Introduction

For the first time, the 2021 Australian population census contained a question about the long-term health conditions of all citizens (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a). These health data were analysed in relation to the various socio-economic, cultural, and demographic characteristics of participants. The main objective of this paper was to analyse the self-reported health conditions prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and compare them with those in the total population.

There is a large and growing body of research about the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, comparing the disease burden borne by them with that borne by the non-indigenous people (Claire et al., Reference Claire, Elyse, Macdonald and Brassard2020; Gracey and King, Reference Gracey and King2009). There is also extensive study of the impact of culture on the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Crooks et al., Reference Crooks, Tully, Allan, Gilham, Durrheim and Wiggers2022; McEwan et al., Reference McEwan, Tsey, McCalman and Travers2010; McKivett et al., Reference McKivett, Paul and Hudson2019). Specifically, research has addressed problems such as hearing loss (Poirier et al., Reference Poirier, Quirino, Allen and Stephens2022), heart and other cardiovascular illnesses (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Keech, McBride, Kelly, Stewart and Dowling2016), and mental health disorders (Dudgeon et al., Reference Dudgeon, Milroy and Walker2014). Both Gurney et al., (Reference Gurney, Stanley, McLeod, Koea, Jackson and Sarfati2020) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Health Performance Framework for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017) have shown the heavier burden and poorer outcomes among these communities.

Most of the research so far is based on small surveys or statutory collections of information, such as mortality data (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018), rather than nationwide data as contained in the 2021 population census of Australia.

Methods

The 2021 Census Household Form (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a) included the following question (Question 28):

‘Has the person been told by a doctor or nurse that they have any of these long-term health conditions?

-

o Arthritis

-

o Asthma

-

o Cancer (including remission)

-

o Dementia (including Alzheimer’s)

-

o Diabetes (excluding gestational diabetes)

-

o Heart disease (including heart attack or angina)

-

o Kidney disease

-

o Lung condition (including COPD or emphysema)

-

o Mental health condition (including depression or anxiety)

-

o Stroke

-

o Any other long-term health condition(s)

-

o No long-term health condition’.

Respondents were asked to mark all health conditions, including those which lasted, or are expected to last, for six months or more, or may recur from time to time, or are controlled by medication, or are in remission.

The response rate for this question was 91.8% for both the total population and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Another question relevant to this study was Question 11:

‘Is the person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin?

-

o No

-

o Yes, Aboriginal

-

o Yes, Torres Strait Islander’.

People of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin were asked to mark both ‘Yes’ boxes. This question was answered by 95% of the total population.

Data about age were available in quinquennial groups from 0–4 to 95–99 and 100+. These were recoded into nine groups: <15, 15–24, …, 80–84, and 85+. Gender was coded into males and females only. There was no non-response to these two questions.

Full access to the 2021 census database was available to the authors using special software – TableBuilder Pro. This enabled them to produce up to 4-way cross-classifications for statistical analysis.

Standardised Morbidity Ratios (SMR) were calculated for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples using the indirect standardisation procedure (Yusuf et al., Reference Yusuf, Martins and Swanson2014). The SMR for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who reported a particular health condition was estimated as:

where ‘Actual’ was the number of persons reporting a particular health condition and ‘Expected’ was the number for the same condition among the same people if they had experienced the age-condition specific rates of the ‘standard population’, i.e., the total population of Australia.

Denominator in the above equation was estimated as:

where

![]() ${s^k}$

was the condition-specific rate for age k in the ‘standard’ population, and

${s^k}$

was the condition-specific rate for age k in the ‘standard’ population, and

![]() ${P^k}$

was the population of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were aged k (age range: <15 to 85+). The SMR indicates whether the age-standardised prevalence of the particular condition among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was the same (SMR=1) or higher (SMR >1) or lower (SMR <1) compared to that in the total population.

${P^k}$

was the population of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were aged k (age range: <15 to 85+). The SMR indicates whether the age-standardised prevalence of the particular condition among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was the same (SMR=1) or higher (SMR >1) or lower (SMR <1) compared to that in the total population.

Results

Demographic profiles

According to the 2021 census, the population of Australia was 25.423 million. The majority (92%) reported that they were non-indigenous, 3.2% were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the remaining 4.9% did not answer Question 11.

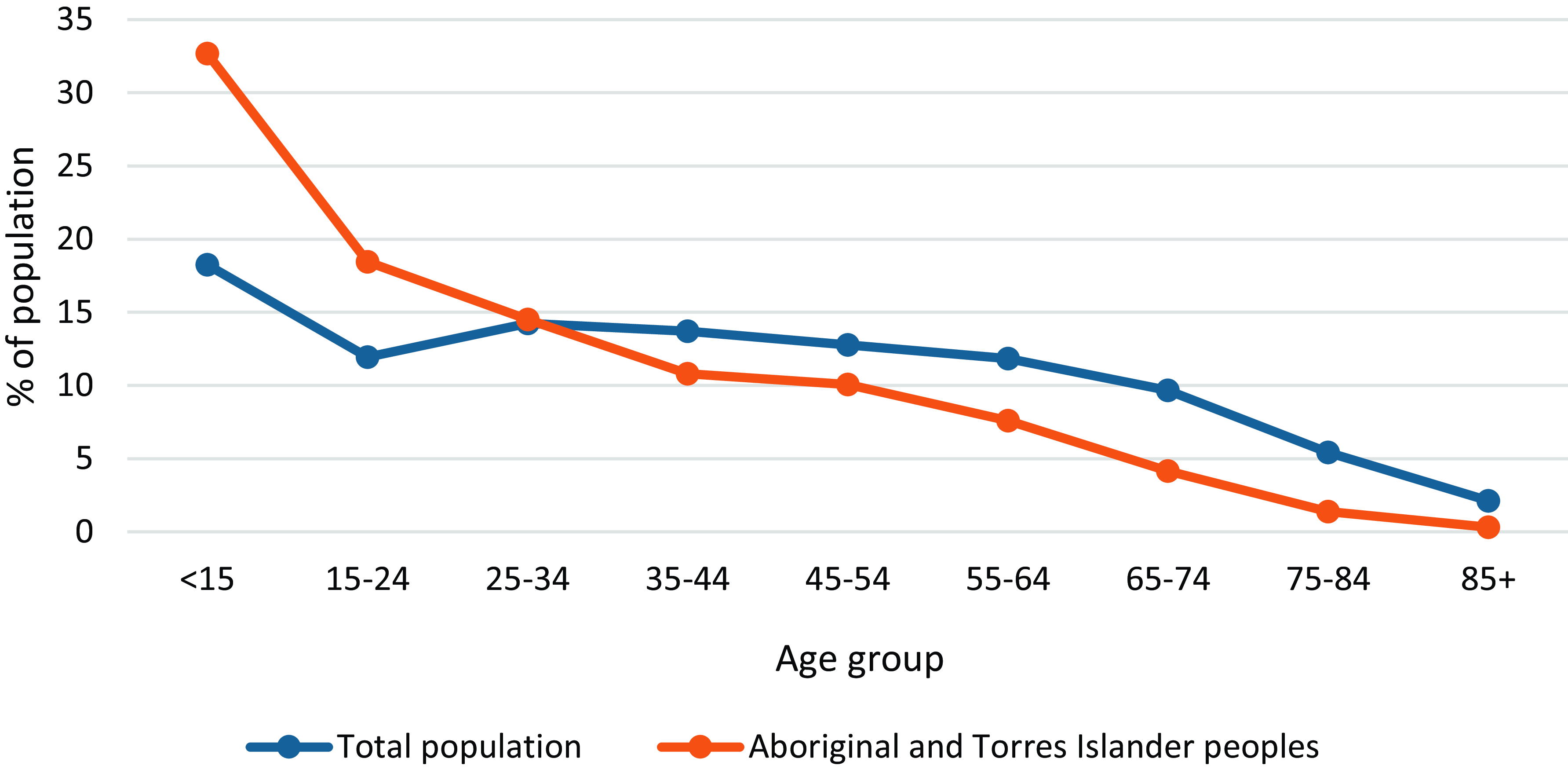

Age distributions of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the total population are shown in Figure 1. The former group comprised a larger proportion of younger persons (indicating higher fertility) and a smaller proportion of older persons (indicating higher mortality) than the latter group. Median ages were 24 and 39 years, respectively. Because of the substantial age differences between the two groups, it was essential to use the SMRs in order to compare the differences in the prevalence rates of the two groups.

Figure 1. Age distributions for the total population and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Australia, 2021 Census.

There was not much difference in the proportion of females among the two groups, 53% and 51%, respectively.

Number and type of self-reported long-term health conditions

Table 1 shows that a larger proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reported one or more long-term health conditions than did the total population. The median ages at which the former group reported one or more conditions were substantially lower than in the total population. The proportions of females reporting none or one condition were similar in the two groups, but the proportion of females reporting two or more conditions was higher among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Table 1. Percentage of Population, Median Age, Proportion Female, and Standardised Morbidity Ratios by the Number of Self-Reported Long-Term Health Conditions for the Total Population and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Australia, 2021 Census

1. Based on 23.357 million persons in the total population who responded to Question 28.

2. Based on 0.747 million Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who responded to Question 11.

3. Calculated by using the age-condition specific rates of the total population as the ‘Standard’.

Table 2 shows that, among those who reported one or more long-term health conditions, 72% said they had suffered from one or more of the ten health conditions listed in the census. The remaining 28% suffered from a long-term condition other than those options listed in the census.

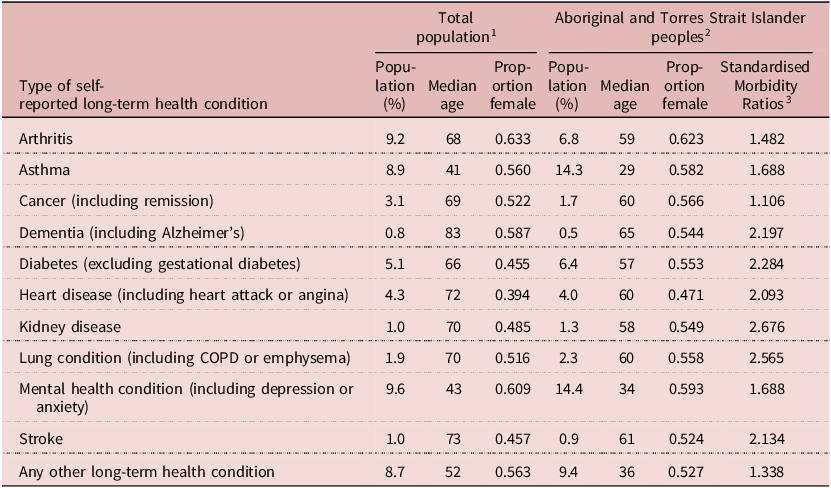

Table 2. Percentage of Population, Median Age, Proportion Female, and Standardised Morbidity Ratios by the Type of Self-Reported Long-Term Health Conditions for the Total Population and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Australia, 2021 Census

1. Based on 23.357 million persons in the total population who responded to Question 28.

2. Based on 0.747 million Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who responded to Question 11.

3. Calculated by using the age-condition specific rates of the total population as the ‘Standard’.

Mental health problems were the most commonly reported condition among those in the total population with one or more health conditions, closely followed by arthritis and asthma. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the most commonly reported conditions were mental health problems and asthma, with rates well in excess of the total population. The only condition where the prevalence was lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was cancer, where the rate was less than half that in the total population.

Table 2 also shows that the median age of people reporting each of the health conditions was lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than among the total population, usually by about 10 years.

The SMRs for each of the conditions were higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared with the total population. The gap was largest in the case of kidney disease, where prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was 2.7 times that in the total population. Cancer was an exception, with rates only slightly higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Age-specific prevalence rates of self-reported long-term health conditions

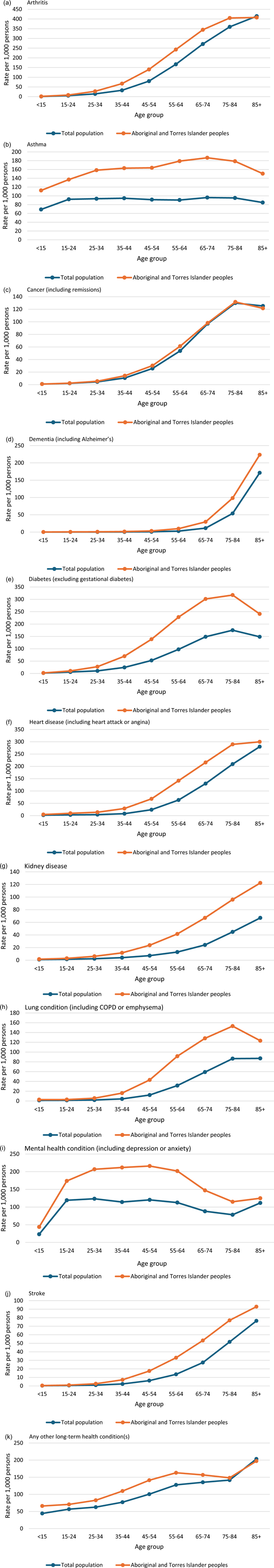

The age-specific prevalence rates for each health condition for the total population and for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for various long-term health conditions are shown in Figures 2(a) through 2(k).

Figure 2. Age-specific prevalence rates of long-term health conditions reported by the total population and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Australia, 2021 Census.

The patterns had common features. They rose steadily from negligible levels in the youngest age groups, reaching peaks in the older age groups. Rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were above those for the total population for all age groups and all conditions, except for cancer, where the rates were indistinguishable.

The age-specific rates for asthma were stable in the total population across all ages. The rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were much higher in all age groups. Also, rather than reaching a plateau in the young, they increased to a maximum in the 65–74 years age group at approximately twice the rate in the total population.

The rates of mental health problems in the total population were high among young people, then plateaued and returned to a high level in older people. The pattern among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was different in two respects: they were 50% higher than the total population in the 15–24 age group, rising to a peak in the 45–54 age group – twice as high as the total population. In contrast to the other long-term conditions, the rates for cancer (and to a lesser extent, dementia) were similar in the total population and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the total population was particularly marked in relation to diabetes – excluding gestational diabetes – (Figure 2(e)), kidney disease (Figure 2(g)), lung condition – including COPD or emphysema – (Figure 2(h)), mental health condition – including depression or anxiety – (Figure 2(i)) and stroke (Figure 2(j)).

Discussion and conclusion

The 2021 census revealed major disparities in the rates of several long-term conditions reported by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared to the total population. The gaps can be related to differences in the social determinants of health and illness and to variations in access to effective medical and surgical care. These findings are consistent with studies, mainly based on surveys, of indigenous peoples in Canada (Government of Canada, 2023) and Maoris in New Zealand (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Barnard, Kvalsvig and Verrall2012; Durie, Reference Durie2012; Robson and Harris, 2007). Although the 2021 Canadian census (Statistics Canada, 2024) had a question concerning health (Question 18), it was not in a way that was directly comparable to Question 28 of the 2021 Australian census (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a).

The findings relating to cancer were unexpected, as other studies indicate higher cancer morbidity and poorer outcomes among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For example, it was noted that the ‘Indigenous Australians have a slightly higher rate of cancer diagnosis and are approximately 40 per cent more likely to die from cancer than non-Indigenous Australians’ (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017). They also estimated that the disease burden from cancer among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was 1.5 times that among non-indigenous people and that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples ‘… were 2.9 times as likely to be a current smoker compared with non-Indigenous Australians in 2018-19’ (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017).

A reluctance to self-report cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples might be explained by the special position cancer occupies in those communities (Australian Indigenous, undated; Daher Reference Daher2012; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Marziliano and Moyer2014). Cancer Australia reported a greater stigma associated with cancer and ‘a general reluctance to talk about cancer’ (Australian Government, 2022; Cancer Australia, 2022; Cancer Nurses Society of Australia, undated). There was fear that cancer was a death sentence, and also a fear of cancer treatments.

There are important limitations pertaining to the data on which this paper is based. For example, despite the statistical and comparison checks the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) conducts to establish internal consistency and to identify discrepancies, censuses remain vulnerable to minor distortions as there is no practical method of reliable, independent checking on the validity of any particular set of responses.

With very few exceptions, the census was self-enumerated by the reference person in the household rather than administered by a trained interviewer. If there was a misunderstanding of a question, this would go unnoticed in the response.

Despite the best efforts of the ABS to optimise coverage of the census in very remote areas, inevitably, remote areas will not be as well served as urban areas. A larger proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples live in very remote areas compared with the total population. This sparseness of coverage might lead to under-enumeration in remote settings and to under-reporting of health conditions. The ABS notes that groups who might be underrepresented include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022b).

The Australian census was also reliant on the accurate self-reporting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s status and the long-term health conditions listed in the census questionnaire. Any perceived stigma or reluctance to identify might lead to under-reporting. It is also possible that the prevalence of any of the conditions might be understated as the individual might be asymptomatic, undiagnosed, or otherwise unaware that they actually have the condition.

This paper confirms the need to maintain efforts directed at improving the health experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For example, their access to medical and surgical care deserves further attention.

The conditions reported in the census are all ones that might respond to public health interventions and improvements in the physical and social environment. The deficits in health-sustaining environments require continuing efforts if the gaps between the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and that of the total population are to be closed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the ABS for giving them free access to their TableBuilder software along with the 2021 census data.

Disclosure statements

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organisation.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest in writing the manuscript, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

This study was conducted in compliance with the requirements of the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney.