1. Introduction

With the launch of the digital euro project in July 2021, the Eurosystem has started the investigation phase to address key aspects related to the design and distribution of a potential digital euro. This paper proposes a framework to understand the impact of the introduction of a digital euro on the transmission of monetary policy via banks. The paper discusses the main transmission channels and, building on illustrative demand scenarios, presents impact ranges on lending depending on different degrees of pressure on bank funding.

To intermediate the distribution of central bank digital currency (CBDC), banks must obtain the necessary reserves and can undergo various adjustment channels. When their clients want to replace deposits with CBDC, banks must first obtain the digital euro from the central bank and then ‘resell’ it to the final holders, as is currently the case for banknotes. In doing so, banks pay the central bank with reserves and debit the bank account of the final holders. Specifically, banks can (i) draw down existing reserves with the central bank, potentially leading to inter-bank borrowing or increased competition for existing reserves (the latter could include deposit competition and the sales of assets to other banks or entities holding reserves); (ii) increase their borrowing from the central bank; (iii) sell assets to the central bank from their own portfolios; (iv) sell assets to the central bank on behalf of their clients; or (v) reduce their own holdings of banknotes. Which of these adjustment channels banks will use will depend on their preferences, the choices of customers, and the policies of the central bank.

Should some key frictions emerge, CBDC could have a material impact on banks’ intermediation capacity. The channels described above call for an adjustment of the central bank’s balance sheet, which necessarily avoids the emergence of a funding gap in banks’ balance sheets. In a frictionless economy, this implies a neutral impact of CBDC on banks’ maturity transformation and risk intermediation capacity. However, constraints and frictions are pervasive to our financial system: for example, central bank funding requires the use of collateral (which adds a cost for banks compared to deposit funding) and market stigma may limit banks’ willingness to keep borrowing from the central bank, weighing on the supply of bank loans. When significant and binding, market imperfections may result in CBDC having a material impact on banks and the monetary policy transmission through them.

Our results show that market reactions to public announcements surrounding the digital euro offer a blueprint of the potential impact of a CBDC in the euro area. Markets are sensitive to a perceived threat of deposit losses and responsive to communication that dampens their likelihood. The early responses of banks’ balance sheets to these market reactions are consistent with the adjustment channels and the potential frictions associated with a CBDC rollout mentioned above. For the exposed banks, the impact on lending conditions depends on bank funding conditions and the ease to access central bank funding in case of funding stress.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the mechanisms through which the introduction of a CBDC can affect bank lending. Section 3 details the empirical evidence on the impact of the potential introduction of a CBDC on bank lending. Section 4 discusses implications for the transmission of monetary policy via banks.

2. CBDC and bank lending: a primer

2.1 Potential impact on bank funding

Demand for CBDC holdings could, first of all, substitute for existing banknotes. That case, however, would merely represent a swap between two forms of central bank money in the hands of the public, with no impact on bank balance sheets or monetary policy transmission. In contrast, implications for bank funding conditions and, therefore, monetary policy transmission would arise in the case where CBDC holdings were to substitute for bank deposits. In that case, banks would need to first obtain the digital euro from the central bank and then ‘resell’ it to the final holders, as is currently the case for banknotes. In doing so, banks would pay the central bank with reserves and debit the bank account of the final holders.Footnote 1 In order to obtain the necessary reserves, banks could (i) draw down existing reserves with or (ii) increase their borrowing from the central bank. Should the central bank be willing to engage in actual purchases of assets, banks could also (iii) sell assets to the central bank from their own portfolios or (iv) sell assets to the central bank on behalf of their clients.Footnote 2

The central bank balance sheet identity, working through the mechanisms described above, would be in effect an aggregate consistency restriction that prevents CBDC from creating funding scarcity for the banking system as a whole. However, individual banks might opt for covering their lost deposits by increasing their reliance on interbank or bond funding or by competing for the existing deposits in the system. Banks would be more likely to turn to these options if excess reserves were to be highly concentrated in the hands of few banks or if the central bank’s operational framework were to favour a small amount of excess liquidity in the system. They might also prefer them if they were to believe that increasing their reliance on central bank funding would be negatively perceived by the markets.

Whichever the adjustment option, the new funding mix would be typically less favourable for banks than without CBDC. For instance, a one-to-one substitution of lost bank deposits with central bank funding would typically be relatively costlier, unless the central bank were to calibrate its funding facilities to perfectly replicate the pre-CBDC funding situation, for example, in terms of price, maturity and collateral requirements.Footnote 3 This is because lost deposits would typically consist of sight deposits, which in a positive interest rate environment tend to carry a lower yield than central bank funding.Footnote 4 Moreover, in order to obtain central bank funding, banks would need to incur collateral costs. Compliance with regulatory requirements could introduce an additional implicit cost, as household deposits tend to be considered a stable funding source for banks. In general, the cost of the new funding sources (which may also include increased recourse to the interbank or bond markets) would be substantially higher and more volatile than that of the lost depositsFootnote 5 and would likely increase banks’ exposure to market, liquidity and interest rate risk.Footnote 6

2.2 Potential impact on profitability and credit supply

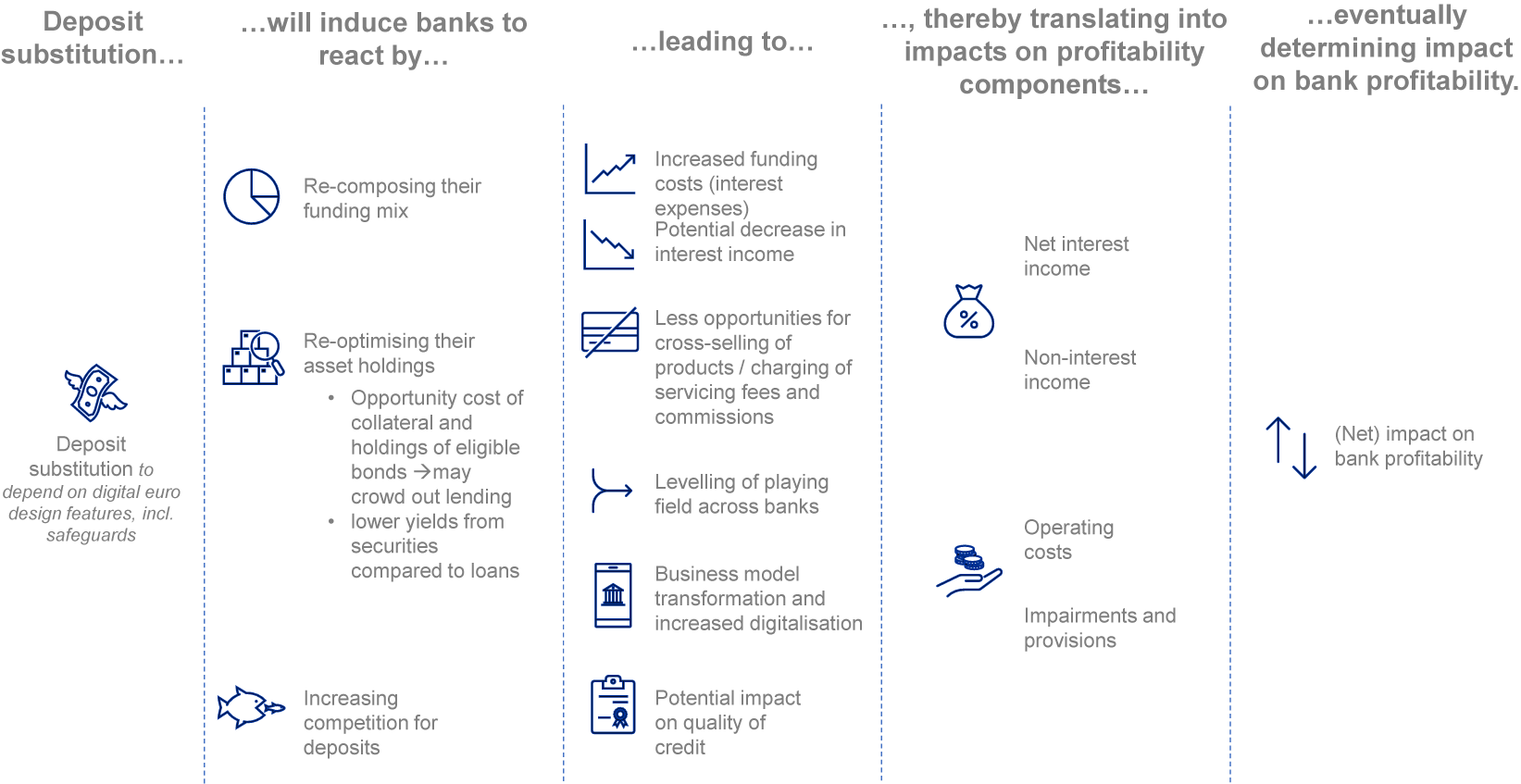

Beyond affecting banks’ funding mix, a CBDC could also induce banks to re-optimise their asset portfolios and business models, thus affecting their overall profitability via various channels (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1. Impact of a digital euro on bank profitability: underlying mechanics

First, a more expensive funding mix in response to CBDC could put pressure on profit margins, depending on bank adjustment strategies and the overall interest rate environment. The driving force at play would be the prevailing spreads between different funding sources and asset classes. The sign and size of these effects would also depend on the overall interest rate environment. For instance, should the interest rate on reserves be negative, banks would be disposing of a costly asset.Footnote 7 In the case where banks would resort to standing refinancing operations of the central bank subject to collateral requirements, their margins would also be affected through the accumulation of high-quality assets eligible as collateral, which normally are associated with lower yields compared to loans (see also Burlon et al., Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024). Margins would decrease further for banks choosing to complement central bank funding with recourse to wholesale funding.Footnote 8 At the same time, some banks may be able to compensate lost net interest income at least partly with other income sources and increased cost efficiency (see also Section 3.2 further below).

To the extent that a CBDC would induce a re-composition in banks’ market shares, income-generation sources and underlying asset and liability structures, it could affect their risk-taking behaviour and thus their impairments and provisioning costs. The introduction of a CBDC could attenuate or accentuate bank risk-taking, depending on modelling assumptions. In particular, any impact would depend on how banks and borrowers react to changes in the degree of competition in deposit and lending markets. For instance, Garratt et al. (Reference Garratt, Yu and Zhu2022) argue that a CBDC could heterogeneously affect the level of risk-taking for banks of different sizes, as the growing advantage of smaller banks in the deposit market would translate into an advantage in the lending market, which appears consistent with Boyd and De Nicoló (Reference Boyd and De Nicoló2005). Nonetheless, any shifts in risk levels on banks’ portfolios would be subject to constraints stemming from risk-based capital requirements, thereby depending on individual banks’ ability to sustain adequate capitalisation levels.

Taken together, the channels illustrated in Diagram 1 point to the fact that the final impact of a CBDC on bank profitability could be ambiguous and should thus be assessed in net terms.

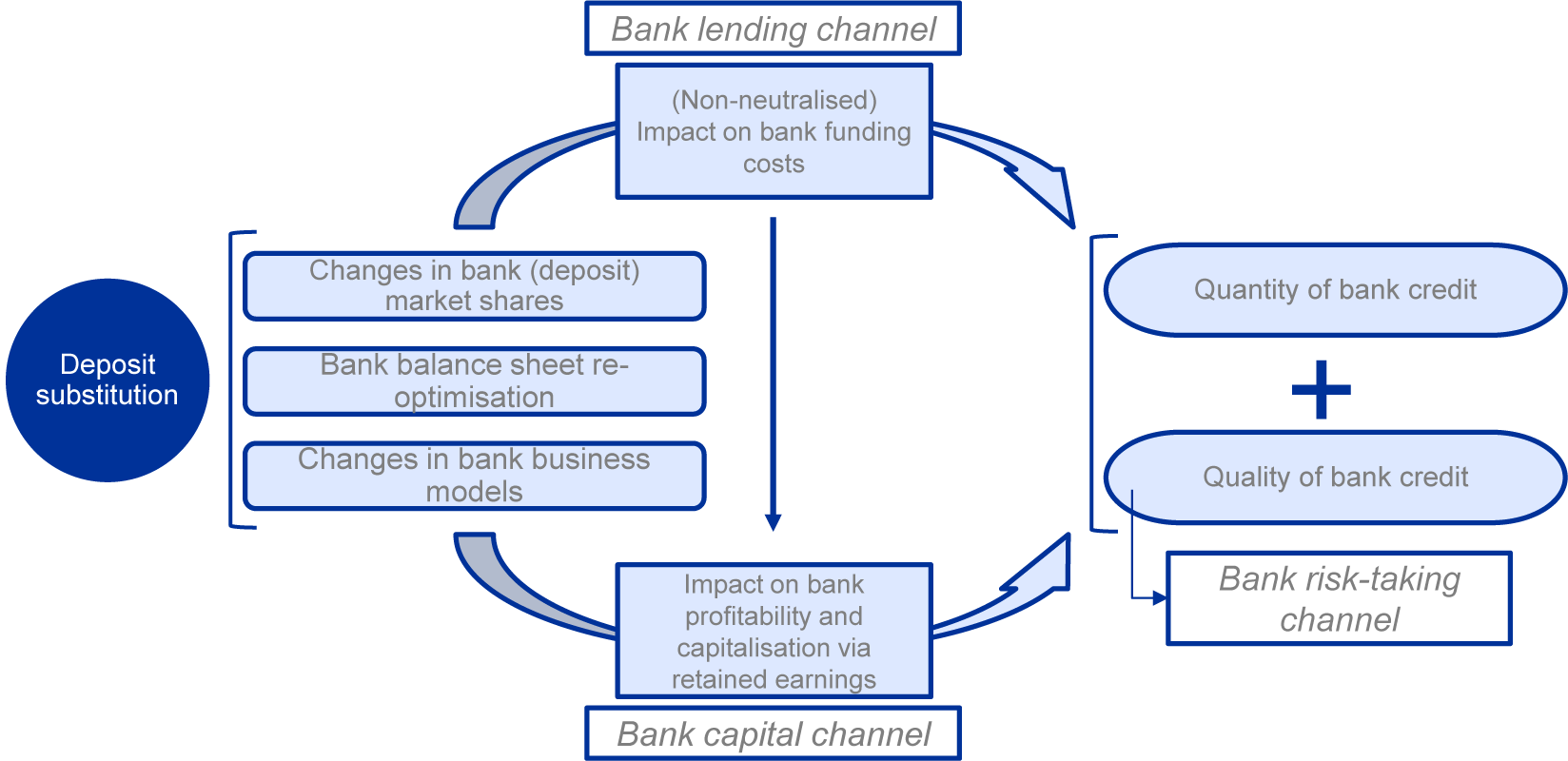

The above-discussed impacts of CBDC on bank funding costs and profitability will determine its effect on bank lending conditions (Diagram 2). To start with, banks could adjust their lending supply as part of their (immediate) reaction to deposit loss and to the costs attached to substituting lost deposits with non-deposit liabilities (‘bank lending channel’). If increased funding costs were to persist and (together with other components) feed into a negative net impact on bank profitability, capital requirements could become increasingly binding thus restricting banks’ intermediation capacity (‘bank capital channel’). Whether temporary or sustained, decreases in bank profit margins would increase the opportunity cost of each unit of lending. Uncertainty about further deposit substitution in the future, and its impact on bank profitability, would attenuate these channels. In parallel, banks might also adjust their risk tolerance in response to a decline in their profit margins, thus changing the composition of lending (‘risk-taking channel’).

Diagram 2. Impact of a digital euro on bank lending conditions: underlying mechanics

3. Evidence on the impact of CBDC on bank lending

3.1 Data and empirical strategy

Our analysis combines several data sources. Central to the study of the effects of CBDC on bank credit provision is loan-instrument-level data from AnaCredit—the euro area corporate credit register. We measure banks’ lending activity by using, for each loan instrument, nominal amounts outstanding collected at a monthly frequency since September 2018. We also extract information on borrower size, sector of economic activity and location. Thanks to the granularity of this information, we are able to disentangle credit supply and demand when evaluating the reaction of lending volumes to exposure to a negative ‘CBDC shock’ (see below). We do so by saturating our model with a collection of fixed effects that span the main dimensions of demand components, that is, the so-called industry–location–size (henceforth ILS) fixed effects, see Degryse et al. (Reference Degryse, De Jonghe, Jakovljević, Mulier and Schepens2019).

We merge AnaCredit to bank-level balance sheet data from iBSI (individual Balance Sheet Items statistics), which allows us to obtain information on individual banks’ asset and liability composition. We also merge into our dataset bank-level CDS (credit default swap) data, as provided by ICE (Intercontinental Exchange, formerly Standard & Poor’s Credit Market Analysis). Importantly, we further complement our database with daily data on stock returns sourced from LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group) Eikon (formerly Refinitiv), which captures 134 banks from 1 January 2007 to 31 May 2021. This information allows us to derive our measure of ‘CBDC shock’, by mapping it to important daily events related to digital euro, which are distributed over 2020 and 2021.Footnote 9 These events have little to no overlap with monetary policy announcements, which facilitate the interpretability of the stock market responses.

We apply the methodology of Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024) and fit a standard 3-factor Fama–French model to euro area banks’ stock market returns, in order to isolate abnormal stock market returns related to digital euro news, and we then calculate cumulated daily abnormal returns for each bank vis-à-vis October 2020 (‘CBDC shock’). The obtained shocks are further aggregated at the month level and are then merged back into the dataset described above.

We organise our analysis into three parts. First, we ask whether exposure to a negative CBDC news shock as of October 2020 bore an impact on banks’ balance sheet items, and if so, whether such adjustments were consistent with the theoretical underpinnings described in Section 2 above. We do this by estimating impulse response functions for individual banks’ main balance sheet items (expressed as ratios to main assets) to exposure to bank-level cumulated CBDC news shocks using local projection models, see Jordà (Reference Jordà2005). We allow for delayed responses up to 12 months. We saturate our specification with bank and country-time fixed effects as well as (lagged) time-varying bank-level controls.

Second, we expand the analysis of Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024) and investigate whether individual banks’ stock returns declined significantly more strongly and in addition became systematically more volatile for banks more reliant on deposit funding. We do so by running a series of bank-specific regressions at daily frequency. First, for each bank, daily excess returns are regressed on the daily market excess returns, a dummy for the period October 2020 to January 2021, and their interaction. We then group the estimates of the interaction coefficients on the basis of each bank’s deposit ratio (above/below the median). Second, we use the same model in a panel setting, with individual banks’ daily excess returns regressed on the (triple) interaction between daily market excess returns, a dummy denoting the period October 2020 to January 2021 and a dummy for banks with a deposit ratio above the median, together with bank and day fixed effects.

Third, we expand the analysis of Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024) and investigate whether the impact of a CBDC shock on lending supply differs, depending on individual banks’ ability to resort to alternative sources of funding. We focus on the reaction of lending between October 2020 and January 2021. We then adjust our empirical model as follows:

Where

![]() $ {\varDelta}^3\log {(Volume)}_{b,f} $

is the percentage change of outstanding amounts of loans between bank

$ {\varDelta}^3\log {(Volume)}_{b,f} $

is the percentage change of outstanding amounts of loans between bank

![]() $ b $

and firm

$ b $

and firm

![]() $ f $

that occurred in the 3 months after October 2020 (i.e., up to January 2021),

$ f $

that occurred in the 3 months after October 2020 (i.e., up to January 2021),

![]() $ {\hat{\varGamma}}_b^{October\;2020} $

is our treatment variable defined as the (cumulated) abnormal returns as of October 2020,

$ {\hat{\varGamma}}_b^{October\;2020} $

is our treatment variable defined as the (cumulated) abnormal returns as of October 2020,

![]() $ {dummy}_{below} $

and

$ {dummy}_{below} $

and

![]() $ {dummy}_{above} $

are dummies that split observations for a given bank characteristic (below and above the median respectively),

$ {dummy}_{above} $

are dummies that split observations for a given bank characteristic (below and above the median respectively),

![]() $ {X}_b $

and

$ {X}_b $

and

![]() $ {X}_f $

are bank and firm controls respectively, and

$ {X}_f $

are bank and firm controls respectively, and

![]() $ {\alpha}_{i,l,s}^3 $

are the ILS fixed effects described above. Similarly to Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024), we cluster standard errors at the bank level.

$ {\alpha}_{i,l,s}^3 $

are the ILS fixed effects described above. Similarly to Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024), we cluster standard errors at the bank level.

We complement the results above by identifying past CBDC-like events in bank level data spanning from the early 2010s till today and mapping them to 3-months-ahead responses of lending supply via a weighted panel regression. We identify these events via a treatment dummy that takes the value of 1 if, in the previous 3 months, a bank has experienced a significant (above a standard deviation) outflow of overnight retail deposits paired with either an outflow of excess liquidity, an increase in central bank funding or an outflow of securities holdings. Affected and unaffected banks that are similar in all relevant characteristics besides the CBDC-like event are sampled by means of propensity score matching techniques. Once again, we saturate the specification with bank- and country-time fixed effects and (lagged) bank-level controls.

We report the results aiming to guide our reply to each question in the following sections.

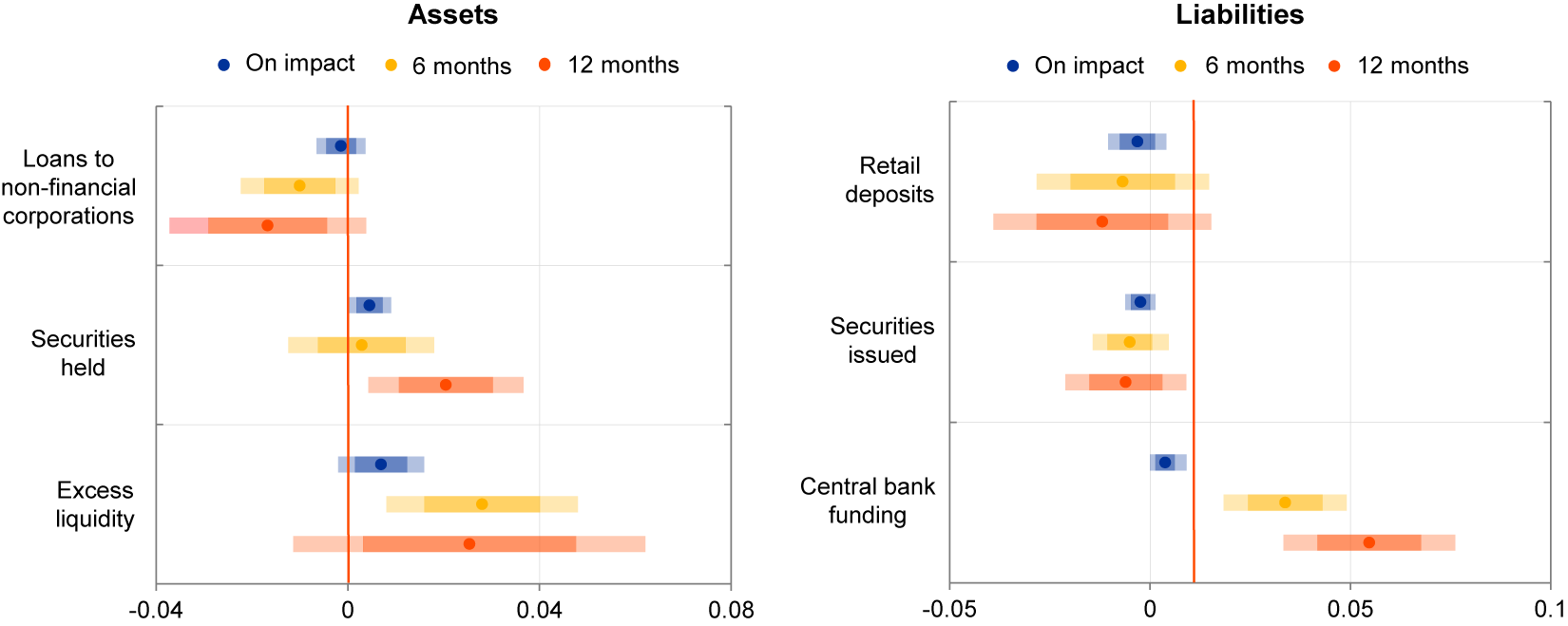

3.2 Impact on bank funding and balance sheets

Results to the first question are documented in Chart 1. We find that banks that were more exposed to a negative CBDC news shock accumulated more collateral and resorted more to central bank funding where possible, increasing their excess liquidity holdings. At longer horizons, the negative shock diminished their ability to tap market funding, potentially exerting mild pressure on the loan portfolio. These early responses of banks’ balance sheets to these market reactions are consistent with the adjustment channels associated with a CBDC rollout mentioned above. These impacts also explain economically significant portions of the changes in these balance sheet items and persist despite being net of confounding factors related to other bank characteristics, bank unobserved heterogeneity and country-specific developments. Yet, the eventual impact on funding costs was contained against the backdrop of overall favourable financing conditions and the availability of central bank funding over the time period included in the sample.

Chart 1. Impact of negative CBDC news on euro area banks’ assets and liabilities.

Notes: In percentage points of ratio to assets for 1 p.p. drop in stock prices. Light shaded areas report the 90% confidence intervals, dark shaded areas report the range of plus/minus one standard deviation with robust standard errors.

3.2 Estimating impact on bank profitability

Measuring the potential impact of a future rollout of CBDC on banks is challenging because of the lack of comparable experiences. For instance, at this stage, there are only two jurisdictions which have rolled out a CBDC (Bahamas and China). However, insights can be gained from investor reactions to public announcements surrounding the digital euro. Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024) show that abnormal fluctuations in stock market returns linked to digital euro announcements can shed light on the expected impact of a CBDC rollout on banks and their expected profitability.

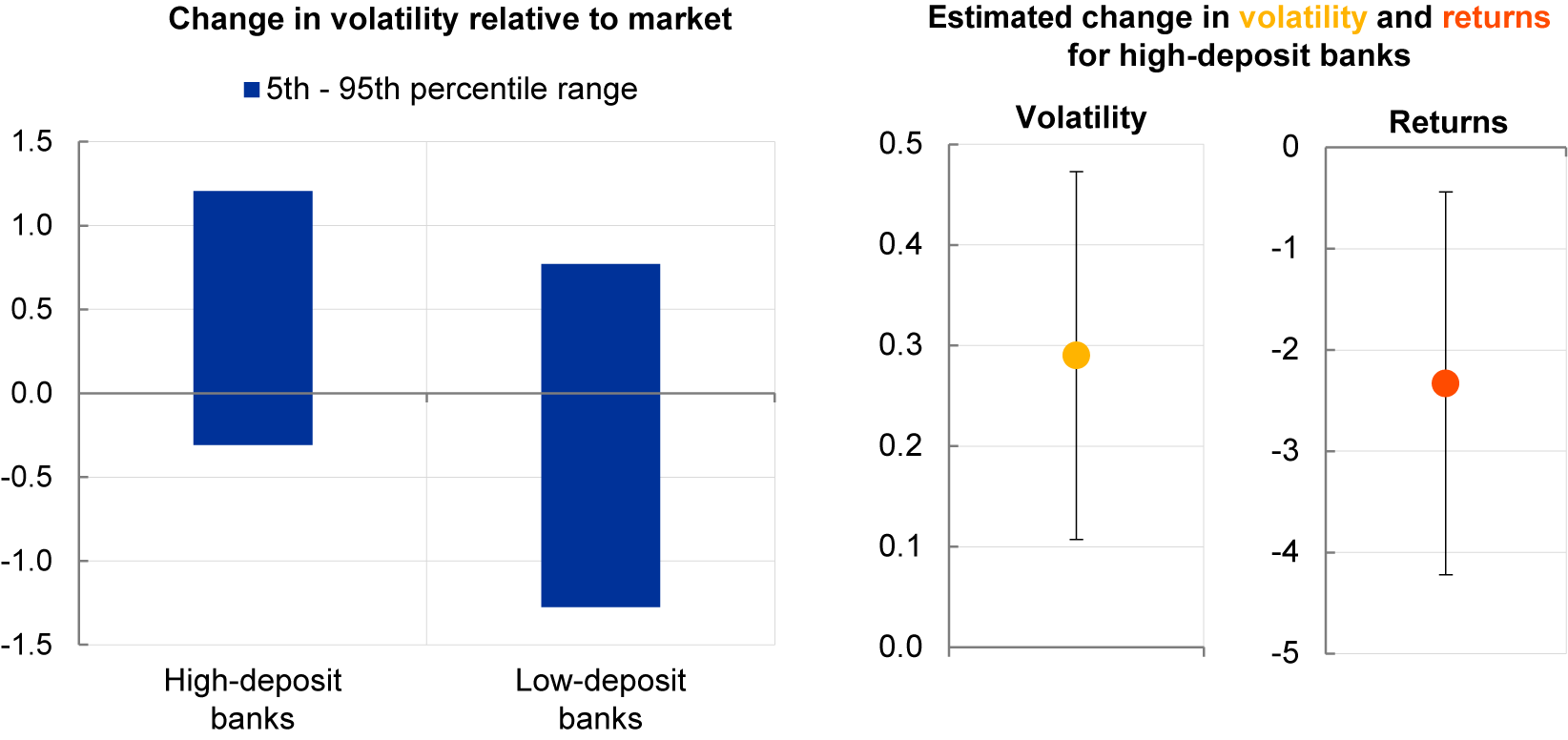

We build on this work and show that, after the publication of the ECB report in early October 2020, stock prices of banks more reliant on deposit funding declined more strongly and in addition became more volatile than those of low-deposit banks (Chart 2). Stock developments therefore hinted at a split between banks perceived to be more exposed to the new technological threat, like those relying more on deposits, and other banks. These movements were however temporary: stock prices recovered fully as soon as more details on the actual design and timing of the project were made public.

Chart 2. Reaction of bank stocks to digital euro communication (October 2020 to January 2021).

Notes: In deviations from bank-specific betas (lhs and middle panels) and percentage points (rhs panel). Error bars in the middle panel report the 90% confidence interval, with underlying standard errors two-way clustered at the bank and day level. The rhs panel reports the coefficient from Table 1, column 5 of Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024), rescaled by the difference in average deposit ratio between high- and low-deposit banks. Error bars report the 90% confidence interval based on the standard errors reported in the same table.

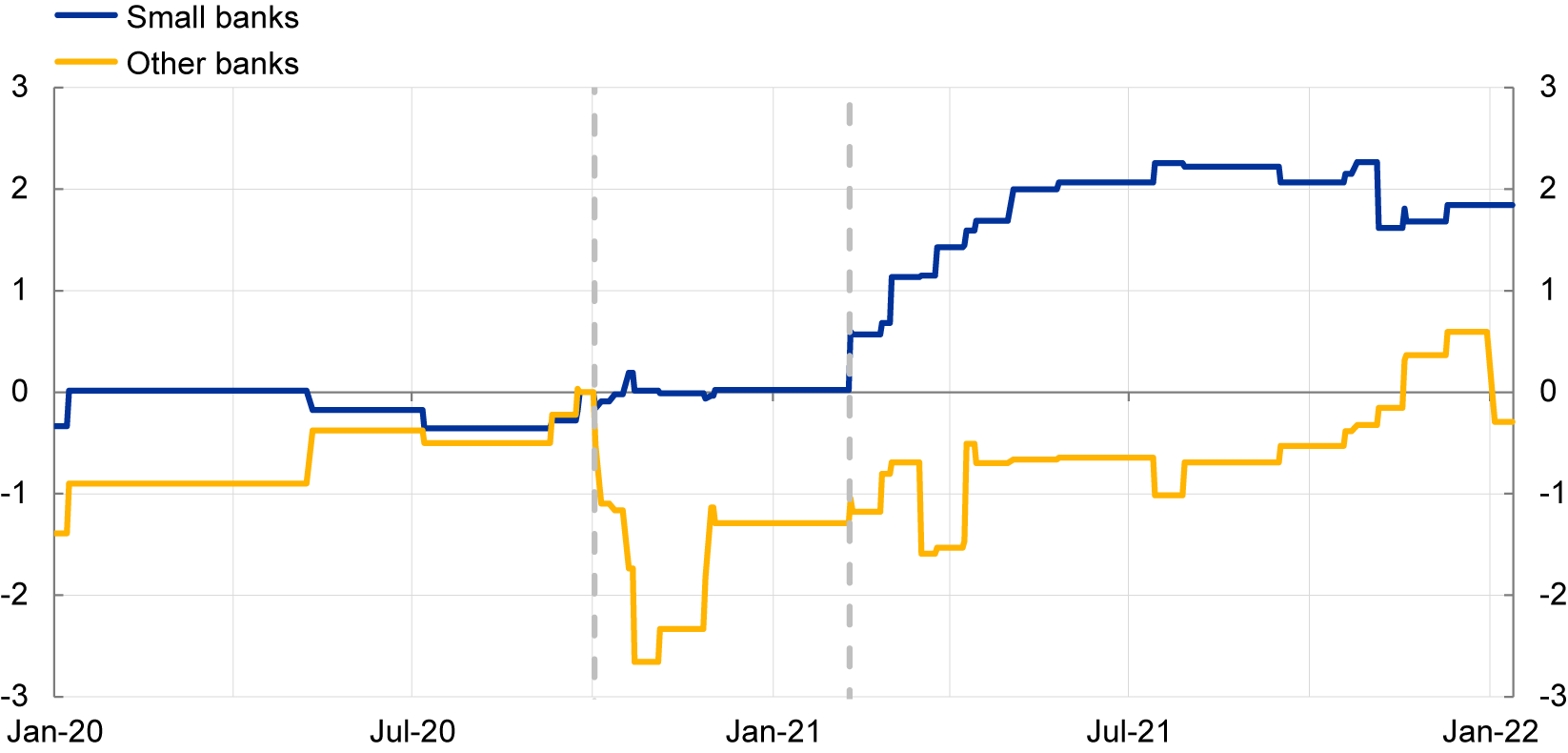

We then investigate cross-bank variation by splitting banks by size. We find that stock market returns associated with digital euro news rose to levels almost 2 p.p. higher for small banks than for other banks in the months following October 2020 (Chart 3). We then link this result to the work of Adalid et al. (Reference Adalid, Álvarez-Blázquez, Assenmacher, Burlon, Dimou, López-Quiles, Martín Fuentes, Meller, Muñoz, Radulova, Rodriguez d’Acri, Shakir, Šílová, Soons and Ventula Veghazy2022) and interpret this as connected to the fact that some business models might be perceived by markets as more posed to benefit from the introduction of the digital euro in net terms, while others are more posed to lose.

Chart 3. Change in stock market returns associated with CBDC news by bank size.

Notes: In percentage points, cumulated, 1 October 2020 = 0. Small banks are the ones in the first quartile of the distribution of banks by market capitalisation. The two vertical lines indicate the publication of the ECB report on the digital euro on 2 October 2020 and the speech by F. Panetta on 10 February 2021.

From this perspective, the results demonstrate that, if well managed, the digital euro could be a considerable support toward the digitalisation of the euro area banking sector, levelling the playing field for smaller banks. In this context, it is useful to consider smaller banks to represent a mix of less diversified business models: specialised and retail lenders. While the two business models are in principle different in terms of business activities, they both heavily rely on customer acquisition and relationship management business strategies fit to serve a more traditional clientele (e.g., number of branches and employees). In addition, both bank business models have structurally exhibited an overall lower adaptability to changes in the policy environment, which has resulted in an underperformance in terms of cost-efficiency and profitability over time compared to more diversified bank business models. A digital euro could thus incentivise these banks to intensify efforts to digitalise their services and re-optimise their cost structure, including their branch (and ATM) network. The latter would be particularly relevant in the case of retail lenders. For this business model in particular, further modifications in banks’ fee and income structure should also be considered. On one hand, there might be cases where individual depositors might completely withdraw their funds upon the introduction of a digital euro (extensive margin), whereby these banks would lose opportunities to charge fees for cross-selling of services (e.g., transfers, exchange rate conversions) and products (e.g., card insurance) closely connected with the deposit franchise.Footnote 10 On the other hand, however, a digital euro could offer these banks new business opportunities in the form of value-added services, while allowing them to exploit synergies with their already-existing products, for example, costs related to onboarding, and so on (provided that a digital euro would be account- and not token-based). This could bear the potential to increase business model sustainability for these banks amid changing payment preferences and increasing competition from digital players.

The evidence thus suggests that the real counterfactual weighing on long-term bank profitability is a world where technological innovation and leverage on network effects would bring about a prominence of larger banking conglomerates or even new players such as big tech firms. In such an environment, banks would face deposit competition from private players targeting access to transaction data and therefore to the possibility to either promote their own products or services or to do so in collaboration with third parties (Agur et al., Reference Agur, Ari and Dell’Ariccia2022). Especially in the payment market, network effects and the monetisation of payment data can create market power and inefficiencies (e.g., Garratt and Van Oordt, Reference Garratt and Van Oordt2021). More broadly, a counterfactual market dominated by privately-issued crypto-currencies such as stablecoins could render the transmission of monetary policy impulses less effective (Cova et al., Reference Cova, Notarpietro, Pagano and Pisani2022).

3.4 Estimating impact on bank credit supply

Burlon et al. (Reference Burlon, Muñoz and Smets2024) have documented a link between the CBDC news shocks presented in Section 3.1 above and bank credit supply by showing a significant, partially transitory, impact of these shocks on bank loan volumes to firms.Footnote 11 While the analysis focuses on the immediate differential reactions across banks upon learning about a digital euro, it provides important information about the channels of transmission that would be relevant upon a potential introduction. In particular, it highlights (lower) expected bank profitability as the channel at work in the transmission of an introduction of a digital euro to bank lending conditions. We expand on this work, and zero in on bank funding conditions.

To capture the degree of favourability of bank funding conditions, we exploit variation across banks in terms of excess liquidity, collateral availability and market confidence.Footnote 12 These dimensions can also be seen as representing specific frictions and constraints—in the event where they would become binding—such as during market stress. We show that banks with a lower ability to resort to alternative sources of funding, or facing overall less favourable funding conditions, would be expected to adjust their lending supply more substantially in response to deposit loss (Chart 4, left-hand side chart). In particular, the weakening in lending dynamics in the months following the publication of the ECB’s digital euro report in October 2020 is significant only for banks that have lower liquidity buffers, and enjoy lower market confidence, while it is also of higher magnitude for banks that have less collateral.

Chart 4. Response of lending volumes to exposure to a negative CBDC shock and to a negative CBDC-like event.

Notes: In percentages of ex-ante volumes. The error bars report the 90% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the bank level (lhs chart) and on robust standard errors (rhs chart).

These findings are corroborated also when using historical developments in banks’ balance sheets that resemble the dynamics expected upon the rollout of a CBDC (Chart 5, right-hand side chart). Similarly to the impacts identified with CBDC-news shocks, the slowdown in lending related to these historical events was relatively stronger for banks with lower excess liquidity, more binding collateral constraints and lower market confidence possibly hindering their willingness to increase their borrowing from the central bank in case of funding stress. Different structural shocks may be underlying developments classified as CBDC-like. At the same time, resulting correlations with bank balance sheet items serve as a useful guidepost to further validate quantitatively the impact of the CBDC-news shocks identified via market reactions to official communication on the digital euro project. In particular, the consistency between the results obtained for exposure to a negative CBDC-shock and to a CBDC-like event suggests that, if the introduction of the digital euro were to cause a deviation of bank funding conditions from those consistent with the central bank’s desired monetary policy stance, it would bear impacts that would not be intrinsically different from those following a standard bank funding shock. This notwithstanding, it should be distinguished from other types of bank funding shocks, in that the central bank—being the issuer of the CBDC itself—could control ex-post or ex-ante the extent to which it allows the CBDC introduction to affect its desired stance and the transmission of its policies (see Section 4).

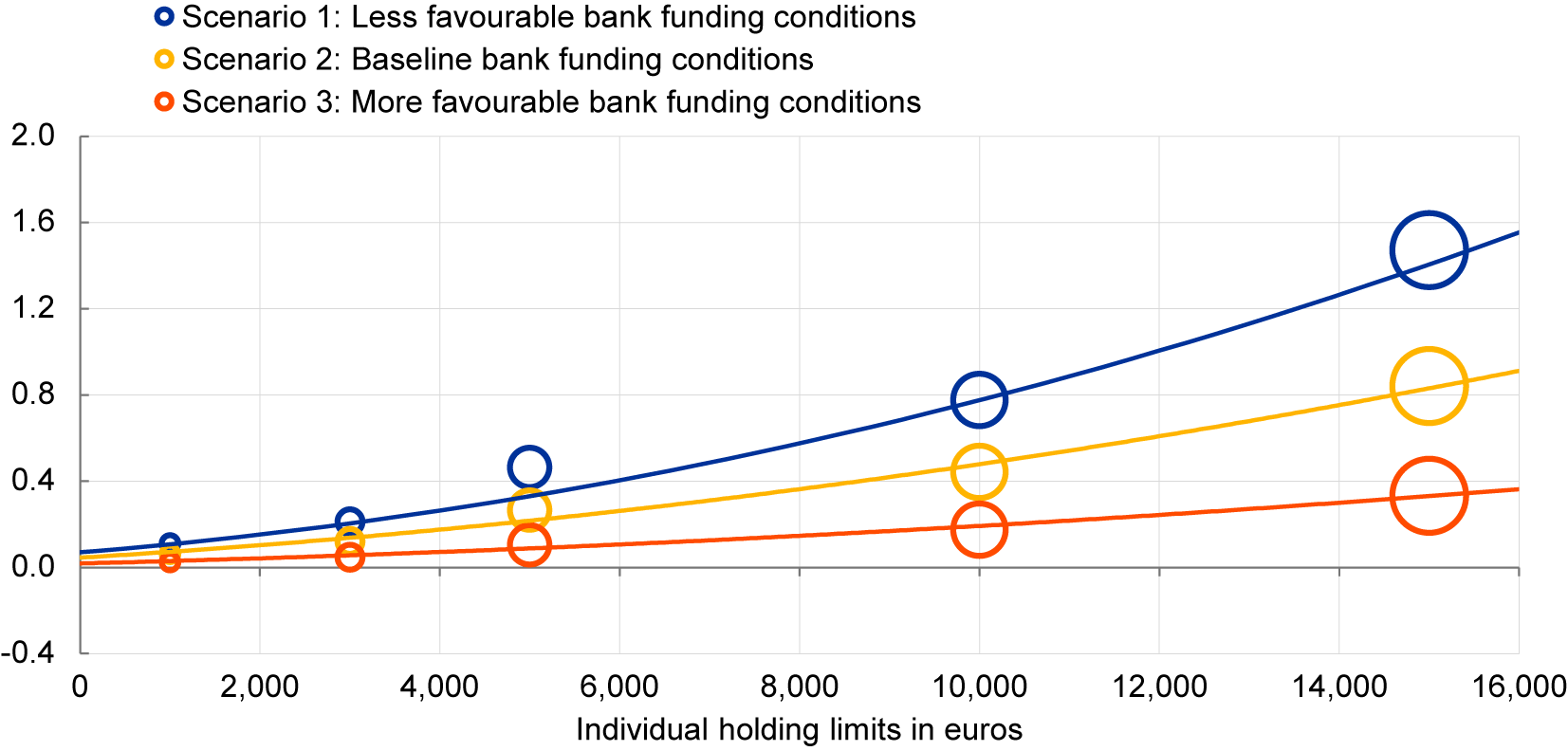

We then take a step further and illustrate the link between bank funding and lending conditions for different possible levels of digital euro holdings. Similarly to the other exercises in this paper, this exercise abstracts from any policy action that could be pursued by the central bank within its objective of maintaining price and financial stability. We also note that the eventual digital euro holdings (i.e., digital euro account balances) need not be necessarily equivalent to the digital euro take-up (i.e., total demand, including for transactional purposes). This notwithstanding, they would be dependent on similar factors, such as payment preferences at the time of issuance and the design features of the digital euro, notably the existence of safeguards and (reverse) waterfall functionalities.

We document the results of this exercise in Chart 5. We show that larger overall digital euro holdings are in principle associated with more pronounced impacts of a digital euro on bank lending conditions, as measured by bank lending rates. In addition, and unsurprisingly, lending rates tend to respond more sharply to given (average) digital euro holdings within environments of comparably less favourable bank funding conditions.

Chart 5. Response of lending rates to exposure to a negative CBDC shock under different scenarios of bank funding conditions favourability.

Notes: In percentage points per annum, with size of bubbles denoting size of aggregate CBDC take-up.

4. Implications for the transmission of monetary policy via banks

Bank funding conditions and potential profitability effects are the main channels through which CBDC could have a bearing on monetary policy transmission via banks.

In principle, and if warranted by the size of the CBDC impact, the central bank could play an active role in avoiding that the introduction of a CBDC causes a deviation of bank funding conditions from those consistent with its desired monetary policy stance. Such a deviation could arise from unwarranted frictions in money markets, imperfections in bond markets or excessive competition for customer deposits. To prevent or neutralise those impacts, the central bank could take specific action. For instance, the central bank could increase the attractiveness of its lending operations or could also use asset purchases to engineer an exogenous increase in the supply of reserves in the system. In the extreme, it could even adjust its policy rates, should it deem it necessary to do so.

At the same time, achieving full neutrality may pose significant challenges. For instance, if pursued via lending operations, the central bank would need to fully replicate the conditions at which banks were funding themselves prior to the introduction of the CBDC. In particular, the central bank could try to replicate the quantity, pricing and (empirical) maturity of the pre-CBDC bank funding mix, also taking into account the implicit cost of collateral requirements (Brunnermeier, Reference Brunnermeier2019; Castrén, Reference Castrén2022; Fegatelli, Reference Fegatelli2022; Niepelt, Reference Niepelt2020). It would also need to consider any impact that a different regulatory treatment of central bank borrowing compared to deposits might imply for banks’ compliance with (and distance from) prudential and regulatory requirements (Fegatelli, Reference Fegatelli2022). Other aspects would include stigma and the possibility of precautionary excess liquidity accumulation by banks due to uncertainty about CBDC take-up and central bank funding availability in the future. The central bank could address these effects through effective communication, for example, by committing to provide additional funding, whenever that would be needed, for banks to cover emerging funding needs stemming from the introduction of a digital euro.

Against this background, the central bank may prefer to minimise ex ante the size of CBDC holdings and thus the need and scope of active neutralising interventions ex post. Structurally, this could be naturally achieved via a design that fosters the payment function of CBDC as opposed to its potential role as storage of value. This could be achieved by integrating into the CBDC functionalities that favour the transferability of funds between bank deposits and the CBDC wallet. Waterfall functionalities like those currently considered by the ECB can prove to be instrumental in this respect. A CBDC remuneration that does not compete with bank deposits would also be conducive to keep CBDC balances at a contained level. In addition, the central bank can also set explicit safeguards, such as holding limits. By capping the individual (and thus the overall) take-up, the risk of a large deposit substitution would be avoided under any circumstances, including moments of market stress that could exacerbate the demand for CBDC as storage of value.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carlo Altavilla, Rhys Bidder, Miguel Boucinha, Costanza Rodriguez D’Acri and participants to the NIER Workshop on Central Banking for useful comments and suggestions. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Any views expressed are only those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the ECB or the Eurosystem.

Competing interest

The author(s) declare none.