Introduction

Previous theories on corruption, including influential contributions by Western-based scholars, have often laid the foundation for understanding the phenomenon in both developed and developing societies. Scholars such as Bayley (Reference Bayley1966), Nye (Reference Nye1967), Werlin (Reference Werlin1973), and Heidenheimer, Johnston, and LeVine (Reference Heidenheimer, Johnston and LeVine1990) studied corruption in contexts such as Ghana, Nigeria, and broader Latin American, African, and Asian settings, emphasizing the role of traditional structures such as tribalism, patronage, and clan-based obligations in shaping corrupt practices. While this early work recognized the significance of informal norms, more recent anti-corruption models and global policy frameworks often remain rooted in institutional assumptions common to Western democracies and may underappreciate the nuanced ways in which culturally embedded informal practices operate in different regional contexts. In the MENA region, for instance, informal mechanisms such as wasta (reciprocity-based networking), hamula (tribal clientelism), and combina (favour-exchange systems) are not only prevalent but also historically entrenched, serving as parallel systems of influence and access. Recognizing the historical foundation of corruption research while highlighting this gap in policy application, this study examines how culturally specific informal practices relate to bribery patterns in the MENA region.

Informal practices, such as nepotism, clientelism, and other culturally specific mechanisms of personal influence, are often viewed as impediments to institutional development and good governance. However, in many contexts—particularly in weak or hybrid regimes—they can serve as mechanisms of stability and governance, facilitating access to public goods, mediating bureaucratic inefficiencies, and providing forms of accountability within local networks. Studies show that in the absence of fully functioning formal institutions, informal networks can help maintain social cohesion and political order (Booth and Cammack, Reference Booth and Cammack2013; Hale, Reference Hale2015; Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo, Reference Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo2017). In the MENA region, wasta and similar practices may be perceived by citizens not only as necessary but also sometimes as expected means of navigating everyday life (Benstead, Atkeson, and Shahid, Reference Benstead, Atkeson, Shahid, Kubbe and Varraich2020).

Corruption is the abuse of power for personal gain and is typically defined by legal and ethical standards. Examples include bribery, embezzlement, and fraud, which violate formal rules. The key difference lies in their motivation and perception. Informal practices arise as adaptive mechanisms in response to systemic inefficiencies and are culturally normalized. For instance, in societies with weak institutional frameworks, wasta provides access to services that might otherwise be unattainable. Corruption, however, is illegal and unethical by nature, seeking to exploit public resources for private benefit. The MENA region has been suffering from rampant corruption and informal practices (Kırşanlı, Reference Kırşanlı2023). Therefore, its elevated levels of bribery can be attributed to culturally specific informal practices, such as wasta, hamula, and combina which shape the region’s unique social and business interactions.

Our hypothesis to explain bribery through culturally embedded institutions or institutional stickiness (long-lasting wasta, hamula, and combina) is well suited to the literature (Storr, Reference Storr2013; Boettke, Coyne, and Leeson, Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2015; Choi and Storr, Reference Choi and Storr2019). Corruption is toxic for a region already struggling with weak state capacities, political and economic instability, and persistent security challenges. Without providing basic safety and essential human necessities to the public, anti-corruption campaigns may not produce good results per se. Corruption flourishes in environments where governance structures are weak, institutions are dysfunctional, and transparency and accountability are lacking (Mungiu-Pippidi, Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2020). According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), good governance is characterized by effective participation, rule of law, transparency, accountability, and respect for human rights—all of which are undermined in highly corrupt environments. Corruption is often actuated through informal practices coexisting and working parallel to formal institutions, often sustained by social structures and cultural norms and driven by cultural and historical conjunctures (Ridge, Reference Ridge2023; Kubbe, Baez-Camargo, and Scharbatke-Church, Reference Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Scharbatke-Church2024). However, informal practices can have both bright and dark sides.

On one hand, they play a critical role in structuring access to opportunities where the institutional quality is mediocre or low, as in Tunisia (Rahmouni, Reference Rahmouni2023). As its origins lie within a family structure, they create and maintain high levels of sociability with society, high levels of trust and solidarity between the involved actors or network members, and reduced transaction costs, and the risk of network members’ free riding. Therefore, informal practices provide societal stability through links between individuals and nations and are a form of government responsiveness and system stabilization (Benstead, Atkeson, and Shahid, Reference Benstead, Atkeson, Shahid, Kubbe and Varraich2020). Still, while informal practices may contribute to short-term stability by offering alternative access to services or maintaining elite cohesion, they can also entrench social and economic inequalities, particularly for women, refugees, and minority groups who are often excluded from influential networks. When access to public goods is conditioned on identity-based favouritism, entire segments of society may find themselves systematically disadvantaged. This exclusion not only limits upward mobility but can also fuel social unrest and violent mobilization. Empirical examples from countries such as Sudan, Somalia, Algeria, Iraq, and Libya demonstrate how long-term marginalization through informal and clientelist systems can catalyse instability, rebellion, and in some cases, civil war.

At the same time, the same informal practices that provide short-term access or social cohesion can also become entrenched vehicles of corruption. When informal practices such as bribery, nepotism, or wasta are used to bypass formal procedures and gain unfair advantages, they directly contribute to corrupt behaviour. Wasta, for example, can lead to outright corruption. Wasta-based interference in administrative practices in Jordan is a conduit for widespread nepotism, fraud in procurement processes, selling of public land, and miscarriages of justice (Al-Saleh, Reference Al-Saleh2016). Furthermore, if informal practices shape essential services, jobs, administrative paperwork, and other vital aspects, this can leave some people ‘out in the cold’ (Khalaily and Navot, Reference Khalaily, Navot, Kubbe and Varraich2020) and lead to emigration, as often seen in Jordan, Lebanon, or Palestine (Transparency International, 2019). It implies restricted possibilities for social advancement and overall improved well-being (Lust, Reference Lust2016) and is a reason why people want to leave their home countries. If workers’ appointments are based on family relations and not necessarily on merit, that could lead to many senior officials lacking the necessary skills, experience, and abilities to perform their jobs (Khalaily and Navot, Reference Khalaily, Navot, Kubbe and Varraich2020). Yet, where informal practices start and stop and when and how corruption begins is still unclear (Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo, Reference Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo2017) as measuring informal practices is inherently challenging and difficult (Voigt, Reference Voigt2018).

Substantial research has explored corruption in the MENA region. However, it has focused on institutional weaknesses or economic factors, paying insufficient attention to the role of culturally embedded informal practices. Practices such as wasta, hamula, and combina are often acknowledged but rarely examined through empirical methods. Existing studies have relied on anecdotal evidence or qualitative approaches, leaving a critical gap in understanding how these practices quantitatively influence bribery levels.

Many anti-corruption frameworks implemented in the MENA region have drawn heavily from Western-centric governance models—those that emphasize formal institutional reform, transparency tools, and legal enforcement, often derived from OECD, UNDP, or World Bank recommendations (Mohieldin et al., Reference Mohieldin, Amin-Salem, El-Shal and Moustafa2024). While these models are not inherently problematic, scholars have noted that they may fail to account for deeply rooted informal practices and power dynamics that shape corruption in MENA contexts (Boettke, Coyne, and Leeson, Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2015; Marquette and Peiffer, Reference Marquette and Pfeiffer2015; De Sousa, Reference De Sousa2010). These frameworks often overlook the social embeddedness of informal institutions and can result in limited impact when transplanted without local adaptation.

By examining these issues, this research posits that informal practices significantly contribute to the elevated bribery levels observed in the MENA region. The findings aim to inform the design of culturally attuned anti-corruption measures, moving beyond traditional, one-size-fits-all approaches to effectively combat corruption. Although some studies have focused on the economic, social, and political impacts of corruption and informal practices, the literature lacks systematic empirical analysis of bribery levels. Hence, this study makes two novel contributions. First, it empirically investigates the bribery levels in five sectors (education, judiciary, medical, police, and permit) in the MENA region and globally and then compares them with a dataset that has not been utilized before. Second, the higher bribery levels in the MENA region can be elucidated with the common informal practices of wasta, hamula, and combina. These practices are core mechanisms underlying the prevalence of bribery in the MENA region. We posit that addressing MENA’s bribery challenges requires understanding and recontextualizing these culturally ingrained practices.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section examines the theoretical framework of social norms and corruption and wasta, hamula, and combina while reviewing the literature. The third section discusses data, models, and econometric specifications. The fourth section provides multinomial logistic and logistic model regressions, while the penultimate chapter shares the robustness checks. The last section provides policy implications and concludes.

Theoretical framework

Corruption and informal practices

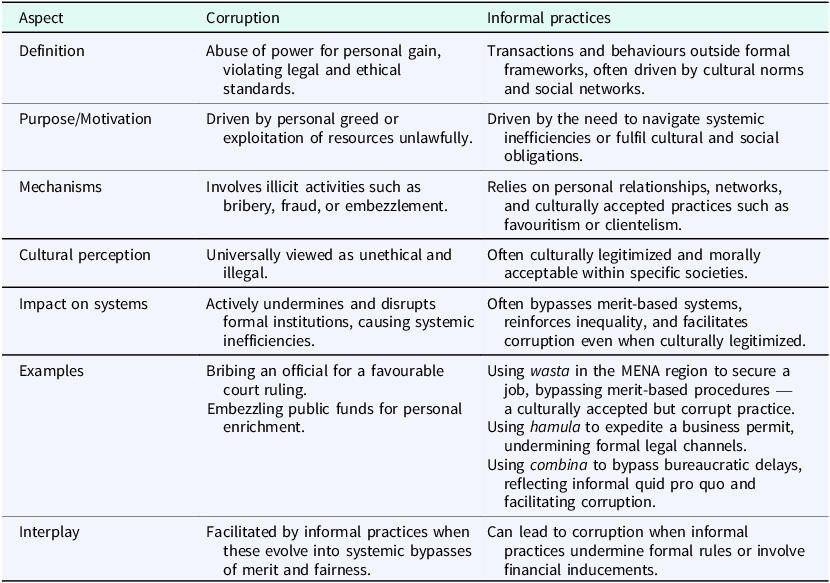

When an individual utilises wasta to expedite their appointment by leveraging a personal or familial connection, this constitutes a form of corruption—regardless of whether money changes hands. Though such practices are often culturally normalized and operate through social relationships, they undermine merit-based systems and equal access to public services. Similarly, using hamula to fast-track a business permit bypasses formal legal channels and violates the principles of fairness, transparency, and institutional integrity. These actions represent non-monetary corruption—such as nepotism or favouritism—and their widespread use erodes trust in public institutions. Financial bribes and informal favours may operate through different mechanisms, but both ultimately serve the same function: to bypass official rules for personal or group gain. Therefore, informal practices like wasta, hamula, and combina should be considered forms of corruption when they provide unfair access to resources or privileges and contribute to systemic inequality. The informal influence that subverts formal procedures—regardless of cultural legitimacy or monetary exchange—must be recognized as a form of corruption (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of corruption and informal practices

Source: Own illustration.

It is therefore essential to distinguish between practices that are culturally embedded and those that are culturally justified. While wasta may reflect deep social ties and communal obligations, its functional role in bypassing fair procedures cannot be justified on cultural grounds alone.

Informal practices often enforce agreements and create a culture of corruption, complicating anti-corruption efforts that do not consider the underlying social context. In various countries, informal governance and networks facilitate corrupt behaviour, while perceptions of widespread corruption further perpetuate it. These practices are often driven by strong social norms and personal networks operating outside official channels. This pervasive informality creates a complex and resilient corruption system, making it difficult for formal anti-corruption measures to succeed.

Why do informal practices that drive corrupt behaviour exist? They meet an individual’s innate need to fit in, strengthen a sense of identity, and offer some predictability of behaviour. Similar to social norms, for groups, informal practices can facilitate coordination and promote social cohesion. Still, albeit related, social norms and informal practices are distinct concepts that help perpetuate corruption (Kubbe, Baez-Camargo, and Scharbatke-Church, Reference Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Scharbatke-Church2024). Social norms are the unwritten rules and shared expectations guiding behaviour within a society, providing a framework for what is acceptable (Cislaghi and Berkowitz, Reference Cislaghi and Berkowitz2021).

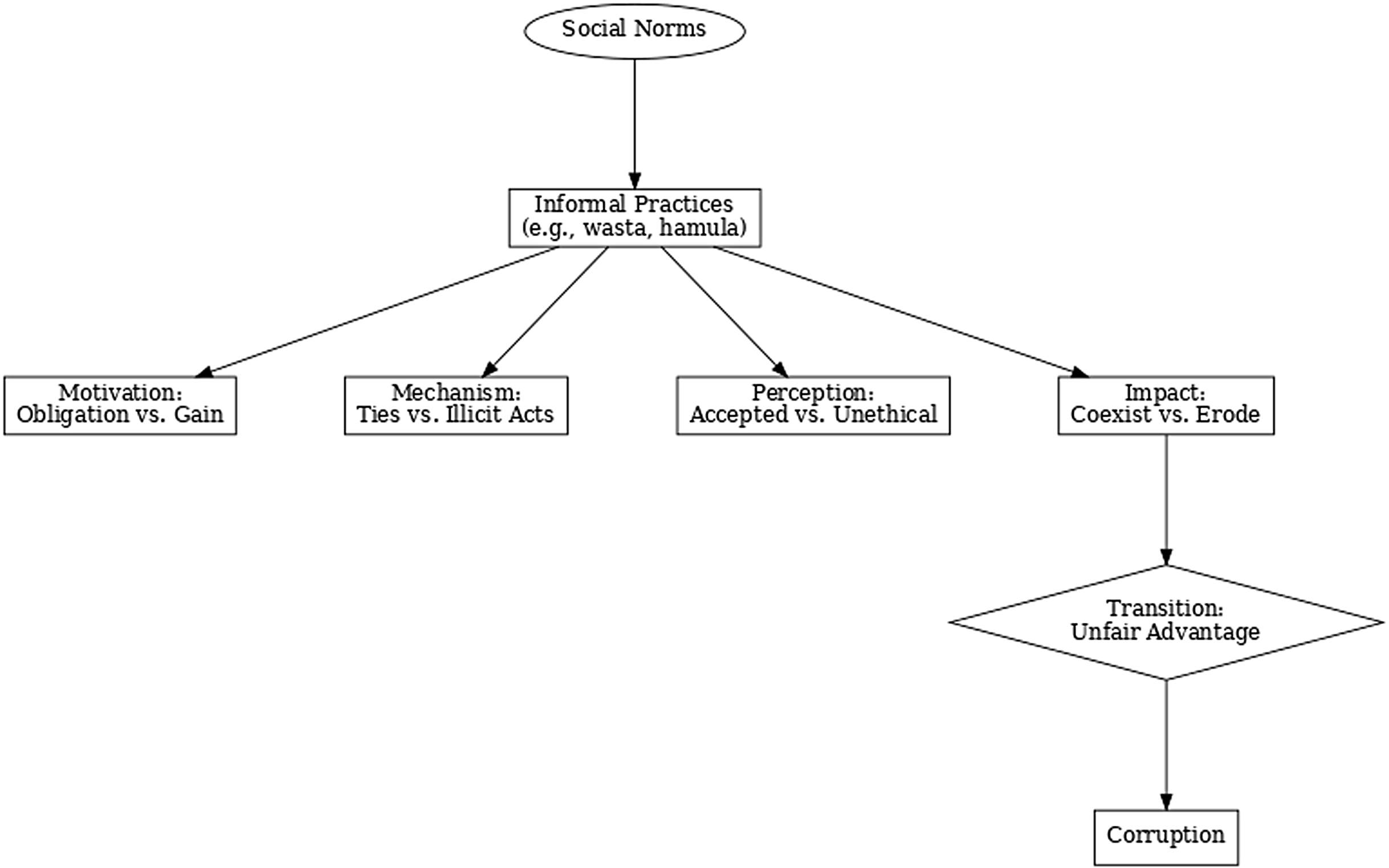

Informal practices are specific actions taken outside formal regulations, often to navigate inefficiencies or limitations of formal systems, and include corrupt behaviours such as bribery and nepotism (Fiori, Reference Fiori2018). While social norms are broad and abstract, influencing a wide range of behaviours, informal practices are concrete actions often driven by these norms, contributing to corruption when they bypass formal systems for personal gain (Lawless, Reference Lawless2023). Social norms set the expectations, and informal practices are how people act based on those expectations—especially when formal systems fall short, thus facilitating corrupt activities. Norm-driven activities may not serve the public good; however, they always have a purpose for those adhering to the norms in places of endemic corruption. Social norms that drive corrupt behaviour solve people’s problems, even when the result is socially negative (Scharbatke-Church and Chigas, Reference Scharbatke-Church and Chigas2019, p.49). These practices create environments where informal influence overrides formal rules, leading to systemic corruption and inefficiency. Figure 1 illustrates how culturally embedded informal practices—such as wasta or hamula—may be legitimized by social norms yet become forms of corruption when used to bypass formal, merit-based procedures. It highlights the role of intent, mechanism, perception, and institutional impact in determining when informal support crosses the threshold into corruption.

Figure 1. Navigating informal practices and their corruptive potential.

The transmission mechanism between informal practices and corruption is another reason why their distinction matters. Informal practices facilitate corruption by creating a parallel system of governance that bypasses formal procedures. The transition between informal practices and corruption often hinges on several factors, including intent. Informal practices are typically motivated by the need to navigate inefficiencies or fulfil social obligations, while corruption is marked by the intent to gain unfair personal advantage or profit. Another key factor is the mechanism of action. While informal practices rely on social relationships, corruption introduces illicit mechanisms that undermine institutional rules, such as bribery or coercion. The impact on formal systems is also substantial; informal practices may coexist with formal structures, whereas corruption actively disrupts and erodes institutional integrity. Finally, perception plays a critical role. Informal practices may be culturally sanctioned and even viewed as morally acceptable, whereas corruption is universally perceived as unethical or exploitative.

Therefore, formal anti-corruption efforts, such as implementing new laws and regulations, often fail because they do not address the deep-rooted informal practices that dominate everyday governance. These practices undermine formal institutions by creating parallel systems of power and influence that resist change. As Ganie-Rochman and Achwan (Reference Ganie-Rochman and Achwan2016) explain, understanding these regions’ social and cultural contexts is crucial for developing effective anti-corruption strategies. Without addressing the underlying informal norms and practices, formal anti-corruption measures are likely superficial and ineffective, unable to penetrate the entrenched networks of corruption operating within the shadows of official governance.

Informal practices and corruption: wasta, hamula, and combina in MENA and globally

In many regions, including MENA, informal practices are deeply embedded in governance structures, significantly influencing public administration and services. Culturally specific practices such as wasta, hamula, or combina exist everywhere in the world under different names and are prevalent in the MENA region (Barnett, Yandle, and Naufal, Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013). This resilience is reflected in the persistence of wasta-like practices across immigrant communities and diasporas, where these informal norms are maintained even after migration and often precede the development of modern state institutions (Al-Twal, Alawamleh and Jarrar, Reference Al-Twal, Alawamleh and Jarrar2024). Informal practices such as wasta and hamula are not exclusive to the MENA region. Comparable systems of informal influence—such as guanxi in China, blat in Russia, or protekzia in Israel—exist in many parts of the world and serve similar social functions (Lackner, Reference Lackner and Ramady2016; Li, Du, and Van De Bunt, Reference Li, Du, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016). These practices often pre-date formal institutions and are carried into diaspora contexts as well (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008; Al-Twal, Alawamleh and Jarrar, Reference Al-Twal, Alawamleh and Jarrar2024). However, in MENA, their entrenchment in political and bureaucratic life creates distinct challenges for governance and anti-corruption efforts, making region-specific analysis essential.

While these practices share similarities in leveraging social ties to achieve objectives, they differ significantly in cultural context, historical origins, and institutional interactions. Their impact is particularly pronounced in the MENA region. For instance, wasta reflects the collectivist nature of its societies, where tribal and familial bonds remain central to social organization (Al-Ramahi, Reference Al-Ramahi2008). Rooted in centuries-old traditions, wasta is culturally legitimized to maintain social cohesion and fulfil communal obligations. However, it also reinforces systemic inequalities by privileging those within influential networks and excluding outsiders. Its persistence is tied to the inefficiencies of formal systems, which push individuals to rely on personal networks to navigate bureaucratic challenges. This reliance reflects both historical reliance on tribal governance and modern institutional shortcomings.

In general, informal practices have social and cultural justification. In the wasta system, citizens with connections can quickly process their documents through government bureaucracy and help their close ones get hired. In the MENA region, strong cultural norms emphasize personal networks and reciprocity, making it safer and more effective to approach someone who is already known. A pre-existing connection increases the likelihood of a favourable outcome as the official may feel a sense of obligation to assist, blending informal practices with corrupt behaviour. This dynamic underscores the role of trust and cultural norms in facilitating corruption. Similarly, hamula impacts decisions in the country (Kubbe and Varraich, Reference Kubbe and Varraich2020). Memberships in impactful tribes are a substantial part of the state’s decision-making processes owing to those tribes’ close relationship with the ruling elites (Kırşanlı, Reference Kırşanlı2023).

Combina is helpful in reducing red tape in bureaucratic processes to gain documents, circumvent bureaucracy, or bypass the system as a whole (as blat in Russia, guanxi in China, wasta in the MENA, or Vitamin B in Germany). It is deeply rooted in cultural contexts but also lies at the foundation of the culture of corruption, such as in Israel. It does not include bribery per se but involves a specific quid pro quo. Combina is used in all life aspects and includes private and professional favours. This can be a case of protekzia, a special arrangement to secure a favour made by someone in the know or on the inside (Halfin, Reference Halfin2018). The term embraces various informal practices penetrating Israel’s formal institutions or official settings. Like blat, combinot is ‘people’s regular strategies to manipulate or exploit formal rules by enforcing informal norms and personal obligations in formal context’ (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2008, p119).

Wasta, hamula, and combina play central roles in economic, social, and political transactions in the world, particularly in the MENA region, and they help citizens in small- and massive-scale actions. Informal practices in the MENA region are deeply embedded in its historical and cultural context, shaped by centuries of tribal and familial governance structures that predate modern state institutions. These practices were essential for maintaining social cohesion and ensuring access to resources in environments where formal state mechanisms were underdeveloped or absent. Over time, they became culturally normalized, reflecting values of loyalty, reciprocity, and mutual support within close-knit networks. This historical embeddedness has made informal practices resistant to change. They serve as mechanisms for navigating the inefficiencies of formal systems, often acting as substitutes for bureaucratic reliability (Bayley, Reference Bayley1966; Leff, Reference Leff1964). For example, wasta, rooted in the region’s collectivist culture, operates to secure jobs, services, or resources through personal connections, particularly in settings where formal institutions are perceived as corrupt or ineffective (Kabasakal et al., Reference Kabasakal, Dastmalchian, Karacay and Bayraktar2012). Efforts to address these practices face challenges owing to their deep cultural significance and functional role in compensating for systemic inefficiencies. Reforms must account for the sociocultural legitimacy of these networks, focusing on improving institutional transparency and efficiency while recognizing the historical and cultural roots of these practices (Adnane, Reference Adnane2015). A reason for the failure of anti-corruption strategies in these and other countries is the need for regional, context-specific, nuanced approaches owing to the norms, guarantees, and principles defining relationships between regimes and citizens (Johnston, Reference Johnston, Kubbe and Engelbert2018). Therefore, the role that informal practices play in MENA, whether small or significant, must be addressed.

Data, model, and econometric specification

Data

We integrate individual-level data from the Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) as our primary variable of interest and supplement it with macroeconomic data from the Penn World Table (PWT) and Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) as control variables. By merging the PWT and V-Dem datasets with individual-level responses from the GCB, we ensure that each individual within the same country is assigned identical values for macroeconomic indicators such as inflation and unemployment. This approach allows us to account for broader economic and social conditions that may influence bribery tendencies, providing a more comprehensive framework for analysis.

From the GCB, we used a survey that was conducted by Transparency International (TI) between 2003 and 2013. Although newer data exist in TI’s database, we are constrained between 2003 and 2013 owing to matching issues with other macroeconomic data resources. In GCB, tens of thousands of people are asked whether they have paid bribes and to what extent they think corruption is rampant in their countries. GCB data at the individual level serves as the country’s representative in terms of experience and perceptions of corruption among people. Since the sample is not the same annually, this pooled cross-sectional dataset has regression constraints discussed in the econometric specification section.

To capture the differences in bribing, we employ a dummy variable for gender (male = 1) and region (MENA = 1). Moreover, as a proxy for the aforementioned informal practices, we employ ‘importance of personal contact’, a scale measuring whether having personal contacts in the government is important from 2 (little important) to 5 (very important). While this data has limitations in fully measuring the nuances of informal wasta and hamula networks, the use of ‘importance of personal contact’ as a proxy provides the most viable approach to capturing these practices within the given constraints. Given the complexity of informal structures, this measure offers a reasonable reflection of the role that personal connections play in government interactions, even if it does not encompass all aspects of wasta and hamula in their entirety.

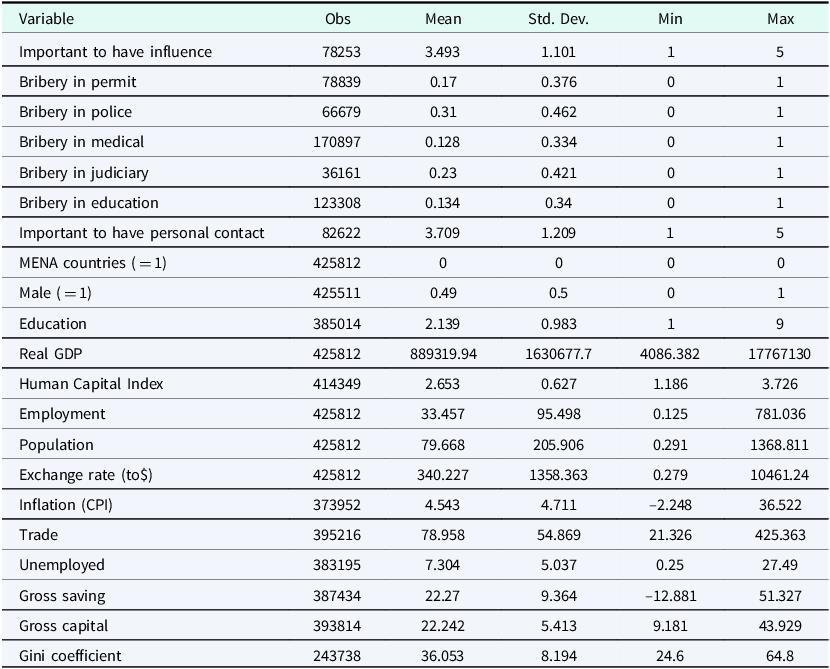

The control variables are real GDP, a measure of overall economic performance and wealth, years of education (years of each individual) to explore the influence of educational attainment on ethical behaviour and susceptibility to bribery, human capital index (based on years of schooling and returns to education), employment (% of people considered in the workforce) to understand labour market conditions and their influence on economic behaviours, population (annual population growth rate), exchange rate (average yearly exchange rate) to capture the relative value of currencies and its impact on economic stability and business practices, inflation (CPI) to gauge economic stability and purchasing power, trade openness (export-import), unemployment (% of people unemployed), savings (value of country’s gross saving), investment (gross capital formation), and the Gini coefficient to assess the impact of economic disparities on bribery practices. Descriptive statistics are provided in the appendix.Footnote 1

Model and econometric specification

We employ a multinomial logistic model to predict the likelihood of engaging in bribery. The multinomial logistic model is suitable for this analysis as it allows handling multiple dependent variable categories, offering a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing different levels and types of bribery across the studied regions. By incorporating a range of explanatory variables, such as income levels, education, regulatory quality, and cultural factors, the model provides a robust framework for assessing the propensity toward corrupt practices.

This method not only helps in identifying the key determinants of bribery, but it also supports the development of targeted anti-corruption strategies. By understanding the underlying drivers of bribery, policymakers can design more effective interventions to reduce corruption, promote transparency, and enhance governance. The use of cross-sectional data thus offers valuable insights crucial for both academic research and practical policymaking, particularly in regions where corruption remains a challenge.

Cross-sectional data increase observational power, facilitate international comparisons, and uncover associations between variables. Applying multinomial logistic models further enriches this analysis by providing detailed predictions of behaviours such as bribery, contributing to more informed and effective policy decisions. Our econometric specification can be seen in online appendix 1.Footnote 2

Furthermore, we delve into estimating the marginal impact of the odds ratio, ensuring it can be easily interpreted and understood. This step provides clear insights from our analysis. By following this specific econometric methodology, we accurately quantify the influence of various factors on the dependent variable. In the subsequent section, we present a detailed discussion of the results obtained. This includes an examination of the statistical significance, effect sizes, and practical implications of our findings, thereby offering a comprehensive understanding of the model’s outcomes.

Results and discussion

Multinomial logistic model

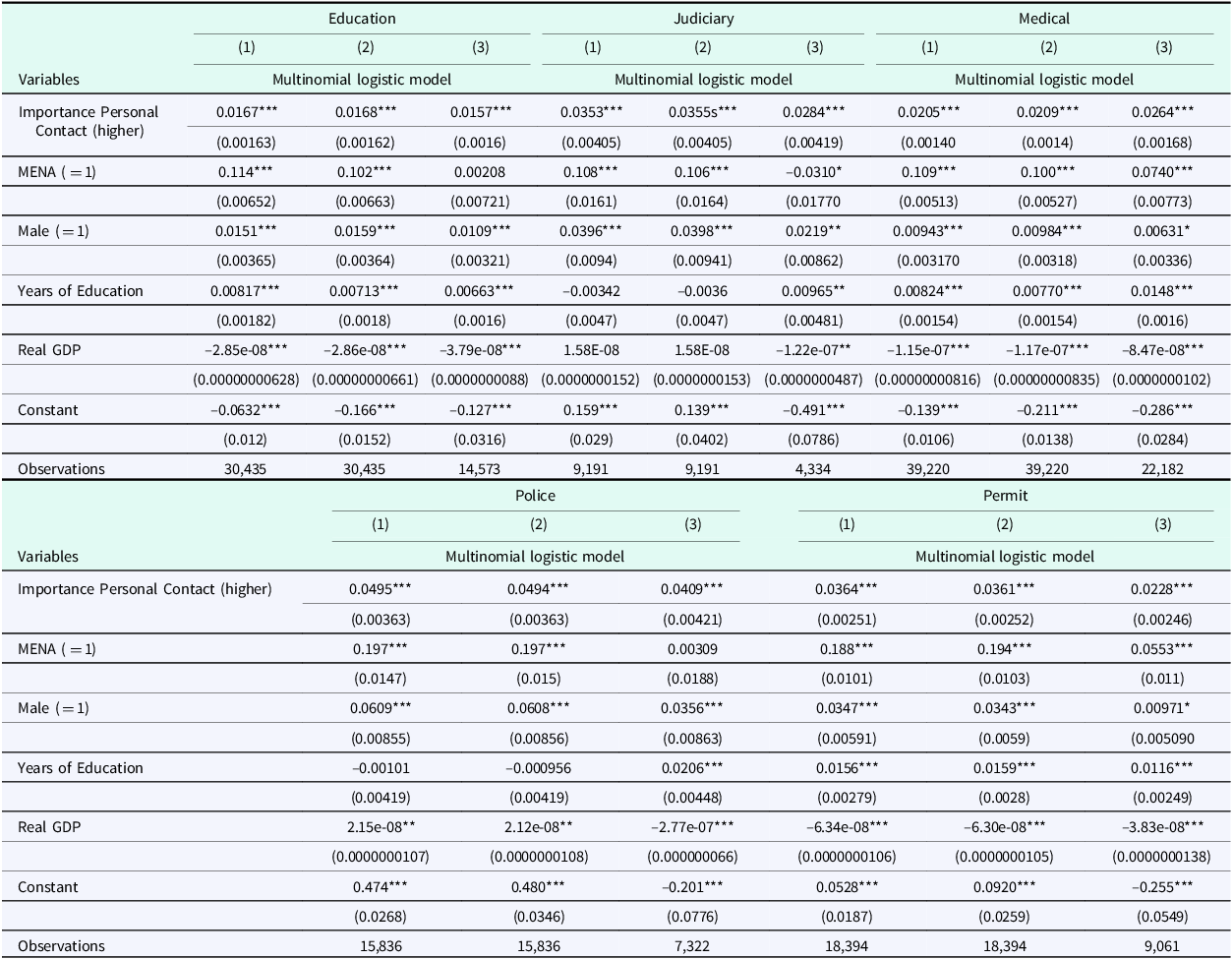

The analysis across various models in Table 2 highlights that the perceived importance of personal contact strongly correlates with higher bribery tendencies in multiple sectors, including education, judiciary, medical, police, and permits. Individuals with rated personal contact as important have significantly higher probabilities of engaging in bribery, with coefficients ranging from 1.57% to 4.95% depending on the context, all highly significant at the 1% level. The regional location also plays a crucial role, with individuals in the MENA region consistently displaying higher bribery tendencies—from 7.40% to 11.4%—across all sectors examined. This suggests that regional factors, such as cultural norms and socio-political environments, significantly influence bribery practices. For instance, in the judiciary sector, the coefficient is 10.8%, indicating a higher likelihood of bribery in this region. This indicates a consistent pattern where personal connections play a critical role in facilitating corrupt practices. For example, in the police sector, the coefficient is 4.95%, suggesting that personal contacts significantly increase bribery tendencies.

Table 2. Tendency toward bribery to education, judiciary, medical, police, and permit

Robust standard errors are in parentheses. *** P < 0.01, ** P < 0.05, * P < 0.1. Note: We are controlling all these macroeconomic variables: Human Capital Index, employment rate, population, exchange rate, inflation, and trade value (Export – Import). Gross saving is included in columns (1), (2), and (3). Gross capital is included in columns (2) and (3), and Gini coefficient is only included in column (3).

Gender differences are evident, with men more likely to engage in bribery than women. The coefficients for being male range from 1.09% to 6.09%, indicating a higher propensity for bribery among men. For instance, in the police sector, the coefficient is 6.09%, highlighting a significant gender gap in bribery tendencies. Education demonstrates mixed effects, generally positive in some contexts. For instance, in the medical sector, the coefficient for years of education is 1.48%, suggesting a positive relationship with bribery. However, in the judiciary sector, the coefficient is not significant, indicating no clear pattern.

Real GDP consistently shows an inverse relationship with bribery, which suggests that wealthier economies experience lower instances of corruption. This implies that economic development can serve as a deterrent to corrupt practices. Bribery is harder to prevail in richer society, probably due to stronger institutions through robust legal systems and economic stability that lead to greater economic opportunity, where individuals are less likely to resort to bribery out of desperation. We can also safely assume that higher wages and better social safety nets reduce the financial incentives for both giving and receiving bribes.

Furthermore, control variables such as human capital index, employment, population, exchange rate, inflation, and others further ensure the robustness of these findings. The results also highlight sectoral nuances. For example, in the judiciary and police sectors, the likelihood of bribery linked to personal contact and the MENA location remains consistently strong. Similarly, the medical sector shows a significant association between personal contact and bribery, with probabilities ranging from 2.05% to 2.64%. Moreover, the relationship between economic indicators such as GDP and bribery tendencies sometimes shifts direction depending on the model.

The results suggest that corruption is deeply embedded in social and economic structures, with personal networks playing a central role in enabling bribery. However, economic development indicators, such as real GDP and human capital investments, offer a counterbalancing effect, highlighting the potential for economic growth and institutional improvements in reducing corruption. These findings underscore the complexity of bribery and corruption, demonstrating that effective anti-corruption policies must be context-specific. Addressing systemic corruption requires a multifaceted approach that includes strengthening institutional frameworks, promoting transparency, and enhancing economic development to reduce the incentives for bribery across different sectors and regions.

Logistic model

Multinomial logistic regression in Stata has limitations that cannot accommodate categorical operators; thus, we run a similar model with a logit framework. The regression results suggest that the tendency towards bribery in education, represented by variable dependent (y), is influenced by several factors within an interaction model. The importance of personal contact exhibits a consistently positive relationship across different levels of importance and regions, which indicates its significance in driving bribery tendencies. However, the impact size varies slightly among different levels of personal contact and regions, with some coefficients showing stronger effects than others.

The results presented in Table 3 (online appendix) examine the importance of personal contact across three sectors—education, judiciary, and medical—while considering various interaction models. The variable ‘Importance Personal Contact’ is analysed at different levels (2–5), with a consistently positive and significant relationship across all models for the three sectors. Higher levels of importance in personal contact are associated with greater coefficients, suggesting a stronger impact. For instance, in the education sector, the coefficient for level 5 is 0.0958 in the simplest model (column 1) and increases to 0.116 in more complex models (columns 2–4). This trend persists in the judiciary and medical sectors, which emphasizes the value of personal engagement in shaping perceptions or outcomes.

When introducing the MENA region interaction, the results reveal interesting regional effects. For instance, in education, the interaction term (Importance Personal Contact ## MENA) shows diminishing and even negative effects at higher levels of importance. Specifically, at level 5, the interaction term is significantly negative (–0.0762) in education and more pronounced in the judiciary sector (–0.133). Thus, while personal contact is important globally, its impact in MENA countries may be less pronounced or operate differently compared to other regions. Interestingly, this pattern does not hold as strongly in the medical sector, where interaction effects are less consistent or insignificant.

Other control variables further enrich the analysis. For example, being male has a small but significant positive effect across all sectors. Education level, however, demonstrates mixed results. In the education sector, higher years of education initially show a negative effect in simpler models but become insignificant in more complex models. In the judiciary and medical sectors, higher education has a consistently negative or minimal effect. Therefore, demographic and socioeconomic factors play varying roles in determining the significance of personal contact across different contexts.

Finally, macroeconomic variables such as real GDP, human capital index, and inflation are included as controls. Interestingly, real GDP demonstrates both positive and negative effects depending on the sector and model specification, indicating its nuanced influence. The inclusion of such variables highlights the robustness of the analysis and ensures that the results capture not only individual-level dynamics but also broader contextual factors that shape the importance of personal contact.

Table 4 (online appendix) shows the analysis of the interaction model for police and permits highlighting the importance of personal contact and its varying influence across different contexts. For the police variable, higher levels of perceived importance in personal contact correlate significantly with increased positive outcomes, particularly in models (3) and (4). For example, respondents who rated personal contact as ‘important’ or ‘very important’ (categories 4 and 5) showed coefficients of 0.161 and 0.192, respectively, both highly significant at the 1% level. Personal connections are crucial in interactions involving police services, which reflects their potential to influence decision-making or perceptions of procedural efficiency.

In the case of permits, personal contact also plays a notable role but exhibits lower overall coefficients compared to the police variable. Specifically, individuals who rated personal contact as ‘very important’ reported a coefficient of 0.157 in the model (3), which—although positive and significant—is less pronounced than the corresponding value for police. Thus, while personal relationships enhance interactions for permit-related issues, the influence is more subdued, potentially reflecting differences in the institutional frameworks governing these services.

Additionally, the interaction between personal contact and the MENA variable reveals interesting regional disparities. For police, the interaction terms (e.g., ‘Importance Personal Contact (4) ## MENA’) show no consistent significance, which implies a weaker or inconsistent role of regional context in amplifying the importance of personal contact. In contrast, for permits, the interaction terms highlight some negative coefficients, such as –0.0956 in the model (2), significant at the 10% level. Therefore, in MENA countries, the emphasis on personal contact may not translate into better outcomes for permit services as effectively.Footnote 3

Control variables such as gender and education provide additional insights. Male respondents consistently reported higher levels of satisfaction or outcomes in both police and permit models. Years of education, however, demonstrated mixed effects: a negative association with police outcomes (–0.00762 in model (3)) and a positive association with permits (0.0117 in model (3)). These findings highlight the nuanced role of demographic and contextual factors in shaping the impact of personal contact on service-related outcomes.

The following section checks the robustness of the results with the fixed effects and propensity score matching (PSM) regressions.

Robustness checks

Fixed effects regressions

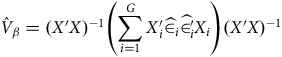

To effectively control country-specific heterogeneity, we employ clustered standard error models for cross-sectional data. These models function similarly to fixed effect regressions by clustering the standard errors, allowing us to account for within-group correlations. The use of clustered standard errors is crucial in situations where observations within each group are not independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.). By addressing this issue, the potential bias introduced by intra-group correlation can be mitigated. This method effectively removes unobserved heterogeneity between different countries in the dataset, providing a more accurate and reliable analysis. The computation for clustered standard errors is as follows:

$${\hat V_\beta } = {\left( {X{\rm{^\prime}}X} \right)^{ - 1}}\left( {\sum _{i = 1}^G X_i^{\rm{\prime}}\widehat {{ \in _i}}\widehat { \in _i^{\rm{\prime}}}{X_i}} \right){\left( {X{\rm{^\prime}}X} \right)^{ - 1}}$$

$${\hat V_\beta } = {\left( {X{\rm{^\prime}}X} \right)^{ - 1}}\left( {\sum _{i = 1}^G X_i^{\rm{\prime}}\widehat {{ \in _i}}\widehat { \in _i^{\rm{\prime}}}{X_i}} \right){\left( {X{\rm{^\prime}}X} \right)^{ - 1}}$$

where G is the number of clusters (countries). Xi is the matrix of independent variables for country i.

![]() ${ \in _i}\;$

is the vector of residuals for country i.

${ \in _i}\;$

is the vector of residuals for country i.

In Table 5, where the tendency toward bribery in education is measured, the results confirm previous findings in the multinomial logit model that MENA countries bribe the education authorities more than the rest of the world. Moreover, males bribe authorities more than females, and the coefficients are statistically significant in all regressions. Similar results are in the coefficients of control variables such as years of education and real GDP per capita. When the rest of Table 5 and Table 6 are checked, fixed effects results for bribery in the judiciary, medical, police, and permit sectors verify the previous findings that MENA people bribe authorities more compared to the rest of the world. The results of the robustness checks for Tables 5 and 6 can be also seen in the online appendix.

Propensity score matching

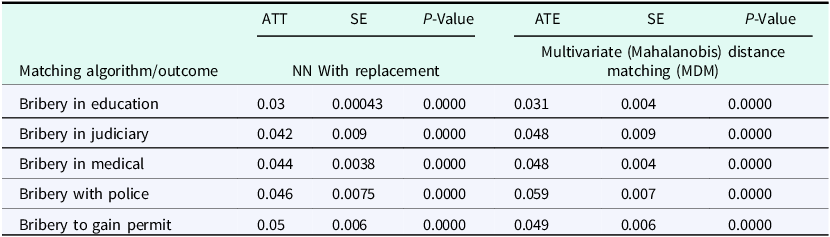

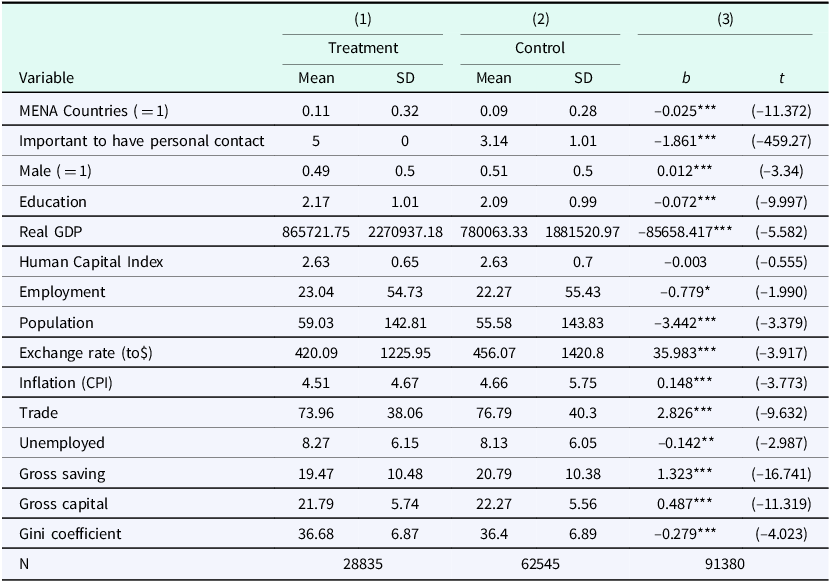

We use propensity score matching (PSM) as the second robustness check for bribery issues, as it helps ensure that individuals who consider personal contact important are compared to similar individuals who do not in terms of several characteristics, reducing selection bias and improving causal inference in estimating its impact on bribery across sectors. The robustness checks conducted through PSM reveal compelling evidence of the impact of examined variables on bribery tendencies across various sectors. The use of the nearest neighbour (NN) matching algorithm with replacement consistently shows positive and highly significant average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) across all outcomes, underscoring a strong association between the treatment variables and an increased likelihood of bribery in different domains. These findings are echoed by robustness checks using the Mahalanobis Distance Matching (MDM), which also exhibit positive and significant average treatment effects (ATE). These consistent results across both matching algorithms validate the observed relationship, confirming the reliability of the findings. Table 3 supports these conclusions, showing significant ATT and ATE values for bribery in education, judiciary, medical, police, and permit-related interactions. The consistency of results across diverse matching methods highlights the significant influence of key factors on bribery tendencies and underscores the necessity to address systemic determinants to mitigate bribery’s prevalence.

Table 3. Propensity score matching (NN & MDM)

Policy recommendations and conclusion

This paper examines corruption and informal practices in the MENA region compared to the rest of the world. The findings indicate that informal practices such as wasta, hamula, and combina are not merely peripheral but play a central role in shaping bribery and corruption across various sectors. These networks function as adaptive responses to weak institutions, helping individuals navigate inefficient bureaucracies. However, while facilitating access to resources, they also reinforce corruption by perpetuating favouritism and limiting opportunities for those without personal connections (Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo, Reference Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo2017). Given their dual role, reforms should not focus solely on eliminating these practices but on providing structured, transparent alternatives that fulfil their social functions.

The results show that anti-corruption strategies must consider the cultural and institutional factors that sustain informal networks. Conventional policies that rely only on stricter regulations or increased enforcement often fail because they do not address why people rely on informal networks in the first place. Instead of assuming that legal and institutional reforms will automatically reduce these practices, policymakers should develop solutions that integrate informal networks into transparent governance structures while ensuring that formal institutions are capable of meeting public needs fairly and efficiently (Oukil, Reference Oukil and Ramady2016).

A more effective approach requires sector-specific interventions that target how informal practices enable corruption in different areas. In education, admissions and hiring processes should be made transparent, and publicly available guidelines should prevent personal connections from influencing decisions. Expanding scholarship programs and financial aid can provide fair access to educational opportunities. In the judiciary, strengthening judicial independence and creating anonymous reporting mechanisms can reduce favouritism. Publicizing court rulings and case updates can further increase transparency and accountability (Meron, Reference Meron2021). In healthcare, implementing queue management systems and maintaining digital medical records can help prevent preferential treatment, while ensuring that hiring processes for medical professionals are based on merit rather than connections. In law enforcement and administrative services, digitalizing processes such as fine payments and permit applications can reduce opportunities for bribery by limiting direct interactions between citizens and officials (Mohieldin et al., Reference Mohieldin, Amin-Salem, El-Shal and Moustafa2024).

Instead of seeking to dismantle informal networks completely, policies should focus on transforming their beneficial aspects into formalized and accountable structures. One way to achieve this shift is to replace informal employment referrals with structured mentorship programs that provide career guidance through institutionalized frameworks. This would allow individuals to access professional opportunities without relying on personal favours while maintaining the support that these networks provide.

Expanding digital governance initiatives can further reduce the influence of informal networks by limiting human discretion in decision-making processes. Adopting e-government platforms, such as digital case tracking for judicial proceedings and automated public service applications, can enhance transparency and accountability. In law enforcement, digital fine payment systems and automated monitoring tools can help reduce bribery opportunities by eliminating the need for in-person interactions (Voigt, Reference Voigt2018).

Reducing corruption in the MENA region requires a gradual transition that combines institutional reform with cultural shifts. Efforts to change social attitudes toward corruption must focus on increasing public confidence in formal governance institutions. Encouraging civic engagement, promoting ethical leadership, and incorporating discussions of integrity and accountability in education can help reshape societal expectations about merit-based access to opportunities. Public awareness campaigns that highlight the consequences of favouritism can further contribute to this shift (Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo, Reference Ledeneva and Baez-Camargo2017).

The persistence of informal networks in the MENA region underscores the need for a balanced anti-corruption approach that does not focus solely on institutional efficiency. Simply strengthening legal frameworks will not reduce corruption unless individuals see clear, functional alternatives to personal networks. Anti-corruption efforts must integrate informal practices into structured, transparent governance models rather than attempting to eliminate them outright.

Understanding how these mechanisms function and when they cross the threshold into corruption can provide more effective and context-sensitive anti-corruption strategies. A phased strategy can help ensure sustainable reform. In the short term, digitalizing administrative processes, strengthening whistleblower protections, and enhancing transparency in government transactions can reduce immediate corruption risks. In the medium term, targeted governance reforms should ensure that alternative mechanisms for accessing resources are widely available. In the long term, broader cultural shifts should be encouraged through education, legal reforms, and civic initiatives that promote fairness and accountability in governance (Oukil, Reference Oukil and Ramady2016).

While this study provides valuable insights, further research is needed to develop better empirical tools for measuring the role of informal networks and to understand how these networks evolve in response to governance reforms. A comprehensive and locally informed approach is necessary to ensure that anti-corruption strategies do not weaken the social stability that informal networks have historically provided (Voigt, Reference Voigt2018).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ObZUifwVh9hC2G3uu67IPXtq6HD8ijtT/view?usp=sharing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Faculty of Economics and Business, Gadjah Mada University, which has provided research grant funding for this research. The funding is from the Collaborative Research Grant, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, with ID 10530/UN1/EK/UJM/LT/2024.

This research is partially funded by the European Union under the European Commission’s Horizon Europe Programme for Research and Innovation, Grant Agreement number 101132483 (Project: BridgeGap). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the granting authority, the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Competing interests

No potential conflicts of interest were reported in this study.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics (MENA)

Table A2. Descriptive statistics (Non-MENA)

Table A3. PSM treatment and control

*** P < 0.01, ** P < 0.05, * P < 0.1.

Fatih Kırşanlı is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Social Sciences University of Ankara. His primary research interests are Political Economy, Institutional Economics and Macroeconomics. He has ongoing projects on corruption, governance, institutional economics, central banking and economics of education.

Dr. Wisnu Setiadi Nugroho is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, and an economist at the Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Cultural Affairs, Republic of Indonesia. He earned his Ph.D. in Economics from Colorado State University in 2022. With over 15 years of experience in research on poverty, social protection, and human development policy, he is a former recipient of both USAID and LPDP scholarships. Dr. Nugroho also serves as the coordinator of EQUITAS (Equitable Transformation for Alleviating Poverty and Inequality Working Group), a multidisciplinary research initiative dedicated to developing inclusive policy solutions for reducing poverty and inequality in Indonesia. His research interests span poverty and inequality, gender economics, institutional roles and corruption, and the impact evaluation of government programs.

Ina Kubbe is a Professor at Tel Aviv University’s School of Political Science, Government and International Affairs, where she focuses on corruption, counter-corruption, cybercrime, gender politics, and conflict resolution. She also teaches at the International Anti-Corruption Academy (IACA) in Austria. Ina co-founded the Interdisciplinary Corruption Research Network (ICRN) and chairs the ECPR Standing Group on “(Anti-)Corruption and Integrity.” She regularly advises organizations such as the EU, NATO, OSCE, and the UNODC.