Background

The “hidden curriculum” refers to implicit norms and expectations in academic environments that are absorbed through socialization and experiences rather than formal instruction [Reference Margolis1–Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3]. For scientists, the hidden curriculum includes expectations around professional conduct, ethical standards, social interactions, and career navigation, all of which shape understanding of and success in academia [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3]. However, scholars from backgrounds underrepresented in the scientific workforce (URSW) often have less access to this informal knowledge compared to their non-URSW peers, which can lead URSW scholars to experience feelings of imposter syndrome and isolation, contribute to low retention in academic medicine, and further perpetuate structural biases such as racism, sexism, ableism, and classism [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3–Reference Zambrana, Carvajal and Townsend7].

Mentorship is a primary vehicle through which hidden curriculum knowledge is transmitted. Mentors play a crucial role in helping their mentees navigate the hidden curriculum by providing guidance on professional networks, implicit academic hierarchies, and essential skills for success [Reference Kaplan, Gunn, Kulukulualani, Raj, Freund and Carr8]. By making the hidden curriculum explicit, mentors can demystify the academic environment and empower mentees to navigate it effectively [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, DSouza, Martin and Kennedy9]. In addition, when mentors recognize and address their own biases, which can be facilitated by training in the hidden curriculum, it fosters diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) and ensures all scholars have the opportunity to thrive in academia [Reference Javier, Solis and Paul10,11].

However, mentors from non-underrepresented backgrounds may struggle to guide URSW mentees due to differences in lived experiences and social identities [Reference Nivet, Taylor and Butts12–Reference Asquith, McDaniels and Baez14]. Consequently, mentors may unintentionally provide more tailored or effective guidance to mentees with similar backgrounds, inadvertently disadvantaging URSW scholars [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3,Reference Smith4]. Indeed, while mentors largely agree on the importance of a culturally responsive approach to mentoring, faculty members may lack the confidence and skills to enact these techniques [Reference Suiter, Byars-Winston, Sancheznieto, Pfund and Sealy15,Reference House, Spencer and Pfund16]. Non-URSW mentors’ lack of relevant lived experience may also help explain the importance that URSW mentees place on finding a mentor of similar identity to their own [Reference Dahlberg and Byars-Winston17]. At the same time, research highlights the benefits of diverse mentoring networks that include individuals from a variety of backgrounds and roles as a helpful source of informal knowledge, professional connections, and career advancement [Reference Zambrana, Carvajal and Townsend7,Reference Schoenberg, Robinson and McGladrey18,Reference Rodriguez, Campbell, Fogarty and Williams19].

Structured mentor training programs in clinical and translational science have demonstrated a range of benefits, including improvements in mentors’ knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy [Reference Feldman, Steinauer and Khalili20–Reference Bonilha, Hyer and Krug24], as well as increased access to mentorship and greater career satisfaction among mentees [Reference Beech, Calles-Escandon, Hairston, Langdon, Latham-Sadler and Bell25]. In recent years, a growing number of interventions have focused specifically on training mentors to foster culturally aware mentorship for early-career faculty from URSW backgrounds, demonstrating promising outcomes for both mentors and mentees [Reference Johnson, Fuchs and Sterling26–Reference Pfund, Sancheznieto and Byars-Winston33]. Despite this progress, there is wide variation in the structure and content of available training programs, with limited use of standardized evaluation frameworks [Reference Sheri, Too, Chuah, Toh, Mason and Radha Krishna34]. In addition, many programs rely heavily on general cultural competency models without adequately addressing the nuanced realities of power dynamics, systemic bias, and microaggressions that mentees from URSW backgrounds often face in academic environments [Reference Walters, Simoni and Evans-Campbell35,Reference Gandhi, Fernandez and Stoff36].

To address this need, our study aims to clearly identify and articulate hidden curriculum competencies relevant to the effective mentorship of URSW scholars. In this paper, we describe the development, expert assessment, and refinement of 16 hidden curriculum competencies specifically designed to equip scientific mentors with the tools to demystify implicit academic norms and structures. These competencies are synthesized into a conceptual framework intended to inform future mentor training, program evaluation, and institutional practices that promote a more inclusive and equitable academic environment.

Methods

Competency development

We developed a set of 16 competencies specifically focused on the skills and knowledge needed by scientific mentors working with URSW scholars. As a novel contribution to an emerging area of scholarship, the competencies are intended to be both preliminary and complementary – filling a gap in existing mentoring frameworks and measures by focusing explicitly on skills and topics relevant to the hidden curriculum. The initial competencies were drafted by the primary author (Felicity Enders, PhD), who has extensive experience with mentoring and training programs focused on DEIA. Since 2016, Enders has served as Program Director for three training programs (one predoctoral and two postdoctoral) and has delivered training on the hidden curriculum to mentors and mentees at 12 institutions and several national meetings. Originally conceptualized in the context of general education [Reference Jackson37], the hidden curriculum was reconceptualized by Enders through a diversity lens based on direct input from URSW mentees [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3]. In 2023, Enders synthesized key hidden curriculum concepts and, with input from co-authors, drafted initial competencies to support scientific mentors in successfully mentoring across diversity.

To refine and contextualize the initial competencies, multiple DEIA competency frameworks were first reviewed [38–41]. Our approach to competency development methodologically aligns with established methods used in translational science competency frameworks by emphasizing structured skill development and expert-informed validation [Reference Sonstein and Jones42–Reference Oster, Lindsell and Welty44]. Consistent with previous work, we engaged DEIA experts in translational science as stakeholders to assess the relevance of each competency [Reference Enders, Lindsell and Welty45].

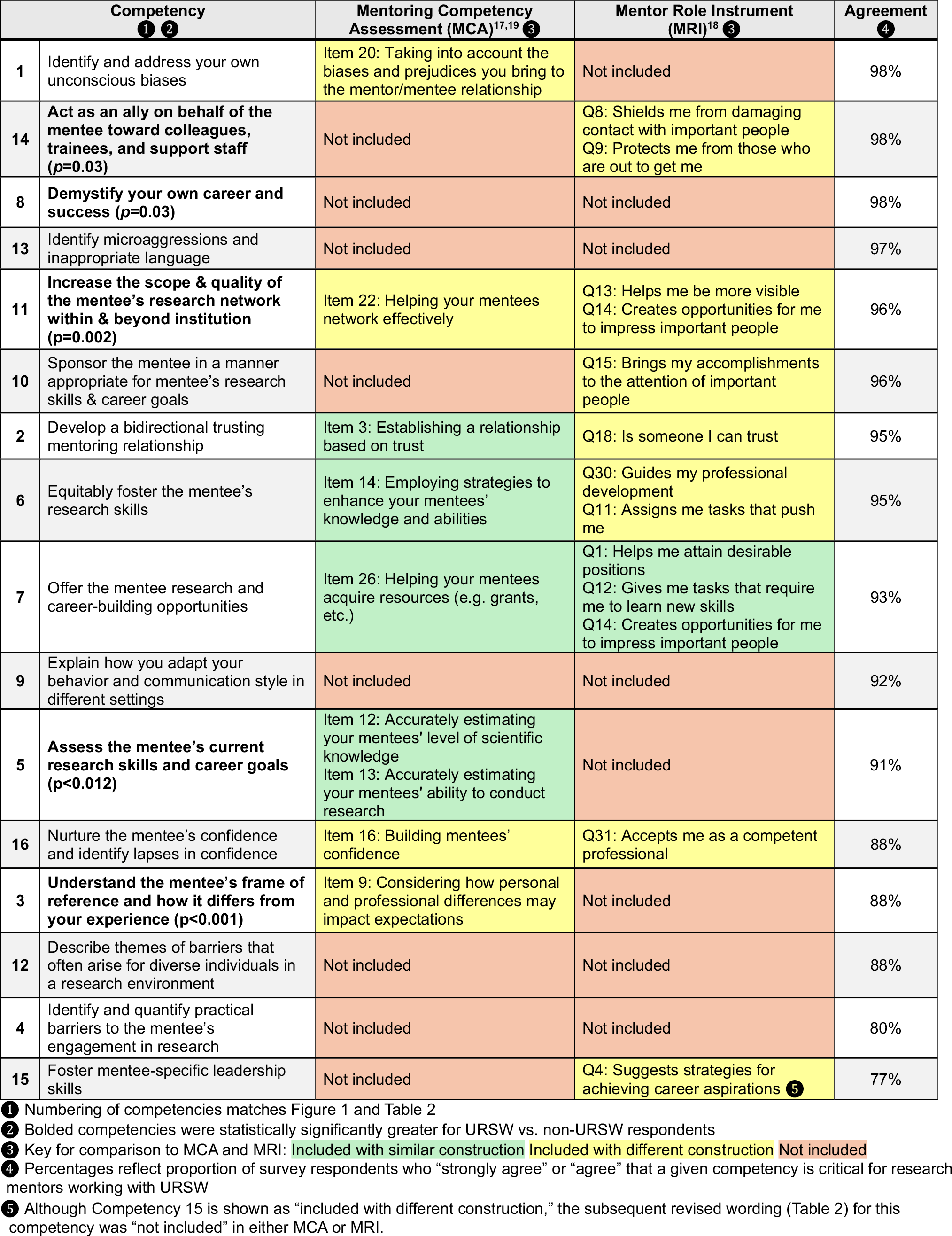

Finally, the developed competencies were explicitly aligned with two widely used mentoring tools – the Mentoring Competency Assessment (MCA) and the Mentor Role Instrument (MRI) – which assess general mentoring effectiveness but not diversity-specific hidden curriculum challenges (see Fig. 1) [Reference Fleming, House and Hanson46–Reference Hyun, Rogers, House, Sorkness and Pfund48]. Five competencies (Competencies 2, 5–7, and 11) closely mirror items in the MCA and MRI but were contextualized to emphasize diversity-related challenges. Another set (Competencies 1, 3, 10, 14–16) significantly adapted MCA and MRI concepts to explicitly address mentoring across diversity. The remaining five competencies are completely novel: Competency 4 (Overcome practical barriers) emerged from previous mentoring work, Competencies 8 and 9 were shaped by national conference discussions and presentations on the hidden curriculum led by Dr Enders, and Competencies 12 and 13, which are focused on systemic barriers and microaggressions, drew from DEIA literature and What Works for Women at Work, a text-based on qualitative interviews with women in leadership [Reference Williams and Dempsey49]. Thus, the newly developed competencies represent an innovative fusion of DEIA principles with scientific mentoring practices, tailored to the specific context of mentoring across diversity.

Figure 1. Hidden curriculum competencies as written in the survey, comparison to two existing mentorship evaluation measures, and agreement among 62 surveyed national diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility experts that a given competency is critical for a mentor to successfully mentor across diversity.

Study design

To gather feedback on the draft competencies, a cross-sectional, online survey was conducted among DEIA experts to assess the perceived importance of each competency for mentors who work with URSW mentees. This study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Participants and data collection

A link to the survey was distributed via email by Dr Enders to representatives of two professional organizations that have demonstrated a commitment to diversifying the scientific workforce: the DEIA Enterprise Committee of the National Clinical Translational Science Award consortium and the Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Special Interest Group of the Association for Clinical and Translational Science. The leadership of these two groups was asked to disseminate the survey to their members (N = 116) via email and send periodic reminders over the collection period. The email explicitly stated that participation was voluntary and no remuneration was offered. The survey was administered using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform (Provo, UT). It was fielded from June 13–27, 2023.

Survey instrument

Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed that each hidden curriculum competency is critical for research mentors to successfully mentor across diversity. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale (“Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”). An open-text field was included to capture qualitative feedback on the competencies, allowing respondents the opportunity to suggest refinements or provide additional insights. In addition, respondents could indicate their academic rank (full, associate, or assistant professor, instructor, or no academic rank).

Finally, respondents were asked to report whether they belonged to at least one URSW group (Yes/No). To define URSW for survey respondents, we used criteria informed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria for underrepresented populations in the biomedical, clinical, behavioral, and social sciences research workforce [50]. This includes individuals from racial and ethnic groups that have been shown to be underrepresented in biomedical research (including Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islanders), individuals with disabilities, individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, and women at senior faculty ranks in certain fields where they are underrepresented. The criteria presented to our survey respondents were broadened to include identification as a woman, regardless of rank or field [Reference Helman, Bear and Colwell51].

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for competency ratings and demographic items. Agreement for each competency is reported as the percent of respondents who selected either “strongly agree” or “agree” regarding its importance. Differences in ratings between URSW and non-URSW respondents were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Open-text responses were reviewed for 1) suggestions for modification and wording clarification and 2) additional competencies that were proposed with similar concepts by two or more respondents.

Results

Out of 116 DEIA experts invited, 62 completed the survey (53.4% response rate). Among those, 56 provided demographic information: Half held academic rank as associate or full professor (28/56), and 82% identified as meeting one or more URSW criteria. Notably, because the survey language defined URSW to include women of any faculty rank or field, this category likely includes respondents who are women but may also be White or Asian, not living with a disability, and not from a disadvantaged background.

Competency ratings

Results (Fig. 1) indicated broad agreement on the importance of all hidden curriculum competencies for scientific mentors working with URSW mentees. The highest-rated competencies overall were: “Identify and address your own unconscious biases” (98%), “Act as an ally on behalf of the mentee toward colleagues, trainees, and support staff” (98%), and “Demystify your own career and success” (98%). Competencies rated lower included “Identify and quantify practical barriers to the mentee’s engagement in research” (80%) and “Foster mentee-specific leadership skills” (77%).

Differences by subgroup

Compared to those from a non-URSW background, URSW respondents placed greater emphasis on acting as an ally (100% vs. 90%; p = 0.03), demystifying career success (100% vs. 90%; p = 0.03), expanding the mentee’s research network (100% vs. 80%; p = 0.002), assessing mentee’s current research skills (95.5% vs. 70%; p = 0.012), and understanding mentee’s frame of reference (95.5% vs. 55.6%; p = 0.001). Conversely, majority of respondents were more likely to prioritize identifying the mentor’s own unconscious bias (100% vs. 97.8%), identifying microaggressions (100% vs. 95.7%), and sponsoring the mentee in a manner appropriate for the mentee’s research skills and career goals (100% vs 95.6%), though these differences were not statistically significant. No differences in ratings were observed by academic rank (results not shown) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

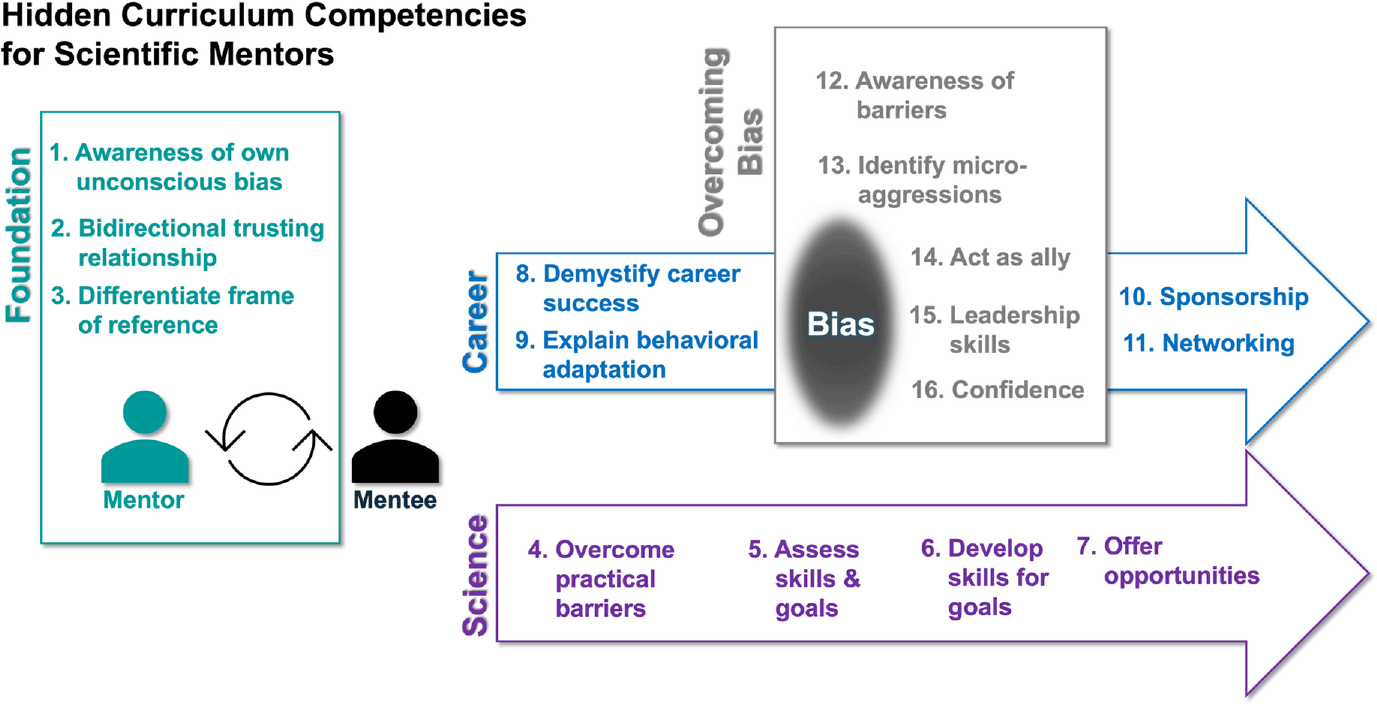

Figure 2. Comprehensive framework for the hidden curriculum competencies for research mentors. Competencies are shown in four domains: Foundation, Science, Career, and Overcoming Bias.

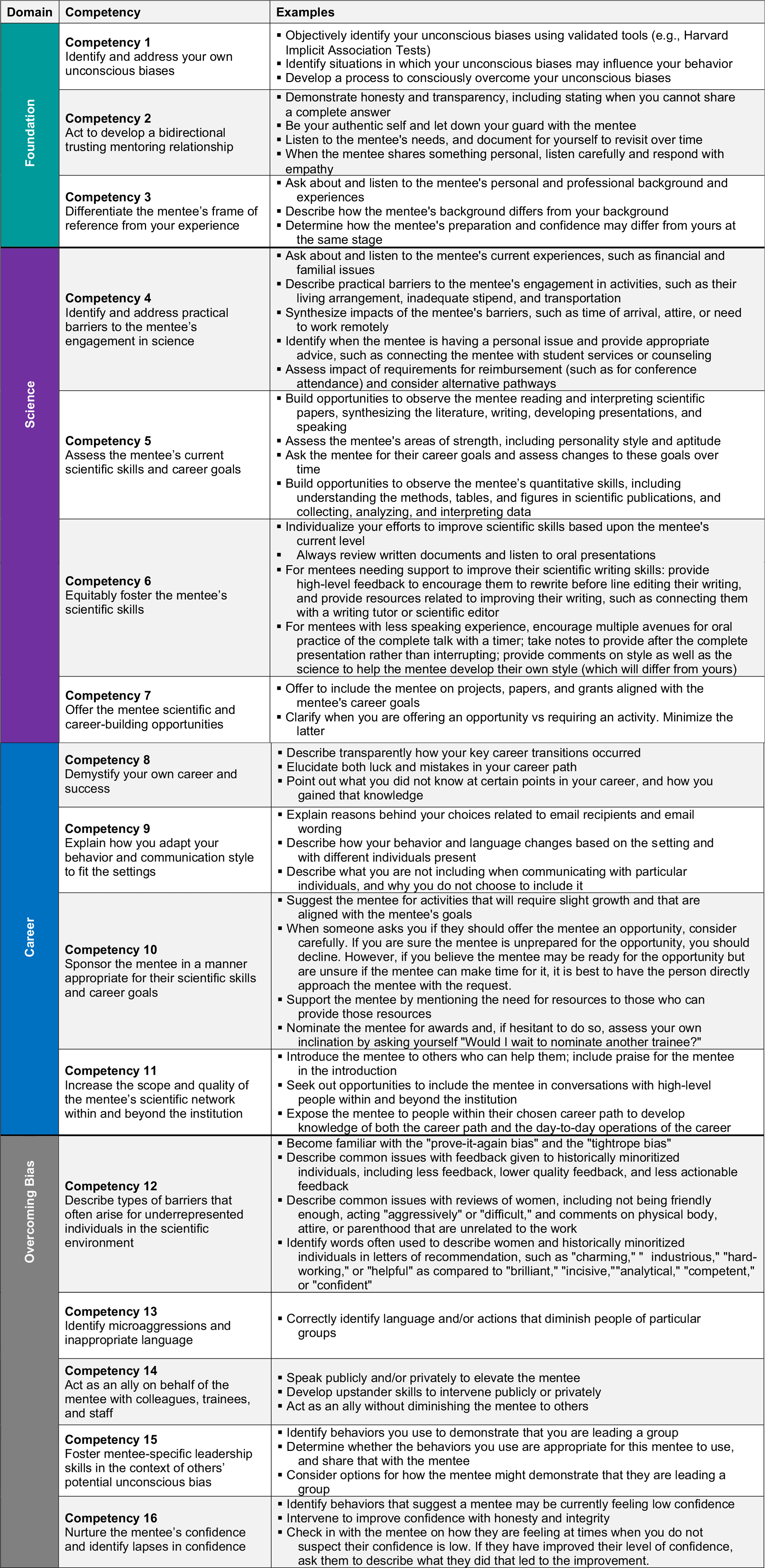

Figure 3. Revised hidden curriculum competencies for scientific mentors by domain with examples.

Synthesis: conceptual framework and refinement of the competencies

The competencies were refined using the results above, reordered, and grouped into four overarching domains (Fig. 3). No additional competencies were proposed. However, modified wording was proposed for several competencies, which are discussed below. In addition, all competencies were re-worded to focus on “science” rather than “research.”

A. Foundation: The root of the relationship between mentor and mentee. This domain emphasizes mentors reflecting on their unconscious biases (Competency 1) and building a bidirectional, trusting relationship with mentees (Competency 2). Although trust-building requires effort from both parties, mentors have the primary responsibility for establishing a trusting environment where mentees feel comfortable sharing their backgrounds, experiences, and challenges. Mentors should also recognize how their own background and frame of reference differ from that of their mentees (Competency 3).

Refinements. Competency 2 was revised to reflect that mentors can control their own actions but not the outcomes of these actions. Hence, the mentor should “Act to develop a bidirectional trusting relationship.” Similarly, Competency 3 was adjusted to focus on “differentiating” rather than “understanding” the mentee’s frame of reference.

B. Science: Empower engagement and develop the mentee’s desired scientific skills. These competencies focus on the mentor’s role in developing mentees’ scientific skills. This begins with addressing practical barriers to mentee engagement in science (e.g., financial constraints, competing responsibilities; Competency 4), followed by assessing mentees’ scientific skills and career goals to facilitate tailored mentorship approaches and support (Competency 5). Mentors are encouraged to provide individualized feedback (Competency 6) and offer growth opportunities through scientific projects, papers, and grants (Competency 7).

Refinements. Competency 4 was revised to emphasize resolving practical barriers rather than quantifying them. Based on respondent feedback, an example related to financial barriers (e.g., conference reimbursement) was added. Also based on respondent feedback, Competency 5 was expanded to highlight variability in quantitative skills (in addition to writing and communication skills), with an additional example added.

C. Career: foster the mentee’s career independence and success. This domain highlights the importance of demystifying the mentor’s own career path (Competency 8), making transparent the key transitions, challenges, and opportunities that shaped their professional journey. This openness helps mentees see beyond the polished image often presented on a curriculum vitae and understand that career success often involves navigating uncertainties and making mistakes. In addition, mentors should explain how they adapt their communication style in different professional settings (Competency 9), modeling the flexibility required to succeed in various academic and research environments. It is helpful for URSW mentees to see that everyone adjusts their communication style, so they don’t feel that only those from URSW groups must “code switch.” Mentors should also act as sponsors, actively advocating for their mentees by introducing them to key networks and opportunities that can support their professional growth (Competencies 10 and 11). However, successful sponsorship and networking also depend on bias the mentee may face from others, leading into the next domain (“Overcoming Bias”).

Refinements. Competency 10 was revised based on feedback about the appropriateness of mentors declining opportunities on behalf of mentees. It now advises mentors to decline on their behalf if the mentor is certain that the mentee is unprepared for the opportunity, but otherwise allow mentees to decide how to balance new opportunities with their workload.

D. Overcoming Bias: Support the mentee in the context of bias. These competencies focus on recognizing and addressing systemic and interpersonal barriers that URSW mentees may face. Mentors must be prepared to identify and address bias and microaggressions (Competencies 12 and 13), act as allies in situations where bias is present (Competency 14), and develop the mentee’s leadership skills (Competency 15) while considering the potential impact of others’ unconscious biases. (Note: the term “unconscious” is used intentionally here, because the authors feel it is extremely difficult for a mentee to demonstrate leadership in the face of conscious or explicit bias; instead, mentors should report apparent instances through institutional channels.) Mentors should also watch for opportunities to develop the mentee’s sense of confidence, which may be deeply affected by a history of facing bias, and support them in building resilience and self-assurance.

Refinements. Competency 15 was revised to emphasize fostering mentee leadership skills specifically in the context of others’ unconscious bias.

Discussion

Despite growing attention to mentoring as a tool for supporting URSW scholars, existing frameworks emphasize broadly effective practices without directly addressing the hidden curriculum or the specific challenges that underrepresented scholars may encounter [Reference Beech, Calles-Escandon, Hairston, Langdon, Latham-Sadler and Bell25]. The 16 hidden curriculum competencies for scientific mentors described in this paper are designed to inform mentor training programs that address critical gaps in awareness and skills, ensuring that mentors are prepared to support URSW mentees effectively. Survey findings from a diverse, national sample of DEIA experts highlight the importance of these competencies. Respondents from URSW backgrounds particularly emphasized the need for mentors to identify and confront unconscious biases, demystify career paths, support with networking, differentiate the mentee’s experiences from their own, and serve as allies. Critically, all 16 of these competencies are teachable, providing a pathway for mentors to actively level the playing field for all scholars.

While a plethora of mentorship models in the health sciences exist, few incorporate specific training for mentors or focus on the unique needs of URSW mentees [Reference Gangrade, Samuels and Attar52]. Our framework aims to fill this gap by offering targeted guidance to better support the needs of URSW scholars. The resulting conceptual framework (Figure 2) illustrates how the four domains – Foundation, Career, Science, and Overcoming Bias – form an integrated framework for mentor development and training. This model fills a gap in health sciences mentorship by providing structured competencies tailored to the specific needs of URSW mentees, offering a roadmap for both individual mentor growth and institutional training programs. Each domain serves a distinct purpose, described in greater detail below:

A. Foundation: the root of the relationship between mentor and mentee

The Foundation domain establishes a critical base for mentoring by encouraging mentors to reflect on their unconscious biases and build trusting, authentic relationships with mentees. For example, mentors can begin by identifying their own unconscious biases using validated tools such as the Harvard Implicit Association Tests, and by reflecting on situations where these biases might influence their behavior. Developing a conscious process to recognize and mitigate these biases is a key step toward building equitable relationships.

In fostering trust, mentors are encouraged to demonstrate honesty and transparency – such as acknowledging when they do not have a complete answer – and to show up authentically in the relationship. Trust is further strengthened by actively listening to mentees’ needs, documenting those needs for future follow-up, and responding with empathy when mentees share personal experiences. These actions can help mentees feel seen, heard, and supported.

Additionally, competencies in this domain help mentors recognize the ways in which their own backgrounds and experiences may differ from those of URSW mentees, setting the tone for open communication and mutual respect. This includes asking about the mentee’s background, discussing how their paths and identities may differ, and reflecting on how the mentee’s preparation or confidence might vary from what the mentor experienced at a similar stage. These competencies are essential for establishing the trust needed for mentees to feel comfortable sharing their challenges and aspirations, ultimately fostering a more inclusive mentoring environment. By embracing these foundational practices, mentors lay the groundwork for a relationship rooted in mutual respect and psychological safety – conditions essential for meaningful support and growth.

B. Science: empower engagement and develop the mentee’s desired scientific skills

The Science domain focuses on equipping mentees with essential skills for academic and scientific success. Competencies within this domain guide mentors in assessing mentees’ scientific abilities, identifying practical barriers to engagement, and creating growth opportunities tailored to each mentee’s needs. For example, mentors are encouraged to ask directly about potential barriers – such as financial strain, transportation, or caregiving responsibilities – and to consider how these factors may influence the mentee’s participation in research activities, conference travel, or lab attendance. In some cases, this may involve connecting mentees with support services or considering alternatives to standard processes, such as up-front reimbursement for travel costs.

Mentors are also encouraged to build intentional opportunities to observe and assess the mentee’s scientific skills, including their ability to interpret literature, write, present, and analyze data. These assessments should extend beyond technical ability to include personality style and broader aptitudes. Understanding a mentee’s current skillset creates the foundation for equitable support – mentors can then individualize their feedback, adapting their approach to match the mentee’s level and goals. For instance, mentors might provide high-level feedback on writing to guide revision before offering line edits or recommend resources such as writing tutors or scientific editors. For mentees with less public speaking experience, mentors can encourage oral practice sessions with structured feedback, being mindful not to interrupt in real time and instead offering holistic comments afterward, including on presentation style as well as content.

Finally, mentors should actively offer opportunities that align with the mentee’s scientific interests and career goals, such as inclusion in projects, papers, and grants. When opportunities are presented, it is important to clarify expectations by clearly distinguishing between optional opportunities and required tasks to ensure that mentees feel empowered, not obligated. Collectively, practices in this domain support equitable skill development, enabling mentees to achieve success regardless of their starting points. Training programs can use these competencies to structure skill-building activities and ensure that mentors actively support the scientific development of URSW mentees.

C. Career: foster the mentee’s career independence and success

The Career domain provides specific strategies for mentors to support mentees in navigating academic careers. Of note, competencies in the Career domain that require interaction with others (10 and 11) are impacted by the Overcoming Bias domain.

A key focus in this domain is demystifying the mentor’s own career path. In our survey, strong endorsement for demystifying career paths underscores the importance of mentors sharing their professional journeys, including the role of luck, missteps, and gaps in knowledge along the way. By sharing both successes and challenges, mentors can normalize the non-linear nature of academic careers, helping to mitigate imposter syndrome and isolation for scholars who lack access to informal networks where these realities are more openly discussed [Reference Balls-Berry, Orellana, Enders and DSouza53]. Our earlier pilot study on the hidden curriculum needs of predoctoral students similarly highlighted how transparency in career planning and trajectory from mentors was crucial to learning how to navigate academic systems and hierarchies [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry3,Reference Enders, Golembiewski, DSouza, Martin and Kennedy9], suggesting that vicarious learning plays a large role in uncovering the hidden curriculum for URSW trainees [Reference Williams, Thakore and McGee54].

Mentors can also support career development by modeling professional communication practices. For example, they may choose to explain why they use certain language or include (or omit) specific individuals in professional emails, or how they adjust tone and behavior across settings. These insights can offer mentees critical, often unspoken, context for navigating professional norms. In addition, mentors are encouraged to provide tailored sponsorship – suggesting the mentee for opportunities that align with their goals and offer manageable stretch experiences. When approached about a mentee’s suitability for an opportunity, mentors should assess the request carefully, and when in doubt about the mentee’s bandwidth, consider inviting the requestor to ask the mentee directly. Supporting mentees can also include advocating for necessary resources or nominating them for awards, while pausing to reflect on any hesitation – asking, for example, “Would I wait to nominate another trainee?”

Finally, competencies in this domain stress that mentors can play a powerful role in broadening the mentee’s professional network. This includes actively introducing the mentee to senior colleagues, offering words of endorsement in those introductions, and including the mentee in high-level conversations within and beyond the institution. Exposing mentees to professionals in their intended career paths can help them better understand both the structure and daily realities of those roles. Together, these actions provide mentees with access to professional social capital, a critical but often hidden component of academic advancement.

D. Overcoming bias: support the mentee in the context of bias

The Overcoming Bias domain addresses the systemic and interpersonal barriers that URSW mentees may encounter in academic settings. This domain prepares mentors to identify and address unconscious biases, microaggressions, and exclusionary behaviors. Competencies in this domain emphasize the mentor’s role as an ally, empowering mentors to actively advocate for mentees and create a more inclusive environment. For example, mentors are encouraged to become familiar with patterns such as the “prove-it-again” and “tightrope” biases, and to name common disparities in the quality, frequency, and tone of feedback historically minoritized individuals receive. Similarly, mentors can learn to recognize and avoid gendered or racialized language in recommendation letters, such as describing women as “helpful” or “charming” in contrast to “analytical” or “brilliant.”

Competencies in this domain also support mentors in identifying and addressing microaggressions and exclusionary language. Mentors are encouraged to develop upstander skills and to intervene – publicly or privately – as appropriate. Acting as an ally includes elevating the mentee’s work and contributions without diminishing their independence or authority. Equally important is preparing mentees to lead in environments shaped by implicit bias. Mentors can support this by discussing the cues they themselves use to demonstrate leadership, helping the mentee explore which of these strategies may be effective and authentic for them.

Finally, mentors are encouraged to attend to signs that a mentee may be experiencing a lapse in confidence. This includes checking in even when the mentee appears outwardly self-assured, offering encouragement grounded in honesty and integrity, and inviting the mentee to reflect on what has helped rebuild confidence over time. These practices contribute to a mentoring relationship that not only acknowledges bias but actively works to counter its effects. Training programs should monitor mentors’ progress in this domain and consider reassignment if a mentor consistently fails to address bias, as mentees may require such support to succeed.

Collectively, these domains offer a comprehensive structure that is more than guidance – rather, it serves as an actionable framework for equipping mentors to provide equitable, individualized support. Ultimately, a mentor training program rooted in this framework should serve as a “resource node” within a broader ecosystem of mentoring models [Reference Montgomery55], providing consistent, structured support to URSW scholars while allowing for individualized mentorship approaches.

Differences in how URSW and majority of survey respondents prioritized certain competencies further underscore the need for tailored mentorship approaches. URSW respondents placed greater emphasis on expanding research networks and understanding mentees’ unique perspectives. This suggests that mentors should move beyond a “one size fits all” approach and instead develop individualized strategies that address specific challenges their mentees face. To achieve this, mentorship programs should encourage ongoing self-reflection and active listening to better understand mentees’ lived experiences in order to align their support with an individual mentee’s goals and circumstances.

Finally, our work significantly expands on the competencies addressed in two widely used mentorship evaluation instruments: the Mentoring Competency Assessment (MCA) and Mentor Role Inventory (MRI). In addition to adapting several existing items for mentoring across diversity, our framework introduces five unique competencies (4, 8, 9, 12, and 13), broadening the scope of the scientific mentorship literature. Competency 4, which focuses on identifying and addressing practical barriers to a mentee’s engagement in science, lays the foundation for the remaining competencies in the Science domain. Competencies 8 and 9, by guiding mentors to demystify their own career success and explain how they adapt their behavior across settings, support the mentor in offering a roadmap and hazard signs to aid the mentee in the Career domain. Competencies 12 and 13 prompt mentors to become aware of potential barriers the mentee may encounter and to develop their own ability to identify microaggressions, preparing mentors to support mentees effectively in the Overcoming Bias domain. Additionally, Competency 15 introduces a novel focus on helping mentees develop personalized leadership strategies in the face of potential bias, equipping URSW mentees with essential career skills. Notably, many of these competencies are positioned at the beginning of their respective domains within the framework, suggesting that these foundational tools could significantly enhance current mentorship training efforts and programs.

Limitations

There are limitations to this work. The survey was disseminated to professionals already committed to diversity initiatives, who are more likely to volunteer for DEIA research [Reference Jimenez, Laverty, Bombaci, Wilkins, Bennett and Pejchar56]. This may have introduced bias toward affirming the importance of these competencies. To mitigate this in future research, expanding the sample to include mentors with varying levels of DEIA engagement would provide broader perspectives. The definition of URSW we used in the demographics section of the survey included women, precluding separation of this group from other URSW groups. In addition, the sample size was small, though 82% of respondents met criteria for URSW, reflecting diverse perspectives, and suggesting that most respondents had personal experience uncovering hidden curriculum topics themselves.

Future directions

These competencies may serve as new tools to guide and evaluate mentorship within translational science. While the competencies themselves are new, there are many strong models available to inform both the evaluation of mentorship training programs [Reference Feldman, Steinauer and Khalili20–Reference Pfund, House and Asquith22,Reference McGee, Blumberg and Ziegler27,Reference House, Byars-Winston, Eiring, Hurtado, Lee and McGee31,Reference Pfund, Sancheznieto and Byars-Winston33,Reference Johnson and Gandhi57] and the validation of mentorship and clinical research competencies more broadly [Reference Fleming, House and Hanson46,Reference Robinson, Switzer and Cohen58,Reference Hornung, Ianni, Jones, Samuels and Ellingrod59]. These frameworks provide a solid foundation for developing rigorous, evidence-based approaches to assess the effectiveness of mentorship practices in supporting diverse scholars.

We anticipate that tools for mentors and mentees will offer different insights, with mentors’ responses reflecting intent and mentees’ feedback demonstrating impact. Because mentees have varied needs and experiences, the influence of a given mentor may also differ across mentoring relationships. In addition, future work should validate these competencies with mentor-mentee pairs where the mentee has at least one URSW characteristic not carried by the mentor. While formal validation remains a priority, the overwhelmingly positive feedback from DEIA experts during our development process encouraged us to share these competencies now, with the hope that others may adapt, refine, and expand upon this work.

Conclusion

The “Hidden Curriculum Competencies for Scientific Mentors” offers a novel and comprehensive conceptual framework for mentoring URSW scholars in academic medicine and science. By addressing both the personal and professional needs of their mentees, mentors can foster a more inclusive and supportive academic environment where all scholars have the opportunity to thrive. By equipping mentors to address the impact of the hidden curriculum on URSW scholars, this framework has the potential to not only enhance individual mentoring relationships but also contribute to broader institutional goals of improving retention rates and fostering a supportive, diverse academic community. Implementing these competencies within mentor training programs offers institutions an opportunity to develop a more inclusive and resilient scientific workforce. In this way, the framework serves as a critical tool for advancing equity in academic medicine and ensuring all scholars can reach their full potential.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the survey respondents for taking the time to complete and comment on this survey. Your efforts were fundamental to the finalization of these novel competencies for mentoring across diversity.

Author contributions

Felicity Enders: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Elizabeth Golembiewski: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Karen DSouza: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Lisa Burton: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Audrey Elegbede: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Rahma Warsame: Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing.

Funding statement

This publication was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.