1. Contextualization

Impersonal strategiesFootnote 1 are strategies in which the first argument is not grammatically expressed or performs a pleonastic function only.Footnote 2 It is, in truth, semantically empty, whether marked or unmarked (compare Siewierska Reference Siewierska, González, Lachlan Mackenzie and González Álvarez2008). In other words, impersonal strategies can be defined as strategies that contain no referential first argument (Malchukov & Siewierska Reference Malchukov and Siewierska2015:20). Mazzitelli (Reference Mazzitelli2019:32) refers to these kinds of strategy as “agent-defocusing constructions.” From the literature (e.g., Gast & van der Auwera Reference Gast, van der Auwera, Bakker and Haspelmath2013, Siewierska & Papastathi Reference Siewierska and Papastathi2011), we know that there are two main types of contexts that such strategies can be used for. Universal contexts, such as one only lives once, involve a generic first argument that can be paraphrased as ‘everyone, anyone’. Existential ones, like my car has been stolen, have a specific but unidentified (group of) individual(s) as their first argument, which can be paraphrased as ‘someone, some people’. Further distinctions within these types can be made but they will be discussed in more detail in section 2.

Much recent research has been concerned with impersonal strategies (e.g., Kitagawa & Lehrer Reference Kitagawa and Lehrer1990, Luukka & Markkanen Reference Luukka, Markkanen, Markkanen and Schröder1997, Egerland Reference Egerland2003, Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2010, Primus Reference Primus2011, Siewierska & Papastathi Reference Siewierska and Papastathi2011, Gast & van der Auwera Reference Gast, van der Auwera, Bakker and Haspelmath2013, Kirsten Reference Kirsten2016, Van Olmen & Breed Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018a, Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b, Mazzitelli Reference Mazzitelli2019, Van Olmen et al. Reference Van Olmen, Breed and Verhoeven2019, Schlund Reference Schlund2018, Reference Schlund2020, Breed & Van Olmen Reference Breed, Chan and Van Olmen2021a, Prenner & Bunčić Reference Prenner and Bunčić2021, Bauer Reference Bauer2021, Groenen Reference Groenen2021). It has, however, mainly focused on a fairly limited number of strategies such as pronominal ones (e.g., one) and passives (e.g., has been stolen). Few studies have tried to examine the range of impersonal strategies that are available to speakers and/or determine which of the strategies they prefer in different impersonal contexts. Two exceptions to this gap in the research are Siewierska’s (Reference Siewierska, González, Lachlan Mackenzie and González Álvarez2008) investigation into pronominal versus verbal impersonal strategies, although her work is primarily based on grammatical descriptions and input from a small set of informants, and Bauer’s (Reference Bauer2021) investigation of the impersonal strategies in six Slavic languages, based on a parallel corpus. Bauer identifies no less than eighteen distinguishable strategies for impersonalization in these six Slavic languages. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic analysis of the variety of impersonal strategies in extensive West-Germanic language data.

Impersonal strategies have thus far been examined using: (i) grammars, often in combination with first-language-speaker judgments (e.g., Siewierska & Papastathi Reference Siewierska and Papastathi2011, Gast & van der Auwera Reference Gast, van der Auwera, Bakker and Haspelmath2013); (ii) corpora (e.g,. Marin-Arrese et al. Reference Marin-Arrese, Martínez-Caro and Pérez de Ayala Becerril2001, Primus Reference Primus2011, Coussé & van der Auwera Reference Coussé and van der Auwera2012, Schlund Reference Schlund2020, Bauer Reference Bauer2021); and (iii) language-based questionnaires (e.g., Siewierska Reference Siewierska, González, Lachlan Mackenzie and González Álvarez2008; Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Sallandre, L’Huillier and Aksen2018, Prenner & Bunčić Reference Prenner and Bunčić2021). These methods suffer from a number of shortcomings if one wants to study the range of impersonal strategies in a language (see Breed & Van Olmen Reference Breed, Chan and Van Olmen2021a). They are, for one, generally deductive in that they take a predetermined set of strategies as their point of departure (e.g., a questionnaire then asking for acceptability judgments about them). Admittedly, parallel corpora do not have this drawback: a trigger in the source language (e.g., German man ‘one/they’ in Gast Reference Gast2015 and Bauer Reference Bauer2021) may be rendered in the target language(s) in a non-predetermined variety of ways. Still, results may be affected by interference from the source language and/or the translation process (see Schlund Reference Schlund2020:56, Bauer Reference Bauer2021:153-156). Moreover, parallel corpus studies share the problem with corpus research in particular that some impersonal contexts are quite rareFootnote 3 in text collections (e.g., those tied to the here and now of the situation; see section 2) – making it difficult to find out which strategies are used in them. Questionnaires in turn often have the disadvantage that they limit the replies that participants can give (e.g., a completion task where the subject slot in … has/have stolen my car allows someone and they but not a passive).

The present article aims to argue for a new way of investigating impersonal strategies that would make it possible to identify their variety in different impersonal contexts and demonstrate which ones are preferred in these contexts and that thus complements the other approaches. More precisely, it discusses a visual questionnaire completed by speakers of Dutch and Afrikaans and thus seeks to (i) determine whether this method is a satisfactory way of studying impersonal strategies and (ii) examine and compare the impersonal strategies of Dutch and Afrikaans. The rest of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 briefly introduces the impersonal contexts distinguished in the questionnaire. In section 3, we explain the method and the design of the visual questionnaire in more detail and, in section 4, we discuss its results for Dutch and Afrikaans. Section 5, finally, is the conclusion.

2. Impersonal Contexts

The visual questionnaire distinguishes twelve different impersonal contexts. They are based on Van Olmen & Breed’s (Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b) semantic map, which itself combines criteria that feature in Siewierska & Papastathi’s (Reference Siewierska and Papastathi2011) and Gast & van der Auwera’s (Reference Gast, van der Auwera, Bakker and Haspelmath2013) semantic maps. As can be expected from semantic maps, all distinctions are motivated by cross-linguistic variation (e.g., the context in they say that the house is haunted differs from that in they have stolen my car since some languages accept the third person plural in the one but not the other). An in-depth discussion of this evidence is beyond the scope of the present article but can be found in the aforementioned sources.

The twelve contexts, which are exemplified below, can be distinguished from each other based on seven parameters: (i) quantification; (ii) perspective; (iii) veridicality; (iv) modality; (v) (un)knownness; (vi) number; and (vii) speech act. These parameters will now be discussed one by one, with reference to the examples.

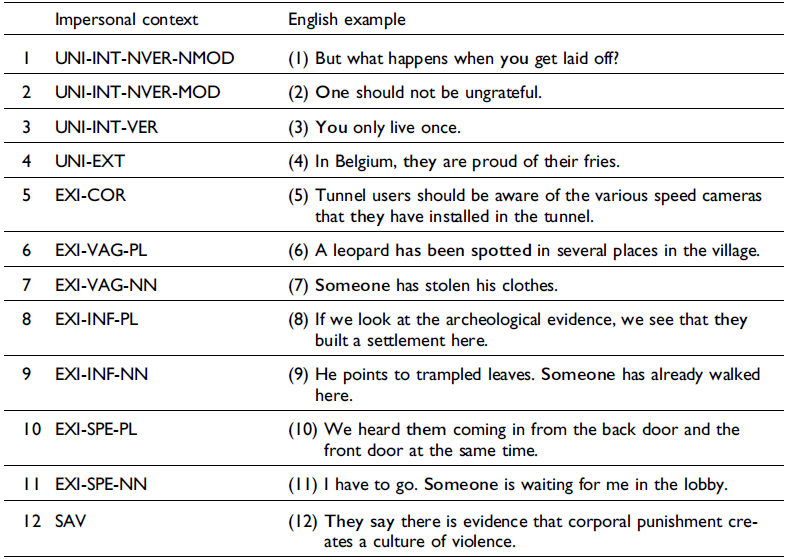

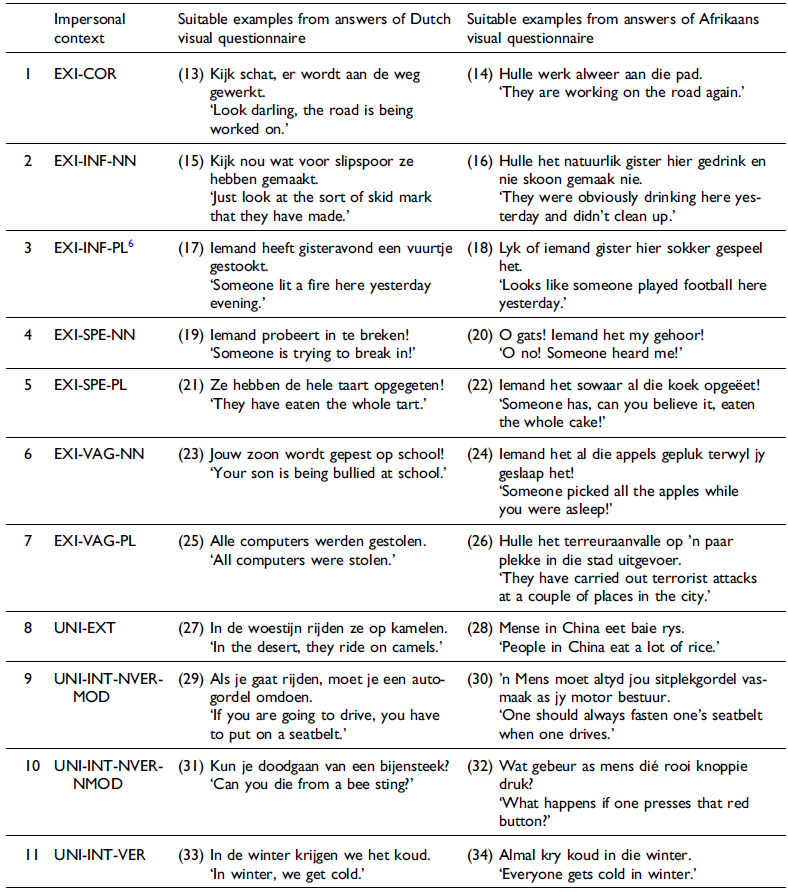

Quantification involves the distinction introduced in section 1 between universal (UNI) and existential (EXI) uses. The former apply to everyone contextually relevant, as in (1) to (4) in table 1, while the latter concern one or more particular but unidentified individuals, as in (5) to (12).

Table 1. Twelve distinguishable impersonal contexts

Perspective is a parameter that differentiates universal uses and centers, in essence, around the (non)inclusion of the speaker and the addressee in the set. A universal use that applies to speaker and addressee too, as in (1) to (3), has an internal (INT) perspective. One with an external (EXT) perspective excludes them, as in (4). This sentence is a statement about all people in Belgium, but the speaker and the addressee clearly do not belong to this group (cf. we/you are proud of our/your fries in Belgium).

Veridicality distinguishes universal-internal uses from each other and involves the presentation of the state of affairs as real or not. Example (3) is veridical (VER) since only living once is given as a fact (of life). Examples (1) and (2), however, are nonveridical (NVER): getting laid off is presented as being in the realm of the hypothetical and being ungrateful as being in the realm of the undesirable.

Modality further differentiates nonveridical universal-internal uses. If nonveridicality is expressed by some overt modal element, the use is modal (MOD). The auxiliary should in (2) is a case in point. If nonveridicality is conveyed by other means (e.g., the interrogative nature of the sentence), the use is nonmodal (NMOD). In (1), for instance, the nonveridicality comes not from a modal element but from the conditional character of the subordinate if-clause.

(Un)knownness is a parameter that pertains to existential uses. It has to do with the amount and type of information that is available about the particular but unidentified (set of) individual(s). Four distinctions are made here. First, in partially known or so-called corporate (COR) uses, it is relatively clear in a way from the state of affairs itself who is responsible for it, even if they are not explicitly named. Typically, they are some kind of institutional entity – hence, the term “corporate.” In (5), for example, the state of affairs of installing speed cameras is something that can only really be realized by the police and/or the agency in charge of road signs and the like. Second, in vague (VAG) uses such as (6) and (7), the speaker really knows about the event being described but is not able or willing to identify the particular person or people responsible for it. Third, in inferred (INF) uses like (8) and (9), the speaker does not have any actual direct knowledge of the event. They deduce its existence from other evidence available to them and then also assume that some unknown person or people must be behind it. In (8), for instance, the speaker infers from the archeological data that there was at some point a settlement where they are and thus also that some community building it must have existed. Fourth, SPE uses refer to a specific point in time (see Siewierska & Papastathi Reference Siewierska and Papastathi2011:582). In examples such as (10) and (11), the speaker is in the same place and time as the individual(s) realizing some event there and then and may thus have strong suspicions about who they are but is still not explicitly identifying them. In (11), for example, there is a person currently waiting for the speaker, who probably knows who this individual is but chooses not to name them in their utterance.

Number as a parameter intersects with the vague, inferred, and specific existential uses (not with the corporate ones, though, since they are inherently plural, involving entities like the government, the hospital and so forth). In each of these three contexts, we can have a state of affairs that necessarily involves more than one person – as in (6), (8), and (10). These examples are, in other words, plural (PL). We can, however, also have a state of affairs in each context that may be realized by one or more than one individual – as in (7), (9), and (11). These examples are thus number-neutral (NN).

Speech act verb (SAV), lastly, sets apart one particular impersonal context from all others. It involves the presence of a speech act verb that fulfils an evidential function in the sentence, like say in (12). The speaker here attributes a claim to an unspecified set of people.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire

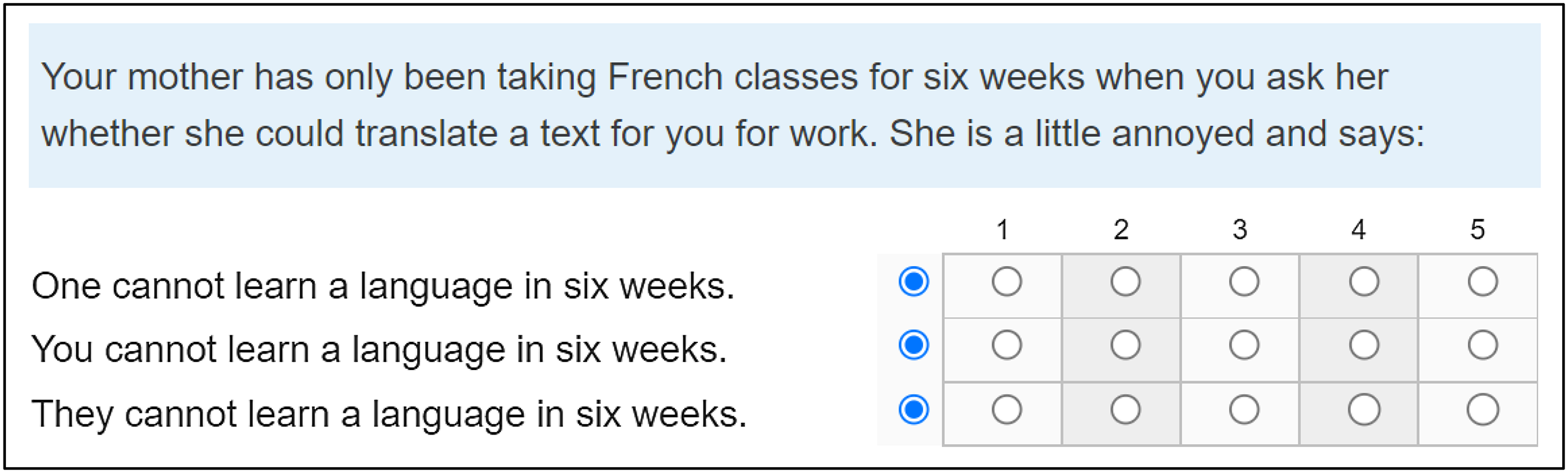

As discussed in section 1, current methods may not be entirely suitable for identifying the full range of impersonal strategies in a language, or for determining the preferred strategies in different impersonal contexts. Let us illustrate this point here in more depth, with a look at Van Olmen & Breed’s (Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018a, Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b) methodology. They adopted a “double questionnaire-based approach” to study impersonal strategies in West Germanic. A first group of first language speakers of English, Dutch, and Afrikaans were given an acceptability judgment questionnaire (see figure 1), and a second group a completion task questionnaire (see figure 2).

Figure 1. Acceptability judgment stimulus for UNI-INT-NVER-MOD (Van Olmen & Breed Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b).

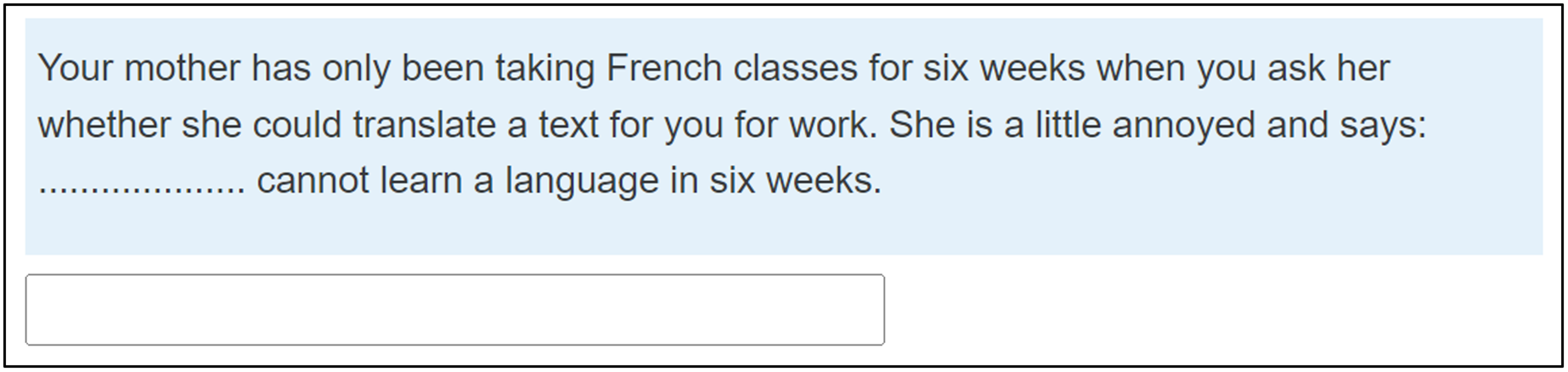

Figure 2. Completion task stimulus for UNI-INT-NVER-MOD (Van Olmen & Breed Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b).

Both questionnaires contained twenty-four stimuli (in an arbitrary order), two for each of the twelve impersonal uses distinguished in section 2. Figures 1 and 2, for instance, present one of the two universal-internal nonveridical-modal stimuli. The first questionnaire invited the respondents to assess the acceptability of a number of impersonal strategies as a way to complete the scenario described above, on a five-point scale where one stands for very unacceptable and five for very acceptable. The list of impersonal strategies to be judged only contained a limited set of pronominal ones, however (see one, you, and they in figure 1). As a result, we do not know how their acceptability would compare to other potential “solutions” like people cannot learn a language in six weeks. The second questionnaire was intended to address this issue and asked respondents to fill in the subject slot of the final sentence of each stimulus themselves. As figure 2 shows, this approach did allow respondents to use not only one and you but also people for UNI-INT-NVER-MOD contexts. The sentence with the blank excluded a whole range of other conceivable answers, though – like negative indefinite nobody can learn a language in six weeks, nonfinite learning a language in six weeks is impossible or passive a language cannot be learnt in six weeks. In fact, one respondent seemed to feel so strongly about the passive for one of the stimuli in the completion task that they simply ignored the structure of the sentence to be completed.

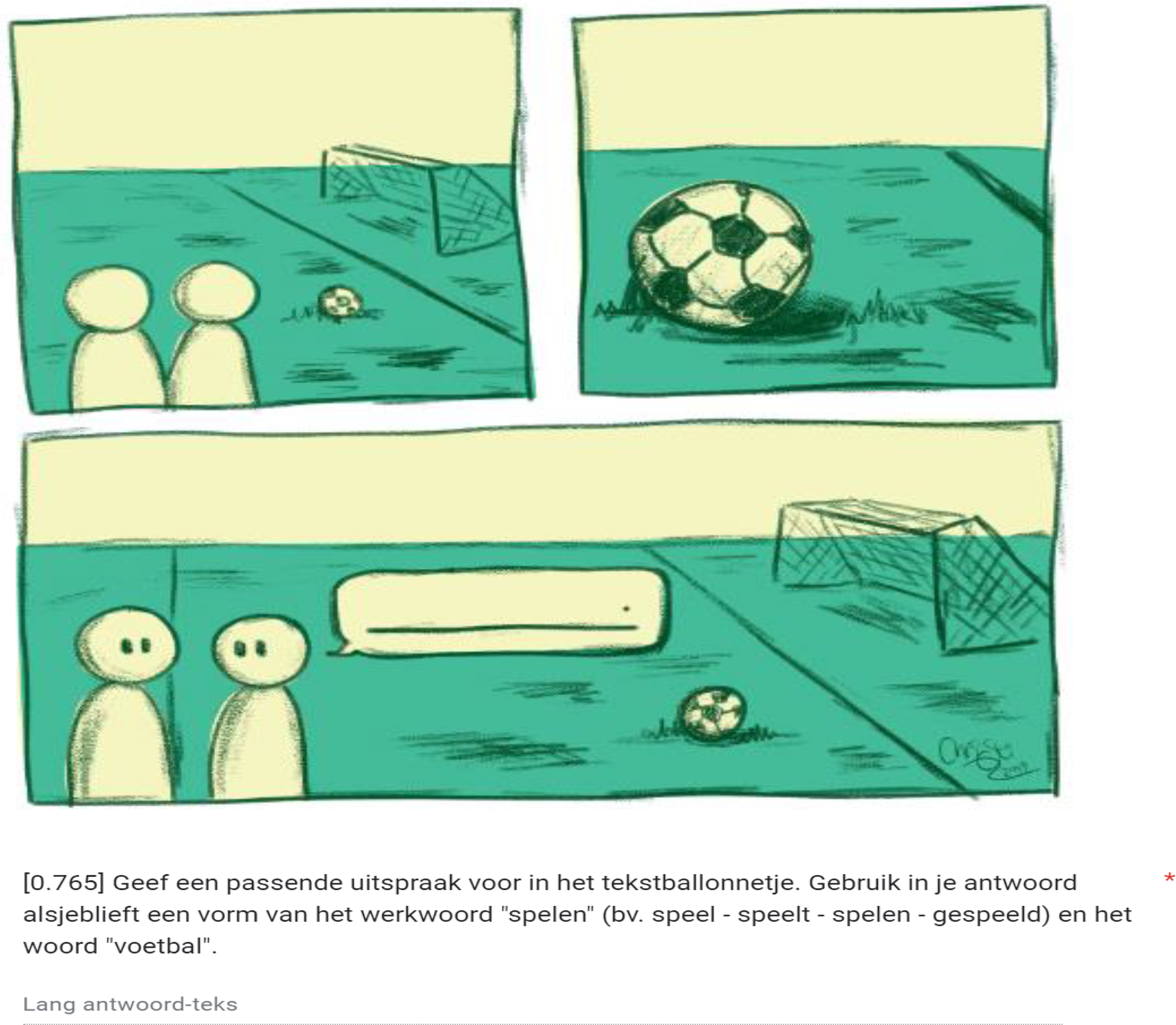

Despite the problems with the above methods, a questionnaire-based approach still has considerable promise for a study of the variety of impersonal strategies in a language. The reason is that, unlike corpus research, for example, it enables us to examine, through targeted stimuli, impersonal contexts that do not occur very often in usage. The method adopted in the present article therefore sticks with presenting respondents with a scenario for all twelve impersonal uses that prompts them to complete it with an impersonal strategy. The scenarios are, however, given not as descriptions, as in figures 1 and 2, but as visual representations, as in figure 3.Footnote 4

Figure 3. Visual questionnaire stimulus for EXI-INF-PL (“Give an appropriate utterance for the speech bubble. Please use a form of the verb ‘play’ (e.g., play, plays, played, playing) and the word “football” in your answer.”)

To obtain as many useful answers as possible, we instructed the participants to provide a specific type of response on the opening page of the questionnaire. The instructions explicitly stated that their answer should be focused on people in general or individuals that they do not know or cannot identify. Therefore, responses that were only related to the participant themselves, or to a specific person or group, were discouraged.

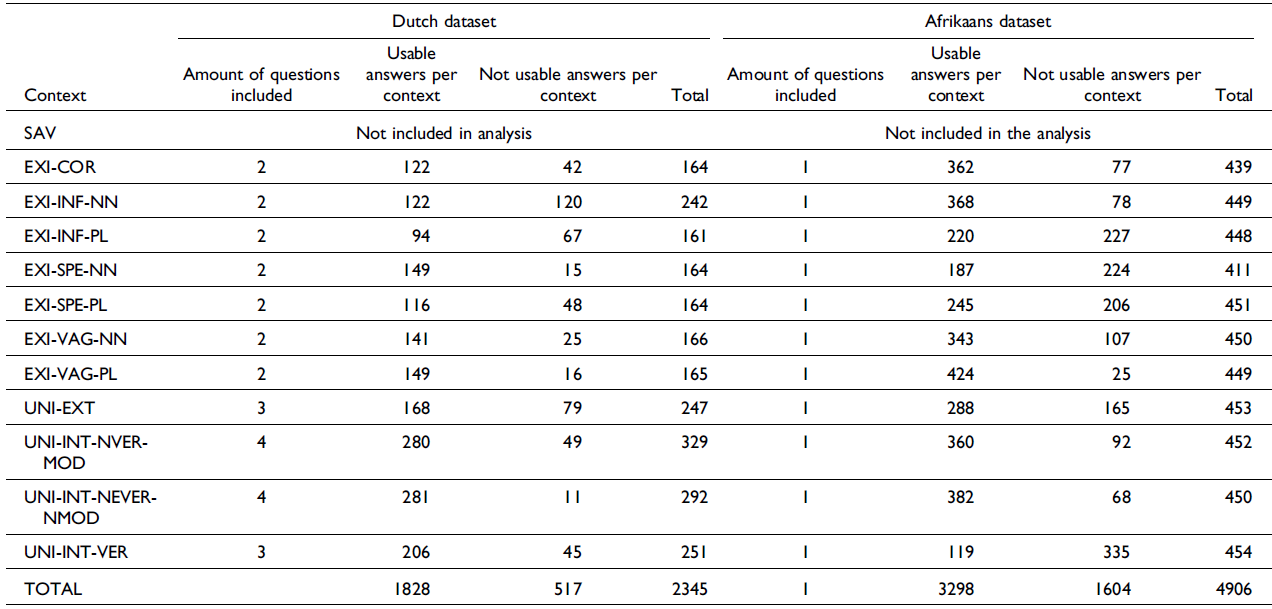

In addition to these instructions, we also incorporated visual cues and prompts to further guide the respondents towards providing useful answers. These visual stimuli were accompanied by indications of the type of response that was expected. They mostly constitute requests that respondents use a specific verb or sometimes also a specific adverb or noun to complete a scenario, as can be seen in figure 3 with spelen ‘play’ and voetbal ‘football’ and in the rest of the questionnaires, which are accessible online.Footnote 5 Even with such indications, however, the stimuli for the speech act verb use (e.g., ‘it is said that this house is haunted’) have proven to be inadequate, with too many irrelevant answers, and are therefore not discussed in the remainder of this article. For the other eleven uses, examples (13) to (34) in table 2 illustrate suitable answers actually offered by our respondents.

Table 2. Examples of responses for each impersonal context from the Dutch and Afrikaans questionnaires

3.2. Dataset

The visual questions in the Dutch and Afrikaans questionnaires were identical, but the textual explanation for each question was translated into the language of the questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed via social media. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. A total of 83 first language speakers of Dutch ended up completing the questionnaire for their language. For the Afrikaans questionnaire, we managed to get no less than 454 first language speakers to fill it out. Because of this discrepancy between the two languages and the amount of data for the latter in particular (more than 10,000 data points), we analyzed all of the data for Dutch but only the responses for one visual stimulus for each impersonal use for Afrikaans. The Afrikaans data has been reported on already, in Breed & Van Olmen Reference Breed, Van Olmen and Chan2021b, but is included here nonetheless as a basis for comparison with the results for Dutch. An overview of the data is given in table 3. It presents, for each impersonal context (see the leftmost column): (i) the number of stimuli taken into consideration here (e.g., for Afrikaans, always just one); (ii) the number of irrelevant answers; (iii) the number of relevant answers; and (iv) the total number of answers.

Table 3. Overview of the visual questionnaire data for Dutch and Afrikaans

A few comments are in order here. First, the totals do not always add up to the same number, since not all respondents completed all questions and some impersonal uses were tested more than two times for Dutch. The higher numbers of stimuli for certain uses are an artifact of the questionnaire development (see footnote Footnote 4). Each designer was asked to create a stimulus for at least one existential context – with eight to choose from – and at least one universal context – with just four to choose from. As a result, more stimuli were produced for universal uses. Second, the so-called irrelevant answers include not only those that cannot be considered as impersonal in any way but also those that may be impersonal but do not actually fit the impersonal use that the stimulus sought to test. An example would be an Afrikaans clause with mens ‘one’, which is exclusively universal-internal (see Van Olmen et al. Reference Van Olmen, Breed and Verhoeven2019), for a stimulus looking for existential impersonal strategies). Third, for the relevant answers, we did not exclude those possibly ambiguous between an impersonal and a nonimpersonal reading. Dutch clauses with the pronouns ze ‘they’ or je ‘you’, for instance, could be taken to refer to a known group of people or an addressee respectively, but they can have an impersonal interpretation too and are thus taken into account as relevant here. Fourth, given the open-ended nature of the questionnaires and the complexity of the domain under investigation, it is not unsurprising that there are so many irrelevant answers. Still, we have a sufficient amount of relevant ones for both languages and all impersonal contexts to study their variety in impersonal strategies in Section 4. Fifth, and finally, the quantitative differences in the answers between Dutch and Afrikaans pose no significant problem, since we do not explicitly seek to compare the frequencies of impersonal strategies in the two languages.

4. Results

In this section, we first offer an overall picture of the findings of our visual questionnaires for Dutch and Afrikaans, focusing on the most frequent types of impersonal strategies (section 4.1). We then move on to a discussion of the other strategies that can be distinguished in the data (section 4.2). We end with a survey of all distinct impersonal uses and the strategies that are used for them (section 4.3).

4.1. Overall Results and Main Impersonal Strategies

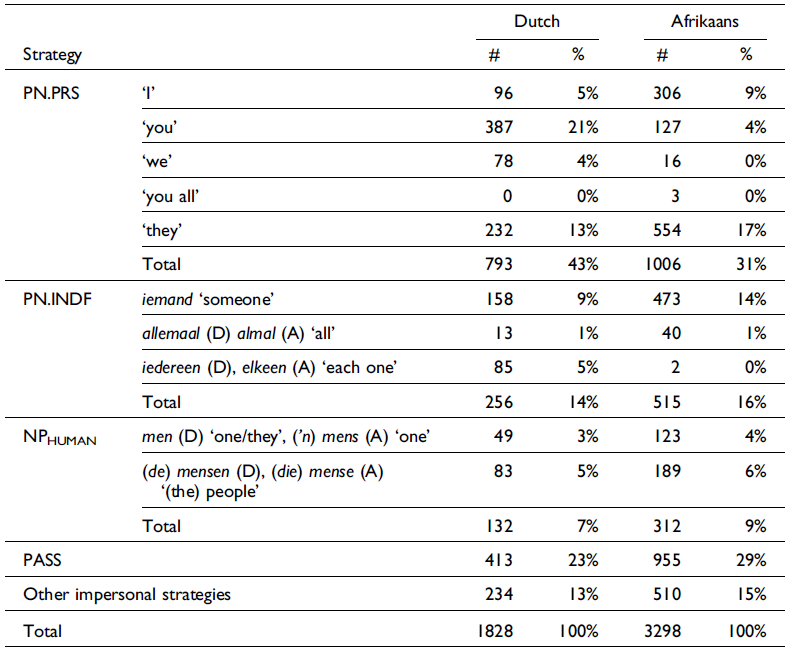

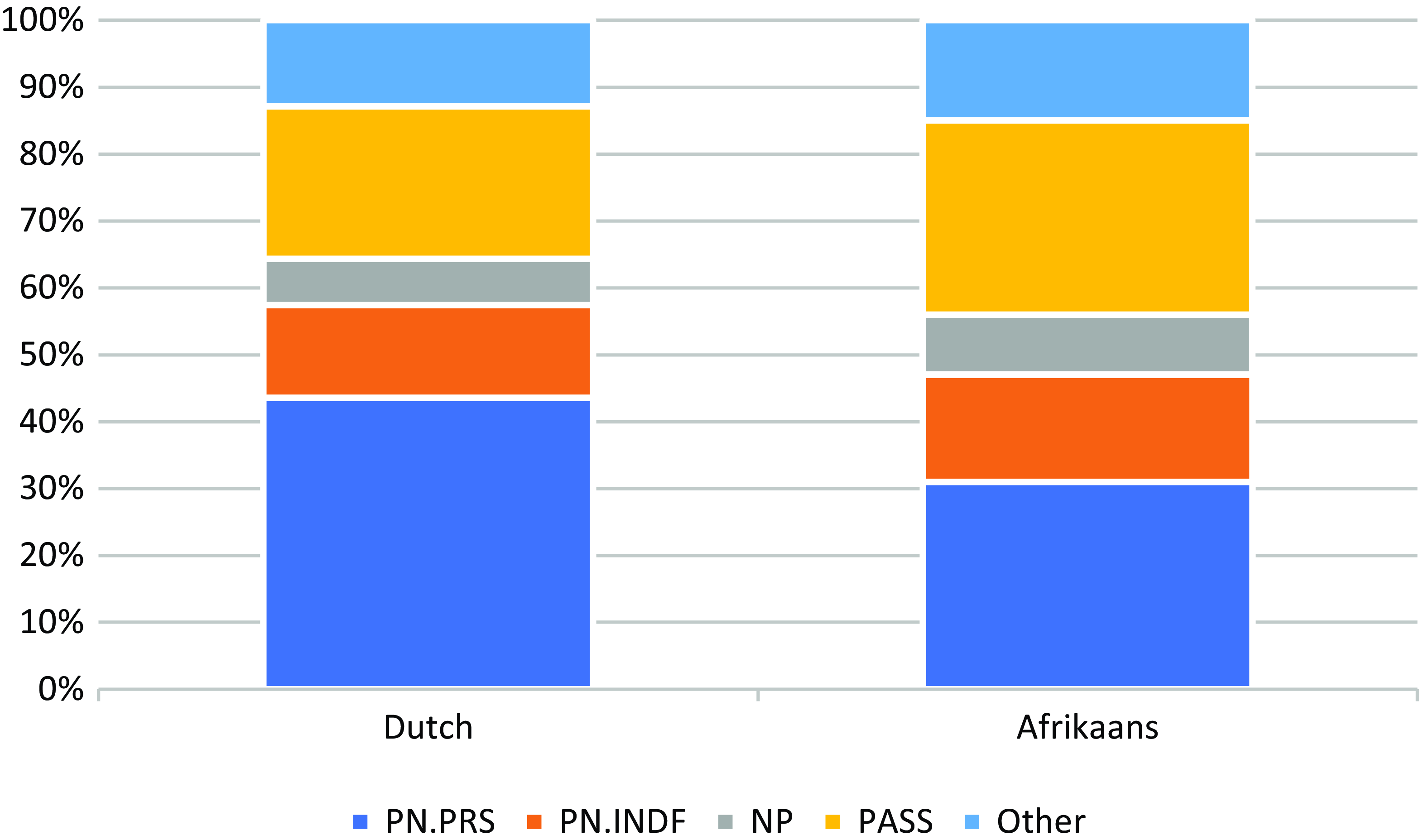

Table 4 and figure 4 provide an overview of our findings for Dutch and Afrikaans by singling out the most common impersonal strategies in the data. They are: personal pronouns (PN.PRS), indefinite pronouns (PN.INDF), nouns meaning ‘human being’ or pronouns originating from such nouns (NPHUMAN), and passives (PASS) (the remaining relevant answers are included as ‘other’). The term “main strategies” is appropriate for referring to these particular techniques, as they are frequently employed by participants and are also widely recognized as the central impersonal strategies in existing linguistic literature. In addition to these main strategies, our results also presented other impersonal strategies that have not been previously documented in existing linguistic literature. For the purposes of table 4, we will refer to these novel strategies as “other strategies,” but we will provide a detailed discussion of each of these strategies in the subsequent section. The table makes further distinctions for the first three categories (see the second column) and gives the raw (#) and relative (%) frequencies of all (sub)categories. Figure 4 presents the proportions of the main categories in graph form.

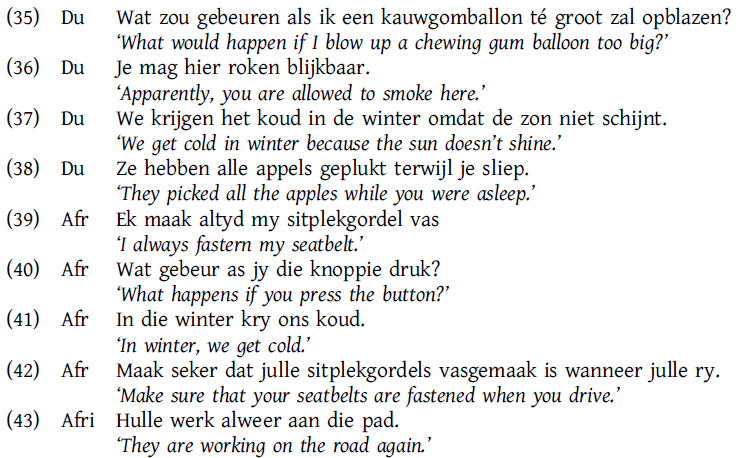

Table 4. Impersonal strategies in Dutch and Afrikaans

Figure 4. Main impersonal strategies in Dutch and Afrikaans

A first thing to observe is that personal pronouns are the most frequent type of impersonal strategy in both Dutch (43%) and Afrikaans (31%), as in (35) to (38) and (39) to (43) respectively.

Admittedly, their proportions may be somewhat inflated: strictly speaking, we do not know whether respondents intended ‘you’, ‘we’, or ‘they’ as impersonal or as referring to particular people. This ambiguityFootnote 7 is especially pertinent for ‘I’. The first-person singular is known to be able to function impersonally (e.g., Zobel Reference Zobel, De Cock and Kluge2015) but it is not unlikely that respondents actually used it to refer to the speaker.Footnote 8 Such qualifications notwithstanding, it is evident from the data that Dutch and Afrikaans are very partial to employing personal pronouns for impersonal contexts. This finding of our visual questionnaire can be seen as an independent justification and perhaps also as an explanation for much of the research’s focus on the impersonal use of pronouns such as ‘you’ and ‘they’ in Dutch and Afrikaans (e.g., Van Olmen & Breed Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018a, Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018b, Groenen Reference Groenen2021).

The passive comes out as a very common impersonal strategy too, in Dutch (23%) and in Afrikaans (29%). For respective examples, consider (44) and (45).

The passive might even prove to be more frequent than personal pronouns,Footnote 9 if we were able to identify and discard those cases in which ‘they’ and the like were not meant as impersonal. In view of its rate of occurrence in our data, it is quite interesting that the passive has received comparatively less attention in the literature on impersonal strategies than personal pronouns (but see Breed & Van Olmen 2021 on the impersonal passive in Dutch and Afrikaans, and Primus Reference Primus2011 on the impersonal passive in German and Dutch).

Indefinite pronouns make up the third largest category in Dutch (14%) and Afrikaans (16%). The questionnaire answers in (46) to (50) are cases in point.

Nouns meaning ‘human being’ and pronouns deriving from such nouns, finally, account for 7% of the Dutch answers and 9% of the Afrikaans ones. Some examples are provided in (51) to (54).

The frequency of Afrikaans (’n) mens ‘one’, compared to that of jy ‘you’, in table 4 is noteworthy. Previous research, in particular Van Olmen & Breed (Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018a), suggests that speakers of Afrikaans strongly prefer the NPHUMAN option to the second-person singular. In our visual questionnaire, however, (’n) mens essentially occurs as often (123 times, 3.73%) as jy (127 times, 3.85%). The specific stimuli may have played a role here and the choice between the two clearly deserves to be studied in more detail (Dutch behaves as expected in table 4 when it comes to men ‘one/they’ versus je ‘you’ and ze ‘they’: the NPHUMAN is much less frequent, with just 49 cases, than the second-person singular, with 329 instances, and the third-person plural, with 221 hits).

After the above overview of the most frequent types of impersonal strategies in Dutch and Afrikaans, which are also the most well-established ones in the literature, we now turn to the answers labeled as ‘other’ in table 4.

4.2. Other Strategies

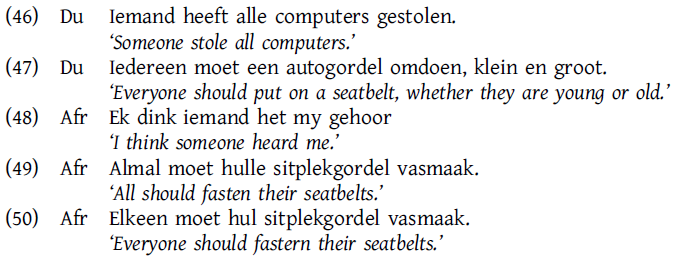

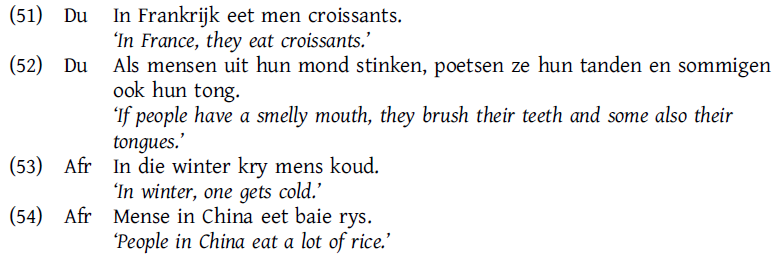

Table 5 summarizes the ‘other’ strategies. Examples and a description of each one will be presented in the following subsections. The frequencies of the various impersonal strategies used in different contexts are presented and discussed in detail in section 4.3.

Table 5. ‘Other’ impersonal strategies in Dutch and Afrikaans

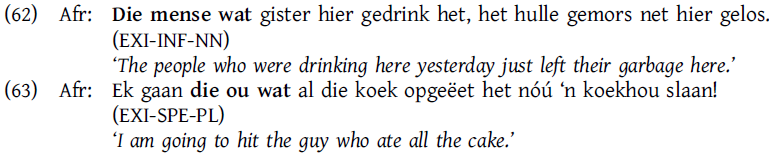

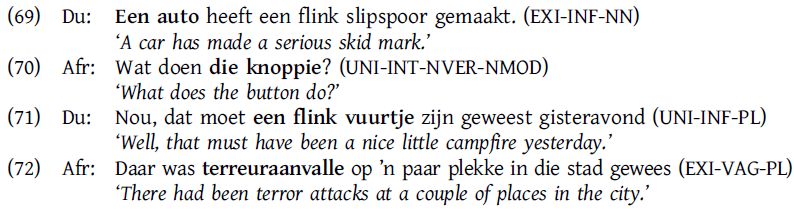

Specified nouns

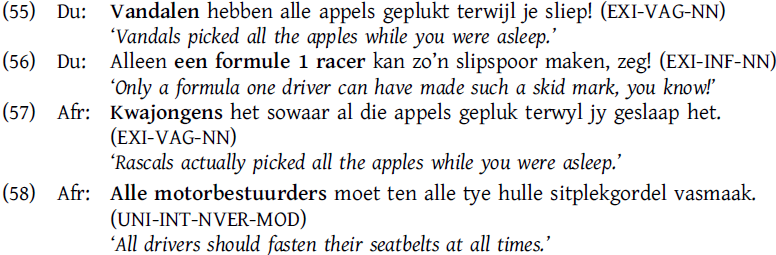

Our Dutch and Afrikaans respondents frequently used nouns that denote a typeFootnote 10 of individual but do not refer to a particular person or particular people. Moreover, these types tie in closely with the state of affairs expressed (e.g., ‘vandals’ with the act of stealing apples, ‘drivers’ with the obligation to wear a seatbelt) and, therefore, they cannot really be said to identify anyone in any more precise way. As (55) to (58) make clear, we find such nouns in universal as well as existential uses in our data.

Imperative

ImperativesFootnote 11 may typically be used to issue directives to specific addressees. However, as (59) to (61) show, they can serve to express obligations, prohibitions, permissions, and recommendations of a more generic type too, that is, ones with which anyone who somehow feels that they apply to them may comply (or not). Unsurprisingly, imperatives only occur in nonveridical universal contexts in our data and, more specifically, mostly modal ones.

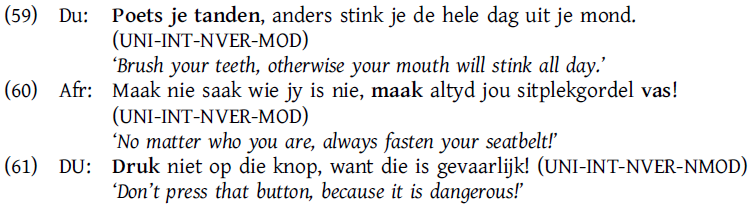

Relativization

Our Afrikaans respondents sometimes combined a definite noun with the meaning ‘human being’, like die mense ‘the people’ in (62), or closely related semantics, like die ou ‘the guy’ in (63), with a postmodifying relative clause that describes the state of affairs that the individual(s) is(/are) assumed to be responsible. Within the entire sentence, this subordinate clause can be argued to identify the referent(s) to some extent, but they are, in essence, still unknown. We only find this pattern in existential uses, since it refers to a particular (group of) individual(s) with certain characteristics.

In such cases, our Dutch respondents consistently made use of free relative clauses instead, as in (64).

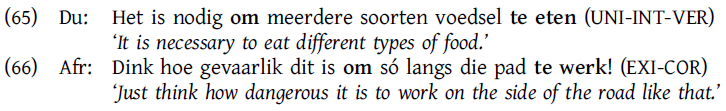

Infinitive

As nonfinite verb forms, infinitivesFootnote 12 do not require speakers to convey a first argument. They can therefore be used, not unlike passives, to present a state of affairs as impersonal by leaving it out altogether. As (65) and (66) show, the infinitive can serve this purpose in both universal and existential contexts in both languages.

Nominalization

Our respondents used nominalized verbs, which do not need the first argument to be expressed either, in the same way as infinitives. They too occur in universal uses, like het eten van rijst ‘the eating of rice’ in (67), as well as existential ones, like die gewerk aan die pad ‘the working on the road’ in (68) in both languages.

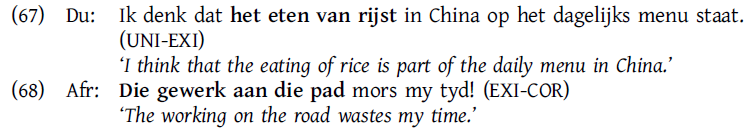

Agentive NPs

Another way that our respondents avoided an explicit impersonal first argument is by assigning a certain agency to one of the other entities involved. By utilizing this type of strategy in impersonal contexts, the respondents are able to refrain from explicitly identifying the agent of the predicate. Consequently, according to our approach, these results can also be classified as an impersonal strategy. In (69), for instance, the car may be the instrument but is portrayed as the doer of the action and, hence, the actual (unknown) doer need not be expressed. Likewise, the button in (70) is arguably the instrument (‘doing something with it’) or the patient (‘pressing it’) but is presented here as causing something itself, removing the real doer from the picture. A closely related strategy is the use of noun phrases that directly or indirectly imply the involvement of one or more human beings. For example, in (71), there can only have been a campfire if someone/some people lit it. In the same vein, the terror attacks in (72) cannot have happened without actual terrorists. As is clear from (69) to (72), we find such cases again in both universal and existential contexts.

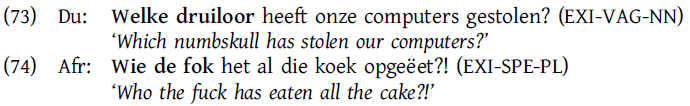

Subjective questions

Some of our visual stimuli depicted situations to which the respondents could formulate negative reactions (e.g., a reproach, an accusation, shock). For such cases, they occasionally used what may be described as “subjective questions”: they ask which specific but unknown person or people did something while evaluating them or the entire situation as negative, through the use of negatively evaluative nouns and/or expletives. These questions were limited in our data to existential uses such as (73) and (74).

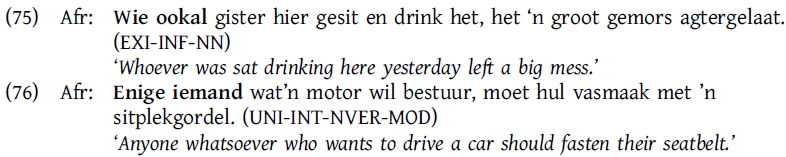

Free-choice items

Our Afrikaans respondents sporadically employed free choice items for impersonal purposes. Such items signal here that the interlocutors are at liberty to select who is intended: ‘no matter who you choose from among …’ (see Vendler Reference Vendler1967:80). With them, speakers can indicate that they do not know or, in a sense, care which particular individual(s) is(/are) responsible, as in existential (75), or that what they are saying applies to any person that you can think of, as in universal (76). We did not come across any free choice items in our Dutch data but it is perfectly possible to produce utterances such as (75) and (76) in the language.

This set of strategies does not constitute a distinct impersonal strategy, as it closely aligns with the strategy of employing indefinite pronouns in impersonal contexts (see section 4.1). However, we have chosen to still categorize these results under “other strategies” since it appears to generate a less marked response when the FCI is incorporated, in contrast to its omission. As such, we consider it a highly specific method of utilizing indefinite pronouns alongside an FCI in certain impersonal contexts. We acknowledge that additional research is necessary to gain a better comprehension of the interplay between indefinite pronouns and FCIs as impersonal strategies.

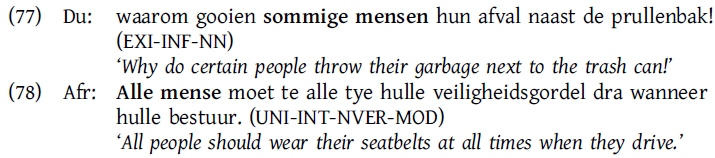

Quantifier combined with human noun phrase

Some respondents chose to make the parameter of quantification (see section 2) explicit while using a noun phrase with the meaning ‘human being(s)’. Such explication manifests itself in our data through determiners like sommige ‘certain’ for existential uses and alle ‘all’ for universal uses. Consider the respective examples in (77) and (78). Note that we only came across universal quantifiers for Afrikaans but that existential ones are an option too in the language.

This strategy is also closely related to another main impersonal strategy highlighted in section 4.1, namely NPHUMAN. However, the addition of a quantifier delineates the intended (albeit unspecified) individual or group of individuals to which the respondent is referring. As this represents an additional strategy that requires the respondent to specify the applicability of the unspecified reference, we view it as a distinct technique that warrants separate discussion.

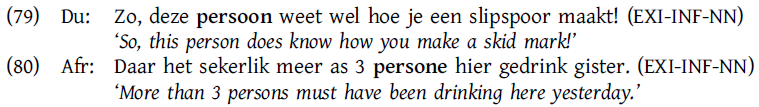

‘Person’

The noun persoon ‘person’ denotes a human being.Footnote 13 Intuitively, it would therefore be a suitable way to express an impersonal first argument – just like mens ‘human being’. Persoon is, however, only found once in Dutch (79) and once in Afrikaans (80). The relative formality of the noun may play a role here.

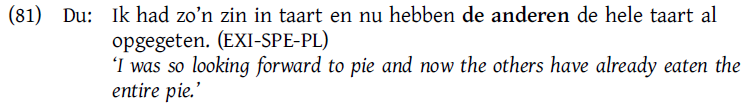

‘The others’

A (very) small number of Dutch respondents employed de anderen ‘the others’ for specific-existential contexts. As mentioned in section 2, such uses are tied to the here and now of the speech event and, as a result, the speaker may have certain ideas about who is responsible but they are still not willing or able to identify this person or these people explicitly. De anderen in (81) suggests that the speaker indeed has suspicions about who ate the tart but they cannot or will not say more than that a particular group of people not including themselves did it. Although we did not find any cases of ‘the others’ in Afrikaans, it seems perfectly acceptable in specific-existential contexts in this language too.

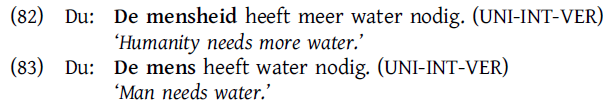

Species-generic use

For veridical universal-internal contexts, the Dutch respondents occasionally used nouns that refer to the human species in general, like de mensheid ‘humanity’ in (82) and de mens ‘man’ (lit. ‘the human’) in (83). It is important to distinguish this type of noun from the main impersonal strategy of NPHUMAN (see section 4.1). The strategy we distinguish here does not concern a grammaticalized impersonal pronoun or an indefinite set of people. Rather, the respondents are attributing something to the whole of mankind. The two strategies are obviously related, since nouns with the meaning ‘human being’ are known to start their grammaticalization process into impersonal pronouns in contexts where they have a species-generic meaning and refer to all human beings (see Giacalone Ramat & Sansò 2007). Dutch men has this origin, coming from man ‘man, human being’, and so does Afrikaans mens, which is in the process of developing into a full-fledged impersonal pronoun (see Van Olmen et al. Reference Van Olmen, Breed and Verhoeven2019) but for which it is therefore not always clear whether it has a species-generic or a truly impersonal interpretation. We therefore just included it under NPhum an.

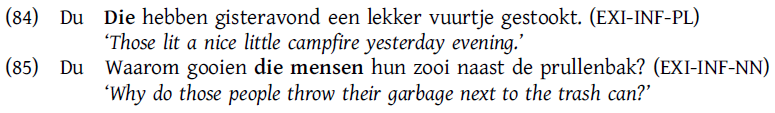

Demonstrative strategies

An at first sight peculiar answer by one of our Dutch respondents, in (84), features demonstrative die ‘those (ones)’. This item seems incompatible with impersonal contexts since its typical function is to point to a particular known rather than unknown set of referents. It is not coincidental, though, that this demonstrative is employed for an inferred-existential use. What appears to be happening here is that the speaker uses it to indicate the individuals whose inevitable existence they have deduced from the available evidence. Die in (84) can be said to point to the unknown group of people that the speaker assumes must have been there to light the fire of which the remnants are still visible. The argument that demonstratives actually fit inferred-existential contexts quite well is supported by the fact that, for those uses, our Dutch data also contains a small number of general nouns referring to humans with a demonstrative determiner, as in (85). No demonstratives were found in our Afrikaans data. The direct translations of (84) and (85) are, however, possible in this language too for inferred-existential purposes.

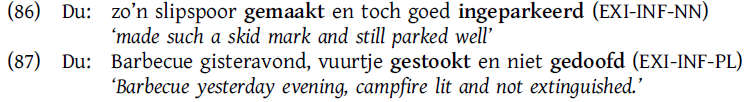

Elliptical strategies

Another (infrequent) set of answers restricted to our Dutch data is probably best described as involving ellipsis. In (86), for instance, only the past participles gemaakt ‘made’ and geparkeerd ‘parked’ are present and no subject or auxiliary is included. The result, which may very well be intended, is that it could be elliptical for a variety of other, often slightly more explicit impersonal strategies: impersonal passive (er is) een slipspoor gemaakt (lit. ‘(there is) a skid mark made’), number-neutral (iemand heeft) een slipspoor gemaakt ‘(someone has) made a skid mark’, third-person plural (ze hebben) een slipspoor gemaakt ‘(they have) made a skid mark’. Interestingly, like demonstratives, such elliptical strategies were also only found for inferred-existential uses. A very tentative hypothesis for this fact is that speakers use them to convey the inferred state of affairs – such as having a barbecue and lighting a campfire in (86) – without going as far as also explicitly indicating – through, say, mensen ‘people’ – the inferred existence of any individual(s) responsible for it. The reason, finally, why Afrikaans does not allow the patterns in (86) and (87) in our view may have something to do with more general constraints in the language for ellipsis, but this is, at present, unclear to us.

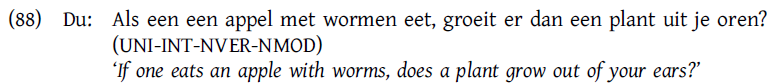

‘One’

We know from English (and other languages) that the numeral ‘one’ can grammaticalize into a full-fledged impersonal pronoun. No such change has taken place in Dutch or in Afrikaans, however. We nonetheless have one answer in our data (88), where Dutch een ‘one’ seems to occupy the subject slot of a conditional clause. Een may also be the indefinite article ‘a(n)’, of course (numeral [en] and determiner [ən] are not distinguished in spelling), which we suspect is the case here: the respondent must have forgotten to type the noun that was supposed to follow ‘a(n)’. Yet we do not want to exclude the possibility of impersonal een ‘one’ altogether. It is a common phenomenon crosslinguistically and English influence, for instance, should also not be written off completely as a potential factor. It is interesting to note in this regard that, in Van Olmen & Breed’s (Reference Van Olmen and Breed2018a) completion task, one of the Afrikaans respondents filled in een ‘one’ too (the determiner is spelt differently, as ’n ‘a(n)’).

Summary

The overview in section 4.2 shows that impersonal contexts can be and are, in fact, expressed not only through established strategies like passives, personal pronouns, nouns meaning (or deriving from) ‘human being’, and indefinite pronouns but also through a whole range of other strategies. Most of them (e.g., infinitives, nominalizations) are found in both Dutch and Afrikaans. Moreover, even if they only occur in the data for one of these languages (e.g., ‘the others’, free-choice items), it is nevertheless evident that they are an option in the other one too. This overlap is obviously due the fact that Dutch and Afrikaans are closely related. There are, however, also exceptions to this tendency, such as the use of elliptical strategies in inferred-existential contents.

4.3. Discussion of the Preferred Strategies Per Context

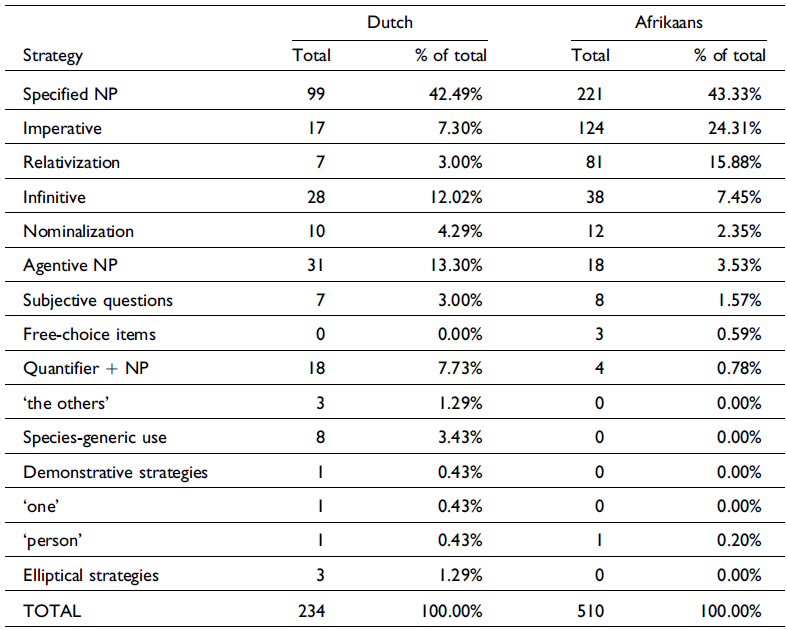

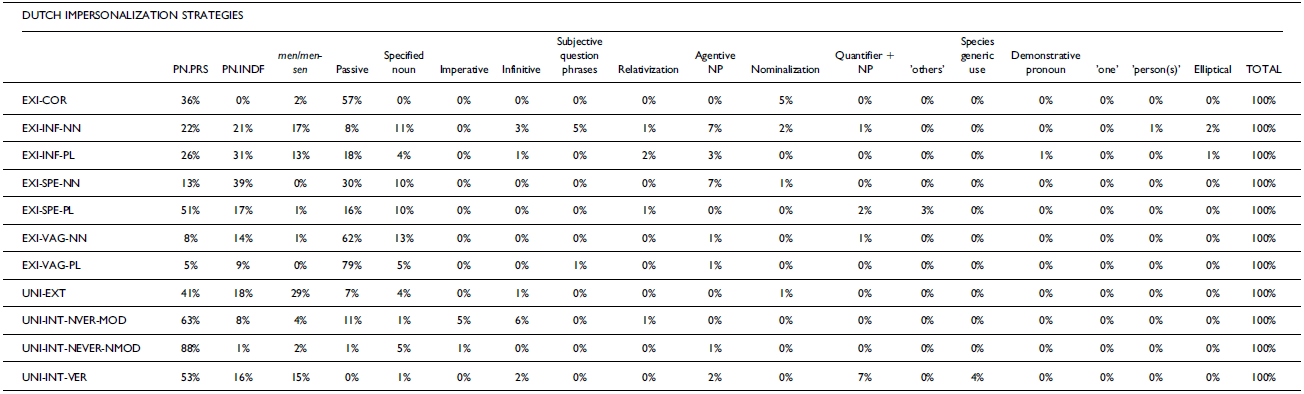

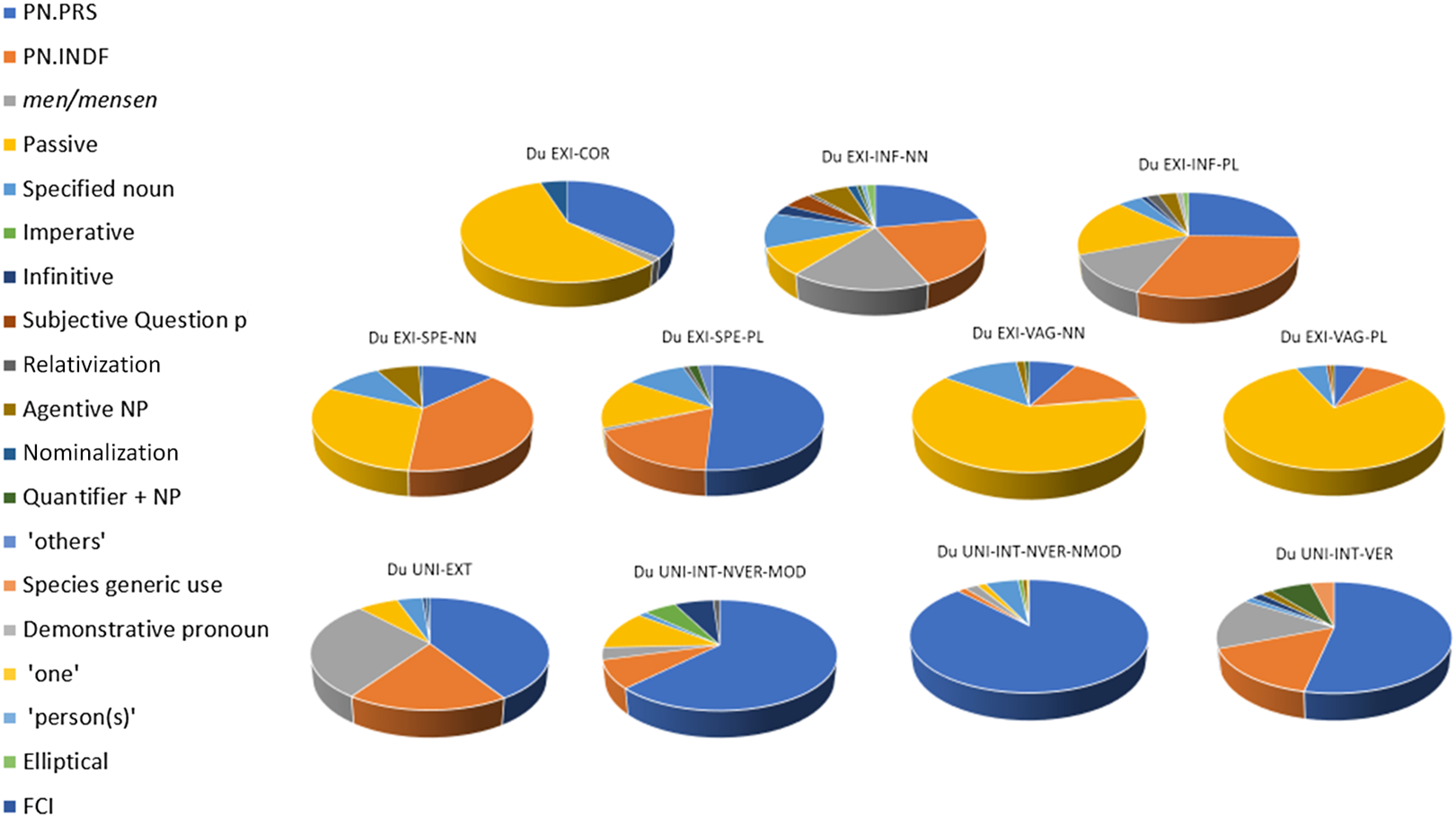

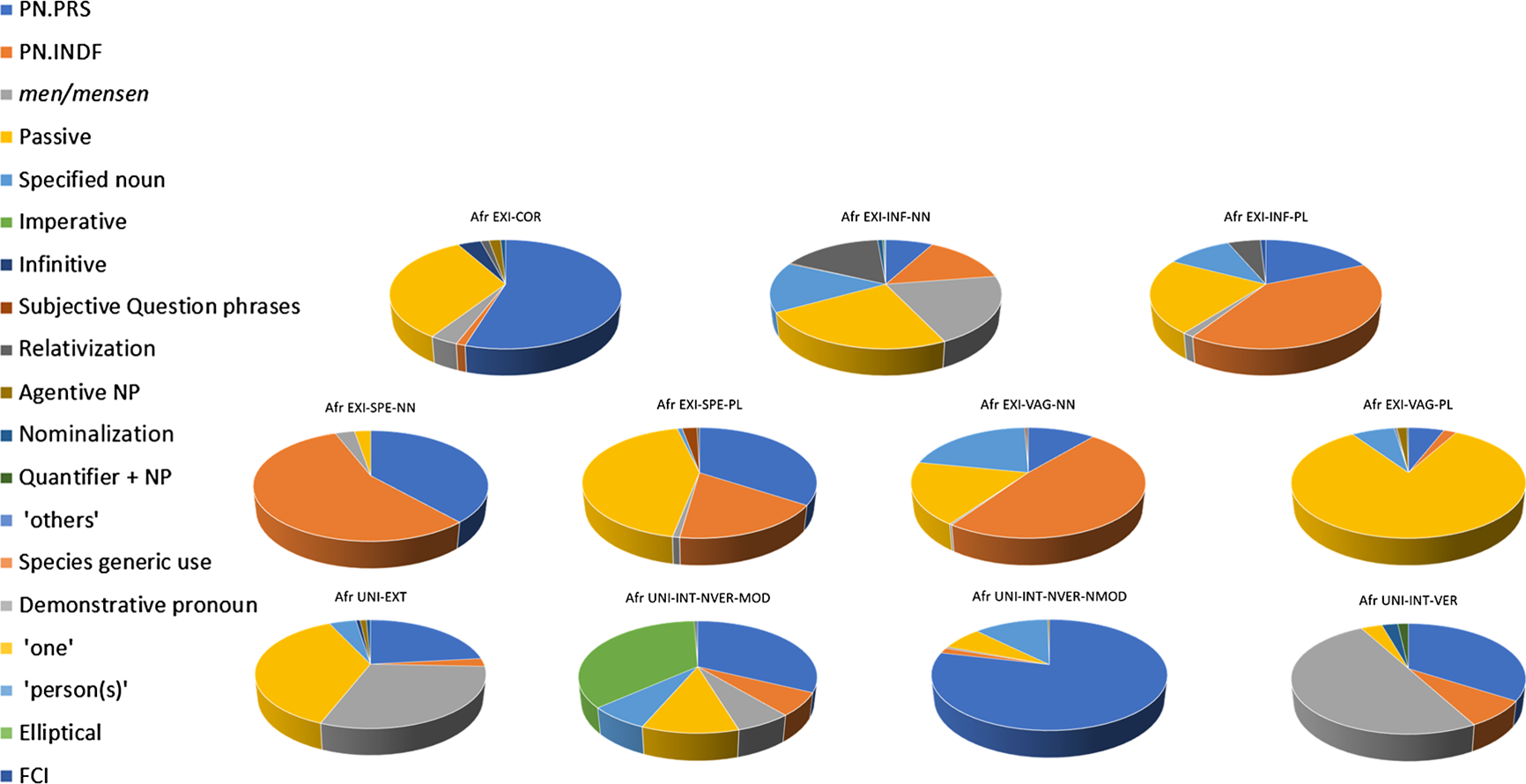

Tables 6 and 7 provide a summary, for Dutch and Afrikaans respectively, of all the strategies used in the different impersonal contexts. The results are also presented in Figures 5 and 6.

Table 6. Impersonal strategies in Dutch per context

Table 7. Impersonal strategies in Afrikaans per context

Figure 5. Impersonal strategies in Dutch per context

Figure 6. Impersonal strategies in Afrikaans per context.

We will limit ourselves here to a few general observations about the strategies that Dutch and Afrikaans prefer for different impersonal contexts. A more in-depth discussion would require more space than the present article allows and it would also only be really appropriate, especially for any comparisons between the two languages, if we took into account the Afrikaans data for all visual stimuli (see section 3.2).

A first observation concerns the use of personal pronouns. They are, by far, the dominant strategy across all universal-internal contexts in Dutch and Afrikaans but figure less prominently across the other impersonal contexts. This finding is in line with earlier ones for these two languages (and others): Van Olmen & Breed’s (2018:839) completion questionnaire, for instance, also suggests that “the universal-internal domain has a much stronger preference for pronominal forms of impersonalisation than the non-universal-internal one.” In addition, Afrikaans makes frequent use of imperatives in nonveridical-modal contexts and of (’n) mens particularly in veridical contexts, where it may still have its original species-generic meaning (see Giacalone Ramat & Sansò Reference Sansò, Giacalone Ramat, Ramat and Roma2007). For veridical uses, Dutch also appears to be partial to universal indefinite pronouns such as iedereen ‘everyone’.

Turning to the “semi-impersonal” contexts of universal-external and existential-corporate (both contain clues that make identification more or less possible), we can note that the first one exhibits considerable variation in both Dutch and Afrikaans. What they share is the frequent use of mense(n) ‘people’, which tends to be marginal for most other uses. This result suggests that Haas’s (Reference Haas2018) findings for English people may apply to its Dutch and Afrikaans equivalents too: it specializes in generic readings (e.g., in China, people eat a lot of rice) – compared to the third-person plural, which is more characteristic of episodic ones (e.g., they have stolen all the computers). Ze and hulle ‘they’ still occur quite often for our universal-external stimuli, however. A perhaps somewhat remarkable result (cf. Breed & Van Olmen Reference Breed, Chan and Van Olmen2021a:196) for such contexts is the relatively high number of passives in Afrikaans. They are not found very frequently in our Dutch data and, crucially, lack the explicit external perspective that ‘people’ and ‘they’ possess: ‘rice is eaten a lot in China’ can, in principle, include or exclude speaker and addressee. For existential-corporate uses, then, we can note that they have the same two dominant strategies in both languages, namely the passive and the third-person plural, even though Dutch seems to favor the former and Afrikaans the latter. The passive arguably works well in such contexts because it simply presents the state of affairs that itself already points to the entity responsible for it. At the same time, ‘they’ fits very well too. The corporate character of the referent is compatible with its original plurality as a proper personal pronoun and their semi-identifiability with its original definiteness.

As regards the other existential uses, we can first of all observe that Dutch and Afrikaans are both partial to the passive for vague ones. Yet, for number-neutral instances, the indefinite pronoun iemand ‘someone’ is very common as well in Afrikaans. This finding suggests that, if speakers assume that one unidentifiable person is responsible for something, they can (but need not) signal this with their choice of strategy. The relative infrequency of ‘they’ in vague contexts in the two languages may be somewhat surprising, given its prominence in the literature on impersonalization. It might be taken to indicate that the third-person plural’s original definiteness (as well as plurality) is still felt to be present by a significant number of speakers of Dutch and Afrikaans, who would then prefer not to use it to refer to unidentified (groups of) individuals (see Van Olmen & Breed 2018). That said, ‘they’ does appear as a widespread strategy for existential-specific contexts, in plural ones only for Dutch but in plural as well as number-neutral ones in Afrikaans. An explanation for this phenomenon may be that respondents are actually using the third-person plural in a nonimpersonal way here, to refer directly to the people present in the here and now of the situation. Existential-specific uses also regularly feature passives in Dutch and Afrikaans and, for number-neutral ones in particular, iemand stands out in the two languages. Gast & van der Auwera (Reference Gast, van der Auwera, Bakker and Haspelmath2013:129) offer a reason for this indefinite pronoun’s occurrence here: “[In existential-specific uses, t]here is a ‘physically present’ and thus situationally accessible (singular or plural) agent, and a clearly perceptible event. Situationally known/specific uses of impersonal pronouns are most similar to (quantifying) indefinite pronouns like someone.” Existential-inferred contexts, finally, are generally the contexts in Dutch and Afrikaans with the least clear preference for particular strategies. We find substantial numbers of passives, third person plurals, mense(n), indefinite pronouns, specified nouns and relative strategies. Dutch especially exhibits a lot of variation there, with many “minor” strategies. Why the existential-inferred domain is so diverse is not immediately clear to us but its comparative complexity (the referents are not simply unknown, their existence is based on an inference and a state of affairs that itself is inferred) probably plays a role.

5. Conclusion

The main aim of this article was to determine what we can learn from using a visual questionnaire to investigate impersonal strategies in Dutch and Afrikaans (see section 1).

In the first instance we learned or confirmed a number of things about the impersonal strategies of Afrikaans and Dutch. We hope to have shown that, on the whole, the two languages have a similar range of more established strategies (see section 4.1) as well as less established ones (see section 4.2) at their disposal – although strategies unique to one of the two languages exist too (e.g., elliptical strategies). We also hope to have shown that Dutch and Afrikaans share certain preferences for specific strategies in particular impersonal contexts (e.g,. favoring pronominal forms of impersonalization in universal-internal uses) but may also differ (e.g. universal-external passives in Afrikaans but not in Dutch) (see section 4.3).

Furthermore, our study revealed that a visual questionnaire can be an effective method for exploring language phenomena that are not frequently encountered in existing corpora. We have discussed some weaknesses, including the not inconsiderable amount of unusable data – due to the complexity of the functional domain under investigation – and the impossibility of knowing whether personal pronouns are indeed intended impersonally – shared, at least to some extent, with corpus studies (see sections 3.2 and 4.1).

We nonetheless hope to have shown too that the open-ended, nondeductive character of the method: (i) enables researchers to uncover a variety of strategies that languages use for impersonalization (e.g., not only more “expected” ones like nominalizations but also less “expected” ones like assigning agency to a nonfirst argument; see section 4.2), which would be hard, if not impossible, to identify with other approaches; and, at the same time, (ii) confirms, from an unbiased perspective, that the strategies studied most in the literature are also the most frequent ones (see section 4.1).

Of course, we do not wish to claim that corpus or questionnaire-based research is not necessary. However, we believe that our deductive approach produces results that can then be the input for other types of approach which rely on predetermined sets of impersonal strategies. An acceptability judgments questionnaire based on data like ours could, for instance, subsequently determine whether strategies are unacceptable in certain impersonal contexts, which is something that a corpus study or a visual questionnaire cannot do. In the same vein, a corpus study could investigate how frequent the different strategies revealed by a study like ours are in actual language usage.

To conclude, there are several ways in which the design and use of the visual questionnaire could be further improved. One such way is to involve the respondents in a follow-up phase to clarify any unclear or ambiguous answers. This can help to ensure that the data collected is as accurate as possible. Additionally, as a questionnaire is designed based on the objectives of the study, researchers have the opportunity to structure the questions and instructions in a way that purposefully obtains the necessary answers. With these improvements, the use of visual questionnaires can provide valuable insights into language phenomena that may not be easily identified or investigated through other approaches.