Non-technical Summary

This is the first report of Jurassic crabs and their relatives, the squat lobsters, from the territory of Russia. These findings come from the Upper Jurassic (Oxfordian) reef limestones of the North Caucasus. The squat lobster Gastrosacus wetzleri von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851, collected from the locality near the Urup River, is the first find of this species outside of western Europe. The crab Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazăr, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007 was discovered from another locality near the Kamennomostsky village. This species was first described from the Oxfordian of Romania. These fossil remains from the Oxfordian of the North Caucasus indicate an interconnected marine community of crabs and squat lobsters in the Late Jurassic in the Tethys basins.

Introduction

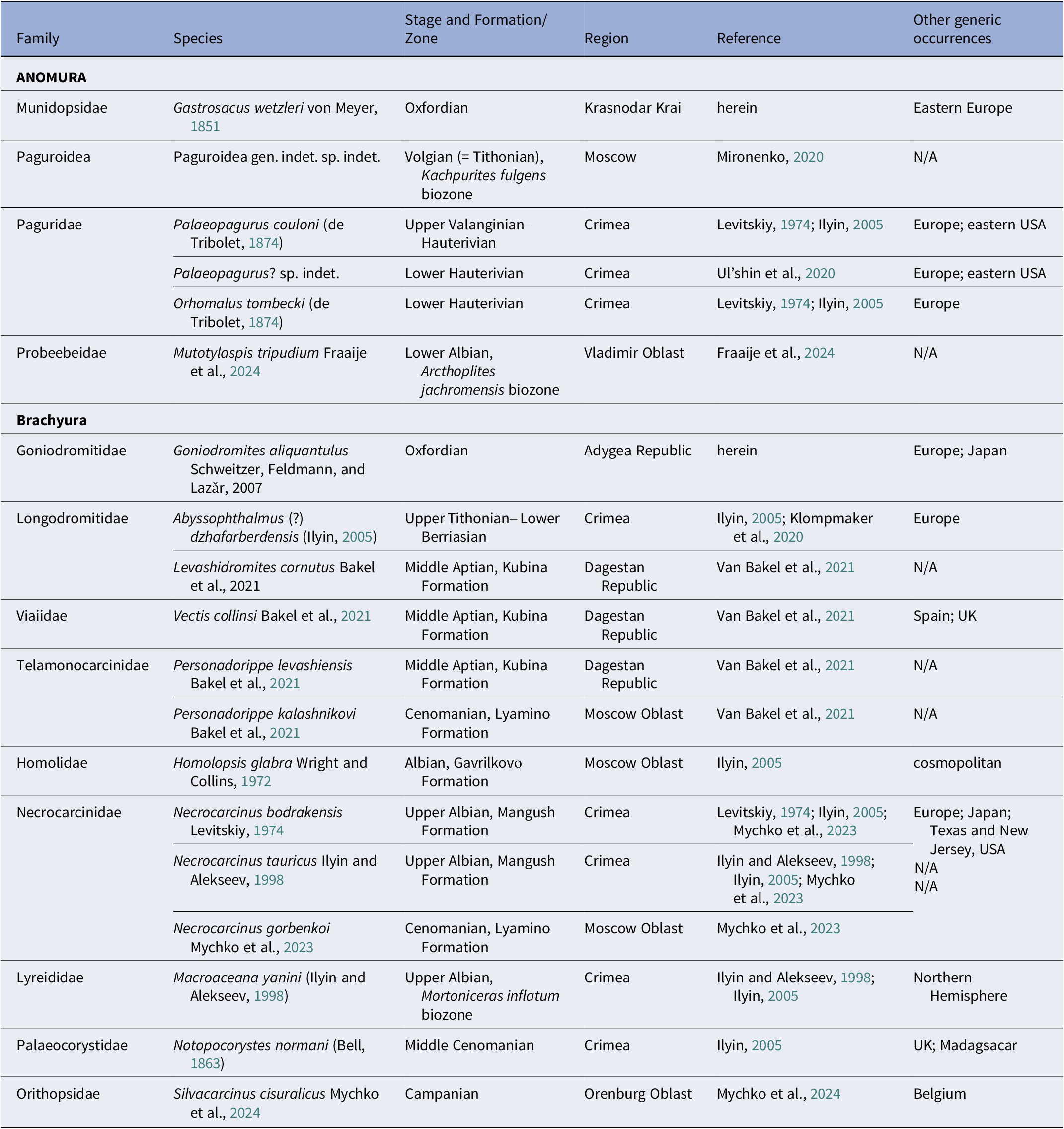

Few localities of Mesozoic fossils of Anomura and Brachyura from the vast territory of Russia have been described (Table 1). Species of Brachyura known from the Cretaceous of the Moscow Oblast (region of Central Russia including the Albian [Gavrilkovо Formation]), Homolopsis glabra Wright and Collins, Reference Wright and Collins1972 and Personadorippe kalashnikovi Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021, and Necrocarcinus gorbenkoi Mychko et al., Reference Mychko, Schweitzer, Feldmann and Shmakov2023 described from Cenomanian rocks (Lyamino Formation) (Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021; Mychko et al., Reference Mychko, Schweitzer, Feldmann and Shmakov2023). The only record of Anomura from this region comes from Jurassic deposits (Volgian [= Tithonian]), by the remains of a hermit crab (Paguroidea gen. indet. sp. indet.) of poor preservation in an ammonite shell (Mironenko, Reference Mironenko2020). A unique hermit crab, Mutotylaspis tripudium Fraaije et al., Reference Fraaije, Mychko, Barsukov and Jagt2024, was recently described from a neighboring region, the Vladimir Oblast. It was discovered from an almost complete carapace and appendages found in a concretion in Lower Cretaceous (Albian) rocks (Fraaije et al., Reference Fraaije, Mychko, Barsukov and Jagt2024). The assemblage of Lower Cretaceous crabs from Dagestan is quite interesting and includes Levashidromites cornutus Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021, Personadorippe levashiensis Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021, and Vectis collinsi Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021, fossil remains of which were discovered in Aptian deposits (Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021). The Cretaceous of Crimea contains a relatively high number of crab remains, which were found in various geological formations. The oldest species is Abyssophthalmus (?) dzhafarberdensis (Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005), described from deposits of the Upper Jurassic (Upper Tithonian)–Lower Cretaceous (Lower Berriasian) boundary (Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005; Klompmaker et al., Reference Klompmaker, Starzyk, Fraaije and Schweigert2020). Albian crabs are represented by Necrocarcinus bodrakensis Levitskiy, Reference Levitskiy1974, Necrocarcinus tauricus Ilyin and Alekseev, Reference Ilyin and Alekseev1998, and Macroacaena yanini (Ilyin and Alekseev, Reference Ilyin and Alekseev1998) (Levitskiy, Reference Levitskiy1974; Ilyin and Alekseev, Reference Ilyin and Alekseev1998; Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2021). Cenomanian crabs are represented only by Notopocorystes normani (Bell, Reference Bell1863) (Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005). Anomurans of Crimea are found in the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian–Hauterivian) and are represented by the remains of Orhomalus tombecki (de Tribolet, Reference de Tribolet1875), Palaeopagurus couloni (de Tribolet, Reference de Tribolet1874), and Palaeopagurus? sp. indet. (Levitskiy, Reference Levitskiy1974; Ilyin, Reference Ilyin2005; Ul’shin et al., Reference Ul’shin, Tishchenko and Pologov2020). Recently, the authors of this paper described a new brachyuran species, Silvacarcinus cisuralicus Mychko et al., Reference Mychko, Schweitzer and Feldmann2024, from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) in the Orenburg Oblast (Mychko et al., Reference Mychko, Schweitzer and Feldmann2024).

Table 1. Mesozoic brachyuran and anomuran occurrences from Russia. For other generic occurrence references, consult Schweitzer et al. (Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023)

This is the first scientific publication on Jurassic brachyurans and anomurans from Russia. Geographically, the closest region to Russia with Jurassic (Callovian) crabs was Lithuania, from which the species Tanidromites lithuanicus Schweigert and Koppka, Reference Schweigert and Koppka2011 was described.

Jurassic brachyurans and anomurans are abundant and diverse from European localities and have received considerable attention in recent years. Jurassic brachyuran and anomuran localities in southern Germany include localities of the Pliensbachian (Förster, Reference Förster1986; Schweigert et al., Reference Schweigert, Fraaije, Nützel and Havlik2013), Middle Callovian (Pleistocene glacial boulder; Schweigert and Koppka, Reference Schweigert and Koppka2011), Kimmeridgian (Dietl and Schweigert, Reference Dietl and Schweigert2001; Garassino et al., Reference Garassino, De Angeli and Schweigert2005; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Fraaije, Jagt and Artal2008; Feldmann and Schweitzer, Reference Feldmann and Schweitzer2009; Schweigert and Koppka, Reference Schweigert and Koppka2011; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Gründel, Jäger, Löser, Schlampp, Schneider and Werner2017; Schweigert, Reference Schweigert2021), and Tithonian (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen1964; Garassino et al., Reference Garassino, De Angeli and Schweigert2005). Jurassic crabs from France are represented by several localities from the Middle and Upper Jurassic. A detailed list of these taxa and their localities in this region has been provided in several recent following works (Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008; Van Bakel and Guinot, Reference Van Bakel and Guinot2023). Anomurans and brachyurans have been described from the Bajocian of northern Switzerland (Förster, Reference Förster1985). Oxfordian and Kimmeridgian brachyurans from Switzerland were also reported (Étallon, Reference Étallon1859, Reference Étallon1861). In northeastern Italy, the remains of crabs have been discovered and are confined to the Oxfordian–Kimmeridgian limestones of the Fonzaso Formation (De Angeli and Garassino, Reference De Angeli and Garassino2006). Dromiacean crabs are reported from Lower Callovian deposits in Austria (Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2016; Stolley, Reference Stolley1914). A high diversity of Anomura and Brachyura has been found in the Tithonian (Ernstbrunn Limestone) in Austria, documented in several works (Bachmayer, Reference Bachmayer1947; Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2009; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013). Pliensbachian, Aalenian, and Bathonian brachyurans and anomurans have been reported from England (Woodward, Reference Woodward1868, Reference Woodward1907; Withers, Reference Withers1932; Krobicki and Zatoń; Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008).

From eastern Europe, there are a number of localities of Jurassic anomurans and brachyurans in southern Poland. These localities are represented by Bajocian and Bathonian (Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008), Callovian (Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008), Oxfordian (Collins and Wierzbowski, Reference Collins and Wierzbowski1985; Trammer, Reference Trammer1989; Garassino and Krobicki, Reference Garassino and Krobicki2002; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Fraaije, Jagt and Artal2008; Starzyk et al., Reference Starzyk, Krzemińska and Krzemiński2012), and Tithonian rocks (Patrulius, Reference Patrulius1966; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023). From Slovakia, brachyurans and anomurans were described from Middle Oxfordian limestones (Hyžný et al., Reference Hyžný, Schlögl and Krobicki2011); anomurans were also described from the Kimmeridgian–Tithonian of Slovenia (Gašparič et al., Reference Gašparič, Robins and Gale2020). Several Tithonian anomuran and brachyuran localities are known from the Czech Republic, notably from the Štramberk Limestones (Moericke, Reference Moericke1889; Blaschke, Reference Blaschke1911; Kummel, Reference Kummel1956; Bachmayer, Reference Bachmayer1959; Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2009; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023). A large number of localities and taxa of Jurassic decapods (Anomura and Brachyura) come from Romania, including Oxfordian (Feldmann et al., Reference Feldmann, Lazăr and Schweitzer2006; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007; Franţescu, Reference Franţescu2011), Oxfordian–Kimmeridgian (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Lazăr, Feldmann, Stoica and Franţescu2017), and Tithonian deposits (Patrulius, Reference Patrulius1959; Muţiu and Bădăluţă, Reference Muţiu and Bădăluţă1971; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann, Schweitzer and Bonde2016).

The easternmost findings of Jurassic crabs are confined to China and Japan. From China, crabs are known from Tibet (Zhamunaqu Formation; Smith and Xu, Reference Smith and Xu1988). Dromiacean crabs have been found in the Upper Kimmeridgian–Lower Tithonian sandstones of the Nakanosawa Formation in Japan (Kato et al., Reference Kato, Takahashi and Taira2010) and several Upper Jurassic species of prosopid crabs are known from Torinosu Group (Karasawa and Kato, Reference Karasawa and Kato2007).

The southernmost Jurassic brachyurans were discovered in the Bajocian Lugoba Formation in Tanzania and are represented by a number of taxa, including Prosopon sp. indet., Gabriella lugobaensis (Förster, Reference Förster1985), and others (Förster, Reference Förster1985; Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008).

This brief overview of Jurassic decapod anomuran and brachyuran occurrences demonstrates that although they are known from most areas of Europe, occurrences in Russia have until now been absent. This report fills this gap in knowledge of these organisms and establishes that the Russian fauna has close affinities with those of southeastern Europe.

Locality and geological setting

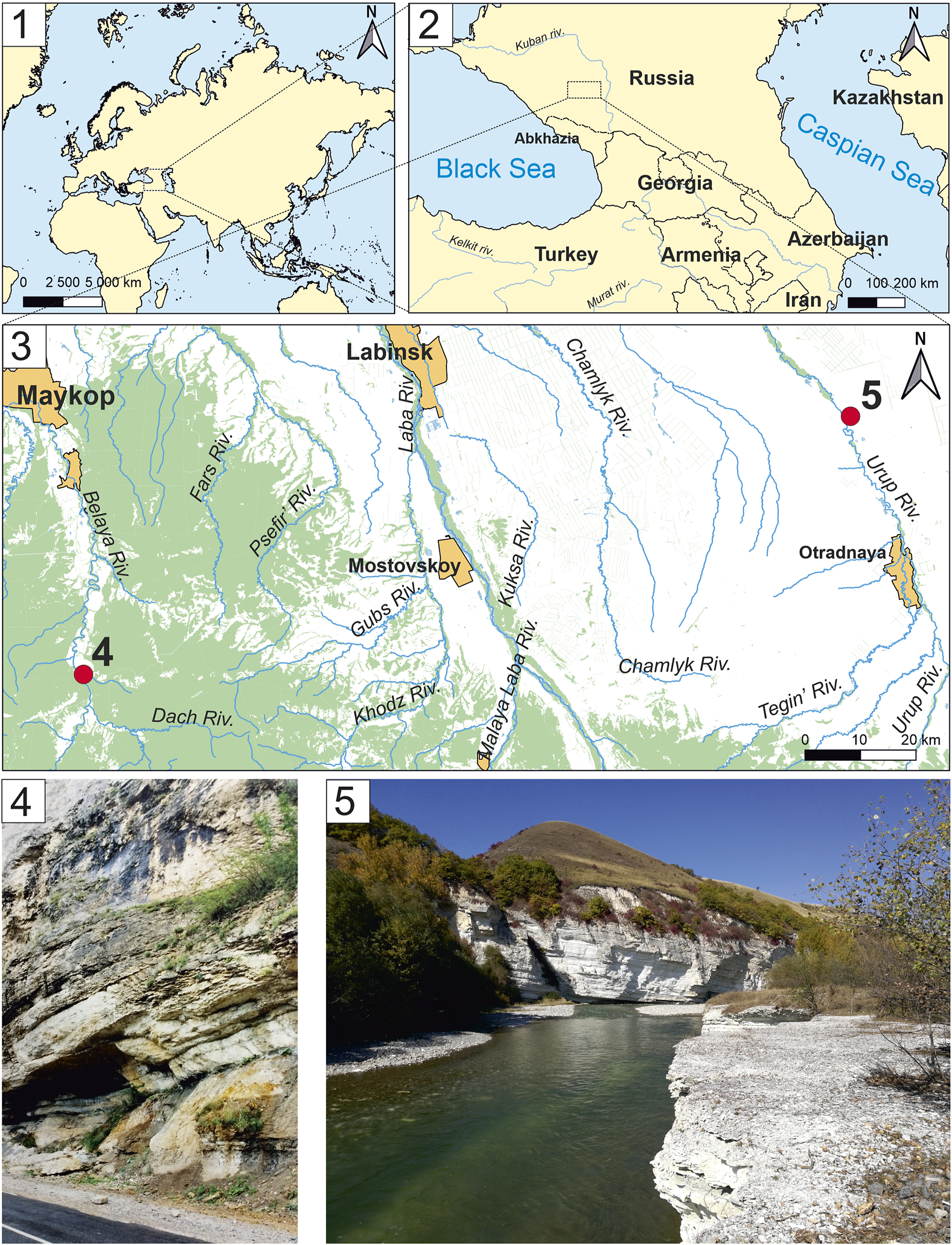

The decapod fossils described in this paper were found in two localities located in the Adygea Republic and Krasnodar Krai (Fig. 1). These localities are both confined to outcrops of Oxfordian limestone, which is common in the region.

Figure 1. Localities of described decapods of North Caucasus: (1) schematic map of the Eastern Hemisphere; (2) schematic map of the Caucasus and Transcaucasia; (3) terrain map of the North Caucasus with localities (4) and (5) (Republic of Adygea and Krasnodar Krai, Russia); (4) Dachovskaya–Kamennomostsky, Oxfordian limestone near the Kamennomostsky village (photo by D. Kiselev); (5) Urup River, Oxfordian limestone on Bolshoi Zelenchuk River (photo by M. Sukhot’ko).

Dachovskaya–Kamennomostsky (Fig. 1.4)

In the Belaya River Valley, between the Guzeripl’ village and the Kamennomostsky village, rich fossil remains of Callovian and Oxfordian deposits have been found. There, south of the Kamennomostsky village, near the recreation center ‘Chalet Dakh’ (Fig. 1.4; 44°16’08.2"N, 40°13’22.4"E, WGS84), in crushed limestone, amateur paleontologist Ksenia Belikova from 24–26 July 2023 discovered fossils of various invertebrates (Fig. 2.5, 2.6) including crab carapaces. The crushed stone was extracted from limestones exposed in the Belaya River Valley and mined in a quarry south of the Kamennomostsky village.

Coral limestones were first discovered and described there by Nikshich in 1915. In that work, he indicated the presence of three ‘zones’ with fauna: (1) light-colored coralline limestone with various bivalves, brachiopods, and corals; (2) layered yellow limestone almost devoid of fossils; (3) limestone with flint nodules and remains of sponges, brachiopods, crinoids, and sea urchins, as well as ammonites (Nikshich, Reference Nikshich1915, p. 517).

The most recent and complete description of these deposits near the Kamennomostsky village was made by Lominadze in 1982. He identified six layers (Lominadze, Reference Lominadze1982, fig. 64), of which there are four Callovian terrigenous layers and two early Oxfordian limestone layers. Lominadze (Reference Lominadze1982) noted a large number of ammonite shells in the deposits under discussion.

Later authors (Kiselev et al., Reference Kiselev, Rogov, Glinskikh, Guzhikov, Pimenov, Mikhailov, Dzyuba, Matveev and Tesakova2013) noted that ammonites from these deposits have never been depicted. Kiselev (Reference Kiselev2022) provided a brief description of the Callovian-Oxfordian boundary section studied in several outcrops along the road running west of the Belaya River from the Kamennomostsky village and the Dakhovskaya village to the Lago-Naki Plateau. In that work, it was noted that Layer 3, represented by light-colored limestone with abundant remains of sponges, solitary corals, serpulids, terebratulides, and sea urchins, contains remains of the ammonite Cardioceras (Scarburgiceras) scarburgense (Young and Bird, Reference Young and Bird1828). According to this ammonite species, Layer 3 can be attributed to the lowest biostraton of the Oxfordian stage—the scarburgense biohorizon. Above Layer 3 there is a multimeter layer of rhythmically alternating sponge-algal limestones and silts, in which no ammonites were found (Kiselev, Reference Kiselev2022, p. 336).

Urup River (Fig. 1.5)

In the area of the Gusarovskoye village (44°34’56.194"N, 41°24’57.485"E, WGS84) on the Urup River, in crushed limestone (as in the first locality), amateur paleontologist Maxim Sukhot’ko discovered fossil remains of Jurassic invertebrates in 2020, including the anomuran carapace described in this paper, as well as, later, the brachyuran Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007, the same species as from the previous locality (Dachovskaya–Kamennomostsky) on the Belaya River. The place of extraction of this crushed stone is located near the Bolshoi Zelenchuk River.

Upper Callovian–Oxfordian bioherms are widely developed in this region. They are separated by beds of layered limestone, often alternating with marls, and due to their massive composition, they are clearly distinguished in relief (Loginova, Reference Loginova1964). According to Rostovtsev et al. (Reference Rostovtsev, Agajev, Azarjan, Babajev and Beznosov1992), these deposits are included in the Herpegem Formation. At the base of the Herpegem Formation lies a basal horizon of limestone conglomerates and brecciated limestones, which to the east of the watershed of the Bolshaya Laba and Urup rivers is mixed with sandstones and gravelites. Above it is a layer of limestone, underlain by interlayers of marls, and in the middle part there are massive dolomitized limestones, which in places contain large reef bioherms mentioned by Loginova (Reference Loginova1964). These reef bodies often contain corals, brachiopods, ammonites, and other fossil fauna (Figs. 2.1–4).

Materials and methods

Abbreviations

CaW = width of cardiac region; CL = maximum carapace length; CW = maximum carapace width; GH = length of gastric region; GW = width of the gastric region; L = length of carapace excluding rostrum; LR = total length of carapace including rostrum; MW = maximum mesogastric width; OW = orbital width; PW = posterior width; R = length of rostrum; RW = rostral width; TW = total width of anterior margin; UW = width of urogastric region; W = maximum width.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

MWO = Museum of the World Ocean, Kaliningrad, Russia; LPBIIIart = Laboratory of Paleontology, Department of Geology and Paleontology, University of Bucharest, Romania; SNSB-BSPG = Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Historische Geologie, München (Munich), Germany.

Systematic paleontology

We follow the classification published in Treatise Online for Dromiacea and Galatheoidea (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023, respectively).

Order Decapoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Infraorder Anomura MacLeay, Reference MacLeay1838

Superfamily Galatheoidea Samouelle, Reference Samouelle1819

Family Munidopsidae Ortmann, Reference Ortmann and Bronn1898

Genus Gastrosacus von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851

Type species

Gastrosacus wetzleri von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851.

Other species

Gastrosacus aequabus Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013; Gastrosacus carteri Van Straelen, Reference Van Straelen1925; Gastrosacus eminens (Blaschke, Reference Blaschke1911), originally as Galathea Fabricius, Reference Fabricius1793; Gastrosacus ernstbrunnensis Bachmayer, Reference Bachmayer1947; Gastrosacus? latirostris (Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1929), originally as Gastrosacus; Gastrosacus levocardiacus Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013; Gastrosacus limacurvus Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013; Gastrosacus meyeri (Moericke, Reference Moericke1889), originally as Galathea; Gastrosacus pisinnus Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013; Gastrosacus raboeufi Fraaije et al., Reference Fraaije, Van Bakel, Jagt, Charbonnier and Pezy2019; Gastrosacus robineaui (de Tribolet, Reference de Tribolet1874); Gastrosacus straeleni (Ruiz de Gaona, Reference Ruiz de Gaona1943); Gastrosacus torosus Robins et al., Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013; Gastrosacus tuberosiformis (Lörenthey in Lörenthey and Beurlen, Reference Lörenthey and Beurlen1929), originally as Galatheites Balss, Reference Balss1913; Gastrosacus tuberosus (Remeš, Reference Remeš1895), originally as Galathea; and Gastrosacus ubaghsi (Pelseneer, Reference Pelseneer1886), originally as Galathea.

Diagnosis

As by Robins et al. (Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013, p. 181).

Gastrosacus wetzleri von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851

Reference von Meyer1851 Gastrosacus wetzleri von Meyer, p. 677.

Reference von Meyer1854 Gastrosacus wetzleri; von Meyer, p. 51, pl. 10, figs. 3, 4.

Reference Quenstedt1857 Prosopon aculeatum von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1857; Quenstedt, p. 779, pl. 95, figs. 46–47.

Reference von Meyer1860 Gastrosacus wetzleri; von Meyer, p. 219, 220, pl. 23, fig. 34.

Reference Quenstedt1868 Prosopon aculeatum; Quenstedt, p. 315, pl. 26, fig. 14.

Reference Carter1898 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Carter, p. 18, pl. i, fig. 3a, b.

Reference Van Straelen1925 Gastrosacus Carteri ‘von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851’; Van Straelen, p. 299, 300, fig. 135.

Reference Van Straelen1925 Gastrosacus Wetzleri; Van Straelen, p. 300.

Reference Klompmaker, Artal, Fraaije and Jagt2011 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Klompmaker et al., p. 228.

Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Robins et al., p. 167, 168, 179, 181, 182, 184, 188, 226, 242, 243, pls. 6.11, 7.1.

Reference Robins, Feldmann and Schweitzer2013 Gastrosacus carteri Van Straelen, Reference Van Straelen1925; Robins et al., p. 184, fig. 7.9.

Reference Fraaije2014 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Fraaije, p. 123, fig. 3A–C.

Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Robins et al., p. 87–89, figs. 2, 3.

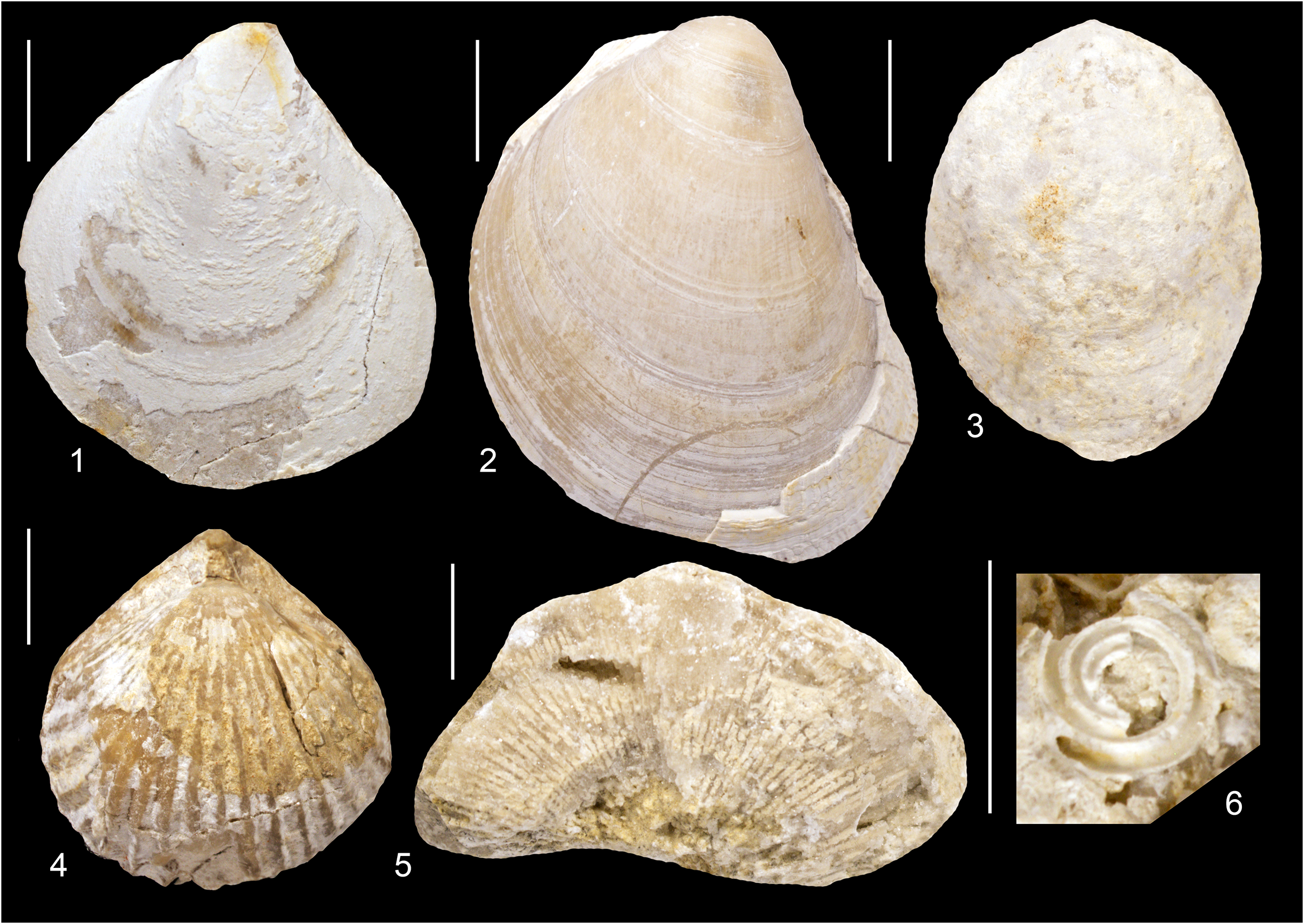

Figure 2. Fossil remains from deposits with described decapods of North Caucasus: (1–4) collected from locality near Urup River: (1, 2) bivalves, MWO 1 no. 12877, 12878; (3) terebratulid brachiopod, MWO 1 no. 12874; (4), rhynchonellid brachiopod, MWO 1 no. 12880; (5, 6) collected from locality near the Kamennomostsky village: (5) fragment of hexacoral, MWO 1 no. 12873; (6) serpulid annelid worm, MWO 1 no. 12879. Scale bars = 1 cm.

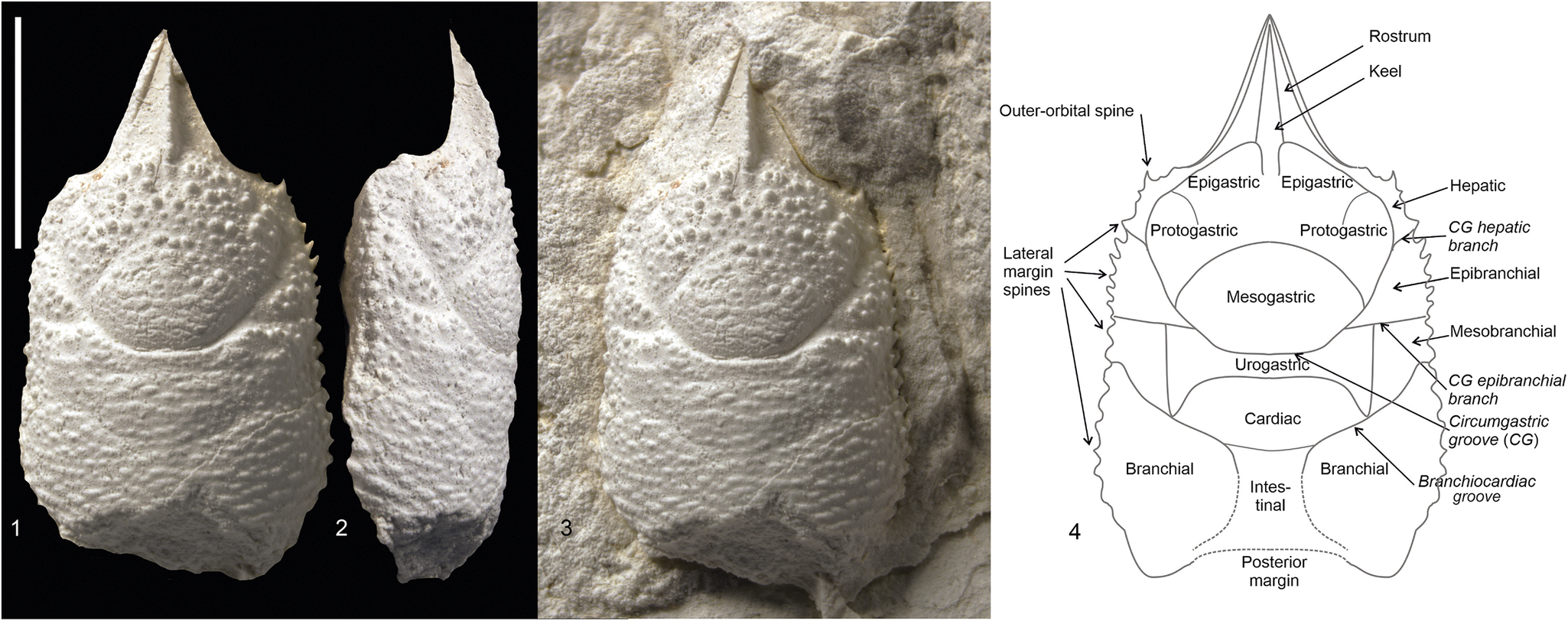

Figure 3. Gastrosacus wetzleri von Meyer, Reference von Meyer1851, almost complete carapace, MWO 1 no. 12876, from crushed limestone near the Urup River, district of the Gusarovskoye village, Krasnodar Krai, Russia; Oxfordian, Upper Jurassic: (1) dorsal view; (2) left lateral view; (3) the specimen in the rock; (4) schematic of carapace morphology. Scale bars = 5 mm (1, 2).

Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa, Klompmaker, Robins and Seldon2023 Gastrosacus wetzleri; Schweitzer et al., p. 14, fig. 8.5

Neotype

An almost complete carapace, SNSB-BSPG IX 683; uppermost Kimmeridgian, Upper Jurassic; Oerlinger Tal near Ulm, Germany; designated by Robins et al. (Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015, p. 89).

Diagnosis

As by Robins et al. (Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015, p. 87).

Occurrence

Upper Kimmeridgian (see Robins et al., Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015) of Germany–Oxfordian of England (see Carter, Reference Carter1898; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015) and Russia (crushed limestone near the Urup River, near the Gusarovskoye village, Krasnodar Krai; the limestone was extracted near the Bol’shoy Zelenchuk River in the Krasnodar Krai).

Description

Carapace longitudinally subrectangular, tapering very slightly from posterior to anterior, weakly convex longitudinally and transversely, CL/TW 1.7, CL/MW 1.29. Rostrum relatively wide, long in proportion to carapace, slightly deflected downward; keel of rostrum high, visible; lateral margins of rostrum angling slightly toward each other, converging to a point; lateral edges limited by groove and swelling. Orbital margin rimmed. Carapace bearing triangular outer orbital spine, small, curved toward rostrum. Several small spines on orbital margin. Lateral margin straight with at least 16 very small spines; these sharp, curved toward anterior carapace. Circumgastric groove pronounced, deep, separating urogastric from mesogastric region. Groove horizontal in central part, but curving forward at epibranchial furrow. There, circumgastric groove dividing into hepatic branch posteriorly and epibranchial branch anteriorly. Hepatic branch continuation of circumgastric groove, more obvious and deeper than epibranchial branch. Tubercles round and large in anterior mesogastric region, flattened in posterior mesogastric region, turning into wrinkled texture. Epigastric and protogastric regions small, steep, separated by barely noticeable groove not reaching middle regions. Hepatic region very small, flattened. Epibranchial region behind it much larger, wedge-shaped.

Surface of carapace on epibranchial, hepatic, epigastric, and protogastric regions covered with large tubercles. Largest tubercles located toward lateral margin and closer to rostrum. Urogastric region very narrow, widening slightly laterally, separated from cardiac region by faint groove; surface covered with small transversely oblong tubercles, more reminiscent of wrinkles. Mesobranchial regions subrectangular, small. Cardiac region flattened, subcrescent shaped, larger than urogastric. Branchial regions very large, covered with oblong tubercles. Posterior margin possibly rimmed with concave inflection. Ventral surface and appendages not preserved.

Material examined

An almost complete carapace, MWO 1 no. 12876.

Measurements (in mm)

LR 11.5; L 8.8; R 2.7; GH 4.1; RW 2.7; OW 4.8; TW 5.3; GW 5.6; UW 3.9; CaW 4; W 6.8; L/W 1.29; L/TW 1.7.

Remarks

This specimen is very similar to various specimens of Gastrosacus wetzleri from the Upper Jurassic of Germany, including the neotype, in its carapace ornamentation and the shape of the rostrum.

Infraorder Brachyura Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758

Section Dromiacea De Haan, Reference De Haan and von Siebold1833

Superfamily Homolodromioidea Alcock, Reference Alcock1900

Family Goniodromitidae Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1932

Genus Goniodromites Reuss, Reference Reuss1858

Type species

Goniodromites bidentatus Reuss, Reference Reuss1858, by subsequent designation (Glaessner, Reference Glaessner and Pompeckj1929).

Other species

Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007; Goniodromites complanatus Reuss, Reference Reuss1858; Goniodromites cenomanensis (Wright and Collins, Reference Wright and Collins1972); Goniodromites dacica (von Mücke, Reference von Mücke1915); Goniodromites dentatus Lörenthey in Lörenthey and Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1929; Goniodromites hirotai Karasawa and Kato, Reference Karasawa and Kato2007; Goniodromites kubai Starzyk et al., Reference Starzyk, Krzemińska and Krzemiński2012; Goniodromites laevis (Van Straelen, Reference Van Straelen1940); Goniodromites narinosus Franţescu, Reference Franţescu2011; Goniodromites polyodon Reuss, Reference Reuss1858; Goniodromites sakawense Karasawa and Kato, Reference Karasawa and Kato2007; Goniodromites transsylvanicus (Lörenthey in Lörenthey and Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1929).

Diagnosis

As by Schweitzer et al. (Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Karasawa and Seldon2012, p. 4).

Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007

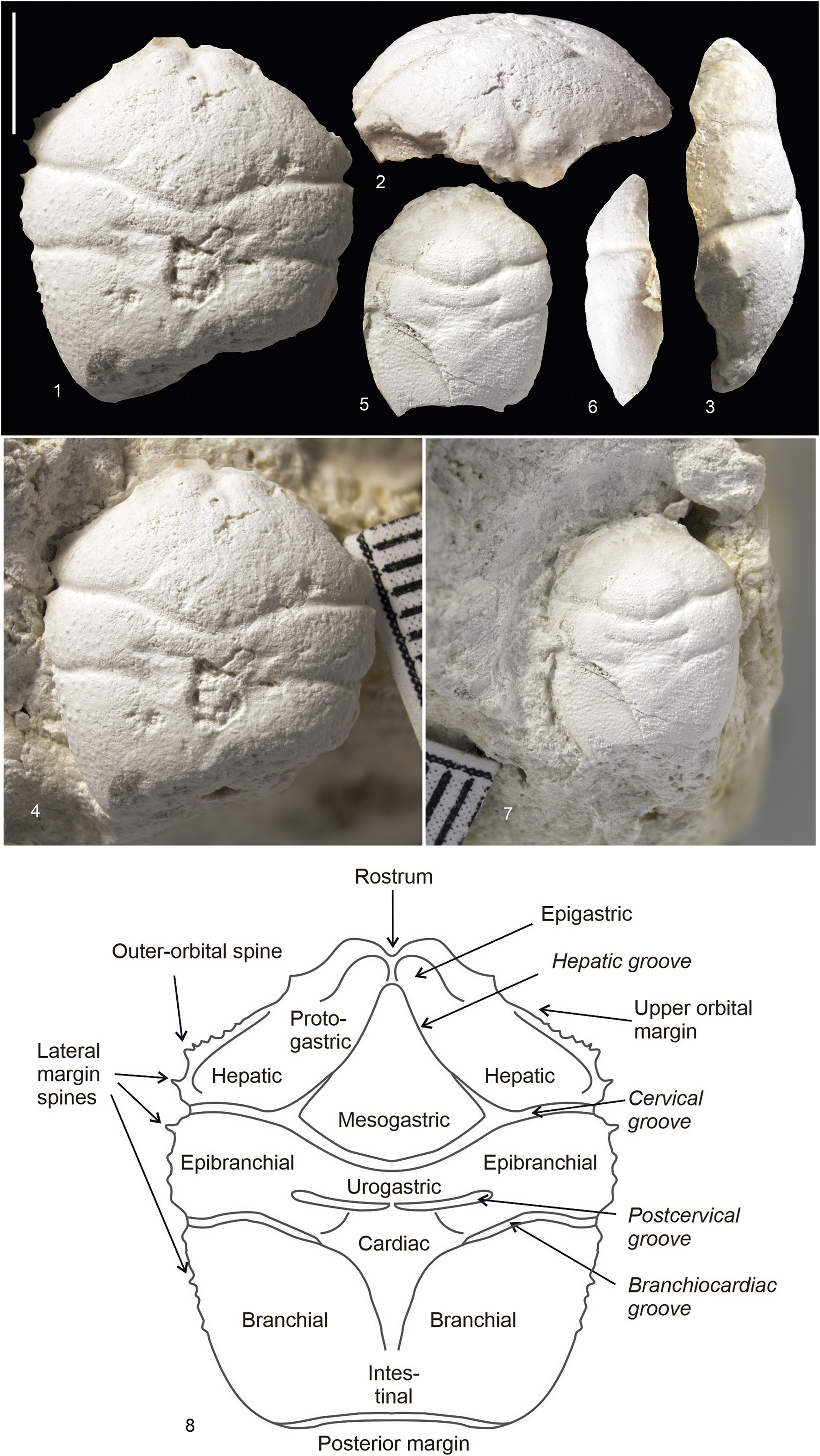

Figure 4. Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007, collected from crushed limestone near the Kamennomostsky village, Maikop district, Republic of Adygea, Russia; Oxfordian, Upper Jurassic: (1–4) MWO 1 no. 12875-1: (1) dorsal view; (2) anterior view; (3) left lateral view; (4) the specimen in the rock; (5–7) MWO 1 no. 12875-2: (5) dorsal view; (6) right lateral view; (7) the specimen in the rock; (8) schematic of carapace morphology. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007 Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, p. 107, fig. 4.1.

Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2007b Goniodromites aliquantulus; Schweitzer and Feldmann, p. 126, fig. 2G.

Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazǎr2009 Goniodromites aliquantulus; Schweitzer et al., p. 6.

Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Garassino, Karasawa and Schweigert2010 Goniodromites aliquantulus; Schweitzer et al., p. 59.

Reference Starzyk, Krzemińska and Krzemiński2012 Goniodromites aliquantulus; Starzyk et al., p. 145.

Reference Hyžný, Starzyk, Robins and Kočová Veselská2015 Goniodromites aliquantulus; Hyžný et al., p. 639.

Holotype

An almost complete carapace, LPBIIIart 0150; Oxfordian, Upper Jurassic; WP123, Gura Dobrogei, Romania; by original designation.

Diagnosis

As by Schweitzer et al. (Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007, p. 107, 108).

Occurrence

Oxfordian, Upper Jurassic; crushed limestone near the Kamennomostsky village, Maikop district, Republic of Adygea, Russia, as well as Gura Dobrogea (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007).

Description

Carapace hexagonal, elongated, narrowing anteriorly and posteriorly. Greatest width of carapace occuring in epibranchial regions. Cephalic region, measured from anterior to cervical groove along midline, constituting half of total carapace length. Rostrum bilobed, wide; frontal margins continuous with orbital margin. Outer-orbital angle as well-developed spine. Outer orbital edge with row of small spines. Second large spine posterior to outer-orbital spine. Margins of epibranchial regions each containing four small spines. Margins of branchial regions in anterior part with small spines, at least six but total number unknown. Cervical groove strongly developed, deep, wide, continuous across axis; lateral segment at angle of 80° to axis. Postcervical groove clear, deep, corresponding in width to mesogastric region. Greatest depth of postcervical groove located closer to margins of carapace; in central part barely noticeable. Branchiocardiac groove strongly developed laterally, less strongly developed in axial direction, continuous across axis. Lateral segments of branchiocardiac groove merging posteriorly with cardiac region, continuing to intersect with posterior margin. Segments of branchiocardiac groove barely noticeable in cardiac region. Epigastric regions spherical, small, located near rostrum, with apices directed toward each other. Mesogastric region clearly visible in both posterior and anterior parts; posterior part subtriangular, slightly swollen, bounded by pair of small grooves disappearing at approximate midlength of protogastric region; anterior part located between epigastric regions, elongated along axis of carapace. Protogastric and hepatic regions confluent, slightly swollen, separated from mesogastric region in anterior and posterior parts. Epibranchial regions slightly swollen, laterally elongated, bounded by branchiocardiac and cervical grooves; postcervical groove extending through epibranchial region. Cardiac region subtriangular, slightly swollen, merging posteriorly with flattened large branchial regions. Remainder of branchial regions broad, poorly ornamented, undifferentiated. Height of carapace highest in cardiac region. Posterior margin of carapace wide, entire, curved toward anterior part. Dorsal carapace ornamented with small, rough rows of tubercles over entire surface; largest tubercles closer to margins of carapace.

Material examined

Two almost complete carapaces, MWO 1 nos. 12875-1, 12875-2.

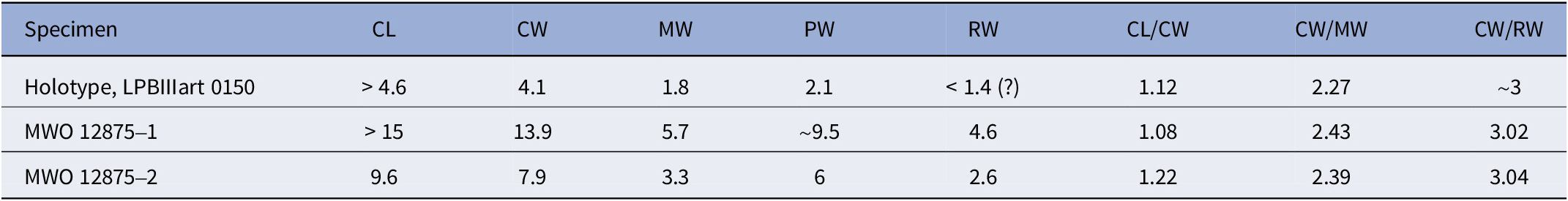

Measurements

Measurements (in mm) taken on specimens of Goniodromites aliquantulus are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Measurements (in mm) of specimens of Goniodromites aliquantulus Schweitzer, Feldmann, and Lazǎr, 2007

Remarks

The new specimens are referred to Goniodromites aliquantulus based upon their longer-than-wide carapace, weak dorsal ornamentation, and short metagastric region. Other species are more equal in terms of length and width (Goniodromites bidentatus, Goniodromites cenomanensis, Goniodromites laevis, Goniodromites polyodon) and all other referred species have larger granules or scabrous ridges on the dorsal carapace, which Goniodromites aliquantulus lacks. The holotype of Goniodromites aliquantulus, described by Schweitzer et al. (Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Lazăr2007, fig. 4.1), has no front part of the carapace. The material that we describe expands the understanding of the morphology of this species, and in particular, we can now say that the rostrum of Goniodromites aliquantulus is bilobed and wide. We also note that the new specimens of this species are significantly larger than the holotype from Romania. However, the ratios of measurement parameters between Caucasian specimens and the holotype are approximately the same (Table 2). These measurements also show small variability in the ratios of the parameters. For example, the ratio of length of carapace to maximum carapace width in two Caucasian specimens is 1.08 in the large specimen and 1.22 in the small one. This value roughly corresponds to the ratio of these parameters in the holotype (Table 2). We consider these variations as intraspecific variability.

Discussion

As previously noted, many researchers (Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008; Fraaije et al., Reference Fraaije, Van Bakel, Guinot and Jagt2013; Schweigert, Reference Schweigert2021; Van Bakel and Guinot, Reference Van Bakel and Guinot2023) have shown that brachyuran fossils in the Middle Jurassic are quite rare. The same is observed in the geological record of Anomura, in particular for Paguroidea, which has similarly high diversity but is recorded only in the Tithonian (Fraaije et al., Reference Fraaije, Van Bakel, Jagt, Charbonnier, Schweigert, Garcia and Valentin2022).

However, in the Late Jurassic, coral and sponge-microbial reefs began to spread widely, especially confined to the edge of the warm waters of the Tethys Ocean. Therefore, in deposits of this geological age, especially in southern Europe, siliceous sponge-microbial and coral facies are widespread. Many researchers (Klompmaker et al., Reference Klompmaker, Schweitzer, Feldmann and Kowalewski2013, Reference Klompmaker, Starzyk, Fraaije and Schweigert2020; Schweigert, Reference Schweigert2021) have linked the diversification of crabs in these paleobiogeographic areas to the presence of reefs.

Findings of Goniodromites aliquantulus, as well as other species of Goniodromites, are often confined to carbonate prereef and reef facies. Various species of Goniodromites from the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Europe and Asia (Japan) demonstrate that the intervening deposits are not limited to a single type. For example, Klompmaker et al. (Reference Klompmaker, Feldmann and Schweitzer2012, table 1) noted a wide diversity of ecological settings for this genus: sponge microbial limestones, coral reefal limestones, sponge limestones, limestones (without specification), and sands/marls/chalks and shale. Thus, Goniodromites was apparently a eurytypic crab and lived in a wide variety of environments. For example in Romania, Schweitzer et al. (Reference Schweitzer, Lazăr, Feldmann, Stoica and Franţescu2017) noted that the depositional conditions of the rocks in which Goniodromites species occur are variable and can be represented by sponge limestone, coral limestone, algal limestone, and even siliciclastic facies. However, it is interesting that the Romanian Goniodromites aliquantulus, like the Caucasian occurrence, comes from sponge limestone of Oxfordian age. Thus, Goniodromites is a widespread, commonly occurring genus in Jurassic rocks of Europe, and it has been recovered from coral, sponge-algal, and nonreefal limestones as well as lithographic limestones (Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2007a; Feldmann et al., Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Schweigert, Robins, Karasawa and Luque2016).

The discovery of Gastrosacus wetzleri expands the geographic distribution of this species, previously found only in the Kimmeridgian of Germany and the Oxfordian of England (Robins et al., Reference Robins, Fraaije, Klompmaker, Van Bakel and Jagt2015). This suggests that both Goniodromites and Gastrosacus were eurytypic genera and survived in many types of environments. This could explain why both genera are so speciose and widespread in the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Europe. Findings of fossil remains of the brachyuran Goniodromites aliquantulus and the anomuran Gastrosacus wetzleri from the Oxfordian in the North Caucasus indicate an interconnected paleobiogeographical decapod fauna in the Late Jurassic in the Tethys basins.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Sukhot’ko and K. Belikova for donating specimens for this research; D. Kiselev (Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University, Yaroslavl, Russia) for help with searching for literature and photographs of localities and to the reviewers for their detailed and thorough revision of the paper, namely C. Robins (University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, USA) and N. Starzyk (Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences), also Guest Editor for this paper A. Klompmaker (University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, USA). The research was supported by RSF (project no. 22-14-00258).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.