Introduction

The search for equality is the distinctive feature of the democratic ideal. Sartori had already discussed the complex relationship between liberty and equality in the first formulation of his democratic theory (Sartori, Reference Sartori1962). The Theory of Democracy Revisited (Sartori, Reference Sartori1987a; TDR) significantly expanded the discussion about the second concept. A careful reading of the text, compared to its first edition, reveals several additions and a much more developed reasoning, linked to the thriving discussions which developed in the Anglo-Saxon context throughout the 1960s and 1970s, especially after the publication of Rawls’ Theory of Justice (Reference Rawls1971).

In this essay, I intend to reconstruct Sartori’s “second conception” of equality. I begin by outlining the author’s analytical framework, then connect Sartori’s view with the Anglo-Saxon debates—particularly the contributions of Oppenheim, Rae, Rawls, and Walzer. On this basis, I go on to discuss Sartori’s original contribution to the empirical theory of equality politics. The Conclusion wraps up the main findings.

The framework for analysis

Sartori considers equality as a “protest ideal,” symbolising the struggle to build a better polity. While, as an ideal, equality is easy to understand, the identification of practical inequalities is much more difficult. The first step for any argument about equality must, therefore, consist in elaborating a framework for analysis. Sartori's framework has three components: first, a clear distinction between the different types of equality/inequality; second, the identification of the possible criteria for distributing the fruits of social cooperation; third, a discussion of the grand programmatic options for policy action. The most effective way of summarising the first two components of the framework is to systematise each of them through two typologies.

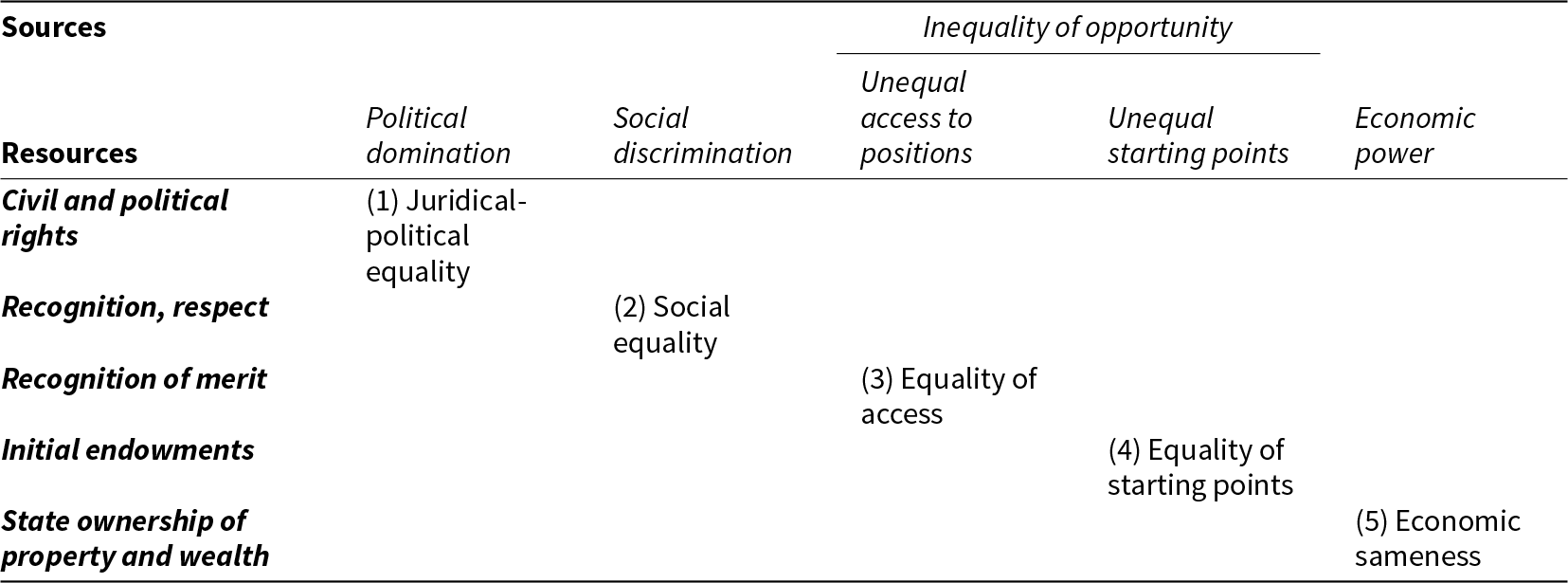

The first isolates five types of equality by combining two dimensions: the sources of inequality and the resources necessary to neutralise them (Table1).

Table 1. Types of equality

Source: Elaboration from TDR, Chapter 12.

Juridical-political equality builds on the rule of law and the mass suffrage, which allow individuals to resist political domination. Social equality is used by Sartori in the limited sense of equality of recognition and respect, which are key for resisting discriminatory practices. Equality of opportunity is a more complex concept. Sartori breaks it down into two different variants: equality of access to social positions, aimed at overcoming non-meritocratic barriers; and equality of starting points, for neutralising the advantages of the natural and social lottery. Finally, there is full equality of material conditions (economic sameness), to fight differentials of economic power.

Sartori's discussion about each type centres essentially on the extent to which it seeks to promote “elevation from below” versus “levelling from the top.” Turning these two goals into polar types of a single dimension, we can say that equalities 1, 2 and 3 are closer to elevation from below, while types 4 and 5 are closer to levelling from the top, as they involve a vertical redistribution of resources.

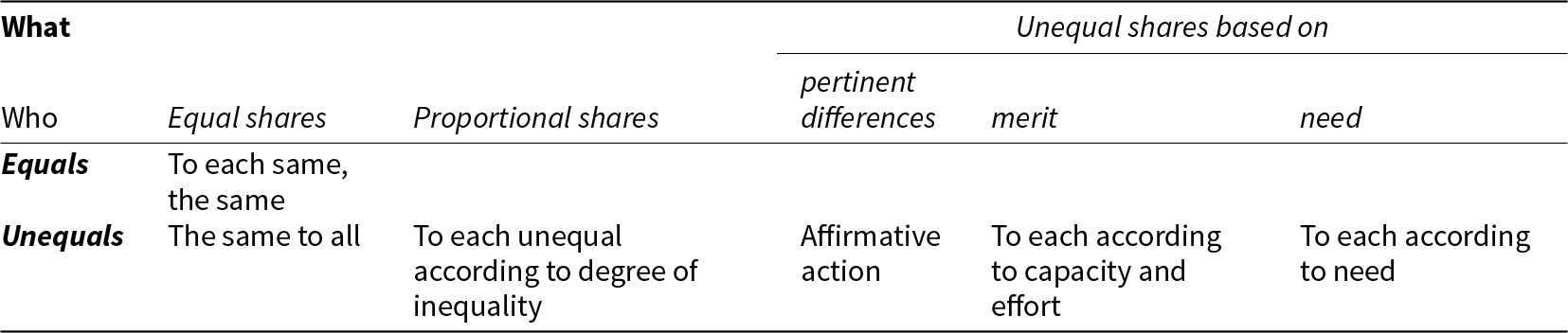

Which criteria must preside over such redistribution in view of equalisation? Table 2 provides a second typology, combining the “who” and the “what” of equalisation. The combination of these two dimensions produces six different criteria. The same to all: this is typically the rationale of the rule of law, which treats all the member of the community alike. Laws must be general; they cannot be “person-regarding.” Thus, inevitably, laws may impose some unjust hardships, insensitive to persons and their differences. The upside is that generality prevents manipulation and gerrymandering. Equal shares to equals is the old Aristotelian criterion, as is its opposite, unequal shares to unequals. In the latter case, the criterion of proportional distribution prescribes to calibrate shares according to the degree of inequality among recipients.

Table 2. Equalisation criteria

Source: Elaboration from TDR, Chapter 12.

But how could sameness be defined, and even more importantly, how can relevant sameness be identified? The remaining three criteria tackle this problem. First, we need to distinguish between sameness at the individual or at the “bloc” level. In the latter case, the targets of equalisation are whole social aggregates. Finally, we find meritocracy and need-based equalisation.

As in the case of Table 1, a meta-dimension lies underneath the six criteria, opposing equal treatment and equal outcomes. The more we shift the focus from treatments to results, the more we approximate a situation in which “all are made equal in all” (TDR, 351). The principle of equal treatment starts from the assumption that individuals are born different; nevertheless, they should be treated equally. The principle of equal outcomes starts from the opposite assumption, i.e. that human beings should not be different “and must be reinstated in their pristine nondifference” (TDR, 351). The logical consequence of this is a “dissonant crescendo”: at the equal treatment pole, we leave the widest space to natural and social differences. Instead, in order to be made equal (the opposite pole), we are to be treated unequally. It follows that, contrary to a widespread position, “equal results require unequal opportunities, and is certainly a fallacy to use results to assess equality of opportunity. Not only equal starts are not equal arrivals, but no opportunity is offered if outcomes are predetermined” (TDR, 351).

Table 2 reveals that, if pushed to the extreme, the six criteria are mutually incompatible. In the real world, compromises can be reached. However, the fact remains that the different criteria – and the different forms of equalities – do not align with one another. There are trade-offs to be considered between the various modes of equalisation.

Here we come to the third component of Sartori's framework. The author suggests that there are essentially three ways for approaching trade-offs. The first one argues that there is an overarching Equality with a capital “E,” which subsumes all the others – e.g. the socialist dream of a world of total equality that suppresses all smaller inequalities. For Sartori that world would be ruled by “a voracious Leviathan,” swallowing up the specific concrete equalities and collapsing them into the specific Equality (e.g. of material resources) that it cherishes.

The second approach is that equality grows by addition, i.e. by summing, one after the other, the different types of equality. Given the inherent incompatibility between criteria, proceeding this way would sooner or later cause the “pile” to collapse. The critical juncture for collapse is probably located at the point where “elevation from below” turns into “levelling from the top.”

The third approach is that of a smart balancing among inequalities. This is the strategy endorsed by Sartori: putting in place “a system of countervailing forces in which each inequality tends to be offset another inequality. Overall, then, equality results from the interplay of a system of liberties-equalities that is designed to cross-pressure and neutralise one disparity with another” (TDR, 356).

Sartori's framework is punctuated with normative propositions. The last section of Chapter 12 provides a retrospective overarching justification of such propositions by establishing a close connection between liberty and equality, and arguing in favour of a lexicographic priority of the first. He concedes that some degree of equality is a facilitating condition of liberty and that we live in a world where individual differences partly stem in part from society and partly from nature. He also acknowledges that equality is a facilitating condition of freedom. However, it is not possible to precisely determine the extent to which differences do result from socially created or natural inequalities which are worthy of being redressed. The “freedom seeker” thus tends to keep aloof from the kind of equality which is inimical to liberty, i.e. the levelling sort.

But why should one be a freedom seeker rather than being an equality seeker? While Sartori provides a number of logical reasons in the last section of TDR (e.g. that equality presupposes freedom, for the simple fact that if there is no freedom, it becomes impossible to even claim equality in the first place), ultimately he acknowledges that the choice hinges on value beliefs. In a Weberian spirit, normative priorities can be argued for by reason but always imply an act of subjective choice.

Influences from (and disagreements with) the Anglo-Saxon debate

While remaining very critical vis-à-vis the Marxist conception of equality as uniformity, Sartori's second conception is more sympathetic towards some form of egalitarianism than he was in the original Democratic Theory of 1962. The literature cited in the footnotes of Chapter 12 reveal an acquired familiarity with the US debates of the time and its liberal-egalitarian turn during the 1970s. Four authors stand out, in particular, as sources of inspiration and/or points of reference.

The first one is Felix Oppenheim. In a series of contributions between the 1960s and 1980s, this author had argued in favour of an analytical approach capable of defining descriptive criteria of equality. In his view, the frequent use of factual statements to express normative views constituted a major obstacle to a productive moral discourse. As is commonly recognised, conceptual clarity was a defining feature of Sartori's approach (Collier and Gerring, Reference Collier and Gerring2008). The analytical framework presented in TDR owes much to Oppenheim's articulated categorisations. This is the case, for example, for the criterion of proportional monotonic equality. Oppenheim had also provided a corrosive logical critique of the statement “all men are equal”: “Human beings can be said to be equal or unequal only in respect of certain characteristics which must be specified. The only characteristic which they all share is a common ‘human nature,’ but that is a tautological statement” (Oppenheim, Reference Oppenheim1970, 143). Sartori brings this argument a step further. Equality seekers typically demand equal rights and opportunities “because” all men are born equal.

But there is no ‘because’ about it. There is no necessary connection between the fact that men are or are not born alike and the ethical principle that they ought to be treated as equals. If equality is a moral principle, then we seek equality because we think it is a just aim. (TDR, 339)

TDR drew other descriptive insights from Douglas W. Rae, author of an important volume on Equalities (Rae et al., Reference Rae1981). Rae's framework focussed in particular on the distinction between person-regarding and bloc-regarding equality – the latter referring to equalising opportunities across different segments or blocs of society, characterised by large distributive asymmetries. The issue of inter-bloc justice emerged in the US during the 1970s, especially in California, in the wake of the civil right movement of the previous decade. For example, in order to remedy for the low rate of admissions within minority applicants, many universities started to introduce reserved quotas, under the assumption that the asymmetry reflected entrenched and unfair forms of discrimination. In Equalities, Rae and his colleagues harshly criticised the quota system.

The practice of affirmative action raised increasing discontent. In the famous “Bakke case,” a white student sued the University of California for racially based “reverse discrimination.” Sartori had moved to Stanford in 1976. He was certainly not insensitive to discrimination according to ascriptive criteria. However, in line with Rae and Oppenheim, he was critical of quotas, raising an empirical objection: however initially well justified, bloc-related criteria of disadvantage tend to generate a subsequent backlash by those blocs which are not initially included by the criteria. Moreover, evaluating outcomes in descriptive terms reproduces on the output side the same mistake of evaluating representation in sociological terms on the input side, i.e. based on the “resemblance” between the represented and the representatives. Sartori admits that descriptive representativeness is a legitimate criterion of evaluation. But the concern about who (which group) must be balanced against the concern about the whats, i.e. the variety of interests and demands to which representatives have a duty to respond (Sartori, Reference Sartori1987b). Reserved quotas maybe acceptable only to the extent that group differences acquire high political relevance de facto and can be objectively traced back to discriminatory rules or practices.

Since the early 1970s, the towering figure of the debate was of course John Rawls (Reference Rawls1971). Even if Sartori never fully spelled out his position vis-à-vis A Theory of Justice. From TDR and other writings, we can, however, infer a number of points of agreement and disagreement. Like Rawls, Sartori was very critical of the utilitarian tradition and its “petty hedonism” and considered the association between liberalism and utilitarianism made by British political theory during the Enlightenment “a disgrace.” There was definitely a convergence between Sartori and Rawls on the lexicographic priority of liberty over equality. A second – if less close – parallelism has to do with the “sense” (Rawls) or “ethos” (Sartori) of justice. Rawls defines it as the moral capacity to judge things in terms of just and unjust; Sartori as a sensitivity to the issues of inequality, a modus vivendi of a democratic society. Both believe that they are important for sustaining any scheme of cooperation.

The two authors start to diverge when it comes to the principle of equality of opportunity. Sartori fully endorsed the principle of equality of access (“careers open to talents”) but was reluctant to subscribe to equality of starts. In the second part of his second principle of justice, Rawls talks about fair equality of opportunity, meant to fight arbitrary social and economic advantages. Sartori criticises Rawls’ “careful smoothing” of the distinction between equality of access and equality of starts, arguing that his own strong opposition between the two “permits a better assessment of where authors actually stand” facing clear-cut alternatives (TDR, 364, ft. 25).

The first part of the second principle (known as the “difference principle”) prescribes that meritocratic rewards are admissible only to the extent that they turn to the advantage of the worst-off. Rawls argues that this principle expresses a conception of reciprocity (Rawls, Reference Rawls1971, 102). The difference principle renders the scheme of cooperation reasonably acceptable to everyone in the original position.

Sartori remained quite sceptical about the difference principle. When addressing the issue of the less fortunate as bearers of needs, he endorsed a sufficientarian approach: “the least fortunate should be ensured minimal conditions for a decent life, above sheer survival and yet below the level of desired and satisfying wants” (TDR, 350). In his view, Rawls’ concept of “primary goods” – to be equally distributed – is too elastic, as it extends to what people in a well-ordered society “may be presumed to want whatever their final ends” (TDR, 365, ft. 38). Sartori's worry is that – since the operative definition primary goods would be made by the state – the open-endedness of the Rawlsian formulation might lead to “any conceivable arbitrariness and partiality of treatment” (TDR, 352). Yet, Sartori does sympathise with Rawls’ notion of “compensatory reciprocity,” arguing that it is complementary to his own proposal of “rebalancing inequalities.” The sympathy may be related to the “ethos of justice” notion. However, it is more likely that Rawls’ reciprocity – meant in a descriptive sense – is congenial to the rebalancing argument, understood as a strategy for safeguarding social cooperation and political stability.

The rebalancing argument brings Sartori close to another prominent participant of the debate on egalitarian liberalism, Michael Walzer. In Spheres of Justice (Reference Walzer1983), this author defended the idea of complex equality. There cannot be a single overarching criterion of relevant difference (equality of what?). Society is composed of different institutional spheres within which certain specific goods are valued, driven by their internal logic of distribution. A just society rests on a careful separation of spheres, to avoid the unjust conversion of advantages from one sphere to the other.

While Walzer's argument proceeds through the frequent use of examples, Sartori's argument about balancing inequalities remains instead at a general level: it is not clear how his proposed system could work in practice. He does suggest, however, that his argument parallels, precisely, that of Walzer, thus presumably involving a degree of institutional inter-sphere separation.

Building blocks for a theory of equality politics

Prima facie, Sartori's second conception of equality in TDR does not go beyond conceptual analysis, punctuated by some normative statements which are basically linked to his “value choice” about the primacy of liberty. Somewhat dispersed throughout TDR, we find, however, the building blocks of an empirical theory about the politics of equality. This is, in my view, an original contribution of Sartori to the debate of his times.

Sartori's starting point is the ontological contrast, as it were, between liberty and equality. The former is a complex property, typically assuming the ability to choose among different options. Equality is instead a seemingly simple property, which can be observed by comparing two entities under this or that aspect. We can reply to the question of what is equal by “pointing to billiard balls and saying: these are equal” (TDR, 338). Understood in terms of sameness, equality can be ascribed to any pair of entities, depending on the aspect taken into account. Any effort to make entities more equal under one aspect is bound, however, to leave or generate inequalities in other aspects. While the quest for liberty and other ideals tends to reach a point of saturation (think of the criterion: maximum individual liberties compatible with the liberties of every other), equality is an insatiable ideal, which drives an endless race.

Normative theories provide criteria of “ideal” selection. Not so for empirical theories. “Equality in politics and via politics requires to deal with … those particular equalities that human beings have sought to establish in the course of their history” (TDR, 341). Relevance coincides with de facto, observable relevance, resulting from struggles for the repudiation of certain differences considered as clearly unfair and implicitly remediable.

This descriptive statement provides a criterion for specifying which inequalities should be rebalanced. The choice is shaped by two factors: (1) the historical change of the sense of justice concretely prevailing in a given phase and/or (2) the type of disparities that are resented in that phase, as opposed to those “which pass unnoticed … or are deemed to be irremediable […]. A system of reciprocal cancellation of inequalities is always organised, historically, in response to changing values and priorities regarding what is deemed to be just” (TDR, 357). In Rawls, compensatory reciprocity is an obligation stemming from the need to incentivise social cooperation. In Sartori, ironing out “resented” disparities is a condition for managing those context-specific distributive conflicts which might jeopardise political legitimation and democratic stability.

Liberal democracy is the system which offers the greater margins for the expression of grievances about inequalities and the quest for their redress. Liberal guarantees see to it that the contest for more equality takes place in a peaceful, free and orderly way. “Yet no sooner does a situation of liberty open the way to the appetite for equality than the ideal of liberty finds itself at a disadvantage and the appeal of equality proves stronger” (TDR, 358). Equality has a tangible meaning (typically material benefits), while liberty cannot, at least as long as it is guaranteed and enjoyed. Moreover, redressing inequality requires the manifest hand of the state. Electoral competition tends to encourage sectional and bloc-oriented legislation. This can cause additional inequalities, not to speak of the possible obfuscation of the costs of redistribution. The insatiable race for equalities can generate an irresponsible politics, potentially able to jeopardise the very foundations of a market-based liberal democracy. During the early 1970s, Sartori was working at his second masterpiece, Parties and Party Systems (Reference Sartori1976). The logic of what he called “polarised pluralism” was a perfect illustration of irresponsible politics: an incessant escalation of distributive appeals, “aimed at bidding support away from partisan rivals by promising increasing shares of the available supply, while the supply does not increase” (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976, 124).

Conclusion

In TDR, Sartori has outlined a richer and more systematic conception of equality than in his previous works, entertaining a close dialogue with the intellectual debates of the times. The conception rests on a clear analytical framework, from which various descriptive propositions – as well as possible fallacies – are logically derived. Although frugal in terms of concrete examples, Sartori identifies some original and insightful mechanisms typically driving equality-seeking behaviours. In the context of a rising consensus about liberal egalitarian conceptions of distributive justice, Sartori defended a liberal democratic view based on the primacy of freedom, which acknowledged to equality the status of a facilitating condition, but also warned about its potential threats. The point still holds, but in light of recent developments, Sartori's conception could be improved by reflecting on the threats coming from the opposite direction, i.e. rising levels of inequality and socio-economic polarisations (Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2017).

Sartori's theory was influenced by the Zeitgeist in which it was produced. His interest in equality, in its relation with liberty, was subordinated to its overarching preoccupation with the danger of political oppression, the chances of survival of liberal democracy in a historical context still characterised by the Cold War. The final chapters of TDR are mainly devoted to challenging the notions of socialist planning and popular democracy.

As is known, in recent decades, democratic theory has shifted its focus towards other topics, most prominently that of “quality” (Diamond and Morlino, Reference Diamond and Morlino2004). The debate on quality has unpacked a number of dimensions (regarding procedures, content and results) through which democratic ideals are realised, in various empirical combinations. In this perspective, equality and social justice play a more positive role than in Sartori's conception: they are seen as necessary components – on a par with civil liberties and participation rights – of a self-reinforcing “system” of features which sustain the democratic regime.

The concept of democratic quality has definitely pushed forward the frontiers of the debate. But it does remain an offspring of the tradition inaugurated by Giovanni Sartori, attesting to its outstanding theoretical fertility.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Competing interests

The author declares none.