1. Introduction

In an animated film about communication and dementia a few years ago, I likened living with dementia to being in a foreign country:

People keep telling you to do things and asking you things. You don’t know what they want. You feel trapped and frightened. There’s no one you can ask, no one you can talk to (Wray, Reference Wray2017).

Many dementia carers who watched the film have said they found the observation logical, meaningful and helpful. The comparison makes sense. In both cases, we have people who feel separated from their surroundings and whose limited linguistic capabilities risk undermining their wellbeing. All the same, I had a niggling worry about it. Are these two situations genuinely comparable, all the way down? What happens if you unpack the layers?

This is exactly the kind of question I love to ask. My D. Phil supervisor once called me an iconoclast: if something is standing there looking solid, I want to kick it and see if it wobbles. In my doctoral thesis, I challenged the core assumption (at the time) that the right hemisphere of the brain was barely involved in language processing. In my research on formulaic language, I questioned the central claim in grammatical theories (of the time) that we always/mostly compose our linguistic output from scratch rather than from sets of lexicalised patterns. I also offered an alternative model of the evolutionary origins of language that did not entail first combining single words into simple sentences.

One aspect of an iconoclastic approach is noticing when disciplines or subdisciplines have become too introspective to notice that others are asking and answering the same questions, but in completely different ways. There can be value in evaluating whether these silos of investigation can and should be broken down, allowing more integration between traditions, assumptions and theories.

Dementia and second language learning are a case in point. Within and beyond linguistics, there are researchers and practitioners who are experts in the challenges of communication when someone develops dementia. There are separate researchers and practitioners with knowledge about the challenges of communication when someone arrives in a foreign country with little or no knowledge of the language. Should their work be compared and combined?

In this article, I take one approach to progressively figuring out how similar these two situations really are and thus what, if any, opportunities there are for cross-fertilisation. I don’t have an axe to grind here, regarding whether or not they are truly similar – it’s a matter of exploration. What I do have an axe to grind about is the importance of asking this sort of question. Too often, I believe, we are missing a trick by not realising that others, within their own domain, are working on something similar to ourselves, such that we might learn much from their findings and methods.

My first step, below, is deciding what exactly to compare. I then conceptualise the relevant components of communication, as the basis for looking for similarities and differences at different stages of the communication process. Although this isn’t the only way a comparison can be done, it offers a layered structure that helps us understand not only what is the same and different but also why and how.

1.1. Comparing chalk and cheese?

Comparing the experiences of language learners and people living with dementia is not straightforward, because there is a major imbalance in the quantity and nature of first-hand accounts. Millions can attest to the struggle of using a foreign language abroad, but few people living with dementia have reported their experiences with impaired communication (though see Lipinska, Reference Lipinska2009; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2018; Sabat, Reference Sabat2001, Reference Sabat, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010; Swaffer, Reference Swaffer2016; Taylor, Reference Taylor2007). In particular, by the time they reach the most difficult and distressing stages of impaired communication, they lack a means of recounting them (Zweijsen et al., Reference Zweijsen, van der Ploeg and Hertogh2016).

This unevenness prevents fair comparison of the direct experiences, and so I will focus instead on the advice given to those whose role is to interact with second language users and people living with dementia. I am also limiting the enquiry to two sub-populations that strike me as particularly suitable for comparison: people living with Alzheimer’s Disease (PADs) and asylum seekers and refugees arriving in a new country, where they must use a second language (2LRs).

Alzheimer’s Disease is a degenerative brain disease which, over time, undermines a range of functions including ‘attention, orientation, … executive function, … praxis, and visuospatial abilities’ (Camicioli, Reference Camicioli and Quinn2014, p. 5). Typically, PADs also have impairments in language (e.g. word-finding difficulties), memory (e.g. recalling recent events and conversations) and general information processing (e.g. combining information and interpreting it) (for an overview of symptoms see Wray, Reference Wray2020). Disorientation, confusion and loss of confidence are experienced by PADs, often resulting in depression, loneliness and social withdrawal (Bergman-Evans, Reference Bergman-Evans2004; Norberg et al., Reference Norberg, Lundman, Gustafson, Norberg, Fischer and Lovheim2015; Wray, Reference Wray, Stern, Sink, Wałejko and Ho2022). Taylor (Reference Taylor2007, p. 152), a PAD, comments on losing personal agency and being overlooked by others, who consider him less capable than he actually is. Alzheimer’s has an onward impact on relationships and social integration (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Horne, McEvoy and Williamson2018, p. 863) and a detrimental effect on both professionals and family members in a caring role. At the onset of Alzheimer’s, there is almost no externally detectable impairment in communication; by the end there is total muteness. I will focus on the middle stages, where PADs’ difficulties undermine the effectiveness of communication, but a little perseverance can improve outcomes.

Asylum seekers want permission to stay in a new country on the grounds of persecution or human rights violations in their own country (Refugee Action, 2024). Those granted asylum are ‘refugees,’ protected under international law (Amnesty International, 2024). Asylum seekers and refugees often arrive traumatised and disorientated. Notwithstanding their capacity to use their first language and possibly others, often, their interaction must be in a language they have low proficiency in. Even where asylum seekers and refugees can speak the language of their destination country, their journey may involve lengthy stays in other places, where they may have no knowledge of the language and might not be motivated to learn it, since it would signify an expectation of staying there, rather than moving on (Council of Europe, n.d., p. 1). The lived experience of refugees and asylum seekers varies widely, but the prevalence of trauma and stress, combined with being unable to communicate in an unfamiliar environment, can be emotionally highly challenging. Baker (Reference Baker1990, p. 65), who, as an unaccompanied child refugee, arrived in the UK from Germany shortly before WW2, speaks of

a sense of isolation and a gnawing aching need for acceptance, love and security. The feeling of being isolated became increasingly more acute and intense as meaningful communication with almost everyone became impossible.

Thus, both PADs and 2LRs can be highly vulnerable, feel bewildered and out of place, and struggle to understand and be understood as they attempt to express vital messages. Support may come from trained staff, volunteers, passers-by and family members.

In order to capture and compare the specifics of each situation, in section 1.2, I conceptualise the constraints on the success of a ‘message event.’ The subsequent sections examine the stages in that model, comparing the detail in each scenario and the advice associated with it, to establish the fundamental similarities and differences between the communicative experiences of PADs and 2LRs.

1.2. Conceptualising the determinants of successful interaction

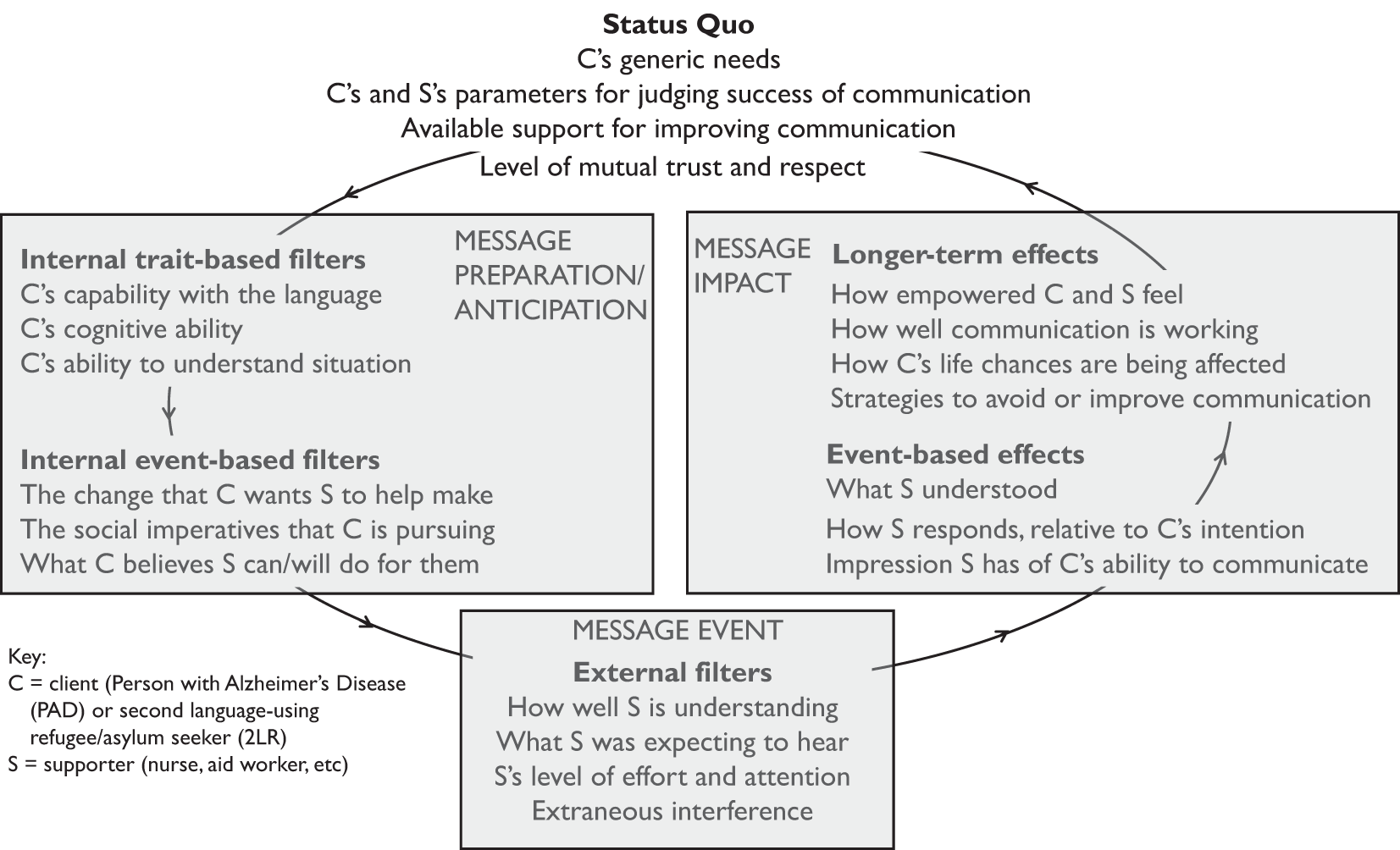

I begin with the premise that when we speak, write, sign, gesture, sigh or tut, there is a purpose to it. I have argued previously (e.g. Wray, Reference Wray2020) that interaction generally occurs when the speaker wishes to make (or prevent) a change to their experiential world but requires another individual to act as their agent to achieve it. Figure 1 offers a conceptualisation of the elements determining how successful a message event is. By ‘message event,’ I mean a single attempt by an individual (the ‘client,’ C, who is either a PAD or a 2LR) to express a message to someone else (the ‘supporter,’ S, such as a care professional or family member in the one situation and an aid worker or medical practitioner in the otherFootnote 1).

Figure 1. Determinants of the success of interaction.

Message events occur within a general context (the status quo). The message is filtered by C’s capacity to communicate (internal trait-based) and current intentions and beliefs (internal event-based). Reception of the message event is further filtered by S’s capacity to decode and make sense of what is said. The outcome generates impact on each party: immediate to the situation (event-based) and longer term. The latter feeds back into the status quo beliefs and assumptions shaping future events.

2. Status quo

The status quo is the set of general conditions under which the interaction operates. Four factors are identified in Figure 1.

2.1. Client’s generic needs

Needs represent the shortfall between what someone has and what they perceive as required for adequate wellbeing or advantage. Generic needs are relatively stable within the client’s overall situation, and often define how others see them. For example, 2LRs present as having a range of very practical needs, such as for ‘basic information on where to sleep, where to go next, where to find medical care for their children and themselves, what supplies to take and where to charge their phones or buy a Sim card’ (Hannides et al., Reference Hannides, Bailey and Kaoukji2016, p. 19). Such needs are easily acknowledged, and assistive interactions are essentially transactional, with tangible evidence of success. Secondary material needs (e.g. for less vital information and luxuries) risk remaining unmet when communication is effortful. As Rehbein (Reference Rehbein, Knapp, Enninger and Knapp-Potthoff1987, p. 245) found, ‘migrants try to articulate with the means available to them and to adapt their needs to these means,’ which creates a ‘self-imposed reduction of their own system of needs’ (original emphasis).

The situation for PADs is different. Although those living alone may require practical support with shopping, transport, housework, and personal care, for example, those in residential care or with a full-time carer are often considered to have few ‘genuine’ unaddressed practical needs. Often, PADs are viewed as poor judges of their needs, worrying over nothing, or holding false beliefs about their situation. As a result, there can be a conflict between what the PAD wants and what the professional or family carer believes is possible, or appropriate. This conflict can lead to deflecting behaviours, such as ignoring messages and/or failing to read between the lines about an underlying need (Clegg, Reference Clegg2010; Wray, Reference Wray2020, Reference Wray2021). Family carers report setting aside attention to the PAD’s unachievable material goals, in favour of emotional support (Bergström, Reference Bergström2025).

One respect in which the needs of 2LRs and PADs are similar, however, relates to the impact of pre-existing and developing medical conditions. Typical comorbidities in PADs include impaired hearing and/or sight, diabetes, heart disease and general frailty. Meanwhile, 2LRs may have contracted diseases in transit camps or have existing illnesses or injuries, sometimes due to torture or mistreatment, and often have received no treatment during the journey (World Health Organization, 2021, p. x). Illnesses and injuries, particularly when communicating about them is difficult, can lead to depression, anxiety and also loneliness, a profound and complex condition, less about being on one’s own than experiencing detachment from others (Applebaum, Reference Applebaum1978) and loss of personal agency (Wray, Reference Wray, Stern, Sink, Wałejko and Ho2022).

Furthermore, both PADs and 2LRs experience anxiety and loss, including being away from ‘home’ and/or separated from relatives and friends. Hannides et al. (Reference Hannides, Bailey and Kaoukji2016, p. 4) found that ‘refugees who stay in regular contact with other refugees and who have wide communication networks of family members and friends (via mobile networks and social networking sites …) were likely to be more resilient than those who were less connected.’ In both cases, then, it is vital to help clients build up their social reserve, ‘the currency of resilience located in a person’s cultural and social context, both local and global’ by engaging positively and fruitfully with others (Wray, Reference Wray2020, pp. 76–78).

Unmet needs can engender agitation in PADs (Van Manen et al., Reference Van Manen, Aarts, Metzelthin, Verbeek, Hamers and Zwakhalen2021, p. 2) and also in 2LRs, where ‘social workers face threats and abuse from those affected, placing them in emotional and physical danger’ (Soliman & Gillespie, Reference Soliman and Gillespie2011, p. 3). Agitation is a response to the enforced ‘radical restructuring of [one’s] cognitive, emotional, symbolic and assumptive world’ (Baker, Reference Baker1990, p. 65), often with too little certainty and understanding for it to be effective. While mental health support for refugees is a recognised need (https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/our-work/mental-health-support-for-refugees-and-people-seeking-asylum/) it remains rare for PADs, even though it can be remarkably effective (Lipinska, Reference Lipinska2009; Sabat, Reference Sabat2001, Reference Sabat, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010).

Dignity and autonomy are also a shared need for PADs and 2LRs. Often, PADs are spoken for and have to tolerate others taking over highly personal matters of care and finance. Similarly, one refugee in Morrice et al.’s (Reference Morrice, Tip, Collyer and Brown2021, p.692) study commented:

I wanted to read my own letters and understand instead of asking my husband. I didn’t want anyone to go to the hospital with me; I wanted to go and have my own privacy and understand what they were saying.

2.2. Parameters for judging success

At the fundamental level, interaction is successful when the speaker harnesses the agency of the hearer to make a desirable change to their experiential world (Wray, Reference Wray2020). Both PADs and 2LRs are in the same position, needing to achieve goals and lacking certainty that they can do so, given their limited linguistic resources. However, hearers are not always well-attuned to the speaker’s purpose and can be insensitive to failure. If a PAD asks a simple question, but their true purpose is to get attention via a sustained conversation, a brush-off reply will not satisfy their needs. Similarly, if aid workers are not good at putting themselves into the shoes of the 2LR, they might judge a conversation successful because they replied ‘appropriately’ even though the 2LR’s goal was not met.

Communicative success is also judged relatively. 2LRs know they cannot communicate as effectively in the L2 as in their L1 and the constant jeopardy of not achieving necessary goals could instil a permanent sense of low communicative success. With PADs, the point of comparison is how much easier it used to be to communicate. Where 2LRs can point to knowledge that they couldn’t reasonably be expected to have, PADs are confronting acquired limitations in what they ought to be able to do, which could make it more difficult for them to accept compromised outcomes.

Meanwhile, supporters (PAD carers; aid workers and medical professionals helping 2LRs) have two reference points for comparing success. One is communication with people who are not impaired or are not struggling with an L2. In this comparison, interactions with the client are in deficit. The other comparator is their previous experiences with the same client, or comparable ones, against which the present interactions could be judged more successful or less. Clients and supporters, then, will not necessarily agree about what ‘success’ means.

The advice offered to supporters of 2LRs and PADs reflects and, indeed, magnifies the differences just described. With regard to dementia, although there certainly is evidence that symptoms and/or quality of life can be improved through medication (Profyri et al., Reference Profyri, Leung, Huntley and Orgeta2022), psychological therapy (Orgeta et al., Reference Orgeta, Qazi, Spector and Orrell2015) and social and cultural programmes (Delfa-Lobato et al., Reference Delfa-Lobato, Guàrdia-Olmas and Feliu-Torruella2021), people with a dementia diagnosis are generally perceived as ‘helpless and unable to make decisions or participate in the activities they were involved in previously’ (Shatnawi et al., Reference Shatnawi, Steiner-Lim and Karamacoska2023, p. 2024). Given that no future improvement is anticipated, the focus in support tends to be on making the best of the situation and being satisfied with less, as ‘our commonplace notions of what counts as communication [are] brought into question’ (Allan & Killick, Reference Allan, Killick, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010, p. 217).

In contrast, the advice for 2LR supporters focusses on short-term workarounds such as using interpreters and translations, followed by opportunities for 2LRs to build up their L2 skills, if they wish to. The eight-point summary of recommendations in BBC Media’s Voices of Refugees (Hannides et al., Reference Hannides, Bailey and Kaoukji2016, pp. 32–34) accepts that the L2 is not the best medium for achieving success: ‘Share available information, in a language the refugees know’; ‘Face to face conversations with agencies, in the appropriate language’; and ‘Train NGOs and volunteers to … know the right languages’ (my emphasis). Where no interpreter is available, transactional outcomes are prioritised. The guidance Effective communication for displaced persons, directed at physiotherapists (Physiopedia, 2025), characterises success in terms of a shared understanding of the medical challenge and the delivery of a treatment plan: ‘The concept of “effective communication” covers the ability to listen, as well as interact with clients based on a mutual understanding’ (Physiopedia, 2025, my emphasis).

While advice to both supporter types acknowledges that effective communication is more than just exchanging raw linguistic meanings, and that clients must be given time to ‘tell their story,’ the purposes seem to be different. For 2LRs, storytelling helps them recover from trauma, while listening to PADs’ stories is a gesture towards dignity rather than change or permanent relief.

2.3. Support for improving communication

The most prominent communication support for 2LRs is interpretation and translation. The UNHCR (2016) states that ‘communicating in the languages spoken by transiting refugees was a priority – not just to disseminate information but also to avoid marginalizing those who did not understand English.’ Effective medical interventions also ideally let 2LRs use their first language (British Medical Association, 2024). Interpretation and translation are costly, and with so many locations, particularly transitory stops, receiving people from so many different countries, there is, unsurprisingly, patchy provision (Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture, 2024).

However, not all languages need to be covered. The WHO study into the linguistic needs and preferences of refugees in Greece (Ghandour-Demiri, Reference Ghandour-Demiri2017, p. 7) found that:

Native speakers of the Kurdish dialects Kurmanji and Sorani are less likely to understand each other’s languages, but more likely to understand a third language, such as Arabic. Some Kurmanji and Sorani speakers would prefer to receive written information in Arabic, as they were not taught to read or write in their mother tongue.

In the absence of professional interpreters, family members and friends often step in. McGarry et al. (Reference McGarry, Hannigan, De Almeida, Severoni, Puthoopparambil and MacFarlane2018, p. 3) highlight a consequential problem in healthcare: ‘family members and friends are not trained as interpreters and are unlikely to have the appropriate medical vocabulary, leading to inaccurate and incomplete transmission of information.’ There is a particular issue where the most linguistically proficient family members are children, since this alters the family dynamics, exposes child and adult to embarrassment and shame and often disrupts the child’s schooling. McGarry et al. (Reference McGarry, Hannigan, De Almeida, Severoni, Puthoopparambil and MacFarlane2018) also point out that while AI is increasingly used for translation purposes, it is a poor substitute for trained professional interpreters.

The use of interpreting and translating in the 2LR context contrasts starkly with the situation for PADs and their carers, where there is no equivalent, even though PADs certainly can be difficult to understand. For example,

He says things like, ‘I’ll just put away my sailboat’ or ‘I felt a big decoration when they came in.’ There are obscure questions that I don’t know how to answer: ‘Will they be coming here – the pilots?’ and ‘Are we going on the colour-wheel?’ or ‘When are we going to the circus?’ (Ormrod, Reference Ormrod2019, p. 242).

Family members, aware of an individual’s interests and common malapropisms, and willing to persist until meaning is revealed, are the best hope for ‘interpreting.’ As with 2LRs, this can alter the dynamic of the relationship, but with dementia, that is a much more readily recognised transition.

While advice to supporters of PADs is full of guidance on how to coax out more information, despite limited linguistic capabilities, I found almost nothing of that nature in the guidance to aid workers. It seems to be an unintended consequence of the ideal of using interpreters and translations, that little attention is paid to how to facilitate communication when these options are not available. Yet this situation must occur often. The main suggestion is to use pictures and real objects as referents (Council of Europe, n.d., p. 2; Ghandour-Demiri, Reference Ghandour-Demiri2017, p. 8), and this matches the dementia context, where they are used both to stimulate reminiscence and to assist with transactions. For example, care staff often present PADs with a choice of real plated-up meals, rather than only asking them in words which they would like (National Care Forum, 2022).

Another contrast between the two contexts regards language training. It is assumed that 2LRs, once in a permanent location, will be interested in learning the language in order to enhance their life-chances. However, language training is not offered to PADs, who are assumed to be on a downward trajectory (even though language-building support is offered to people with reversible linguistic disabilities, such as stroke-induced aphasia). Speech and language therapists do work with people living with dementia, but the emphasis is on how unimpaired interlocutors can enhance communicative practices, with only a few tips for the affected person, such as circumlocution, drawing, miming, waiting for a word to ‘reappear’ in its own time, managing frustration, and doing crosswords and quizzes, along with telling interlocutors what they should do to help (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, 2024).

2.4. Respect and trust

Finally, the shape of communication is significantly influenced by the status quo level of trust and respect between client and supporter. With both 2LRs and PADs, there is a power imbalance, favouring the supporter as the more knowledgeable and proficient communicator. Clients can easily develop low trust in supporters, if they perceive failure to get assistance as an expression of the power differential. Meanwhile, supporters can develop low respect towards clients, who, weak in expressing themselves, are perceived as needy.

Respect and trustworthiness are closely bound: not being trustworthy will be interpreted as disrespectful, while those expressing low respect for others are less likely to be trusted. Not surprisingly, then, supporters of both 2LRs and PADs are advised to build trust and be respectful. The outcomes, however, are different.

Advice to aid workers recognises that many refugees have experienced disrespect in their home country, during their journey and after reaching their destination. Driven from their country because of persecution or oppression, they may have learned to distrust those in authority. One third of the refugees that Ghandour-Demiri (Reference Ghandour-Demiri2017, p. 8) interviewed in Greece did not want information about navigating the asylum system, accessing healthcare, housing and education and finding family members, because of ‘a lack of trust towards aid organizations and government authorities.’ In the healthcare context, gaining 2LRs’ trust relies on ‘creat[ing] an environment where they feel safe to communicate and share information’ (Physiopedia, 2025). This entails clearly explaining everyone’s role, creating rapport, and listening carefully to the client rather than making assumptions (Physiopedia, 2025).

The Council of Europe (n.d., p. 1) advises that, in initial interviews, volunteers’ approach be ‘friendly, supportive and strengths-based.’ In establishing what languages and literacy a client has, they must ensure it ‘doesn’t seem like an exam or leave people feeling that they have failed in some way.’ The same document advises respectful restraint: ‘asking refugees if they plan to stay in the country they are presently in, whether they are looking for work or whether they want to learn the language of that country, could compromise them. If in doubt, don’t ask!’ (Council of Europe, n.d., p. 1).

Interpreters can undermine trust if they have inaccurate knowledge (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jaffe and Mutch2019, p. 672), limited linguistic competence or a different political affiliation (Hannides et al., Reference Hannides, Bailey and Kaoukji2016), or are indiscreet (British Medical Association, 2024): ‘There have been reports of interpreters asking personal questions, and giving out personal opinions and advice, rather than translating directly’ (Refugee Council of Australia, 2019). Confidentiality issues can surface when interpreters are from the 2LR’s own community (Physiopedia, 2025) and also when they are from a different ethnic group (Ghandour-Demiri, Reference Ghandour-Demiri2017, p. 9). The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture (2024) proposes: ‘If your patient is concerned about confidentiality, you can withhold their name from the interpreting service, offer to call them by another name during the consultation, and/or request an interpreter from another state where possible.’

PAD supporters, similarly, must exercise respect and trust, centred on ‘Person-centred communication, a style characterized by recognition, negotiation, facilitation and validation’ (Van Manen et al., Reference Van Manen, Aarts, Metzelthin, Verbeek, Hamers and Zwakhalen2021, p. 9). However, whereas the reduced communicative abilities of 2LRs are effectively a trigger for greater attention to respect and trust, in the case of PADs, the situation is more complicated, with significant dilemmas for supporters.

One PAD, ‘Ruth,’ interacting with six different carers (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Norberg and Jansson2001), became physically resistant when her personal space and privacy were invaded. The staff’s response was to maximise her experience of respect from them, by asking permission before entering her space or touching her body. However, they could not counter her sense of intrusion when they leant over her bed or used physical restraints on chairs during meals. The staff acknowledged that while they and Ruth wanted ‘to maintain her privacy, autonomy and identity’ they often had to override these priorities in favour of her safety (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Norberg and Jansson2001, p. 261). They found Ruth’s demands contradictory and sometimes manipulative, and such experiences can leave a supporter unwilling to trust what the PAD says, leading, in effect, to less respect for their stated wishes. This is an understandable response in the circumstances, underlining Kitwood’s (Reference Kitwood1997, p. 46) observation that the wide range of disrespectful behaviours often observed in dementia care staff, which he terms ‘malignant social psychology,’ are not necessarily enacted by bad people, but rather are a reaction to just this kind of dilemma.

With PADs, one of the biggest risks to respect and trust relates to deception. Although ‘treachery’ is the first item in Kitwood’s (Reference Kitwood1997, pp. 46–47) list of unwelcome ‘depersonalising tendencies’, most healthcare workers and family carers admit lying to PADs (Kirtley & Williamson, Reference Kirtley and Williamson2016), whether to make their own lives easier or protect the PAD from difficult emotions. I have discussed this topic at some length (Wray, Reference Wray2020, pp. 219–245), with particular consideration of the SPECAL method (Godel, Reference Godel2000; James, Reference James2008), where deceptions are preplanned and consistently used, to keep the PAD ‘contented.’ I have challenged the simplistic assumption that deception is disrespectful in all circumstances, in favour of a more nuanced understanding of motivations and choices, which recognises how the significant dilemmas of dementia carers are exacerbated by society’s selective squeamishness about deception (Wray, Reference Wray2020, p. 239).

At first sight, then, there is no reason why, in relation to respect and trust, the advice to supporters of 2LRs and PADs should be different. However, in practice, the loss of cognitive acuity in the latter creates a conflict between the client’s wishes and the supporter’s imperatives. At that point, it is a power struggle that the PAD is unlikely to win, and the onus is on supporters to remain humane.

3. Internal trait-based filters

What and how someone says something, having been shaped by the status quo, is now filtered through the speaker’s core capabilities for formulating an appropriate message. Three such internal traits are considered here.

3.1. Linguistic capability

While 2LRs and PADs appear similar, in needing to communicate using limited linguistic abilities, the causes of those limitations are significantly different. Even if lacking core lexical and grammatical knowledge, phonological accuracy and fluency, 2LRs have intact faculties for processing, memory, language production and language comprehension. In contrast, PADs often possess most of their previous linguistic knowledge but cannot reliably access and/or deploy it.

Nevertheless, we would anticipate similar advice for minimising the impact of limited linguistic abilities. For example, what should supporters do if the client:

a. can’t produce a specific word, e.g. can’t name a body part or food type, express time relationships, use prepositions to indicate location?

b. doesn’t have grammar to combine referents into coherent meaning?

c. is generally incomprehensible?

d. doesn’t understand the supporter’s utterances?

For 2LR supporters, most advice centres on (c) and (d). The Council of Europe (n.d., p. 2) toolkit for initial meetings with refugees recommends: ‘If you don’t share a language, and the refugee is a beginner in the target language, keep everything as short and simple as possible. You may need to use simple gestures, or to repeat or rephrase what you say.’ The UNHCR (2011, p. 11) advises ‘active listening’ and ‘ask[ing] him or her to clarify or repeat anything that is unclear or seems unreasonable.’ Physiopedia (2025) recommends physically positioning oneself for evident engagement, leaving the client time to speak, not interrupting, not judging the content, using non-verbal cues to confirm interest, using open-ended prompts and questions to elicit more information, and paraphrasing back to indicate comprehension. Essentially, the advice to aid workers is focussed on bridging the information gap rather than the communication gap. The latter is taken as inevitable and, implicitly, relatively unassailable in the absence of an interpreter.

With PADs, it is different. Given that the PAD used to have access to full knowledge of the language, and may well display plenty of linguistic breadth at times, supporters are encouraged to deal with (c) by addressing (a) and (b) (e.g. Caughey, Reference Caughey2018). If a PAD can’t retrieve a word, the supporter might gently suggest one or look for semantic links between a malapropism and the intended word. In the early and mid-stages, Alzheimer’s does not typically disrupt grammar, so where an utterance doesn’t make sense (b), the problem is typically interpreted as (a). Even in relation to the client’s comprehension (d), the advice is more granular than for 2LR supporters: use higher frequency words, maximise explicitness by using full referents rather than proforms, be succinct so as to minimise reliance on the PAD’s short-term memory, simplify grammar and formulate questions that offer explicit answers as options (see Wray, Reference Wray2020, p. 124 for an overview, along with caveats).

At the linguistic level, then, the major difference underlying the superficial similarities between 2LRs and PADs is quantity versus quality, with 2LRs knowing little but being able to operationalise what they have, while PADs potentially still know a great deal of what they previously did, but do not have adequate access to it.

3.2. Cognitive capability

Most 2LRs are assumed cognitively capable, possibly even above-average, insofar as the arduous migration process is only pursued by the most resilient (Fuller-Thomson & Kuh, Reference Fuller-Thomson and Kuh2014). Reflecting this assumption, bridging gaps in understanding and knowledge tends to orient towards improving linguistic effectiveness (e.g. via an interpreter, pictures) and building core social, cultural and procedural knowledge.

In contrast, PADs’ cognitive deficit is readily seen as the culprit when there is an information gap or communication breakdown, despite other potential explanations, including mishearing (see section 5). For instance, PADs such as Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2018), Swaffer (Reference Swaffer2016) and Taylor (Reference Taylor2007) complain of being judged incompetent when they just need an utterance repeated, or more time to reply. Even with a clear sense of what they want a message to achieve, problems with retrieval and memory can undermine its efficient production, leading to hesitations, malapropisms, false starts and tailing off (e.g. Ormrod, Reference Ormrod2019; Wray, Reference Wray2021).

Advice to supporters of PADs emphasises patience, letting PADs use their remaining capabilities fully, since ‘persons with dementia generally prefer to do what they can rather than have others do things for them’ (Sloane & Zimmerman, Reference Sloane, Zimmerman, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010, p. 193); and, within communication, ‘focusing on strengths’ (Allan & Killick, Reference Allan, Killick, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010, p. 220) by directing talk towards topics that the PAD has most to say about. No similar advice features in materials for 2LR supporters, since cognition is not a trait-based filter in their case.

3.3. Ability to understand the situation

Another trait-based filter of effective communication is imperfectly understanding the general situation within which message events are taking place. For PADs, the difficulty is in part created, and certainly exacerbated, by memory and processing impairments, while in 2LRs it is more about lack of general procedural and cultural knowledge in their unfamiliar location.

In the refugee context, the point of reference is trying to address a mismatch in necessary understanding, such that 2LRs’ perception of the situation must be brought into line with the actuality. Advice is focussed on the supporter anticipating discrepancies by developing ‘cultural competence’ in relation to the client’s perspective, with particular awareness of religious, dietary and social practices (Hannides et al., Reference Hannides, Bailey and Kaoukji2016; McGarry et al., Reference McGarry, Hannigan, De Almeida, Severoni, Puthoopparambil and MacFarlane2018, pp. 9–10). The Council of Europe (n.d., p. 2), in guidance on the use of pictures to assist with communication, recommends: ‘avoid using images which may offend or alienate refugees from other countries and with different cultural and religious backgrounds.’ Physiotherapists working with refugees are advised to:

o ask the client what their expectations are and how things were done in their country.

o acknowledge and respect differences that may exist between your beliefs, values and ways of thinking and that of your client. Talking about the differences may help give your client a framework for understanding your culture.

o make an effort: even showing a basic knowledge and an interest in their culture can be invaluable to clients trying to adjust to their new healthcare system.

o avoid generalisations about cultural groups: there is variety within each culture that’s influenced by urban or rural background, education, ethnicity, age, gender, social group, family and personality (Physiopedia, 2025).

Leaving aside situations where PADs are from another ethnic group or linguistic background,Footnote 2 any unsureness about the situation they are in and what is possible and appropriate will be attributed to their cognitive challenges (Wray, Reference Wray2020, p. 173). Often, PADs receive and understand information well at the time but cannot hold it in mind and recall it. Their mental map of a situation is thus in flux, making it more difficult for them to use pragmatic inference effectively and pinpoint appropriate goals. Whereas 2LR supporters can fairly easily gauge the nature and extent of a client’s limited understanding of a situation, PAD supporters are continually confronted by contradictions and can entertain thoughts like ‘how could you not know that?,’ particularly when the information has been presented many times before. As a result, advice to carers tends to be about having patience in the face of providing information that is, to their mind, unnecessary.

One way to reduce the generic impact of poor situational understanding in PADs is to direct them towards topics and contexts where they will feel more confident, such as talk about the here and now, and personal reminiscence. These activities can feel inauthentic, if the supporter has no real interest in hearing what the PAD says, though they can still be emotionally valuable to the client.

4. Internal event-based filters

Internal event-based filters are factors shaping the specific message. They include the client’s material and social intentions on that occasion and their understanding of the supporter’s capacity, at that moment, to act as an agent in achieving the goal(s), though there are other determinants as well (see Wray, Reference Wray2020, chapters 7 and 8). Three filters are identified in Fig. 1 and as they are fairly integrated, they can be addressed together.

Generally, 2LRs are depicted as pursuing tangible goals directly associated with survival and wellbeing, such as getting food, shelter and information. However, all message events have a social element and entail contextual constraints that must be navigated. For example, a 2LR needing to charge his phone might approach the aid worker whom he considers most likely to help him find a charger and electricity supply. The main social purpose of the interaction is to create a positive relationship with the supporter, though others could include being in a position to later help a friend with the same need. The balance of material and social goals, along with the client’s belief about the supporter’s willingness and capability to help, will determine whether the message is constructed as a demand or request, and so forth (Wray, Reference Wray2020). A PAD’s pursuit of material goals will be similar. She might be looking for help locating an item and approach a family member or a professional care worker who seems able to act as an agent for finding it. The PAD might also have a social purpose to the message such as getting reassurance. But even assuming that both client types engage in communication for similar reasons, it does not follow that supporters respond in the same way.

As we have already seen, while 2LRs’ goals are likely to reflect a recognised set of priorities directly linked to their situation, PADs’ expressed material goals may be deemed inappropriate and disregarded. Where the PAD’s belief about what the supporter can and should do for them contradicts the supporter’s view, the supporter can choose to adopt the client’s position. For example, suppose the PAD wants the supporter to help her go home to her parents, they might respond by confirming that this will be possible later (Kirtley & Williamson, Reference Kirtley and Williamson2016). Alternatively, supporters can attempt to orient PADs towards reality by denying the validity of the goal (see Wray, Reference Wray2020, pp. 225–226 for discussion of both options). Although PADs themselves urgently request that others take into account how skewed their perception of reality can be (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2018; Swaffer, Reference Swaffer2016; Taylor, Reference Taylor2007), their views differ regarding whether they should be repeatedly directed back to reality at any cost (Bute, Reference Bute2010; Day et al., Reference Day, James, Meyer and Lee2011).

5. External filters

Once the message is delivered, factors external to the speaker can filter its impact. For example, a PAD’s supporter might have a hearing impairment; an aid worker might not be, themselves, a competent user of the 2LR’s L2. The message might catch the supporter out, as contextually unpredicted, or the supporter might not be paying attention. Neither 2LRs nor PADs are in a strong position to fully accommodate such problems, so the onus falls on the supporter.

The main guidance is to avoid ill-advised second-guessing. In the 2LR context, specific packages of information can be prepared, on the basis of experience. With PADs, it is harder to predict the message, unless familiarity with the PAD highlights repeated themes. To maximise the likelihood of comprehension, supporters should sustain eye contact and remain committed to the interaction. However, for PADs, additional strategies include the supporter reflecting back what they just heard, including imitating intonation and tone (Caughey, Reference Caughey2018, p. 92), something that does not feature in advice to 2LR supporters and would probably be considered patronising.

Extraneous noise and distractions can impact on both parties’ comprehension of messages. The Alzheimer’s Society (2020, p. 16) advises turning off the TV and radio when interacting with PADs. Little is said about this issue in advice to aid workers, despite inevitably noisy environments, perhaps because both parties are equally able to recognise and seek to remedy the problem.

6. Event-based effects

Event-based effects are the immediate impacts of the message. Depending on how well the preceding filters have been navigated, so that the message is delivered in the optimal way for the present circumstances, the message will reach the supporter with a greater or lesser measure of fidelity. The supporter’s material response might be exactly what the client intended, might be faithful to a different interpretation, or might reflect understanding but non-compliance.

On the basis of these outcomes, the supporter will generate a view about how well the client has communicated that message and, by inference, can communicate more generally. Here, the situation for the two client types differs. Firstly, PADs are on a trajectory towards ever less capability, meaning that a hearer will be alert to messages that used to be easily conveyed not now being so. Thus, unsuccessful communication will likely add to the perception that things are getting worse, while successful communication is interpreted as luck or a rare and temporary reprieve, rather than recovery. In contrast, while interacting with 2LRs is challenging and tiring, successful communication can be interpreted as another step in the right direction, and unsuccessful communication as due to bad luck, tiredness or stress.

As we saw in section 2.2, 2LRs will generally be credited with an intention to create important meaning, and the advice to supporters places a strong emphasis on listening and on giving clients credibility and respect (see 2.4). The same level of credibility is not always enjoyed by PADs, and repeatedly low message impact will be cumulatively detrimental to the supporter’s expectations of future interaction (section 7).

7. Longer-term effects

Finally, the cumulative impact of communicative events determines the extent to which client and supporter feel empowered to communicate effectively, and how well communication is considered to be working. If these two effects are positive, they support the client’s life chances - for example, a 2LR navigating the obstacles to permanent legal residency or a PAD empowered to make daily decisions. The longer-term effects of messages will feed back into the status quo, with future interactions informed by previous experience. Both client and supporter are learning from each message event, and they adapt their strategies to achieve better future outcomes or to reduce the risk of future failure, such as by avoiding interaction.

I will focus on these strategies, since they aim to alter or preserve current longer-term effects. Even high-impact message events are likely to be perceived by clients and supporters as suboptimal, but strategies help determine what becomes anchored into the status quo as the benchmark for measuring future success. Two types of strategy emerge from the advice to supporters, the first relating to empowerment of the client and the second to self-protection of the supporter.

7.1. Empowerment strategies

Empowerment in the 2LR context is focussed, as we have seen, on the provision of interpreters and translations, as the core means for overcoming the communication gap, with little advice on maximising the effectiveness of interaction without interpreters, even though this must be a significant need. Policies to improve language class provision are also advocated, since immigrants, often with existing professional qualifications and experience, can more effectively integrate into the working population if they develop the necessary linguistic skills. Morrice et al. (Reference Morrice, Tip, Collyer and Brown2021, p. 683) note that, within the UK context, ‘there is no national ESOL strategy… and no joined-up, coherent approach to provision.’ They note that strategic improvements would include affordable, easily accessed classes, childcare provision, available when needed, properly advertised in the relevant communities, and available at different proficiency levels.

The scenario for empowerment is different with PADs, who are, in effect, being edged out of self-sufficiency over time, ideally while avoiding unnecessary jolts to their sense of autonomy. Communication problems, whereby PADs feel they have not been consulted, don’t understand the rationale for decisions made about them, or are not being heard, are a significant hindrance here (e.g. Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Scales, Lloyd, Schneider and Jones2015, pp. 261–262). In the light of the general downward trajectory of dementia, advice to supporters offers little on directly assisting PADs to regrow their linguistic abilities, but does offer ways to elicit positive emotions, which could benefit their communication, since the moment-by-moment severity of symptoms can be ameliorated by keeping the client calm and content (James, Reference James2008; McLean, Reference McLean2007).

7.2. Stress management strategies

Dementia carers (family and professional) and refugee support workers can experience huge stress under heavy workloads and compassion fatigue (Musa & Hamid, Reference Musa and Hamid2008), with onward impact on the quality of communication. Unless they have techniques for understanding their reactions (e.g. Bergström, Reference Bergström2025; McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Morris, Yates-Bolton and Charlesworth2019), they are likely to display reactive emotional responses. The source of supporters’ stress often lies in the clients’ own stress. For example, Plan International’s self-care manual for aid workers notes:

Survivors of war, natural disasters, forced displacement and other extreme situations are often more overwhelmed with past issues than focused on the present situation. Being in regular contact with this [sic] people makes us prone to the resurfacing of our own past issues because we are exposed to more triggers than in other professions (Novak, Reference Novak2020, p. 44).

Dementia carers can become severely stressed by clients’ ‘challenging behaviours,’ which arise from their own frustrations. One person living with dementia comments:

I know that when I am no longer able to speak, I could become violent quite easily. People make you do things that you don’t want to do, and you have no words for ‘No thank you.’ So all you can do is push them out of the way because they want to shower or dress you or give you food you don’t like (Bryden, Reference Bryden2005, p. 128).

It is easy for PAD carers to see such behaviours as ‘intentional attempts to annoy or challenge their level of patience’ (Savundranayagam et al., Reference Savundranayagam, Hummert and Montgomery2005, p. S54), something that, perhaps, is a less likely reaction with 2LRs. However, challenging behaviours are not the only trigger. I have pointed out in previous work on dementia that pragmatic dissonance (Wray, Reference Wray2016) and an excessive use of formulaic language (Wray, Reference Wray, B. and J2013) can also create severe stress and there is no reason why the same might not apply with 2LRs.

One type of advice to supporters in both contexts for avoiding or minimising stress is to ‘Discipline your mind to make a clear boundary between your personal and professional life’ (Novak, Reference Novak2020, p. 73). There are three purposes to this: to resist over-empathising with the client’s experiences, to avoid interpreting the client’s reactions as personal attacks, and to keep things in perspective, by recognising the nature of the support role. Gareth Owen, Humanitarian Director of Save the Children, comments:

I say to my staff, ‘On your worst day – on your worst day – think about the people in front of you. The people who have had to flee countries, who have had to endure all manner of hardship. You’re never having as bad a day as they’ve had. So, you’ve no right to give up on their behalf, and you just keep going’ (Imperial War Museums, 2025).

Novak’s advice, directed at aid workers, applies equally well to professional dementia carers, as a means of avoiding ‘compassion fatigue’ (Coetzee & Klopper, Reference Coetzee and Klopper2010; Ledoux, Reference Ledoux2015) and the traps of malignant social psychology (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997). However, it is considerably harder for family carers of PADs to implement, given their decades-long personal attachment to the PAD. Elsewhere, I have proposed that family carers can become caught in the ‘carer’s paradox,’ a dilemma regarding how closely to empathise with the PAD, which can trigger the counterproductive strategy of dyspathy (Wray, Reference Wray, B. and J2013, Reference Wray2020, pp. 217–218).

Without support, family PAD carers can attempt to protect themselves by shutting down emotionally. Research into ‘carer burden’ associated with challenging behaviours suggests that carers benefit from understanding the role of the illness in creating the situation (e.g. Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Selwood, Blanchard and Livingston2010, p. 595), such that learning positive strategies can be protective against depression and anger (Coon et al., Reference Coon, Thompson, Steffen, Sorocco and Gallagher-Thompson2003; Gallagher-Thompson et al., Reference Gallagher-Thompson, Coon, Salano, Ambler, Rabinowitz and Thompson2003). In turn, mentalisation is a pathway to identifying such strategies (Bergström, Reference Bergström2025; McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Morris, Yates-Bolton and Charlesworth2019).

8. Conclusions

What does all of this mean for those committed to improving the experience of people struggling to communicate? What can we learn from juxtaposing these two types of interactional experience? I think we need to get beyond asking what is different, to ask why it is different and, thus, how things might be beneficially changed. I will consider two key themes that emerge in the account above: capability (offering an opportunity to transfer learning from the 2LR context to PADs) and practical guidelines (transferable from the PAD context to 2LRs).

8.1. A positive stance towards capability

What is different? While 2LRs are viewed as inherently able, just lacking, currently, linguistic knowledge and necessary information, PADs are seen as fundamentally disabled: possessing but not using linguistic knowledge, having inadequate cognitive grasp of the situation, and often seeking information they don’t, or shouldn’t, need. As a result, the communication goals of 2LRs are treated as legitimate and credible, and the focus is on maximising opportunities for bridging the information gap, ideally via interpreters and translations. With PADs, the validity of goals is more readily questioned, and information provision is significantly downgraded in favour of, more nebulously, bridging the communication gap, often foregrounding reassurance and backgrounding the PAD’s actual intentions.

Why is it different? A cascade of implications arises from the perceived trajectory. While 2LRs are on a steep upward learning curve, PADs have a degenerative disease. Also, 2LRs are viewed as worth investing time and energy in, since they will increasingly use what they learn to help themselves and others. Language classes are a valuable investment for the longer-term benefit of both the clients and the host country. Over time, PADs are not going to improve, and so (it is assumed) there is no value in investing time and resources beyond managing the situation as it proceeds towards further decline.

How could there be less difference? We need to challenge the assumption that simply having a positive impact now isn’t enough. Should a fifty-year-old Olympian not still run, just because she knows she won’t win races anymore? If supporting 2LRs in achieving their goals leads to empowerment, how could we fail to recognise that not supporting PADs in achieving their goals leads to disempowerment? If we don’t pay attention to what will maximise PADs’ communicative effectiveness now, we are precipitating future problems. The speed of decline experienced by PADs is determined as much, if not more, by how others facilitate or impede the use of their existing capabilities, as by brain disease. PADs thrive on feeling they can still succeed in communication, that their views are still valued and that their problems can be tolerated and managed by others. The alternative is to undermine their confidence as they encounter their own and others’ frustration and become detached from contextual information that they could have easily received with a little help. Programmes targeting the greater empowerment of PADs can be highly successful, often by equipping supporters with better communication strategies (e.g. Meaningful Care Matters, Reference Meaningful Care Matters2020) and by helping PADs to find, and keep, their voice (e.g. Lipinska, Reference Lipinska2009; Sabat, Reference Sabat2001, Reference Sabat, Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2010). Such initiatives need to be promoted and valued as much as those for 2LRs.

8.2. Practical guidelines on maximising communication

It might seem contradictory, having just argued that communication support for 2LRs is more engaged and committed than for PADs, to now propose that dementia communication research and practice has a lot to offer the 2LR context. The difference lies in the level of support. While, as we saw in 8.1, there is more investment in the expectation of improvement over time in 2LRs, at the moment-by-moment level, it is dementia care that offers the nitty gritty information on how to maximise communicative outcomes.

What is different? I found no specific guidelines for 2LR supporters on how to communicate better, such as learning to anticipate which sorts of linguistic material will be most difficult to understand or generate, how to politely indicate not understanding, how to repeat information without being patronising, or how to handle a client’s frustration and distress at not being able to express themselves. All of these are core to how dementia carers are trained.

Why is it different? There is a focus in the 2LR context on cultural mediation, interpretation and translation (McGarry et al., Reference McGarry, Hannigan, De Almeida, Severoni, Puthoopparambil and MacFarlane2018, pp. 7–11), including how to deal with interpreters (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jaffe and Mutch2019). This preoccupation seems to create a blind spot when it comes to advising those who do not have an interpreter to hand, on maximising the effectiveness of challenging interactions where too little linguistic capability is shared. In the case of PADs, there are no interpreters, and this lays bare the need to articulate practical approaches to effective communication.

How could there be less difference? Not all of the guidance for dementia carers will be relevant to the 2LR context since PADs do know the language, even if they can’t fully operationalise it. Nevertheless, there are techniques for navigating the absence of a necessary word, coping with false starts, long silences and misunderstandings, and so forth, that could be tested and adapted for working with 2LRs. No doubt many 2LR supporters have already figured some of them out, but more readily available guidelines parallelling those found on dementia care websites would surely be helpful to those trying to find their way.

8.3. Iconoclasts forever

When my D. Phil supervisor told me I was an iconoclast, I had to look the word up. And I immediately wondered whether it was meant as a criticism or a compliment. Looking back further, to my school days, I think it was already baked into me to be disruptive in relation to ideas, to question ‘the way things are’ and come up with alternatives. If so, perhaps the iconoclastic approach won’t be as comfortable for everyone as it has been for me. All the same, I recommend giving it a go. It’s interesting, creative and often rather fun. To my mind, the ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions lie at the heart of effective, critically evaluative research. It is our job as researchers to challenge assumptions and test new ways of thinking about things. The silos of our disciplines challenge us to adopt such an approach: why do we, in our (sub)discipline, do things this way, or assume that position or approach is correct, when others in another (sub)discipline are doing something else? We are called upon to be not only interdisciplinary in our work but also cross-disciplinary. Breaching the walls of the silos is a good way to do that.

Alison Wray is Professor Emerita in Language and Communication at Cardiff University, Wales, UK. Her main research foci have been formulaic language, with particular attention to second language acquisition, and dementia communication. Her publications include Formulaic language and the lexicon (CUP, 2002), Formulaic language: Pushing the boundaries (OUP, 2008); The dynamics of dementia communication (OUP, 2020) and Why dementia makes communication difficult: A guide to better outcomes (Jessica Kingsley, 2021). She has appeared on Word of Mouth and Woman’s Hour on BBC Radio 4 and also on BBC World America and National Public Radio in the USA.