Introduction

…The haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate. Baby, I’m just gonna shake, shake, shake, shake, shake. I shake it off, I shake it off (hoo-hoo-hoo)

–Taylor Swift

Dirty work refers to occupations that society deems unfavorable, often labeling those who perform these roles as “dirty workers” (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999; Hughes, Reference Hughes1958). Hughes (Reference Hughes1958, p. 122) defined dirty work as occupations that are “physically, socially, and morally tainted.”. Physically tainted dirty work refers to occupations that expose employees to direct dirt and hazardous conditions (e.g., w aste management); socially tainted dirty work refers to occupations that expose employees to direct engagement with stigmatized individuals (e.g., prisoners); and morally tainted dirty work refers to occupations that expose employees to activities society considers immoral and sinful (e.g., exotic dancers). This occupational stigmatization stems from societal perceptions of such jobs as undesirable or unclean. Research has shown that these perceptions of occupational stigma can have detrimental effects on employee behavior and self-image (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner2014; van Vuuren, Teurlings & Bohlmeijer, Reference van Vuuren, Teurlings and Bohlmeijer2012). Specifically, occupational stigmatization has been linked to withdrawal behaviors, heightened turnover intentions (Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Lam, Lai, Lennard, Peng and Chan2018), and diminished perceptions of work meaningfulness (Shepherd, Maitlis, Parida, Wincent & Lawrence, Reference Shepherd, Maitlis, Parida, Wincent and Lawrence2022; Zhang, Wang & Li, Reference Zhang, Wang and Li2023).

Employees experiencing occupational stigmatization often disassociate from their occupations or develop coping mechanisms to counter societal backlash (Bosmans et al., Reference Bosmans, Mousaid, De Cuyper, Hardonk, Louckx and Vanroelen2016; Rabelo & Mahalingam, Reference Rabelo and Mahalingam2019). However, we contend that the degree to which employees perceive and internalize occupational stigmatization is not uniform. Individual-level differences shape employees’ perceptions of their work situations (Scheier, Buss & Buss, Reference Scheier, Buss and Buss1978) and should determine how they respond to occupational stigma (Chon & Sitkin, Reference Chon and Sitkin2021; White, Stackhouse & Argo, Reference White, Stackhouse and Argo2018). Thus, this leads to our central research question: Are all dirty workers dissatisfied with their work, given the amount of social stigmatization they experience? Dirty work occupations are a necessary part of our economy. If there are ways to mitigate the detriments associated with such work, it would be of both theoretical and practical significance to those who study these unique professions.

To explore this perspective, we draw on the Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner & Schaufeli, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001), which posits that employees experience emotional exhaustion when job demands exceed the resources available to them. Consistent with this framework, prior research on dirty work has shown that such occupations impose significant emotional strain on employees (McMurray & Ward, Reference McMurray and Ward2014; Mikkelsen, Reference Mikkelsen2022; Sayre, Grandey & Chi, Reference Sayre, Grandey and Chi2020). Given the finite nature of emotional resources (Baumeister, Tice & Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Tice and Vohs2018; Liu, Prati, Perrewe & Ferris, Reference Liu, Prati, Perrewe and Ferris2008), we propose that the recurrent societal backlash associated with dirty work contributes to emotional exhaustion – a chronic state of emotional and physical depletion (Maslach & Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981). Employees experiencing emotional exhaustion report diminished happiness and an increased likelihood of burnout, both of which negatively impact their satisfaction. Building on these assertions, we argue that emotional exhaustion mediates the negative relationship between dirty work and three forms of satisfaction: job, career, and life satisfaction.

In line with JD-R theory and related research, personal characteristics can serve as resources that influence how employees experience and process their job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017; Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001). In this context, we examine the role of self-consciousness, defined as an awareness of oneself that facilitates the recognition, analysis, and management of environmental demands. We argue that lower levels of self-consciousness can function as a valuable personal resource, enabling individuals to shield themselves from the adverse effects of societal stigmatization. Employees with lower self-consciousness are less preoccupied with societal judgments about their work and, as a result, are less likely to internalize negative perceptions (Demerouti & Bakker, Reference Demerouti and Bakker2023). This reduced concern for external opinions enables individuals to detach from stigmatization, thereby mitigating the emotional toll typically associated with dirty work (Chon & Sitkin, Reference Chon and Sitkin2021).

Conversely, higher levels of self-consciousness operate as a demand, amplifying the emotional exhaustion that stems from engaging in stigmatized work. This heightened awareness of societal disapproval requires additional emotional labor, as these individuals expend greater effort managing both their work demands and the anticipated negative reactions of others (London, Sessa & Shelley, Reference London, Sessa and Shelley2023). Thus, while lower self-consciousness acts as a protective resource, higher self-consciousness exacerbates the emotional strain associated with stigmatized occupations.

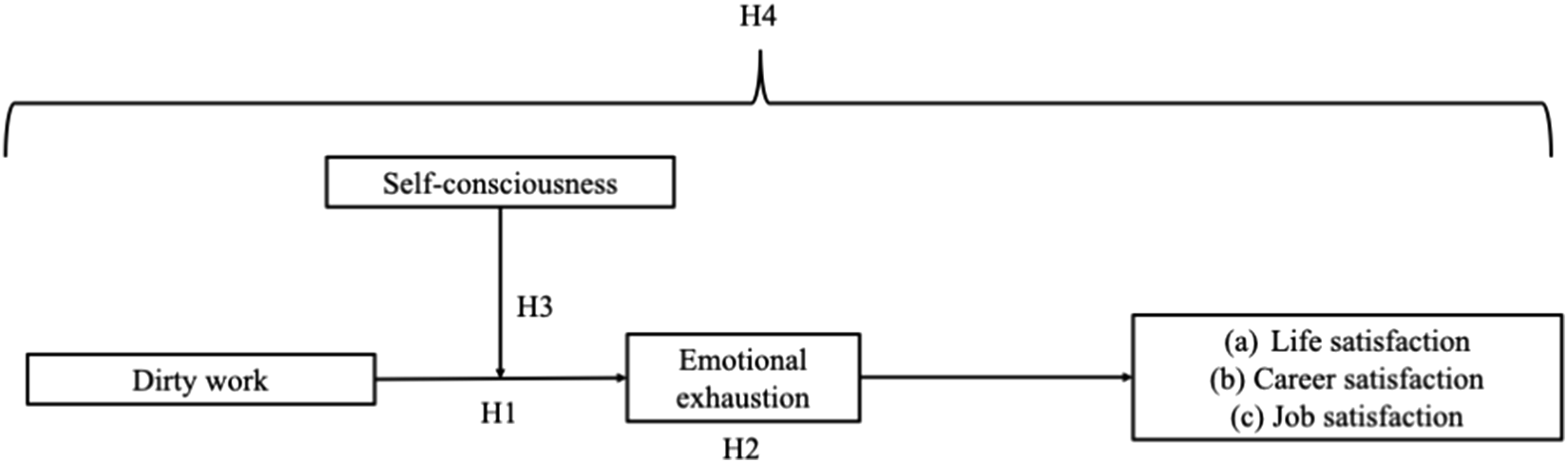

This study contributes to dirty work research in several important ways. First, we introduce self-consciousness as a personal characteristic that mitigates the negative effects of dirty work stigmatization. This adds a nuanced perspective to the understanding of how individual differences can interrupt the stigmatization process. Specifically, we demonstrate that not all employees are affected by societal judgments about their occupation, even when their work is socially stigmatized. Lower levels of self-consciousness serve as a personal resource, enabling individuals to work in professions, particularly those considered “dirty,” while maintaining satisfaction in their roles. Second, while there is an abundance of research on dirty work, much of it is qualitative (e.g., Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999; Blithe & Wolfe, Reference Blithe and Wolfe2017; Bosmans et al., Reference Bosmans, Mousaid, De Cuyper, Hardonk, Louckx and Vanroelen2016). Few studies quantitatively assess the causal effects of dirty work on employee outcomes. Additionally, although prior scholarship suggests that dirty work imposes an emotional burden (McMurray & Ward, Reference McMurray and Ward2014; Mikkelsen, Reference Mikkelsen2022), to our knowledge, no studies have explicitly examined emotional exhaustion as an outcome or as a mediating mechanism influencing employee attitudes. Thus, our study begins to quantify and measure a phenomenon that has largely been assumed rather than empirically tested. (See Figure 1 for conceptual framework).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the relationship between dirty work and employees’ outcome via emotional exhaustion, moderated by self-consciousness.

Theoretical background

Dirty work

Society frequently stigmatizes certain occupations, categorizing them as physically, socially, or morally tainted based on the nature of the tasks performed (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999; Hughes, Reference Hughes1958). Physically tainted occupations are those that directly expose workers to dirt, filth, or hazardous conditions, such as the work of miners or trash collectors. Socially tainted occupations involve direct interactions with marginalized or stigmatized individuals. Examples include correctional officers working with inmates or psychiatric ward attendants caring for individuals with mental illnesses (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner2014; Kreiner, Mihelcic & Mikolon, Reference Kreiner, Mihelcic and Mikolon2022). Finally, morally tainted occupations are associated with activities that society deems sinful, unethical, or corrupt. These roles often involve practices considered deceptive or morally questionable, such as those performed by strippers, personal injury lawyers, or debt collectors (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999).

Emotional exhaustion: a resource perspective

To investigate the relationship between dirty work, emotional exhaustion, and employee outcomes, we draw on the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007; Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001). The JD-R framework highlights two primary job characteristics: job demands and job resources. Job demands refer to the physical and psychological efforts required for employees to perform their work-related tasks. Physical job demands, for example, involve engaging in strenuous or taxing activities, which can lead to the depletion of personal resources. These demands not only exhaust employees’ resources but also heighten the strain associated with societal stigmatization of certain occupations (Kreiner et al., Reference Kreiner, Mihelcic and Mikolon2022). Prior research has connected job demands to various adverse outcomes, including burnout, disengagement (Crawford, LePine & Rich, Reference Crawford, LePine and Rich2010), and counterproductive work behaviors (Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). These consequences negatively impact both individual employees and their organizations (Downes, Reeves, McCormick, Boswell & Butts, Reference Downes, Reeves, McCormick, Boswell and Butts2021).

While job demands can exhaust energy, employees can draw on job-related and personal resources to help buffer the adverse effects of these demands. The second key component of the JD-R model – job resources – encompasses the physical, psychological, and social resources that employees utilize to cope with job demands (Mansour & Tremblay, Reference Mansour and Tremblay2021). Recent advancements in the JD-R framework suggest that personal resources, such as resilience and self-control, play a critical role in managing work environments and mitigating the negative consequences of job demands (Demerouti & Bakker, Reference Demerouti and Bakker2023; Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Personal resources represent an individual’s psychological capital, enabling them to effectively navigate and adapt to the challenges presented by their work environments (Kwon & Kim, Reference Kwon and Kim2020).

The central premise of the JD-R model is the interplay between job demands and job or personal resources and how these interactions affect employees’ well-being and performance (Bakker, Demerouti & Sanz-Vergel, Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Sanz-Vergel2023; Kwon & Kim, Reference Kwon and Kim2020). In the context of dirty work, the JD-R model suggests that employees must allocate substantial psychological resources to manage societal perceptions of their work as physically, socially, and morally undesirable. Research has shown that dirty workers often expend significant psychological effort to fulfill their responsibilities, utilizing discursive, behavioral, and ideological strategies to alleviate the strain and demands associated with their roles (Ashforth, Kreiner, Clark & Fugate, Reference Ashforth, Kreiner, Clark and Fugate2017; Kreiner et al., Reference Kreiner, Mihelcic and Mikolon2022). Building on this foundation, we propose that lower levels of self-consciousness – an ability to disregard societal judgments – can function as a vital personal resource, helping to mitigate the negative impact of dirty work.

Hypotheses development

Dirty work and emotional exhaustion: a job demand and resource-based perspective

Existing research highlights that the demands of life and work significantly influence individuals’ emotional and cognitive responses, often depleting their personal resources (Downes et al., Reference Downes, Reeves, McCormick, Boswell and Butts2021). When employees encounter challenges related to job demands, they draw upon personal resources, which can lead to the gradual depletion of their psychological and emotional reserves. Emotional resources, in particular, are finite, and individuals often strive to conserve these limited resources to sustain productivity (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). However, the continual expenditure of these resources can result in emotional exhaustion. Accordingly, we argue that individuals in dirty work occupations, when faced with societal backlash, expend their emotional resources at a higher rate, ultimately leading to depletion and emotional exhaustion (Lesener, Gusy & Wolter, Reference Lesener, Gusy and Wolter2019).

Emotional exhaustion is characterized as a chronic state of emotional and physiological depletion (Jackson & Maslach, Reference Jackson and Maslach1982). This condition reflects a loss of resources, including both emotional and physical capacities (Cropanzano, Rupp & Byrne, Reference Cropanzano, Rupp and Byrne2003; Hobfoll, et al Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Ashforth, Harrison and Corley (Reference Ashforth, Harrison and Corley2008) further observed that such resource depletion can lead individuals to lose their sense of self, and in some cases, result in disengagement from their work. Employees may experience strain due to societal perceptions of their work as being physically, socially, or morally tainted, often culminating in withdrawal behaviors (Westman & Eden, Reference Westman and Eden1997) or intentions to leave their jobs (Wright & Cropanzano, Reference Wright and Cropanzano1998). Empirical evidence has also linked emotional exhaustion to negative outcomes such as reduced job performance and diminished organizational citizenship behaviors (Cropanzano et al., Reference Cropanzano, Rupp and Byrne2003). Consistent with these findings, we propose that employees facing environmental strains related to the stigmatized nature of their work are likely to report lower levels of job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1: Dirty work is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

Dirty work and employee outcomes: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion

Employees in professions classified as dirty work often face substantial emotional and physical demands, necessitating the use of both personal and job-related resources. Managing these demands frequently depletes resources, particularly emotional reserves, and can lead to emotional exhaustion (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018; Tang & Vanderberghe, Reference Tang and Vandenberghe2020). Emotional exhaustion, a widely recognized outcome of sustained job-related stress (Kwon & Kim, Reference Kwon and Kim2020; Lee & Ashforth, Reference Lee and Ashforth1996), has been shown to significantly influence work-related attitudes and overall satisfaction (Wright & Cropanzano, Reference Wright and Cropanzano1998). Building on this foundation, our study posits that the demands associated with dirty work contribute to emotional exhaustion, which, in turn, impacts three critical forms of satisfaction: life satisfaction, career satisfaction, and job satisfaction.

Life satisfaction – defined as an individual’s overall evaluation of their life based on self-selected criteria (Shin & Johnson, Reference Shin and Johnson1978) – represents a critical component of well-being. Job demands, particularly those inherent in dirty work, can erode life satisfaction by depleting emotional resources, leaving employees disengaged and dissatisfied with their broader life circumstances (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001). When individuals compare their current life conditions to their idealized expectations, the emotional resource depletion caused by work-related stress can significantly lower their overall life satisfaction (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Accordingly, we propose that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and life satisfaction, as employees face challenges in preserving their emotional well-being under demanding work conditions.

Hypothesis 2a: Emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and life satisfaction.

Similarly, career satisfaction – defined as an individual’s evaluation of their progress and achievements within their professional role (Gattiker & Larwood, Reference Gattiker and Larwood1988) – is influenced by emotional exhaustion. Employees often hold specific expectations for their career trajectories, and when these expectations are unmet due to the stress and societal stigma associated with dirty work, emotional resources become depleted, resulting in reduced career satisfaction (Aryee & Luk, Reference Aryee and Luk1996; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). The stigma surrounding dirty work exacerbates emotional exhaustion, as employees may experience a diminished sense of fulfillment in their chosen career path (Dick, Reference Dick2005). Consequently, emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and career satisfaction, with the emotional strain of dirty work eroding employees’ sense of career-related contentment.

Hypothesis 2b: Emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and career satisfaction.

Finally, job satisfaction – defined as an individual’s overall sense of contentment with their specific work role (Diener, Diener & Diener, Reference Diener, Diener and Diener1995; Diener & Tay, Reference Diener and Tay2015) – is also influenced by the emotional exhaustion associated with dirty work. While some employees engaged in dirty work may find meaning and fulfillment in their roles (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999), the persistent strain of managing societal stigma and emotional demands can significantly diminish job satisfaction. As employees engage in emotional and cognitive evaluations of their work (Elfenbein, Reference Elfenbein2023), the demands of dirty work can affect their job satisfaction through the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. The ongoing depletion of emotional resources caused by work-related stress undermines employees’ perceptions of their job satisfaction, suggesting that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2c: Emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between dirty work and job satisfaction.

The moderating role of public self-consciousness

The ownership and control of personal resources are central tenets of the JD-R model. This framework highlights how individuals strategically manage their personal resources to mitigate the impact of job demands on outcomes such as emotional exhaustion (Demerouti & Bakker, Reference Demerouti and Bakker2023; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Within this framework, we identify self-consciousness as a critical personal resource that employees leverage to buffer the relationship between dirty work and emotional exhaustion, which, in turn, affects employee satisfaction (i.e., life, career, and job satisfaction). Self-consciousness is defined as an individual’s awareness of and concern about how they are perceived by others, particularly within social contexts (Morin, Reference Morin2011). This construct suggests that individuals continuously process and interpret external feedback about themselves, often adjusting their behavior to align with perceived social norms.

Employees with higher self-consciousness are more likely to be influenced by external societal cues, requiring them to expend greater personal resources (Demerouti & Bakker, Reference Demerouti and Bakker2023). This increased sensitivity to societal perceptions often leads to emotional exhaustion, as these individuals invest substantial emotional energy in managing how they are perceived by others. Research has highlighted the consequences of heightened self-consciousness; for example, Wicklund (Reference Wicklund1975) found that individuals with higher self-consciousness are more inclined to conform to societal expectations, which can intensify emotional strain as they work to maintain a socially acceptable image. In comparison, individuals with lower self-consciousness tend to exhibit a greater indifference to societal opinions, using this detachment as a protective mechanism to conserve emotional resources and distance themselves from negative external judgments (Wohlers & London, Reference Wohlers and London1989).

We propose that individuals with higher self-consciousness are more vulnerable to experiencing emotional exhaustion in the context of dirty work compared to those with lower self-consciousness. Previous research supports the moderating role of self-consciousness in shaping individuals’ self-perceptions, emotional responses, and behaviors, including their susceptibility to emotional exhaustion. For instance, Pfattheicher and Keller (Reference Pfattheicher and Keller2015) identified a positive relationship between self-consciousness and prosocial behavior, indicating that individuals with higher self-consciousness demonstrate greater concern for societal expectations. Similarly, White et al. (Reference White, Stackhouse and Argo2018) suggested that individuals with heightened self-consciousness are more likely to conform to societal norms, driven by perceived threats to their identity.

In contrast, individuals with lower self-consciousness are less likely to conform to societal expectations, instead prioritizing behaviors that preserve their personal resources (London et al., Reference London, Sessa and Shelley2023; White et al., Reference White, Stackhouse and Argo2018). This suggests that individuals with higher self-consciousness expend more emotional resources to present themselves in ways that align with societal norms, leading to increased emotional exhaustion. Conversely, employees with lower self-consciousness are less susceptible to emotional exhaustion from dirty work, as they are less inclined to allocate additional emotional resources to manage societal perceptions.

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ self-consciousness moderates the negative relationship between dirty work and employee emotional exhaustion, such that the negative relationship is strengthened when employees are higher on self-consciousness and weakened when employees are lower on self-consciousness.

Hypothesis 4: Employees’ self-consciousness moderates the negative indirect relationship between dirty work and (a) life satisfaction, (b) career satisfaction, and (c) job satisfaction through emotional exhaustion, such that the negative relationship is strengthened when employees are higher on self-consciousness and weakened when employees are lower on self-consciousness.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We adhered to best practices for online crowdsourcing to ensure the collection of high-quality data (Peer, Brandimarte, Samat & Acquisti, Reference Peer, Brandimarte, Samat and Acquisti2017) by recruiting participants through Prolific Academic (https://www.prolific.com). Prolific is a widely used crowdsourcing platform that enables researchers to recruit participants from diverse occupational fields. The platform verifies participants’ identities before survey participation by requiring identification information to prevent duplicate accounts and ensure that participants are legitimate, i.e., human (Douglas, Ewell & Brauer, Reference Douglas, Ewell and Brauer2023). Previous studies in organizational science have demonstrated that Prolific provides data quality comparable to that obtained through laboratory studies and other platforms (e.g., Sherf & Morrison, Reference Sherf and Morrison2020; Steed, Dust, Rode & Arthaud‐Day, Reference Steed, Dust, Rode and Arthaud‐Day2023).

Given the specific focus of our research, we conducted a prescreen survey on Prolific to identify participants engaged in occupations that could be classified as “dirty work.” Dirty work encompasses occupations that society perceives as physically, socially, or morally tainted (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999; Kreiner et al., Reference Kreiner, Mihelcic and Mikolon2022). To align with best practices for participant screening (Sharpe-Wessling, Huber & Netzer, Reference Sharpe-Wessling, Huber and Netzer2017), we asked potential participants to respond “Yes” or “No” to whether they perceived their work as physically, socially, or morally tainted, based on Ashforth and colleagues’ definition. Our prescreen survey identified 632 participants who answered “Yes,” and these individuals were subsequently invited to participate in the main study.

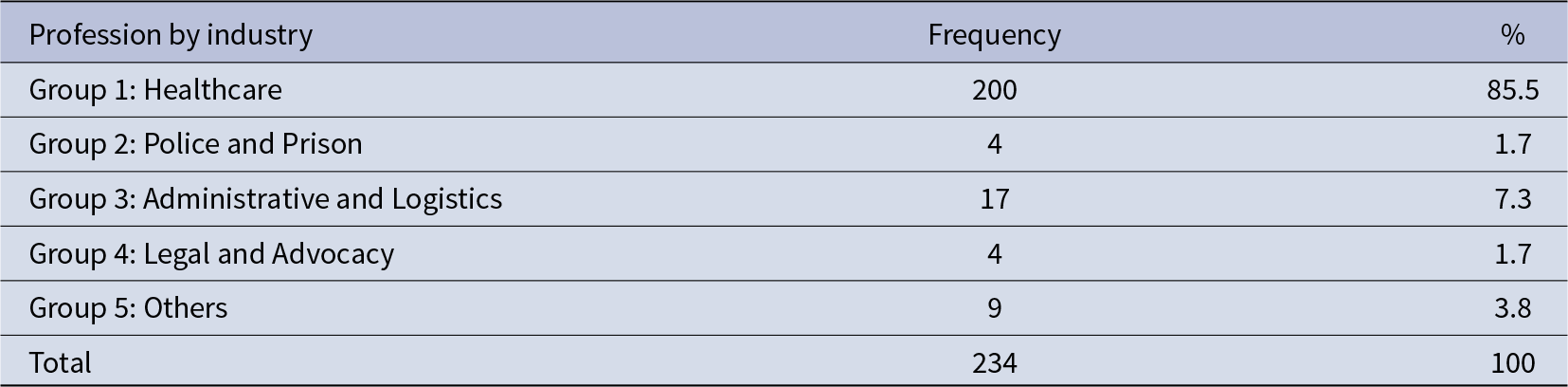

Participants were recruited from the United States and the United Kingdom. The screening question asked, “Do you consider your work physically, socially, or morally dirty?” Individuals who responded “Yes” were invited to complete the Time 1 (T1) survey, followed by a Time 2 (T2) survey four weeks later. To ensure response accuracy and attentiveness, we included two attention-check questions, one at each time point, to verify that participants were not providing random responses (Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012). A total of 292 participants completed the T1 survey, with 250 participants completing the T2 survey, yielding an 86% response rate across both data collection points. The mean age of participants was 41.32 years, and 67% were female. Regarding racial demographics, the majority identified as White (87%), followed by Asian (5.6%), Black/African American (5.1%), Hispanic (1.3%), and Other (1%). Participants represented five industry categories: healthcare, police/prison, administrative and logistics, legal and advocacy, and other (see Table 1). On average, participants reported 10.75 years of experience in their respective professions.

Table 1. Distribution by participants’ industry

MeasuresFootnote 1

Dirty work. At time 1, participants completed the experienced work dirtiness scale (α = .89), a 12-item scale developed by Schaubroeck et al. (Reference Schaubroeck, Lam, Lai, Lennard, Peng and Chan2018). A sample question is, “I had to touch some things that were filthy to do my job.” All variables used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Emotional exhaustion. We measured participants’ emotional exhaustion at T1 using the 9-item emotional exhaustion scale (α = .92) developed by Maslach and Jackson (Reference Maslach and Jackson1981). A sample question is, “I feel emotionally drained from my work.”

Self-consciousness. At T2, participants rated self-consciousness using the three-item public situational self-awareness scale (α = .78) developed by Govern and Marsch (Reference Govern and Marsch2001). A sample question is, “I am concerned about what other people think of me.”

Life satisfaction. At T2, participants completed Diener et al.’s (Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985) five-item satisfaction with life scale (α = .90). A sample question is “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.”

Career satisfaction. At T2, participants completed the Greenhaus, Parasuraman and Wormley (Reference Greenhaus, Parasuraman and Wormley1990) five-item career satisfaction scale (α = .94). A sample question is “I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career.”

Job satisfaction. At T2, participants rated their job satisfaction using Cammann et al.’s (Reference Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins and Klesh1979) three-item scale (α = .95). A sample question is “All things considered, I am satisfied with my current job.”

Analytical approach

We tested the statistical significance of the direct (H1) and indirect effects (H2) of dirty work using a bootstrap resampling method, employing Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro with 5,000 bootstrap samples. To evaluate the moderating role of self-consciousness on the relationship between dirty work and emotional exhaustion (H3), as well as the moderated mediation effects (H4), we again used the PROCESS macro with bootstrap resampling to assess whether the indirect effects of dirty work on the satisfaction variables were contingent on lower and higher levels of self-consciousness. Specifically, we regressed emotional exhaustion on dirty work, self-consciousness, and the interaction term between dirty work and self-consciousness. We then regressed the satisfaction variables on a set of predictors, including dirty work, emotional exhaustion, the dirty work × self-consciousness interaction, and self-consciousness. Lastly, we calculated bias-corrected confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects of dirty work on the satisfaction variables through emotional exhaustion using 5,000 bootstrap resamples. The study materials, data, syntax, and output can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF) here: https://osf.io/dtjeh/?view_only=72158556cb8049d5b2fb2b0996cd5ad2.

Results

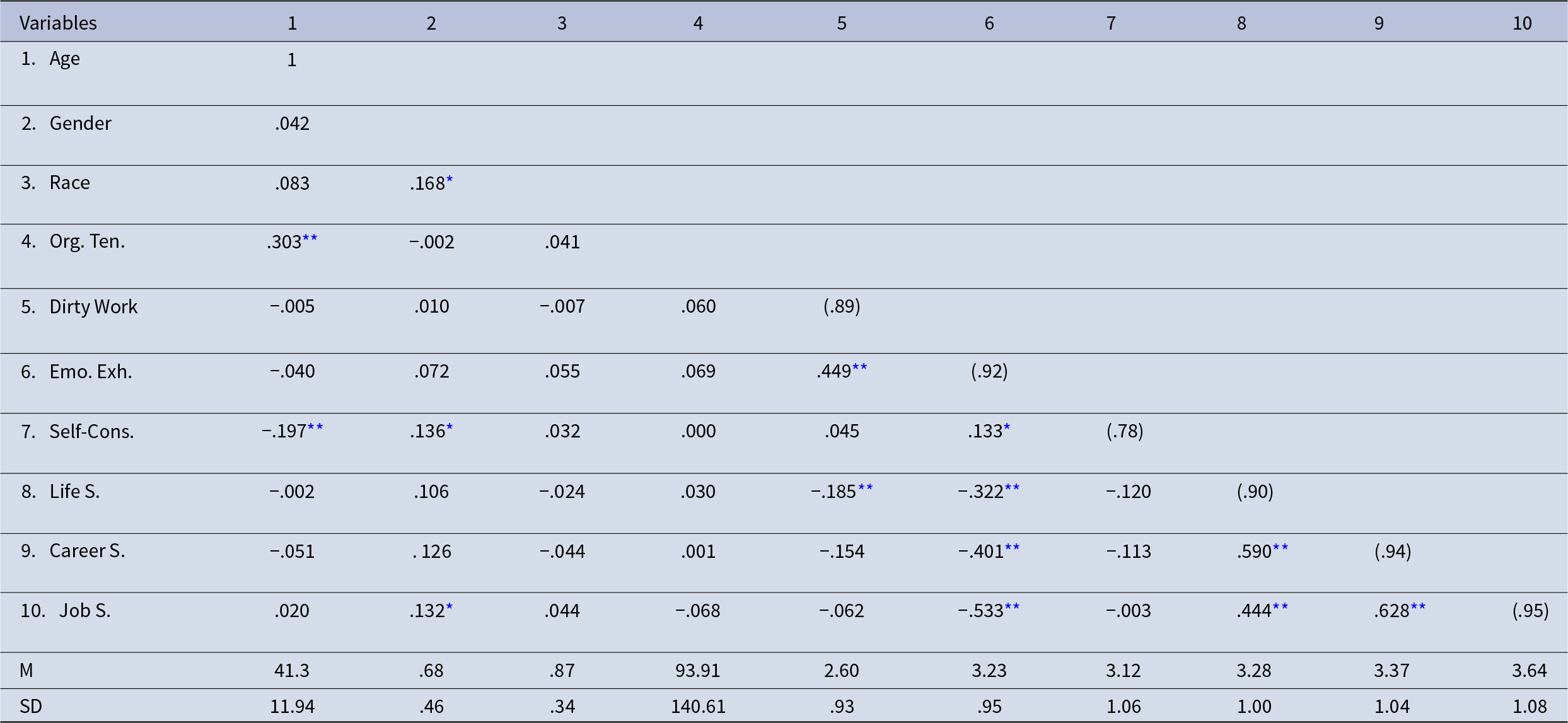

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to ascertain whether the expected factor structure fit our model. We found that our six-factor model fit the data reasonably well, except for a relatively low CFI (χ2(614) = 1295.70, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.89). This model offered superior model fit compared to a four-factor model combining job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and career satisfaction (χ2(623) = 2295.12, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.73, Δχ2(9) = 999.42, p < .001) and a five-factor model combining dirty work and emotional exhaustion (χ2(619) = 2070.58, p < .01, RMSEA = .10, CFI = 0.76, Δχ2(5) = 774.88, p < .001). We also calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) to help determine the variance explained by each latent construct (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). According to Gefen and Straub (Reference Gefen and Straub2005), adequate discriminant validity exists when the statistics of the square root of the AVE from each construct exceed the zero-order correlations between the latent constructs. Indeed, the square root of each construct AVE (dirty work = .68; emotional exhaustion = .75; PSSA = .75; life satisfaction = .81; career satisfaction = .87; job satisfaction = .93) is greater than the highest bi-variate correlation among our latent constructs (r = .62), suggesting discriminant validity.

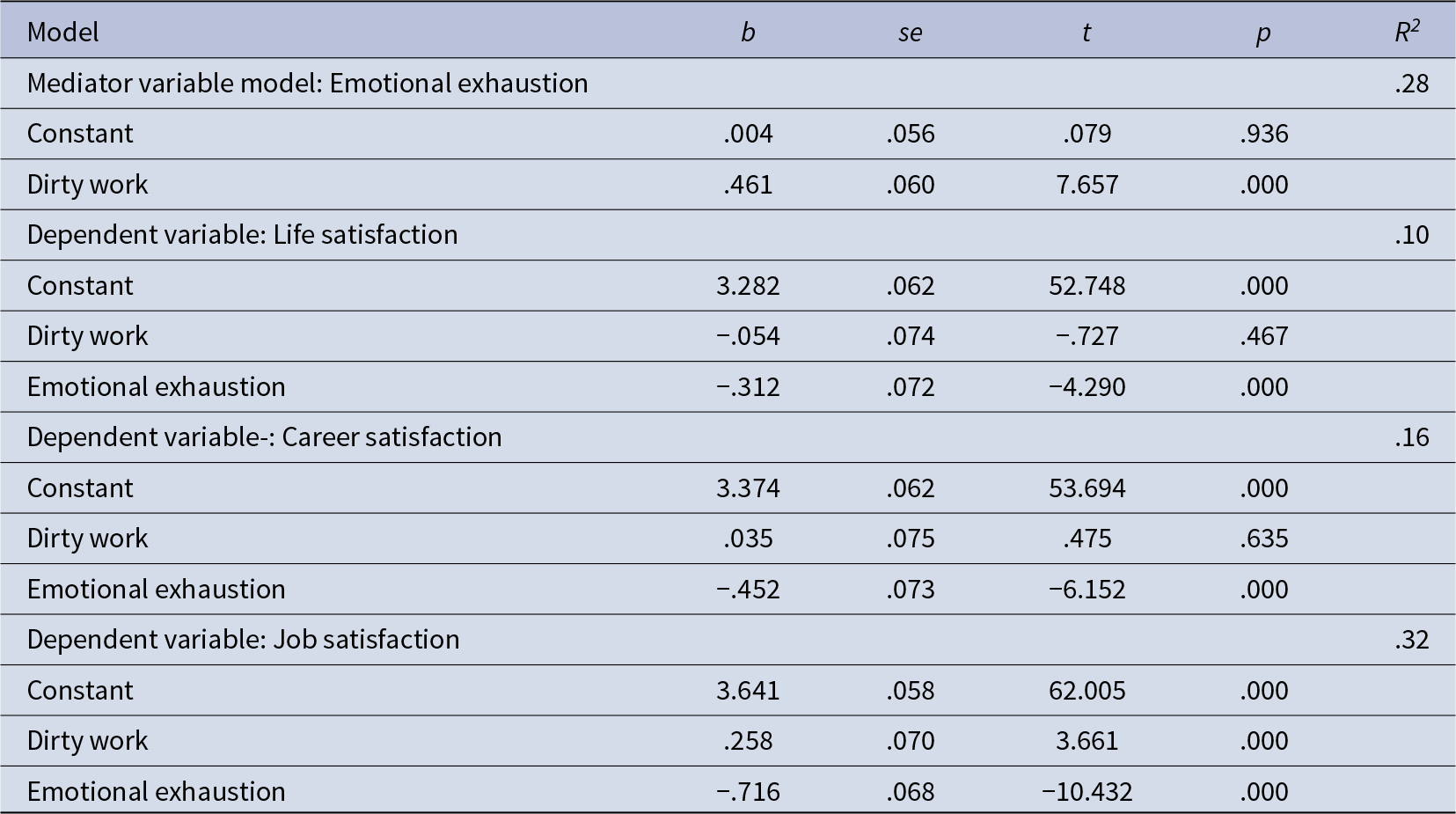

Table 2 illustrates the zero-order correlations for all the constructs in our study. In support of hypothesis 1, the results revealed a significant positive relationship between dirty work and emotional exhaustion (b = .461, p < .01; ΔR 2 = .20). In support of hypothesis 2, the results indicate significant negative relationships between emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction (b = −.312, p < .01; ΔR 2 = .10), career satisfaction (b = −.452, p < .05; ΔR 2 = .16), and job satisfaction (b = −.716, p < .05; ΔR 2 = .32). Additionally, our findings indicate a significant indirect effect of dirty work on life satisfaction (b = −.144 [−.232, −.063]), career satisfaction (b = −.209 [−.312, −.122]), and job satisfaction (b = −.331 [−.442, −.230]) via emotional exhaustion. Thus, hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c were supported (see Table 3).

Table 2. Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics

Note: N = 234. Org. Ten = organizational tenure; Emo. Exh. = emotional exhaustion; Self-Cons. = self-consciousness; Life S. = life satisfaction; Career S. = career satisfaction; Job S. = job satisfaction; Gender (Female = 1); Race (White = 1; Others = 0); M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. Cronbach’s alphas are shown in parentheses on the diagonal.

* p < .05; **p < .01.

Table 3. Regression analyses – dirty work, emotional exhaustion, and satisfaction

Note: N = 234. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. 95% CI. p < .05; p < .01.

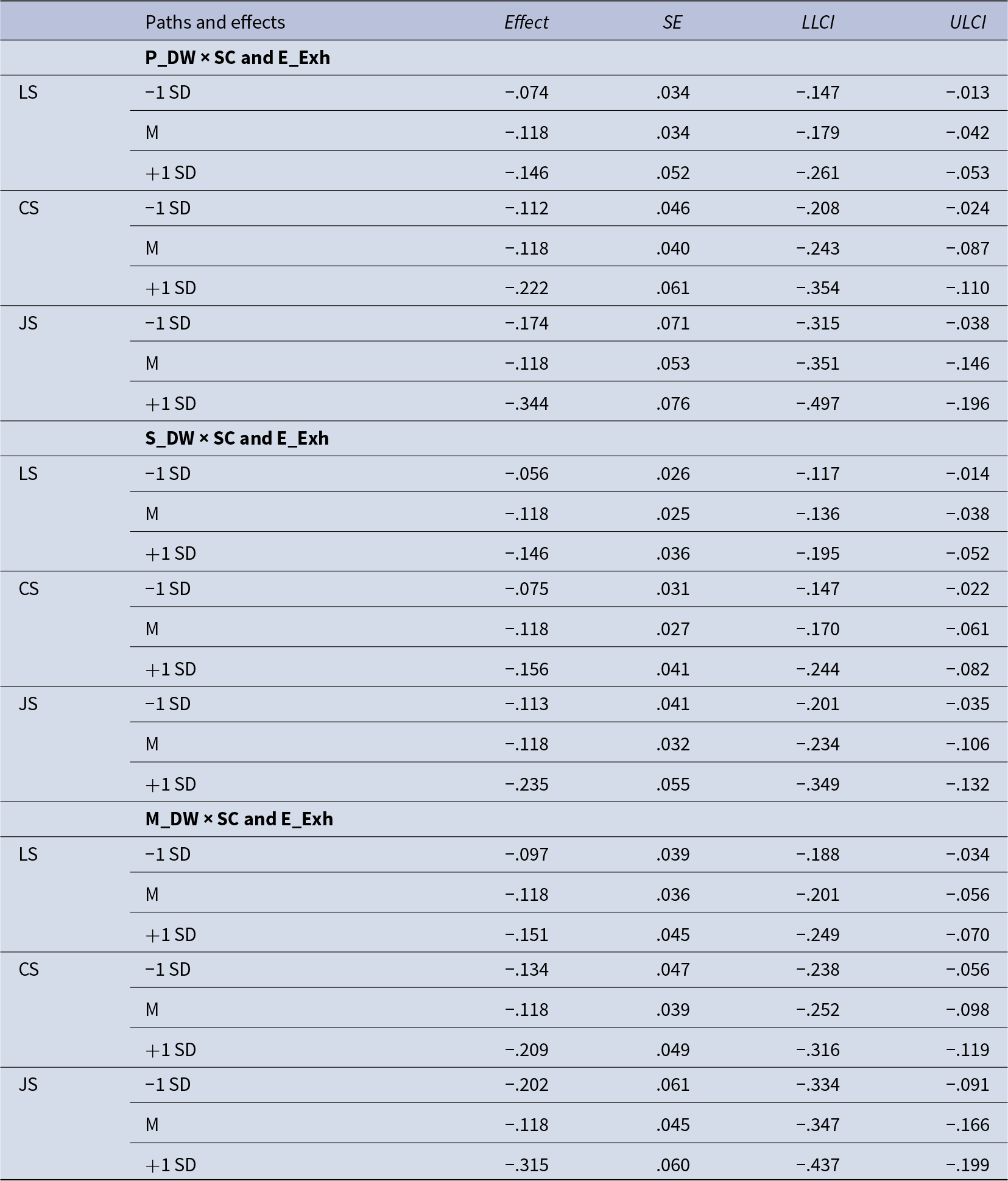

In support of hypothesis 3, our findings illustrate a significant interaction between dirty work and self-consciousness on emotional exhaustion (b = .111, p < .05 ΔR 2 = .22) (see Table 4). The results of the moderation plot revealed that dirty work was more strongly related to employee emotional exhaustion when employees’ self-consciousness was higher (b = .587, t = 6.71, p < .01) than when it was lower (b = −.327, t = 3.77, p < .01). This analysis provides support for hypothesis 3. Furthermore, our analyses support hypothesis 4, with the impact of dirty work through emotional exhaustion on life satisfaction (lower = b = −.102 [−.193, −.035] higher = b = −.183 [−.294, −.081]), career satisfaction (lower = b = −.148 [−.260, −.062] higher = b = −.265 [−.399, −.149]), and job satisfaction (lower = b = −.235 [−.380, −.108] higher = b = −.420 [−.578, −.274]) being stronger when self-consciousness was higher and weaker when self-consciousness was lower (see Table 5; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Self-consciousness moderating the relationship between dirty work and emotional exhaustion.

Table 4. Regression analyses – dirty work, emotional exhaustion, satisfaction, and self-consciousness

Note: N = 234. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. 95% CI. p < .05; p < .01.

Table 5. Regression analyses – dirty work, emotional exhaustion, and satisfaction

Note: N = 234. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size = 5,000. SC = Self-consciousness, DW = dirty work, EE = emotional exhaustion, LS = life satisfaction, CS = career satisfaction, JS = job satisfaction. LLCI = lower-level confidence interval. ULCI = upper-level confidence interval.

Supplemental analyses

We conducted supplemental analyses to confirm the robustness and accuracy of our findings. First, we investigated four different controls to assess their impact on our results: age, gender, race, and organizational tenure. Prior research suggests that these controls can influence the degree of employees’ emotional exhaustion (Dust, Resick, Margolis, Mawritz & Greenbaum, Reference Dust, Resick, Margolis, Mawritz and Greenbaum2018; Marquez, Katsantonis, Sellers & Knies, Reference Marquez, Katsantonis, Sellers and Knies2023; Schermuly & Meyer, Reference Schermuly and Meyer2016) and subsequent behavior (Ng & Fieldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2010; Wisse, van Eijbergen, Rietzschel & Scheibe, Reference Wisse, van Eijbergen, Rietzschel and Scheibe2018). None of the controls had a statistically significant impact on emotional exhaustion (age: b = −.001, p = .798; gender: b = .083, p = .493; race: b = .156, p = .342; organizational tenure: b = .000, p = .570). Additionally, the majority of our findings remain the same, and all hypotheses continue to be supported when controlling for age, race, or organizational tenure. However, the interaction effect falls slightly out of the traditional threshold for significance when controlling for gender (b = .107; p = .052), but the conditional effects remain statistically significant (lower: .332, LLCI = .161, ULCI = .504; higher: .582, LLCI = .409, ULCI = .755) (see online supplemental analyses for output).

Second, we separately test each dimension of dirty work (physically, socially, and morally tainted) highlighted by prior dirty work scholars (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999; Hughes, Reference Hughes1958). The findings remain the same when each dimension of dirty work is evaluated separately. Specifically, all three dimensions of dirty work showed a significant impact on emotional exhaustion (physical: b = .393, p < .001; social: b = .256, p < .001; moral: b = .376, p < .001). See Table 6 for further details. Similarly, the indirect effect of physical dirty work on life satisfaction (b = −.110 [−.187, −.045]), career satisfaction (b = −.168 [−.255, −.092]), and job satisfaction (b = −.260 [−.367, −.156]); social dirty work on life satisfaction (b = −.085 [−.142, −.039]), career satisfaction (b = −.114 [−.176, −.065]), and job satisfaction (b = −.172 [−.243, −.110]); and moral dirty work on life satisfaction (b = −.127 [−.209, −.059]), career satisfaction (b = −.175 [−.261, −.103]), and job satisfaction (b = −.264 [−.360, −.179]) remains statistically significant. Lastly, the moderating effect of self-consciousness on each dimension of dirty work on emotional exhaustion remained statistically significant for social (b = .077, p = .046), but not for physical (b = .110, p = .082) or moral (b = .069, p = .141) forms of dirty work (Table 7 provides further details). See the future research section for an interpretation and discussion of these differences. Results available on OSF here: https://osf.io/dtjeh/?view_only=72158556cb8049d5b2fb2b0996cd5ad2).

Table 6. Results of the direct and indirect path analysis (H1 & H2)

Note: P_DW = Physical dirty work; S_DW = Social dirty work; M_DW = Moral dirty work; E_Exh = Emotional exhaustion; SC = Self-consciousness; LS = Life satisfaction; CS = Career satisfaction; JS = Job satisfaction.

Table 7. Results of the moderated-mediation path analysis (H3 & H4)

Note: P_DW = Physical dirty work; S_DW = Social dirty work; M_DW = Moral dirty work; E_Exh = Emotional exhaustion; SC = Self-consciousness; LS = Life satisfaction; CS = Career satisfaction; JS = Job satisfaction. NS = Not significant.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that dirty work has a negative downstream impact on life satisfaction, career satisfaction, and job satisfaction through emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, employees who are highly attuned to societal perceptions (i.e., those with higher self-consciousness) experience greater emotional exhaustion stemming from dirty work compared to those less concerned with societal views. These findings offer several theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

Our study offers several theoretical contributions to the literature on dirty work. First, our findings indicate that employees’ self-consciousness acts as a critical boundary condition, shaping the extent to which dirty work contributes to emotional exhaustion. Specifically, employees who are less concerned with societal perceptions of their occupation are less likely to experience emotional exhaustion, thereby mitigating its negative effects on life, career, and job satisfaction. This aligns with Chon and Sitkin’s (Reference Chon and Sitkin2021) observation that employees highly sensitive to others’ perceptions tend to experience heightened emotional exhaustion. Conversely, individuals with lower self-consciousness, who are less influenced by societal opinions, exhibit a reduced propensity for emotional exhaustion, underscoring the importance of individual differences (Scheier et al., Reference Scheier, Buss and Buss1978). Chon and Sitkin (Reference Chon and Sitkin2021) further suggest that these individual differences play a significant role in shaping attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (White et al., Reference White, Stackhouse and Argo2018), particularly in relation to job satisfaction and overall well-being. This appears to be particularly true with respect to dirty workers.

Second, our study provides empirical evidence that employees engaged in dirty work experience heightened job demands, which contribute to emotional exhaustion. This finding aligns with prior research showing that job-related demands and the psychological distress associated with certain tasks contribute to employees’ emotional depletion (Thompson, Carlson, Kacmar & Vogel, Reference Thompson, Carlson, Kacmar and Vogel2020). Negative emotions can also arise when employees perceive their occupational identities as a source of psychological discomfort (Kira & Balkin, Reference Kira and Balkin2014), especially when societal perceptions of their work are stigmatizing. According to Bakker and Demerouti (Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007), the JD-R model posits that elevated emotional demands associated with one’s job deplete psychological resources, leading to exhaustion and fatigue (Halbesleben & Buckley, Reference Halbesleben and Buckley2004). The JD-R model further emphasizes that mental, emotional, and physical job demands are primary contributors to job strain and burnout (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007; Ho, Reference Ho2024). This is supported by empirical evidence linking job demands to emotional exhaustion (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Sanz-Vergel2023; Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001; Huang, Lin & Lu, Reference Huang, Lin and Lu2020). Despite these insights, limited research has explored how societal perceptions of dirty work contribute to emotional exhaustion. Our findings extend prior theoretical work by showing that individuals engaged in dirty work are more likely to experience resource depletion in the form of emotional exhaustion.

Finally, our study makes a methodological contribution by providing quantitative evidence through survey design, addressing calls for more rigorous quantitative studies in the dirty work literature (Fowler, Reference Fowler2013; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Quantitative surveys help reduce social desirability bias and enable clearer interpretations of complex phenomena, offering precision that complements the insights gained from qualitative approaches. Existing qualitative studies predominantly examine the “process” of dirty work, often leaving gaps in understanding the causal relationships between dirty work and its effects on employee attitudes and behaviors. This research responds to Ashforth et al.’s (Reference Ashforth, Kreiner, Clark and Fugate2017) call for more quantitative approaches in dirty work studies, as the field remains dominated by qualitative methodologies, such as interviews (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Kreiner, Clark and Fugate2017; Bosmans et al., Reference Bosmans, Mousaid, De Cuyper, Hardonk, Louckx and Vanroelen2016; Shepherd et al., Reference Shepherd, Maitlis, Parida, Wincent and Lawrence2022), ethnography (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin2019; Sanders, Reference Sanders and Hillyard2010; Shigihara, Reference Shigihara2018), and case studies (Grandy & Mavin, Reference Grandy and Mavin2014; Mavin & Grandy, Reference Mavin and Grandy2013). By joining the limited body of quantitative research in this area (Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Lam, Lai, Lennard, Peng and Chan2018; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang and Li2023), our study offers significant theoretical contributions, expanding the methodological scope and deepening our understanding of how dirty work impacts employees’ emotional resources and overall satisfaction.

Practical implications

While our study provides substantial theoretical contributions to understanding the dynamics of dirty work, it also identifies practical implications to assist individuals, supervisors, and organizations in managing the challenges posed by job demands in dirty professions. These strategies can help employees preserve valuable resources while effectively navigating their responsibilities. First, our findings indicate that employees in dirty work occupations are prone to emotional exhaustion due to societal perceptions of their roles. To mitigate this, organizations and managers should ensure the availability of sufficient job resources, such as support structures and organizational frameworks, to reduce stigma and help employees manage the emotional toll of dirty work. In turn, this can improve employee and organizational well-being. Research has shown that emotionally exhausted employees not only lose personal resources but also contribute to broader resource depletion within organizations (Lebrón, Tabak, Shkoler & Rabenu, Reference Lebrón, Tabak, Shkoler and Rabenu2018). As a solution, we recommend providing employees with psychological coping strategies through coaching, training, and empowerment initiatives (Gutierrez, Reference Gutierrez1994; Hess, Reference Hess1984) to better manage job demands and allocate their resources effectively.

Second, our study highlights that self-consciousness can amplify the negative effects of dirty work and emotional exhaustion. To address this, organizations and managers should support employees in reframing how they perceive societal views of their profession. This reframing can lessen the emotional toll associated with dirty work. Organizations can achieve this by implementing initiatives that emphasize the critical contributions made by employees in these roles, rather than allowing the “dirty work” label to dominate perceptions. Allocating resources to positively reshape employees’ understanding of their roles and professions can foster resilience and improve employee well-being.

Limitations and future research

Despite the strengths outlined above, our study is not without limitations. First, dirty work and emotional exhaustion were measured at a single time point (Time 1), which may lead to inflated responses or biases due to common method variance (Podsakoff, Podsakoff, Williams, Huang & Yang, Reference Podsakoff, Podsakoff, Williams, Huang and Yang2024). Future research should address this limitation by measuring these variables at different time points to reduce potential biases. Employing longitudinal designs would also allow researchers to examine temporal changes in the experience of dirty work and emotional exhaustion over time, as well as explore whether temporal factors influence employees’ perceptions.

Second, our sample included participants from various professions and industries, which may have introduced variability in how dirty work is perceived, such as among police officers, correctional officers, firefighters, exotic dancers, and butchers. Our supplemental analyses indicate that each dimension of dirty work (i.e., physical, moral, and social) exhibits a similar pattern to the latent construct. However, self-consciousness only moderated the direct effect of social forms of dirty work on emotional exhaustion, and not the direct effect of physical and moral forms of dirty work. This might suggest that individuals high in self-consciousness are particularly sensitive to how they are perceived by others, making them more vulnerable to the interpersonal and reputational implications of socially tainted work (Ashforth & Kreiner, Reference Ashforth and Kreiner1999). Social taint often involves stigma derived from societal judgment (e.g., association with deviant or marginalized groups), which may trigger heightened self-awareness and concern about external evaluation. In contrast, physical and moral taint are more related to the nature of the tasks (e.g., dealing with dirt or death, or performing ethically questionable tasks) and may not evoke the same degree of social scrutiny, thus failing to activate self-consciousness to the same extent in predicting emotional exhaustion. We encourage future studies to test our model within a broader set of industries, using these dimension-specific constructs to generate a deeper level understanding and a more generalizable investigation of this phenomenon.

Finally, our study examined self-consciousness in a sample comprising employees from the United States and the United Kingdom, both of which are individualistic cultures. This aligns with research suggesting that people in individualistic cultures place less emphasis on societal perceptions and focus more on self-concept (Markus & Kitayama, Reference Markus, Kitayama, Arnold, Altbach and King2014), making them less concerned with societal views of their engagement in dirty work. In contrast, individuals in collectivistic cultures, such as those in Asia and Africa, are more likely to consider environmental and societal perceptions (Roberts, Bareket-Shavit, Dollins, Goldie & Mortenson, Reference Roberts, Bareket-Shavit, Dollins, Goldie and Mortenson2020). Consequently, individuals in collectivistic cultures might exhibit higher levels of self-consciousness, potentially amplifying the negative effects of dirty work on emotional exhaustion. Future research should include samples from collectivistic cultures to investigate how cultural differences may serve as boundary conditions for the effects of dirty work.

Conclusion

We propose that employees in professions categorized as “dirty work” are particularly vulnerable to emotional exhaustion due to the social stigmatization associated with their roles. Our findings indicate that employees with lower self-consciousness possess a critical personal resource that helps them mitigate the emotional toll of their profession. We hope that this work stimulates further research into the unique challenges and beneficial characteristics required to succeed in necessary yet socially stigmatized professions.

Appendix

Survey questionnaire

Experienced Dirty Work

1. I had to do something I considered immoral or unethical.P

2. I encouraged someone to do something that was not in his or her best interest.P

3. I had to do something that I thought was deceptive or misleading.P

4. I had to invade someone’s privacy.P

5. I had to touch some things that were filthy to do my job.S

6. I had to do some things I found physically disgusting.S

7. I had to work in physically unpleasant surroundings.S

8. I had to do things that presented a danger to my health (i.e., physical danger or risk of illness).S

9. I had to behave like a servant to other people.M

10. I had to interact with people who have a questionable background.M

11. I had to tolerate being treated abusively by others (e.g., customers, coworkers, or bosses).M

12. I had a strong opinion but felt I should not express it in front of others.M

Note: P = Physically tainted; S = Socially tainted; M = Morally tainted

Emotional Exhaustion

1. I feel emotionally drained from my work

2. I feel used up at the end of the workday

3. I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job

4. Working with people all day is really a strain for me

5. I feel burned out from my work

6. I feel frustrated by my job

7. I feel I’m working too hard on my job

8. Working with people directly puts too much stress on me

9. I feel like I’m at the end of my rope

Life Satisfaction

1. In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.

2. The conditions of my life are excellent.

3. I am satisfied with my life.

4. So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life.

5. If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.

Career Satisfaction

1. I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career.

2. I am satisfied with the progress I have made toward meeting my overall career goals.

3. I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting my goals for income.

4. I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting my goals for advancement.

5. I am satisfied with the progress I have made in meeting my goals for the development of new skills.

Job Satisfaction

1. All in all, I am satisfied with my job.

2. In general, I like working here.

3. All things considered; I am satisfied with my current job.

Self-Consciousness

1. I am concerned about the way I present myself.

2. I am self-conscious about the way I look.

3. I am concerned about what other people think of me.