Introduction

The upsurge in income and wealth concentration into the hands of a few ‘super-rich’ people (Hay and Beaverstock, Reference Hay and Beaverstock2016) and the increasing economic inequality over the last few decades (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2015; Piketty, Reference Piketty2017) have been widely documented. These trends compromise the democratic and meritocratic ideals of our societies (Sayer, Reference Sayer2015) and the satisfaction of basic needs (Fanning et al., Reference Fanning, O’Neill, Hickel and Roux2022; Millward-Hopkins, Reference Millward-Hopkins2022). Furthermore, the polluting lifestyles of an increasing number of millionaires accentuates the climate emergency (Chancel and Piketty, Reference Chancel and Piketty2015) and may even prevent our societies from achieving carbon neutrality (Gössling and Humpe, Reference Gössling and Humpe2023). Within this unprecedented context, we argue that proposals directly regulating the level of income and wealth – such as income and wealth caps – deserve the attention of social policy scholarship. This paper focuses on maximum income as a novel eco-social policy that has the potential to address the dual crises of accelerating inequality and the climate emergency we are facing, by constraining the detrimental ecological impacts of our current economic system that allows the extreme accumulation and concentration of income and wealth in the hands of a few (Buch-Hansen and Koch, Reference Buch-Hansen and Koch2019; François et al., Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023).

Social policy scholarship has long been preoccupied with the discussion about how to alleviate poverty and reduce inequality by means of improving the material standards of those at the lower end of the income distribution. In contrast, scant attention has been paid to the population occupying the opposite end of that distribution, and whether there could be any potential for social policy interventions to curb the trend of the richest minority pulling away from the rest (but see for instance Orton and Rowlingson, Reference Orton and Rowlingson2007; Rowlingson and Connor, Reference Rowlingson and Connor2011; Sayer, Reference Sayer2015). This oversight may misdirect social policy discussions when, for instance, public opinion about welfare states or redistributive policies is linked to the growing disparity in material conditions driven by those with extremely high incomes (Hecht et al., Reference Hecht, Burchardt and Davis2022; McCall, Reference McCall2013). It also means that efforts to understand distributive preferences have mostly centred on the sense of justice focusing on the deservingness of those in need of social transfers (Laenen, Reference Laenen2020; Van Oorschott, Reference Van Oorschott2000; Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Heuer and Mau2018). As Rowlingson and Connor (Reference Rowlingson and Connor2011) have argued, however, we can also imagine social policy interventions directly addressing the unequal distribution of income and wealth, as well as extreme wealth concentration, by applying the concept of deservingness to the rich. These authors also suggest introducing measures ‘to limit the amount of income and wealth that individuals receive in the first place’ (Rowlingson and Connor, Reference Rowlingson and Connor2011, p. 447) to address the increasing problem of inequality. Despite the low incidence of policy discussions regulating the rich, we argue that ‘shifting the focus from the super-poor to the super-rich’ (Otto et al., Reference Otto, Kim, Dubrovsky and Lucht2019) is an urgent task given the numerous calls for this field to engage with the climate emergency (Dukelow and Murphy, Reference Dukelow and Murphy2022; Gough, Reference Gough2017; Hirvilammi et al., Reference Hirvilammi, Häikiö, Johansson, Koch and Perkiö2023; Koch, Reference Koch2022; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Anderson and Thomson2023).

In recent years, the idea of imposing caps on income, wealth or excessive consumption has been much more prevalent in the literature on sustainable welfare and eco-social policies (Bärnthaler and Gough, Reference Bärnthaler and Gough2023; Gough, Reference Gough2021). By bringing degrowth literature and ecological economics into conversation with social policy, these scholars discuss the idea of imposing limits on our material conditions to avoid ecological overshoots (Fanning et al., Reference Fanning, O’Neill, Hickel and Roux2022), which in turn can aggravate already existing social problems or lead to new ones. Within this new paradigm of sustainable welfare and eco-social policy, the social and environmental challenges are considered in an integrated manner and the promise of eternal economic growth is challenged (Fritz and Lee, Reference Fritz and Lee2023; Koch, Reference Koch2022). The popularity of new eco-social policies such as meat taxes, limits on housing ownership or a maximum income has been studied in this emerging research field. With regard to maximum income, previous studies exploring public support (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Emilsson, Fritz, Koch, Johansson and Hildingsson2023; Koch, Reference Koch2022; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Koch and Alkan-Olsson2023; Robeyns et al., Reference Robeyns, Buskens, van de Rijt, Vergeldt and van der Lippe2021) have predominantly been conducted using quantitative survey methods. The results indicate that such policy proposals do not have widespread public support, yet a deeper understanding of this is not provided. This article fills this gap and aims to understand how people reason about the idea of capping the maximum level of income and whether there is any potential to increase public support for such an idea, depending on how maximum income is designed. The article therefore also responds to the recent calls to study public policy support focusing not only on individual- and country-level explanatory factors but also on the policy design factors that are most amenable to interventions (Heyen and Wicki, Reference Heyen and Wicki2024).

While the literature highlights that regulating the wealthy can target both income and wealth – recognising that the distinction between these two concepts becomes blurred at the top of the distribution – this research focuses on maximum income for three main reasons. Firstly, compared with wealth caps, the concept of maximum income has garnered more attention in the literature (Fromberg and Lund, Reference Fromberg and Lund2024), and this research aims to contribute to this emerging field. Secondly, examining the acceptability of a maximum income seemed more relevant, as limits on wealth appear to have even less public support (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Ramoglou, Savva and Vlassopoulos2024; Robeyns et al., Reference Robeyns, Buskens, van de Rijt, Vergeldt and van der Lippe2021). Thirdly, Buch-Hansen and Koch (Reference Buch-Hansen and Koch2019) argue that it would probably be more complex to implement wealth caps, whereas the introduction of a maximum income through a 100 per cent tax could be seen as an extension of existing tax systems in Western countries.

This paper extends our previous work on income and wealth caps and draws upon the analytical framework we developed in François et al. (Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023). While this initial publication was based on a literature review and a description of four historical cases, this new study adds an empirical dimension to our research. It is based on fifty qualitative interviews using vignettes that were conducted in the French-speaking part of BelgiumFootnote 1 during 2023. Briefly, the research findings present a typology of four logics of thinking that illustrate ideological divergence. They also highlight that concerns about implementation are shared by both the opponents and the supporters of maximum income, and that several trade-offs are worth considering when designing a maximum income policy that can secure broad support. Finally, the paper discusses how to overcome various barriers that have been identified and concludes with policy implications.

Literature review

The rationale and potential effects of maximum income policy have been discussed in different fields of research, including in ecological economics (Daly, Reference Daly1996), in de-growth and post-growth literature (Buch-Hansen and Koch Reference Buch-Hansen and Koch2019; François et al., Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023), in relation to moral philosophy and a social justice perspective (Burak, Reference Burak2013; Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2024; Robeyns et al., Reference Robeyns, Buskens, van de Rijt, Vergeldt and van der Lippe2021) and lastly in close connection with social policy discussions, where a maximum income’s potential to alleviate inequality has been more explicitly articulated (Concialdi, Reference Concialdi2018; Ramsay, Reference Ramsay2005; Pizzigati, Reference Pizzigati2018). This diversity involves the use of multiple concepts. ‘Maximum wage’ and ‘maximum income’ – also referred to as an ‘income cap’ – refer to the idea of setting a limit on how much a person can earn. The maximum wage applies solely to income earned from labour, whereas the maximum income extends to all forms of income, including capital gains such as rent and dividends. The concepts of a ‘riches line’ and ‘affluence line’ pertain to the idea of a more equitable distribution of resources by establishing a threshold beyond which individuals should not earn additional income, because doing so would undermine the ability of other members of society to meet their basic needs. For instance, building on the concept of an ‘affluence line’ (Drewnowski, Reference Drewnowski1978; Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2006), Concialdi (Reference Concialdi2018) identifies ‘the level of income above which all extra incomes would be transferred to the rest of the population to enable all members of the society to fully participate in it’ (Concialdi, Reference Concialdi2018, p. 11). The study empirically identifies the level at which maximum income could be defined in several European countries, and suggests that the existing level of aggregated incomes in countries such as France, Ireland and the UK could be ‘enough’ to achieve needs satisfaction for all inhabitants of these countries, should the incomes above the identified affluence lines be distributed to ensure the necessary minimum standards for everyone.

When it comes to studies investigating public support for maximum income, Burak’s (2013) comprehensive research on US citizens’ tolerance for high wages indicates that 61 per cent of the US population supports a cap on salaries, with 20 per cent in favour of setting the limit at $1 million. The study identifies three socio-economic characteristics that are associated with the level of support, namely, that being male, being highly educated and having a very high income are correlated with a lower level of support for an income cap. It is noteworthy that Burak’s study is the first to collect data on survey respondents’ reasoning about the wage cap, using an open-ended question. The study found that moral justifications are prevalent among the supporters of an income cap, connecting their support to concerns about low-income earners and inequality. Conversely, opponents may disapprove of a cap because it runs counter to the principles of a free market, or because high-income earners are believed to work hard or perform exceptionally.

Another relevant study related to our subject was recently conducted in the Netherlands; it is not specifically investigating the idea of an income cap but rather the concept of ‘rich lines’ (Robeyns et al., Reference Robeyns, Buskens, van de Rijt, Vergeldt and van der Lippe2021). Their survey study found that, regardless of the respondents’ income or educational levels, the vast majority of the Dutch population could identify the threshold level of living standard/consumption level above which any higher income would be regarded as excessive. Nearly half of the respondents believed incomes above €1–3 million per year would render a person ‘extremely rich’, defined as a level above which no one needs more. The same study also found that only a minority of the respondents (11 per cent) agreed with the statement that there should be a maximum or upper limit imposed on disposable monthly income per person in the Netherlands. While people seemed to agree on the level at which one could be considered ‘super-rich’, the normative implications of such judgements and the preferred political measures seem to diverge (see similar results in Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hecht, Burchardt, Gough, Hirsch, Rowlingson and Summers2020).

Finally, the most recent studies exploring public support for maximum income are found in the discussion about maximum income as an eco-social policy in the context of socio-ecological changes towards a post-growth economic paradigm (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Emilsson, Fritz, Koch, Johansson and Hildingsson2023; Koch, Reference Koch2022; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Koch and Alkan-Olsson2023). Two survey studies have recently been conducted in Sweden and show that approximately 25 per cent of the population supports the idea of introducing a cap on incomes. For instance, one proposal suggests that gross annual wages of over €150,000 would be taxed at 100 per cent (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Emilsson, Fritz, Koch, Johansson and Hildingsson2023), while another study tested the support for a maximum income proposal including not only wages but also capital incomes, with a higher threshold of €200,000. Interestingly, the level of support for this proposal turned out to be similar, at 26 per cent (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Koch and Alkan-Olsson2023). These studies found that attitudes towards distributive justice and redistribution are important predictors for supporting maximum income. In both studies, however, a relatively high proportion of respondents chose the ‘neutral’ answer or skipped the question, indicating that the idea itself is perhaps too novel or unintelligible for survey respondents without further explanations about how a maximum income might work in practice or what the policy effects might be.

This summary of public support for maximum income reveals the prevalence of quantitative approaches that leave aside the question of how to understand the support or opposition from a qualitative perspective. In addition, no empirical research has previously addressed possible links between the design of a maximum income and public support, as has been done in recent studies about public support for differently designed basic income schemes (Laenen et al., Reference Laenen, Van Hootegem and Rossetti2023; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020). Regarding the design of a maximum income, it is only recently that François et al. (Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023) suggested a framework identifying the main components to consider. This paper therefore addresses these research gaps by conducting an in-depth qualitative enquiry.

Methodology

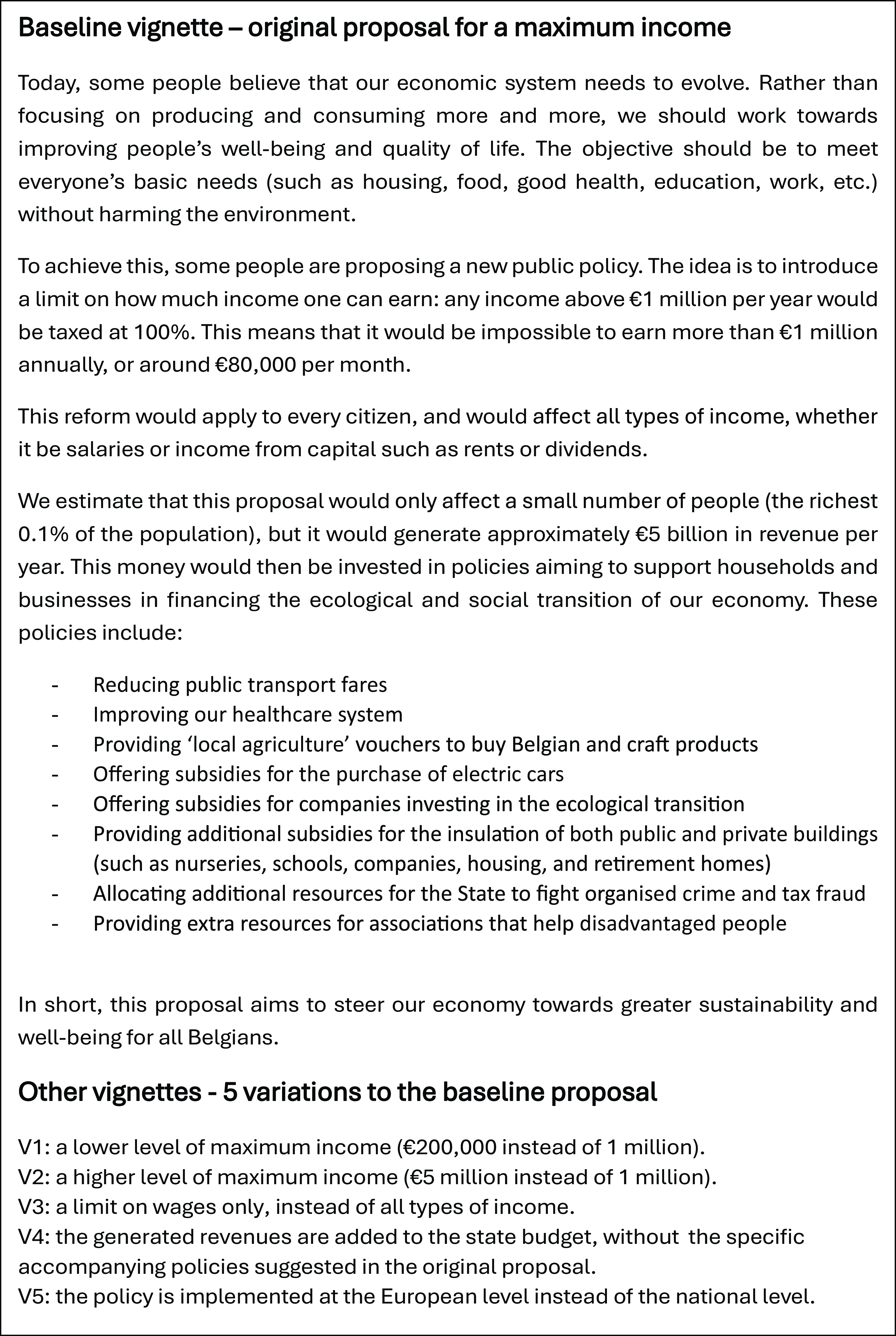

Based on qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews, the study aims to explore how people reason about the idea of maximum income and whether the different ways in which it is designed affect the levels of support. Compared with the previous studies about public support for maximum income, where only the threshold level for income caps was stated (see ‘Literature review’), our study utilises vignettes describing the policy background, motivation and potential effects of a maximum income. The use of vignettes detailing the proposal is motivated by the fact that maximum income is a relatively novel idea for which there is no prevailing public discussion in Belgium (or internationally). On the basis of the framework for designing maximum income policy (François et al., Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023), previous studies on the topic and consultations with university experts on the post-growth economy, inequality and eco-social policies,Footnote 2 we designed a baseline vignette detailing a maximum income proposal and five additional vignettes with different design features to be compared with it (Fig. 1). The overall framing of the maximum income proposal is intended to present its potential contribution to the policy goals of alleviating inequality, the provision of essential public goods and services and the socio-ecological transitions to a post-growth society (Dukelow and Murphy, Reference Dukelow and Murphy2022). The five additional vignettes aim to present different previously identified design features (François et al., Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023) that might influence the interviewees’ support for the proposal, by means of varying the threshold levels (Vignette [V] 1 and V2), the types of incomes to be targeted (V3), the destination of the fiscal resources (V4) and lastly the regulatory level at which the maximum income would be implemented (V5).

Figure 1. Vignettes for a maximum income proposal.

To gather a diversity of opinions about the topic, we aimed at maximum variation in interview participants’ backgrounds, thus employing a purposive heterogeneous sampling method (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill2019). Building on existing knowledge about the explanatory factors in understanding public support for eco-social policies (Emilsson, Reference Emilsson2022; Gugushvili and Otto, Reference Gugushvili and Otto2021; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Emilsson, Fritz, Koch, Johansson and Hildingsson2023), we sought to achieve heterogeneity in our sample in the following aspects: age, sex, district of residence, income, education, occupation, political ideology and sense of social justice. The sampling process was aided by a professional company (Dedicated Research) and consisted of two steps. Firstly, from their online panel pool consisting of 185,000 people, a sample of 371 potential interviewees who were willing to participate in a study about ‘inequality’ was created. During this step, people answered a short questionnaire about the eight selection criteria mentioned above. Secondly, these answers were used to build the final sample. Combining a quota sampling method for age, sex and district of residence with a manual screening process for the other criteria, the final fifty interview participants were identified (see Supplementary Table 1 for further details). While not aiming for representativeness, this sampling strategy ensured that the interview participants had diverse sociodemographic and ideological backgrounds.

The data collection took place in the French-speaking part of BelgiumFootnote 3 between May and June 2023. Interview participants could choose where the interviews should take place (online, at their home or at the University of Liège). The majority (forty-eight) were conducted online and lasted about thirty minutes on average. The interviews were structured in two steps: Firstly, the interviewees were introduced to the baseline proposal and given about five minutes to read it. After the reading, respondents answered the question ‘What do you think about this proposal?’ by choosing from a Likert scale of five items, ranging from ‘Very Bad’ to ‘Very Good’. Then, a discussion was launched in which the interviewees were asked to explain the reasons behind their preference. During the second stage, interviewees were presented with variations of the maximum income policy one after the other, only when this was possible and relevant for them. The selection and number of vignettes shown were indeed determined on the basis of their initial responses to the baseline vignette (see Supplementary Table 2 for the list of interviewees and specific vignettes shown to each participant). For instance, with an interviewee who strongly opposed the idea of maximum income, the introduction of other vignettes was delayed until a moment when considering the modified versions of the proposal seemed logical and appropriate. For each variation introduced, interviewees were asked whether they preferred the new version of the proposal or the original version and were asked to share their reasoning. This second stage was inspired by Harrits and Møller (Reference Harrits and Møller2021), who use variations in vignettes within qualitative semi-structured interviews.

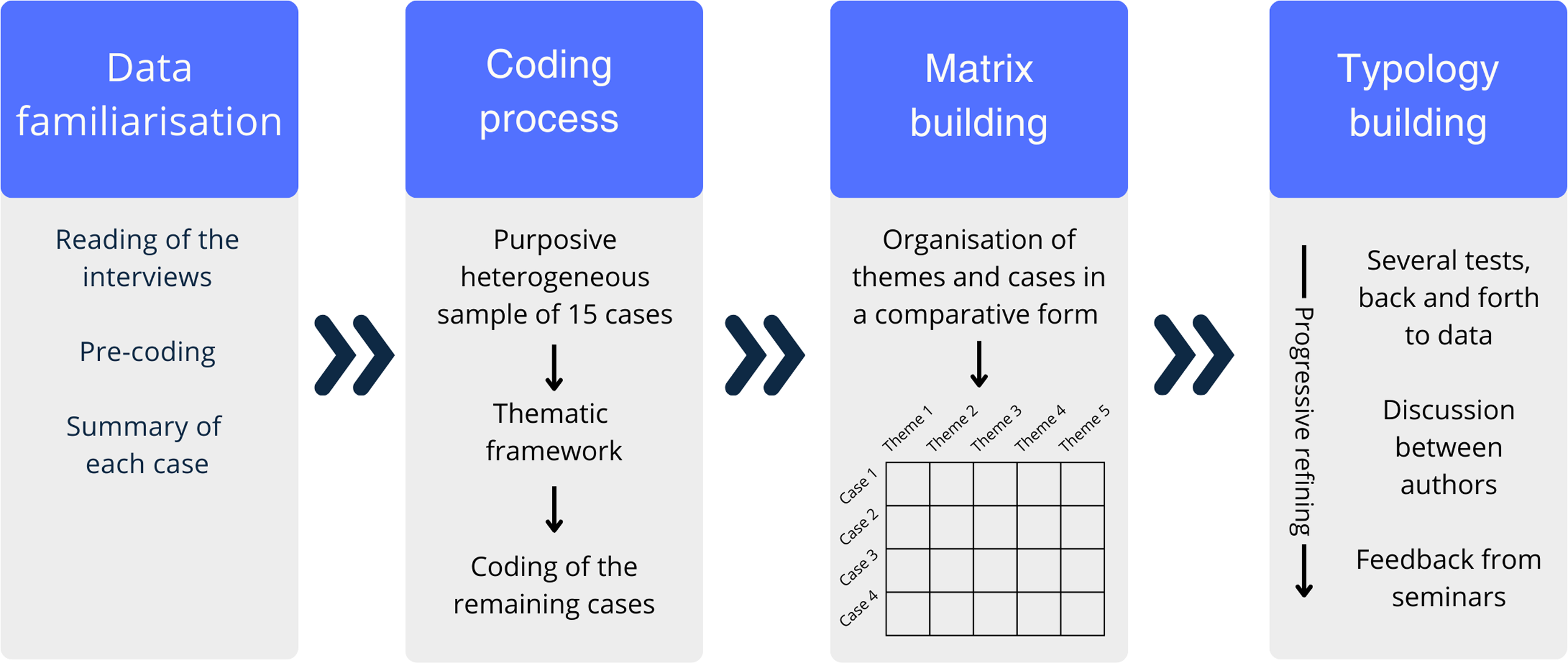

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The data were then coded into a software program (NVivo), using the method of framework analysis. This analytical strategy was chosen because it is particularly appropriate for analysing qualitative data in policy research (Ritchie and Spencer, Reference Ritchie, Spencer, Bryman and Burgess1994). Framework analysis is a variant of thematic analysis, which uses a comparative form to organise cases and themes (i.e. a framework matrix), with the aim of identifying patterns across these cases and themes. As argued by Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith2021), this strategy is relevant when seeking to identify typologies, an approach that is commonly used in qualitative research (Stapley et al., Reference Stapley, O’Keeffe and Midgley2022). The analysis leading to the typologies included four steps (Fig. 2). Familiarisation with the data enabled the researcher to construct a purposive, heterogeneous sample of fifteen interviews, selected to ensure a diversity of rationales relating to the concept of maximum income. An inductive thematic coding of these interviews was conducted to initially identify a thematic framework. This framework was then applied to the remaining data, resulting in a framework matrix. Then, the interpretative phase aimed to identify different typologies among the cases (individual respondents). A cross-cases comparison was carried out, and the cases displaying similar themes and logics of thinking were clustered. This step followed a progressive refining process that included constant back and forth with the original data to ensure that people’s voices were interpreted accurately, discussion between authors and feedback from four research seminars.

Figure 2. The four steps of analysis.

Before the main findings are presented in the following section, it should be noted that the concept of maximum income with a 100 per cent tax bracket proved difficult for seven participants (14 per cent of all interviewees) to understand. Further details were requested by three respondents at the beginning of the interviews, while an incorrect understanding of the notion of maximum income was detected in four interviews. For instance, a 100 per cent tax bracket was understood to mean that rich people or large companies would not be able to practise fiscal avoidance because they have to pay 100 per cent of the taxes that they should have paid: ‘Because when they say 100%, as I understand it, that means that there is no possibility of tax optimisation’ (respondent fifty), but ‘it doesn’t mean that they have to give back what they earn above €1 million’ (respondent thirty-four). In these few cases, further explanations were provided to ensure that the interviewees understood the core logic of maximum income policy. This echoes the hypothesis that a relatively high rate of ‘neutral’ or ‘don’t know’ answers in previous surveys about public support for maximum income may be related to respondents finding it difficult to evaluate the proposal due to its novelty (‘Literature review’ section).

Results

The results are presented in three categories: (1) the ideological divergence among interviewees; (2) concerns regarding implementation, shared by both supporters and opponents; and (3) the impact of the design on participants’ reasoning. In a nutshell, the maximum income proposal as presented in the baseline vignette led to clearly diverging initial reactions among the participants. While those who showed a positive reaction to the idea considered the proposal ‘a good idea’ (respondents five, sixteen, thirty-one, thirty-six and forty-nine), ‘logical’ (respondents four, twenty-four and forty-two) or ‘utopian’ (respondents four, fourteen, sixteen and forty-nine), those who were negative towards the proposal considered it an ‘impossible’ and ‘illogical’ idea (respondents eight, fifteen and twenty-one), or believed that this measure would be ‘extreme’, ‘bad’, ‘radical’, ‘harsh’, ‘violent’ or even ‘abusive’ (respondents seven, ten, thirteen, seventeen, eighteen, twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-five, twenty-six, thirty, thirty-nine, forty, forty-one and forty-six). In terms of proportions, nearly 60 percent of our sample supported the proposal (respondent twenty-nine), one-third opposed it (respondent sixteen) and the remainder fell somewhere in between (respondent five).

Ideological divergence

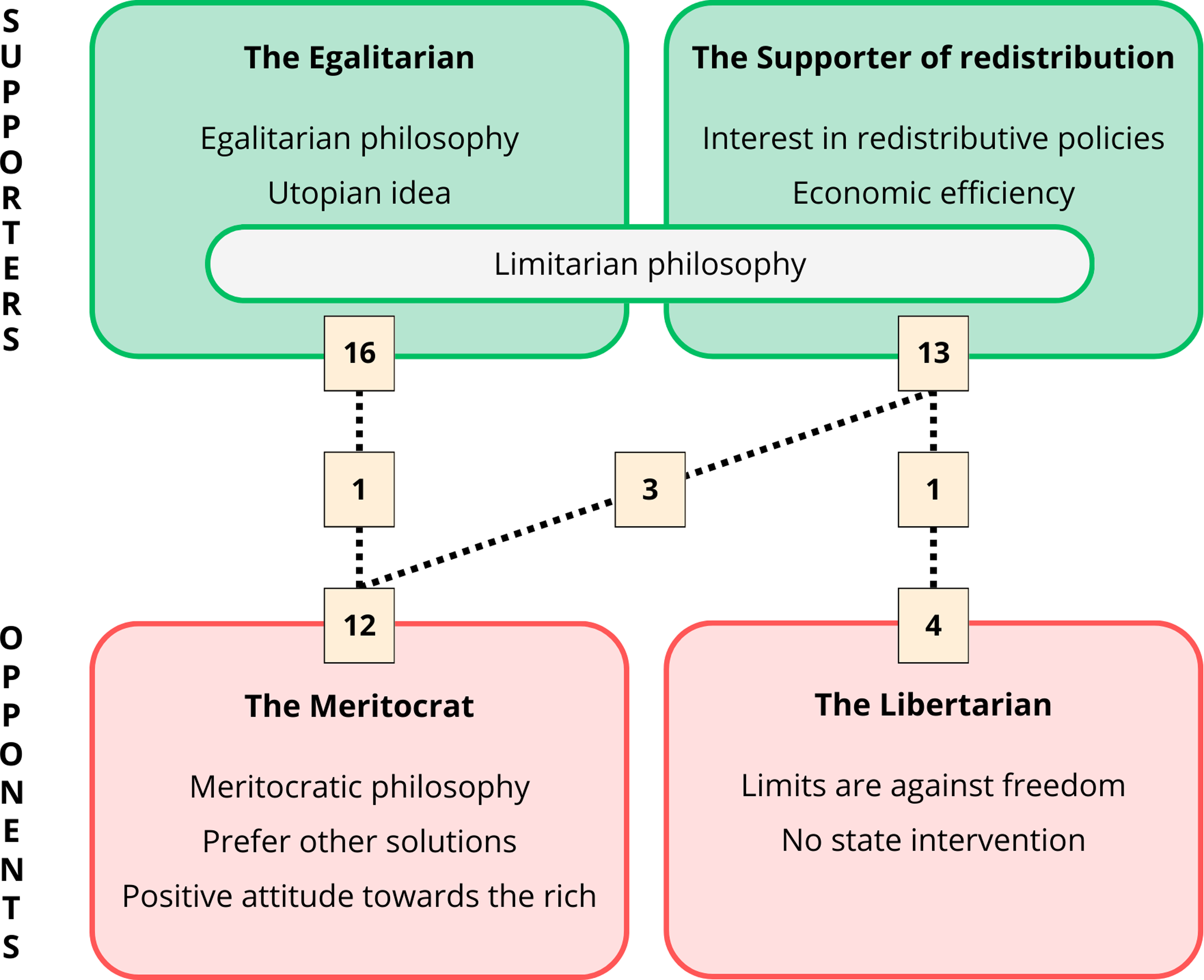

The analysis of the reasoning applied when disclosing their opinions led to four ideal-typical positions. These positions illustrate ideological divergence among two categories of supporters of maximum income (‘the egalitarian’ and ‘the supporter of redistribution’) and two categories of opponents (‘the meritocrat’ and ‘the libertarian’). Figure 3 summarises these four prominent positions in terms of their key rationales and charts the distribution of the interviewees among them. The identification of the key rationale for each category was straightforward for most interviewees, while five of them share the rationales of two categories (these are placed in the middle of the figure).Footnote 4 In the following, we describe each position, illustrated by interview quotes.

Figure 3. Four prominent positions describing different logics of thinking among interviewees.

Note: The numbers in the squares refer to the number of interviewees who share the logic of thinking in each category. Five of them are located at the intersection of two categories (in the middle of the figure).

The egalitarian – ‘This is my dream’5

The egalitarians share an egalitarian philosophy. They are preoccupied by inequalities and the need to reduce them. They are interested in the idea of a maximum income because it can help to create a better, more egalitarian world:

This is a good idea because we all dream of a more equal society. (respondent fifteen)

The proposal is in line with my philosophy of life, with how I think society could be. (…) [A society] with more empathy, more solidarity, less focus on money, while valuing work without making it an absolute value. I’m totally against absolute inequality. (18)

Among respondents holding this position, the idea of a maximum income is utopian, but worth striving for. Although some of the respondents showed interest in the redistributive measures, it is the egalitarian justification as a key claim that distinguishes people belonging to this category. Furthermore, many respondents in this group also expressed a limitarian philosophy, according to which extreme wealth should be used to meet the urgent needs that are currently unmet in society (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2024). The following statement illustrates this philosophical affinity and signals the belief that there is an objective level of material conditions above which more money does not necessarily bring greater wellbeing or more utility to individuals – and thus it is better to channel the excess amount of money towards other societal purposes.

[The idea of a maximum income] is interesting because I think it’s quite pointless for some people to accumulate assets while others don’t even have any. It creates poor people, even more poverty, and rich people who have even more money… at the end of the day, having €500,000 or €1 million for a rich person doesn’t change their way of life. So why not have just €500,000 and then use the rest to help others who can’t even afford the basics of living? (2)

This category also includes a sub-group of people who were mainly interested in reducing wage inequalities between workers and top managers because ‘there’s a huge pay gap in Belgium’ (respondent forty-seven). More than others in this category, they were concerned with feasibility because they counted on the rich entrepreneurs to create economic activity and jobs ( ‘Shared concerns about implementation’ section). This perception of the rich is not surprising because research shows that the media focuses on entrepreneurship and innovation when portraying wealthy business owners (Waitkus and Wallaschek, Reference Waitkus and Wallaschek2022). This sub-group would rather support a maximum wage than a maximum income.

The supporter of redistribution – ‘Tax the rich’

In this category, which was almost as large as the egalitarians in the number of respondents, people supported the maximum income proposal because they supported taxes on the rich to finance redistributive measures. They were not particularly interested in the idea of a maximum income per se but rather supported it because the redistributive measures included in the proposal could benefit the poor or society at large:

The idea isn’t a bad one, since we’re trying to take a bit from those who earn a lot to redistribute within the economy and [give] to others who don’t have enough. (31)

Yes, I agree because the points are valid, i.e. to help people, the poor, give them food, housing, all that sort of thing. Yes, of course, if people don’t leave Belgium and they agree with the 100% tax, we’ll go for it. (28)

However, this supportive attitude towards the proposal and its redistributive measures did not always go hand in hand with support for the idea of a maximum income:

I don’t think [maximum income] is a good idea. On the other hand, trying to redistribute is a good idea. But putting a limit on income is not. (31)

The following quote illustrates that the idea of a 100 per cent tax rate above the cap level was considered unrealistic, and hence not a good idea, although the proposal was broadly supported:

It must be a tax rate so that people say: OK, I’ll pay it because it’s well thought out. It’s true that anything over €1 million is too much. But if you tax at 100%, they’ll automatically find ways of avoiding the tax. (23)

Under this logic, people were considering economic efficiency when they sought a good balance between taxing the rich and avoiding their escape to other countries. They were preoccupied with acceptance of the measure among the rich and would prefer to reduce the tax rate if it would mean more efficiency in generating extra revenue.

Similarly to the egalitarians, many respondents shared thoughts linked to a limitarian philosophy:

I don’t see what point there is in the rich having so much money, so it might as well be taxed. And that money will be used for really useful things. Yes, because beyond a million, I think it’s a bit excessive. (9)

The meritocrat – ‘The rich deserve their income’

The meritocrats comprise the main category of opponents of the maximum income proposal (eleven respondents). According to them, high incomes are the result of hard work, and are therefore deserved. They did not see any reason to limit income, and they saw the idea of an income cap as a negative incentive for society because it stifles hard work, innovation and entrepreneurship:

I’m absolutely against limiting income in general, especially earned income, because that’s what meritocracy is all about. It’s unfair because the person who earns a lot of money has probably had a job other than sweeping the street all their life. (13)

I think it’s more of a psychological barrier than a practical one, because it’s clear that when you reach the age of looking for a job or starting your own business, it’s clear that the fact of being limited is a bad psychological signal. (17)

Much as in previous studies exploring perceptions of the rich, the belief that higher incomes reflect the added value created by competent and hard-working individuals (Hecht, Reference Hecht2022) underpins this objection to imposing a limit on incomes. In this category, people often shared positive attitudes towards the rich, whom they argued contribute a lot to society with taxes and donations, but also by creating economic activity that benefits the rest of the population:

The rich earn a lot of money but they also contribute a lot to the state budget. For example, the owner of a factory will employ a huge number of people and will therefore contribute by paying income taxes and social contributions. Someone who is a billionaire and owns companies in the country will contribute much more than thousands of people with middle incomes. As far as I’m concerned, they’re already making a huge contribution. (40)

These interviewees often mentioned other problems in the tax system that are more crucial than a maximum income: fiscal optimisation, fiscal avoidance, corrupt politicians or high taxes on low incomes. Despite this opposition, some of the respondents agreed with the idea of taxing the rich and said that they would support the proposal if the tax rate were reduced to between 60 and 80 per cent:

Taxes on large fortunes, fine, but why limit them to one million a year, for example? Why don’t you increase the tax when you reach a certain income level? For example, an additional 10% tax each time you reach an extra €100,000 per month. And stop at a threshold of 60–70%. (30)

The libertarian – ‘Limits are against freedom’

Respondents in this category shared a libertarian philosophy. State intervention and imposing an explicit limit in general were considered a serious breach of individuals’ freedom, and hence negative in principle. They argued that the idea of a maximum income could even lead to the collapse of the system because human beings are driven by the desire for wealth:

It’s not up to the public sector to regulate. There are already enough rules and laws preventing us from doing what we want, forcing us to walk between the lines. If now, at the end of this line, which some may walk faster than others, there’s a wall, no, I don’t think it will work. That’s the end of the system. (21)

The world has always been driven by the desire for wealth. If you limit, the world collapses (…) Let me put it this way: limits are never good. Limits suppress human desire. (39)

This opposition echoes research by Jobin (Reference Jobin2018), who argues that far-right libertarianism is the only political philosophy that seems incompatible with the idea of limiting income and wealth. Within this branch of libertarianism, there is no limit to private property, and individuals can take all the resources they are able to obtain without considering the needs of others. According to this author, this is not the case for the other branches of libertarianism. For instance, he argues that right-wing libertarianism includes a ‘Lockean clause’, meaning that the private appropriation of resources must also ensure that there are enough resources left for others to lead a decent life.

Shared concerns about implementation

Despite the ideological divide between the proponents and opponents of the maximum income proposal, concerns about implementation were shared by both sides. The feasibility of a maximum income policy was considered low, and its impact on the economy would be negative according to many respondents. Approximately two-thirds of the participants mentioned at least one of these two concerns, while one-third mentioned neither. Interestingly, however, these concerns prompted some interviewees to come up with modifications to the proposal.

‘Let’s not kid ourselves’ – on feasibility

Many interview participants thought that a maximum income is unfeasible and unrealistic because the rich will never accept it. and they will always find ways to avoid such regulatory measures. It was also difficult to imagine how such a system could work:

People are hung up on their money and people who earn more than 80,000 euros a month are not going to agree to let it go. (4)

Today, imposing a tax like that would be completely crazy. All the ultra-rich would just move their headquarters to Luxembourg or take up residence in another country like Ireland… Maybe it’ll happen one day, but I can’t imagine it happening in Belgium. Given today’s society, it seems impossible to imagine. (40)

This last quote illustrates a ‘cognitive lock-in’ (Louah et al., Reference Louah, Visser, Blaimont and de Cannière2017) that was at play among the respondents’ reasoning. Deep-rooted ideas about how the world works and ideational path dependencies make it difficult to imagine a society with a maximum income.

The following quote illustrates that support for the proposal was conditional upon how promising its political feasibility is:

If at least 95% of these rich people say they are prepared to make this sacrifice, I would put ‘very good idea’ [rather than ‘good idea’] in that case. (31)

Such feasibility concerns have also been identified as affecting the preference for progressive wealth taxation in negative ways in previous research (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, McGrath and Hunt2023). Also on the basis of the feasibility concern, several respondents (six) mentioned that the maximum income policy would be more realistic if it were to be implemented at the European or international level rather than at the national level.

Negative prospects for ‘the economy’

Another highly salient theme common to both the proponents and opponents of maximum income concerned the negative impacts on the economy as a result of capping incomes. Interviewees expected that capital and the rich would flee the country, and that this would lead to a range of negative economic impacts on investments (respondents three, five, fifteen and twenty-four), jobs (respondents fifteen, sixteen, twenty-two and thirty-one), economic attractivity (respondents five, eleven, thirteen, fifteen, seventeen, thirty and forty-five), innovation and entrepreneurship (respondents fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, thirty-seven, forty-six and fifty) and philanthropy (respondent twenty-four). For instance:

Especially in terms of investors, because we all know that investors are very important for the economy. If there’s only a workforce, but no one to create jobs, there’s not much to be gained. (31)

The belief in ‘trickle-down’ economics and the expected negative impact on the economy associated with taxing the rich has previously been identified as a reason for the meagre support for progressive taxation (Emmenegger and Marx, Reference Emmenegger and Marx2019). There was an underlying belief that money is a strong driver for business actors, and that limits will impede the virtuous circle of economic development that creates well-being for everyone and moves society forward:

This can slow down the economic development of companies. In the long term, it can even penalise the country, creating fewer jobs. For example, a craftsman who may have started with two workers and who now manages five hundred people. He may stop at ten workers because it’s completely illogical for him to earn more than that ceiling if he’s going to [have to] give it all back. (15)

Despite existing knowledge about the plurality of motivations among entrepreneurs, including various non-monetary incentives linked to identity or moral values (Murnieks et al., Reference Murnieks, Klotz and Shepherd2020), the belief that higher incomes are the most important incentive for entrepreneurial efforts seems to be strongly rooted. In line with previous research on the deservingness of the rich, where certain sources of wealth are considered more legitimate than others (Sachweh and Eicher, Reference Sachweh and Eicher2023), some interviewees suggested that only the CEO’s income should be capped, not the owner’s. Another suggestion proposed that the sources of incomes to be capped should be selective, also on the basis of the argument that the high-income earners’ role in the economy is indispensable to society:

Salary yes, but income no. (…) So limiting the salaries of the highest earners is one thing, but limiting all their income is another. Because these people create jobs and invest their money to keep our country running. (16)

Moreover, some interviewees suggested that certain professions such as doctors and judges deserve their high incomes more than others, for instance, sportsmen or traders. This type of reasoning suggests that people do not perceive all ‘hard-working’ individuals to deserve high incomes. Instead, people make distinctions and value judgements about the kinds of societal contributions made by the ‘hard-working’ rich population.

Trade-offs in designing varieties of maximum income

In this section, we present insights into the trade-offs in different designs of maximum income policy in terms of how they seem to shape people’s support. These results are based on the later part of the interviews, which focused on introducing additional vignettes of maximum income proposals (‘Methodology’ section) and discussing whether and why the interviewees preferred the new versions compared with the original proposal. On the basis of the findings, we also propose specific needs for further research.

The income threshold levels for the cap turned out to be significant for how people reasoned about both the legitimacy and the feasibility of the maximum income. Firstly, compared with the baseline proposal with the ceiling at €1 million, a lower level of €200,000 per year (V1) was not supported by most interviewees, owing to being too ‘extreme’ (respondents nineteen, twenty-eight and forty-eight), in that it would violate the meritocracy principle by levelling out income differences too much. Specific professions, such as doctors, were mentioned as categories of people who should earn more than €200,000 a year, for instance. Another argument that triggered objections to this lower level of income cap was related to the feasibility concern discussed earlier, that the level would target too many people, or the ‘upper middle-class’ (respondents eight and forty-nine), jeopardising its political acceptability.

With this proposal, more people will complain… no, it’s better to tax those who have a really high income. If we start taxing a little more widely, that’s likely to cause problems. There could be scandals. (49)

This maximum of €200,000 was nevertheless supported by several interviewees because they perceived this amount as already extremely high, and said that it could generate more revenue:

200,000 a year is already a lot! So, yes, I’m in favour of taxing above that amount. Then, it generates €15 billion a year: [think of] all the things we could do with that money! (42)

Hence, an optimal balance between respecting the meritocratic principle and the potential policy effects, as well as feasibility, seems to be found at different levels among the interviewees. For instance, eight respondents spontaneously suggested that around €500,000 as a threshold level would be more appropriate.

Meanwhile, the second vignette, with a much higher ceiling of €5 million (V2), was also strongly rejected:

I think €5 million a year is far too high. It really affects only a very limited number of people in Belgium. And it also brings in less revenue for the state. (…). This proposal doesn’t have enough impact. (47)

However, it is worth noting that some respondents who opposed the baseline vignette did agree with this proposal. For example, one participant (respondent thirty) explained that he supported meritocracy but that €1 million was too low, while he would agree with a very high amount, around ‘3 or 4 million per year’. While it seems as though there is an inverted U-curve that describes the relationship between the level of maximum income and public support, this curve might look different depending on which social groups are consulted (Burak, Reference Burak2013; Robeyns et al., Reference Robeyns, Buskens, van de Rijt, Vergeldt and van der Lippe2021). More rigorous research is therefore needed to identify an optimal level of maximum income in a given context, where the proposal scares away neither its opponents (with too low a level restricting legitimate rewards) nor its supporters (with too high a level affecting too few people).

When it comes to the types of income to be targeted for a maximum income policy, there was a small number of respondents who preferred the third vignette (V3), where only wages would be counted instead of all types of income, as in the original proposal. For them, this alternative was less restrictive and therefore more feasible. Another group of respondents disliked this vignette, making the argument that it is unfair if only wages are included, when we know that the rich make more money from capital investments. Therefore, two opposing rationales seem to exist, one for and one against extending the maximum income to all types of income.

Generally, this question was initially rather difficult for many respondents to reason about, and this might reflect the fact that, for ordinary people, the distinction between different types of income can sometimes be blurred (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, McGrath and Hunt2023, p. 589). Hence, to arrive at conclusive knowledge about how people’s preferences are shaped in regulating the wealthy population, future studies should look more systematically into public support for a maximum income proposal in comparison to a maximum wage (Ramsay, Reference Ramsay2005), as well as wealth taxation.

Many interviewees strongly preferred the original proposal compared with the fourth vignette, in which no specific measures are listed that will be financed by the extra fiscal revenue (V4). This finding echoes research on public support for carbon taxes, where acceptability increases with revenue recycling to citizens (Beiser-McGrath and Bernauer, Reference Beiser-McGrath and Bernauer2019; Maestre-Andrés et al., Reference Maestre-Andrés, Drews, Savin and van den Bergh2021). There were expressions of low levels of trust in politicians, in that, without concrete measures to be financed, one does not know where the money will go, or in that it might finance policies that do not have any public support. For instance:

I’m against this proposal! In my opinion, the problem is not the State, it’s the politicians. We’re human beings. [Without specific measures], the politicians will take their share of the cake. So, I think it’s better to show directly where it’s going to go: funding for health, lower transport fares, and so on. (36)

We also found that the types of public services and reforms that were specified in the original vignette were positively endorsed by most of the participants. Further research could explore more specifically whether including public policies or reforms that could satisfy social groups of different ideological orientations can secure broader support for maximum income proposals.

Lastly, a clear fault line was identified between the respondents who preferred the introduction of a maximum income at the European level and those who discounted it (V5). People with favourable opinions of the EU were likely to endorse the implementation at the European level and argued that it would also alleviate the risk of tax avoidance. In contrast, some of the people with low trust in the EU and the policy process involving all member states preferred regulation at the Belgian level, while others argued that regulation at the European level would not be enough in any case and that maximum income would be unlikely to be effective unless it were implemented at the global level.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This study explores the novel and radical idea of a maximum income policy. This is something that has rarely been discussed in the past but has increasingly emerged in recent years as an eco-social policy with the potential to address the dual crises of accelerating inequality and the climate emergency. The maximum income proposal spurred rather polarised reactions between its proponents and opponents, and our analysis of interviewees’ reasoning illustrates ideological divergence. However, we found that both the proponents and opponents of maximum income shared concerns about barriers to the implementation of such a policy. In part, this is related to concerns about feasibility that resemble the popular discourses around wealth tax evasion. The barriers also include prevailing notions about ‘how the economy works’, where the idea of trickle-down economics underpinned the general acceptance of wealth accumulation and financial incentives for entrepreneurs, which were considered to be the most fundamental and necessary drive, without which society cannot prosper.

Our study also suggests that an appropriate policy design would probably increase public support for a maximum income policy, for instance, by identifying the income cap level that can secure the broadest level of support, or by providing more explanations to respondents to avoid misunderstandings. Another idea would be to slightly decrease the tax rate (to 85 per cent or 90 per cent for instance) because a 100 per cent tax rate was perceived as too extreme. Although a lower tax rate would no longer qualify as a maximum income in a strict sense, it raises the question of what tax rate defines a maximum income. In this regard, a 90 per cent tax rate could perhaps be considered a ‘light’ version of maximum income, which could facilitate its implementation – see, for instance, the case of Franklin Roosevelt presented in François et al. (Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023).

The policy implications of our results are threefold. Firstly, addressing the feasibility concerns will be crucial to consolidate the support of the proponents and to convince the opponents, be it through identifying the optimal level of income ceiling or presenting strategic and plausible implementation plans. This should also entail efforts to ‘break free from existing limitations of collective imagination’ (Dey and Mason, Reference Dey and Mason2018, p. 1) by articulating an alternative framework for understanding how an economy with income limits could operate. To overcome this cognitive lock-in, research on post-growth seems a promising avenue that can contribute to new social imaginaries and to designing post-growth organisations (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Jermier, Peredo, Perey and Reichel2021; Hinton, Reference Hinton2021) that are compatible with the idea of an income limit.

Secondly, this research identifies two major ideological barriers: meritocracy and the absolute right to private property. Overcoming these obstacles requires political actors – such as policymakers, civil society organisations and academics – to develop new arguments and to advance new ideas on these two themes. On the one hand, the belief in a merit-based justification for extremely high incomes needs to be challenged. While implementing income limits may seem to conflict with the principle of meritocracy, research has shown that there are limits to the meritocratic justification for high incomes. Factors such as luck and power also play a significant role in determining the level of income achieved (Granaglia, Reference Granaglia2019), and instruments such as performance pay schemes contribute to the social construction of the merit-based justification of some extremely high incomes today (Hecht, Reference Hecht2022). To support policymakers in this endeavour, further studies could examine whether a framing that includes information about the limits to the meritocratic justification of pay gaps in contemporary society might positively influence the attitudes of opponents of the idea of maximum income.

On the other hand, the idea of an absolute right to private property implies that a 100 per cent tax is perceived as extreme, abusive and even an unethical act by the state, akin to theft. Therefore, it is crucial for political actors to draw upon academic debates that challenge the idea of absolute private property rights to develop new arguments. They could build, for instance, on the work of Fabri (Reference Fabri2023), who advocates limits to private property with the aim of reducing the environmental impacts and inequalities resulting from the absolute rights of the owner. In the case of maximum income, one may question the legitimacy of an individual’s uncircumscribed right to income beyond a certain threshold, considering the important role that ‘social inheritance’ – for instance, collective infrastructures and social and cultural practices upholding production processes – plays in any given individual’s performance (Malleson, Reference Malleson2023) Instead, this income could be argued to belong to the community where it was generated, with the community deciding its distribution on the basis of everybody’s needs – see for instance Marlene Engelhorn, who organised a citizens’ assembly of randomly chosen people to decide how to distribute her inherited €25 million fortune (Guardian, 2024). Another idea of how to go beyond private property is the notion of temporary social ownership in the context of business ownership (Piketty and Goldhammer, Reference Piketty and Goldhammer2020).

Thirdly, our findings indicate that the ethical and philosophical principle that can be defined as ‘limitarianism’ (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2024), a belief that no one should own excessive amounts of resources above a level that allows one to flourish, is quite widespread. The idea of a maximum income, the notion that we might be able to agree on an objective level of a social maximum, seems to provide people with the opportunity to reason about the excess in relation to the sufficiency principle. For policymakers, this suggests that it would be both relevant and strategic to integrate ideas about wealth regulation and income caps with the themes of poverty reduction and inequality. This framing is likely to gain the support of ‘weak limitarians’, people who support limits due to an aversion to inequality, in contrast to ‘strong limitarians’, who support limiting high incomes irrespective of inequality (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Ramoglou, Savva and Vlassopoulos2024).

This study includes several limitations. It was conducted in a single country, Belgium, with strong welfare institutions and a relatively low level of inequality. Generalisation of the results to other countries remains an open question. Furthermore, people may have shared a more positive attitude to the idea of a maximum income due to the desirability bias that usually exists in interviews. Another limitation concerns the construction of the vignettes, which was heavily based on the analytical framework developed by François et al. (Reference François, Mertens de Wilmars and Maréchal2023). Although this framework comprehensively covers historical cases as well as academic works on maximum income, it was designed by analysing a limited set of policy proposals. Alternative approaches, not covered by this framework, could have been considered, such as the idea of introducing exceptions for entrepreneurs or adopting approaches that place less emphasis on the state’s role in regulating income limits. For instance, one could envision self-regulation by companies that choose to cap the incomes of executives and shareholders, something that might enhance acceptability among individuals who are sceptical about state intervention (see, for instance, Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Ramoglou, Savva and Vlassopoulos2024). Moreover, the research findings are constrained by the methodology – the use of semi-structured interviews. While this approach allowed us to capture participants’ initial reactions and justifications, it does not provide insight into the depth of their beliefs. Are the positions that we identified in our interviews based on rather superficial, easily changeable beliefs, or even rationalisations masking true, underlying preferences about the idea? Or are they more deeply ingrained convictions? Employing complementary methods, such as in-depth interviews and focus groups, or experimental survey studies, would be valuable to further explore and triangulate these findings.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study reveals the importance of qualitative research in aiding in the understanding of public support for new policy ideas. By revealing the key ways in which people reason about the idea of a maximum income and identifying new links between policy design and public support, it opens up new avenues for further research and policy discussions, bringing a potentially transformative and innovative policy idea one step closer to implementation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279425000133.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Fonds Terro from the King Baudouin Foundation (Grant Number: 2023- E2190230) and by the research centre Etopia (Grant Reference: ‘Don ETOPIA – CES’). The sponsors had no role during our research, and we are thankful for their support.

Jayeon Lee’s work on this article has been financially supported by Early-Career Researcher Grant from the Swedish research council FORMAS (Project No. 2023-00453).

We are also grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions of the members of the research centre Centre d’Economie Sociale and the participants of the 21st Espanet Conference – 2023 Warsaw.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.