The first transmission of the Sekondi-Takoradi Broadcasting Service in 1937 was a strange blend of solemn occasion and variety show. Dance band highlife from the Nan Shamaq Orchestra, pianoforte solos by Mrs. Fossey, and six minutes of harmonica by Mr. Lawless were interspersed with speeches from local notables who enthused about the power of modern technology to transform humankind.Footnote 1 In one of the earliest radio broadcasts by an African, the tufuhene of Dutch Sekondi pronounced a “leap in the van of civilization” which promised to “make unhappy homes lively and, whilst educating families in a certain manner, keep them together.”Footnote 2 The governor of the Gold Coast was also in an expansive mood. Arnold Hodson was not only a radio fanatic but a keen amateur dramatist whose fantastical radio pantomime The Downfall of Zachariah Fee is still remembered by early listeners.Footnote 3 With an eye to the theatrical, his speech introduced radio technology as being “very similar to the magic stone we read of in fairy tales [as] we press a button and are transported to London: again we press it and hear grand opera from Berlin.” Like the tufuhene, Hodson also saw the family home as a crucible of modernisation. He invited listeners to

imagine what an influence this will have from the psychological view. Mothers, when the children have been fractious, or when they have had a trying day cooking and washing clothes, or men who have had a hard day’s work will sit down, after a bath and good dinner, and listen to first-class music which will banish their cares and make them forget all their worries.

The new service was designed for two audiences. Evening programme content would appeal to all the family but Hodson announced that daytime programming would “amuse and interest the ladies when their husbands are away at their offices or work” with “orchestral music and important speeches which are being made by Cabinet Ministers and others at official lunches in England.”Footnote 4

The prandial perorations of ministers may have made for turgid listening but the pioneers of radio in Ghana took the task of recruiting female listeners seriously, as elsewhere in colonial Africa. Early broadcasters in Zambia, for instance, also claimed to “look upon women listeners as among the most important of the listening groups.”Footnote 5 This article uses a comparative method to argue that despite its egalitarian aspirations, colonial radio had an uneven impact on African women. The first study to take a gendered approach to the history of radio listening in Africa, it demonstrates that the social profile of early African audiences was shaped by divergent development policies implemented between the 1930s and the 1950s.

Ghana and Zambia are unusual subjects for a comparative history, but they are uniquely well-suited to an inquiry into the social impact of radio as they were the only countries to conduct national development schemes to promote affordable sets before the 1960s. In Ghana the construction of a wired rediffusion system (RDS) produced an audience of equal numbers of men and women but in Zambia a scheme to promote battery-powered “Saucepan Special” wirelesses inadvertently created barriers to female listening and resulted in a male-dominated audience. From a continental perspective, Zambia’s adoption of a wireless system was typical of the rest of Africa, where wireless radio was and remains the norm, while Ghana’s reliance on the now-obsolete technology of wired loudspeakers was unique and seems, in retrospect, arcane. By comparing a typical case study with an outlier I demonstrate that radio comprised a plurality of technologies in its early days and that the technical choices made by its architects resulted in profound and lasting differences in the profile of audiences, the voice of broadcasts, and the experience of female listeners in the two countries.

That radio sets should be understood as objects in physical and social space has been argued convincingly by anthropologists, notably Deborah Spitulnik, who characterised them as “mobile machines” in her study of Zambia in the 1980s.Footnote 6 This premise provided the inspiration and starting point for my own research into the gendered past lives of radio sets as manly machines or homely objects. To unearth the social history of radio technology I apply gender history methods to government and broadcaster archives and oral history interviews in Ghana and Zambia, local newspapers, and the BBC’s Written Archive. Quantitative data generated by contemporary audience surveys is a good starting point for historians of audience but few surveys were conducted before the mid-1960s and it was rare to record the gender of listeners at the time. To overcome the limitations of this archive I triangulate the small number of relevant surveys with government estimates of numbers of radio sets (a more reliable metric as new sets were subject to import duties), imaginaries of audience in newspaper advertisements for radio sets, and oral history interviews with a randomised group of twelve people in Accra and fifteen in Lusaka and Kafue who remembered listening in the 1950s or earlier. Surprisingly, oral history interviews with female listeners have been almost entirely ignored as a source by historians of radio.Footnote 7 My participants were a small and non-representative sample but their testimonies offer a rich sense of the range of listening experiences in a wide variety of geographical locations and social contexts. My research also uses interviews with retired broadcasters and broadcast content to analyse the gendered voice of radio.

The historical relationship between development, technology, and society in Africa provides the central enquiry of my study. Historians of development commonly make the argument that state-led projects failed to benefit their intended recipients.Footnote 8 They also concur that the structures of colonial rule and the impact of late-colonial development tended to advantage men over women even in countries that had established matriarchal traditions, such as Ghana and Zambia, because women were denied political participation and marginalised in wage labour economies.Footnote 9 This was particularly apparent in settler colonies like Zambia where officials had a paranoid fear of single women in urban spaces and sought at first to exclude women from towns using legal codes and intimidation, then later to incorporate urban women into a European imaginary of the “modern family,” with men as wage-earning heads of the household and women as stay-at-home wives and mothers.Footnote 10 Officials in Ghana were also concerned to promote patriarchal visions of the ideal family, as demonstrated by Hodson’s comments above, but here the social and economic marginalisation of women was less acute thanks to a longer history of women living and working in urban spaces especially as market traders, mission education for girls, and a greater interest in women’s issues on the part of the anticolonial movement.Footnote 11 Histories of development have tended to pay little attention to media infrastructure projects and scholarship on women’s history in Africa has overlooked the ways in which technological change shaped gender relations. My research makes a major contribution to these fields, first by highlighting rare examples of late-colonial development projects that actually benefited Africans and, second, by demonstrating that new media technologies played an important role in reinforcing the patriarchy of settler colonialism in Zambia while in Ghana, by contrast, they improved women’s access to the public sphere.

The history of African radio is a growing field of scholarship. Much of this research has been concerned with radio as a tool of political control, sometimes undermined by individual broadcasters or writers acting as intermediaries between nervous states and critical audiences, or by political exiles operating cross-border “guerrilla radios.”Footnote 12 A handful of studies have also considered the relationship between radio and development, either as a vehicle for education, public health, and agricultural campaigns or as development goal in its own right, especially in the era of postcolonial “nation-building.”Footnote 13 However the role of radio in colonial development schemes remains under-researched, with the exception of Marissa Moorman’s research on Angola.Footnote 14

Even less attention has been given to the gendered impact of radio in Africa. Liz Gunner has highlighted the ways in which female broadcasters shaped the voice of Zulu radio and how radio dramas offered a space for negotiating femininity and modernity in South Africa, despite their patriarchal agenda.Footnote 15 Like Gunner I use voice to explore the lasting legacy of early technologies on the sound of broadcasting. Historians of radio in Africa have so far given no attention to female audiences so I draw on Kate Lacey’s approach in her influential study of female listenership in the German interwar period. Lacey challenges Jürgen Habermas’s conception of an inclusive, unitary public sphere by reconfiguring the female audience as a “public” in its own right, excluded by a divisive and male-dominated national discourse. In Germany, Lacey found that carving out a “domesticated, maternalized space” on the airwaves for “women as women” rather than citizens “underscored the conventional gendered separation of the public-private divide” which excluded women from national politics.Footnote 16 Other historians have applied this argument to interwar Britain and I argue below that Lacey’s analysis also applies to Zambia in the 1950s.Footnote 17 By contrast, the boundary between gendered “publics” in Ghana was more blurred, as has been observed of the United States, Argentina, and Uruguay from the 1930s.Footnote 18 A comparison with the colonial press which, aside from women’s columns, was heavily male-dominated in both countries also highlights the exceptional significance of the femininity of Ghana’s early radio culture.Footnote 19

Historical studies of radio technology in Africa are scant and tend to overlook the question of impact.Footnote 20 Susan Bowden, David Clayton, and Alvaro Pereira’s quantitative work on the consumption of radio sets in British colonies in the 1950s is exhaustive but I take issue with their conclusion that the decision to prioritise wired or wireless systems had little impact on audience.Footnote 21 Brian Larkin’s history of wired rediffusion in Kano City offers a unique account of the disjuncture between the colonial state’s fascination with loudspeaker systems as a figment of the “colonial sublime” and the practical failings of the technology. “Saucepans” and RDS boxes could also be unreliable but his focus on the politics of the “gap between the fantasy of technology and its all too real operation” obscures the transformative social impact of the technology, however imperfect.Footnote 22 Histories of radio rarely make the connection between technological variations and the gender profile of audiences, partly because they are dominated by the early adopters, especially the United States, Britain, France, and Germany. Here wireless technology did not produce male-dominated audiences as mains electricity was readily available and listeners did not have to rely on expensive batteries.Footnote 23 I demonstrate below that the dominance of the Global North in the scholarship on radio technology has obscured the distinctive experience of battery-operated wireless listeners in regions where electrification came much later if at all and batteries remained the “critical cost bottleneck in the diffusion of radio listening.”Footnote 24 The leading examples of “wired wireless” systems were the USSR and Communist China where, as in Ghana, it appears that radio attracted a more balanced audience of men and women.Footnote 25

In the first section I compare the evolution and success of radio set development projects in colonial Ghana and Zambia. The second section analyses quantitative evidence for the gendered nature of audience and the third section explores the social impact of different radio technologies to account for the divergence between Ghana and Zambia. In the last section I compare advertisements for radio sets and the voice of broadcasts to demonstrate that the gendered profile of listenership had a lasting legacy on radio culture. The Gold Coast achieved independence in 1957 and Northern Rhodesia in 1964 but for the sake of simplicity I use “Ghana” and “Zambia” throughout.

Colonial Development and Radio

British colonial broadcasting was originally intended to serve an exclusively white audience of settlers and expatriates when it was launched in the 1920s. But the social and political disruption of the Great Depression persuaded officials in London to adopt a new policy of using radio for the “enlightenment and education of the more backward sections of the population and for their instruction in public health, agriculture, etc.,” and as an “instrument of advanced administration” or, in other words, political control.Footnote 26 These concerns were sharpened during the Second World War when it became apparent that Axis powers were using broadcasts to foment anticolonial agitation. The Colonial Development and Welfare Act of 1940 allocated £1,000,000 to support the development of colonial broadcasting, which was mostly spent on improving the quality of local transmitters used to relay the BBC’s General Overseas Service, mirroring the approach taken in other European empires. Ghana, Zambia, and Kenya also saw early experiments in vernacular broadcasting.Footnote 27 This was all very well but, as many local officials observed at the time, there was no point investing in broadcast output at a time when hardly any Africans owned radio sets.Footnote 28

In Ghana and Zambia officials took the challenge of creating a mass colonial audience more seriously than elsewhere on the continent. Their inspiration was a short-lived Indian development scheme to provide villages with communal preset wirelesses in the early 1930s, which in turn drew on a much more successful Soviet policy of “radiofication” that used the telephone network model to connect local relay stations to wired loudspeaker boxes in homes and public places from the 1920s.Footnote 29 This form of radio broadcasting—known as rediffusion or “wired wireless”—is now largely forgotten but it had a brief period of popularity across Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, and in a handful of smaller British colonies such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jamaica.Footnote 30 RDS was common in the USSR until the 1960s, and China extended a vast wired network to rural areas in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 31 Later in the twentieth century RDS radio evolved into cable-television.

Radio was launched in Ghana in 1935 at the peak of RDS’ brief period of popularity. Most early radio networks in Africa, including in Zambia, used wireless transmission as they were designed to serve a disparate white settler population that could afford expensive sets. In Ghana, by contrast, Hodson chose to adopt the wired RDS model with the aim of making radio accessible to African listeners without risking exposure to potentially-subversive external wireless stations. If there was more than a hint of Soviet “radiofication” about the scheme, Hodson also drew on the recent success of experiments with RDS in Lagos and earlier under his own governorship in Freetown and the Falkland Islands.Footnote 32 Small-scale urban RDS networks were soon built in Kaduna, Kano, Nairobi, Johannesburg, Durban, and the Copper Belt. But Hodson’s vision of wires reaching even the remotest villages was uniquely ambitious in the colonial world, and Ghana became the only African country to develop a wired network on a national scale.Footnote 33 Expansion of the system stalled in the 1940s due to wartime constraints, Hodson’s departure, and a BBC-led commission which recommended abandoning wired broadcasting in 1952. But after his election victory in 1951, Kwame Nkrumah’s new Convention People’s Party government embraced the technology as an affordable option for poorer listeners and an effective method of political control. While RDS was being abandoned elsewhere, the Ghanaian system doubled in size during the mid 1950s and, after a second period of expansion in the late 1960s, the network covered most urban areas and many surrounding villages up to a distance of around ten kilometres.Footnote 34

RDS boxes did not require mains power so the system was extended much further than the electricity network and since the boxes did not use batteries either, listeners could leave them on as much as they wanted.Footnote 35 There was also a short-lived network of public loudspeakers or “radio kiosks” in markets, community halls, and lorry parks.Footnote 36 The up-front costs were carried by the government and listeners paid a monthly subscription fee of five shillings, which was affordable for many middle-income families.Footnote 37 The RDS was supplemented by a wireless service called Station ZOY which was initially established in 1940 to carry Free French broadcasts to Vichy-ruled West Africa.Footnote 38 According to official estimates a majority of Ghanaian listeners used RDS rather than wireless sets until the mid-1950s and in urban areas RDS boxes dominated until the early 1960s.Footnote 39 The RDS was overtaken by popular demand for new transistor sets from around 1960, which caused the number of wireless sets to rise from 130,000 in 1960 to 900,000 in 1970, but the Ghanaian government continued to expand wired broadcasting into the 1970s and maintained it into the 1980s.Footnote 40

In Zambia a small number of wired loudspeakers were installed in community halls and in mining compound beer halls from 1945 but these spaces proved too noisy to attract significant audiences.Footnote 41 Instead, when Zambia launched a national radio project in 1949 it used wireless technology and relied on battery power. The choice to use wireless transmission was dictated by the existing media landscape of settler colonialism and changes in radio technology since the 1930s. Unlike Ghana, Zambia had a significant audience of white listeners who had been tuning in to short-wave external stations on bulky, mains-operated sets since the 1920s and practically no Black listeners until the 1950s. When Zambia’s first radio station was established in 1941 the colonial government chose to use long-distance short-wave transmitters as it was designed to serve Black listeners in Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland as well as the home audience. Behind this decision lay the settler political agenda to federate all three territories into a white-dominated Dominion united, in part, by what became known as the Central African Broadcasting Corporation, alongside other totemic development projects such as the Kariba Dam.Footnote 42 Meanwhile wired rediffusion had gone out of fashion in Britain in the 1940s, batteries had become cheaper, and the Nazi government had successfully flooded Germany with wireless “Volksempfänger” (People’s Receiver) sets.Footnote 43 While the capital and maintenance costs of Ghana’s RDS were mainly funded by the taxpayer and topped-up by listener subscriptions, in Zambia the Information Department managed to harness market forces with minimal outlay. The “Saucepan Special” scheme was launched in 1949 as a de facto public-private partnership with the American battery firm, Ever Ready, drawing on the German model of the 1930s. The project was the brainchild of Harry Franklin, the director of the Northern Rhodesia Information Department, who was a radio enthusiast and maverick in the mould of Arnold Hodson.Footnote 44

The “Saucepan Special” valve set was intended to be robust and cheap enough to be popular with African consumers, earning its name from its rounded metal casing that was intended to withstand termites and hard knocks. The Information Department ordered sets in bulk from Ever Ready, exempted them from customs duty, and sold them on through private retailers for a minimal profit at £5 for a set. African owners were also entitled to a fixed-rate government repairs service at minimal cost.Footnote 45 The Saucepan was about half the price of the cheapest commercial equivalent and brought radio within reach of many middle-income Zambians.Footnote 46 Sales of Saucepans increased exponentially through the 1950s until they were eclipsed by cheaper transistor sets around 1960.Footnote 47 In 1948 Franklin estimated that only 20-30 Africans owned sets but by 1954 approximately 13,000 Saucepans had been imported and by 1957 as many as 50,000 sets had been shipped to the Central African Federation, mostly to Zambia.Footnote 48 This impressive rate of growth meant that the Saucepan scheme had caught up with and possibly outstripped Ghana’s twenty-year-old RDS project in only seven years, although in practice as many as half of the sets may have been bought by white settlers.Footnote 49

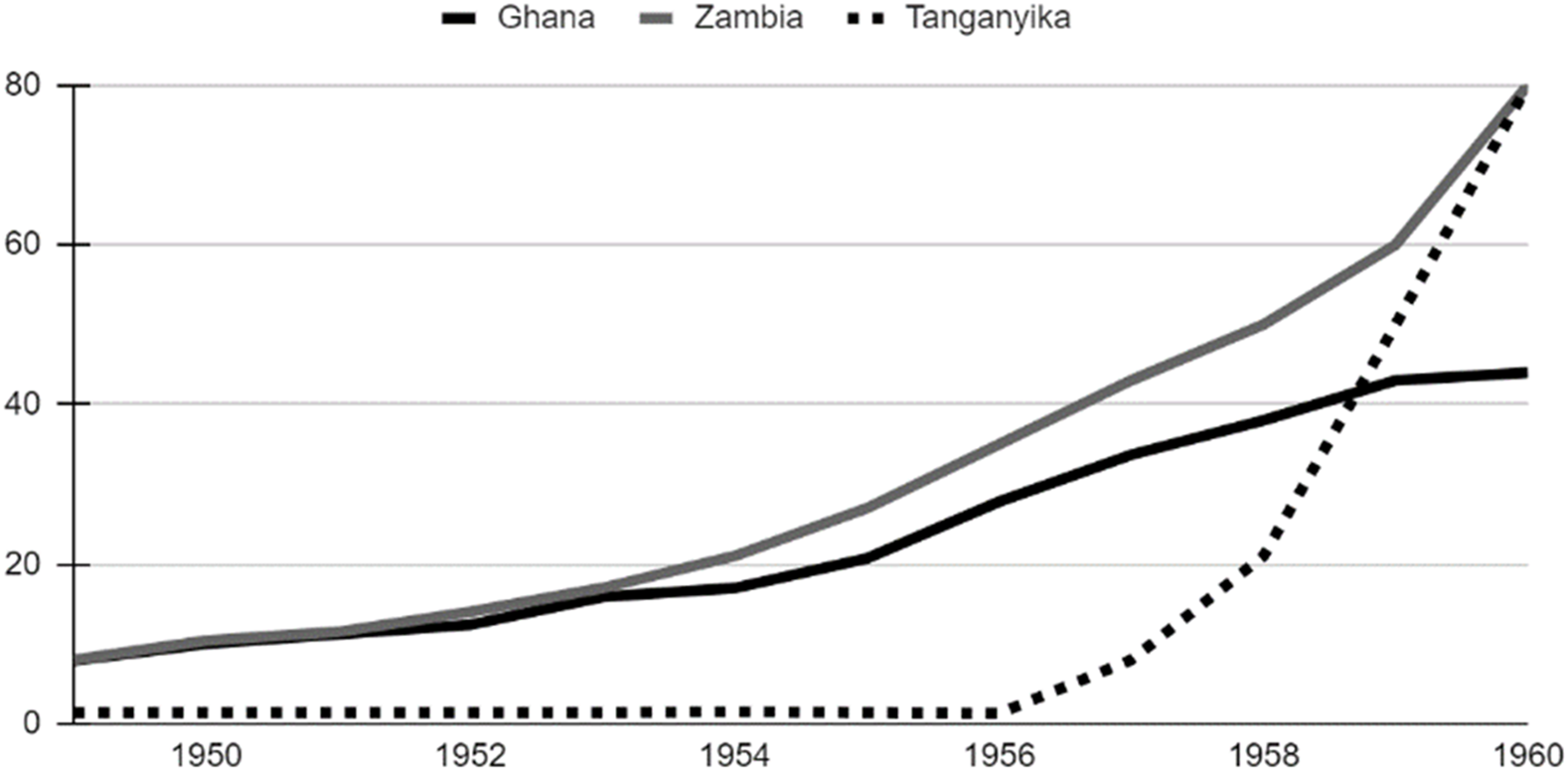

Beyond these basic figures it is difficult to make a quantitative assessment of the success of these two development schemes but a comparison with colonial Tanganyika is helpful, as illustrated by Figure 1, below. Tanganyika had no radio development projects during the colonial period and levels of ownership remained insignificant until technological change and popular demand created the transistor boom at the end of the 1950s. The number of wireless sets in Tanganyika caught up with RDS boxes in 1959 and Zambian wirelesses in 1960, although the expansion of radio ownership in Tanganyika was much less impressive in per capita terms as its population was nearly twice as large as Ghana and four times larger than Zambia.Footnote 50 On this metric it took Tanzania until 1967 to achieve ownership levels comparable to those seen in Ghana and Zambia in 1959, thanks to a government scheme to provide ujamaa villages with sets from the late 1960s.Footnote 51 Tanzania was a poorer country so it is difficult to compare like-for-like but this analysis suggests that without state intervention Ghana and Zambia would probably have seen desultory growth of audiences until the late 1950s.

Figure 1. Radio sets (1000s) in Ghana (RDS loudspeakers only), Zambia and Tanganyika, 1949–60.

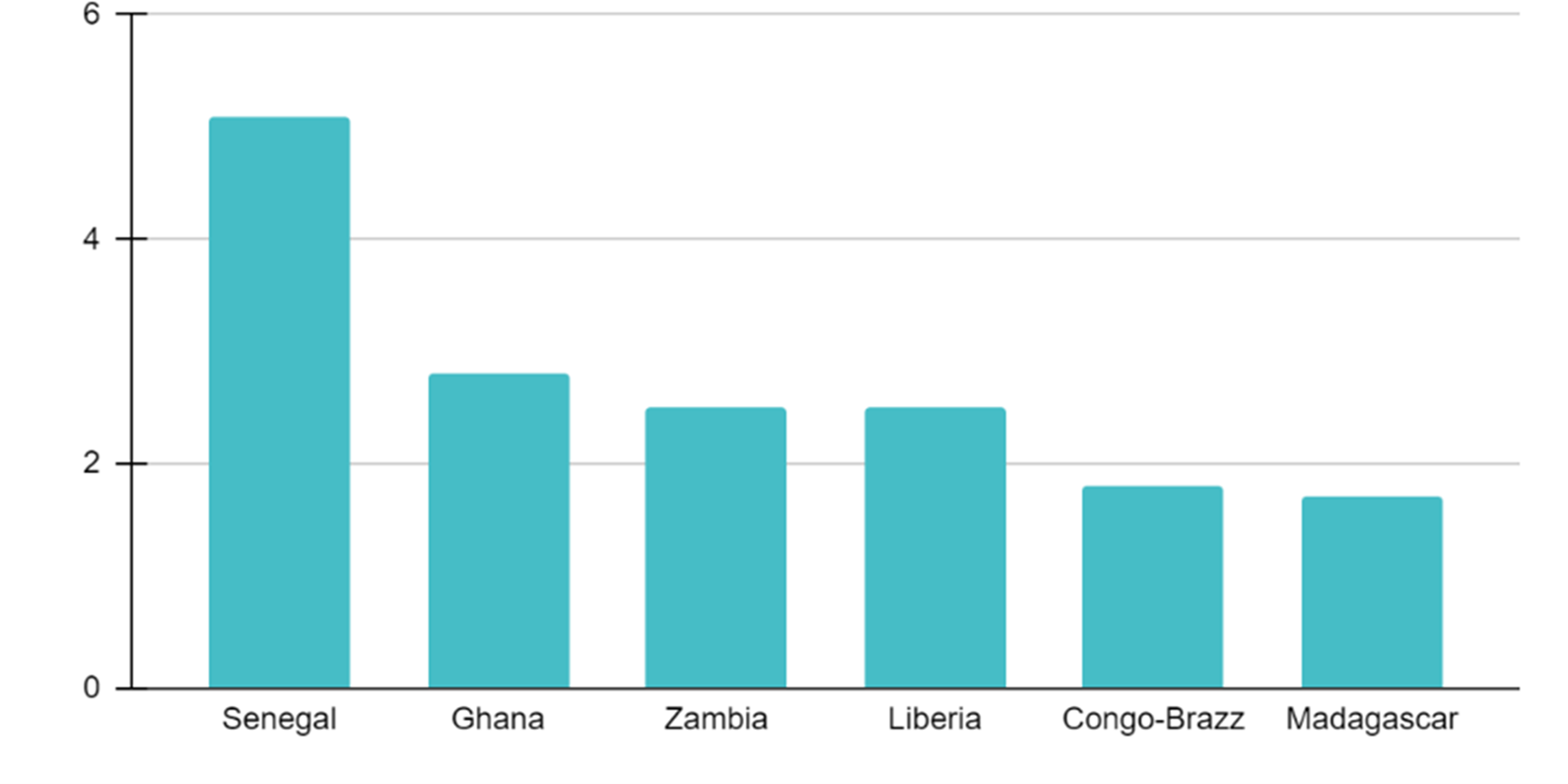

Figure 2. Radio sets per hundred population in countries with rates above the African average, 1959.

The development schemes in Ghana and Zambia produced exceptionally high levels of African radio ownership in continental terms. By 1959 Ghana had 2.8 sets per 100 population and Zambia 2.5 at a time when the continental average was 1.6, as illustrated by Figure 2, below. These figures were particularly impressive since the only other countries to achieve comparable rates of ownership were those that hosted powerful transmitters installed by international stations, which gave unusually good local reception.Footnote 52 Translating set numbers into audience figures requires some guesswork but observers at the time found that collective listening was the norm with groups of around seven or more listening to a single set.Footnote 53 This gives a conservative estimate for the national radio audiences as being around a fifth of the population in both countries in 1959. By 1970 perhaps half of Zambians and nearly all Ghanaians were listening regularly.Footnote 54 The most impressive local results were seen in urban areas. Half of the residents of Luanshya Township on Zambia’s Copper Belt were regular listeners by 1952.Footnote 55 In 1955 around a fifth of the population of Accra listened to RDS boxes regularly (including children), and in 1960 a third of adults aged over 15 had an RDS box in the house and 50 percent of the population listened daily.Footnote 56 These figures are approximate but they reveal that colonial development schemes in Ghana and Zambia created a mass African listening culture in the 1950s about a decade before most other parts of the continent, where radio remained the preserve of social elites or white settlers until the arrival of transistors.

Gendering Audience

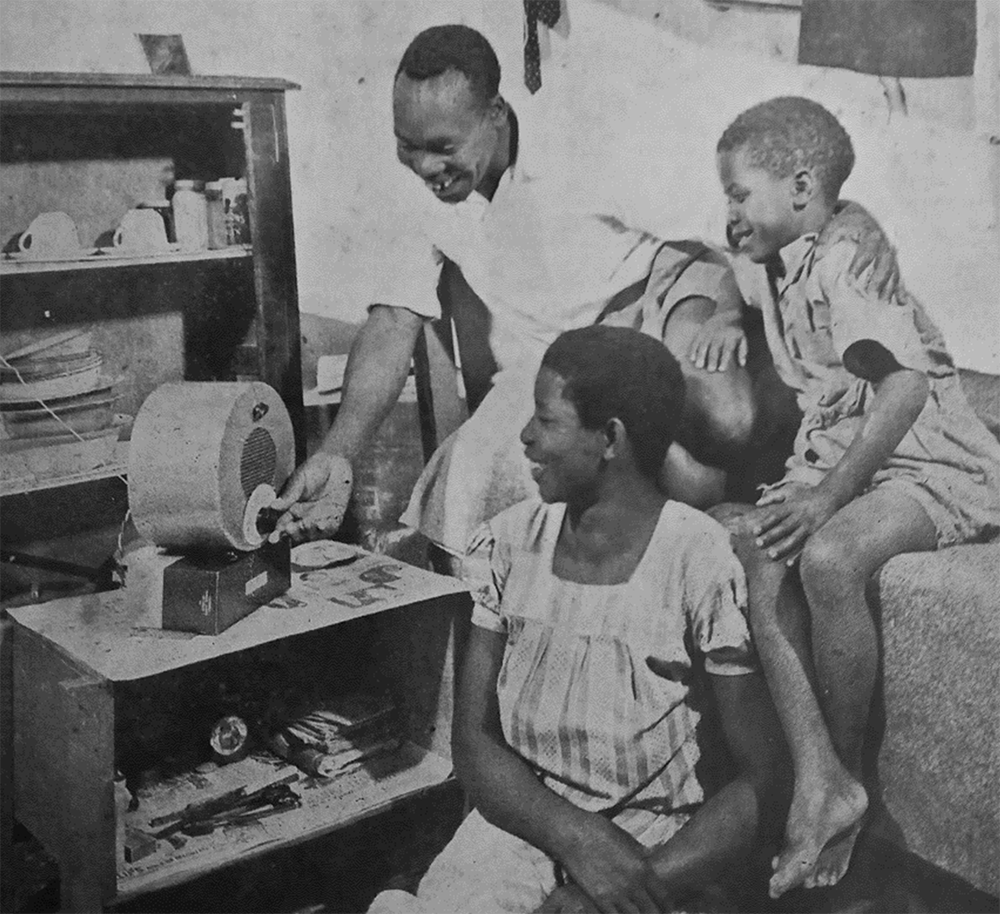

Figures 3 and 4, below, are rare examples of images of early radio listening which were published in promotional brochures by the Northern Rhodesia Information Department and the Ghanaian Ministry of Information.Footnote 57 Both locate the radio set at the heart of domestic family life, but while the focal point of Figure 3 is the husband’s arm reaching down to tune the Saucepan, in Figure 4 neither adult is controlling the set and it is the RDS wire that leads the eye to the loudspeaker box. The fragmentary archives of early listenership reveal that these images typify the ways in which radio technologies were gendered.

Figure 3. Family with “Saucepan Special,” 1952.

Figure 4. “A family listen attentively to a Radio Ghana programme on a Wired Service loudspeaker Unit,” 1964.

Audience surveys are an obvious starting point for this enquiry. In 1955 the Gold Coast Broadcasting Service (GCBS) management admitted that it was “woefully ignorant of the audience and of their listening habits” since “no basic research had ever been done.” J. W. B. Kpohanu, a recent economics graduate, was appointed as listener research officer to study RDS users in Accra and three nearby towns, Swedru, Winneba and Keta. Over eight months he and his assistant, Paulina Clark, interviewed 622 subscribers. Kpohanu and Clark found that although nearly all the subscribers were male, each RDS box had a large average audience of nine listeners which was “fairly evenly divided” between men and women.Footnote 58 This striking observation was echoed by larger surveys in the 1960s.Footnote 59

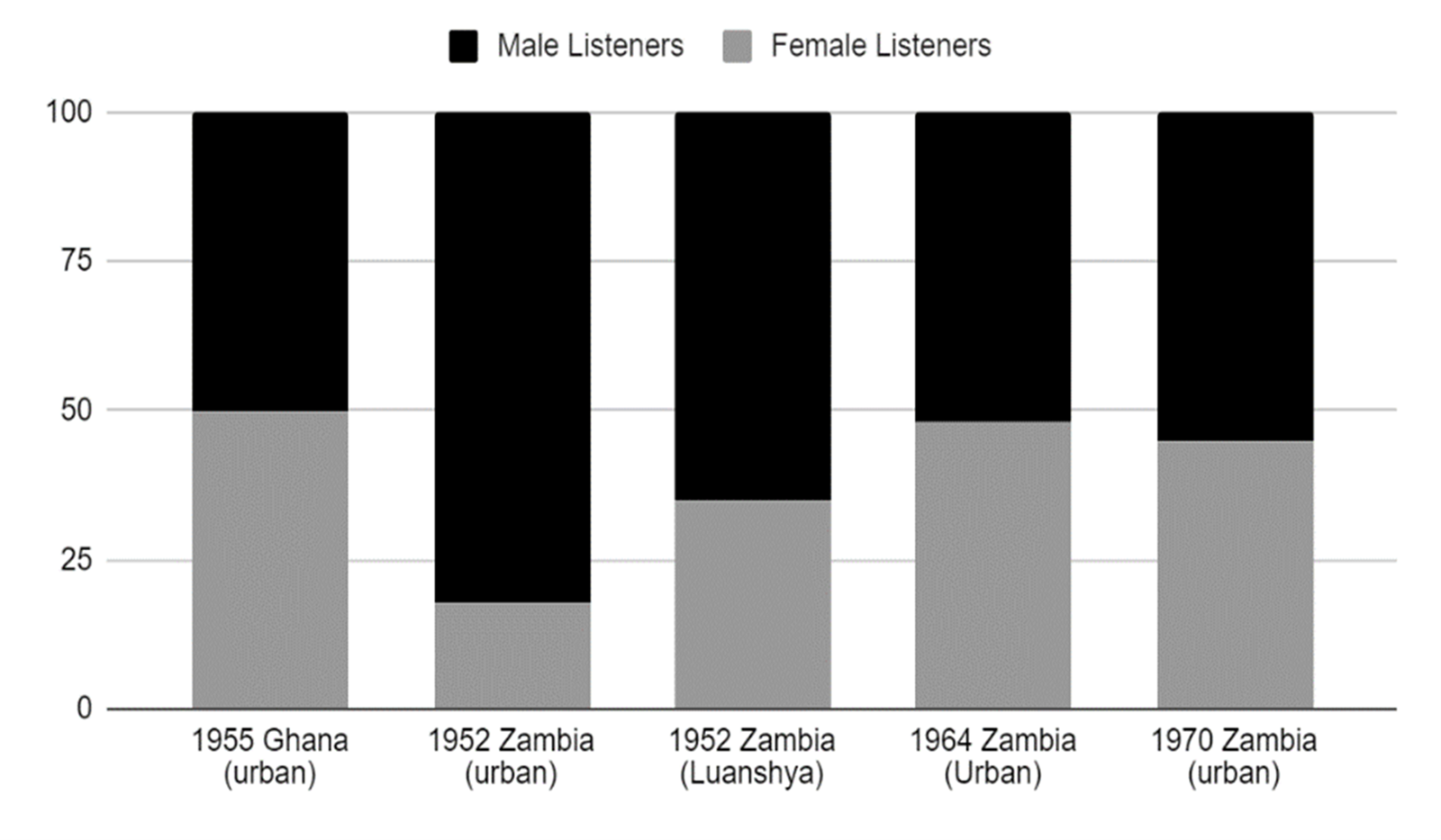

Archival traces of audience in colonial Zambia give a very different picture to Ghana. In 1954 the Central African Broadcasting Service (CABS) observed that “when broadcasts to Africans first started… it was noticeable that the men were not very anxious for the women to touch their wireless sets.”Footnote 60 There were no equivalent surveys to Kpohanu and Clark’s research in the 1950s but when the Information Department asked 5000 listeners about their favourite programmes in 1952, only 850 of them chose women’s programmes. Even if this group was entirely made up of women (and it is probable that some were men) this would suggest that women represented at most 17 percent of the national radio audience.Footnote 61 In the same year, Hortense Powdermaker conducted a local survey in Luanshya as part of her ethnographic study of life on the Copper Belt. Female listening here was higher thanks to the wealthy, urban profile of the mining township’s population, but Powdermaker found that only 35 percent of the radio audience was female while 65 percent was male.Footnote 62 By contrast, a survey of urban areas in 1965 found that total listening figures were similar for both genders, although daily listening revealed an ongoing inequality as men were 1.3 times more likely to listen on a daily basis than women.Footnote 63

Accepting the limitations of the archive, survey data suggests that the urban radio audience in Ghana comprised equal numbers of men and women in the 1950s, while the urban Zambian audience was dominated by male listeners until the 1960s, as summarised by Figure 5, above. Unfortunately surveys in rural areas did not quantify female audiences in either country in this period. However surveys conducted in the 1980s and 1990s reveal that rural women were more likely to listen to the radio in Ghana than in Zambia and it is reasonable to surmise not only that this divergence was historic but also that the ongoing presence of rural RDS networks in Ghana were an important factor.Footnote 64

Figure 5. Gender balance of listenership (percentage of total audience) in Ghana and Zambia, 1950s and 1960s.

Manly Machines and Homely Objects

It should not be assumed, however, that the growth of female audiences meant that women and men experienced radio technology in the same way. In this section I use oral histories to demonstrate that differences in radio technologies, patterns of ownership, and the ways in which sets were used in and around the home created and then perpetuated the gendered profile of early radio audiences long after numerical parity was achieved.

The wonderment inspired by the new technology was a memory common to all the women that I interviewed in Zambia but so too was a sense of frustration that men usually controlled wireless radio sets. Rosemary Mumbi grew up in a remote village in Muchinga Province in the east of the country in the 1940s and early 1950s. She recalled that,

we had those sets, we called them Saucepans, and the village gathered around this one hut which had a radio, mostly in the afternoons and in the evenings. The radio seemed to be a miracle, to listen to voices from so far away. Everybody believed everything they heard from the radio.

However Mumbi also remembered that in her village “the radio was controlled by the man because he owned the home and you did what he said,” and the villagers “believed it was a man’s world.”Footnote 65

Jennifer Chiwela recalled a similar situation in her village in Southern Province in the 1950s. Like Mumbi, she was “mesmerised by listening to a voice whose owner could not be seen; this was like magic” but she also saw that “women didn’t have as much time to listen to the [Saucepan] radio as the men did, because if they went to the field and came back together with the men they went straight to preparing the food, while the men were sitting [elsewhere] listening to the radio programmes.”Footnote 66 Elite, urban homes were the exceptions that proved the rule. Misael Kancheya was one of the first Black Zambians to graduate from the University of Zambia and went on to become a senior civil servant in the 1970s. He remembered that it was “common” for men to control sets but “in very few homes, those that were more enlightened it was much fairer.” He told me with pride that he let his wife listen to whatever she wanted.Footnote 67

Why was radio associated with patriarchy in Zambia? “We were just doormats” was Elizabeth Mwali’s only comment on the subject in a group interview with women who lived in the southern town of Kafue. For these women the radio set was located in a general culture of patriarchal influence, not only in the 1950s but for decades after. Ides Kalebwenta recalled that male control of the set was non-negotiable in the 1960s and 1970s because “it is our tradition that the man is the head of the house, ours is just to follow what the man does.” The main issue was that radio sets were typically bought by men as they had better access to formal employment and the cash economy, reflecting the legal and social structures of colonial urbanisation in Zambia which encouraged men to consider their earnings as personal rather than household income.Footnote 68 None of my interviewees could recall a woman buying a set before the 1970s. Lillian Lungu remembered that a gendered disparity in cash earnings still determined the ways that the wireless was used in her marital home in the 1990s. Lungu explained that “in those days the woman was [supposed] to be at home, nothing beyond managing a family.” But “a man goes to school, he gets a job, he buys a radio, so in the home the man was in charge of it and it is the man who can choose which programme you listen to.” The older women in the group agreed that Lungu’s experience had been typical of Zambian homes since the early days of radio.Footnote 69 These comments echo the findings of later ethnographic research. A study of middle-income urban women in Lusaka, for instance, found that male control of sets was still the norm in 1972.Footnote 70 In the same way, Spitulnik’s ethnographic study of rural villages in Northern Province in the late 1980s observed that men chose when the household radio was turned on or off, which programmes were listened to, and which channel it was tuned to. Spitulnik also came across women operating sets but only in an all-female setting and never when a man was present.Footnote 71

If male set ownership was a major barrier to female listening in Zambia, so too was the lack of electrification and the reliance of wireless sets on batteries which, like sets, were typically bought by men. As early as 1950, Franklin observed that “African owners have generally used their batteries very sparingly and the batteries are in fact giving rather longer life than the manufacturers claim for them.”Footnote 72 This was understandable in light of the excessive cost of early batteries, especially for power-hungry valve sets like the Saucepan in the pre-transistor era. While the Saucepan set was priced at only £5 in 1949, its battery cost £1 and 5 shillings so men exercised a residual control of the set even when they were out of the house.Footnote 73 This continued to be a problem for women as late as the 1990s. Lungu remembered that even then it was still the “man who used to buy the dry cells for the radio,” so “mostly the radios were never turned on until when he is home [because] you were worried you would use up the battery.”Footnote 74

My Ghanian interviewees also recalled that wireless sets were controlled by men but, by contrast, all of them confirmed Kpohanu and Clark’s observation that wired rediffusion boxes were used equally by men and women into the 1950s. With the advent of wireless transistor sets in the 1960s, the remaining RDS audience became increasingly dominated by women and children. Interviewees cited technical and social reasons for the gendered differences between wireless and wired audiences. For a start, RDS boxes could be left on permanently at no extra cost unlike Saucepans and other battery-powered sets. According to Kpohanu and Clark 70 percent of subscribers left their sets on all day in 1955.Footnote 75 Frances Ademola, now in her 90s, remembers walking through Accra from the late 1930s and hearing boxes “everywhere, from six o’clock in the morning when it came on automatically.” Although “you could turn the [on/off] knob,” subscribers in Accra “would never turn it” until “it went off in the night.” For Ademola, the sound of the RDS swiftly became “part of our lives” in urban spaces and especially after 1939 because “a lot of people had relations fighting with the British Royal West Africa Frontier Force in Burma” and they would eagerly listen for news. Ademola remembered that some boxes were left on “because people claimed that burglars wouldn’t come to the house when they heard a voice.” And although the “burglars got used to the idea of the voice, they were confused” as they “didn’t know if it was just the sound of the voice or whether there were other people there too, so it had a double purpose of giving security.”Footnote 76

Ademola’s household also kept the RDS box turned on permanently because it was used as a communal alarm clock: “this thing in the courtyard came on at 6 o’clock, and if you weren’t already awake it was a good time to know that you have to get up as the news would come on.”Footnote 77 Other listeners used their boxes in this way and also as a household clock through the day. Robert Ofori grew up in a village in Eastern Region in the 1960s and although his home was 10 kilometres from the nearest town of Nkawkaw his family had an RDS box. He recalled that

at six o’clock [am] it would announce “kon-kon-konkaro” [cockerel noise] and it would come. Then at that time it would change to English, they would do the news, then later they on they would translate it into Akan. So when you hear “Ghana Muntie, Ghana Muntie, Ghana Muntie” [call sign], that means it’s time, at six or seven and every hour they would announce “kon-kon-konkaro.” So if you are going to school you can check, ah it’s seven o’clock, it’s time to go to school…. The radio was on all the time except when it was closed so there was no need to off it.Footnote 78

On all the time and with only one available station, wired box technology offered subscribers few choices and were used as inanimate objects. As Beatrice Clottey put it, “we had access to only one station so no one really controlled it” in her childhood home in the small town of Obomeng in Eastern Region in the mid-1950s.Footnote 79 By contrast, Saucepans were machines that required operation and negotiation between their male owners and other family members. Not only did they have to be used sparingly because of the cost of batteries but, like most other early wirelesses in Zambia, Saucepans had short wave capacity and could easily pick up foreign stations, adding another element of choice. In fact the tuning dial of the Saucepan was designed to encourage transnational listening as it marked the frequencies of broadcasts from Lourenço Marques, Johannesburg, Dakar, and London, among others.Footnote 80 Although most RDS subscribers were male, the limited nature of the technology meant that they did not have the opportunity to exercise the gendered agency that wireless set owners enjoyed in Zambia.

Women also had better access to radios in Ghana thanks to their fixed presence in the home. Boxes were typically installed in the living room or in the central yard of larger compound, in part for ease of listening but also to comply with the terms of RDS subscription contracts which stated that government agents “must be allowed to enter premises at all reasonable times for the purposes of inspecting and testing the installation.”Footnote 81 Radio technology has been widely credited with blurring the boundaries between the public and private sphere and the physically invasive requirements of Ghana’s RDS are an extreme example.Footnote 82 But as a result, boxes were commonly located where women performed the labour of the house and they could easily be heard throughout the day by a heterogenous, homely audience. By contrast, Saucepans were mobile and could be carried away by their owners for an audience that was more private and select, as Spitulnik later noted of transistor sets.Footnote 83

Ghanaian listeners remembered the social impact of the location of RDS boxes. Kwame Karikari, who later became director general of the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC), was a child in Akyem Awisa in Eastern Region during the 1950s. In 1952 his family had a box installed on an external wall in the central courtyard of the house, which was a compound with eighteen rooms and multiple families. At 6 p.m. the men of the house would come and sit in the courtyard to listen to the evening news in Twi but otherwise the audience was usually women and children. Karikari did “not remember them sitting down to listen to radio but as they went about their chores they would listen” and “some of the women would hum along to the music” when they were cooking or sweeping.

By contrast, wireless sets were seen as manly machines as in Zambia. When Karikari’s father, a construction technician for the Public Works Department, bought a battery powered short-wave transistor set in 1960, the household audience became more gendered. Karikari had no memory of the women being allowed to listen to “my father’s wireless set.” Of an evening his father and the other men of the house would sit and listen to the news on the BBC, Nigerian music, or football in the sitting room or on the verandah, while the women and children listened to the RDS in the courtyard. When the men were out at work during the day the wireless set was kept off.Footnote 84

Mike Eghan, a famous Ghanaian radio personality and DJ from the 1970s, grew up in a more elite social setting in Sekondi-Takoradi in the 1940s but he remembered a similar techno-gendered division. “We had a rediffusion box,” Eghan remembered, “but my father had an electronic [wireless] radio.” The RDS box was always “turned on but he wouldn’t listen to it, it was meant for the rest of the family,” as his father, a civil servant, “would rather listen to the BBC news and cricket and football” privately.Footnote 85 Frances Ademola also grew up in an elite household, although her home was a compound like Karikari’s, with a “courtyard, a communal place, and tenants on the ground floor and our family lived upstairs.” Her father had his own wireless that he listened to in his study but from 1936 there was also an RDS box “downstairs in the compound.” Ademola’s relationship with the two technologies was totally different. Wireless listening was rare and by invitation only of her father but the RDS was a “unifying factor” for all the compound. If she heard a shout of “Eh, it’s news time, let’s go and hear” or “it’s this choir, let’s go and hear,” she would run downstairs to listen to the box in the courtyard and “maybe there would be a bit of dancing around it.”Footnote 86

Gender, Advertising, and Voice

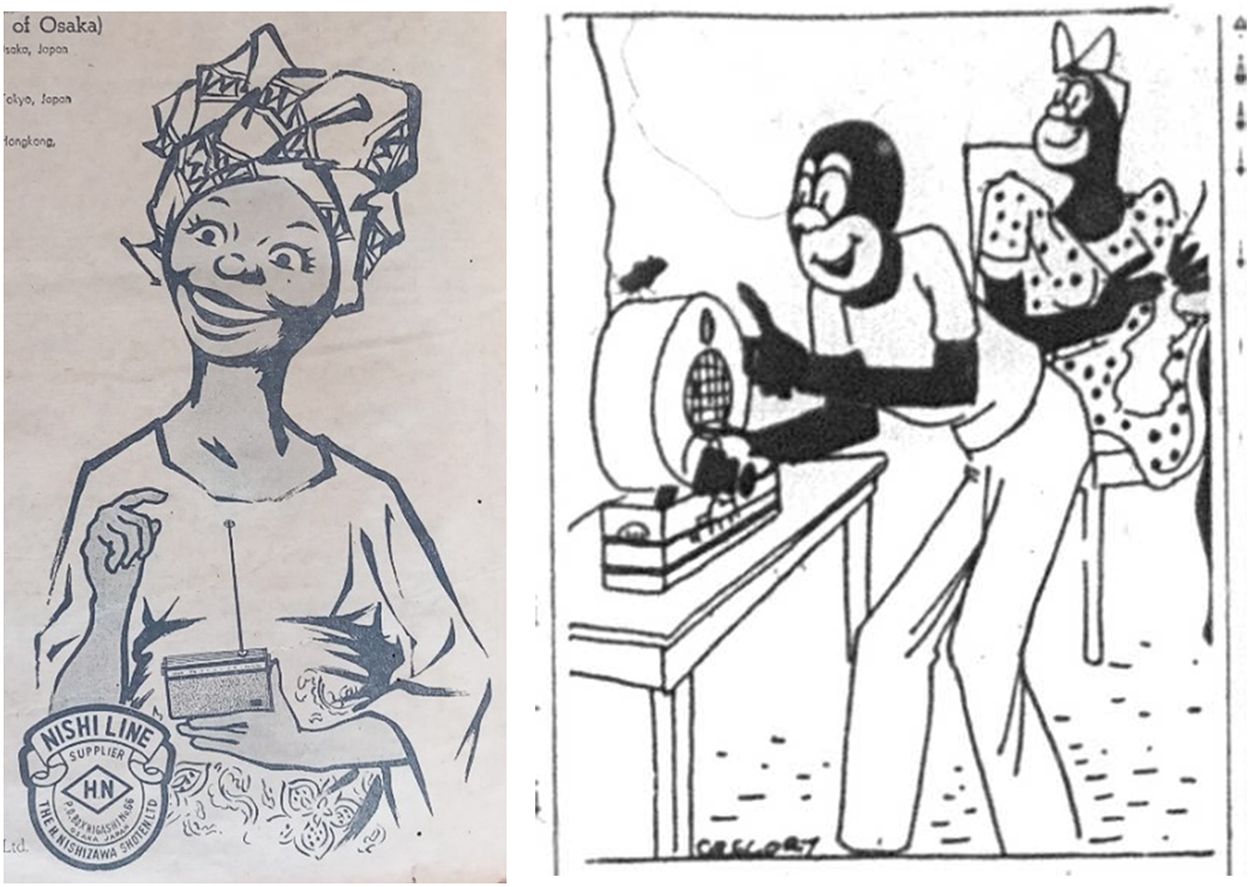

Advertisements for radio sets and the voice of broadcasts also reveal traces of the gendered nature of audiences which, in turn, they served to reinforce. While advertisements for radios in Ghanaian newspapers targeted both women and men from the 1950s, Zambian advertisements ignored female consumers until the 1970s. Figure 6, below, contrasts two typical promotional images of sets from Ghana and Zambia in 1959/1960. RDS boxes had such popularity that they were not advertised so the Ghanaian advertisement for a Japanese transistor is taken to be representative of Ghanaian listening culture at the time. Aside from the racist stylisation of the Saucepan cartoon, which I have discussed elsewhere, the main difference between the images is that the Zambian woman is presented as a passive listener while her Ghanaian counterpart is shown operating a radio set that she has bought herself. These images typified advertising for radios in the two countries. Women were regularly shown listening on their own in Ghanian newspapers from the late 1950s but in Zambia they were either depicted listening in the company of men or, more commonly, not at all until the early 1970s.Footnote 87

Figure 6. Visual framing of listenership. Left: Detail from “Specialist for West African Trade!,” Daily Graphic, 26 May 1960, 30; Right: Cartoon promoting the “Saucepan Special” in “Nkhani zamu Wailesi za December” (radio listings), Nkhani za Kum’mawa, Northern Rhodesia Information Department, Dec. 1959, 11.

The gendered nature of audience was also reflected in the sound of radio in Ghana and Zambia in the 1950s and beyond. Admittedly, the content of programmes in both countries was male-dominated as women rarely featured in the news and almost never in sports coverage, while soaps, dramas, and popular music lyrics typically portrayed women as girlfriends, wives, or mothers, often shown in a critical light, and sometimes they were openly misogynistic.Footnote 88 In the early 1950s both services launched regular women’s programmes that ostensibly sought to empower women, but broadcasters who worked on the programmes remembered that they were dominated by features about homecraft and child-care.Footnote 89

However, the voice of radio was markedly different in the two countries. In Zambia female broadcasters were few in number and had second-class status during the colonial period and beyond. After independence women continued to be absent from the flagship English-language General Service and they remained a minority on the less-prestigious vernacular Home Service. In 1975, for instance, the Home Service could still only number five women on its team of announcers, compared to ten men.Footnote 90 In the 1950s Agnes Morton was a prominent exception as the host of the popular music requests programme “Zimene Mwatifunsa,” and other female voices could be heard on women’s programmes and in dramas, such as the soap opera “Malikopo” which ran from 1947.Footnote 91 Otherwise the voice of Zambian broadcasting remained overwhelmingly male until the 1970s when Emelda Yumbe became the first woman to read the news.Footnote 92 All of the women that I interviewed in Zambia remembered their frustration with the dominant presence of male voices into the 1990s and a sense that female listeners were generally ignored. As Monde Sifuniso put it, “there was a time for women, a time for children but the rest of the time was for men.”Footnote 93

In Ghana the voice of radio was more feminine and the female listeners that I interviewed did not remember the alienation that my Zambian participants experienced. Women were regular presenters and producers of current affairs programmes from the early 1950s, such as Sunday Magazine which was presented by Frances Ademola from 1954. Betty Quashie-Idun read the English news from 1956, two decades before Yumbe was granted the privilege in Zambia, and Ademola recalled that nearly half of her colleagues at GCBS were female when she joined in the mid-1950s.Footnote 94 Ghana radio had also been directing broadcasts to an explicitly female audience long before Zambian radio, including public health talks from 1936, Hodson’s speech of 1937 quoted in the introduction, and, at the time of the Accra riots of 1948, a lengthy appeal to women for their loyalty from Comfort Peregrino-Aryee, the founder of a local women’s club.Footnote 95 Nkrumah’s appointment of Shirley Graham Du Bois and Genoveva Marais, respectively, as director of television and head of programmes at GBC in 1964 was extraordinary in global terms and reflected the status of female broadcasters in Ghana.Footnote 96

The difference in voice between Ghanaian and Zambian radio can be attributed, in part, to Ghana’s unusual history of colonial secondary and tertiary education for girls from elite coastal families at a time when it was practically unheard of in Zambia.Footnote 97 Frances Ademola, for instance, was the daughter of Ghana’s chief justice and was educated at the elite Achimota School and the University of Exeter in the 1940s. Before she was recruited to work for the GCBS she was employed by the BBC West Africa Service in London.Footnote 98 But the voice of Ghana radio was also shaped by technology as the RDS’ success in attracting such a broad listenership gave early radio managers an added incentive to recruit female presenters. By contrast, the Ghanaian press had a predominantly male readership and, as mentioned earlier, gave female writers few opportunities beyond women’s columns.Footnote 99

Conclusion

Colonial development schemes to promote affordable radio sets in Ghana and Zambia created mass African audiences a decade before the arrival of cheap transistor sets created comparable levels of listening in most other African countries. By popularising radio technology so early the schemes also had a long-term impact on audiences in Ghana and Zambia, which continued to be unusually large by continental standards for decades afterwards. The success of these radio projects therefore gives an alternative perspective on the history of development as they were small but significant exceptions to the general rule that state-led projects benefited few Africans in the colonial era.

However the social impact of the projects was uneven thanks to the seemingly-technical choice to promote wired or wireless sets. Audiences left few traces in the early days of mass broadcasting but by using fragments from a range of archives it is possible to reconstruct a gendered profile of early listenership. Audience research, oral histories, commercial advertising, and the voice of broadcasts reveal that the Saucepan became a manly machine and created a male-dominated audience in Zambia while in Ghana the RDS box was a homely object that was heard equally by men and women. This technological divergence reflected and reinforced a deeper history of gendered difference in the practice of colonial rule in Black colonies like Ghana and settler colonies like Zambia, where the exclusion of women from the public sphere had been pursued with greater vigour.

Colonial radio development schemes had their limits and their achievements were modest compared to the impact of the transistor from the 1960s. The affordability of this new technology made it easier for women to own or at least to hear a radio and from the mid-1960s the social profile of audiences across Africa was defined less by gender than by youth, education, and urban living.Footnote 100 Male and female audiences have been fairly equal in a numerical sense ever since but this study has demonstrated that quantitative audience surveys should not be allowed to obscure gendered inequalities in the experience of listeners. The frustrations felt by female listeners in Zambia lasted long after the colonial period and were probably shared by women across the continent where battery-operated wireless sets and male dominance of the airwaves remained the norm in the twentieth century, although more research is needed in this field.Footnote 101 The experience of Zambian women was symptomatic of a much broader social landscape of gendered inequality but I have argued here that the choices made by the colonial architects of Africa’s radio systems were not only reflective but also constitutive of that landscape. The comparison between Zambia and Ghana reveals that the association between radio and patriarchy was not inevitable and that the now-forgotten technology of wired wireless created an unusually large female audience in Ghana and a radio culture that was exceptionally egalitarian.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust and the John Fell Fund for funding my research in Ghana and Zambia. Archivists at the National Archives of Ghana and Zambia, the University of Zambia Library, and the BBC Written Archives Centre gave me invaluable help and guidance, as did Abibah Sumana, Elikem and Max Logan in Accra, Shimwaayi Muntemba in Lusaka, and Zaccheus Zulu in Kafue. I am also indebted to Audrey Gadzekpo, Victoria-Ellen Smith, the JAH editors, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on my research and earlier versions of this article. Most of all I would like to thank my interview participants for giving generously of their time and sharing their rich memories.