Introduction

Workplace gossip, a pervasive and complex element of organizational life, significantly shapes workplace dynamics. Rooted in social interaction, gossip serves multiple psychological and organizational functions, including information exchange, social bonding, and norm enforcement (Foster, Reference Foster2004; Lyu, Wu & Yurong Fan, Reference Lyu, Wu and Yurong Fan2024). In psychology, it is seen as a key mechanism for regulating social behavior, maintaining group cohesion, and reinforcing shared values (Liao, Wang & Li, Reference Liao, Wang and Li2022). Organizational behavior research also recognizes gossip as a double-edged sword – it can foster trust and belonging while contributing to uncertainty and workplace stress (He, Feng, Xiong & Wei, Reference He, Feng, Xiong and Wei2023; Reference Michelson and Mouly2002).

The positive psychology paradigm highlights the importance of fostering job involvement and retention, making it crucial to understand the factors that influence employees’ intentions to leave. Turnover intention has been linked to a variety of individual, organizational, and environmental factors (Harris & Jones, Reference Harris and Jones2023; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2011). While many turnover predictors have been explored, the role of workplace gossip in shaping employees’ attitudes toward their organizations remains underexplored. This study aims to examine workplace gossip as a key factor influencing turnover intention.

Gossip in the workplace can have both positive and negative effects (Ellwardt, Steglich & Wittek, Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012; Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell & Labianca, Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Wang and Li2022). Its dual nature arises from its complex structure – while gossip can promote relationships and job satisfaction (Hu, Wang, Lan & Wu, Reference Hu, Wang, Lan and Wu2022; Song & Guo, Reference Song and Guo2022), it can also fuel dissatisfaction and increase turnover intention. The varying emotional responses to gossip further explain its diverse impact on employee attitudes and behaviors. While gossip can build relationships and foster positive emotions, its effects diminish when the content is uninteresting or actively avoided by employees (Nguyen & Walker, Reference Nguyen and Walker2020; Smith & Brown, Reference Smith and Brown2022).

Based on the findings from the literature, we first conducted Study 1. Findings from Study 1, which involved interviews with both public- and private-sector employees, provide further empirical support for these perspectives. The qualitative insights reveal that workplace gossip demonstrates differently across sectors, with public-sector employees emphasizing its role in information dissemination, while private-sector employees highlight its impact on psychological safety. These interviews also indicate that employees’ perceptions of gossip depend on contextual factors such as organizational culture and structure participating in gossip networks (Li, Huang, Wang & Wang, Reference Li, Huang, Wang and Wang2023).

Given the various reasons outlined in the theoretical background and Study 1, it is important to establish a connection between workplace gossip and individual or organizational factors by considering the significance conveyed by the dimensions involved. With this insight obtained, Study 2 was conducted. In Study 2, we investigated the impact of workplace gossip on employees’ intention to leave their jobs. We also examined the variables that mediate this relationship. Researchers have demonstrated that negative gossip can deter selfish behavior and promote cooperative and helpful behavior in specific situations (Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Willer and Schultz2014; Kniffin and Sloan Wilson, Reference Kniffin and Sloan Wilson2010). The researchers of this study estimate that gossip, which leads to attitude and behavioral change, promotes positive affect and increases the employee’s affective commitment to the organization. Furthermore, embracing collaborative behavior patterns can effectively combat feelings of loneliness in the workplace. On the other hand, it is important to note that the effects of gossip can also be negative, depending on how it impacts the other party and the nature of the gossip itself. Gossip can disrupt positive emotions and undermine emotional commitment within an organization, thus leading to feelings of loneliness among employees. In both situations, researchers assume that employee attitudes regarding their intentions to leave will change.

This study offers an insightful contribution to literature by delving into the negative and positive dimensions of workplace gossip. While research in existing literature only presents either positive or negative sides of workplace gossip, our study discusses both the positive and negative aspects of the concept simultaneously. For this reason, a qualitative research method was utilized in this study to explore the motivations behind gossip in the workplace. The research focused on the functions of gossip in the workplace and how it is employed for positive or negative purposes. Research has demonstrated that gossip is a prevalent form of communication in the workplace, influencing both interpersonal relationships and organizational processes. However, our understanding of the intentions and consequences of gossip remains limited. This study aims to address this gap by examining how various motivations drive gossip and the role these motivations play in organizational concepts.

We estimate that the second contribution of the study is that these possible relationships may vary in the intention to quit depending on whether the employee is a public- or private-sector employee. Namely, positive gossip enhances an employee’s commitment to the organization by significantly activating positive emotions. Therefore, this positive mood reduces the likelihood of them leaving their job. However, while negative gossip can lead to loneliness and weak emotional commitment, it’s important to consider the impact of being an employee in the public or private sector when it comes to revealing the intention to leave the job. The importance of an employee’s economic well-being and job prospects may outweigh the significance of feeling lonely or emotionally committed to the organization. While being a public employee provides a job guarantee and psychological comfort, the possibility of a private-sector employee finding another job opportunity with similar conditions is an important factor that may affect the decision to leave the job. Therefore, in order for the research model to produce generalizable results, the sample limitations must be assessed under such conditions. This study, which considers public- and private-sector dynamics, points out another contribution of the study to the field. In addition, considering the effects of culture and sectors on employee behavior and attitudes (Cheng, Duan, Wu & Lu, Reference Cheng, Duan, Wu and Lu2023; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), the study was conducted on Turkish citizens working in the service sector in Turkey.

Researchers stress the importance of using diverse strategies, methods, and techniques in social science research, highlighting that gathering data from multiple sources enhances the generalizability of results. In examining workplace gossip as a precursor to the intention to leave, combining qualitative and quantitative data collection methods contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of communication literature theory and practice.

Study 1

Gossip: ‘third-party information’

Gossip is a conversation that revolves around daily life (Giardini & Conte, Reference Giardini and Conte2011). It can be referred to as ‘idle talk’ or ‘chitchat’ as it involves discussing social and personal issues (Foster, Reference Foster2004). In the workplace, informal and spontaneous communication is also considered to occur through personal interactions rather than official channels (Allen, Reference Allen1995). In this perspective, organizational gossip involves individuals discussing and evaluating third parties or events within and outside the workplace with colleagues they feel close to (Michelson, Van Iterson & Waddington, Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010).

As defined by Michelson and colleagues (Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010), the literature addresses organizational gossip in two ways: work-related and nonwork-related gossip (Beersma, Van Kleef & Dijkstra, Reference Beersma, Van Kleef, Dijkstra, Giardini and Wittek2019; Mills, Reference Mills2010; Noon & Delbridge, Reference Noon and Delbridge1993). Work-related gossip among all employees, both horizontally and vertically, can involve (un)constructive criticism and insights about performance, workplace relationships, ethical considerations, employee rights, and organizational policies and procedures (Noon & Delbridge, Reference Noon and Delbridge1993). Here, employees compare their outputs, such as wages and promotions, to evaluate their value based on upward or downward assessment (Kramer, Reference Kramer1999; Mills, Reference Mills2010). Gossip at the vertical level typically involves discussions about the organization’s operation and management-related matters (Mills, Reference Mills2010). This is a form of communication in which managers assess their employees or employees offer critiques of the management. Additionally, gossip unrelated to work involves sharing news about the personal lives of others within the organization (Chang, Reference Chang and Chang2023). In terms of strengthening informal employee relations, gossip, particularly on a horizontal level, can be viewed as a mediating factor (Estévez, Wittek, Giardini, Ellwardt & Krause, Reference Estévez, Wittek, Giardini, Ellwardt and Krause2022). In addition, the literature discusses gossip in organizations as having positive and negative aspects. Positive workplace gossip involves sharing favorable information about an absent individual and a positive personal assessment among people in appropriate contexts (Foster, Reference Foster2004). Conversely, negative organizational gossip refers to informal communication that aims to harm individuals or the organization. Examples include damaging a coworker’s reputation, undermining management, or creating conflict within teams for self-serving or malicious reasons (Kurland & Pelled, Reference Kurland and Pelled2000).

Gossip motives: public versus private sector

The primary difference between the public and private sectors lies in the ownership of the business (Johnson, Reference Johnson2020). In the public sector, ownership is generally held by a government entity, whereas in the private sector, ownership is maintained by nongovernmental individuals or institutions (Mirze, Reference Mirze2006). The rights and working conditions of employees naturally vary depending on the type of ownership (Needle & Burns, Reference Needle and Burns2010).

In these sectors, the choice between the public and private sectors depends on social value, individual characteristics, economic conditions, and institutionalization within the organization (Bhui, Dinos, Galant-Miecznikowska, de Jongh & Stansfeld, Reference Bhui, Dinos, Galant-Miecznikowska, de Jongh and Stansfeld2016). Working as a civil servant is often seen as an appealing opportunity in societies that prioritize job security (Willem, De Vos & Buelens, Reference Willem, De Vos and Buelens2010). In some countries such as Turkey, Germany, and Korea, public-sector employees enjoy legal protection for job security and may benefit from lifetime tenure (see OECD, 2023).

In the public sector, the high job security perceived by civil servants is a product of the structured bureaucratic system. This system ensures that all processes, from hiring to dismissal, are conducted in accordance with established rules, promoting a sense of fairness and stability. The primary objective of all employees is to serve society, rather than focusing on profitability (Buelens & Van den Broeck, Reference Buelens and Van den Broeck2007). In the private sector, businesses strive for a balance between profitability and productivity. The employee’s contribution to this goal is a key factor in performance measurement, and behaviors such as quitting or being fired may affect this. Consequently, public employees consider job security a significant advantage and a key factor in their decision to remain in the public sector (Aguiar Do Monte, Reference Aguiar Do Monte2017). However, in the private sector, job security can be improved by enhancing individuals’ skills through education and experience, and by transitioning to companies with strong financial resources (Munnell & Fraenkel, Reference Munnell and Fraenkel2013).

When this situation is evaluated specifically in terms of workplace gossip, the difference in the sector leads to variations in employees’ approaches to gossip and, more importantly, in their work attitudes and behaviors. As mentioned above, the prioritization of efficiency and competition in the private sector leads to employees who engage in gossip being punished more swiftly, facing management decisions regarding their performance, or even being dismissed. This situation can create a basis for employees to behave more cautiously/strategically in participating in informal information flow within the organization, including information sharing. In the public sector, however, due to job security, gossip can lead to long-term attitudes and behaviors among employees. At this point, employees, especially in bureaucratic environments where official communication channels are slow, may approach gossip more tolerantly as an informal communication tool. It is considered important to determine the impact of this concern on employees’ job attitudes, particularly their emotional commitment to the organization and their intention to leave. For this purpose, it is believed that adding these variables to the quantitative research, which constitutes the second part of the article, will allow for a detailed examination and understanding of this difference.

Method

Research settings and samples

Cultural and sector-specific factors significantly influence employee behavior (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Duan, Wu and Lu2023). Turkey’s high-context communication culture and collectivist values play a key role in shaping how employees interact, particularly in informal communication contexts like gossip (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). These cultural traits foster stronger social bonds and in-group solidarity, allowing gossip to have a more substantial impact on organizational dynamics. Additionally, the hierarchical structure typical of Turkish workplaces, along with strong familial ties, influences how relationships are formed and maintained in the workplace (Kuo, Wu & Lin, Reference Kuo, Wu and Lin2018).

The service sector is distinct from other sectors due to its unique operational demands, including customer-facing roles and a high degree of interpersonal interaction. Employees in the service sector are often required to manage emotions and maintain positive interpersonal relationships with customers and colleagues, which can lead to specific challenges in terms of stress management, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Duan, Wu and Lu2023). Unlike manufacturing or technical sectors, service sector employees are continuously engaged in maintaining relationships, which influences their job satisfaction and emotional commitment to the organization (Bencsik & Juhasz, Reference Bencsik and Juhasz2020). These sector-specific dynamics contribute to distinct employee behaviors, and attitudes. As a result, managing the interpersonal and emotional aspects of work in the service sector requires specific strategies to enhance employee well-being and reduce turnover, making it a critical area for organizational research (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010; Michelson et al., Reference Michelson, Lentz, Mulwa, Morey, Cramer, McGlinchy and Barrett2012). Therefore, to control for potential cultural and sectoral influences, the study was conducted with Turkish citizens working in both public and private service sector organizations in Turkey.

Using qualitative research under the interpretive paradigm, the study aims to investigate the process of gossiping in organizations in depth. A series of semi-structured interviews were used to gather information for the current study. The data collected from the participants were further analyzed using the content analysis approach, a meticulous, methodical, and thorough review and interpretation of a specific body of material to find themes, patterns, assumptions, and meanings (Berg & Latin, Reference Berg and Latin2008). A standard set of analytic activities arranged in a general sequence order: (a) Information is gathered and formatted to be ‘read’, such as by turning it into text. (b) Codes are attached to sets of notes or transcript pages after being produced analytically and/or inductively detected in the data. (c) Codes are converted into themes or categorized labels. (d) The materials were arranged according to these categories, revealing related terms, trends, connections, and similarities or differences. (e) Examining sorted materials allowed one to identify significant patterns and processes.

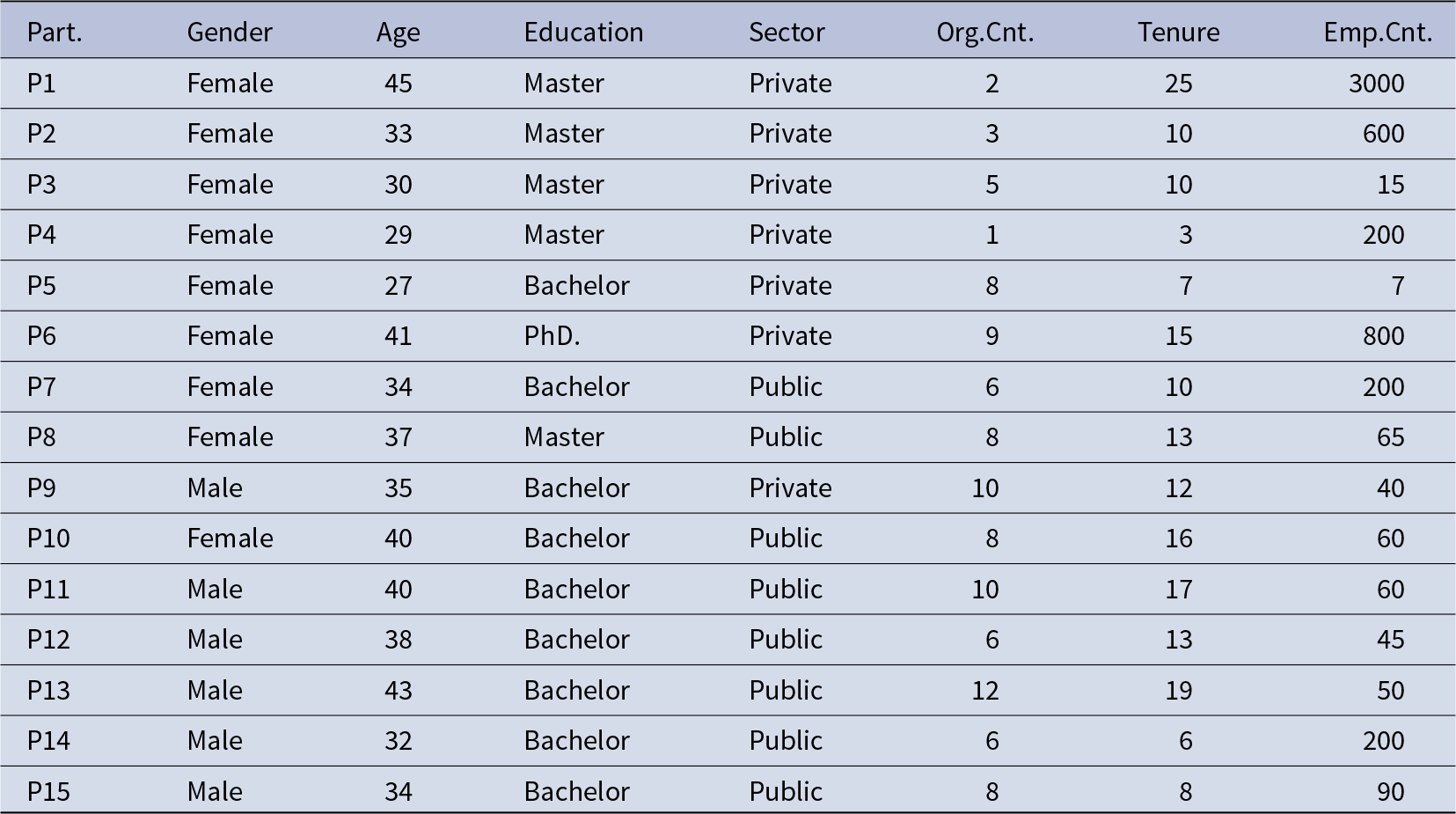

The purposive sample approach was used to select study participants. Five open-ended questions were utilized in semi-structured face-to-face and online interviews to gather qualitative information about participants’ opinions of organizational gossip and the motivations behind it. These questions can be found under the appendix section. As per the aim of this study, a varied sample of employed individuals from several demographic categories – including age, gender, sector, and professions required. In addition, the study participants had to deal with gossip in their daily jobs. As a result, 15 workers were chosen to be the study’s primary participants. Every member works full-time, at least 40 hours a week; the public and private sectors employ 8 and 7 people, respectively. Their demographics matched those of the projected sample, allowing us to obtain a snapshot of representative workplaces (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographics of participants

Note: Part.: Partner, Org.Cnt.: Experience in the Organization, Emp.Num.:Number of Employees

Findings

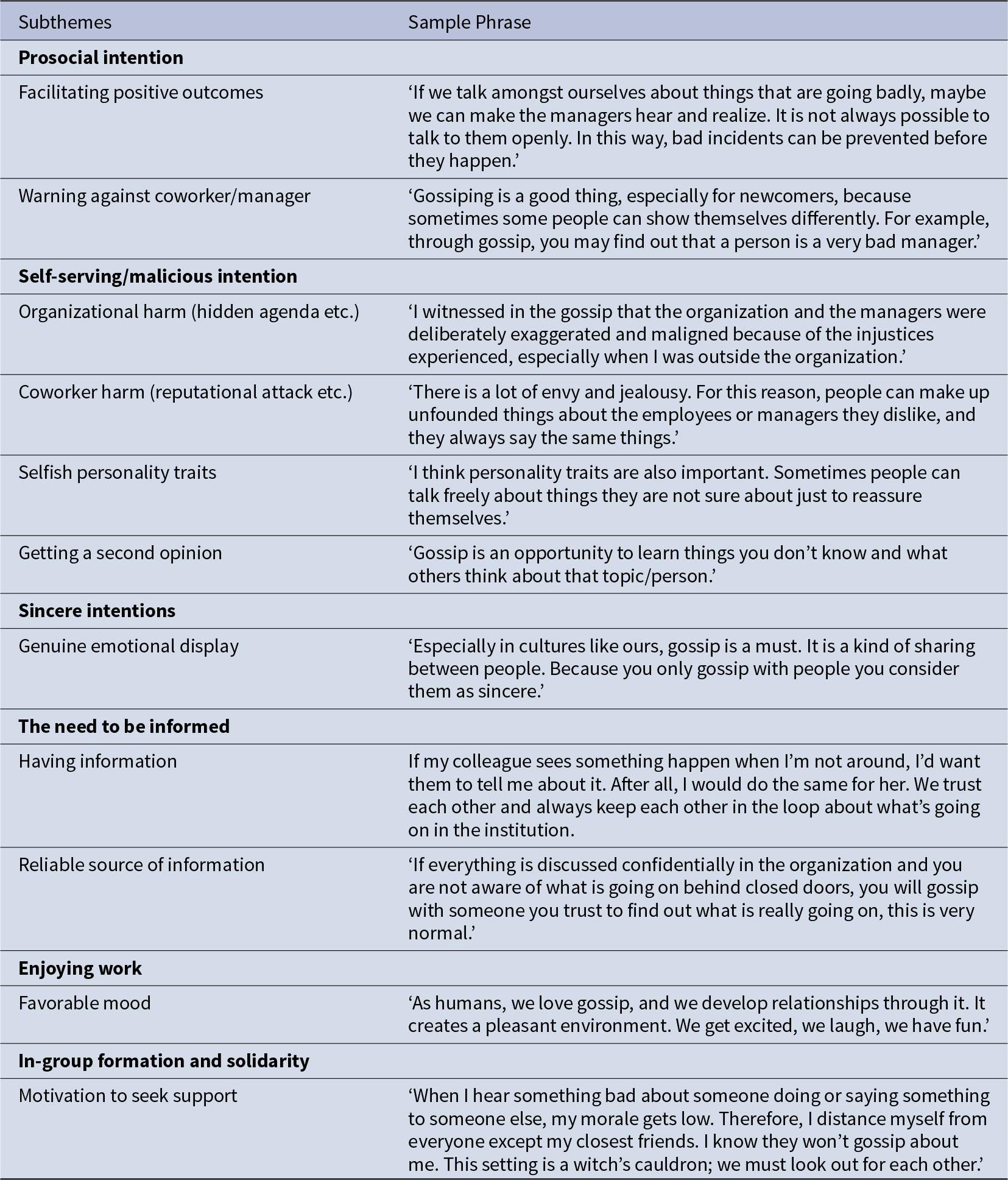

In line with the research questions, the answers given by the participants were divided into two groups. In the first group, themes and subthemes were obtained from the participant’s answers to the motives for gossiping in organizations. We captured six main themes: Prosocial Intentions, Self-serving/malicious Intentions, Sincere/intimate Intentions, The Need to be Informed, Enjoying Work, and In-group Formation and Solidarity. In the second group, themes and subthemes are obtained from the participants’ responses regarding the possible consequences of organizational gossip (Table 2). Under the consequences of organizational gossip, we explain three main themes, namely ‘Individual work attitudes, behaviors, and emotions’; ‘Dyadic interactions’; and ‘Organizational effectiveness’. Subthemes and expression patterns belonging to the themes in the two groups are explained under the following headings.

Table 2. Motives of organizational gossip

Motives of organizational gossip

Participants’ perceptions of the underlying intentions were collected under 6 themes and 11 subthemes. While some participants viewed gossip as a challenge to improving communication schemes in the workplace, others perceived gossip as a tool to facilitate the management of workplace relationships and to be informed (see the details in Table 2);

… If we talk amongst ourselves about things that are going badly, maybe we can make the managers hear and realize. It is not always possible to talk to them openly. In this way, bad incidents can be prevented before they happen … (P1, Facilitating Positive Outcomes)

… Gossiping is good, especially for newcomers, because sometimes some people can show themselves differently. For example, through gossip, you may discover that a person is a terrible manager. (P5, Warning against coworker/manager)

Here, P1 and P5 state that gossiping at work can be a tool to improve interpersonal relationships and thus prevent negative events from occurring in the organization. Moreover, P1 believes that if managers become aware of the negative events that employees talk about among themselves, some positive developments will occur.

If everything is discussed confidentially in the organization and you are not aware of what is going on behind closed doors, you will gossip with someone you trust to find out what is going on; this is very normal. (P3, Reliable source of information)

As P3 stated, if the organization’s communication structure creates obstacles to informing employees, it seems normal for people to learn about workplace developments from gossiping. However, unlike some participants, P2 and P4 stated that gossiping carries the intention of harming the reputation of employees or the organization rather than gaining information or improving relations in the organization.

… I witnessed in the gossip that the organization and the managers were deliberately exaggerated and maligned because of the injustices experienced, especially when I was outside the organization … (P2, Organizational Harm/Hidden Agenda)

… There is a lot of envy and jealousy. For this reason, people can make up unfounded things about the employees or managers they dislike, and they always say the same things. (P4, Coworker Harm/Reputational Attack)

When we look at the participants’ statements focusing on the positive aspects of gossip, P10 emphasizes that the basis of gossip in the organization is the trust relationship established between colleagues. P10 also believes that employees can only get accurate information from colleagues whom they trust.

… If my colleague sees something happen when I’m not around, I’d want them to tell me about it. After all, I would do the same for her. We trust each other and always keep in the loop about what’s happening in the institution … (P10, Having Information)

Emphasizing that gossip can also be used to improve interpersonal relations, P11 stated that gossip adds energy to the workplace atmosphere and even has a motivating and uplifting aspect. On the other hand, P13 stated that gossip reinforces the strengthening of in-group relations and may cause people in the formed group to trust each other.

… As humans, we love gossip, and we develop relationships through it. It creates a pleasant environment. We get excited, we laugh, we have fun. (P11, Favorable Mood)

… When I hear something bad about someone doing or saying something to someone else, my morale gets low. Therefore, I distance myself from everyone except my closest friends. I know they won’t gossip about me. This setting is a witch’s cauldron; we must look out for each other. (P8, Motivation to seek support)

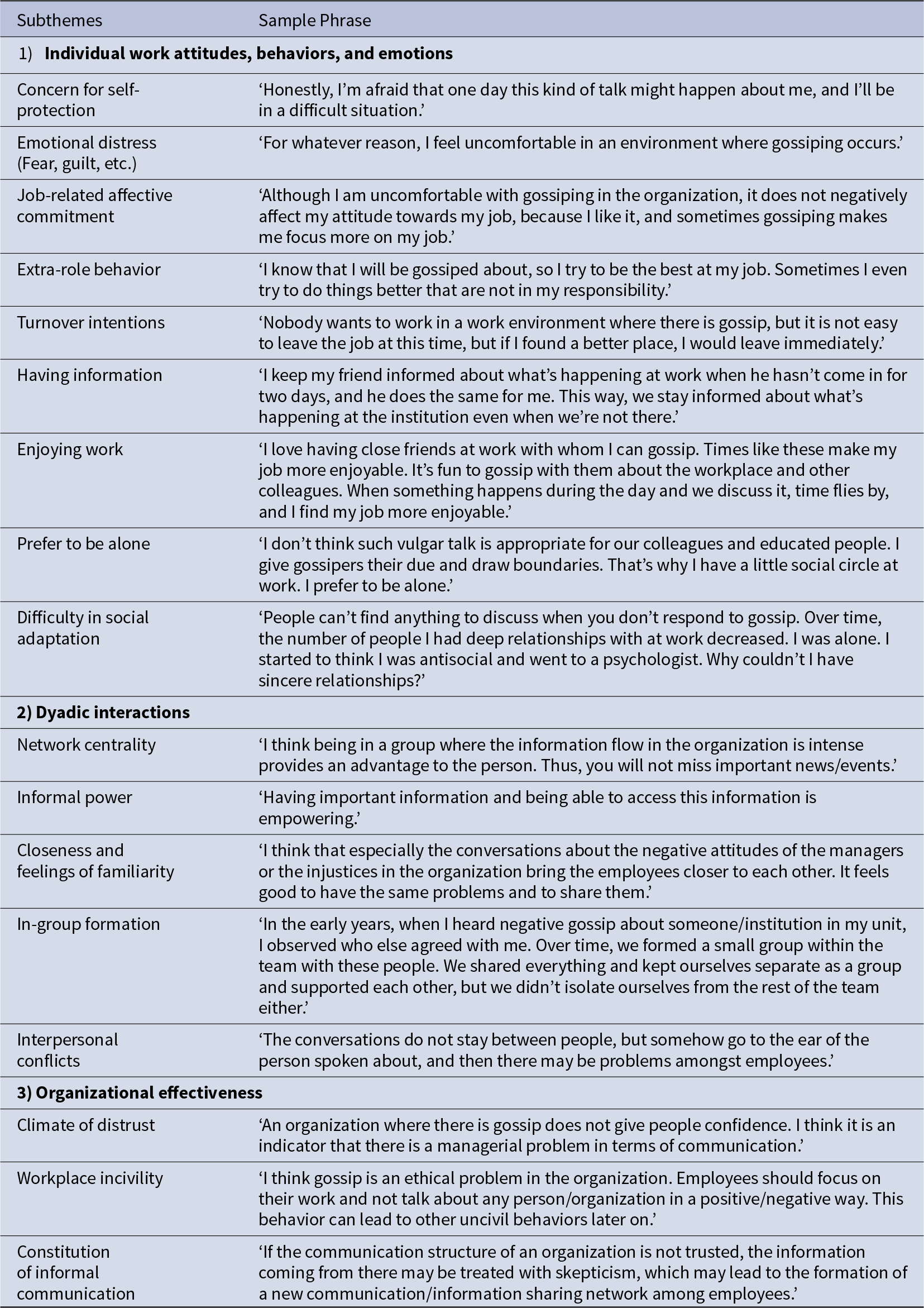

Consequences of organizational gossip

Participants’ perceptions of the consequences of gossip were collected under 3 themes and 18 subthemes. Some participants see gossip as a challenge to maintain positive attitudes and behaviors in the workplace, while others perceive it as a facilitator to manage dyadic interactions in the organizations (see the details in Table 3);

… For whatever reason, I feel uncomfortable in an environment where gossiping occurs. I am also afraid that if the people being talked about one day find out about it, my relations with them will deteriorate. (P2, Emotional distress)

Table 3. Consequences of organizational gossip

… Honestly, I’m afraid that one day this kind of talk might happen about me, and I’ll be in a difficult situation… (P4, Concern for self-protection)

… Nobody wants to work in a work environment where there is gossip, but it is not easy to leave the job at this time, but if I found a better place, I would leave immediately. (P1, Turnover intentions)

Here, P2 and P4 underlined that gossiping in the work environment may have negative effects on people’s emotional well-being. They stated that they were worried that their relationships with other people in the organization would deteriorate if it was discovered that they were gossiping. Moreover, P1 stated that one might feel uneasy about working in a place with gossip. It stated that working in a different institution would be better when the opportunity arises.

Looking at the statements of P10 and P11, it is seen that they focus on the possible positive consequences of gossip. While P11 stated that establishing close friendships with which he/she can gossip in the work environment positively affects his/her feelings about his job, P10 similarly stated that being aware of what is going on within the organization reinforces his/her feelings of ownership towards the organization.

… I love having close friends at work with whom I can gossip. Times like these make my job more enjoyable. It’s fun to gossip with them about the workplace and other colleagues. When something happens during the day, and we discuss it, time flies by, and I find my job more enjoyable … (P10, Enjoying work)

… I don’t think gossip is a bad thing at all. I’ve been in this workplace for six years. Of course, I have to know what’s going on. If I don’t know what’s happening, I’ll be the outside latch on the outside door (“distant relations with target” in the local language). I’ll only have a give-and-take relationship with the institution. Knowing what’s happening in the institution makes me feel like there is mine … (P11, Feelings of possession)

As P1 stated, gossip can be a way to gain power and authority over other people within the organization, in proportion to the importance and power of the information obtained. In addition, P2 stated that being in the middle of the information network in the organization can provide some advantages to the employees in bilateral relations. At this point, P1 and P2 emphasized that gossiping can provide privilege for employees and that information can provide a strategic advantage in bilateral relations. P3, on the other hand, stated that if the person who is the subject of the gossip realizes the gossiping, bilateral relations may deteriorate, and some conflicts may occur.

… Having important information and being able to access this information is empowering … (P1, Informal Power)

… I think being in a group where the information flow in the organization is intense provides an advantage to the person. Thus, you will not miss important news/events … (P2, Network centrality)

… The conversations do not stay between people, but somehow go to the ear of the person spoken about, and then there may be problems amongst employees … (P3, Interpersonal conflicts)

In their speeches, P4 and P5 emphasized that gossip can negatively affect the productivity of organizations. They underlined that in organizations where gossip is frequently used, employees cannot develop a sense of trust towards their organizations, and such uncivil behaviors may increase. This situation can be seen as a managerial deficiency. P2, on the other hand, stated that gossip can also be an important means of information and can create a new communication channel, especially in organizations with a weak communication structure, and can create a basis for employees to work more effectively.

… An organization where there is gossip does not give people confidence. I think it is an indicator that there is a managerial problem in terms of communication … (P4, Climate of distrust)

… I think gossip is an ethical problem in the organization. Employees should focus on their work and not talk about any person/organization in a positive/negative way. This behavior can lead to other uncivil behaviors later on … (P5, Workplace incivility)

… If the communication structure of an organization is not trusted, the information coming from there may be treated with skepticism, which may lead to the formation of a new communication/information sharing network among employees … (P2, Constitution of Informal Communication)

Discussion for study 1

This study investigated how individual, group, and organizational dynamics interact with gossip in the work management process of Turkish employees. Using a sample of white-collar employees employed in the private and public sectors, we specifically examined how employees perceive blurred work-life due to the role of the growing use of gossip at workplaces and how individual and organizational dynamics have reconfigured work-life relations through the entanglement with gossip.

The analysis results revealed that the participants’ perceptions of work-life relations regarding organizational gossip vary significantly. Similar to past research findings (Sun, Schilpzand & Liu, Reference Sun, Schilpzand and Liu2023), the study participants also differed in their perception of gossip in workplace relationships. The participant data indicated that the reasons for these differing perceptions could be attributed to various individual, group, and organizational factors that foster gossip and the underlying dynamics specific to the employed sector (private/public). A detailed examination of the participants’ responses shows that individuals’ desire to establish social connections within the organization is one of the main motivations behind gossip. Indeed, Beersma and Kleef (Reference Beersma and Kleef2012) mentioned that gossip fosters a sense of closeness and trust among employees, stating that this situation can strengthen interpersonal relationships. Researchers note that environments where employees share personal information or experiences enhance these close relationships, reinforcing group cohesion and solidarity.

Observing another topic participants emphasized, we find that employees’ motivations to verify information about organizational happenings significantly influence their gossiping behavior. In addition to social ties, the participants consider gossip important in spreading information within the organization and serving as a tool for verifying the information held. According to the literature, gossip provides a simple method for gathering information about individuals or events within the organization, enabling individuals to compare their information and thereby facilitating informed decision-making (Giardini & Wittek, Reference Giardini and Wittek2019). It is believed that gossip can be an important tool in understanding the social dynamics within organizations, especially in organizational structures where official communication channels are limited or ineffective.

However, the motivations behind gossip are not solely positive. In particular, negative gossip can serve as a mechanism of social control and power within the organization, potentially carrying the intention of harming the organization or colleagues. For example, it has been observed that negative workplace gossip is linked to a decrease in job satisfaction among employees and an increase in intentions to leave the job because this situation creates a hostile atmosphere that undermines morale and commitment (He & Wang, Reference He and Wang2022).

In addition, the participants indicated that the characteristics of the organization where the gossip occurs significantly influence the motivations underlying the gossip. For example, in organizational environments with high-stress levels, gossip can serve as a coping mechanism for employees experiencing emotional difficulties (Bulduk, Özel & Dinçer, Reference Bulduk, Özel and Dinçer2016). It is particularly believed that in countries with collectivist cultural characteristics, information sharing among individuals can provide support to one another during tough times and may even lead to increased enjoyment in their work. Conversely, Pheko (Reference Pheko2018) notes that in organizational structures with intense competitive relationships, such as those in the private sector, gossip can become more aggressive, with individuals using it to undermine their colleagues or gain an advantage over them. This situation is considered significant because it demonstrates, as particularly emphasized by the participants in this research, that organizational culture and existing group dynamics play a critical role in shaping the nature and motivations of gossip. Additionally, the individuals involved in this research indicate that social networks and internal group relationships within the organization can also shape gossip motivations, and employees are more likely to gossip with those with whom they have strong relational ties (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010).

Examining the statements provided by participants in response to the second research question reveals that gossip can significantly impact workplace dynamics, employee emotions and attitudes, and overall organizational effectiveness. Despite the generally negative perception of organizational gossip, evaluating its outcomes reveals a multifaceted structure encompassing harmful and beneficial outcomes. It is noteworthy that the participants in this study emphasized the impact of organizational gossip on employees’ emotions, attitudes, and behaviors and its effect on trust relationships in the workplace. Similarly, Kurland and Pelled (Reference Kurland and Pelled2000) demonstrated how gossip can function as a mechanism of power and influence over employees and how this situation can undermine trust between employees and management. In an organizational environment where negative gossip about employees occurs, trust relationships can be undermined, leading to tension and conflicts among individuals (Arian, Kozekanan & Zehtabi, Reference Arian, Kozekanan and Zehtabi2011).

Detailed examination of participant responses reveals that organizational gossip can have multifaceted effects, primarily on employees’ emotions, attitudes, and behaviors. Examining the relevant literature reveals results that support this finding. For instance, Dai, Zhuo, Hou and Lyu (Reference Dai, Zhuo, Hou and Lyu2022) emphasize that these positive interactions establish a foundation for employees to feel more valued and recognized, thereby increasing job satisfaction and overall emotional well-being. On the contrary, participants have mentioned the negative effects of workplace gossip on employees’ emotional states and the attitudes they develop towards the work environment. Indeed, Zong, Xu, Zhang and Qu (Reference Zong, Xu, Zhang and Qu2021) emphasize that negative gossip can create a foundation for emotional exhaustion and mood deterioration among employees that adversely affect individuals’ job performance and levels of organizational commitment. Furthermore, Zong et al. (Reference Zong, Xu, Zhang and Qu2021) assert that negative gossip erodes the organizational self-esteem of employees, resulting in feelings of loneliness and enduring harm to their overall morale (Song & Guo, Reference Song and Guo2022). Furthermore, the participants stated that negative gossip could lead employees to engage in defensive behaviors and experience concerns about their future in the organization because they feel threatened and insecure. At this point, the significance of the emotional burden left on individuals by being involved in the negative gossip process in the work environment is notable. The burden in question can make employees feel worthless and unsupported by their organizational structure, leading to emotional detachment from their organizations and jobs. According to Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee (Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2014), this burden can cause employees to feel worthless, unsupported by their organizational structure, and ultimately develop an emotional detachment from their organizations/jobs.

Depending on the findings, motivations for the emergence of gossip in the workplace is seen that the cultural codes of employees can also facilitate the behavior in question. Different cultures have varying norms, values, and communication styles that shape how individuals perceive and engage in gossip. As it is known, the work culture in Turkey is mainly influenced by collectivism, high-context communication, and medium-high power distance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), and therefore, all these factors shape the way and effect of gossip in the workplace. Accordingly, it is quite possible that in a social interaction process where social ties are strong and loyalty is reinforced and valued, employees may consider gossip as a way of maintaining group cohesion. In addition, it is known that employees are more cautious than usual, especially when talking about sensitive issues, and prefer informal ways of sharing information that contains subtle messages/implications. This can be considered as one of the reasons for the respondents’ preference for high-context communication. In addition, especially in organizations with a hierarchical structure, it is inconvenient for employees to express/confront their dissatisfaction with their managers for various reasons. For this reason, it is seen that gossip channels created by employees among themselves are used as an informal communication tool that serves to express ideas. Therefore, understanding cultural tendencies is important when analyzing gossip in diverse workplaces, as it provides insight into both the motivations behind gossip and its potential impact on organizational dynamics.

Additionally, organizational gossip plays an important role in shaping interpersonal relationships in the workplace. Similarly, Zhong and Tang (Reference Zhong and Tang2023) indicate that individuals, particularly in environments where negative gossip is prevalent, tend to distance themselves from others, participating in their work less than usual, and due to the feelings of loneliness they experience, their intention to leave their jobs increases. On the contrary, in a work environment where positive gossip occurs, it reinforces feelings of friendship and solidarity among employees, increasing teamwork and collaboration (Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012). The research participants also discussed gossip’s potential impact on interpersonal dynamics and organizational culture. In addition, Arian and his colleagues (Reference Arian, Kozekanan and Zehtabi2011) state that promoting a collaborative culture in organizations can reduce the negative effects of gossip. It is believed that if organizations prioritize trust and open communication among employees, the likelihood of gossip developing and its destructive effects may be reduced. On the contrary, it has been stated that gossip in a competitive organizational culture can shape power relations and areas of conflict among employees. From this perspective, individuals are believed to intentionally initiate negative gossip processes to weaken their colleagues and gain a power advantage over them. This competitive atmosphere inevitably creates a foundation for increased stress levels and anxiety among employees, leading to a deterioration of well-being in the workplace (Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012). Interestingly, participants have expressed that gossip within the organization can serve as a coping mechanism for employees with workplace concerns. Jiang, Xu & Hu’s (Reference Jiang, Xu and Hu2019) study confirms this finding. The study in question states that gossip can contribute to alleviating the negative effects experienced by workplace colleagues who share similar feelings. This situation allows employees to use gossip to come together and form common bonds, thereby reducing the shared concerns they experience.

Finally, the participants made some statements about the organizational effects of gossip. One of the important findings of the research is that gossip can create a new communication channel within the organization, and that a climate of distrust may become widespread. In addition, it is stated that the spread of gossip, like a spiral throughout the organization, creates a basis for employees to engage in rude behaviors. Indeed, Brandy and her colleagues (Reference Maynard, Solis, Miller and Brendel2017) stated in their study that negative gossip can heighten the visibility of uncivil behaviors in the workplace. Similarly, Kulik, Bainbridge and Cregan (Reference Kulik, Bainbridge and Cregan2008) stated in their study that gossip can contribute to an atmosphere of distrust within the organization and, when evaluated in terms of the organization, it can damage individuals’ morale and cohesion in a way that affects the organization’s overall efficiency. When evaluated from this perspective, it is believed that this research’s results are valuable in revealing the multifaceted nature of gossip in working life, both harmful and potentially beneficial. At the same time, this situation is important in demonstrating the complexity and frequency of the role of gossip in organizations. As previously stated, negative gossip can adversely affect positive feelings and attitudes, such as interpersonal trust and commitment, leading to harmful outcomes. In contrast, positive gossip strengthens social connections and enhances group loyalty (Fehr & Seibel, Reference Fehr and Seibel2023). It is considered vital for organizational leaders to understand this dual structure to harness the potential benefits of gossip and mitigate its harmful effects.

Study 2

Study 1 highlights the significant impact of workplace communication on employees’ emotions, attitudes, and behaviors. To build upon these findings, Study 2 was designed to explore the qualitative data on how employees perceive themselves, their feelings toward the organization, and their intention to stay at work in the context of gossip. It is hypothesized that positive gossip will enhance the employee’s connection with the organization, alleviate feelings of isolation at work, and not adversely affect their intention to stay. Conversely, negative gossip is expected to have the opposite effect on these relationships. The research model of Study 2, developed within this framework, will be further discussed below.

Theory and hypothesis development

Affective Events Theory

According to the Affective Events Theory (AET; Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996), the main idea of the theory explains how emotions and moods influence employees’ behaviors. It suggests that the emotional experiences individuals have had in the past continue to influence their current organizational behaviors. The attitudes and behaviors of employees within an organization are impacted by the emotions and moods they experience, which are influenced by both internal and external environmental factors. These emotions can guide individuals in their responses to new events and interactions (Weiss & Beal, Reference Weiss, Beal, Ashkanasy, Härtel and Zerbe2005). Put simply, the emotional impact of an event during the day can extend into later parts of the same day. This suggests that the emotional responses triggered by work events shape employee attitudes and reactions to emotional experiences in the workplace (Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, Reference Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2008). Given that each employee has unique individual tendencies, including character and experience, it’s natural to expect that different work events will evoke varied emotions and, consequently, lead to diverse work attitudes and behaviors (Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, Reference Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2008).

AET offers a crucial theoretical framework for understanding the relationships between the variables in this study. It explains how gossip influences the emotional reactions of employees and how these reactions impact organizational outcomes, such as affective organizational commitment, feelings of loneliness, and turnover intention.

Gossip and turnover intention

As organizational gossip is a communication mechanism that mediates the spread of both true and false information (Wittek & Wielers, Reference Wittek and Wielers1998), it is almost inevitable to feel its positive and negative effects (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010; Lyu et al., Reference Lyu, Wu and Yurong Fan2024) as it arouses interest or discussion within the organization (Dores Cruz, Nieper, Testori, Martinescu & Beersma, Reference Dores Cruz, Nieper, Testori, Martinescu and Beersma2021). Eder and Enke (Reference Eder and Enke1991), researchers who emphasized the positive effect of gossip in the workplace, claimed that it is the most common salient social process in dyadic conversation and fulfills an essential need in the individual’s developmental process. Noon and Delbridge (Reference Noon and Delbridge1993) supported the idea that informal social networks, like gossip, play a role in developing intragroup communication and collective identity (Crampton, Hodge & Mishra, Reference Crampton, Hodge and Mishra1998). In addition, researchers argued that gossip helps individuals form important social connections, become part of a group, manage relationships within the group, and maintain membership (Farley, Reference Farley2011; Soeters & van Iterson, Reference Soeters, van Iterson, Licoppe and Goudsblom2002). Therefore, eliminating this phenomenon can harm organizational communication. Most importantly, it inhibits the information dimension of gossip. According to Peters, Jetten, Radova and Austin (Reference Peters, Jetten, Radova and Austin2017), positively sharing information about the behavior of others within an organization can enhance motivation. For instance, communicating success stories and acknowledging achievements can significantly bolster employee morale, positively influencing others within the organization (Eder & Enke, Reference Eder and Enke1991). At the same time, the gossip mechanism can promote the adoption of beneficial norms within the organization and can be leveraged to build internal organizational reputation and influence (Grosser, Kidwell & Labianca, Reference Grosser, Kidwell and Labianca2012). Encouraging positive communication in organizations by celebrating employee achievements, recognizing hard work, and sharing inspiring stories can foster a more positive and supportive work environment (Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012).

In the model suggested by Muchinsky and Morrow (Reference Muchinsky and Morrow1980), it is anticipated that employees will be inclined to stay in their current jobs due to the positive aspects of their work environment. As it is known, employees’ turnover intention is the psychological and behavioral inclination to leave their current organization or profession (Griffeth & Hom, Reference Griffeth and Hom1988; Mobley, Reference Mobley1982). Therefore, the positive aspects of organizational gossip lead to low levels of perceived job stress, experiencing positive emotions, and having a strong perception of the company’s reputation. Therefore, it is believed that AET, which explains the relationship between emotional reactions to work events and employees’ attitudes and behaviors, will also impact the outcome of this study, specifically turnover intention. In this direction, this positive perception is fostered by an employee-centered work environment, possibly facilitated by informal communication such as gossip. This expectation applies to employees in both the private and public sectors. The findings of our qualitative study align with Muchinsky and Morrow’s (Reference Muchinsky and Morrow1980) model. Participants indicated that positive gossip triggered positive emotions and, as suggested by AET, contributed to a positive workplace environment. They reported that gossiping helped them relieve stress, enjoy their time at work, and develop a sense of satisfaction with their organizational settings. These findings support the literature-based expectation that the model applies to both private- and public-sector employees. Our research enhances the theoretical understanding and empirical evidence regarding how a positive work environment increases employees’ motivation to stay engaged at work.

Hypothesis 1: While developing relations dimension of gossip increases, turnover intention decreases for both public- and private-sector employees.

Hypothesis 2: While having information dimension of gossip increases, turnover intention decreases for both public- and private-sector employees.

On the other hand, although Eder and Enke’s (Reference Eder and Enke1991) studies emphasize the positive aspects of gossip, the general opinion agrees that the concept can be a malicious or negative action (Morrill, Reference Morrill1995). Research (see Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012; Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Kidwell and Labianca2012; Kim, Shin, Kim & Moon, Reference Kim, Shin, Kim and Moon2021; Martinescu, Jansen & Beersma, Reference Martinescu, Jansen and Beersma2021; Wittek & Wielers, Reference Wittek and Wielers1998; Wu, Kwan, Wu & Ma, Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018) indicates that negative gossip, which tends to be more common, can harm relationships, diminish trust, and create a toxic work environment (Michelson et al., Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010). Moreover, third-party information can sometimes lead to unnecessary anxiety and uncertainty in the work environment due to incomplete or incorrectly conveyed facts (Wert & Salovey, Reference Wert and Salovey2004). Inaccurate or exaggerated information can unjustly damage someone’s reputation and impact their career advancement (Kurland & Pelled, Reference Kurland and Pelled2000). As gossip content spreads upward, it can undermine trust between employees and management. Employees may hesitate to share information openly or collaborate effectively (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Kwan, Wu and Ma2018). Song and Guo (Reference Song and Guo2022) provided additional evidence of the negative impact of workplace gossip. Their research findings contradicted those of Farley (Reference Farley2011), showing that negative workplace gossip can harm employees’ social relationships, particularly regarding trust and cooperation.

The impact of negative gossip on employees’ turnover intention may differ based on whether they work in the public or private sector. The perception of job security is an important factor in motivating employees, particularly in the public sector, where job security often plays a significant role in people’s decision to work in public service (see part of Private vs Public-sector: Differences in the Job Security Perception of Employees). Research indicates that public-sector employees place a higher value on job security compared to their counterparts in the private sector. As a result, this tendency contributes to lower turnover rates within the public sector (Willem et al., Reference Willem, De Vos and Buelens2010). Public-sector employees prioritize job security and are less likely to leave their positions, even when affected by negative gossip, due to the challenges of finding new employment. In contrast, private-sector employees, who have less job security, may be more inclined to leave a toxic work environment since they can more easily find comparable roles. Based on these observations, the third hypothesis states that the negative impact of gossip on turnover intention is weaker for public-sector employees than for private-sector employees. Therefore, the third hypothesis of the study is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3: While organizational harm dimension of gossip increases, Turnover intention increases for private-sector employees but not for public-sector employees.

Affective organizational commitment

Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) proposed that organizational commitment revolve around employees’ commitment to the organization because they ‘want’, ‘need’, or ‘feel obligated’. The commitment form of employees who choose to remain in the organization because they want to be known as affective commitment. Affective commitment is generally defined as ‘the emotional bond of employees to their organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1996). An employee’s emotional state may be influenced by individual tendencies stemming from positive and negative gossip within the workplace. For instance, the dimensions of gossip, such as having information and developing relations dimensions of gossip, fulfill the socialization needs of employees within the organization and promote workplace friendships (Zong et al., Reference Zong, Xu, Zhang and Qu2021). Considering an individual’s need to establish relationships, the work environment becomes more enjoyable for employees who fulfill their social needs through informal communications and the exchange of information that they cannot obtain through formal channels (Coşkun, Reference Coşkun2020). Interacting and sharing important or unimportant information to create stable relationships and their own ‘circles’ will foster deep emotional connections between individuals (Cheng, Kuo, Chen, Lin & Kuo, Reference Cheng, Kuo, Chen, Lin and Kuo2022). As a structure that fosters employee connection, gossip enhances solidarity and teamwork by creating team awareness (Melwani, Reference Melwani2012). Positive organizational gossip is expected to boost emotional commitment to the organization by facilitating employee communication and fostering relationships. Additionally, informal communication can help employees obtain information quickly, reducing uncertainty and increasing psychological safety (Alshehre, Reference Alshehre2017).

Research on AET indicates that both positive (e.g., high perception of organizational support) and negative (e.g., low perception of organizational justice) emotional events in the workplace significantly impact employees’ job satisfaction (Wegge, Van Dick, Fisher, West & Dawson, Reference Wegge, Van Dick, Fisher, West and Dawson2006; Weiss & Beal, Reference Weiss, Beal, Ashkanasy, Härtel and Zerbe2005). Hence, it is widely understood that job satisfaction, as a significant result of AET, is negatively correlated with the intention to leave (Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, Reference Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2005; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2011; Shaw, Reference Shaw2004). It is also recognized that a lasting sense of job satisfaction can be attained through organizational commitment (Patrick & Sonia, Reference Patrick and Sonia2012; Van Scotter, Reference Van Scotter2000). According to this theory, positive gossip can help create an environment where positive emotions act as a barrier to employees wanting to leave their jobs. It is believed that positive gossip can enhance an employee’s emotional commitment to the organization by eliciting a positive emotional response. As a result, these positive emotions can improve the employee’s job commitment by fostering a positive work attitude. In this scenario, the employee’s intention to leave the job is assumed to be reduced. This theory applies to both public- and private-sector employees.

Our qualitative research findings align with the premise of AET, which suggests that positive and negative emotional events in the workplace influence employees’ feelings, attitudes, and behaviors related to their work. Participants indicated that positive gossip strengthens emotional bonds among colleagues, leading to favorable emotional responses within the workplace. These positive emotions enhance employees’ emotional bonds to their organization and increase their commitment. Thus, their job satisfaction can increase, and they don’t have turnover intentions. Our research predicts that positive gossip can have remarkable effects on affective commitment for employees in both the private and public sectors. Additionally, these effects contribute positively to reducing turnover intentions. Consequently, we posted that:

Hypothesis 4a: Affective Organizational Commitment mediates the relationship between developing relations dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Hypothesis 4b: Affective Organizational Commitment mediates the relationship between having information dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention for public- and private-sector employees.

We have acknowledged that, due to the individual nature of AET, different employees may experience varying emotions during work events (see Ashton-James & Ashkanasy, Reference Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2008). Organizational gossip can impact employees differently, some finding it enjoyable and others annoying. It’s important to consider the differing effects of gossip on individuals within the organization (Michelson et al., Reference Michelson, Van Iterson and Waddington2010). Organizational gossip can harm an employee’s emotional well-being, primarily due to its harmful nature (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996). Majorly, the content of harmful gossip may lead to the erosion of employee trust and morale (De Gouveia, Van Vuuren & Crafford, Reference De Gouveia, Van Vuuren and Crafford2005). This is because rumors are spread in the organization without clear information about what is fact and what is not (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Kidwell and Labianca2012). Adversely, because negative gossip is often concealed and indirect, it is challenging to identify the source, verify its content, or prevent its spread (Foster, Reference Foster2004). Issues that cannot be openly discussed may result in prejudice, misunderstandings, and employee conflicts (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010). Continuously spreading rumors and gossip might give rise to biased opinions and divisions, potentially harming employees’ morale (Hartung, Krohn & Pirschtat, Reference Hartung, Krohn and Pirschtat2019). New rumors and gossip can lead to the formation of biases and factions, which may hurt employees’ feelings and cause a loss of reputation.

While gossip can temporarily relieve work stress, it inevitably leads to a bad mood for the person being gossiped about. This negative conversation can reduce emotional commitment and trigger the intention to leave the job. However, the impact on the intention to leave the job may vary between public- and private-sector employees. The main reason for this difference can be based on the psychological security comfort that job security provides. Being a public employee in Turkey is desirable due to the guarantee of job security for life, which is a significant advantage for individuals. An employee who cannot afford to lose this benefit is estimated to have low emotional commitment but low or no intention to leave the job. Qualitative research findings align with this information. Some public employees generally highlighted the ‘job guarantee’, viewing it as an opportunity that was hard to relinquish.

Hypothesis 4c: Affective Organizational Commitment mediates the relationship between the organizational harm dimension of gossip and turnover intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Loneliness in the workplace

People describe a good work environment as a place where individuals are trusted and enjoy working and where they take pride in their work (Wright, Burt & Strongman, Reference Wright, Burt and Strongman2006). Based on this definition, positive gossip in organizations can improve social relations and increase emotional connections (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Wu and Lin2018), thus reducing feelings of loneliness. Numerous researchers have highlighted the benefits of positive gossip in cultivating a harmonious work environment within organizations. They have also recognized gossip as a valuable communication mechanism that promotes unity among individuals (Yücel et al., Reference Yucel, Şirin and Baş2023; Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012; Estévez et al., Reference Estévez, Wittek, Giardini, Ellwardt and Krause2022). By engaging in gossip, employees can alleviate the burden of their daily routine and personal problems (Alshehre, Reference Alshehre2017). Loneliness in the workplace is the absence of meaningful interpersonal relationships with others (Zhou, Reference Zhou2018). Lam and Lau (Reference Lam and Lau2012) emphasized that incomplete and insufficient social connections characterize workplace loneliness. This highlights the importance of considering individuals’ subjective experiences, such as their levels of closeness, interpersonal trust, and support, when addressing loneliness in the workplace (Özçelik & Barsade, Reference Özçelik and Barsade2018). The study’s final hypothesis, centered around the feeling of loneliness, investigates how the subdimensions of emotional deprivation and social companionship can influence the relationship between workplace gossip and the intention to leave the job.

First, the emotional deprivation dimension emphasizes the quality of the employee’s relationships with their coworkers (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Burt and Strongman2006). An emotionally deprived employee refrains from sharing her thoughts with colleagues, perceiving a lack of understanding and distancing herself/himself as an outsider (Wright, Reference Wright2005). From this perspective, if we remember that gossip occurs between individuals who trust each other (Burt & Knez, Reference Burt, Knez, Kramer and Tyler1996), it is feasible for an employee to build trust and closeness with another through gossip (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Chang, Quinton, Lu and Lee2014). Employees who openly share their knowledge and express their thoughts and feelings through interpersonal communication can strengthen their relationships. Additionally, an employee experiencing negativity can find relief and build intimacy through sharing these feelings with others, ultimately improving their emotional state and relationship dynamics (Fine & Rosnow, Reference Fine and Rosnow1978). From another perspective, employees can also distance themselves from daily issues or negativity and shift their focus to another subject through gossip (Alshehre, Reference Alshehre2017).

It is not suggested that gossip and all its dimensions affect turnover intention in the same way as assumed by other hypotheses. Sharing positive gossip (developing relationships and having information dimensions) is anticipated to reduce employees’ feelings of emotional deprivation, activate positive emotions, and decrease their intention to leave the job. Our qualitative research findings align closely with existing literature on the role of gossip in strengthening emotional connections among employees. Participants emphasized that they could form warm relationships with their coworkers, mainly through positive gossip. As a result, they found the workplace enjoyable and did not experience feelings of loneliness. In light of this information, it is estimated that this assumption will be similar for individuals working in both the private and public sectors.

Hypothesis 5a: Emotional Deprivation mediates the relationship between developing relations dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Hypothesis 5b: Emotional Deprivation mediates the relationship between having information dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention for public- and private-sector employees.

However, the sense of emotional deprivation is likely to increase in the dimension of organizational harm, which refers to the negative aspect of gossip. This idea can be considered from two perspectives. First, negative gossip, like positive gossip, requires meaningful bonds based on employee trust (Ellwardt et al., Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and Wittek2012; Estévez et al., Reference Estévez, Wittek, Giardini, Ellwardt and Krause2022). In fact, due to the risk involved in negative gossip, a strong tendency to trust may be necessary between the parties (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell and Labianca2010). It may be mistaken for friendship if negative gossip is exchanged between parties. However, regardless of whether it is directly related to the organization (e.g., related to the organization’s direction, management, or a colleague), an employee’s loneliness can increase in proportion to their decreasing level of social interaction when they are unable to share their feelings or information (O’Keefe & Sulanowski, Reference O’Keefe and Sulanowski1995). Therefore, employees who do not engage in negative gossip may feel lonely at work due to the lack of deep, trusting ties with colleagues.

Second, negative gossip in the workplace can evoke negative emotions, diminish trust, and harm interpersonal relationships (Aboramadan, Turkmenoglu, Dahleez & Cicek, Reference Aboramadan, Turkmenoglu, Dahleez and Cicek2020; Liff & Wikström, Reference Liff and Wikström2021). Employees exposed to such gossip may distrust the gossipers (Mokwebo & Carrim, Reference Mokwebo, Carrim and Chang2023), avoid meaningful interactions, and experience a toxic atmosphere. This environment fosters loneliness, reducing emotional commitment and potentially increasing turnover intention (Ertosun & Erdil, Reference Ertosun and Erdil2012; Özçelik & Barsade, Reference Özçelik and Barsade2018; Wahyuni & Ikhwan, Reference Wahyuni and Ikhwan2022). Research supports these findings, showing that loneliness at work decreases organizational commitment and prompts intentions to leave. Qualitative findings align with this literature, revealing that participants exposed to negative gossip reported surface-level interactions, interpersonal conflicts, and a preference for solitude, underscoring the detrimental impact of a gossip-driven toxic workplace (Giardini, Balliet, Power, Számadó & Takács, Reference Giardini, Balliet, Power, Számadó and Takács2022; Wahyuni & Ikhwan, Reference Wahyuni and Ikhwan2022).

Following this situation, the individual’s attitude and behavioral response toward work indicate an intention to leave the job. The career paths for private- and public-sector employees may differ. While job security may lead a public-sector worker to stay despite feelings of isolation, private-sector employees might actively seek a job that utilizes their current skills.

Hypothesis 5c: Emotional Deprivation mediates the relationship between the organizational harm dimension of gossip and turnover intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Social loneliness refers to the absence of social connections among employees or an individual’s inability to be part of a community that will accept them (Wright, Reference Wright2005). With positive gossip and social friendships, employees may join the social network and see themselves as part of the work social network. Wright and Silard (2020) acknowledge that if an employee is gossiping about social issues with someone in the organization, it indicates that the employee is not isolated from the organization. Furthermore, Noon and Delbridge (Reference Noon and Delbridge1993) suggested that gossip is a communication tool that fosters the development of a collective identity. This is because gossip allows employees to feel a sense of belonging and to enhance their relationships through social interaction (Silard & Wright, Reference Silard and Wright2020). Sharing work-related problems and personal thoughts relieves employees, and the gossip’s developing relations dimension reinforces their positive feelings. Wright and Silard (Reference Wright and Silard2021) noted that when employees gossip about social issues, it suggests they do not feel isolated within the organization. Our qualitative findings support this perspective, showing that participants use gossip to strengthen their social connections and foster a sense of unity, togetherness, and friendship. Furthermore, as discussed in the literature section, there is a notable overlap between our qualitative findings and Noon and Delbridge’s (Reference Noon and Delbridge1993) emphasis on gossip’s role in forming collective identity, particularly regarding themes of friendship, intimacy, and strong social relationships that emerged during in-depth interviews with participants. The participants reported that sharing their problems had a calming effect and helped improve their relationships. Overall, these findings indicate a strong alignment between the theoretical framework in literature and the qualitative data collected. In the dimension of having information, employees can spend time together during their breaks, stay informed about organizational updates, and feel like a part of the organization. The assumptions are similar for both public- and private-sector employees.

Consequently, the hypothesis below is provided:

Hypothesis 6a: Social Companionship mediates the relationship between developing relations dimension of gossip, and turnover intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Hypothesis 6b: Social Companionship mediates the relationship between having information dimension of gossip, and turnover intention for public- and private-sector employees.

Employees affected by harmful gossip often experience social isolation and struggle to express their concerns or opinions. They may feel excluded from workplace social circles, avoid sharing ideas, and even spend breaks alone to escape gossip (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Burt and Strongman2006). This self-imposed isolation limits participation in social and organizational activities, reducing communication and engagement (De Gouveia et al., Reference De Gouveia, Van Vuuren and Crafford2005). Qualitative findings confirm that employees frequently adopt solitude as a coping mechanism, restricting social interactions to shield themselves from gossip’s negative impacts and safeguard their reputations.

As a result, this lack of communication can contribute to an increasing sense of insecurity and the proliferation of negative feelings (Liff & Wikström, Reference Liff and Wikström2021). However, in line with existing research on workplace loneliness, individuals can mitigate feelings of isolation and inadequacy by expressing themselves (Wright, Reference Wright2005). Because effective communication helps group members build trust and understanding through timely and meaningful relationship building (Asunakutlu, Reference Asunakutlu2002).

As Foster (Reference Foster2004) explains, negative gossip tends to be covert and indirect, and employees may perceive this information sharing as a violation of organizational ethics when viewed from a broader perspective. This is not an unreasonable thought because, during gossip, the sender communicates with the receiver about a target who is unaware of the content or is not present (Dores Cruz et al., Reference Dores Cruz, Nieper, Testori, Martinescu and Beersma2021). This time, the employee who doubts the personal qualities and professional ethics of the person spreading gossip may develop negative feelings toward them . Thus, a hostile social atmosphere and public opinion environment are created, and this interpersonal environment affects employees’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Furthermore, employees who choose not to engage in negative workplace gossip feel isolated from other organization members due to ethical concerns (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Wu and Lin2018).

Such emotional reactions may lead to employees’ intention to leave because they trigger affect-focused behaviors and work attitudes (Guenter, van Emmerik & Schreurs, Reference Guenter, van Emmerik and Schreurs2014). Building on Weiss and Cropanzano’s (Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996) AET that work environments can directly affect job attitudes, this study’s final proposition is that harmful gossip will affect turnover intentions through social companionship. However, as AET suggests, the impact of emotions on attitudes and behaviors may vary depending on individual circumstances. Therefore, being a public- or private-sector employee will affect the Social Companionship – organizational harm dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention relationship differently. Although public employees lack social companionship due to harmful gossip, their intention to leave the job will be low.

Hypothesis 6c: Social Companionship mediates the relationship between the organizational harm dimension of gossip and Turnover Intention for public- and private-sector employees.

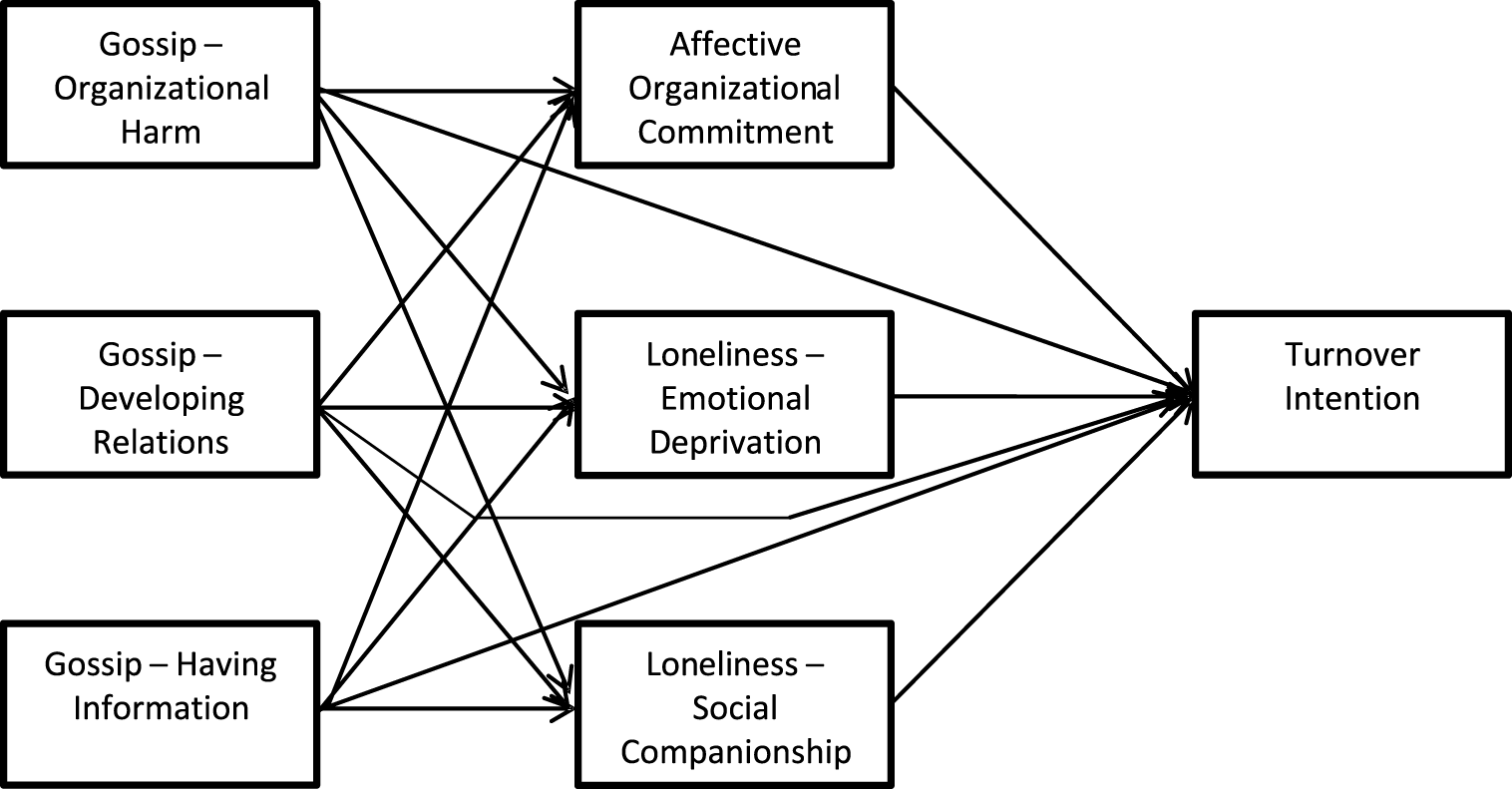

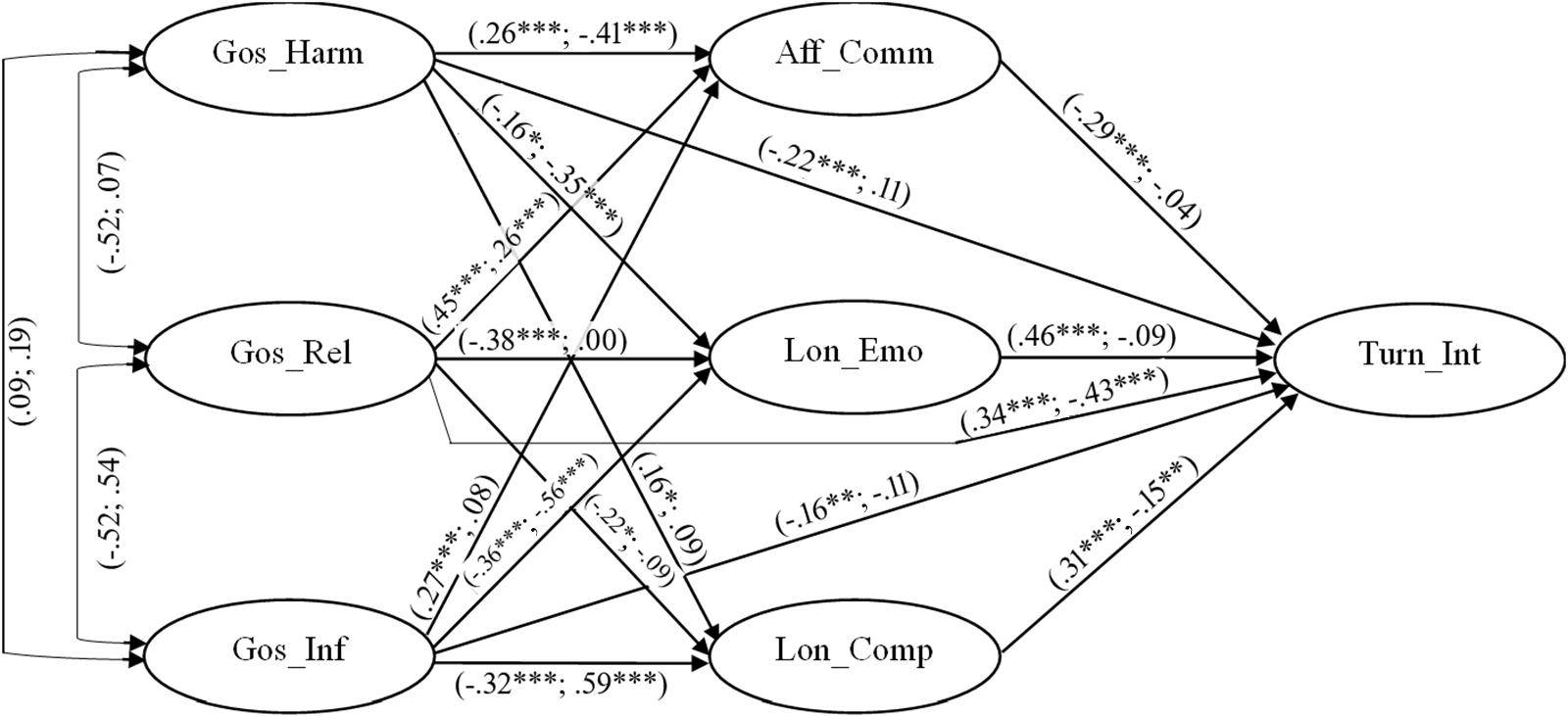

The model of the study which is shown in Figure 1 shows the phenemenons relations.

Figure 1. Model of the study.

Method

Research setting and sample

To test the hypotheses of the study, the organizations in the service sector in Turkey have been reached. The sample group consists of people working in businesses that differ in terms of ownership type, namely public and private sectors, following the research model. To compare public- and private-sector employees, it was decided that the dynamics of the businesses would be the most suitable for this comparison. First, the activities of both public- and private-sector organizations are similar, and they are all in the service sector category (such as bank employees, university administrative staff, notaries, or insurance agencies). Second, employees in both sectors have been working in the same workplace for at least one year to ensure that employees know each other and are involved in gossip channels. The employees of the organizations have reached out to obtain the necessary verbal permission and distributed the survey to the appropriate pilot group online and in paper format.

Following the preparation of the survey, the pilot survey was distributed to 43 participants. The feedback regarding the clarity of the survey was collected from the participants. After the satisfaction of the researchers about the questionnaire’s quality, the survey was distributed to the sample group. (Yaslioglu, Reference Yaslioglu2017). The survey was sent to 752 participants online who are working in Istanbul/Turkey. A total of 698 of the participants reacted, and 87 of the reacted surveys were eliminated due to missing answers. Following Schafer’s (Reference Schafer1999) study, a 5% cutoff level was used to exclude the missing answers from the study. Thus, data obtained from a total of 611 participants were analyzed. Demographical Statistics of Participants (Age = 20–56 years). Gender; (Female = 311, Male = 300). Marital Status (Married = 256, Not Married = 355). Sector statistics, (Public = 290, Private = 321). Experience in the Organization (1–27 years). Number of Employees, (Less than 10 = 91, 11–50 = 198, 51–250 = 184, 251–500 = 34, 501–1000 = 11, More than 1001 = 92).

Survey data were collected using the random selection method. To measure the attention of the participants, the statement has included ‘If you are reading this statement, select ‘I disagree’ from the options below’ in the survey in an attempt to prevent possible random markings.

Assessment of Common Method Bias

Since the survey applied in the study is aimed at measuring the perceptions of the participants, it should be checked whether the data is affected by Common Method Bias (CMB) to ensure the validity of the findings. CMB was examined in two stages. In the first stage, the Harman’s single-factor test method was applied (Podsakoff and Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986). The results obtained show that the single-factor variance is 32.8. Since the result obtained is lower than the accepted 50% cutoff, it shows that the data obtained in the first stage are not affected by CMB (Podsakoff et al. Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

In the second stage, the Unmeasured Latent Method, which is considered a more reliable method by the researchers, was applied (Podsakoff et al. Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). The relationship between Item Loads was examined with and without the addition of a Common Latent Factor (CLF) (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Simmering and Sturman2009). Regardless of CLF presence, the variance indicated by the method factor is modest, and the differentiation of correlations does not exceed the threshold level. As a result of the findings, the variance among items can be explained to a single CLF. The results of the two applied methods reveal that there is no CMB effect in the study.

Measures

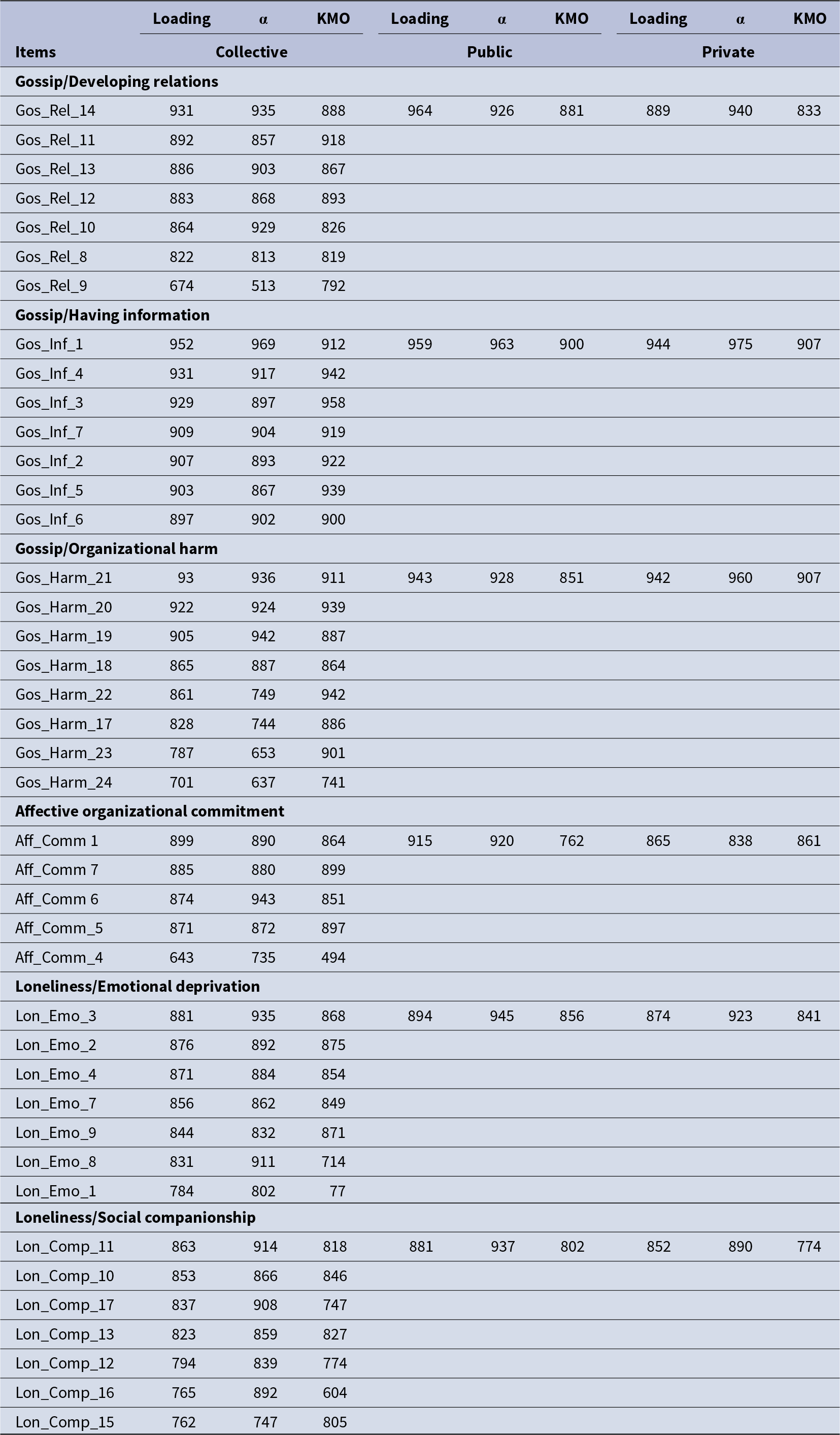

This study employed a survey technique, and we utilized four measurement tools in conjunction with a personal information form. The questionnaire has provided an opportunity for participants to measure the phenomena by using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Items, item loadings, Cronbach’s alpha value, McDonald’s Ω, and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value for the dimensions are given in Table 4. All the computed Cronbach’s alphas and McDonald’s Ωs are internally consistent (Vallerand & Richer, ). In addition, the combined scale and dimension results from Bartlett’s test are significant (p = .000 < .001).

Table 4. Factor analysis of the scales

The study employed the 3-item ‘Intention to Turnover Scale’, developed by Mobley, Horner, and Hollingsworth in 1978, to measure the intention to turnover as the dependent variable. Numerous research has successfully employed this single-dimensional scale, affirming its high validity and reliability in statistical terms (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Wang, Lan and Wu2022; Lin, Hu, Danaee, Alias & Wong, Reference Lin, Hu, Danaee, Alias and Wong2021; Tett & Meyer, Reference Tett and Meyer1993). Örücü and Özafşarlıoğlu (Reference Örücü and Özafşarlıoğlu2013) conducted the adaptation of the scale to Turkish culture and ensured its linguistic equivalence. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha reliability value, which consists of a single dimension like the original scale, is .90. None of the scale items include negative statements. Example item: Often think about quitting my present job.