make changes designed to align it with certain practices and economic averages determined by other countries.

The path of convergent changes characterizes many policy fields due to the European process of integration. These dynamics can be well represented, for example, by the process of convergence towards the same organizational architecture in higher education (the so-called “Bologna Process”) that has characterized all the EU members plus various other European and extra-European countries.

Yet, convergence is certainly not the only story when we look at Italy and its neighbors. In some areas, we see non-convergent changes so that relative rankings of the output of interest have remained stable even as absolute levels have changed. In some of these areas, Italy may, in the end, prove to be a persistent outlier rather than an anomaly, with Italy and its neighbors eventually showing some convergence; but if so, this should lead to questions about what else is happening that maintain divergence in this area in a period where other types of policy outcomes are converging. In other words, even where differences persist between Italy and relevant reference groups, the anomaly label should not be applied until other explanations have been explored.

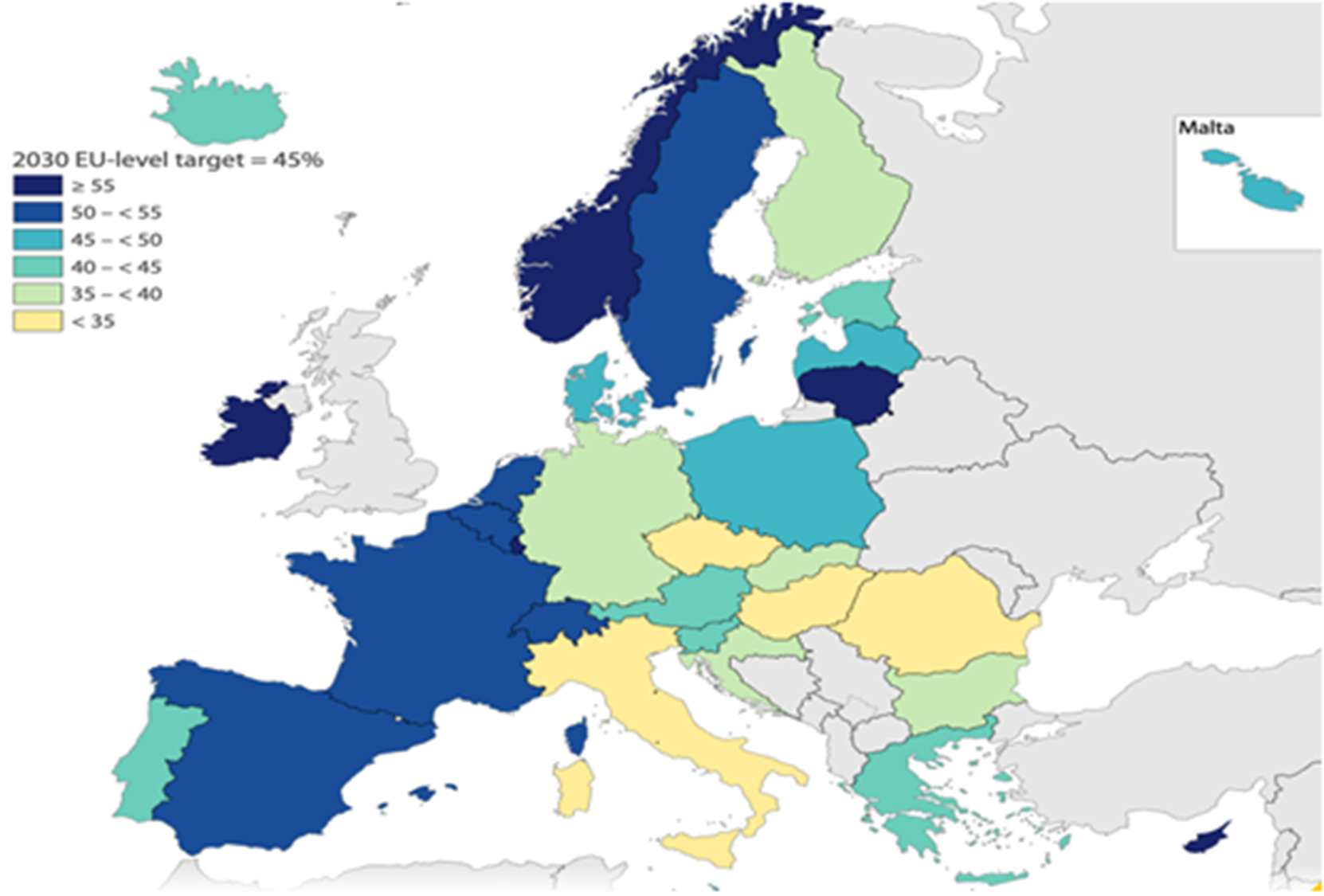

Among the areas in which Italy may still count as an outlier are, for example, educational attainment and public debt. First, Italy is still an outlier regarding the educational level of its citizens. Figure 2 shows the data on the percentage of the population aged 25–34 years holding a tertiary education degree. Italy ranks very low in this respect among the longer-term and higher GDP/capita EU members, although it will improve its score from 24.2% in 2014 (penultimate, just ahead of Romania) to 30.6% in 2023 (third last, just ahead of Hungary and Romania).

Figure 2. Tertiary education attainment in the EU in 2023 (% of population aged 25–34).

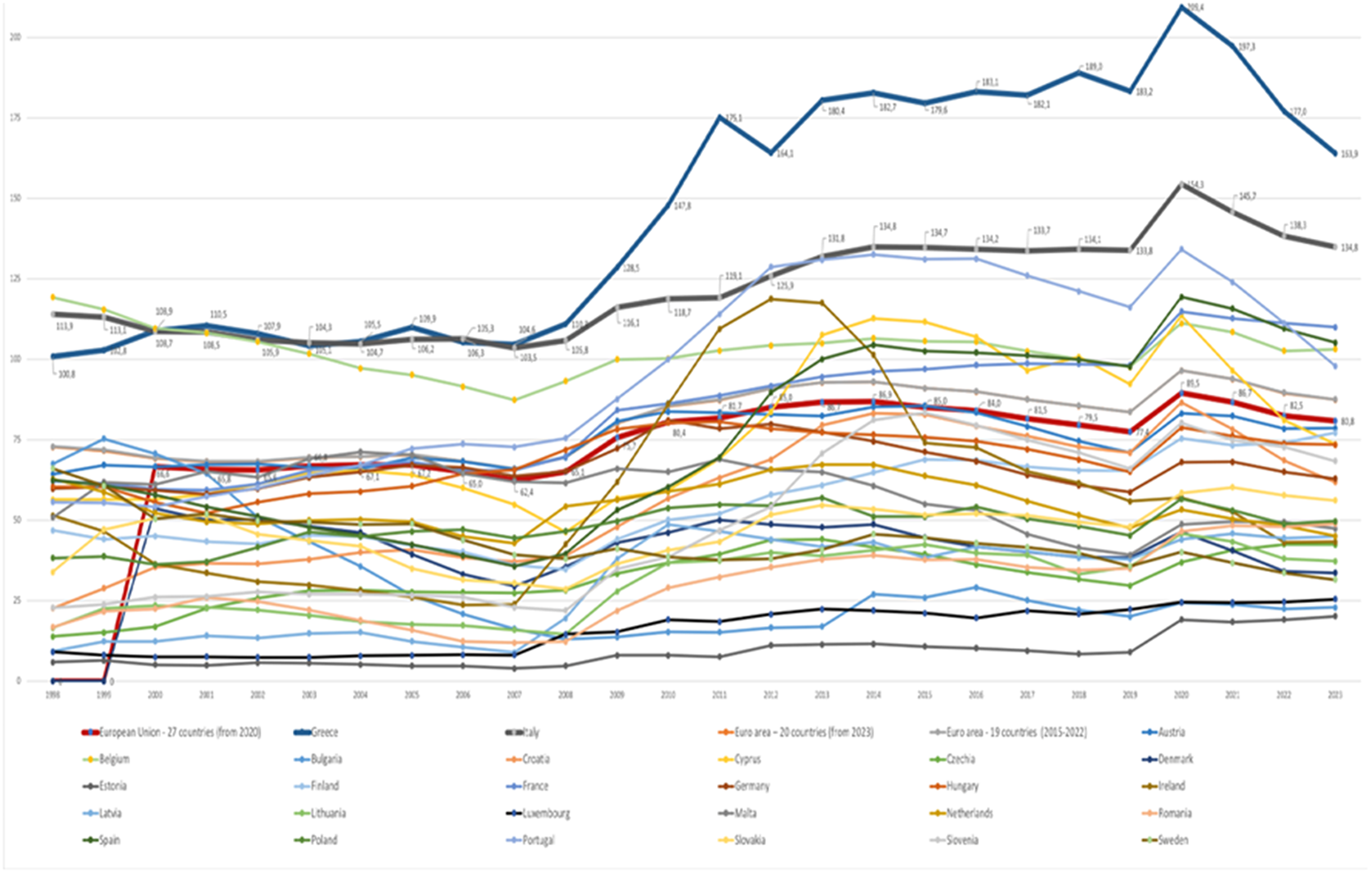

Second, Italy is a clear outlier regarding its public debt. Figure 3 shows the diachronic evolution of Italian public debt (the thick black line) with respect to the other 26 EU countries over the last 25 years. Italy clearly follows the wave without any significant change in its public debt dynamic. In fact, these changes, both public debt increases and decreases, parallel those of other countries. The fact that the difference between Italy and other countries in terms of respect is maintained over time, even in a period where all countries are responding to changes in fiscal markets and fiscal regulation, suggests that this is an area of parallel change (in other words, changes are occurring everywhere but do not lead to convergence).

Figure 3. Public debt 1998–2022 (% of GDP): Italy compared with the other 26 EU countries.

Obviously, the Italian case should be contextualized in comparative perspective because it is not alone in terms of high public debt among the other EU countries considered here. Greek debt, for example, looks higher than the Italian one, thus showing how the condition of outlier is not necessarily a condition of loneliness.

The foregoing examples make clear that when taking a diachronic perspective it is possible to analyze the Italian case in a comparative way using the four types of dynamics outlined above, all without introducing the potentially misleading label of “anomaly.” The proposed evolutionary perspectives can, therefore, help researchers to see Italy as a normal case worthy of inclusion in systematic comparative research because it can shed light on common political and policy dynamics that occur and could occur in similar democracies. Moreover, what might seem to constitute an unpredicted value – an outlier – at one timepoint may better fit into our models when we focus on the forces that lead to convergence or divergence over time. Of course, what is true for Italy is also probably true for most other countries which are singled out as unusual cases: in all instances, it is more likely that we are dealing with outliers rather than anomalies, ones that are not exceptional cases but simply different in degree from the other cases. Good models attempt to account for these differences, rather than merely writing the cases out of the model.

In sum, the Italian case seems to be more multifaceted and perhaps more relevant to others than may have been conveyed by some past analyses and interpretations. The Italian “anomaly” seems to be (or to have become) a variegated arena marked by idiosyncratic dynamics and characteristics, but also by experiences that could illuminate the diachronic evolution of democratic systems.

The content of the special issue

This special issue is designed to deepen the empirical knowledge and comparative analysis of Italian politics and policy in view of the dimensions presented above. Each of the articles in this issue focuses on a distinct area or policy problem in which Italy has at one time been thought to be unusual compared to its neighbors and then assesses whether Italy today still looks so unusual. To the extent that it does not, they consider what explains the shifting diagnosis.

The choice of reference group is a fundamentally important decision when making categorizations of the kind outlined above. For instance, on some dimensions, Italy could look very similar to the other cases in comparison to southern European countries, but it (and perhaps other southern European countries) might appear to be an outlier in a comparison that includes only the largest EU economies, or all OECD nations. As always in comparative politics, it is therefore essential that researchers should explain their case selection logic, because the reference group selection may determine the answer to the question of whether Italy is an outlier or something else. Which reference group is appropriate will depend on what aspect of Italian politics or economics is being considered, but outliers are most interesting and useful for theory-building when they are unexpected – when there are good reasons to expect that all cases will be well-described by a single model, but one case proves to be a bad fit. Because the appropriate reference group is determined by the question being asked, the articles in this issue make different comparisons, with each article explaining its choice of comparison cases.

In the opening contribution, Davide Angelucci, Lorenzo De Sio, Jessica Di Cocco, and Till Weber propose a two-dimensional elitism–pluralism framework to analyze the ways through which goals are defined in Italian polity. To illustrate its relevance, they examine the “2022 Italian election,” which followed a sequence of populist, mixed populist-mainstream and technocratic governments. By comparing voter positions (from the Italian National Election Study) with party positions (from an expert survey), they find that elitism and pluralism influence voting preferences alongside traditional issue-based voting. Furthermore, a preliminary comparative analysis suggests that similar political dynamics could emerge across Europe, thus potentially making Italy a forerunner in this regard as electoral competition increasingly revolves around the very principles of democratic governance.

Next, Paolo Marzi and Andrea Pareschi focus on the development of attitudes towards the EU, looking in particular at the coherence between the preferences of public opinion and elites. Their analysis shows that, compared to other eight EU countries, Italy has been and remains an “outlier” in terms of the pro-European attitudes of its elites and citizens, and also that these attitudes show a relatively mainstream degree of coherence over time. This pattern diverges from that seen in many other countries in which the positions of élites have often looked more radical (positive or negative) than those of the citizens.

Guido Panzano and Sofia Marini then analyze the diachronic evolution of the quality of democracy in Italy and whether and how the characteristics of the political parties have affected this. Focusing on the specific dimensions that make up the index of democratic quality, they show how Italy has been (and continues to be) a forerunner or an outlier, depending on which dimension of democratic quality is considered. They also show how Italy’s low score (negative outlier) on accountability and the rule of law is directly linked to the low level of party institutionalization and to the high level of personalization of politics (two political dimensions in which Italy can certainly be considered a forerunner).

In their contribution, Tiziana Caponio, Andrea Pettrachin, and Irene Ponzo focus on considering policy development in a single area: asylum policy. They show how, at a certain point in the twentieth century, Italy developed a multilevel governance approach to asylum policy that differed from the approaches adopted by other EU countries. However, very soon, under pressure from the EU and internal dynamics, Italy shifted to a more (hierarchical) mainstreaming approach.

Marcello Natili and Matteo Jessoula adopt a theoretical framework that focuses on the interplay between sociopolitical demand (voters and interest groups) and political supply (political parties and governments) in order to analyze the dynamics of social policy. They show how the historically rooted characteristics of this policy field have changed in recent decades. In fact, while Italy could initially be considered a clear case of an outlier in all the main welfare sectors, this condition has changed markedly in recent years. As a result, while Italy remains an outlier in terms of family and social investment policies, it has become mainstream in terms of pensions and employment.

Lorena Ortiz Cabrero and Aline Sierp focus on the use of the politics of memory by the Italian ruling party (Fratelli d'Italia) and compare this to strategies adopted by nationalist parties in Germany and Spain. Through their discursive analysis, they show how this party was able to banalize and normalize the historical experience of fascism, thus neutralizing it. Furthermore, by comparing this experience, in which Italy is definitely a forerunner, with the case of VOX and AfD in Spain and Germany, the paper sheds light on how the main mnemonic tools used for the banalization of fascism can be quickly transferred to other countries.

Taken as a group, these essays make a strong case for the contemporary relevance of the Italian case for studies of comparative politics and policy. After decades of devoted study to understanding the so-called Italian anomaly, it is worth proclaiming and emphasizing the utility of studying Italy again through a comparative lens. Such a perspective can benefit both those who seek to understand Italian developments better and those who are seeking to explain larger cross-national political trends better.

All in all, Italy should be seen as an important laboratory that can foreshadow the evolution of democratic systems facing turbulence and challenges that could undermine their constitutive pillars, rather than as an anomaly that does not deserve to be considered in a comparative perspective because of its peculiarities. Indeed, as the articles in this issue make clear, the Italian case has much to teach us about current and emerging political trends.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.