Introduction

In recent decades, informal housing – a form of accommodation operating outside the formal housing market with low compliance with institutional regulatory systems (Durst and Wegmann, Reference Durst and Wegmann2017; Gurran et al., Reference Gurran, Maalsen and Shrestha2022; Harris, Reference Harris2018) – has been proliferating in urban areas globally (Tonkiss, Reference Tonkiss2014). Globalisation and international migration have led to the rapid expansion of the urban population, thereby intensifying housing unaffordability in megacities and pushing low-income tenants to the informal sector (Harris, Reference Harris2018), which often adheres to limited regulatory compliance (Gurran et al., Reference Gurran, Pill and Maalsen2021). Informal housings are often inadequate dwellings that are in dilapidated conditions and involve unauthorised constructions, undermining the physical and mental well-being of occupants (Chan, Reference Chan2023; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Lai, Hoi, Li, Chan and Sin2024; Lombard, Reference Lombard2019). In certain regions, informal settlements are in prime urban areas designated for infrastructural and commercial development and are consequently deemed obstructions to urbanisation (Zhang, Reference Zhang2011). Governments deploy various approaches to manage the informal housing sector and its actors, such as demolition, rehabilitation, resettlement, upgrading, formalisation, and toleration (Gurran et al., Reference Gurran, Pill and Maalsen2021). As governments’ interventions depend on particular socio-economic and political circumstances, comparing interventionist approaches could yield a deeper understanding of the political–economic and sociocultural contexts that structure policy decision-making (Ren, Reference Ren2018), including political regimes, state governmentalities, economic structures, and sociopolitical power (Grashoff, Reference Grashoff2020). However, a relatively less within-nation comparison examines the contextual factors leading to different policy approaches and outcomes. To enrich the existing comparative literature, this study focuses on subdivided units (SDUs) in Hong Kong (HK) and urban villages (UVs) in Guangzhou (GZ) to investigate the regulatory regimes on two forms of informal housings in two major cities in China.

To capture the complexity in the governance of urban informality, we employ a critical policy discourse analysis (CPDA) to compare the intervention policy and discourses devised by the two governments, examining how institutional settings distinctly structure the changes in policy discourse and measures in terms of policy goals, interventive measures, and state-market-society relations.

Literature review

Emergence of global housing informality

While housing informality has become a global phenomenon in recent decades, informal housing in the Global South and Global North exhibits unique features. Informal settlements in the Global South are often constructed in communities with dilapidated conditions and insufficient access to basic utilities, infrastructures, and social services, and are more vulnerable to crime, violence, or natural disasters (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Lombard and Mitlin2020). In many cases, informal settlements were self-built dwellings by residents on occupied lands without authority’s approval, such as slums, favelas, and squatters. Residents have to cope with frequent evictions and displacement resulting from demolition and redevelopment (Ren, Reference Ren2018).

Meanwhile, informal housing in the Global North is closely associated with the formal housing market and neoliberal housing systems in highly developed economies. Although many informal dwellings are unauthorised constructions built by property owners in hidden places, they are not necessarily illegal (Durst and Wegmann, Reference Durst and Wegmann2017; Gurran et al., Reference Gurran, Maalsen and Shrestha2022). Property owners monopolise the rights over the dwellings, whereas tenants are subject to minimal legal protection (Harris, Reference Harris2018). Tenants of informal dwellings often endure substandard housing conditions, such as limited space and poor facilities, in exchange for lower rent (Leung and Yiu, Reference Leung and Yiu2022; Tanasescu et al., Reference Tanasescu, Chui and Smart2010). Examples include unauthorised garage units, shed housing, basement suites, and SDUs (Gurran et al., Reference Gurran, Pill and Maalsen2021; Lombard, Reference Lombard2019). In response to the proliferation of informal housing, governments in the Global South and the Global North have implemented various interventionist approaches specific to the contextual characteristics of housing informality and the sociopolitical structures in their respective localities.

Intervention approaches for informal housing

Several interventionist approaches are commonly seen to address informal housing. The most forceful approach is eviction and demolition, which refers to the mandatory removal of illegal or unauthorised constructions, often in the name of enhancing public interests and advancing urban development (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang and Webster2013). A typical example is the large-scale demolition of UVs in Chinese cities in the 2000s (Ren, Reference Ren2018). The second approach is market-based rehabilitation of tenants, meaning the redevelopment of urban informal settlements and the relocation of tenants facilitated by the private sector, such as the resettlement of slum occupants in Mumbai (Doshi, Reference Doshi2013). Third, upgrading refers to the development of facilities and infrastructure in informal settlements and the provision of social services to the community (Perlman, Reference Perlman2010). Fourth, formalisation means the granting of legal recognition to informal housing within the regulatory framework to upgrade housing conditions, improve access to resources and enhance tenure security (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Lombard and Mitlin2020). Finally, non-enforcement refers to state toleration of informal dwellings due to the difficulty involved in prosecution and resettlement (Yau and Yip, Reference Yau and Yip2022). For instance, since the 1950s, governments in HK have adopted a toleration approach to the informal housing sector as it acted as a buffer against the city’s acute housing unaffordability (Tanasescu et al., Reference Tanasescu, Chui and Smart2010).

Hong Kong’s SDUs and Guangzhou’s UVs

In HK, one of the globe’s priciest housing markets, the government has maintained a highly commodified housing market under a “laissez-faire” rationale while providing subsidised rental and sale flats as a form of poverty alleviation since the colonial era (Yip, Reference Yip and Doling2014). Despite continuous efforts, the housing crisis has persisted and even escalated after the handover in 1997. Housing unaffordability has disproportionately undermined grassroots access to adequate housing (Chan, Reference Chan2023). Unmet housing demands are mitigated by the informal sector, such as SDUs, tiny compartments subdivided from larger domestic quarters, typically in aged buildings, which have been spreading over the past two decades. Statistics from the Census and Statistics Department (C&SD) show that the population living in SDUs reached 108,200 units and 215,700 inhabitants in 2021 (C&SD, 2023). In exchange for lower rent, tenants endure poor conditions. The median floor area and per capita area of the SDUs are approximately 11 and 6 m², respectively, much smaller than the HK average of 16 m² (C&SD, 2022). Conditions in SDUs are widely considered inadequate, lacking basic facilities such as bedrooms and kitchens, and suffering from poor ventilation, bedbug and rodent infestations, and sewage problems (Chan, Reference Chan2023; Leung and Yiu, Reference Leung and Yiu2022), deteriorating tenants’ well-being (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Lai, Hoi, Li, Chan and Sin2024). For years, the HK government has adopted a tolerant attitude and restraint from strict enforcement (Yau and Yip, Reference Yau and Yip2022). However, since the 2020s, after concerns raised by the Chinese government, the HK government has attempted to “tackle the SDU problem” by introducing tougher regulations.

The phenomenon of UVs, known as chengzhongcun, emerged in Chinese cities during urbanisation and market reforms since the late 1970s (Liu et al., Reference Liu, He, Wu and Webster2010). This study focuses on GZ, a major economic hub in the Pearl River Delta, because it was one of the first coastal cities to undergo market reform and contains a significant migrant population as well as a high concentration of UVs, making it comparable to HK. The city’s 272 UVs house 515 million residents, accounting for 28% of the city’s population (Guangzhou Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, 2019, 2024). These UVs are characterised by high-density, mid-rise multi-functional buildings that support residential, commercial, and production activities but lack adequate infrastructure and public services (Li et al., Reference Li, Lin, Li and Wu2014). Despite these shortcomings, UVs are attractive to low-income or short-term residents due to their prime location, affordable rent, and job opportunities. This scenario is particularly true for rural-to-urban migrants and landless farmers who cannot afford formal housing (Liu et al., Reference Liu, He, Wu and Webster2010). UVs are often seen as the “scars of urban cities” due to poor conditions and unregulated structures. However, they cannot be easily demolished because they are usually on collectively owned rural lands outside government jurisdiction. Under China’s dual land ownership system, urban land is state-owned, whereas rural land belongs to village collectives (Pan and Du, Reference Pan and Du2021). To address this problem, the GZ municipal government has adopted a demolition and rebuild approach to redevelop UVs, aiming to acquire land for urbanisation. Despite decades of redevelopment efforts, progress remains slow because of the complexity of land ownership and competing interests among stakeholders (Ren, Reference Ren2018).

The case of SDUs and UVs exhibits notable similarities, given their location in central urban areas, with dispersed ownerships, substandard built environments, unauthorised constructions, and a high concentration of low-income tenants. In both cases, interventions often involve costly resettlement and disputes regarding land or property ownerships. Nevertheless, the two cities also possess sociopolitical and economic uniqueness that render them suitable cases of a systematic comparative analysis. The evolution of policies and discourses in HK and GZ over the past decade demonstrates how urban informality can serve as a site of critical analysis in examining housing governance as complex political–economic and social processes (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Lombard and Mitlin2020). This article employs CPDA as a methodological approach to elucidate these dynamics.

Methods

CPDA of housing policy as methods

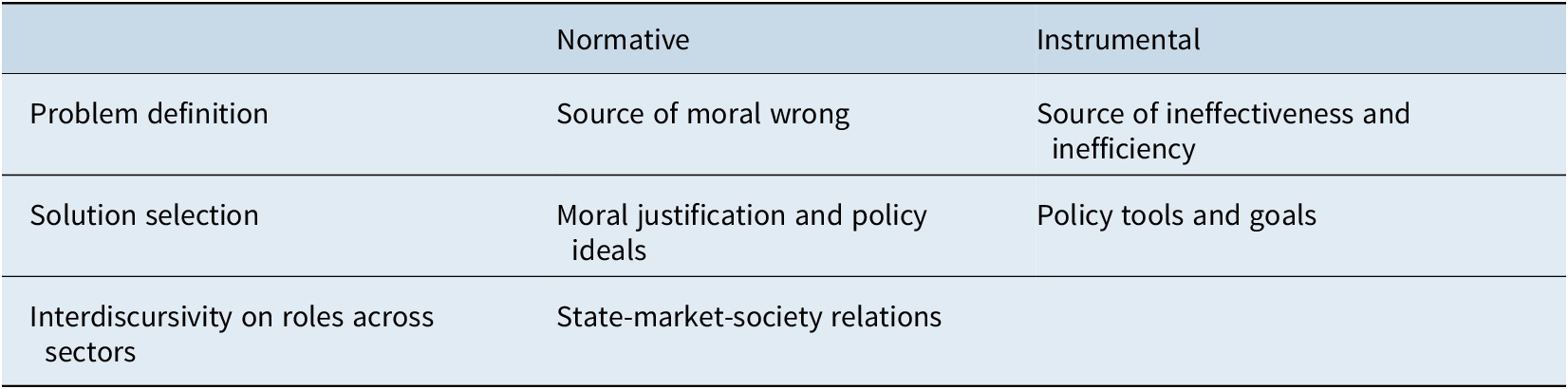

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) in housing policy research allows researchers to examine the ideational dynamics shaping the policy preferences of actors over time (Béland, Reference Béland2019). Housing discourses refer to the ideas and narratives on the field of housing (Kolocek, Reference Kolocek2017). Informed by discursive institutionalism (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt and van Gerven2023), housing discourses can be classified as normative and instrumental ideas promoting specific forms of problem definitions and solution selections. Marston (Reference Marston2002) suggests that the CDA of housing issues could historicise and periodise policy discourses by examining the changing meanings in formal policy documents and informal archives. Housing-related CDA also investigates the construction of the roles played by different sectors in shaping housing outcomes, including broader narratives of state-market-citizen relations (Munro, Reference Munro2018). Through CDA, researchers can delve into actors’ languages, assumptions, and practices, connected with a set of institutional logics orchestrating the distribution of housing resources and responsibilities.

In this regard, CPDA, a branch of CDA, could further the interrelationships among policy discourses, practices, and interventions (Montessori, Reference Montessori, Handford and Gee2023). CDPA is particularly useful in conducting the comparative analysis on housing policy because it demonstrates the socially constituted and constitutive characters of housing discourses . By applying methods of thematic and documentary analysis, such as close analysis of official documents, CPDA delivers text-oriented, multi-layered, and context-dependent accounts explaining the (re)presentations and communications of housing subjects (Marston, Reference Marston2002; Montessori, Reference Montessori, Handford and Gee2023), which advances the methodological and epistemological basis of CDA. Furthermore, housing-related CPDA highlights the inter-discursivity between state, market, and society to capture the ways dominant policy ideas shape the institutionalisation of selected housing solutions. Utilising the CPDA approach, this study constructs an analytical framework (see Table 1) to examine the housing discourses and policies on SDUs and UVs, guided by the following research questions:

-

1) What are the similarities and differences in the intervention on SDUs and UVs?

-

2) What are the discursive strategies deployed by the HK and GZ government to justify their policy on SDUs and UVs, respectively?

Table 1. Analytical framework to examine housing discourses and policies on SDU

Data collection and analysis

For SDU policy, the research team searched for documents through the HKSAR news archive news.gov.hk by using the keyword “Tong Fong” (SDU) from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2023. A total of 482 documents were sampled. Similarly, the team searched for major policies regarding UVs via the official website of The People’s Government of Guangzhou Municipality within the same period and gathered 550 pages of policy documents for systematic analysis.

Thematic analysis was used to identify common themes from official documents (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Two trained research assistants coded the documents using a codebook based on the CDPA framework, and the team had regular meetings to address updates and disagreements. The codes were organised into thematic categories reflecting the major policy measures implemented over different periods, illustrating evolving policy discourses. The team compared thematic categories and examined their relationships to understand the continuity and changes in SDU and UV policy discourses over time. Representative official texts and verbatim quotes were selected and translated to concretise the policy discourses and substantiate the analysis.

Results

We build the comparative analysis on three domains, including policy objectives, which compare the policy goals in the intervention of SDUs and UVs; intervention measures, which investigate the approaches governing informal housings and addressing the interests of multiple stakeholders; and the state-market-society relationship, which examines the roles played by different actors in the process of informal housing interventions.

Policy objectives

Hong Kong: Tackling social problem and improving livelihood

Under changing sociopolitical contexts, the HK government has orchestrated various discourses on SDU to define and justify policy goals. Between 2010 and 2012, the government portrayed SDU problems as a building safety hazard. This perspective prioritised the safety of tenants and the public by monitoring the built environment. The focus on housing habitability reduced the complex housing problems and urban redevelopment controversies to technocratic issues. After 2012, the government has increasingly attributed SDU households’ hardship to the structural problem of land shortage, assuring the government’s responsibility to alleviate the housing-induced poverty. Since 2020, SDU problems have been presented as the injustice and unfairness of the housing markets associated with landlord’s rental malpractices. Despite the government’s initial reluctance to directly regulate the rental market, they have started to recognise SDUs as an unacceptable housing tenure.

Between 2010 and 2012, several fatal incidents shifted the early official discourse on SDU to concentrate primarily on building safety associated with urban decay (Yau and Yip, Reference Yau and Yip2022):

…the building collapse incident not only highlights the issue of dilapidated buildings but also a very serious social problem. The most severely dilapidated old buildings are inhabited by the most vulnerable groups in HK…modified or subdivided flats, which were called SDUs, I am afraid [are] a social problem that we must face. (Secretary for Development, 2010)

The government subsequently introduced new legislations for building regulation and stricter inspection. The urgency and obligation to ensure building safety continued to serve as a normative justification to tighten control over illegal building works. After a fatal fire broke out in 2011, the Secretary for Development reaffirmed the SDU phenomenon as a problem of building management and property owners’ responsibility to adhere to safety standards.

Between 2013 and 2020, the government of Leung Chun Ying’s (Leung) administration has framed the SDU problem as an outcome of land shortage and a manifestation of poverty, which should be mitigated through increased land supply and poverty alleviation. In 2013, official documents addressing new categories including “poverty”, “social welfare,” and “poor conditions of SDUs” grew rapidly; the categories of “housing policy”, “land policy,” and “housing market” also proliferated. Officials emphasised that the SDU problem was rooted in the lack of usable land and housing that undermined housing rights and living conditions of low-income groups, who were forced to live in substandard SDUs. In his election manifesto, Leung promised to mitigate the hardship of low-income groups, including SDU tenants, by offering financial allowances (Leung, Reference Leung2012). This phenomenon substantiated the government’s normative discourse that highlighted its commitment to poverty alleviation. As the then Chief Secretary, Carrie Lam said, “…we will shortly devise the necessary scheme and also broaden the definition of ‘inadequately housed’ so that more residents living in the so-called subdivided flats will benefit from the subsidy to be dished out by the Community Care Fund (CCF)” (Lam, Reference Lam2013).

From 2020 onwards, the official discourse shifted to recognise the SDU rental market as “unfair” and “imperfect” (Secretariat for the Task Force, 2021) due to strong sociopolitical pressure. Amid the Anti-Extradition Bill (Anti-ELAB) protest in 2020, the government announced the setting up of the Task Force for the Study on Tenancy Control of SDUs (the Task Force) to pacify social discontent. The tenancy control aimed to provide “reasonable protection(s)” for SDU tenants, including a cap on the rate of rent increase, a four-year security of tenure and the prohibition of collecting excessive utility fees (Legislative Council, 2021). The tenancy control was presented as a moral and moderate measure to tackle the SDU problem: “Due to the imperfection of the SDU market, implementing rent control on SDUs does not violate the principle of the free market. If the SDU rental market has been ‘unjust’ and ‘unfair’ at the outset, the Government should intervene.” (Secretariat for the Task Force, 2021)

This regulation aimed to “provide SDU tenants with the right to security of tenancy in response to the eager request of SDU tenants, concern groups and the cross-party legislative councillors” (Secretary for Transport and Housing, 2021). Intriguingly, the government’s attitude towards SDU has shifted from toleration to eradication in 2021, after Xia Baolong, the director of the HK and Macau Affairs Office, said that HK should “bid farewell to SDUs.” Recognising the political implications of the state-delegated mission, Chief Executive John Lee (Lee) assumed the moral high ground and declared in his 2023 Policy Address that the government would put an end to the SDU problem (Lee, Reference Lee2023).

Guangzhou: Pro-growth urban development and modernisation

The policy goals of UV governance in GZ have been consistently focused on urban redevelopment for fostering economic growth and constructing an image of the modern city (Pan and Du, Reference Pan and Du2021; Ren, Reference Ren2018). The shortage of urban developable lands, resulting from the dual land ownership system, and the quest for economic advancement, are the fundamental drivers that motivate and structure the governance of UVs in many Chinese cities, including GZ (Li et al., Reference Li, Lin, Li and Wu2014). To accomplish the pro-growth objectives, the government adopted a demolition-rebuild approach that could maximise land acquisition and facilitate market-oriented urbanisation. Although this approach had rapidly transformed the city’s urban landscapes, it also raised controversies over environmental sustainability, cultural perseveration, and the livelihood of low-income tenants (Pan and Du, Reference Pan and Du2021; Zhang, Reference Zhang2011). Recently, the government has increasingly emphasised on preserving and enhancing existing communities and village cultures, along with improving access to public welfare and affordable rental housing, as reflected in changing official discourses.

The post-2009 UV governance primarily targeted at renewing the “three olds” (old factories, old neighbourhoods, and old villages), including UVs. In the official discourses, the “three olds,” “shanty areas,” and village cities were described as dwellings of “poor housing quality, numerous safety hazards, incomplete functionality, and insufficient facilities” (Guangdong Provincial People’s Government 2014). Such portrayal, often reinforced by the media, legitimised the demolition-oriented redevelopment targeting environmental upgrading and economic growth. In the 2009 Opinions regarding the “Three Olds,” the Guangzhou Municipal Government (2009) stated the purposes of eliminating them:

The redevelopment of ‘Three Olds’ is a crucial method for expanding construction space and securing land for development amid the growing tension between land supply and demand. It is a key component of promoting land conservation and efficient use. Additionally, it is essential for improving urban appearance and living environments, enhancing residents’ quality of life, and building a modern, liveable city.

The first part highlighted the urgency of redeveloping the “three olds,” which originated in the tension between economic development and land supply and motivated by the government’s strategic initiatives such as industrial restructuring and land efficiency improvement. This instrumental discourse of UV governance was complemented by the normative discourse of environmental improvement and enhancement of resident’s quality of life. The instrumental principles of “structural upgrading, classified guidance, comprehensive development, and economical and intensive use of resources” continued to be prioritised in the policy discourses during the 2010s (Guangzhou Municipal Government, 2012).

Nevertheless, in recent years, the government has diversified its policy goals by incorporating culture- and residents-oriented components, responding to the growing recognition of the socio-economic and cultural values of UVs and intense criticisms over the eviction of migrant populations due to massive demolition (Liu et al., Reference Liu, He, Wu and Webster2010; Pan and Du, Reference Pan and Du2021). In the 2019 Measures of Guangzhou Municipality on Urban Renewal, “benefit-sharing, fairness, and transparency” were included as the guiding principles. In 2021, the State Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (2021) affirmed a combined approach of “preserve, renovate, and demolish” that focused on preservation and enhancement and avoided large-scale demolitions of UVs to maintain the availability of affordable rental options. In the Guiding Opinions on Actively and Steadily Promoting the Transformation of Urban Villages in Super Large Cities 2023, the State Council further reinforced a normative discourse emphasizing that the governance of UVs should:

adhere to the principle of seeking progress while maintaining stability, proceeding actively and prudently. Priority should be given to transforming urban villages with pressing public needs, significant urban safety risks, and numerous social governance challenges. (Guangzhou Daily 2023)

The shift in policy goals was reflected in some recent redevelopment programmes that exhibited collaborative features between the government, private developers, urban planners, indigenous villagers, and residents in GZ (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Li, Tong, Que and Peng2023; Gu and Zhao, 2021). However, UV governance continues to operate based on government-led and market-operated principles rather than a bottom-up approach, conforming to government authority over land use and the neoliberal script of urban development (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Li, Tong, Que and Peng2023).

Intervention of informal housing

Hong Kong: From toleration to formalisation

Over the years, policy measures addressing SDU problems appeared to be reactive and inconsistent, largely contingent on changing sociopolitical circumstances and state-market dynamics. Intervention of SDUs has shifted from a technocratic approach upholding building safety in the early 2010s to an approach combining toleration and welfare measures responding to intensifying social discontent after 2013. Only in recent years, due to political pressure from mass protests and the Central government, did the HK government begin to tighten regulatory measures on SDUs by introducing successive controls over the informal sector.

SDU policies between 2010 and 2012 were characterised by building safety regulation triggered by several fatal incidents that occurred in SDUs. First, the government expanded the legislation of the minor work control system to regulate construction work required in flat subdivisions (Legislative Council, 2011). SDUs in industrial buildings were stringently targeted for eradication on the grounds of public safety (Buildings Department, 2012). Additionally, to enhance fire and building safety, the government provided financial assistance to low-income and elderly landlords to undertake building maintenance (Legislative Council, 2011). For SDU tenants, a mean-tested allowance was provided to assist with relocation due to enforcement actions. However, the government rejected stronger interventions in the SDU market, justifying this by emphasising the housing market’s practicality and the “societal function” of the SDU market as a buffer for housing unaffordability.

Moving towards 2013, SDU policy exhibited a combination of tolerance and welfare-based intervention, with a market-centric orientation. Under the administrations of Leung and Lam, land and housing developmental regimes were utilised to pacify the social discontent fuelled by intensified socio-economic inequalities, especially in housing (Forrest and Xian, Reference Forrest and Xian2018). The government attributed the spread of SDUs to land and housing shortages, proposing an increase in land supply through mega development projects and transient social housing as solutions, while rejecting long-term policy due to concerns over feasibility and effectiveness. For instance, despite persistent advocacy from civil society, the government rejected the suggestion of rent subsidies for years, claiming that it would increase rent pressure and benefit landlords through the shifted windfall (Secretary for Transport and Housing, 2016). Meanwhile, the growing public sympathy for SDU tenants pressurised the government to adopt successive social measures. The proposal for mean-tested transitional housing was incorporated in the 2017 Policy Address, which framed it as an innovative initiative that demonstrated the government’s “determination in tackling this priority livelihood issue,” (Lam, Reference Lam2017) suggesting that transitional housing could improve the livelihood of disadvantaged groups and rebuild social cohesion (Lam, Reference Lam2020). Additionally, other short-term measures, such as the living subsidy, were deployed to support low-income tenants. These non-recurrent allowances helped substantiate the government’s normative discourse, which affirmed its commitment to poverty alleviation.

Heightened political pressure after 2019 pressurised the HK government to implement heavy-handed policies, including tenancy control and a minimum SDU standard. The number of official documents addressing SDU policies grew eight times between 2019 and 2023, and those mentioning social welfare also increased rapidly. While the government’s stricter approach to SDUs was partly a response to sociopolitical crises – namely, the Anti-ELAB protest and the COVID-19 pandemic – it was also driven by pressure from the Chinese government. In 2022, Lee’s administration further strengthened the regulatory regime on SDUs by proposing a minimum living standard and to eradicate all substandard units, a notable shift from the previous toleration approach. Nevertheless, observing the conflicting interests and technical complications involved, the government reiterated that these regulatory measures would be implemented in “an orderly manner” (Lee, Reference Lee2023) and pragmatic sense (Secretary for Housing, 2023). Despite new regulatory approaches, the government continues to instrumentally prioritise the stability of existing housing regimes, aiming to avoid reducing rental unit supply in both formal and informal markets.

Guangzhou: From demolition and rebuild to gradual organic renewal

In China, UV intervention primarily followed a demolition-rebuild approach, through which villages are removed on a large scale and redeveloped into commodity housing and modern urban landscapes. Between the 1990s and the mid-2000s, research documented that many government-initiated urban renewal programmes had led to massive displacement (Liu et al., Reference Liu, He, Wu and Webster2010; Zhang, Reference Zhang2011). Since the 2000s, redevelopment projects began to evolve into a government-led approach in collaboration with stakeholders including property developers, planners, and villagers. This model enabled mutually beneficial interdependence among stakeholders: the government achieved urban upgrading at lower costs as developers bore most redevelopment expenses; developers received prime land for developing profitable commercial and residential buildings, and villagers and property owners were pacified with market-rate compensation or resettlement units (Pan and Du, Reference Pan and Du2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang and Webster2013). This model, however, excluded migrant tenants from the redevelopment process and led to their uncompensated displacement (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Geertman, Lin and van Oort2018; Zhang, Reference Zhang2011). Nevertheless, recently, some local authorities have moderated their official discourse and approach from total demolition to small-scale, gradual and micro-renewal, as illustrated in the GZ case.

In the late 2000s, most redevelopment programmes in the GZ adhered to the principle of “complete demolition and reconstruction” in comprehensive redevelopment projects. In the 2012 Supplementary Opinions, the GZ government reaffirmed its leading role in UV renewal, demanding that any redevelopment programmes should be approved and incorporated into the government’s annual implementation plan. Nevertheless, policy rationales and discourse started to change in the early 2010s. The State Council (2013) announced that redevelopment of shanty areas should not be limited to demolition and reconstruction but also include renovation. Besides, collaborative elements were further consolidated in the policy discourses. In 2015, the GZ Government proposed that comprehensive total demolition would only be applicable to areas that are difficult to improve, whereas micro-redevelopment, including renovation and partial redevelopment, should be adopted in “preserving historical and cultural heritage, protecting natural ecology, and promoting the harmonious development of old villages” (Guangzhou Municipal Government, 2015). This policy shift demonstrates an integration of instrumental and nominative discourse: while urban upgrading remains the paramount goal of UV governance, the values of cultures, traditions, and environmental preservation were incorporated into the policy discourse to legitimise the authority’s pro-growth rationales. Instrumentally, the government tacitly invited the participation of private developers as a market solution to cope with the rising cost of land requisition and redevelopment.

However, the state-market collaborative approach was criticised for its profit-oriented and neoliberal tendency, leading to redevelopment outcomes that exacerbate the predicament of migrant tenants (Lin et al., Reference Lin, De Meulder and Wang2011; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Geertman, Lin and van Oort2018). During the post-2020s, a modified approach was further observed in the official discourse in response to years of criticism. In 2021, the State Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development announced the notice on Preventing Large-scale Demolition and Construction in Urban-Renewal Projects, reiterating that “large-scale, concentrated demolition of existing buildings” should be avoided except for illegal structures and hazardous buildings, whereas “small-scale, gradual organic renewal, and micro-redevelopment” should be encouraged. The State Ministry of Natural Resources (2023) reaffirmed that urban renewal should “prioritise protection, minimise demolition, and maximise redevelopment,” signifying a normative turn in policy discourse addressing the growing concerns of urban sustainability and residents’ livelihood, while still reinforcing redevelopment as an indispensable path to urban modernisation.

The normative shift in recent policy discourse is also reflected in resettlement. Resettlement policy in the early 2010s was considered narrow in scope, as it primarily specified two main forms of arrangements: monetary compensation and physical resettlement. However, in the 2020s, resettlement arrangements appeared to be more comprehensive in terms of their objectives and approaches, which aim to improve neighbourhood conditions and relations. On multiple occasions, the Central and GZ governments reiterated that comprehensive redevelopment projects should protect residents’ livelihood (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, 2021) and the construction of resettlement housing and public service infrastructures should be prioritised (Guangzhou Municipal Government, 2023). Although the normative shift in the discourse on UV governance is observed with an explicit emphasis on residents’ well-being, the housing rights of migrant tenants remain largely unaddressed.

State-market-society relationship

Hong Kong: The changing state-led tripartite collaboration

Overall, the regulatory-welfare-mix model of informal housing intervention in HK was initiated by the government, operated in the market and negotiated by civil society. These actors’ interactions promoted the changing intervention of informal housing. Although the policymaking power is centralised within the administration, civil society played a key role in housing rights advocacy and service provision. Between 2014 and 2016, the government dismissed the proposal suggested by NGOs on implementing rent control and subsidies, citing a lack of extra land, and low cost-effectiveness as reasons (News.gov.hk, 2014, 2016). However, pressured by the growing public sympathy for SDU tenants and campaigning from civil society, the government adopted several measures to improve tenants’ living conditions, including temporary allowances and transitional housing. Nevertheless, the government never assumed full responsibility to supply transitional housing but retained a secondary role in facilitating small-scale community social housing initiatives managed by NGOs: “We hope to let the community forces, especially voluntary groups and organisations, use their creativity as much as possible. Our role is to help and facilitate the ideas put forward by community organisations.” (Secretary for Transport and Housing, 2018) The model of a “tripartite partnership of the community, business sector, and the government” (Lam, Reference Lam2019), in which the business sector provides land resources for NGOs to operate community housing, was restated on various official occasions as an effective means of improving the lives of SDU tenants. Through co-opting the community initiatives, including transitional housing and community living rooms, the government demonstrated its moral duty towards the SDU problem and placated social discontent without directly intervening in the private housing and rental market.

After the 2019 Anti-ELAB Protest, the government changed its stance towards tenancy regulation and the formalisation of the SDU market. On the one hand, amid sociopolitical instability and the pandemic, the government needed to regain legitimacy. On the other hand, the government’s changing approach to SDUs marked a “new stage,” characterised by measures to meet the Central government’s expectations. Despite the institutionalisation of the SDU sector, the extent to which landlord-tenant power asymmetries could be balanced remains questionable.

In short, the governance of informal housing in HK has been dominated by the government, facilitated by the market, and negotiated within civil society under changing sociopolitical contexts. The government has developed a regulatory regime consisting of various policy instruments, including strategic toleration, the co-optation of community initiatives, restrained market interventions, and formalisation, corresponding to specific sociopolitical circumstances.

Guangzhou: Government-led, market-operated collaborative approach

Similar to the HK government, local governments in China’s major cities possess a high degree of administrative and financial autonomy, monopolising power over land use and urban governance. Although local authorities have allowed a collaborative approach, they have never retreated from their role as the masterminds of urban redevelopment. As Ren (Reference Ren2018) aptly summed up, “(local governments) are the architects of pro-growth agendas, and they determine the scope and terms of participation for nonstate actors” (p. 81). The dominant role of local governments is consistently reiterated throughout policy discourses as shown in the GZ case. Local government units lead UV redevelopment by researching, drafting policies, estimating costs, planning resettlement, and overseeing implementation (Guangzhou Urban Renewal Bureau, 2020).

To accomplish the goal of urban modernisation and reduce costs, the municipal government invited the private sector to participate in the redevelopment of the “three olds,” including UVs. It also allowed village economic collectives to introduce private enterprises to participate in renewal projects. Despite these collaborative elements, policy discourse continues to reinstate the dominant role of the government by consolidating a “government-led, market-operated” approach as the guiding principle of the renewal of UVs. This approach differs from HK, where the government does not explicitly involve real estate developers in redeveloping SDUs in policy discourses.

Another major difference in the state-market-society relationship between GZ and HK is the role of civil society or social actors with vested interests. While NGOs and pressure groups play a pivotal role in shaping SDU interventions in HK, the powerful social actors in GZ are the indigenous villagers and property owners, who often possess extensive clan networks that can influence administrative and political organisations (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang and Webster2013). In policy discourse, village collectives are entitled to formulate redevelopment projects, including the scale of renewal, demolition, compensation, and resettlement, and suggest potential collaborative enterprises (Guangzhou Municipal Government, 2022). Villagers and owners often formed powerful interest groups to bargain for better compensation during redevelopment processes (Ren, Reference Ren2018). However, such negotiations excluded migrant tenants, who are often economically precarious and politically powerless. Without strong civil society and advocacy groups, migrant tenants coped with urban renewal by relocating to more remote or substandard areas (Zhang, Reference Zhang2011).

Discussion and conclusion

Based on the comparative case study, it is observed that the two regimes operate under the framework of “one country, two governances,” as they exhibit both similarities and differences. The most notable commonality is that the Central government holds the ultimate power in determining the direction of informal housing policy in both cities, demonstrated by the shift from toleration to tightened regulation in HK and the emergence of collaborative developmentalism in GZ. Informal housing policy in both cities has been coherently shaped by the hierarchical power dynamics between the Central and local governments, where the Central government sets policy agendas and the local governments implement them, signifying the state-led nature of policymaking in China.

The governance of informal housing in HK and GZ is both influenced by fiscal concerns, as land auctions and real estate development contribute significantly to government revenue. However, three key factors differentiate the trajectories of informal housing intervention in the two cities. First, the political structure and institutional power of the two governments determine the policy orientation and the selection of policy levers in governing informal housing. HK’s administration-led polity guaranteed its authority to introduce new policy measures, while the electoral politics opened few policy windows for social actors to advocate for policy changes. Therefore, the HK government’s policymaking power was partly constrained by various stakeholders under the executive-led electoral political system. By contrast, the GZ government possesses a high degree of power in the municipal level, which enabled them to introduce and implement policy measures that align with the Central government’s policy framework. Furthermore, the GZ government monopolises the legal power to initiate and approve urban development projects, rendering urban renewal as a top-down process despite the involvement of multiple parties.

Second, informal housing intervention is subject to the political economy of the formal housing market. In HK, a real estate-led capitalist economy prioritises developers’ interests and a highly commodified housing market (Forrest and Xian, Reference Forrest and Xian2018), in which owners’ property rights are considered more central than tenants’ protection. Under such political economic structure, the government adopted a tolerant approach because the informal sector helps buffer housing unaffordability. This approach remained until the SDU problem escalated into a social crisis that generated sociopolitical discontent against the administration, necessitating stricter regulations as mandated by the Chinese government (Smart and Fung, Reference Smart and Fung2023). By contrast, under the state-led market economy in China, the housing market operates under state agenda. The GZ government continually played a dominant role in determining land uses, urban redevelopment, and the housing system. Despite increased collaboration with private developers and urban planning professionals over the years, the power of governing informal housing and land uses was still centralised within local governments (Ren, Reference Ren2018).

Finally, the role of civil society and pressured groups also shaped the divergent trajectories of informal housing interventions in the two cities. With the history of housing and urban movements, the civil society in HK had persistently advocated for policies that protect the rights of SDU households through community organising and policy initiatives. The lack of institutionalised decision-making power did not dismiss the role of civil society and NGOs. Conversely, in GZ, village collectives replaced the role of civil society in defending the collective interests of local villagers and owners in the process of redevelopment. However, these village collectives only represented the interests of local villagers; the voices of landless tenants, especially migrants, were marginalised and their needs were unaddressed.

This article offers three contributions to housing policy literature. First, this comparative study provides a systematic comparison on policy discourses and levers to enrich policy analysis concerning the informal housing sector, addressing a gap in previous comparative housing studies, which have predominantly focused on the formal housing sector and social housing (with the notable exceptions of Grashoff, Reference Grashoff2020, and Ren, Reference Ren2018). By conducting CDPA, this comparative study maps the normative goals and policy instruments of informal housing policies in urban contexts in relation to the role of state, market, and society (Lund, Reference Lund2017). It addresses the question of informal housing and urban development in comparative perspectives (Forrest, Reference Forrest and Kennett2013), drawing broader lessons to understand contextualised forces of local housing systems (Stephens and Hick, Reference Stephens, Hick and Jacobs2024).

Second, this article enriches comparative housing policy studies by documenting the within-country variations of informal housing governance. While global forces, such as financialisation and neoliberalism, could generate common pressures on housing policy development, the interactions between governments’ housing intervention and the broader socio-economic contexts are embedded and structured within particular housing systems (Lund, Reference Lund2017) even in the same political entity, which complicates the convergence thesis and brings the latter into focus. Despite the similarities of central–local governmental structure and state dominance in the housing sector, the existence of different housing policy pathways between the two cities signals the path-dependent housing institutions and norms (Forrest, Reference Forrest and Kennett2013; Stephens and Hick, Reference Stephens, Hick and Jacobs2024). Similar housing categories could be associated with contrasting housing meanings, opportunities, and inequalities within different sociopolitical contexts.

Finally, the study provides insights into the governance of informal housing for policy actors within and beyond China by identifying two distinctive interventionist models: HK’s regulatory-welfare-mix approach and GZ’s state-led developmentalist model. The “welfare provision – market regulation” framework (Levi-Faur, 2014; Powell, Reference Powell2019) highlights the variety of policy instruments on informal housing and the government’s complementary implementation of welfare provisions and (re-)regulations to balance housing demands, tenant protection, and market interests. In contrast, the state-led developmentalism in GZ demonstrates how the government tacitly involves stakeholders in policymaking through selective collaborations to enhance legitimacy and pacify local demands. The comparative study provides empirical references for policymakers to enhance their variety of policy instruments in informal housing governance and for policy actors, including civil society and residents, to strategise their advocacy efforts in response to the political opportunities arising from unique political–economic configurations.

Data availability statement

The data of this study are available on request from the authors.

Notes on contributors

The first author is responsible for reviewing literature, conceptualisation, methodology, data collection and analysis. The second author is responsible for reviewing literature, conceptualisation, methodology, and data analysis. Both authors prepared the original draft of the manuscript. The third author is responsible for data collection, coding analysis, and literature review.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Direct Grant from Lingnan University (DR21C2); RGC Postdoctoral fellowship award (LU PDFS2021-3H01), and Early Career Scheme (ECS/LU23607522) from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Sub-Committee of Lingnan University.