Yin-yang Officers in Late Imperial China

Historians often envision the local face of the Qing state in the form of the county magistrate, the lowest ranked (7A out of the 1A–9B eighteen rank scale) official directly appointed by the central government in late imperial times. Long celebrated in popular fiction, the magistrate held a distinct level of prestige in governance as the “principal seal-holding official” (zhengyin guan 正印官) of a county.Footnote 1 Yet, a wide range of officials not directly selected for service by the central government and ranked lower than magistrates also exercised substantial power in local settings.

These officials collectively outnumbered county magistrates and, in many instances, remained in office longer. Unbound by the rule of avoidance that barred centrally appointed officials from serving in their native provinces, these lower-ranking functionaries moved with ease through local dialects, regional customs, and the intricate power relations specific to their home terrains. And even though these officials have not been studied as thoroughly as county magistrates, to many people in Qing society they represented some of the most readily recognizable faces of the imperial state.

Yin-yang officers, originating as the principals of yin-yang schools (yinyangxue 陰陽學) created under the Mongol Yuan (1271–1368), were one such kind of low-ranking official. Over the centuries, their role evolved from that of public educators to more ceremonial and supervisory functions, as institutional support for the divinatory schools waned.Footnote 2 By the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1636–1912) periods, yin-yang officers joined medical officers and the heads of Buddhist and Daoist Assemblies as unranked local officials appointed for their technical and religious expertise at the county level.Footnote 3 At the prefectural level, their equivalents received the official rank of 9B.Footnote 4 These civil servants stood at the lowest tier of the formal bureaucracy, positioned at the administrative boundary where the category of “official” (guan 官) shaded into that of “clerks” (li 吏) and other auxiliary personnel such as runners, doormen, coroners, and guards.Footnote 5

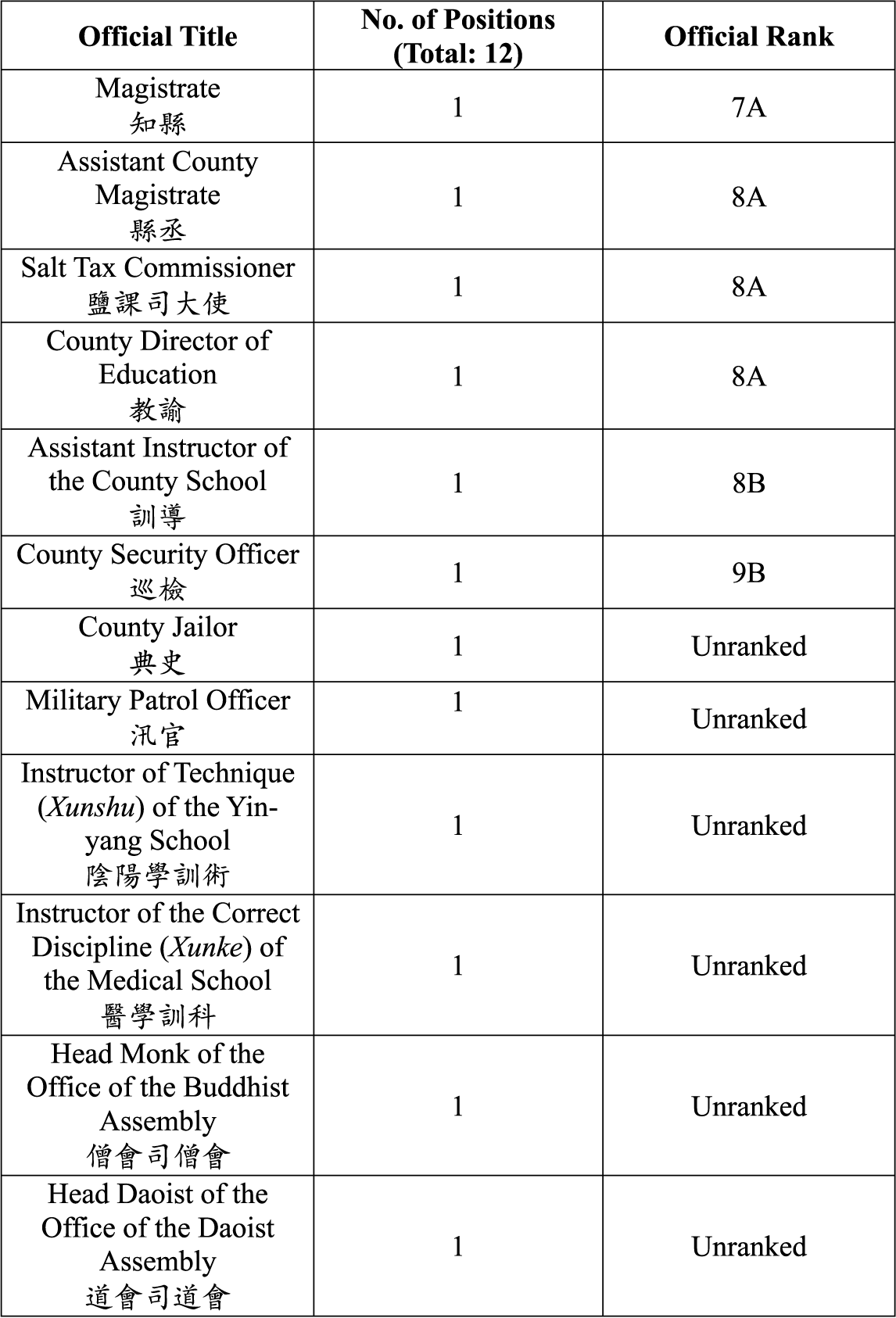

Despite their low rank, county and prefectural yamens (yamen 衙門) across China employed yin-yang officers during the Qing period.Footnote 6 For example, the Kaifeng prefectural yamen, which governed fourteen counties in Henan—including the seat of the provincial government—maintained sixteen official positions in the eighteenth century, one of which was designated for a yin-yang officer (Figure 1).Footnote 7 Likewise, Nanbu County in Sichuan Province, home to one of the largest surviving local Qing archives in China, employed twelve officials, including one yin-yang officer (Figure 2).Footnote 8 Similar staffing patterns appear across the empire, with religious, medical, and divinatory specialists collectively making up between a third and a quarter of the official positions working out of or around county and prefectural yamens. While a much larger number of clerks and runners also worked in these institutions, they were not classified as officials.Footnote 9

Figure 1. Official positions in the Kaifeng prefectural government, Henan Province (1735).

Figure 2. Official positions in the Nanbu county government, Sichuan Province (1849).

This study examines the diverse responsibilities assigned to yin-yang officers and then considers their implications for imperial governance. These officials appear frequently in county archives, as they were tasked with selecting auspicious dates for state rituals and bureaucratic undertakings in accordance with the imperial calendar, applying principles of fengshui and astrology in local governance, conducting meteorological observations, performing ritual responses to eclipses, coordinating seasonal festivals, assisting in the administration of examinations, policing heterodox religious activity, managing bell and drum towers, and even contributing to forensic investigations.Footnote 10 In addition to their official duties, these officers earned income by acting as local practitioners of “applied cosmology.”Footnote 11

Given the wide-ranging nature of these duties, it becomes necessary to review not only the administrative functions of yin-yang officers, but also their significance within the broader architecture of Qing administration. As such, this article argues that these officials formed part of a vast, locally embedded ritual and religious bureaucracy that operated alongside—and in key respects, distinct from—the more familiar civil bureaucracy shaped by the examination system. The effectiveness of this lower bureaucracy in exerting rural control for the state is debatable, but what is unmistakable is that it endured to the end of the imperial period in 1912. The evolution of this bureaucracy offers critical insights into the imperial state’s capacity to shape, accommodate, or respond to the challenges and transformations of Chinese rural society during the Qing.

Recent scholarship has reflected growing interest in local officials such as yin-yang officers, particularly during the Ming period. The scholarly consensus highlights institutional and functional transformations in the role from the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries. Historian Wang Jichen observes a decline in Ming state oversight of yin-yang schools, with yin-yang officers becoming increasingly embedded in rural society as ritual functionaries.Footnote 12 Yonghua Liu offers a complementary perspective, highlighting the adaptability of the position over time as it expanded into ritual performance and temple administration, merging with and manifesting as popular “masters of ritual” (lisheng 禮生) in southeastern China.Footnote 13 Yin Minzhi, meanwhile, draws attention to one of the role’s practical attractions during the Ming: the exemption from corvée labor granted to professional yin-yang specialists beginning in 1428.Footnote 14

Moving into the Qing period, however, yin-yang officers remain comparatively understudied. What is clear is that the institutional infrastructure—namely, schools dedicated to yin-yang learning—generally declined during the Ming and, with few notable exceptions, continued to do so in the Qing. Yet despite the erosion of formal educational institutions, the position of yin-yang officer did not disappear. Rather, it evolved into a pragmatic role embedded within local administrative structures, fulfilling both ritual and regulatory functions within the Qing state’s broader system of governance. As discussed further below, in many localities, the role even experienced periodic moments of resurgence over eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Researching yin-yang officers presents a significant challenge due to the scarcity of surviving published sources written by or dedicated to them. In contrast, the work of county magistrates and higher-ranking officials is well-documented in extensive administrative records and private writings. To overcome these limitations and offer a more comprehensive understanding of yin-yang officers’ roles and influence, this article examines county and palace archival records, official and administrative handbooks, popular encyclopedias, divination texts, collected “vermillion scroll” (zhujuan 硃卷) family genealogies of metropolitan and provincial examination candidates, and local gazetteers.

The local gazetteers analyzed below originate from twelve of the eighteen provinces of the empire’s interior.Footnote 15 These texts were accessed through the Local Gazetteers Research Tools (LoGaRT) database at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin. This database provides a broad collection of data on yin-yang officers across the Qing Empire, enabling observations on both general trends and exceptional cases. Local gazetteers as a genre tend to highlight local triumphs while minimizing failures and controversies, often casting a favorable light on the listed office holders. When yin-yang officers appear in these records, it is typically to commend their service or contributions to a county or prefecture. By contrast, archival lawsuits provide a more critical—though not uniformly negative—perspective, as geomancers, Daoists, Buddhists, and other groups figured in contentious legal disputes.

The pages that follow enrich gazetteer narratives with local archival records, offering a fresh look at the Qing administration by looking at a role that was nearly forgotten in twentieth century historiography. The next section introduces the profession of yin-yang officers as defined by imperial regulations, while the following ones map the locations where they worked, discuss the circumstances of their selection, appointment, and removal, and explore their duties during key festivals and eclipses. These roles highlight their enduring relevance within the bureaucratic and ritual landscape of late imperial China, persisting across centuries and dynastic transitions to the turn of the twentieth century.

Defining the Position

“Yin-yang officer” is a broad translation of three different positions (zhengshu 正術, dianshu 典術, and xunshu 訓術) in the Qing bureaucracy, as outlined in the Collected Statutes of the Great Qing (Da Qing huidian 大清會典; 1764). The positions are described in that text in the following terms:

All yin-yang masters are to be selected for their knowledge of the divinatory arts by officials in the directly administered provinces [i.e., the empire’s interior]. Their identities are to be sent up to the governor-generals and the provincial governors, who will then consult the Board [of Rites] to issue a notice designating them to serve as the administrators of Yin-yang Schools.

凡陰陽家, 由直省有司官擇明習術數者, 申督撫咨部給劄為陰陽學。

One person shall be appointed for this role at the prefecture, sub-prefecture, and county levels, respectively. The prefectural officer is called a “Bearer of the Correct Technique” (zhengshu 正術) (this position is ranked 9B), the sub-prefectural officer is called a “Bearer of the Standard Technique” (dianshu 典術), and the county officer is called an “Instructor of Technique” (xunshu 訓術) (these latter two positions are unranked).Footnote 16

府州縣各一人, 府曰正術〈從九品〉, 州曰典術, 縣曰訓術, 〈均未入流〉。

They [i.e., the officers] oversee the local diviners and geomancers within their jurisdiction and forbid them from using wild theories to delude the people.Footnote 17

以轄日者形家之屬, 禁其幻妄惑民。

Whenever there are major ritual ceremonies or large-scale construction in prefectures and counties, these persons shall be employed to divine the proper day and time [to begin the ceremony or construction].Footnote 18

郡邑有大典禮、大興作, 卜日候時用之。

Qing regulations thus specified that yin-yang officers had to be: 1) well-versed in the divinatory arts, 2) selected for service in their localities and then formally appointed by higher-ranking officials, 3) responsible for overseeing local geomancers and encouraging orthodox beliefs and practices in their districts, and 4) responsible for selecting the start times for prominent government rituals and construction projects. While officeholders were men, it was not uncommon for some of the spirit mediums and diviners they oversaw to be women.Footnote 19

The regulations above do not specify the payment structure for yin-yang officers, but their nominally low compensation appears to have been linked to the enduring institutional stability of the position. Within the Qing bureaucracy, base salaries (fengyin 俸銀) for officials varied based on rank and title. For instance, Prefects (rank 4B) earned between 62 and 105 taels annually during the eighteenth century, depending on the post.Footnote 20 These base salaries were complemented by much larger amounts of “nourishing honesty silver” (yanglianyin 養廉銀), which for a Prefect could exceed 3,000 taels. While some officials ranked 9B were entitled to modest base salaries, yin-yang officers—like their counterparts in the Medical Bureau—did not receive official salaries. Nor did they receive “nourishing honesty silver,” which the government provided only to officials ranked between 1 and 7A.Footnote 21 For the Qing government, these low-ranking officials were inexpensive to maintain on staff.

Yin-yang and medical officers received basic provisions, such as clothing and food allowances, from the prefects and magistrates under whom they served.Footnote 22 In addition, many likely received informal stipends from these officials, which helped supplement their livelihoods. The primary source of income for yin-yang officers, however, came from fees collected from the public. They were compensated for officiating rituals, selecting auspicious dates, and offering advice on calendrical and geomantic matters. Officers collected fees from the hundreds of local diviners they supervised, who paid in order to remain in the government’s good graces as law-abiding fortune-tellers. Some officers earned further monetary support through connections to trades broadly related to their expertise, such as coffin-making.Footnote 23

Because private-sector work was so plentiful, yin-yang officers sometimes sought ways to avoid their official duties. When a yin-yang officer was unable to fulfill a routine government assignment—such as traveling to Chengdu to assist with logistics for the triennial provincial examinations—he was required to remit a fee of eight taels, which was then forwarded to provincial authorities in Chengdu.Footnote 24 Many officers opted to pay the fee rather than travel for work, as they were earning good money locally. Their private consulting was often lucrative precisely because it blurred the lines between personal gain and official responsibility. Frustrated by entrenched corruption, one vice-prefect in Ningyuan Prefecture, Sichuan Province, reported in 1903 that yin-yang officers extorted exorbitant fees from local diviners, often amounting to more than ten times the legal amount.Footnote 25

Despite occasional allegations of corruption, the integration of the divinatory arts into local governance produced tangible benefits for practitioners, the state, and society at large.Footnote 26 For yin-yang officers, the position provided a platform to leverage their governmental status into profitable private consulting practices in astrology, geomancy, and ritual services—an example of what Michael Szonyi characterizes as “proximity to the state.”Footnote 27 By extension, the role offered the cost-conscious Qing administration a practical means of alleviating the fiscal burden of a fully salaried bureaucracy. Alongside other officials of rank 9B or below (i.e., unranked), these officers constituted a flexible, low-cost workforce for a variety of administrative tasks, often extending beyond their nominal expertise.

Broader society also stood to gain. Popular demand for competent astrological and geomantic advice was high, and by institutionalizing these roles, the government sought to limit the influence of charlatans and untrained practitioners. Members of the local gentry appeared keen to see the position maintained, as its holder could act as a potential advocate for their interests within government channels.Footnote 28 The position’s appeal to multiple constituencies—resident officials, local clients, and the imperial state—helped sustain its longevity through the end of the Qing, preserving its political utility, economic viability, and social relevance.

Yin-yang Schools from Yuan to Qing

Local gazetteers confirm that prefectures and counties across the eighteen provinces of the Qing Empire’s interior employed yin-yang officers. No distinct north–south divide existed in their distribution, at least in administrative terms. This section explores the physical locations where yin-yang officers performed their duties; the following section discusses the processes by which they were selected.

Some yin-yang officers worked within dedicated institutions known as “yin-yang schools” (yinyangxue 陰陽學). These schools were frequently situated alongside “medical schools” (yixue 醫學) within the fortified seats of county and prefectural governments or they shared a single building.

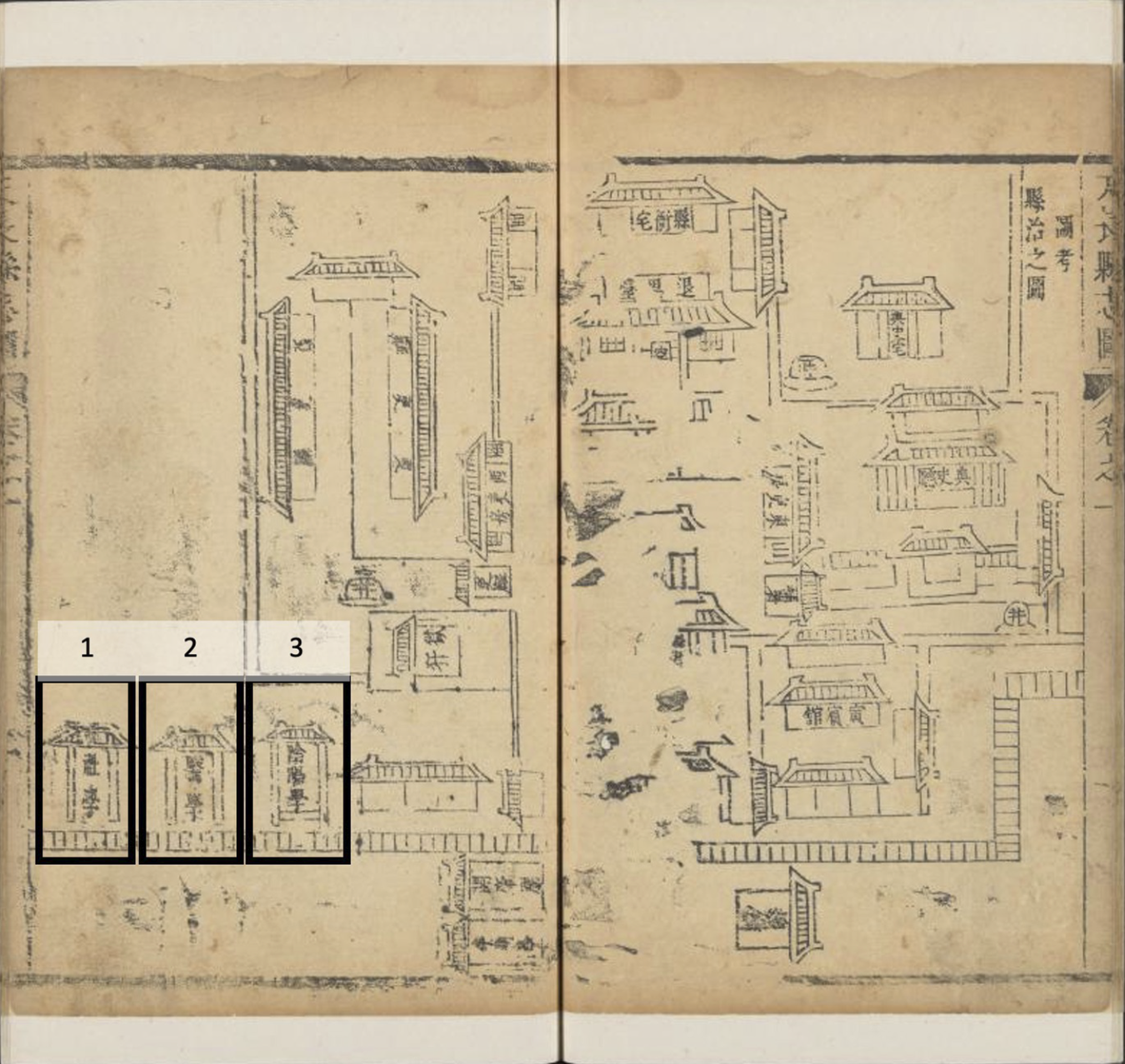

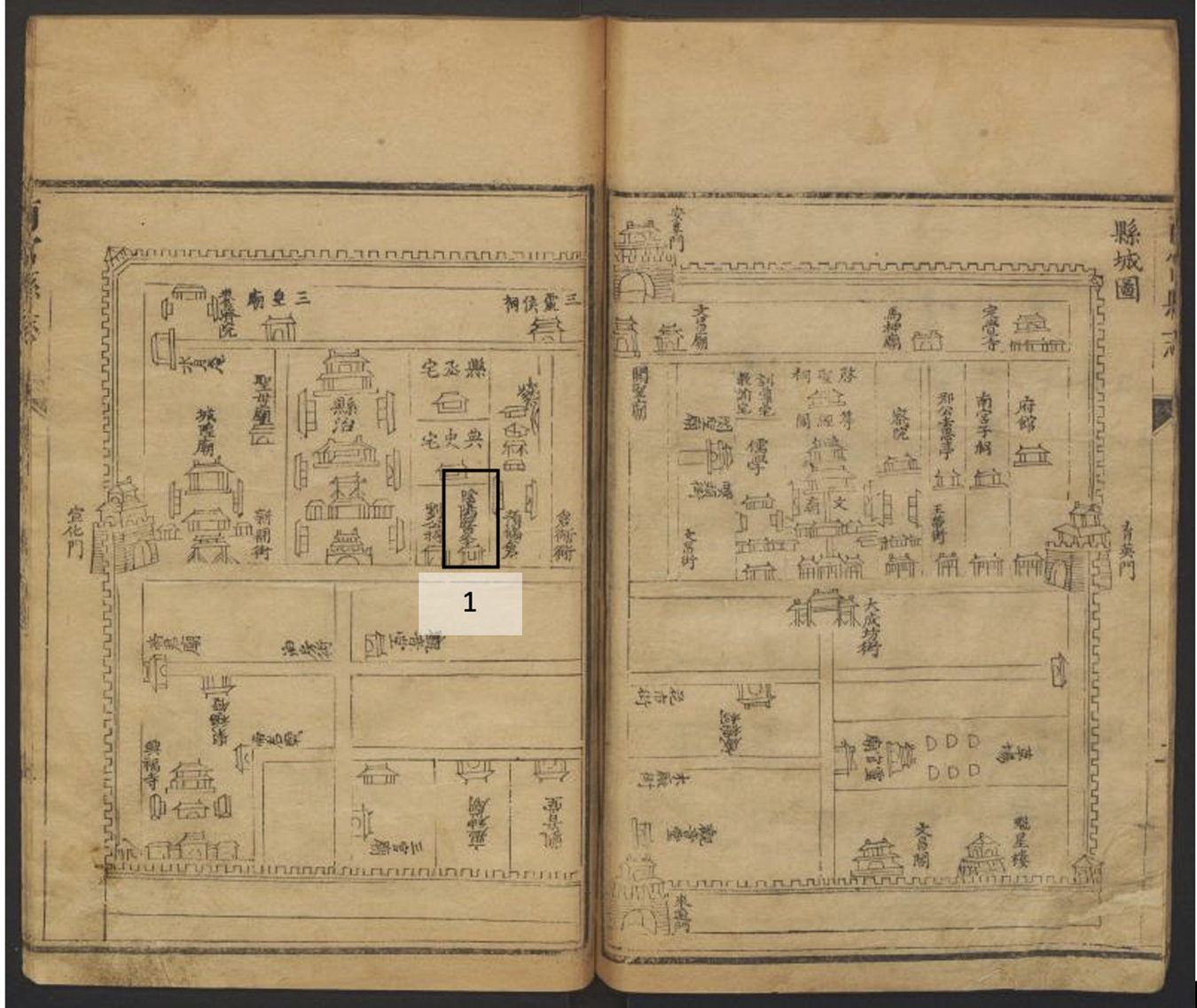

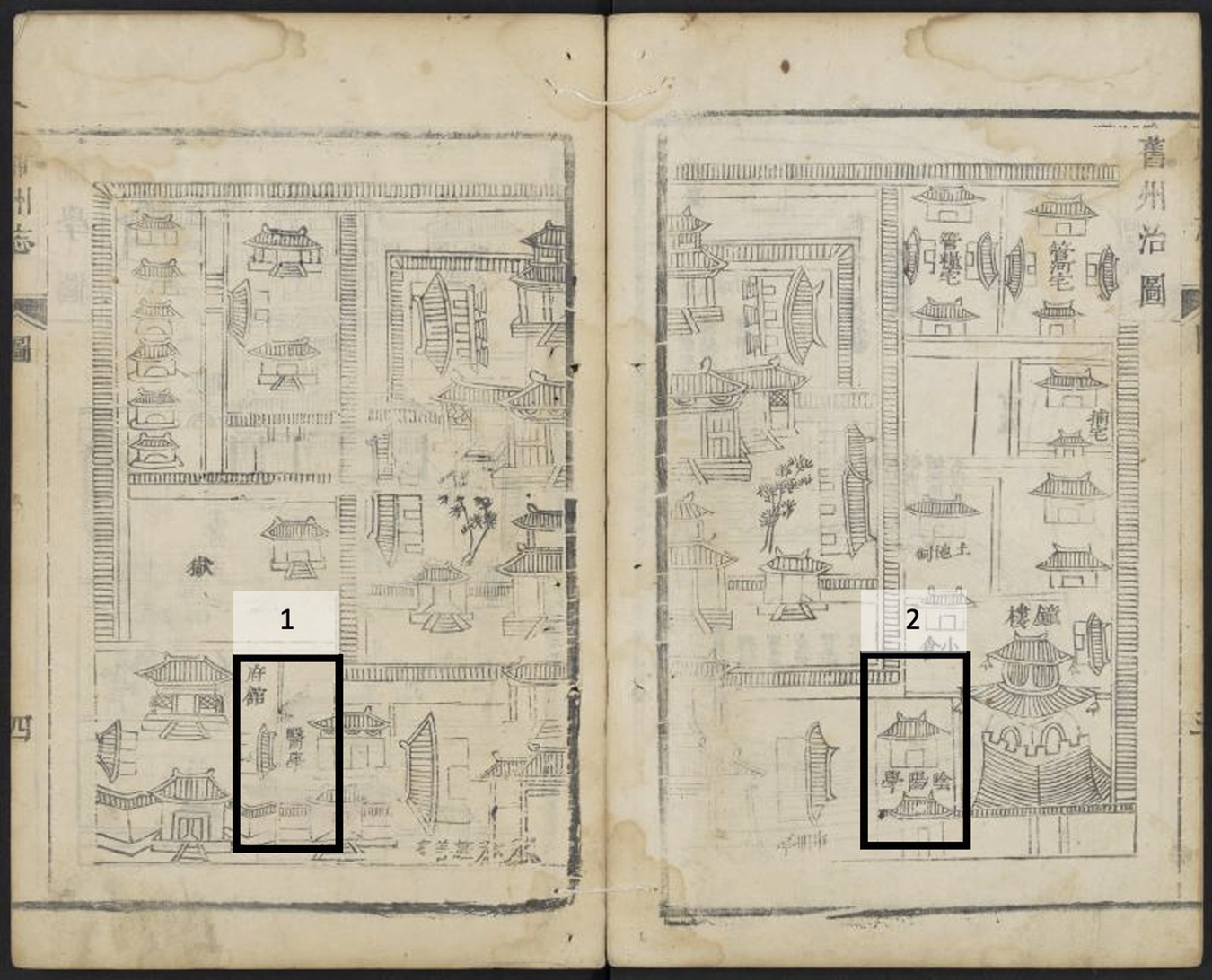

The yin-yang school of Tianchang County in Anhui Province, for example, stood adjacent to both the medical school and the community school, all located within the broader walled compound that also housed the county yamen (Figure 3).Footnote 29 In Sui Sub-Prefecture (Henan Province), the two institutions were also housed separately, with the medical school positioned on one side of the yamen and the yin-yang school on the other (Figure 5). By contrast, in Nangong County (Hebei Province), the medical school and the yin-yang school shared the same building, adjacent to the county yamen (Figure 4). Regardless of their precise location, these institutions were often situated within the walled administrative center near the yamen, underscoring the integration of divinatory expertise into the broader bureaucratic structure.

Figure 3. The community school (1), medical school (2), and yin-yang school (3) of Tianchang County. Image, “Map of the Tianchang County Seat,” from Kangxi Tianchang xian zhi 康熙天長縣志 (1673).

Figure 4. The yin-yang and medical school (1) in a shared building in Nangong County. Image, “Map of the Nangong Walled County Town,” from Kangxi Nangong xian zhi 康熙南宮縣志 (1673).

Figure 5. The medical school (1) and yin-yang school (2) of Sui Sub-Prefecture. Image, “Map of the Old Sub-Prefectural Seat,” from Kangxi Suizhou zhi 康熙睢州志 (1690).

While some regions retained their schools, others saw them vanish by the Qing period. In Sichuan Province, for instance, the widespread destruction accompanying the Ming–Qing transition hastened their decline. Many yamens required extensive reconstruction in the seventeenth century, yet state resources were insufficient to restore medical and yin-yang schools. Consequently, these institutions seldom appeared as distinct entities in Sichuan’s Qing-era gazetteer maps. While their visual absence on maps does not mean they disappeared entirely, many schools apparently were never reestablished.Footnote 30 This trend was not unique to Sichuan: gazetteers from Gansu and Fujian note that while yin-yang schools had existed during the Ming, they had disappeared by the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries—sometimes having been converted into charitable relief homes or even people’s houses.Footnote 31

That said, school reconstruction was not unheard of, particularly in districts where philanthropic generosity supplemented or even supplanted state sponsorship. In some counties, yin-yang schools persisted as physical institutions well into the nineteenth century. In one notable case, an enterprising yin-yang officer in Henan Province took it upon himself to rebuild a long-defunct yin-yang school in 1825, likely financing the project independently.Footnote 32 Other officers responded to the lack of office space with pragmatic workarounds. In Huangyan County, Zhejiang Province, yin-yang and medical officers conducted their work from designated side rooms within the Three Sovereigns Temple rather than maintaining a separate school.Footnote 33

A well-documented case from Qianjiang County in Hubei Province offers insight into how such arrangements may have emerged. In Qianjiang, both the medical school and the yin-yang school were founded in 1384. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, both institutions relocated to new locations at least once. Then, in 1600, the county’s medical school was moved into the physical structure of the yin-yang school. The presiding magistrate justified the decision, declaring: “The principles of yin and yang govern the ordering of heaven and earth, and healers are entrusted with the mandate to sustain human life [with these principles]; together, the Three Cosmic Forces (Heaven, Earth, Human Beings) are rooted in unity” 陰陽天地之紀, 醫者生人之命, 三才本一 . Footnote 34 In addition to this neat ideological packaging, pragmatic financial considerations likely played a role in this consolidation, as housing both schools in a single building reduced construction and maintenance costs.

Following the Manchu conquest in 1644 and a period of devastating regional flooding, a private initiative in Qianjiang supported the relocation and reconstruction of the schools, a project completed by 1693. When a new edition of the county’s gazetteer was published in 1879, the institutions remained intact, still housed within the same structure, adjacent to the local Wenchang Shrine (Figure 6). It is plausible that, much like the case of the Three Sovereigns Temple in Huangyan, the continued existence of yin-yang and medical schools in Qianjiang and other areas was contingent on their association with a prominent local shrine—one that ensured their financial sustainability through public patronage.

Figure 6. Medical school and yin-yang school in a shared building (1) next to the Wenchang Shrine of Qianjiang County. Image “Map of the Qianjiang County Seat,” from Guangxu Qianjiang xian zhi 光緒潛江縣志 (1879).

The reduction of state-sponsored non-Confucian educational institutions in the late imperial period was not limited to the divinatory arts. Angela Leung has demonstrated a similar trend in medical education: while the Song and Yuan states actively supported medical institutions such as medical schools and state-run pharmacies, the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries witnessed their gradual decline as independent entities.Footnote 35 He Bian has observed a related decentralization of pharmaceutical knowledge in the centuries following the completion of the last state-initiated pharmacopeia in 1505.Footnote 36 Reflecting the relative decline in the status of non-Confucian forms of learning in the late imperial period, both medicine and yin-yang-centered divination followed a trajectory from strong institutional support under the Mongols to a more fragmented landscape shaped mainly by literati interest, private patronage, and commercial publishing in the centuries thereafter.

Yet the decline of formal yin-yang schools did not diminish the authority of government-appointed yin-yang officers, who remained active and influential in local administration. By the nineteenth century, the position had become so synonymous with the institution that people in Sichuan referred to the yin-yang officer simply as yinyangxue (lit. “the yin-yang school” 陰陽學), regardless of whether such a building existed.Footnote 37 Such phrasing can be seen in the following legal petition concerning a dispute between a county yin-yang officer and the head of the Daoist Bureau: “In the fifty-first year of the Qianlong reign (1786), the now-deceased Yinyangxue Wang Baiheng exceeded his authority and sought control over spirit mediums under the authority of the Daoists (i.e., the Daoist Assembly)” (乾隆五十一年, 已故陰陽學王白珩越分混掙道教所管巫覡).Footnote 38 What had been an educational institution in Yuan times had, in practice, evolved into a bureaucratic post focused on ritual practice and supervision by the Qing.

Selection, Appointment, and Removal from Office

The process of selecting yin-yang officers varied, though surviving records suggest that many were appointed based on their expertise in divination, astronomy, and calendrical science through a system of “recommendation and promotion” (jianju 薦舉), which bypassed the formal civil service examinations.Footnote 39 Under this system, when a vacancy arose, the county magistrate would nominate a literate man skilled in the divinatory arts for promotion to the post.Footnote 40 The magistrate then forwarded details about the candidate’s name, age, appearance, and native place to the provincial government, which proceeded to petition capital authorities for an investigation and formal approval. Once approved, the yin-yang officer received an official seal bearing his title and office (Figure 7).Footnote 41

Figure 7. Carved wooden seal of a yin-yang officer from Longxi County, Gansu Province (1903). The seal reads, “The seal of Huang Delong, instructor of technique at the yin-yang school of Longxi County, under the jurisdiction of Gongchang Prefecture” (巩昌府屬隴西縣陰陽學訓術黃德隆之鈐記). Image from Wang Kai 汪楷, ed., Longxi jinshi lu, xia 隴西金石錄,下 (Lanzhou: Gansu renmin chubanshe, 2010), 185.

The early Qing government made some changes to the appointment and management of yin-yang officers. In 1674, it streamlined the registration process for provincial candidates by eliminating the need for routine memorials requesting imperial approval for individual appointments. Thereafter, provincial governors communicated nominations directly to the Board of Rites, which verified the candidates and issued zhafu 劄付 (official registration notices) authorizing their appointment.Footnote 42 Nearly a century later, in 1764, the government further stipulated that the Board of Rites was to compile an annual roster of all registered yin-yang, medical, Buddhist, and Daoist personnel—both in the capital and the provinces—and submit it to the Board of Personnel for archival purposes.Footnote 43 This adjustment reflected the central government’s ongoing efforts to monitor and systematize the management of technical and religious officials across the provinces.

Through the end of the dynasty in 1912, provincial officials occasionally reported the appointments or commendable deeds of yin-yang officers to the capital. However, communication between the provinces and central authorities specifically concerning yin-yang officers remained irregular. The First Historical Archives in Beijing holds some official correspondence related to the appointment and commendation of county- and prefectural-level yin-yang officers, but such records are relatively scarce.Footnote 44 It is also likely that some vacancies remained unfilled for extended periods—a pattern Vincent Goossaert has noted in the case of county-level Daoist head positions.Footnote 45 Still, further references to these technical and religious officials might be found buried in the routine memorials of provincial governors or the summary routine memorials of the Board of Personnel concerning the triannual “Grand Accounting” or “Metropolitan Inspection” (daji 大計) performance reviews of local officials.Footnote 46

This lack of sustained oversight was not only visible in central archives but also acknowledged in county-level records. In 1885, Nanbu County received a notice from the Board of Rites, relayed through the Sichuan provincial government, outlining three major problems concerning yin-yang officers, medical officers, and the appointed leaders of Buddhist and Daoist Assemblies. A core passage of the notice reads as follows:

There are cases where an officer died of illness, yet his descendants continue to serve using his old registration notice (jiuzha 舊劄).

有本職病故, 其子嗣又將舊劄任事者;

Additionally, some officers had their registration records rejected by the Provincial Administration Commission (buzhengshi si 布政使司) due to inconsistencies, but [county authorities] concealed the matter and failed to report it.

又有因冊結不符, 由司駁還, 遂隱匿不報者;

There were also cases in which county authorities approved appointments, [but local officials] only issued a county-level certificate (xianzhao 縣照) and did not submit the required registry documents for retroactive confirmation [until the cases were exposed].Footnote 47

亦有由縣批准, 僅給縣照, 未具冊結申送請補者。

The implications of these problems were troubling. The inheritance of posts within families without formal registration signaled a breakdown in the government’s earlier efforts to maintain accurate records of officeholders. While Qing regulations did not prohibit families from transmitting technical knowledge and skills across generations, sons and grandsons of officers were still required to be formally registered with central authorities. In practice, however, provincial officials struggled to effectively monitor the many counties under their jurisdiction. The 1885 notice reflects a growing awareness among senior officials that they had little knowledge of how these minor, county-level posts were being filled. Even more troubling was the emerging suspicion that provincial authorities were just as uninformed.

This uncertainty invites a deeper question about the qualifications of those who held these roles. While there is little evidence of a standardized curriculum for training officers in the Qing, earlier periods had established such training structures.Footnote 48 At the very least, yin-yang officers had to be familiar with the imperial calendar and the dynasty’s authoritative text on divination, Imperially Endorsed Treatise on Harmonizing Times and Distinguishing Directions (Qinding Xieji bianfang shu 欽定協紀辨方書). This text prescribed the precise times and locations for imperial cult rituals throughout the year. Considering the importance of calendrical expertise among yin-yang officers, one assumes that this treatise was important in officer training.Footnote 49

Some officers also wrote, compiled, and circulated records of their tenures or even their own practical guidebooks. The gazetteer of Tai Sub-Prefecture in Jiangsu Province notes the inclusion of a text titled Official Reports of the Sub-Prefecture’s Yin-yang Officer (Benzhou Yinyangxue Shenwen 本州陰陽學申文) as one of the listed sources consulted during its 1728 revision. The gazetteer also references similar collections for the Buddhist and Daoist Assemblies, implying that Tai Sub-Prefecture maintained records related to these offices for future generations.Footnote 50 Similarly, a Sichuan family of yin-yang officers in the nineteenth century composed a detailed manual on the proper uses of the geomantic compass, entitled The Wang Family Comprehensive Explanation of the Geomantic Compass (Wang shi luojing toujie 王氏羅經透解).Footnote 51 Such texts likely served as instructional material for divinatory apprentices.

The “Wang family” compass guide points to another key feature of yin-yang officers, already alluded to above: in some districts, the position was de facto hereditary. A 1799 gazetteer of Xi County, Henan Province, records, for example, that seven generations of the Meng family had occupied the yin-yang officer post for a total of more than 150 years.Footnote 52 The medical officer of Xi County also appears to have been a largely inherited post. The 1799 gazetteer recorded the names of eight individuals who had served as medical officers since the beginning of the dynasty, five of them bearing the surname He 何.Footnote 53 In Xi County at least, the practice of hereditary appointments persisted well into the Qing, although it was not necessarily a universal norm across the empire.Footnote 54

Whether formally appointed or inheriting their positions, yin-yang officers appear to have remained in office significantly longer than their higher-ranking counterparts. In Changtai County, Fujian Province, for example, four yin-yang officers served between 1648 and 1687, with an average tenure of approximately ten years.Footnote 55 The county’s records also include sixteen Ming-era yin-yang officers who served from 1435 to 1644, averaging roughly thirteen years in office—assuming the list is reasonably comprehensive. By contrast, during the same thirty-nine-year period (1648–1687) in the early Qing, the county saw nine magistrates, whose average tenure was just over four years.Footnote 56

Assessing the accuracy of gazetteer data of this kind is no simple task. It is almost certain that more than nine magistrates, particularly temporary or acting ones, served in Changtai County over those thirty-nine years, and it is quite likely that more than four yin-yang officers held the post during that time as well. The disparity in number may simply reflect poorer record-keeping for yin-yang officers compared to magistrates. The practice of inheriting posts further obscured the archival record, as such successions often occurred informally and off the books. Yet vernacular literature lends credence to the idea that yin-yang officers were more accessible than higher ranking officials. In the Ming novel The Plum in the Golden Vase, for instance, yin-yang officers are identified by family name (e.g., “Yin-yang Master Xu” (陰陽徐先生)), suggesting that local communities knew who these individuals were and where to find them. While rural residents of Xi County around 1800 may not have known the surname of their acting magistrate, one suspects they knew their yin-yang officer was surnamed Meng—just as it had been for the past 150 years.

With such apparently long tenures, one must ask whether yin-yang officers were ever removed for poor performance. Some were. Because ambitious county magistrates might be attempted to “clean house” at the start of their tenures, administrative handbooks such as Essential Tables of Regulations for Convenient Consultation (Zeli tuyao bianlan 則例圖要便覽; 1790) stressed that, “In evaluating assistant, miscellaneous, and teaching personnel, arbitrary dismissal is not permitted” (考核佐、雜、教職, 不得任意填汰).Footnote 57 Lower-ranking officials were to remain in office if they satisfactorily performed their jobs. Some did not meet that bar: one infamous yin-yang officer in the aforementioned novel The Plum in the Golden Vase was indeed removed “for cause.”Footnote 58 Yet, apart from the occasional case of proven misconduct, it appears that an officer could remain in the position for extended periods of time—a conclusion supported by the fact that central government complained that many people illicitly inherited the post after their kin died in office (see above).Footnote 59

Despite the institutional stability of the position, its role in facilitating upward mobility is unclear. Few, if any, Qing-era yin-yang officers advanced to more prominent roles within the bureaucracy, and regulations explicitly forbid the transfer of the technical and religious officials to positions other than their given specialty.Footnote 60 As such, the position did not function as a steppingstone to higher office. However, some elite officials did emerge from families with a record of serving in such roles. One notable example is the Ming official Liu Huan 劉澣 (1400–1459), who earned his jinshi 進士 degree in 1449; his elder brother, Zicong 自聰, served as the yin-yang officer of Gong County in Sichuan Province.Footnote 61

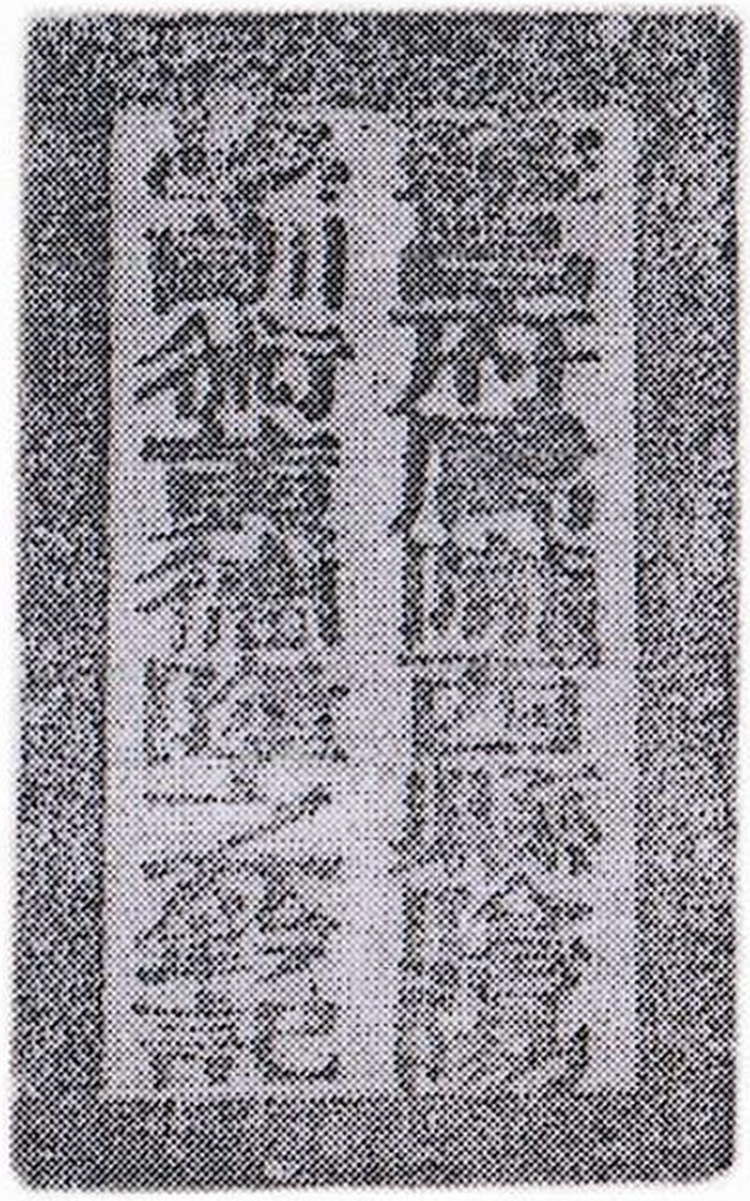

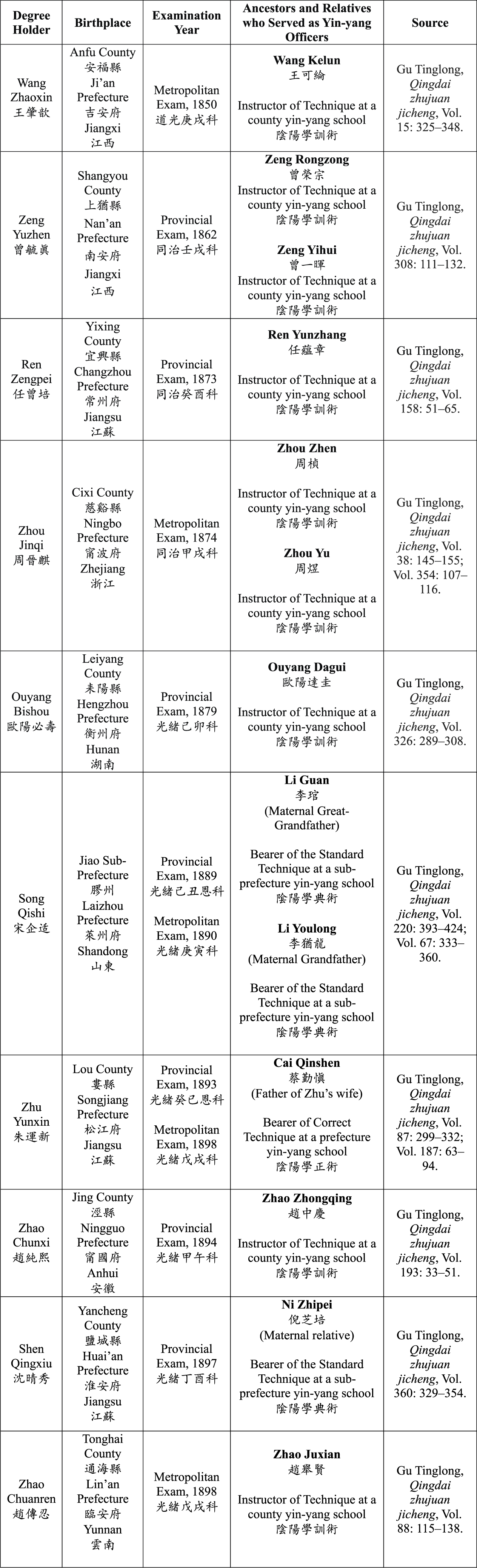

Similar records survive from the Qing, as illustrated in Figures 8 and 9, which present a sample of thirteen yin-yang officers mentioned in the genealogical biographies of provincial and metropolitan examination candidates between 1850 and 1898. Across the entire collection of genealogical records, dozens of yin-yang and medical officers appear, as do a few Daoist officials, though the latter seems to have been rarer.Footnote 62 While the position of yin-yang officer rarely propelled individuals into illustrious careers, it was usually held by members of established families that, over time, might produce candidates for higher academic or bureaucratic achievement.Footnote 63

Figure 8. Selected yin-yang officers in the Genealogical Biographies of Provincial and Metropolitan Examination Candidates (1850–1898).

Figure 9. Metropolitan examination “Vermillion Scroll” genealogical record of Zhao Chuanren (Second Class jinshi, Ranked 98, Class of 1898). Zhao’s patrilineal ancestor who served as a county yin-yang officer is listed in the top-center of the two-part page. Image from Gu Tinglong, Qingdai zhujuan jicheng, 88:115.

While this claim remains speculative due to limited data, the very appearance of yin-yang officers in these records is nonetheless significant.Footnote 64 Their inclusion suggests that such positions held a degree of local prestige enough for degree candidates to feature them in public-facing family histories. Consider the many conspicuous absences in these records: references to ancestral merchants, farmers, artisans, secretaries, clerks, runners, and monks are largely, or entirely, missing. Yin-yang Officers were officials, and that fact brought some status to individuals and their families. Further investigation will likely reveal additional examples beyond those listed in Figure 8.Footnote 65

In summary, unlike county magistrates, who were subject to frequent rotations and a strict application of the rule of avoidance, yin-yang officers were appointed locally and served in office with all of the advantages (i.e., local knowledge and kinship networks) and all of the disadvantages (i.e., limited room for promotion through office-holding) that accompanied their home-grown identities and distinctive administrative status. Whether formally appointed through recommendation and registration, or informally through familial succession, yin-yang officers remained integral fixtures of county and prefectural administration—both because higher-ranking officials relied on their specialized expertise in divination, geomancy, and calendrical calculation, and because the people did too.

Roles and Responsibilities

Among the multiple roles and responsibilities of yin-yang officers was overseeing the “Grand Ceremony for Welcoming the Spring Solar Term” (Yingchun dadian 迎春大典), a major public ritual held by local governments a few around New Year. At the heart of this celebration stood the Spring Ox (chunniu 春牛), crafted from clay and tree branches, and the ox-driving Harvest God (mangshen 芒神). The two divine effigies represented spring and fertility, respectively. The ceremony featured a procession of religious authorities parading to the county seat from the east, accompanied by theatrical performances of opera and dance.Footnote 66 These festivities drew large crowds eager to witness the spectacle of the county magistrates and his subordinates performing the symbolic act of beating the Spring Ox to mark the start of Spring.Footnote 67

A preserved government notice from Nanbu County in Sichuan Province provides insight into the administration of the ritual in 1887. The notice outlines instructions given to the yin-yang officer responsible for overseeing the event:

As the Spring Solar Term is set to begin on the twelfth day of the first month in the thirteenth year of the Guangxu reign (GX13.1.12 /February 4, 1887), the government will conduct the Grand Ceremony for Welcoming the Spring Solar Term the day before.

照得光緒十三年正月十二日立春, 先於十一日舉行迎春大典。

All required ceremonial elements—including the Spring Ox, the Harvest God, ritual attendants, performers in five-colored ceremonial armor, and assigned laborers—must be prepared without delay and in strict accordance with regulations.

所有應用春牛、芒神及扮演儀從、五色鎧靠衣服、人夫等項,合行飭辦。

This notice is issued to the yin-yang officer to review and oversee arrangements. The Officer in turn shall inform the resident clerics and spirit mediums (i.e., ritual specialists under his jurisdiction) to follow past precedents and ensure that all preparations are made in an orderly and complete manner; no errors shall be permitted as the time [of the festival] approaches.Footnote 68

為此牌仰陰陽學查照來牌事理, 即傳塵居、巫教術師人等, 遵照向例逐一預備齊全, 毋得臨期有誤。

The notice above suggests that the officer was responsible for managing the intricate logistics of the ceremony. On the day of the festivities, the county magistrate was expected to arrive, find everything already in place, and ceremonially strike the clay ox. In short, it was the yin-yang officer’s job to ensure that the event unfolded smoothly, and that the magistrate appeared dignified and competent before the assembled public. Unlike most recently arrived magistrates, the officer understood what the local crowd expected in terms of regional flair and customary spectacle.

The specific designation of the yin-yang officer to oversee the “Grand Ceremony for Welcoming the Spring Solar Term”—a choice that becomes clear when considering the calendrical foundations of the ritual.Footnote 69 The “Arrival of the Spring” (lichun 立春) marks the first of the twenty-four solar terms in the traditional Chinese calendar and occurs when the sun reaches a celestial longitude of 315 degrees. It occurs around the same time—but is distinct—from the Lunar New Year: “Arrival of the Spring” is determined by the solar cycle, whereas the New Year follows the lunar cycle and falls on the first day of the first lunar month. Accordingly, the two dates typically do not coincide. In the example from 1887, the Spring Solar Term arrived eleven days after the start of the New Year.

Confusion may arise because of terminological changes from Qing times to the present. Today, the Lunar New Year is widely referred to as “Spring Festival” (chunjie 春節), but this terminology only became standardized in the twentieth century. Traditionally, the term “Spring Festival” referred more specifically to the beginning of the Spring Solar Term, while names like zhengdan 正旦 or even yuandan 元旦 were used to mark the first day of the lunar year on the imperial calendar. After the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, the term yuandan was repurposed to refer to January 1 in the newly adopted Gregorian calendar. This left the term “Spring Festival” to refer exclusively to the beginning of the Lunar New Year, a meaning it has retained since.

This older associations between “Spring Festival” and the Spring Solar Term also explain its prominence in Qing state ritual practice. Ritual instructions for Welcoming the Spring Solar Term were meticulously recorded in the Imperially Endorsed Treatise on Harmonizing Times and Distinguishing Directions, specifying when preparations should begin after the Winter Solstice and the correct method for crafting the “Spring Ox.”Footnote 70 Yin-yang officers did not personally calculate the solar term’s arrival—that responsibility fell to officials at the Astronomical Bureau (Qintian jian 欽天監) in Beijing, who spent months meticulously compiling the annual calendar for ceremonial promulgation at the Imperial Palace’s Meridian Gate on the first day of the tenth month.Footnote 71

Rather, yin-yang officers played vital roles as “masters of ceremony” in counties and prefectures across the empire, ensuring that the festival marking the beginning of the Spring Solar Term, along with other observances, conformed to imperial ritual standards. A strong reputation for managing complex ritual ceremonies could make a yin-yang officer’s career in rural society—and many officers began their training at a young age. As David Johnson has shown in his study of temple festivals in North China, the ritual texts for such events were often passed down through generations within families associated with the yin-yang profession.Footnote 72

The government notice from Nanbu County above highlights the yin-yang officer’s supervisory authority over clerics and spirit mediums, and, in practice officers frequently collaborated with Buddhist monks and Daoist priests for large public rituals. One suspects such arrangements were intentional: by determining the timing, location, and orientation of key calendrical rites, the imperial state effectively distributed ritual authority across a diverse group of specialists—including spirit mediums, Daoists, Buddhists, and geomancers—thereby preventing any one tradition from dominating the local performance of the state cult and the broader imperial religious field. This delegation of authority occasionally led to conflict, as seen in the repeated litigation between the yin-yang officer Wang Baiheng and the head of the Daoist Assembly over control of spirit mediums in Nanbu County during ceremonies such as “Welcoming the Spring Solar Term.” Yet in principle, each type of ritual expert was entrusted with a distinct body of knowledge, and all were considered indispensable to the broader ceremonial framework of state-sponsored sacrifices and seasonal observances.

Yin-yang officers also played a key role in helping oversee rescue rituals for solar and lunar eclipses. Eclipses were widely regarded as ominous events with potential consequences for the dynasty and the country, prompting the government to mandate rituals aimed at “rescuing” the sun or moon during these celestial occurrences. “All civil and military officials stationed in the capital” (zai jing wenwu ge guan 在京文武各官) were required to attend these rituals in the open-air courtyard of the Board of Rites, while all officials in the provinces were to hold and attend them in local yamens.Footnote 73

Eclipses occur frequently. Each year, at least two lunar eclipses are visible from any location on the night side of the Earth. During the same period, two to five solar eclipses take place globally, though each is visible only along a narrow path. As a result, not every solar or lunar eclipse could be observed in China. Qing astronomers recorded lunar eclipses more regularly than solar ones, as they were more reliably visible from Beijing. Solar eclipses, by contrast, were more difficult to predict through calculation, since the Moon’s shadow covers only a small portion of the Earth during the event. Perceived as rarer and more ominous, solar eclipses had for centuries carried greater symbolic weight for a ruling dynasty.

While scholars have devoted extensive attention to the role of Jesuit astronomers in Ming and Qing China, less has been written about the widespread local ritual performances that were made possible by astronomical calculations conducted in the capital.Footnote 74 Although eclipse rescue rituals have deep roots in imperial tradition, their formal integration into local government structures began only in the early Ming. The Qing state built on this precedent, refining the reporting system by issuing detailed eclipse calculations from the capital—specifying the start and end times for each province—and mandating that rescue rituals be performed in every county. Whether by deliberate design or unintended consequence, these policies expanded the institutional role of local yin-yang officers, who were tasked alongside the other local specialists with organizing and overseeing the ceremonies. As with other calendrical rites, such as the Spring Solar Term ceremony, these officers did not compute the timing of eclipses themselves but instead presided over the required rituals at government yamens, under the authority of the local prefect or magistrate.

According to imperial regulations, all provinces were to be notified in advance of upcoming eclipses. However, after a 1749 adjustment in policy, only those provinces where the eclipse would be visibly observable were required to perform the associated ritual safeguarding.Footnote 75 In practice, not all the eclipses that the Board of Rites reported to Sichuan were visible from the province. Nevertheless, the surviving archival evidence from Nanbu County suggests that the local government made ritual preparations at the prescribed times regardless of visibility, reflecting both bureaucratic diligence and cosmological caution.Footnote 76

Upon receiving an eclipse notice from the provincial government, the county magistrate summoned the County Security Officer, the County Yamen Constable (a non-official), the yin-yang officer, the Registry Overseer of the Office of Buddhist Discipline, and the Registry Overseer of the Daoist Supervision Office to make the necessary preparations for the event. The routine presence of both the County Security Officer and the Constable at these events suggest that public security was a concern for authorities during the eclipse. On the appointed day, the yin-yang officer and other attendants arranged a ritual table with two large candlesticks in the county yamen’s courtyard. As the eclipse approached, the presiding official, usually the county magistrate, would announce its imminent arrival. When the eclipse began, the candles were lit, and the county magistrate entered the space, incense in hand, to perform obeisance before the ritual table, executing three kneelings and nine prostrations. At that moment, ritual attendants beat drums and sounded gongs, creating a cacophony of sound that continued until the eclipse had passed.Footnote 77

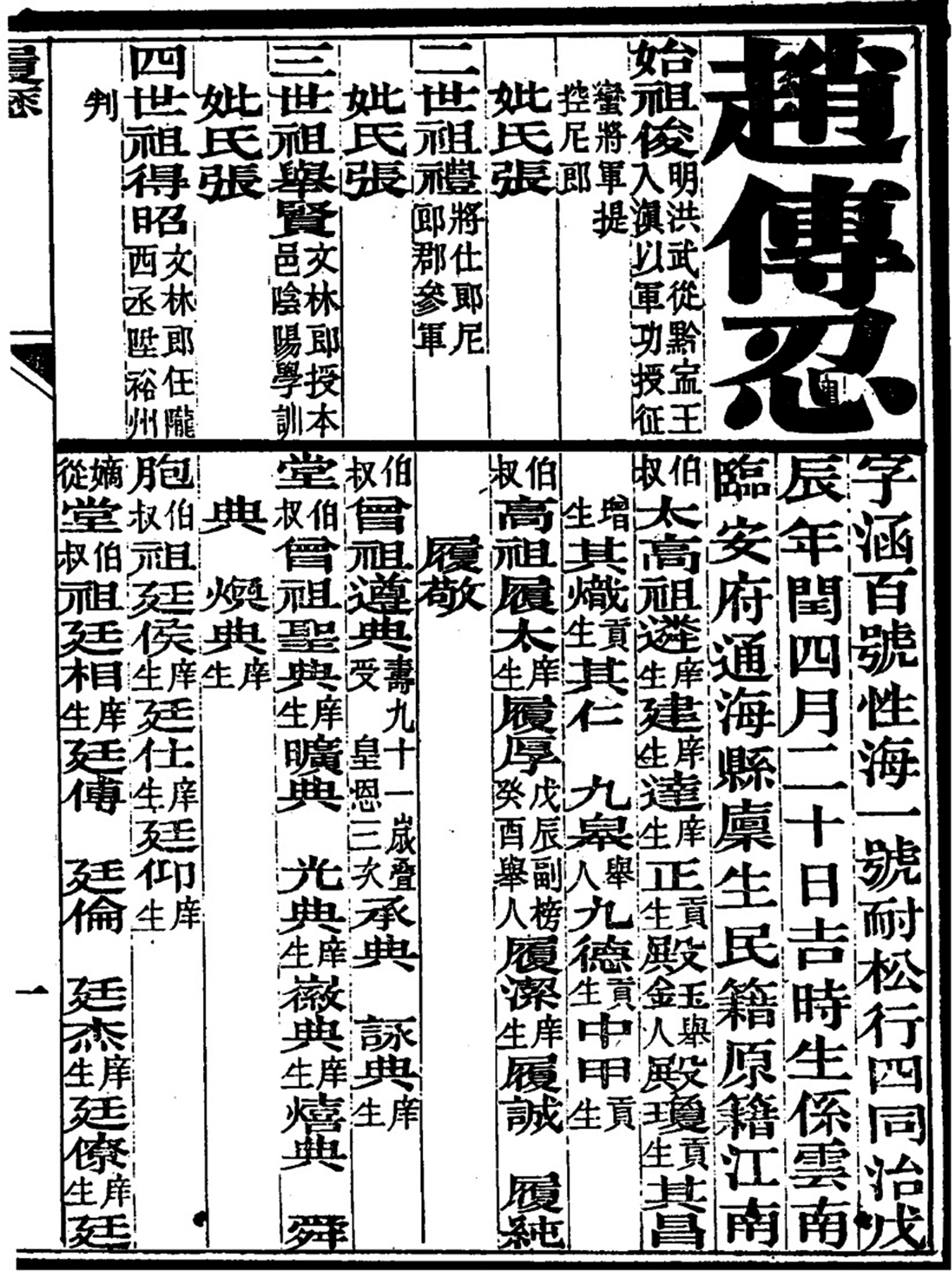

Under the Qing lunisolar calendar, solar eclipses invariably occurred on or near the first day of the month, coinciding with the new moon—the only phase during which a solar eclipse is astronomically possible. Lunar eclipses, by contrast, took place around the full moon, which in the Qing calendrical system consistently fell in the middle of the month. Between 1890 and 1911, Nanbu County received notifications of at least nine impending solar eclipses and over a dozen lunar eclipses, typically a month or two in advance of the event.Footnote 78 The Nanbu Archive is most complete for the latter years of the dynasty, so caution must be exercised when gauging the regularity of the central government’s eclipse notifications to the county.Footnote 79 However, as Figure 10 demonstrates, the administrative pipeline linking the Astronomical Bureau to provincial officials regarding eclipses remained operational until the very end of the Qing.Footnote 80

Figure 10. Solar eclipses calculated by the Qing Astronomical Bureau and reported to Sichuan Province between 1890 and 1911. Note: GX denotes “Guangxu” Era (1875–1909) and XT denotes “Xuantong” Era (1909–1912)

Western observers in the nineteenth century often viewed Qing eclipse rescue rituals with skepticism, questioning the imperial government’s attention to such celestial events. The common explanation in the nineteenth century highlighted the longstanding Chinese association between eclipses and cosmic inauspiciousness.Footnote 81 This explanation remains the most cited in works of comparative global astrology.Footnote 82 And for good reason: it is not wrong.

However, the bureaucratic structure of Qing local administration suggests another motive. By 1800, in addition to the officials stationed at the Astronomical Bureau in Beijing, the imperial government employed, in theory if not practice, 185 to 200 prefectural yin-yang officers, 200 sub-prefectural yin-yang officers and over 1,300 county yin-yang officers to oversee these rituals across the empire.Footnote 83 In an empire known for its bureaucracy being increasingly stretched thin on the ground by the turn of the nineteenth century, more than 1,500 yin-yang officers across China held official duties related to eclipse management. If Daoist and Buddhist Assembly Heads are included, that number would, in theory, amount to over 4,000 officials across the empire. This visible and entrenched bureaucratic network demonstrated remarkable institutional resilience, persisting through the final year of the Qing’s existence. That bureaucracy, spanning from the metropole to the northwestern and southwestern peripheries, reinforced the reality and public perception of the imperial state’s attunement with the ways of the cosmos and its control over the people tasked to interpret its signs.

Beyond their involvement in spring ceremonies and eclipse rituals, yin-yang officers played a multifaceted role in local governance. Further insights into their administrative duties can be found in Huang Liuhong’s Complete Book of Happiness and Benevolence, a practical handbook for newly appointed magistrates. On the magistrate’s first day in office, they were tasked with announcing the time (baoshi 報時) as the new official ascended to his seat in the yamen’s central hall.Footnote 84 Presumably, this method of formally announcing the magistrate’s arrival also applied during the eclipse rituals described above.

Huang’s handbook also includes a copy of official instructions for yin-yang officers regarding the management of a county yamen’s reception hall.Footnote 85 Officers were to maintain its cleanliness and proper arrangement daily, prevent the entry of unauthorized individuals, and respectfully invite honored guests to be seated while waiting. If the magistrate was engaged in official duties outside the yamen, the yin-yang officer was expected to politely inform the visitor of the situation and record the visit in the guest register, in order to notify the official upon his return. As the local custodians of the imperial calendar, yin-yang officers also served as official timekeepers, and in some counties during the Qing, they played an essential role in helping busy magistrates manage the pacing and scheduling of their daily affairs.

While carrying out these routine functions, yin-yang officers were also embedded in the daily lives of rural communities. Stele inscriptions invoke officers as supervising the construction of schools and other large structures.Footnote 86 More than one officer was credited with improving local irrigation systems through his expertise in fengshui. In Guanyang County, Guangxi Province, for example, the county’s yin-yang officer petitioned the yamen to construct forty-four embankments along a river, facilitating better irrigation for local farmland.Footnote 87 Given that such projects often sparked disputes and even lawsuits over fengshui among competing interest groups, it is likely that yin-yang officers also played a role in mediating conflicts over waterways, reinforcing their utility in local governance.Footnote 88

In addition to their contributions to public works and civil administration, a central duty of yin-yang officers was the suppression of heterodox beliefs. Alongside his Buddhist, Daoist, and Medical counterparts, yin-yang officers were responsible for monitoring and regulating religious practices deemed subversive by the Qing state. Their widespread distribution at the sub-provincial level also allowed prefects and magistrates to assign blame in cases of local unrest. The imperial government’s primary concern was not simply the heterodox doctrines themselves, but also the individuals engaged in these practices—figures such as itinerant monks, fraudulent diviners, and Daoist sorcerers, whose activities were viewed as potential threats to social stability.

For instance, in 1731, Magistrate Shen of Heyuan County, Guangdong Province, sought to reassert state control by reinstating two long-defunct local offices: the head monk of the Buddhist Assembly and the yin-yang officer.Footnote 89 To oversee the county’s Buddhist community, he appointed a monk from Guifeng Hermitage as the head monk, granting him authority over all clergy in the district, including itinerant clerics arriving from outside the county. Meanwhile, in the same year Shen selected a man named Xie Zonghan as the yin-yang officer, tasking him with the regular inspection of astrologers, diviners, and spirit mediums. The county gazetteer notes that a medical school had existed locally at some point in the past, but that position apparently was not reinstated in 1731.

As previously mentioned, county-level vacancies in yin-yang, medical, Daoist, and Buddhist offices were not uncommon, and in some districts, periods of relative occupational inertia were suddenly broken in the wake of social unrest, an imperial directive from above—or a combination of both. In Heyuan County, the concurrent appointment of both Buddhist and yin-yang positions in the same year following a long dormant stretch suggests that Shen’s actions aligned with a broader imperial effort to strengthen religious oversight in the 1720s and 1730s. The magistrate’s appointments likely reflected the Qing court’s heightened concern over heterodox sects, particularly in the wake of the Yongzheng Emperor’s 1724 edict banning Christian proselytization in the provinces. Other counties across China received similar notices of increased religious oversight around this time.Footnote 90 It is little surprise, then, that in the 1840s, yin-yang officers in Sichuan were called upon to assist the leaders of the Buddhist and Daoist Assemblies in locating and arresting the French Catholic Bishop François-Alexis Rameaux.Footnote 91 The choice was a logical one—after all, who among local officials on staff at the county was better suited to track down and detain rogue clerics?

The cases above illustrate a broader bureaucratic phenomenon. While administrative dormancy and competing priorities could lead to vacancies in local technical and religious posts, it is unlikely that all such positions within a county or prefecture remained unfilled for long periods. In practice, when one or more of these posts were vacant, a Daoist, Buddhist, yin-yang, or medical officer might temporarily assume the duties of the others. The range of responsibilities attached to these roles in the Qing (e.g., Welcoming the Spring Solar Term, conducting eclipse rituals) made it impractical for all of them to be left unstaffed for extended durations. Although Qing administrative law mandated strict functional boundaries among these specialists, it seems likely that a variety of local pressures rendered office-sharing an occasional feature of county-level governance.Footnote 92

Concluding Remarks: Inside the Qing Lower Bureaucracy

The role of yin-yang officers invites a reevaluation of how the Qing state operated at the local level, how official posts evolved over time, and what kinds of knowledge the imperial bureaucracy sought to harness and regulate. The concluding remarks that follow begin by examining the place of religion—broadly defined—within the late imperial Chinese state, before turning to the specific implications of yin-yang officers in Qing local administration.

While imperfect terms for describing historical Chinese contexts, “secular” and “religious” have been used in scholarship to highlight important structural and ideological features of the imperial era.Footnote 93 Yet the relationship between these realms was often more ambiguous than the binary suggests. In his influential study of Buddhist patronage among the late Ming gentry, Timothy Brook argues that the state maintained a “state-enforced separation of clerical and secular worlds.”Footnote 94 Brook’s formulation captures an important facet of late imperial statecraft: the Qing, like the Ming before it, sought to curtail the autonomous power of religious institutions, viewing them as potential threats to imperial authority.

However, the ubiquitous presence of yin-yang officers alongside medical officers and Buddhist and Daoist Registry Overseers complicates the notion that the imperial government drew a clear line between the secular and the religious. At the county and prefectural levels, a quarter or more of all official posts were assigned to individuals responsible for religious, ritual, or healing duties. While these roles were not always central to administrative strategy—and some districts saw them neglected for stretches of time—they persisted for good reason. People across society drew on their services: for cures, construction, funerals, opera performances, temple sacrifices, and more. As Jeffrey Snyder-Reinke has shown, even high-ranking officials engaged in religious practices such as rainmaking.Footnote 95 At all levels of the Qing bureaucracy, from the highest metropolitan officials (and the emperor) to lowly yin-yang officers, religious rituals were at the heart of Chinese administrative practices.Footnote 96 Late imperial China, and particularly the Qing, functioned in many ways as a “religious state.”Footnote 97

Rather than separating the secular realm from the religious, the Qing state contained heresy by defining orthodoxy, and it controlled swindlers by recognizing legitimate masters. Through institutionalizing the positions described above, the imperial government sought to distinguish legitimate practitioners of applied cosmology, medicine, and religion from the multitude of charlatans and disreputable clerics. Their presence throughout Qing local administration signified that, amid the vast landscape of “deluded beliefs and deceptions,” there existed legitimate and authentic authorities on medicine, fengshui, Buddhism, and Daoism—genuine disciplines and teachings worthy of official recognition.

The Qing government’s recognition of these ritual, healing, religious practices through the official appointment of recognized specialists bridged the gap between the imperial state and the people. Frequently outlasting successive county magistrates, yin-yang officers provided an element of institutional continuity, serving as conduits of knowledge and administration among officials, gentry, and commoners—a dynamic that helps explain the persistence of their position across centuries. These officers not only conferred cultural authority upon unlicensed ritual specialists but also acted as vital intermediaries between the imperial court and local administration. The annual performance of state-mandated rituals strengthened both the hierarchical relationship between the center and periphery as well as the intricate communication networks linking Beijing to distant county-level officials. This network was particularly evident in how yin-yang officers connected the Astronomical Bureau in the capital with remote regions in western China through the management of eclipses. Through these officials and other minor functionaries, the Qing state had the capacity to extend its presence beyond the county seat. The imperial state may often have been unwilling or unable to do so, but it could and sometimes did penetrate deeply into the countryside.

Accordingly, the presence of yin-yang, medical, Buddhist, and Daoist officials in counties and prefectures across China challenges the common perception that the county magistrate marked the outermost boundary of state authority in rural society. T’ung-tsu Ch’u’s classic study of Qing local governance emphasizes the “insignificance of subordinate officials,” whom he viewed as “few in number,” making “the magistrate a one-man government, overburdened with all kinds of administration, and with little or no assistance from his official subordinates.”Footnote 98 Ch’u’s influential thesis shaped subsequent scholarship for decades after its publication. Notably, historians like Madeleine Zelin and Bradley Reed refined Ch’u’s portrait by distinguishing between the formal administrative structures he emphasized and the informal practices he overlooked, including off-the-books financing, irregular taxation, and extra-legal governance.Footnote 99 Building on those revisions, this article suggests that Ch’u may have understated the importance of what he called “subordinate officials” and somewhat overstated the authority of the average magistrate. While county magistrates undoubtedly played vital symbolic and practical roles in mediating between state and society, how many people in Qing China ever interacted with one? Neither native to nor embedded in the regions they governed, magistrates were itinerant appointees, temporarily inserted into entrenched local structures and often serving brief tenures of a year or less.Footnote 100 They were outsiders who depended on insiders to implement and sustain effective governance.

This article shifts our focus to the insiders who looked up at the Qing bureaucracy from its bottom. Beneath the ranks of examination-qualified governors, circuit intendants, prefects, and magistrates existed another tier of local officials ranked 9B or unranked.Footnote 101 These technical and religious specialists numbered in the thousands across the empire; in Nanbu, they constituted a third of the county’s official staff in any given year. They embodied domains of expertise that shaped the everyday lives of Qing subjects, even if lacking the cultural prestige of elite Neo-Confucian learning. Formally unsalaried, their livelihoods depended on the hard work of maintaining good relations with incoming officials from the capital while harnessing their licensed positions on local markets for ritual and healing services. They left behind few lofty biographies, elegant poems, or refined calligraphic works, but their quiet presence in historical sources offers a rare view of the bureaucracy from the ground up, in and beyond the county yamen.

Local government under the Qing unfolded in many moments too small for an empire to remember, but too big for a county to forget. Across the provinces of China, when diviners lingered in the background—perched atop drum and bell towers, stationed in examination halls and reception rooms, or hurrying across temple altars and opera stages—the imperial state revealed itself in full ritual pageantry, enacting governance before a quarter of humanity through brilliant spectacles of sound and ceremony.Footnote 102

Contributions of funding organizations

The researching and writing of this article were made possible in part by funding from the MIT School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (SHASS) Research Fund.

Competing interests

The author declares none.