Introduction

Wilms tumor (WT) is the fourth most frequently diagnosed childhood cancer globally and the most common pediatric renal tumor, accounting for 6–7% of all childhood cancer diagnoses. Reference Bray, Laversanne and Sung1,Reference Egeler, Wolff and Anderson2 Affecting approximately one in 10,000 children, WT primarily occurs in children younger than five years, with a median age at diagnosis between 2 and 3 years. Reference Brok, Mavinkurve-Groothuis and Drost3,Reference Rančelytė, Nemanienė and Ragelienė4 Over the past few decades, survival rates for WT have dramatically improved in high-income countries, with long-term survival exceeding 90%, largely due to the adoption of multidisciplinary approaches that integrate surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Reference Dome, Graf and Geller5 However, significant disparities persist between high-income and low-income countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, overall survival (OS) rates range from 11 to 46%, highlighting the challenges of managing WT in resource-limited settings. Reference Berhe, Vanderpuye and Kassam6,Reference Israels, Pidini and Borgstein7

The global incidence of Wilms tumor exhibits geographical variation, with higher rates reported in North America and Europe compared to Africa and Asia. Reference Stiller and Parkin8 In sub-Saharan Africa, studies suggest that late presentation, advanced tumor stages at diagnosis, and limited healthcare resources significantly contribute to poorer survival rates compared to high-income countries. Reference Ajayi, Adeodu and Nkanginieme9 Despite its public health significance, data on the presentation, clinicopathological features, management and outcomes of Wilms tumor in Ghana remain sparse, making it difficult to design interventions tailored to the local context.

The presentation of Wilms tumor is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic abdominal masses detected incidentally to cases with symptoms such as hematuria, hypertension or systemic manifestations of metastatic disease. Reference Dome, Graf and Geller5 The clinicopathological characteristics, including histological subtypes and tumor staging, are critical determinants of prognosis. Favorable histology is associated with a five-year survival rate exceeding 90% in high-resource settings, while anaplastic histology significantly worsens prognosis. Reference Hingorani, Seibel and Wilkinson10

There are two main approaches to the management of WT based on either the International Society of Pediatric Oncology – Renal Tumor Study Group (SIOP – RTSG) or the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group (NWTSG) protocol. Both protocols have been associated with comparable survival rates of approximately 90% in high-resource settings. Reference Dome, Graf and Geller5 Per the SIOP protocol, which is widely used in Ghana, histopathological features of the tumor are used to stratify patients into three prognostic groups: low (completely necrotic, cystic partially differentiated), intermediate (regressive, stromal, epithelial, mixed type and focal anaplasia) and high risk (diffuse anaplasia, blastemal type). Management of WT in resource-limited settings is fraught with challenges, including inadequate access to pediatric oncologists, limited availability of radiotherapy and high rates of treatment abandonment. Reference Chirdan, Bode-Thomas and Chirdan11 Outcomes are further compounded by malnutrition, treatment failure and socio-economic barriers, such as financial constraints and cultural perceptions of cancer treatment. Addressing these barriers requires a comprehensive understanding of the local disease burden. Reference Cunningham, Klug and Nuchtern12,Reference Ekenze, Nwangwu and Ezomike13

This study examines the patterns of presentation, clinicopathological characteristics, management and outcomes of Wilms tumor in Ghana, providing a comprehensive analysis of its impact in a resource-limited setting. It evaluates disease-free survival (DFS) and OS rates and explores the influence of key prognostic factors, including pathological stage, risk stratification, age and gender, on survival outcomes. By comparing the DFS and OS rates observed in Ghana to those reported in high-income countries, the study seeks to identify disparities in outcomes and uncover barriers to optimal care. Furthermore, it provides evidence-based recommendations to strengthen pediatric oncology care in Ghana. These findings aim to bridge critical knowledge gaps, contextualize the outcomes of WT in Ghana within the global landscape and inform strategies to improve survival rates for children with WT in resource-constrained settings.

Methods

This was a descriptive quantitative cross-sectional study conducted at the Oncology Centre and the Pediatric Oncology Unit of a major teaching hospital in Ghana. The study population encompassed all patients diagnosed with WT between January, 2012 and December, 2021. A total population sampling technique was used to recruit all eligible patients who were managed at the study sites during the sampling period. Patients with no histopathological confirmation of WT were not included in the study. Relevant data were extracted from patients’ hospital-based medical records and compiled in a dedicated database for this study. The recorded data included patients’ socio-demographic information and clinical characteristics such as presenting symptoms, performance status and pathological staging. The choice and sequencing of treatment modalities employed in the management of the patients were also recorded. A total of 137 patients with WT were successfully recruited into the study. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were described using descriptive statistics in the form of frequency distribution and percentages. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate the probability DFS and OS. P values < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board prior to the commencement of the study (SBAHS/AA/RAD/10943326/2023). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the patients. The confidentiality of patients’ information was always maintained. The data collected were anonymized with removal of all patient identifying information prior to data analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

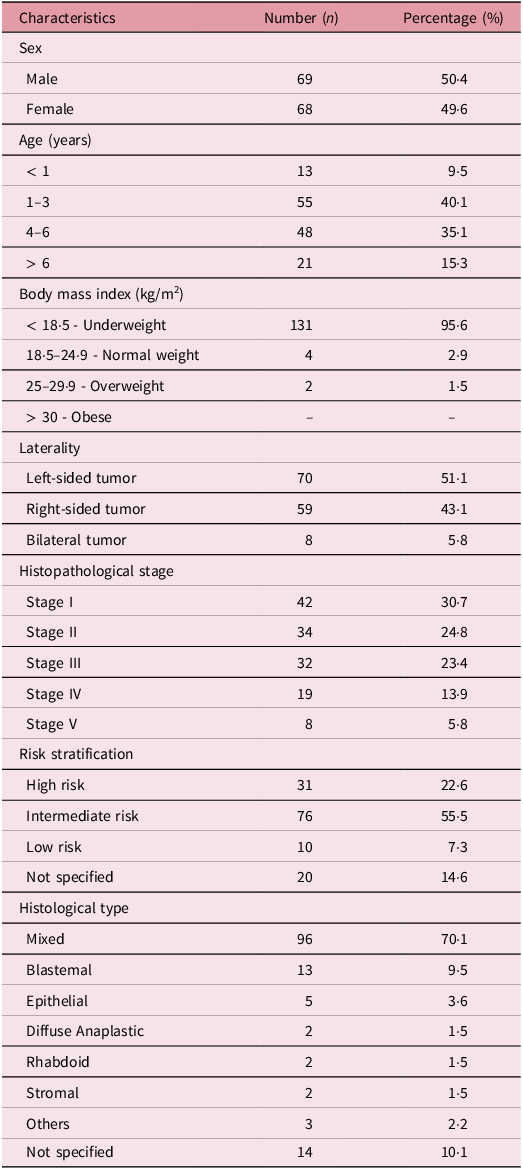

There were 137 participants in the study, out of which 68 (49·6%) were female (Table 1). The mean age was 25 months (SD 30) ranging from 1 month to 11 years (132 months). A considerable proportion were ≤ 3 years (n = 68, 49·6%) whereas 21 (15·3%) were > 6 years. The majority of the patients (n = 131, 95·6%) were underweight whereas 2 (1·5%) were overweight. Only 4 patients (2·9%) had a normal body mass index (BMI). None of the participants were considered obese. In all, 70 patients (51·1%) had left-sided tumors, whereas 59 (43·1%) had right-sided tumors. Also, 8 patients (5·8%) had bilateral disease. Stage I was the most common, 30·7% (n = 42) whereas the least common was stage V (n = 8, 5·8%). A considerable majority had intermediate risk tumors (n = 76, 55·5%) whereas 31 (22·6%) and 10 (7·3%) had high and low risk tumors respectively. A considerable majority of the patients had the mixed histological type of WT (n = 96, 70·1%) whereas 13 (9·5%) had the blastemal type. Also, 5 (3·6%) had the epithelial type whereas 2 (1·5%) each had the diffuse anaplastic, rhabdoid and stromal types.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 137)

Clinical presentation

Weight loss (n = 77, 56%), the presence of an abdominal mass (n = 52, 38%) and abdominal distension (n = 41, 30%) were the top three signs and symptoms experienced by patients as depicted in Figure 1. Also, 32 patients (24%) presented with fever and 29 (21%) with hematuria whereas 25 (18%) presented with abdominal pain. Additionally, 27 patients (20%) presented with other signs and symptoms such as cough, vomiting, anemia and poor feeding.

Figure 1. Clinical presentation of patients diagnosed with Wilm’s tumor.

Pattern of distant metastasis

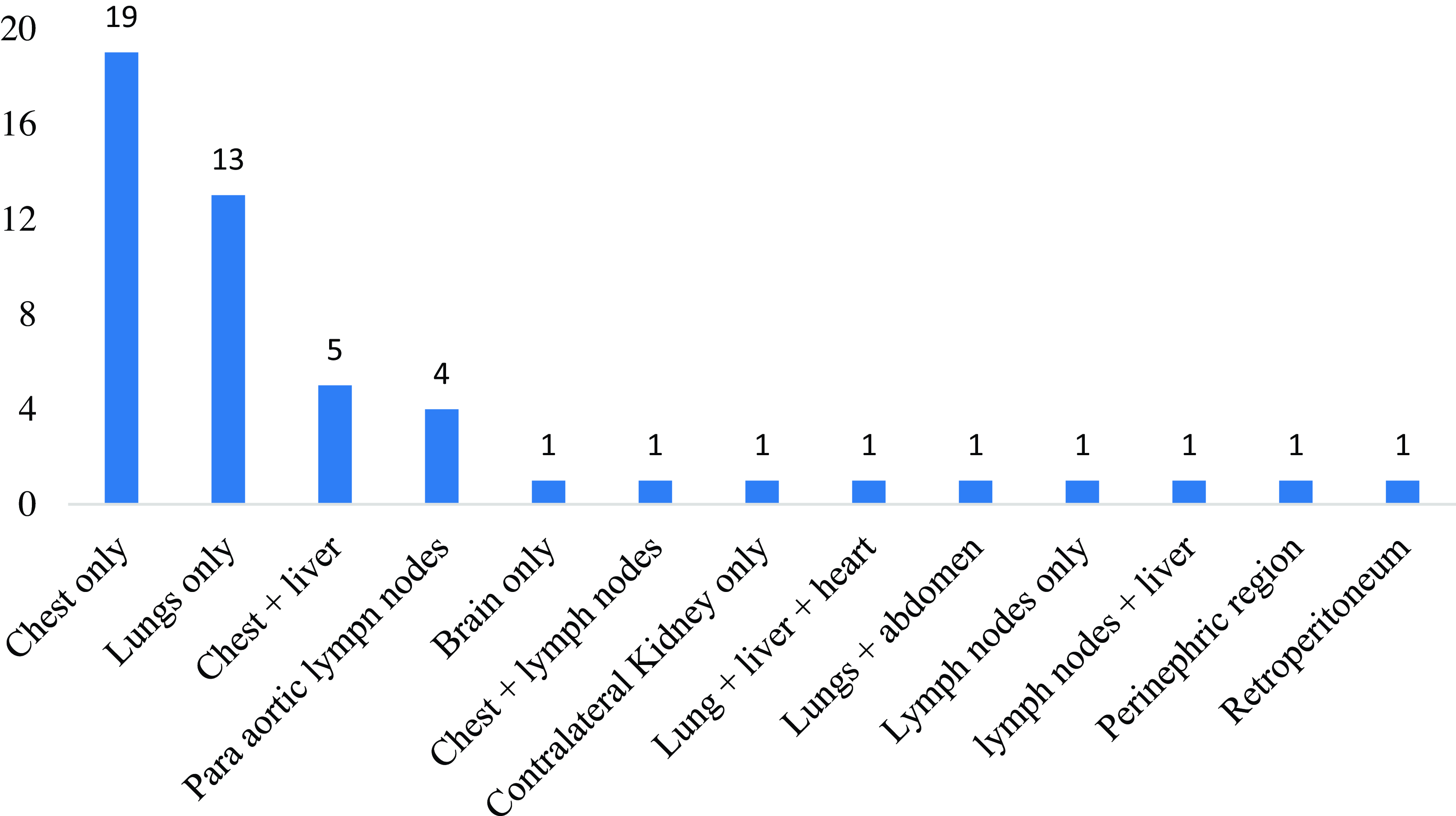

Out of 137 participants, 50 (36·5%) were diagnosed with metastatic disease (Figure 2). In all, 41 patients (29·9%) had a single site of metastasis whereas 8 (5·8%) had double sites of metastasis. Also, 1 patient (0·7%) had triple sites of distant metastasis (lung, liver and heart). The chest (n = 19, 13·8%) and lungs (n = 13, 9·5%) were the most frequent sites of single metastasis. Among patients with double metastatic sites, 5 (3·6%) had distant spread to the chest and liver whereas 1 (0·7%) had concurrent chest and lymph node metastasis.

Figure 2. Distribution of sites of distant metastases (n = 50).

Systemic management with chemotherapy

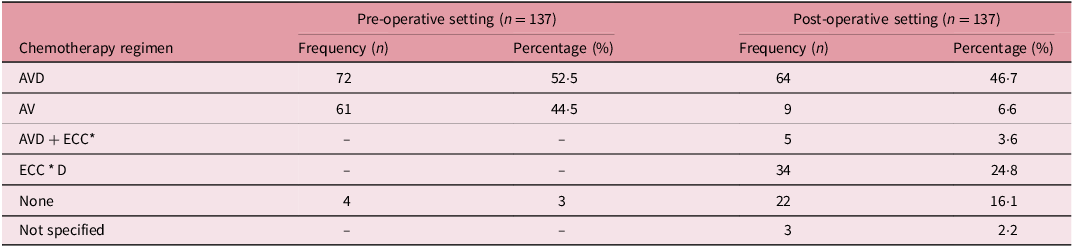

In all, 72 patients (52·5%) received a triple combination regimen comprising vincristine (V), actinomycin D (A) and doxorubicin (D) whereas 61 (44%) were treated pre-operatively with a dual combination regimen of AV according to the SIOP protocol (Table 2). In the post-operative setting, 64(46·7%) were treated with the ‘AVD’ chemotherapy regimen whereas 9 (6·6%) were treated with the AV regimen. Also, 34 (16·1%) were treated with the ‘ECCD’ regimen comprising etoposide (E), cisplatin (C*), cyclophosphamide (C) and doxorubicin (D) whereas 5 (3·6) were treated with the ‘AVD + ECC’ regimen.

Table 2. Distribution of the pre- and post-operative chemotherapy regimens used

A = Actinomycin D; V = Vincristine; D = Doxorubicin; E = Etoposide, C = Cisplatin; C* = Cyclophosphamide.

Surgical management

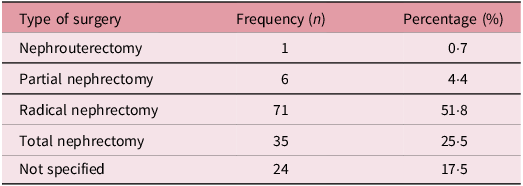

Table 3 shows the distribution of surgical techniques used in the management of the patients with WT. In all, 71 (51·8%) underwent radical nephrectomy whereas 35 (25·5%) underwent total nephrectomy. Also, 6 (4·4%) underwent a partial nephrectomy.

Table 3. Surgical techniques used in the management of the study participants (n = 137)

Nephrouterectomy entails the removal of the kidney, ureter and a portion of the bladder. Partial nephrectomy involves the removal of the cancerous portion of the kidney while preserving the remaining healthy tissue whereas radical nephrectomy refers to the removal of the entire kidney, along with the surrounding fatty tissue, adrenal gland and regional lymph nodes if necessary. Total nephrectomy refers to the removal of the entire kidney without involving other surrounding structures.

Management with radiotherapy

In all, 49 patients (35·8%) were treated with radiotherapy. Notably, 22 (16·1%) were treated to 21·6Gy in 12 fractions delivered over 2·5 weeks whereas 15(10·9%) were treated to 10·8Gy in 6 fractions delivered over 1·5 weeks whereas 6 patients (4·4%) were treated to 12Gy in 8 fractions delivered over 1·5 weeks (Table 4). A considerable majority of the patients (n = 32, 60·5%) commenced radiotherapy more than 14 days after undergoing surgery.

Table 4. Characteristics of the radiation treatment received by study participants

Survival outcomes

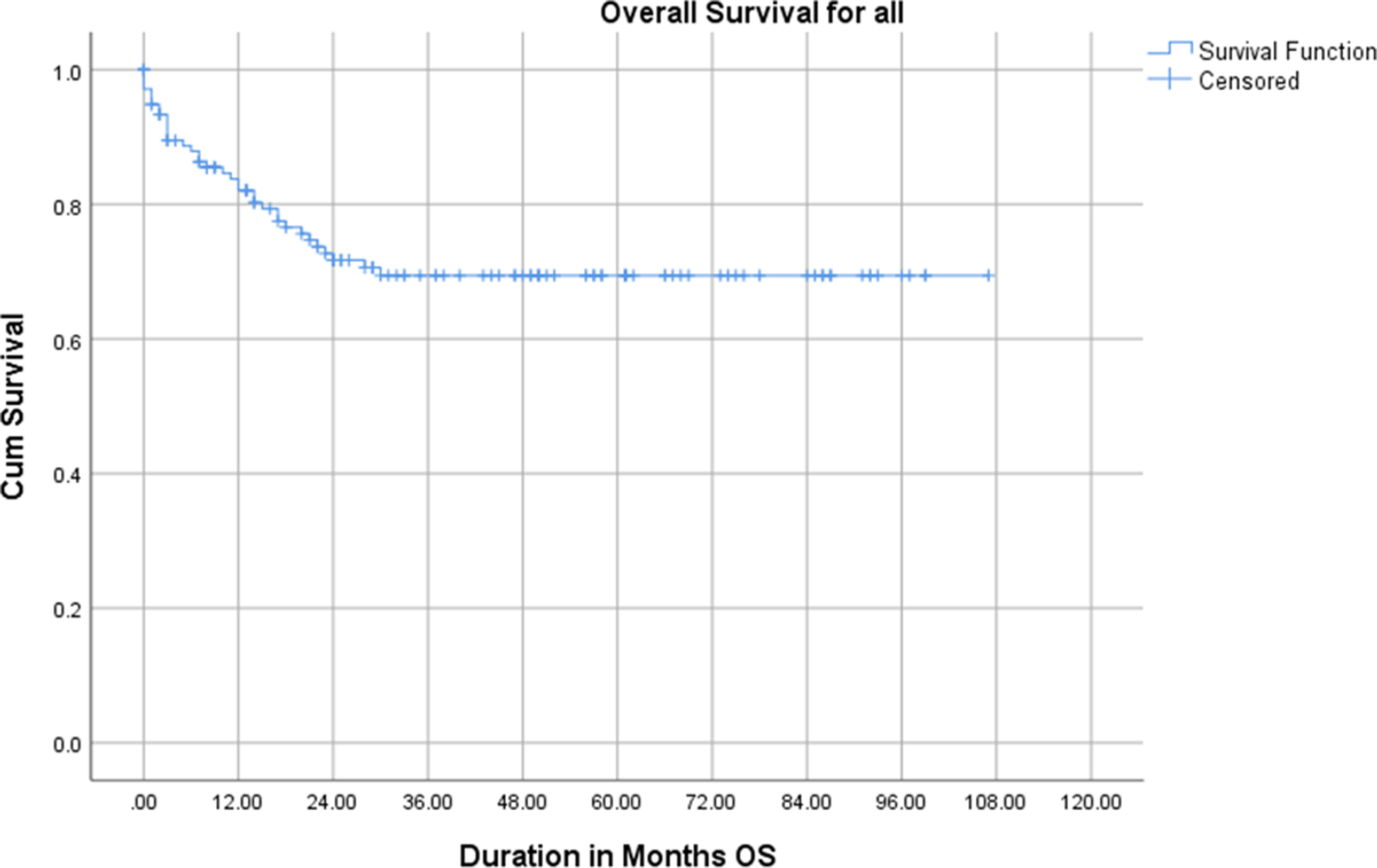

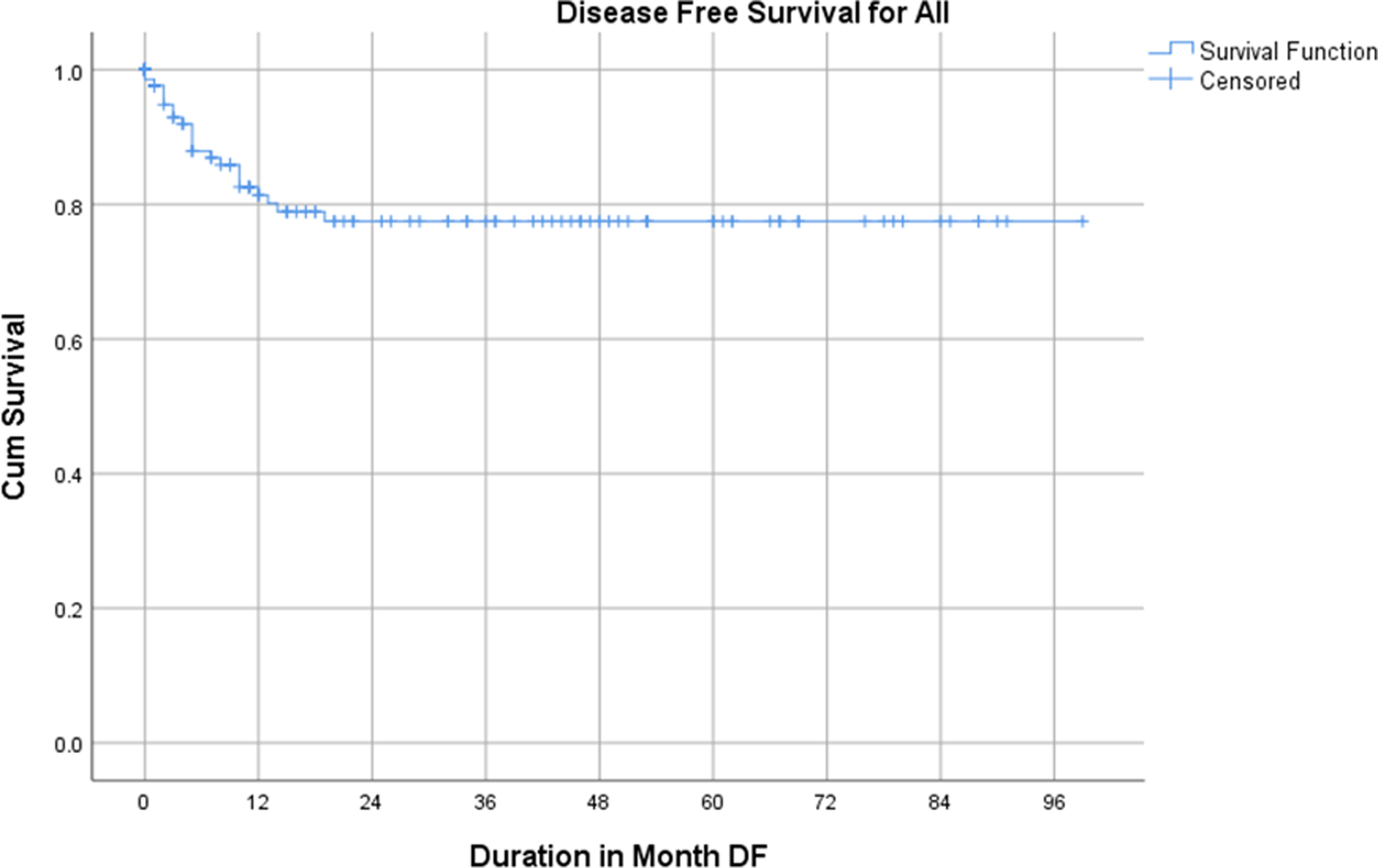

The 2- and 5-year OS were 75% and 70% respectively, whereas the 2- and 5-year DFS rates were both 79% as show in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Overall survival of the study participants.

Figure 4. Disease-free survival of the study participants.

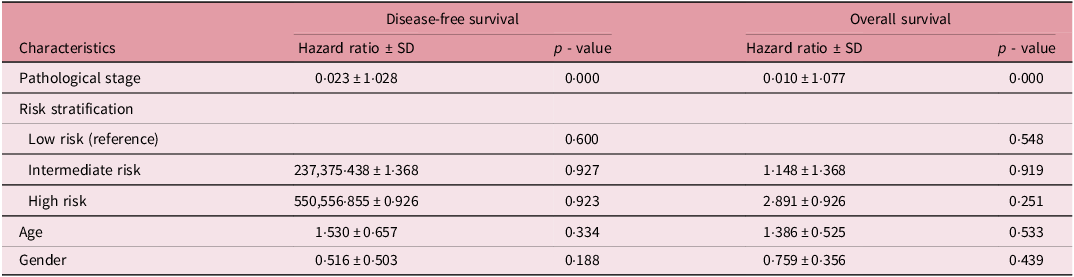

The Cox regression analysis for DFS and OS demonstrates that pathological stage is a significant prognostic factor for both outcomes, with hazard ratios (HR) of 0·023 ± 1·028 (p = 0·000) and 0·010 ± 1·077 (p = 0·000), respectively, indicating a strong inverse relationship between pathological stage and survival. Risk stratification analysis, using low-risk patients as the reference group, showed no statistically significant differences in DFS or OS among intermediate- and high-risk groups, with p-values ranging from 0·600 to 0·923 for DFS and 0·548 to 0·919 for OS (Table 5). However, the HR for high-risk patients was higher than for intermediate-risk patients in both DFS and OS, suggesting poorer outcomes in the high-risk category, although not statistically significant. Additionally, age and gender were not significant predictors of either DFS or OS, with HRs close to 1 and p-values > 0·05. These findings highlight the pivotal role of pathological stage in determining survival outcomes, while age, gender and risk stratification were not robust independent predictors in this study.

Table 5. Cox regression analysis for disease-free and overall survival

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the patterns of presentation, clinicopathological characteristics, management strategies and outcomes of WT in Ghanaian paediatric patients managed at a major tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana. The results are significant in highlighting unique characteristics and outcomes within this limited-resource setting, with implications for improving paediatric oncology care in the subregion. The mean age of 25 months, with nearly half of the participants aged ≤3 years, aligns with the global trend where WT predominantly affects young children. Reference Dome, Perlman and Graf14 The balanced sex distribution (49·6% female and 50·4% male) is consistent with existing literature suggesting no significant gender disparity in WT incidence. Reference Green15 The striking prevalence of underweight participants (95·6%) underscores the impact of malnutrition, a common comorbidity in resource-constrained settings. Reference Sitaresmi, Mostert and Sutaryo16 Malnutrition can exacerbate treatment toxicities and worsen outcomes, calling for nutritional support integration in pediatric oncology care. The predominance of left-sided tumors (51·1%) and intermediate-risk tumors (55·5%) are comparable to findings from other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where delayed diagnosis often leads to a predominance of intermediate or advanced disease stages. Reference Graf, Tinteren and Bergeron17 Notably, the proportion of bilateral disease (5·8%) aligns with global data, which estimates bilaterality in 5–7% of cases. Reference Dome, Perlman and Graf14

The mixed histological type was the most common subtype (70·1%), as expected, given its global prevalence as the typical presentation of WT. Reference Green15 However, the presence of high-risk histological types such as blastemal and diffuse anaplastic types (9·5% and 1·5%, respectively) highlights the need for tailored treatment strategies to address more aggressive disease presentations. The relatively high prevalence of stage I disease (30·7%) is encouraging, suggesting that some cases are being detected early. However, the proportion of advanced-stage disease (stages III–V, 43·1%) remains concerning, reflecting potential delays in diagnosis and referral systems. In children who are otherwise healthy, abdominal swelling and a flank mass are the most frequently reported symptoms. Reference Mullen, Chi and Hibbitts18 However, the findings on clinical presentation reveal the non-specific nature of WT signs and symptoms, with weight loss (56%) and abdominal mass (38%) being the most frequent signs at presentation. These symptoms, while consistent with global data, are often attributed to other illnesses in LMICs, delaying diagnostic imaging and referral. Reference Pritchard-Jones, Graf and Tinteren19 Hematuria and abdominal pain, reported in 21% and 18% of cases, respectively, are less commonly seen but are critical diagnostic cues that should prompt further investigation. Metastatic disease was present in 36·5% of cases, with the chest and lungs being the most frequent sites, a finding consistent with existing literature. Reference Green15,Reference Verschuur, Van Tinteren and Graf20 The presence of multiple metastatic sites in 6·5% of cases emphasizes the aggressive nature of the disease in some patients and underscores the importance of early detection and comprehensive staging.

A previous study in Ghana found that there was more advanced pathological staging than clinical stage despite neoadjuvant chemotherapy which was attributed to suboptimal preoperative staging among patients treated between 2005 and 2014· Reference Berhe, Vanderpuye and Kassam6 Preoperative chemotherapy is recommended for all patients according to SIOP guidelines. The most common chemotherapy agents used in the management of WT include Vincristine, Actinomycin D and Doxorubicin. Reference Vujanić, Gessler and Ooms21 The predominance of the AVD regimen (52·5% pre-operatively, 46·7% post-operatively) aligns with international protocols for intermediate-risk and advanced-stage WT. Reference Dome, Perlman and Graf14 The use of the ECCD regimen (24·8%) for high-risk tumors reflects efforts to optimize outcomes for patients with poor prognostic factors. However, the relatively high proportion of patients not receiving chemotherapy post-operatively (16·1%) raises concerns about treatment completion rates and underscores the need for robust patient follow-up systems.

Following preoperative chemotherapy, SIOP recommends appropriate renal surgery. Radical nephrectomy was the most common surgical technique (51·8%), consistent with global practices. However, the relatively high rate of total nephrectomy (25·5%) without sparing surrounding structures could reflect limited surgical expertise or resources in this setting. The low rate of nephron-sparing surgeries (4·4%) is noteworthy, as this technique is associated with improved renal function preservation and long-term outcomes, particularly in bilateral or unilateral tumors. Reference Graf, Tinteren and Bergeron17 Only 35·8% of patients received radiotherapy, a lower proportion than expected based on global protocols, which recommend radiotherapy for most high-risk cases. Reference Green15 This gap may reflect challenges in access to radiotherapy facilities, equipment or delays in initiating treatment. Radiotherapy should be started between 9 and 14 days after surgery according to the SIOP RTSG 2016 UMBRELLA protocol. Reference Vujanić, Gessler and Ooms21 A previous study reported a long interval between surgery and radiotherapy with a median interval of 36·6 days. Reference Berhe, Vanderpuye and Kassam6 Notably, 60·5% of patients who received radiotherapy started more than 14 days after surgery, which could potentially compromise treatment efficacy. Reference Pritchard-Jones, Graf and Tinteren19 Efforts to reduce delays and improve access to radiotherapy are critical for optimizing outcomes.

Berhe et al., Reference Berhe, Vanderpuye and Kassam6 reported 2- and 5-year OS for WT treated with radiotherapy in Ghana to be 56% and 44% respectively. However, the 2- and 5-year OS rates of 75% and 70%, respectively, and DFS rates of 79% at both time points, in this study reflect the challenges and progress in managing WT in Ghana. The results indicate that while survival rates are encouraging, they remain lower than those reported in high-income countries (HICs), where 5-year OS rates exceed 90%. Reference Dome, Graf and Geller5,Reference Green, Lange and Pein22 This discrepancy can be attributed to late stage diagnosis, limited access to multimodal treatment and resource constraints in LMICs. The relatively favorable 5-year DFS rate highlights the potential effectiveness of treatment when patients adhere to protocols, despite systemic challenges. The Cox regression analysis identifies pathological stage as a significant prognostic factor for both OS and DFS, aligning with global literature that underscores the critical impact of stage at diagnosis on survival outcomes. Reference Hale, Zhang and Li23 Advanced-stage disease (stages III–V) correlates with poorer survival outcomes due to higher metastatic burden and greater treatment complexity. Reference Green, Lange and Pein22 Comparatively, studies in other LMICs, such as Nigeria and India, report similar trends where late-stage diagnosis compromises survival outcomes. Reference Gupta, Bonilla and Valverde24,Reference Ajayi, Campbell and Amoah25 This reflects the shared challenges of delayed diagnosis and inadequate access to care in LMIC settings.

The absence of statistically significant differences in survival outcomes based on risk stratification, age or gender contrasts with findings in HICs, where high-risk histological subtypes and younger age groups are associated with poorer outcomes. Reference Dome, Graf and Geller5 This discrepancy may stem from limitations in sample size and stratification within the study cohort, as well as possible under-reporting of high-risk histological subtypes due to diagnostic resource constraints. When compared to local studies in Ghana or neighboring regions, this study adds valuable insights. For instance, a previous Ghanaian study reported lower survival rates due to higher rates of treatment abandonment. Reference Nyarko, Lamptey and Addo26 The current findings suggest modest improvements, likely attributable to increasing awareness and gradual improvements in pediatric oncology care. However, the persistence of delayed treatment initiation and limited access to essential modalities such as radiotherapy and advanced surgical techniques continues to hinder outcomes, as also reported in other African studies. Reference Ajayi, Campbell and Amoah25,Reference Israels, Molyneux and Nyirenda27 The study underscores critical gaps in the management of WT in Ghana, including diagnostic delays, limited access to comprehensive care and suboptimal adherence to treatment protocols. Addressing these challenges requires strengthening early diagnosis and referral systems through public awareness campaigns and training healthcare professionals on recognizing early WT signs and symptoms. Enhancing multidisciplinary care by fostering continued collaboration among pediatric oncology teams, surgeons and radiation oncologists is essential for optimizing treatment delivery. Improving access to radiotherapy through infrastructure investment and integrating nutritional support into oncology care are also pivotal.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, its retrospective design may have introduced selection bias and limited the ability to control for potential confounding variables. Additionally, the study relied on hospital records, which may be incomplete or inconsistent, potentially affecting the accuracy of the data on presentation, clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes. Another significant limitation is the lack of long-term follow-up data for some patients, which restricts the ability to evaluate late recurrences and long-term survival. Moreover, the absence of molecular and genetic analysis, which could provide deeper insights into tumor biology and risk stratification, is a notable constraint. Finally, comparisons with high-income countries were based on literature rather than direct cohort matching, which may limit the robustness of international comparisons. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the challenges of managing Wilms tumor in a resource-limited setting and highlights critical areas for improvement.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the patterns of presentation, clinicopathological characteristics, management and outcomes of Wilms tumor (WT) in Ghana, revealing significant disparities compared to high-income countries. The findings show that while the 2- and 5-year OS rates of 75% and 70%, respectively, and DFS rates of 79% represent an improvement over previous studies in Ghana, they remain suboptimal compared to outcomes in high-income countries. Late-stage disease at diagnosis and challenges in accessing comprehensive care persist as major barriers to achieving optimal outcomes. Pathological stage was the most significant prognostic factor for both OS and DFS, emphasizing the importance of early detection and timely intervention. Despite some progress, this study highlights significant challenges in ensuring timely and comprehensive care. Addressing delays in diagnosis, strengthening multidisciplinary treatment approaches and improving access to essential therapies such as radiotherapy and nephron-sparing surgery are critical steps forward. Socio-economic barriers, including treatment abandonment and limited resources, must also be addressed through targeted interventions.

Acknowledgements

Authors express their profound gratitude to the management of the Radiotherapy and Oncology Centre for their support and tremendous contribution to this study.