Introduction

The American K12 education system has long been criticized as centralized and rigid (Strong, Reference Strong2020; Coons, Reference Coons1971), limiting both the development of locally managed school communities and entrepreneurial advances in the K12 education sector. While these arguments continue to have merit, and while the bulk of U.S. schools are still quite centralized, policy and social developments beginning in the 1990s fostered the emergence of several changes which arguably pushed U.S. education in a potentially more polycentric, localized direction and have helped create a new and growing subset of schools that is much more decentralized. Homeschooling became legal in all 50 states during the 1990s. The first charter school law was passed in 1991. The first hybrid schools (in which students attend physical classes a few days per week and are homeschooled the rest of the week) were started in the early 1990s. In more recent years, even more policies and social developments have occurred to localize education, such as a variety of voucher programs, tuition tax credit programs, and education savings accounts programs. Homeschooling in many forms has become more popular, especially since the appearance of COVID-19. Just prior to these changes, in 1991, Gina Davis and Elinor Ostrom published ‘A Public Economy Approach to Education: Choice and Co-Production’ as a sort of analytic narrative of the organization of American schools (Skarbek and Skarbek, Reference Skarbek and Skarbek2023). That work also sought to examine the extent of co-production in American schools to that time, and the extent to which the system was polycentric. This paper seeks to use Davis & Ostrom’s framing and to update their work in the context of current research, policy, and practice in the area of K12 education policy.

The purpose of ‘A Public Economy Approach to Education’ was to create a theoretical framework that could be used to examine various institutional arrangements of American schooling at a high level. The paper challenged the market versus government approach to discussing education policy solutions, arguing that many arrangements are possible with aspects of both, each with its own potential benefits and drawbacks. Davis & Ostrom discuss 11 problems related to the provision and production of education faced by schools. They then describe five possible institutional arrangement, and score each based on each one’s potential to improve or worsen each of the 11 problems.

The first section of this paper will provide a brief update to the progression of education policy and school choice since 1991. The second will examine the 11 issues Davis & Ostrom raised in 1991, with brief examples of the research that has been conducted on each question in the more varied landscape of school choice that has developed since then. The third section of the paper will address polycentricity and co-production in American K12 education, as they relate to the market versus government distinction, re-examine each of five types of school systems Davis & Ostrom describe, and place them in the context of current research and practical developments in education, revisiting each of the models following Davis & Ostrom’s rubric. The final section provides a conclusion and suggestions for further explorations of education policy in light of Ostrom’s work. This work builds on Davis & Ostrom’s work by attempting to place ‘A Public Economy Approach to Education’ in the context of the current landscape – a very different arrangement than existed in 1991.

U.S. education policy comparisons and developments

Student performance

In the United States and other, Anglosphere or similar democracies, education is arranged to include significant participation from private actors, and competition and choice between providers, on the theories that parents should be able to choose schools that fit their preferences, and that this kind of arrangement will generally produce acceptable academic and social outcomes overall (Verger et al., Reference Verger, Fontdevila and Parcerisa2019). Some countries, such as those in Northern Europe, focus more on inputs, and in these cases the state serves as ‘a facilitator of solutions to social problems and is eager to preserve the ideas of civil service and professionalism in public services’ (Verger et al., Reference Verger, Fontdevila and Parcerisa2019, p. 251). Other nations operate on other theories. Centralized, uniform, and hierarchical arrangements include those in Southern Europe and elsewhere. Other attempts to categorize school autonomy, for example (Neeleman, Reference Neeleman2019), or teacher autonomy (Lennert Da Silva, Reference Lennert Da Silva2022) find similar differences in schooling arrangements and the amount of centralization a nation employs in aspects of its educational system. In work relating school accountability regimes to teacher autonomy, Lennert Da Silva characterizes national systems with ‘high-stakes accountability’ (those that require testing and consequences), those with ‘low accountability’ (less testing, or testing with less formal accountability attached), and those with ‘uneven accountability’ (those with arrangements based on political or cultural factors) (Table 1).

Though perhaps more competitive and decentralized compared to other nations, in 1991, Davis and Ostrom argued that ‘poor academic performance by students is endemic’, (p. 314), and that despite a stated preference for ‘local control’, the U.S. in practice had a centralized, ‘one best system’ model of education that had clearly failed. Results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a nationally representative sample of student achievement, show that overall student scores increased in 4th and 8th grade Mathematics since 1990, peaking in 2019 (just before the COVID-19 pandemic), and then declining (NAEP, 2024a). In Reading, scores peaked somewhat earlier in 4th and 8th grade, but then declined after the pandemic and are actually lower than they were in 1992 (though insignificantly so) (NAEP, 2024b). On the OECD-led International Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), U.S. performance followed a similar path of growth and then recent decline. Though the U.S. moved up slightly in the most recent rankings of nations, actual Math performance worsened, and the rise in rankings is due to larger declines in other countries, not increases in American performance (OECD, 2023). American students’ absolute performance peaked in 2018 (similar to NAEP). Since PISA’s debut in 2000, the U.S. has typically been a mid-table performer, with relatively stable result in Reading, but a large decline in Math scores since the early 2000s. Most accounts of U.S. students’ domestic and international academic performance over the past decades are of dissatisfaction.

How polycentric is U.S. education today?

Much of the pieces citing Davis & Ostrom cite that paper as one example of a social issue while actually addressing another issue (usually an environmental issue). Of the papers that discuss Davis & Ostrom specifically in terms of education policy, most do so in the context of co-production (e.g. Soares and Farias, Reference Soares and Farias2019; Alford, Reference Alford2014), or else as part of a discussion about the effectiveness of a particular system of school choice (e.g. Lee and Fitzgerald, Reference Lee and Fitzgerald1996; Parry, Reference Parry1996; Ambler, Reference Ambler1994). This paper is a start at re-analyzing American education policy in light of Davis & Ostrom’s Reference Davis and Ostrom1991 paper, and specifically through discussions of polycentric governance and co-production.

Aligica and Tarko (Reference Aligica and Tarko2012) define ‘polycentricity’ as ‘a structural feature of social systems of many decision centers having limited and autonomous prerogatives and operating under an overarching set of rules’ (p. 237). While American K12 education may superficially have such a feature, Davis & Ostrom criticize the ‘… centralized, bureaucratic model that overshadowed educational reform for more than fifty years’, and the fact that ‘current centralized solutions have failed so miserably’ (pp. 328–329). They do not suggest a particular model as a replacement, but write that ‘The choice is not simply between hierarchy and markets…instead of recommending any particular institutional regime as the panacea for solving educational problems, we recommend that all institutional reforms be viewed as experiments that can inform both participants and others about the array of consequences that may be produced by the adoption of any one institutional regime’ (pp. 328–329). If one is to compare Davis & Ostrom’s criticism to potential alternatives, these arguments imply three questions: first, Does it matter whether the U.S. education system is polycentric? If so, then second: How centralized/monocentric was U.S. education in 1991? And then third: Has this changed since 1991?

First: Why does this matter? The value of polycentric governance has long been discussed in terms of the value it brings to managing environmental resources or other climate-based issues (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012). It has also been discussed as a method for better managing efforts as varied disaster relief (Chamlee-Wright and Storr, Reference Chamlee-Wright and Storr2012; Coyne and Lemke, Reference Coyne and Lemke2011), healthcare policy (Ostrom and Parks, Reference Ostrom and Parks1999), and space exploration and governance (Tepper, Reference Tepper2019). Several authors discuss education as a common pool resource (Gyuris, Reference Gyuris2014), or as both a common resource and (by implication) a public good (Frischmann, Reference Frischmann2009; Hess, Reference Hess2008). The value polycentric governance brings to these other commons areas comes in multiple forms. In each case, polycentric governance allows for (1) Adaptability (multiple decision centers able to quickly adjust to local conditions or new challenges); (2) Resilience: (overlapping jurisdictions reduce the risk of systemic failure); (3) Innovation (competition and experimentation among actors helps drive creative solutions; and (4) Appropriate Scale (management of a problem leverages local knowledge and ability to deal with a problem, avoiding one-size-fits-all approaches). K12 education could similarly benefit from a system that adopted these principles, and on the surface, seems like it might already be such a system.

Strong (Reference Strong2020) actually addresses the second and third questions above by specifically and directly asking: ‘Is the U.S. education system adequately polycentric?’ He answers by describing the system as requiring ‘secular, age-graded schooling’, as well as state teaching licenses and Carnegie-unit credits, and operating as ‘a rigid system that is based exclusively on the transmission of knowledge and skills’ (pp. 246–247). His arguments will be discussed in greater detail below, but his main conclusion is that the current, dominant system of public K12 education is functionally extremely monocentric. The overarching model has not changed much since 1991, though there have been some developments that are relevant.

Emerging reform models

Charter schools, which emerged soon after the publication of Davis & Ostrom’s paper, were intended to be something of a third way between hierarchical conventional school systems, and a free market approach. These schools allow for more flexibility in hiring, curriculum, and other operations, and may be run by private entities, but are still approved and funded by government actors. Homeschooling also solidified its place in the American educational landscape, becoming formally legal in all 50 states during the 1990s (Kunzman and Gaither, Reference Kunzman and Gaither2020).

At the turn of the century, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) carved out a larger federal role in education policy, promising increased funding for increased testing and transparency. In conventional public schools, a consensus emerged among states on reporting more data publicly and using those data to hold schools accountable, most clearly embodied by NCLB. If charter schools and homeschooling dispersed decision-making in education, the result of NCLB was to re-centralize and re-homogenize it at a higher institutional level. As NCLB was becoming unpopular nationally, conventional schooling moved to widespread adoption of the Common Core State Standards, and many private schools followed along, also adopting those standards (or some versions of them) as their own. Many states have walked back from this, at least in name.

Private school choice programs such as tuition tax credits, in which state-approved entities can accept tax donations from individuals or corporations and then hand those funds back out as scholarships became more popular in the 2000s. More recently, Education Savings Account (ESA) programs have passed in several states, and as of 2025, 20 such programs existed in 17 states (EdChoice, 2025). These allow families to receive a portion of the per student funding that would otherwise be directed to conventional public schools and use those funds for a variety of purposes (EdChoice, 2024b).

Hybrid schools and microschools had been in existence since at least the early 1990s (Wearne, Reference Wearne2020). Hybrid schools are those in which students attend physical classes fewer than five days per week and are homeschooled on the other days (as opposed to homeschool co-ops, in which students usually choose all of their classes a la carte, hybrid schools tend to have more structure, and these student may or may not be formally considered ‘homeschoolers’) (Wearne, Reference Wearne2020).

Microschools can have many practical expressions but are generally simply schools with very small enrollments (often 10 students or fewer). This sector had been growing faster in the 2000s and 2010s, but microschools and hybrid schools have grown in popularity even more since the onset of COVID-19. These entities might be private, charter, or, in some cases, programs within conventional public schools. Hybrid and microschools as institutions represent the most polycentric development in American education over the last few decades, and this sector will be discussed in more detail below.

School choice market share

Private school choice programs have grown from fewer than ten in 1991 to over 80 by 2023. The number of students using education savings accounts (ESAs), tuition tax credit scholarships, or some form of vouchers has grown from zero in 1991 to over a million in 2024–25 (though this is still a fraction of the total school age population) (EdChoice, 2024a). Homeschooling grew notably during the pandemic years. According to federal data sources, homeschoolers made up between 3.4 and 5.2 percent of U.S. students in 2022–23, depending on how ‘homeschooling’ is defined (NCES, 2024), an increase from 2.8 percent in 2019 (NCES, 2022). Much of this growth has been seen across the south and the mountain west. Since the pandemic, three states have seen continuous growth in homeschooling (Louisiana, South Carolina, and South Dakota), while sixteen other states saw their homeschooling numbers grow during the pandemic, drop as schools reopened, and are now seeing rebounds (Watson, Reference Watson2024). As a whole, the school choice landscape is much more dispersed than it was in 1991. According to EdChoice (2024b), in 2024:

-

(1) 74.6% of students attended a traditional public school.

-

(2) 6.8% attended private school by means such as paying tuition.

-

(3) 6.6% attended a charter school.

-

(4) 4.9% attended a magnet school.

-

(5) 4.7% were homeschooled.

-

(6) 1.9% of students used some other form of educational choice program.

State by state, the share of students in conventional, assigned public schools today ranges from a high of 93.4 percent in Wyoming – which passed a bill in 2025 creating a new universal school voucher program, and which will provide families with up to $7,000 per child annually to cover K-12 non-public school costs, such as private school tuition or tutoring (Klinsporn, Reference Klinsporn2025) – to a low of 32.8 percent in the District of Columbia.

Overall, the story since 1991 is one of several attempts at decentralizing schools, alongside concurrent attempts to centralize them in new ways. Ultimately the conventional, largely monocentric system still accounts for the vast majority of student enrollment, though that share is less than it was in 1991.

Re-examining the 11 problems

Any arrangement a nation or state chooses for its schooling landscape will necessarily involve tradeoffs in terms of equal opportunity, principal-agent problems, and a host of other regulation-related issues. Davis and Ostrom cover eleven problems regarding education: six regarding the provision of education, and five regarding the production of education. They envision potential issues with various forms of school choice regimes, though none truly existed at the time of their writing.

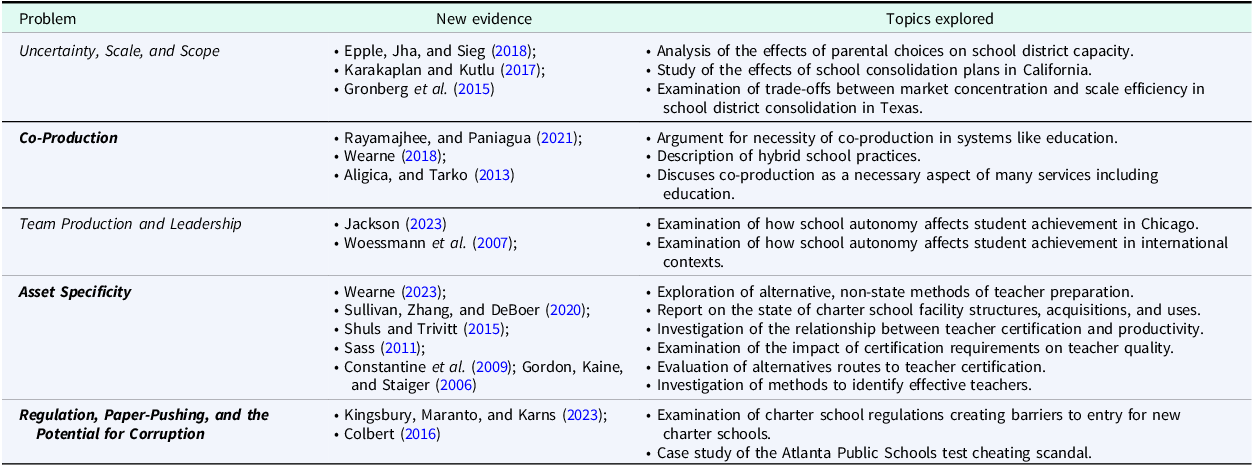

Tables 2 and 3 report the 11 problems identified by Davis & Ostrom, along with some of the relevant work (though not an exhaustive list) that has been conducted on each topic in the time since. The first set of problems deal with providing education. Following Table 2 is a discussion of some of the problems which are most relevant to current education policy in the areas of provision identified by Davis & Ostrom.

Table 2. Updates on institutional incentives and problems of providing education

Table 3. Updates on institutional incentives and problems of producing education

Updates on institutional incentives and problems of providing education

Direct Benefits, Exclusion, and Equity. ‘Given that the direct benefits of education are subject to exclusion, any institutional arrangement that relies primarily on private rather than public provision generates inequities over time’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991, p. 321).

The ability of schools of choice to exclude certain students, and the overall effects on equitable distribution of educational opportunities has continued to be a concern of many researchers. Davis & Ostrom note the likelihood that more private arrangements will be more exclusive as a problem for voucher and other choice-based systems.

Egalite and Wolf (Reference Egalite and Wolf2016) argue that choice programs may actually have reduced segregation in many cases, though the outcomes of specific programs should still be monitored: ‘Because of widespread existing residential segregation, the use of a voucher actually allows students to exit highly stratified traditional public schools, potentially reducing racial stratification’ (p. 450). In international contexts, increased economic freedom has led to increased access to quality schooling (De Soysa and Vadlamannati, Reference De Soysa and Vadlamannati2023).

Measurement and Asymmetric Information. ‘Since the outcomes of education are frequently difficult to measure, input measures are frequently used as proxies for outcomes. Relying upon such proxy measures as the money spent per pupil or the educational attainment of teachers is unreliable…Not only is information about educational outcomes difficult to obtain in general, severe asymmetries of information exist between consumers and producers’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991, p. 322).

Information about particular schools’ performance is more available and accessible than it was in 1991, but this may not have a major effect on the choices families make. Kisida and Wolf (Reference Kisida and Wolf2010) find that parents in private schools of choice reports higher satisfaction and perceive their schools as higher performing than public school parents. However, this study does not find that parents in schools of choice are objectively better informed. For example, choice of parents may be more optimistic about choices they have made, while public school parents, though less satisfied, sometimes have perceptions that are more aligned with objective measures about their schools (such as test scores). The authors suggest that this finding may indicate that more information alone does not inherently improve choices, but with poor information, market-driven reforms will be even less likely to optimize education quality.

A major event since the publication of ‘A Public Economy Approach to Education’ was the federal No Child Left Behind Act. This Act did increase the amount and accessibility of information about school performance. Ladd (Reference Ladd2017) summarizes NCLB’s results on academic achievement as creating a ‘Moderate and statistically significant increase in test scores in math for 4th-grade students and a positive, but not statistically significant, increase for eighth graders in math, with no effects on reading scores for students in either grade’ (p. 463). NCLB’s testing requirements became increasingly unpopular and federal education policy has moved on, but the publication of significantly more data, and more disaggregated data, than had been done previously, is often still noted as one salutary effect of the law.

Funding and formal accountability aside, part of the concept of NCLB was simply to provide the public with more information about school performance, and reformers have sought to provide more information to parents in other ways as well. Groups like GreatSchools, for example, are still trying to solve the issue of providing parents with more information. Hastings and Weinstein (Reference Hastings and Weinstein2008) find that providing information does affect student choices, but that providing such information is costly. Corcoran et al. (Reference Corcoran, Jennings, Cohodes and Sattin-Bajaj2018) also find that providing information affects student choices, but that having new information generally does not reduce inequality. Consistent measurement is made more difficult in more varied systems, and this problem is arising again as American education moves from the centralized NCLB model to a more distributed hybrid and microschool model, in which schools offer a wider variety of standardized assessments (or none at all). NCLB’s successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) moved away from federal mandates and toward a more state-based system for designing accountability, though ESSA in practice mainly reined in some of NCLB’s overreach, and stands as a somewhat pragmatic correction, rather than a true nod toward local control of schools.

Though policy has moved away from using standardized tests for strict accountability, society still values them, and the study of this phenomenon at a large scale is new since 1991. Test scores, per-student spending, and student–teacher ratios all affect home values (Brasington, Reference Brasington1999). Student scores have been repeatedly shown to affect the housing market (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger, Reference Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger2011), although a more recent meta-analysis of this topic suggests no one measure of school quality as a driving factor (Turnbull and Zheng, Reference Turnbull and Zheng2021).

Principal-Agent relationships, Voting, Agenda Control. ‘Except under extremely unusual circumstances, voting mechanisms do not automatically translate diverse citizen preferences into well-defined preference orders for a community’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991, p. 322).

These issues remain. Maranto (Reference Maranto2018) writes, ‘In theory, public schools are open systems citizens can influence through voiced opinions, voting, running for office, and the courts. The real world of public school governance is more complex. Pluralism in state capitals and even in school district offices privileges organized interests over parents. Local public education leaders, including school board members, may limit information, appeal to community loyalties, intimidate critics, and use highly specialized language to limit and channel citizen influence’ (p. 154). Hartney (Reference Hartney2022) and Krinsky (Reference Krinsky2014) also mention outsized teachers unions influence as a problem. But school boards themselves may simply be ineffective in representing students and their families. Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz (Reference Kogan, Lavertu and Peskowitz2021) document ‘considerable demographic differences between voters who participate in school board elections and the students attending the schools that boards oversee’ (p. 1082). Kogan (Reference Kogan2022) also suggests that school board races and decisions will over time become even more dictated by non-parents as the American birth rate declines.

Updates on institutional incentives and problems of producing education

The problems above involve the context and intended outcomes of education. The second set of problems considers the actual provision of schooling. Table 3 reports new evidence on this set of problems, followed by a discussion of some of them.

Co-Production. ‘Educational services cannot be produced by a school alone. The production of education requires the active participation of students and their parents in production’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991 p. 324).

Davis & Ostrom note the growing understanding of the importance of the concept of co-production in education going back to the Coleman Report (Coleman, Reference Coleman1966) and continuing into the 1990s. A particularly stark example of this concept has arisen since 1991 is the emergence and growth of hybrid schools, as parents and schools have taken on the co-production of education much more explicitly and designed school experiences around it (Wearne, Reference Wearne2020). Most conventional schools will seek good relationships with families, while taking on the responsibility of education themselves; hybrid schools take the concept of co-production and require it of their families. Many families describe hybrid schools as ‘the best of both worlds’, (Wearne, Reference Wearne2018), combining homeschooling with in-class settings. By their nature, hybrid schools (and similar homeschool co-ops and many microschools) are explicit examples of co-production, with parents both educating their children and serving as the founders/administrators/teachers of their schools. Co-production of education is in fact one of the biggest changes in American education since COVID, as evidenced by the growth in homeschoolers and related new school models, created and run by parents and/or local community groups.

Asset Specificity. ‘Schools are usually constructed in a way that limits their usefulness for other purposes. Thus, most schools must own and construct their own buildings rather than lease space from a private owner…[and] Many regulations passed by state boards of education require highly specific types of training before individuals can qualify as teachers. This tends to lock in those individuals who choose to obtain educational credentials since these credentials do not prepare them as generally for other kinds of careers. Further, these regulations tend to lock out others who might make highly motivated and well-trained teachers’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991 pp. 325–326).

American public schools are in fact quite constrained in their uses. Charter schools, which arose after Davis & Ostrom’s publication, do have more flexibility in locating facilities than do conventional public schools, though this means they also face a different set of challenges (lack of access to existing buildings, lack of dedicated funding streams for buildings, higher costs, etc.) (Sullivan, Zhang, and DeBoer, Reference Sullivan, Zhang and DeBoer2020). The lack of adequate facilities has been ameliorated over time in several states. In Georgia, for example, the Georgia Charter Schools Act was amended to require public school systems to offer unused space to charter schools, resulting in significant cost savings to the charter schools.

Davis & Ostrom’s statement about teacher certification and training has been repeatedly supported in the years since their paper was published. A large study of teachers in Los Angeles found that formal state certification was largely irrelevant to teachers’ future effectiveness (Gordon, Kaine, and Staiger, Reference Gordon, Kane and Staiger2006). Studies in Arkansas (Shuls and Trivitt, Reference Shuls and Trivitt2015), in Florida (Sass, Reference Sass2011), and in various other states (Constantine et al., Reference Constantine, Player, Silva, Hallgren, Grider and Deke2009), have found the same. Issues around teacher training and certification have become increasingly relevant over time, as many new school models have emerged and have sought out teachers with a wider variety of knowledge and skills. New models of teacher preparation and certification have emerged since 1991 that either did not exist or were extremely limited at that time (Wearne, Reference Wearne2023) and which may affect the universe of potential teachers.

A significant literature has emerged since 1991 on teacher value-added measures (VAM), which attempt to link student outcomes to individual teachers. This work began in earnest during the 1990s (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Wright and Horn1997). Chetty et al. (Reference Chetty, Friedman, Hilger, Saez, Schanzenbach and Yagan2011) find that students with higher-quality teachers show higher earnings, higher college attendance rates, and improvements other outcomes. Hanushek (Reference Hanushek2011) also finds a wide variation in teacher quality and suggests that replacing the bottom 5–8 percent of teachers with higher performers would move the U.S. to the top of the rankings on international assessments. There has been significant debate, however, on the design of these models (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2010, Reference Rothstein2009), and questions on whether these teacher effects fade out over time (Kaine and Staiger, Reference Kane and Staiger2008), limiting their implementation in practice.

Regulation, Paper-Pushing, and the Potential for Corruption. ‘…the imposition of many different requirements and the need for repeating filling out complex forms that affect future funding levels can generate highly counterproductive behavior…If funding formulae are based on certain data, school administrators who desire higher funding levels are strongly motivated to find means of increasing those figures that positively affect funding and decreasing those figures that negatively affect funding, whether or not the resultant actions actually improve performance’ (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991 p. 326).

No Child Left Behind generated enormous numbers of new requirements for local public schools. Beyond reporting requirements, many school leaders felt pressure to focus on standardized test results to the exclusion of other educational outcomes. As might have been predicted by Campbell’s Law (Reference Campbell1979), this approach also generated incentives for distorted readings of school outcomes and even potentially criminal behavior (Colbert, Reference Colbert2016). The charter school sector arose in the early 1990s and grew with the understanding that charter schools would be given additional freedom of action, in exchange for producing results (typically standardized test scores). As public schools, they were also subject to NCLB’s requirements. However, as the charter school sector has evolved, that sector has seen a growth in regulatory barriers for new charter schools, which has hampered its ability to continue to manifest creative schools (Kingsbury, Maranto, and Karns, Reference Kingsbury, Maranto and Karns2023).

School choice has grown immensely since 1991. Much of the more recent research in this area – on equity, on financing, on information availability – shows that school choice can somewhat mitigate several of the problems Davis & Ostrom mention in 1991. Some of the developments in the provision aspects of schooling – the emergence of charter schools/other forms of school autonomy, and alternative pathways to teacher preparation and certification – suggest that some provision problems may be in a better state now than in 1991 as well. Other issues may be worsening though: the principal-agent problem may be getting more complicated; parents have more choices, but school boards may be becoming less representative of their constituents. And Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2002) herself criticized the continued consolidation of schools and school districts, arguing that at first the policy of consolidation was based on assumptions rather than evidence, but that the evidence had accrued to suggest that consolidation was actually likely harmful to student performance.

Re-examining five alternative institutional regimes

Five regimes

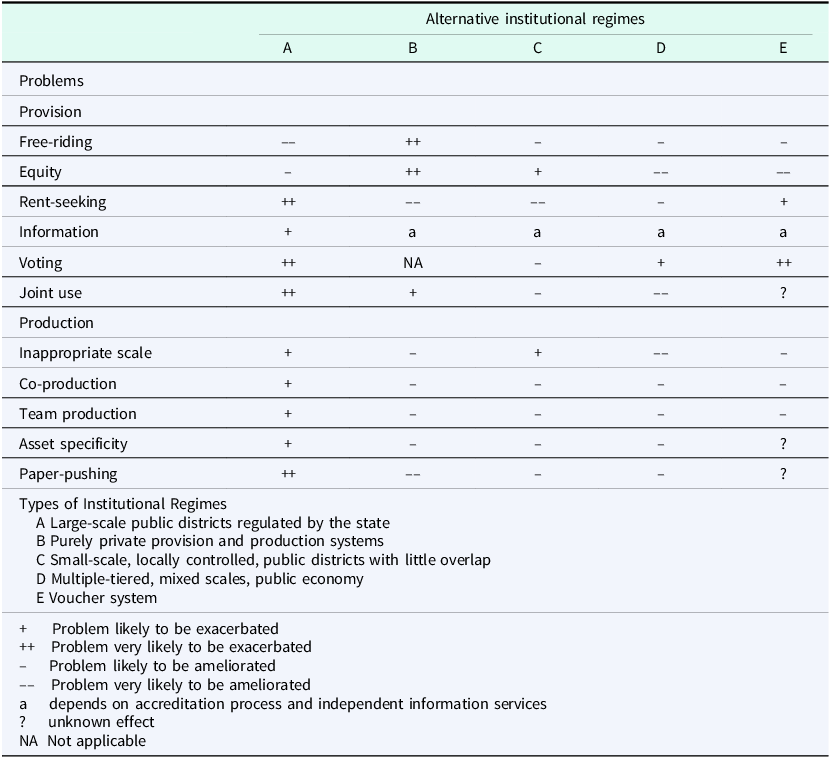

The question of whether developments in the school choice sector are ‘exacerbating or ameliorating’ problems (Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991) will be discussed in this section. In their original paper, Davis & Ostrom describe possible five institutional regimes and then score them on each of the 11 problems noted above, in terms of whether each arrangement makes each problem worse or better. The regimes, per Davis & Ostrom’s descriptions, are

Column A: ‘large-scale school districts that are heavily regulated by state educational bureaus’

Column B: a ‘purely private’ market system

Column C: ‘small-scale, locally controlled, public districts that are horizontally organized without overlapping governmental funding or access to larger-scale production units. Column C could be thought of as the type of educational system that existed in the United States before the turn of the [20th] century’

Column D: ‘a multiple tier system including large-, medium-, and small-scale enterprises organized in both the public and the private sector’

Column E: ‘a voucher system whereby the provision of education is shifted to a state level that then funds private and public schools in light of the number of students they attract, and other attributes designed by the state’ (in other words, a heavily regulated, publicly-run system of choice) (Table 4)

Table 4. Likelihood of alternative institutional regimes exacerbating or ameliorating provision and production problems

Adapted from Davis and Ostrom, Reference Davis and Ostrom1991.

In order to address how to re-assess the five regimes based on more current research, another relevant question should be asked again: Is the U.S. education system actually polycentric?

In the clearest discussion of this question, Strong (Reference Strong2020) argues that it is not. Strong writes that despite some polycentric attributes (district-level governance, for example), the U.S. education system is a severely constrained, monocentric system that prevents evolution and adaptation. Expectations such as seat time requirements, sequenced, grade-level advancement, Carnegie-style awarding of credits, and the expectation of hiring government-certified teachers are all aspects of the dominant system of American schooling which are so ingrained across the nation that they wash out the benefits of the minor polycentric attributes the system might have. He suggests that ‘A key advantage of polycentric systems is that they allow institutions to evolve according to different values and objectives and thus allow for the emergence of new institutions that attract those whose needs are more fully met by the newer institutions’ (p. 235). The kinds of education that Strong believes are prevented from emerging by the dominant system are those that involve 1. Distinctive virtue cultures, 2. Learning systems optimized for autodidacticism, and 3. Radical variation in the time, pacing, or style of learning. Strong’s analysis is correct in that the expectations he describes are defining aspects of American schools, and institutions that ignore them too much could likely not emerge from that system. A conventional American school could not, for example, simply choose a ‘distinctive virtue culture’ and implement it, nor could it optimize itself for students to teach themselves at their own paces; they could not allow students to deviate too much from the required course curriculum on an individual basis. Conventional schools do sometimes engage in small-scale experiments with variation in the time/pace/style of learning, but in very limited ways. The dominant public system is clearly functionally monocentric, as Strong concludes. Outside of that system, however, new institutions have emerged specifically to address Strong’s three items.

‘Community crafted education’ as case study

Wearne (Reference Wearne2024) describes the sector of schooling, mostly consisting of either private schools or of organized collections of homeschoolers, which exists between full time homeschooling and conventional, five-day schooling, as ‘community crafted schools’ (or ‘community crafted education’). These arrangements include hybrid schools and microschools. These schools (or schooling experiences, in many cases) diverge from the norm either in terms of time (hybrid schools) or size (microschools), or both. In practical terms, whatever their arrangements, many of these schools are built on state homeschool laws, and many of their students register with their states as ‘homeschoolers’. They appear to be somewhat more common in areas where homeschooling was already more popular (the south, through Texas), though they can be found across the U.S. (Wearne and Thompson, Reference Wearne and Thompson2023).

Very often these schools are started in response to one or more of the problems Strong names. Hybrid schools especially are often set up to promote ‘distinctive virtue cultures’. Many hybrid schools are explicitly religious, although the share of secular hybrid schools is rising as the model becomes more popular post-COVID. Microschools are often set up with a ‘learner-directed’ approach, answering Strong’s statement that many students need ‘learning systems optimized for autodidacticism’. Conventional schools are simply not set up to make this kind of learning possible, as Strong notes. And both hybrid and microschools experiment in a variety of ways by using ‘radical variation[s] in the time, pacing, or style of learning’.

Coons (Reference Coons1971) describes the sort of community that enables these kinds of schools as

an interacting group of people with shared values and/or a willingness to cooperate to attain long range objectives. This definition has no geographic content; indeed, the congruence of any such community and a defined locale may be relatively rare with the obvious exception of the traditional family. One hesitates to call such communities ideological, since the informing values may be cultural, social, or simply practical… (p. 848).

One reason such communities may form more easily or more quickly now than they did in 1991 is because of advances in technology. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is one aspect of education that is quite different than it was in 1991, and in some ways helped spark the adoption of community crafted education (Wen et al., Reference Wen, Gwendoline and Lau2021). As noted above, these schools are typically built on their state homeschool laws, allowing for innovation in the time and types of spaces their schools use. Online communities of homeschoolers grew significantly during the 2000s–2010s, and improvements in distance learning technology itself allowed for more students to study from home, either part- or full-time. This accelerated during the pandemic, but hybrid schools especially were well positioned to weather the initial problems and school shutdowns, as their teachers had had practice, and had structures available to provide home-based lessons, and students had practice working at home. In fact, hybrid school leaders report that they feel they dealt with COVID much better than did their conventional school neighbors (Wearne, Reference Wearne2021).

Polycentricity in community crafted education

The emergence of these schools fits very neatly within Ostrom’s concept of polycentricity. As she notes, ‘we are not limited…to only the conceptions of order derived from the work of Smith and Hobbes. A polycentric theory offers an alternative that can be used to analyze and prescribe a variety of institutional arrangements to match the extensive variety of collective goods in the world’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1998, p. 14). And in fact, though many of these schools are fully private institutions, a number of the newer ones especially are wholly or nearly wholly dependent on government funding, if not government provision – charter hybrid schools, in terms of per student funding, and any school that relies on funds from education savings account programs.

No conventional school system would preemptively suggest that it open a school of ten (or fewer) students, or that a school should be open for classes two days per week and provide lesson plans for parents to help students through the other three. And homeschool laws were not passed with the intention of creating them. Yet these models and many variations are what have actually evolved in the American schooling landscape over the past few decades. Aligica and Boettke (Reference Aligica and Boettke2009) write, ‘…it is clear that no central planner could purposefully design a system of polycentric governance to function in the way that it does in fact operate…Rather, the main idea is that there are unintended consequences to purposeful human action. These unintended consequences play a significant role in constituting the overall order of the system.

As a result, what is needed is a set of institutions that allows individuals to act purposefully and make adjustments to the unintended consequences of those actions’ (p. 102). These community crafted schools seem to be just such institutions, operating mostly outside of the conventional system, and making adjustments to best suit their needs, especially in light of many families’ dissatisfaction with their school experiences during and after COVID. Other nations have seen an increase in school choice, combined with their national curriculum and teacher training programs, lead to problems with teachers, a narrowing of the curriculum and worse school performance (Henrekson and Wennström, Reference Henrekson and Wennström2019). In the United States, however, the proliferation of charter schools and public or private hybrid and microschools has led to a proliferation of curriculum types, rather than a narrowing. To serve these schools, teacher preparation in the United States has also been moving in a more varied direction (Wearne, Reference Wearne2023).

Co-production in community crafted education

Education is clearly an effort that requires co-production to be its most effective. Davis & Ostrom note the importance of the Coleman Report, and Elinor and Vincent Ostrom note that the quality of educational services are ‘critically affected by the productive efforts of students as users of education services’ (Ostrom and Ostrom, Reference Ostrom and Ostrom2019, p. 20). These community crafted schools often use co-production as a design feature, asking parents to actually teach their children for some percentage of the week, rather than taking on the entire task themselves (as with conventional schools) or having parents do it all (as with full time homeschooling). Many of these schools, and especially the hybrid schools, having evolved from the full time homeschooling sector (Kunzman and Gaither, Reference Kunzman and Gaither2020), have explicitly chosen to add co-production to their schooling models.

Regime types revisited

These community crafted schools do not fit in with and have historically not been created by large, monocentric school systems (Regime A, in Davis & Ostrom’s parlance). To the extent today’s dominant system looks like Regime A, it seems to behave as Davis & Ostrom describe, ameliorating or exacerbating problems as they said in 1991, though perhaps the amount of rent-seeking, paper-pushing, and certification requirements in this sector has actually become worse with more efficient data collection. Voter representation has certainly changed for the worse in large school systems, as noted by Kogan (Reference Kogan2022).

These hybrid and microschools are also not purely private entities (Regime B), as there are a number of charter school versions of hybrid schools. However, contra Davis & Ostrom, more market-driven systems do not seem to produce inequities to the extent they expected (unless one defines ‘equitable’ outcomes as ‘identical’ outcomes, rather than as an increase in overall opportunities). Many of the earliest hybrid and microschools were private, but a growing number are either charter schools, or make use of ESA funding (these may still be private entities, but they face more state regulation).

Regime C – small scale 19th century American schooling – seems clearly off the table, as school system consolidations continue, and private actors grow to serve various markets. Charter schools might in some ways fill this niche as government entities, but they are still exclusive to some extent. A nationwide system of small, local, government districts seems to be an arrangement of the past.

Some state-level school choice programs do look more like Regime E – a heavily regulated, state-funded voucher-style program – as they are administered at the state level, and, as Davis & Ostrom postulate, have some issues that are caused by being administered at the state level, and some that can only be judged based on the particularities of each specific program. Student eligibility, program scope, and other issues vary widely across these programs and make simple characterizations difficult.

Hybrid schools, microschools, and other types of community crafted school models arguably fit best as Regime D: ‘a multiple tier system including large-, medium-, and small-scale enterprises organized in both the public and the private sector’. To the extent today’s schooling landscape looks more like Regime D, that may be a salutary development overall. Davis & Ostrom write in their conclusion, that ‘Enabling parents and other citizens greater opportunities to craft institutions themselves rather than limiting parental choice to options within institutions chosen for them may generate even better institutional regimes in the future than any conceived of by the professional educator or institutional analyst…’ (p. 329). This is an accurate description of the way these community crafted schools organize themselves and operate. Community crafted schools do seem to ameliorate the problems Davis & Ostrom predicted such an arrangement would, while making few issues in the current system worse. They are the new institutions that Strong deems impossible to emerge from the existing system, but which he suggests could (and do) emerge from outside it.

Conclusion and future possibilities

American education policy and practice seems to be evolving, though unevenly, in a more polycentric direction since 1991. The ability of communities and individual families, to craft educational arrangements at smaller scales, with decentralized power over them, has grown in the ensuing years. School choice policies began to expand just at the time of Davis & Ostrom’s original paper. Over time, Ostrom continued to discuss the lack of support for centralization in education (as in other areas) and for increased polycentric governance and co-production in this field. In 2010, Ostrom argued, ‘The presumption that there are very substantial economies of scale related to K-12 education is again grossly overexaggerated and applied uniformly to all aspects of producing education’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010, p. 112). And the field is evolving away from that presumption. Increases in the social popularity of homeschooling from the 1990s to today, along with improvements in technology, and a growth in work-from-home opportunities had already led to an increase in an alternative, more polycentric system of American education outside of the dominant system, with co-production as a more central feature of the enterprise. The subpar experiences many families had with their schools during COVID led to fast, large increases in this sector, and a growing market for both full time homeschooling and community crafted models. This is somewhat anecdotal, however, and a more empirical investigation of the ‘relative trust’ (Leland et al., Reference Leland, Chattopadhyay, Maestas and Piatak2021) people have in various levels of government on the issue of the provision and regulation of K12 education would be worthwhile. But the fact that the foundation had been laid during the 2000s–2010s allowed such fast and large-scale self-organized, self-corrective institutional change to happen over the past few years during and after COVID. Davis & Ostrom’s five regime descriptions do mostly hold up in light of the research that has been conducted on school choice programs in the intervening years, and though they do not recommend a particular regime, the most salutary regime in their discussion seems to be the one that is currently developing. Elinor and Vincent Ostrom’s larger work on polycentricity and co-production in institutions is a rich theoretical and empirical approach that has yet to be fully considered regarding education policy. Revisiting ‘A Public Economy Approach to Education’ is intended as a step in that direction.