In memory of Phil Scott, 1947–2023

Philip Scott

I knew Phil for most of his career, from when he was a post-doctoral fellow at McGill in 1977, a colleague the following year at Dalhousie, and a friend ever since. His knowledge of the literature in category theory, logic, and computer science was phenomenal. He traveled a lot and spoke to many people. This way, he kept up to date on the latest developments, and each time he visited Halifax, he had some new topic he thought I should look at. This was good advice, which I wish I had been more diligent following up. We have lost a great ambassador for our subject as well as a friend. I dedicate this work to him.

Introduction

This is a sequel to Paré (Reference Paré2024). Here, we are interested in the structure of functors

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

(

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

(

![]() $\textbf {A}$

and

$\textbf {A}$

and

![]() $\textbf {B}$

small categories) generalizing the difference calculus for endofunctors of

$\textbf {B}$

small categories) generalizing the difference calculus for endofunctors of

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

. An important example is given by the generalized analytic functors of Fiore et al. (Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008). As in that work, profunctors are central. That is perhaps the main difference the present work has with Paré (Reference Paré2024). This is somewhat of a simplification like saying that multivariate calculus is just single variable calculus plus linear algebra. The added dimensions open up a whole array of possibilities.

$ \textbf {Set}$

. An important example is given by the generalized analytic functors of Fiore et al. (Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008). As in that work, profunctors are central. That is perhaps the main difference the present work has with Paré (Reference Paré2024). This is somewhat of a simplification like saying that multivariate calculus is just single variable calculus plus linear algebra. The added dimensions open up a whole array of possibilities.

The work here is a categorified version of the classical partial difference operators for real functions

a discrete version of partial derivatives. The analogy is quite fruitful.

As the paper is quite long, it may be helpful to point out the main results, namely the lax chain rule (Theorem4.2) and the Newton adjunction (Theorem5.1) together with the convergence theorem (Theorem5.2). These results are proper to the categorical setting and have no counterpart for real-valued functions. They could not be formulated without the pivotal definitions of the (discrete) Jacobian as a profunctor (Definition4.1) and soft analytic functor (Definition5.2).

Apart from the obvious (Fiore et al. Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008) and the references therein, the present work was strongly influenced by the work of the Calgary-Ottawa-Montreal consortium on tangent categories and Cartesian differential categories. Several talks in the ATCAT seminar by regulars Geoff Cruttwell and Marcello Lanfranchi as well as guest speakers, notably Robin Cockett and JS Lemay, helped form my ideas on the categorical theory of differentials. After completion of this work, the paper “Cartesian difference categories” by Alvarez-Picallo and Pacaud Lemay (Reference Alvarez-Picallo and Pacaud Lemay2021) came to my attention. This is clearly relevant as it deals with the categorical understanding of finite difference. What is less clear is precisely how they are related. Further work in this direction should prove fruitful.

Thanks to Nathanael Arkor, Andreas Blass, John Bourke, Aaron Fairbanks, Marcelo Fiore, Richard Garner, Theo Johnson-Freyd, Tom Leinster, Matías Menni, Deni Salja, and Peter Selinger for their insightful comments and interest. A special thanks to Peter Selinger for helping me prepare the final version in the MSC style.

1. Profunctors

Profunctors (a.k.a. bimodules, modules, and distributors) will be at the heart of this work. Widely viewed as categorified relations, for our purposes, they are better viewed as categorified matrices. They correspond to cocontinuous functors between functor categories. Such functors are considered to be linear. This section contains nothing new (except perhaps Definition1.2 and Proposition1.2). It is included for completeness and to set notation.

1.1 Definitions

We have opted, not without thought, for the following definition, which is the opposite of the majority view.

Definition 1.1.

(Lawvere, Bénabou) Let

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

and

$ \textbf {A}$

and

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

be small categories. A profunctor

$ \textbf {B}$

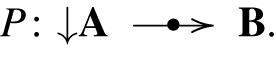

be small categories. A profunctor ![]() is a functor

is a functor

![]() $ P \colon \textbf {A}^{op} \times \textbf {B} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. A morphism of profunctors

$ P \colon \textbf {A}^{op} \times \textbf {B} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. A morphism of profunctors

![]() $ t \colon P \longrightarrow Q$

is a natural transformation.

$ t \colon P \longrightarrow Q$

is a natural transformation.

This gives the basic data for a bicategory,

![]() $ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

, of profunctors. Composition is given by “matrix multiplication,” which takes the form of a coend. For

$ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

, of profunctors. Composition is given by “matrix multiplication,” which takes the form of a coend. For ![]() and

and ![]() , the composite

, the composite

![]() $ Q \otimes P$

is defined by

$ Q \otimes P$

is defined by

The identity ![]() is the hom functor

is the hom functor

The reader is referred to the standard texts (see, e.g., Borceaux (Reference Borceaux1994b)) for a proof that we do get a bicategory.

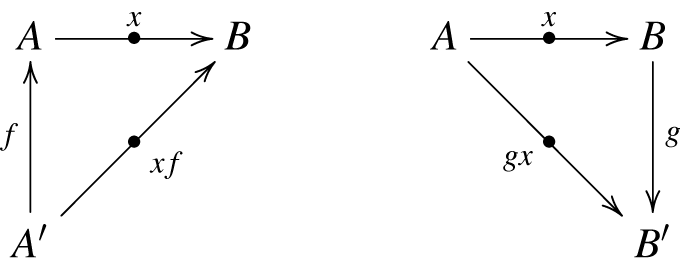

For explicit computations involving profunctors, the following notation is useful. An element

![]() $ x \in P (A, B)$

is denoted by a pointed arrow, sometimes called a heteromorphism,

$ x \in P (A, B)$

is denoted by a pointed arrow, sometimes called a heteromorphism, ![]()

if it’s necessary to keep track of the profunctor. The functoriality of

if it’s necessary to keep track of the profunctor. The functoriality of

![]() $ P$

manifests itself as a composition

$ P$

manifests itself as a composition

which is associative (left, right, and middle) and unitary.

It is in dealing with composition that this is most useful. An element of

![]() $ Q \otimes P (A, C)$

is an equivalence class of pairs

$ Q \otimes P (A, C)$

is an equivalence class of pairs

where the equivalence relation is generated by identifying  and

and  if we have

if we have

so they are equivalent iff there exists a path of pairs

We write the equivalence class  as

as

The equivalence relation is generated by

Every functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {A} \longrightarrow \textbf {B}$

induces two profunctors

$ F \colon \textbf {A} \longrightarrow \textbf {B}$

induces two profunctors

and

![]() $ F^*$

is right adjoint to

$ F^*$

is right adjoint to

![]() $ F_*$

in

$ F_*$

in

![]() $ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

.

$ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

.

1.2 Biclosedness

The bicategory

![]() $ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

is biclosed, that is,

$ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof}$

is biclosed, that is,

![]() $ \otimes$

admits right adjoints in each variable giving two hom profunctors

$ \otimes$

admits right adjoints in each variable giving two hom profunctors

![]() $ \oslash$

and

$ \oslash$

and ![]() characterized by natural bijections

characterized by natural bijections

for profunctors

We use Lambek’s notation for the internal homs. Inasmuch as

![]() $ \otimes$

is a product, the right adjoints are quotients of a sort.

$ \otimes$

is a product, the right adjoints are quotients of a sort.

An element of

![]() $ (Q\ \varnothing_{C}\ R) (A, B)$

is a

$ (Q\ \varnothing_{C}\ R) (A, B)$

is a

![]() $ \textbf {C}$

-natural transformation

$ \textbf {C}$

-natural transformation

and an element of

![]() $(R$

$(R$

![]()

![]() $_{\textbf {A}}\, P) (B, C)$

is an

$_{\textbf {A}}\, P) (B, C)$

is an

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

-natural transformation

$ \textbf {A}$

-natural transformation

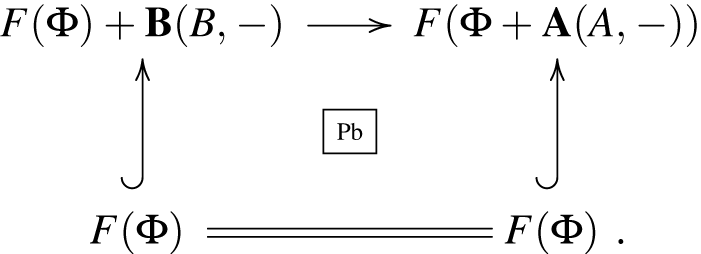

1.3 Cocontinuous functors

Our interest is in functors between functor categories and a profunctor will produce an adjoint pair of them. A profunctor: ![]() is a functor

is a functor

which we identify with a functor

![]() $ \Phi \colon \textbf {A} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. A profunctor

$ \Phi \colon \textbf {A} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. A profunctor ![]() will then produce, by composition, a functor

will then produce, by composition, a functor

with a right adjoint

It follows that

![]() $ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is cocontinuous and is considered to be the linear functor corresponding to the matrix

$ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is cocontinuous and is considered to be the linear functor corresponding to the matrix

![]() $ P$

.

$ P$

.

As is well known, we have

Proposition 1.1. The following categories are equivalent:

-

(1) Profunctors

-

(2) Cocontinuous functors

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

-

(3) Adjoint pairs

Given a cocontinuous functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, the corresponding profunctor

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, the corresponding profunctor ![]() is given by

is given by

Note that this doesn’t use cocontinuity of

![]() $ F$

, which leads to the following.

$ F$

, which leads to the following.

Definition 1.2.

The core of a functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is the profunctor defined by

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is the profunctor defined by

The functor

is the “linear core” of

![]() $ F$

.

$ F$

.

Proposition 1.2.

![]() $ Cor $

is right adjoint to the functor

$ Cor $

is right adjoint to the functor

![]() $ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof} (\textbf {A}, \textbf {B}) \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

which takes a profunctor

$ {\mathscr{P}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {rof} (\textbf {A}, \textbf {B}) \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

which takes a profunctor

![]() $ P$

to the (cocontinuous) functor

$ P$

to the (cocontinuous) functor

![]() $ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

.

$ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

.

Proof.

A profunctor ![]() can be viewed, by exponential adjointness, as a functor

can be viewed, by exponential adjointness, as a functor

![]() $ \textbf {A}^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

. Then,

$ \textbf {A}^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

. Then,

![]() $ \mbox{Cor}$

is just restriction along the Yoneda embedding

$ \mbox{Cor}$

is just restriction along the Yoneda embedding

and

![]() $ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is left Kan extension

$ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is left Kan extension

Thus for

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

,

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

,

![]() $ \mbox{Cor} (F) \otimes _A (\ \ )$

is the best approximation to

$ \mbox{Cor} (F) \otimes _A (\ \ )$

is the best approximation to

![]() $ F$

by a cocontinuous functor. As a matter of interest, the counit of the adjunction

$ F$

by a cocontinuous functor. As a matter of interest, the counit of the adjunction

is given as follows. An element of

![]() $ (\mbox{Cor} (F) \otimes \Phi )( B)$

is an equivalence class

$ (\mbox{Cor} (F) \otimes \Phi )( B)$

is an equivalence class

so

giving

Example 1.1.

If

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

and

$ \textbf {A}$

and

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

are discrete categories, i.e., sets

$ \textbf {B}$

are discrete categories, i.e., sets

![]() $ A$

and

$ A$

and

![]() $ B$

, then a profunctor

$ B$

, then a profunctor ![]() is just a

is just a

![]() $ A \times B$

-matrix of sets

$ A \times B$

-matrix of sets

![]() $ [P_{ab}]$

and a morphism of profunctors

$ [P_{ab}]$

and a morphism of profunctors

![]() $ P \longrightarrow P'$

a

$ P \longrightarrow P'$

a

![]() $ A \times B$

-matrix of functions. The identity

$ A \times B$

-matrix of functions. The identity

![]() $ {\textrm {Id}}_{\textbf {A}}$

is the matrix with

$ {\textrm {Id}}_{\textbf {A}}$

is the matrix with

![]() $ 1$

’s on the diagonal and

$ 1$

’s on the diagonal and

![]() $ 0$

elsewhere. If

$ 0$

elsewhere. If

![]() $ \textbf {C}$

is another discrete category and

$ \textbf {C}$

is another discrete category and ![]() a profunctor, then

a profunctor, then

![]() $ Q \otimes _{\textbf {B}} P$

is the

$ Q \otimes _{\textbf {B}} P$

is the

![]() $ B \times C$

-matrix

$ B \times C$

-matrix

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[ \sum _{b \in B} Q_{bc} \times P_{ab} \Bigg]_{\rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[ \sum _{b \in B} Q_{bc} \times P_{ab} \Bigg]_{\rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

If ![]() then

then

\begin{equation*} R \oslash _{\textbf {A}} P = \Bigg[\prod _{a \in A} R_{ac}^{P_{ab}} \Bigg] \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} R \oslash _{\textbf {A}} P = \Bigg[\prod _{a \in A} R_{ac}^{P_{ab}} \Bigg] \end{equation*}

and

A profunctor ![]() is a

is a

![]() $ 1 \times A$

matrix of sets, i.e., a vector

$ 1 \times A$

matrix of sets, i.e., a vector

![]() $[X_a]$

and

$[X_a]$

and

![]() $ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} X$

is the vector

$ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} X$

is the vector

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[ \sum _{a \in A} P_{ab} \times X_a\Bigg]_{b \rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[ \sum _{a \in A} P_{ab} \times X_a\Bigg]_{b \rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

On the other hand for ![]() a

a

![]() $ B$

-vector,

$ B$

-vector, ![]()

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[\prod _b Y_b^{P_{ab}} \Bigg]_{a\rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \Bigg[\prod _b Y_b^{P_{ab}} \Bigg]_{a\rlap {\,.}} \end{equation*}

So,

![]() $ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is a “linear” functor and

$ P \otimes _{\textbf {A}} (\ \ )$

is a “linear” functor and ![]() a “monomial” functor.

a “monomial” functor.

2. Tense Functors

In Paré (Reference Paré2024), we developed a difference calculus for taut endofunctors of

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

, functors preserving inverse images. However, the important example of multivariable analytic functors of Fiore et al. (Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008) is not taut. In fact, the linear functors

$ \textbf {Set}$

, functors preserving inverse images. However, the important example of multivariable analytic functors of Fiore et al. (Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008) is not taut. In fact, the linear functors

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

are not taut. They don’t even preserve monos. What we need are functors preserving complemented subobjects and their inverse images. Of course, in

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

are not taut. They don’t even preserve monos. What we need are functors preserving complemented subobjects and their inverse images. Of course, in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

, all subobjects are complemented so it would make no difference, so maybe that’s what taut should be after all. But the word “taut” is pretty well established, so we use “tense” instead.

$ \textbf {Set}$

, all subobjects are complemented so it would make no difference, so maybe that’s what taut should be after all. But the word “taut” is pretty well established, so we use “tense” instead.

2.1 Complemented subobjects

In this section, we collect some useful facts about complemented subobjects in functor categories

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, most of which are well known from topos theory. We first list some general topos theory results, which will be useful for us. Proofs can be found in any of the standard topos theory books (see Borceaux (Reference Borceaux1994a) for an easily accessible account).

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, most of which are well known from topos theory. We first list some general topos theory results, which will be useful for us. Proofs can be found in any of the standard topos theory books (see Borceaux (Reference Borceaux1994a) for an easily accessible account).

Definition 2.1.

A subobject

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented if there exists another subobject

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented if there exists another subobject

![]() $ \Psi ' \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \Phi$

for which the induced morphishm

$ \Psi ' \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \Phi$

for which the induced morphishm

![]() $ \Psi + \Psi ' \longrightarrow \Phi$

is invertible.

$ \Psi + \Psi ' \longrightarrow \Phi$

is invertible.

We will use the hooked arrow ![]() as a reminder that

as a reminder that

![]() $ \Psi$

is complemented,

$ \Psi$

is complemented,

Recall that every subobject

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

has a pseudo-complement

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

has a pseudo-complement

![]() $ \neg \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

, the largest subobject of

$ \neg \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

, the largest subobject of

![]() $ \Phi$

whose intersection with

$ \Phi$

whose intersection with

![]() $ \Psi$

is

$ \Psi$

is

![]() $ 0$

. It can be calculated as the pullback of the element

$ 0$

. It can be calculated as the pullback of the element

![]() $ \mbox{false} \colon 1 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Omega$

along the characteristic morphism of

$ \mbox{false} \colon 1 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Omega$

along the characteristic morphism of

![]() $ \Psi$

.

$ \Psi$

.

Proposition 2.1.

1. A subobject

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented iff its characteristic morphism factors through

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented iff its characteristic morphism factors through

![]() $ 1 + 1$

$ 1 + 1$

2. Complemented subobjects are closed under composition.

3. Complemented objects are stable under pullback: if ![]() is complemented and

is complemented and

![]() $ f \colon \Theta \longrightarrow \Phi$

, then

$ f \colon \Theta \longrightarrow \Phi$

, then

![]() $ \neg f^{-1} (\Psi ) = f^{-1} (\neg \Psi )$

, and we have isomorphisms

$ \neg f^{-1} (\Psi ) = f^{-1} (\neg \Psi )$

, and we have isomorphisms

4. If ![]() is complemented, its complement is

is complemented, its complement is

![]() $ \neg \Psi$

, so complements are unique when they exist.

$ \neg \Psi$

, so complements are unique when they exist.

5. Given an inverse image diagram (pullback)

![]() $ f$

restricts to

$ f$

restricts to

and the resulting square is also a pullback.

Complemented subobjects in functor categories

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

are better behaved than in general toposes. For example,

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

are better behaved than in general toposes. For example,

![]() $ \neg \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is always complemented for any subobject

$ \neg \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is always complemented for any subobject

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

.

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

.

Proposition 2.2.

For

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, we have

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, we have

(1)

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented iff for all

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

is complemented iff for all

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

and

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

and

![]() $ x \in \Phi A$

, we have

$ x \in \Phi A$

, we have

This is equivalent to saying that for all

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

is a pullback diagram. This in turn is equivalent to saying that for all

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

, every commutative square

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

, every commutative square

has a unique fill-in making the bottom triangle commute, i.e.,

![]() $ \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

is orthogonal to every representable transformation.

$ \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

is orthogonal to every representable transformation.

(2) For

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

,

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

,

and

![]() $ \neg \neg \Psi (A)$

consists of all elements,

$ \neg \neg \Psi (A)$

consists of all elements,

![]() $ x$

of

$ x$

of

![]() $ \Phi (A)$

connected to an element

$ \Phi (A)$

connected to an element

![]() $ x'$

of

$ x'$

of

![]() $ \Psi$

by a zigzag of elements of

$ \Psi$

by a zigzag of elements of

![]() $ \Phi$

$ \Phi$

(3) For any

![]() $ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

,

$ \Psi \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Phi$

,

![]() $ \neg \Psi$

is complemented and its complement is

$ \neg \Psi$

is complemented and its complement is

![]() $ \neg \neg \Psi$

, which is the smallest complemented subobject of

$ \neg \neg \Psi$

, which is the smallest complemented subobject of

![]() $ \Phi$

containing

$ \Phi$

containing

![]() $ \Psi$

.

$ \Psi$

.

Thus, the class of complemented subobjects consists of all transformations right orthogonal to the representable transformations

![]() $ \textbf {A} (f, -)$

, suggesting that it may be the

$ \textbf {A} (f, -)$

, suggesting that it may be the

![]() $ {\mathscr{M}}$

part of a factorization system on

$ {\mathscr{M}}$

part of a factorization system on

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, which is indeed the case.

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, which is indeed the case.

For

![]() $ \Phi$

in

$ \Phi$

in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, let

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

, let

![]() $ \sim$

be the equivalence relation on the set of all elements of

$ \sim$

be the equivalence relation on the set of all elements of

![]() $ \Phi$

generated by identifying

$ \Phi$

generated by identifying

![]() $ x \in \Phi A$

with

$ x \in \Phi A$

with

![]() $ \Phi f (x) \in \Phi A'$

for all

$ \Phi f (x) \in \Phi A'$

for all

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

. Thus,

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

. Thus,

![]() $ x \in \Phi A \sim x' \in \Phi A'$

if there exists a zigzag path as in (2) above. The set of equivalence classes is the set of components of

$ x \in \Phi A \sim x' \in \Phi A'$

if there exists a zigzag path as in (2) above. The set of equivalence classes is the set of components of

![]() $ \Phi$

,

$ \Phi$

,

![]() $ \pi _0 \Phi = \varinjlim _A \Phi A$

, and two elements are equivalent if and only if they are in the same component.

$ \pi _0 \Phi = \varinjlim _A \Phi A$

, and two elements are equivalent if and only if they are in the same component.

Definition 2.2.

A transformation

![]() $ t \colon \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

is

$ t \colon \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

is

![]() $ \pi _0$

-surjective if

$ \pi _0$

-surjective if

![]() $ \pi _0 t \colon \pi _0 \Psi \longrightarrow \pi _0 \Phi$

is surjective.

$ \pi _0 t \colon \pi _0 \Psi \longrightarrow \pi _0 \Phi$

is surjective.

Thus,

![]() $ t$

is

$ t$

is

![]() $ \pi _0$

-surjective iff every element of

$ \pi _0$

-surjective iff every element of

![]() $ \Phi$

is connected by a zigzag path to an element in the image of

$ \Phi$

is connected by a zigzag path to an element in the image of

![]() $ t$

.

$ t$

.

Proposition 2.3.

-

(1)

$ t , u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective} \Rightarrow t u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

.

$ t , u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective} \Rightarrow t u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

. -

(2)

$ t u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective} \Rightarrow t\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

.

$ t u\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective} \Rightarrow t\ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

. -

(3) Every

$ t$

factors uniquely up to a unique isomorphism as a

$ t$

factors uniquely up to a unique isomorphism as a

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

followed by a complemented monomorphism.

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

followed by a complemented monomorphism.

-

(4) The

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

transformations are left orthogonal to the complemented monos.

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

transformations are left orthogonal to the complemented monos.

Proof.

(1) and (2) are obvious from the definition. For (3), let

![]() $ t \colon \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

be any transformation. Let

$ t \colon \Psi \longrightarrow \Phi$

be any transformation. Let

![]() $ \Phi _0 A \subseteq \Phi A$

be the set of all

$ \Phi _0 A \subseteq \Phi A$

be the set of all

![]() $ x \in \Phi A$

connected to an element in the image of

$ x \in \Phi A$

connected to an element in the image of

![]() $ t$

.

$ t$

.

![]() $ \Phi _0$

is easily seen to be a complemented subfunctor of

$ \Phi _0$

is easily seen to be a complemented subfunctor of

![]() $ \Phi$

and is in fact the union of all of the components of

$ \Phi$

and is in fact the union of all of the components of

![]() $ \Phi$

that contain an element in the image of

$ \Phi$

that contain an element in the image of

![]() $ t$

. Then,

$ t$

. Then,

![]() $ t$

factors as

$ t$

factors as

and

![]() $ t_0$

is

$ t_0$

is

![]() $ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

by construction. This is our factorization. The uniqueness part will follow from (4).

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

by construction. This is our factorization. The uniqueness part will follow from (4).

Consider a commutative square in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

where

![]() $ t$

is

$ t$

is

![]() $ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

and

$ \pi _0\mbox{-surjective}$

and

![]() $ m$

is a complemented mono. Any

$ m$

is a complemented mono. Any

![]() $ x \in \Phi A$

is connected to some

$ x \in \Phi A$

is connected to some

![]() $ t (A') (y)$

for

$ t (A') (y)$

for

![]() $ y \in \Psi A'$

, so

$ y \in \Psi A'$

, so

![]() $ s (A) (x)$

is connected to

$ s (A) (x)$

is connected to

![]() $ s (A') t(A') (y) = m (A') r (A') (y)$

. As

$ s (A') t(A') (y) = m (A') r (A') (y)$

. As

![]() $ m$

is complemented, this implies that

$ m$

is complemented, this implies that

![]() $ s (A) (x)$

is in

$ s (A) (x)$

is in

![]() $ \Gamma (A)$

. This gives the diagonal fill-in

$ \Gamma (A)$

. This gives the diagonal fill-in

![]() $ \delta \colon \Phi \longrightarrow \Gamma$

such that

$ \delta \colon \Phi \longrightarrow \Gamma$

such that

![]() $ m\ \delta = s$

and

$ m\ \delta = s$

and

![]() $ \delta \ t = r$

.

$ \delta \ t = r$

.

![]() $ \delta$

is unique as

$ \delta$

is unique as

![]() $ m$

is monic.

$ m$

is monic.

These results tell us that we have a factorization system on

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

with

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

with

![]() $ {\mathscr{E}}$

the class of

$ {\mathscr{E}}$

the class of

![]() $ \pi _0$

-surjections and

$ \pi _0$

-surjections and

![]() $ {\mathscr{M}}$

the class of complemented monos. We call it the Boolean factorization. Note that the class of

$ {\mathscr{M}}$

the class of complemented monos. We call it the Boolean factorization. Note that the class of

![]() $ \pi _0$

-surjections is not stable under pullback however. Consider morphisms

$ \pi _0$

-surjections is not stable under pullback however. Consider morphisms

![]() $ f_i \colon A_0 \longrightarrow A_i , i = 1, 2$

in

$ f_i \colon A_0 \longrightarrow A_i , i = 1, 2$

in

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

and consider the pullback

$ \textbf {A}$

and consider the pullback

![]() $ \Sigma (A)$

consists of pairs of morphisms

$ \Sigma (A)$

consists of pairs of morphisms

![]() $ (g_1, g_2)$

such that

$ (g_1, g_2)$

such that

commutes, which well may be empty for all

![]() $ A$

. In that case, taking

$ A$

. In that case, taking

![]() $ \pi _0$

of the above pullback gives

$ \pi _0$

of the above pullback gives

showing that

![]() $ \textbf {A} (g_1, -)$

is

$ \textbf {A} (g_1, -)$

is

![]() $ \pi _0$

-surjective but its pullback is not.

$ \pi _0$

-surjective but its pullback is not.

Nevertheless, it will be useful for us in Section 5 where we will be particularly interested in transformations defined on sums of representables. We record here the following facts for use later.

A natural transformation

is determined by a function on the indices

![]() $ \alpha \colon J \longrightarrow I$

and a

$ \alpha \colon J \longrightarrow I$

and a

![]() $ J$

-family of functions

$ J$

-family of functions

![]() $ \langle\, f_j\rangle$

,

$ \langle\, f_j\rangle$

,

Write

![]() $ t = \displaystyle {\sum _\alpha } \textbf {A} (f_j, -)$

.

$ t = \displaystyle {\sum _\alpha } \textbf {A} (f_j, -)$

.

Proposition 2.4.

With

![]() $ t$

,

$ t$

,

![]() $ \alpha$

,

$ \alpha$

,

![]() $ f_i$

as above we have

$ f_i$

as above we have

-

(1)

$ t$

is a complemented mono if and only if

$ t$

is a complemented mono if and only if

$ \alpha$

is one-to-one and the

$ \alpha$

is one-to-one and the

$ f_j$

are isomorphims.

$ f_j$

are isomorphims.

-

(2)

$ t$

is

$ t$

is

$ \pi _0$

-surjective if and only if

$ \pi _0$

-surjective if and only if

$ \alpha$

is onto.

$ \alpha$

is onto.

-

(3) For a general

$ t$

given by

$ t$

given by

$ (\alpha , \langle\, f_j \rangle )$

, we get its Boolean factorization by factoring

$ (\alpha , \langle\, f_j \rangle )$

, we get its Boolean factorization by factoring

$ \alpha$

$ \alpha$

and then taking

\begin{equation*} \sum _{j \in J} \textbf {A}(C_j, -) \xrightarrow{\sum _\sigma \textbf {A} (f_k, -)} \sum _{k \in K} \textbf {A}(A_k, -) \xrightarrow{\sum _\mu \textbf {A}(1_{A_i}, -)} \sum _{i\in I} \textbf {A}, (A_i, -) \rlap {\ .} \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \sum _{j \in J} \textbf {A}(C_j, -) \xrightarrow{\sum _\sigma \textbf {A} (f_k, -)} \sum _{k \in K} \textbf {A}(A_k, -) \xrightarrow{\sum _\mu \textbf {A}(1_{A_i}, -)} \sum _{i\in I} \textbf {A}, (A_i, -) \rlap {\ .} \end{equation*}

It’s implicit in (1), but may be worth mentioning explicitly, that the complemented subobjects of

![]() $ \sum _{i \in I} \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

are the subsums, i.e., of the form

$ \sum _{i \in I} \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

are the subsums, i.e., of the form

![]() $ \sum _{k \in K} \textbf {A} (A_k, -)$

for

$ \sum _{k \in K} \textbf {A} (A_k, -)$

for

![]() $ K \subseteq I$

. It is also clear from the fact that each hom functor

$ K \subseteq I$

. It is also clear from the fact that each hom functor

![]() $ \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

is connected and complemented, so is one of the components of

$ \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

is connected and complemented, so is one of the components of

![]() $ \sum _{i \in I} \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

, and any complemented subfunctor is a union of components.

$ \sum _{i \in I} \textbf {A} (A_i, -)$

, and any complemented subfunctor is a union of components.

The following is well known (see Borceaux (Reference Borceaux1994a, Example 7.2.4)).

Proposition 2.5.

Every subobject in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is complemented (

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is complemented (

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is boolean) if and only if

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is boolean) if and only if

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

is a groupoid.

$ \textbf {A}$

is a groupoid.

We end this subsection with the following, which says that limits and confluent colimits of complemented subobjects are again complemented.

Proposition 2.6.

Let

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

be a diagram in

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

be a diagram in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

and

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

and

![]() $ \Gamma _0 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Gamma$

a subdiagram such that for every

$ \Gamma _0 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Gamma$

a subdiagram such that for every

![]() $ I$

,

$ I$

, ![]() is complemented, then

is complemented, then

(1)

![]() $ \varprojlim \Gamma _0 \longrightarrow \varprojlim \Gamma$

is a complemented subobject.

$ \varprojlim \Gamma _0 \longrightarrow \varprojlim \Gamma$

is a complemented subobject.

If

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is confluent we also have that

$ \textbf {I}$

is confluent we also have that

(2)

![]() $ \varinjlim \Gamma _0 \longrightarrow \varinjlim \Gamma$

is a complemented subobject.

$ \varinjlim \Gamma _0 \longrightarrow \varinjlim \Gamma$

is a complemented subobject.

Proof.

(1) ![]() is complemented iff for every

is complemented iff for every

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

,

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

,

is a pullback (Proposition 2.2 (1)). Limits of pullback diagrams are pullbacks, and the result follows.

(2) Recall from Paré (Reference Paré2024) that a category

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is confluent if any span can be completed to a commutative square and that confluent colimits commute with inverse image diagrams in

$ \textbf {I}$

is confluent if any span can be completed to a commutative square and that confluent colimits commute with inverse image diagrams in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

. This gives (2) immediately.

$ \textbf {Set}$

. This gives (2) immediately.

Corollary 2.1. The intersection of an arbitrary family of complemented subobjects in a presheaf category is again complemented. The same for union.

Proof.

Let ![]() be a family of complemented subobjects. Without loss of generality, we can assume that the total subobject

be a family of complemented subobjects. Without loss of generality, we can assume that the total subobject ![]() is contained in it so that the indexing poset

is contained in it so that the indexing poset

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is connected. Then, by the previous proposition

$ \textbf {I}$

is connected. Then, by the previous proposition

is a complemented mono. Because

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is connected the limit of the constant diagram

$ \textbf {I}$

is connected the limit of the constant diagram

![]() $ \varprojlim \Phi \cong \Phi$

, and the

$ \varprojlim \Phi \cong \Phi$

, and the

![]() $ \varprojlim \Psi _i$

is

$ \varprojlim \Psi _i$

is ![]() . The lattice of complemented subobjects of

. The lattice of complemented subobjects of

![]() $ \Phi$

is self-dual, which implies the result for unions.

$ \Phi$

is self-dual, which implies the result for unions.

Note that this result does not hold in an arbitrary Grothendieck topos.

2.2 Tense functors

As mentioned above, the functors

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ ) \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

arising from profunctors are not generally taut. In fact, they don’t even preserve monos in general. This may not be surprising if we consider the tensor product of modules, but one might have hoped that things would be better in the simpler

$ P \otimes (\ \ ) \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

arising from profunctors are not generally taut. In fact, they don’t even preserve monos in general. This may not be surprising if we consider the tensor product of modules, but one might have hoped that things would be better in the simpler

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

case.

$ \textbf {Set}$

case.

Example 2.1.

For any epimorphism

![]() $ e \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

in

$ e \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

in

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

, the natural transformation

$ \textbf {A}$

, the natural transformation

![]() $ \textbf {A} (e, -)\colon$

$ \textbf {A} (e, -)\colon$

![]() $ \textbf {A} (A', -)\longrightarrow \textbf {A} (A, -)$

is a monomorphism. If, for a profunctor

$ \textbf {A} (A', -)\longrightarrow \textbf {A} (A, -)$

is a monomorphism. If, for a profunctor

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ ) \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

were to preserve monos, we would need that

$ P \otimes (\ \ ) \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

were to preserve monos, we would need that

![]() $ P \otimes \textbf {A} (e, -)$

be a mono, but

$ P \otimes \textbf {A} (e, -)$

be a mono, but

![]() $ P \otimes \textbf {A} (e, -)$

is

$ P \otimes \textbf {A} (e, -)$

is

So

![]() $ P (e, B) \colon P (A', B) \longrightarrow P (A, B)$

would have to be one-to-one for all

$ P (e, B) \colon P (A', B) \longrightarrow P (A, B)$

would have to be one-to-one for all

![]() $ B$

, but that’s hardly always the case. The simplest example is when

$ B$

, but that’s hardly always the case. The simplest example is when

![]() $ \textbf {A} = \textbf {2}$

and

$ \textbf {A} = \textbf {2}$

and

![]() $ \textbf {B} = \textbf {1}$

. Then,

$ \textbf {B} = \textbf {1}$

. Then,

![]() $ P (e, 0)$

is an arbitrary function in

$ P (e, 0)$

is an arbitrary function in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

(

$ \textbf {Set}$

(

![]() $ e$

is the unique morphism

$ e$

is the unique morphism

![]() $ 0 \longrightarrow 1$

, which is of course epi).

$ 0 \longrightarrow 1$

, which is of course epi).

Now, the functors

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

are “linear functors,” and any theory of functorial differences that doesn’t apply to them is seriously flawed. This leads to the main definition of the section.

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

are “linear functors,” and any theory of functorial differences that doesn’t apply to them is seriously flawed. This leads to the main definition of the section.

Definition 2.3.

A functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense if it preserves

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense if it preserves

(1) complemented subobjects, and

(2) inverse images (pullbacks) of complemented subobjects.

A natural transformation is tense if the naturality squares corresponding to complemented subobjects are pullbacks.

Tense functors are closely related to, though incomparable with, taut functors. For this reason, we chose the word “tense” as an approximate synonym and homonym of “taut”.

Any functor preserving binary coproducts is tense, in particular

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, which preserves all colimits, is tense. So, Example2.1 shows that tense does not imply taut. On the other hand, the functor

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, which preserves all colimits, is tense. So, Example2.1 shows that tense does not imply taut. On the other hand, the functor

is taut (a right adjoint, so preserves all limits) but not tense: any proper subset

![]() $ A \subsetneq B$

gives a noncomplemented subobject

$ A \subsetneq B$

gives a noncomplemented subobject

The following is obvious but worth stating explicitly.

Proposition 2.7.

Identities are tense and compositions of tense functors are tense. Horizontal and vertical composition of tense natural transformations are again tense, giving a sub-2-category

![]() $ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

of the

$ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

of the

![]() $ 2$

-category

$ 2$

-category

![]() $ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}}$

of categories.

$ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}}$

of categories.

Proposition 2.8.

For any functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, we have

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, we have

-

(1) If

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is Boolean then tense implies taut

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is Boolean then tense implies taut

-

(2) If

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is Boolean then taut implies tense

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is Boolean then taut implies tense

-

(3) If

$ F$

is taut then it is tense if and only if

$ F$

is taut then it is tense if and only if

$ F$

applied to the first injection

$ F$

applied to the first injection

$ j \colon 1 \longrightarrow 1 + 1$

is complemented.

$ j \colon 1 \longrightarrow 1 + 1$

is complemented.

Proof.

(1) and (2) are obvious as is the “only if” part of (3), so assume

![]() $ F$

is taut and

$ F$

is taut and

![]() $ F(j)$

complemented. If

$ F(j)$

complemented. If ![]() is complemented, its characteristic morphism factors through

is complemented, its characteristic morphism factors through

![]() $ 1 + 1 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Omega$

giving a pullback

$ 1 + 1 \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \, \Omega$

giving a pullback

![]() $ F$

of which is also a pullback, so

$ F$

of which is also a pullback, so ![]() is complemented.

is complemented.

Evaluation functors preserve tenseness but, contrary to tautness, they don’t jointly create it. However, if we consider “evaluating at a morphism,” they do.

Proposition 2.9.

A functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense if and only if

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense if and only if

-

(1) for every

$ B$

in

$ B$

in

$ \textbf {B}$

,

$ \textbf {B}$

,

$ ev_B F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

is tense, and

$ ev_B F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

is tense, and

-

(2) for every

$ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

$ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

$ ev_g F \colon ev_B F \longrightarrow ev_{B'} F$

is a tense transformation.

$ ev_g F \colon ev_B F \longrightarrow ev_{B'} F$

is a tense transformation.

Furthermore, a natural transformation

![]() $ t \colon F \longrightarrow G$

is tense if and only if

$ t \colon F \longrightarrow G$

is tense if and only if

![]() $ ev_B t$

is tense for every

$ ev_B t$

is tense for every

![]() $ B$

.

$ B$

.

Proof.

![]() $ ev_B \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

preserves coproducts so is tense and thus

$ ev_B \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

preserves coproducts so is tense and thus

![]() $ ev_B F$

will be tense if

$ ev_B F$

will be tense if

![]() $ F$

is. To say that

$ F$

is. To say that

![]() $ ev_g \colon ev_B \longrightarrow ev_{B'}$

is tense is to say that for every complemented subobject

$ ev_g \colon ev_B \longrightarrow ev_{B'}$

is tense is to say that for every complemented subobject ![]() , we have a pullback

, we have a pullback

which Proposition2.2 (1) says is indeed the case. So,

![]() $ ev_g F$

will be tense when

$ ev_g F$

will be tense when

![]() $ F$

is.

$ F$

is.

In fact, this says that being complemented is equivalent to every

![]() $ g$

giving a pullback as above. So our condition (2) implies that

$ g$

giving a pullback as above. So our condition (2) implies that

![]() $ F$

preserves complemented subobjects. And the evaluation functors

$ F$

preserves complemented subobjects. And the evaluation functors

![]() $ ev_B$

jointly create pullbacks. So (1) and (2) together imply that

$ ev_B$

jointly create pullbacks. So (1) and (2) together imply that

![]() $ F$

is tense.

$ F$

is tense.

The second part is clear as the functors

![]() $ ev_B$

jointly create pullbacks and tenseness of natural transformations is a purely pullback condition.

$ ev_B$

jointly create pullbacks and tenseness of natural transformations is a purely pullback condition.

Corollary 2.2. The following are equivalent.

-

(1)

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense.

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is tense.

-

(2) (a) For every complemented subobject

and every morphism

and every morphism

$ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

$ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

is a pullback diagram, and

-

(b) For every pullback diagram of complemented subobjects

and every

$ B$

in

$ B$

in

$ \textbf {B}$

,

$ \textbf {B}$

,

is a pullback.

-

(3) For every pullback diagram of complemented subobjects

and every

$g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

$g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

,

is a pullback.

Furthermore,

![]() $ t \colon F \longrightarrow \ G$

is tense if and only if for every complemented subobject

$ t \colon F \longrightarrow \ G$

is tense if and only if for every complemented subobject ![]() and every object

and every object

![]() $ B$

in

$ B$

in

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

,

$ \textbf {B}$

,

is a pullback.

Proof. That (1) is equivalent to (2) follows immediately from the previous proposition, the definition of tense, and Proposition2.2, as does the statement about tense transformations.

(2) (a) and (b) are special cases of (3) and the pullback in (3) can be factored into two pullbacks of type (a) and (b).

2.3 Limits and colimits of tense functors

Proposition 2.10.

Let

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

be a diagram such that for every

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

be a diagram such that for every

![]() $ I$

in

$ I$

in

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

,

$ \textbf {I}$

,

![]() $ \Gamma (I)$

is tense. Then,

$ \Gamma (I)$

is tense. Then,

(1)

![]() $ \varprojlim \Gamma$

is tense.

$ \varprojlim \Gamma$

is tense.

If

![]() $ t \colon \Gamma \longrightarrow \Theta$

is a natural transformation such that for every

$ t \colon \Gamma \longrightarrow \Theta$

is a natural transformation such that for every

![]() $ I$

in

$ I$

in

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

,

$ \textbf {I}$

,

![]() $ t I \colon \Gamma I \longrightarrow \Theta I$

is tense, then

$ t I \colon \Gamma I \longrightarrow \Theta I$

is tense, then

(2) the induced transformation

is tense.

If

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is confluent, then under the same conditions as above we have

$ \textbf {I}$

is confluent, then under the same conditions as above we have

(3)

![]() $ \varinjlim \Gamma$

is tense, and

$ \varinjlim \Gamma$

is tense, and

(4)

![]() $ \varinjlim t$

is tense.

$ \varinjlim t$

is tense.

Proof. (1) and (3). The preservation of complemented subobjects follows immediately from Proposition2.6. The preservation of pullbacks of complemented subobjects follows from the fact that limits commute with limits for (1) and that confluent colimits commute with inverse images for (3).

Tenseness of natural transformations is also a pullback condition, so (2) and (4) follow for the same reasons.

This is a result about limits and colimits of tense functors taken in

![]() $ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

. It is not assumed that the transition transformations

$ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

. It is not assumed that the transition transformations

![]() $ \Gamma (I) \longrightarrow \Gamma (J)$

are tense, and unsurprisingly, we don’t get a universal property for tense cones or cocones. Given a tense cone or cocone, the uniquely induced natural transformation is tense but this doesn’t establish the required bijection because neither the projections in the limit case nor the injections in the colimit case are tense.

$ \Gamma (I) \longrightarrow \Gamma (J)$

are tense, and unsurprisingly, we don’t get a universal property for tense cones or cocones. Given a tense cone or cocone, the uniquely induced natural transformation is tense but this doesn’t establish the required bijection because neither the projections in the limit case nor the injections in the colimit case are tense.

It’s more natural to consider diagrams where the transitions are tense, i.e.,

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

. For such diagrams, things are better. We lose products as the projections are not tense but that’s the only obstruction. Limits of connected tense diagrams are created by the inclusion

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

. For such diagrams, things are better. We lose products as the projections are not tense but that’s the only obstruction. Limits of connected tense diagrams are created by the inclusion

as are all colimits, not just confluent ones.

First, we analyze diagrams

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

.

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

.

Proposition 2.11.

The bicategory

![]() $ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

is

$ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

is

![]() $ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}}$

-cotensored. The cotensor of

$ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}}$

-cotensored. The cotensor of

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

by

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

by

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is

$ \textbf {I}$

is

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, i.e.,

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, i.e.,

-

(1) diagrams

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

are in bijection with tense functors

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

are in bijection with tense functors

$ \overline {\Gamma } \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, and

$ \overline {\Gamma } \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, and

-

(2) natural transformations

$ t \colon \Gamma \longrightarrow \ \Theta$

are in bijection with tense natural transformations

$ t \colon \Gamma \longrightarrow \ \Theta$

are in bijection with tense natural transformations

$ \overline {t} \colon \overline {\Gamma } \longrightarrow \overline {\Theta }$

.

$ \overline {t} \colon \overline {\Gamma } \longrightarrow \overline {\Theta }$

.

Proof.

Functors

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

correspond bijectively to functors

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

correspond bijectively to functors

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma } \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

by exponential adjointness:

$ \overline {\Gamma } \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

by exponential adjointness:

If

![]() $ \Gamma$

factors through

$ \Gamma$

factors through

![]() $ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

, then we want to show that

$ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

, then we want to show that

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma }$

is tense.

$ \overline {\Gamma }$

is tense.

First of all,

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma } (\Psi ) \longrightarrow \overline {\Gamma } (\Phi )$

must be a complemented subobject for

$ \overline {\Gamma } (\Psi ) \longrightarrow \overline {\Gamma } (\Phi )$

must be a complemented subobject for ![]() complemented, i.e.,

complemented, i.e.,

for

![]() $ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

and

$ g \colon B \longrightarrow B'$

and

![]() $ \alpha \colon I \longrightarrow I'$

should be a pullback of monos. If we rewrite this in terms of

$ \alpha \colon I \longrightarrow I'$

should be a pullback of monos. If we rewrite this in terms of

![]() $ \Gamma$

and use functoriality on the vertical arrows, we see that it is

$ \Gamma$

and use functoriality on the vertical arrows, we see that it is

(1) is a pullback of monos because

![]() $ \Gamma (I)$

is tense, and (2) is a pullback of monos because

$ \Gamma (I)$

is tense, and (2) is a pullback of monos because

![]() $ \Gamma (\alpha )$

is a tense transformation (the mono part because

$ \Gamma (\alpha )$

is a tense transformation (the mono part because

![]() $ \Gamma (I')$

is tense).

$ \Gamma (I')$

is tense).

This shows that if

![]() $ \Gamma (I)$

preserves complemented subobjects and

$ \Gamma (I)$

preserves complemented subobjects and

![]() $ \Gamma (\alpha )$

is tense, then

$ \Gamma (\alpha )$

is tense, then

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma }$

preserves complemented subobjects. The converse is also true as can be seen by taking

$ \overline {\Gamma }$

preserves complemented subobjects. The converse is also true as can be seen by taking

![]() $ \alpha = {\textrm {id}}_I$

for

$ \alpha = {\textrm {id}}_I$

for

![]() $ \Gamma (I)$

and

$ \Gamma (I)$

and

![]() $ g = 1_B$

for

$ g = 1_B$

for

![]() $ \Gamma (\alpha )$

.

$ \Gamma (\alpha )$

.

Preservation of inverse images by

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma }$

is equivalent to that of

$ \overline {\Gamma }$

is equivalent to that of

![]() $ \Gamma (I)$

as can be seen immediately upon writing it down. Likewise for the tenseness of

$ \Gamma (I)$

as can be seen immediately upon writing it down. Likewise for the tenseness of

![]() $ \overline {t}$

.

$ \overline {t}$

.

Theorem 2.1.

The inclusion

![]() $ {\mathscr{T}}\, \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}) \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \,\ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

creates colimits and connected limits.

$ {\mathscr{T}}\, \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}) \, \succ\!\xrightarrow{\hspace{.3cm}} \,\ {{\mathscr{C}}{\kern.5pt}\textit {at}} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

creates colimits and connected limits.

Proof.

Given a diagram

![]() $ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

, its colimit is given by the composite

$ \Gamma \colon \textbf {I} \longrightarrow {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense} (\textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}, \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}})$

, its colimit is given by the composite

![]() $ \varinjlim _{\textbf {I}}$

is left adjoint to the diagonal functor

$ \varinjlim _{\textbf {I}}$

is left adjoint to the diagonal functor

![]() $ D \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, so it preserves coproducts and a fortiori is tense. And

$ D \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}}$

, so it preserves coproducts and a fortiori is tense. And

![]() $ \overline {\Gamma }$

is tense by the previous proposition, so

$ \overline {\Gamma }$

is tense by the previous proposition, so

![]() $ \varinjlim _I \Gamma (I)$

is tense.

$ \varinjlim _I \Gamma (I)$

is tense.

![]() $ D$

itself preserves coproducts being left adjoint to

$ D$

itself preserves coproducts being left adjoint to

![]() $ \varprojlim$

, the limit functor. So

$ \varprojlim$

, the limit functor. So

![]() $ D$

is tense. Natural transformations between coproduct preserving functors are automatically tense, so the adjunction

$ D$

is tense. Natural transformations between coproduct preserving functors are automatically tense, so the adjunction

![]() $ \varinjlim _{\textbf {I}} \dashv D$

is an adjunction in the bicategory

$ \varinjlim _{\textbf {I}} \dashv D$

is an adjunction in the bicategory

![]() $ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

, and this gives the universal property of

$ {\mathscr{T}}\ \textit {ense}$

, and this gives the universal property of

![]() $ \varinjlim _I \Gamma (I)$

:

$ \varinjlim _I \Gamma (I)$

:

is left adjoint to

which is itself the diagonal functor.

If

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

is nonempty and connected, then

$ \textbf {I}$

is nonempty and connected, then

![]() $ \varprojlim _{\textbf {I}} \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

preserves coproducts, so the same argument as above shows that

$ \varprojlim _{\textbf {I}} \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B} \times \textbf {I}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

preserves coproducts, so the same argument as above shows that

![]() $ \textbf {I}$

-limits are created in this case.

$ \textbf {I}$

-limits are created in this case.

2.4 Internal homs

Part of the motivation for introducing tense functors was that the functors

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, thought of as linear, were not in general taut but preserved coproducts, so were tense. The other side of the story is that the right adjoint to

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, thought of as linear, were not in general taut but preserved coproducts, so were tense. The other side of the story is that the right adjoint to

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, namely

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

, namely ![]() , is taut but not always tense. As Example1.1 suggests

, is taut but not always tense. As Example1.1 suggests ![]() is a functorial version of a monomial with the

is a functorial version of a monomial with the

![]() $ P$

acting as the powers, and perhaps we shouldn’t expect them to be nice for all

$ P$

acting as the powers, and perhaps we shouldn’t expect them to be nice for all

![]() $ P$

. After all, even for real valued functions, fractional powers can be problematic, and for rings, the powers are taken to be integers, not elements of the ring.

$ P$

. After all, even for real valued functions, fractional powers can be problematic, and for rings, the powers are taken to be integers, not elements of the ring.

Proposition 2.12.

For a profunctor ![]() the internal hom functor

the internal hom functor  is tense if and only if for every

is tense if and only if for every

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

, the function

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

, the function

is onto.

Proof.

preserves limits and so is taut. Thus, by Proposition2.8 (3), it is only necessary to check that

is complemented, and it’s also sufficient. This is equivalent to the condition that for every

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

be a pullback. This says that every natural transformation

![]() $ t$

for which (the outside of)

$ t$

for which (the outside of)

commutes, factors through the injection

![]() $ j$

. This is in

$ j$

. This is in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

. Using the adjunction

$ \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

. Using the adjunction

![]() $ \pi _0 \dashv Const \colon \textbf {Set} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, we have, equivalently, that every function

$ \pi _0 \dashv Const \colon \textbf {Set} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, we have, equivalently, that every function

![]() $ \overline {t}$

for which

$ \overline {t}$

for which

commutes, factors through

![]() $ j$

(in

$ j$

(in

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

). This is equivalent to

$ \textbf {Set}$

). This is equivalent to

being onto.

The condition on

![]() $ P$

making

$ P$

making ![]() tense is a kind of lifting condition. For every element of

tense is a kind of lifting condition. For every element of

![]() $ P$

,

$ P$

, ![]() and morphism

and morphism

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

there exist a

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

there exist a

![]() $ B'$

and a

$ B'$

and a

![]() $ P$

-element

$ P$

-element ![]() for which

for which

![]() $ p' f$

is connected to

$ p' f$

is connected to

![]() $ P$

by a path of

$ P$

by a path of

![]() $ P$

-elements

$ P$

-elements

Or more fancifully and more memorably, it’s a kind of homotopy pushout condition: for every

![]() $ f$

and

$ f$

and

![]() $ p$

as below there exist a lifting to a

$ p$

as below there exist a lifting to a

![]() $ p'$

with a fill in “fan”

$ p'$

with a fill in “fan”

2.5 Multivariable analytic functors

Following Fiore et al. (Reference Fiore, Gambino, Hyland and Winskel2008), we define analytic functors of several variables

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

as follows. First, for a category

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

as follows. First, for a category

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

, its exponential

$ \textbf {A}$

, its exponential

![]() $ ! \textbf {A}$

(from linear logic) is the free symmetric strict monoidal category generated by

$ ! \textbf {A}$

(from linear logic) is the free symmetric strict monoidal category generated by

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

. In concrete terms,

$ \textbf {A}$

. In concrete terms,

![]() $ ! \textbf {A}$

is the category with objects finite sequences

$ ! \textbf {A}$

is the category with objects finite sequences

![]() $ \langle A_1 \ldots A_n\rangle$

of objects of

$ \langle A_1 \ldots A_n\rangle$

of objects of

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

and morphisms finite sequences of morphisms of

$ \textbf {A}$

and morphisms finite sequences of morphisms of

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

controlled by a permutation. There are no morphisms between sequences unless they have the same length and then

$ \textbf {A}$

controlled by a permutation. There are no morphisms between sequences unless they have the same length and then

is a permutation of the indices,

![]() $ \sigma \in S_n$

and a sequence of morphisms

$ \sigma \in S_n$

and a sequence of morphisms

Composition is as expected

An

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

–

$ \textbf {A}$

–

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

symmetric sequence is a profunctor

$ \textbf {B}$

symmetric sequence is a profunctor  which for us is a functor

which for us is a functor

![]() $ (! \textbf {A})^{op} \times \textbf {B} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. (Warning: Our definition of profunctor is the opposite of theirs.)

$ (! \textbf {A})^{op} \times \textbf {B} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}$

. (Warning: Our definition of profunctor is the opposite of theirs.)

![]() $ P$

encodes what are to be the coefficients of a

$ P$

encodes what are to be the coefficients of a

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

-family of multivariable power series.

$ \textbf {B}$

-family of multivariable power series.

The analytic functor determined by

![]() $ P$

$ P$

is given by

We will show that

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

is tense. Define a profunctor

$ \widetilde {P}$

is tense. Define a profunctor  by

by

with the obvious definition on morphisms. We may consider

![]() $ Q$

as a functor

$ Q$

as a functor

![]() $ (!\textbf {A})^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

and

$ (!\textbf {A})^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

and

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

is the left Kan extension of

$ \widetilde {P}$

is the left Kan extension of

![]() $ P$

, considered as a functor

$ P$

, considered as a functor

![]() $ (!\textbf {A})^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, along

$ (!\textbf {A})^{op} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

, along

![]() $ Q$

$ Q$

For our purposes, a different description of

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

will be useful.

$ \widetilde {P}$

will be useful.

Proposition 2.13.

1.

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

is the composite

$ \widetilde {P}$

is the composite ![]()

2.

![]() $ Q$

satisfies the condition of Proposition

2.12

.

$ Q$

satisfies the condition of Proposition

2.12

.

Proof.

(1) Let

![]() $ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

. An element of

$ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

. An element of  is a natural transformation

is a natural transformation

which by the universal property of coproduct and the Yoneda lemma corresponds to an element of

Now the result follows by the definition of

![]() $ P \otimes (\ \ )$

and

$ P \otimes (\ \ )$

and

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

.

$ \widetilde {P}$

.

(2)

![]() $ Q (A_1, \ldots , A_n ; -) = \textbf {A} (A_1, -) + \cdots + \textbf {A}(A_n, -)$

a sum of representables each of which is connected. So,

$ Q (A_1, \ldots , A_n ; -) = \textbf {A} (A_1, -) + \cdots + \textbf {A}(A_n, -)$

a sum of representables each of which is connected. So,

and, as

![]() $ ! \textbf {A}$

has only morphisms between sequences of the same length, we get

$ ! \textbf {A}$

has only morphisms between sequences of the same length, we get

Corollary 2.3.

![]() $ \widetilde {P}$

is tense.

$ \widetilde {P}$

is tense.

Corollary 2.4.

For ![]() an

an

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

–

$ \textbf {A}$

–

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

symmetric sequence and

$ \textbf {B}$

symmetric sequence and ![]() a profunctor, we have

a profunctor, we have

Proof.

3. Partial Difference Operators

We want to think of a functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

as a

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

as a

![]() $ \textbf {B}$

-family of

$ \textbf {B}$

-family of

![]() $ \textbf {Set}$

-valued functors in

$ \textbf {Set}$

-valued functors in

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

-variables and study its change under small perturbations of the variables. The context is that of tense functors and for these we get a theory that parallels the usual calculus of differences for real-valued functions of several variables, much as our theory for taut functors did for single variables (Paré Reference Paré2024).

$ \textbf {A}$

-variables and study its change under small perturbations of the variables. The context is that of tense functors and for these we get a theory that parallels the usual calculus of differences for real-valued functions of several variables, much as our theory for taut functors did for single variables (Paré Reference Paré2024).

3.1 Partial difference

A functor

![]() $ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is a multisorted algebra, the sorts being the objects of

$ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

is a multisorted algebra, the sorts being the objects of

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

, with unary operations corresponding to the morphisms of

$ \textbf {A}$

, with unary operations corresponding to the morphisms of

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

. Freely adding a single element of sort

$ \textbf {A}$

. Freely adding a single element of sort

![]() $ A$

gives

$ A$

gives

Definition 3.1.

The A-shift functor for an object

![]() $ A$

in

$ A$

in

![]() $ \textbf {A}$

is

$ \textbf {A}$

is

![]() $ S_A$

is clearly tense, in fact a tense monad. Although we won’t use it here, it may be of interest to note that an Eilenberg–Moore algebra for

$ S_A$

is clearly tense, in fact a tense monad. Although we won’t use it here, it may be of interest to note that an Eilenberg–Moore algebra for

![]() $ S_A$

consists of a functor

$ S_A$

consists of a functor

![]() $ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

together with an element

$ \Phi \in \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}}$

together with an element

![]() $ x \in \Phi A$

. A Kleisli morphism

$ x \in \Phi A$

. A Kleisli morphism ![]() is a partial natural transformation

is a partial natural transformation

defined on a complemented subobject

![]() $ \Phi _0$

together with a transformation on the complement

$ \Phi _0$

together with a transformation on the complement

![]() $ \Phi '_0 \longrightarrow \textbf {A} (A, -)$

, perhaps quantifying the degree of undefinedness.

$ \Phi '_0 \longrightarrow \textbf {A} (A, -)$

, perhaps quantifying the degree of undefinedness.

These monads commute with each other

and for every

![]() $ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

there is a monad morphism

$ f \colon A \longrightarrow A'$

there is a monad morphism

![]() $ S_A \longrightarrow S_{A'}$

which is tense.

$ S_A \longrightarrow S_{A'}$

which is tense.

The main definition of the paper is the following.

Definition 3.2.

The partial difference with respect to A, or the A-partial difference,

![]() $ \Delta _A [F]$

, of a tense functor

$ \Delta _A [F]$

, of a tense functor

![]() $ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is given by

$ F \colon \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {A}} \longrightarrow \textbf {Set}^{\textbf {B}}$

is given by

the complement of ![]() .

.

Proposition 3.1.

For a tense functor