In a speech published in 1905, New York State Senator George Washington Plunkitt described the most important task that a politician should perform for his voters. Calling it the “Solemn Contract,” he stated that a good politician “spends most of his time chasin’ after places in the departments, picks up jobs from railroads and contractors for his followers, and shows himself in all ways a true statesman.”Footnote 1 Plunkitt was a member of Tammany Hall, the infamous New York City Democratic Party political machine that relied on its strong support among poor and working-class voters to dominate the city’s government during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Like almost all other machine politicians, Plunkitt tied his popularity and capacity to win reelection to his ability to provide for the material needs of the city’s working class, whom he described in a separate speech as his most important constituency and electoral base.Footnote 2 Because of these actions, Plunkitt claimed that he enjoyed fervent support from the city’s working class, declaring that “the poor are the most grateful people in the world” and that “the poor look up to George W. Plunkitt as a father, come to him in trouble—and don’t forget him on election day.”Footnote 3

In particular, Plunkitt argued that machine politicians enjoyed the support of New York City’s working class by delivering patronage jobs, or jobs that politicians could give to constituents in the municipal government or private businesses, in return for their vote. In other instances, Plunkitt stated that he provided informal charity to his supporters out of his own pocket, such as by paying for the hotel expenses of constituents who had lost their tenement apartment in a fire. This practice, he said, stood in contrast to other major parties and party factions in the city, which, unlike Tammany Hall, were made up of predominantly middle- or upper-class leaders. Using the catchall term reform to describe these various politicians, Plunkitt argued that they usually lost elections against Tammany Hall because they could not provide an equivalent of the machine’s material aid to entice working-class voters to their platform. In his concise summary, he stated that reform failed because “you can’t keep an organization together without patronage. Men ain’t in politics for nothin’.”Footnote 4

While the accuracy of this narrative is sometimes challenged, historians have generally taken Plunkitt’s assertions at face value, with little attempt to evaluate his and other machine politicians’ claims from the perspective of the typical working-class voter.Footnote 5 In large part, this gap in the historiography exists because this group of voters left behind few written sources and were rarely quoted in city newspapers or other contemporary media, making it difficult to recreate the working-class voice from traditional primary sources. This article offers a three-pronged approach to overcoming that difficulty by examining working-class oral histories, reading against the grain of city records and legislative investigations, and performing quantitative analysis of census data and vote returns. Based on this methodology, the first part of this article evaluates the role of patronage jobs and informal charity in winning over working-class voters to the Tammany ticket. It finds that these programs did represent one of the few pathways for working-class New Yorkers to rise into the middle class – and that they explain much of Tammany Hall’s strong electoral support in working-class neighborhoods of the city. However, this article also complicates the narrative of political machine and working-class relations put forward by politicians like Plunkitt. It demonstrates that, outside of these programs, working-class voters actually expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with Tammany Hall governance, especially with Tammany Hall’s ubiquitous graft and corruption. Despite impressive vote totals in most elections, testimony from official investigations and oral histories reveal that the machine’s working-class support was frequently soft, begrudging, and liable to collapse after particularly egregious Tammany Hall scandals.Footnote 6

The second section of this article shows why working-class voters never permanently abandoned Tammany Hall, by evaluating their relationship with Tammany Hall’s main political opposition, New York City’s middle- and upper-class reform parties. It demonstrates that Plunkitt was correct in that these parties usually failed to compete with Tammany Hall because they could not offer working-class voters an equivalent to machine patronage and charity. If anything, Plunkitt may have been understating just how unpopular politicians from these parties were in working-class neighborhoods and misunderstood the source of that unpopularity. This article shows that, along with their opposition to patronage, reform politicians engaged in a host of other actions and rhetoric that deeply antagonized working-class voters. In other words, an important factor in Tammany Hall’s strong electoral performance between 1870 and 1924 came from what political scientists term “negative partisanship,” or the phenomenon in which voters’ support for one party is motivated more by dislike of an opposition party than by true support for the first party.Footnote 7 Despite their dissatisfaction with many elements of Tammany Hall governance, stronger hostility to reform parties meant that working-class voters generally cast their ballot for Tammany Hall when faced with a choice between a machine and reform candidate.

Terms, Methodology, and Historiography

Briefly defined, a political machine is a type of partisan organization that was common in many American cities during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Although there were some exceptions, machines tended to be centrally organized around a political boss and his district leaders, whose main duty was to ensure the election of the party’s candidates. The party leadership might hold office themselves, but their position in the machine was distinct from their elected position. Party leadership, in turn, relied on a cohort of professional political operatives, called ward heelers, who represented the organization at a neighborhood level and conveyed constituent concerns and needs back to them. Unlike a normative political party, which is unified by ideological and policy concerns, a machine principally mobilizes voters by offering direct material rewards to supporters from electoral victory.Footnote 8

Occasionally, a city had multiple political machines. During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Tammany Hall was the main faction of New York City’s Democratic Party, although other Democratic factions existed and occasionally even challenged Tammany’s leadership of the party, without lasting success. For example, a conservative, pro-reform faction of the Democratic Party called the County Democracy was one of the main opposition groups to Tammany Hall during this period and frequently put forward an alternative Democratic ticket during elections.Footnote 9 New York City was also home to a branch of the New York State Republican political machine of Bosses Roscoe Conkling and Thomas Platt. However, the Republican state machine usually struggled to win elections in heavily Democratic New York City and often fought with its own party’s candidates for municipal office, who tended to be pro-reform.Footnote 10 Party factions could also be fluid. Sometimes, Tammany Hall and the County Democracy would run a single Democratic candidate. In other instances, the city’s other mainstream parties would unite under one Fusion candidate to run against Tammany Hall’s candidate. Although this diversity of parties may appear confusing at first glance, it obscures the fact that New York City’s elections usually came down to a contest between a coalition led by a Tammany Hall Democrat and one or several pro-reform parties who were united by their opposition to the system of machine politics. Following the lead of contemporary observers, this article refers to that broad group of politicians as reform politicians.

While there are multiple ways to define class, this article adopts sociologist Max Weber’s framework that class is a status group defined by one’s position in the market economy, which determines the “life chances,” or opportunities in society, available to members of that group. In this model, a working-class individual’s class status is primarily defined by a lack of saleable property other than their own labor. That is to say, workers who are dependent on wage work for their subsistence and who lack the freedom not to sell their labor for a wage are members of the working class. However, because this definition qualifies that one’s life chances are the determining factors in one’s class status, it also classifies individuals who own small amounts of saleable property to be working class if they have little economic security or control over their working conditions.Footnote 11 Within this article, professions such as pushcart vendors or newsboys who owned their wares, or brothel madams who owned their brothel, are also designated as working-class for this reason. The Weberian category of middle class can be defined as those with some economic security, limited ownership of property, and some control over working conditions, but little ownership of capital. The upper class can be defined as those with significant economic security, enough wealth that they have the freedom not to labor or to fully determine the conditions of their labor, and ownership of capital that can be used to generate passive income.Footnote 12

The Tammany Hall political machine was chosen for this study because it was one of the longest-lasting and largest political machines in the country. Both during this period and today, it has often served as a byword for the quintessential political machine and, over its long history, left behind an extensive documentary record. Tammany Hall politicians were infamous for their corrupt behavior in office, including schemes to accept bribes and kickbacks for the granting of municipal contracts, police extortion of local businesses, graft, and other crimes. This article draws on the numerous investigations of Tammany Hall by the New York State legislature, especially the 1894–1895 Lexow Committee investigation of municipal police misconduct and the 1899–1900 Mazet Committee investigation into the fraudulent awarding of city contracts. Although conducted by opponents of the Democratic machine, these investigations interviewed hundreds of ordinary New York City citizens and are some of the few instances where working-class voters’ voices were directly recorded. The article also draws on rare written accounts by working-class citizens, as well as oral history accounts recorded throughout the 1970s and 1980s from the Ellis Island Oral History Project and from historian Jeff Kisseloff in You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan from the 1890s to World War II (1989).Footnote 13

These individuals’ accounts are complemented by quantitative analysis from digitized census records in New York City for 1880 and 1910, provided by Columbia University’s Mapping Historical New York project.Footnote 14 Among other features, this digital atlas allows the user to see a breakdown of occupations by residents who lived in each census ward in Manhattan and the Bronx for the years 1880 and 1910. Using this tool, the author divided the listed occupations into working-class and middle- and upper-class professions to determine roughly how “working-class” each ward was in 1880 and 1910.Footnote 15 The 1880 designations were used for all elections between 1870 and 1896, and the 1910 designation was used for all elections between 1897 and 1924. In 1898, New York City expanded from containing just the island of Manhattan and the Bronx to its modern five boroughs (incorporating Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island).Footnote 16 For consistency, both datasets only examine wards that made up the city of New York before 1898. From these datasets, the author found that there was an average of 1.76 “working-class” occupations for every 1.0 job in a “middle- or upper-class occupation” in Manhattan and the Bronx – indicating that working-class families made up significantly more than half of New York City’s population throughout these years.

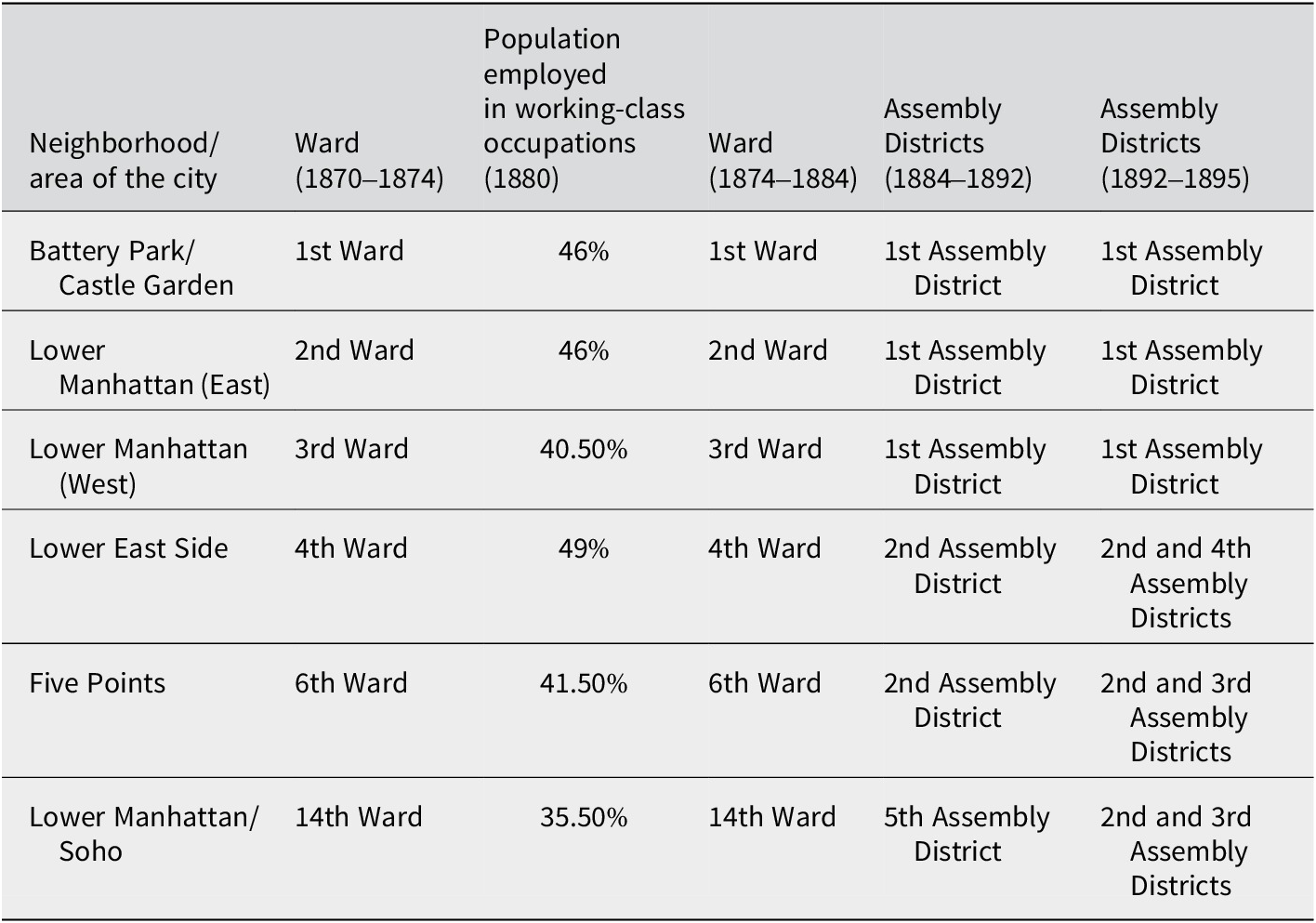

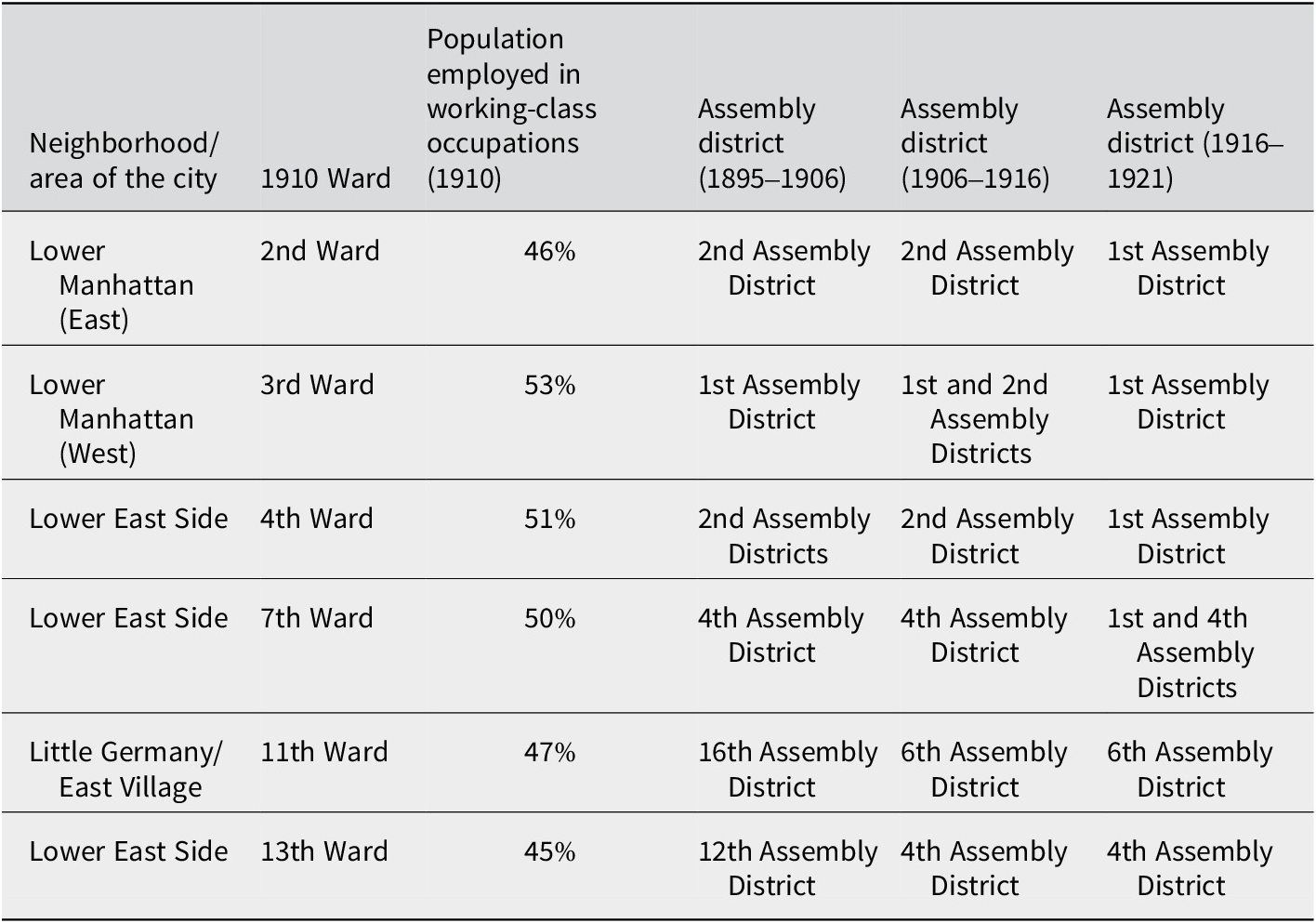

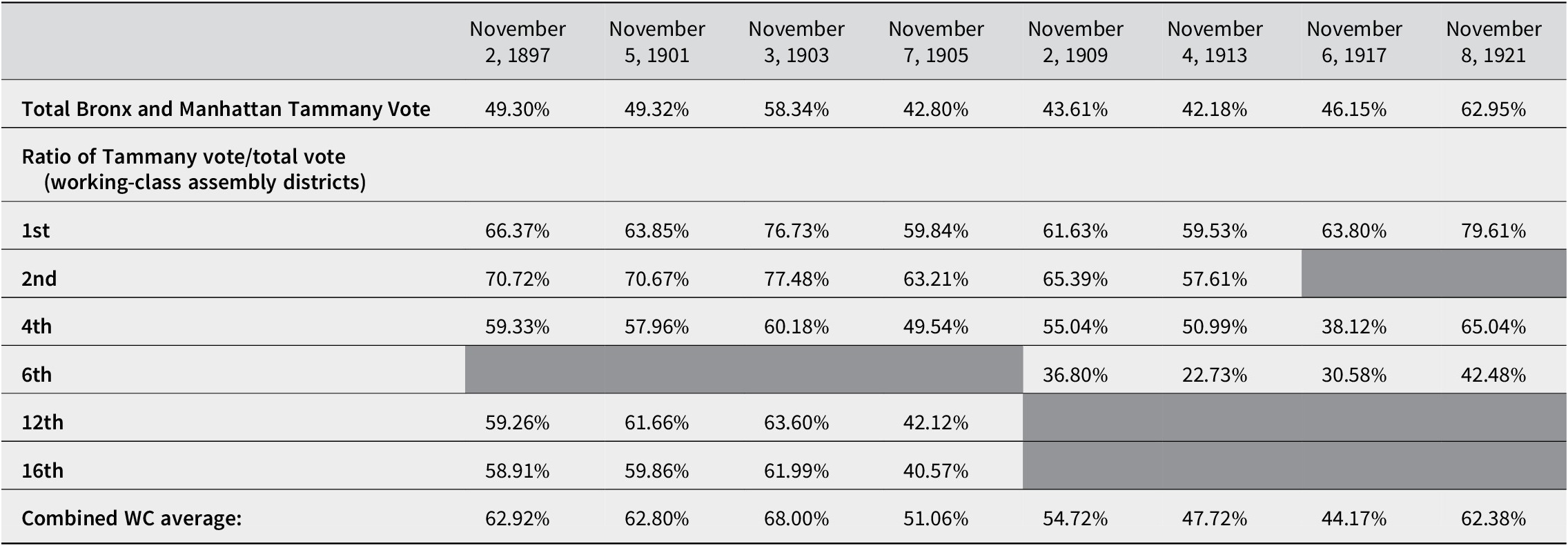

The author then compiled the vote returns for each electoral subunit used in New York City municipal elections for each mayoral race between 1870 and 1924. These returns came from a copy of the New York Times or the New York Tribune that showed each election’s complete vote totals (usually printed two to four days after the election). The structure of New York City’s municipal elections changed several times during the period under study. Between 1870 and 1882, elections were organized around the same wards that were used to divide the city in the federal census. Beginning in 1884, the city changed to holding elections based on state assembly districts, making it much harder to analyze the correlation between demographics and vote totals. However, the six most working-class wards in Manhattan and the Bronx broadly overlap with three to five assembly districts for each of the years that the city performed redistricting, as seen in Table 1 and Table 2. Because of this method, it is still possible to see general trends in working-class voting behavior within the same geographic area for all of the elections discussed.Footnote 17

Table 1. Working-Class Electoral Districts in NYC, 1870–1895

Table 2. Working-Class Electoral Districts in NYC, 1895–1921

Since the 1940s, much of the historiography of Tammany Hall and other political machines has focused on understanding their structural mechanics, especially understanding why and how machine politicians distributed resources to benefit certain constituencies or themselves. In Social Theory and Social Structure: Toward the Codification of Research (1949), Robert Merton argued that political machines existed chiefly because they provided a “latent function” to the urban poor and new immigrants by offering social mobility through informal charity and job patronage. This view, known as functionalism, has since been adopted by the majority of historians.Footnote 18 However, the functionalism model has been challenged by some scholars, such as Terrence McDonald, who argues in “How George Washington Plunkitt Became Plunkitt of Tammany Hall” (1994) that there is little solid evidence for Tammany Hall politicians providing for the material needs of their constituents as part of a systemic program to win elections.Footnote 19

Other historians have called into question aspects of this model while concurring with many of its basic conclusions. Steven Erie, in Rainbow’s End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of Urban Machine Politics, 1840–1985 (1988), argues that political machines were so fiscally constrained during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that the rewards they could distribute to supporters were highly limited and directed mostly toward favored constituencies. In particular, Erie posits that Irish Americans used ethnic bloc voting to gain control of the Tammany machine by the 1870s and thereafter directed resources disproportionately to fellow Irish Americans.Footnote 20 Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer, in Electoral Capitalism: The Party System in New York’s Gilded Age (2020), argues that the conditions of rapid economic growth and strong party control in Gilded Age cities incentivized machine politicians to create corrupt but profitable partnerships with business interests, in return for those businesses receiving favorable treatment by elected officials. In his model, machine politicians tended to look for ways to commodify their office for personal or party enrichment, even when that goal diverged from the needs of their constituents or threatened their electability.Footnote 21

This article engages with this historiography. It builds especially on Erie’s observation that political machines struggled throughout this period to provide material benefits for most of their voters and demonstrates how those struggles influenced working-class perceptions of Tammany Hall. Without contesting Erie’s claim for ethnic favoritism in the distribution of patronage and charity, it also shows that working-class New Yorkers across ethnicities (including many Irish Americans) were generally dissatisfied with the machine’s inability to overcome these constraints. In doing so, it adds nuances to the functionalism model by arguing that, while material aid programs existed and tended to be viewed positively by working-class voters when they performed well, other factors also had major influences on working-class voting behavior.

This article deliberately limits its scope to understanding working-class views of the Tammany Hall political machine and the machine’s mainstream reform opponents. Such a narrow focus is not meant to downplay the importance of populist, pro-labor, or socialist candidates. Indeed, these third parties often won a large proportion of the city vote in mayoral elections and, unlike the reform candidates discussed in the article, offered an alternative policy vision directed at working-class New Yorkers. However, the fact remains that no third-party candidate managed to win any of the New York City mayoral elections between 1870 and 1924. In recent years, historians have paid increasing attention to these parties and the factors that may have contributed to their inability to win electorally in New York City. Edward T. O’Donnell’s Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality: Progress and Poverty in the Gilded Age (2015) shows that grassroots third parties faced numerous structural barriers to competing against mainstream parties, such as having to pay for and print their ballots and find and pay for election inspectors at polling places to guard against ballot fraud.Footnote 22 Mark A. Lause, in Counterfeiting Labor’s Voice: William A. A. Carsey and the Shaping of American Reform Politics (2024), demonstrates that Tammany Hall also used a host of dirty tricks to quash new populist and labor parties early in their development. For example, Lause records many instances of Tammany politicians creating fake populists or labor parties with names similar to an authentic party in order to split the latter’s vote on election day.Footnote 23 This article builds on the work of O’Donnell, Lause, and other historians of New York City’s grassroots third parties by analyzing why Tammany Hall bosses went to such great length to quash candidates from these movements, and why they did not take these steps to nearly the same extent against mainstream Republican and reform Democratic candidates.

The Machine, Patronage, and the Working Class

In the speeches of George Washington Plunkitt, quoted above, he made three basic claims about Tammany Hall’s relationship with its working-class base:

-

1) Tammany Hall’s strongest support came from working-class areas of the city.

-

2) The most important factor in a machine politician’s ability to win an election was his capacity to provide plentiful job patronage and other forms of material aid to working-class supporters who needed assistance.

-

3) The city’s various middle- and upper-class reform parties failed to appeal to working-class voters because they did not offer an equivalent policy to Tammany Hall’s patronage practice or informal charity.

Although Plunkitt was just one member of the Tammany Hall political machine, the same basic claims were repeated by other Tammany Hall politicians in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. For example, Owen McGivern (1912–1998) was a Tammany Hall-backed judge who grew up poor in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. When asked in an oral history interview about Tammany Hall’s reputation in his childhood neighborhood, he also claimed that the machine enjoyed ardent working-class support and linked this support to the machine’s charitable and job-finding practices:

Then, everyone gravitated to the [Tammany political] club … Every block had a district captain, who was a big figure. Tammany Hall took the place of social security, old-age pensions, and home relief. You had none of those institutions. Those Tammany clubhouses did their best to take care of the destitute. Sometimes they were all that held those neighborhoods together. They helped a lot of people who were about to be thrown out on the sidewalk. They hired people to shovel snow. During every snowstorm, there’d be thousands of these guys out on the street day and night.Footnote 24

Even the highest-ranking Tammany party leaders were surprisingly open that job patronage was the most important selling point that the machine could offer to its supporters. Boss Richard Croker, in an 1894 interview with the London Review of Reviews, stated about Tammany’s voting base: “‘And so, we need to bribe them with spoils. Call it so if you like. Spoils vary in different countries. Here they take the shape of offices. But you must have an incentive to interest men … when you have our crowd, you have got to do it in one way, the only way that appeals to them.’”Footnote 25

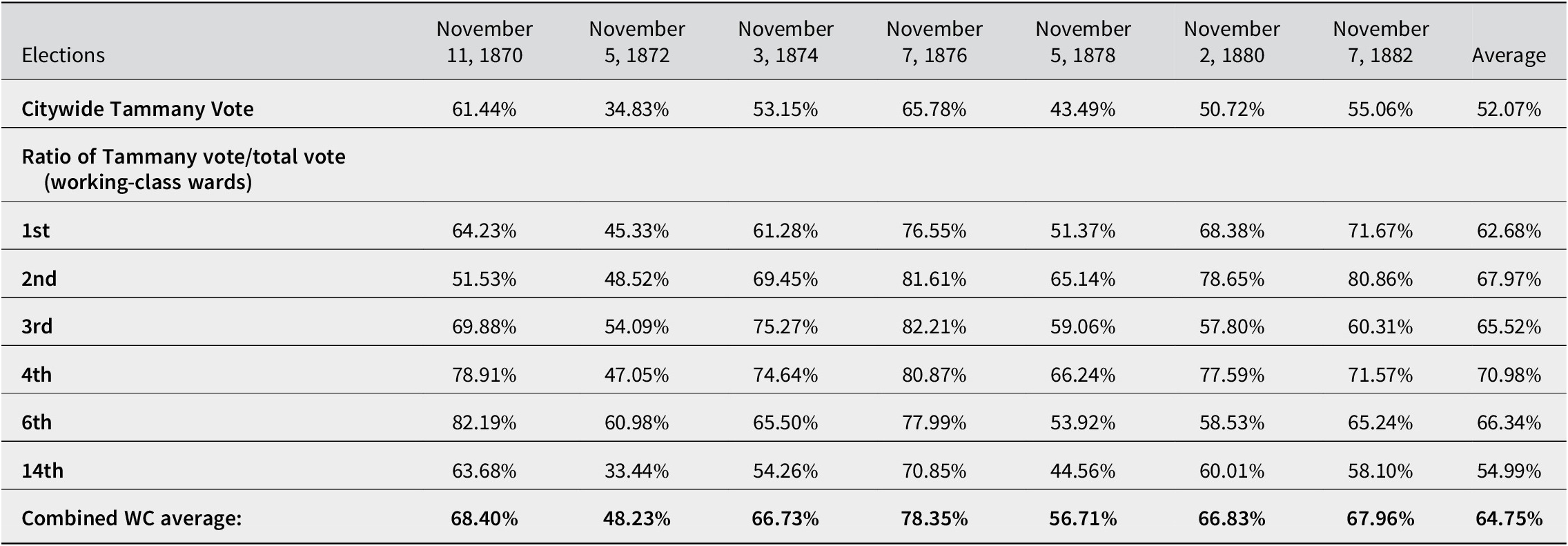

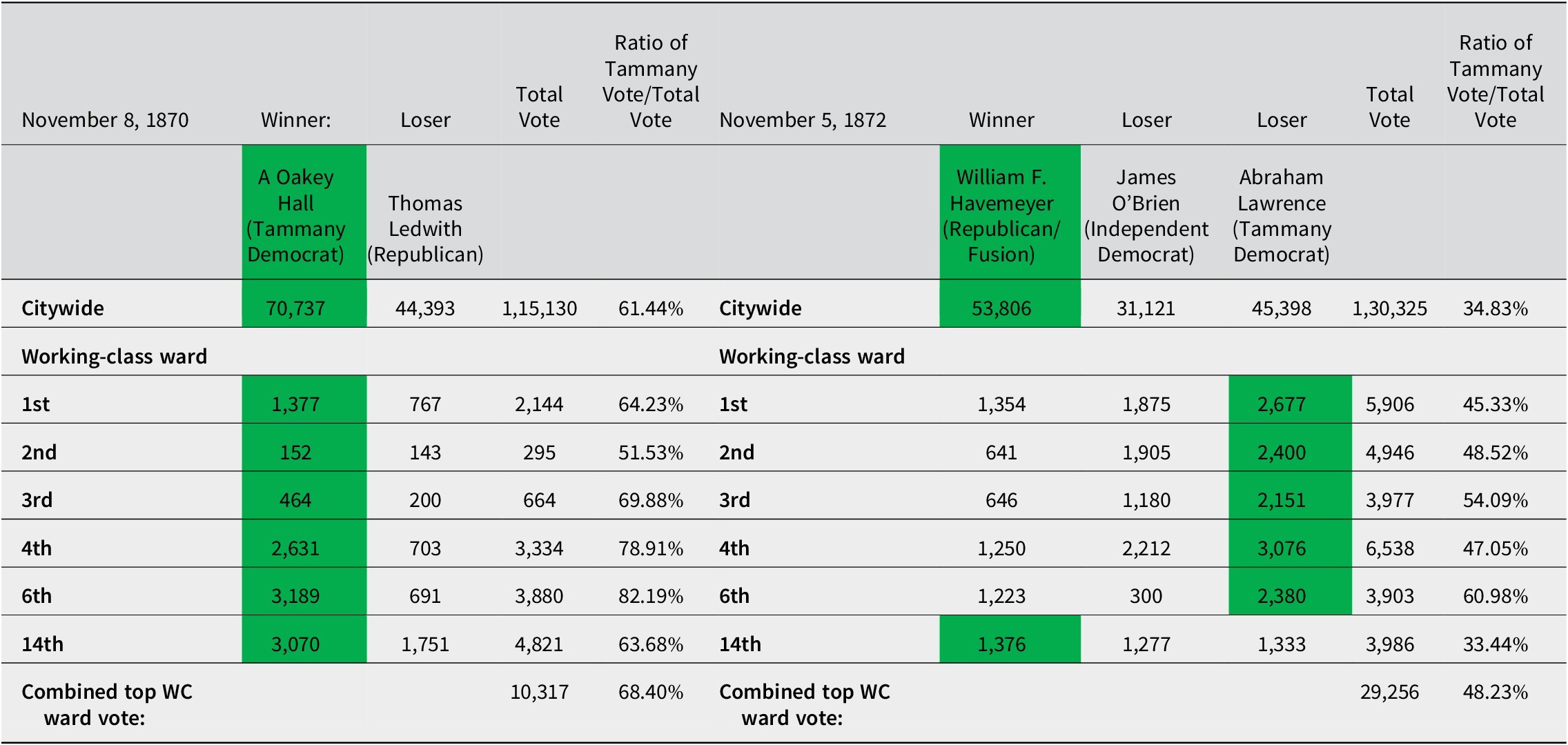

This consistency in how Tammany politicians described their organization and welfare function goes a long way in explaining why previous historians have largely taken these claims at face value. However, when one begins reading with an eye toward working-class sources, evidence emerges that this narrative was only partially accurate. To begin with the first claim, Plunkitt was correct when he stated that Tammany Hall’s strongest support came from working-class areas of the city. For the period 1870–1882 (for which census wards overlap with election wards), there is a very high 0.68 correlation between an electoral ward’s vote total in mayoral elections and the percentage of ward residents who were engaged in working-class occupations. In the six most working-class wards of the city, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 14th, Tammany Hall mayoral candidates averaged 64.75 percent of the vote across this set of elections, far outperforming their citywide average of 52.07 percent. (See Table 3).

Table 3. 1870–1882 Vote Analysis

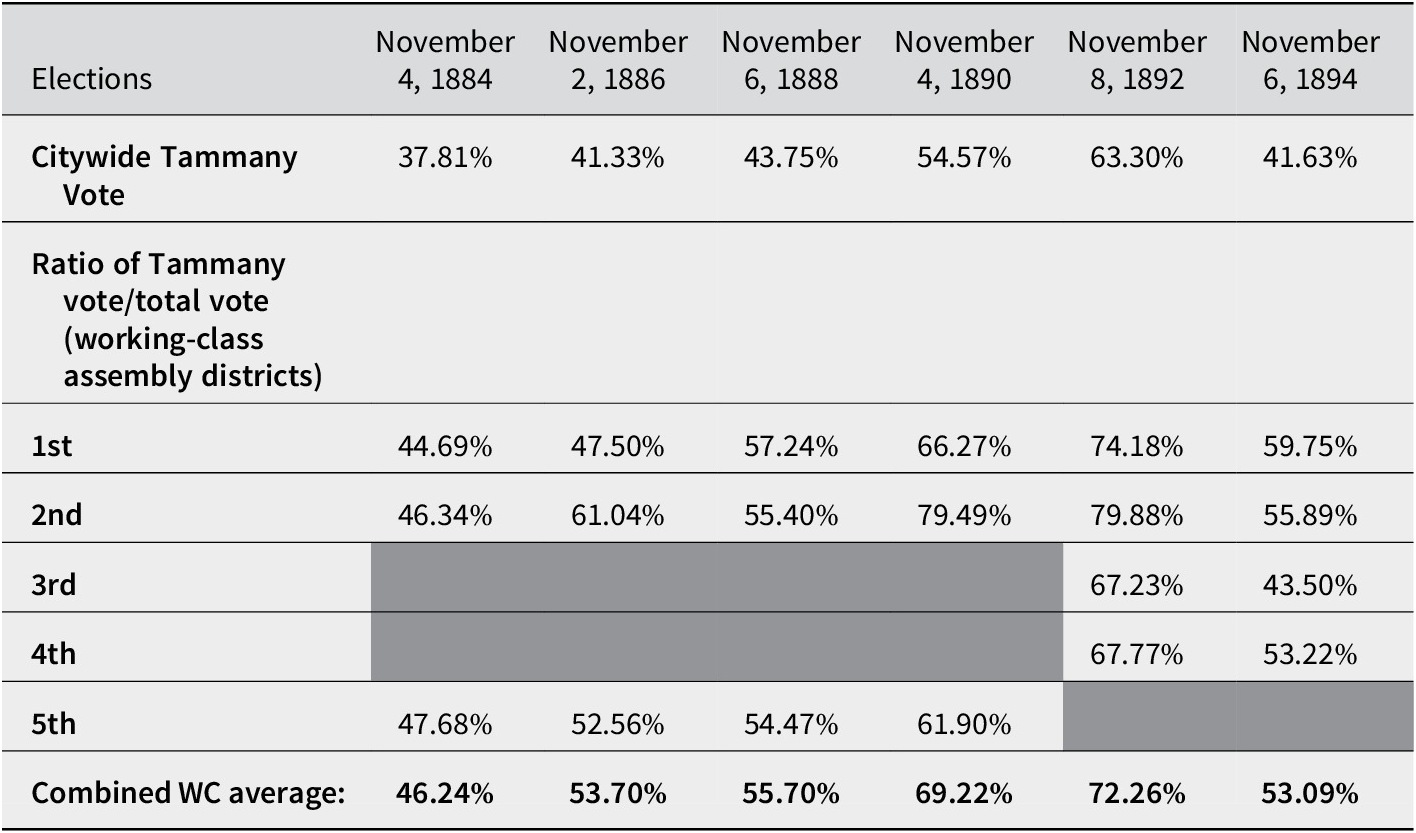

Because New York City switched to holding elections based on state assembly districts rather than census wards in 1884, it is not possible to conduct a correlation test for the period 1884–1896 or 1897–1921. However, the election districts that broadly overlap with census wards containing the highest number of working-class residents continue to show that Tammany Hall outperformed its citywide vote totals there. For the period 1884–1896, Tammany Hall mayoral candidates won a combined average of 58.37 percent of the vote in the city’s top working-class assembly districts, compared to a citywide average of 47.06 percent, while in 1897–1921, after New York City expanded to incorporate its modern five boroughs, they won a combined average of 56.72 percent of the vote in top working-class assembly districts compared to an average of 49.33 percent in the rest of Manhattan and the Bronx (See Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. 1884–1896 Vote Analysis

Table 5. 1897–1921 Vote Analysis

Job patronage and, to a lesser extent, informal machine charity, were such a popular selling point from Tammany Hall leaders because they promised to address one of the most important day-to-day concerns of working-class New Yorkers. Josephine Shaw Lowell, leader of the Charity Organization Society, summarized the concerns of “the various poor people” she worked with as: “They all want work work work … they do need money enough for their labor to enable them to lay by for the sick time or for old age.”Footnote 26 Other working-class individuals described the intense pressure from their families to find any job available. Bill Bailey (b. 1910), a longshoreman who grew up in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, remembered: “With us kids, if there was a way of makin’ a nickel or a buck without anybody gettin’ hurt, you’d do it. You were nobody unless you had a nickel or a dime … As soon as you got into the house, ‘Did you get a job today? How come you didn’t get a job? The kid down the street got a job.’”Footnote 27 Another witness, Lower East Side boxer Owen Kildare (b. 1864), argued that the need for employment was the all-encompassing concern of poor New York families like the one in which he grew up, stating: “Life in the tenements is a particularly busy one of its kind. When all efforts are directed toward the one end of providing the wherewithal for food and rent, each meal and each rent-day is an epoch-making event.”Footnote 28

Examining the second claim, it becomes clear that the material aid a machine politician provided could be a godsend to one of the poor or working-class voters who received it. Such aid explains much of Tammany’s ability to win elections. In numerous instances in these investigations or oral histories, previously working-class supporters of Tammany Hall were able to use a patronage job in the city government to rise into the middle class and achieve economic stability in a way that was difficult to do through other means. George T. Sheridan (1868–1940) was a patrolman with the New York City police. When interviewed by the Lexow Committee in 1894, he testified that before joining the force due to the endorsement of his local Tammany district leader, he had been employed as a bricklayer, a profession where he might have been expected to earn around $100 per month, assuming optimal conditions of six days of work per week. However, these optimal conditions were rare in Gilded Age New York. Like other semi-skilled positions, the availability of work was highly dependent on seasonal demand and volatile economic conditions, which severely reduced a worker’s yearly take-home pay. Because of these circumstances, the New York Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the average annual pay for a wage worker in New York State was actually $439.97 in 1894.Footnote 29 By contrast, even a low-ranking patrolman like Sheridan was guaranteed to earn a starting pay of $1,200 a year and, upon retirement, a comfortable annual pension of $600.Footnote 30 Most other policemen interviewed by the Lexow Committee who gave their profession had come from similarly working-class backgrounds, such as a tugboat fireman, a livery stableman, or a janitor.Footnote 31

This fact also held true for other patronage appointments in the city government, where even the lowest position tended to earn a wage above its equivalent in the private sector. For example, an 1878 investigation by the pro-reform New York Municipal Society found that city street sweepers were paid a minimum $1.60 per day and paid regularly even in instances when inclement weather prevented them from working. A few years before, the city had contracted out street cleaning duties to a private company, which had paid street sweepers only $1.00 per day and only for days on which they actually worked.Footnote 32

Beyond the obvious appeal of regular and above-market pay, municipal employment also offered other benefits that went over and above the official job description. Broxmeyer demonstrates that the New York Republican machine gave out light work or no-show jobs to elderly and handicapped supporters. He argues that this practice had the effect of creating a de facto old-age pension, especially for manual laborers who could no longer pursue their trades.Footnote 33 Tammany Hall also appears to have embraced this use of patronage jobs for elderly or handicapped supporters. One of the chief complaints of the Municipal Society investigation above was the “wretched and feeble condition” of the street sweepers they encountered, of whom “few among them are capable of the exertion necessary to do a full day’s work, and hardly one could command any private situation requiring strength or address.”Footnote 34 The report also criticized the fact that 1,300 men were employed to clean the streets in New York City, whereas in the British city of Liverpool, with a similar number of miles of paved streets, the same task was accomplished with only 687 men.Footnote 35 Neither of these facts was accidental. Responding to the report, the city’s Bureau of Street Cleaning admitted that many laborers were appointed as “an act of charity to worthy men, in finding them the means for the support of their families.”Footnote 36

Other patronage appointments were even more directly phantom positions meant to provide for voters who could not otherwise provide for themselves. During the Lexow Committee investigations, former bartender Max Sanftmann testified that a sympathetic political boss had helped him land a job in the Water Register’s Office in the Department of Public Works. Along with “Sixty or Seventy” other men in his office, he was paid $2.50 a day but only put in “[ten] minutes work” once a week – just enough to come in and draw his pay.Footnote 37 Although the Lexow Committee did not follow up this line of questioning any further, Sanftmann implied that similar arrangements were also common in other municipal departments.Footnote 38

Much has been written about high-level Tammany Hall politicians and bosses such as William Tweed or Richard Croker, who used their control over the distribution of city contracts and insider knowledge of city land purchases to engage in graft schemes worth millions of dollars. At the same time, Tammany Hall’s tolerance for corruption often filtered down to lower-level municipal employees, who used their positions of authority to accumulate wealth far in excess of their official salary. The most egregious cases of this low-level corruption occurred in the New York City Police Department. The Lexow Committee found extensive evidence of patrolmen appointed by local Tammany Hall ward heelers extorting bribes from saloons, brothels, and other businesses not to enforce city regulations against them. Dozens of police officers investigated by the Lexow Committee admitted they owned property worth thousands or tens of thousands of dollars, property that they had somehow bought on a $1,200 a year salary. For example, Samuel J. Campbell, a retired ward detective, was forced to admit under oath that he had $7,000 deposited in the Bowery Bank and owned three pieces of property that together amounted to a princely $36,100.Footnote 39

Taken together, these factors explain why Tammany Hall politicians believed that partisan patronage secured working-class voters’ support and why the practice was a constant motif in Tammany rhetoric. It really was one of the few viable tickets out of the tenements and into comfortable middle-class life for working-class New Yorkers. If given no better electoral options, working-class New Yorkers usually proved willing to throw their support behind a successful political machine, like Tammany Hall, in order to preserve the possibility of winning municipal patronage. However, municipal patronage was not a panacea for the problems of Gilded Age urban poverty, a fact of which working-class voters were clearly aware and frequently mentioned.

Perhaps the greatest flaw in this system was that patronage positions were highly limited and simply could not be made available to the majority of Tammany’s working-class base. During his tenure as boss of Tammany Hall (1858–1871), William Tweed vastly expanded the number of patronage jobs available to ward heelers by quadrupling the municipal workforce from around 5,000 (1858) employees to 20,000 (1871), and by sponsoring major infrastructure projects, such as the construction of Central Park, which created thousands of temporary laborer positions.Footnote 40 At the same time, this bloated municipal government and expensive infrastructure projects could only be paid for by unpopular tax hikes and irresponsible deficient spending. Between 1858 and 1871, Democratic mayors repeatedly raised the city’s property tax rate from 1.25 percent to 2.90 percent. In the same years, New York City’s debt burden increased from $12 million to $136 million – leading the city to nearly default on its obligations in 1871. These fiscal pressures of rapid tax hikes and ballooning debt were deeply unpopular with New York City’s voters and contributed to one of Tammany Hall’s largest election defeats in the mayoral election of 1872. This election, discussed more in the next section, proved to Tammany Hall politicians that there were strict fiscal limits on the resources they could spend to expand the municipal patronage pool as a way to win working-class voters before these measures aroused greater opposition from across the class spectrum. As a result of these restrictions, Tammany Hall politicians struggled to provide even a fraction of their loyal voters with patronage jobs, despite the importance of these jobs in securing working-class support.

Working-class voters seem to have understood these intertwined characteristics of machine patronage – that it offered a rare ticket to financial stability, but also that it was a highly competitive resource. This understanding can be seen in the thousands of letters that an average Tammany mayor, such as Hugh J. Grant (mayor 1889–1892), received from his working-class supporters asking for a job with the municipal government or with machine-friendly city businesses. Although the exact language varied, these letters usually followed a consistent formula. Denoting the well-understood competitiveness of these jobs, letters were often deeply ingratiating to the mayor. The writer would make a case that they were a loyal Tammany Hall Democrat and that they had suffered a form of misfortune – typically a severe injury or long-term unemployment – and that they viewed machine patronage as a form of charity of last resort. Writers rarely mentioned their qualifications for the office they were seeking, and sometimes, they simply asked for any available position. The following two letters from William H. Donnelly and Charles Freemen to Mayor Grant are representative.

Appealing to Grant’s reputation for assisting badly-off acquaintances and his background as a Civil War veteran, Donnelly wrote:

Sir thinking that you might interest yourself in my behalf and knowing you to be first in your dealing to all I have taking this method as a last resort in appealing to you to do something for me. I am a veteran of the last war … I am simply looking for a job as laborer and if your grace will bestow this favor on me you be a grate [sic] kindness hoping this may meet with your kind and favorable consideration.Footnote 41

Meanwhile, Freemen’s letter pointing to a permanent injury as proof that he would be a particularly worthy recipient of municipal patronage as a “watchman or something”: “I am a discharged soldier of the late war … I met with an accident some time ago and got a broken leg and as I am in need of employment I would ask you to be kind enough to give me a few lines to some of the departments so I could get a situation as a watchman or something.”Footnote 42

At the same time, these application letters reveal a subtle undercurrent of pessimism and dissatisfaction with Tammany Hall’s inability to provide sufficient patronage jobs for the majority of their supporters. Letters frequently mention having written to Mayor Grant and local Tammany partisans several times without response. For every hopeful William Donnelly or Charles Freemen, there appears to have been at least one Patrick Mahoney, who wrote to Grant pleadingly, “in the name of God to get me a ticket to work on the repairs of Streets so that I could eat.” He had apparently been waiting for thirty-one days in increasing desperation for a response to his first application. Mahoney’s situation is interesting because he seems like he should have been a prime candidate for Tammany patronage. His letter states that he had some unnamed “sickness” that had rendered his life “sad and gloomy.” He appears to have been a regular member of Tammany Hall, had a clearly Irish surname, and states that he was a longtime friend of the Commissioner of Public Works.Footnote 43

Other letters following up on ignored applications reveal a sense of betrayal and expressed the writer’s feeling that Tammany Hall had abrogated its electoral promise to take care of the needs of its working-class supporters. For instance, Edward Meehan Jr. wrote to Mayor Grant in 1890 that he had worked for the success of the Tammany ticket since the campaign of 1888 but that his application to join the Street Cleaning Department had been ignored. He pointedly concluded by asking the mayor to “suggest to some incoming official to provide me with a place.”Footnote 44 The fact that even politically connected Tammany Hall members like Mahoney and Meehan could not secure minor laboring positions highlights the unsuitability of patronage to solve the problems of urban poverty or meaningfully assist working-class individuals in New York City.

This limited nature of patronage positions could also lead to other negative outcomes for the city. For example, because Tammany Hall politicians recognized the link between their electoral success and their ability to provide as many patronage jobs to supporters as possible, they often gutted municipal departments by removing qualified employees who did not vote for the Tammany Hall ticket.Footnote 45 While this process did open up some positions to Tammany Hall’s supporters, it resulted in a personal hardship for the laid-off employees and undercut Tammany Hall’s argument that patronage was a form of philanthropy. It also further hurt the city’s ability to provide efficient services under Tammany governance, reinforcing one of the factors that made Tammany Hall so dependent on patronage practice in the first place.

Despite this practice, machine politicians still struggled to provide for even their most important supporters. John Romanelli was an Italian American immigrant in the heavily Italian 8th Assembly District and a longtime member of his local Tammany Hall club. His livelihood came from running a small business in which he and several companions went through dumps owned by the city’s Street Cleaning Department to scavenge for tins and other valuable metals. Romanelli was something of a local community leader and an important part of Tammany Hall’s outreach to the growing Italian American community in the district. J. Morrissey Gray, the Tammany Hall 8th Assembly District leader, was reported by another investigation witness to have said that “Romanelli was quite a help to me in the election district, among people of his own nationality there, Italians, and he [Gray] said that if he could do anything for Romanelli, he would do it.”Footnote 46

Nevertheless, in 1899, Gray apparently found the need to reward another Italian community leader, named “Labretta,” by giving him Romanelli’s old scavenging contract. Romanelli tried desperately to bribe Gray and other Tammany officials to restore his old contract – laying down hundreds of dollars he could not afford, selling his family’s gold watch, and nearly suffering a foreclosure on his house – but to no avail.Footnote 47 Gray eventually did repay Romanelli after the latter contacted the Brooklyn Eagle and had his story published, but the machine had permanently lost Romanelli and his followers’ support.Footnote 48 Romanelli would testify the following year in the Mazet investigations as a witness hostile to Tammany Hall.Footnote 49

It should be noted that investigations like that of the Lexow and Mazet Committees aimed to present Tammany Hall governance in the worst possible light, but these same patterns frequently reappear in neutral oral histories of Tammany Hall recorded in the twentieth century. Some accounts do indicate that individual Tammany Hall leaders were very popular in their neighborhoods and tie this popularity to their ability to provide for the material needs of their constituents. For example, Hell’s Kitchen resident James “Bud” Burns (b. 1911) remembered that his local Tammany Hall district leader, Owen Madden, forged a baptismal record for him when he was fourteen years old so he could get a job as a legal adult with a railroad company.Footnote 50 Burns also recalled that Madden performed many of the tasks that Plunkitt and other Tammany Hall leaders claimed made a successful politician: “Madden was worshiped around the neighborhood. He done a lot of favors for the poor. A neighbor guy died, he buried him. People around Thirty-Fourth Street that needed money for rent, he paid it.”Footnote 51

However, the majority of oral history accounts indicate that working-class individuals were generally dissatisfied with Tammany Hall governance, outside of a few exceptional politicians like Madden. In some accounts, this dissatisfaction came from a belief that Tammany politicians were not upholding their “solemn contract” to provide patronage jobs and informal charity in their neighborhood, while other accounts emphasized complaints about Tammany Hall’s inefficient delivery of city services or ubiquitous corruption. Bill Bailey, the longshoreman quoted above, often suffered bouts of seasonal unemployment. He recounted his experience trying to get a position as a municipal snow shoveler during one of these periods without a job:

Just to eat, I’d shovel snow for the city for fifty cents an hour. Boy, we’d hope there’d be a blizzard. But it became a racket because the politicians took care of their friends first. One day, we lined up 500 guys outside the clubhouse. If they were goin’ to open it up at five, we were there at three, stompin’ our feet, freezin’ in the cold outside this goddamn little clubhouse with all these politicians inside. Meanwhile, people were walkin’ in and out with letters and handshakin’. The more people goin’ in shakin’ hands with letters meant less jobs for us, and the line was gettin’ bigger and bigger. Then a guy came out, and instead of hiring 500, he made the stupid announcement that they were only hirin’ twenty-five. Well, everybody got so pissed off that they smashed in all the windows. Of course, the cops surrounded the place, and they were bangin’ and clubbin’ and pushin’. The guys fought back, beat the shit out of the cops. There was not shovelin’ that night because it was so bad.Footnote 52

Lower East Side resident Robert Leslie (b. 1885) worked as a public school teacher and later became a medical examiner at Ellis Island. Even though his teaching position came from a patronage appointment, through the favor of local Tammany politician Arthur Ahearn, Leslie’s most salient memory of the organization was its tolerance for shoddy tenement building codes and the willingness of the police to tolerate criminal gangs with connections to the machine:

Orchard and Ludlow were tenements one on top of the other with back houses. Tammany Hall permitted them to build all of that stuff. There were no parks at the time. Seward Park wasn’t even built yet…. Monk Eastman’s gang was in that area. At one time, they thought they were Robin Hoods. They said they were stealing from people who had it to give it to the others. They never gave it to the poor, but the police were afraid of them. They were protected by Tammany Hall.Footnote 53

In his later career as a medical examiner at Ellis Island, Leslie remembered Tammany Hall sending representatives to hire strikebreakers from arriving immigrants sometime before 1910 (likely because the business undergoing the strike had paid off a Tammany politician for his aid).Footnote 54 Martha Dolinko (b. 1898) was a fellow Lower East Side resident and textile worker whose only strong memory of Tammany Hall was witnessing, as a thirteen-year-old, that the city inspector for child labor would accept bribes of “a few dollars to say that children weren’t working in the shop.”Footnote 55

Another Lower East Side resident, who spoke anonymously to a 1940 Federal Writers Project’s oral history survey, stated that he had immigrated to New York from Russian Poland in 1903 and tried to open a soda fountain stand soon after arriving. Because he was not yet a citizen, he was continually harassed by local police officers and politicians for extortion money. After becoming a citizen, he joined his local Tammany Hall precinct branch and began regularly attending meetings and voting for the full machine ticket. However, in one election, he decided to vote for a non-Tammany candidate and almost immediately “had trouble with the Board of Health, Sanitation, Police Department, and Fire Department,” on the complaint that his soda foundation constituted a “fire hazard.” The respondent never voted against Tammany Hall again.Footnote 56

Reform’s Lost Opportunity

If the above section has demonstrated that working-class voters were often dissatisfied with Tammany Hall governance, including sometimes with the central campaign pledge of patronage, why did members of the working class continue to vote for Tammany politicians in such large numbers between 1870 and 1924? One should not discount the fact that at least some of the machine’s support was coerced, as was the case with the anonymous soda fountain operator. Tammany Hall politicians also had a long history of padding their vote totals through fraud and ballot stuffing, another practice that is mentioned repeatedly in the investigations and oral history accounts referenced above. However, by the period under question, New York State had established relatively rigorous safeguards against election fraud via the 1882 New York City Consolidation Act, which included provisions that required voters to provide detailed evidence of identity and residential status before voting.Footnote 57 Because of these rules, even strident opponents of Tammany Hall like William M. Ivins, head of the Electoral Laws Improvement Association, agreed that the 1882 regulations “almost entirely prevent the evils from which we suffered so long, that is, open frauds at elections in the counting of ballots.”Footnote 58 In subsequent years, Tammany politicians would find new and creative loopholes to commit ballot fraud, but it is also true that much of the machine’s working-class electoral support was genuine despite working-class grievances against it.

Although these two facts would seem to present a paradox, the resolution becomes clear when one examines working-class views of Tammany Hall’s principal political rivals, the city’s mainstream reform parties. New York City held twenty-one mayoral elections between 1870 and 1921. During this time, Tammany Hall’s candidates won in fifteen instances, while a candidate that Tammany Hall opposed won in just six instances. All six of these anti-Tammany mayoral candidates came from mainstream reform opponents of the machine: two anti-Tammany Democrats and four Republican/Fusion candidates.Footnote 59 Although coming from many different parties, these reform politicians were unified by pledges to clean up municipal mismanagement and end the self-dealing associated with machine politicians. In theory, the reform agenda should have elicited more support from working-class voters, since much of their dissatisfaction with Tammany Hall came from its flagrant corruption and the inefficient city services. In practice, however, reform politicians squandered many opportunities to win over working-class support by embracing harsh austerity policies and using elitist rhetoric that alienated voters who were otherwise open to an alternative. The result was that working-class voting behavior in this period was chiefly motivated by negative partisanship, with working-class voters having real grievances against both major parties but generally choosing Tammany Hall as their least disliked option. However, working-class discontent at Tammany Hall was never far below the surface, and this fact can be seen by evaluating the instances in which reform politicians did manage to win the New York mayorship.

Almost every mayoral election in which a reform candidate won followed a predictable pattern: Tammany Hall would commit an especially egregious scandal that was followed by an investigation and widespread newspaper coverage. Although these scandals tended to drive down Tammany Hall’s vote totals among all classes, Tammany Hall’s raw vote totals usually dropped most dramatically in working-class neighborhoods (in part because Tammany Hall performed so well in these areas during non-scandal years). Often, these scandals directly hurt the city’s working class in some way and strained their relationship with Tammany Hall enough to make them consider voting for a reform candidate in protest. For example, Boss Tweed’s thefts nearly caused New York City to enter bankruptcy and threatened to push the city into economic crisis over its unpaid debts before Tammany lost the election of 1872 to wealthy banker and longtime municipal reform leader William Havemeyer.Footnote 60 Previous historians have tended to emphasize how this crisis caused a middle-class backlash to the Tammany Hall machine, but the crisis also threatened the livelihoods of Tammany’s working-class base. Charles A. Dana, editor of the New York Sun, and a self-described advocate for the city’s workingmen, argued in 1874 that increases in the property tax and fallout from a potential default would have fallen harshly on “the working-men especially … in the form of enormous rents, the enhanced cost of every necessary of life, and above all, in the stagnation of business.”Footnote 61

Many of the victims of police extortion uncovered by the 1894–1895 Lexow Committee were working-class individuals, such as prostitutes, pushcart vendors, or saloon workers. There is also evidence that Tammany Hall lost significant working-class support before this election when the city’s Republican Party printed tens of thousands of pamphlets arguing that the ineffective policing of vice was the reason so many daughters of working-class families entered prostitution.Footnote 62 The publication of the Lexow Committee Report and this effective Republican advertising campaign led directly to a landslide Tammany defeat in 1894 and the election of reform mayor William Strong. Another Tammany loss followed in 1901 after revelations by the 1899–1900 Mazet Committee investigation, which showed that Boss Richard Croker, Mayor Robert Van Wyck, and other Tammany officials had accepted large gifts of stock from the American Ice Company and then used city regulations to ban other ice importers from using New York City’s docks throughout the 1890s. These actions gave the American Ice Company a functional monopoly over the importation of ice into the city, and soon after, they raised the price of ice from twenty-five cents to sixty cents per 100 pounds. In this era, all residents of New York City used ice to preserve perishable food, but the poorest residents paid the highest proportion of their income for the product and were the most harmed by the change. On the backs of these revelations, reform mayor Seth Low was elected.Footnote 63

From 1912 to 1913, Tammany Hall again became the target of two state investigations examining allegations of New York City police corruption and municipal officials receiving kickbacks from private companies that competed for public contracts. Tammany Hall’s boss at the time, Charles Murphy, responded by ordering New York City’s delegation to the state legislature to impeach Democratic governor William Sulzer, who had initially ordered the latter probe.Footnote 64 During the impeachment investigation, the Tammany Hall state delegation was able to find a handful of campaign finance law violations committed by Sulzer and then (with support from many Republican state legislators) impeached the governor for the first time in New York’s history. Although Murphy had successfully retaliated against Sulzer’s attempts to investigate Tammany corruption, his nakedly cynical efforts to shut the investigation down actually magnified the accusations against the machine. In the subsequent mayoral election of 1913, John Purroy Mitchel, formerly the head of a separate municipal investigation into Tammany Hall corruption, won a surprise victory due to public disgust at Sulzer’s impeachment.Footnote 65

In each of these cases, while the reform candidates tended to enjoy their strongest support from middle- and upper-class voters, they polled surprisingly well in working-class wards and assembly districts. This result is made even more interesting by the fact that working-class districts swung heavily toward the reform candidate without the total number of votes cast in these wards or assembly districts declining significantly. This pattern indicates that Tammany Hall’s poor performance was because working-class voters were casting their ballots for an alternative candidate, not staying away from the polls altogether.

However, when reform candidates did win elections, they repeatedly frittered away their opening with working-class voters by pursuing austerity policies and making little effort either to understand or to address the needs of voters who lived in the tenements. In the election following a reform mayor’s term, the Tammany Hall candidate generally won working-class wards or assembly districts at levels similar to those that the Tammany candidates had won before the scandal. As a result, in each of these six elections, the reform candidate only stayed in power for a single term before a Tammany Hall candidate returned to power. This tendency by reform mayors to antagonize working-class voters back into supporting Tammany Hall can be seen more clearly by examining the policies these mayors pursued once elected, as well as their interactions with the working class.

For example, in his inaugural address after winning the 1872 election, reform Mayor William Havemeyer (1873–1874) called for an end to political patronage and the removal of ineffective municipal employees appointed through patronage, a scaling back of mass public infrastructure projects that employed thousands of unskilled laborers, and cuts to city services, such as the distribution of money and coal to the unemployed via the city’s Almshouse Department. Because unskilled labor jobs usually had the weakest job security, services for unemployed New Yorkers disproportionately benefited working-class citizens.Footnote 66 Havemeyer also had the misfortune to be elected mayor less than a year before the Panic of 1873, a major national recession that caused cascading bank and business failures in New York City. This crisis ultimately resulted in New York City’s unemployed population rising from an estimated 50,000 workers to between 75,000 and 105,000 workers between October and December 1873.Footnote 67 In previous economic downturns, Tammany Hall mayors had alleviated the suffering of unemployed New Yorkers by sponsoring large infrastructure projects while local ward heelers distributed gifts of coal and food to needy constituents. The section above has shown that these actions were often insufficient to meet the needs of Tammany Hall’s voters, but they did help some citizens and were not actively harmful.

When confronted with a similar crisis, however, Havemeyer repeatedly refused calls by the city’s labor unions and workingmen’s groups to engage in policies that would alleviate unemployment, and he often did so in quite condescending language. For example, in an October 1873 meeting with a committee from the Federal Council of the International Working Men’s Association, Havemeyer rejected the union’s modest request for the city to fund a job placement bureau and ease restrictions on the hiring of laborers for city projects. When one of the committee members pointed out that tens of thousands of New Yorkers had become unemployed in recent weeks, Havemeyer retorted that he “did not care if 1,000,000 people were without the chance of earning a livelihood this winter.” The committee soon after walked out of the meeting in protest, with one member stating that “it was a shame to have such a man at the head of the City Government.”Footnote 68 In a meeting the following month with a delegation of unemployed laborers, Havemeyer steadfastly refused to approve any new public infrastructure projects to ease unemployment while also expressing his doubt that economic conditions were as bad as the laborers claimed. He ended the meeting by urging any unemployed laborers to simply work for a smaller wage, lecturing them that:

Labor like every other marketable commodity, advanced in price or receded just as there was demand for it, or the contrary. A number of persons who had been getting $5 a day through Internationals and trade unions, and who would not take $3 were now said to be starving to death. They all knew that when there was a demand of labor, it should be paid for, and on the other hand, when the demand became less, the value of labor decreased.Footnote 69

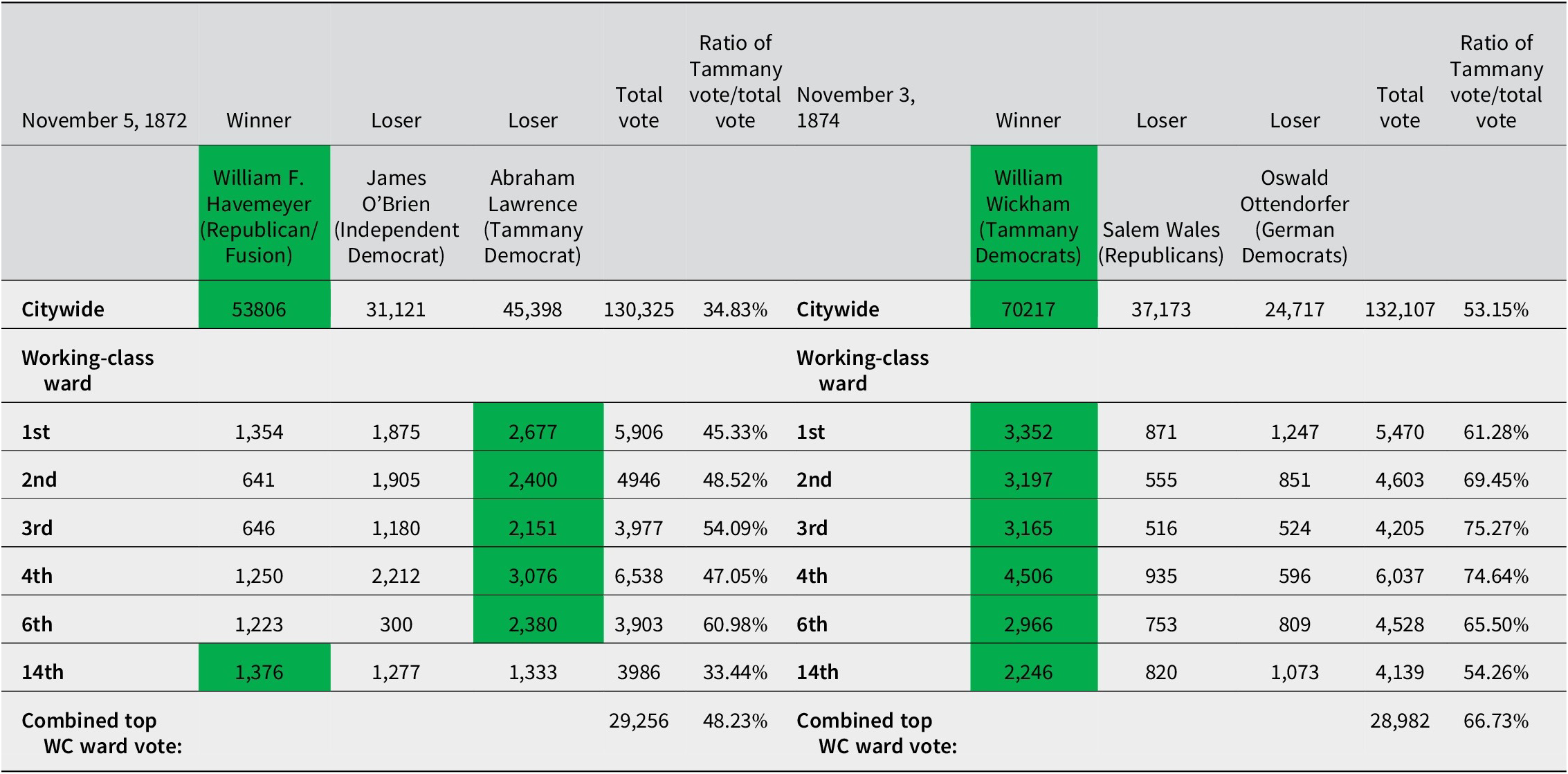

Havemeyer did not run for reelection, but his fiscal policies and general disdain for working-class New Yorkers drove this group away from reform candidates and back toward Tammany Hall in the November 1874 mayoral election. Despite a split in the Democratic Party, Tammany Hall candidate William Wickham managed to win this contest by large margins in working-class wards (averaging 66.73 percent of the vote in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 14th wards) against his citywide average of 53.15 percent of the vote (See Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6. 1870–1872 Mayoral Election Results

Table 7. 1872–1874 Mayoral Election Results

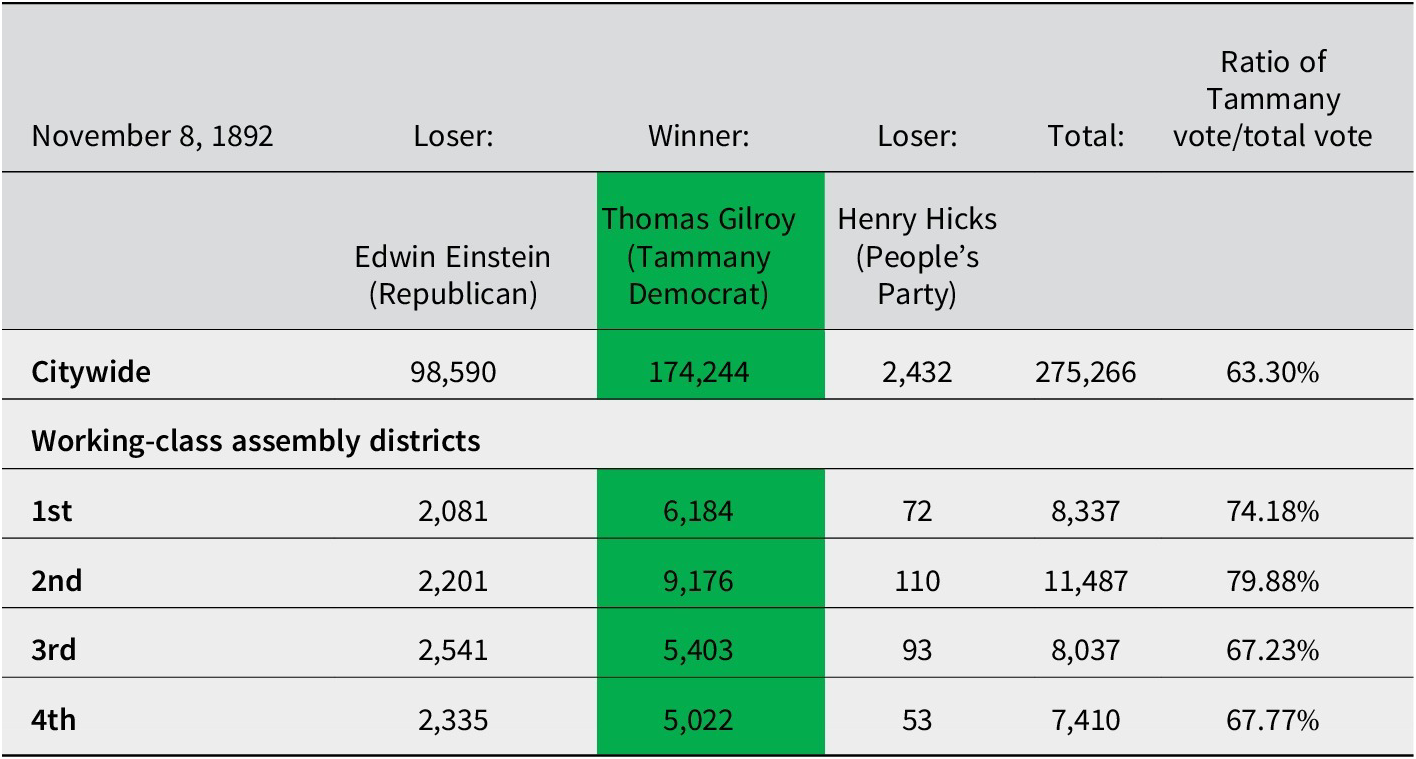

However, for the next fifty years, the Republican Party and the pro-reform faction of the Democratic Party insisted on running men exhibiting the same elitist backgrounds as Havemeyer, who likewise proved unable to appeal to the city’s other half. Indeed, many of the other reform candidates from this period come off as even more out of touch or unsympathetic to working-class concerns. In the 1892 mayoral election, for instance, the Republican Party ran a millionaire wool manufacturer named Edwin Einstein, who was well-known in the city for paying his workers “pauper wages,” including some as little as thirty or forty cents a day. When the Knights of Labor attempted to unionize his factory, Einstein paid contract labor agents to find the “cheapest Italian and Hungarian laborers” and bring them to the country so he could fire his American workforce.Footnote 70 Even the normally pro-Republican New York Times complained that Einstein was a “rich man who has fattened his purse by making the workmen lean” and mocked the decision to place his campaign headquarters at the lavish Coleman House hotel.Footnote 71 Einstein lost handily and, like other reform candidates, performed especially poorly in working-class wards (See Table 8).

Table 8. 1892 Mayoral Election Results

Two other Republican mayoral candidates who won election after major Tammany scandals, William Strong (1895–1897), a former bank president, and Seth Low (1902–1903), a former president of Columbia University and mayor of Brooklyn, similarly drove working-class voters back to Tammany Hall by adopting policies that were harmful to working-class interests. Strong, for example, in his 1894 election victory speech, laid out an agenda that began by calling for the firing of all patronage employees through the “immediate passage of an act which will free the municipal government from the loathsome presence of these miscreants and empower the new Mayor to supplant them with honest, capable and honorable men.”Footnote 72 By the end of his term, Strong had succeeded in moving most city governing jobs onto a merit-based civil service system that tended to reward better-educated and better-off applicants than Tammany’s patronage practice.Footnote 73 Before becoming mayor of New York in 1902, Low was already famous as an advocate for banning “outdoor relief,” a popular form of public charity that supported tens of thousands of needy New Yorkers by giving them direct payments of coal, food, and money.Footnote 74 Fearing that free charitable assistance made the poor dependent on it, Low was a driving force behind Brooklyn’s decision to ban outdoor relief in 1878 and ensured the practice was banned across the East River when he helped author the 1898 Greater New York City Charter.Footnote 75 Tammany Hall’s candidates, replete with flaws of their own, benefited from the comparison with their reform counterparts.

It is somewhat remarkable that this sequence of pro-reform candidates continued to pursue policies harmful to New York City’s working class, despite abundant evidence that they needed these voters to field a winning electoral coalition in the city. However, it also seems clear that reform politicians, who came invariably from middle- and upper-class backgrounds, tied their own identity closely to a belief in laissez-faire individualism. This ideology offered a self-serving but apparently genuine belief that justified the wealth and social status that reform politicians enjoyed and provided them with a lodestar for their economic policy views.Footnote 76 In particular, a theme running through almost all pro-reform economic policies was an opposition to the use of the state to assist needy New Yorkers out of a fear that such aid would cause the aid recipient to become less hardworking, more indolent, or dependent on future aid.Footnote 77

David Huyssen, in Progressive Inequality: Rich and Poor in New York, 1890–1920 (2014), has also shown that, among wealthy Gilded Age New Yorkers, this ideology manifested itself in a habit of viewing poorer New Yorkers as childlike, ignorant, and emotional, and in need of the guiding hand of well-educated, wealthy reformers like themselves. This dichotomy was sharpened by religious and ethnic distinctions between the overwhelmingly Protestant and native-born wealthy New Yorkers and the city’s working class, which included large numbers of New Yorkers from Catholic and Jewish and immigrant backgrounds.Footnote 78 While not blind to the fact that their policies were unpopular in working-class neighborhoods, reform candidates often saw it as their duty as members of the wealthier classes to enforce those positions on the rest of the city, with or without their consent.

Such class snobbery by reform figures also contributed to a lack of curiosity or interaction with working-class New Yorkers that hid the real fault lines existing between Tammany Hall and its base. It also helps explain why the New York Republican Party and pro-reform County Democracy were never able to create an election apparatus on the scale of Tammany Hall’s vaunted organization of ward heelers and district captains. Both the investigations and oral history accounts quoted in the first section of this article show that working-class voters had many strong opinions about their local Tammany Hall ward heeler or politician. These opinions were often negative, but they prove that Tammany Hall had a presence in working-class neighborhoods. Those same accounts, by contrast, contain almost no mention of either the Republican Party or reform Democratic figures.

At the same time, even if reform parties had wanted to do so, there is evidence that their policies were so anathema to working-class New Yorkers that they would not have been able to get a hearing. For example, Helen Boswell, leader of the New York City Women’s Republican Club, claimed in 1900 that Republican male canvassers were simply “not welcome” in most tenements of Manhattan. She reported that women canvassers, seen as less threatening by residents, enjoyed more success in these neighborhoods, but conceded that even “our women were often met with derision and with threats of boiling water poured over them” and that “a few potatoes were thrown by the irate Irish ladies.”Footnote 79

Conclusion

This article opened with a series of quotations from George Washington Plunkitt, a man whose colorful anecdotes did more than perhaps any other figure to shape the historical memory of Tammany Hall. While Plunkitt highlighted several important factors about Tammany Hall’s relationship with the working class and the role of patronage and charity in maintaining this relationship, the facts of Plunkitt’s career expose where this narrative falls short. Plunkitt was Tammany Hall’s leader in the 15th Assembly District, centered on Hell’s Kitchen. Here was exactly the kind of poor, densely populated neighborhood with high unemployment that might have benefited the most from programs like job patronage and informal machine charity. Early in his career, from the 1870s to the 1890s, Plunkitt had lived up to his ideals – providing for the material needs of his constituents and winning a following for his generosity. As a state senator, he directed infrastructure spending back to his district by authoring bills funding the Washington Bridge, a district courthouse, public parks, and viaducts. He introduced several bills to raise the salaries of New York City policemen and firemen, actions that made patronage appointments an even more attractive proposition.Footnote 80 While Plunkitt upheld his “solemn contract,” he was untouchable. He won all twelve state senate races he ran in between 1883 and 1903.

But at some point, he stopped trying to maintain this reputation as a provider for his community and had instead begun exclusively lining his pocket with bribes from corporations, as well as graft from real estate speculation informed by his knowledge of city plans. A 1910 survey of a section of the city mostly overlapping with Plunkitt’s district found that, out of 370 working mothers interviewed, not a single one of them or their husbands had ever received a patronage job or an act of informal charity from a member of Tammany Hall. Similarly, a study of 183 families in the neighborhood with juvenile delinquents found that only two of these families had ever received any form of help from a Tammany official like Plunkitt.Footnote 81 Separately, Plunkitt’s local ward association was credibly accused of shaking down saloonkeepers in his district.Footnote 82

Despite the abrogation of his solemn contract and his shameless self-enrichment, Plunkitt was reportedly shocked when, in the state senate election of November 1904, he lost to a young reform Republican named Martin Saxe.Footnote 83 Saxe was, in some ways, similar to many reform candidates who ran against Tammany Hall figures. Born to a well-off family, he had earned a college degree at Princeton University and taken a career as a lawyer, including a stint at the City Corporation Counsel’s office. But in other ways, he managed to do what so many other reform candidates did not: show that he cared about the concerns of working-class New Yorkers and propose policies for their benefit. In his time at the Corporation Counsel’s office, he prioritized collecting back taxes owed by wealthy New Yorkers, including some $157,000 owed by the Vanderbilt family alone.Footnote 84 In his 1904 race against Plunkitt, he and his supporters campaigned door to door with this message and attacked Plunkitt for selling out the district to big corporations like the New York Central Railroad. If elected, Saxe pledged to act independently of business interests. While most reform candidates came across as dourly condescending, Saxe’s public speeches were “practical, to the point, and seasoned with humor.”Footnote 85

Saxe undoubtedly deserves much credit for his 1904 victory, but he also serves as a final proof point that machine politicians like Plunkitt were much weaker than their reputation suggested. Tammany politicians had hit upon a winning pledge by promising to provide for the material needs of their constituents, especially among members of the working class. But, because of both the limited nature of patronage opportunities and their greed, these politicians also tended to underdeliver and to govern poorly, using their political power more for self-enrichment than for the economic betterment of their constituents. Working-class voters repeatedly expressed their dissatisfaction with how political machines worked in practice and showed that they would have been willing to vote for an alternative to Tammany Hall – if that alternative had not actively alienated them with condescending rhetoric and harmful policies. In the end, Plunkitt understood that his working-class voters wanted to feel materially secure, especially by finding a steady, well-paying job that could provide for the needs of their families. His unwillingness or inability to meet that need caused his electoral defeat and demonstrates why the machine politicians’ solemn contract was, all too often, just a hollow bargain.

Competing interests

The author declares none.