Introduction

Platforms have a growing interest in their users’ past. Since the introduction of Facebook’s (Meta’s) On This Day feature (2015) and Apple’s Memories (2016), these and other companies have designed new and refined existing algorithmically driven technologies that actively interpret and represent (in the form of videos and photo collages) their users’ past. Apple Memories is a feature that curates personalised collections of photos and videos. The curated videos are set to music and often feature people, pets, and places. Facebook’s discontinued On This Day shows content from the same day but years prior: old status updates, photos, and posts from friends. Both features present mediated memories. Apple’s version curates the memories with a mood that it selects for the viewer, and Facebook’s version attempts to present the memories as time capsules. These ‘algorithmic memory technologies’ are active curators of mediated memories. As this special collection demonstrates, the scholarship on this topic has grown steadily, presumably because of the visibility of such technologies in everyday media use, but also because they inspire questions regarding the psychological and social consequences of this type of remembering prompted and supported by algorithmic systems.

This paper sets out to answer the question of how young, ‘digitally native’ adults make sense and perceive such algorithmic memory technologies and what practices vis-à-vis these systems they employ. Born between 1997 and 2005, this group of people grew up with social media and smartphones in their everyday lives. To draw somewhat of a stereotypical image, much of their lives have been mediated by apps and stored on cloud platforms. This begs the question of how this generation of media users interacts with, feels about, embraces, and potentially resists the ‘save-by-default’ logic of platforms and the numerous ways in which platforms actively interpret and represent their users’ past.

As the growing body of research on the relationship between platforms and memory is mainly theoretical or platform-focused, this paper investigates the subject empirically, employing qualitative questionnaires and interviews, following the call of this special collection for empirical research into this topic. For this reason, the weight of this paper lies in its outline of methodology and the reporting of findings. The relatively short literature review is meant to situate the paper and to provide sensitising concepts (Blumer, Reference Blumer1954) for our Grounded Theory (GT; Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) approach. The ‘Methodology’ section outlining our approach is meant as a demonstration of what systematic empirical research into this topic could look like. In the ‘Findings and results’ section of this paper, we present the four types of broadly shared experiences of algorithmic memory technologies. This paper concludes by outlining specific avenues of further research on the basis of our inquiry.

Three ‘sensitising concepts’: Memory technologies, algorithms, and curation

Because our chosen methodological approach – GT – is aimed at theory generation, instead of testing hypotheses or applying theories, the following literature review should be regarded as introducing ‘sensitising concepts’ that give us a ‘general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances’ (Blumer, Reference Blumer1954, 7). The interrelated concepts of memory technologies, algorithmic memory technologies, and (automatic) curation will be briefly introduced here as they inform our empirical investigation.

Heersmink and Carter (Reference Heersmink and Carter2017) define memory technologies as ‘material artifacts used to scaffold or aid memory processes, comprising a heterogeneous category of objects and structures’ (417–418). Expanding on this definition, memory technologies can be seen as ‘a subcategory of cognitive artifacts’, which are ‘material objects used to aid not just memory, but all kinds of cognitive tasks and processes such as navigating, calculating, making inferences, and problem-solving’ (418). Digital platforms and social media can be included among these types of technologies because they can be used for external memory storage and cognitive offloading (Risko and Gilbert, Reference Risko and Gilbert2016), a physical extension of internal memory. In Heersmink and Carter’s (Reference Heersmink and Carter2017) view, internal memories are ‘stored in biological neural networks that are subject to blending and interfering’ and external memories are ‘stored in discrete format and are further static, less dynamic, and not automatically integrated with other information’ (419–420). Hence, internal memories can be externalised in technological form, and, conversely, external memories can influence internal memory. Finley et al. (Reference Finley, Naaz, Goh, Finley, Naaz and Goh2018) explored this interplay by analysing users’ attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs surrounding memory practices in the context of technology use. Their study highlights a nuanced trade-off between being mentally present in meaningful contexts and recording them for future recall, which creates an ‘existential dilemma’ regarding their approach towards remembering. Similarly, Smart (Reference Smart2010) explores the impact of technology from the perspective of extended cognition. Looking at the role that technology has played in memory construction across different periods in history, Smart does not believe in a unidirectional relationship between individuals’ memory externalisation onto their environment, but argues that the latter shapes the way memory is retrieved, in a co-productive manner. He also highlights the social implications in memory construction, arguing for memory externalisation and the environment as two mechanisms that meet in the form of digital memory technologies. In his theorisation, Smart emphasises a distributed form of agency (between humans and nonhumans) when it comes to memory, recall, and remembering. This distributed form of mnemonic agency is especially pertinent to algorithmic and therefore automated curation of memories, to which we will turn now.

The concept of ‘memory curation’ and its relationship with algorithmic technologies has attracted growing scholarly attention. The term relates to the ways in which people’s autobiographical past is shaped by technologies (in a broad, artefactual sense). Jacobsen (Reference Jacobsen2021) describes the ways in which algorithms curate memories and thereby also forget; they are ‘sculpting digital voids’. In order to generate the ‘right’ response (feelings of happiness) to the memory object created by, in Jacobsen’s case study, Facebook, the company actively forgets those memories that it deems unsuitable to re-present. Hence, Jacobsen (Reference Jacobsen2021) points out that sculpting is ‘not a neutral practice’ or ‘value-free staging of remembering’. Instead, we should see the sculpting of memory more as ‘“imagined” constructions’ that are moulded in and through algorithms (359). This is an important realisation, because such algorithmically produced narratives of the self ‘make people [just] as much as people make narratives’ in social media (Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2022, 1085). Consequently, we should view ‘algorithms as fundamentally narrating agents’ just as much as we view humans as narrating agents capable of their own seemingly neutral curating activities (1082).

Similarly, Lee’s (Reference Lee2020) investigation into algorithmic memory construction sheds light on how digital archives, exemplified by platforms like Google Photos, modify user behaviour based on past experiences and feedback loops. By the constant scanning and analysing of patterns in photos and videos, algorithms in Google Photos organise and classify memories based on various elements such as time, location, and visual content (Lee, Reference Lee2020). This technologically mediated approach to memory, prioritising observable patterns, shapes memory practices and prompts new modes of engagement with the past. Focusing on user experiences of this algorithmic curation, Migowski and Fernandes Araújo (Reference Migowski and Fernandes Araújo2019, 62) ‘map and interpret how Facebook users deal with the fact that part of their life narratives is now digitised and submitted to co-constitutive sociotechnical agencies’. To the authors, ‘remembering and forgetting in today’s media ecology’ is permeated by ‘paradoxical states of permanence and obsolescence, of empowerment and loss of control, and of stability and ephemerality’ (61). Likewise, Martin Hand (Reference Hand2014) explores how people experience or organise things or traces of memories as memory objects and finds that much of how memories are handled in a digital age are strongly dependent on the user and how engaged they are in their memory technologies, whether these be physical or digital, especially in the mediation of memory.

Underlying the complex interactions between algorithms, memory practices, and curation is a process of rendition: the transformation of lived experience into data that can be processed by computational processes for a specific purpose (Zuboff, Reference Zuboff2019; Smit, Reference Smit2022, Reference Smit, Hoskins and Wang2024). However, we must understand that there is no such thing as truly raw data or at least that this concept of raw data is an oxymoron (Gitelman, Reference Gitelman2013; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie, Gillespie, Boczkowski and Foot2014). All data are created and ‘cooked’. Moreover, users are never ‘just’ receivers of the outcomes of computational processes: they can actively, and consciously, shape the data that enter such systems and often actively make sense of what is produced by them. For example, related to the above-mentioned ‘sculpting’ of digital voids and the narration that takes place on platforms, Tara McLennan (Reference McLennan2018) looks into the algorithmic curation of photographic assemblage created by apps and technology in personal photographic libraries. This demonstrates the uncanny valley experience of being confronted with a slideshow of one’s own experiences, whether they be good or bad, based simply on what an algorithm thinks would be most applicable. In addition, technology is also ‘interpretively flexible’, which means that ‘its meaning is not given in design but constructed in use’ (Van House and Churchill, Reference Van House and Churchill2008, 299). Consequently, social media users are actively making sense of the outcomes of algorithmic practices. Within the socio-technical space of social media, they do so by providing feedback within the formal structure of the interface (likes, comments, and shares) and thereby ‘feeding’ algorithms. For Prey and Smit (Reference Prey, Smit and Papacharissi2019), algorithms personalise ‘memories’. Their article emphasises the accessibility and fluidity of a social network memory, contrasting it with existing forms of mediated memory. Comparing the practice of diary writing with Facebook’s On This Day feature, they emphasise how memories shared on social media are mediated by algorithms and software, resulting in an imbalance of power between users and technology. Similarly, Pereira’s (Reference Pereira2022) examination of Apple Memories delves into the hidden algorithms behind the curation of memories within the iPhone ecosystem. Pereira explores the discrepancy between Apple’s privacy statements and the way algorithms shape memory curation. By connecting memories to networked and data-driven conditions, such as computational processing and algorithmic queries, Apple Memories challenges the notion of private data and highlights the potential influence of surveillance capitalism (Pereira, Reference Pereira2022). These authors show that through automatically curating and classifying mediated memories, algorithms become intimate, and therefore powerful, and potentially problematic actors in memory construction. However, how users of these technologies experience and relate themselves to such technologies remains a largely unanswered question.

As the above brief overview shows, the research on algorithmically produced memory objects is growing, but little is known about how users experience algorithmic memory technologies, a notable recent exception being Annabell’s (Reference Annabell2023) work on Instagram memories. Such knowledge might be available to technology companies, as Prey and Smit (Reference Prey, Smit and Papacharissi2019) argue, but this is used instrumentally and used to ‘improve’ products and increase user engagement. We, however, are interested in how young, ‘digitally native’, adults perceive, experience, and make sense of such technologies in their everyday lives. The next section outlines in detail how we approach this question empirically.

Methodology

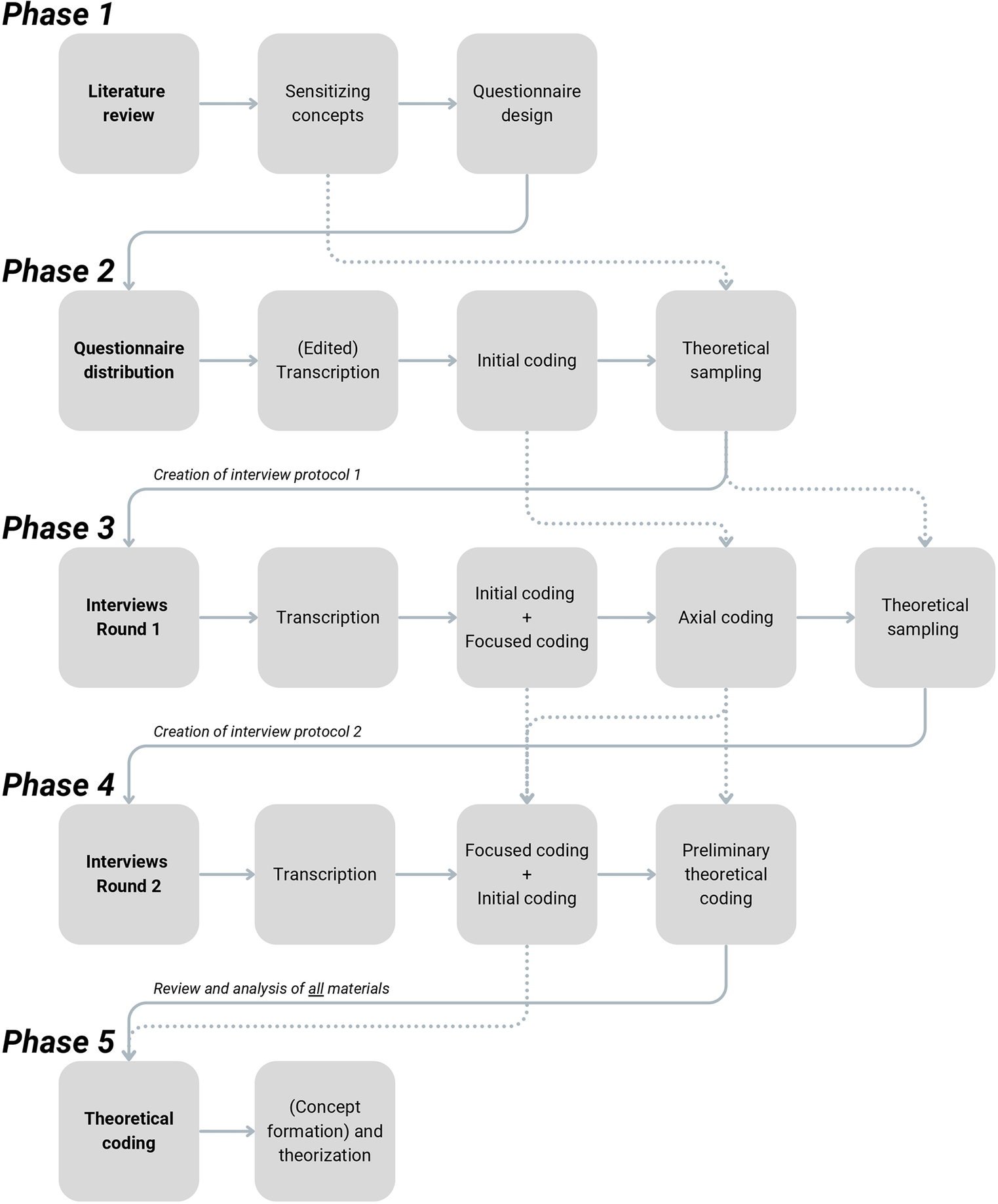

As the main goal of this study is to gain insight into user experiences, we designed a qualitative, inductive study. It prioritises the particular imaginaries and attitudes that shape and inform media use. In order to stay as close to this experience as possible, we employed a constructivist GT approach. This inductive approach ‘consist[s] of systematic, yet flexible guidelines for collecting and analyzing qualitative data to construct theories ‘grounded’ in the data themselves’ (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, 2). These methods are mostly centred on data analysis but have ‘profound implications’ (Charmaz and Belgrave, Reference Charmaz, Belgrave, Gubrium, Holstein, Marvasti and McKinney2014, 2) for data collection. The name of the method refers to the final product – a theoretical, conceptual, analytical framework for understanding and interpreting the studied phenomenon. Our study includes a questionnaire, two rounds of in-person semi-structured interviews of approximately 30–40 minutes, various coding strategies, and a gradually more conceptual and theoretical analysis. Both of these steps were conducted in English. A flowchart summarising the research design and progression discussed in this section is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research design flowchart.

Note: Note that GT is an interactive process. Moreover, at various stages, visual data analysis and memo taking and processing were also part of the process, excluded from the contents of the above flowchart.

Questionnaire

The first step in our data collection was distributing the online questionnaire. Our main and only restrictive sampling criterion was age. The study concerns the experiences of early, or young, ‘digitally native’, adults between the ages of 19 and 26 years. Where Selwyn (Reference Selwyn2009, 365) introduced the term digitally native as a broad generation (born from 1980 to the present), we use this phrase to designate the first group (of young adults) who have grown up with social media in childhood and adolescence. This group was specified in particular for their having experienced and grown up with digital memory tools, making them ideal to reflect upon the impact it has on them in their daily lives. Additionally, we were attentive to include a wide range of nationalities. Our extensive qualitative questionnaire was filled in by 36 people from Asia (purposely unspecified), Bulgaria, China, Ecuador, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Kurdistan Region, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, the Netherlands, and the United States. The mean age of the sample is 22.4 with a 1.7 SD. Out of 36 respondents, 17 (53.13%) identified as female, 11 (34.38%) as male, and 4 (12.50%) as non-binary.

The questionnaire had a total of 18 questions, the first portion of which were simply checkboxes for respondents to provide the study data as to their demographics. Nationality, gender, and age (as aforementioned) were all considered. Respondents were asked to list all social media that they use and how often. After this, the rest of the questions were open-ended to allow respondents to have a full breadth of expression available to them. We decided not to use scaling questions as we believed this might lead to missing nuance. The respondents were asked to reflect on their social media usage and how they feel about social media conjuring the past, as well as how social media might have potentially impacted their own memories as a result of it being a natural host for memories.

We distributed the questionnaire either by sharing it on our social media platforms (predominantly Instagram Stories), sharing it in WhatsApp group chats, or by contacting people directly, to start a ‘snowball sample’. We asked participants if they were willing to fill out some open questions about their digital media use, and, at the bottom, asked if they would be willing to conduct an in-depth interview with one of us on the same topic. Using the questionnaire, we aimed to get a general idea of the range of possible experiences and practices vis-à-vis algorithmic memory technologies to explore in the interviews. As advised by Hargittai et al. (Reference Hargittai, Gruber, Djukaric, Fuchs and Brombach2020), we avoided direct questions about algorithms in the first phase of the research. Direct questions about algorithms were saved for the second part of the interview so as not to influence interviewees’ thinking processes. The questionnaire can be found in Supplementary Appendix A.

Interviews

From the questionnaire, we sampled interviewees on the basis of three criteria. The first was the content of their answers. Selected participants (whose names we pseudonymised) provided a unique perspective, had contrarian opinions, or gave markedly emotionally charged answers. Overall, the detail of the answer was also taken into account, as this may signal a participant’s willingness to contribute. The second criterion was that of diversity in terms of age and nationality. In lieu of other research done in this field that has identified homogenous representations in terms of nationalities as one of the limitations of much research, we aimed at representing as wide a range of nationalities as possible. The last criterion was availability and accessibility.

We sampled nine interviewees in total. (Although Guest et al. argue that qualitative interviewing reaches saturation with around 12 interviews, Charmaz and Belgrave (Reference Charmaz, Belgrave, Gubrium, Holstein, Marvasti and McKinney2014) argue that when using a GT approach, this number does not necessarily hold up and may be reached with fewer interviewees.) Interviewees’ age spanned from 19 to 26, which is representative of the bigger (questionnaire) sample. Some of the interviewees were located in the area of the researchers’ institution, albeit having different nationalities. Moreover, in line with the sample diversity argument, the researchers leveraged their international positioning and conducted interviews with participants from their home country. The current study opted for in-person interviews, as that facilitated rapport-building, which allows deeper exploration of personal topics, such as one’s interaction with their personal media input/output, that is, one’s interaction with their online/offline identity. Furthermore, Hargittai et al. (Reference Hargittai, Gruber, Djukaric, Fuchs and Brombach2020, 4) suggest that such a method is best when participants might not be particularly knowledgeable enough on the topic in question – here, the way algorithmic curation mediates one’s identity. As such, seven out of nine interviews took place in the Netherlands (although with diverse national backgrounds), and the rest took place in the United States. The interviewees were each remunerated with 20 euro-worth gift cards.

The interviews were semi-structured to make sure to stay on topic and relate our questions to the sensitising concepts. Moreover, this maintained consistency throughout all the interviews conducted by different researchers while still allowing room for exploring the particularities of our interviewees’ experiences. We shaped the first interview protocol, consisting of seven core questions, on the basis of our sensitising concepts and the questionnaire answers, adding two or three questions for each participant on the basis of their questionnaire answers (see Supplementary Appendix B). The core questions remained fairly close to some of the most well-performing questions of the questionnaire, simply asking them to elaborate. The interviews were conducted at the interviewees’ preferred locations and took place at participants’ homes, interviewers’ homes, cafés, or study institutions. Ethical clearance was provided by our institution’s Ethics Committee, and we followed standard ethical procedures. The second interview round’s questions were in part based on interviewees’ questionnaire answers and in part on the previous interview round’s results, adjusted to pursue interesting ideas found during the analysis process and development of preliminary concepts.

Coding, or making sense in/of Grounded Theory

The power of GT ‘lies in its integration of data collection and increasingly more abstract levels of analysis’ (Charmaz and Belgrave, Reference Charmaz, Belgrave, Gubrium, Holstein, Marvasti and McKinney2014, 3). The first main step in analysis is that of coding. In constructivist GT, there are at least two phases in coding: initial coding and focused coding. The former consists of the selecting, separating, and sorting of data and giving each piece ‘an analytic handle’ (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, 45). In doing so, we ask ourselves what theoretical category the pieces of data may indicate. Codes thus emerge while reading through data, not beforehand. The only exception to this is a specific feature of constructivist GT, namely the explicit addressing of ‘sensitising concepts’, as described in the previous section (Blumer, Reference Blumer1954). These are general concepts (eg, heuristic concepts or disciplinary concepts) that function as tools to provide researchers with a point of departure. They can be removed from the research if they prove to be irrelevant (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). By explicitly identifying sensitising concepts, we can be more reflective on how they guide our thinking and their relevance (Charmaz and Belgrave, Reference Charmaz, Belgrave, Gubrium, Holstein, Marvasti and McKinney2014). We used our sensitising concepts as springboards for the first phase of the research. This proved to be salient in some cases, helping navigate the broad scope of literature we had selected. Still, we abandoned the concepts as gathered from the literature, prioritising the concepts that would emerge from the data.

Initial coding is thus open to any theoretical direction indicated by the data and seeks out early analytic ideas from early data to pursue later on (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). Focused coding takes the most important and/or frequent initial codes to ‘sort, synthesise, integrate, and organise large amounts of data’ (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, 46). This phase can be challenging as here one makes decisions about which suggested theoretical directions are most salient in the context of the research and which make the most analytic sense (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). (It is important to point out that the constructivist genre of GT emphasises the constructed nature of participants’ reports on their reality; they are not an objective portrayal. Through coding, researchers define what happens in the data and start attaching meanings. Meaning is thus emergent as the theory develops. The researchers’ work is an elaborate, abstracted co-construction of these reports; a collective, theoretical, analytic narrative developed by processing them through various levels of analysis [Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006; Charmaz and Belgrave, Reference Charmaz, Belgrave, Gubrium, Holstein, Marvasti and McKinney2014].) Either of these may prompt researchers to theoretically sample interviewees to elaborate on particular points that need further fleshing out. This is not done for the sake of representativeness but for the sake of developing categories and concepts, and so solidifying analytic power. In our research, although we do not (re-)sample specific interviewees, we planned three stages of data collection, each of which would be adjusted on the basis of emergent ideas and identified possible salient theoretical directions or gaps.

The initial codes collected were grouped together based on their larger overall associated topics, such as affect/emotion, memory, and technology in a form of pre-axial coding. In exploring the co-occurrences and relationships between the initial codes through close examination of the data and graphic visualisations of correlations through ATLAS.ti, we ended up with one round of axial coding. Axial coding ‘relates categories to subcategories, specifies the properties and dimensions of a category, and reassembles the data you have fractured during initial coding to give coherence to the emerging analysis’ (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, 73). Where initial coding sorts, synthesises, and organises large amounts of data, axial coding does this by reassembling these data in new ways. The outcome of axial coding is dense, interwoven networks of relationships around the ‘axes’ of categories. This led us from approximately 65 initial codes to about 12 axially coded categories. Although Charmaz (Reference Charmaz2006) feels conflicted about the purpose and use of axial coding in GT as it may constrict codes and so limit researchers in learning about the phenomenon in question, we would argue that axial coding assisted us in exploring new ways our initial codes are interacting by observing how they co-occur and their correlated proximity to one another.

This led us to the development of 12 focused codes for the second round. Some categories were re-examined to be better applicable as codes and cover more variations of frequently occurring intersections among certain emotions, actions, or observations. While coding the second round of interviews, we added three more codes based on conversations among the researchers. The last phase is concept formation through theoretical coding, elevating codes towards developing theoretical concepts through close examination of underlying patterns and possible new conceptualisations that can provide a particular new understanding of the phenomenon in question (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). We again analysed the co-occurrences and correlational strength of our focused codes through ATLAS.ti visualisations in combination with close examination of our data by ourselves and tried to understand how these may lend themselves to provide particular, user-experience-based conceptualisations of algorithmic memory technologies. These iterative cycles formed the basis for theoretical saturation and our findings.

Findings and results

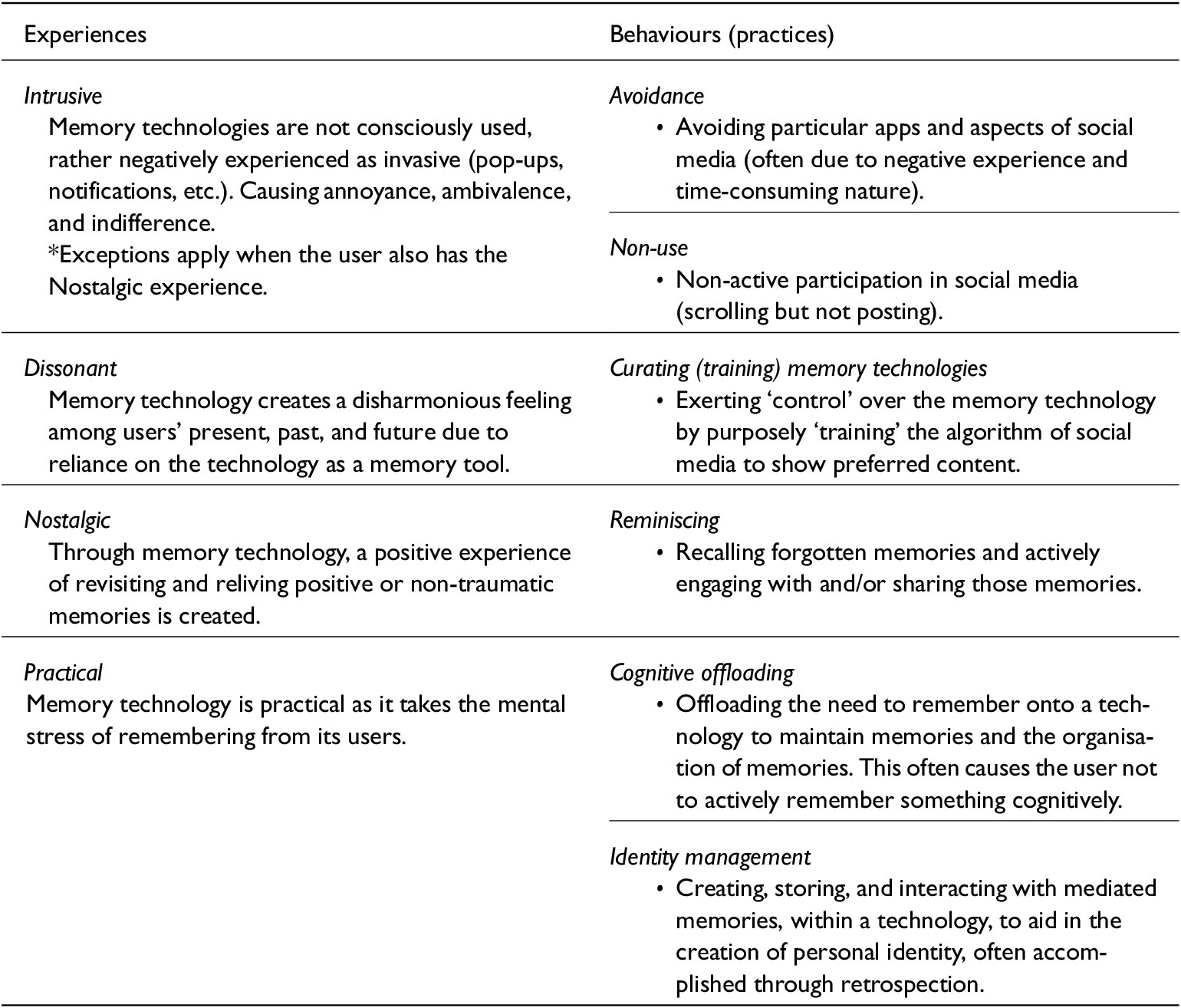

Based on the interviewees’ responses, four types of experience were identified in relation to algorithmic memory technologies, and each of these experiences associates with at least one sort of practice. Algorithmic memory technologies are experienced as intrusive, dissonant, nostalgic, and practical. These experiences do not exist in isolation. No interviewee was found to have only one of the four experiences, nor to execute one of the associated practices. These are heuristic, yet empirically grounded categorisations. In reality, practices shape experiences and vice versa. These four types of experiences are the results of grouping our initial 60 codes (see Supplementary Appendix C for a full table). In short, participants who experienced memory technologies as Intrusive tend to practice avoidance and non-use of memory technology. Those who experienced them as Dissonant tend to practice curating and/or training of their memory technology. Nostalgic experiences were often associated with reminiscing practices. Those who experienced memory technologies as being practical used them for identity management and cognitive offloading. Table 1 illustrates the experiences and their associated practices:

Table 1. Experiences of memory technologies and their associated practices

Interviewees discussed a variety of social media platforms, including Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and Snapchat, next to default software, such as the iPhone Memories feature. Note that some quotes and paraphrases of interviewees in the following sections note the particular social media when relevant. Not mentioning a specific social media was done when interviewees were being general about their media or speaking on memory technologies in general terms. Importantly, all experiences expanded on below were based directly on the use of algorithmic memory technologies; however, the behaviours and practices that stem from these experiences cannot be considered in isolation. As such, all behaviours and practices should be considered as being influenced, but not exclusively caused, by the experience of algorithmic memory technologies.

Intrusive experience

Memory technology can be experienced as intrusive in the life of an individual. By intrusive, we mean that memory technologies are not consciously used but are experienced as invasive by participants. Pop-ups, notifications, and post recommendations are examples of intrusive memory technology (eg, the iPhoness Memories feature). There were markedly few reported positive experiences of intrusive memory technology. An exception was that of Luna (they/them), who enjoys memory pop-ups: ‘I do quite like it because while I do know that I post the highlights [in my life] to Instagram or whatever…it is nice, sort of going back in my phone seeing photos that I’ve taken on that day, or like taking in the past that weren’t necessarily the highlights, and were just nice things that are for myself’ (Luna). Respondent Miguel experienced both negative and positive feelings after memories were presented to him. It was positive, as things like progress in musical talent or in physical fitness were more easily tracked. Yet, he was also embarrassed by this because it confronted him with how poorly he was doing in the past. ‘Of course you will feel good, because you see, “ah, you improved a bit”’ (Miguel), but that same experience might bring back unwanted memories of times best forgotten.

Some respondents also expressed a degree of annoyance, attributed to what kinds of things; in this case, Facebook and the memories it keeps or thinks are important enough to push back towards its users. Miguel, again, notes:

Facebook keeps sending me notifications like ‘today’s this guy’s birthday’. […] I don’t really care. Like some people, they’re not close to me, and also Facebook keeps sending you these things. Sometimes Facebook forgets to send you the important, close friend’s birthday. Sometimes they just send you some random people’s birthdays. (Miguel)

Acting as a form of external memory, Facebook does not take into consideration the nearness of relationships but seems to arbitrarily present memories of events that may or may not be important. Equally, content is not evaluated; therefore, memories presented to users are seemingly random, which can lead to extreme annoyance, which is remarked by V (chosen pseudonym):

I get annoyed because some of the memories that it pulls up is stuff I don’t want to see. And so I’ll go and I’ll delete it real fast. I’m annoyed like, bro, my mood drops. But, yeah, like when it just brings up memories that I don’t want to remember about because I even forgot I had it. That’s when I get really annoyed. (V)

Instagram story pop-ups and memory notifications seem to have a greater negative than positive effect on users. This is illustrated by Jenny:

I have depression. And back when I was at some of my lowest points, I had the worst memory. And I would kind of misuse social media. And I would post things that I shouldn’t have posted, say things that I shouldn’t have said. And looking back on that when I get a pop up from Instagram being like ‘teehee, here’s a memory from like two years ago’. And it’s something that I had posted that I really was not proud of, I had kind of subconsciously blocked that part of my life out. And so for Instagram, I guess is kind of a good example, to constantly bring that back up. Definitely makes me remember more than I would like to remember. But on the more positive side of that, the same thing like concerts and memories that I do want to remember, I feel like I, in general, just have a bad memory. (Jenny)

Jenny is grateful for intrusive memory notifications because of her bad memory. For V, however, the negative emotions associated with the posts have a strong negative impact on his emotional well-being in the present. These posts are chosen by algorithms and pay no heed to content and context when deciding to present the memory to the user.

When asked about the way in which the iPhone selects images to present as memories or to archive into galleries, Maeve says: ‘I hate the fact that it shows some people by faces, I find it completely terrifying… you know the people and it recognizes the faces and everything and just I don’t know it feels, it feels… Invading. Yea. Invading…’ (Maeve). The intrusive nature of memory technologies is not limited to the intrusive pop-ups, but also the need for memory creation. Samantha found that when going to concerts, she was annoyed at seeing a ‘sea of phones recording something’ that she found ‘sort of obstruct your view literally and figuratively as well. If you’re enjoying something… and there’s phones in front of you. It feels a bit disconnected, I guess’.

The nature of these notifications and why companies want users to use them or respond to their memory notifications is not unknown to the users most impacted by them. Profit is mentioned more than once by several of our interviewees when discussing why they think social media and technology employ intrusive memory technology. Avery remarked that:

…to increase engagement […] somehow equals more money for them. They’re like ad pushers and stuff like that. So I do think it’s just, they’re always trying to find different ways to increase engagement. So some will try to hit you with nostalgia and like, ‘hey, remember what you did six years ago’. And that’ll get you to click the app and look at it. And ideally, then proceed to spend two hours scrolling through your feed. (Avery)

Avery is not alone in her thinking. Luna, for instance, seems to agree, ‘…my best guess would be if they give you the memory… Lots of people do repost the “one year ago, this was a happening” and more posts, more users, more engagement, getting the numbers up to help with the business’ (Luna). While Avery and Luna note that user engagement is the aim of the company, the purpose of memory notifications is seen differently by Simon:

Yeah, I think it’s better bait to say in a way… People are inherently kind of self centered. So if you show them something like, ‘Hey, this is something you did that many years ago’, you’re like, ‘how many years ago? What happened? What? What do you mean? I did this eight years ago’ or. ‘Look, look, I moved eight years ago’. Literally, no one else cares. But they do because it’s something they did. (Simon)

Regardless of whether it is a marketing ploy to gain more profit or simply is in the nature of humans to want to reminisce, user awareness of the tactics employed by companies to gain their interest does not, at first, seem to affect whether or not a user interacts with the media or technology. Users are aware of the positive and negative aspects of the intrusiveness of the memory technology. When discussing Instagram posting recommendations, based on previously shared stories, Samantha noted that:

…then sometimes you will get like… a sort of pop up story of yourself. And you’re like, ‘ooh, remember, on this day in 2019, you were hanging out with her now ex boyfriends’ so invasive most of the time, but it also depends on what kind of connection you have to the person or thing. (Samantha)

Later, Samantha also remarked that the emotional options she felt she had when a memory notification occurred were ‘either be nostalgic or annoyed… depending on if it is a bad thing or someone who you would rather not think of a lot…’ The context is of vital importance to the user, but primarily, our interviewees found the intrusive nature of the memory notification to be a negative influence on their experiences of memory technology. This negative feeling, in turn, impacts their practices when it comes to technology and social media use.

The intrusive experience takes place when memory technologies are not consciously used but are experienced as invasive, through unwanted and often negatively received pop-ups and notifications. These primarily negative experiences cause a variety of behaviours and practices as a result, including the practice of avoidance or the non-use of a media or mediated memory technology.

Avoidance and non-use

Avoidance and non-use of media and platforms were widespread practices among our participants. Annoyance, ambivalence, and indifference were related emotions. Ambivalent practices are exemplified by several of our interviewees, including Jenny, Avery, and V, who stated that they did not use social media much because they did not post often on their social media. However, they also admitted to a fixation with scrolling on their social media app while not classifying it as social media use. We found that this indicated a dual, dissonant awareness of their relationship to these technologies, causing them to ambivalently fluctuate in their responses. Participants were sometimes indifferent towards a certain aspect of algorithmic memory technologies. It indicates that they perceived no effect on themselves or their behaviour, rather than simply a neutral response (where they would be affected but not overwhelmingly positively or negatively so).

Interviewees exhibited ambivalence or indifference on various occasions. Social media addiction seems to be a prevalent topic when users are asked about social media use and practices in general. Some avoid certain types of apps due to addictive tendencies, including Luna, who avoided newer apps like TikTok because of the ‘rabbit hole’ of scrolling through the app, while others are aware of their addictive tendencies but still seek out these apps. Many let apps and memory technology guide their behaviour, and some even mentioned losing time suddenly without realising it. The intrusive experience of being controlled by their memory technologies made some engage in practices of avoidance or non-use. Avery, for example, stated that two aspects of social media take over her life: ‘There’s communicating with people. And then there’s just like, the almost obsessive, just in taking content, we’re just like, I’m gonna watch a bunch of short-form videos for hours. And that’s gonna be my life’ (Avery). This latter statement exemplifies how our interviewees are aware of how present social media are an integral part of their life, to a degree it is prone to create a cycle hard to break.

Even so, the interviewees made distinctions between the normal use of social media and the addictive use of social media, even within a day. When describing a day of social media use, Jenny described only starting a regulated and controlled amount of social media use while at work, but when getting home from work ‘is when it starts to go downhill because the second I’m home I am like a hermit crab. I’m in my room, cuddled in a blanket, just scrolling through TikTok’ (Jenny). Her perpetuated social media use continues for the rest of the day, seemingly beyond her control. Despite her self-declared addiction, Jenny sets deliberate times of avoidance and non-use in order to function normally. When it comes to scheduled social media use, many of our interviewees cited social media breaks as part of their regimen to avoid the intrusive nature of social media.

This shows the degree to which social media, and the distinction between being online and offline, becomes integrated into one’s daily routine, thus adding an extra interpretative lens through which the world is perceived, but which then also ‘demands’ a reaction through this medium. This is one of the reasons why reminders of the past might have such an impact. In this way, users record updated and/or curated versions of themselves at different points in time. Additionally, these curated selves cause a disconnect between the online and offline experience, creating what we have termed a dissonant experience.

Dissonant experience

The experience of dissonance describes the clashing of realities or feelings of disharmony in one’s life. The degree to which this affects someone can vary greatly, but this experience was reported frequently by the interviewees in this study. Missing out on the present moment, for example, is an experience that our interviewees attributed to using and relying on their phones and social media:

Because … I’m using [my phone] in between things, then I’m like, ‘I just did something like half an hour, right?’ Then you’re watching video after video. And then if you try to make yourself remember what you did for the last half, I can’t name a thing. A few things that I find striking or send my friends and then they reflect on that. Then maybe it’s starting a conversation. So then I remember that I talked about this, but if I don’t interact with anyone, like if I don’t send a TikTok to my friend, then I don’t remember what I did for that … half an hour. (Maeve)

Some interviewees expressed a degree of separation anxiety about not having their phones with them, either because of their self-described ‘bad memories’ or because they could not record the present. For example, Miguel expressed that when he had left their phone at home by accident, ‘I felt really bad. Really bad, because I don’t really trust myself with the time slot for all these classes, like schedule wise. Like I felt a bit… A bit disappointed without the phone’ (Miguel). A major amount of reliance is placed on the phone as a form of external memory for everyday life tracking, as well as notification of memory, whether that be scheduled events, the creation of new memories, or the notification of old memories. Creating memories to keep for later somehow outweighs the enjoyment of an event to many others. That is why the interviewees expressed a need for alternative practice, strategies to control the memory technology that was almost controlling them. We call these curating and training practices.

Curating and training

The practice of curating and training the memory technology (whether by ‘playing’ the algorithm or other methods) relates to agency and control. Although agency and control were not always mentioned in conjunction with algorithms, interviewee Simon made the connection. He commented extensively on the degree of control he felt in social media and why he used them but did not necessarily like them, and attempted to the best of his ability to control them. Making conscious choices to change the way the algorithms worked for him and having that determine the types of apps he preferred to engage with. For example, Simon, when talking about Tumblr, says:

It’s way easier to curate than, say, Facebook… Because Facebook is way more algorithm focused than Tumblr. Tumblr is more of a ‘you follow what you want to follow’ or ‘who you want to follow’… but I have no qualms blocking or removing stuff from my feed. If something comes along and it’s really annoying and it keeps coming along, I will just block it. I don’t care. (Simon)

When asked about the way apps function and the interviewee’s perception on why apps function in the ways that they do, one interviewee states that they ‘[g]et a notification and be like, “Hey, come look at this. This happened on your app, come look at the app.” And then you open the app and then you get to your newsfeed after you watch the notification and then you enter the doom scroll’.

Asked why platforms offer memory technology, our participants thought financial gain was the main driver. ‘So it’s just a way for people to or a way to get people to engage with the app because the way they’re designed. The apps, once people get engaged with it, like are using it, they usually use it for longer amounts of time’ (Simon). When asked for further elaboration, Simon likened the intrusive nature of memory technology and media to people trying to lure cats to themselves with noises and ‘then once you’re there, they try to keep you there by using features like the algorithm and stuff like that and like stories and whatnot. Because the more time you spend on the app, the more money they make because that’s just how their business model is built. And, I mean, it’s not going to work. You can try to lure me in, but I just get annoyed’ (Simon). The awareness of memory technology extends to a degree of fear of the lack of control given to the one experiencing the memory technology and media:

Sometimes it will give you a notification of, Hey, here’s what you did two years ago and sometimes it won’t. So for example, like if you get that pop up once you see it’s like, ‘Oh, let me check out what I was doing two years ago’. And then sometimes you’ll think like, ‘Oh wait, let me just actually see what I was doing that month’ instead of just on that day. And then you think like, ‘Oh wait, there were so many other things that I wasn’t reminded of. Thank you, Instagram’. But then you’’re still like, ‘Oh, that’s’. Then you’re suddenly reminded, that it’s something you can keep track of, even though it doesn’t remind you all of the time. So that makes you wonder what does Instagram favor to, you know, push us like on this day in 2022 or whatever. (Samantha)

Resisting the allure of algorithmic curation, Simon explained his practice of curating his feeds by ‘training’ the algorithms of his various social media. He does so by liking, disliking, blocking, and hiding various things. This varies from app to app and is a point of contention for Simon. He details how this affects his experience between using Facebook and Tumblr, where Tumblr allows for a more curated experience that is, by extension, preferable:

I do that with pretty much every app. Facebook is a little bit harder because it’s curated, but if I don’t like it, I press the X, and then it will disappear or the algorithm will try to figure out what I didn’t like. And then it will try to show me other things. And every time I don’t like it, it’s just gone. So I have the things I follow and like… I interact with those. So the algorithm thinks ‘He likes those’ which is accurate. But instead of just interacting with the algorithm in a way that shows what you like so they can recommend things that you like, I also very strongly show what I don’t like, which makes it easier. (Simon)

While for some interviewees, like Simon, algorithms are present to be corralled into following one’s preferences; for other interviewees, algorithms are so present and normal in everyday life that they do not think about them often. When asked about their thoughts or whether they reflected on memory technologies, Jenny remarked that:

Maybe they want you to then go down a rabbit hole of looking at all your memories and reposting them and in turn, using their app more. I would like to say that there’s a part of them that is doing it for humanity. Like, ‘yeah, we want people to remember the fun times’. But I also just feel like that’s not the case. (Jenny)

All interviewees were, however, to various degrees, aware of how algorithms are used to represent their mediated past to them. Interestingly, the way in which most interviewees talked about algorithmic interventions was almost blasé. Interviewees considered algorithms as unavoidable and sometimes annoying background technology that, in the first instance, does not affect them very much. However, when nudged into thinking more deeply about the subject, our interviewees recall instances in which algorithmic interventions in their past were hurtful or added to dissonant experiences, where a past that was presented to them did not correspond with the experience of that past. This led to active curation of memories by many of our participants, who actively ‘feedback’ to algorithmic memory technologies.

Nostalgic experience

Besides intrusive and dissonant experiences, algorithmic memory technologies were reported to invoke bittersweet feelings of nostalgia. Nostalgia is a reminiscent experience where one can be mentally or emotionally brought back in time to memories that were positive or non-traumatic. One of our interviewees gave the example of them having:

…pictures and videos from when my brother and I were little kids, and we would play outside in the backyard with our family dog… And I would post it sometimes like, ‘Oh my gosh, yeah, look, this was when we were little kids’.… That definitely makes me feel nostalgic, getting to look back at those memories and parts of my life that you don’t really appreciate until you’re out of it. (Jenny)

Overwhelmingly, among our interviewees, nostalgia in response to memory technology was experienced quite positively. Nostalgic notifications elicited happy emotional reactions. Avery said:

…between being able to like, look back on these videos, and then sometimes those little pop up that are like, hey, remember this moment six years ago?… It gives you such a little moment of happiness when you see that. Like, I will have a completely normal day at work and then I’ll get a little pop up ‘remembering this moment with your mom’, and I get to see it, I’m like, ‘oh, yeah, I do’. And so it’s just something small that you can kind of keep with you and you can look back on and have a happy moment. So you don’t lose anything if you didn’t have that video, but you definitely gained something by being able to look back on it. (Avery)

Here, we can see what these memory technologies are attempting to achieve by eliciting nostalgia in users. As discussed earlier, many of our interviewees were able to identify the marketing strategies in place to get people reminiscing and going through the apps. When the memory presented elicits nostalgia, this is perceived in a positive way. When asked whether there was a degree of anticipation to reviewing memories through memory technology, Samantha responded that she thinks so:

Yeah. Because besides that you want your friends and family to see whatever it is that you’re doing and experiencing, you also have basically your own feed… that is something you can look back on. And you also want that to be, a sort of happy diary, or, not everything has to be happy, but at least things you want to memorize, right? Like, ‘ah, these are milestones in my life’. (Samantha)

When asked about the features of memory technology they possess, Maeve specifically noted how strange the iPhone’s randomness was in presenting various miscellaneous images from years prior. Upon prompting her emotional response, she noted, ‘Nostalgia, mostly, but also… I’m not in touch with those people anymore… So this is… also the trigger to remind me that some people exist sometimes… And then, then I go and check what they’re up to’ (Maeve). The memory technology Maeve interacted with directly influenced her nostalgic impulse to reconnect with friends or acquaintances from years past, nostalgia taking over and reinforcing relationships.

Not all interviewees felt the same way though, for some the presentation of nostalgic memories felt disingenuous, a marketing strategy to try to pull one into the applications and technologies that use them:

I always see nostalgia as something like rose tinted lenses. When you look back things are always better than they actually were. And I guess that very much resonates with how I use social media, of: I only put like the things I’m most proud of, or the things that I find happiest. And so it does mean that it preserves… like when I look back it’s like ‘aaah, those were the good old days!’ When actually, if I went back there, they were not. (Luna)

Critical remarks notwithstanding, our participants were actually quite positive about algorithmic memory technologies, ‘leading’ them into a state of nostalgia.

Reminiscing

The nostalgic experiences associated with algorithmic memory technologies resulted in the practices of reminiscing. Algorithmically prompted reminiscing is not only about recalling a forgotten experience or fact but also involves the practice of thinking about and sharing of such experiences and facts. A nostalgic experience started by an algorithmic memory technology often leads to the sharing of a memory with others, according to our participants. This, however, is also critically reflected upon:

…it kind of defeats the purpose of that moment being private and you holding on to that memory on your own… Like, because now you’re sharing it with everyone, and it’s not really like your specific memory, I feel like then it kind of loses the intimacy of whatever moment or memory you’re thinking of…. (Jenny)

The personalised mnemonic bubble created ‘for her’ creates a moment of introspective reflection, but simultaneously leads her to share this moment with others. Interestingly, Jenny regards the memories algorithmically presented to her as private and sharing them makes them less intimate.

Practical experience

Besides being experienced as intrusive, dissonant, and nostalgic, memory technologies were often experienced as practical by our participants. Important to stress is that the category ‘practical experience’ is the least exclusive of our categories: even when algorithmic memory technologies are considered intrusive and dissonant, they are used in practical ways by our participants. In this case, practical experiences denote that the use of memory technologies, and aspects of social media associated with memory technologies, had practical and tangible uses to the lives of our interviewees. These experiences and practices were not necessarily explicitly noted by our interviewees or questionnaire participants, but were inferred from reported uses of memory technologies. Whether these experiences were to do with making their lives easier or helping them grow as a person, his practical experience is mainly manifested through the practices of cognitive offloading and identity management.

Cognitive offloading

Cognitive offloading was noted by some of the participants, who found that they could not remember things as clearly if they had photographed or filmed the event they were speaking about. Some remarked on the security of technology as a memory tool to justify and explain their reliance on it. Others also attribute the impact of memory technology to their own poor memory making ‘part of the reason I have a bad memory is… When I record things. I’m subconsciously, like “okay, I can watch that back later. I don’t have to remember it.” Because I know that I’m going to be on my phone…’ (Jenny). Others, like Avery, gave lengthy anecdotes on how, especially with family, the act of nostalgic reminiscence was more strongly attributed to memory technology to which the memories had been delegated than the act of remembering it for themselves. The shared, mediated memory in this case becomes a means to reminisce together. At the same time, this mediated memory becomes the memory. This ‘overwriting’ by media is the reason why some of our participants resisted cognitive offloading, quite consciously, to make ‘the original’ memory more authentic:

I personally find that it’s easier to remember an event or somewhere I went if I don’t take pictures, because otherwise I’m focused on, like, taking the picture and I forget to actually remember the event… Like I’ve been to a few concerts now. I remember the ones where I didn’t take video or pictures more than the ones I did. And I look at the video and I’m like, I don’t remember this at all. (Simon)

Soares and Storm (Reference Soares and Storm2022) call this the ‘photo-taking-impairment effect’ (PTIE), which was acknowledged to have been first been noted by Henkel (Reference Henkel2014), who found that when subjects take one or multiple images of an object or event, the resulting cognitive offloading leads to a decrease in actual detailed memory of the subject of the image. This is also a finding reflected by Finley et al. (Reference Finley, Naaz, Goh, Finley, Naaz and Goh2018) in which 46 per cent of the respondents acknowledged the importance of both being mentally present and recording an event; however, 9 per cent of this group stated that recording practices take away from their experience. Echoing this, Simon stated:

I think it’s because I’m less focused on being there and more focused on ‘Is it correctly in the screen and can you hear it?’ And ‘Could you maybe hear me in the background’ or something like that… It’s more phone focused. So I remember being on my phone because that’s what I’m doing and it’s not necessarily remembering what’s happening around me. (Simon)

Both in the work of Henkel (Reference Henkel2014) and the work of Soares and Storm (Reference Soares and Storm2022), participants were not asked what they were focusing on when taking their images, or how much focus was on the technology rather than the objects being photographed. Simon having the self-awareness to attribute his PTIE to the fact that he was focused more on the quality of the mnemonic product than on the actual event taking place, opens interesting avenues for further research. For example, could PTIE be less strong if participants were asked to focus on various aspects of the photo-taking process or the subject matter?

Managing identity practices

Managing Identity refers to how our participants create, curate, store, and interact with mediated memories in a manner that, in some way, aids them in the construction of personal identity. One questionnaire question asked whether respondents believed that their memories were affected (making and recalling memories) as a result of social media (ie, memory technologies). Questions concerning the topic of algorithms were included without naming them in the interview and questionnaire questions (for the full question lists, see Supplementary Appendices A, B, and D). The majority of questionnaire respondents believed that there was a shift in how they make and recall memories. Those who did not think this was the case often did have a caveat, such as remembering that they had taken photos or videos of an event to look back on. Some even noted that it allows them to see the memories in a different way, meaning that there was acknowledgement that the memory was no longer unaltered or perfectly archived without modification, another example of cognitive offloading. Once captured and stored, one can reflect on the difference between what one sees and what is remembered of the experience. Out of the 36 respondents, only 6 reported that they felt no changes at all.

During the analytical phase of our work, the word ‘cringe’, taken from our original questionnaire, as well as codes surrounding change and personal image, greatly reflected the understanding of identity management. Participants indicated a dissonance between perceived past and present self and identity, leading to practices one could term identity management. Whether it be behaviour, personal image, likes, and dislikes of past and present, identity management was done both as a physical and mental practice. For example, V stated that ‘when I look at old videos of myself on the internet that I posted, it’s cringy. It’s very cringy. It’s like, Damn, my young self was doing that. It’s hard to look at’ (V). This degree of discomfort was not always about the active seeking of past self on social media, and not denoted by an extended period of time either.

Jenny notes that posts even as little as a year previous create this degree of cringe. ‘I personally cringe whenever I see memories from Instagram, where they’re like, look at this memory from a year ago. And it was just me posting things I shouldn’t have posted. I am internally ashamed of that, and not proud of it, and I cringe’. While shame is a factor, there can also be a more positive interaction with this discomfort, specifically that cringe (though difficult and uncomfortable to deal with) is a sign of physical and emotional growth in a person. It indicates that a person has changed to the point that they can recognise past behaviour and find that their identity differs in a, most likely, positive direction. When looking back at their own growth of skills, such as dancing in Jenny’s case, some found that the discomfort garnered from revisiting the old images and videos was a part of growth ‘even though that cringe is painful for me to go through, I do think it kind of shows that we’re growing a little bit’ (Jenny).

The practice of identity management includes a great element of retrospection, where interviewees manage their identities in the present by reflecting on the past and seeing change and growth. That is part of the reason several interviewees did not mention deleting their old images or further managing their digital identity to erase their pasts. Miguel mentioned at one point that ‘it was interesting to see past images (intrusive notifications) as he was losing weight and the changes he saw were something to be positive and proud of’ (Miguel). This is also present in the changes people see in themselves and physical objects, like Samantha who mentioned that when looking back on posts of a friends social media from almost a decade ago, she can see things that she still owns (a specific shirt) though the people in their lives have changed ‘when we were on an exchange in Latvia. And we were on the beach and I was wearing a shirt that I still have. And I was like, “Oh, look at that. It’s been almost a decade. I don’t see you anymore. I don’t speak to anymore. That’s okay”’ (Samantha). The identity management through the practical application of memory technology introduces a great degree of introspection and intentional remembering beyond a digital space; physical changes and physical items have a great impact on the person who is revisiting those memories. Intentional in this case, as one would seek these images out to actively reminisce on the past and how one has changed.

When asked about the practicality of memory technology, Maeve mentioned that ‘revisiting a moment of joy in a time of stress, reawakened positive feelings in the present’ (Maeve). Going on to mention that because of the shortened timespan and memory notifications that modern memory technology and media offer, the ‘incubation time’ is shorter and one has to ‘remind myself to enjoy’ the here and now, not just look back on things. This practice of memory management leads to a degree of emotional identity management for them as well. Good memories are commonly mentioned in relation to the practicality of memory creation and in such good experiences that shape identity. Samantha mentioned Snapchat as a ‘really good example’ of memory notifications because the reminders are often of things that she only has vague memories of, or have an overabundance of similar memories of. This makes participants feel that memory technology is practical and leads them to create memories in that way more frequently. However:

…it’s a sort of double feeling of man, sometimes it would be nice to capture things a bit more often. So I can look back on them and visualize, actually see the things… but at the same time, sometimes I find it a bit annoying when people pull their phones out all the time to capture things in order to memorize them. (Samantha)

This leads to a degree of anticipation to review memories, both from individuals and those in their lives. The same is felt by other interviewees, even though it can invite a degree of apprehension with the random nature of the albums and notifications, some considered it as ‘nice. But one thing that kind of scares me is when some suggested posts really hit something that you would like not to remember. And that really makes me think that they really know everything about myself’ (Matt). Regulating personal identity in the face of rapidly decreasing feelings of privacy is something that many of the younger generations now have to manage to the best of their abilities.

Most of our interviewees also extrapolated on the bittersweet nature of identity in relation to memory technology and media. They regulate their identities in accordance with what they believe others do:

I don’t know about other people, but I approach social media as: ‘I don’t have to show the negative sides, and not many people actually do’. And so, anything I post on social media, it is definitely the highlights or the most fun things or like things that I’ve enjoyed the most. And so when I look back on social media, it is nice to see the highlights. (Luna)

By only posting what they think is best in their lives or only showcasing the best parts of their lives, they and most others using social media as memory platforms and media create an idealised personal identity to present to others. When it comes to showcasing a realistic version of themselves, many respond in the same way Luna does:

…my personal image, I am very uncomfortable with… So I tend to not post… Because I feel like there’s the pressure to maintain, the perspective of happy go lucky, flowers everywhere, ‘I don’t have any mental health problems at all. No way’…. it’s not that I don’t want to show people. But… I like privacy. And, I don’t mind showing people, I just can’t be bothered to, I think is the best way to put it. (Luna)

This can be exacerbated to the point where even the interviewees have to remind themselves that the identity they presented online does not necessarily reflect the identity of themselves in real life. When speaking of seeing an image of themselves on memory technology, Maeve was inspired to recreate an outfit she wore, noting that:

Oh, it doesn’t fit me as well anymore. And then I’m thinking, ‘yeah, because in the photo, I’m posing, I have makeup on and I have straightened hair and I’m wearing these clothes, but I know I’m holding my breath in to look better in that photo’. Or… oh I know I took this BeReal and I took my hair down…I am aware I did that and I have to remind myself that, in that photo I look better than I do now…. (Maeve)

However, Maeve goes on to note that to mitigate the creation of one perfect rendering, she rarely delete any of the ‘bad’ or unedited photos, as well as intentionally take silly photos to keep a degree of realism for herself when she actively goes back to look for particular images prompted by the memory technology.

While some of our participants brought up the negative aspects of identity management through memory technology, others attribute their identity management, and whether memory platforms are positive or negative, to the direct changes they make in their own lives. Perceived negative and positive effects clearly depend on feelings of self-improvement: ‘If every year you get better and better with your life, maybe it’s sweet and nice. If your life gets worse and worse every year…[silence]’ (Miguel). Memory technologies are clearly perceived as practical in terms of identity management, but only when that identity lives up to a certain standard in the present.

Conclusion

Our explorative research has shown that users of memory technologies perceive effects on what, how, and when they remember and, importantly, what they forget when not using these technologies. Overall, this paper supports the insight that remembering, perhaps increasingly, is a distributed process that involves new, semi-autonomous, and automated actors who shape memory-making in new ways. Like Annabell (Reference Annabell2023), who demonstrated that pre-digital memory practices are continued, in remediated form, on social media, we demonstrate that algorithmic memory technologies are experienced in various and intersecting ways, from relatively negatively (intrusive and dissonant experiences) to mostly positively (nostalgically and practically). Moreover, they are actively made sense of through various practices and uses, from avoidance and non-use to curating and from reminiscing to cognitive offloading and managing identity. Lastly, we see a clear critical stance towards the business models of platforms and their links with surveillance, resulting in feelings of intrusion into the private sphere. This shows that (algorithmic) memory technologies have intended and unintended uses and consequences that research has only sporadically picked up on.

Methodologically, this study offered a kind of systemisation in concept and theory formation that might aid future research in Memory Studies. Though GT makes no claim to objectivity (see also Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006), the particular strategies involved allow researchers to stay very close to the data while still allowing for degrees of abstraction and concept-formation. The risk of overreduction is minimised, doing due justice to the particularities of experience. By applying one’s theoretical sensitivities to the data, subtle nuances of meaning may be detected and accommodated. Understanding experiences on their own terms is as important as the detection of (hidden) patterns through other empirical means, as it provides us insight into people’s varied ways of thinking, use, and feelings surrounding these media – which are often omitted from other empirical approaches, where this part of the data is reduced quantitatively (to numbers) or qualitatively (into preconceived notions/theoretical concepts). Letting go of sensitising concepts after they have fulfilled their role in GT methodology is a prime example of this commitment. Though they were helpful in the beginning phase, abandoning them led to more complex and nuanced related concepts. This allows the particularities of experience to truly guide theory formation, which is at the heart of GT’s epistemological core.

Besides the fact that the use of GT itself is an addition to existing literature, we have also deviated slightly from its traditional empirical program. We experimented with our data collection and analysis. For example, our questionnaire helped in the formation of sensitising concepts as well as data collection. We also used it for theoretical sampling, which means our final round of interviews was theoretically sampled through both the outcomes of the first round and the axial coding, as well as the questionnaire. Both the questionnaire and the coding in ATLAS.ti afforded visual data analyses not native to GT, but are helpful in understanding how each phase of research changed the shape of findings until that point and may streamline certain parts of the process by helping maintain an overview without losing one’s closeness to the data and related participants. (Codes made in ATLAS.ti can also be listed related to all data chunks coded, simultaneously viewing co-occurrences.) On top of this, the added options for analysis could open up new ways to arrive at theoretical findings. This might not be a novel of an insight for qualitative research in general, but it might be with respect to GT. This dynamic empirical approach could be helpful for other researchers interested in GT, especially ones with larger numbers of interviewees or ones with similarly complex research design constructions as ours.

Our research is limited by its scope and time frame and should be seen as explorative. An idea for follow-up research might be to compare experiences of age groups, where a similar study is conducted on an older target group, and then compare the outcomes to this research. Moreover, a more in-depth comparison between different national media cultures might yield relevant insights into the relationship among algorithmic memory technologies, practices, and experiences. Lastly, quantitative survey-based research or psychological research in controlled environments might shine light on broadly shared attitudes and mental processes vis-à-vis these increasingly pervasive technologies of memory.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/mem.2025.4.

Data availability statement

The data for this research consist of qualitative interviews and contain personal information. We pseudonymised the data. The data are not available upon request and remain on secure servers of our institution.

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Tara Joanroy is a lecturer and research master’s student at the University of Groningen.

Elise Steenvoorden is a research master’s student at the University of Groningen.

Dan Padure is a lecturer and research master’s student at the University of Groningen.

Robert Venger is a research master’s student at the University of Groningen.

Rik Smit is a Senior Lecturer at the Center for Media and Journalism Studies, University of Groningen.