1. Background

On April 6, 2023 the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) published proposed revisions to Circular A-4 “Regulatory Analysis.” The existing A-4 had served various Presidential administrations for 20 years, and revisions were proposed to update and modernize the regulatory guidance. Public comments were solicited. In addition, ICF International was contracted to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within OMB to facilitate the selection of peer reviewers and organize a peer review of proposed revisions. Their reviews are the focus of this synopsis. Reviewers were asked to comment on any aspect of the proposed guidance and the preamble. Further, peer reviewers were invited to comment on a number of “notable proposed updates” to Circular A-4. Those updates dealt with the following topics: (1) discount rate, (2) distributional analysis, (3) scope of analysis, including geographic scope, (4) development of analytical baselines, (5) unquantified impacts, and (6) uncertainty. The purpose of this synopsis is to identify major points and highlight degrees of consensus. My method is to select from each of the nine reviews, quotations on each of the six topics to reflect the gist of the comments on each topic. My reading is that the peer reviewers selected on behalf of OIRA mostly agree on key aspects of the discount rate, distributional analysis, and scope, but that their advice is counter to the updates OIRA adopted. The concern is concentrated on guidance for the primary (core or base) case analysis.

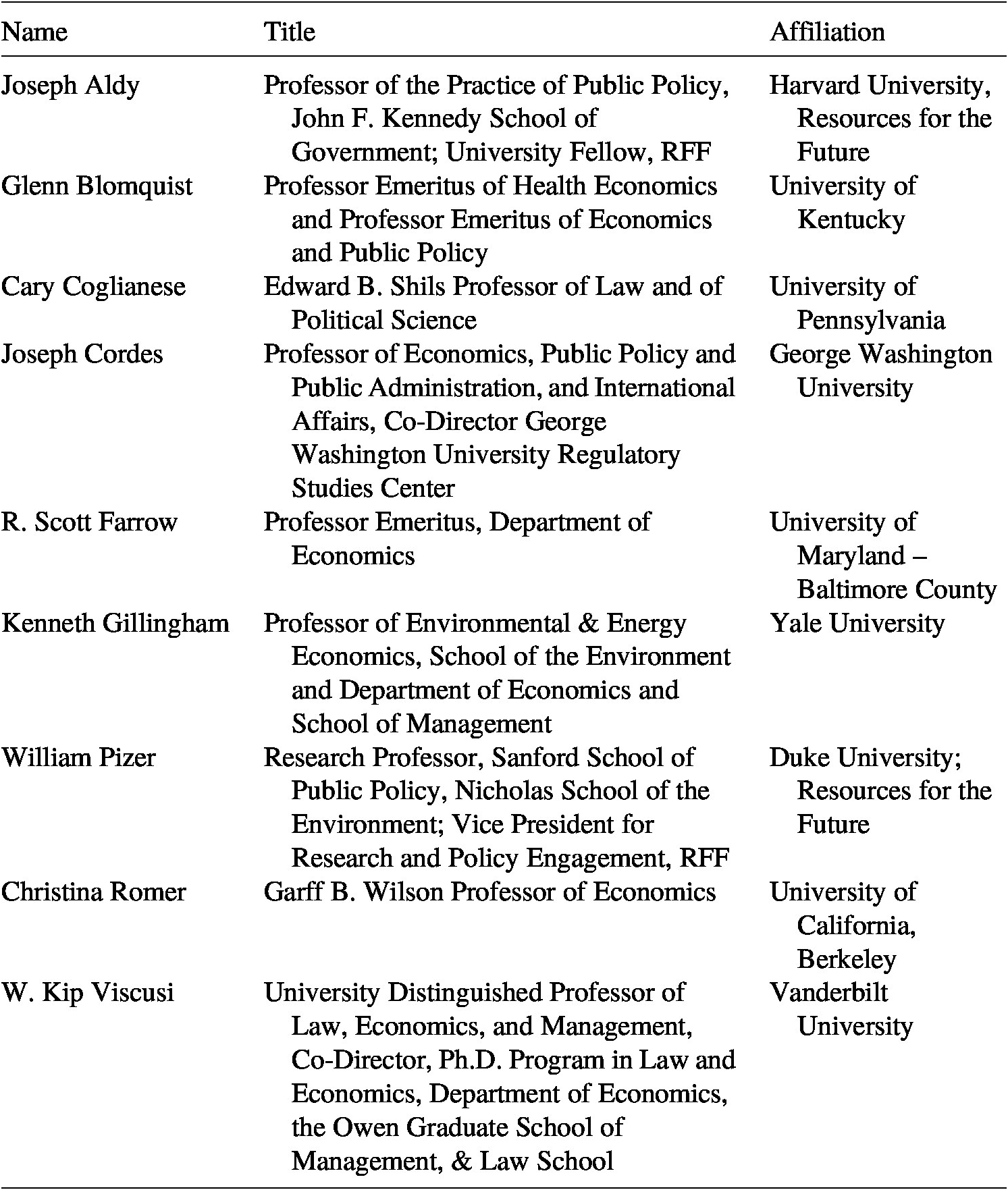

A call for nominations for peer reviewers was made and nine were selected. The announcement of reviewers appeared on The White House website on June 10, 2023, and is shown here as Table 1.

Table 1. Experts chosen for OMB circular A-4 peer review

ICF facilitated a virtual meeting on July 10th to share opinions and thoughts regarding the proposed changes. Developing a consensus was not the purpose of the meeting. Reviewers were asked to draft their comments independently but could draw upon public comments submitted through Reg.gov if desired. Reviews were due on July 24. On August 3, 2024 reviews were made available in a single document as Individual Peer Reviewer Comments on Proposed OMB Circular No. A-4, “Regulatory Analysis” at https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/A4-Peer-Reviewer-Comments_508c-Final.pdf.

2. Motivation and method

Reviewers were asked to draft their individual responses consistent with their experience and expertise and comment on any aspect of the proposed guidance and the preamble. Further, peer reviewers were invited to comment on a number of “notable proposed updates” to Circular A-4. Those updates dealt with the following topics: (1) discount rate, (2) distributional analysis, (3) scope of analysis, including geographic scope, (4) development of analytical baselines, (5) unquantified impacts, and (6) uncertainty.

After reading the comments from my fellow reviewers, I was impressed with the careful, thoughtful advice that was given to OMB and specifically OIRA. They addressed the wide variety of theoretical and practical issues inherent in regulatory analysis. I was also curious to seize the opportunity to glean insights this group might offer regarding the topics of the six notable proposed updates. It is the motivation for this synopsis. The purpose is to identify major points and highlight degrees of consensus.

My straightforward method is to select from each of the nine reviews, quotations on each of the six topics to reflect the gist of the comment on each topic. The selection reflects my attempt to honestly convey concise ideas that are more detailed and nuanced in the full reviews. I admit this endeavor has an element of mission impossible, especially in light of the fact that my review is one included for summary and comparison. My plea is for forgiveness if I have misunderstood or mispresented any of the comments. My thinking is to rely heavily on quotations so as to try to minimize the loss due to rewriting comments in my own words. Page numbers after the quoted selections below refer to pages in the collection of reports of the peer reviewers, Individual Peer Reviewer Comments on Proposed OMB Circular No. A-4, “Regulatory Analysis” referenced in the Background section above.

What follows is my synopsis of the gist of comments on each of the notable proposed updates for each reviewer. The order of the topics is the same as the order given in the charge to the reviewers, starting with the topic of the discount rate and finishing with uncertainty. The order of the reviewers is alphabetical, the same as in the collection of reports of the peer reviewers. A table that distills this review and offers my thoughts on consensus concludes.

3. Discount rate

Some issues regarding discount rates include the emphasis on a single rate to the exclusion of alternative rates for sensitivity analysis, the choice of precisely 1.7% with the appearance of certainty, the role of deliberate monetary policy on Treasury bond rates, the usefulness of the Ramsay model, and a declining discount rate for regulations with distant horizons. This list is not exhaustive.

Joseph Aldy: “revision down of the primary discount rate for RIAs is reasonable. I have some concerns about the use of one rate, as opposed to multiple rates to convey uncertainty in the appropriate discounting” (page 9).

Glenn Blomquist: “Especially given the emphasis on distributive effects in the proposed 2023 revision, care should be given to include persons facing rates much higher than 1.7%. Harberger and Jenkins judge that the social rate of discount that includes all members of society is well in excess of 2 or 3% in real terms … guidance should be given for at least one alternative rate for sensitivity analysis … the suggested default rate of discount should be at least twice the proposed 1.7%” (page 23).

Cary Coglianese: “resist the idea of recommending that agencies use just a single discount rate in regulatory analysis. The implication from having the 1.7 percent rate is the default rate would convey a false sense of precision and certainty about discounting … To maintain comparability with past regulatory analyses, a case could be made that OMB ought to continue to recommend agencies use a discount rate of 3 percent as among its recommended rates” (page 34).

Joe Cordes: “Something like a default discount rate of 3% with a lower value of 2% and an upper value of 4% or 5% may be more defensible (page 50) … precise level and ‘shape’ of the declining discount rate schedule is likely to be quite sensitive to specific assumptions made about the underlying distribution of ‘uncertain’ discount rates” (pages 50–51).

Scott Farrow: Based on his own analysis “the default recommendation for any length of project is 3% real, justified as expected value with uninformed prior of existing term structure bounds over relevant forecast periods. … Encourage sensitivity testing at such other discount rates as analysts can justify (page 61) … The choice of 10-year bonds has always been, in my mind, a convenient compromise. Its continued use in the face of dramatic interventions does not seem well supported in the literature.” (page 63).

Kenneth Gillingham: “I recommend retaining the structure of the proposed guidance, as it is well-grounded in the literature, and not going back to the old structure of 3% and 7%. I am not entirely comfortable with the false precision of 1.7%, and while I see reasons for the possibility of an even lower rate, there are more reasons for a slightly higher rate, including risk and low-income households not being part of the Treasury market. Thus, I recommend using a rate of 2% for the social discount rate (i.e., the consumption rate). Further, I support the use of an analysis based on the shadow price of capital to account for investment.” (page 72).

William Pizer: “use of 1.7 percent suggests a precision in the estimate that is unlikely to exist.” (page 82) … As a default, Circular A-4 discounting guidelines should instead adopt the proposed A-94 approach, which is a default premium of about 1 percent. Coupled with the above suggestion of a 2% risk-free rate, it suggests a default, risk-adjusted discount rate of 3 percent. (page 83) … there could be a default assumption about the discounting risk premium with sensitivity analysis reflecting higher and lower risk premia. Based on suggested rounding and the A-94 risk premium, this would be a central value of 3%, with a sensitivity of 2% and 4.5%. As alternatives, agencies could provide a more specific estimate of the risk premium for particular costs” (page 90).

Christina Romer: “number of reasons why the 1.7% rate may be somewhat too low. One that is mentioned in many of the public comments is that monetary policy has been highly expansionary for much of the past 15 years (page 96) … a real risk-free discount rate in the range of 2%–3% would be more accurate and in line with the academic literature than the proposed 1.7%. A further benefit of using a round number or a range is that it makes clear that the number used is not precise (page 97) … The most important suggestion is related to my concerns about the appropriate discount rate and the treatment of uncertainty and risk discussed above. It is essential that year-by-year values of the real monetized costs and benefits be reported so that it is easy for others to try alternative discount rates” (page 102).

W. Kip Viscusi: “1.7% reflects more fine-tuning than is warranted. For that rate, I would suggest 2% rather than 1.7%. … “advocate reporting of benefits and costs using multiple discount rates. I advocate 3% as an additional discount rate of interest” (page 105).

3.1. My reading

My reading of these reviewer comments suggests that consensus seems to emerge on several points. First, the guidance of 1.7% as the core discount rate reflects unfounded precision. Second, sensitivity analysis with alternative discount rates should be required regardless of the value offered as a core discount rate. Third, 1.7% is too low with only one reviewer hinting at a lower rate as an alternative. Fourth, a near consensus emerges that the guidance on a core discount rate, around which sensitivity analysis should be done, is likely about 3% in real terms.

My selection of quotes has focused on the core discount rate. The reviewers had much more in their reports than reflected in the brief quotes I chose. Kenneth Gillingham, William Pizer, and Christina Romer wrote extensive comments on discounting. Scott Farrow did a reanalysis of time varying bonds. The issue of declining discount rates over long periods is discussed in some reviews without a clear prevailing view. The shadow price of capital is discussed as conceptually appealing yet challenging to implement. These are sophisticated, rich reviews on issues in discounting. They are well worth reading.

4. Distributional analysis

Some issues regarding distributional analysis are allowing distributional weights for primary (core or base case) regulatory analysis, recommending weights of 1.4 based on estimates of marginal utility of income, loss of transparency regarding efficiency effects and distributional effects, changing the roles of analysts and policy decision makers, and incompatibility of using distributional weights along with a common, population average value of statistical life that can already give more weight to the disadvantaged,

Joseph Aldy: “The discussion of equity weights focuses on approaches that would increase the weight of low-income households’ willingness to pay for benefits (or the costs they would bear). This presumes that the status quo practice in agency RIAs assigns benefit measures for specific outcomes that vary with income. This is rarely the case in practice … By applying a common VSL across all populations affected by a regulation, regardless of differences in income or other factors that may influence willingness to pay to reduce mortality risk (such as age), agencies status quo practice reflects an implicit, equity-weighted approach to valuing benefits … an equity-weighted BCA risks appearing as a black box and does not convey information on whether a rule is expected to deliver more benefits than costs for the lowest income decile, for example, or delivers benefits in a progressive manner” (page 6).

Glenn Blomquist: “Estimating distributional effects of proposed regulations is demanding and can produce effects that differ in sign from those based on correlations. Estimating only distributional effects for benefits and failure to estimate distributional effects for costs can distort estimates of net benefits that make advantaged and disadvantaged groups worse off (page 16) … I recommend primary estimates of net benefits be based on market values and that any estimates based on distributional weights, such as weights using 1.4 as an estimate of the income elasticity of marginal utility, be offered as supplementary estimates. The first reason is that distributional analysis of net benefits is hard and likely to be estimated with less precision and confidence than overall net benefits. Mixing the distributional estimates with the overall estimates will reduce transparency and convey less useful information to the decision maker (page 18) … OMB should be sensitive to the possible types of roles that agency economists and analysts will be induced to play … By encouraging agency analysts to use distributional weights in the primary analysis of net benefits OMB is pushing them to rebalance their roles toward more team playing at the potential cost of scientific objectivity that allowed benefit–cost analysis of regulations to endure through agencies serving many administrations” (page 19).

Cary Coglianese: “encourage agencies at a minimum to seek to provide what might be called a “distributional specification” or “statement of the distribution of regulatory impacts … a descriptive account of what is known about the characteristics of the expected first-order recipients of regulatory benefits and first-order bearers of regulatory costs (page 36) … I am supportive of Circular A-4 signaling to agencies that weighting might sometimes be pursued as a supplement to conventional estimation techniques. I am concerned, however, with the unduly permissive way that this section is drafted and what that may mean for how it will be implemented (page 37) … The current version of the proposed update thus takes an overly optimistic posture toward the use of weighting in benefit–cost analysis” (page 38).

Joseph Cordes: “There are formidable conceptual and empirical challenges to identifying and estimating distributional effects. Simply determining who benefits and who bears the cost requires determining what public finance economists refer to as the economic incidence of regulatory benefits and regulatory costs. This may or may not correspond to what might be described as the initial impact of the regulation (page 51) … The preferable approach would be to incorporate distributional effects in a regulatory impact analysis in much the same way as distributional effects are presented separately from efficiency effects in the analysis of tax policy. Namely, show how the benefits and costs are distributed among the relevant groups in addition to and separately from presenting any estimates of the policy’s impact on economic efficiency. The inherently subjective weighting of these separate effects is best left to decision-makers and the political process. (page 52) … the case for cresting and using distributional weights, there is considerable disagreement, creating skepticism, among many economists about both the conceptual and the empirical basis for using such weights in benefit–cost analysis” (page 54).

Scott Farrow: “Continue the assumption for the base case that the elasticity of the marginal utility of income (ε) is zero for continuity and its implication for transfer rules. In other words, distributional weighting should NOT be a primary analysis (page 58) … Transfers only net to zero generally under ε =0. Transfers can have differential impacts under a different assumption for ε (page 58) … The distributional weight of 1.4 based on the elasticity of the marginal utility of income is not supported in the A-4 draft … the support in the preamble depends on a very extended footnote (footnote 27) discussing various estimates. This suggests to me that the value and use of the parameter is not yet standard (that is a lower bound of quality for which OIRA is providing guidance)” (page 58).

Kenneth Gillingham: “I strongly support this discussion of calculating the benefits and costs for different subpopulations and recommend very few changes to this discussion, if any (page 72) … I strongly recommend that equity-weighting is permitted as an option for regulatory analysis using the methodology in the proposed guidance, but that due to the relatively early stage of the literature that implements the concept, the equity-weighted analysis should not be the primary analysis, but rather could be presented accompanying a more standard analysis” (page 73).

William Pizer: “An emphasis on distributional weighting, and particularly the idea that it would be the primary estimate, is problematic (page 85) … While an expanded presentation of distributional analysis is warranted, it seems premature to emphasize the use of distributional weights and, especially, to suggest that such weighted CBA could be a primary analysis. For non-market goods, use of national valuation averages could address some of the equity issues that motivate weighting without the same concerns.” (page 91).

Christina Romer: “The proposed revisions encouraging distributional analysis also raise important issues for transparency. In cases where analysts present an income-weighted cost–benefit analysis, the guidance wisely asks for the unweighted (or, more appropriately, as the guidance points out, conventionally weighted) estimates. I think it is valuable to go even further in showing the steps of the analysis. In particular, agencies should report the costs and benefits by income (or other) group. This would enable others to see exactly what is being estimated or assumed about the distribution of costs and benefits before any estimates of the marginal utility of income are added to the analysis” (page 102).

W. Kip Viscusi: “In my view, this section should be substantially reworked, strengthening the guidance for providing distributional impact information, but with much of the discussion of weighting eliminated. In particular, I would eliminate the section --e. Weights and Benefit–Cost Analysis (page 105) … I propose that OIRA establish standardized income-based categories for reporting distributional effects so that the effects across agencies can be compared … The discussion of distributional weights ignores the substantial implicit redistribution that takes place by using average VSL levels and average unit benefit levels rather than population-specific values” (page 106).

4.1. My reading

My reading of these reviewer comments suggests that consensus emerges on several points.

First, if distributional effects are expected to be important for regulation, estimating net benefits to groups or subgroups is warranted regardless of any weights that an analyst might want to use to combine the efficiency and distributional impacts. They should be estimated and reported conventionally.

Second, all but one of the peer reviewers advise reporting conventionally estimated net benefits as the primary analysis. Christina Romer does not say it, but her review is nuanced. The reasons for standard benefit–cost analysis as primary include promoting transparency (no black box), protecting the quality of estimates of population averages compared with estimates for subgroups, avoiding the application of equity weights upon which no scientific consensus exists, steering clear of misleading, incorrect analysis given that population average VSLs are standard use, and preserving the role of weighting the distributional effects relative to efficiency effects to the policy decision-makers.

Third, a benefit of doing more rigorous distributional analysis will be learning how to estimate those effects better.

My selection of quotes has focused on equity weighting in the primary regulatory analysis. The reviewers had much more in their reports than reflected in the brief quotes I chose. Several wrote extensive comments on distributive analysis. William Pizer offered a detailed example of how equity weighting tends to dominate efficiency effects across income groups. These are sophisticated, rich reviews on the merits of distributive weights in the primary, core benefit–cost analysis. As with the sections on discounting, these on distributional analysis too are well worth reading.

5. Scope of analysis, including geographic scope

Some issues regarding the scope of analysis include policy standing as to who counts, how much value to those who are not US citizens and who do not reside in the US count in the US regulatory analysis, whose values should be used if those who are not US citizens and do not reside in the US are included, how much values to US citizens and residents depend on location of expected regulatory effects, the extent to which domestic and global regulatory effects can be estimated separately, and how much US citizens and residents value negotiation stances that might induce global cooperation.

Joseph Aldy: “In discussing when it is appropriate to include effects experienced by those residing abroad, it would be valuable to task agencies to: (a) explicitly reference the relevant effects that motivate this consideration; and (b) explicitly note how this information will be conveyed to other countries/relevant international institutions … explain how it would communicate the use of a broader-than-domestic measure to other countries and institutions to leverage action or demonstrate compliance” (page 8).

Glenn Blomquist: “the issue is mostly an issue of standing, i.e., whose benefits and costs count in the benefit–cost analysis. The proposed change is potentially prodigious if the agency determines that effects on citizens and residents and beyond the borders of the US cannot be separated from effects on “noncitizens residing abroad” in a practical and reasonably accurate manner. The implication is that all global effects should all be included in the primary analysis (page 20) … A preferred approach would be to have the focus of the primary analysis be on benefits and costs about which we know the most in terms of direct effects and on the value of them to US citizens and residents within the borders of the US. Regulations that reduce carbon emissions are a public good with global effects, but the value of the effects US citizens and residents depends on where risks of floods, fires, hurricanes, heat waves, and other consequences of climate change take place. Attempts to estimate how much more benefits are than the domestic value or how much less benefits are than the global value should be guided by the willingness to pay by US citizens and residents (page 20).

Cary Coglianese: “The 2003 update encouraged agencies to report separately the impacts of regulations falling beyond the borders. The proposed update largely does the same in directing agencies to provide “supplementary analysis” (pp. 9, 10) of impacts on noncitizens. This strikes me as exactly the right approach, entirely consistent with agencies’ obligation to provide more information, rather than less. By including, but separating out, the impacts on noncitizens, decision-makers and the public will learn more than if certain impacts went unanalyzed or were lumped in with aggregate estimates … such additional information should only be provided when it can be reliably estimated” (page 39).

Joseph Cordes: “If one accepts the premise that the relevant social benefits should be based on the willingness to pay for environmental improvement of US citizens, the question can be reframed as follows: (1) to what extent do US citizens have a positive willingness to pay for environmental benefits that accrue to citizens in other countries … This suggests that a conservative approach to incorporating global benefits and costs would be: (a) to include global benefits and costs separately, along with purely domestic benefits and costs … and (b) present a range of values for such global benefits, treating the full magnitude of global benefits and costs as “upper bound” estimates, and applying an appropriate discount to such values to represent the willingness to pay of American citizens” (page 52).

Scott Farrow: “All the dimensions follow from having to justify standing for a particular analysis (Farrow, Reference Farrow2023) but this guidance should provide the required minimum … If both domestic and international impacts are assessed, they should be presented both separately and together so as not to obscure results likely informative to decision-makers in an aggregate. In some ways, this is a distributional analysis, with the dimension being US or foreign as the distributional impact. … A particular regulation, say affecting climate change, might have a US legal basis (in treaties, which gives standing to others), or perhaps a US empathy basis (we are willing to pay to reduce not only our own impacts but others, Farrow, Reference Farrow2023 for VSL for “foreigners.”). I don’t find the existing “strategic interest” discussion very compelling unless an existing US legal justification exists although standing, as a policy determined issue, could be based on decision-maker interest” (page 64).

Kenneth Gillingham: “when the effects of the regulation have a global scope, the correct analysis considers this global scope. The logic in the National Academies report can extend to other regulations that have global ramifications (page 73) … strongly believe that requiring agencies to make a simple calculation for the domestic effects that ignores reciprocity, best responses, Americans overseas, and indirect effects has the potential to lead to a misleading calculation that does not actually capture the effects on the United States. Thus, I strongly recommend retaining the approach in the proposed guidance that allows agencies to present a global estimate when it can make a reasonable case that a purely domestic estimate is infeasible” (page 74).

William Pizer: “For this reason, any primary effects outside US borders should be measured based on the recipients’ willingness to pay (page 87) … I believe it would be clearer, and in keeping with intention, to indicate that the default focus is primary effects on US citizens and residents. (page 90) … The primary scope analysis could be global when such scope is motivated by one of several reasons. However, valuation of impacts outside the US should be based on the willingness to pay by those foreign countries” (page 91).

W. Kip Viscusi: “I disagree with the discussion of geographic scope. Agencies should be required to report the benefits to the United States, including benefits to US citizens and military who are abroad. The benefits to the US should serve as the primary analysis rather than possibly using global benefits … objective of US policies is not to promote worldwide social welfare but to reflect the preferences of the citizenry … knowing the benefits to the US is essential to better understand the equity implications for the US. The concerns with respect to equity expressed in Biden’s executive order cannot be addressed without this knowledge … When appropriate, as in the case of global warming policies, I also support the reporting of the global benefits … ultimately the benefit number that should be used for the SCC should be conceptualized as the benefits that can be traced to the benefit derived by the US either directly or indirectly” (page 107).

5.1. My reading

My reading of these reviewer comments on scope points to a focus on the separation of the net benefits to US citizens and the aggregate global net benefits that include both domestic and international effects. Kenneth Gillingham is the most supportive of aggregate global-only scope because of the infeasibility of reliable estimates of purely domestic net benefits. Joseph Aldy advises detailed justification for including effects outside the US and how the US benefits in international relations do not address separating domestic and international estimates. Christina Romer did not comment on this issue. The message I get from the remaining peer reviewers emphasizes net benefits for citizens and residents of the US. Together they make several related points.

First, primary analysis should be based on net benefits to US citizens and residents and their willingness to pay (WTP) for regulatory effects. WTP of US citizens and residents can include their values of regulatory effects on noncitizens residing abroad.

Second, supplementary regulatory analysis that includes values of noncitizens residing abroad should be separate from the primary analysis so that differences in scope are transparent.

Third, global estimates of regulatory effects that include effects on noncitizens residing abroad should include the WTP values of the noncitizens residing abroad.

6. Development of analytical baselines

Issues regarding the development of analytical baselines include expected compliance, exemptions, linkages with other current and anticipated regulations and policies, and multiple baselines.

Joseph Aldy: “the list of potential examples of ways in which conditions will change absent the regulation should also include other public policies. For example, tax policy, state/local regulatory actions, and regulatory actions by other federal regulators could influence how conditions would change in the absence of the regulation … The circular should call on agencies to identify one policy strategy beyond the scope of their regulatory authority as an alternative to evaluate. … Such an analysis could illustrate how statutory reform could lower the costs, increase the benefits, or improve the distribution of impacts of making progress in remedying the identified market failure. … task agencies to explain how a regulation is designed to facilitate 100% or near-complete compliance. Instead of taking the default approach of 100% compliance – without explanation – such a requirement could require the regulator to make the case for 100% compliance” (page 7).

Glenn Blomquist: “estimation of distributional effects can be even more challenging. Rigorous estimates should incorporate credible baselines, private behavior, and markets for housing, labor, and amenities. Homeownership and locational mobility can matter especially over time” (page 15).

Cary Coglianese: “The baseline should be to the world as it would exist without the regulation under consideration – and if that world is one in which other previously relevant regulations are not followed, then agencies should not assume a counterfactual world that “conforms” to those regulations … cautions agency analysts against simply assuming that the counterfactual baseline is one in which other regulations are complied with fully (page 41) … If the benefits of a regulation depend, say, on ongoing and consistent behavior by regulated entities – such as performing regular oversight or maintenance – it is not unreasonable to question whether compliance will be maintained over time. I read this part of the Circular to encourage agencies to consider how slippage in compliance may affect reasonable expectations of regulatory impacts. At a minimum, as the proposed update to the Circular makes clear, agency analysts should not blithely assume full compliance when conducting regulatory analyses (page 48) … agency analysts should consider the implications of waivers and exemptions in much the same way, and for similar reasons, that this section properly urges analysts to consider the implications of less than full compliance” (page 49).

Scott Farrow: “Include some discussion of compliance in this section as it sets up a further dimension of regulatory implementation – those actions that might affect compliance … Include a discussion of legally linked regulations as potentially part of the baseline (page 66).

Kenneth Gillingham: “regulatory analyses should be performed with a baseline that is as realistic as possible. This should include all regulations or policies that are currently on the books and can include regulations or policies that can reasonably be expected to be in place in the future. … if agencies make a case to include regulations or policies that are not yet implemented in the analytic baseline in the primary analysis, they should also always present the results from an analysis that only includes regulations and policies that have been implemented as a secondary analysis …. my primary recommendation on this is that I believe that there should be language to indicate that agencies should assume full compliance unless they provide evidence indicating that full compliance is unlikely” (page 74).

Christina Romer: “Although the circular is careful to mention resource constraints, I do worry that implementation of some of the proposed changes will be quite difficult. Take, for example, the development of an appropriate analytical baseline. It makes complete sense to consider the possible changes in technology, economic growth, and the impact of related government regulations in setting the baseline against which the costs and benefits of the new regulation are to be measured. However, the research, knowledge, and data necessary to calculate this baseline are likely to be very large. One has to ask whether the improved analytical baseline would itself pass a cost–benefit test” (page 101).

W. Kip Viscusi: “My main suggestion is that the status quo serve as the baseline unless the RIA provides empirical evidence, specific evidence of future policy changes, or other regulatory guidance that provides a credible basis to assume a different temporal pattern for benefits and costs” (pages 107–108).

6.1. My reading

My reading of the comments on the development of analytical baselines finds several notable points about status quo, compliance, linkages, and difficulty. Peer reviewers do not always agree, but it is safe to say that these points should be considered more carefully.

Status quo. W. Kip Viscusi advises that the status quo should be the baseline unless a credible basis for something different is given. Kenneth Gillingham advises that the baseline should include current regulations or policies and possibly anticipated regulations or policies. If relevant, secondary analysis should report results based on only implemented regulations and policies.

Compliance. Joseph Aldy advises that agencies explain how a regulation is designed to facilitate 100% compliance and defend assuming complete compliance. Scott Farrow says it should be part of the discussion of implementation. Cary Coglianese urges analysts to consider the implications of less than full compliance and also legal slippage through waivers and exemptions. Kenneth Gillingham offers a different recommendation, namely that full compliance be assumed unless there is evidence indicating that it is unlikely.

Linkages. Scott Farrow recommends consideration of legally linked regulations as part of the baseline. Joseph Aldy suggests listing other public policies such as tax policy, state and local actions that will change without the proposed regulation. Kenneth Gillingham advises that if anticipated regulations or policies are part of the baseline, a second analysis should be based on only existing regulations.

The potential difficulty and costliness of developing appropriate baselines especially for growth, technological change, and distributional effects is noted by Christina Romer and me. Joseph Aldy calls for an illustrative policy strategy beyond the scope of agency regulatory authority to demonstrate benefits of alternatives. These are among the many comments on analytical baselines from the peer reviewers.

7. Unquantified impacts

Issues regarding unquantified impacts include how to report unquantified and how much to describe unquantified and non-monetized effects alongside any table.

Joseph Aldy: “Guidance does a good job…” (page 10).

Glenn Blomquist: “The sections on revealed preference, stated preference, and benefit transfer methods are excellent in that they reflect progress made in estimating methodology and technique (page 14) … Any measurement and valuation of human dignity, civil rights, liberties, or indigenous cultures would have to be done with care and sensitivity… exploratory efforts have been made by Maria Ponomarenko and Barry Friedman to incorporate these values into benefit–cost analysis of policing practices” (page 26).

Cary Coglianese: “strongly encouraging agencies to refer to these unmonetized or unquantified impacts within or at least very near the same summary tables that list monetized or quantified impacts (pages 42–43) … The first step in any benefit–cost analysis should be for the agency to identify all the anticipated consequences of a new regulation—and then it can go about determining which of these effects can be quantified and monetized” (page 47).

Joseph Cordes: “a list is that it makes clear that in conceptualizing a benefit–cost analysis, all possible benefits and costs – intangible as well as tangible – should be identified and discussed” (page 54).

Kenneth Gillingham: “I strongly support the guidance allowing for unquantified impacts to be mentioned (page 75) … My biggest recommendation relating to non-monetized and non-quantified effects is to very strongly encourage the agencies to at least attempt to monetize (or at least quantify) the effects” (page 79).

7.1. My reading

My reading of comments on unquantified impacts is that these notable proposed updates mostly met with approval. Affirmation is there for the five peer reviewers who had made any comment. I imagine the other four were sufficiently satisfied given their interest and expertise that they chose to devote their energies elsewhere. To me, it reflects the progress made in nonmarket valuation during the 20 years since the 2003 Circular A-4 Guidance. The main suggestions are to identify all benefits and costs related to the proposed regulation, strive to quantify and value them as much as is possible and practical, and present results with tangible and intangible effects.

8. Uncertainty

Issues regarding uncertainty include the removal of the presumption of risk neutrality and the assumption of risk aversion in valuing uncertain outcomes, and the adoption of certainty-equivalent valuations.

Cary Coglianese: “conduct analyses using multiple reasonable discount rates, using different assumptions about distribution, providing multiple baselines, and so forth (page 43) … may also be appropriate for agency analysts to compare the results they obtain under risk aversion with results that would apply under risk neutrality – and vice versa” (page 44).

Joseph Cordes: “At minimum undertaking even a simple incremental sensitivity analysis should be required as a strongly recommended best practice in regulatory impact analysis. More sophisticated forms of sensitive analysis based on Monte Carlo simulations are increasingly accessible in excel-based programs such as Crystal Ball, and agencies should be encouraged to adopt these technologies” (page 53).

Kenneth Gillingham: “I strongly recommend allowing for the use of certainty equivalents in the treatment of uncertainty but clarifying that such analyses should be performed upon consultation with OIRA and in most cases should be secondary analyses” (pages 77–78).

William Pizer: “The importance of addressing uncertainty, particularly through sensitivity analysis of key uncertain variables or through probabilistic analysis, remains largely unchanged and highly relevant/important (page 88) … the proposed revisions (pages 71–73) lean more toward an assumption of risk aversion and provide a much greater focus on the idea of computing certainty equivalents. While conceptually correct, most government cost–benefit guidance has focused on risk-neutrality as the default … for most cost–benefit analysis, an assumption of risk neutrality (distinct from risk and discounting) would remain a reasonable choice” (page 88).

Christina Romer: “revised circular calls for analysts to calculate the certainty equivalents of the stream of future costs and benefits, and then discount them using the real risk-free rate … this approach may be overly difficult for a number of reasons. It may also lead to substantial understatements of the importance of risk (page 97) … no matter how it is done, accounting for uncertainty will be time-consuming and analytically challenging. But it is likely that the certainty equivalence approach is going to be substantially more difficult (page 98) … the circular should provide a “default” risk-adjusted discount rate to be used, with agencies having leeway to use a different discount rate if the analysis indicates it is warranted by the risk profile of the net benefits of the regulation being considered (which could point to a rate either lower or higher than the default rate) (page 100) … It is essential that year-by-year values of the real monetized costs and benefits be reported so that it is easy for others to try alternative discount rates. This would ensure that the issue of appropriate discounting is kept separate from the stream of estimated costs and benefits” (page 102).

W. Kip Viscusi: “surprising reference to non-expected utility frameworks. Expected utility theory is generally accepted as the normative reference point … It is important for OMB to emphasize that risk assessments should be guided by the mean risk levels, not the upper bound of the risk” (page 108).

8.1. My reading

My reading is that the proposed notable updates about uncertainty prompted comments on two subtopics. Sensitivity analysis is advised by four of those who made specific comments. It is standard, best practice in benefit–cost analysis. I certainly support it and am almost certain that support would come from the other peer reviewers who did not comment specifically. Risk neutrality appears to be acknowledged as the norm for most benefit–cost analysis with sensitivity analysis exploring risk aversion when appropriate. Related is the caution when trying to use certainty equivalents and a reluctance to use them in primary analysis.

9. Peer review on notable proposed updates to circular A-4: Consensus?

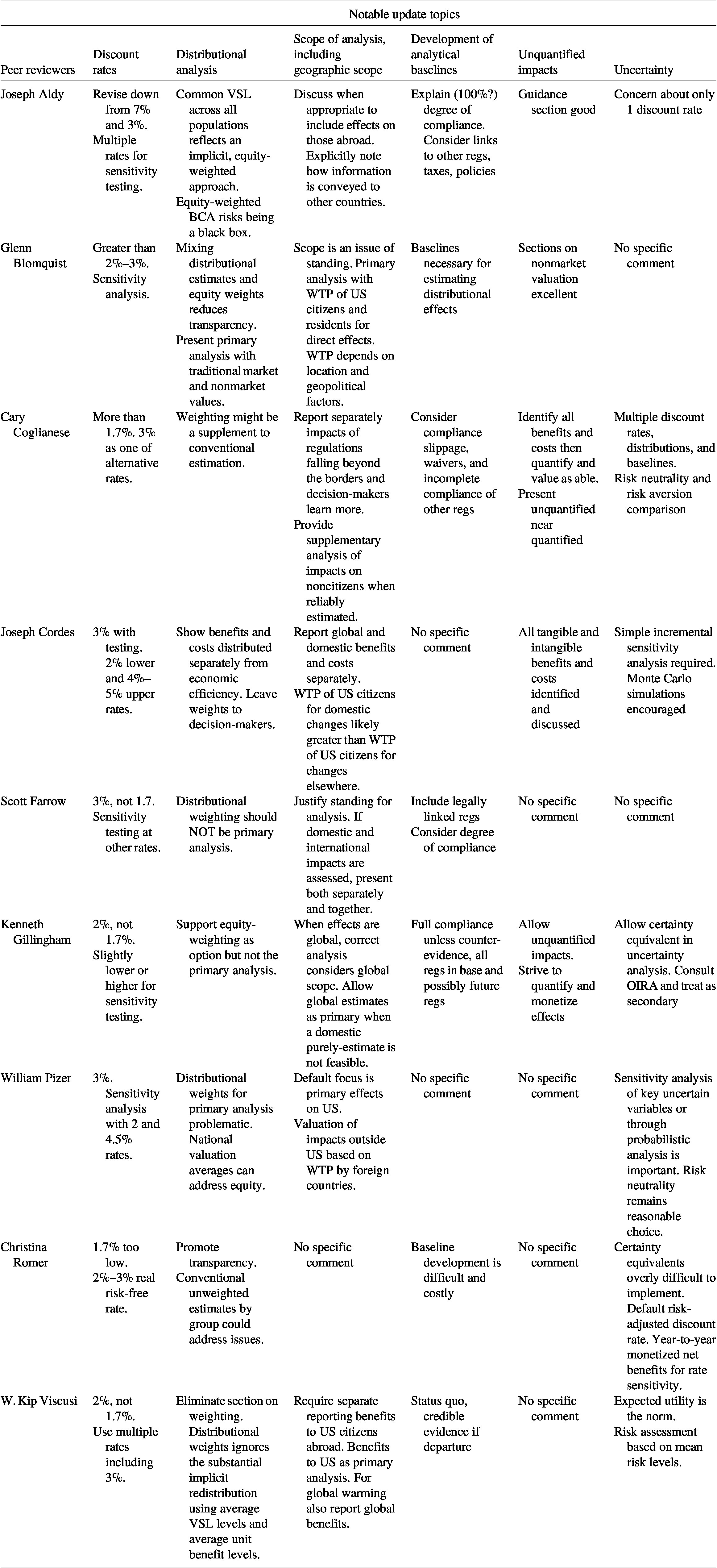

The purpose of this synopsis is to summarize the comments of the nine peer reviewers selected for OIRA/OMB on the six topics identified by OIRA as “notable proposed updates.” I have selected quotations to try to convey the gist of comments on each of the notable proposed updates by reviewers. To distill the summary and comparison of the peer reviews further, I have chosen key phrases for a table by author and topic, see Table 2.

Table 2. Peer reviewer consensus on notable proposed updates of OMB circular A-4

Source: Author.

Regarding consensus, I share the following thoughts on the main points.

Discount Rate: (1) 1.7% as the core rate reflects unfounded precision, (2) sensitivity analysis with alternative rates should be required, (3) 1.7% is too low, and (4) 3% might be a consensus rate.

Distributional Analysis: (1) conventionally estimated net benefits should be the primary analysis, (2) estimate standard benefits and costs by group and report separately, (3) equity weighting of net benefits should be a supplementary analysis if done, and (4) standard practice of using a population average VSL already reflects implicit equity weighting for health and safety effects.

Scope of Analysis: (1) primary analysis should be based on net benefits to US citizens and residents and their willingness to pay for regulatory effects. WTP of US citizens and residents can include their values of regulatory effects on noncitizens residing abroad, (2) when global effects are relevant domestic benefits should be reported separately from global benefits, (3) feasibility of separating effects is an issue and should be dealt with explicitly by the agencies, (4) benefits to US citizens and residents should be based on their WTP, and (5) any benefits to nonresidents should be based on their WTP.

Development of Analytical Baseline: (1) Expected degree of compliance whether 100% or less and slippage should be explained and justified, (2) linkages to other regulations and policies and interactions with the regulation being analyzed should be considered, and (3) baselines with and without other anticipated regulations and policies should be considered.

Unquantified Impacts: (1) Identify all important regulatory effects and include as many as possible in the benefit–cost analysis, and (2) present results including important intangible or unquantified impacts.

Uncertainty: (1) Sensitivity analysis is standard practice and should be done for important parameters or preferably using Monte Carlo simulations, and (2) risk neutrality is the norm with sensitivity analysis that explores risk aversion when appropriate.

When asking nine peer reviewers with various backgrounds to comment on six proposed revisions to guidance on regulation, we might expect to get at least 10 different views on each. For the last three notable proposed revisions, I sense peer reviewer support overall regarding improvements in the analytical baseline, treatment of unquantified impacts, and sensitivity analysis to deal with uncertainty. Comments seem to be ideas worth pursuing and thoughtful suggestions. On the first three updates, based on my synopsis, I sense basic agreement on key aspects also. Some may find this agreement remarkable.

The agreement among peer reviewers is reassuring. The degree to which the final Circular A-4 issued on November 9, 2023 reflects their advice, in contrast, is not reassuring. My reading is that the final guidance does not reflect the near consensus among peer reviewers on discount rate, distribution, and scope; it is ignored. The concern is concentrated on guidance for primary (core or base) case analysis. The guidance on the discount rate merely rounds up and still emphasizes a low rate of 2% with little role for serious consideration of alternative higher rates to play. Utility weighting of benefits and costs is emphasized and allows for utility-weighted estimates as primary analysis. The scope of analysis allows for global estimates as the primary analysis. My own review aside, I would have expected greater concurrence between the advice of OIRA’s selected peer reviewers and OIRA’s guidance on notable revisions in the final Circular A-4 issued. When I wrote this synopsis in summer 2024, I wrote that time would tell if the revised Circular A-4 will be as durable and useful as the last. At the time, none of us knew it would be rescinded.

In addition to peer review, public comments were solicited. OIRA chose to respond with explanations to public and peer reviewer comments altogether on a wide variety of topics in the proposed Guidance rather than respond to specific comments from the selected peer reviewers on the notable proposed updates. See OMB Circular No. A-4: Explanation and Response to Public Input (November 9, 2023) available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/EO/fedRegReview/CircularA4Explan.pdf. Actual changes made to the draft guidance are described in Comparing the Draft and Final Circular A4 by Mark Febrizio, Sarah Hay, Zhoudan (Zoey) available at https://www.benefitcostanalysis.org/assets/docs/Working%20Paper%20-%20Hay%20et%20al.pdf and in this special of issue of the Journal of Benefit–Cost Analysis.