1. Introduction

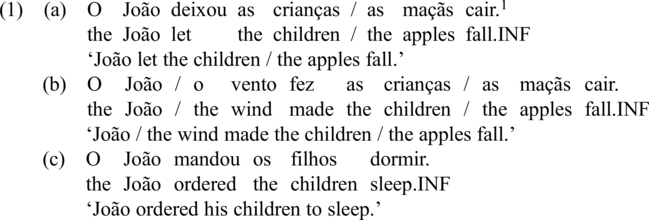

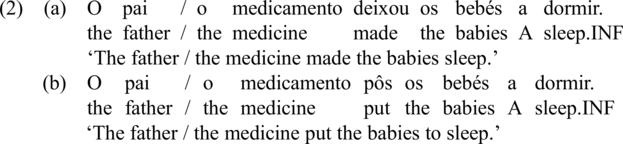

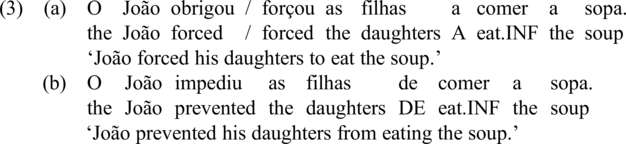

This paper explores the similarity of three classes of verbs in European Portuguese (EP), which have in common the fact that they share a superficially identical structure and a causative interpretation. These classes are represented by the well-known (syntactic) causatives deixar ‘let’, fazer ‘make’, and mandar ‘order / make’, which we will call Type A causatives, see (1); deixar a ‘make’ and pôr a ‘put to’ / ‘make’, which we will call Type B causatives, see (2); and a small subset of the class of object control verbs including obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’, see (3).

In very general terms, these verbs are typically preceded by a determiner phrase (DP) (in this case, DP1) and followed by another DP (DP2), which is itself followed by an infinitive, in some cases preceded by a preposition (or a preposition-like element) – the preposition is absent in Type A causatives, being present in the case of Type B causatives and object control structures. Considering semantics, these verbs can be taken to express a causative meaning – as for impedir ‘prevent’, it can also be taken to express a causative meaning if ‘causing’ includes both ‘helping’ and ‘hindering’ (Talmy Reference Talmy1988). More importantly, and as a related property, except for the causative mandar ‘order’, which will be our focus in Section 4.3, these verbs share the possibility of an implicative reading – at least a reading as a one-way implicative, in the sense of Karttunen (Reference Karttunen, Agirre, Bos, Diab, Manandhar, Marton and Yuret2012). This means that the verb entails the truth of its complement under one polarity – in general, the implicative causatives we have mentioned entail the truth of the complement under positive polarity, with the exception of impedir ‘prevent’, a negative implicative which, when also under positive polarity, entails the falsity of its complement. We develop the issue in Section 2.

The implicative interpretation is particularly relevant here, since it was associated, in the case of control structures, to a specific syntactic derivation. Landau (Reference Landau2015) argues that some object control verbs, which are not attitude verbs and are associated to an implicative interpretation, take a small clause as an internal argument and display a particular type of control: predicative control. The implicative entailment in the case of predicative control would be a consequence of the fact that in this case control would correspond to direct predication (this is more clearly stated in Landau Reference Landau2021). This kind of analysis of implicative object control verbs assumes that they are not truly ditransitive, what would place them closer to syntactic causatives.Footnote 2 Interestingly, Landau (Reference Landau2015) also argues that predicative control is compatible with a [-human] PRO – and the possibility of a [-human] or [-animate] DP2 in the structures in (1) to (3) will be relevant in the present study.

In this paper, we intend to discuss the nature of the syntactic structure projected by implicative object control verbs, further exploring similarities and differences between these verbs and syntactic causatives. We will show that the distribution and the interpretation of inflected infinitives in EP play a central role in the discussion, signalling different syntactic structures.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents a general description of the syntactic and semantic properties of three classes of verbs that share a causative meaning, highlighting relevant similarities; Section 3 further explores the comparison between the three classes of verbs, (i) showing that implicative object control verbs contrast with non-implicative object control verbs in their syntactic proximity with syntactic causatives and (ii) suggesting a duality of behaviour in the case of implicative object control verbs that correlates with the possibility of two different argument structures; finally, Section 4 defines the syntactic ambiguity of structures with implicative object control verbs, explains this syntactic ambiguity, and establishes a difference between these structures and the understudied Type B causatives – the behaviour of the inflected infinitive is a central piece of the argumentation. Section 5 concludes the discussion.

2. Syntactic causatives and object control verbs: Defining the structures under discussion

Causative sentences express a situation in which a relation between cause and effect may be identified. Although the expression of causation is typically associated to verb forms, different devices can be used to obtain that meaning, which gives rise to the following classical types of causatives: (i) morphological causatives, if causation is expressed by a bound morpheme – a causative affix – that combines with a verb root (e.g. Baker’s Reference Baker1988 synthetic languages); (ii) lexical causatives, if causation is conveyed by a verb lacking any causative morpheme but expressing itself the CAUSE meaning – typically change-of-state predicates, such as derreter ‘melt’ (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath, Comrie and Polinsky1993, Levin & Rappaport Hovav Reference Levin and Hovav1995), some of which undergo verb alternations; and (iii) syntactic causatives, characterized by the occurrence of a causative verb – thus, the causative marker is a free form – which introduces a second event also including a verb form. In EP, as in the other Romance languages and in English, only lexical and syntactic causatives are available.

In the present work, we will set aside morphological and lexical causatives and focus on three types of verbs in EP that exhibit some syntactic similarities and express some kind of causation: (i) Type A causatives deixar ‘let’, fazer ‘make, and mandar ‘order / make’, see (1); (ii) Type B causatives deixar a ‘put to’ / ‘make’ and pôr a ‘put to’ / ‘make’, see (2); and (iii) a subset of object control verbs, namely, those that display an implicative reading such as obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’, see (3). Type A causatives correspond to typical syntactic causatives and have been widely discussed (see seminal work by Kayne Reference Kayne1975, Burzio Reference Burzio1986, Guasti Reference Guasti1993; for EP, see Raposo Reference Raposo1981; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1999, Reference Gonçalves2002). On the contrary, reference to what we call here Type B causatives is scarce in the literature, with pôr a ‘put to’ / ‘make’ sometimes analysed as an object control verb (see Raposo Reference Raposo, Jaeggli and Safir1989: 302n20, for a brief reference to these verbs, and Agostinho Reference Agostinho2014, Agostinho, Santos & Duarte Reference Agostinho, Santos and Duarte2018 for the analysis of pôr a as part of the group of object control verbs) or being more recently associated to causatives with a change of location meaning, a ‘locative causative’ (Soares & Wood Reference Soares and Wood2021, Reference Soares and Wood2022).

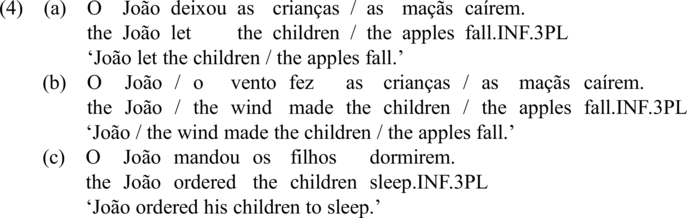

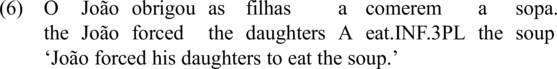

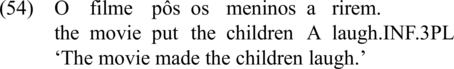

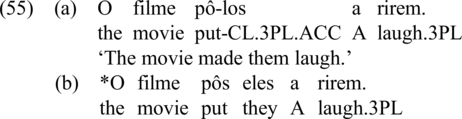

The three classes of verbs occur as V in the string [DP1 V DP2 Vinf], Vinf being an infinitival form of a verbal predicate selecting for its own arguments, and DP2 corresponding to what has been called causee in the context of syntactic causatives (4) and controller in the case of object control verbs (6) – therefore, in this paper, we will use the label DP2 to avoid choosing between the term controller or causee before we have determined the underlying structure we are dealing with (object control or other). The infinitival domain is introduced by a preposition-like element in the case of Type B and object control verbs (5, 6), and a third plural inflected infinitive matching DP2 in person and number features is allowed across the three classes of verbs under discussion:

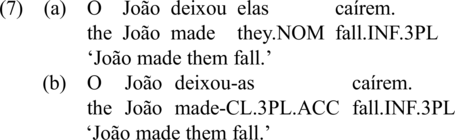

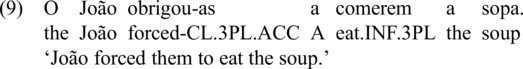

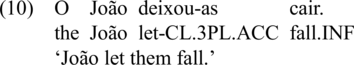

In what concerns the Case of DP2 in the context of inflected infinitives, a contrast is observed between Type A causatives and the two other verb classes under discussion: Whereas DP2 generally exhibits nominative under Type A causatives (7a), it exhibits accusative under Type B causatives and object control verbs (8, 9). However, the possibility of an accusative DP2 co-occurring with the inflected infinitive under Type A causatives (7b) has been equally noticed, and it is reported to be widely accepted, even if not described in grammars considering the standard variety (see Hornstein, Martins & Nunes Reference Hornstein, Martins and Nunes2008; Martins Reference Martins, Santos and Gonçalves2018; Barbosa, Flores & Pereira Reference Barbosa, Flores, Pereira, Guijarro-Fuentes and Cuza2018; Cardoso Reference Cardoso2021).

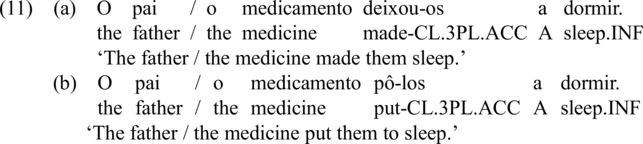

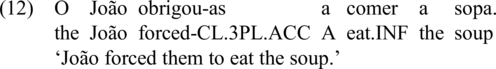

In the context of uninflected infinitive, DP2 exhibits accusative Case and cliticizes into V, the matrix verb, across the three classes of verbs:

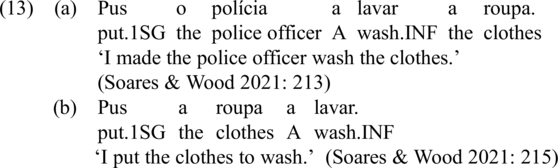

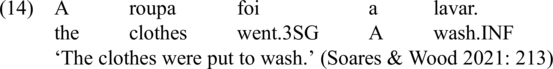

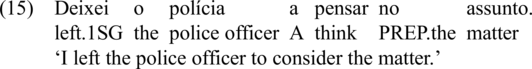

Sentences including Type A and Type B causatives express a cause-effect relation, as expected according to the classical definition of causation. However, it is important to establish a distinction between the status of pôr a ‘put to’ in the structures we are considering here (and which we take to be ‘ordinary causatives’) and what Soares & Wood (Reference Soares and Wood2021, Reference Soares and Wood2022) called ‘locative causatives’, that is, causatives that entail the change of location of the theme. As shown in (13), pôr a ‘put to’ can indeed maintain a locative meaning, more obvious in (13b), with what Soares & Wood call embedded passive Voice (a case in which the embedded theme occurs as causee), along with ir ‘go’ (14), which they classify as an intransitive locative causative – examples (13) and (14) are taken from Soares & Wood (Reference Soares and Wood2021). As shown in (15), deixar a (now with a meaning closer to ‘leave’, therefore with locative meaning) can also have the same interpretation of a locative causative, even though this was unnoticed by Soares & Wood (whether other verbs also belong to the same class is open to future discussion).

If we now consider again (11), or (5), we can see that the change of location meaning is not necessarily maintained in these cases – and in (11a) or (5a) deixar a corresponds to ‘put to’ / ‘make’.

In addition, Soares & Wood (Reference Soares and Wood2022) argue that locative causatives do not accept unaccusative embedded predicates, contrary to what happens with ordinary causatives. As we can see in (16), unaccusative predicates are perfectly acceptable under pôr a and deixar a in sentences in which a change of location meaning is not maintained:

Finally, a difference that was not noticed by Soares & Wood (Reference Soares and Wood2022) concerns the thematic role of the external argument of the causative verb: Whereas in the locative causative examples presented by Soares & Wood pôr a always takes a [+ human] external argument, therefore an argument filling the requirements of agenthood, the type of causative structures we are interested in (i.e. ordinary causatives) occur with a matrix external argument with a Causer thematic role: As seen in (16) as well as in (11) or (5), pôr a or deixar a accept a [- animate] subject, a case in which indeed the locative meaning cannot be maintained. Therefore, we believe to have established that we are not dealing in this paper with locative causatives but with ordinary causatives. Type B causatives, as defined here, are ordinary causatives, which do not necessarily preserve any form of locative meaning and, to this extent, seem to be more semantically bleached than locative causatives.

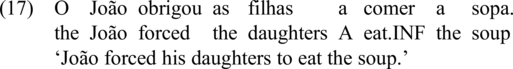

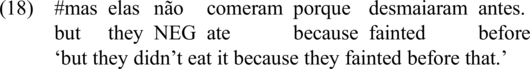

We should now consider object control verbs and their possible causative interpretation. A cause-effect relation is not necessarily established in the context of all object control verbs: It is expressed in the context of obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, impedir ‘prevent’, convencer ‘convince’, or persuadir ‘persuade’ but not in the context of e.g. acusar ‘accuse’. However, the subset of object control verbs we are analysing along with Type A and Type B causatives has a causative interpretation and, in addition, these verbs are one-way implicatives in the sense of Karttunen (Reference Karttunen, Agirre, Bos, Diab, Manandhar, Marton and Yuret2012) – see Landau (Reference Landau2015), who explores this class of verbs, and Santos (Reference Santos2023), who discusses the relevance of the class in EP. Being implicatives, ‘[a]n asserted main sentence with one of these verbs as predicate commits the speaker to an implied proposition which consists of the complement sentence’(Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971: 340); being one-way implicatives, these verbs entail the truth or the falsity of the infinitival complement only under one polarity (Karttunen Reference Karttunen, Agirre, Bos, Diab, Manandhar, Marton and Yuret2012: 124). The object control verbs obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’ exhibit these properties. Consider (17):

In EP, the implicative verb obrigar ‘force’ entails the truth of the embedded sentence under positive polarity: The fact that João forced his daughters to eat the soup entails that they ate the soup. This is why the continuation of (17) cannot be the one in (18) – see Santos (Reference Santos2023) and the examples therein.

In this respect, the implicative verb obrigar ‘force’ contrasts with object control verbs that have a causative meaning but are not implicative, such as convencer ‘convince’ or persuadir ‘persuade’, as Santos (Reference Santos2023) notes.

In this context, the control verb does not entail the embedded proposition: In fact, ‘as a result of Rui’s action, Ana at some point made the decision of eating the bean stew, but this does not entail that Ana did eat the bean stew’ (Santos Reference Santos2023: 22).

According to Landau (Reference Landau2021), the implicative and the non-implicative interpretation are directly related to syntax, the former being the result of a predicative structure and of predicative control. Predicative control contrasts with cases of logophoric control, in line with the duality of control mechanisms proposed in Landau (Reference Landau2015). Landau claims that in predicative control (as in the case of implicative control verbs such as obrigar ‘force’), the verb selects for a small clause, projected by a predicative head, the controller being the subject of this projection and the infinitival clause occupying the predicate position (the complement of the predicative head); in this case, the verb seems to combine with a single internal argument and we would say that it is, to this extent, closer to a syntactic causative. As for logophoric control, as under non-implicative verbs such as convencer ‘convince’, control does not result from predication. In Landau’s proposal, the difference in the syntactic structure triggers the difference in interpretation, to the extent that the implicative meaning results from predication. A relevant question is whether the close correspondence between semantics and syntax, which is suggested by Landau, obtains with the set of EP verbs we are analysing.

Given the general similarities between object control verbs and syntactic causatives, which may justify the different classifications in previous literature of what we call here Type B causatives, it is important to proceed to a more fine-grained comparison. The next subsection develops the issue and considers evidence allowing to identify control verbs.

3. Syntactic causatives and implicative object control verbs: Similarities and differences

In the present subsection, we explore the behaviour of Type A and Type B causatives as well as object control verbs, aiming at establishing the singularity of the subclass of implicative object control verbs. When doing this, we especially focus on aspects of their behaviour that point to differences in the number of internal arguments (one or two internal arguments) and which define the hallmarks of control structures.

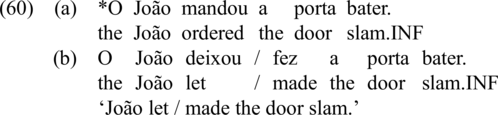

One first piece of the argumentation is the possibility of an inanimate DP2. As we can see in (20), the Type A causatives deixar ‘let’ and fazer ‘make’ (20a), and Type B causatives (20b), allow an inanimate DP in this position, as well as an animate DP, as already illustrated in (4) and (5) above.

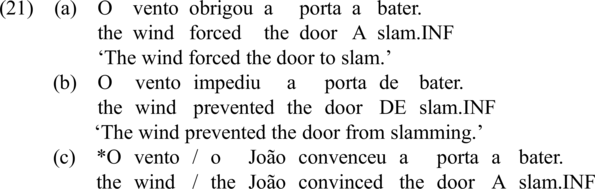

Interestingly, in the case of object control verbs, different behaviours are observed in the case of implicative (21a, b) and non-implicative verbs (21c): Whereas implicative object control verbs, here represented by obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’, pattern with syntactic causatives, allowing an inanimate DP2 (as well as an animate DP2), non-implicative object control verbs, represented by convencer ‘convince’, do not allow an inanimate DP2, i.e. an inanimate controller, independently of the animacy of the external argument of the verb, as shown in (21c).

At the very least, these facts allow us to conclude that implicative object control verbs do not semantically restrict the DP2, in contrast with non-implicative object control verbs. Landau (Reference Landau2015) has already noticed that predicative control (the type of control he associates with implicative control verbs) is compatible with a [-human] PRO, an issue we will come back to.

The set of examples in (21) also suggests the relevance of exploring the properties of DP1, the matrix external argument: Whereas implicative object control verbs (obrigar ‘force’, impedir ‘prevent’) allow a [-animate] external argument, non-implicative object control verbs do not allow the same type of subject; see the grammaticality of (21a, b) vs. (21c) and (22).Footnote 3

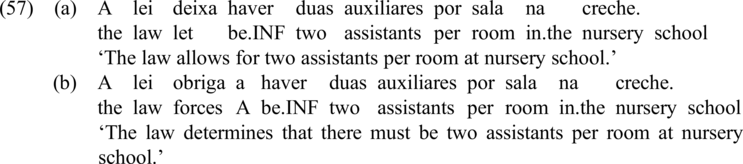

Another important contrast concerns the availability of expletives in the embedded subject position. In principle, we take the controller to be an argument of the control verb, from which it gets a theta role. We, therefore, do not expect to find expletives as controllers and we do not expect a controlled subject to be an expletive. It is therefore interesting to note that, along with Type A causatives (23a), but not with Type B causatives (23b), obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ can effectively take an infinitival complement with an expletive subject, in the context of an embedded weather verb (23c, d). Implicative object control verbs also contrast with the non-implicative convencer ‘convince’ (23e), independently of the animacy of the matrix subject. In (23c, d), obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ seem to select a single internal argument, in this case a clause with an expletive subject. The meaning of obrigar or impedir in this type of context, possible with a [-animate] subject, seems to be somehow bleached.

This observation leads to two further observations concerning the behaviour of obrigar ‘force’ and verbs of the same type, in contrast to object control verbs such as convencer ‘convince’, one regarding the argument structure of the verbs and a related observation concerning their compatibility with complements containing an expletive subject in an existential structure.

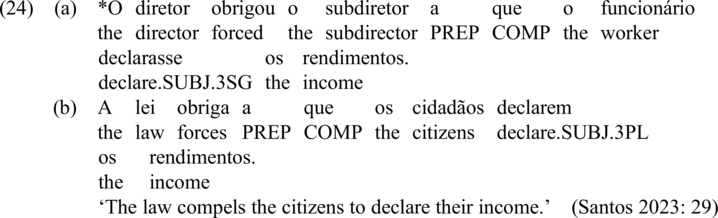

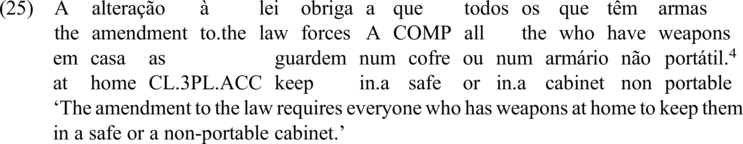

There has been some discussion on the possibility of omitting a controller with an object control verb. Landau (Reference Landau2015) argues that only predicative control (which he associates with implicative control verbs) is incompatible with an implicit controller – the possibility of an implicit controller with non-implicative object control verbs would be subject to variation defined by languages and verbs. However, the discussion should not only focus on the distinction between implicative and non-implicative interpretations; in fact, the sentences in (23c, d) also allow the observation that implicative object control verbs have a transitive counterpart, i.e. the verb takes a single internal argument, and in these cases, we would not be dealing with a case of implicit controller. This transitive structure is the structure compatible with a finite complement clause: As shown by Santos (Reference Santos2023), a verb such as obrigar ‘force’ cannot occur as ditransitive with a non-controlled, namely finite, complement. In (24) we reproduce Santos’ examples and in (25) we present a similar example, taken from the online press.

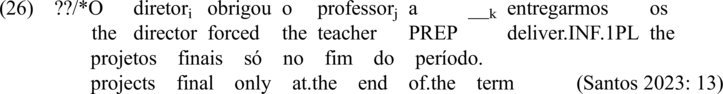

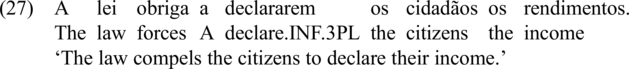

Moreover, Santos (Reference Santos2023) extensively argues that an inflected infinitive with a non-controlled subject is impossible under an implicative object control verb, such as obrigar ‘force’, when the DP2 position, i.e. the position of an object controller, is filled (see 26). As shown by the indices in (26), the inflected infinitive cannot take as subject a non-controlled pro, which gets its interpretation from discourse. Apparently, a non-controlled inflected infinitive is possible under the transitive counterpart of the verb, i.e. when the verb takes a single internal argument, in this case a non-finite clause, as in (27) – even if only possible with subject-verb inversion.

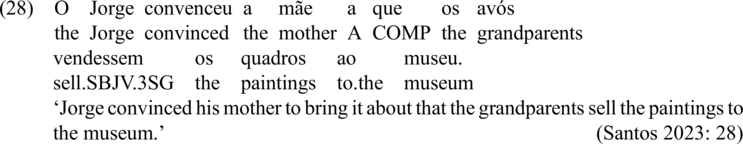

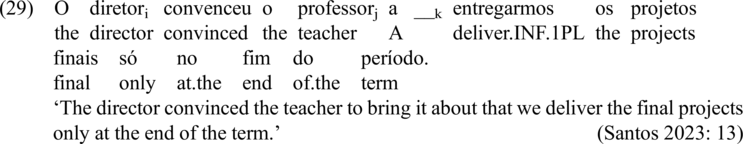

This contrasts with the behaviour of the non-implicative object control verb convencer ‘convince’, which allows the occurrence of a finite complement in a ditransitive structure (28), as well as of a non-controlled infinitive in the same structure (29) (as shown by Barbosa Reference Barbosa, Mucha, Hartmann and Trawinski2021, and also by Santos Reference Santos2023):

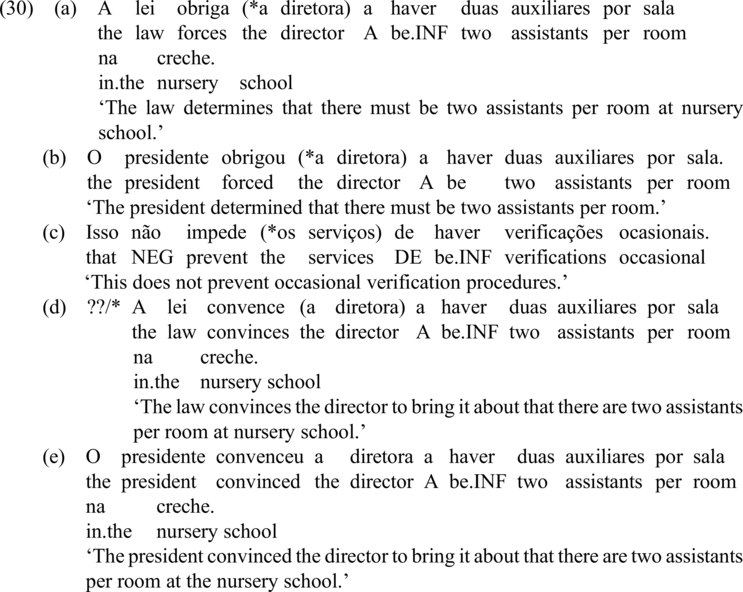

Let us now turn to the possibility of expletives under these verbs. In what follows, we explore structures with an embedded existential verb. As shown in (30a–c), an embedded expletive is acceptable with the transitives obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ but not when the verb occurs in sentences compatible with an analysis of the verb as ditransitive, i.e. in cases in which there is a DP2; in contrast, as shown in (30d, e), an embedded expletive is compatible with an explicit direct object in the case of convencer ‘convince’. As a side note, we see that the contrast between (30a) and (30d, e) is also due to the fact that the transitive counterpart of obrigar ‘force’ is compatible with an inanimate DP1 – the law, in (30a) – but convencer ‘convince’ is not (30d).

The data presented until now suggest that implicative verbs such as obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ may behave as transitive (i.e. they may select a single internal argument) – therefore, they are closer to syntactic causatives. As for convencer ‘convince’ and similar non-implicative verbs, they occur with two internal arguments, one of the arguments corresponding to an embedded clause whose subject is not necessarily controlled. This explains the case of the embedded finite clause in (28) or the case of the embedded infinitive with an expletive subject (30e).Footnote 5

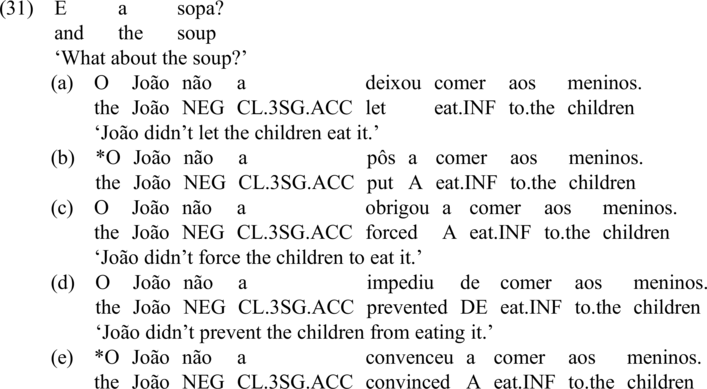

An important piece of evidence supporting the transitive behaviour of implicative verbs generally included in the class of object control verbs comes from the fact that they can occur in faire-Inf constructions. Kayne (Reference Kayne1975) has shown that French causatives, namely faire ‘make’, can occur in constructions in which the causative and the embedded verb (the latter in the infinitive) are adjacent, and in which the causee may occur as a dative (if the embedded verb is transitive): the faire-Inf construction. Raposo (Reference Raposo1981) and Gonçalves (Reference Gonçalves1999) have shown the availability of faire-Inf in EP under what we call here Type A causatives (see 31a) – clitic climbing is the result of complex predicate formation. As we now show, faire-Inf is also available under implicatives, such as obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ (31c, d), but not under Type B causatives (31b) and non-implicative object control verbs, such as convencer ‘convince’ (31e). We extend the term faire-Inf to contexts of object control verbs in the sense that the argument structure of the embedded verb is somehow reanalysed. Our examples only include embedded transitive contexts, since the occurrence of the dative (signalled by the dative marker a preceding the DP os meninos ‘the children’) makes faire-Inf more visible.

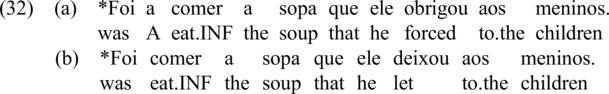

We can show that what we see under Type A causatives and under obrigar ‘force’ is truly a case of faire-Inf, by showing that the dative-marked DP2 in (31) (aos meninos ‘to the children’) is not an argument of the matrix verb: As we can see in (32), this DP cannot be left stranded when the embedded predicate is clefted; in contrast, when we have a matrix ditransitive such as permitir ‘allow’, as in (33), it is possible to cleft the embedded infinitival clause leaving the dative stranded.

The behaviour of the implicatives obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’, which was described until this point, suggests the proximity between these verbs and syntactic causatives, namely Type A causatives. Some of these data suggest that the implicative object control verbs behave, at least in certain structures, as transitives, i.e. they select a single internal argument. A transitive analysis of these verbs is to a certain extent compatible with Landau’s (Reference Landau2015) analysis of implicative object control verbs as verbs that take as complement a projection of a predicative head, or a Relator (Rel) (in the sense of Den Dikken Reference Den Dikken2006), with the object controller and the infinitive occupying the subject and the predicate positions of a small clause, respectively.

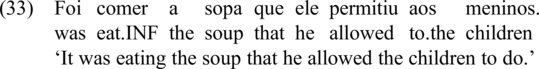

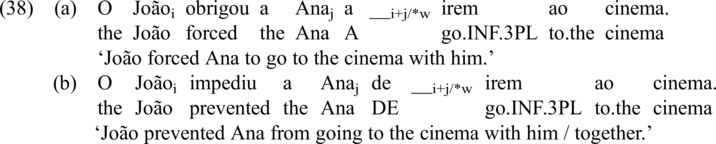

However, the more detailed observation of inflected infinitives under these verbs reveals an important difference between syntactic causatives and object control verbs: The difference concerns the possibility of occurring with an embedded inflected infinitive mismatching DP2 in number features. As shown in (34), this mismatching inflected infinitive is not possible under Type A or Type B causatives (34a, b) but it is possible under implicative (34c, d) as well as under non-implicative object control verbs (34e).

The difference between implicative and non-implicative object control verbs in this case concerns the interpretation of the embedded subject. Under implicative object control verbs, and as shown by the indices, the non-controlled reading is not available, only a split control reading is obtained – in the case of split control, the reference of the controlled subject ‘is exhausted by the matrix arguments – but it is split between them’ (Landau Reference Landau2013: 172). This reading is made more salient by the occurrence of juntos ‘together’ in the sentence, even though the reading does not depend on it. Split control is an instance of control, and the inflected infinitive under these verbs is therefore obligatorily controlled (Santos Reference Santos2023). Under non-implicative object control verbs, the inflected infinitive is not controlled (Barbosa Reference Barbosa, Mucha, Hartmann and Trawinski2021, Santos Reference Santos2023) – as we can see in (34e), the interpretation of the embedded subject can be free and we can interpret the sentence as meaning that João convinced Ana to bring it about that someone else will go to the cinema, an interpretation that is more easily available with a richer discourse context from which the reference of the embedded subject can be recovered.

Since Landau (Reference Landau2015, Reference Landau2021) associates a predicative syntactic structure to the implicative reading, it is important to note that the mismatching inflected infinitive in (34c, d) does not block this implicative interpretation (see 35), even though a mismatching inflected infinitive (and a split control reading) would not be expected in a predicative analysis of control, as we will discuss in the next subsection.

As an outcome of the facts presented in this subsection, we have a complex scenario concerning the behaviour of implicative object control verbs: Even though they exhibit properties that place them closer to syntactic causatives than to non-implicative object control verbs (namely, by allowing a [-animate] DP2 and embedded expletives, by occurring in transitive structures and by allowing faire-Inf), they retain the possibility of licensing split readings of inflected infinitives, what we will take to be a central property in the discussion. In the next subsection, we develop the discussion of these properties.

4. Towards an analysis: Syntactic causatives and the syntactic ambiguity of implicative object control verbs

In this subsection, we argue for the syntactic ambiguity of implicative object control verbs. We propose that the verbs obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’ have ditransitive and transitive counterparts and that most structures in which they occur are ambiguous. We also argue that a mismatching inflected infinitive with a split control reading (i.e. a plural embedded inflected infinitive in a structure with a singular object controller) is the relevant piece of evidence allowing to disambiguate between the two structures. Moreover, we argue that Type B causatives select a single internal argument, a small clause, and that we observe control internally to the complement.

In general, by considering the syntactic ambiguity of implicative control verbs and observing their stable implicative interpretation, we argue for the independence between the implicative reading and the syntactic structure at stake. A final note on the syntactic causative mandar ‘order’, which illustrates a diachronic shift from a ditransitive structure to a transitive causative one, will allow us to further argue for the independence of the syntactic and semantic domains in the area of causatives.

4.1. Explaining the syntactic ambiguity of implicative object control verbs

Perlmutter (Reference Perlmutter, Jacobs and Rosenbaum1970), in a seminal work on the syntax of begin, claims that there are two verbs begin, one selecting a single argument and another selecting two arguments and behaving as what we would treat as a control verb (we are abstracting away the specific syntactic analysis suggested in Perlmutter’s paper). Only the control verb would impose an animacy restriction to the subject that it occurs within surface structure. In more recent work on the acquisition of control and raising predicates, Becker (Reference Becker2014) argues for the relevance of animacy as a cue in the acquisition of control vs. raising structures, with a [-animate] subject signalling a raising predicate. The discussion that we will take in this subsection is in line with these two insights.

In a different framework, Jackendoff & Culicover (Reference Jackendoff and Culicover2003: 538–539) argue that some force-dynamic predicates, which include predicates of causing, preventing, enabling, and helping, can correspond not only to the basic semantic configuration in (36a) but also to the configuration in (36b). In the latter case, ‘the subject is not acting on anything, it is just causing or preventing an event pure and simple’ (Jackendoff & Culicover Reference Jackendoff and Culicover2003: 539). According to this proposal, this would provide an explanation for the possibility of (37), in which the expletive is necessarily not an argument of the matrix verb, and the verb, which is usually a control verb, behaves here as closer to raising-to-object / Exceptional Case Marking (ECM) verbs.

In this subsection, we aim at arguing that implicative object control verbs indeed have a transitive (non-control) counterpart and that this explains part of their apparently special behaviour. The object control verb counterpart is ditransitive, i.e. with two internal arguments. Considering the behaviour of inflected infinitives is a cornerstone of the argumentation in this regard, the facts concerning animacy restrictions on DP2 and DP1 will be shown to follow from the analysis.

In the previous subsection, we have seen that implicative object control verbs allow inflected infinitives mismatching the number features of the DP2, a case in which we obtain a split control reading (a non-controlled reading is not available). The relevant examples are reproduced here:

In the case of a split control reading, both the matrix subject and the matrix object act as controllers. The fact that the split reading is obtained (contrary to what is predicted by Landau Reference Landau2015) is already a counterargument to the analysis of the control relation in (38) as resulting from a structure in which control corresponds to predication, with DP2 as the subject of an embedded small clause containing the infinitive: In that case, only the DP2 could be interpreted as the subject of the infinitive. To that extent, we take split control to signal a ditransitive structure.

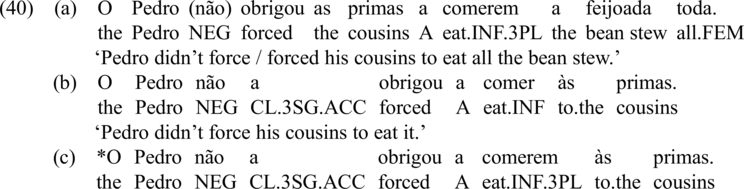

In the previous subsection, we have equally shown that this group of verbs can occur in faire-Inf configurations. Independently of the analysis of faire-Inf, which we will not discuss here, we expect it to affect the argument structure of the embedded predicate, with the external argument of this embedded predicate surfacing as a dative if the verb is transitive. Therefore, when faire-Inf occurs, the DP2 must be an argument of the embedded predicate and the structure cannot be ditransitive. A prediction follows: faire-Inf and split control should be incompatible. In (39) we show that this prediction is borne out.

Faire-Inf is in general unavailable with inflected infinitives, even if not mismatching the number features in the DP2 (40), as we can see by testing syntactic causatives (41).

We do not develop this issue here. For the goals of the paper, it will be enough to state that the infinitival domains under causative verbs, particularly, Type A causatives, as in (41), have been described by using a scale of defectivity: faire-Inf is the most defective structure, preventing the DP2 (causee) from checking nominative (cf. (31a), with a dative causee), and the inflected infinitive with a nominative subject (and necessarily showing verb-subject agreement) is the most complete domain (for EP, see Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1999; Martins Reference Martins, Brito, Figueiredo and Barros2004, Reference Martins, Santos and Gonçalves2018). However, both structures are only accounted for if the causative is analysed as a transitive verb, i.e. if the DP2 is merged in the infinitival clause: should this DP be merged in a position external to the infinitival complement and no explanation would be available either for the nominative with the inflected infinitive or for faire-Inf. In contrast, an inflected infinitive mismatching the DP2 in number features is only possible if this DP is not merged as a subject of the embedded infinitive. Therefore, faire-Inf remains an argument in favour of a transitive analysis of the verb (DP2 merged in the embedded infinitival clause), to the same extent as inflected infinitives mismatching DP2 in number argue for a ditransitive analysis of the verb (DP2 merged as a complement of the verb; if merged as the subject of the embedded infinitive, we would expect subject-verb agreement). In this case, the so-called implicative object control verbs are behaving here as syntactic causatives, that is, as transitive verbs, when they accept faire-Inf, and behaving as ditransitives when they occur with mismatching infinitives and induce split control readings.

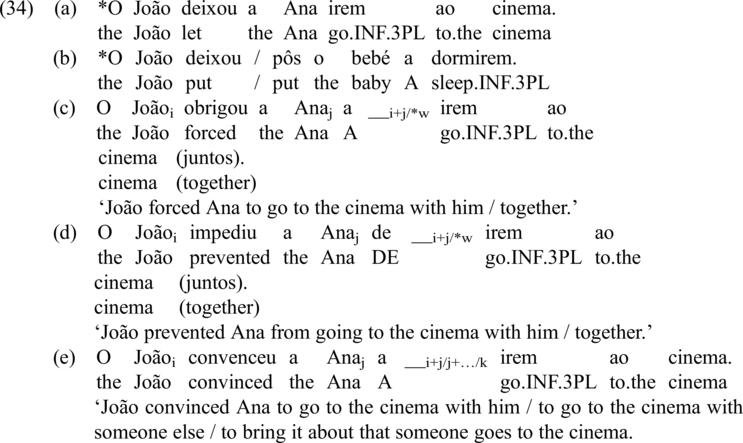

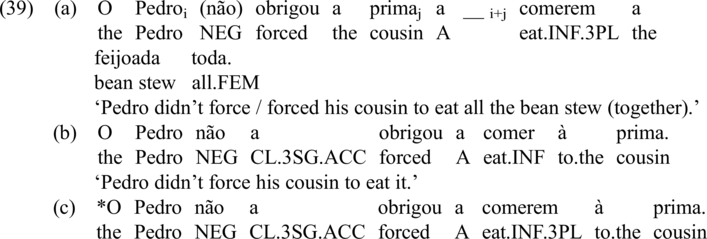

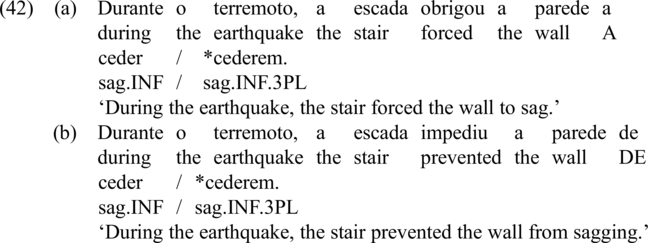

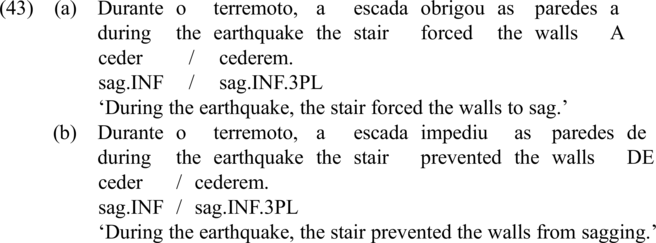

We should at this point come back to the animacy restrictions on DP2 to show how they interact with syntactic structure. We have seen in Section 2 that the so-called implicative object control verbs accept an inanimate DP2. However, mismatching inflected infinitives (and split control readings) are blocked when the DP2 is inanimate – see (42) – even though an inflected infinitive is allowed in the same context if the DP2 matches the number features in the infinitive (43).

The contrast between (42) and (43) shows that there is no general incompatibility between the inflected infinitive and an inanimate DP2; instead, there is an incompatibility between a mismatching inflected infinitive and an inanimate DP2. The explanation easily follows from the assumption of syntactic ambiguity of these structures: A mismatching inflected infinitive is only possible in a control (ditransitive) structure and is interpreted as a case of split control − this is the possibility blocked by an inanimate DP2; in contrast, the transitive counterpart of the verb, similar to a syntactic causative and thus compatible with an inanimate DP2, may take as complement an embedded inflected infinitive with a subject that necessarily matches its number features − to this extent, obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ in (43) behave as the syntactic causatives in (41a).

Therefore, we argue that the verbs obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’, i.e. the so-called implicative object control verbs, have a ditransitive counterpart, which indeed corresponds to an object control verb, and a transitive counterpart, which is similar to a syntactic causative. The ditransitive counterpart accepts mismatching infinitives with a split control reading and imposes a semantic restriction on its nominal internal argument (the DP2, in this case the object controller), which must be animate; the transitive counterpart allows faire-Inf – in this case, the DP2 is not selected by the matrix predicate and is therefore not subject to any semantic restrictions imposed by that predicate.

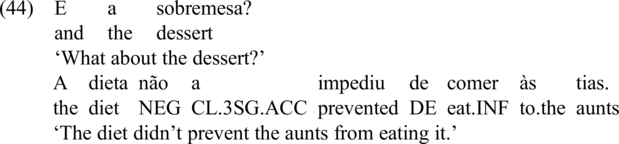

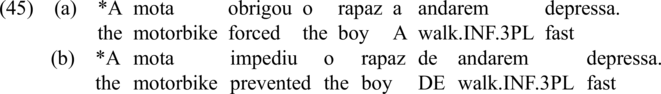

A further argument in the same sense comes from the semantic nature of DP1 (the matrix subject). As we have previously seen, the so-called implicative object control verbs accept both animate and inanimate subjects – see (21) in Section 3. As we can now see in (44), an inanimate DP1 can occur with the implicative verb in a faire-Inf construction; but importantly, it cannot occur with a mismatching inflected infinitive, with a split control interpretation (see 45).Footnote 6

We interpret these facts as meaning that the transitive counterpart of obrigar ‘force’ or impedir ‘prevent’ imposes more lenient semantic restrictions on the external argument, a fact that is compatible with the association of this argument with the thematic role of Causer and with the interpretation of the verb as a syntactic causative (instead of an object control verb).Footnote 7

We are therefore reaching an analysis that assumes the existence of obrigar ‘force’ and impedir ‘prevent’ (and also forçar ‘force’) as syntactic causatives, on a pair with its interpretation as ditransitives (and, in this case, object control verbs). We suggest that in the case they behave as transitives (and thus as syntactic causatives), the DP2 is merged in a subject position in the embedded domain. This is also what explains the possibility of an embedded expletive: The embedded expletive is possible under the transitive version of these verbs, to the same extent as it is possible under causatives – see (46) below. This suggestion goes along the lines of Jackendoff & Culicover (Reference Jackendoff and Culicover2003: 539), and, in line with their work, we assume that the interpretation of the causative version of the verb indeed corresponds to what is schematized in (36b) in the beginning of this subsection.

The transitive counterpart of the verb also allows for a finite complement (incompatible with a nominal internal argument of the same verb) – see examples in (24); (24b) is repeated in (47) below. In this case, we have evidence for a full complementizer phrase (CP) domain, with the finite complementizer que introducing the infinitival clause (and being preceded by the prepositional element a).

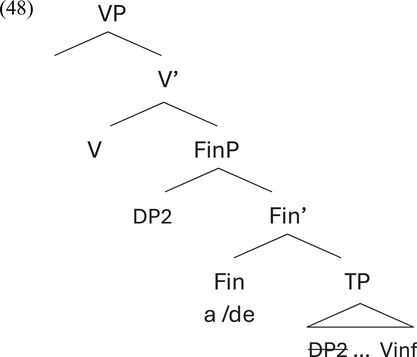

In the case of the transitive structure in which the verb occurs with an infinitival complement (the type of structure that is under discussion in this paper), we argue that the embedded infinitival clause is a defective CP, probably a FinP headed by a or de, grammaticalized as a prepositional complementizer. DP2 is merged as the subject of the infinitival verb and raises through tense phrase (TP) to the specifier (Spec) of FinP, the edge of the embedded domain, where it checks accusative Case via Agree with the matrix v.

We thus claim that the structure projected by the syntactic causative (i.e. the transitive) counterpart of the implicative verbs obrigar ‘force’, forçar ‘force’, and impedir ‘prevent’ corresponds to what is represented in (48):

This analysis can explain the special behaviour of these verbs, namely:

-

(i) The possibility of faire-Inf, resulting in the possible occurrence of a dative corresponding to the DP2 in the ditransitive structure, which is explained if DP2 is merged in the embedded domain as an argument of the verb in this domain - see (31c, d).

-

(ii) The impossibility of a mismatching embedded inflected infinitive when DP1 or DP2 are inanimate, since inanimate DPs are only compatible with the syntactic causative (i.e. the transitive) version of the verb, in (48), and a mismatching inflected infinitive signals a ditransitive (control) structure (see 42a, b).

-

(iii) The possibility of expletives in the embedded subject position, in the transitive version of the verb – (23 c, d) and (30 a–c) – when these expletives occur, they are merged as the subject of the embedded predicate and are not in a control configuration.

-

(iv) The transitive behaviour of the verb when used with a finite clause – see (24) and (47) – we assume that only the transitive version of these implicative verbs is compatible with a finite complement and corresponds to the interpretation in (36b).

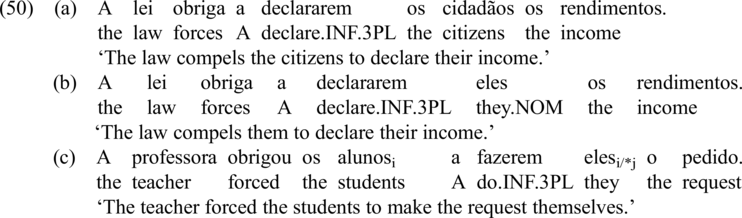

A final note should be added on Case and the embedded inflected infinitive in these structures. The structure in (48) assumes that the DP merged as a subject of the embedded predicate raises to the edge of FinP and checks accusative Case (49b). However, the availability of an inflected infinitive in the embedded position, as shown in the examples in (49), would suggest that nominative is available in the embedded domain. As we have previously shown in (27), reproduced as (50a), a DP can indeed be licensed as a subject in the embedded domain, even though typically in an inverted position. We take the nominative pronoun in (50b) to signal a domain in which nominative case is available. Note that this pronoun in (50b) cannot be taken as a bound pronoun, since we do not identify a controller (either explicit or implicit) in this sentence – this contrasts with (50c), a case in which the verb behaves as an object control verb and the embedded pronoun is bound by the controller (DP2).

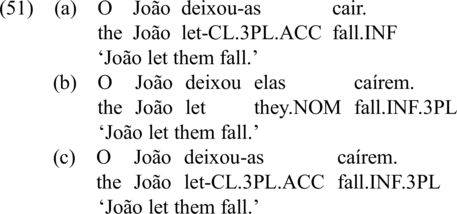

The observation of (49) and (50a, b) leads to the following generalization: When the embedded infinitive (under the transitive version of these verbs) shows overt inflection, the DP merged as the external argument of the embedded verb either checks nominative and stays in the embedded domain or raises to Spec, FinP, and checks accusative. This is exactly what has been shown to happen under other syntactic causatives in EP. As shown in Section 2, the structures in (51a, b), described as the norm, occur on a pair with (51c), which some speakers actually prefer over (51b). The possibility of (or even the preference for) (51c) has been noticed by Hornstein, Martins & Nunes (Reference Hornstein, Martins and Nunes2008) and Barbosa, Flores & Pereira (Reference Barbosa, Flores, Pereira, Guijarro-Fuentes and Cuza2018). According to Hornstein, Martins & Nunes (Reference Hornstein, Martins and Nunes2008), the inflected infinitive co-occurring with the accusative pronoun in (51c) is not a true inflected infinitive, since it is not specified for person (only the third-person plural is possible, signalling only a number contrast) – this defective form (in terms of phi-features) would not be associated with the availability of Case (nominative).

As for the issue of subject-verb inversion within the embedded clause in (50), and even though we will leave the issue open, we can say (i) that this type of inversion is found with inflected infinitives in other complement clauses (Raposo Reference Raposo1987) and also (ii) that this word order may be achieved with the embedded verb raising to the embedded T but with the DP staying in situ.

Landau (Reference Landau2015) suggests that implicative object control verbs (of the type of obrigar ‘force’) take as complement a constituent that is a domain of predication, with the object controller and the infinitive occupying the subject and predicate positions of a small clause (Landau takes this small clause to correspond to RelP). According to Landau (Reference Landau2015), control in this type of configuration corresponds to what he defines as predicative control and, in this case, we expect all phi-features of the subject (the controller) to be copied onto the predicate. The implicative reading in the case of predicative control would result from the predicative configuration (see a more explicit explanation in Landau Reference Landau2021). The data presented in this paper pose a challenge for this description and interpretation of the facts. To summarize it, we showed that implicative control verbs allow for split control readings with embedded inflected infinitives mismatching the object controller in number, and we have also shown that even in those configurations the implicative reading is maintained. A mismatching inflected infinitive would be difficult to explain if the controller and the infinitive are in a subject–predicate relation.

The analysis presented in this subsection suggests instead that the so-called implicative object control verbs are ambiguous between object control verbs, which are ditransitive, and syntactic causatives, i.e. transitive predicates that in this case take as their single complement a defective CP, a FinP. Only by considering this syntactic ambiguity do we explain the different restrictions on agreement in the embedded infinitive and on the animacy of the controller. This means that, contrary to what is suggested by Landau, we do not need to argue for the special status of predicative control in terms of the animacy of the controller or the (un)availability of split readings: What we are seeing is the ambiguity of these verbs, which can be more easily determined by looking at the inflected infinitives available in EP. We also reject the hypothesis that the implicative reading is derived from a particular syntactic configuration, namely a predicative configuration. More generally, we reject the idea that we can, at least in this case, infer the syntactic structure from semantics.

4.2. Type B causatives

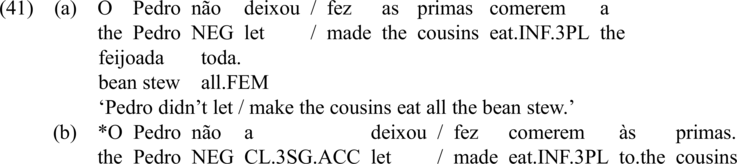

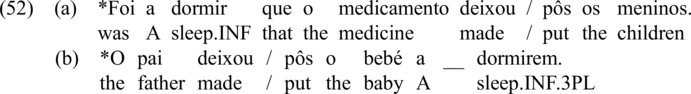

In this subsection, we consider Type B causatives, which occur in structures superficially similar to the structures of implicative object control verbs considered in the previous subsection. The behaviour of the Type B causatives deixar a ‘put to / make’ and pôr a ‘put to / make’ argues against an analysis of these verbs as ditransitives. This means that DP2 is not an argument of these verbs and is merged inside the infinitival domain. It cannot be left stranded when the embedded predicate is clefted – see (52a) – and, more interestingly, an embedded inflected infinitive mismatching DP2 is not allowed – see (52b). This is important if, as we claimed before, a mismatching inflected infinitive (interpreted as split control) signals a ditransitive structure:

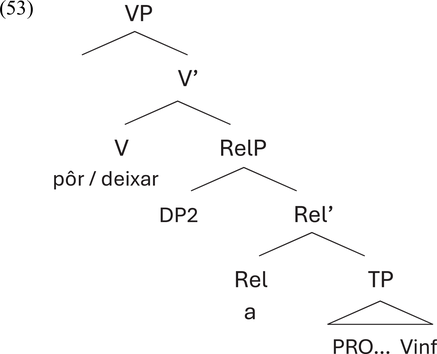

This behaviour of Type B causatives places them on a pair with Type A causatives and the so-called implicative object control verbs in their syntactic causative counterpart. However, as we showed in Section 3, Type B causatives differ from the two other classes in several aspects, justifying a different analysis of the embedded infinitival domain. In what follows, we recover the main features of the behaviour of Type B causatives presented in the previous subsections and develop an analysis suggesting that they select for a projection of a Relator head (in the sense of Den Dikken Reference Den Dikken2006), with DP2 merged in Spec, Relator phrase (RelP), and controlling the reference of the subject in the infinitival domain (we assume here the embedded subject to be a PRO, independently of the presence of inflection in the embedded domain, but we leave the issue open). This is close to the analysis suggested by Barbosa & Cochofel (Reference Barbosa, Cochofel, Duarte and Leiria2005) for the Prepositional Infinitival Construction (PIC) under perception verbs in EP, which is itself based on Raposo’s (Reference Raposo, Jaeggli and Safir1989) control analysis of the PIC. Notice, however, that Barbosa & Cochofel (Reference Barbosa, Cochofel, Duarte and Leiria2005) assume that the small clause is headless.

We propose that the preposition-like element a is the lexicalization of Relator (Den Dikken Reference Den Dikken2006), the head of a small clause. The fact that DP2 is merged outside the infinitival TP and controls the reference of the empty embedded subject distinguishes Type B causatives from Type A causatives and from the transitive counterpart of implicative object control verbs, such as obrigar ‘force’ or impedir ‘prevent’ (Section 4.1). Consider the following structure:

Merging DP2 in Spec, RelP directly explains the fact that DP2 always checks accusative Case, not nominative, even if the embedded domain contains an inflected infinitive:

As a clear argument in favour of the control approach inside the small clause (and in favour of directly merging the DP2 in Spec, RelP), we point to the fact that Type B causatives do not allow for embedded expletive subjects, a property that distinguishes these verbs from some Type A causatives and the implicative verbs discussed in the preceding subsection. In this sense, the ungrammaticality of (56) is expected if we consider that Type B causatives select for a RelP whose subject controls the empty subject of the infinitival domain: The impossibility of a controlled expletive explains the ungrammaticality.

In turn, Type A causatives (57a) and the transitive counterpart of implicative object control verbs (57b) can occur with expletive subjects in the infinitival domain, allowing the conclusion that control is not involved in those structures:

An additional argument comes from the unavailability of faire-Inf. Type B causatives differ from the other two classes of verbs under analysis in disallowing faire-Inf; see (58). This is expected if (53) represents the structure of the internal argument of Type B causatives. Since PRO, not DP2, occupies the subject position of the embedded TP, the reanalysis of the argument structure of the embedded verb that characterizes faire-Inf cannot involve DP2, thus DP2 cannot surface as a dative.

Finally, we suggest that a lexicalizes Rel under Type B causatives. We assume that, both under Type B causatives and under the syntactic causative version of the so-called implicative object control verbs (Section 4.1), there was grammaticalization of that form, which does not correspond to a lexical preposition. We should note that a is a highly ambiguous form in EP: It behaves as a preposition but also as a dative marker (see Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2015 and references therein), an aspectual marker (e.g. under the semi-auxiliary estar a ‘be + V.GER’, Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1992; also in the PIC, Duarte Reference Duarte1992, Barbosa & Cochofel Reference Barbosa, Cochofel, Duarte and Leiria2005). In addition, we note that the form de, found under the so-called implicative object control verb impedir ‘prevent’, is also ambiguous: It behaves as a preposition, but it is also found under raising semi-auxiliaries as acabar de ‘finish + V.GER’ (Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1992).

In sum, in this subsection, we showed that Type B causatives select for one single internal argument, like syntactic causatives and the transitive counterpart of implicative object control verbs. However, in the case of Type B causatives, DP2, which checks accusative Case in the domain of the matrix verb, is the subject of RelP, and controls the subject position of the infinitival TP. In contrast, and as shown in Section 4.1, the internal argument of the transitive counterpart of implicative object control verbs is a FinP. In this case, DP2 is merged inside the embedded TP, and raises to Spec, FinP.

4.3. The case of mandar ‘order’

In the present subsection, we briefly consider the special case of the causative mandar ‘order’ in EP. It is not our goal to fully develop an analysis of this causative verb, either in a synchronic or a diachronic perspective. Instead, by considering some aspects of the syntax and interpretation of this causative, we will be able to develop our argument that an implicative interpretation is not necessarily a consequence of a particular syntactic structure.

The verb mandar ‘order’ has been analysed as a syntactic causative alongside with other Type A causatives, namely, fazer ‘make’ and deixar ‘let’ (for EP, see among others Raposo Reference Raposo1981; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1999; Martins Reference Martins, Brito, Figueiredo and Barros2004, 2018). As already mentioned in the previous subsections, all these verbs occur with a finite complement or an infinitival one; in the latter case, Type A causatives occur either in the string [DP1 Vcaus DP2 Vinf] or in faire-Inf. The main difference between these syntactic structures relies on the size of the complement, defined in the literature as the number of functional heads projecting in the embedded domain and their completeness or defectiveness (see, among others, Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1999; Hornstein, Martins & Nunes Reference Hornstein, Martins and Nunes2008; Torrego Reference Torrego2010; Sheehan & Cyrino Reference Sheehan, Cyrino, Hucklebridge and Nelson2018, Reference Sheehan and Cyrino2024): The inflected infinitival complement is the projection of a complete TP, DP2 bearing nominative Case (or a defective T, if DP2 exhibits accusative); in typical raising-to-object with an uninflected infinitive, the infinitival complement is a projection of a Case-defective T, DP2 being marked for accusative Case; and the complement in faire-Inf is a projection of V lower than T, be it VP, VoiceP, vP, or IncausP, DP2 being marked as accusative or dative, depending on the transitivity of the embedded predicate (Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves1999).

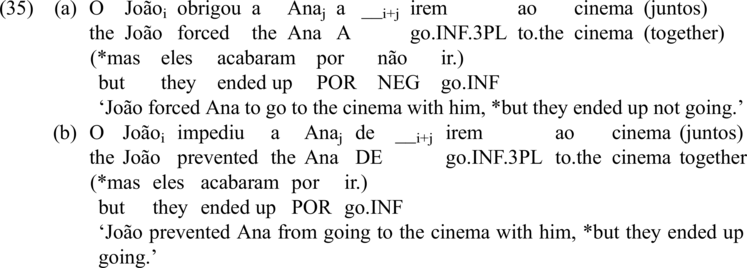

Regardless of the specific category of the embedded infinitival domain, DP2 is always merged inside this domain, which is the single internal argument of Type A causatives. Thus, in all cases, a split control reading is precluded, as it happens with Type B causatives but not with object control verbs:

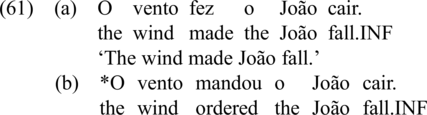

Nevertheless, the verb mandar has a particular behaviour among Type A causatives. First, it does not allow an inanimate DP2, contrary to deixar ‘let’ and fazer ‘make’ and to the verbs of the type of obrigar ‘force’:

A semantic restriction on DP1 is also observed, non-human subjects being excluded:

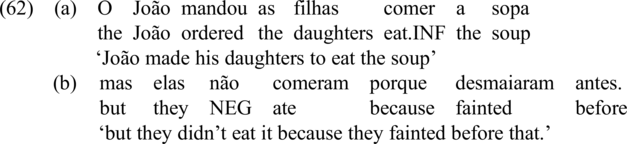

Second, mandar does not have an implicative reading, contrary to the other syntactic causatives we are analysing. Thus, (62a) is possible with a continuation excluding an implicative interpretation.

These differences lead us to conclude that mandar preserves the agentive reading it has as a declarative verb of order, even when it behaves as causative, being less semantically bleached than the other verbs we are analysing, especially the other Type A causatives and Type B causatives. Moreover, this verb is an exception in the scenario of Romance languages. Indeed, if we consider other Romance languages, such as French (Kayne Reference Kayne1975), Italian (Guasti Reference Guasti1993), and Spanish (Torrego Reference Torrego2010), there is no direct equivalent to mandar, and causatives are restricted to the equivalents of deixar ‘let’ and fazer ‘make’.

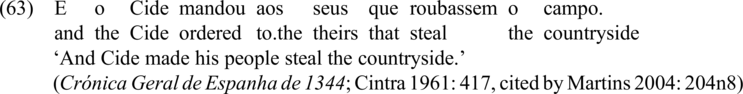

The diachronic path of mandar ‘order’ is particularly interesting and is compatible with the fact that mandar ‘order’ retains its semantic value as a declarative verb of order similar to pedir ‘ask’ or dizer para ‘tell to’ and confirms that this verb is less semantically bleached than the other causatives. As Martins (Reference Martins, Brito, Figueiredo and Barros2004) suggests, in Ancient Portuguese a ditransitive version of this verb, illustrated by (63), may have coexisted with a structure compatible with an ECM analysis.

The structure in (63) is no longer available in contemporary Portuguese, a variety in which the verb behaves as a syntactic causative, even though in his well-known traditional grammar, Dias (Reference Dias1918) presents examples of the same construction in EP, allowing the suggestion that the construction lasted until this point. Galician and Spanish still allow a finite ditransitive structure in the context of mandar (Sousa Fernández Reference Sousa Fernández1998).

The diachronic note concerning mandar ‘order’ suggests that there are other verbs among the semantic class of causatives, besides the so-called implicative object control verbs (i.e. the verbs of the type of obrigar ‘force) that have (or have had) both a ditransitive and a transitive counterpart. Moreover, these observations with respect to the syntactic causative mandar ‘order’ allow us to add an argument in favour of the independence between syntactic structure and the interpretation of different causative verbs. Whereas in Section 4.1. we showed that the implicative reading does not necessarily result from a predicative structure (the so-called implicative object control verbs maintain this reading both in their transitive counterpart, in which we find an embedded predicative structure, and in their ditransitive, control, counterpart), we now show that a syntactic causative, mandar ‘order’, which shares the syntactic properties of Type A causatives, may maintain the reading of declaratives of order, which are typically object control verbs (e.g. dizer para ‘tell to’), and the same semantic restrictions on its arguments (namely, selection of an agentive external argument). The behaviour of mandar ‘order’ also highlights the central status of the inflected infinitive as a test allowing to distinguish a ditransitive (control) structure from a transitive structure in which DP2 is a subject in an embedded complement: The impossibility of an inflected infinitive mismatching DP2 in number features (and interpreted as a case of split control) under mandar ‘order’ is in agreement with the exclusion of this verb from the set of object control verbs.

5. Conclusion

By exploring the syntactic similarities and differences between a small set of object control verbs − those that can be described as implicative object control verbs − and syntactic causatives, we have reached the conclusion that those verbs are ambiguous between true control verbs (which we argue to be ditransitive) and verbs that take a single internal argument and show the behaviour of a syntactic causative. A central piece of the argumentation was built upon the distribution and interpretation of inflected infinitives (which are a specificity of EP), even though the idea of ambiguity among the class of control verbs is not new and may be relevant for the explanation of both syntactic and semantic facts (see Jackendoff & Culicover Reference Jackendoff and Culicover2003). By identifying the ambiguity affecting this class of object control verbs, we avoided the need to assume that this particular subclass of control verbs allows for inanimate controllers: As we have seen, an inanimate DP in the position of the causee / controller is not compatible with an embedded inflected infinitive that does not match this DP in phi-features, and this is explained if this DP is indeed generated as the subject of the embedded infinitive. This analysis also explains the otherwise mysterious fact that faire-Inf is possible under the transitive counterpart of these verbs. Therefore, and contrary to Landau (Reference Landau2015), we do not need to postulate a special type of control corresponding to predication. Instead, we argued that (i) these verbs may take a single complement, a FinP, with an embedded subject raised to Spec, FinP, but (ii) they maintain the possibility to project a ditransitive structure in which the internal argument of the matrix verb controls the subject of an infinitival clause. The facts of EP allow to unravel the issue and distinguish the two different structures.

By comparing object control verbs that exhibit the behaviour of syntactic causatives with verbs that occur in a superficially similar context, we were able to discuss the status of the understudied verbs pôr a ‘put to’ / ‘make’ and deixar a ‘make’, which we named Type B causatives. The same criteria used to support the ambiguity of implicative object control verbs show that Type B causatives are non‑ambiguous transitive verbs. We argue that Type B causatives select for a small clause complement, a projection of a head Relator. In this case, DP2 is merged in [Spec, RelP] and controls the subject of the embedded infinitival clause, in a structure similar to the PIC under perception verbs in EP.

The observation of the interpretation and syntactic behaviour of these verbs allowed to argue that the implicative interpretation of object control verbs is independent of the syntactic structure (contrary to the assumption of Landau Reference Landau2015, Reference Landau2021). In addition, we briefly discussed the syntactic causative mandar ‘order’ in Portuguese, another case in which the interpretation is not affected by the syntactic structure.

Acknowledgements

This work was developed at the Center of Linguistics of the University of Lisbon (UID/00214: Centro de Linguística da Universidade de Lisboa), funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT). We would like to thank the editor, the anonymous reviewers for their very useful and constructive comments, and the audience of Our ID: Conference in Honor of Inês Duarte, where we presented a first and very preliminary version of this paper. We also wish to thank Marcel den Dikken for the discussion of some parts of this paper, Rui Marques for very useful comments, and Nélia Alexandre for her help with the data judgements. Finally, we benefited from discussion with Idan Landau about an earlier paper by the first author. Needless to say, all errors are ours.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.