On 18 November 1934, policeman Kakpo was on guard duty at the dock of Gbécon, in the French colony of Dahomey (present-day Benin). Situated where the waters of the Mono river give birth to the Grand-Popo lagoon before emptying into the ocean, Gbécon was a strategic point for controlling trade between Dahomey and Togo. It was shortly after nine in the morning when Kakpo spotted a pirogue with six passengers carrying parcels of dried fish. He ordered the piroguier to show his licence, but upon inspection, he saw some bottles and a jerrycan of palm liquor. When he asked where the alcohol came from, four passengers tried to escape to another pirogue. The policeman and a colleague arrested three of them, while one escaped. Two were brothers Dossa and Messan, aged twenty-three and twenty-four, respectively, originally from Ouidah, and most of the alcohol in the pirogue belonged to the former. The third man arrested, forty-nine-year-old piroguier Egbenou, admitted ownership of the demijohn found on the boat. The jerrycan belonged to the fugitive, whose identity none of those questioned was able or willing to reveal. Ultimately, Dossa, Messan, and Egbenou were sentenced to six months in prison and fined 2,000 francs each.Footnote 1

Episodes like this were common in Dahomey in the 1930s, when the French colonial administration launched a campaign against the indigenous production of palm alcohol (sodabi). Policemen regularly stopped locals carrying suspicious parcels. The ban on sodabi continued until 1975, well after Dahomey’s independence on 1 August 1960. The repression of the 1930s was also not entirely new, as the French colonial administration and even the kings of Abomey in the mid-nineteenth century had already imposed restrictions on palm wine in the territory. The longevity of state repression of palm alcohol distinguishes Dahomey from other West African cases studied by historians, namely the British colonies of the Gold Coast (Ghana) and Nigeria.Footnote 2 Furthermore, the French colonial administration took much harsher measures than the British. By focusing on Dahomey, I aim to contribute to the history of alcohol in modern Africa, which has largely overlooked French West Africa.Footnote 3

The history of sodabi, which this article seeks to unravel, includes not only its repression, but also its production and consumption. Strikingly, little is known about how West Africans learnt to distil palm wine to make liquor. Only in relation to the Gold Coast, and based on the fact that Europeans were distilling alcohol there, has it been claimed that “it is likely that this knowledge may have existed in restricted circles, at least, by the early-nineteenth century,” although distilled palm wine is not mentioned in the archival documents until the 1930s.Footnote 4 In Dahomey, instead, this event can be dated with some precision. It was not until the interwar period that Dahomeans began to produce sodabi, thanks to a tool, the alembic, which they discovered in France during the First World War. The historiography on the African tirailleurs has focused on their racialisation, their treatment within the army, and especially the hysteria surrounding their contact with French women.Footnote 5 The battlefield, however, was also a site of technological appropriation by Dahomeans. If this transfer of technology once again followed the “usual” trajectory from North to South, it was unintentional. The history of the Dahomean alembic can therefore contribute to recent scholarship that seeks to problematise the presumed one-sidedness and linearity of the global history of technology.Footnote 6

In the 1930s, when the French shifted the burden of the Great Depression onto their colonial subjects by raising tax rates at a time when the selling price of agricultural produce was at its lowest, sodabi production spread. Dahomeans found palm alcohol to be more profitable than the oil and kernels demanded by European companies, and a cheap substitute for the European gins previously used in ceremonies. This article thus combines the top-down history of the repression of palm liquor with the “history from below” of its production. In doing so, it attempts to answer the twofold question of what drove the state to fight palm liquor and the peasants to distil it illegally. To explain the production side, it adopts a microhistorical perspective, examining specific archival sources such as colonial forestry reports and several hundred court cases. On the other hand, to explain the repression, its shifts and varying intensities, it broadens the perspective by going beyond the chronological limits of the formal empire.

The first section addresses the history of palm wine production, and how and why it was initially opposed by both the precolonial and the colonial states. The second section delves into the introduction of the alembic and the repression of sodabi in the 1930s. The following section specifically uses court documents as a lens to assess the social composition of Dahomean distillers, traders, and consumers of sodabi. The fourth section examines how the persecution shifted from distillation to palm felling after the Second World War, and how it survived formal independence.

From Palm Wine to Palm Liquor

The oil palm has been an integral part of the landscape of the southern region of present-day Benin since at least the seventeenth century.Footnote 7 The tree served a wide range of needs for the local population. In the Mono region, it is said that when an oil palm is cut down, all that is lost is the sound of it falling.Footnote 8 Almost nothing of the tree is discarded: the fruit shells, dried pulp, and palm fibres are used as firelighters; the leaves and the wood are used for building and fencing; the roots are remedies for rheumatism; the sap extracted from adult palms is fermented to make palm wine. In Dahomey, the sap is obtained by felling the palms, usually when they are between seven and forty years old. Depending on their size, oil palms can “bleed” between 0.5 and 2 litres of sap a day for up to 45 days.Footnote 9 Palm wine is a low-alcohol drink that goes to waste after a few days and is therefore mostly suitable for everyday consumption. For ceremonies such as marriages, funerals, and ancestor worship, however, Dahomeans preferred strong spirits imported from Europe as early as the nineteenth century.Footnote 10

The first restrictions on the consumption of palm wine date back to the kingdom of Abomey in 1843.Footnote 11 The reason for the ban was King Guèzo’s desire to preserve the most productive palms amid growing European demand for oil and kernels.Footnote 12 Guèzo’s reign (c. 1818–58) spanned the crucial decades of transition as the kingdom moved from slave to “legitimate” trade.Footnote 13 While he initially came to power with the decisive support of slave trader Francisco Félix da Souza, by the 1840s, slaves and palm products were contributing equally to his kingdom’s revenue, with the latter soon taking a clear lead.Footnote 14

King Glélé, Guézo’s successor, maintained similar restrictions. British explorer and diplomat Richard Burton, who found Dahomean palm wine “superior to the finest cider,” wrote in 1864 that Glélé banned palm cutting to “encourage the production of palm oil.” Only palms growing “in the bush,” which were difficult to harvest and likely to be smothered by the surrounding vegetation, could be cut for palm wine.Footnote 15 Although it is impossible to assess the extent to which these measures were enforced, they show that restrictions on palm wine were not an invention of French colonial rule.

France conquered Dahomey in the 1890s to prevent its oil palms falling into the hands of another colonial power.Footnote 16 However, knowledge of the local ecology was rather imprecise at the time, and the French interpreted the landscape of Bas-Dahomey as largely consisting of spontaneous palm forests.Footnote 17 Although subsequent research, most notably that of botanist Auguste Chevalier in 1910, showed that Dahomean palm groves were largely the result of intense human activity, French observers still felt that indigenous agricultural practices deserved more blame than credit.Footnote 18 On the one hand, they saw the palms as a sign of the former presence of a pristine forest that had been destroyed; on the other hand, they noted that unfavourable climatic conditions, in particular scarce rainfall, threatened the very survival of the palm groves. They thought that this process of gradual desiccation was caused by indigenous deforestation.Footnote 19 The belief that Dahomean peasants were responsible for poor agricultural practices was reinforced by a more general view of peasants as incapable of caring for natural resources, and a more specific racial view of Dahomeans as, in the words of French explorer Edouard Foà, “extremely lazy” and giving only “the most essential care” to the land.Footnote 20 The intertwining of these ecological and racial prejudices led colonial administrators to believe that the oil palm groves had to be protected.

The French therefore targeted the felling of adult palms for wine-making. This practice was particularly widespread in the Mono region. A 1903 annual report from the Grand-Popo district claimed that palm wine production had reached a level of expansion “excessively detrimental to the oil and kernel trade.”Footnote 21 Unlike in other parts of Dahomey, where palm trees were cut down when they grew too tall to harvest or when their yield began to decline, in Mono the palm trees were left fallow and planted very close together, sometimes with all the leaves cut off to make room for more trees. This was detrimental to fructification and therefore oil production, but the inhabitants of the region were mainly interested in the sap and therefore in making the trunks grow. As Mono was the least connected of the oil palm regions to the Dahomean ports, peasants could earn more from palm wine than from the palm oil trade.Footnote 22 Not surprisingly, one of the colony’s first administrators, Auguste Le Hérissé, placed the Adja people of Mono at the bottom of the racial hierarchy within Bas-Dahomey, accusing them of living “like savages” and “not working their fields and not knowing the fallow.”Footnote 23

On 23 August 1907, Governor Charles Marchal issued a decree prohibiting the felling of palms. Those found guilty were fined between five and fifty francs and sentenced to fifteen days’ imprisonment (by way of comparison, a kilogram of palm oil sold for 0.4 francs at the time); they were also ordered to plant four times the number of palms they had felled.Footnote 24 In 1909, “numerous” punishments were reported in the Athiémé district, leading to peasant protests demanding the repeal of the decree. In the end, the people of the district continued to cut down oil palms, often with the tacit approval of the chiefs who were supposed to supervise them.Footnote 25 Provisional Governor Raphaël Antonetti, after visiting the region in 1909, admitted that “if the indigenous did indeed cut down a lot of palms, they also planted a lot to be able to cut them down, because they seemed too aware of the value of their palm groves to destroy them thoughtlessly.”Footnote 26

Unlike in the Ivory Coast, where Governor Gabriel Angoulvant’s temperance campaign highlighted the health risks associated with palm wine, colonial officials in Dahomey dismissed the issue of widespread drunkenness.Footnote 27 “The Dahomean is not a drunkard,” wrote an agronomist in 1902, “and in spite of what has been claimed, written or said on the subject, I assert that this is a preconceived opinion which prevails in France, in general, but which is absolutely contrary to the truth.”Footnote 28 The first claims about Dahomeans’ drunkenness appeared in colonial reports just before the First World War, as a way of explaining Dahomean resistance to French control. In 1913, for example, Governor Charles Noufflard pointed out that alcoholism was “a constant danger” among the people of the Holli and Mono districts.Footnote 29 In 1917, Noufflard again blamed Mono’s tax collection and recruitment difficulties on “drunkenness” due to “excessive abuse of imported or locally produced alcoholic beverages (palm wine).”Footnote 30 However, according to Angoulvant himself, who had by then become governor general of French West Africa, it was Noufflard’s exaggerated “friendliness” towards the indigenous, rather than drinking in particular, that caused the French problems of authority in Dahomey.Footnote 31

During the First World War, a more careful understanding of local practices made the tapping of palm wine less threatening. In a 1918 text, Antony Houard, head of the colony’s agricultural service, downplayed the environmental impact of palm wine production. It “was not deforestation,” he wrote, because the Dahomeans planted “at least as much as they cut down,” and whenever possible they preferred to sacrifice the trees that produced less palm oil.Footnote 32 The same year, the general agricultural inspector of French West Africa, Yves Henry, criticised the ban on palm felling, calling it “irrational” and detrimental to achieving productive tree densities.Footnote 33 Throughout the 1920s, discussion of palm wine faded from colonial sources. Everything changed when the Dahomeans learnt to distil palm wine to make sodabi, but to understand its emergence we need to go back to the First World War.

The “Discovery” of the Alembic and the Repression of Sodabi

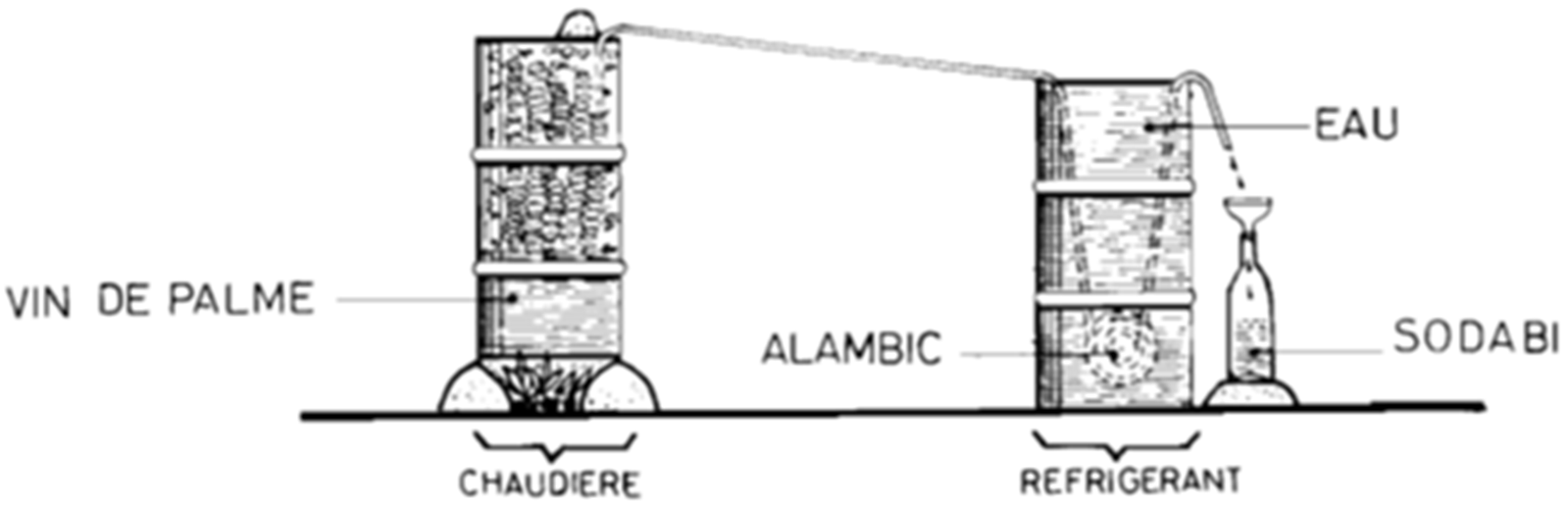

Sodabi was an unintended consequence of the First World War. The alembic, the new technology that made it possible to produce a palm drink with a high alcohol content, was introduced by some Dahomeans who had served in the French army during the conflict and had observed the French peasants distilling their own spirits. The most common equipment consisted of an empty barrel connected at the top to a copper pipe leading to a lower jar. The palm wine poured into the barrel was then brought to a boil, it evaporated and, after condensing in the pipe, was distilled drop by drop in the pot (Figure 1, below). It took about three hours to distil twenty litres of palm wine, and ten litres of palm wine were needed to produce one litre of sodabi.Footnote 34 Unlike palm wine, sodabi could be stored for a long time, which meant that it could be traded, and could replace the European spirits that Dahomeans used extensively in their ceremonies.Footnote 35 In short, this innovation was potentially very profitable.

Figure 1. The components of an alembic for the production of sodabi.

Bonou Kiti Sodabi, son of the village chief of Sèdjè Houégoudo, Sodabi Gbehlaton, is credited with bringing the first alembic to Dahomey from France. Initially, he made fermented alcohol from maize and bananas, and it was not until 1926 that his family began distilling palm alcohol.Footnote 36 However, the fact that his name appears for the first time in a Dahomean-produced newspaper, “Le Phare du Dahomey,” in 1937, while it does not appear in archival sources, suggests that Sodabi Gbehlaton was subsequently chosen as a local hero, whether fictional or real. The introduction of the alembic, instead, was a collective transformation for which even the colonial government could not find anyone directly responsible. During the First World War, Dahomey provided France with at least 12,300 men.Footnote 37 In France, African soldiers were systematically segregated from both French soldiers and civilians. The tirailleurs were rarely given leave, if at all, and then only for a few hours.Footnote 38 However, it was probably while working behind the lines, or during the so-called hivernage, the winter period when all West African soldiers were encamped near the Mediterranean, away from the cold battlefield further north, that the Dahomeans likely interacted with the local population, and came into contact with the distillation of eau-de-vie.

Since the beginning of the century, the colonial administration of Dahomey had distributed manual and mechanical crackers and presses aimed at increasing the rate of extraction of palm oil and kernels, but these did not significantly improve production because any advantage over the artisanal process was minimal at best.Footnote 39 Ultimately, the technology that first allowed peasants to increase their income from the oil palm was not introduced by European scientists or businessmen, but by Dahomeans themselves.

It is likely that the use of the alembic went unnoticed throughout the 1920s because distillation did not spread immediately. If the First World War brought the new technology to the Dahomeans, it was the economic contingency of the Great Depression that led to a boom in sodabi production.Footnote 40 Exportable West African products suffered from the fall in European demand and the selling price fell dramatically.Footnote 41 In the Allada market, for example, the selling price of palm oil fell by 91.25 percent between 1929 and 1933.Footnote 42 France reduced exit taxes to encourage exports, but left import taxes untouched, which kept the cost of consumer goods high. While incomes fell tragically, tax rates did not fall commensurately.Footnote 43 On the contrary, taxes on Africans peaked just when the export prices were at their lowest. Smallholders were increasingly unable to meet their tax obligations or feed their families. In some places, the annual head tax equalled the selling price of three tonnes of palm oil.Footnote 44 At the same time, to make up for the budget shortfall the French administration raised taxes on European spirits, of which Dahomey was by far the largest importer in French West Africa.Footnote 45 In the first six months of 1933, Dahomey imported less than a third of the European alcohol imported in the same period in 1932.Footnote 46

The increase in the real value of the head tax and the fall in the price of exportable palm products left many peasants with sodabi as the only production that allowed them to pay off the taxes. Sodabi also became an import substitution industry, allowing them to carry out their ceremonies without using European alcohol. Overall, France’s economic policies paved the way for the spread of sodabi. The practice of cutting palms for wine, previously confined to the Mono region, suddenly affected the whole of southern Dahomey.Footnote 47

Although sodabi allowed the Dahomeans to pay taxes, it ran counter to French colonial interests jeopardising the production of palm oil and kernels, on which the Marseille trading companies operating in the area depended for their very existence. As soon as the Great Depression hit the French credit system, these companies found themselves in difficulty, as their activities were based on advance loans, paid out in order to obtain as many tonnes as possible for the next harvest. One of the main companies, the Compagnie commerciale et industrielle de la Cote d’Afrique (CICA), saw its turnover halved and reported a loss of 5.6 million francs between 1930 and 1931.Footnote 48

In 1931, the colonial administration banned sodabi and promised a reward to anyone reporting violations. The ban included not only the cutting of palms, but also the possession of alembics and the production, storage, transport, and sale of palm liquor. Those found guilty were fined 2,000 francs and sentenced to three to six months’ imprisonment. Generally, people who only cut the palms were just fined.Footnote 49 However, fines were often unaffordable for peasants and were therefore usually replaced by additional imprisonment. In most cases, the police discovered the offenders because someone reported them, or by stopping them at checkpoints and finding them in possession of the forbidden spirit, which was then confiscated. On the rare occasions when they were found, the alembics were destroyed. Repression was mainly in the hands of the indigenous district guards (gardes de cercle) and, in the cities, the colonial police.Footnote 50

French repression of palm liquor was far stricter than that of the other colonial powers: neither the Belgians nor the British ever banned palm felling—apart from a few local by-laws passed by indigenous chiefs on the Gold Coast in the 1930s.Footnote 51 There were at least two reasons for this. The first was that palm wine production in Dahomey was already well developed by the beginning of the twentieth century, with regions such as Mono so specialised that most palm groves were devoted directly to the production of alcohol. The French expected the entire colony to contribute to the production of oil and kernels, and the fact that palm felling was the norm rather than the exception in these regions prompted the colonial administration to take decisive action. Second, the colony had no other commercial crops to flank or replace the oil palm. The British agricultural service of the Gold Coast could be less strict about palm cutting because the land cleared was soon taken over by cocoa plantations.Footnote 52 In contrast, Dahomey’s first development plan (plan de mise en valeur), approved in 1929, relied entirely on the oil palm, through the distribution of selected high-yielding palm trees and mechanical crackers and presses for extracting palm oil and kernels.Footnote 53 However, the motor presses proved no more efficient than the artisanal process. The motor crackers, although more appreciated by Dahomeans, were an expensive technology (costing at least 11,000 francs) that was only profitable for the few Dahomeans who owned large palm groves.Footnote 54 The planting of selected palms also had a paradoxical interaction with sodabi repression: the colonial administration that punished the Dahomeans for cutting down their palms for wine production in some cases forced them to cut down their palms in order to plant selected ones in favourable locations.Footnote 55

While the British decided in 1936 to condone the felling of oil palms for wine in the Gold Coast, the French considered an even more radical stance. In March 1937, the governor general of West Africa proposed that palm groves be turned into reserves, like protected forests.Footnote 56 Although this measure was ultimately not implemented, it shows that the French approached the palm liquor problem with a conservationist logic. In the written correspondence French officials often insisted on the environmental side effects of sodabi, writing about the palm groves around Porto-Novo as if an entire landscape had been lost. In 1936, the agricultural service reported that the felling of palm trees was taking on “worrying proportions,” and that the area between Affamé and Adjohon was in danger of “a total destruction of the palm groves.”Footnote 57 Consequently, the five-year plan for the period 1938–42 provided for the conservation of palm groves and the creation of a forestry service in Dahomey.Footnote 58

As has been argued, colonial conservationism was a means of social control.Footnote 59 Since the prohibition of palm wine in the first decade of the twentieth century, conservationist measures in Dahomey defined how oil palms could and could not be exploited. But if knowledge of the local ecology was very partial in the early twentieth century, and indeed the measures against palm wine were later criticised by French scientists, this was no longer the case in the 1930s. It is telling that French officials insisted on blaming sodabi for the destruction of the palm groves, even though one of the most respected colonial botanists of the time, André Aubréville, wrote in 1937 that the area of palm groves in Dahomey had actually increased during the 1930s.Footnote 60 Aubréville had pioneered the idea of forest recession and savannisation under African management, arguing that the West African climate was in the process of gradual desiccation. Nevertheless, he did not blame sodabi for environmental degradation. The proliferation of environmental concerns in colonial correspondence shows that administrators trusted their racial prejudices more than the experts they respected most. It was easier to see sodabi production as one of the “primitive” and “wasteful” indigenous agricultural practices, rather than as an alternative way of exploiting oil palms. This alternative practice involved planting new oil palms for every palm felled, combining them with food crops during the first few years, then dedicating them to palm oil production, and finally cutting them down for wine, to start the cycle all over again.Footnote 61 Although it is possible that some peasants did not plant palms after cutting them for sodabi, the tendency, acknowledged already by the most attentive contemporaries, was that Dahomeans planted more palms than before, precisely because of the possibility of obtaining more wealth from them thanks to sodabi.

Finally, it is striking how few temperance arguments can be found in the documents on sodabi, although temperance was increasingly discussed as a public health issue in French West Africa at the time.Footnote 62 In nearby Nigeria, the British administration openly propagandised about the allegedly harmful side effects of palm alcohol, while in the Gold Coast laboratory analysis claimed that palm alcohol contained dangerous levels of copper and zinc.Footnote 63 Nothing comparable happened in Dahomey: only an internal report in 1939 defined sodabi as “a true poison,” referring to its allegedly poor quality but without any evidence, and only once did a colonial official, the district commissioner of Porto-Novo, suggest that combating the “excessive consumption of sodabi” was crucial “for the protection of the race.”Footnote 64 It should be stressed that palm alcohol did not replace the weaker palm wine, but the strong European spirits. Its introduction did not change the level of alcohol consumption of Dahomeans. Dahomeans’ preference for sodabi was mainly based on economic advantages, while its taste, described as being as neutral as vodka, was not considered different from the low-quality European gins previously imported.Footnote 65 As we shall see in the following section, sodabi was consumed at ceremonies that traditionally required drinks with a high alcohol content.

Everyday Consumption and Production of Sodabi in the 1930s

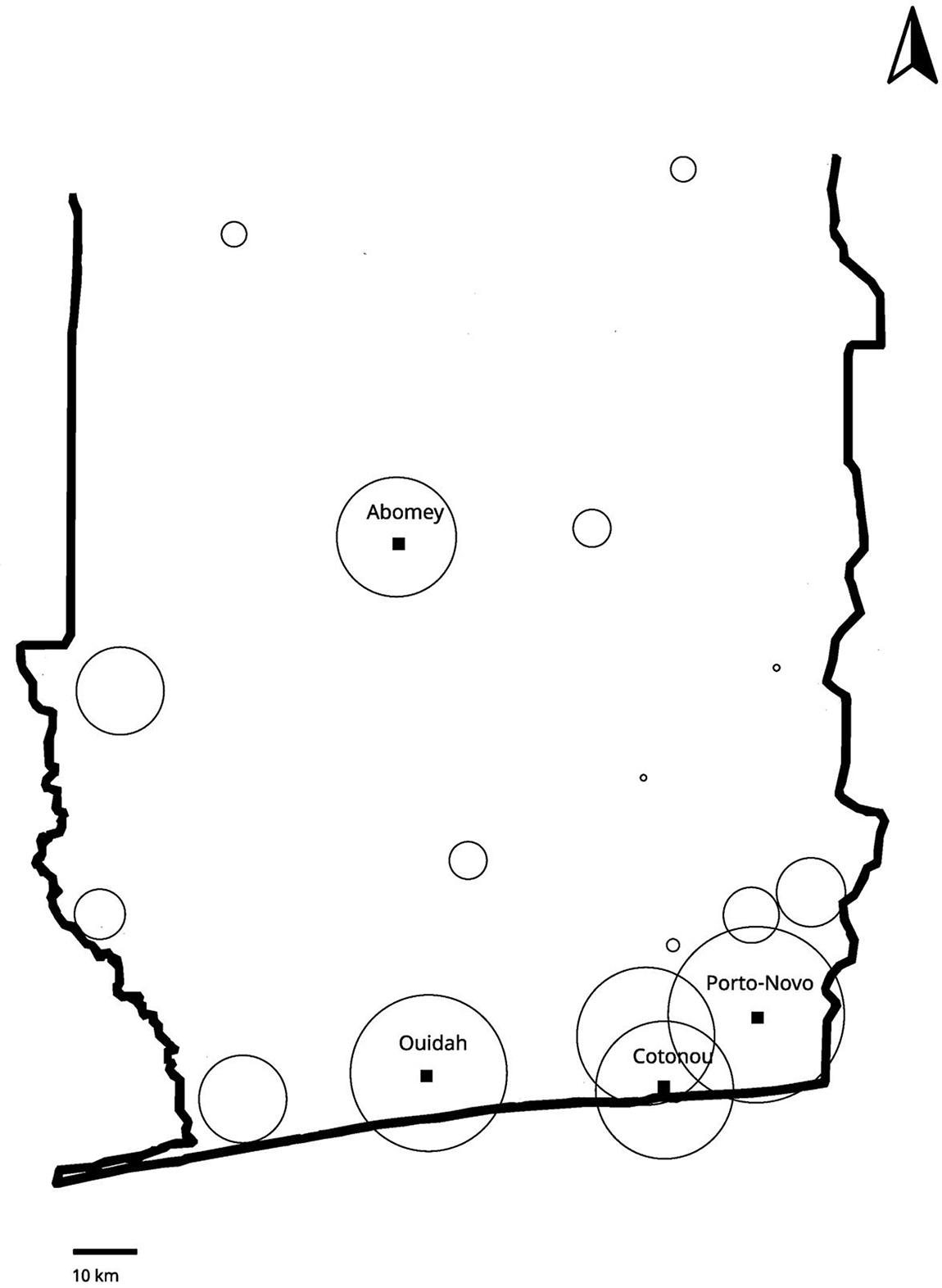

The court files held at the National Archives of Benin contain a wide range of trials, fines, minutes, and interrogations relating to sodabi cases from the 1930s to the end of colonial rule. The most consistent, albeit incomplete, records are the judgments of the colonial tribunals from 1933 to 1939. These include 201 cases involving 360 people, providing a sample to assess the diffusion of sodabi production and the division of labour within society. First, they show that already in the 1930s sodabi was produced throughout the entire oil palm region of Dahomey, in the southern departments and in part of the central departments of the colony (Fig. 2, below). Further consideration of the spread of sodabi is limited by the incompleteness of the sample and the possibility that stricter colonial controls led to higher crime rates in large towns. Moreover, the police relied on informers, suggesting that in areas where sodabi was widely produced, it might be less likely to be reported.

Figure 2. Map showing the distribution of sodabi-related crimes, based on court records for the period 1933–39.

Second, the professions of those prosecuted reflect the composition of Dahomean society, with a large majority of male peasants and female traders. As all classes of society were involved, indigenous chiefs and the French-educated African elite can also be found in the lists. This contrasts with the Gold Coast, where the African elite supported the colonial policy against palm felling.Footnote 66 In Dahomey, on the other hand, the French struggled to prevent alcohol production, not only because of a lack of personnel (the first forest guards, whose task was to monitor palm felling, were recruited in 1939), but also because of the complicit silence of indigenous chiefs, who were often the first to break the ban. The role of chiefs as a crucial cog in the colonial administrative machine in French West Africa broke down regarding sodabi. In 1940, for example, Dahomean agricultural inspector Kounasso tried in vain to obtain information about the crimes committed in the Adjohon subdivision, because the village chiefs covered them up.Footnote 67 The administration knew that Epiphane Agbo, the former canton chief of Ségbohoué, had “industrialised” the production of alcohol in the region, but despite repeated searches, the place of production could not be found.Footnote 68

Third, these documents show that palm liquor was not exclusively a male business: within the sample, 17 percent of sodabi-related offenders were women.Footnote 69 There was a gender division of labour. Those who were prosecuted for palm cutting were almost exclusively men. This can be explained by the fact that land ownership was patrilineal and therefore the trees belonged to men. Also, the difficulty of the work made felling trees and harvesting palms a male occupation. Similarly, the distillers were mostly men: only 6 percent of those condemned for sodabi production were women. On the other hand, women made up 36 percent of offenders for selling, storing, and transporting sodabi, which is not very high considering that trade in Dahomey was largely in the hands of women. However, the actual number of women involved could have been higher, as the colonial police concentrated its efforts on men, seeing them as the main economic actors and more likely to commit crimes.

These statistics show how men took control of a new technology, the alembic, but they also illustrate how the gender division of labour soon became nuanced in Dahomey’s rural society, where women had no right to own land but enjoyed considerable economic autonomy thanks to their trading activities. In 1934, Ahouissanou and his wife Alougba, who was otherwise a manioc flour trader, were caught producing and selling sodabi in Comè (Mono region). Alougba’s interrogation reveals that only her husband used the alembic, while she was responsible for selling the alcohol in his absence.Footnote 70 But women also used the alembics: a hygiene inspection at the home of Adjai Baba and her thirteen-year-old daughter in Zinvié revealed a still, a coil, and four litres of fresh sodabi. Adjai Baba fled and her daughter was eventually acquitted because of her young age.Footnote 71 The most notable case was that of Ayato Kakpo, sentenced by the Abomey-Calavi tribunal in May 1939. The police found two alembics and several alembic parts in her house in Cadjèhoun. Kakpo was a forty-five-year-old trader who had been selling illicit alcohol in the region for at least eight months. The profits allowed her to hire a young man, twenty-four-year-old Oké Gnaha, to help her with the trade. She was sentenced to six months in prison and fined a hefty 8,000 francs.Footnote 72

The alembics were usually made by Dahomean blacksmiths. This was the case of blacksmith Antoine Fanou, sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and a fine of 50 francs for making and selling an alembic in Abomey-Calavi.Footnote 73 There is no evidence that the copper itself was taken illegally, as was the case in Nigeria in the 1930s, where the theft of car parts to build stills was widespread.Footnote 74 Ahouissanou bought copper pipes from a stranger in Allada for 12.50 francs and sold sodabi at four francs a litre.Footnote 75 Palm alcohol was generally sold for between four and five francs a litre, so the alembics were quite cheap for the service they provided.Footnote 76 Ahouissanou kept the alembic hidden under some old sacks in his house.Footnote 77 Dossa, the peasant arrested at the Gbecon post in the scene that opened this article, hid his alembic at home, and only assembled and used it at night behind his house.Footnote 78

Some traded sodabi to make money. Dossa and his brother sold it in Togo because they needed a way to pay taxes.Footnote 79 Trader Elisabeth Afansi bought sodabi on the banks of the Mono river for four francs a litre and sold it for five.Footnote 80 Others bought sodabi for their own use, and the court sources are also useful to shed light on the consumption side. The palm alcohol could make for a merry evening: carpenter Samuel Ayivi was caught with a litre of sodabi, which he intended to offer to his friends.Footnote 81 Generally, however, sodabi was used in ceremonies. Maize trader Omidounssin Yaoutcha bought four litres for a family ceremony.Footnote 82 Driver Sylvestre Louis Odo was caught in Porto-Novo with eleven litres of sodabi, which he had bought for his engagement celebration.Footnote 83 Peasant Amoussou Ahoungansi bought five bottles of sodabi to celebrate the birth of his grandchild, but was discovered by the police in Ouidah on the night of 28 August 1937.Footnote 84

Most sodabi was used in funerals and ceremonies to honour the dead. In today’s Benin, it is still a common practice to pour a little sodabi on the ground for the ancestors before drinking. In Ouidah, on the evening of 13 March 1937, a major operation led to the arrest of ten people—two male peasants, five female traders, and two housewives—who had bought sodabi for fetish ceremonies and funerals.Footnote 85 Goat trader Fagbemiro Alougbin was riding his bicycle in Ouidah with a package containing five bottles of sodabi intended for a commemoration when the police stopped him.Footnote 86 Peasant Gbénou Honvou was found with almost eight litres of sodabi he had bought for his wife’s funeral.Footnote 87 In May 1939, the police even interrupted a funeral ceremony in Golo-Tokpa (Abomey-Calavi) to find peasant Hounguèvou Zoungbé with five bottles, four of them freshly perfumed with sodabi and a fifth still half full.Footnote 88

Late Colonial and Postcolonial Repression of Palm Cutters

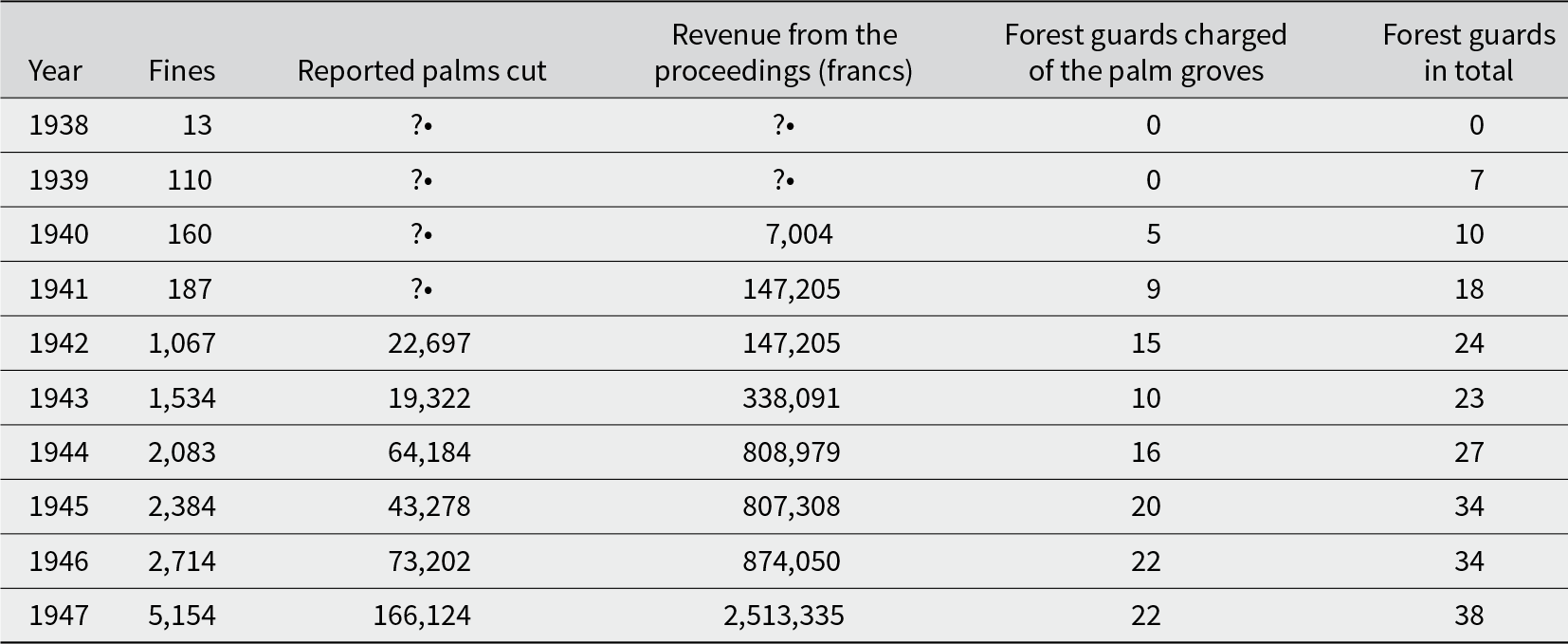

In Dahomey, as in other African colonies, the Second World War further restricted the supply of imported alcoholic beverages. In the absence of alternatives, sodabi was temporarily accepted even for weddings.Footnote 89 However, while the British legalised the private production of palm liquor in the Gold Coast in 1943, the French did not consider this option. On the contrary, after the war, they intensified repression and decided to tackle the problem of palm alcohol at its roots by focusing less on the production and storage of sodabi and more on the felling of palm trees (see Table 1, below). In July 1947, they staged a showdown by sending thirty-five gendarmes and forest rangers into the palm groves. This operation resulted in the discovery of more than 200 “criminal acts” in 5 days. However, the forestry service estimated that only 20 percent of illegal logging was prosecuted, with 500,000 palms cut down that year.Footnote 90 Despite the fines, sodabi production remained profitable, with peasants earning 1,000 CFA francs per palm tree, while risking a fine of 75–100 CFA francs per tree felled—and few fines were ultimately paid.Footnote 91 The fines were higher if one was caught in possession of distilled alcohol or of an alembic, but the low probability of being caught still made it worthwhile.

Table 1. Statistics from the Colonial Forestry Service in Dahomey on palm felling

Sources: ANB 3R2/8, Rapport annuel forestier, 1947; ANB, 3R2/12, Rapport pour l’année 1953.

In 1950, Governor Claude Valluy strengthened both the police and the forestry service.Footnote 92 A newspaper article entitled “Sodabi calamity number one of Dahomey” reported that in 1950 alone, a total of 400 years’ imprisonment was handed down for palm cutting.Footnote 93 The fines imposed on palm cutters are another useful source for assessing the validity of the administration’s environmental concerns. They record not only the number and age of palms felled, but also information about the surrounding palm groves. The minutes from 1953 clearly show that the peasants tried to sacrifice the old palms first and preserve the others whenever they still had older trees in their palm groves.Footnote 94 Overall, the French concern that the peasants would cut down the young palms for sodabi production was unfounded, as the palms produce almost no wine before the age of seven. Part of the reason for this misconception was that the palms for wine production looked younger than they were. The fact that they were densely planted prevented them from growing as much as the palms for oil production, which were usually planted nine metres apart for better fructification.Footnote 95

In 1953, the forestry service triumphantly announced a reduction in palm cutting. In reality, there were fewer fines only because there were fewer checks. Both the number of prosecutions for possession of alembics and the number of alembics confiscated by the police continued to rise throughout the 1950s, meaning that sodabi production did not decline.Footnote 96 It was the forestry service that began to turn a blind eye to cutting. The colonial judges, overwhelmed by the number of cases related to felling (of the 2,200 cases brought before the Court of Cotonou in 1952, 1,500 concerned palm felling), lobbied for a relaxation of controls. These demands found fertile ground within the forestry service, which had become increasingly unpopular in the colony due to the control of palm felling.Footnote 97 Another factor was economic. As the use of palm oil shifted from the soap industry to the margarine industry, refined industrial palm oil overtook artisanal hard oil.Footnote 98 This meant that from 1954, Dahomey exported only palm products processed in four oil mills built by the French in the early 1950s.Footnote 99 These were supplied by the palm groves in the immediate vicinity, where it was more convenient for the peasants not to produce wine but to sell the fruit either to the factories or to local producers. As was recognised at the time, palm cutting no longer affected exports.Footnote 100

The loosening of control was also due to the increased responsibility of Dahomeans in governing the colony. In 1957 the implementation of the Loi-cadre, aimed at weakening the anticolonial movements, transferred power from the French national assembly to the territorial assemblies of the colonies. It also gave them the right to decide on some matters that had previously been the prerogative of the French governor of the territory or the federal government in Dakar.Footnote 101 This reform allowed Dahomean politicians to have a say in internal affairs. In the debates of the territorial assembly, the representatives of the Mono region soon raised the issue of sodabi. Michel Noudehou, Athiémé deputy for the Parti Républicain Dahoméen, argued that the sanctions were “too rigid, if not arbitrary.” “The oil palms in Dahomey are what the vineyards are in France,” he added.Footnote 102 All these factors in favour of an increasing laissez-faire attitude towards sodabi production suggest that the anti-alcoholism movement in Dahomey, which culminated in the strike of alcohol consumption during the end-of-year festivities called for by the Conseil de la Jeunesse du Dahomey in 1952, was in fact quite limited.Footnote 103

However, while some deputies explicitly questioned the repression of sodabi, after independence (1960) Dahomean politicians kept the same concern for palm alcohol production as the French.Footnote 104 Dahomey inherited a deficit-ridden budget from the colonial administration, and any hope of reversing an unfavourable balance of payments depended on oil palm: as late as 1964, palm products accounted for 74 percent of the value of Dahomey’s exports.Footnote 105 Budgetary constraints and the hope that new factories could be built and the capacity of the old ones increased made the felling of palm trees an unforgivable waste. Accordingly, the postindependence policy on sodabi did not change. On the contrary, the first major development scheme of the 1960s, funded by the European Economic Community, involved the destruction of existing subspontaneous palm groves for wine production, and the creation of a new homogeneous plantation of selected oil palms for the sole purpose of producing palm oil.Footnote 106

From 1960 to 1975, sodabi distillation remained illegal. By this time, however, even the French experts advising the oil palm development projects began to reassess the production of palm alcohol. In 1968, French geographer Jacques Vallet, who had been commissioned to study the Grand-Hinvi area, where France and the World Bank wanted to establish an oil palm plantation, recommended legalising sodabi. He argued that “the felling of palms is undoubtedly not superior to the natural growth of the palm groves.” As for ethical and public health concerns, Vallet added that alcohol consumption in Dahomey could not be compared “even from a distance” with that in France.Footnote 107

In 1975, the same year that Dahomey was renamed Benin, the government of Mathieu Kérékou lifted the 1931 ban on sodabi. Peasants with a licence were now allowed to cut down palm trees. From the moment he came to power in October 1972, Kérékou showed, at least rhetorically, his determination to change Dahomey’s agricultural policy in order to protect peasants from being exploited by export companies.Footnote 108 The authorisation of sodabi production must therefore be seen as the formalisation of an increasingly permissive attitude on the part of the government towards alcohol production, that was intended to mark a break with colonial and the immediate postcolonial policies. Moreover, since Dahomey only exported palm products from the state plantations created in the 1960s, the economic reasons for banning the production of palm alcohol in private palm groves, which had been questionable since at least the 1950s, no longer applied. Ultimately, the fact that legalisation in Dahomey, unlike in Ghana, never became an “emotional political issue” perceived as a victory over colonial rule, suggests that the process was more gradual and that Kérékou’s measure ratified a factual situation.Footnote 109

In the following years, as Benin’s palm products gradually lost their share of the world market, sodabi became increasingly important. In some regions, where palm wine had previously been made only from palms too old to produce oil, peasants increasingly adopted the cultivation methods of the Mono region, felling trees earlier and systematically replanting them.Footnote 110 The 1990s saw a real shift in agronomic research. Until then, it had focused on crossbreeding to produce oil palms with the highest oil and kernel yields. Now, for the first time, the research was aimed at producing selected palms that would yield more alcohol than the subspontaneous palms by producing a sap with a higher sugar content.Footnote 111

Conclusion

Although palm alcohol repression in Dahomey peaked in the 1930s, its history was not a colonial parenthesis, but lasted from the precolonial to the postcolonial period, suggesting the need for more nuance in traditional chronologies of the French empire in Africa. Ultimately, repression continued as long as Dahomey/Benin was dependent on the export of palm products. Precolonial restrictions were introduced in the mid-nineteenth century, when European companies operating on the coast of Dahomey began buying palm products instead of slaves. In 1978, three years after Kérékou legalised sodabi, palm products represented only 11 percent of the value of Benin’s exports, seven times less than in 1964.Footnote 112

Moreover, while it is true that precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial states all chose to privilege the export of palm products, they did not pursue the repression of palm alcohol with the same intensity. The first colonial campaign against palm wine, which took place around 1909 mainly in the Mono region, was short-lived, probably because wine-tapping was confined to that region and the administration lacked the means to control it. Some observers also argued that Dahomean palm groves were expanding despite palm wine. If it is not surprising that the fight against sodabi reached its peak in the 1930s, when the Great Depression made it a priority of colonial rule, it is more striking that the late colonial administration, with its increased means and resources, instead relaxed repression by the early 1950s, due to the reluctance of both colonial judges and the forestry service to enforce bans.

The fact that the ban remained in place after independence, despite the lack of economic and environmental justification for it, testifies to the legacy of colonial rule. While French administrators from the 1930s to the early 1950s viewed sodabi as a threat to exports, the repression continued thereafter more out of habit than of any real sense of urgency. After independence, Dahomean politicians adopted the idea that such exploitation of the oil palm, which was not in line with rationalised, export-oriented agriculture, had to be banned.

The history of sodabi production, on the other hand, shows how the “sodabi calamity” was made possible first by the recruitment of Dahomeans for the First World War and then by French economic policy during the Great Depression. It was both price dynamics and France's deliberate decision to shift the burden of the Great Depression to its colonies that pushed the peasants into palm liquor production. Dahomeans, for their part, found in the alembic a kind of import substitution industry enabling them to celebrate their ceremonies without resorting to European spirits. Everyone in the palm region took part in the business, including the colonial administration’s most loyal collaborators, the indigenous chiefs. Moreover, a closer look at the fines suggests that the Dahomean peasants were not as ecologically careless as the administrators made them out to be.

Finally, if we consider the ban on palm cutting as a form of colonial conservationism, we should acknowledge that it was a particular one. While colonial conservationism was usually directed against long-established indigenous agricultural practices, such as swidden agriculture, the response to sodabi was triggered by a technological innovation: the alembic. Colonial officials did their best to make this new machine disappear from the colony. In the same years when they claimed to be developing the Dahomean oil palm groves, they opposed their economic development, if by that we mean maximising the extraction of value from the palms.

Acknowledgements

My warmest thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their precious remarks. Thank you also to Corentin Gruffat, Corinna R. Unger, and Élise Mazurié for reading and commenting on earlier versions of this work.