Introduction

Workplace bullying is characterized by repeated and unreasonable behaviour directed toward an employee or group, creating a risk to health and safety. While there are no universally accepted definitions, scholars such as Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf, and Cooper (Reference Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf and Cooper2020) emphasize its persistence and power imbalance. WorkSafe New Zealand (2017) defines workplace bullying as repeated behaviour that is directed at an individual or group and creates a health and safety risk. In contrast, negative workplace interactions such as assertive communication, strong leadership, or performance management, a formal organizational process involving setting expectations, monitoring progress, and providing feedback to ensure that employees meet their goals and contribute effectively to the organization (Aguinis, Reference Aguinis2013) may be perceived as bullying but do not meet the definitional criteria. The 2011 article by Lutgen–Sandvik and Tracy, titled ‘Answering Five Key Questions About Workplace Bullying: How Communication Scholarship Provides Thought Leadership for Transforming Abuse at Work’, has been influential in the field of workplace bullying research. They, alongside more recent researchers (D’Cruz, Noronha, & Lutgen-Sandvik, Reference D’Cruz, Noronha and Lutgen-Sandvik2018; Harlos, Reference Harlos2017; Lempp, Blackwood, & Gordon, Reference Lempp, Blackwood and Gordon2020), have explored the complex dynamics of power and subjectivity in workplace bullying, emphasizing the importance of contextual understanding. These definitions, however, are shaped by interpersonal communication and power dynamics, and behaviours may be interpreted differently based on context, intent, and perception.

Bullying in the workplace is a counterproductive behaviour often perpetrated by people in positions of authority (bosses/managers, supervisors, executives, and sometimes peers) against those with less power. It is mostly non-physical, passive, and an indirect form of aggression. Within organizational communication, workplace bullying refers to the negative, harmful, and sometimes hostile and aggressive communication present in organizations (Cowan, Clayton, & Bochantin, Reference Cowan, Clayton and Bochantin2021).

Problematic workplace behaviour falls on a continuum with incivility on one end, and harassment on the other (Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Cortina, Magley, Williams, & Langhout, Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001). For example, if a co-worker unwittingly says insensitive things to just about everybody, they may have poor social skills, but they likely don’t intend to upset someone. Some authors suggest incivility is in fact more insidious because it occurs in day-to-day interactions. As these types of behaviours are part of most workplaces it makes incivility difficult to categorize and create policies to prevent and combat. Similarly, humorous exchanges can be intentional bullying, or just an attempt at humour. Researchers have recognized humour to have the ability to obscure perpetrator intentions, making it difficult for victims to subjectively perceive jokes as harmless or hostile, bullying behaviour (Carrera, DePalma, & Lameiras, Reference Carrera, DePalma and Lameiras2011). Tone, pitch, and facial expressions can shift the interpretive frame of a message, as outlined in Gumperz’s (Reference Gumperz1982) concept of contextualization cues, and are central to Infante’s (Reference Infante1987) idea that aggression is perceived, not merely enacted. One form of behaviour, which has been reported to be both humorous and aggressive in relation to bullying behaviour, is teasing or banter (Dynel, Reference Dynel2008; Khosropour & Walsh, Reference Khosropour and Walsh2001; Kowalski, Reference Kowalski2000). The fine line between pro-social teasing and anti-social verbal bullying behaviour has been acknowledged within the bullying literature (Kruger, Gordon, & Kuban, Reference Kruger, Gordon and Kuban2006; Mills & Carwile, Reference Mills and Carwile2009). Hurtful teasing or hurtful cyber-teasing are deliberate verbal aggression intended to cause distress to the victim (Infante, Reference Infante1987; Madlock & Westerman, Reference Madlock and Westerman2011; Merkin, Reference Merkin2009; Warm, Reference Warm1997). General teasing can be defined as ‘the juxtaposition of two potentially contradictory acts: (a) a challenge to one or more of the target’s goals and (b) play’ (Mills & Babrow, Reference Mills and Babrow2003, p. 278). Similarly, banter has been described as a playful interaction between individuals that serves to improve the relationship, which can involve innocuous aggression (Dynel, Reference Dynel2008). The contrast between challenge and play can create an ambiguous social interaction and requires non-verbal social cues, such as tone, the vocal quality or attitude expressed through voice modulation, which influences the emotional and interpretive framing of a message (Gumperz, Reference Gumperz1982) and facial gestures (Dehue, Bolman, & Völlink, Reference Dehue, Bolman and Völlink2008; Shapiro, Baumeister, & Kessler, Reference Shapiro, Baumeister and Kessler1991), to contextualize the interaction and display hurtful or benign intention.

Workplace bullying therefore seems to have become a ubiquitous part of organizational life, with recent studies indicating that approximately 30% of employees experience bullying at some point in their careers (WorkSafe New Zealand, 2017).

Workplace bullying in New Zealand has been a significant concern, with studies indicating its prevalence across various sectors. (Catley, Reference Catley2022; Haar, Reference Haar2023; New Zealand Human Rights Commission, 2022). The 2018 Workplace Bullying and Harassment Survey revealed that bullying is more common in hierarchical organizations and sectors such as healthcare, education, and public service. New Zealand’s legal framework, including WorkSafe guidelines and the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, outlines employer responsibilities in preventing and addressing bullying. However, gaps remain in how managers interpret and enforce these definitions in practice.

The fundamental aim of this research is to deepen our understanding of the bullying concept rather than to necessarily predict and control dysfunctional behaviours at work.

New Zealand is a challenging environment for examining workplace bullying due to its unique cultural diversity, varying definitions of bullying across organizations, and the integration of both broad central government policy definitions and academic definitions. New Zealand addresses both bullying and harassment under employment legislation, as key considerations in providing and maintaining a safe and healthy workplace under workplace safety (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Teo, Nguyen, Blackwood, Catley, Gardner and Port2021; Blackwood, Bentley, & Catley, Reference Blackwood, Bentley and Catley2018; Catley et al., Reference Catley, Bentley, Forsyth, Cooper-Thomas, Gardner, O’Driscoll and Trenberth2013). The concept of bullying itself is also both poorly understood and differently defined depending on whether organizations take a broad central government policy definition or an academic definition.

However, questions arise where bullying is reaching the touted epidemic proportions in New Zealand, or is there a misplaced public perception, something fed in part by increased attention to the problem? Further, considering the ‘Me-Too’ culture, are we seeing an increase in the reporting of behaviours that have existed at similar levels for some time, rather than seeing a spike in actual behaviours themselves? When examining bullying from a communicative approach in the New Zealand context, questions arise that when answered may help disentangle the conceptual morass that surrounds bullying.

Key questions are raised by the research, what is bullying; and how is it communicated, and manifested? As the research seeks to understand bullying as a communicative construct, occurring between managers and subordinates, we need to consider related communication constructs that help clarify the interaction and communicative act as it occurs.

Infante’s (Reference Infante1987) work on argumentativeness and verbal aggression provides a lens to examine how bullying perceptions may be shaped by communication behaviours. Infante argued that verbal aggression could be assessed from a source, receiver, message, or legal perspective, influencing how managers distinguish between constructive conflict and bullying. This study integrates Infante’s framework to analyse how managers interpret workplace interactions. To further interrogate how communication behaviours contribute to perceived bullying, Infante’s (Reference Infante1987) theory of verbal aggression and argumentativeness provides a useful analytical lens.

Verbal aggression

Verbal aggression is a common component of workplace bullying. (Goodboy, Martin, Mills, & Clark-Gordon, Reference Goodboy, Martin, Mills and Clark-Gordon2022; Plimmer, Nguyen, Teo, & Tuckey, Reference Plimmer, Nguyen, Teo and Tuckey2022; Tootell et al., Reference Tootell, Croucher, Cullinane, Kelly and Ashwell2023). Verbal aggression can be a primary means through which workplace bullying occurs. Verbal aggression specifically refers to the use of aggressive or hostile language to demean, criticize, threaten, or hurt someone, Infante and Wigley (Reference Infante and Wigley1986, p. 61) defined aggressive behaviour in interpersonal communication as ‘a joint product of the individual’s aggressive traits and the way the person perceives the aggressive inhibitors and disinhibitors in the given situation’. In the workplace context, verbal aggression involves using words, tone, or gestures to assert power and control over others, often causing distress and discomfort. These can include yelling, name-calling, insults, derogatory remarks, offensive language, and other forms of harmful verbal communication. Bullies may use harsh language, insults, and demeaning comments to belittle their targets, erode their self-esteem, and maintain control over them. However, workplace bullying can also extend beyond verbal interactions to include non-verbal actions and behaviours, such as sabotage, areolation, and undermining work tasks.

Verbal aggression can be a tool or tactic employed within a broader pattern of workplace bullying (Quinn, Waheduzzaman, & Djurkovic, Reference Quinn, Waheduzzaman and Djurkovic2024). While not all instances of verbal aggression qualify as workplace bullying, it becomes a significant concern when it is part of a systematic and ongoing campaign to degrade and harm a person or group within the professional setting. It’s important for organizations to address both verbal aggression and broader patterns of workplace bullying through policies, training, and supportive interventions to create a healthy and respectful work environment.

Organizational communication and bullying

Organizational communication research may be beneficial for developing better understanding and potential for addressing workplace bullying because of its capacity to profile the complexity of workplace bullying (Keashly, Reference Keashly2001; Lutgen-Sandvik, Reference Lutgen-Sandvik2003). Organizational communication scholars joined the academic conversation about workplace bullying in the early 2000s (Keashly, Reference Keashly2001; Lutgen-Sandvik, Reference Lutgen-Sandvik2003). Organizational communication research shows that bullying is a complex multilevel issue occurring not only inside organizations but also one that is inextricably interconnected with larger social systems of meaning (i.e., discourses) and institutional policies.

Organizational communication researchers conceptualize bullying as a systemic issue that, to a great degree, develops from organizational practice and policy. As Keashly (Reference Keashly2001) notes, organizational representatives rarely doubt or deny that bullies act the way recipients describe. Nonetheless, even when senior managers accept the veracity of recipient’s reports, most of their responses typically fail to end the behaviours. In only a third of cases do manager responses result in improving the recipient’s situations (Namie & Lutgen-Sandvik, Reference Namie and Lutgen-Sandvik2010). Organizational communication research provides considerable insight into the ways individuals make sense of workplace bullying through the field’s complex understanding of voice, particularly whose voice are privileged in research (Lutgen-Sandvik, Reference Lutgen-Sandvik2006; Mumby & Stohl, Reference Mumby and Stohl1996).

Communication research also provides a distinctive contribution by exploring the narrative form of worker responses to perceived bullying. However, labelling an individual’s behaviours as bullying or harassment could be difficult because the meanings and interpretations given to communicative behaviour vary from one person to another. The same phrase, gesture, laughter, or touch might be interpreted differently by various recipients who will assess that phrase, etc., by considering previous interactions with the other. Therefore, the same kind of message can be received as a spontaneous, harmless joke by one person and as a repeated, painful insult by another. Similarly, the ability of an individual to defend themself might be estimated from the verbal and non-verbal messages they send, and they must also be interpreted considering the previous knowledge gained of the sender and the relationship they have with the alleged bully.

Disputed acts of bullying

Recognizing communicative acts may be interpreted differently by different actors, this research examines whether some acts described as bullying are indeed something else. Despite New Zealand having a legal definition of bullying, it is difficult for managers to identify it empirically due to varying interpretations of behaviours and the subjective nature of perceived intent and impact.

In communication theory, noise refers to any interference that distorts or disrupts the transmission or interpretation of a message between sender and receiver. This interference can be physical, psychological, semantic, or physiological in nature (Adler, Rosenfeld, & Proctor, Reference Adler, Rosenfeld and Proctor2018). Misinterpretation occurs when a message is received and understood differently from the sender’s intended meaning. While noise may contribute to a misinterpretation (e.g., due to unclear wording or distraction), the key distinction is that misinterpretation centres on cognitive decoding errors, not necessarily interference. For example, a listener may misinterpret a sarcastic remark as sincere due to contextual ambiguity – even in the absence of noise. Microaggressions, by contrast, are subtle, often unintentional, verbal or non-verbal slights or insults directed at marginalized groups, often based on race, gender, or other identities. Unlike noise or misinterpretation, microaggressions are socially embedded and reflect systemic bias or power dynamics. From a constructivist perspective, both misinterpretation and noise highlight how communicative meaning is co-created, negotiated, and often unstable. While a microaggression can be misinterpreted or obscured by noise, its defining feature is that it conveys implicit prejudice, whether it is consciously delivered.

Psychological noise refers to the internal distractions or biases within an individual’s mind that affect their ability to comprehend or engage with a message (Tazelaar, Van Lange, & Ouwerkerk, Reference Tazelaar, Van Lange and Ouwerkerk2004). The types of noise are highly subjective and can vary significantly based on cultural background, age, and upbringing. Psychological noise can also be influenced by individual differences such as personality traits, cognitive biases, emotional states, and psychological disorders (Van Lange, Ouwerkerk, & Tazelaar, Reference Van Lange, Ouwerkerk and Tazelaar2002). For example, someone with high levels of anxiety may be more prone to interpreting neutral statements as threatening, resulting in psychological noise that hinders effective communication.

Psychological noise and verbal aggression can interact in several ways, exacerbating the negative effects of both. Psychological noise can interfere with the accurate interpretation of verbal messages, leading to a misinterpretation of the intentions or tone of verbal communication or the perception of statements as aggressive or hostile. The interaction between psychological noise and verbal aggression underscores the importance of fostering a supportive and respectful communication environment, where clear and empathetic communication practices are encouraged.

Therefore, key elements of the definition of bullying are open to perception and interpretation. These ambiguous acts – such as dissent or managerial prerogative – challenge binary definitions of bullying and require a communication-centred approach to decipher meaning and intention. This study attempts to uncover several acts that could be interpreted in various ways, which may or may not be considered bullying: (1) acts identified ‘by others’ as bullying but not by respondents, such as workplace deviance, voluntary behaviour that violates organizational norms and threatens the well-being of the organization or its members (Robinson & Bennett, Reference Robinson and Bennett1995); (2) managerial prerogative, where managerial prerogative is the recognized authority and discretion of managers to make decisions regarding work direction, discipline, and performance within organizational and legal limits (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2016) that may be perceived as bullying; (3) work that is beyond a colleague’s competence (tasks that are too challenging but not unreasonable workloads); (4) misplaced humour that is inappropriate in tone, timing, or target, which may unintentionally offend or be perceived as hostile (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000); and other counter-productive workplace behaviours, such as dissent, the expression of disagreement or contradictory opinions about organizational practices, policies, or decisions (Kassing, Reference Kassing1998).

The most common self-report method, the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R), developed by Einarsen et al. (Reference Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf and Cooper2020), measures the frequency of various negative acts experienced by individuals. However, it has yielded little to no published validity evidence in the New Zealand context. A pilot study conducted by the primary researcher provided weak validity results, suggesting New Zealand respondents may understand bullying differently from respondents from other contexts, or it may be conceived of inconsistently within New Zealand. In addition, previous empirical research by Tootell et al., (Reference Tootell, Croucher, Cullinane, Kelly and Ashwell2023) found New Zealanders perceive bullying and dissent as highly related concepts. Individuals who score high on organizational dissent are perceived as high on bullying (Tootell et al., Reference Tootell, Croucher, Cullinane, Kelly and Ashwell2023).

Research is divided on how bullying is defined within a workplace context. As reports of workplace bullying are on the rise, particularly in the New Zealand context, managers are increasingly having to address and manage these issues effectively. It is therefore imperative to examine their understanding of precisely what constitutes bullying. Thus, the research question is: RQ: How is bullying understood by managers in New Zealand workplaces?

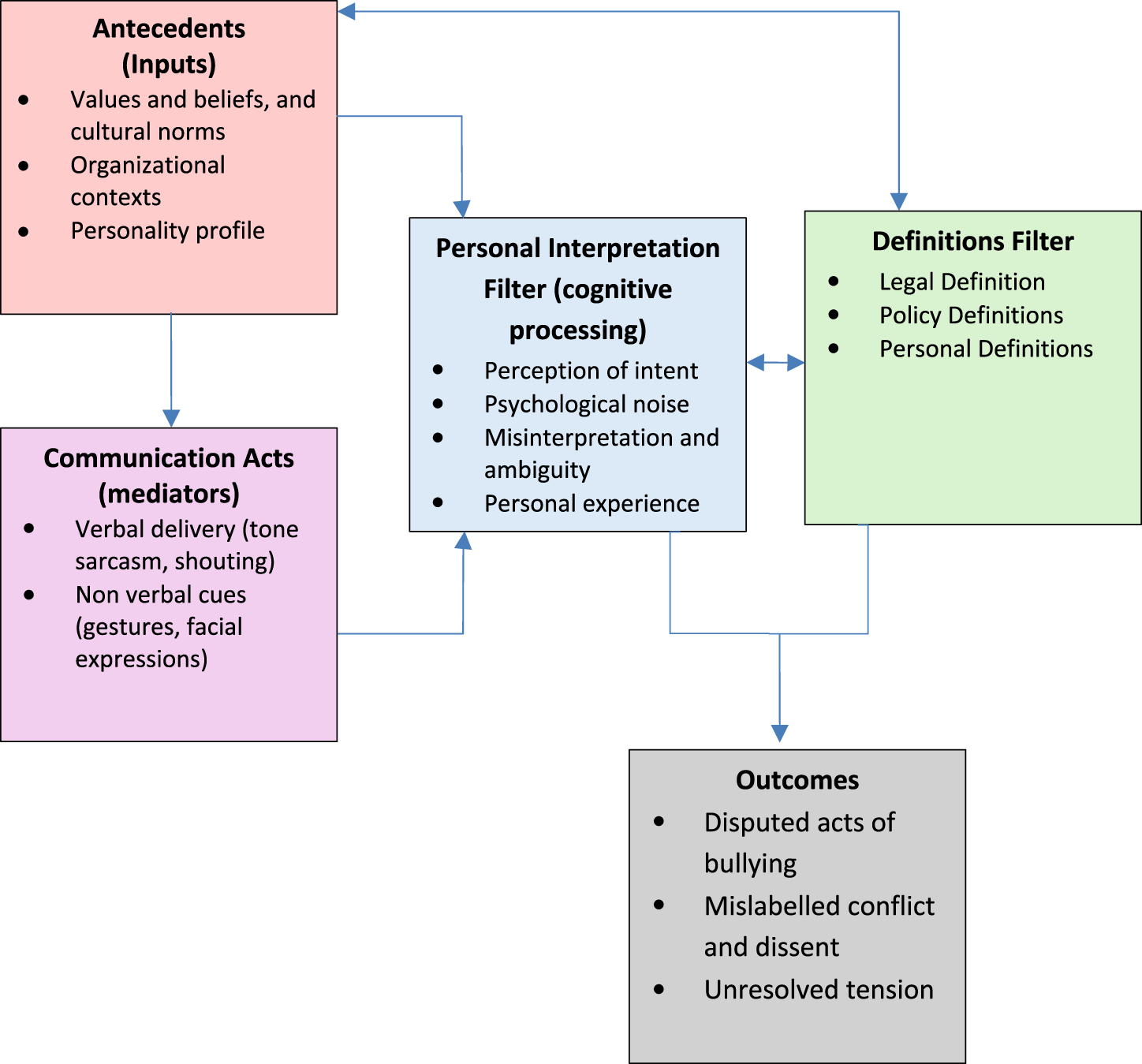

This study adopts a communication-centred lens to explore how New Zealand managers interpret and distinguish workplace bullying from other forms of workplace conflict. Grounded in a constructivist paradigm, the research emphasizes the socially constructed nature of bullying perceptions, recognizing that meaning is shaped through language, context, and interpersonal dynamics. Rather than proposing a new communication model, the study applies established theories from interpersonal and organizational communication – including Infante’s (Reference Infante1987) framework on verbal aggression and argumentativeness, as well as concepts such as noise (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Rosenfeld and Proctor2018) and organizational dissent (Kassing, Reference Kassing1998) – to examine how contested communicative acts are interpreted by managers. The aim is to uncover definitional inconsistencies and surface the communicative ambiguities that lead certain managerial behaviours to be viewed as bullying by some, but not by others. This approach positions bullying not merely as an objective behaviour, but as a meaning-making process embedded in communicative exchanges shaped by tone, context, and power. By synthesizing interpersonal communication theories such as Infante’s (Reference Infante1987), dissent theory (Kassing, Reference Kassing1998), and organizational communication insights the study offers a nuanced framework for interpreting contested workplace interactions.

Methods

Procedure

Responses were collected from 316 New Zealand managers. Participants were recruited using a randomized panel through the Qualtrics service. To ensure the integrity and reliability of the data collected through the online survey, multiple quality control measures were implemented. Data quality was safeguarded using Qualtrics’ built-in fraud detection tools, screening for duplicate responses, and enforcing minimum engagement time thresholds to filter out inattentive or automated submissions. Although online surveys inherently carry some risk of fraudulent or low-quality responses (Ballard & Montgomery, Reference Ballard and Montgomery2017), research indicates that when appropriate validation techniques are applied, online data collection can yield data comparable in reliability to traditional survey methods (Teitcher et al., Reference Teitcher, Bockting, Bauermeister, Hoefer, Miner and Klitzman2015).

The data were collected through anonymous, online open-ended survey responses consisting solely of text. This method was chosen to encourage candid and uninhibited participation, reducing social desirability bias and allowing respondents to express their experiences and perceptions freely. While the lack of face-to-face interaction limits opportunities for probing or clarification, the textual data provide rich qualitative insights directly from participants’ own words. The online format also enabled a broad and diverse sample, enhancing the relevance and generalizability of the findings within the study context. Whilst it may be seen as a limitation that participants were not provided with a standardized definition of workplace bullying, potentially influencing their interpretations, this was an intentional decision by the researchers, as we seek to construct how participants independently perceive bullying.

All respondents were asked open-ended questions, as well as demographic questions. This was part of a larger study, with several quantitative responses sought, the results of which are reported here (Blinded 2023). Responses were anonymous. The questionnaire was distributed by Qualtrics to a randomized panel of working individuals in New Zealand, specifically targeting managers. Supervisors were included in the definition of managers. The sample included participants from various industries, ensuring a diverse representation. The research questions guiding this study were: (1) How do managers in New Zealand define workplace bullying? (2) How do these definitions compare to legal and academic definitions? (3) What factors influence managers’ perceptions of bullying? The survey took approximately 10–15 min to complete.

Open-ended questions and data analysis

Participants were asked two open-ended questions that assessed their understanding/perception of bullying in the workplace. The open-ended questions were designed to (1) understand how respondents understood or described bullying and (2) ask respondents to reflect on an incident where others described it as bullying but which they would have described as something else.

Thematic analysis was used to examine the qualitative data. Initial intercoder reliability was 89%. This analysis followed the six-phase approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2021), which provides a theoretically flexible yet rigorous method for identifying, analysing, and interpreting patterns of meaning (themes) across the dataset. The analysis was informed by an interpretivist paradigm, recognizing that meaning is socially constructed and contextually situated. While the analysis was inductive in nature, it was also sensitized by existing theoretical literature on workplace bullying and managerial sense-making, which informed the coding framework and interpretation of themes. In particular, we drew on conceptual understandings of bullying as contested, relational, and embedded within organizational power dynamics.

Initial familiarization with the data involved multiple readings of participant responses, followed by systematic coding and theme development. Codes were iteratively refined and grouped into broader themes that captured recurring patterns and conceptual insights relevant to the research questions. To ensure the rigour and credibility of the thematic analysis, intercoder reliability was established through a systematic process in which two researchers independently coded a subset of the data. Coding consistency was assessed through iterative comparison and discussion of discrepancies, following best practices in qualitative research (O’Connor & Joffe, Reference O’Connor and Joffe2020). Agreement was reached through consensus, strengthening the dependability of the coding framework and enhancing the transparency of the analytical process (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014).

Consent for the research was obtained from the University Ethics Committee. Any possible harm to participants through the elicitation of experiences were addressed through the design of the questionnaire, for example the focus on opinions means that general discussion around the extent of the problem could occur without participants having to share personal experiences. Participants were asked to expand on experiences of reported bullying behaviours, rather than personal experiences.

Findings

Three key themes were identified in the analysis. Before presenting these themes, it is helpful to contextualize the demographic profile of the participants and the qualitative richness of their contributions. An analysis of participant demographics (N = 316) revealed a broad cross-section of employees across sectors and organizational levels. The most common age reported was 37, with industries represented including construction, healthcare, education, and retail. Respondents held a range of job titles, with mid-level roles being most common, and tenure in organizations typically ranged from three to eight years. Most participants were employed full-time (approximately 75%) and all identified as New Zealand citizens or residents. Excluding Q71 – a yes/no question – from the open-ended dataset, 99.4% of participants provided at least one open-ended response, with word counts ranging from brief remarks to extended narratives of over 2,300 words. The median response length was 156 words. Those providing the most detailed responses were often aged between 35 and 56, working in managerial positions, particularly within the healthcare sector. Qualitative themes emerging from these responses included personal experiences of bullying, perceptions of toxic leadership, feelings of isolation, and dissatisfaction with how human resources or senior leaders addressed conflict. These findings demonstrate the depth and emotional intensity conveyed in the open-ended data, reinforcing the importance of narrative insight alongside quantitative analysis in organizational studies.

First, ‘how’ communication was delivered was a key deciding factor in whether respondents would define an incident as bullying. Second, the respondents did not have the same clarity of what bullying was when compared with what organizations may have in their policies. Third, any non-productive communication behaviours, which fails to contribute to constructive, respectful, or goal-oriented workplace interactions, potentially including sarcasm, passive-aggression, or unresponsiveness (Keashly, Reference Keashly2001), could be misconstrued as bullying. Respondents were asked to reflect on instances of events where they observed a situation where others identified the situation as a bullying event that they would describe differently. Of the 313 respondents, 31 identified they had experienced this, and a further four were unsure. Additionally, 138 respondents could identify situations that could have multiple meanings, indicating a broader issue of contested meanings in workplace interactions. Whilst the nature of the sample meant only 10% of respondents identified a ‘disputed event’; this sufficiently enables the researchers to highlight some issues worthy of further analysis. There was little consistency in how the respondents defined the event, if not defining it as bullying.

Delivery of communication

Managers frequently described bullying in terms of verbal behaviours, including both direct aggression and more subtle communication tactics. Some respondents referenced cyber-bullying but provided limited discussion on how it manifests in their workplaces. Future research should investigate the prevalence and impact of cyber-bullying in New Zealand workplaces, particularly in the post-pandemic era. Several respondents identified the delivery of the communication, for example, shouting, sarcasm, tone of voice, humour, as the reason for the disputed act being considered bullying. Respondent 280, a 48-year-old male, mid-level manager stated: ‘One employee did some mistake of what he’s being doing. A foreman yell on him and talk sarcastically direct to the person who did mistakes.’ Similarly, Respondent 41, a 55-year-old female mid-level manager, observed that ‘Long story short, I apparently have tone in my voice and tone is bullying.’ Respondent 23, a 48-year-old male business partner, gave the example of ‘A joke which virtually no one will ever remember 10 min. later.’ Respondent 251, a 63-year-old female senior manager stated, ‘The person was speaking too loudly, and the other person got offended.’ The tone of correction was also identified as an issue for why an event might have been construed as bullying, with respondents suggesting that being advised of mistakes at work was wrongly construed as bullying. There was common agreement that corrective behaviours or comments that were critical of colleagues or employees’ work might be construed as bullying. Respondent 290, a female, mid-level manager gave an example of feedback being misinterpreted as bullying. She said, ‘They couldn’t differentiate between receiving constructive feedback and bullying. Some new kid was using the forklift and weren’t using it right and mocking people when we were trying to assist him when he needed help.’ Respondent 183, 60-year-old male mid-level corrections officer also discussed how feedback is seen as bullying. He said, ‘Generally when someone is brought to task on their mistakes, and they think they are being bullied when a senior officer holds them accountable.’ Respondent 221, a 57-year-old female mid-level manager, gave another example of when staff perceive correcting mistakes as bullying, ‘Being told by another worker what to do for their job.’ Respondent 130, a 62-year-old female upper-level manager recounted the following case in which she was accused of bullying for suggesting improvements, ‘I have been described as a bully when I make suggestions on improving a court reporter’s skills to the team leader who I thought would be the appropriate person to make the suggestion to, but she calls it bullying.’

Unclear definitions of bullying

A key finding was the lack of consensus on what constitutes workplace bullying. Many managers conflated bullying with other forms of workplace conflict, such as performance management, assertive leadership, and interpersonal disagreements. Notably, a subset of responses aligned with WorkSafe New Zealand’s definition, while others reflected broader interpretations, including any form of strong communication or perceived incivility.

A common theme that emerged was how participants perceived different opinions, and even imagined slights other co-workers might often construe as bullying. For example, Respondent 304, a 30-year-old female mid-level manager stated, ‘Everyone has differing opinions and levels that they consider bullying or harassment.’ Respondent 47, a 44-year-old female mid-level manager in education, reflected on an example from outside the workplace in how she sees people defining ‘bullying’. She said:

I often see parents complaining on Facebook about their child being bullied and often I think of it as normal childhood friendship/relationships, part of growing up - such as a child being called a name, and parents now overreact and think of it as bullying.

Adding to the notion of imagined slights, Respondent 299, a 55-year-old female upper-level manager in health care, suggested that in her workplace, ‘One co-worker is always imagining other people are doing and saying things against her.’ When asked to define bullying, the respondents identified more than 100 different behaviours. Some of these examples include Respondent 4, a 28-year-old male, lower-level manager who suggested the following might be considered bullying: ‘Siding with some employees against you.’ Respondent 11, a 70-year-old male upper-level manager, gave the example of:

Being asked to work on my days off and when I say I have made other arrangements to go somewhere on that day, a staff member says a comment like ‘Such as?’ in front of management. I controlled my anger and ignored their remark, but it still rankles me to think about it.

Respondent 127, a 38-year-old female mid-level manager, simply defined bullying as: ‘excessive monitoring’.

Four key notions of ‘bullying’ appeared. Belittling was the most identified, followed by physical abuse and verbal abuse, intimidation, and then ‘criticism’. As criticisms are so open to interpretation, this may present challenges for managers exercising legitimate managerial control.

Non-constructive communication

Two respondents suggested the claim of bullying could have been used to deflect attention from themselves. Respondent 220, a 58-year-old male, upper-level manager noted: ‘The person who claimed to have been bullied were a bully themselves who were seeking to push a personal grievance settlement.’

Humour was also sometimes identified as a non-constructive and bullying form of communication. Respondent 39, a 34-year-old, male, lower-level manager, said people’s use of humour is often used to hide bullying. He said people often use inappropriate or ‘mocking words’ when they bully others and think it is funny.

Finally, respondents were asked to identify how disputed acts of bullying might be perceived differently, regardless of whether they had personally witnessed or experienced an act that was identified at the time as bullying. Whilst 175 of the 313 respondents could not identify potential disputed acts of bullying, the remaining 138 respondents could identify situations that could have multiple meanings. Several key themes emerged from analysing these responses. Some of these are still considered bullying under the New Zealand definition. For example, eight respondents identified abuse, three assault, two racism, threatening behaviour and verbal abuse; and five each for intimidation and harassment. The alternative explanations that do not reflect current definitions of bullying include rudeness, bluntness, loudness, joking, teasing and ‘smartarse’ behaviour.

Discussion

The research findings underscore critical areas essential for understanding bullying within the New Zealand context, which have theoretical and practical implications. Notably, managers who had been accused of bullying often had different views on the meanings of bullying compared to those who had not been accused. This highlights the subjective nature of bullying perceptions and the influence of personal experiences. Managers’ definitions of bullying often diverge from the legal definition and other definitions in the literature. For example, while the law defines bullying as repeated and unreasonable behaviour, managers may perceive it as any negative interaction, regardless of frequency or reasonableness. Although the study included a large sample, some themes were only supported by a small number of participants. For instance, only four managers explicitly discussed retaliation or organizational tolerance of bullying. These inconsistencies highlight the need for further research into managerial perceptions and the contextual factors shaping them. These themes are important however as they highlighted avenues that need further explicit exploration by researchers as our understanding of communication and bullying advances.

Theoretical implications

Theoretically, findings challenge the conventional view of bullying as intentional, proposing a nuanced understanding of intent and interpretation. Intent and interpretation are crucial when discussing bullying. If bullying is seen as an intentional action, it cannot be considered noise. However, if a message is interpreted differently than intended, as often seen in these research responses, it can be understood as noise. Noise can be both physiological and psychological, it is the interpretation that differs. West and Turner (Reference West and Turner2022) focused on the issues of sender and receiver and noise, and the research suggests perhaps we should look to recode some acts of bullying as noise? The exploration of noise in communication, influenced by cultural diversity and individual communication styles, supports recoding some acts of bullying as noise. It needs to be acknowledged by managers and workers alike that how information is communicated is critical. New Zealand workplaces are diverse, in terms of gender, age, and ethnicity amongst other factors. The research suggests workers may not necessarily come to the workplace with the skills to either moderate their own communication style or to interpret messages without noise in the form of their own opinions and experiences regarding tone. Keashly and Neuman (Reference Keashly and Neuman2004) argue that minor changes in daily interactions can lead to substantial transformation.

This study highlights that allegations of bullying can sometimes be a means of expressing dissent. Additionally, instances of bullying may arise from the inability to communicate dissent in healthy and appropriate ways. Bullying is connected to larger systems of meaning, including organizational culture, power dynamics, and societal norms. Understanding these connections is crucial for developing effective interventions. Both bullying and dissent are forms of communication that involve expressing disagreement and challenging norms (Tootell et al., Reference Tootell, Croucher, Cullinane, Kelly and Ashwell2023). It is therefore not surprising that where dissent is unable to be easily or healthily expressed, more destructive forms of change communication, such as bullying, may become more prevalent. Tootell et al., (Reference Tootell, Croucher, Cullinane, Kelly and Ashwell2023) found that New Zealand workers who engaged in more articulated and latent dissent were more likely to perceive workplace bullying. The results of the current study add a further dimension to our understanding of the link between workplace bullying and dissent in the New Zealand workplace, by examining how managers perceive this relationship. Future research should continue to explore the link in other cultural contexts.

Practical implications

Practically, if managers and organizations can acknowledge the complexities in this space, then there is a myriad of relatively simple and low-cost interventions that can be put in place to work to reduce disharmony, and feelings of bullying and inappropriate interactions in the workplace. For example, an act as simple as a course on cross-cultural communication could inform a worker how messages are differently influenced by the cultural norms and backgrounds that workers bring with them to the workplace. A critical takeaway from this study is that managers may require additional training to distinguish between legitimate workplace conflicts and bullying. Infante’s framework suggests that verbal aggression is often misinterpreted when context and intent are not considered. Cross-cultural training and education on WorkSafe’s definitions could help managers make more informed decisions.

Communication research suggests that some people are innately more verbally aggressive (Beatty & McCroskey, Reference Beatty and McCroskey1997; Camara & Orbe, Reference Camara and Orbe2010), perceiving verbal aggression as more justified (Martin, Anderson, & Horvath, Reference Martin, Anderson and Horvath1996) and less damaging to targets than people with low verbal aggressiveness do (Hample & Anagondahalli, Reference Hample and Anagondahalli2015; Infante, Riddle, Horvath, & Tumlin, Reference Infante, Riddle, Horvath and Tumlin1992). This helps explain why perpetrators appear to lack empathy (Crawshaw, Reference Crawshaw2005). Rancer and Avtgis (Reference Rancer and Avtgis2006) suggest that if people are verbally aggressive because they lack the skill to develop or generate effective arguments, training can serve as an ameliorative, enhancing skills and curbing verbal aggressiveness. Thus, acceptable standards of behaviour could be set by, and communicated in, a code of conduct, providing tangible boundaries and ‘rules of engagement’ for staff on an ongoing basis.

Another critical issue raised from this study is that respondents did not have the same clarity of what bullying was, compared to what organizations may have in their policies. Setting acceptable standards of behaviour through a code of conduct can establish clear boundaries and rules of engagement. The study advocates for clear definitions of bullying, harassment, and incivility, enabling organizations to manage these disruptive behaviours appropriately. For example, findings indicate that issues of tone could easily be considered verbal aggression, and it is only through further clarity that these can be resolved. Thus, the importance of organizational policies and procedures are highlighted, emphasizing the need for clear definitions and pathways for interventions. Findings support promoting a better understanding of what constitutes bullying and what does not, fostering positive workplace interactions, and preventing retaliatory behaviours. Academia has a responsibility, alongside organizations and managers, to clearly express and define for their workers what bullying is and is not. Workplace bullying, harassment, and general incivility can all manifest similarly (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang, Peng, Geimer, Sharp and Jex2019; Johnson, Reference Johnson2015). Although all these behaviours are undesirable workplace behaviours, managers recognize that they need to be managed differently. It’s important to understand the differences between workplace bullying, incivility, and harassment, all of which fall under the category of disruptive behaviours, and how to manage each. This is not to ignore issues that are identified that do not meet the current WorkSafe New Zealand (2017) definition of bullying, but rather to allow for more appropriate interventions. Again, communication skills are likely to be key in improving these interactions. Where behaviours are identified as unprofessional, or merely non-productive, providing workers and managers with the tools to better express themselves, with less opportunity for noise on the part of the decoder, should lead to more positive workplace interactions. Prior research suggests that simply understanding workplace bullying helps leaders and members adopt new attitudes, respond more quickly to reported abuse, and counter bullying in constructive ways (Lutgen-Sandvik, Namie, & Namie, Reference Lutgen-Sandvik, Namie, Namie, Lutgen-Sandvik and Sypher2009).

Further, organizations need to have robust systems in place for reporting and addressing bullying with clear definitions, and clear pathways of interventions. This may help address the unreported and unrecognized acts of bullying identified in the research; alongside also identifying other unproductive workplace behaviours and finally, recognizing the retaliatory behaviour where the accusations of bullying are utilized to stifle reasonable workplace disagreement and legitimate managerial prerogative. Organizational policies and procedures are also complicit in why bullying is poorly understood. Ambiguous policy wording can silence abused workers (Meares, Oetzel, Torres, Derkacs, & Ginossar, Reference Meares, Oetzel, Torres, Derkacs and Ginossar2004) and make it nearly impossible for human resource management to respond effectively (Cowan, Reference Cowan2009), or alternatively when the activity does not meet the threshold for bullying, still leave the unproductive or unprofessional behaviours unaddressed and unresolved.

Figure 1. Communication-centered model of how individuals interpret potential acts of workplace bullying.

Finally, any non-productive communication behaviours, such as unprofessional or inconsiderate interactions, could be misconstrued as bullying. This issue is heightened, as explained earlier, by cultural diversity and individual communication styles. Our study emphasizes the significance of communication skills in diverse workplaces. Acknowledging the diverse backgrounds and communication styles of workers, managers, and organizations, findings suggest that simple, low-cost interventions, such as cross-cultural communication courses, can mitigate misunderstandings, including those, for example, mistakenly perceived as verbal aggression.

Limitations and conclusion

There are three limitations to this study. First, the research provides only a snapshot rather than extensive insight and therefore cannot be generalized. Regarding transferability, the self-selected nature of respondents and the specific context in which the survey was conducted may limit the extent to which findings can be generalized to other populations or settings. However, detailed descriptions of the context and participant responses allow readers to assess applicability to their own environments. Second, as a retrospective study, participants were required to recall their experiences managing bullying, which may lead to inaccurate accounts. Finally, this study’s reliance on anonymous, text-only online responses introduces certain limitations. The absence of interactive dialogue restricts the ability to explore or clarify responses in depth, potentially leading to less nuanced data. This can affect the credibility of the findings, as the depth and context typically gained through interviews or focus groups are absent. To mitigate this, rigorous thematic analysis procedures were applied, including independent dual coding and consensus discussions, enhancing the trustworthiness of the interpretations. Additionally, without demographic or contextual follow-up, some interpretative detail may be lost. However, the anonymity likely promoted honest disclosure of sensitive topics like bullying, and the textual data still captured authentic, participant-driven perspectives. These strengths support the validity and value of the findings despite the inherent constraints of the data collection method.

Overall, while the data collection method imposes certain constraints, these limitations are balanced by methodological rigor and the richness of firsthand textual accounts, supporting the study’s contribution to understanding workplace bullying perceptions, allowing for the ‘voice of participants’ to be heard, which is a strength of this study. Future studies could employ interviews or focus groups to explore managerial perceptions in greater detail. In terms of dependability, the consistent application of Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2022) thematic analysis framework and Tracy’s (Reference Tracy2019) qualitative rigor guidelines supports the stability of the analytic process. Maintaining an audit trail of coding decisions and iterative theme refinement further strengthens the reliability of the findings. Finally, confirmability was addressed by using multiple coders to reduce subjective bias and by negotiating disagreements to reach a consensus. While the anonymous, text-only nature of the data prevents follow-up validation with participants (member checking), transparency in coding and theme development promotes objectivity and accountability in the analysis.

The New Zealand context is peculiar and not necessarily transferable, but an understanding of the organizational communication culture is instructive, and it may be worth considering if on this basis quantitative tools can be transferred across cultures without retesting – NAQ-R results. Whilst organizations have very clearly recognized the need to have systems in place to recognize and address bullying, the research undertaken with 316 New Zealand workers suggests much work is still to be done on clearly understanding what bullying is and isn’t. Behaviours that are unproductive or unprofessional still require management intervention, those interventions may be differently chosen and applied than if they are characterized as bullying. Further, the stigma attached with either reporting a colleague as a bully, or indeed being personally identified as a bully, may stop individuals from seeking skills and training because of communication challenges. Individuals may be more willing to engage with behaviour modification when those behaviours are more neutrally represented. Finally, the reverse is also true, some workers still identify serious acts, which are easily identifiable as bullying regardless of the definitional schema utilized, such as verbal aggression, as ‘not bullying’. Gaining clarity around precisely what constitutes workplace bullying would also deliver greater prominence, greater reporting, and therefore managerial action, when addressing such bullying incidences.

If we wish to address inappropriate workplace behaviours in a practical and meaningful way, we need to have the best possible insight into both its antecedents and its outcomes. If we restrict the measurement of bullying to perceived and self-reported prevalence without understanding the communication context, we risk characterizing the behaviour solely as individual aberrant behaviour. The communication context includes the broader organizational environment, cultural norms, and interpersonal dynamics that influence how bullying is perceived and enacted. At the level at which bullying is currently reported in New Zealand, behaviour outside the area is in fact normalized, so it may be time to consider other explanations (Cullinane, Croucher, Tootell, & Ashwell, Reference Cullinane, Croucher, Tootell and Ashwell2019).

This research is firmly rooted in a constructivist paradigm, whereby the key process of data collection is narrative rather than deterministic. The purpose of this research is to create meaning-based models and understandings of bullying in the workplace context. Further, this research takes a social epistemological approach and acknowledges that knowledge is contextual and time bound.

This study highlights the complexity of workplace bullying perceptions among managers in New Zealand. Findings suggest a need for clearer definitions, enhanced training, and a broader discussion on cyber-bullying. Future research should expand on these areas, incorporating diverse methodologies to capture the full scope of managerial perspectives.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.