Introduction

The story of the Flint Water Crisis underscores the need for community-engaged and informed responses for protocols that address public health crises. Flint citizens began to sound the alarm in April 2014. For 18 months, community members appealed to officials at all levels of government, citing concerns and gathering evidence about the discolored, foul-smelling water and presenting water samples with co-occurring testimonials of serious health problems. During that time, the Flint Community was able to engage an out-of-state expert to test for lead in the water and a local pediatrician who independently detected high lead levels in Flint children. City and state officials initially ignored the outside experts and the local pediatrician [Reference Ruckart, Ettinger, Hanna-Attisha, Jones, Davis and Breysse1]. A city-wide State of Emergency was not declared until December 2015, with the state and federal governments following in January 2016. Government entities, public health agencies, and academic institutions failed to respond with the immediacy befitting the crisis.

These delays and failures of accountability occurred despite the presence of multiple health research partnerships between academic institutions and community partners in Flint. Consequently, local Flint leaders leveraged their relationship (of more than 15 years) with the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR) at the University of Michigan, to identify and convey community-articulated health needs related to the crisis. The director of MICHR traveled to Flint, to meet with community leaders to identify and clarify what would be an appropriate response regarding the water crisis.

This resulted in the development of a community-academic workgroup composed of representatives from the MICHR and the Community Based Organization Partners (CBOP), a community anchor agency in Flint. The original aim was to apply community-based participatory research principles and approach to the study of community disaster response, in the context of the Water Crisis. Immediately following the onset of the Flint Water Crisis, qualitative studies that engaged Flint residents and stakeholders highlighted the critical importance of addressing mistrust, building trust, and promoting “community science” [Reference Carrera, Key and Bailey2–Reference Hamm, Carrera and Van Fossen3]. Later, the focus broadened to include COVID-19 and racism as a public health crisis [Reference Johnson and Key4–Reference Key, Carrera and McMaughan6].

The idea for developing a protocol for academic/community engagement during a public health crisis and incorporating this into MICHR’s U01 grant, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, came from Flint community partners. The Workgroup determined that there was a clear need for the development of a Research Readiness and Partnership Protocol (R2P2; available at: https://available-inventions.umich.edu/product/research-readiness-partnership-protocol). It is a framework centered on community engagement to respond to community crises. R2P2’s purpose is to guide community engagement early in the research process and to increase the capacity of communities threatened by disasters to engage in translational research [Reference Key, Furr-Holden and Lewis7]; its development was critically informed by key interviews with Flint community leaders, which were conducted using community-partnered methods. The goal of this manuscript is to report the results of these interviews, which informed the ultimate development of the R2P2 protocol (which will be published separately).

Description of the partnership

From the outset of MICHR’s funding as a Clinical and Translational Science Award in 2007, the institute began partnering with community organizations in Flint, Detroit, and Ypsilanti, MI. The partners from Flint were mainly members of the CBOP, a non-profit organization representing over forty multi-sector and faith-based community organizations. CBOP includes experienced citizen scientists who have engaged in CBPR in Flint since the W. K. Kellogg Foundation’s Community Based Public Health Initiative in the early 1990s [Reference Samuels, Vereen and Piechowski8].

The authors of this study include MICHR faculty, staff, CBOP board members, and other community partners, who formed a workgroup with the aim of guiding the implementation of health research initiatives involving communities in crisis. The authors met bi-monthly starting in 2016, and all the community partners in the Aim 2 Workgroup were compensated $25/hour for their time for the duration of the project. This group adopted a CBPR approach to develop and enhance MICHR’s support of health research and its translation, addressing the long-standing health disparities in Flint, particularly those revealed and exacerbated by the ongoing water crisis.

Methods

Study design

In the Fall of 2020, the Workgroup utilized a CBPR approach to inform the design for qualitative interviews. Interview questions were developed by the Workgroup over the course of multiple in-depth discussions. The study was approved by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board and reviewed by the Community Based Organization Partners Community Ethics Review Board (CBOP CERB), which provided a letter of endorsement.

R2P2 conducted qualitative interviews virtually with selected participants from the Flint and greater Genesee County community, lasting approximately one hour. The interviews were conducted over the University of Michigan’s secured Zoom platform. All interviewees provided voluntary consent to participate in the study. The recorded interviews were transcribed, de-identified, and analyzed collaboratively.

Study population

The population was obtained from a database of 192 key community members who held leadership positions in organizations serving the city of Flint. To create the database the Workgroup identified 12 sectors deemed to represent a diverse range of perspectives on the water crisis. These sectors were: Community Agencies, Corporations, Educational Institutions, Senior Citizen Serving Organizations, Faith-Based Institutions, Financial Entities, Governmental Agencies, Health Care Agencies, Housing Agencies, Private Foundations, Public Health Agencies (including mental health), and Youth Serving Organizations. In addition to utilizing the community connections of Workgroup members, supplemental online research was conducted to identify as many potential participants as possible from each category. Efforts were made to select organizational leaders who had a broad knowledge of the impact of the crisis and of their agency’s response to the crisis. Furthermore, potential participants who were present in the agency during the water crisis were prioritized over those who joined the organization after the crisis began, who were directly impacted by the crisis, and/or who were involved in the response to the crisis.

Recruitment

Invitations were sent via email to all 192 community members. In addition, Workgroup members reached out to those on the list who were in their network of contacts to encourage them to participate in the study. Efforts were made to ensure representation from as many sectors as possible. Due to a COVID-related financial freeze enacted by the University of Michigan, it was not possible to offer interview participants compensation.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by one author (AM), with additional team members present as note takers, utilizing a semi-structured interview guide developed by the Workgroup. The guide consisted of nine questions plus prompts designed to garner participants’ perspectives about the Flint Water Crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racism as a public health crisis. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Two authors analyzed transcripts independently (one community member and one academic partner for each transcript, with all authors participating) and identified themes. Pairs of reviewers met to discuss and reach consensus. When needed, a third author adjudicated differences. In addition, reviewers highlighted representative quotes from which comments were selected and included as illustrative examples in the results.

Results

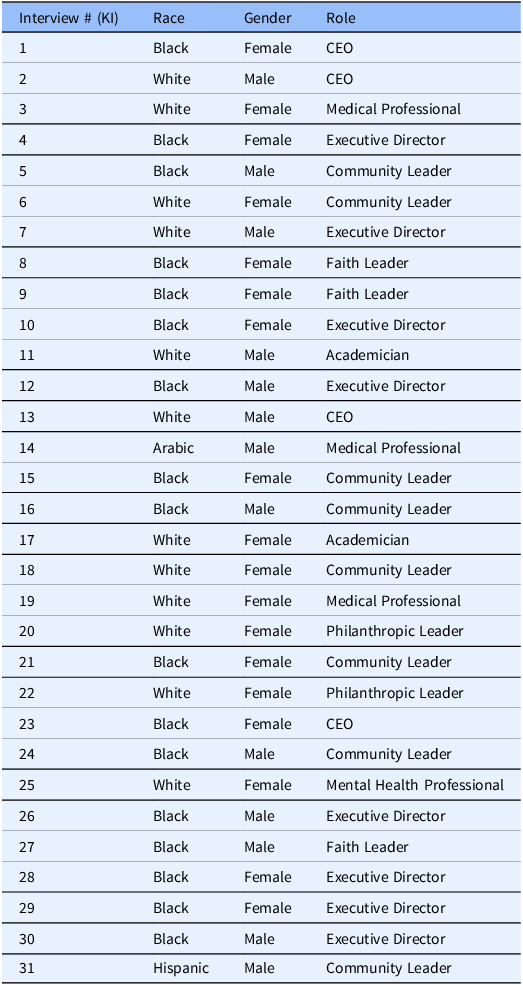

Participants (n = 31) were female (58%) and male (42%), and were Black (55% Black, 39% White, 3% Hispanic, and 3% Middle Eastern/North African). (see Table 1). All participants stated they were members of the Flint Community as of the onset of the Flint water crisis. From these qualitative interviews, the following ten main themes emerged: Community Visits, Neglect/Denial, Delayed Response, Bi-Directional Communication, Resource Distribution, Cross-Sector Collaboration, Digital Model, Equitable Partnership, Follow-up Lapse, and Racism. See Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 for additional supporting quotes.

Table 1. Key interviewee descriptors

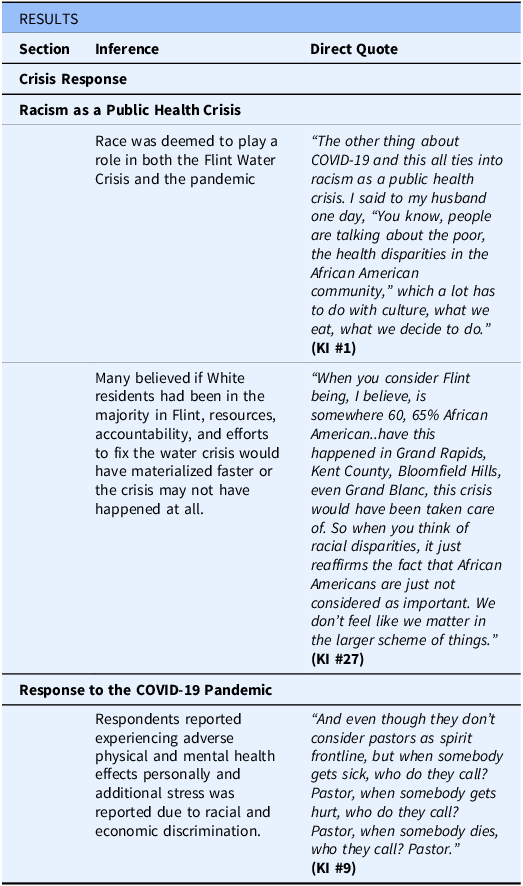

Table 2. Additional crisis response interview quotes: community voice and response

Table 3. Additional crisis response interview quotes: racism and COVID-19 response

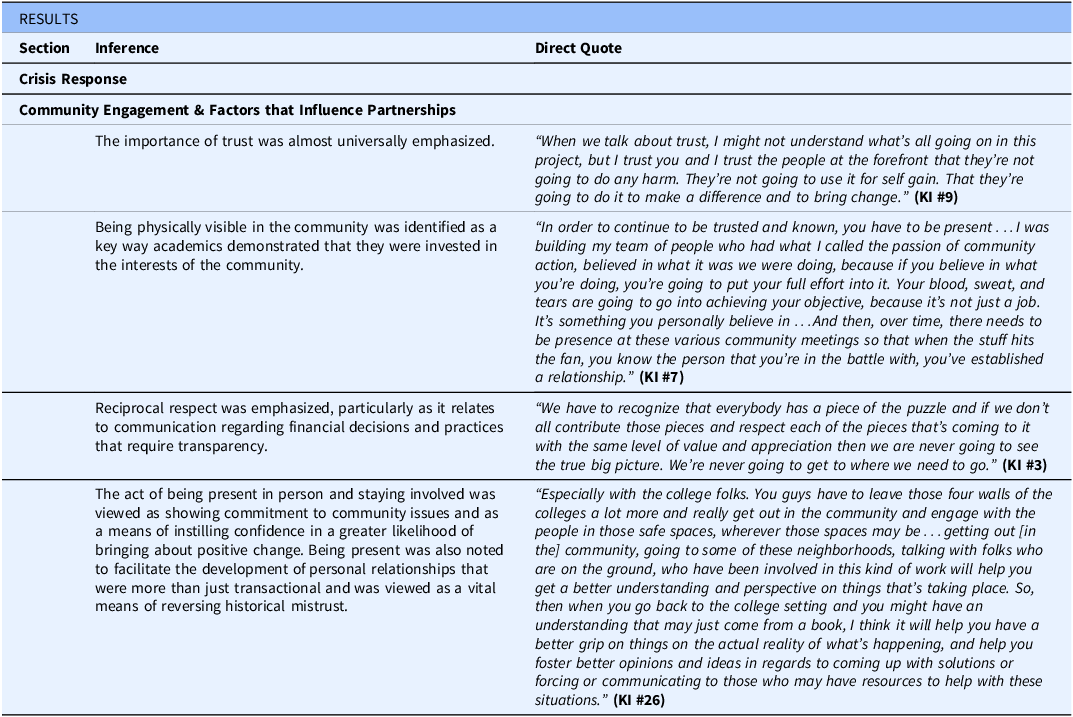

Table 4. Additional crisis response interview quotes: CE and factors that influence partnerships

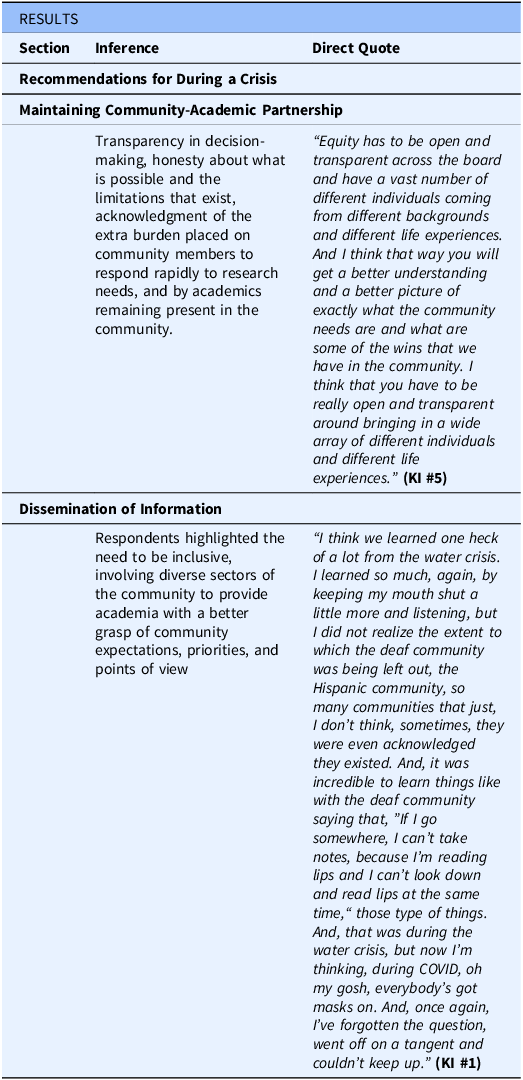

Table 5. Additional recommendations for during a crisis interview quotes

Table 6. Additional trust interview quotes

Crisis response

Response to the Flint Water Crisis

As they reflected upon the response to the Flint Water Crisis, most respondents noted two main problems: Community voice and response – From the first signs of contamination, community members voiced their concerns. However, the community-driven crisis response was faster than the response from the government. Early canvasing was organized (by groups such as CBOP and Flint Rising) to reach Spanish-speaking families for whom a language barrier impeded access to public information. “Existing community resource networks, including groups like the Concerned Pastors for Social Action and Greater Holy Temple’s Community Outreach Center were repurposed for the distribution of bottled water, water filters, and information. (KI #9) Community organizations (e.g., faith-based groups) distributed information via mailing lists, in-person contact, and radio stations.” (KI #1) Leadership Neglect/Denial – Top-down government denial that anything was wrong with the water, despite concerns vocalized by community members, was almost universally noted. Many community members continued to insist that something was wrong. Still, others trusted the government reports and continued to drink and use the tap water that city and state officials said was safe [Reference Ruckart, Ettinger, Hanna-Attisha, Jones, Davis and Breysse1]. Participant reflections such as, “I think the focus on getting accurate information is an important piece of that, and information that’s not tainted by politics” (KI #20) highlighted the lack of timely accurate communication about the risks of the water led to greater exposure of community members to contaminants.

Racism as a public health crisis

Race was deemed to play a role in both the Flint Water Crisis and the pandemic. “I think that we still have a lot of work to do in order to make people realize that racism is a public health issue and that racism impacts the health and health outcomes of a large group of people. Again, politics play a role, the social environment plays a role, (and) economics play a role. There’s so many different layers to all of this that again if you address those inherent inequities that you will hopefully begin to see more parity in health outcomes. We’re not there yet and we have a long way to go. I think people are just now starting to recognize that racism is a public health issue.” (KI#3) Many believed that if White residents had been in the majority in Flint, resources, accountability, and efforts to fix the water crisis would have materialized faster, or the crisis may not have happened at all. A respondent shared, “The state certainly failed. I do subscribe to the theory that if this happened in Traverse City, or Ann Arbor, it would have been addressed much faster.” (KI #2)

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

There was broad consensus across the key interviews that the response from government/academic institutions to COVID-19 was far better than the response to the Flint Water Crisis. This was attributed to two main factors: first, COVID-19 is a tragedy that impacted the entire world, whereas the water crisis was a tragedy solely in Flint. And second, the Flint Water Crisis primed the pump for community response to the pandemic. Specifically, networks previously used for water and water filter distribution were utilized to distribute masks, information, and sanitizer when the pandemic started.

Regarding the pandemic, key interviewees shared that Black residents felt they were receiving inadequate health care (KI #21). Respondents reported experiencing adverse physical and mental health effects personally and for family members, friends, and acquaintances due to the Flint Water Crisis and the pandemic. Additional stress was reported due to racial and economic discrimination.

Community engagement and factors that influence partnerships

Many participants emphasized the importance of academic partners establishing respect, trust, and commitment through consistent community engagement and building relationships. They noted the need to acknowledge and use community expertise, along with the necessity of commitment to the community and its needs, “the community already got the answers. They’ve had these answers. They know what’s best. They know what works. The issue is people aren’t validating their voices and implementing what they’re saying.” (KI #28)

The importance of trust was almost universally emphasized. “Having a known, trusted connector would be phenomenal,” within the community was viewed as a vital means of elevating community voices and prioritizing community concerns. (KI #12) It was noted that a connector from the community and identified by the community increases the likelihood of the success of community-academic initiatives due to having a degree of established trust.

Being physically visible in the community was identified as a key way academics demonstrated that they were invested in the interests of the community. The act of being present in person and staying involved was viewed as showing commitment to community issues and as a means of instilling confidence in a greater likelihood of bringing about positive change. Being present was also noted to facilitate the development of personal relationships that were more than just transactional and viewed as a vital means of reversing historical mistrust. One interviewee stated, “When you get to know people, then you start to look at them as a person and not as an agency. When you can relate to people…it’s a little bit easier to listen when they say that they have a new need.” (KI #6)Another advised academics to “emphasize partnerships, not just with organizations, but with the people they serve.” (KI #1)

Respondents highlighted the need to be inclusive, involving diverse sectors of the community to provide academia with a better grasp of community expectations, priorities, and points of view. One respondent said, “a vast number of different individuals coming from different backgrounds and different life experiences…[are needed for] a better picture of exactly what the community needs” (KI #5), particularly those “who are being affected on an everyday level.” (KI #4) Resident advisory groups were recommended along with multidisciplinary teams in which members could learn from and about each other.

Participants shared that “direct contact with all partners heightens engagement and gets them to open up… and share what you are really faced with…[real] concerns and challenges.” (KI #16) Unfiltered information is conveyed and everyone gets the same message/information, which participants viewed as a means of building trust. This direct, in-person form of message delivery was of value due to the frequently stated belief that “information is power.” (KI #5) Providing clear, comprehensive information was viewed as helping with trust as suggested by this statement, “Because we have such a lack of trust here in the community because of the social ills that we’ve been dealing with over the last few years, and even years past if you’re just getting bits and pieces of information then that’s where we have that mistrust.” (KI #5)

Partnerships that prioritized equitable power-sharing and decision-making were important to most interviewees. In keeping with this priority, many noted the need to ensure community wisdom/input is equitably acknowledged and appreciated for its importance. Reciprocal respect was emphasized, particularly as it relates to communication regarding financial decisions and practices requiring transparency (e.g., about the ways universities benefit from partnerships). “…just honesty. Upfront transparency. And letting people know this is what’s going down. Right now, people… especially here in [the] city of Flint don’t trust. So, especially, thinking that somebody is making money off of them.” (KI# 24) Education about the language and processes of academia was suggested as a means of facilitating equity in partnerships. Another respondent stated, “Give as much as we get from the community. Until you begin to do that, there’s always going to be an imbalance in the relationship.” (KI #30)

Digital platforms for communication

In-person communication was acknowledged as a necessary and optimal component of bi-directional communication. However, it was noted that the use of digital platforms could enhance bi-directional communication for those with access. The digital divide presents a hurdle that must be overcome to foster quality communication.

Particularly for younger people, mobile apps were viewed as a way to facilitate contact that would not be possible otherwise. For example, one respondent stated, “I think they would probably do an app before they would explore a website.” (KI #4) While another noted “The younger folks would definitely love the app. Some of the seasoned individuals, who know how to do text messages now, they would use that. And then you have some people that are good on the social media aspect. So, I think all three would be beneficial. And to some extent even snail mail.” (KI #5)

For a digital approach to be helpful, study respondents suggested that it should use language that is digestible by the community at large (i.e., avoiding jargon and terms that might not be clearly understood) “When they started throwing out acronyms and things, I don’t have a clue what they’re talking about a lot of times.” (KI# 27) Common language should be developed with the input and buy-in of the community to increase the likelihood that it will meet the needs of the community and that it will be used by the community. In addition, it was emphasized that efforts should be made to reach all sectors of the community in communication strategies, including those with differing abilities. Due to the expense associated with the development of mobile applications, foundations might be considered as potential sources of funding. Furthermore, participants shared that digital tools should be updated regularly, and any new options should be complimentary rather than duplicative. “If somebody else is already doing it, don’t develop another app that becomes a duplicate where now people get confused and say, well, where should I go? They’re doing this and this organization is doing the same. Yeah, I can’t emphasize enough don’t duplicate the resources.” (KI #13)

Recommendations for during a crisis

Resource allocation – While the need for research in the midst of a crisis was recognized as important, respondents underscored the fact that residents have higher priorities at such times that they must pursue to safeguard and improve their health. Helping to address basic needs should be a first step that is given precedence by academic institutions before even considering moving forward with research. Respondents recommended steps to be taken by academia at the onset of a crisis. These included dedicating resources to non-research-related community needs, considering the additional cost to communities involved in research during a crisis. This requires equitable compensation for community partners who are members of research teams. “…ultimately, it’s really going to go down to having respect and consideration for the value of everybody that’s involved… just really the acknowledgment and respect that everybody is there for a reason or a purpose, and don’t discount or diminish or degrade somebody…” (KI #7)

Maintaining community-academic partnerships – Respondents emphasized the significance of maintaining community-academic partnerships during crises when resources are strained and at a time when relationships might fracture. Particularly during extreme circumstances, respondents suggested the quality of a partnership would be enhanced by: Transparency across the board, (KI #5) in decision-making, honesty about what is possible and the limitations that exist, acknowledgment of the extra burden placed on community members to respond rapidly to research needs, and by academics remaining present in the community.

Dissemination of information – In light of community members viewing information as power, respondents highlighted the critical need for accurate, trusted, and timely information sharing during the onset of a crisis. Respondents indicated that communication in a crisis should be equitably distributed to all sectors of the community, utilized to incorporate trusted partners in content development and dissemination, rapidly updated in real-time, shared via multiple channels (e.g., social media, snail mail, face-to-face), accessible to all community members (regardless of educational level or language preference) and inclusive of all in the community, particularly hard-to-reach groups (e.g., deaf and hard of hearing and immigrant populations). This is reflected in the following quote, ”That, again, going to those communities that they traditionally don’t go into, because a lot of times when we see these different academic projects or other things going on, they take a certain section of the community, but they don’t, in my opinion, they don’t always go to where the need is the greatest. And I think that if we’re looking to do something and have a true reflection of what the community is thinking and the community buy in, you must go in those areas that you traditionally would not go into. I think that is one of the key elements in doing anything that is going to be a holistic approach.” (KI #5)

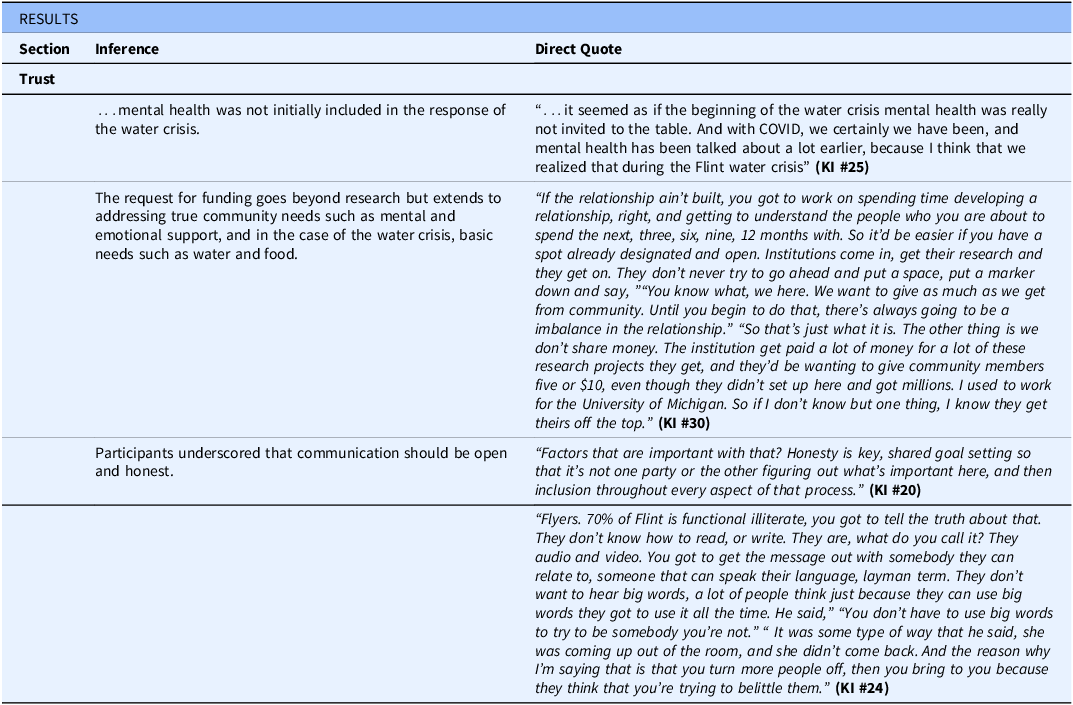

Trust

In general, when participants considered developing and disseminating a research readiness and partnership protocol, trust emerged as the major issue. Respondents identified history, resource allocation, and communication as main factors that impacted the level of trust in Flint.

Lack of trust was frequently noted and emerged as an issue that would impact the creation, dissemination, and adoption of health research resources and studies. One respondent simply stated, “But as a person, as a resident, I just mistrust. I mistrust the government as far as that’s concerned. So, lots of mistrust. At that particular time, I didn’t do anything other than taking care of my own family.” (KI #16) Built upon a long history that includes fractures in the relationship between communities and institutions/agencies, participants expressed the need to address this issue in every aspect of a protocol and to take steps to build trust, which should include spending more time in the community to understand community resource needs.

Allocation of resources and funding for community-engaged efforts was noted as a concern and frequently linked to the development of trust. A representative comment regarding funding stated that “[we have] Never received any significant funding.” (KI #7) These discrepancies highlight the concerns communities have when engaging in research with academic institutions and undergird some of the issues of trust. The request for funding goes beyond research but extends to addressing true community needs, which, in the case of the water crisis, include basic needs such as water and food, and more generally, mental and emotional support. Another respondent expressed that mental health was not initially included in the response to the water crisis for the community. (KI #25) Key interviews illuminated a salient idea that resource distribution referred not only to the streamlining of tangible, physical resources (e.g., food, water, supplies) but also to the equitable dissemination of “information” as a resource. Key interviews pointed to “the lack of cooperation among [government] agencies and the lack of information sharing” (KI #3) as a challenge faced during the water crisis. Respondents emphasized the importance of distributing information in a manner that reaches the entire community, as it is a resource that will help everyone and will build trust.

Participants underscored that communication should be open and honest. One representative comment about communication and trust stated, “You can’t go in judgmental. You have to go in with an open mind… use baby steps . I think that it’s all about your tone and your delivery. If you’re sincere, and you’re showing humility, I think that goes a long way in being able to stem the ties of the mistrust that you would see in the less marginalized population here in the community.” (KI #5)

Recommendations included developing structured ways of being inclusive in the dissemination of information (e.g., having an extensive list of contacts to aid in dissemination) and using multiple pathways to adequately address specific groups. For example, one key interviewee stated, “We have videos that are archived for various scenarios, be it a tornado or a flood…to communicate with deaf and hard of hearing communities who may not be able to get the same information out of a news report that somebody else might get. Developing communication pathways for emergent situations so that those various populations can be taken care of.” (KI #3) Another key respondent noted, “We go into some of our senior centers. I think that is an avenue. You go to the east side of Flint. You go to north Flint. I think to be able to encompass the greater community would be key. To go into some of the rural areas because they have their challenges as well. So, I think that you just have to think outside the box as it relates to this, but you have to bring everybody to the table. Everybody has a voice.” (KI #5) Faith-based organizations, particularly churches, were repeatedly highlighted in the interviews as a community hub for resource sharing and information exchange. One respondent proposed leveraging churches “We’re talking about a media outlet that shoots out information. So, if we have them in different places like it’s easy to get their information out.” (KI #23)

Discussion

In summary, respondents indicated that information should be presented directly to the community in accessible ways that provide opportunities to ask questions (e.g., via community forums). Communication should be done with sincerity and humility while at the same time promoting equity. Expectations should be established at the onset regarding how the information will be shared with regular follow-up to evaluate consistency and effectiveness. Community involvement is required “early and often” to ensure projects are designed for the right community impact, as the “Community must care about the research” for it to be successful. Furthermore, the study highlighted several implications for community-academic partnerships, academic institutions, and best practices for public health crisis response.

Implications for:

Community-academic partnerships

Community-engaged research and CBPR have demonstrated the importance and impact of creating trusted community-academic partnerships for research. These collaborative forms of research partnerships help foster bi-directional learning, co-leadership, and greater uptake of findings within the community. However, for the past 3–4 decades, community-academic partnerships focused primarily on research [Reference Grattan, Roberts, Mahan, McLaughlin, Otwell and Morris9–Reference Volenzo and Odiyo11]. As seen with the Flint Water Crisis and other such tragedies, partnerships for research alone are not enough [Reference Agani, Landau and Agani12–Reference Généreux, Petit, Roy, Maltais and O’Sullivan14]. This study shows the impact of community-academic partnerships in a crisis response.

MICHR and CBOP demonstrate the way in which community-academic partnerships can reach beyond the confines of research and collaborate effectively during a public health crisis to meet public health needs. Building on decades of relationship, academic partners must communicate and listen as the community articulates its needs when a crisis occurs and avoid assuming what communities’ most important and relevant needs are. The strategic actions taken by MICHR and CBOP can serve as a model and blueprint for community-academic research partnerships as they pivot to face future crises. Trust is critical to build partnerships between community, academia, and government for crisis response.

Academic institutions

Academic institutions must engage in health-related research with the ultimate goal of improving the wellbeing of those they serve. Public health crises require these institutions to respond by conducting research that will lead to improved health in the future and, crucially, address current community health needs. To face this twofold challenge, long-term, trusted, and transparent relationships must be forged between community and the academy at all levels of the institution. This can only be accomplished when academia values and substantive support for the formation and maintenance of such relationships is achieved. These connections should ideally be in place before a disaster occurs.

Within the academic setting, faculty are strongly motivated to participate in activities that will lead to promotion and tenure; indeed, their jobs often depend on it. Typically, this involves demonstrating excellence in scholarship via the acquisition of grants and publication of findings in highly esteemed journals. In general, there is a preference for the value of basic science. Whereas CEnR and the partnerships formed have not been deemed to carry as much weight when assessing the significance of faculty members’ scientific contributions.

The participants’ experience navigating and surviving the Flint Water Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic highlights that while health research is critical to pursue, deep connections between academia and the community are needed to protect public health and facilitate that research. These crises underscore that collaborations with the community are vital and should be incorporated into research. This will be achieved by a greater acknowledgment of the value of such work and by providing systemic rewards for developing community-engaged efforts that truly meet the needs of communities.

Furthermore, the repeated occurrence of public health crises suggests an urgency regarding initiating changes in academic culture to prepare for and respond to these more effectively. This is particularly important for those communities that carry a disproportionate burden of illness due in part to the impact of social determinants of health and systemic racism. While such communities are most susceptible to the negative health impacts of public health crises, they are also necessary partners to help academic institutions and public health professionals achieve the greatest impact from their work.

Public health crisis response

Public health crises do not affect all communities within a state or region equally. Vulnerable and/or marginalized communities, such as Flint, Michigan, unnecessarily experience greater harms at all stages of a crisis as well as in the recovery phase. Community-academic partnerships, especially those formed and functioning around clinical and translational science, provide a potentially potent antidote [Reference Andrulis, Siddiqui and Purtle15]. Tools such as the R2P2 address and guide the formation of new partnerships and the strengthening of existing partnerships to deal effectively with public health crises. These partnerships and this proposed protocol address the services that define public health, including the conduct of research to better understand the crisis, respond to it, and recover from it.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be considered within the context of certain limitations. This was a qualitative study consisting of a convenience sample. Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. However, residents of similar communities may consider the findings relevant and helpful in building partnerships to address crises.

Conclusion

The Flint Water Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic both highlight that while research is critical, deep connections between academia and the community will prioritize community needs and the translation and application of that research to protect public health. The themes that emerged from these interviews provide the basis for the development of equitable and resilient community-academic partnerships, able to navigate the challenges experienced in a crisis. The absence of such dynamic relationships contributed to the delay of a timely response, resulting in the irreparable physical and emotional harm to Flint residents. This underscores the need for a stronger commitment to fostering community-academic partnerships as a component of the translational research enterprise. Furthermore, this work highlights an opportunity for greater acknowledgment and utilization of CEnR approaches, including CBPR, by academic institutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the individuals who made substantial contributions to this work. We want to thank the previous and current leadership of MICHR, who supported the focus on crises; Drs. George Mashour, Julie Lumeng, Erica Marsh, and Polly Gipson Allen for their continuous advocacy and resource allocation to support the equitable involvement of our community partners in this work. Ms. E. Yvonne Lewis, a Flint community partner, contributed initial input on the project. The authors thank CE staff, faculty, and community partners, especially Karen Calhoun, for sharing best practices in community-engaged research and providing integral feedback and guidance on this work throughout the years. We would also like to thank Marisa Conte, at the University of Michigan’s Taubman Health Sciences Library, for her help with information services and support. Lastly, the Workgroup wishes to thank the residents of Flint, who are still facing many of the challenges addressed in this protocol, for their generosity in contributing to its development.

Author contributions

AM was involved in the conceptualization, writing-reviewing and editing, supervision, collecting data, analyzing, and interpreting data, and project administration. KJ and NG were involved in conceptualization, writing-original draft, reviewing and editing, collecting data, analyzing, and interpreting data. DV, BC, SB, LE, VN, ES, PP, EGM, AS, EHD, DR, KK, and SW were involved in conceptualization, writing- drafting, reviewing, and editing, data collection, analyzing, and data interpretation.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through award number UL1TR002240 and UM1TR004404.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.