1. Prologue

For over 40 years, U.S. executive branch agencies have been required to conduct benefit-cost analyses to support major policy decisions under Executive Order 12866, “Regulatory Planning and Review” (Clinton, Reference Clinton1993), and its predecessors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), within the Executive Office of the President, plays a major role in developing best-practice guidance and reviewing these analyses. In 2023, OMB updated its guidance for the first time in many years, incorporating substantial changes. That update was then rescinded in January 2025. What follows is part of a Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis special issue that consolidates the comments from past Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis presidents and Journal editors on the draft of OMB’s regulatory analysis guidance, as well as their reflections on what has since transpired. I provide context for my comments on the draft revisions, replicate my comments verbatim, and discuss the results.

I drafted my comments late in the review process, so that I was able to consider what had been submitted previously. I found few discussed practical implementation. Although many, if not most, comments were brief and nonsubstantive, several knowledgeable experts provided thoughtful feedback that reflected familiarity with the underlying concepts and empirical research.Footnote 1 They rarely addressed the data, tools, and skills needed for successful application, however. The comments focused largely on the words on the page rather than on the work needed to implement them. To promote greater attention to this issue, my comments addressed the training and resources required to support high-quality analyses that are useful for decision-making, in addition to noting several substantive concerns.

The starting point for the comments was OMB’s issuance of a draft update of Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis (OMB, 2023a) in April 2023, along with a preamble describing the changes (OMB, 2023b) and a request for public comment. At the same time, OMB requested comment on an update of Circular A-94: Guidelines and Discount Rates for Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal Programs (OMB, 2023c). This was the first update of Circular A-4 since 2003 (OMB, 2003), and of Circular A-94 since 1992 (OMB, 1992), although in the latter case, the accompanying discount rates were frequently updated. As in the past, OMB requested comments on the revisions from Federal agency staff, from the general public, and from invited external peer reviewers. While this broad outreach ensured that feedback was received from numerous experts in diverse disciplines, reflecting many different perspectives, it meant that there were significant disagreements, which it was left to OMB to resolve.

Both Circulars continue the longstanding tradition of encouraging benefit-cost analysis of major Federal regulations (Circular A-4) and Federal investments (Circular A-94), although Circular A-4 receives substantially more attention. For example, 4,492 comments were received on the draft Circular A-4, while only 50 were received on the draft Circular A-94.Footnote 2 It is not entirely clear why this imbalance exists. It likely occurs at least in part because regulations impose direct costs on industries and other organizations, who often strongly contest the requirements, with pushback from those who benefit from the results. In contrast, the costs of direct Federal spending are less visible. The relationship between taxes and government debt and specific Federal investments is complex and not self-evident.

Similarly, this special issue focuses on the requirements for regulatory analysis in Circular A-4. However, a few others and I commented on both draft Circulars (Robinson, Reference Robinson2023a, Reference Robinsonb), often emphasizing the need to harmonize their provisions. The final 2023 version of Circular A-94 was similar to the final 2023 version of Circular A-4 and frequently referenced it, suggesting that OMB agreed with this advice. Interestingly, as of this writing, the revised Circular A-94 has not been rescinded, despite its similarities to the 2023 Circular A-4 update which was withdrawn.

Shortly after the final Circulars were published, the White House released Advancing the Frontiers of Benefit Cost Analysis: Federal Priorities and Directions for Future Research (NSTC, 2023). That report was authored by a subcommittee co-chaired by the Council of Economic Advisors, the OMB Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, and the Office of Science and Technology Policy, all within the Executive Office of the President. The subcommittee involved 80 members from throughout the government. The report addresses many longstanding challenges to the conduct of benefit-cost analysis, with the hope of spurring significant advances. An update of that report was issued in 2024 (NSTC, 2024). It discussed progress to date, identified additional areas of concern, and, perhaps most importantly, provided advice on conducting policy-relevant research. It is essential to recognize, however, that achieving the goals enumerated in these reports would require substantial investment of time and resources over several years, including increased funding to cover the involvement of both agency staff and external researchers. Survey clearance under the Paperwork Reduction Act also needs to be eased significantly. Good research takes time and resources.

2. Comments as submitted

Comments on U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-4 Modernization Updates, Docket OMB–2022–0014 (Robinson, Reference Robinson2023b )

Lisa A. Robinson, Center for Health Decision Science and Center for Risk Analysis, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/profile/lisa-robinson/)

June 20, 2023

The U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is revising Circular A-4, Regulatory Analysis, as part of its initiative to modernize regulatory review. That Circular was published in 2003. Since that time, there have been substantial advancements in theory and practice. Our understanding of the challenges associated with conducting high-quality analyses has also increased significantly.

OMB is to be applauded for undertaking this challenging and extensive update and for encouraging and incorporating substantial review by stakeholders. This is clearly an arduous undertaking that addresses many difficult and complicated issues. Ultimately, the results of this effort will improve both the conduct of regulatory analysis and the quality of regulatory decisions, enhancing societal welfare.

For context, I first summarize my qualifications. I then comment on cross-cutting issues and specific sections of the draft revision. Many of my comments relate to clarifying the text, providing additional practical guidance, and updating the discussion in some areas to reflect recent developments in the literature.

2.1. Qualifications

I have been involved in assessing policy impacts for over 40 years, as a government employee, a consultant to government agencies, and an academic researcher. I have led numerous assessments of the costs, benefits, and other impacts of environmental, health, and safety policies and regulations; addressed methods for benefit-cost analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis; and drafted guidance documents. As a result, I have substantial in-the-trenches experience in conducting and evaluating regulatory analyses as well as in developing guidance documents and reviewing their implementation.

For example, building on my work on conducting regulatory analysis for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), I co-authored guidelines on valuing the benefits of the 1996 amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act and contributed to its initial (2000) Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analysis. For a consortium of Federal agencies, I co-edited the Institute of Medicine (Reference Miller, Robinson and Lawrence2006) report, Valuing Health for Regulatory Cost-Effectiveness. More recently, I co-authored the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (2016) Guidelines for Regulatory Impact Analysis, as well as the 2019 Reference Case Guidelines for Benefit-Cost Analysis in Global Health and Development for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. I also developed approaches for valuing fatal and nonfatal risk reductions for EPA, HHS, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies and organizations.

I have taught many seminars, workshops, and courses on the conduct of benefit-cost analysis and have been a member of several expert advisory groups. Since its inception, I have been an active member of the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis, serving as President as well as on numerous committees. I have also been involved in the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis since its conception, as a member of its Editorial Board, peer reviewer, author, guest editor, and symposia organizer.

Links to many of my relevant recent publications are available here: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/profile/lisa-robinson.

2.2. General Comments

Several requirements currently contained in Circular A-4 (as well as in agency guidance documents) are often ignored. For example, as documented in OMB’s Annual Reports to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations, the analyses of many major regulations do not include reasonably complete estimates of benefits and costs, and in some cases do not include any quantitative estimates of benefits. Another example is the lack of distributional analysis, as documented in Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Hammitt and Zeckhauser2016) and elsewhere. The extent to which this lack of adherence reflects data, time, or resource constraints; disagreement with the requirements; concerns about potentially undermining the Administration’s preferred policies; lack of knowledge or understanding of best practices; the need for greater OMB enforcement; and/or other factors is unclear.

Below, I first offer some suggestions that are technically outside the scope of the revisions to Circular A-4, but seem essential to ensuring its appropriate implementation and improving the practice of regulatory analysis more generally. I also offer some suggestions related to the Circular itself.

(1) Support scholarly research and training: Full implementation of many of the Circular’s provisions will be challenging without substantially increased investment in scholarly research and training. At the moment, academic researchers face few incentives to conduct the types of applied best practices work that is needed to improve approaches to conducting regulatory analysis (see, for example, my later comments on stated preference research and distributional analysis). Providing Federal grant funds and supporting publication outlets for this type of research is crucial.

One of the most important sentences in both the revised and original Circular reads:

You will find that you cannot conduct a good regulatory analysis according to a formula. Conducting high-quality analysis requires competent professional judgment… (p. 3)

However, developing “competent professional judgment” requires substantial training and experience. In addition to understanding the Circular’s requirements and tailoring its application to the particular regulatory context, analysts face difficult choices about how to best use whatever data are available to inform decisions that must be made in the near term. Understanding options for using data that vary in quality and suitability, as well as understanding how to clearly communicate both the implications and uncertainties associated with its application, requires extensive hands-on practice and expert coaching.

Yet benefit-cost analysis is rarely taught as part of the undergraduate or graduate curriculum, and when covered, is often discussed in only a few sessions of more broadly focused courses. While professional development workshops are available, they are usually short and limited in scope. Encouraging increased training and experience in both educational settings and the workplace by whatever means possible is essential.

(2) Streamline and reorganize the discussion: While the draft Circular contains much important and useful information, it is very dense and repetitive, and it is often difficult to determine what it requires or recommends. What follows are some suggestions for streamlining and reorganizing the discussion.

-

a) Remove nonessential material: Either delete less essential material, move it to appendices, or suggest key documents for readers to reference for more information rather than including the information in the Circular.

-

b) Distinguish between requirements and supporting material: One option would be to follow a consistent format in each major section that highlights key requirements or recommendations (e.g. bolded or as bulleted or numbered lists), followed by discussion of (a) key concepts and theory, then (b) relevant empirical work.

-

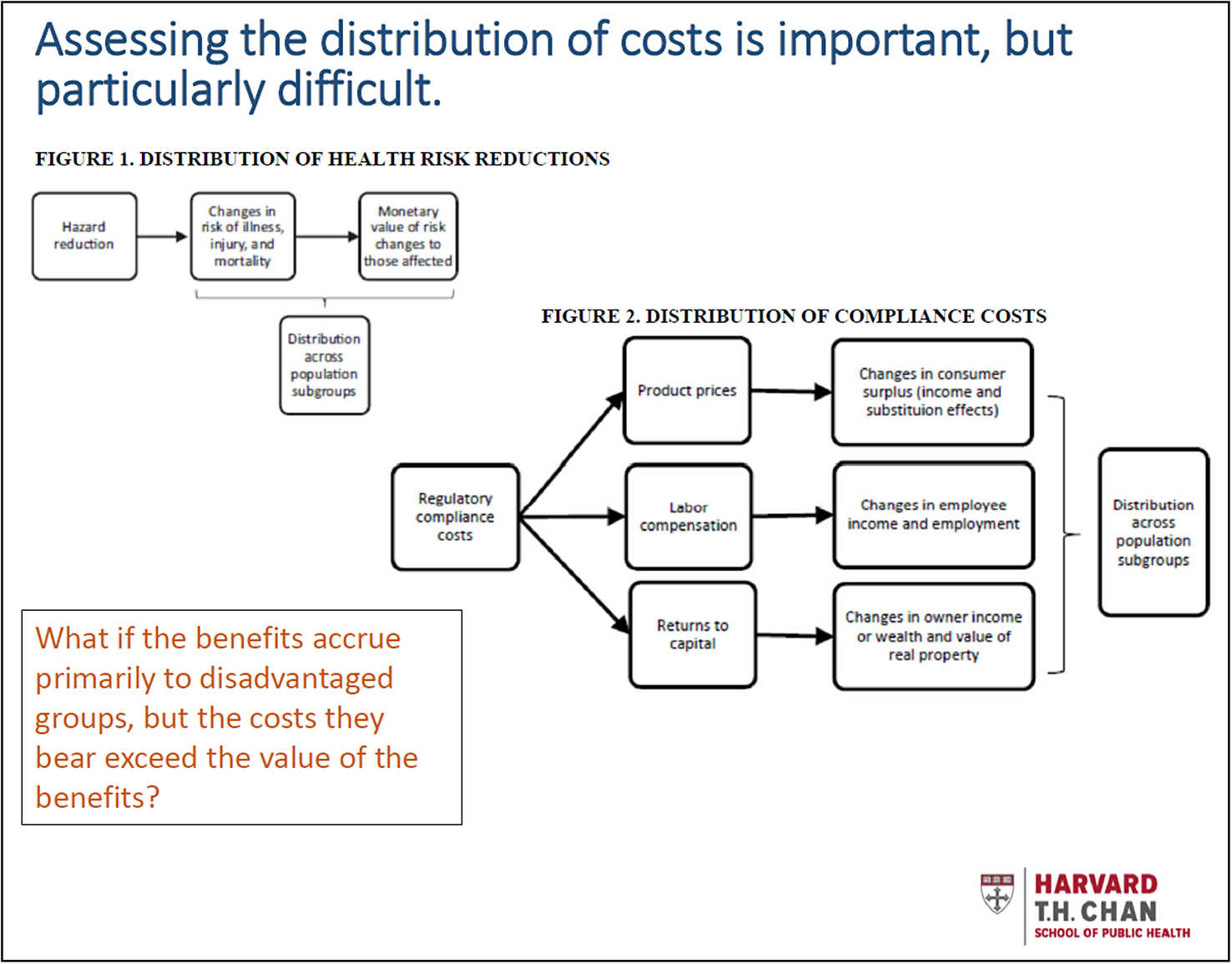

c) Begin with more explicit framing: Although the table of contents is very helpful, it would be useful to begin with an overview of the contents and a discussion of their interrelationships. For example, something along the lines of the Figure 1 graphic below (with supporting text), tailored to the Circular’s contents, would be valuable.Footnote 3

-

d) Include text boxes and formulas, but steer clear of specific examples: Including text boxes to highlight key points and formulas to illustrate key calculations would be very useful. For example, illustrating how present values are calculated and how an estimate of individual willingness to pay (WTP) is converted to a value per statistical life (VSL) estimate would be very informative. Specific examples from previous analyses may be less useful, since it is tempting to blindly follow the example rather than to think carefully about the extent to which it is relevant to the current context. Such examples may be more helpful as part of a training program, when there is more opportunity to discuss the usefulness of the example in different contexts.

-

e) Provide guidance and resources to improve communication with a general audience: Regulatory analyses are usually dense and complex technical documents that are difficult to understand and follow, even for those who have substantial experience in conducting these analyses. Analysts are often too familiar with the details of their work to easily identify areas where the presentation may be confusing. Providing guidance and training on clear communication, as well as templates for analysts to follow, and ample time to review the analysis before it is published, would be helpful. Involving technical editors may also be very useful. Improving the clarity of the written product seems particularly important given the Biden Administration’s commitment to encouraging more stakeholder engagement in regulatory development and review.

Figure 1. Benefit-Cost Analysis Components

(3) Create a central repository of completed analyses: It would be very valuable to develop a central repository of completed regulatory analyses. Such a repository would be helpful to those interested in learning about the basis for related policy decisions. More importantly, it would be an essential resource for those interested in assessing similar policies at the Federal, regional, state, or local level, as well as in other countries. Having the opportunity to build on previous work is far more efficient than starting from scratch, allowing time and resources that would otherwise be devoted to revisiting the same issues to instead be devoted to other (more welfare-enhancing) purposes.

2.3. Page-by-Page Comments

p. 3: Require scoping analysis: It is often tempting for analysts to just dive in, rather than first spending time thinking carefully about the approach and about how to best allocate limited time and resources. Beginning with a logic diagram or flowchart that links regulatory requirements to the full range of possible impacts is often useful. For more discussion of approaches to scoping and screening, see HHS (2016), Section 2.4, and Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Hammitt, Cecchini, Chalkidou, Claxton, Cropper, Hoang-Vu Eozenou, de Ferranti, Deolalikar, Guanais, Jamison, Kwon, Lauer, O’Keeffe, Walker, Whittington, Wilkinson, Wilson and Wong2019a), Section 2.2.

pp. 4–5: Require consistent categorization of impacts as costs or benefits: Footnote 4 As long as the sign is correct (positive or negative), the categorization of an impact as a cost or a benefit will not affect the estimate of net benefits. However, analysts, decision-makers, and other stakeholders are often interested in comparing total costs and total benefits across regulatory options or across regulations. In this case, consistent categorization is essential for comparability.

One intuitively appealing option is to distinguish between inputs and outputs. Under this scheme, costs are the required inputs or investments needed to implement and operate the regulation – including real resource expenditures such as labor and materials, regardless of whether these are incurred by government, private, or nonprofit organizations, or individuals. Benefits are then the outputs or outcomes of the policy, i.e. changes in welfare such as reduced risk of death, illness, or injury.

Under this framework, counterbalancing effects should be assigned to the same category as the impact they offset. For example, costs might include expenditures on improved technology as well as any cost-savings that result from its use; benefits might include the reduction in disease incidence as well as any offsetting risks, such as adverse reactions to medications or substitution of less healthy foods for those subject to the regulation.

pp. 5–8, 34, 48–49: Update and clarify discussion of cost-effectiveness analysis and QALYs. These sections are outdated and do not reflect recent guidance and research. The Gold et al. (Reference Gold, Siegel, Russell and Weinstein1996) guidance has been replaced with Neumann et al. (Reference Neumann, Sanders, Russell, Siegel and Ganiats2016); guidance developed explicitly for regulatory analysis in response to a request from OMB and a consortium of agencies (IOM Reference Miller, Robinson and Lawrence2006) also should be incorporated. A more recent discussion of the consistency of QALYs with utility theory is provided in Hammitt (Reference Hammitt2017). For a more up-to-date discussion of QALYs and their relationship to valuing health effects in regulatory analysis, see Chapter 3 and Appendix C of HHS (2016). Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Eber and Hammitt2022) provide an example of the challenges associated with applying these methods in regulatory analysis.

pp. 11–15: Distinguish impacts directly influenced by the regulatory decision from impacts influenced by Congressional or other action. Including impacts driven by early compliance with expected regulatory decisions or by statutory requirements could lead to misleading conclusions about the impacts of a regulatory agency’s decision. Given that the primary goal of the analysis is to inform that decision, disaggregation seems necessary. Assessing the impacts of anticipatory compliance and of preceding Congressional action provides important information on policy impacts, but is not as easily addressed through immediate agency action.

pp. 12–14, 23–24, 53–55: Consider the influence of regulatory design on compliance. The discussion of compliance and enforcement throughout the Circular could be significantly enriched by incorporating some of the material from Giles (Reference Giles2022) on how to design regulations to encourage compliance.

p. 27: Discuss the use of research synthesis methods to combine results across studies. Given that each individual study and data source will have both advantages and limitations, it is often useful (and preferable) to combine results across studies or data sources using methods such as systematic review, meta-analysis, and expert elicitation. There are many references on these methods that provide information on best practices, several of which are summarized in Robinson and Hammitt (Reference Robinson and Hammitt2015a, Reference Robinson and Hammittb ).

pp. 28–29: Streamline discussion of WTP versus WTA, and provide more practical advice. The discussion of WTP vs. WTA is missing some recent, directly relevant references that highlight related challenges. These include Hammitt (Reference Hammitt2015), Knetsch (Reference Knetsch2015), and Viscusi (Reference Viscusi2015). However, it may be better to shorten this discussion to focus more on providing practical advice for analysts, and simply footnote these and other references for those who are interested in learning more. Analysts may find it useful, for example, to review Tunçel and Hammitt (Reference Tunçel and Hammitt2014), which provides information on the extent to which WTP/WTA disparities are likely to be found for different types of outcomes. References such as section 2.1 of Robinson and Hammitt (Reference Robinson and Hammitt2011) address the extent to which estimates of WTA are available for outcomes of potential concern and difficulties with its empirical estimation. More generally, given limitations in the empirical research, analysts may often need to rely on estimates of WTP regardless of whether WTA may be the more appropriate measure.

p. 34: Note that other-regarding preferences are not always altruistic. As discussed in Section 4 of Robinson and Hammitt (Reference Robinson and Hammitt2011), preferences for outcomes that accrue to others may not be altruistic; for example, preferences may reflect the desire to reward or punish others.

p. 34: Recognize that OMB clearance under the Paperwork Reduction Act is a major barrier to conducting new stated preference research to support regulatory analysis. Substantial new best practice stated preference research is needed to improve the valuation of many nonmarket benefits in regulatory analysis. However, academic researchers face few incentives to pursue such work, given that funders and scholarly journals, as well as academic promotion policies, typically favor innovative research rather than research that reflects accepted best practices. While the Federal government faces greater incentives to encourage researchers to pursue such work, grant funding is scarce, and work conducted by Federal employees and contractors must be cleared by OMB. Such clearance requires significant time and resources and is difficult to achieve. Without revisions to the clearance requirements and process, substantial contributions to this literature that support improved analysis of regulatory outcomes are likely to be rare.

p. 37: Clarify that the benefit transfer process is the same as the process that should be followed to estimate any parameter value. It is not clear why this process is described as applying only to benefit values; the same process applies to estimating almost any parameter. In each case, analysts must describe the parameter to be estimated, search the literature for potentially relevant research and data, evaluate the available studies and data sources for quality and applicability, select estimate(s) for application, and address uncertainty. On a more minor point, the HHS Guidelines for Regulatory Impact Analysis (2016) include a graphic on p. 13 that may be useful in describing this process.

pp. 40: Add guidance on estimating direct compliance costs. Estimates of compliance costs are needed as a starting point for partial or general equilibrium modeling, and at times are the only cost estimates included in the analysis. Discussion of how to best estimate these costs could be easily added to the Circular, based on texts such as Boardman et al. (Reference Boardman, Greenberg, Vining and Weimer2018) and the current EPA (2010) and HHS (2016) guidance.Footnote 5 Both HHS (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Robinson and Hammitt2017) and EPA (2020) have also developed guidance on valuing time, and HHS has developed guidance on estimating medical costs (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Rein and Hammitt2017).

pp. 44, 51: Clarify and update discussion of valuing risks to children. The discussion of valuing risks to children should be updated to reflect newer work. For review of related issues and recent research, see Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Raich, Hammitt and O’Keeffe2019b).

pp. 47–51. Update references on valuing health and longevity. While it seems sensible to defer making specific suggestions on valuing risks to health and longevity, given the complexity of the issues, the references in this section should be updated to reflect the results of recent expert panel deliberations and academic research. For example, the discussion of expert panel deliberations should reference the conclusions of more recent EPA Science Advisory Board panels (EPA, 2011, 2017). The discussion of the relationship between VSL and VSLY and adjustments for age differences, and of the extent to which it is feasible to adjust VSL for other differences in the populations and risks affected, should also be updated to reflect more recent work (see, e.g. Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Eber and Hammitt2021). In footnote 82, it would be useful to add a reference to HHS (2021), which provides more guidance (including an Excel workbook) on adjusting VSL for inflation and real income growth.

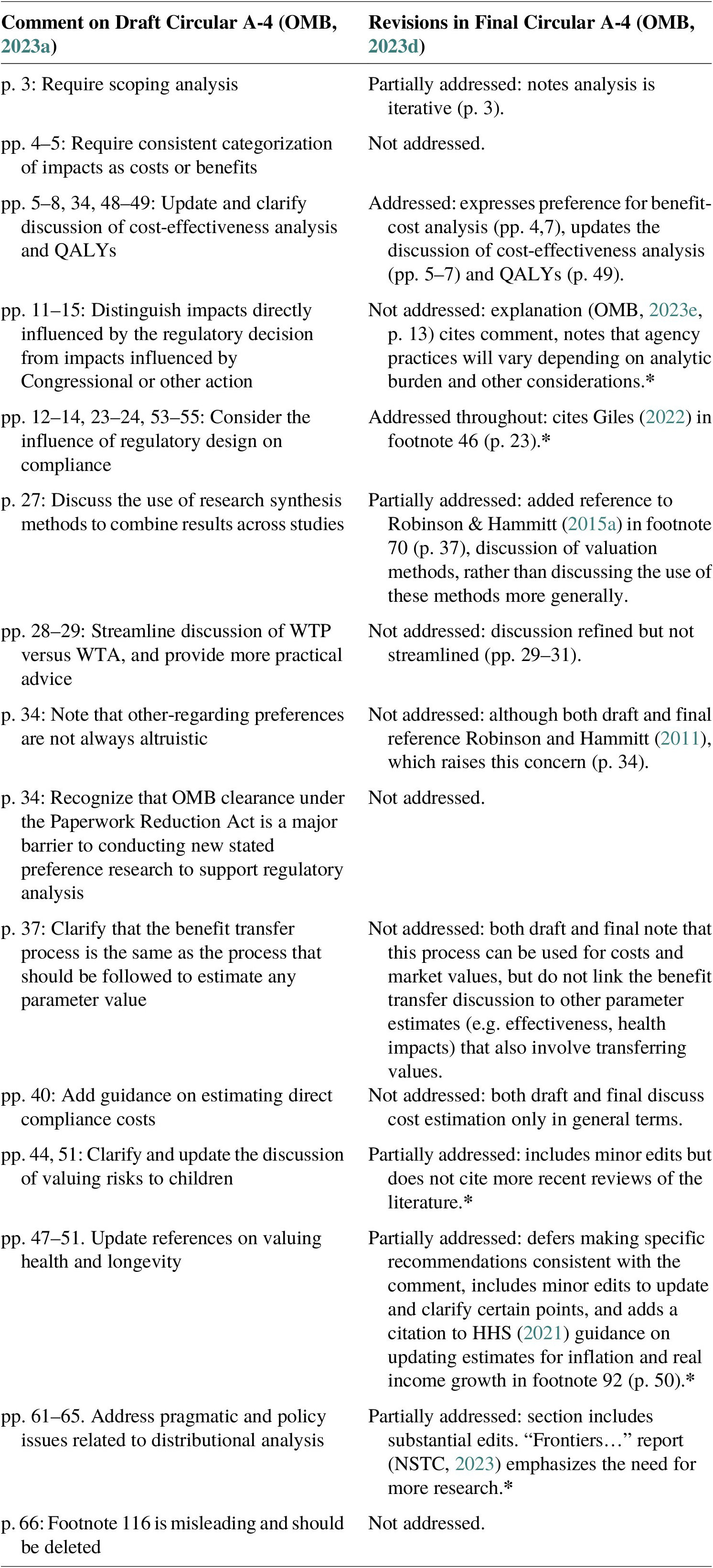

pp. 61–65. Address pragmatic and policy issues related to distributional analysis. Given the importance of distributional issues, the discussion of how to estimate the distribution of impacts is inadequate. The weighting proposed in the Circular is not possible unless analysts are first able to estimate how benefits and costs are distributed across those who are advantaged and disadvantaged. Related issues and general guidance are discussed in more detail in Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Hammitt and Zeckhauser2016) as well as in subsequent guidance documents (e.g. HHS, 2016; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Hammitt, Cecchini, Chalkidou, Claxton, Cropper, Hoang-Vu Eozenou, de Ferranti, Deolalikar, Guanais, Jamison, Kwon, Lauer, O’Keeffe, Walker, Whittington, Wilkinson, Wilson and Wong2019a).

Most importantly, little is known about how costs initially imposed on industry are distributed across individuals in different income or other groups, yet this information is essential to estimating the extent to which net benefits aggravate or ameliorate existing inequities. Some researchers have investigated the distribution of aggregate costs across many regulations or assessed the general equilibrium effects of large individual regulations. Little is known, however, about the extent to which the costs of smaller regulations are passed on as price increases, wage decreases, or reduced returns to capital. The distributional effects of passing on costs via each pathway are also not well-understood.

These challenges are illustrated in the Figure 2 graphics, which are derived from the references provided previously.

In addition, an important barrier may be agency’s lack of ability to address any inequities they find when they conduct these analyses, given their existing statutory authority (see Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Hammitt and Zeckhauser2016 for more discussion). Explicit guidance on how to deal with this concern seems warranted.

Figure 2. Distributional Analysis

p. 66: Footnote 116 is misleading and should be deleted. The application of a population-average VSL should not be confused with equity weighting. First, it has no conceptual or empirical foundation, e.g. in the marginal utility of income or preferences for distribution. Second, from an individual’s perspective, the population-average overstates the WTP of poor individuals and understates the WTP of wealthy individuals, and hence is not a fair representation of their preferences for spending on small risk reductions rather than other things. Third, if the distribution of costs is not weighted consistently with the distribution of benefits, the ultimate results will be misleading.

3. Epilogue

OMB solicited comments widely, receiving comments that expressed diverse and at times conflicting views on many topics. Deciding which of these comments to address and how to address them required substantial judgment. Along with the final version of Circular A-4 (OMB, 2023e), OMB published a lengthy explanation of its responses to the comments (OMB, 2023f) that covered many but not all of the comments received. In my case, OMB implemented some suggestions and cited related research in explaining the changes.Footnote 6 It was perhaps not surprising that several of my proposed changes were not incorporated, due at least in part to the challenges associated with addressing them. I briefly summarize OMB’s responses to these comments, then conclude with some thoughts on the relationship between research and policy, as well as the implications of the rescission of the updated Circular.

3.1. Responses to general comments

As expected, the responses to my general comments were mixed. Many were outside the scope of the Circular, but seem essential to achieving its goals.

“Support scholarly research and training:” Although the 2023 revisions to Circular A-4 did not directly address this first comment, the subsequent “Frontiers…” reports (NSTC, 2023, 2024) were a major step towards encouraging more scholarly research. However, neither the Circular nor the Frontiers reports fully address the need for training. Regulatory analysis is challenging, which makes it fascinating to conduct, but these challenges also mean that substantial training from experienced practitioners is essential to promote best practices.

At the time these comments were submitted, the major federal regulatory agencies employed a relatively small cohort of experienced regulatory economists. How they will be affected by the staffing and budget cuts now being implemented under the Trump Administration is unclear. Regardless, training will become particularly important as the baby boom generation retires, less experienced employees take on more responsibilities, and new analysts enter the workforce. While the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis and others provide professional development opportunities, a substantial increase in the availability of in-depth training is crucial to promote high-quality, informative, and useful analyses.

“Streamline and reorganize the discussion:” It is perhaps not unexpected that OMB did not respond to this second comment. The changes I suggested would require extensive editing and additional work, and more rounds of review before the Circular could be finalized. However, such changes are worth considering in revisions of the Circular as well as agency guidance and other documents. Substantial research (e.g. Rogers & Lasky-Fink, Reference Rogers and Lasky-Fink2023) suggests that writing more concisely with a clear organizational structure promotes more effective communications and improves responses.Footnote 7

“Create a central repository of completed analyses:” Similarly, this third comment would require substantial work, although of a different type. It is also outside the scope of the Circular. While the upfront investment needed to create this repository would be significant, the long-term benefits would be substantial. Such a repository would increase the efficiency of future work. If carefully designed, it would also provide an easily accessible resource that decision-makers and stakeholders, as well as analysts, could consult for immediate information on potential policy impacts, rather than needing to wait for new analyses to be completed.

3.2. Responses to page-by-page comments

OMB responded to my 15 page-by-page comments to varying degrees, as summarized in Table 1 below. To avoid repetition, I do not repeat the rationale for these comments, but believe more attention to these issues is warranted in future work for the reasons noted in the previous section.

Table 1. Responses to Comments

Note: * indicates comments specifically referenced in OMB’s explanation of its responses to public input (OMB, 2023e).

3.3. Some closing thoughts

I am fortunate that my involvement in conducting benefit-cost analyses, drafting and reviewing guidance (e.g. HHS, 2016; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Hammitt, Cecchini, Chalkidou, Claxton, Cropper, Hoang-Vu Eozenou, de Ferranti, Deolalikar, Guanais, Jamison, Kwon, Lauer, O’Keeffe, Walker, Whittington, Wilkinson, Wilson and Wong2019a), and undertaking academic research have allowed me to explore most of the substantive topics addressed in both the 2003 and 2023 versions of Circular A-4 elsewhere; I do not address them here. However, two points related to the above discussion seem worthy of emphasis.

First, guidance is not enough. Regulatory analyses are complex and diverse, requiring substantial investigation of the specific context. We have little choice but to rely on the analysts themselves to explore the details – searching for available data, evaluating its quality and applicability, conducting the analysis, and communicating the results. Much happens behind the scenes, often under tight deadlines with limited staff, data, and models. Although the 2023 update of the Circular provided detailed guidance on many, if not all, analytic components, it did not and cannot possibly cover all of the issues that arise when implementing this guidance for a specific regulation.

Providing training and resources to aid less experienced analysts in developing competent professional judgment is essential. Any guidance is simply a starting point. It will be ignored if what it proposes is infeasible, not well-understood, or inconsistent with legal authorities or policy goals. Understanding how to work with limited data, so as to inform decisions without ignoring related uncertainties, is a vital component of the process and requires substantial education and experience.

Second, the development and review of the revised Circular provided many examples of the profound influence of academic research on policymaking. As illustrated by the subsequent “Frontiers…” reports (NSTC, 2023, 2024), a substantial increase in policy-relevant research is needed, however. Many have written about how academic researchers can influence policy (e.g. Oliver & Cairney, Reference Oliver and Cairney2019). Although often based on anecdotal evidence from an individual’s own experiences, these writings provide much sound advice. For this advice to be effective, academics need to be interested in pursuing more policy-relevant research and willing to undertake the steps needed to make that research visible and useful to policy analysts and decision-makers. Incorporating more incentives for influencing policy in the criteria for academic promotion and for publication in peer-reviewed journals, as well as in measures of academic achievement, would also be helpful.

Finally, the rescission of the 2023 revisions to Circular A-4 (Trump, Reference Trump2025) appears to mean that the 2003 version of the Circular is reinstated. Whether another revision will be undertaken in the near future is unknown, however, many commenters on the 2023 update noted that such a revision was long overdue. More generally, the requirements for regulatory benefit-cost analysis under Executive Order 12866 remain in force, and guidance on best practices continues to be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

I thank Susan Dudley for organizing and supporting this special issue and for her insightful comments, and Thomas Kniesner for encouraging publication. For numerous interesting and thoughtful discussions, I also thank Jennifer Baxter, Aaron Kearsley, Jeff Shrader, and many others, including participants in sessions at the Allied Social Science Associations, Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis, Society for Risk Analysis, and Southern Economic Association conferences, as well as the other contributors to this special issue.