Introduction

Emerging postcolonial varieties of pluricentric languages are a fertile ground for the study of sociolinguistic variation. In the case of Mozambique, the lasting implantation of Portuguese was the result of its retention as the only official language and “symbol of national unity” of the newly independent state upon emancipation from Portugal in 1975 (Firmino, Reference Firmino2021:170), despite pervasive multilingualism and the presence of over 40 indigenous languages from the Bantu family, according to the Ethnologue (Eberhard, Simmons, & Fennig, Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2024). Although Portuguese is still predominantly acquired as a second language through the school system, the number of first-language speakers has been increasing, reaching 16.6% in 2017. The number of Portuguese speakers as either a first or second language duplicated from 1980 to 2017 (from 24.4% to 47.4%), indicating that Portuguese in Mozambique is gradually shifting from an initially nonnative variety to a nativized one, especially in urban settings (Chimbutane & Gonçalves, Reference Chimbutane and Gonçalves2023; Firmino, Reference Firmino and Reutner2024:810).

Mozambican Portuguese (MP) is currently undergoing a process of nativization, understood as the symbolic and structural transformation of Portuguese resulting from its adaptation to a new linguistic ecology (Firmino, Reference Firmino2021:164). This process is speeding up with the expansion of the school system and the democratization of Portuguese through massification of education and access to social media (Firmino, Reference Firmino2021:172). The linguistic outcomes of this process, in turn, are constrained by the contact ecology in which MP develops and by the nature of the linguistic input it is submitted to, as “the forms and structures provided by all the parties’ native tongues” create a unique pool of features from which the speakers subsequently make a selection (Schneider, Reference Schneider2003:241). The nativization process eventually reaches an end with the stabilization and spread of the indigenized features that have become socially acceptable productive forms in spite of normative pressure (Baxter, Reference Baxter, Álvarez López, Gonçalves, Ornelas and de Avelar2018:308; Firmino, Reference Firmino2021:165).

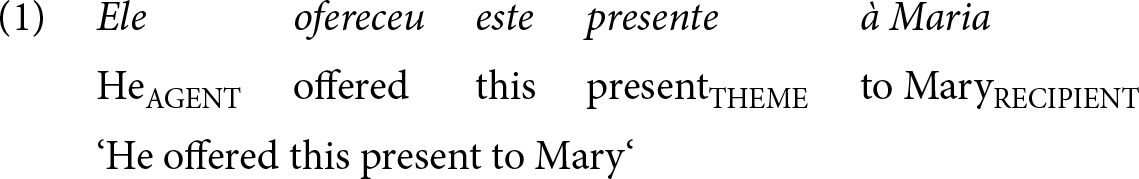

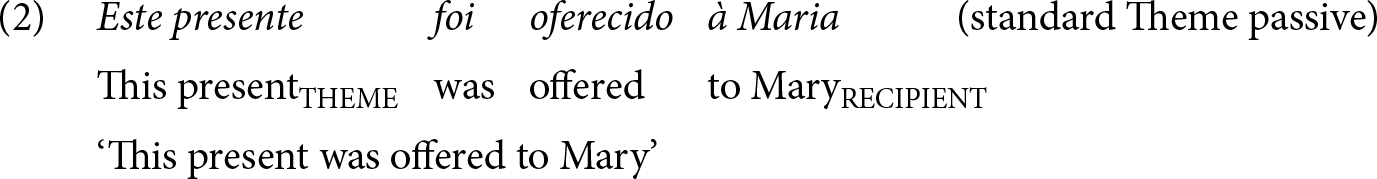

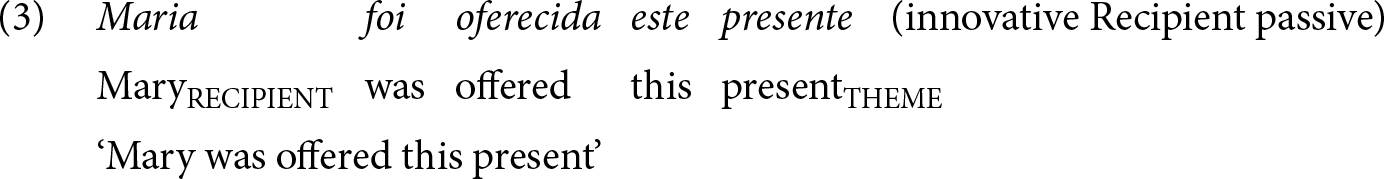

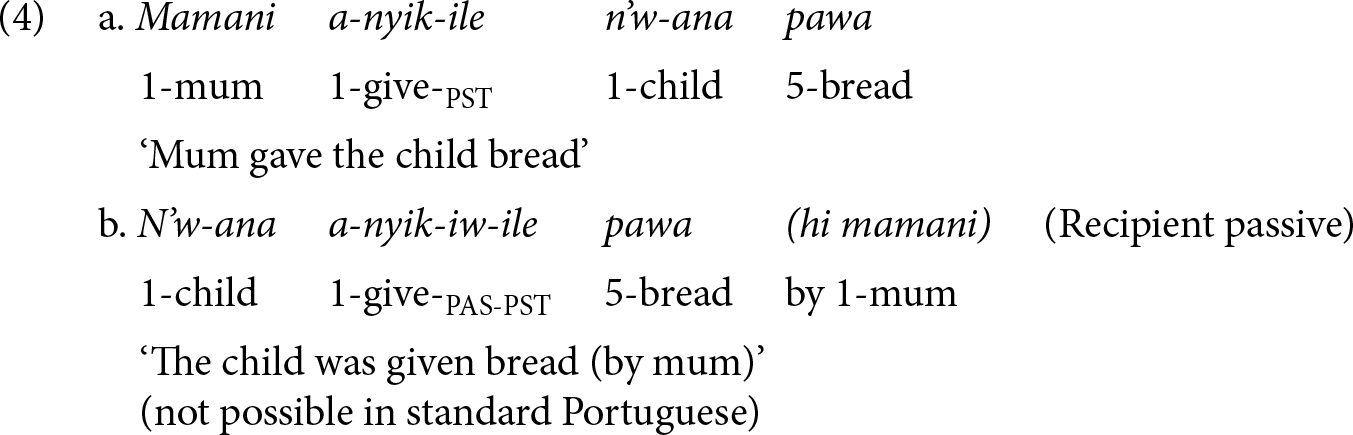

In MP, one such indigenized structural change is the development of a new syntactic pattern in ditransitive contexts: the Recipient passive (also referred to as “Dative passive”) construction. With verbs that take both a direct and indirect object (e.g., give or tell), corresponding to the semantic roles of theme and recipient, MP developed the possibility to passivize either of the objects,Footnote 1 with respective agreement on the main verb, in contrast to other varieties (e.g., European, Brazilian, Angolan, and Santomean Portuguese) which allow only passivization of the direct object (Gonçalves, Duarte, & Hagemeijer , Reference Gonçalves, Duarte and Hagemeijer2022), hence forming Theme passives. This means that, considering the situation depicted in (1), MP speakers can make a choice between (2) and (3) to express the fact that Mary received a present, while speakers of other varieties would exclusively resort to (2).

The structural possibility for the recipient participant to be promoted to subject position emerged in the first place out of structures that are grammatical in the local Bantu languages (Cumbane, Reference Cumbane2008:349; Firmino, Reference Firmino2021:182, Reference Firmino and Reutner2024:819; Ngunga, Reference Ngunga2012:16). In Changana for instance, a Bantu language spoken in Maputo, Recipient passives are the preferred grammatical alternative, as exemplified in (4), from Chimbutane (Reference Chimbutane2002:209). Yet it appears that language contact chiefly acted as a trigger for the subsequent constructionalization (Traugott & Trousdale, Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013:22) of the Recipient passive schema within the grammar network of MP. This innovative construction has developed alongside the normatively standard Theme passive construction, giving rise to a constructional alternation—that is, two different ways of syntactically encoding the same event (Perek, Reference Perek2015; Pijpops, Reference Pijpops2020). The event in question corresponds to a scene of transfer, broadly construed as a situation in which a theme comes into the dominion of a recipient, apprehended from its terminal point by virtue of the passive voice (Mevis & Soares da Silva, Reference Mevis and Soares da Silva2023).

While acknowledging the prime importance of language contact in the emergence of the new construction, this study seeks to apprehend the linguistic phenomenon from its other end, in terms of its alternation output in MP. In doing so, we aim to uncover the interplay between language contact and language-internal factors, showing how beyond contact-induced effects, variation is also conceptually and pragmatically motivated (Cameron & Schwenter, Reference Cameron, Schwenter, Bayley, Cameron and Lucas2013). More generally, we hope to shed some light on restructuration and indigenization processes that take place in postcolonial varieties of pluricentric languages, resulting in subtle region-specific grammatical variation and change.

Data and annotation

Dataset

To identify the factors driving the constructional alternation, we conducted a corpus-based study, resorting to the Web/Dialects section of the Corpus do Português (henceforth CP) (Davies, Reference Davies2016). The CP is composed of written material retrieved from blogs and websites from the period 2007–2013 and totals 27,877,440 words for the Mozambican subsection. It furthermore includes different genres (press and blog articles, forum posts, comments) and registers (from more to less formal) and is not restricted to the area of the capital city Maputo but extends to other regions of the country. The corpus, however, does not provide detailed sociolinguistic metadata about the informants’ first language, level of education, or age.

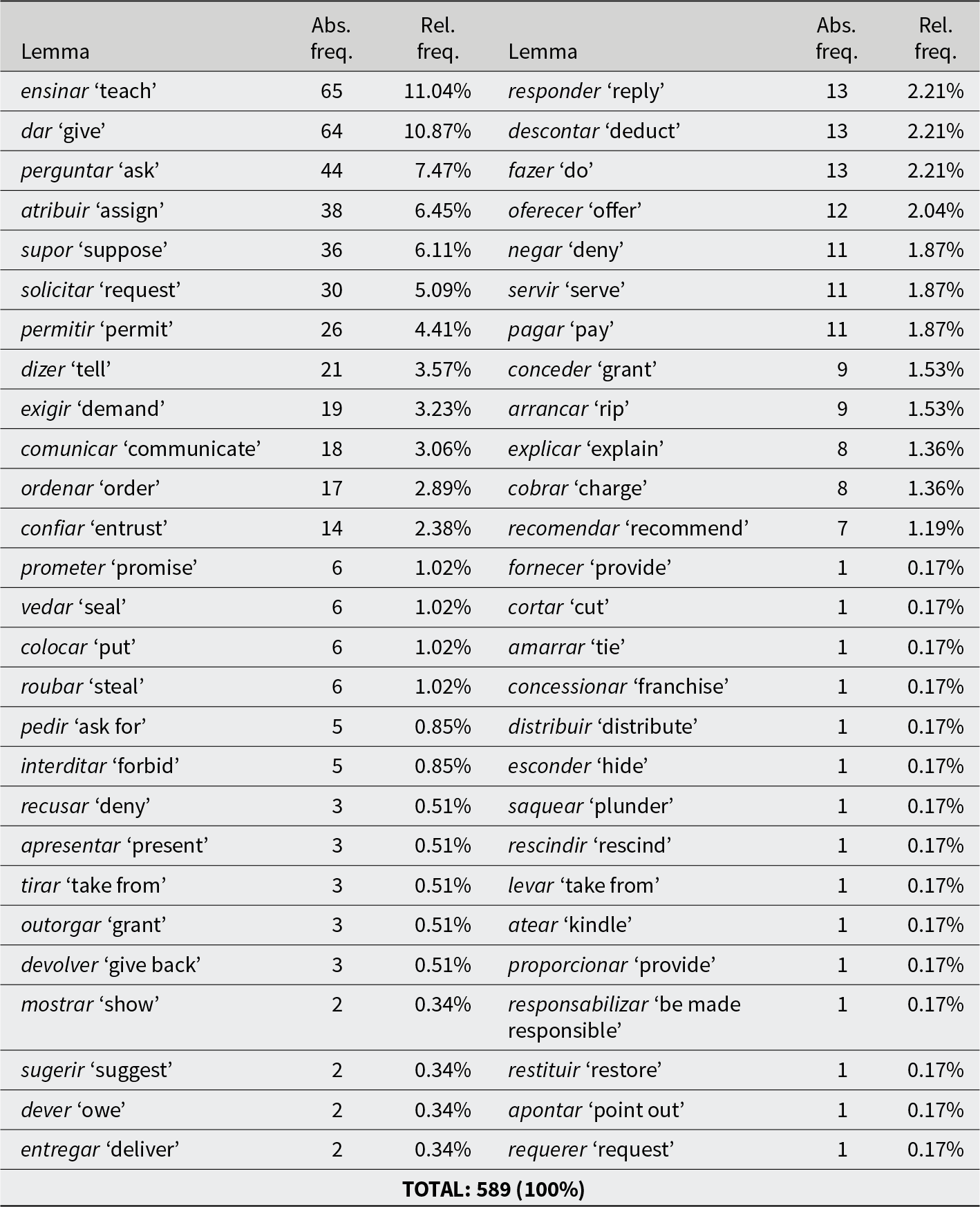

We manually extracted occurrences of both types of ditransitiveFootnote 2 passives. Attention was restricted to the variable context—that is, ditransitive contexts where both object arguments are conceptually present and equally available for topicalization in the passive. It is important to note that the more frequent strategy overall in the CP is the promotion of the theme as subject of the passive. This can be accounted for in terms of normativity, as written texts tend to follow reference norms more closely, but it could also be interpreted as an intrinsic feature of constructional alternations, which tend to have a more frequent variant, accounting for up to 80% of all occurrences (Divjak, Milin, & Medimorec, Reference Divjak, Milin and Medimorec2019:39). A first round of data extraction focused on the retrieval of Recipient passives, a step that was dependent upon the identification of the set of alternating ditransitive verbs, all related to the concept of transfer (Mevis & Soares da Silva, Reference Mevis and Soares da Silva2023:204–205). Overall, 589 Recipient passives were collected, with a total of 54 verbs, shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of Recipient passives for each lemma in MP

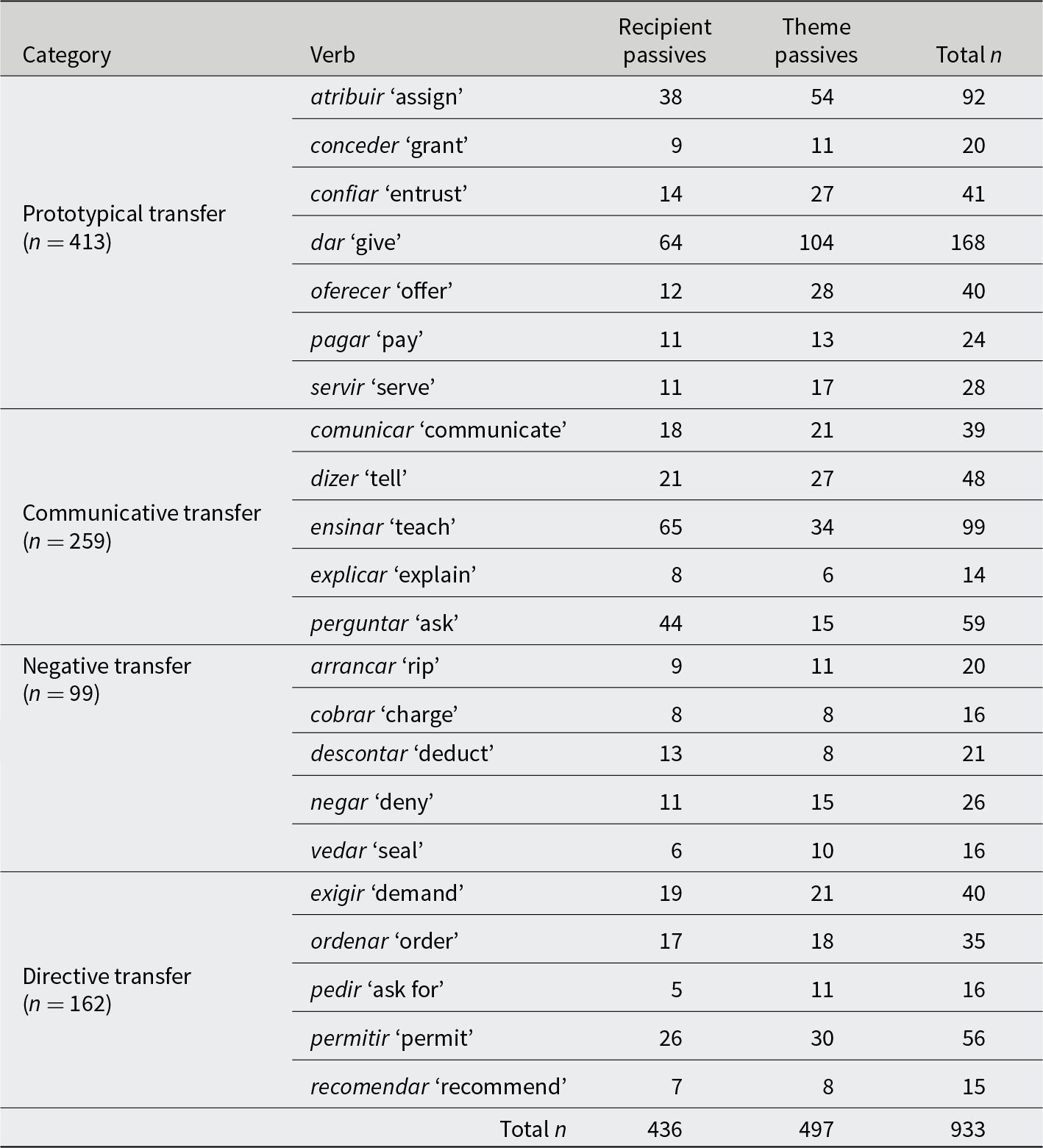

From the 54 alternating transfer verbs of Table 1, we selected 22, to keep the manual retrieval and annotation of data manageable. The sample consisted of the most frequent transfer verbs occurring in the Recipient passive construction and was further refined to obtain a balanced representation of four subcategories of transfer, as illustrated in Table 2. Thus, from the frequency-based selection, verbs that were not prototypical of the semantic category of transfer were removed (i.e., fazer ‘do,’ supor ‘suppose,’ solicitar ‘request,’ responder ‘answer’), while more representative verbs were included (pagar ‘pay,’ conceder ‘grant,’ cobrar ‘charge,’ pedir ‘ask’).Footnote 3

Table 2. Overall distribution of passive tokens by verb and variant (n = 933)

The second round of data extraction consisted in the retrieval of the Theme passive counterparts for the selected subset of transfer verbs. Since the objective of the study is to better define the specific semantic space that the Recipient passive is gradually carving for itself in MP alongside the existing Theme passive construction, we aimed for a balanced sample of the two types of passives, occurring in comparable, near-identical contexts (i.e., with overt recipient and theme participants). Recalling that Theme passives are the unmarked variant across varieties of Portuguese, they account for approximately 75% of all ditransitive passives in the corpus (although often with an unspecified or implicit recipient, hence not eligible as alternating variant).Footnote 4 Moreover, Theme passives are not unfrequent in formulaic or fixed expressions, especially with highly frequent verbs such as dar ‘give’ or atribuir ‘assign’ (e.g., seguimento foi dado a [lit. ‘follow-up was given to’]). Such instances were consequently removed from the dataset. Finally, while the focus here is on passive structures, it is worth mentioning the existence of the active third-person plural impersonal form as a third constructional alternative for the expression of transfer events (e.g., eu fui dito que versus foi-me dito que versus disseram-me que ‘I was told that’).

Annotation and predictions

The final dataset is made up of 933 tokens occurring with the preselected subset of 22 alternating ditransitive verbs, distributed between 436 Recipient passives and 497 Theme passives (Table 2). Tokens were manually annotated according to relevant factors at the following levels: (1) the grammatical construction, (2) the recipient participant, and (3) the theme participant. Table 3 shows an overview of the total number of tokens for every factor level, for 15 linguistic variables divided into semantic, discursive-pragmatic, and structural predictors, with the addition of 2 situational factors (Genre and Register). Some of these were adapted from the substantial body of literature on dative and passive constructions in English (Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, & Baayen, Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Krämer and Zwarts2007; Röthlisberger, Grafmiller, & Szmrecsanyi, Reference Röthlisberger, Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2017; Szmrecsanyi, Grafmiller, Heller, & Röthlisberger, Reference Szmrecsanyi, Grafmiller, Heller and Röthlisberger2016). The remainder of this section discusses the variables and their operationalization in dialogue with theoretical considerations and predictions. The examples provided are retrieved from the CP, shortened and adapted to Portuguese spelling rules where needed; those marked by the letter (a) are Recipient passives while (b) refers to Theme passives.

Table 3. Number of tokens per factor level (n = 933)

Semantic predictors

Type of transfer

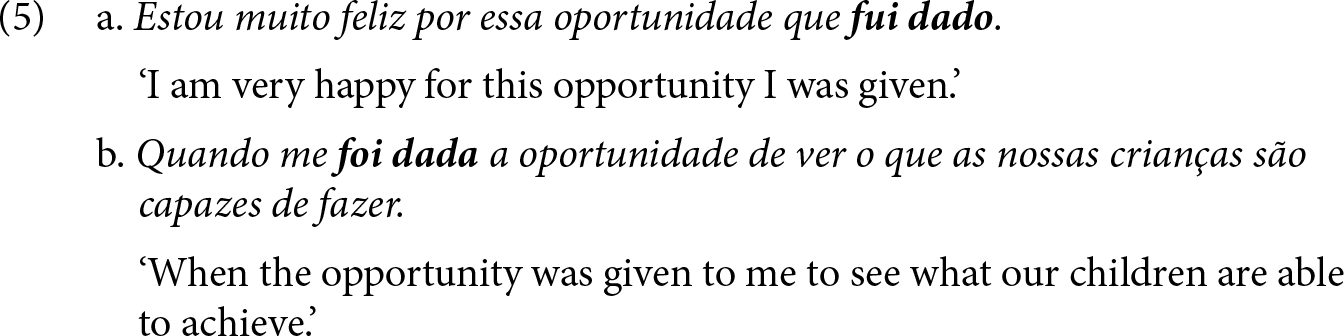

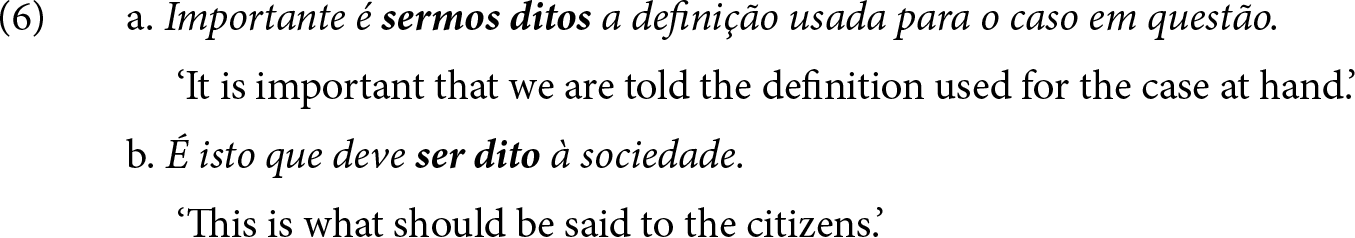

Given the polysemy of the transfer category, the data were annotated for four subtypes, namely prototypical (5), communicative (6), negative (7), and directive (8) transfer (Mevis & Soares da Silva, Reference Mevis and Soares da Silva2023:204–205).

Animacy of recipient

Animacy is probably among the best-known traditional predictors for the dative alternation. However, it can also prove misleading since there is a strong bias toward animate recipients in natural languages. Since our dataset contains a few inanimate recipients distributed across Recipient and Theme passives, its statistical impact might turn out not to be so strong after all. Animacy was coded according to a three-level distinction: animate (9), collective (10) (i.e., companies and organizations), and inanimate (11). By contrast, themes are almost exclusively inanimate and were therefore not annotated for animacy.

Concreteness of theme

As themes are overwhelmingly inanimate, they were in turn coded for whether they referred to a concrete (“material”) or abstract object. However, a problem quickly emerged in that this distinction is only tenable for prototypical and negative transfer, but not applicable to communicative or directive transfer, which as a rule take an abstract theme (a message, an order, a suggestion, etc.). This distinction furthermore fails to apply to another subset of our data (i.e., passives with a clausal theme).

Affectedness of recipient

Considering that the passive construction foregrounds a strongly affected participant, we decided to indicate whether the recipient was positively, negatively, or neutrally affected by the transfer event. This predictor, however, is strongly correlated with the verb and the type of transfer it is associated with. Yet, although affectedness is paramount to the passive, we expect the quality of affectedness to be of little relevance on the formation of Recipient passives, if at all.

Focus: dynamicity of the transfer event

A key notion in Cognitive Grammar is construal, referring to our “ability to conceive and portray the same situation in alternate ways” (Langacker, Reference Langacker2008:43)—that is, to view the same event under different perspectives. Alternating constructions can thus be viewed as two different ways of “construing” the same situation. On the one hand, the choice for a passive implies “a change in word order [that] is accompanied by a change of perspective” (Wanner, Reference Wanner2009:9); on the other hand, in the transfer event schema, “both the Mover [Theme] and the Recipient are central participants with legitimate claims to focal prominence” (Langacker, Reference Langacker2008:393). The passive moreover reinforces the possibility of alternate perspectives in making either of the objects entitled to subject position.

An act of transfer can thus be construed as more or less dynamic (Langacker, Reference Langacker1991:291–293). Recipient passives highlight the event from the recipient’s perspective and help convey a more static construal of the transfer event, one in which the theme is already found in the recipient’s possession, resulting in a less energetic conceptualization where the focus lays on the result of the transfer. By contrast, apprehending the scene from the theme moving into the dominion of the recipient favors a more dynamic reading of this same event, with a focus on the process of transfer.

In order to operationalize construal, we designed the two-level variable Focus. Although differences in construal are arguably attached to each passive construction, with Recipient passives inherently laying the focus on the result of the transfer, both Recipient and Theme passives were annotated for Focus as a way to test whether we could find an empirical basis for construal. Therefore, we defined a set of potentially co-occurring linguistic elements from the surrounding co-text that convey focus explicitly to guide and systematize the annotation (see Soares da Silva, Afonso, Palú, & Franco, Reference Soares da Silva, Afonso, Palú and Franco2021 for another example of operationalization of construal). Linguistic markers for Process include occurrence of the passive in a main clause, presence of dynamic adverbs (12), and presence of a para-clause of purpose (13). By contrast, a token was coded as Result based on occurrence of the passive in a subordinate clause, explicit outcome or reformulation sentence (14), or presence of an infinitive favoring a holistic construal (15). If we were not able to find any explicit marker for Result, the default encoding was Process (since it is also the default reading in the European reference norm).

Discursive-pragmatic predictors

Topicality

The relationship between information status and constituent order, with given referents preceding new ones, is particularly salient in the alternation at hand since passives are fundamentally pragmatically oriented constructions with a topicalization function (Wanner, Reference Wanner2009:38). Considering the topicalization function of the passive, we designed the three-level variable Topic (Topic-Recipient, Topic-Theme, None). This predictor refers to the previous segment of text and indicates whether either the recipient or the theme was the entity talked about in the immediately preceding context. When neither of the constituents had such prior pragmatic prominence, the predictor was set to None.

Accessibility of recipient and theme

To assess the discourse givenness of either of the objects and measure their degree of identifiability in the discourse space, we resorted to the binary predictor Accessibility, adapted from a study on Portuguese relative clauses (Soares da Silva & Afonso, Reference Soares da Silva and Afonso2022). Crucially, the choice of what to consider discursively accessible turns out to be different from previous work. In Bresnan and Ford (Reference Bresnan and Ford2010), for instance, a theme or recipient was tagged as “given” only when it was explicitly or situationally evoked. In all other cases, it was considered as “new.” For the Recipient/Theme passive alternation, the scope of given elements was broadened to include generic and so-called “frame inferable” referents (Michaelis & Hartwell, Reference Michaelis, Hartwell, Hedberg and Zacharski2007:39–40) to achieve a more accurate and comprehensive picture of the activation status of constituents.

For (explicitly or situationally) evoked referents, anaphoric (16) and deictic (17) markers were used; elements such as todos (‘all’), cada (‘each’), and uma pessoa (‘a person’) activate generic referents (18). Frame-inferable recipients/themes (i.e., identifiable by virtue of belonging to a currently active semantic frame) were identified based on lexical associations (19). Finally, noun phrases introduced by a presentational clause, or developing some previously mentioned referent further (e.g., partitive NP) were also coded as accessible (20). When no such marker was detectable, the referent was coded as not accessible (21). We expect more accessible constituents to precede less accessible ones, hence we would expect accessible recipients to increase the odds for a Recipient passive. Examples (16)–(21) are all Recipient passives.

Structural predictors

Theme form

Whereas recipients exclusively occur as nominal phrases (either pronominalized or not), themes may take various forms: a noun phrase (22), a prepositional phrase (23), an infinitive (24), or a finite clause (25). The theme can also be implicit (null object constructions). While previous research has largely ignored clausal themes (e.g., Röthlisberger et al., Reference Röthlisberger, Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2017), we included them in the analysis as we assume they might favor the formation of Recipient passives. It is important to note, however, that theme form may in some cases be highly dependent on the verb. Examples (22)–(25) are all Recipient passives.

Clause type

The type of clause in which a Recipient or Theme passive appears was coded according to a four-level distinction: main clause, subordinate clause, relative clause with recipient antecedent (26), and relative clause with theme antecedent (27).

Length

Length of constituents was operationalized as the log of the lengths (in number of words) of the recipient and theme. We then took the difference of these values (theme minus recipient) to obtain a positive or negative continuous variable. We would expect a negative value to correlate with Recipient passives; in other words, we would expect Recipient passives to occur when the recipient is shorter than the theme. The tendency to put longer constituents at the end of a sentence, known as the end-weight principle, emerged as one of the most influential factors when choosing a dative variant in English (Bresnan et al., Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Krämer and Zwarts2007). Matters might nevertheless be more complicated in this case since the relationship between order and constituent length is less straightforward in the passive, and subject-verb agreement facilitates a freer order of constituents in Portuguese.

Definiteness of recipient and theme

Both themes and recipients were coded for definiteness, which is often used as a proxy for discourse givenness. However, we suspect that this notion fails to properly account for the speaker’s choice between Recipient and Theme passives, as formally definite NPs do not account for the whole range of functionally identifiable NPs.Footnote 5 In line with previous studies (e.g., Bresnan et al., Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Krämer and Zwarts2007; Röthlisberger et al., Reference Röthlisberger, Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2017), it is expected that a definite recipient increases the likelihood of a Recipient passive, while the likelihood of a Theme passive should increase with a definite theme. Like for theme concreteness, the data could not be annotated for theme definiteness with clausal themes.

Person of recipient

In the literature on the English dative alternation, a weak effect of recipient person was found. Speakers favored the double-object construction in cases where the recipient was “local” (first or second person) (Röthlisberger et al., Reference Röthlisberger, Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2017:11). This binary distinction was reproduced in our annotation, and a similar slight effect in the choice between Recipient and Theme passives is expected: first- and second-person recipients, being more salient in discourse and more directly affected by the action, might more easily appear as subject of the passive.

Overtness of agent

We controlled for the overt presence of the Agent—that is, its expression by means of a by-phrase, headed by the preposition por in Portuguese (fui explicado por juristas [lit. ‘I was explained by lawyers’]). However, because most tokens in our dataset are short passives (849 against 84 with overt agent)—as are most passive sentences (Wanner, Reference Wanner2009:19)—we expect the expression of the agent to have no effect on the alternation.

External factors

Finally, two situational variables, Register and Genre, were also included in the analysis. Each token was coded as either formal or informal, and the different genres featuring in the corpus were divided into journalistic writings, blog articles, forum posts (including comments), administrative documents (including texts from official or governmental sites) and religious texts.

Analysis and results

We relied on conditional inference trees and random forests (Levshina, Reference Levshina2015; Tagliamonte & Baayen, Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012), two complementary statistical techniques based on recursive partitioning. These nonparametric tests are particularly suited to deal with unbalanced datasets, as they do not make any assumptions about the distribution of the data, and are especially useful “in situations when the sample size is small, but the number of predictors is large” (Levshina, Reference Levshina2015:292). Since we are essentially dealing with an alternation in the making in an exploratory fashion, with a rather diverse dataset,Footnote 6 these statistical tools fit our purposes well. All analyses were carried out using R (version 4.2.2, R Core Team, 2023) using the partykit package (version 1.2-23, Hothorn & Zeileis, Reference Hothorn and Zeileis2015).

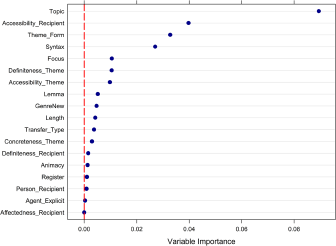

Random forest analysis

We started with a random forest analysis to obtain a ranking of the most significant predictors of the alternation, using the varimp() function. In addition to the 17 variables listed in Table 3, we included the factor Lemma in order to probe for possible lexical biases related to specific verbs. Highly correlated predictors can be explored together in the analysis (Tagliamonte & Baayen, Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012:169). This is for instance the case for the variables Affectedness and Transfer type, or Topic and Accessibility. The index of concordance (the C-value) for the random forest model with the full set of predictors reaches C = .95, indicating an outstanding fit. Figure 1 yields a picture of the relative importance of each predictor.

Figure 1. Random forest analysis with 18 predictors (C = .95).

The variables close to the dashed red line in Figure 1 do not exert any substantial influence on the choice between the two passive alternants. Among highly significant predictors, pragmatic factors feature prominently, with Topic being by far the most influential, followed by the discursive Accessibility of the recipient. These two predictors measure different yet intertwined notions. If a given referent is the topic of a piece of discourse, it will also be discursively accessible. The reverse, however, is not necessarily true. A referent can be discursively accessible (i.e., given, evoked, or frame inferable) without being the entity currently talked about. Pragmatic factors are closely followed by structural ones, namely Clause Type and Theme Form. Interestingly, the construal predictor, Focus, is found among the five most influential factors.

A closer look at the variables that showed no statistical significance also proves to be quite informative. At the very bottom, in line with the predictions made, the overt presence of the agent does not impact the choice between variants. The possibility of specifying the agent is rather a characteristic of passive structures. The same holds for Affectedness. Passives inherently give prominence to the affected participant, irrespective of whether the latter is positively or negatively affected. These two factors are therefore more appropriately described as intrinsic properties of passive constructions rather than determinants of the alternation. Somewhat surprisingly, the person/number of the recipient emerges as insignificant, which could be due to the type of data under study. As our sample of written texts is biased toward the third person (765 against 168), the difference between local and nonlocal recipients might be ironed out, remaining to be tested in spoken language.

Finally, a few traditional predictors were also encountered at the bottom of Figure 1. Animacy is one of the least powerful predictors, along with Definiteness of the recipient, which validates the view of definiteness as too restricted a measure for a proper account of the discourse givenness of a referent. Constituent Length apparently has some effect on the alternation, yet due to the heterogeneity of our dataset in terms of theme form and to the more flexible word order in Portuguese, it does not weigh much either. Turning to external factors, Register has little influence on the alternation, revealing that Recipient passives are not confined to informal discourse, while Genre has a stronger impact. Lastly, Transfer Type is a predictor of relatively low strength, which points toward an overall homogeneous behavior of the alternation across all four semantic subcategories.

Conditional inference trees

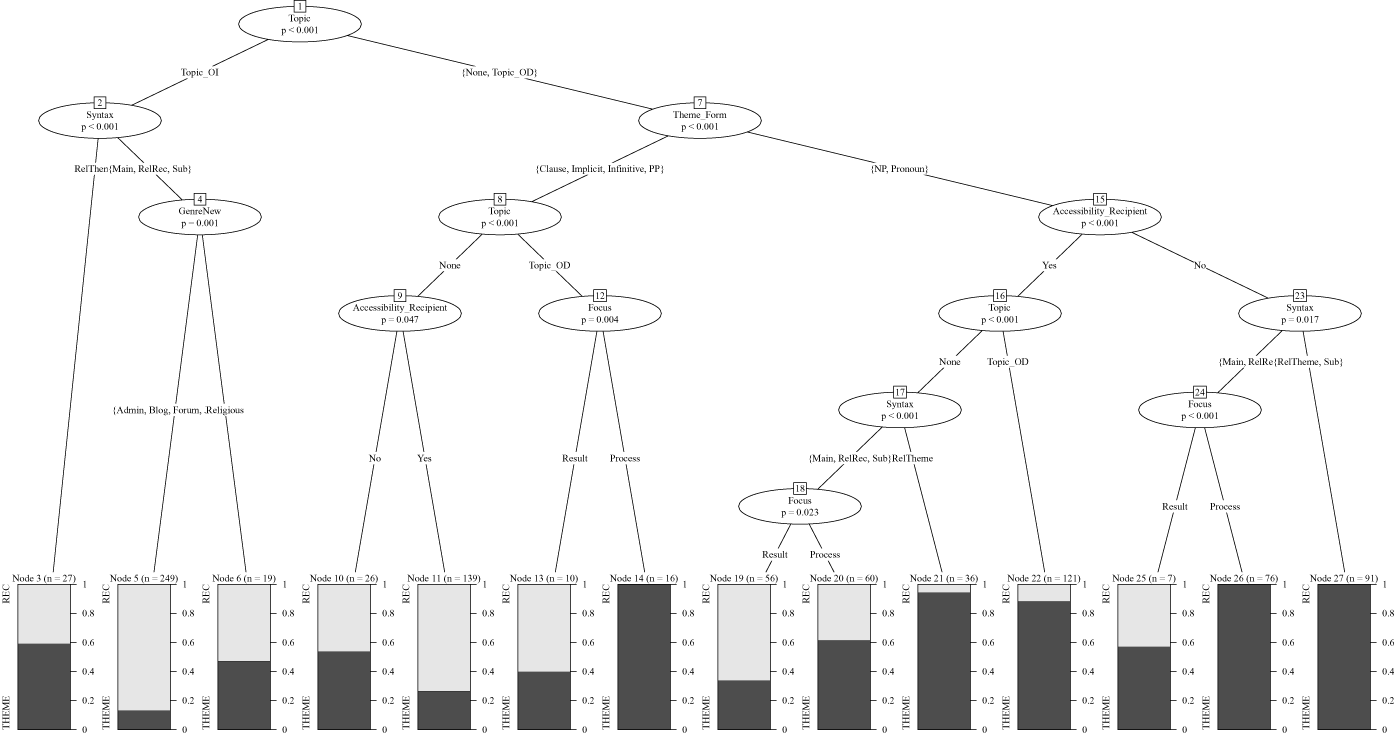

We then used conditional inference trees to help us identify which (combination of) factors are more likely to correlate with one or the other alternant. Figure 2 shows a conditional inference tree for the full dataset with the eight most significant predictors, excluding Lemma (see Figure 1). In keeping with the results from the random forest, Topic emerges as the most important variable overall, followed by Syntactic Structure, Genre, Theme Form, Accessibility of the Recipient, and Focus. The model obtained has a C-value of .89. The number of observations in each end node is shown in parentheses above the boxes (Levshina, Reference Levshina2015:294).

Figure 2. Conditional inference tree for the recipient/theme passive alternation in MP (8 predictors, C = .89).

It can be seen from Figure 2 that the proportion of Recipient passives (in white) is highest when the recipient referent is already the topic of the previous sentence or segment of text (at the left-hand side of the graph). By contrast, when the theme is the entity being talked about, we obtain a stronger, sometimes even categorical tendency toward Theme passives. In cases where the recipient is not the main discourse topic, the variable Topic intertwines with recipient Accessibility to determine the proportion of Recipient passives. A non-accessible recipient dramatically decreases the chance of forming a Recipient passive construction, while Theme passives appear to be less constrained in that respect. Discursive salience, especially with regard to the recipient referent, thus emerges as a decisive factor driving the alternation in MP.

Other factors subsequently enter into play. At the right-hand side of the tree, when neither constituent is topical (“None”) or when the theme gets most attention (see “Topic-OD”), both the discursive accessibility of the recipient and the construal of the event determine the distribution between both types of passives, along with structural factors. The split in node 7 reveals an important difference in the syntactic behavior of the theme, depending on whether it is a noun phrase or a verbal complement. The variable Theme Form was therefore recoded as a binary predictor (“Nominal/Verbal”).Footnote 7 An additional structural predictor that seems to tip the statistical balance is the syntactic structure of the passive constructions. When taking a closer look, however, we see that what really weighs in are the relative clauses, as a strong correlation can be observed between the antecedent of the relative clause and the subject of the passive construction, especially so with the theme (see nodes 3, 21, and 27). The use of relative clauses furthermore ties in with pragmatic factors since the antecedent is typically a referent about which a comment is made, thus very accessible by virtue of having been introduced in the immediately preceding context. The variable Syntax thus emerges as more deterministic than probabilistic, hence little informative. Lastly, construal emerges as a significant, though secondary predictor of the alternation. In line with our expectations, whenever the focus lies on the result (see nodes 12, 18, 24), a larger share of Recipient passives (in white) is found. This backs up the vision according to which Recipient passives convey a different, more result-oriented perspective on the transfer event, albeit in interaction with and secondary to pragmatic factors.

Conditional inference trees pruned

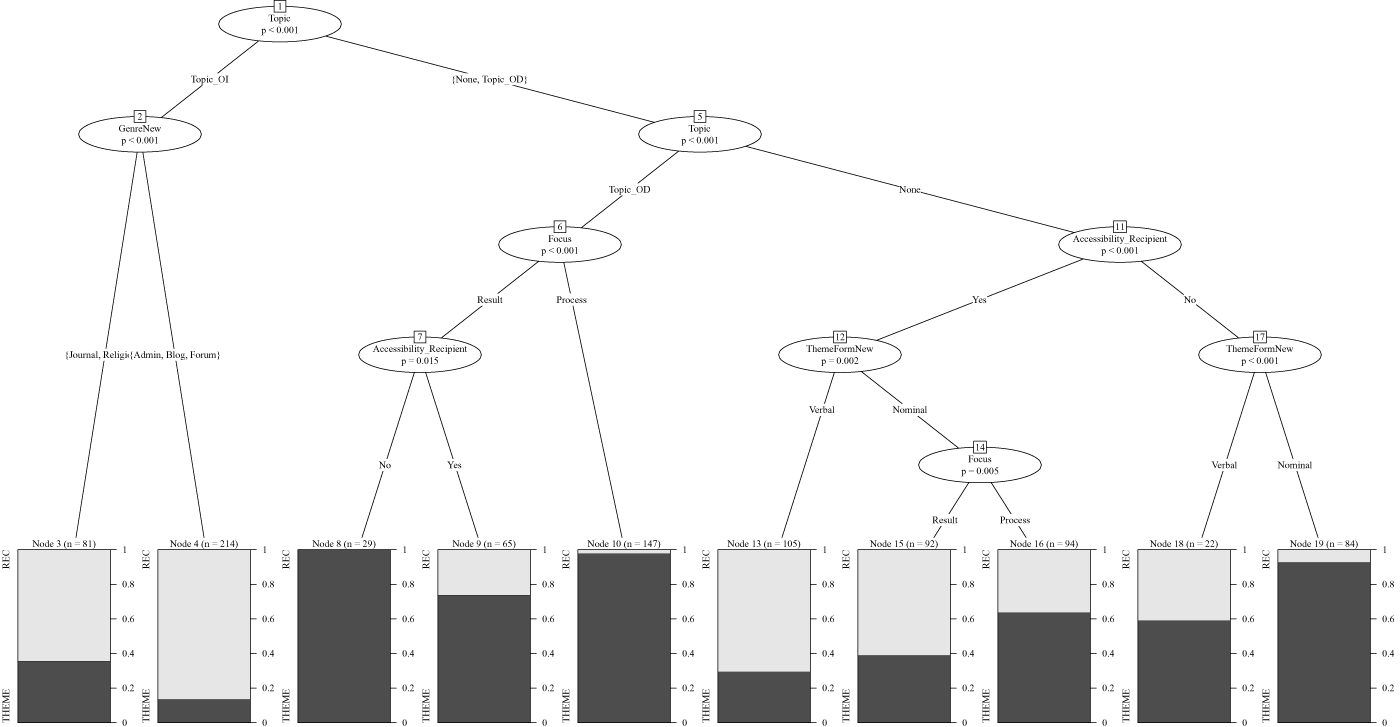

To achieve a clearer picture, two additional conditional inference trees were grown retaining only a subset of the statistically significant predictors. This decision came at the cost of a slight decrease in the C-value of the models, which nevertheless remained above the cutoff value of C ≥ .8, indicating good performance (Tagliamonte & Baayen, Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012:156), with C = .86 and C = .80, respectively. To obtain these pruned trees, we proceeded in a principled manner. Starting with the first model (see Figure 2), we excluded Syntax due to its bias toward relative clauses and substituted Theme Form with its recoded binary counterpart.

Unsurprisingly, Topic remains the determining predictor of the alternation as displayed in Figure 3. The interactions between Topic on the one hand and recipient Accessibility and Focus on the other are also sustained, with Recipient passives correlating with high degrees of recipient accessibility and a focus on the result of the transfer. When recipients are topical, and thus more likely to appear in Recipient passives, a mild effect of Genre can be noted. Recipient passives are slightly less likely in journalistic and religious discourse, in contrast with less stylistically constrained types of texts such as blogs and forums. Finally, the difference in behavior between nominal and verbal themes is found once more. In cases of no clearly defined topic (“None”), recipient Accessibility and Theme Form interact, with verbal themes more strongly associated with the Recipient passive construction. This is relatively unsurprising considering that in such cases the recipient emerges as the only available NP, making it a prime candidate for subjecthood.

Figure 3. Conditional inference tree for the recipient/theme passive alternation in MP (6 predictors, C = .86).

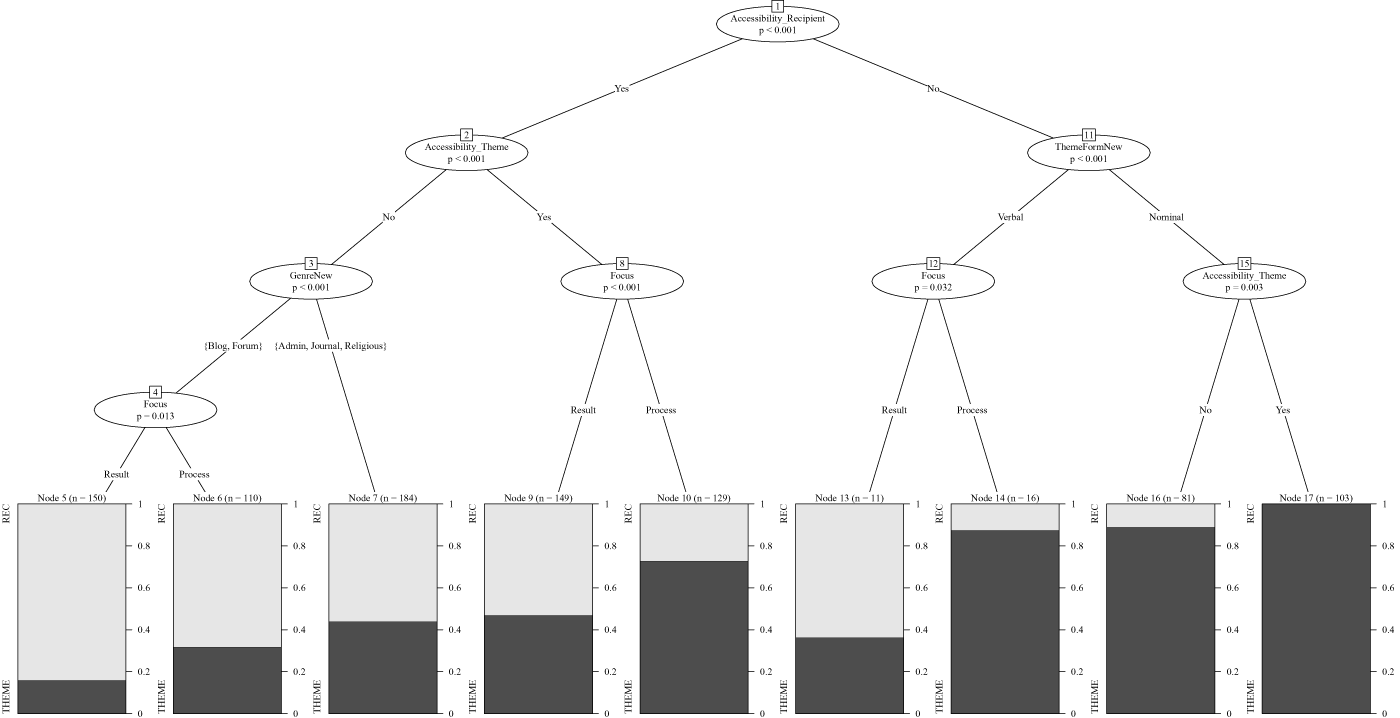

From this second 6-predictor model, we created a third tree, shown in Figure 4, by removing one further variable, Topic, on the basis of the interaction between Topic and Accessibility (identified in Figure 2), as well as on the fact that they measure related—albeit distinct—pragmatic notions. Although we took out the main predictor, we maintained both theme and recipient Accessibility to compensate for this “loss,” by virtue of their interaction. Overall, this is simply another configuration for testing how information structure influences the choice between Recipient and Theme passives, one in which the notion of discursive accessibility gains prominence.

Figure 4. Conditional inference tree for the recipient/theme passive alternation in MP (5 predictors, C = .80).

In this minimal model, what is lost in terms of C-value (C = .80) is gained in terms of clarity. Figure 4 displays a slope that illustrates how the proportion of Recipient passives (in white) gradually diminishes as the recipient loses its accessible status, while that of Theme passives (in black) steadily rises. Recipient Accessibility substitutes Topic as the most important predictor of the alternation, while theme Accessibility comes in to compensate for the absence of information about the topicality of the referents. The proportion of Theme passives increases when the theme is discursively accessible, even in cases of accessible recipient (node 2). When both constituents are simultaneously accessible, construal comes into play to introduce a further distinction (node 8). The variable Focus features once again as a secondary predictor, consistently displaying a larger proportion of Recipient passives in cases of result-oriented reading.

Figure 4 unveils two important interactions. First, theme Accessibility is subordinated to recipient Accessibility, with the latter determining more strongly the choice between the two types of passives; second, construal is consistently shown to interact with other predictors, being subordinated to pragmatic and, to some extent, structural factors. Another striking observation arising from Figure 4 is the absence of categorical contexts for Recipient passives, due perhaps to the construction’s relative recency and the normative pressure that the European standard still exerts in Mozambique.

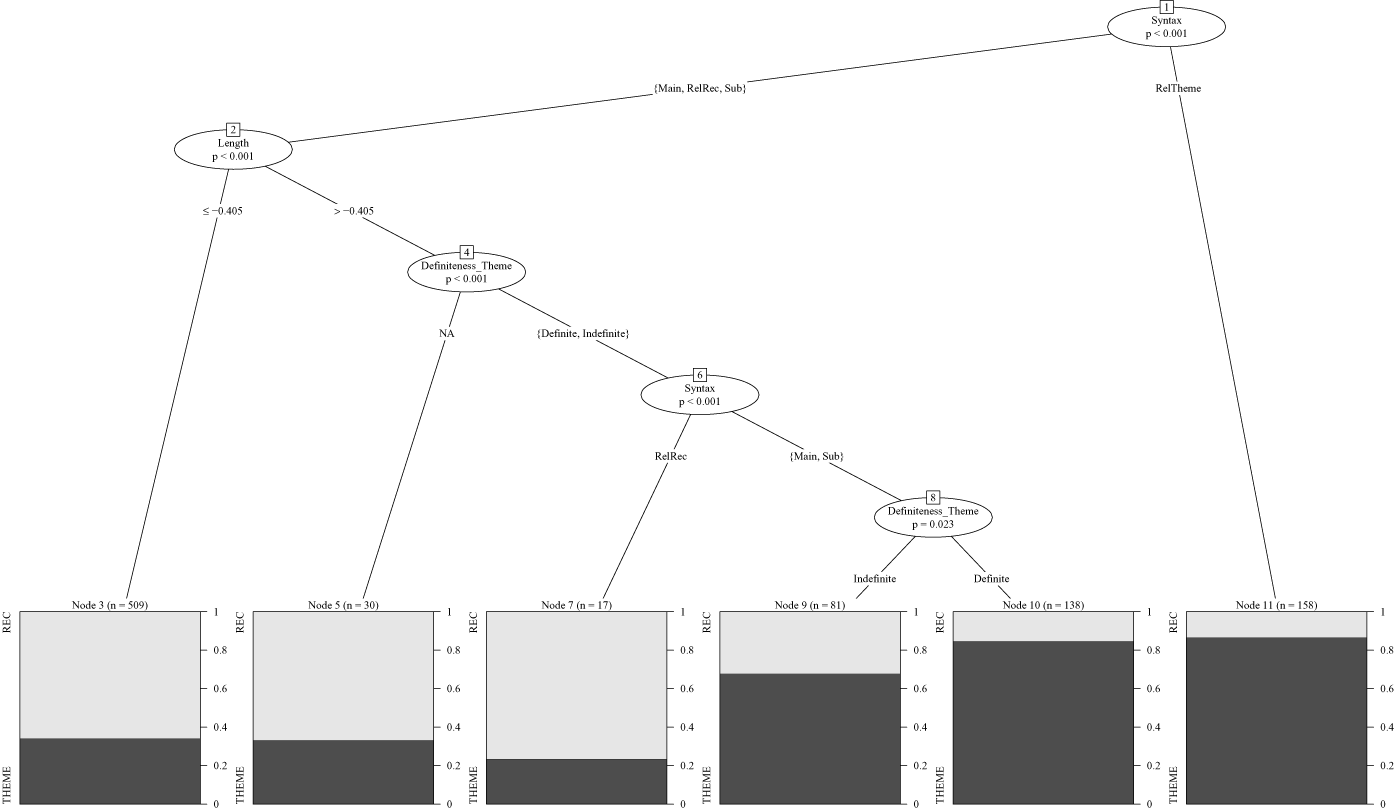

Finally, in Figure 5 we built one last tree grown on structural predictors only, that consisted of Syntax, binary Theme Form, Definiteness of both recipient and theme, Person of recipient, Overtness of the agent, and Length, achieving an index of concordance of C = .74. Its most valuable contribution is the illustration of the impact of Length, estimated at the cutoff value of −.405. According to our coding, cases in which the recipient is shorter than the theme should yield a negative value, which is expected to correlate with Recipient passives; by contrast, a positive value should correlate more strongly with Theme passives. Figure 5 shows that values lower than −.405 indeed display a greater tendency toward Recipient passives (in white), and that the proportion of Theme passives (in black) is larger for values above −.405. The first split for Definiteness of the theme (node 4) reflects the difference between nominal and clausal themes, since an “NA” value indicates a verbal complement that could not be annotated for definiteness. The second split (node 8) somehow corresponds to theme Accessibility, since a definite theme would be considered as discursively more accessible than an indefinite one.

Figure 5. Conditional inference tree for the recipient/theme passive alternation in MP (structural predictors only, C = .74).

Discussion

Meaningful alternation

The Recipient passive construction so typical of the variety of Portuguese spoken in Mozambique has not yet achieved the status of endogenous norm. Yet a dive into corpus data from the past two decades has revealed remarkable degrees of semantic coherence and syntactic productivity (Mevis & Soares da Silva, Reference Mevis and Soares da Silva2023), as well as responsiveness to a set of linguistic constraints that determine its actual use in discourse. MP has thus developed one more variant that qualifies as an “alternate way of saying the same thing” when it comes to a transfer event (Labov, Reference Labov1972:188). The models presented in the previous section unveiled structured variation between the innovative construction and its standard counterpart, with the alternation being primarily driven by pragmatic-discursive factors. The topicality and discursive accessibility of the recipient emerged as the most significant predictors and account for the largest share of Recipient passives in our dataset, which ties in with the topicalization function of the passive. Recipient passives therefore stand out as Topic-constructions, which are dependent to a greater extent than Theme passives upon the discursive salience of the recipient referent in the discourse space.

Beyond these important pragmatic considerations, the models highlighted other influencing variables and several interactions. On the one hand, the alternation between Theme and Recipient passives proved sensitive to alternate conceptualizations, depending on which participant receives focal prominence. The construal variable emerged as a secondary predictor, with Theme passives favoring a more dynamic reading and Recipient passives correlating with a less dynamic interpretation of the transfer event with a focus on its effective result. Structural factors, on the other hand, such as Syntactic Structure and Theme Form, scored high in our models, but hardly provided any satisfactory explanatory power. Using a particular clause structure for a given passive construction appeared rather as an effect of a combination of other factors, especially those related to information structure (e.g., a relative clause elaborates on a referent which has just been introduced and therefore tends to be discursively accessible).

A multilayered process

The models obtained in the statistical analysis appear to accurately generalize over several related Recipient passive micro-constructions (i.e., Recipient passives with different verbs and semantic classes of transfer, as well as with both nominal and clausal themes), which in turn seems to indicate that the Recipient passive has acquired a schematic meaning beyond the semantics of the individual verbs that participate in the construction. This process is referred to as schematization by Traugott and Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013:117) and typically correlates with increases in constructional productivity (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013:238) as the schema becomes a meaningful, readily available template. The emergence of this new constructional schema, however, did not automatically lead to a plain and homogeneous alternation evenly distributed across a well-defined set of verbs. Rather, several mechanisms, including reanalysis, analogy, and lexical preferences, also came into play and interfered in the constructionalization process, with direct consequences on the alternation.

To begin with, a similar alternation can occasionally be found in standard Portuguese. Even though the new variant is a typically Mozambican innovation, passives with a recipient-like subject are also possible in other varieties, including European Portuguese, with verbs like ensinar ‘teach’ or perguntar ‘ask.’ The use of the verb ensinar ‘teach’ in (28)—retrieved from the MP subsection of the CP—would easily be considered acceptable by speakers of European and Brazilian Portuguese, in contrast to the same use of the verb dizer ‘tell’ in (29), restricted to MP. Moreover, although a Recipient passive with an infinitival theme like (28) is more likely to be judged acceptable by European, Brazilian, and Mozambican speakers alike, the former will be more inclined to reject the same kind of passive with the same verb when it takes a nominal theme like (30), in contrast to MP speakers. This reveals how different varieties of a language have partially overlapping constructional networks and how some structural potentialities are explored further in one variety rather than in another.

Moreover, there are constructions in the network of Portuguese whose surface structure presents similarities with the Recipient passive schema and could thus have facilitated its emergence through reanalysis. This is the case of the semantic subcategory of “directive transfer,” which overlaps more generally with the category of directive verbs. In standard Portuguese, verbs such as autorizar ‘allow,’ proibir ‘forbid,’ and obrigar ‘oblige’ naturally take a recipient-like subject in the passive (e.g., fui autorizada ‘I was allowed’ or foram obrigados ‘they were forced’). MP speakers then seem to expand the category of directive verbs to include some verbs that from a normative point of view do not license a recipient subject, like exigir ‘demand’ or permitir ‘permit,’ or even the causatives fazer ‘do’ (31) or deixar ‘let’ (32).Footnote 8 Schematization and analogization therefore emerge as intertwined processes involved in the constructionalization of the Recipient passive in MP, and their interaction might even lead the construction to acquire new meanings over time.

Finally, lexical biases in alternations have consistently been uncovered by researchers (e.g., Perek, Reference Perek2015; Theijssen, ten Bosch, Boves, Cranen, & van Halteren, Reference Theijssen, ten Bosch, Boves, Cranen and van Halteren2013). The fact that the variable Lemma was ranked among the predictors of medium strength in the random forest analysis suggests the existence of such constructional preferences. Lexical biases may also account for the differences in the frequency with which a given verb features in either variant. Verbs like mostrar ‘show’ or distribuir ‘distribute,’ for example, are more strongly biased toward the theme participant—that is, they profile transfer events in which the theme is generally the most salient participant, which justifies their low frequency in the Recipient passive construction (see Table 1). By contrast, verbs like dar ‘give’ or oferecer ‘offer’ are more generic transfer verbs, hence underspecified in terms of inherent argumental focus. According to Perek (Reference Perek2015:158), the weight of some lexical biases constraining the use of a given verb in a construction may suggest verb-specific micro-constructions at lower levels of schematicity. All in all, the Recipient passive schema did not develop in isolation but within the inherited constructional network of Portuguese, where it necessarily enters in interaction with neighboring nodes at various levels of abstraction. This may result in local(ized) asymmetries in constructional patterns (that can be expressed inter alia in terms of frequency of occurrence).

Social and cognitive embedding of the alternation

Although the analysis focused on the linguistic envelope of variation, the emergent construction and resulting alternation are not only submitted to pressures from within the linguistic system, but also embedded within a specific speech community with its own intrinsic social processes and cultural values. The lasting implantation of Portuguese in a postcolonial, highly multilingual ecology characterized by Bantu language contact and second-language acquisition processes marked the beginning of a new evolutionary course for the regional variety of Mozambique, which currently finds itself in an advanced stage of nativization (Schneider, Reference Schneider2003).

The path of implementation of the Recipient passive construction within the MP speech community is an illustrative example of the interplay between internal and external factors in driving language variation and change, especially in emerging varieties. By revealing patterns of variation and showing how semantic and pragmatic considerations motivate the speaker’s choice for one or the other variant, the multifactorial analysis illustrates how the new passive construction, presumably originally modelled on the Bantu contact languagesFootnote 9 (Cumbane, Reference Cumbane2008; Firmino, Reference Firmino and Reutner2024; Ngunga, Reference Ngunga2012), started assuming autonomous functions within—and in line with—the grammar and structural possibilities of Portuguese. The interaction between the Portuguese linguistic system and Bantu substrate influence is moreover sustained by general cognitive principles. Specifically, Recipient passives commit to the “Easy First” cognitive principle—the general tendency for language users to place “easy” elements firstFootnote 10—functioning both as a motivation for the emergence of the new pattern as well as a cognitive routine likely to reinforce the (re)use of the construction over time (Röthlisberger et al., Reference Röthlisberger, Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2017:24–26).

The specific contact ecology in which MP develops thus constrains the path of language change. In the development of the Recipient passive construction, we find the articulation of the community-specific contact ecology and language-internal developments such as schematization, funneled by the language-specific structural constraints of Portuguese. Then, under pressure from the bulk of the population that is increasingly shifting to Portuguese, especially in urban settings (Baxter, Reference Baxter, Álvarez López, Gonçalves, Ornelas and de Avelar2018:293; Chimbutane & Gonçalves, Reference Chimbutane and Gonçalves2023), the innovative pattern is crystallizing, eventually ending up in the speech of the first generations of monolingual MP speakers who acquire a nativized variety despite lingering normative pressure.

Conclusions

This corpus-based study investigated the incipient Recipient/Theme passive alternation in MP, that is, the choice—exclusively available to speakers of that variety—of either the recipient or the theme as the subject of the passive clause in ditransitive contexts. It further evidenced how MP is undergoing nativization, understood as the process by which Portuguese is being shaped further through its implantation in a postcolonial and multilingual ecology. While the Recipient passive construction essentially emerged out of language contact, displaying structural convergence with the Bantu languages of Mozambique, the multifactorial statistical analysis based on random forests and conditional inference trees uncovered structured variation between the two constructional variants, responsive to a set of language-internal predictors, the most prominent being related to information structure (topicality and discursive accessibility of the participants) and to differences in construal (focus on either the result or the process of transfer). Recipient passives can be characterized as Topic-constructions that (1) more strongly depend on the discursive unfolding than Theme passives do, (2) allow putting emphasis on the affectedness of the recipient more straightforwardly, and (3) conceptualize the transfer event in terms of its end result.

The study of constructional alternations in the context of emerging varieties, and in particular of the Recipient/Theme passive alternation in MP, helped bring to light how a new constructional schema is gradually accommodated into the language system, with each variant taking on distinct functions. The multivariate quantitative methods developed in the field of alternation studies allowed to identify the most important predictors determining the choice between variants, while also revealing the gradience and complexity of the changes by uncovering interactions between predictors. The study of the Recipient/Theme passive alternation in MP ultimately illustrates how different varieties of the same language may have partly different networks of constructions, which in the long run can lead to increased regional variation of grammar. Echoing Schneider’s words (Reference Schneider2003:249), “this indigenization of linguistic structure […] gradually enriches the emerging new variety with additional structural possibilities, ultimately modifying parts of its grammatical makeup.” The typically Mozambican Recipient passive pattern thus emerges as a case of both meaningful variation with their Theme passive counterparts and language change in postcolonial varieties of pluricentric languages.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://osf.io/6pwzb/.

Acknowledgements

This study has been funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the doctoral grant with reference UI/BD/150881/2021 and the research project UIDB/00683/2020 (Centre for Philosophical and Humanistic Studies - Portuguese Catholic University.

Competing interests

The author declares none.