1. Introduction

While increased attention has motivated several initiatives towards a more inclusive and equitable research environment, several testimonies of unacceptable behavior within the geosciences have surfaced over the recent past, adding to the evidence of systemic inequalities embedded in the scientific community. Accounts of harassment during fieldwork (Nash, Reference Nash2021), a lack of diversity at conferences and among awardees (Koenig and others, Reference Koenig, Hulbe, Bell and Lampkin2016; Bernard and Cooperdock, Reference Bernard and Cooperdock2018), documentaries about gender-based harassment and discrimination such as the movie Picture a Scientist (Witze, Reference Witze2020), the National Science Foundation (NSF) report on Antarctic stations safety (NSF and others, 2022); each of these testimonies highlights a dire need for change, i.e. the need for increased awareness and action towards EDI within the geoscience community, and in particular, glaciology. Important steps that are already being undertaken include, for instance, the creation of EDI committees in research institutes, EDI awards given by research funds, or EDI sessions at conferences (see e.g. European Geosciences Union, 2024). The glaciological community has changed in many ways over the past decades: for example, women did not participate in fieldwork with the British Antarctic Survey before 1987 (Hulbe and others, Reference Hulbe, Wang and Ommanney2010). At the same time, it is clear from the numbers and testimonies of unacceptable behavior, that there are still critical improvements to be made.

Recognizing where and when actions to promote EDI in glaciology should occur, and who is at the center of them, can allow us to identify critical and potentially transformative opportunities for systemic change that can bring the future glaciological community more in line with our present values. Moreover, research shows that an increase in the application of EDI principles within the scientific community is critical to delivering the best scientific knowledge and keeping the best scientists in research academia (Nielsen and others, Reference Nielsen2017; AlShebli and others, Reference AlShebli, Rahwan and Woon2018; Page, Reference Page2019). Creating an inclusive and diverse glaciological community is key to boosting scientific creativity and discovery, and critical for answering the many glaciological questions that will impact the world in the coming century.

The Karthaus Summer School on Ice Sheets and Glaciers in the Climate System (Karthaus; https://www.projects.science.uu.nl/iceclimate/karthaus/, last access: 05 March 2025) brings together participants and lecturers from around the world who study glaciology, thus representing an exceptional opportunity to convene an otherwise disparate and localized community around a common vision and set of shared goals. We used this platform to discuss the EDI challenges we currently face within the glaciological research community, how we can overcome them, and how we envision our research community to be in 50 years. Here, we present the outcomes of our discussions and articulate a shared future vision for glaciological research that can build on the positive changes that have been achieved and are currently underway in glaciology, address the gaps that remain, and promote proactive responses to future challenges.

2. Methodology

To raise awareness of EDI issues in the glaciological community, a workshop on the topic was included in the 2023 program of Karthaus, which was held from 24 May to 2 June 2023. The EDI workshop was the first in the history of the summer school, which has been held more than 20 times since 1995. Students and lecturers alike discussed current challenges in the glaciological community along with potential solutions to these issues. Participants came together around a set of questions including: “What do we wish to see in the community in fifty years?”, “Why does EDI matter for the field?”, “What are the barriers to EDI in the field?” and “How can we address these barriers?” (see Tooth and Viles Reference Tooth and Viles(2021) for other examples of framing questions). Students and lecturers joined together in groups of three to discuss the questions and suggest actions to tackle the identified issues. At the end of the workshop, a time capsule to express common wishes for our research community in fifty years was created: participants were asked to write down their visions for 2073 and responses were anonymously collected at the end of the summer school. Eighteen submissions were received that resulted from the workshop discussions. A time capsule is, oftentimes, a container with stored information that is left (i.e. buried) for future generations to find. Instead of performing such a burial, we here summarize the main outputs and perspectives from the workshop and outline the identified challenges and proposed countermeasures. Original submissions from the workshop are included in Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix A. We further integrate the outcomes of the three-person discussion groups during the workshop within the text.

We, the authors, are aware of our selected view on the current challenges in the glaciological community (arising from our respective socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds), and cannot provide a holistic and detailed piece on all the current EDI issues and solutions. We note that the majority of authors are training and/or employed at European or American institutions, but also clarify that our institutional affiliations belie a myriad of lived experiences that transcend these boundaries. To better discuss the mentioned themes and topics, further literature research was carried out, and additional data sources were accessed. The paper focuses on the time capsule submissions centered around EDI topics (cf. Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix A), opting to exclude submissions discussing the development of glaciological science by 2073 or the progressing impact of climate change. The full text of the time capsule submissions is available in the appendices; we encourage readers to consider these, as meaningful perspectives in their own right.

In the following text, the term “we” refers to the early-career authors who have worked to distill a wide-ranging collection of visions and recommendations into a coherent framework. Although our work has been guided by feedback from the instructors listed as co-authors, some differences in opinions concerning the details remain. “We” statements represent common perspectives and articulate a unified vision which we argue is essential to the vitality of glaciology in the next half-century. We use the terms “glaciologists” and “researchers” to refer to the broader glaciological and scientific communities (which we are part of) engaged in the study of the cryosphere. By 2073, we, the authors, will have (long) retired from our careers in glaciology. On the way there, however, we will have an increasing agency to implement the changes we propose in the following text and pledge to adhere to the principles we set out. Thus, we see our recommendations as a set of action items that we can pursue, in partnership with those who have more power and agency than we do today, and with those future glaciologists whose ideas and needs we can uplift in the future.

Although by no means exhaustive, we see our contribution as an important step forward for the glaciological community. While our focus lies on the cryosphere/glaciological community, the issues we face are not all particular to our field. Therefore, proposed suggestions can likely be easily transferred to other geophysical communities.

To derive a common vision for the future of our research community, we began with the concept of EDI as it arises from its three constituting words: Equality, which ensures everyone is treated equally, independently of characteristics (cf. the Equality Act, UK Government, 2010); Diversity, which entails recognizing, respecting and honoring the identities and differences of individuals related to their experiences, identities, and social and cultural backgrounds; and Inclusion, which refers to an open, welcoming, and affirming research environment and culture. This provided a helpful starting point, and it led to ideas and discussions that do not strictly align with these definitions. As such, some of the actions identified in this manuscript challenge and expand our own notions of EDI. We invite the reader to consider how our vision for glaciology in 2073 may be rooted in EDI while also growing to encompass a wide range of issues that impact the glaciological community today and in the future. Rather than restrict our visions to fit within these boxes, we worked to articulate an alternative framing that can be synergistic with equality, diversity and inclusion without being limited to it.

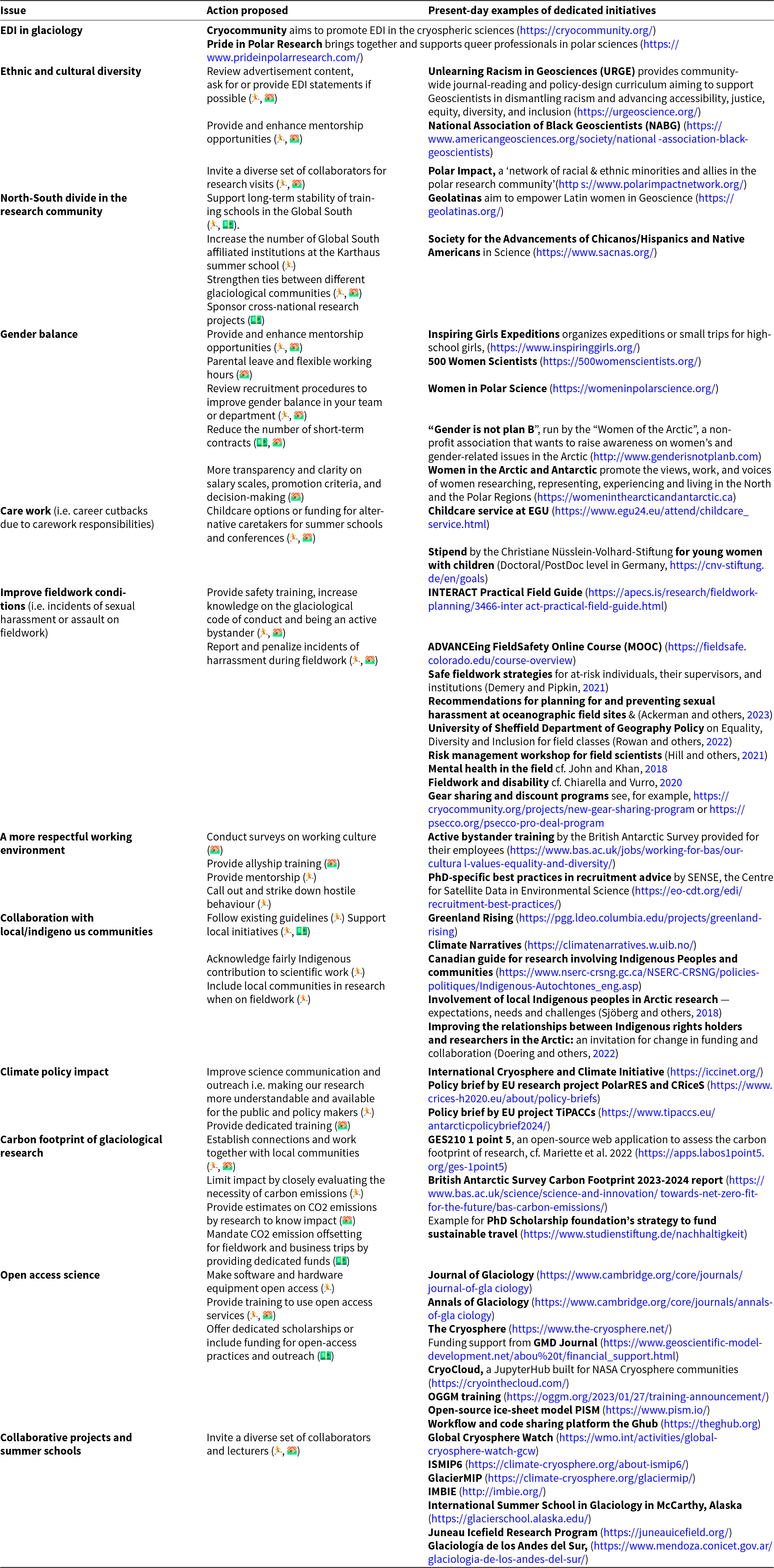

In this paper, we summarize and discuss the topics raised in the EDI workshop under the following three main challenges: (1) making glaciology more accessible, (2) more equitable and (3) more responsible. The subjects of submissions made at the workshop and time capsule are visually summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Visual summary of the outcomes of the EDI workshop of the 2023 Karthaus Summer School. The subjects of the wishes for the time capsule include improvements in terms of care work, diversity, science-policy interaction, gender balance, equality, North–South divide, carbon footprint, climate impacts mitigation, advancement of technologies, respectful working environment, open-access science and collaboration with Indigenous communities (cf. Table A1 and A2 in Appendix A). We hope that those proposed changes will “flow” together to create a more accessible, more equitable, and more responsible research community.

3. Challenge 1: Making glaciology more accessible

The lack of diversity is a central challenge our research community faces today, meaning that for some groups the glaciological research community, i.e. a career in glaciology or glaciological knowledge, might not be as accessible as it is to others (Robel and others, Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash2024). Historically excluded groups can include people from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds (minority meaning under-represented within the field of glaciology), persons with disabilities and neurodivergent people, individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community and minoritized genders, lower socio-economic groups, and minority religious groups. We first discuss ethnic and cultural diversity within glaciology and tie it to another important aspect to improve accessibility: the practice of open-access science.

When it comes to racial and ethnic diversity, studies showcase an alarming picture within the geosciences: hostile environments fueled by biases, discrimination, harassment and a lack of role models in senior positions work to maintain low racial and ethnic diversity over time (Bernard and Cooperdock, Reference Bernard and Cooperdock2018; Marin-Spiotta and others, Reference Marin-Spiotta2020). While we perceive the glaciological community to be predominantly white, we find this statement is not often acknowledged, discussed, or documented in our field of research. A recent study led by Robel and others Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash(2024) portrays our perception using available data: For instance, the authors looked into US-based researchers participating at the AGU Fall Meeting in 2022 and found that people who identify as ‘white’ represented 77% of the AGU Cryosphere section, compared to 67% of all AGU sections. This contrasts with the current 58% white US population (US Census, 2024). A considerable effort is needed to change the general poor diversity by facilitating access to resources and creating a safe and welcoming environment for people of color. For that purpose, we can redirect the reader, for instance, to Chaudhary and Berhe Reference Chaudhary and Berhe(2020), who give practical tips to actively fight racism in academia.

An issue that was specially mentioned in the Karthaus workshop was a perceived lack of diverse nationalities in glaciological research, particularly from the Global South. While ethnicity and nationality have different definitions, we argue that we can improve ethnic and cultural diversity in our field by decreasing the North–South divide in our research. The term “Global South”, whose use and appropriateness are discussed in public and academic forums (see e.g. Pagel and others, Reference Pagel, Ranke, Hempel and Köhler2014; Haug and others, Reference Haug, Braveboy-Wagner and Maihold2021; Patrick and Huggins, Reference Patrick and Huggins2023), refers to countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa with lower levels of socioeconomic development related to their colonial past, compared to countries in Europe, North America and Oceania, with higher levels of socioeconomic development, and which are often referred to as the “Global North” (Lewis and Wigen, Reference Lewis and Wigen1997; Dados and Connell, Reference Dados and Connell2012; Mudaly and Chirikure, Reference Mudaly and Chirikure2023). Adding to Robel and others Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash(2024), who notably show that >85% of current glaciology research (i.e. glacier and ice sheet research) is carried out in Europe and North America, the North–South divide in our research can be exemplified in membership statistics of the International Association of Cryospheric Sciences (IACS): as of September 2023, regions of affiliation were split between just 0.7% in Africa, 3.8% in Oceania, 4.7% in South America, 24.0% in North America, 24.9% in Asia, with the largest contribution from Europe (42.2%) (IACS, 2023).

Generally, funding biases within academia and research have led to a disparity between funding allocated to Global North research teams versus Global South ones (Talavera-Soza, Reference Talavera-Soza2023). This trend has led to a mass emigration of skilled people from the Global South to the Global North in search of better career opportunities in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), a phenomenon termed “brain drain” (Pellegrino, Reference Pellegrino2001). Although there are cryospheric science centers in the Global South (see e.g. WMO, 2022), we assert they may be less connected, visible, and/or acknowledged by the Global North-centered glaciological community. Explicit examples of this are found in international efforts that aim to bring together projections and observations of changes in the cryosphere and sea-level rise (cf. Table B1 in Appendix B). To our knowledge, these examples feature researchers affiliated solely with Global North institutions. The next phases of these initiatives would benefit from including the participation of Global South institutions and researchers. This course of action requires integration and strengthening of the scientific and institutional ties between the different glaciological communities.

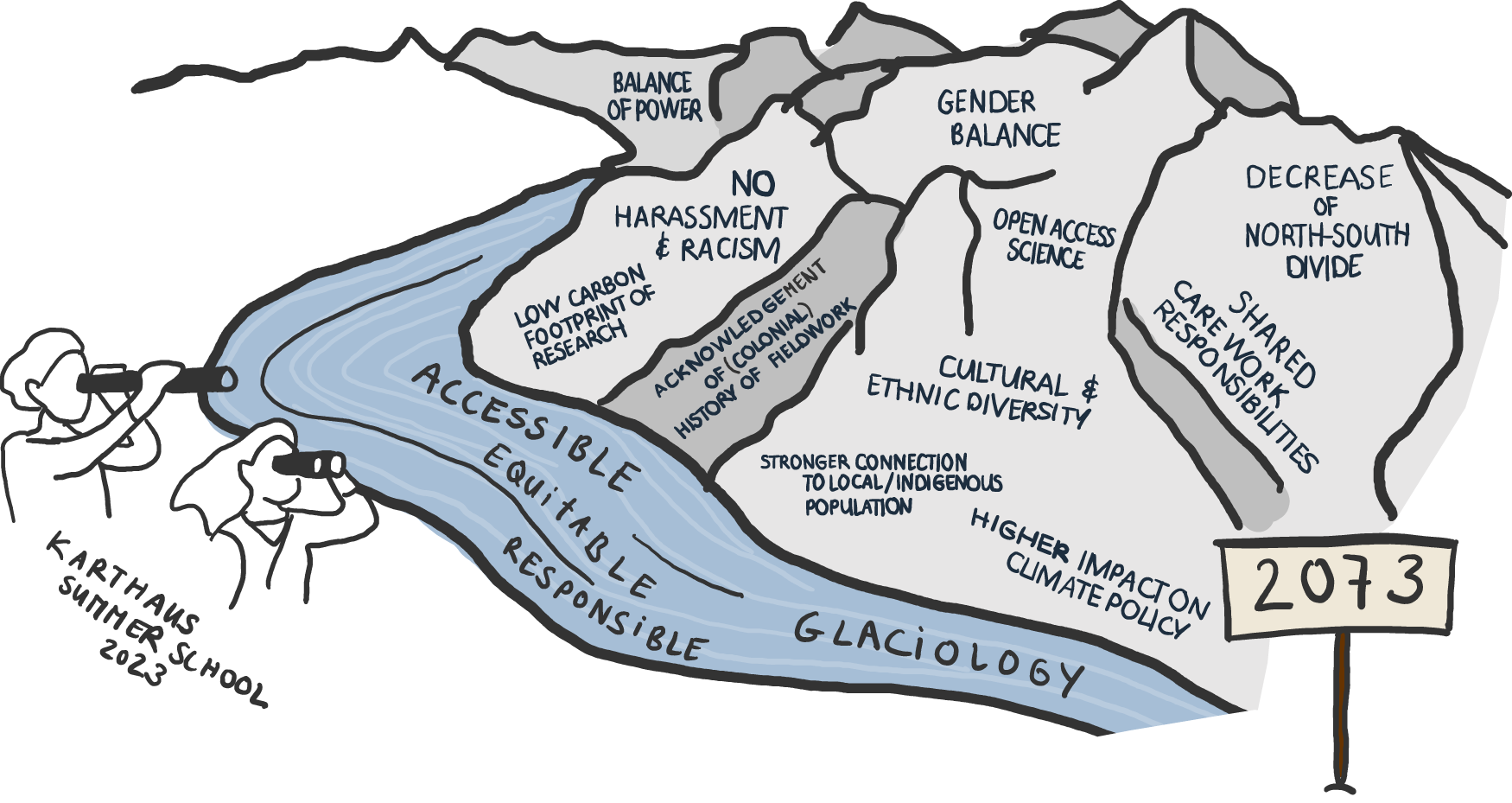

The global distribution of research institutions where Karthaus participants (1995–2023) were based is shown in Fig. 2. A majority of students were based at Global North research institutions throughout this period, including 100% in 2023. This fact is closely linked to both the global distribution of glaciology research centers and the general admission process to Karthaus, with the latter being itself related to funding sources (e.g. by European projects) and cost of student participation. The affiliation of many early-career researchers attending the Karthaus summer school does not match their nationality or home country. Postgraduate students often seek out international career opportunities that might not be given in their home countries (Banks and Bhandari, Reference Banks, Bhandari, Deardorff, de Wit, Heyl and Adams2012); this is not unique to glaciology. Ideally, international conferences, projects, or summer schools would feature a representative proportion of Global North to Global South participants, reflecting the global population, or at least the communities that may directly benefit from glaciological research (Robel and others, Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash2024). Although it would be unrealistic to argue that every country should have glaciological study programs, fostering (new) glaciological centers in the Global South as well as more funding to the existing centers, would give more local opportunities for a career in glaciology. An aim for the future of Karthaus could be to increase the number of students and lecturers affiliated with Global South institutions. Implementing this change lies in the hands of those running the Karthaus school now and in the future. Another suggestion could be to support the long-term stability of existing initiatives in the Global South (e.g. National Himalayan Cryospheric Research Lab University of Kashmir, 2023; Universidad de Magallanes Chile, 2023, to name but a few) by funding agencies or societies, such as IGS, EGU, or AGU.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of home institutions from participants in Karthaus since 1995 (taken from the Karthaus website; https://www.projects.science.uu.nl/iceclimate/karthaus/, last accessed 05 March 2024). The map was created using the python plotly library using the ‘natural earth’ projection and the country polygons from datahub.io (2024), last accessed 18 February 2025. To avoid misinterpretations, mainland France and French overseas territories or departments are plotted separately in this figure.

For a positive example of how to diversify the nationalities represented in scholarly networks, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has reviewed its author selection strategy in response to the statistics of previous IPCC reports: the Global South had an authorship contribution of only 31%, despite being home to 84% of the global population. Over the last IPCC cycle, the Global South contribution has increased to 42% and 43% for the SR6 and AR6 reports respectively. While IPCC authors can be nominated by their respective countries’ focal points, the final decision on who becomes an IPCC author lies at the IPCC bureau. While these statistics show improvement, with similar trends for gender balance, they are still far from being representative (CarbonBrief, 2023).

Additionally, running international conferences in the Global South would facilitate international collaborations and give visibility to the science being generated there. An inspiring example lies in the biennial Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) Open Science Conference, which has been held in a variety of locations (e.g. Chile in 2024, India in 2022, Switzerland in 2018, Malaysia in 2016, New Zealand in 2014, etc.). By organizing more conferences in the Global South, the higher costs of travel would fall onto the (generally better funded) participants joining from the Global North, while at the same time allowing local and regional Early Career scientists to participate at a lower cost; an opportunity that bachelor and master students otherwise rarely have. This is not only beneficial for the existing glaciological community at the conference site, but an opportunity to involve interested students and promote their careers as glaciologists.

To further facilitate cross-institutional and cross-disciplinary collaborations, we suggest that research centers and both national and international funding agencies should (1) continue or begin sponsoring cross-national research projects, and summer schools, and support existing organizations and (2) further the practice of inviting a diverse set of collaborators for funded research visits. We, as predominantly PhD candidates, may have the possibility for such research visits ourselves, and in turn, can facilitate future requests addressed to us at a later stage in our careers. In this way, we can help increase the diverse range of expertise relevant to our science and enhance the societal relevance and resonance of cryospheric research outputs.

We identify recruitment for academic positions and undergraduate/graduate schools as another vital process to transform our research community by broadening opportunities for underrepresented minorities. When we have positions to fill, reviewing our advertisement content and language is important, although studies are not fully conclusive in how far the use of gender-neutral terms and EDI statements is impactful (Carnes and others, Reference Carnes, Fine and Sheridan2019; Castilla and Rho, Reference Castilla and Rho2023; Heath and others, Reference Heath, Carlsson and Agerström2023). More importantly, our institutions can help by providing mentorship, networking opportunities and support—actions that are known to lead to an increased sense of community and increased interest in STEM careers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019; Rockinson-Szapkiw and others, Reference Rockinson-Szapkiw, Wendt and Stephen2021). This could take the form of, for example, organized social activities or a “Welcome Center” for new employees to have an easy start in a country foreign to them or in a graduate school. The strategies should accommodate the laws and regulations in each country. For instance, a series of affirmative actions such as race and socioeconomic-based quotas were applied in universities in Brazil and were shown to be successful in decreasing racial and economic disparities in higher education a decade later (Zeidan and others, Reference Zeidan, de Almeida, Bó and Lewis2024). In other countries, such as the US, where racial and economic quotas in recruitment are illegal, other strategies can be used to promote diversity such as requesting a diversity statement in the application process, which outlines the applicants’ actions and commitment to contribute to EDI. In places where none of these measures are realisable, advertisements can be made appealing to underrepresented groups by posting them in neighborhoods, schools, and forums attended by these groups, together with outreach activities. Several organizations also provide support, awareness and advocacy for existing marginalized professionals and students in our field, inspiring a diverse new generation of glaciological researchers through visibility (see Table B1 in Appendix B).

In summary, we raise four action points to accelerate the transition towards greater ethnic and cultural diversity and better integration of the Global South in the international cryosphere community: integration in international collaborations, available training, additional funding and recruitment strategies. We argue that the responsibility lies with current leaders, and us as future leaders, of cryospheric science to ensure glaciological knowledge is shared globally from places where it is highly concentrated to places where it is nascent.

We further urge the community to make glaciology more accessible by continuing to move towards open-access science, which ensures transparent and freely available research without significant barriers. Open access most traditionally relates to published scientific articles, but can also concern data, models, hardware and software. We have gathered knowledge of open-access resources in glaciology to evaluate whether our field of research generally adheres to open-access principles (see Table B1 in Appendix B). Though our judgment is bound to be somewhat anecdotal, we see the philosophy of open-access science generally being followed in glaciology. Many of the most widely read journals in our field are open-access journals (i.e. Journal of Glaciology, Annals of Glaciology, The Cryosphere); they are, however, predominantly English-language journals. This might still be a barrier to the dissemination of papers in, e.g. the Global South, which could be addressed by wider (automated) language support, allowing for additional paper summaries or abstracts written in different languages. However, open-access publications often require substantial fees, which can be economically unattainable for researchers in low-income countries and/or with limited research funding. To ensure equitable access to publishing opportunities, fee waivers, subsidies, or alternative funding models can alleviate this financial burden for under-represented and resource-limited communities, and for most journals these are already in common practice. As the amount of glaciological data has increased significantly in recent years (Gärtner-Roer and others, Reference Gärtner-Roer2022), we consider inclusive data and code management practices to also contribute to open-access science, as well as facilitate the usage of such data, software, and tools. One way to facilitate inclusive research is to broaden the use of cloud computing in our field and enable free or shared access to High-Performance Computing (HPC) resources. The former spares the time-consuming installation of software and tools, making research more straightforward and accessible to those without a computer science background, and also tends to provide data storage to users. The latter gives access to computing resources for poorly funded research centers and allows for more efficient research (e.g. HPC is needed for most ice-sheet modeling research, yet is not available in many institutions, especially in the Global South).

Open-access initiatives must be developed (or continued) and funded further, such that essential training is available for anyone wishing to access glaciological data and computational tools. We also observe that a large amount of information is passed on through field campaigns and training within experimental research groups. We therefore see a potential to improve open-access practices, especially within field and laboratory work in glaciological research. This could be achieved by, for example, creating written and video tutorials and in-person and online workshops. Large field collaborations could also set aside funding for thorough documentation of processes and inclusion of researchers in less-connected groups. When applying for grants or organizing these workshops ourselves, we can make sure that time, dedicated funding, or even the cost of extra personnel is included for such activities. It is note-worthy that the EU funding scheme Horizon already mandates that open access to publications and open science principles are applied throughout their projects.

We argue that conducting glaciological research at an institution that is not well-connected with other research groups in the field becomes feasible when open-access resources exist. This also helps decrease the gap between institutions with different financial resources since subscriptions to certain journals and software programs can be expensive. In this way, open-access science improves diversity and equity within the field. Furthermore, it allows for glaciological methods to be more easily scrutinized by non-scientists, and can therefore introduce accountability and increase public trust in the research being done. This collaborative and inclusive spirit of open-access science is at the core of what we wish for the field of glaciology in fifty years. At the career stage of PhD students, we can ensure our published work, including code, is well-documented and reproducible.

We are committed to making glaciology more accessible by diversifying the community and adhering to open-access principles. When applying for funding or creating job opportunities, we invite researchers already in positions of power to co-develop opportunities with researchers from less connected universities. We are committed to doing the same when we have reached that stage.

4. Challenge 2: Making glaciology more equitable

While we discuss the accessibility of our research community in the previous section, we are convinced that we need to also work more towards retaining those who enter into a career in glaciology. We hence argue that glaciology should be made more equitable, meaning that we want a more fair and just research community in which, for example, care work and maintaining a successful career are not contradictory, and harassment and bullying are left in the past.

We hope to make glaciology more equitable by advancing gender balance and facilitating care work. We here define balance as access to equal opportunities and spaces, where participation within the research community is representative of the diversity in the population. Worldwide, less than 30% of researchers are women (UIS UNESCO, 2024), while women represent around half of the global population. At the 2023 Karthaus summer school, while 19 out of the 36 students were female, only 3 out of the 12 lecturers were women. Hulbe and others Reference Hulbe, Wang and Ommanney(2010) as well as recent membership statistics further support our perceived gender imbalance in the field: a survey from the IGS states that ∼43% of survey participants identify as female (IGS, 2023). The percentage is even lower at the International Association of Cryospheric Sciences (IACS), where 32.5% identify as such (IACS, 2023). At the main cryospheric science meeting in Chile (i.e. SOCHICRI), ∼33% of attendees were women and only ∼28% of oral presentations were given by women in the 2021 edition. Although the number has increased compared to previous editions of the conference, there is a long way to go to achieve balance. While these current statistics on gender balance highlight that progress is still needed, it is encouraging that they are documented. Having access to this data is crucial, as it provides a clear starting point for meaningful change, such as, for example, the report by the Ad-hoc Committee on Diversity and Inclusion (ADI) of IGS (IGS, 2023).

What is more, when it comes to having children, parenthood has an unequal impact in academia (Morgan and others, Reference Morgan, Way, Hoefer, Larremore, Galesic and Clauset2021). Female academics spend more time on housework and childcare in academia than their male counterparts (Schiebinger and Gilmartin, Reference Schiebinger and Gilmartin2010). Cech and Blair-Loy Reference Cech and Blair-Loy(2019) find that, in the US, 40% of women with full-time jobs in science leave or go part-time after having their first child. While we did not find explicit data on this for the field of glaciology, we assert that our research community is not an exception to this general picture. In glaciology, the question of who cares for the child becomes especially pronounced when it comes to fieldwork (Lininger and others, Reference Lininger2021).

For 2073, we wish for balanced genders at all levels in our field of research. Although today the concept of balance is compelling because the status quo is unbalanced (Ranganathan and others, Reference Ranganathan2021), we recognize that it may become a less relevant framework as historically excluded groups join the ranks of glaciologists in greater numbers. We advocate for an understanding of balance not in strict numerical terms, but within a framework that recognizes the obstacles and challenges that limit the participation of members of historically excluded groups. In this context, achieving balance would include the end of the “leaky pipeline”, the phenomenon that scholars belonging to minorities become progressively under-represented at higher academic career levels (Wickware, Reference Wickware1997; Resmini, Reference Resmini2016; Popp and others, Reference Popp, Lutz, Khatami, van Emmerik and Knoben2019; Ranganathan and others, Reference Ranganathan2021), also referred to as a “hostile obstacle course” (Berhe and others, Reference Berhe2022) or a road full of “potholes” (Alegria and others, Reference and2016). We envision that, in 50 years, care work will be less of an obstacle for a career in glaciology and science in general. We here refer to care work not only with respect to the care for children but also for partners, parents, family members, or friends with mental or physical health issues.

The presence of many initiatives promoting, empowering, and supporting women in science makes us hopeful for the future (cf. Table A1, Appendix B). To improve the current conditions, we further wish to highlight Alderson and others Reference Alderson, Clarke, Schillereff and Shuttleworth(2023)’s five considerations to help (female) early-career researchers succeed, which are: (1) formalization and enhancement of mentorship opportunities; (2) parental leave and flexible working hours; (3) more considerate recruitment procedures to improve the gender balance; (4) reducing the number of short-term contracts; and (5) having more transparency and clarity on salary scales, promotion criteria, tenure and decision-making. These recommendations are similar to those that we suggest to help increase the ethnic and cultural diversity in our research community. We further propose more flexible solutions for caregivers to join conferences, summer schools, or field trips. These could include providing childcare options at conferences and summer schools or providing funding for alternative caregivers for example (cf. Table A1 in Appendix A). Such initiatives should be available independent of the gender of the caregiver, to ensure that our community does not amplify the narrative of women being the main caregivers. Efforts to increase participation are often evaluated through tracking numbers and setting quantitative goals (Ranganathan and others, Reference Ranganathan2021; Karplus and others, Reference Karplus2022; Robel and others, Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash2024). This is a necessary practice for understanding the historical and present context that glaciologists work within, and can be helpful for goal-setting in the near term. However, in our efforts to envision the glaciology community in fifty years, we realized that a strictly quantitative understanding of balance is not sufficient for reaching our goals. Instead, we argue for an understanding of balance that can evolve in response to the growing diversity of the population, and it is far more complex than simply assigning a fixed proportion of the research force to minority groups. This expanded framework is essential within an international context, where quantification of people with some identities are lacking (e.g. non-binary), or where definitions of historically excluded groups differ. Although these differences pose challenges for meeting our goals, recognizing them can be a crucial first step towards navigating the path towards our vision of a more equitable glaciology. An expanded view of balance can guide us to also embrace intersectionality, a lens through which we can better understand the experiences of people with multiple historically excluded identities. In summary, we advocate that balance should be viewed as an evolving consideration, requiring the creation and maintenance of spaces where these conversations can take place and where strategies for maintaining diversity can be actively explored and implemented within a changing landscape.

We want to make glaciology more equitable by improving fieldwork conditions. The expansion of modeling, lab sample analysis, and remote sensing processing has helped diversify glaciology and the wider geosciences by providing alternatives to fieldwork. Despite this, fieldwork remains a fundamental aspect of glaciology (Stokes and others, Reference Stokes, Feig, Atchison and Gilley2019; Shafer and others, Reference Shafer, Viskuptic and Egger2022; Ackerman and others, Reference Ackerman2023). Opportunities for participating in fieldwork often require previous experience and specific equipment, including clothing and gear, which presents technical, physical and financial obstacles for many aspiring glaciologists. In this sense, fieldwork remains inaccessible especially to many marginalized groups and may lead to an endemic loss of diversity further down the geosciences career pipeline (Johannesen and others, Reference Johannesen2022; Clark, Reference Clark2023). The origins of fieldwork can also be dated back to colonialist practices when field expeditions were used to create surveys based on land suitability for settlement (Klymiuk, Reference Klymiuk2021; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021). To this day, racially fuelled harassment and discrimination, along with sexual harassment incidents, remain ongoing issues within the field of geosciences, with researchers raising concerns over poor protection and support (cf. Ackerman and others, Reference Ackerman2023, for a proposal to plan for and prevent sexual harassment during fieldwork, specifically in the context of oceanography). We hope that in 2073, sexual harassment and assault are non-existent.

We consider our discipline to be in part surrounded by a culture of silence around the mentally and physically challenging aspects of fieldwork, often excluding people with disabilities or mental health needs, leaving them to self-advocate for their right to be out in the field (Stokes and others, Reference Stokes, Feig, Atchison and Gilley2019; Clark, Reference Clark2023). We highlight the need for fieldwork to better represent the diversity in glaciology, rather than maintaining the idea of hardship being a “character-building exercise” (Maguire, Reference Maguire1998; Stokes and others, Reference Stokes, Feig, Atchison and Gilley2019).

To both make fieldwork more diverse and prevent harassment, we find it crucial to provide adequate training to aspiring glaciologists (on this topic, please also refer to Boon, Reference Boon2024). This training should include basic mountaineering and safety practices, a code of conduct, active bystander training and technical training for glaciological measurements. With strategies on how to create a positive and inclusive Antarctic fieldwork environment recently presented by Karplus and others Reference Karplus(2022) and already great initiatives in place (like a gear-sharing program, see Appendix B, Table B1), our community would further benefit from providing more funding for students to participate in inclusive field training. While the Karthaus Summer School does not include extensive fieldwork, all incoming students and staff must adhere to a code of conduct formulated for the 10-day stay in Italy. This is an example of an action that helps cultivate a safe and respectful culture (see also Dance and others, Reference Dance, Duncan, Gevers, Honan, Runge, Schalamon and Walch2024). Please note that the proposed actions would not address the colonial aspects of the history of fieldwork, which cannot be dealt with by individual researchers or groups alone.

Overall, we want to commit to making glaciology more equitable on fieldwork and in other workplaces by fostering a respectful working environment. The misuse of power and bullying are not uncommon phenomena in science (Else, Reference Else2018; Moss, Reference Moss2018; Van Scherpenberg and others, Reference Van Scherpenberg, Bultema, Jahn, Löffler, Minneker and Lasser2021; Mahmoudi, Reference Mahmoudi2023). In the field of glaciology, we see a strong desire to create a more respectful working environment at departmental and institutional scales to promote respect and understanding among peers, but generating actionable steps is often an obstacle. We further identify more transparency as an important step forward related to, for instance, evaluation criteria for tenure positions (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2016) or decisions on funding (Gladstone and others, Reference Gladstone, Schipper, Hara-Msulira and Casci2023).

What is more, studies show that structural racism is more pronounced in the geosciences community than in any other STEM field (Bernard and Cooperdock, Reference Bernard and Cooperdock2018; Beane and others, Reference Beane2021). Adding to that, other studies have shown that members of the LGBTQIA+ community face a more hostile environment in STEM compared to their peers (Cech, Reference Cech2015; Cech and Pham, Reference Cech and Pham2017). We see the scale of institutional power imbalance as the main obstacle to change, leading to fear of failure, and resistance or disengagement from people in higher positions. However, we recommend, for example, performing transparent, actionable surveys, that would be anonymized by independent facilitators and can be the basis for identifying local/institution-specific problems as well as solutions. Other actions could include introducing a diversified ombuds team at the workplace, providing allyship training (Stadnyk, Reference Stadnyk2024), and providing a web of peers or mentors to students in other institutions that could offer support in difficult situations. At the start of our careers in glaciology, as PhD researchers, we might only be able to participate in such training opportunities when available, but engaging now allows us to learn the tools to facilitate and implement actions later on. Another strategy that can help foster a healthy workplace is adopting the concept of shared leadership in mentoring: Distributing positions of power within a group of leaders can decrease conflict and enhance well-being, which helps increase the performance of groups and the satisfaction of employees (Zhu and others, Reference Zhu, Liao, Yam and Johnson2018). This can also create an environment that is less prone to power abuse.

We invite everyone in the community to strike down unwanted and hostile behavior, such as misconduct on fieldwork, and speak up for those who cannot or fear the potential consequences. However, it is essential to acknowledge the dangers inherent in “speaking for someone” without their consent. We think all glaciologists are responsible for actively creating a culture of “listening” so that the voices of those who do speak up are heard and taken seriously. In addition, we argue for pushing structural improvements that make misconduct less likely or acceptable. Allegations of discriminatory or abusive behavior must be taken seriously, also across institutions.

Both institutions and glaciologists across all levels share the responsibility to make glaciology more equitable. Institutions can provide care work solutions and training for fieldwork practices. We hold all those who take part in glaciology (including us authors) responsible for reporting bullying and harassment, while institutions must provide frameworks to deal with this.

5. Challenge 3: Making glaciology more responsible

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary research topic in itself, and as a research community, none of us stands alone. Within the Karthaus workshop, several comments were directed towards this aspect that we summarize under the concept of responsibility: the responsibility we have with regards to the history and cultural background of our research, the responsibility of “making our science count” (and not only conducting research in the ‘ivory tower’) or the responsibility we have towards our own carbon emissions. The third challenge we identify is thus making glaciology more responsible.

As glaciologists, we call for the improvement of direct collaboration between local and Indigenous communities and scientists. These actions should be especially focused on communities strongly affected by the global climate crisis and those in places where glaciological research is conducted. Robel and others Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash(2024) even conclude that due to the discrepancy in demographics between who is conducting glaciological research and who is benefiting from it (such as near glacier or coastal communities), research findings and subsequent policies have less effect, value, or overall use, coming with neo-colonialist undertones.

When working on, and producing knowledge about Indigenous land, we urge glaciologists to respect the wishes and sovereignty of the people who inhabit these lands. Given colonial aspects of the history of glaciology (Mercer and Simpson, Reference Mercer and Simpson2023; Robel and others, Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash2024), interacting with Indigenous peoples presents challenges that go beyond communication and present-day cultural differences. By establishing relationships with people in Indigenous communities, scientists can share questions, knowledge and skills sensitively and respectfully with local communities. In turn, Indigenous communities can, should they wish to, provide scientists with invaluable knowledge of the natural world built upon millennia of observation and knowledge-sharing through the generations within these communities. This connection can help develop science in a way that acknowledges Indigenous knowledge, needs, and skills, and includes local communities in all parts of the scientific process (from defining research questions to conducting research and communicating findings). We argue that creating an environment of collaboration and knowledge exchange with local and Indigenous people could be mutually beneficial. Building such relationships may take time, trust and commitment to establish. At all times, it is essential to ensure that locals share experiences and knowledge that illuminate and complement scientific findings on their terms.

There are examples of projects (Mahoney and others, Reference Mahoney2021; MacDonell and others, Reference MacDonell2022; Laptander and others, Reference Laptander2024) or initiatives that attempt to facilitate this kind of collaboration (cf. Appendix B, Table B1). Following Carey and Moulton Reference Carey and Moulton(2023), we invite glaciologists to ask a series of questions before starting fieldwork to ensure responsible field research. Among these are: “Whose land are we studying?”, and “Will our research incorporate other forms of cryospheric knowledge, such as local unpublished expertise or Indigenous knowledge?”. We recommend following existing guidelines and recognizing whether there are already existing local initiatives to support, rather than creating top-down schemes outside local communities, as well as acknowledging their contribution to the scientific articles fairly, (see also Sjöberg and others, Reference Sjöberg, Gomach, Kwiatkowski and Mansoz2018; Huntington and others, Reference Huntington2019; Doering and others, Reference Doering2022).

We further want to make our science more responsible by increasing our impact on climate policy. As polar regions are sites for geopolitical tensions (Dodds and Nuttall, Reference Dodds and Nuttall2016; Nielsen and Nielsen, Reference Nielsen and Nielsen2016), glaciology can be important to inform governance of these regions and understand the consequences of climate change (for example, see Colgan and others, Reference Colgan, Machguth, MacFerrin, Colgan, Van As and MacGregor2016). Among us, concerns were raised regarding climate politics being ineffective and not sufficiently based on the science provided by researchers (by us). Therefore, we call for more emphasis on linking glaciological research with climate policy and decision-making. The 2024 joint policy brief by EU research project PolarRES and CRiceS can be seen as one example of this (The CRiceS and PolarRES Consortia, 2024). Some of us early-career researchers have also already participated in dedicated policy events that are aimed at strengthening the ties between, for instance, ice-sheet modelers and local coastal planners or practitioners. In terms of climate change mitigation, the scientific community is already providing or can provide more insights into the changing cryosphere and its impacts on livelihoods.

In fifty years, we will live in a warmer, more climatically extreme world where adaptation policies also become increasingly important. Glaciologists are leading experts on how sea level and water resources are affected by climate change. We hope we can share this knowledge even more generously and that our research will be targeted (even) more towards the needs of society. For this, we could, for instance, follow more closely published briefs by policymakers for setting the priorities for our research. We can also make sure our publications are freely available and further engage in outreach activities. In the past, glaciologists have contributed to policies on numerous occasions, such as having a key role in securing the Antarctic Treaty in 1959 (Scully, Reference Scully2011), or collaborating on international projects such as the IPCC.

These international efforts have proven important for voicing concerns and communicating what we know of the future. It is our responsibility as scientists to synthesize knowledge in such a way that it is understandable, transparent and relevant for policy-makers. At the same time, we recognize that natural science does not hold all the answers; notably, the experiences and perspectives of local and Indigenous people are essential to creating effective policies (Robel and others, Reference Robel, Ultee, Ranganathan and Nash2024). Climate adaptation generally happens on a national scale and in local communities, neither of which are spaces where scientists can claim decision-making power. Instead, we argue we should make our research even more understandable and available for both the public and policy-makers. By strengthening international collaborations and outreach, voters and elected leaders can approach research and apply glaciological knowledge to decisions on their terms. If not specifically included in third-party project proposals, outreach activities might not be paid or not considered part of the academic “job description”. We authors can ensure that communicating our science is given enough time and priority in projects and invite everyone else to do the same.

Lastly, we want to make glaciology more responsible by reducing the carbon footprint of cryospheric research. According to literature, academics on average have a carbon footprint above the per-capita value of their countries of residence (Grémillet, Reference Grémillet2008; Fox and others, Reference Fox2009; Spinellis and Louridas, Reference Spinellis and Louridas2013; Stevens, Reference Stevens2020). We are aware that in the field of glaciology, going to remote places for measurement campaigns (the Polar Regions, Himalayas, Patagonia, European Alps, etc.) and/or using energy-intensive facilities (cold rooms, computing resources) in addition to office spaces and conference travels create a high carbon footprint of the conducted research. Therefore, we want to help reduce the carbon footprint of cryospheric research in the future. As climate-change-induced risks are increasing with every increment of warming (IPCC, 2023), we propose that the academic system must do its share in reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases as much as possible. The first step to reducing our footprint is to assess it properly and to identify ways to reduce our emissions. For example, publicly publishing our traveling choices (to workshops, conferences, etc.) is a strong social incentive. By promoting our assessments, we could help to better inform the carbon footprint of academia, which is currently poorly documented and not fully standardized (Helmers and others, Reference Helmers, Chang and Dauwels2021). Reducing our climate footprint, individually and collectively, leads to better well-being and a feeling of coherence with our messages (Thompson, Reference Thompson2011; Langin, Reference Langin2019) as we witness the impacts of climate change first-hand, e.g. when conducting fieldwork on a receding glacier. As climate researchers, we would further gain more credibility in the eye of the non-scientific community and may influence citizens, policy-makers, and companies to reduce their carbon footprint themselves (Attari and others, Reference Attari, Krantz and Weber2016), thus mitigating cryosphere loss and climate change. Reducing air travel to meetings, workshops and conferences might come at the expense of reducing inclusivity, as described above. By 2073 we hope that such contradictory demands can be treated in a well-balanced manner, by e.g. mandatory carbon off-setting of business travels or allowing for more online participation for events. Here, institutional support is key, i.e. providing options for employees to travel in a more sustainable way by e.g. allowing for more time and higher costs when choosing against flying.

Our commitment is here to further include more local communities in our research, if applicable, when on fieldwork. We invite everyone to support initiatives that are designed by local and Indigenous populations, to use our possibilities to raise their voices. Furthermore, when researching these fragile glacier landscapes, we must be aware of and limit as much as possible our impact as researchers within the climate crisis.

In general, the proposed solutions to the issues that we have raised in this article intersect and can strengthen one another. By listening to the needs of local communities, we might ask more applied and sophisticated research questions and create scientific evidence that is more useful to policymakers. By welcoming locals to lead and take part in glaciology, the climate impact of our research can be reduced.

6. Conclusions

Summarized in three categories, we discussed important EDI challenges present within the glaciological community and proposed different solutions or levers of change to overcome them. Obstacles to solutions suggested in the workshop generally followed the themes of scale, financial and workload capacity, and fear: fear of failure, fear of resistance and fear of disengagement. We would argue that building foundations for change, however small, can be our first step towards overcoming these obstacles to enact meaningful change in our community. By sharing challenges and visions from the 2023 Karthaus summer school with the glaciological community, we hope to echo the message that “practice makes different”, even if it does not make it “perfect” (Gilmore, Reference Gilmore2021). We wish to highlight that solving the above-mentioned problems will be beneficial for the whole community’s well-being as well as its research outputs. Since representation and visibility matter, we encourage and uplift ongoing projects and initiatives working towards more EDI in our field, examples of which we list in Appendix B, Table B1.

In this paper, we document the outcomes of the inaugural EDI workshop within a long-existing educational program that has trained hundreds of glaciologists over recent decades. Among a wide-ranging set of recommendations, we have linked common threads and identified touchpoints where action at different scales and contexts can move our community towards a vision that reflects our shared commitments to accessibility, equity and responsibility. We have also aimed at showing how these principles are intertwined. Glaciological knowledge is produced all over the world, in settings that may have little in common, and yet through this process, we have attempted to craft a vision that is globally relevant and responsive. The structure of the Karthaus summer school, which brings together participants of many nationalities from many institutions, was critical to our ability to integrate disparate reflections into a vision not just rooted in the past, but with a clear-eyed focus on the future. Beyond providing a guidepost that can hold us accountable to our visions and the success and well-being of future generations, we have demonstrated how community-oriented spaces like Karthaus can be leveraged as sites for incremental, and perhaps radical, change. At the 2024 Karthaus summer school, the majority of lecturers were women (Karthaus course information, 2024), a first in the history of the summer school. Reflections on the kind of scientific community we want glaciology to be in fifty years will continue in the form of the EDI workshop, representing one way that Karthaus will contribute to building the diverse, safe and impactful glaciological community that we see ourselves as part of fifty years from now.

Finally, we invite the reader to consider the points made in this paper and ask themselves where they want to see the glaciological community in fifty years. Above all, it is important to start and continue the conversation around EDI issues within our research community at any stage in our scientific careers.

Acknowledgements

The 2023 Karthaus course was sponsored by The Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, Utrecht University, The Netherlands Earth System Science Centre, Trewitax—GlaciersAlive, The International Glaciological Society (IGS), PROTECT (EU), Dutch Polar Climate and Cryosphere Change Consortium (NWO-NPP) and HiRISE (ENW-NWOI). Keisling acknowleges the work of the First and Second National Conferences, and particularly Randolph Bromery, Raquel Bryant and Rachel Bernard for inspiring the format and content of the EDI workshop. We thank all participants and lecturers of the 2023 Karthaus Summer School, as their engagement and interactions helped create a positive environment for meaningful discussions and reflections, which in turn influenced the development of this paper. Lawrence Bird was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Special Research Initiative (SRI) Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SR200100005). Maxence Menthon was supported by NWO Grant OCENW.KLEIN.243. Katherine Turner was supported by NERC funding through the University of Southampton INSPIRE DTP. Sally Wilson was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Panorama Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP), under grant NE/S007458/1. The authors acknowledge a diverse range of funding sources that supported the participation of the individual co-authors in Karthaus. Gratitude is extended to the four reviewers and the scientific editor for their insightful comments and constructive feedback during the review process that greatly strengthened this article.

Competing interests

Three of the (co-)authors are members of the editorial board of Journal of Glaciology. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

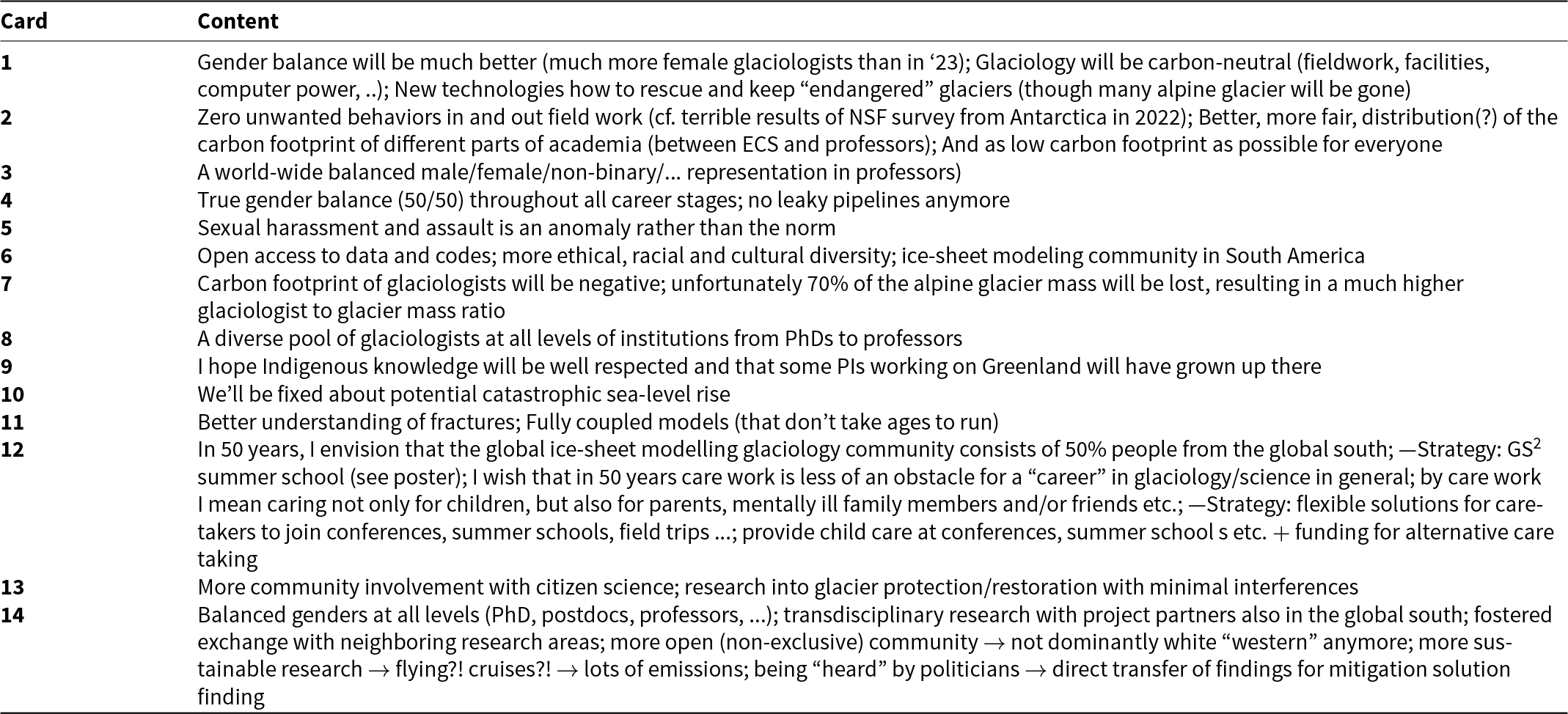

Appendix A. Original submissions to the time capsule

Please find Tables A1 and A2 that contain the original submissions to the time capsule.

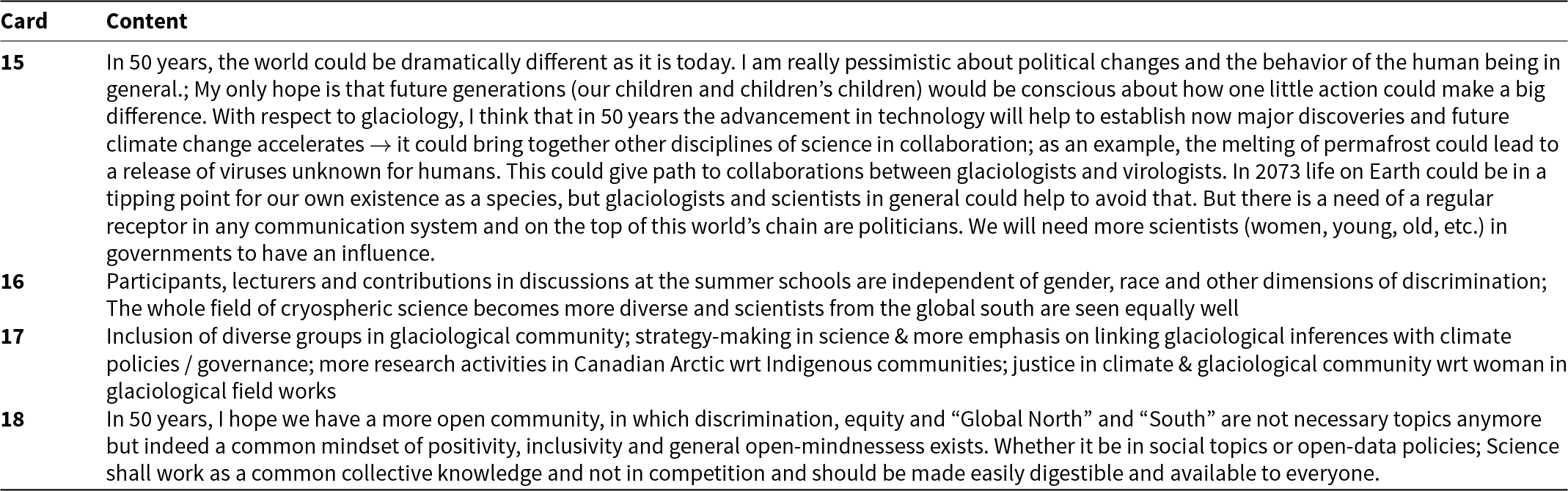

Table A1. Original submissions to the time capsule in the form of notecards. The contents of the individual cards are verbatim

Table A2. Table A1 continued. Original submissions to the time capsule in the form of notecards. The contents of the individual cards are verbatim

Appendix B. Overview on existing resources

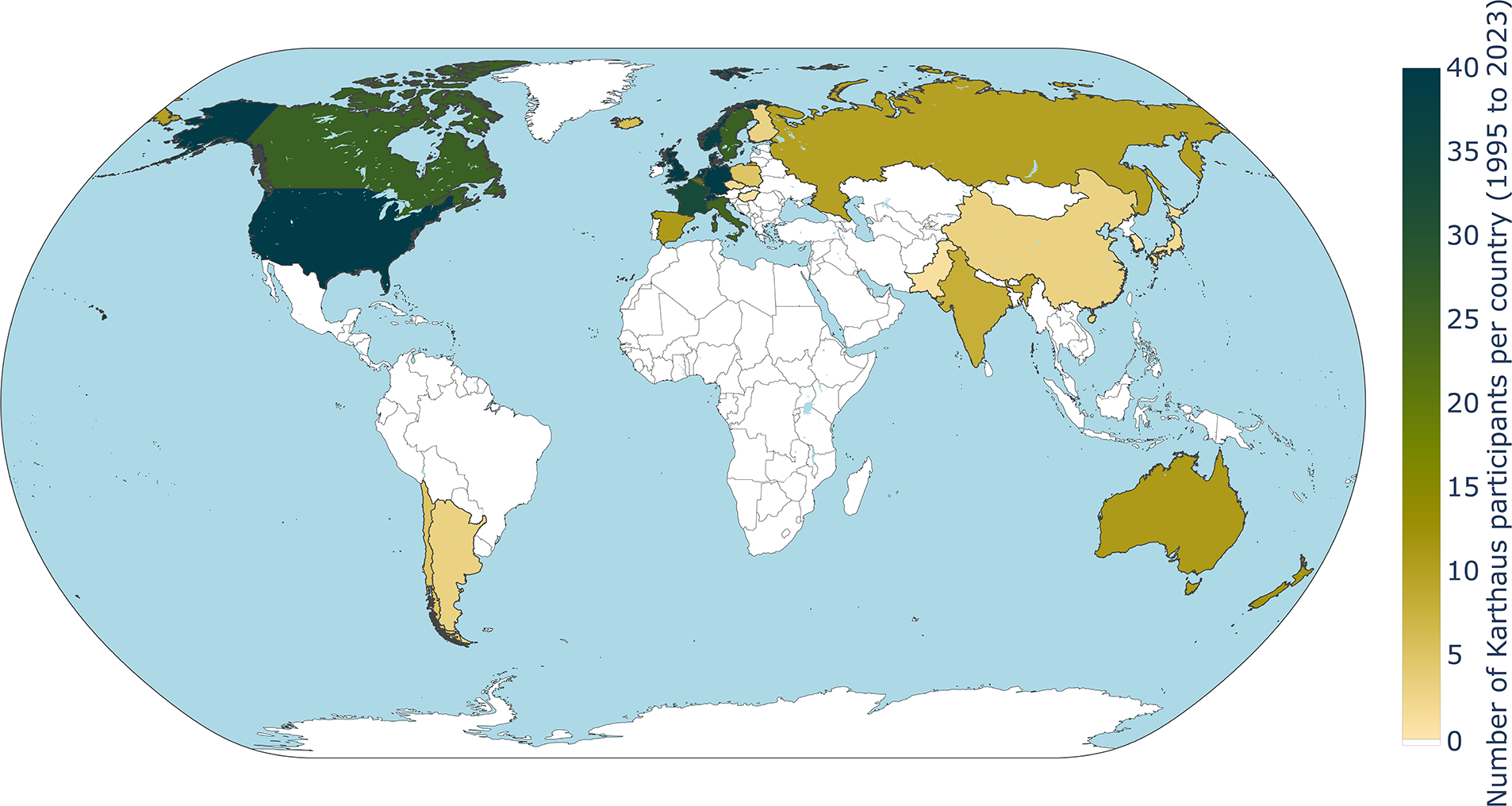

Table B1 provides an overview of (i) proposed actions to address identified challenges and (ii) related resources and projects that already foster EDI in our research community. Publications that are mentioned within the table are listed in the reference list (John and Khan, Reference John and Khan2018; Sjöberg and others, Reference Sjöberg, Gomach, Kwiatkowski and Mansoz2018; Chiarella and Vurro, Reference Chiarella and Vurro2020; Demery and Pipkin, Reference Demery and Pipkin2021; Hill and others, Reference Hill, Jacquemart, Gold and Tiampo2021; Doering and others, Reference Doering2022; Mariette and others, Reference Mariette2022; Rowan and others, Reference Rowan, Olund and Pickerill2022; Ackerman and others, Reference Ackerman2023). Last access to all webpages: January 30, 2025.

Table B1. Overview of proposed actions and present-day examples. Legend: Who has the agency to implement those changes? The individual ![]() , Institutions

, Institutions ![]() , Funding agencies

, Funding agencies ![]()