Introduction

Eating more than 400 g of fruit and vegetables has been a key component of global population dietary guidance for the prevention of chronic diseases for more than 30 years.(1) However, average intakes remain below the recommendation(Reference Kalmpourtzidou, Eilander and Talsma2–Reference Woodside, Nugent, Moore and McKinley4) and have a clear social gradient.(Reference Maguire and Monsivais5–Reference Mayen, Marques-Vidal, Paccaud, Bovet and Stringhini8)

In the UK, the 400 g goal was pragmatically translated into advice to consume at least five 80 g portions of different fruit and vegetables a day, and the government’s nutrition task force produced guidance on what was included.(Reference Williams9) Globally, recommendations are similar with portion sizes between 80 and 100 g, although there is some cultural and contextual variation on the inclusion of vegetables such as potatoes and sweetcorn.(Reference Woodside, Nugent, Moore and McKinley4,Reference Salesse, Eldridge, Mak and Gibney10) WHO’s 400 g/day goal is a ‘lower limit population goal’, and the public-facing message has always been to eat ‘at least’ 5-a-day. The evidence in favour of plant-based diets with high proportions of fruit and vegetables continues to grow,(Reference Onni, Balakrishna and Perillo11) with some studies suggesting benefits of 600–800 g/day.(Reference Alissa and Ferns12,Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta13) The 2019 Lancet Eat commission looked at healthy diets in the context of planetary health and included 300 g of vegetables and 200 g of fruit in its healthy reference diet,(Reference Willett, Rockstrom and Loken14) equivalent to around six portions. Several high-income countries now recommend at least 7 portions or 500 g or more, with specific emphasis that half or more should come from vegetables, including Australia, Denmark, Germany, Finland, and Iceland.(15,16) The UK’s 2016 national food-based dietary guideline, the Eatwell Guide, represents recommended intakes of approximately 550 g/day, equivalent to around four portions of vegetables and three of fruit.(Reference Scarborough, Kaur and Cobiac17,18)

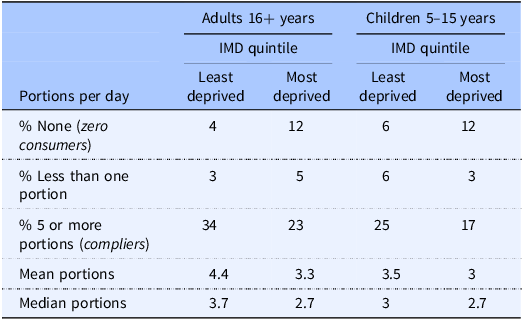

The launch of a ‘5-a-day’ campaign in the UK in 2003 raised the profile of the advice, and it is widely known.(Reference Appleton, Krumplevska, Smith, Rooney, McKinley and Woodside19) Survey data show a steady increase in adult ‘5-a-day’ compliers from 24% in 2001 to 34% in 2022; however, there has been no change in the zero/less than one portion consumers (11%), and differences between income groups remain (Table 1).(20) As public health emphasis on the benefits of vegetables and plant-based diets has strengthened, the social gradient between high and low vegetable consumers risks increasing, exacerbated by the cost-of-living crisis.(21,Reference Hoenink, Beulens and Harbers22)

Table 1. Comparison of fruit and vegetable consumption by the highest and lowest index multiple deprivation (IMD). Data source: Health Survey for England, 2022, Part 1(20)

Many studies identify the price of vegetables as a key barrier for households on a low income,(Reference Mackenbach, Brage, Forouhi, Griffin, Wareham and Monsivais23–Reference Miller, Yusuf and Chow25) and there is a widely documented association between low income and low purchase.(Reference French, Tangney, Crane, Wang and Appelhans26) However, price or availability are not the only barriers or necessarily the most impactful. Other studies have noted a correlation of intakes with education independently of income.(Reference Maguire and Monsivais5,Reference French, Tangney, Crane, Wang and Appelhans26) There is some evidence that those who eat the least vegetables perceive them as being less available(Reference Williams, Ball and Crawford27) or have low knowledge or familiarity with vegetables(Reference Bel-Serrat, von der Schulenburg, Marques-Previ, Mullee and Murrin28) compared with higher consumers.

Understanding current practice is essential to designing effective public health interventions,(Reference Brug29) and from a social justice perspective, this includes understanding practice in the sectors of society known to face the biggest challenges.(Reference Wallack30) In common with other high-income countries, the majority of food purchases in the UK are from supermarkets. This study sought to better understand the determinants of the current vegetable food choice of parents with limited funds for grocery shopping, in an area of multiple deprivation in the Southeast of England. It was designed to assist local implementers of a national vegetable promotion programme, the ‘Peas Please’ initiative, which worked with retailers and other partners across the food system with the aim of making it easier for everyone to eat more vegetables.(21)

Methods

Design

Much of the discourse examining dietary practices in low-income groups takes a deficit model such as examining barriers to eating more healthily. In contrast, this study used an assets-based framing, which starts with understanding current vegetable choices. Asset-based perspectives seek to understand existing positive health practices so that health promotion interventions can be designed with an appreciation of the existing strengths of individuals or communities.(Reference Rippon and Hopkins31) A qualitative study was conducted using focus group discussions (FGD) to explore how parents choose, buy, store, cook, serve, and eat the vegetables they do. Participatory techniques were incorporated to elicit parents’ views and encourage the development of shared narratives. A short, structured questionnaire was used to collect demographic information. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Brighton’s School of Health Sciences Research and Ethics panel 13042018. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants and recruitment

The study recruited parents or carers with children under 18 years regularly living with them, self-identified as ‘shopping on a budget’, and shopped in the local discount supermarket in one of the 10% most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK in the Southeast of England. Eligible participants had to understand and speak English. Recruitment took place between April and June 2018 using posters, flyers, and active on-site recruitment by the research team in the supermarket, at primary and nursery school gates at collection times, and in a local community youth centre. All participants received information about the study before providing informed consent and received a £20 shopping voucher as recompense for their time.

Data collection and analysis

FGDs took approximately 1.5 hrs and were held in quiet private rooms at three local community venues selected for being neutral non-official premises in different parts of the neighbourhood. The moderator was author 1 and facilitator author 2, who are both trained in qualitative research techniques. Each FGD was audio recorded and began with icebreaker questions about children’s favourite meals. One of every fresh vegetable and salad item on sale in the local discount supermarket on the day of the FGD (approximately forty items) and a selection of common canned vegetables, were laid out on a central table, alongside a supermarket basket. Participants were asked to identify which vegetables they ate regularly and would be annoyed if they forgot to buy when doing a food shop. Each vegetable was discussed in depth and placed into the basket. The discussion then moved onto vegetables used less often, rarely, or never, using three A4-size colour photographs of vegetables in the freezer cabinet and in-store displays as prompts as appropriate. Specific probes about cooking and preparation, special offers, and frozen vegetables were raised as needed. The vegetables in the room helped create a friendly, exploratory, and non-judgemental environment. The FGD topic guide was used flexibly to allow participants’ interests and interactions to steer the discussion.

Data were stored securely using password-protected General Data Protection Regulation-compliant cloud storage. Participants were allocated unique and anonymous participant numbers. Recordings were transcribed and checked by members of the research team, with one exception, which was transcribed by an external university-approved supplier. Thematic analysis was used to inductively code and analyse the data using a six-stage process as outlined in Braun and Clarke.(Reference Braun and Clarke32) Transcripts were iteratively read and coded using qualitative data software (NVivo) to support the process. Initially 80+ codes were generated; these were reviewed, refined, and clustered into themes and sub-themes through recursive re-reading, mapping, and defining themes. Themes were generated by author 1 and reviewed by authors 2 and 3 in relation to the general pool of codes and the entire data set.

Results

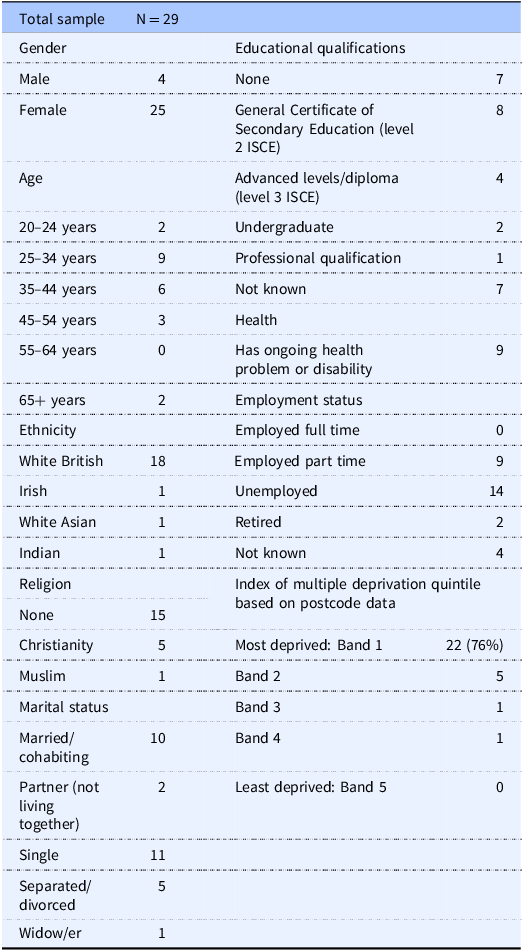

Five focus groups with four to eight participants and one in-depth interview (due to non-attendance) were conducted with a total of twenty-nine participants. After sequential analysis of the first five FGDs, no new themes emerged, and recruitment was stopped. Study participants were mostly white British, aged between 25 and 44 years, unemployed or in part-time employment, and with qualifications of lower secondary education (General Certificate of Secondary Education) or below (Table 2). Analysis of postcode data by index of multiple deprivation (IMD) indicated that 76% of participants lived in areas in the lowest quintile of deprivation. Of the 29 parents or carers in the study, 14 had one child (48%), 6 two children (21%), and 9 three children (31%) under 18 years regularly living with them. The term ‘parent’ or ‘participant’ is used throughout this paper to denote the main carer responsible for decision-making around family food. Where terms have been generated during the analysis to summarise participants’ conceptualisations or perceptions, these are in italics, and italics and quotation marks when arising from verbatim comments.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants

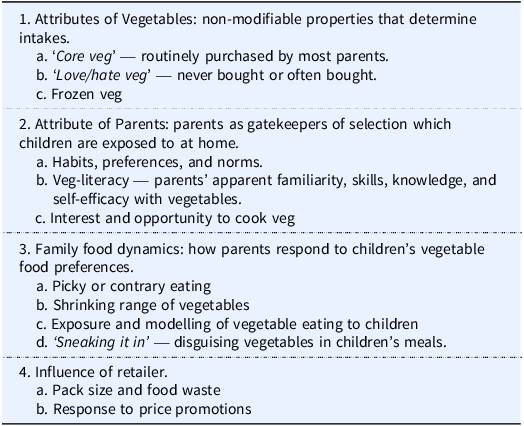

Identified themes

The findings have been clustered into four broad emergent themes reflecting distinct areas for consideration when designing vegetable promotion interventions: attributes of vegetables, attributes of parents, family food dynamics, and influence of the retailer (Table 3). Representative examples of participant quotes for each sub-theme are shown in Tables 4–7, identified as M, F, GM, or GF for mother, father, grandmother, and grandfather, respectively. The first digit indicates the focus group; thus, M15 is mother, number 5 in focus group 1, and MI for the individual interview.

Table 3. Summary of themes and sub-themes. Verbatim terms from the focus group discussion in italics

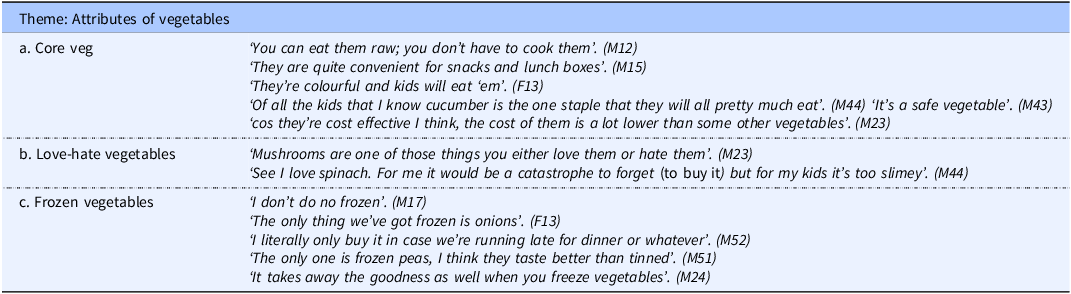

Table 4. Theme: Attributes of vegetables, sub-themes, and illustrative quotes

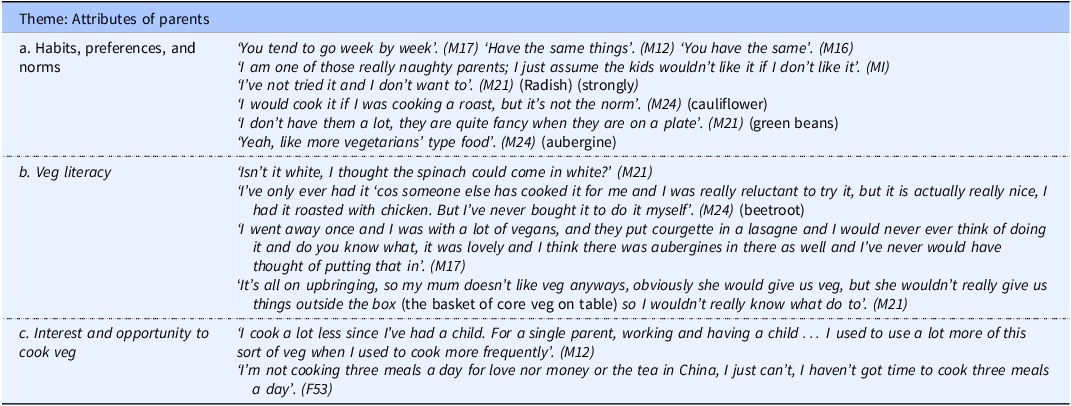

Table 5. Theme: Attributes of parents, sub-themes, and illustrative quotes

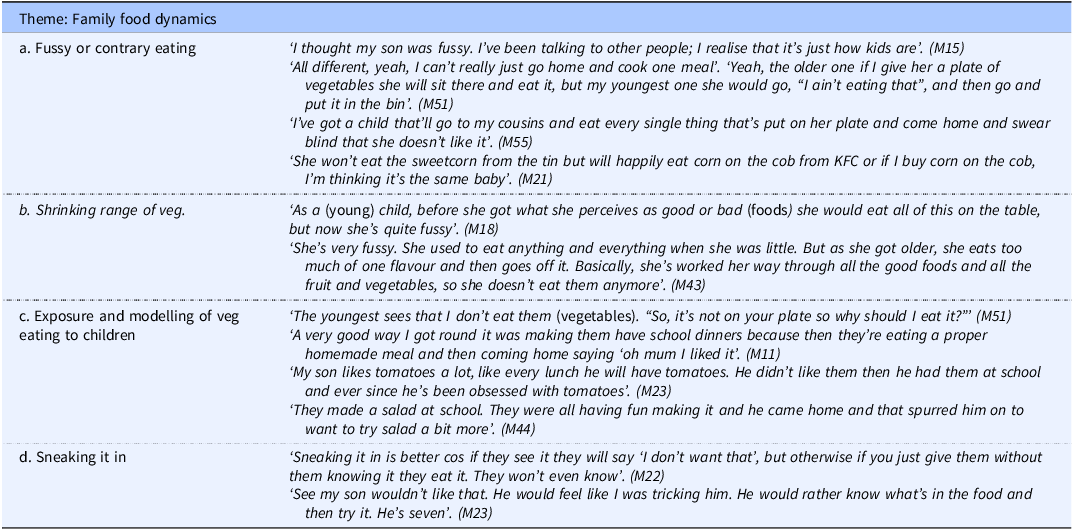

Table 6. Theme: Family food dynamics, sub-themes, and illustrative quotes

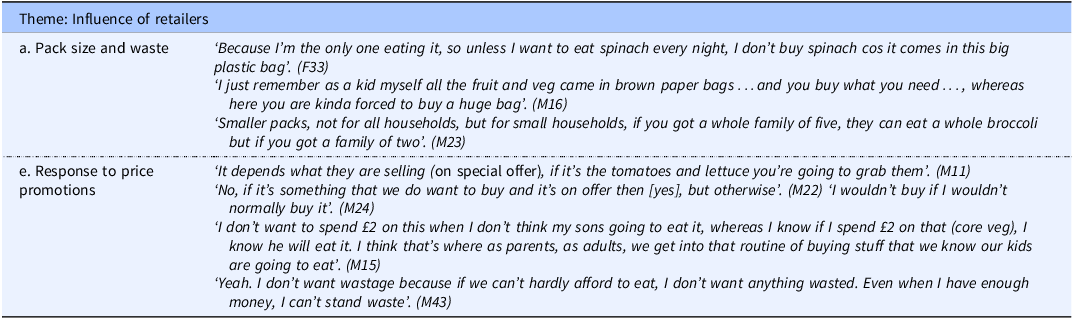

Table 7. Theme: Influence of retailers, sub-themes, and illustrative quotes

Attributes of vegetables

Participants’ views and experiences of the intrinsic properties of vegetables are presented as a separate theme because these characteristics are not readily modifiable and vegetable promotion interventions need to build on those aspects that favour consumption.

a) ‘Core veg’: There was broad agreement on the essentiality of seven or so ‘core veg’ that nearly all participants considered as their ‘veg necessities’. Participants identified several key characteristics of these ‘core veg’, which meant they were routinely purchased: they are ‘dual use’, most can be eaten cooked or raw; multipurpose — they can be used in salads, sandwiches, lunchboxes, snacks, or meals; they are easy to prepare; and were constructed as ‘safe’ because children will eat them. The ‘core veg’ identified were carrots, tomatoes, cucumber, peppers, onion, broccoli, tinned sweetcorn, and for those that ate them, mushrooms, and salad. These were considered cheaper than other vegetables although this did not necessarily reflect the actual prices; rather, participants spoke of ‘core veg’ being used daily and having a high ‘turn around’ so they were perceived as ‘cost effective’ because they were easy to fully use.

b) ‘Love/Hate veg’: Some vegetables provoked a divided response and were strongly disliked, avoided, and never purchased by some participants, while considered easy to eat and regularly bought by others. Reasons for rejection were dislike of a distinctive flavour (beetroot ‘too earthy’, celery, radish) or aversion to a ‘slimy’ texture (avocados, aubergines, mushrooms). For those parents who disliked these ‘love/hate’ vegetables, the sentiment was so strong that it would be a challenge for them to consider buying or cooking them for their children (Table 4).

c) Frozen vegetables: Frozen vegetables rarely came up in the discussion unless prompted by the moderator, and it seemed as though participants felt the need to justify why they used frozen vegetables. Frozen peas were the main exception, but even here, many participants emphasised that they had frozen vegetables as a reserve, for times when they were in a hurry, or to respond to individual children’s preferences. In several of the FGDs, there was discussion and disagreement about whether frozen vegetables were nutritionally better because it was ‘fresh frozen’ (M52) or ‘hadn’t got the goodness’ (M56). In general, the sentiment was that frozen was not as good as fresh for taste, texture, or nutrition but was widely acknowledged as being cheaper.

Attributes of parents

Parents’ vegetable shopping is shaped by their preferences and ideas about what are ‘normal’ amounts and how they fit into acceptable meal patterns, what they know how to cook and prepare (‘veg-literacy’), and their motivation and opportunity to serve vegetables.

a) Habits, preferences, and norms: Participants’ vegetable purchases were strongly influenced by habit; they spoke of going into the shop knowing what they wanted, not looking at promotions, and buying the same vegetables each week. This mainly comprised the ‘core veg’, plus other vegetables that ‘went’ with planned meals. Many participants referred to buying two or more non-core veg specifically for the traditional Sunday roast dinner and invested in this as an important family meal. These vegetables, such as parsnip, swede, or cauliflower, tended not to be used for other meals and were identified as often being left at the bottom of the fridge and thrown away. Some vegetables were considered the kind that vegetarians or ‘others’ would eat, but not them. Parents were aware that vegetables were important, and several gave their children raw ‘core veg’ as a snack or ‘starter’. When asked about the place of vegetables in other common meals, such as spaghetti bolognaise or pizza, some parents explained that ‘There is already veg in there’ (M23) (tomato and onion), and it was unnecessary to serve additional vegetables on the side. There were some exceptions to this; one parent spoke of serving coleslaw or other ready-made salads alongside so that ‘They’ve got a plate of food not just two slices of pizza. It makes it a dinner’, pointing out that, ‘If you go to Pizza Hut or somewhere you get a salad with it’ (MI).

b) Veg-literacy: In every FGD, there were one or two vegetables which few participants recognised (such as pak choi or celeriac) and some which several participants were uncertain how to use and only ate when other people cooked them (such as aubergine). In every FGD, there were also one or two participants who were unfamiliar with many of the vegetables (Table 5). The combination of exposure and familiarity with vegetables (‘veg knowledge’) combined with skills to select, prepare, and cook vegetables and the confidence to put this into practice (self-efficacy) and serve vegetables is what we have termed veg-literacy. The discussions suggested that initially, veg-literacy is shaped by parents’ exposure to different vegetables and cooking skills in childhood. Participants spoke of learning how to cook certain vegetables from their mothers or at school in home economics lessons. A few participants talked of knowing how to cook a wider range of vegetables than their parents, for example, through working in the catering trade or living in shared accommodation before having children. Veg-literacy seemed to be lower in younger parents and those who reported having minimal exposure to vegetable diversity in their own remembered childhood. One participant explained that when she became pregnant, she was young and still quite fussy about what she would eat, so she did not know what to do with a lot of vegetables; now, as a parent, she felt hampered by this. Others spoke of needing to see and taste an unknown vegetable before having the confidence to buy. Participants who seemed more veg-literate used a wider range of vegetables and cooking methods and had effective techniques for avoiding waste, using leftovers or vegetables that were starting to go off. They tended to be less likely to comment that vegetables were expensive.

c) Interest and opportunity to cook veg: This sub-theme brings together parents’ level of interest and practical opportunity for engagement in giving time, money, and effort to preparing and cooking vegetables, and getting the rest of the family to eat them. Although linked with veg-literacy, some of those who seemed most veg-literate and motivated were juggling many different professional and caring roles and complained that they had less opportunity to cook vegetables than they would have liked. Some parents clearly enjoyed cooking and were happy to spend time in the kitchen as a means of relaxation. For others, it was a chore or had become a chore that they struggled to fit in amongst other aspects of family life, particularly for single parents. Time was a recurrent limitation. Most parents recognised vegetables as an important part of their children’s diets and were therefore quite motivated to do things that would encourage their children to eat vegetables when they had time and enjoyed sharing their experiences. This ranged from using spiralisers, putting veg into smoothies, and involving children in food preparation.

Family food dynamics

This theme looks at the influence of interactions between parents and children around vegetable preferences and rejection. Some households accommodated children’s preferences by cooking different meals or different vegetables for individual family members, which meant the ‘picky’ child tended to have the same narrow range of ‘favoured’ or ‘accepted’ vegetables for most meals. In others, children’s preferences shaped and limited what was purchased and served for the entire household.

a) Picky or contrary eating: Most parents in the study had experience of children being picky about eating vegetables and expressed their frustration and exasperation (Table 6). Often, it was one child who was perceived as fussy while the others were good eaters. Some parents described behaviours that were consistent with general definitions of fussy eating: an unwillingness to eat familiar foods, try new foods, and strong food preferences.(Reference Taylor, Wernimont, Northstone and Emmett33) Others described behaviour that was constructed as contrary, for example, ‘eating cauliflower at Nan’s, but not at home’ (M55). Few seemed prepared to consider that the rejection of a vegetable at home might be because of the way it was cooked or served or the food that it was cooked with.

b) Shrinking range of vegetables: There seemed to be an acceptance and expectation that children would go through a phase when the range of vegetables they would eat shrinks and that this might last throughout the school years. Some spoke of children liking all sorts of vegetables until ‘they’re old enough to decide for themselves, then they wouldn’t go near it’ (M44). Parents clearly framed this as a phase, citing how children had ‘gone off’ rather than never eaten the vegetable. Parents with older children readily shared experiences that they had found useful in restoring the range of vegetables their children would eat, and at what age to expect an improvement. One parent spoke of encouraging her children to ‘“try it again because as you get older your taste buds change” and I found that actually works quite a lot’ (M16).

c) Exposure and modelling of veg eating to children: Parents of children who were ‘good veg eaters’ were regarded as fortunate, and other parents were curious about how this had been achieved. Some referred to the benefits of introducing different vegetables at an early age, when children tend to be more accepting. Parents reflected on their own behaviours; those who did not like vegetables themselves, or eat much, were not surprised that their children were unenthusiastic about the vegetables they served. Many spoke of the valuable influence of exposure to vegetables at school, noting that in the school/nursery environment, children were prepared to eat things which they would not eat at home, referring to the influence of peers and copying what others did. However, this was not always positive; a few spoke of their children going to school and copying the food rejection of others.

d) ‘Sneaking it in’: Opinions on disguising vegetables so that children will eat them were divided. Parents fully articulated the pros and cons of ‘sneaking’ vegetables into dishes, on the one hand, being an effective method of ensuring children ate their vegetables, but on the other, failing to educate and expand the conscious range of vegetables which children would eat and risking child–parent trust around meals. Examples of techniques for hiding vegetables in meals were more likely to be brought up by parents who were confident of their cooking methods and techniques. Awareness of the importance of diversity was low; a few acknowledged that their children ate ‘A limited range’ (M23). Overall, parents seemed happy (or relieved) if their child ate regularly from the ‘core veg’, then this was enough.

Influence of Retailers

a) Pack size and food waste: Most vegetables and salad sold in the supermarket are in prepacks, so quantities purchased are decided by the retailer, not the customer. Being required to buy more than was needed was a barrier to purchase, particularly for small families or households not eating many vegetables (Table 7). The risk of waste deterred some parents from buying heads of broccoli or fresh cauliflower or bags of vegetables/salad for themselves, which the children did not eat. There was general support for the idea of smaller packs, provided these were not disproportionately more expensive.

b) Response to price promotions: The response of most participants to questions around price promotions, discounts, or money-off vouchers for vegetables indicated how little flexibility most of the participants had to respond to such incentives. Generally, participants were pleased when special offers were on vegetables, which they usually bought (‘core veg’), but the discount did not make them buy more; instead, any saving was used to offset costs on other parts of the grocery bill. They were generally reluctant to buy anything that was not what they usually bought (‘off-list’). Several spoke of responding to special offers on fruit, but with vegetables, they were more likely to be ‘planning your meals for the week to a budget, so you have got in mind about what (veg) is needed’ (M44). The overriding message was that when money is tight, parents only buy what they know their kids will eat.

Discussion

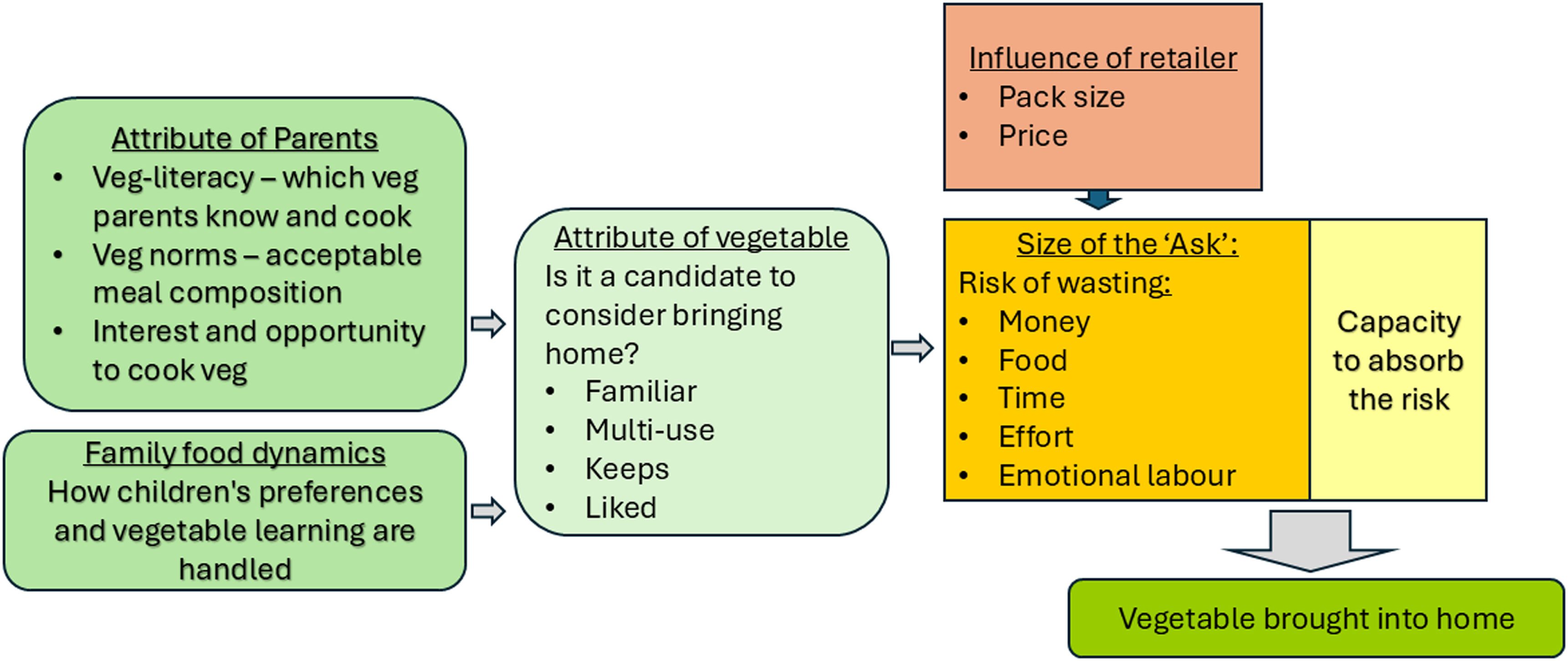

Our research sought to better understand how parents with limited funds for grocery shopping make decisions around buying vegetables from a supermarket and point to possible entry points for vegetable promotion interventions as part of wider public health initiatives. Our findings reveal the complex interplay of determinants that shape the range of vegetables brought into the home and, thereby, children’s early exposure and normalisation of patterns of vegetable consumption. A theoretical schema outlining how our analysis suggests these factors interact is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Theoretical schema illustrating how determinants of vegetable food choice influence vegetable shopping decisions of parents who ‘shop on a budget’.

The data suggest that parents who shop on a budget tend to shop for vegetables based on habit, routinely buying a set of ‘core veg’ or ‘safe veg’ they know will get fully used and are liked by their children. Five of the seven core veg identified in this study can be eaten without cooking. Unlike most foods on sale in supermarkets, vegetables are usually sold without cooking instructions, may have specific storage requirements, a short storage life, and their price and availability change with the seasons. Serving vegetables can require a higher level of practical food skills and knowledge than serving other foods, particularly for households that mainly use processed foods where meal preparation involves following instructions on packaging.(Reference Brasington, Bucher and Beckett34)

Studies on food literacy and cooking skills note a consistent positive association between cooking skills and vegetable intakes in all population groups.(Reference Hanson, Kattelmann and McCormack35–Reference Garcia, Reardon, McDonald and Vargas-Garcia39) Building on existing definitions of food literacy,(Reference Azevedo Perry, Thomas and Samra40,Reference Krause, Sommerhalder, Beer-Borst and Abel41) we used the term veg-literacy to refer to participants’ apparent familiarity, skills, knowledge, and self-efficacy to select, prepare, cook, serve, and store a range of vegetables, avoiding waste, and reflecting seasonality. Vegetables are one of the main sources of avoidable food waste in the home,(Reference De Laurentiss, Corrado and Sala42) so for households with small margins for wasting money on uneaten food, they can be a high-risk item.(Reference Daniel43) Low veg-literacy exposes parents to a greater risk of waste.

Other authors have also noted risk aversion to wasting food and money as shaping food decisions in low-income families.(Reference Daniel43) Our study suggests that risk aversion concerns additionally apply to the opportunity cost of wasting time and effort in preparing and serving vegetables and the risk of food rejection damaging parent–child trust around food and undermining parents’ self-efficacy around their cooking skills. Thus, decision-making is governed by a combination of being able to both afford (time, effort, money) and cope with the consequences of providing more or new vegetables. This seemed to be tempered by parents’ attitudes to the risk and disappointment of food being rejected and their opportunity in terms of time and practical resources to prepare and cook vegetables or meals generally. If parents are intrinsically motivated and interested to get their child to try or retry a new vegetable, they may derive satisfaction from putting their understanding into practice and thus feel less troubled if food is uneaten.

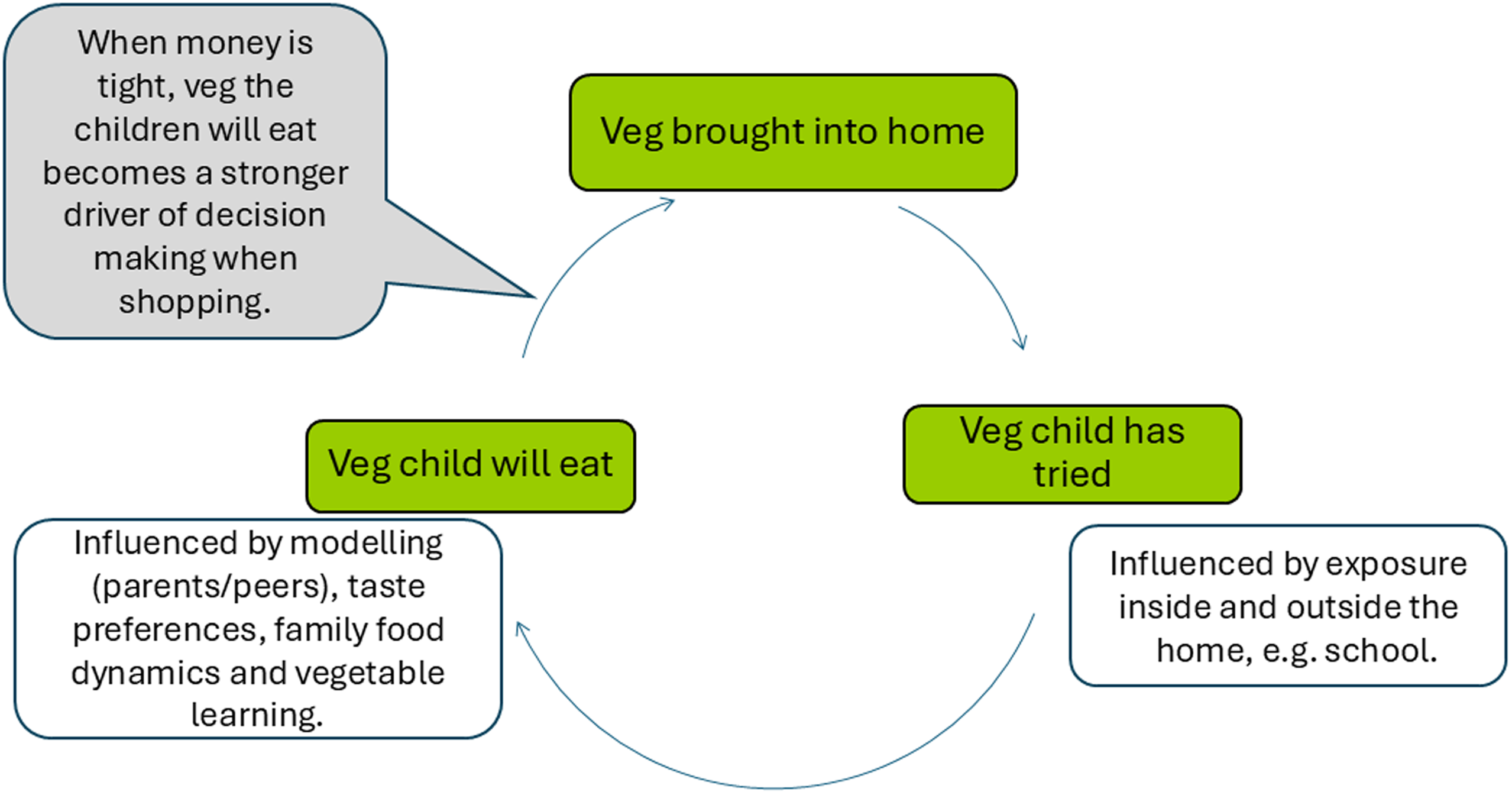

Parents are gatekeepers of the food and vegetables that are brought into the home.(Reference Wansink44) Children’s picky eating around vegetables is widely reported in the literature across all income groups.(Reference Taylor, Wernimont, Northstone and Emmett33,Reference Emmett, Hays and Taylor45) Children need repeated exposure to vegetables in early childhood to learn to accept their often sour or bitter flavours.(Reference Mennella, Pepino and Reed46) How parents respond to fussy eating around vegetables influences children’s exposure. Parents in our study, consistent with other studies in low-income families, were strongly motivated to avoid wasting food, tending to only buy vegetables that they knew their children would eat.(Reference Daniel43,Reference Harris, Staton, Morawska, Gallegos, Oakes and Thorpe47) Our findings suggest that if a child is picky about a vegetable, it can get written out of the household’s vegetable shopping habit and not bought again. This can set off a downward spiral whereby children are exposed to, and eat, a shrinking range of vegetables at home (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Schema illustrating how children’s exposure to vegetable diversity can shrink in low-budget households.

Other studies in low-income households have similarly noted the risk of children having limited exposure to vegetable diversity and missing out on early taste learning experiences.(Reference Daniel43,Reference Hardcastle and Caraher48,Reference Bowen, Elliott and Brenton49) The relatively limited vegetable diversity is a concern; epidemiological and experimental studies show a clear positive association between the variety of vegetables in the diet and quantities eaten in both adults(Reference Chawner, Blundell-Birtill and Hetherington50,Reference Meengs, Roe and Rolls51) and children(Reference Bucher, Siegrist and van der Horst52,Reference Marshall, van den Berg, Ranjit and Hoelscher53) including in low-income households. Public health nutrition recommendations have consistently recommended eating a variety of fruits and vegetables.(18) Over the past decade, there has been mounting evidence on the importance of the gut microbiome for health and the association between long-term intakes of a variety of fruits and vegetables and a healthful microbiota.(Reference Wallace, Bailey and Blumberg54–Reference Armet, Deehan and O’Sullivan56) It is important that vegetable promotion programmes look to increase and monitor both the diversity and amounts of vegetables in the diets of children and other low vegetable consumers.

Parents with higher levels of veg-literacy are likely to have more latitude to respond to vegetable promotions, as do larger families where other household members can eat any vegetables children might refuse, avoiding waste. By contrast, those with low veg-literacy, little interest, or capacity to invest in vegetables or those constrained by the narrow range of vegetables their child will eat tend to only be interested in price promotions on the vegetables that they already buy, as a way of releasing money for other things. Health promotion programmes using supply-side interventions such as vouchers or price discounts intended to increase consumption of healthier foods may be effective for households with the capacity to respond, but for low-budget households, they may simply act as financial assistance through expenditure displacements rather than improving dietary intake.

Practical implications

Most public health initiatives aiming to enable children and parents to buy and eat more vegetables, whether through media campaigns, price reductions, or choice architecture in supermarkets, are in effect asking parents to invest money, time, effort, and culinary confidence in preparing and cooking more vegetables. This ‘Ask’ has risks attached. For much of the general population, the risk may be negligible; households can readily absorb any waste or have levels of veg-literacy and confidence in their cooking skills to prevent it. But for parents who shop on a budget, our research suggests that limited veg-literacy, food norms, competing priorities, and complex lives mean that they had little motivation or opportunity to invest in what Bowen called ‘the invisible labour’ of incorporating more or different vegetables into family diets.(Reference Bowen, Elliott and Brenton49) Rather, shopping decisions are based on habit and familiar risk aversion strategies, which keep the household in balance.(Reference Daniel43)

As noted by other authors, reducing economic barriers may not diminish dietary inequalities unless other barriers are addressed.(Reference Mackenbach, Brage, Forouhi, Griffin, Wareham and Monsivais23) The range of vegetables children are exposed to in childhood begins to set their social norms around diet and their emerging veg-literacy and is arguably a key part of their education for life, equipping them to enjoy the taste and culinary opportunities of a range of vegetables. Participants in our study valued school meals for introducing different vegetables and for the peer effect, which encouraged children to taste and experiment. Given the constraints facing low-income households, school meals could be a critical social leveller for exposure to vegetable variety and taste formation; mass catering is able to absorb, mitigate, and redeploy the inevitable food waste of children’s learning exposures to new vegetables.

The importance of veg-literacy and exposure to enhance vegetable familiarity and thus diversity and norms emerge as areas for potential programme development. This might require coordinated multisectoral interventions, for example, which align promotions in the supermarket for the general population with targeted measures that enable those with limited food budgets to access and taste the promoted vegetables cost free, perhaps via local meals services, food banks, or targeted give-aways via supermarket loyalty schemes. Project design needs to recognise that certain vegetables are intensely disliked and including them in promotions, mixed packs, or main ingredients for recipes or activities could limit uptake. Making vegetable promotions accessible to low-budget households has two components: strengthening parents’ capacity to respond (e.g. by increasing veg-literacy) and reducing the ‘ask’ by selecting vegetables that are easy to prepare. The potential of frozen vegetables and small pack sizes could be further explored.

Low vegetable intakes are a significant public health nutrition challenge globally.(3) A recent review of food and health literacies noted the need for tighter alignment between health outcomes and the competencies required to achieve them.(Reference Truman, Bischoff and Elliott57) We propose that the concept of veg-literacy could be a valuable subset within food literacy for designing, setting objectives, and monitoring vegetable promotion interventions.

Since the research was carried out in 2018, the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent global increases in the cost of living are likely to have intensified financial pressures on households with limited food budgets.(Reference Hoenink, Garrott, Jones, Conklin, Monsivais and Adams58) The broad themes identified in our research remain pertinent; however, higher food prices will increase pressures for household food choices to be driven by children’s preferences as a risk aversion strategy. It will be important that school meals and community food offers are supported to counter any reduction in the diversity of vegetables used in the home due to households cutting costs. Our increasing awareness of the importance of diversity of fruit and vegetable consumption for gut health and the need to double global consumption of fruit and vegetables for planetary health to offset reductions in meat and dairy indicate that action to reduce inequalities in vegetable consumption remains relevant.(Reference Willett, Rockstrom and Loken14,Reference Armet, Deehan and O’Sullivan56)

Strengths and limitations

The study’s strengths include its focus on vegetables and high representation of households from an area in the lowest quintile of IMD. The study provides depth, not breadth, and was conducted with a mostly white British ethnic group; understandings in other populations and places may differ. Participants self-selected to join the FGDs so might be more interested in food than the general population. We used photographs of vegetables as displayed in the freezer cabinet during the FGD rather than actual bags of frozen vegetables, and it is possible that this may have influenced participants’ readiness and comfort in talking about frozen vegetables.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that without targeted measures directed towards population groups facing the biggest challenges, supply-side vegetable promotion programmes to the general population risk widening dietary inequalities. This applies to both short-term and long-term inequalities through the influence of vegetable exposure on shaping children’s taste acquisition and an intergenerational cycle of households where eating certain vegetables is not a household norm. We suggest that reducing the ‘Ask’ of eating more vegetables for low-budget households would entail promotions on vegetables, which can be eaten raw, have a good shelf life, and can be purchased in small quantities. Price promotions on ‘core veg’, which are already routinely bought, are more likely to result in expenditure displacement rather than increasing amounts or diversity of vegetables purchased.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Katie Cummings, Victoria Lawrence, Chloe Clarke of Brighton & Hove City Council, and Amali Bunter and Mark Newbold from Lidl for facilitating access to the recruitment locations and contributing to the progress meeting. From the University of Brighton, we thank Sophie Clarke, MSc placement student, for helping with recruitment, Sarah Cork and Harvey Ells for comments on study design, Alexandra Sawyer for support with NVivo, and Sarah Kehoe for editing advice. Most of all, we would like to thank all the parents and grandparents who took time to talk to us about ‘the vegetables in their lives’ and members of local community groups, health centre, and local Lidl staff who supported us with recruitment.

Authorship

CW designed the research, recruited, and facilitated the focus groups, analysed the data, and wrote the article. MG recruited and co-facilitated the focus groups. MG and NS contributed to the analysis and gave comments on the design and manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors only.

Financial support

Direct, non-staff running costs for venue hire and refreshments, vegetable props, and vouchers for participants were funded by a project grant from Lidl supermarkets as part of their work in developing campaign pledges for the Food Foundation’s Peas Please vegetable promotion project.

Competing interests

The project grant was awarded to the first author by LIDL supermarkets. LIDL had no input into the design or conduct of the research, and no involvement or influence regarding the views expressed and the results presented in this publication.