Introduction

Following the collapse of empires and two world wars, state borders were redrawn over existing populations in ways that did not create congruent political and national communities. Nation-states have since engaged in majoritarian nation-building to entrench power and domination over their ethnically diverse populations. Groups excluded from the titular national identity become targets of nation-building for a particular purpose — assimilation, accommodation, or exclusion (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012). Transborder ethnic populations sharing kinship ties to kin-states are at a heightened risk of being construed as threatening to home states, triggering minority securitization. Split by international borders, transborder ethnic kin groups are not a rare phenomenon challenging a few states but a ubiquitous reality where new nation-states established their borders in place of former empires. The Transborder Ethnic Kin dataset (EPR-TEK 2021) identifies 144 transborder ethnic kin groups that have been politically relevant at some point since 1946 (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015b).

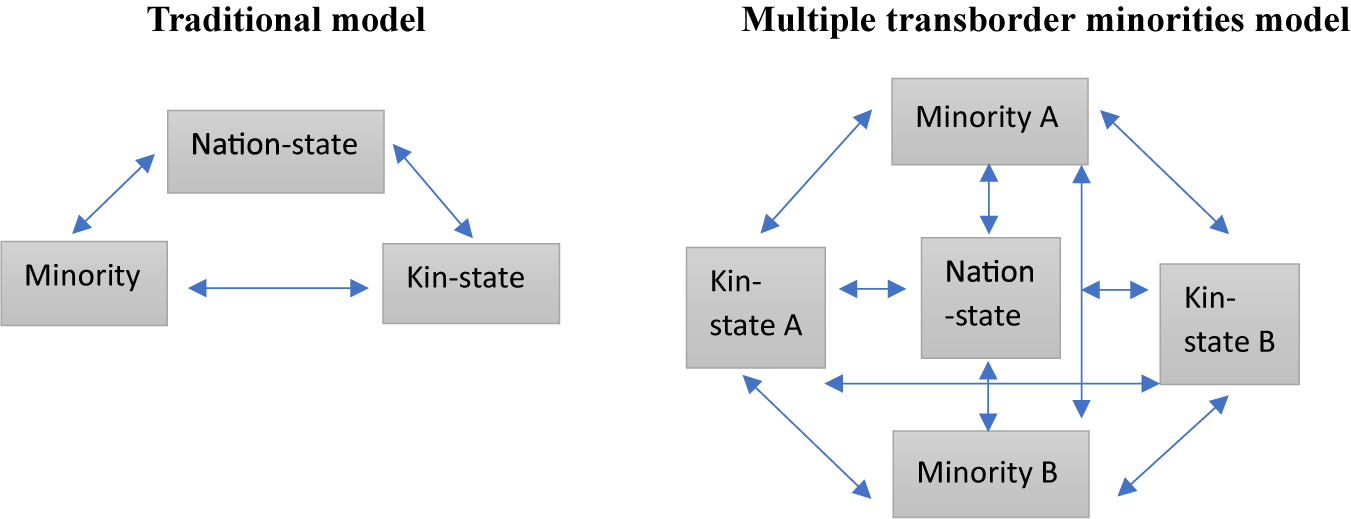

Research on state-minority relations in these settings has followed the traditional theoretical model of a nation-state–ethnic minority — kin-state, also known as the “triadic nexus” approach outlined by Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996). This article builds on and adapts the logic of the traditional model to the more complex interrelations of nation-states with multiple minorities and their kin-states to understand variation in the treatment of minority populations. Specifically, it examines the differential effects of minority frames used for advancing nation-building and minority responses and how the state instrumentalizes these responses to create securitized “fifth columns” of some minorities and “model minorities” of others. By applying the more complex relational lens, we notice that nation-builders can benefit from having to deal with multiple minorities, harnessing the challenging reality of ethnic demography and regional security to the service of nation-building.

Titular political elites deploy these frames when they seek to reproduce ethnic differences and reinforce the primacy of the state-owning nation. Strategic frames advance a critically important narrative of a system of rewards and punishments toward each minority community. By assigning minorities competing roles as “model minorities” versus “fifth columns,” nation-builders accomplish two aims: (1) Maintain nation-building policies and practices upholding the dominant status of the titular nation by discrediting ethnic minority claims for major institutional changes. Contradictory framing of minority populations enables titular political elites to brand one minority as a success case and another one as a failure within the same institutional structure. Rather than resulting from structural disadvantage, ethnic discrepancies are ascribed to minority individual and collective attributes and practices. Framing one minority as a model minority advises the “other” minorities to emulate it to build trust and positively affect their political outcomes. Accordingly, minority demands for institutional changes, such as removing structural barriers and reducing majority dominance, are dismissed; and (2) Titular political elites legitimize differential treatment of ethnic minorities in accordance with what they consider to be in their national interest at a particular time. Minorities construed as “fifth columns” are excluded from centers of power, while “model minorities” are afforded some recognition. At times of regional security crisis, these frames can be rapidly transformed within the same narrative of a system of reward and punishment for loyalty and obedience to consolidate the titular elites’ power. These stereotypes can further serve majoritarian nation-building by drawing a wedge between formidable minority alliances or deterring minorities from mobilization.

This theoretical expectation is tested on a paired comparison of Lithuania vis-à-vis Russian speakers and Poles and the Kyrgyz Republic vis-à-vis Russian speakers and Uzbeks. Both countries are small nation-states with comparable transborder minority populations that are the co-ethnics of powerful kin-states with whom these states have had a troubled past — Poland, the Russian Federation, and Uzbekistan. During the formative nation-building period, Lithuania and the Kyrgyz Republic institutionalized a privileged position for members of the titular nation. At the same time, both states extended rights to ethnic minorities and developed a national identity based on shared citizenship for all ethnic communities. Nation-building policies toward minorities have varied within and across cases over time. Initially, Lithuania targeted Poles with greater exclusion than the Russian speakers. Russia’s revisionist kin-state politics reversed state treatment of these communities, leading to the inclusion of Poles in the government and accommodation of their longstanding demands alongside rapid securitization of Russian speakers as potential fifth columns. The Kyrgyz Republic granted Russian speakers collective rights in the form of official language and education, whereas Uzbeks were targeted with exclusionary policies. Following a violent conflict in 2010 and the rise of Kyrgyz nationalism, Russian speakers lost their privileged status while the Uzbeks became heavily securitized as a community representing a collective security threat.

Nation-building in states with multiple transborder minorities

Nationalism, ethnic conflict, and irredentism scholarship have examined different factors contributing to nation-states’ development of policies toward ethnic minorities. One line of research has focused on representative institutions, electoral system design, and institutional design to account for the different treatment of ethnic minorities (Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; McGarry and O’Leary Reference McGarry, O’Leary, McGarry and O’Leary1993; Schertzer Reference Schertzer2018; Talal Reference Talal2022, Reference Talal2023). A rich body of literature has helped us understand the structural conditions that led some states to adopt a more exclusionary form of nationalism, while others recognized some degree of ethnic diversity. Formative nation-building projects played a central role in creating a path dependency in the foundational principles of the nation-state (Tudor and Slater Reference Slater2021). For this reason, the selection of initial policy trajectories toward minorities during this formative period received special scholarly attention (Laitin Reference Laitin1998; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Frye Reference Frye2010). Another influential stream of research points to minority characteristics, motivations, and mobilization to explain variation in their treatment (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000; Posner Reference Posner2004; Cramsey and Wittenberg Reference Cramsey and Wittenberg2016; Jenne Reference Jenne2007). Scholarship combining structural and agency-based explanations directs our attention to how ethnic minority organizations navigate the opportunities and constraints presented by macro structures (Vogt Reference Vogt2019; Csergő Reference Csergő2007).

Structural and minority-focused literature offers parsimonious explanations for nation-states’ initial policy choices toward different minorities. However, because these explanations hinge on relatively invariable characteristics of the initial structural conditions or minority demographic attributes that change rather slowly, they cannot account for variation in nation-building policies over time. Recent comparative research has found that there is an important temporal variation in state-minority relations, which we know much less about. The critical question underlying these debates relates to the content of nationalism at a particular time. One recent example is Akturk‘s (Reference Aktürk2012) influential study of persistence and change in nation-building policies in Germany, the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation, and Turkey. According to his typology of regimes of ethnicity, dominant political elites can seek to entrench a particular ideal type of regime: anti-ethnic, mono-ethnic, or multiethnic regimes. During the formative moments of nation-building, those in power entrench a particular regime of ethnicity, which stays in place over time (Tudor and Slater Reference Slater2021) until new hegemonic majorities or counter-elites succeed in institutionalizing a new regime of ethnicity (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2012).

Turning attention to external factors, scholars have pointed out the influence of kin-states and inter-state relations on state-minority relations (Jenne Reference Jenne2007; Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012). A kin-state represents the “majority nation of a transborder ethnic group whose members reside in neighbouring territories” (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2020). Kin-states may represent legitimate interests in protecting threatened kin or seek to mobilize their transborder kin against their home states (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2020; Csergő and Goldgeier Reference Csergő, Goldgeier, Tristan James, John, Margaret and Brendan2013). Populist and ethnonationalist political elites in home-states may play up cross-border ties with kin-states to allege minorities are “fifth columns” – enemies within who work to subvert the popular will with the external backing of a hostile kin-state (Radnitz and Mylonas Reference Radnitz, Mylonas, Mylonas and Radnitz2022).

Rogers Brubaker’s groundbreaking work on the triadic nexus highlights the relational nature of the interaction between nation-states, transborder minorities, and kin-states (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996). The fields are contested from within and advance antagonistic nationalism toward each other. Smith (Reference Smith2002) offered an important contribution to Brubaker’s framework, making it into a “quadratic nexus” in the European context where international organizations constitute another key dimension in shaping national questions. The underlying logic of these relational approaches to nationalism is that the interrelations between these fields are endogenous processes. Repeated interactions between the state and minority actors can, at times, spiral to violence, as was the case during the second Palestinian Intifada (uprising) in Israel (Rekhess Reference Rekhess2002), or normalize and de-securitize minority political mobilization, as is in Romania vis-à-vis the Hungarian minority (Stroschein Reference Stroschein2012). Taking endogeneity seriously has ripped benefits for a better understanding of state-minority relations and the change in state treatment of ethnic minorities over time.

In nation-states with more than one ethnic minority, tracing these relational interactions is significantly more complicated. The empirical reality of cases as diverse as Lithuania, India, Thailand, and Sudan raises the question of whether the current triadic nexus approach can seamlessly travel from a nation-state with one substantial ethnic minority to one with multiple minorities. Research on nation-states with two transborder minorities typically focuses on one minority at a time, such as the civic and political participation of Lithuania’s Poles (Gudžinskas Reference Gudžinskas2017) or Lithuanian Russian speakers (Potashenko Reference Potashenko2010), or Russian speakers in all three Baltic states (Agarin Reference Agarin2010), but not on the interactive effects between the state and multiple minorities within it. There are also notable exceptions, such as Han and Mylonas’s (Reference Han and Mylonas2014) research on China’s policies toward its minorities. Foreign relations with external actors are at the heart of their explanation of China’s decision to accommodate, assimilate, or exclude various minorities.

In settings with two transborder minorities, the additional relational fields require adapting the theoretical model. Instead of the interrelations between three fields - nation-state, ethnic minority, and its kin-state, forming three dyads (nation-state—minority; nation-state—kin-state, minority—kin-state)—we have five actors, forming ten dyads. These relations are depicted in Figure 1, and they include nation-state—minority A; nation-state—minority B; nation-state—kin-state A; nation-state—kin-state B; minority A—kin-state A; minority B—kin-state B, as well as four dyads that do not exist in the classical setting: minority A—minority B; minority A—kin-state B; minority B—kin-state A; kin-state A—kin-state B). The latter four dyads represent secondary relations to the central triad, and as such, may not be of utmost importance. Nevertheless, they are theoretically possible and may become relevant in certain cases. This includes situations in which minorities A and B form strong political alliances to achieve greater state concessions or in which minority B is used as a bulwark against kin-state A.

Figure 1. Traditional vs. Multiple transborder minorities model.

Unsurprisingly, current scholarship applies the “traditional model” to states with multiple minorities because it captures all the facets of these triadic relations. However, in states with multiple minorities and their kin-states, this model fails to account for all the complex interrelations between fields and their influence on what happens in the state center. By applying the more complex lens, we notice that nation-builders can benefit from having to deal with multiple minorities, harnessing this demographic challenge to the service of nation-building. The next section describes the key attributes of each framing and presents the causal mechanisms explaining how and why titular political elites deploy them.

Model Minorities and Fifth Columns

Powered primarily by the dominant titular political elites, majoritarian ethnic nation-states advance nation-building to create dominant majorities in ethnically diverse societies. Nation-building offers a narrative that includes a story about how the nation-state came to contain “others” and their relation to the titular nation, including their arrival mode (indigenous minorities, [illegal] migrants, and refugees), relational position (economic and political domination or inferiority), and collective values and worth (for example, hard-working, entrepreneurial, lazy, thieving, etc.) (Kim Reference Kim2004). Featuring core elements of a narrative, the story about “us” and “them” often presents these interrelations as those between victims and perpetrators, the wealthy and the deprived, and colonizers, and freedom fighters.

National narratives are central to nation-building policies and practices toward ethnic minorities. Nationalism scholars have offered a parsimonious typology of three nation-building policies of assimilation, accommodation, and exclusion, distinguishing between the desired outcomes they seek to institutionalize toward minorities — recognition of ethnonational diversity or its elimination (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2012; Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012; McGarry and O’Leary Reference McGarry, O’Leary, McGarry and O’Leary1993). Assimilative policies seek to erase group boundaries, absorbing ethnic minorities into the dominant nation and homogenizing the population. Accommodative policies reproduce ethnic differences between the groups by recognizing minorities as distinct groups and providing them with institutional mechanisms to support some extent of separate educational, cultural, religious, or other aspects of their collective identity. Finally, policies of exclusion ignore, suppress, or banish ethnic minorities from the nation-state or a part of it, often through the adoption of restrictive citizenship laws.

Comparative research on kin-state politics often expects transborder engagements between ethnic minorities and their kin-state to securitize ethnic minorities and lead to restrictive or repressive minority policies (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012; Jenne Reference Jenne2007; Radnitz and Mylonas Reference Radnitz, Mylonas, Mylonas and Radnitz2022; Kachuevsky Reference Kachuevsky, Makarychev and Yatsyk2017). I follow recent research on ethnic minority securitization, conceptualizing it as “the politics of targeting a group of ‘others’ as a collective security threat (Csergo, Kiss and Kallas Reference Csergo, Kiss and Kallas2024). Securitization, thus, entails the translation of political discourse presenting ethnic minorities as threatening into restrictive policies adopted against them. However, the titular nation’s political elites do not always perceive substantial and politically mobilized minorities with external patrons as threatening. Mylonas (Reference Mylonas2012) showed that interstate relations between home and kin-states matter for minority treatment. If the kin-state of a transborder ethnic population is an ally of the home-state, titular elites are less likely to perceive the minority as a threat and target it with repressive measures. More recently, Csergo, Kallas and Kiss (Reference Csergo, Kiss and Kallas2024) demonstrated that kin-state politics do not disrupt previously established trajectories of minority policies unless a kin-state turns to territorial revisionism (for example, Russia’s war in Ukraine since 2022). In a state-of-the-field article, Waterbury (Reference Waterbury2020) problematized the inherent expectation of kin-state engagement as inherently hostile and called for distinguishing between different motivations and effects of kin-state engagements.

I build on the conceptual works on the “model minority” developed in the scholarship on race in the American context (Kim Reference Kim1999, Reference Kim2004; Walton and Truong Reference Walton and Truong2023) and comparative nationalism and ethnicity literature to capture the variation in national narratives that dominant elites construct toward ethnic minorities and the purpose they serve for nation-building. Kim’s work on the Asian and African American communities interjects in the single-scale ranking of minorities as disadvantaged vis-à-vis the white dominant majority in America, instead locating their positionality on structural (inferior/superior) and cultural (titular/foreigner) dimensions. The socioeconomic positionality of each minority in the broader society and their cultural attributes as “others” allows for a more nuanced understanding of the differential treatment of ethnic minorities across time and public domains.

As Kim (Reference Kim2015) pointedly argued, the simplistic opposition of the good and the bad, the superior and inferior, obscures ethnic disparities within communities and deliberately ignores their multiple and conflicting voices. However, when harnessed to nation-building aims, the “model minority” stereotype can prove very powerful. It has purchasing power as a nation-building instrument precisely because it presents simplistic and coherent narratives about minority populations (for example, their group values, status, and behavior). Such frames are effective because they are somewhat grounded in reality and appear credible to the target audience (Snow and Bedford Reference Snow and Benford1988, cited in Schulze Reference Schulze2018, 22).

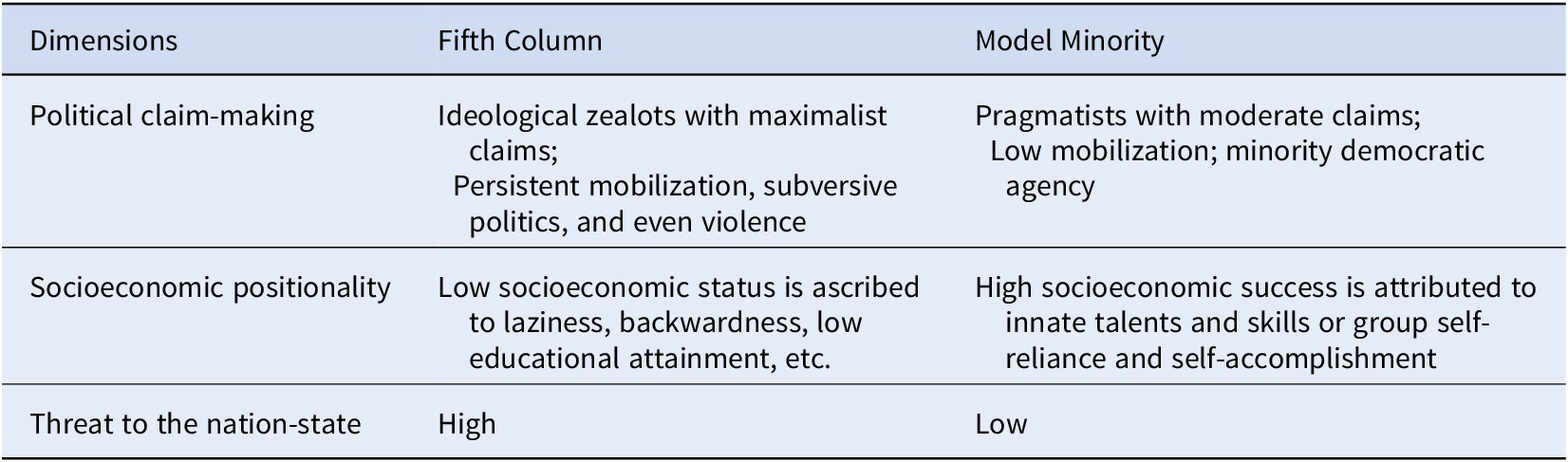

The dimensions setting the “model minority” and “fifth column” archetypes apart are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Dimensions of Model Minority and Fifth Column Frames

First, members of a model minority serve as a reference group to other minorities, compared in their socioeconomic success or failure, given similar structural disadvantages. Other minorities are recast as lazy, prone to criminality or violence, subversive, and backward groups (Chow Reference Chow2017; Wu Reference Wu2014; Kim Reference Kim1999; Reference Kim2015). This stereotype reinforces ideals of innate qualities or group values of minorities, minimizing the role of discriminatory structures disadvantaging minorities and privileging dominant group members despite their individual values and efforts (Walton and Truong Reference Walton and Truong2023). Moreover, it absolves the central government from the responsibility to reduce socioeconomic disparities between dominant and minority groups.

Second, I theorize that “model minorities” are framed as communities exhibiting political behavior that conforms to their politically and culturally inferior status in a state dominated by another nation. These communities are represented as groups making minimal claims that do not challenge the ethnic power relations and privileges assigned to members of the titular nation. In other words, they do not demand broad recognition or major institutional challenges to remove structural barriers; instead they address their distinct needs in their absence (Museus and Kiang Reference Museus and Kiang2009). For example, Asian Americans are represented as a politically acquiescent and self-contained community vis-à-vis African Americans, who demand the “systematic and structural dismantling of racial discrimination” (Lee Reference Lee, Wu and Chen2007, 269). This juxtaposition on the political dimension facilitates framing “fifth columns” as threatening groups engaged in subversive politics who take uncompromising zealot positions and make maximalist claims. Titular nation-builders advance these minority frames while simultaneously working to suppress, conceal, or ignore counternarratives defying or disrupting this dichotomous opposition in the promotion of their political agenda (Kim Reference Kim2004).

Based on these premises, the causal mechanism explaining how and why titular elites deploy these contrasting frames takes on the following logical chain. State-owning political elites craft simplistic stereotypes of ethnic minorities out of socioeconomic positionality, coupled with political attributes of the content and intensity of minority claims ascribed to them. Strategic frames advance a critically important narrative of a system of rewards and punishments toward each minority community. Framing one minority as a model minority advises the “other” minorities to emulate it to build trust and positively affect political outcomes. Lee illustrates this logic by stipulating that “the elevation of Asian Americans to the position of model minority had less to do with the actual success of Asian Americans than with the perceived failure – or worse, refusal – of African Americans to assimilate” (Lee Reference Lee, Wu and Chen2007). As such, “model minorities” framing is predicated on the existence of another minority that is construed as threatening in some way. The opposite does not hold for “fifth column” rhetoric, as it may be used in a state with a single sizable minority, whether it is ethnic (Charnysh Reference Charnysh, Harris and Scott2022), religious (Fabbe and Balıkçıoğlu Reference Fabbe, Balıkçıoğlu, Mylonas and Scott2022), or LGBTQ (Anabtawi Reference Anabtawi, Harris and Scott2022).

Titular political elites deploy these frames when they seek to reproduce ethnic differences and reinforce the primacy of the state-owning nation. Crafting and advancing these contradictory minority frames helps generate broad support for differential minority treatment, according to the logic of reward and punishment. Trustworthy and law-abiding minorities are accommodated, while threatening and disruptive minorities are excluded and even repressed. This rhetoric also helps draw a wedge between minorities with shared interests to prevent the formation of formidable political alliances. A conspicuous example of this divide-and-conquer logic has been practised in Israel’s decades-long distinction between the kin-like Druze, the loyal Christians, and the fifth-column Muslim communities within the Palestinian Arab minority (“Israel’s Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Toward Arabs” 2014).

While these stereotypes are powerful and pervasive, they are amenable to change. In American nation-building, once the external threat subsided, Asian Americans were transformed from the “yellow peril” and “the fifth column of the invading army” to a “model minority” (Wu Reference Wu2014; Kim Reference Kim2004), understood as a “polite, law-abiding group that has achieved a higher level of success than the general population through some combination of innate talent and pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps immigrant striving” (Blackburn 2019). At times of regional security crises, these frames can be rapidly transformed within the same narrative of a system of reward and punishment for loyalty and obedience to consolidate the titular elites’ power. This explanation builds on the general logic of Mylonas’s (Reference Mylonas2012) theory of interstate relations between home- and kin-states. According to this account, home-states perceive minorities supported by hostile kin-states as threatening and, therefore, target them with repressive means. Minorities supported by allied states, however, are not likely to be viewed as a security threat. Extending the logic of this explanation, my theory suggests that in states with multiple transborder minorities with kinship ties to external homelands, a change in minority framing will occur in response to real or perceived threats to each minority community. As the empirical analysis demonstrates, Lithuania’s sudden transformation of Poles from a threat to a brotherly nation and a corresponding securitization of the previously unthreatening Russian-speaking minority showed how quickly narratives of “model minorities” and “fifth columns” can unravel and transform to suit the titular elites’ preferences and agenda. On the domestic front, a change in minority framing also signals the emergence of a new discourse on ethnic relations and a status reversal of minority communities in the home-state. Elevating Poles to the position of a “model minority” altered the power dynamic between the state-owning majority and each minority community and also sent a direct message to Russian speakers that disloyalty and support for Russia would be penalized with further securitization and repression.

Finally, caution is necessary when discussing the “model minorities” and their positive attributes. The monolithic image of “model minorities” conceals the variation in access to and representation in socioeconomic, educational, healthcare, and other institutions of the communities ascribed to it (Walton and Truong Reference Walton and Truong2023). It also does not serve as a protective shield against the titular nation’s discrimination, racism, and oppression. Derogatory terms and accusations of Asian Americans for spreading the “Chinese virus” or the “kung flu” are the most recent reminders of the persistent vulnerability of ethnic minorities in majoritarian states (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2020). Moreover, if ethnic minorities become wealthy, their socioeconomic success shifts from being a positive attribute to a deeply resented one, making them the target of ethnic violence (Chua Reference Chua2004).

Research design

This article conducts a paired comparison within and across two nation-states concerning their transborder minorities. Lithuania and the Kyrgyz Republic are comparable cases of small nation-states that pursue nationalizing policies over their ethnically diverse populations, institutionalizing preferential treatment to the titular nations — Lithuanians and Kyrgyz (Agarin Reference Agarin2010; Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev Reference Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev2014). Russian speakers and Poles in Lithuania and Russian speakers and Uzbeks in the Kyrgyz Republic are sizable ethnic minorities in these countries. At the moment of independence, ethnic Kyrgyz formed 52% of the population of the Kyrgyz Republic; ethnic Russians (excluding Belorussians and Ukrainians) comprised the largest ethnic minority at 22%, followed by Uzbeks at 13%.Footnote 1 In Lithuania, according to the last Soviet census, the titular group formed 80% of the population, followed by ethnic Russians (9%) and Poles (7%).

The four minorities are transborder kin groups with kinship ties to kin-states with whom the home state has a troubled past — Poland, the Russian Federation, and Uzbekistan. During much of the 20th century, imperial Russia and the Soviet Union controlled the lands and peoples of the territories of contemporary Lithuania and the Kyrgyz Republic. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth also governed Lithuania, and the Uzbeks had invaded and occupied the Kyrgyz people in medieval times. Lithuania and the Kyrgyz Republic altered their initial nation-building toward each minority population over time, and the degree of access to state power they provided each minority. This variation is captured by the Ethnic Power Relations (EPR-TEK) Core Dataset. Poles and Russian speakers in Lithuania were “powerless” and Lithuanians “dominant” over the 1991-2019 period. Since 2020, Poles have become “junior partners” to Lithuanians, while Russian speakers have remained powerless (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015a). In the Kyrgyz Republic, between 1991 and 2004, Russian speakers were “junior partners” in government, and the Uzbeks were “powerless,” but as the Kyrgyz claimed power and became “dominant,” Russian speakers became “powerless,” and the Uzbeks were demoted to a “discriminated” group.

Kyrgyz nation-building

In the years leading to state independence, Kyrgyz national elites advanced nation-building to assert the Kyrgyz identity and claim the state as their own (Huskey Reference Huskey1997; Wachtel Reference Wachtel2013). Language Law adopted in 1989 was the centrepiece in this process, mandating the replacement of place names and their spelling to Kyrgyz pronunciation and increasing publications in Kyrgyz (Omelicheva Reference Omelicheva2015; Wachtel Reference Wachtel2013). The Kyrgyz nation-builders set out to create a dominant Kyrgyz nation in one of the most ethnically heterogeneous post-Soviet republics, where the titular majority formed just over half (53%) of the population, followed by two sizable minorities — Russian speakers (21%) and Uzbeks (13%) (Fumagalli Reference Fumagalli2007).

The initial ethnic-based nation-building of the formative years was short-lived. The bloody Osh conflict between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in 1990 and the deteriorating economic conditions during the regime transition encouraged mass emigration of Russian speakers, draining the country’s main source of professional and managerial class (Husky Reference Huskey1997; Concept of National Security 2012). The combination of these ethnic and labor-market factors tilted the political balance from nationalist-minded to more moderate Kyrgyz elites in the first elections (Husky Reference Huskey1997). This shift was signified with the election of Askar Akayev, the only non-incumbent president in Central Asia, and the initial ethnonational discourse gave way to a somewhat more inclusive nation-building project.

The first independent government under Akayev (1991-2005) sought to maintain ethnic peace by recognizing ethnonational diversity (Radnitz Reference Radnitz2010; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). A balancing act between political actors that advocated for an ethnocentric Kyrgyz approach, including those seeking to ban minorities from positions of power and moderates who supported inclusive nation-building, was formed (Melvin Reference Melvin and Yaacov2005). The resulting nation-building approach intertwined ethnic elements of the Kyrgyz nationhood with multiethnicity based on shared citizenship in the Kyrgyz Republic. Recognition of ethnic diversity was advanced under the banner “Kyrgyzstan, our common home.” This narrative acknowledged that members of the titular nation shared their state with other ethnic minorities (Anderson Reference Anderson1999, 21; Wachtel Reference Wachtel2013). The state recognized minority-language schools and instruction streams within Kyrgyz schools as parallel to the Kyrgyz-language schools (Elebayeva, Omuraliev and Abazov Reference Elebayeva, Omuraliev and Abazov2000). The constitutional changes of 1998 and 2001 recognized the special status of the Russian language in Kyrgyzstan, and the constitutional change of 2003 elevated Russian to an official language equal to the Kyrgyz (Chotaev 2012). Finally, an advisory body of 300 minority representatives called the “Assembly of the Peoples of Kyrgyzstan” (ANK) was established in 1994 to maintain the cultural heritage of ethnic minorities and interethnic dialogue (Levitin Reference Levitin and Ro’I2005).

The ethnic nation-building strategies, however, served as a unifying narrative for ethnic Kyrgyz that proclaimed them as the titular nation while excluding ethnic minorities (Marat Reference Marat2008). The 2200-year-old Kyrgyz statehood and the revival of the epic of Manas (the world’s longest epic) as a unifying text of all Kyrgyz tribes highlighted the ancient history that predated all sources of foreign rule by two thousand years (Omelicheva Reference Omelicheva2015; Wachtel Reference Wachtel2013). Tapping into the ethnonationalist sentiments of nationalist parties, Kyrgyz were presented as historically mistreated and repressed by the Russian speakers and Uzbeks (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012).

Alongside these national narratives, practical strategies buttressed the domination of ethnic Kyrgyz over centers of political power. Kyrgyz became overrepresented in political offices, state administration, military, and police (Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev Reference Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev2014). The ethnic composition of the Jogorku Kenesh (Kyrgyz parliament) became ethnicized. Over 90% of the representatives in the 1995 and 2000 elections were ethnic Kyrgyz, compared to the last Kyrgyz Supreme Soviet of 1990, in which the Kyrgyz took 64% of the seats, followed by 19% for the Russians and 8% for the Uzbeks (Levitin Reference Levitin and Ro’I2005). Although the political life became almost entirely reserved to ethnic Kyrgyz, the development of an interethnic system of patronal politics and clientelism undercut ethnonational divisions between Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Russian speakers (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012; Radnitz Reference Radnitz2010; Hale Reference Hale2014).

In 2010, a second episode of ethnic violence between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks erupted, during which 470 people died and thousands were injured; Uzbeks formed about three-quarters of these casualties (Minority Rights Group International 2018a). The conflict was the catalyst for the formation of a comprehensive policy for inter-ethnic peace and social consolidation (ANK 2014, 6). Its mission focused on creating a meaningful civic identity that allowed for the independent development of ethnicities and safeguarded their cultural customs. New administrative institutions were established to manage and implement this political conception, including the state agency for local self-government and inter-ethnic relations (GAMSUMO), the state agency for the national language, and the state agency for religious affairs.

In principle, the new conception echoed the dual commitment to maintaining ethnonational dominance while recognizing and protecting minority rights formed in the 1990s. But in this iteration, nation-building took on a decisively more ethnonational character in which interethnic peace and cooperation were used primarily for rhetorical purposes. A key goal was to privatize ethnic identity so that when asked: “Who are you? People in Kyrgyzstan would respond ‘Kyrgyzstanetz” [Kyrgyzstani]’ instead of identifying as ethnic Kyrgyz, Uzbek, or Russian (GAMSUMO Deputy Director, personal interview, 2016). This is apparent in the reinforcement of the constitutional status of the Kyrgyz language and enforcement of control over those perceived as nation-building challengers. Narratives justifying the need for such protections from imminent threats to the titular language and culture continue to dominate public and political discourses (Minority Rights Group International 2018b; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). Unlike its antecedent, the new nation-building enjoyed broad political support from the ethnic Kyrgyz political elite, substantial resources allocated by the Kyrgyz-dominant parliament, and institutional mechanisms for its realization (Head of the Language Agency, personal interview, 2016).

Minority frames in the Kyrgyz Republic

Historical relations between Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Russian-speaking minorities and their respective kin-states are central to the Kyrgyz nation-building. Interethnic relations under Soviet rule and competing historical narratives of the Kyrgyz experiences feature prominently in conceptualizing the Kyrgyz nationhood and the place of these transborder populations in the Kyrgyz nation-state (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012). Threat perception raised by each community has varied over time, reflecting the larger narrative constructed to deal with the challenges of ethnic demography and regional security environment.

On the eve of independence, Uzbeks and Russian speakers formed similarly sizable minorities. Both minorities are transborder populations with kinship ties to their kin-states — Uzbekistan and the Russian Federation. These minorities are territorially concentrated in separate areas, punctuated by majority group regional domination. Russian speakers reside predominantly in the north and the capital city of Bishkek, while the Uzbeks live in southern Kyrgyzstan.

There are also ethnoreligious differences between these communities. Uzbeks share with the Kyrgyz their Turkic lineage, religion (Islam), and historical presence on the territory of modern-day Kyrgyzstan. Conversely, Russian speakers are relatively new to the region, distinguished from the titular nation by religion (Eastern Orthodox Christianity) and Slavic heritage. The demographic size of the minorities varies considerably: Russian speakers formed 22% of the population in 1989, almost twice the size of Uzbeks (13%).

Uzbeks as a “Fifth Column”

In the late 1980s, Uzbeks made claims on the Soviet government for greater local autonomy in the southern Kyrgyz Republic. By the early 1990s, minority actors escalated their demands for separatism and unification with Uzbekistan (MAR). Uzbekistan officially denounced these claims, giving no backing to Uzbek separatism in Kyrgyzstan (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012). After the bloody conflict in Osh, Uzbeks dropped separatist claims, focusing on political representation, recognition of minority languages in localities dominated by Uzbeks, and support for minority-language education (Fumagalli Reference Fumagalli2007).

Nevertheless, Uzbeks’ initial maximalist demands for separatism and the bloody Osh conflict of 1990 have been routinely used by Kyrgyz political elites to construct members of this minority as a potential “fifth column.” Even in the civic-based narrative of “Kyrgyzstan, our common home,” Kyrgyz featured as the masters and others as guests/renters, expected to show nothing but gratitude to their hosts (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012). Similarly, a moderate Kyrgyz official described Uzbeks as challenging political and social stability:

We had a complicated history with them. They revolted twice, during the Soviet Union and in 2010. They wanted autonomous rule, but Kyrgyzstan didn’t give it to them. After the last events, they realized they couldn’t go to Uzbekistan either. Karimov did not support them. (Dean of the State Governance Academy under the President of the Kyrgyz Republic, personal interview, 2016).

Uzbeks intensified demands for recognition of the Uzbek language and representation in political and state institutions (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012; Fumagalli Reference Fumagalli2007), which contributed to the narrative of ungrateful Uzbeks taking advantage of the “excessively hospitable” Kyrgyz (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). Despite their domination over the political institutions in the country, the Kyrgyz do not hold a political monopoly due to high internal factionalism and ethnic diversity. Consequently, casting Uzbeks as a threatening minority has been instrumental in excluding their political representatives from centers of power. Between 1991 and 2010, Uzbek representatives were not included on par with Russian speakers in political decision-making (EPR). In the 2010 elections, Uzbek representatives took only three of the 120 parliament seats in the Jogorku Kenesh (Weber Reference Weber2010). The Uzbek language was not granted special status even in Batken, Osh, and Jalal-Abad provinces, regions dominated by the Uzbek population (Minority Rights Group International 2018b). Overall, members of this minority became increasingly discriminated against and marginalized. Nation-building strategies recognizing ethnonational diversity were designed to benefit Russian speakers and, therefore, had little effect on the lives of ethnic Uzbeks.

Political underrepresentation and the lack of government responsiveness to Uzbek grievances led to Uzbek mobilization (MAR). Grievances over growing authoritarianism, corruption, and abuse of power fueled the national protests in 2005 and 2010, leading to the overthrow of two governments. The second Osh conflict of 2010 between the Kyrgyz and Uzbek communities was the catalyst for their political repression and persecution. Despite these upheavals and adopting a parliamentary government to curb the previous government’s attempt to consolidate executive power, the entrenched Kyrgyz elite has maintained political power and continued to crack down on members of the Uzbek minority (Freedomhouse 2017).

If, between 1990 and 2010, Kyrgyz elites perceived ethnic nation-building as illegitimate, and Uzbek representatives avoided persistent politicization of ethnicity (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2012), then after the second conflict in Osh, very few politicians from either community refrained from instrumentalizing ethnicity for political purposes. The government rejected the results of the conclusions and recommendations of the international commission that investigated the conflict in Osh, accusing its writers of biased and inadequate analysis depicting Kyrgyz as violent perpetrators (Head of Commission 2011). The state-led account of events framed Uzbeks as a violent, terrorism-prone minority responsible for the bloodshed, even though three-quarters of the casualties were Uzbeks (Minority Rights Group International 2018a). Uzbeks were claimed to be weaponized and ready for the conflict against unarmed Kyrgyz, killing many of them, including Kyrgyz peace negotiations (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015, 426).

The framing of Uzbeks as a traitorous minority justified the mass detention and persecution that followed the events. State authorities placed in detention, arrested, and sentenced Uzbek individuals blamed as conflict perpetrators and denied them an effective legal defence.Footnote 2 The government cracked down on hundreds of Uzbek politicians and human rights activists, accusing them of suspected separatism, extremism, and terrorism (Minority Rights Group International 2018b). Arrests of Uzbeks on terrorism-related grounds continued despite the low terrorism incidence rate (U.S. Department of State 2020).

Since 2010, Uzbeks have also become increasingly discriminated against and marginalized in political and administrative representation, language recognition, and access to education. In 2019, 90% of parliament members were Kyrgyz, 5% were Russians, and only 2.5% were Uzbeks (de Varennes Reference Varennes2019). While both minorities are underrepresented in the public sector, Uzbeks are comparatively worse off as they occupy a fraction of positions compared to their demographic size (14%). Compared to Russian speakers, Uzbeks face dim prospects for socioeconomic mobility and integration in Kyrgyz society and politics.

Russian Speakers as a “Model Minority”

In some post-Soviet republics, mainly Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Ukraine, Soviet rule has been equated with colonialism in which the Russian speakers performed the role of the occupants; an opposite narrative consolidated in the Kyrgyz Republic and much of Central Asia. The Kyrgyz dominant elite adopted the Soviet era (and later Russian Federation) narrative of the civilization Russia has brought to “a world of ignorance, superstition, and poverty” (Darden and Grzymala-Busse Reference Darden and Grzymala-Busse2006). Ethnic Kyrgyz politicians presented Russian speakers as enlightened modernizers of the Kyrgyz people: “When the Tsar almost killed us, Lenin saved us … literacy rose, and the Kyrgyz people became literate and educated, and it was paid for from the pocket of the Russian people” (Former Kyrgyz MP, personal interview, 2016). These attitudes did not change even following Russia’s revisionism in Ukraine in 2022. Over a year into the war, President Japarov declared Russia a strategic ally, expedited the naturalization process of Russian nationals who had fled their country for fear of the draft, and suppressed their attempts to conduct educational or protest activity against the war in Ukraine (Morozova Reference Morozova2023).

In light of this interpretation of the Soviet rule, the mass emigration of Russian speakers in the early 1990s was not a positive development but a tragedy: “People’s hearts are in pain because our brothers are leaving” (President Askar Akaev’s speech in 1994, cited in Marat, Reference Marat2008, 15). A narrative of the Russian speakers as a “model minority” started to shape based on the positive view of the Soviet/Russian influence on the Kyrgyz people. Senior Kyrgyz officials continue to maintain this worldview when asked about the positive perception of Russian speakers: “Why were inclusive policies introduced towards Russians? Because we are grateful to the USSR, to the Communists, to Tsarist Russia, and the Russian nation” (The Head of the Assembly of the Peoples of Kyrgyzstan, personal interview, 2016).

Against the separatist claims made by the Uzbeks and the violent conflict between them and the Kyrgyz in 1990, Russian speakers represented an exemplary docile, loyal, and productive minority — a model to be emulated by the Uzbeks. As one of the Kyrgyz Constitution writers argued: “[Russian speakers’] representatives were pragmatic people. They did not ask for autonomy” (Former Kyrgyz MP, personal interview, 2016). Russian-speaking representatives had no territorial ambitions, Russian minority voters did not support strictly ethnic parties, their community was not segregated and highly territorially concentrated (providing the potential for secessionism), and its members demonstrated high self-reliance and socioeconomic success without state support.

Due to these positive attributes, Akayev’s government made a credible commitment to reward the Russian speakers. The Constitution officially recognized the Russian language as another official language in the state and allowed public communication with a significant Russian population in local authorities. The state removed barriers to Russian minority representation in high government posts (Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev Reference Hierman and Nekbakhtshoev2014; Goldman Reference Goldman2009, 155). Owing to this political inclusion, Russian speakers became junior partners in governing coalitions during the first decade following independence (EPR). The most notable examples of meaningful inclusion are Russian speakers appointed as Prime Ministers — Nikolai Tanayev (2002-2005), Felix Kulov (2005-2007), and Igor Chudinov (2007-2009), among others.

By the early 2000s, the national demography had changed dramatically. Russian speakers shrank in size from 22% in 1989 to 15% in 1999. With their proportional decrease, the population had become predominantly comprised of Central Asian and Muslim communities. However, the increase in shared ethnic lineage (Turkic people), and Islam did not play a role in developing a narrative of close nations between the Kyrgyz and the Uzbeks. The increasingly nationalist Kyrgyz governments have been chipping away at the stereotype of Russian speakers as a “model minority.” Demographic changes and Russian minority claim-making, coupled with more ethnonational nation-building, precipitated this change. Specifically, in the 2000s, Russian speakers started to articulate more assertive political claims and held a national congress in Bishkek focused on minority protections (MAR). The growing ethnicization of the labor market and state institutions became a concern for Russian speakers, fearing displacement by ethnic Kyrgyz. Discursive framing of the threat to the Kyrgyz language and culture started to form to justify special protections for the core nation from other ethnicities (Minority Rights Group International 2018b). Minority fears materialized in 2015 with the introduction of mandatory Kyrgyz language competence and testing requirements for civil service positions (de Varennes Reference Varennes2019). These changes have not led to the complete abandonment of the “model minority” stereotype, but they indicate a meaningful change away from the advantageous status assigned to Russian speakers and their positive framing as a “model minority” vis-à-vis the Uzbek “fifth column.”

Lithuania’s nation-building narrative construction toward Poles and Russian speakers

On March 11th, 1990, the Republic of Lithuania declared independence from the USSR, ending 50 years of Soviet rule. The post-independence government pursued nation-building shaped by the country’s experiences under foreign occupying powers in the 20th century. Prolonged Polonization, followed by Russification, had diluted the Lithuanian population and reduced the use of the Lithuanian language in public. The reversal of assimilationist language projects of occupying powers and securing the dominant status of the Lithuanian language and culture became the core of the nation-building project.

Lithuania claimed legal continuity to the pre-Soviet Lithuanian state, setting out to restore its statehood as a Lithuanian nation-state (Krūma Reference Krūma, Bauböck, Perchinig and Sievers2009). The Constitution of Lithuania, the State Language Law, and the Law on National Minorities formed the centrepiece of Lithuania’s restitution and nation-building. The Lithuanian Constitution, adopted in 1992, defines the nation in ethnic terms, addresses Lithuanians as the founders of the state, and anchors the rights of ethnic Lithuanians to live and pursue their lives in the ancestral land of their forefathers. Lithuanian is the only official language, and its status is protected by the Constitution and reiterated in the State Language Law of 1995. In education, Lithuania set to transition to a national education system, a process that rapidly departed from the authoritative, infused with the communist ideology Soviet education, to one based on the Lithuanian language with decentralized decision-making and de-Sovietized curricula and learning materials (Lithuania education policy 2002). Additional legislation adopted during the first decade in language, education, and culture consolidated the dominant status of the Lithuanian culture and language in the state (Agarin Reference Agarin2010), creating a comprehensive regime infused with Lithuanian identity.

Lithuania’s nation-building unfolded in the context of a heterogeneous society. Ethnic Russians formed the largest minority at 9.4% of the population, followed by Poles (7%), Belarusians (1.7%), and Ukrainians (1.2%) (Kasatkina and Beresneviciute Reference Kasatkina and Beresneviciute2010). Distinguished by language, religion, and culture, Russian speakers and Poles were designated as “others,” falling outside the ethnonational boundaries of the state-owning nation. The titular and minority communities inhabit separate and largely parallel communities. Their children are educated in separate schools; they celebrate their distinct holidays and festivities, and congregate in separate churches set apart by a religious denomination or language of worship (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Minorities are not well-integrated into Lithuanian-dominated society, particularly the Poles, due to a lack of language competency in the state language and diminished social mobility (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Residents of suburban areas around Vilnius and the southeast, Poles are more separated from the Lithuanian society than urban-dwelling Russians. In addition to these linguistic, religious, and settlement distinctions between Lithuanians, Russian speakers, and Poles, the transborder kin ties further deepen the ethnonational boundaries. Through shared culture, language, and ethnic origin, these minority populations have kinship ties to the Russian Federation and Poland — Lithuania’s former colonizers.

Against this backdrop, Lithuania has advanced nation-building designed to maintain a balance between the aims of privileging co-ethnics and creating a Lithuanian identity rooted in citizenship. In 1989, Lithuania adopted the Law on National Minorities that secured the rights of ethnic minorities to develop their culture and receive education in minority languages (Agarin Reference Agarin2010). In the same year, it established the Department of Nationalities, a state authority responsible for carrying out policies toward recognized minorities. Upon independence, Lithuania anchored the recognition of ethnic minorities in the Constitution, stipulating that “ethnic communities of citizens shall independently manage the affairs of their ethnic culture, education, charity, and mutual assistance. Ethnic communities shall be provided support by the State” (§45).

Lithuania provided ethnic minorities with the institutional means guaranteed by law to maintain bilingualism. However, minority recognition has not been equally upheld across different public domains. Initially, minority language use was allowed in the public sphere in localities dominated by minorities. With the adoption of the State Language Law in 1995, a legal contradiction appeared as the Law on the National Minorities, which allowed the use of minority languages in public, whereas the State Language Law stipulated that Lithuanian was the only official language, providing no guarantees for minority languages. This legal tension was finally resolved in 2010 with the abolition of the Law on National Minorities. The state has lacked a designated law enshrining specific rights and protections for ethnic minorities since then.

Recognition of minority rights during the unsteady nation-building project is somewhat surprising, particularly in light of the exclusionary minority policies adopted toward Russians in the neighboring Latvia and Estonia. Unlike the other Baltic states, Lithuania also treats its substantial minorities as transborder groups, a decision anchored in bilateral agreements with their external homelands — Poland and the Russian Federation. These treaties placed the responsibility over the maintenance of minority languages, cultures, and religions onto their external homelands, allowing Lithuania to commit to the advancement of the titular nation’s collective markers (Agarin Reference Agarin2010).

Minority Frames in Lithuania

Historical and contemporary attributes distinguish between the Polish and Russian-speaking minorities. Poles and Lithuanians are Catholic and they share a long common history under the same political unit (the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth) as well as Europeanness. Conversely, Russian speakers are a relatively newer minority in Lithuania, with fewer commonalities with Lithuanians.

Poles as a “Fifth Column”

Due to the inexistence of certain letters in the Lithuanian alphabet (for example, “W”), Poles could not spell their surnames according to the Polish orthography in their passports and other official documents (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Strict language use regulation, decreed by the 1995 State Language Law, banned the transliteration of Polish surnames in their original. These restrictions on minority language use in public and official correspondence have affected Poles differently than Russian speakers. Territorially concentrated Polish minorities in rural localities around Vilnius and the Salcininkai region maintain a separate communal life, facilitating their preference for public communication and the use of Polish street names in areas where they form the dominant share of the population.

A strong sense of a distinct national identity, territorial concentration, and an assertive claim-making on the central government has positioned the Poles as a threatening minority seeking increased self-governance. Poles are politically consolidated and have a demonstrable capacity to mobilize their community. They have supported a single ethnic party — LLRA-KSS — trumping other ethnic parties and securing political representation, particularly in areas of high demographic concentration of Poles (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). The LLRA-KSS has held a longstanding demand for the approval of Polish transliteration and use in public correspondence and street names in Polish-dominated localities. They utilized the tension between the Constitution, safeguarding the status of Lithuanian as the only official language, and the Law on National Minorities, which speaks to the right to use minority languages in public communication, to claim regional language status (Agarin Reference Agarin2010).

The contestation of the city of Vilnius/Wilno and the competing historical narratives of rightful ownership of the city that was part of Poland until World War II contributed to the titular elites’ high threat perceptions toward the Poles in the 1990s (Lithuania education policy, 2002). The Vilnius region’s Polish population rapidly fluctuated over the 20th century, as many Poles immigrated to it in the 1920s and 1930s, only to repatriate after WWII with the establishment of Soviet rule (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). The city’s importance for the Poles had led them to seek autonomy in the Vilnius region and claim restitution of their former lands in the early 1990s. While the Poles have long since dropped claims to Vilnius from their political agenda and focused on language and education rights instead,Footnote 3 the content and intensity of their claim on the capital were perceived as a demonstration of disloyalty by the dominant elites and exploited by them to rule out any concessions to the Polish political party (Gebern 2013, 221, cited in Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021).

Poland’s kin-state policies have further exacerbated the threat perception of the potentially disloyal Polish minority in Lithuania. Poland has been financially assisting Polish-language schools and civil society organizations (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021) and running an international branch of a Polish university in Lithuania (Chankseliani Reference Chankseliani2020). The kin-state also sharply criticized Lithuania’s rejection of Polish minority demands, particularly regarding name transliteration. Although Lithuania reassured Poland it would permit the original name spelling before the two signed a treaty in 1994, it maintained these restrictions intact.

Lithuania’s government, in turn, condemned Poland’s kin-state policies for intervening in domestic affairs, particularly the Karta Polaka distributed to Lithuanian citizens of Polish descent (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Karta Polaka is a kin-state benefit law that has been issued to Poles outside of Poland since 2007. It provides its holders with visa fee waivers, the right to work in Poland, obtain higher education, access public healthcare, and establish a company in Poland (Sendhardt Reference Sendhardt2017). The document is not internationally recognized for travel and does not entitle its holder to Polish citizenship or lawful settlement in Poland. Rather, its importance is in easing travel for significant Polish minorities in non-EU countries, primarily Ukraine and Belarus, which, following the establishment of the Schengen agreement in 2007/8, were excluded from the visa-free border regime. Of the total 162,218 cards issued by the end of 2015, the predominant beneficiaries were Poles in Ukraine (76,742) and Belarus (69,630) (Sendhardt Reference Sendhardt2017).

As is common with home-state responses to kin-state policies, this kin-state benefit law engendered political disputes and the framing of Poles as a potentially disloyal population. Lithuanian political representatives have questioned the eligibility of the Karta Polaka holders to occupy public positions, pointing to a conflict of loyalties between Lithuania and Poland (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). A notable holder of the card is the leader of the Polish LLRA-KŠS party in Lithuania and a member of the European Parliament, Valdemar Tomaševski (Waldemar Tomaszewski), who came under public scrutiny. Questioning the loyalty of the Polish citizens gained political currency in Lithuania and was used to undermine and dismiss minority demands for recognition (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021).

Russian Speakers – Nearly a “Model Minority”

Russian speakers have been less inclined to claim language use in central or local governments. Strict transliteration regulations are a non-issue for Russians whose Lithuanian name spelling is consistent with their Cyrillic spelling. Members of this minority population are also distinct from the Poles in settlement patterns. They live in large cities where they are not the demographic majority (except for Visaginas, where they are the largest group at 47.4%).Footnote 4 Due to their settlement pattern in large, mixed cities, language recognition never became a grievance motivating minority claim-making. Instead, they gradually shifted their preference from minority-language schools to Lithuanian-language schools. This preference change was motivated by the higher student performance in Lithuanian-language schools compared to other schools and the prerequisite of titular language competency for socioeconomic mobility in a Lithuanian-dominated labor market (Agarin Reference Agarin2010).

While Poles opted to “adhere to all things Polish” (Agarin Reference Agarin2010), Russian speakers have coalesced around a loosely understood “Russian-speaking” community, politically submissive and set on an assimilative path. Lithuanian dominant elites framed Poles as a threatening minority and securitized minority demands for recognition while simultaneously rewarding Russian speakers with positive framing and treatment as a loyal and well-integrated community. Russia’s increasing revisionism in Ukraine since 2014 has transformed this formula, rapidly securitizing the Russian speakers and framing them as a potential “fifth column” while simultaneously accentuating the deeply-rooted partnership between Lithuanians and Poles.

Transformation of Minority Frames

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 signified a turning point in the threat perception of each minority in Lithuania. Russia’s growing revisionism in Ukraine and use of the Russian-speaking minority as a pretext for violating Ukraine’s sovereignty and territoriality integrity have made it a significant threat to its sovereignty.Footnote 5 The recent stationing of Russian military equipment and troops near Lithuania’s border with Belarus exacerbated these security concerns.Footnote 6 Russia’s longstanding claims of mistreating its kin population in the Baltic states have triggered the securitization of Russian speakers in Lithuania,Footnote 7 which, until then, applied primarily to the Poles.Footnote 8

Securitization of Russian speakers focused on where their loyalties would lie in the event of a Russian invasion. Lithuanian political actors assigned Russian speakers the role of an unintegrated minority, lacking fluency in the titular language, and expressed loyalty to the Russian state — a potential fifth column.Footnote 9 Lithuanians’ perception of this minority worsened, increasing from 15% disapproval in 2013 to 34.2% in 2014 following the annexation of Crimea.Footnote 10 This threat perception escalated with the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia’s recent bill proposing to revoke the recognition of Lithuania as an independent state has been taken as a direct and imminent threat to Lithuanian sovereignty.Footnote 11

Lithuania responded to Russia’s revisionism with a principle-based foreign policy, a step that has worsened interstate relations and increased minority securitization.Footnote 12 It was the first country to declare support for Ukraine in its war against Russia, send weapons, and have the head of state visit Kyiv during the war.Footnote 13 It also hosted Russian and Belarusian dissidents and opposition leaders.Footnote 14 Furthermore, state and local authorities in Lithuania responded with measures against public support for the Russian invasion. Just hours after Russia invaded Ukraine, Lithuania declared a state of emergency. It passed new legislation that rapidly banned public events that supported Russia’s or Belarus’ actions. This measure enabled the state to remove access to media outlets for up to 72 hours for broadcasting “disinformation,” “war propaganda,” or “incitement of hate” relating to the invasion.Footnote 15 Although Lithuania’s media is considered free and independent according to Reporters Without Border World Press Freedom Index (ranked 9th in the world in 2022), the state-imposed restrictions on media outlets owned, controlled, or financed by the Russian Federation or the Republic of BelarusFootnote 16 for disinformation, anti-western rhetoric, and propaganda of the war in Ukraine.Footnote 17 As of February 2022, Lithuania suspended the distribution and reception of dozens of Russian television programs and access to 92 websites that are claimed to promote Russian state-led propaganda on Lithuania’s territory.Footnote 18 At the local level, Vilnius municipality renamed the street leading to the Russian embassy to “Ukrainian Heroes.”Footnote 19 It also condemned teachers in Vilnius who expressed support for the Russian regime or its aggression against Ukraine, leading to their resignation and a ban on their hiring in other schools.Footnote 20

Russian speakers have been rapidly reframed from a community approximating a “model minority” — politically acquiescent, presenting low-intensity claims, socioeconomically integrated, and on a path to assimilation — to a potential “fifth column.” Lithuanian politicians promote this narrative through mainstream media despite official government data and survey findings showing that Russian speakers consider Lithuania their native country and identify with it, while Russia is perceived only in a cultural sense.Footnote 21 The claims that the Russian speakers are not socioeconomically integrated or fluent in the Lithuanian language are also contrary to official census data.Footnote 22

Alongside the rapid securitization and framing of Russian speakers as a potential “fifth column,” the framing of Poles has shifted in the opposite direction. The fear of the Russian kin state intervening on behalf of the Russian speakers has highlighted the common interests, preferences, and historical ties between Lithuanians and Poles, recasting their relations positively. Public perception of the Polish minority has become more positive,Footnote 23 and Lithuania-Poland relations were branded as a “strategic partnership” (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). This partnership highlighted Poland and Lithuania’s shared attributes as European democracies and EU and NATO members, setting them apart from Russia’s foreign policy and worldview.

The approval of Polish name transliteration in 2022 marked a significant concession to a longstanding Polish claim. The broad consensus of the Lithuanian political elite supporting this recognition demonstrates that Poles were rewarded for their kinship ties to an allied state, while Russian speakers were punished for ties to the hostile Russian kin-state. In 2019, the Polish LLRA-KSS party was formally included in the governing coalition and held two ministerial positions (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Deemed politically “powerless” for three decades, Poles currently enjoy the status of a “junior partner” in the governing coalition (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015a). Political inclusion of Polish minority actors and recognition of the Polish name transliteration elevated their status while increasingly securitizing the Russian speakers.

Additional steps were taken to draw a wedge between the two minorities due to their high exposure to Russian state-sponsored media. An overwhelming majority of Russian speakers (82%) watch Russian news daily,Footnote 24 and about half (54%) of Poles frequently watch Russian television (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Russian media’s influence is notable, as repeated surveys demonstrate minorities’ acceptance of Russia’s worldview. Situated in and influenced by Russian state media, Poles and Russians reminisce about the Soviet past — 41.2% of Russians and 43.4% of Poles agreed with Putin’s infamous statement that “the dissolution of the Soviet Union was one of the biggest geopolitical catastrophes of the century.”Footnote 25

The daily exposure to Russian state media and acceptance of its worldview among the Polish minority population has been negatively perceived by Lithuanian governments, which had sought to divert them toward Polish media instead. The current government even purchased the Polish television channel rights (Janušauskienė Reference Janušauskienė2021). Blocking the Russian media misinformation flow into Lithuania affected the two minorities differently. Poles were further accommodated through state investment in minority-language media from their kin-state. By contrast, Russian speakers were banned from consuming media produced in their kin-state.

Conclusion

This article examines the differential effects of minority frames used for advancing nation-building on transborder minorities, their responses, and how the state instrumentalizes these responses to create securitized “fifth columns” of some minorities and “model minorities” of others. Specifically, I explored why the initially excluded Poles have been recently accommodated in Lithuania, why the long-term marginalization of the Uzbeks in the Kyrgyz Republic has been replaced with repression, and why the relatively accommodated Russian speakers, former colonizers, became framed as a major security threat in Lithuania but not in the Kyrgyz Republic after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This article proposes a complex relational approach for examining nation-building policies and practices in states with multiple minorities. The commonly used triadic nexus framework overlooks the complex interrelations within nation-states, their multiple ethnic minorities, and their respective kin-states, and their influence on government policies toward minority populations. Adopting a more complex view of these interrelations enables observing that the titular political elites use the presence of multiple minorities to their benefit, playing them against each other by assigning them opposite frames of a “model minority” and a “fifth column.” Strategic framing, thus, generates broad support for differential minority treatment according to the logic of reward and punishment. Trustworthy and law-abiding minorities are accommodated, while threatening and disruptive minorities are excluded, and even repressed. In doing so, minority frames are deployed to advance two titular political elites’ aims. First, they help maintain nation-building policies upholding the dominant status of the titular nation by discrediting ethnic minority claims for major institutional changes or restructuring that would reduce majority dominance. These contradictory frames effectively brand one minority as a success case and another one as a failure within the same institutional framework. Rather than resulting from structural disadvantage, ethnic discrepancies are ascribed to minority individual and collective attributes and practices. Accordingly, minority demands for institutional changes are dismissed. Second, the strategic framing of minority populations reinforces public support for the differential treatment of ethnic minorities in accordance with what the titular political elites consider to be in their national interest at a particular time. Minorities construed as “fifth columns” are excluded from power and resource distribution centers, while “model minorities” are afforded some recognition. These stereotypes can further serve majoritarian nation-building by drawing a wedge between formidable minority alliances or deterring minorities from mobilization.

This relational approach of strategic framing helps avoid the essentialization of ethnonational and religious identities as explanatory factors in nation-building policies toward minorities. Nation-builders in Lithuania (Catholic Christian) and the Kyrgyz Republic (Sunni Muslim) excluded the constitutive “other” minorities of the same religious tradition as members of the titular nation and framed them as threatening (Poles and Uzbeks). The Russian-speaking minorities (Orthodox Christian), on the other hand, were initially accommodated in both states despite being of a different religious denomination in Lithuania and of a different religion in the Kyrgyz Republic. That is to say, religious identity did not reinforce nationalism against adherents of other religions or create multireligious and secular nation-building (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2022).

Minority communities, in turn, responded to “fifth column” framing to dispel these myths. Russian speakers across the Baltic states have persistently pushed back on securitization discourse advanced by nationalist parties long before the war in Ukraine. Similarly, both Uzbek and Polish political representatives abandoned claims for autonomy early on to reduce the titular elites’ threats. However, inherent disadvantages preventing minorities from being able to access political power centers and influence the public discourse impede minority attempts to destigmatize and desecuritize discourses crafted against them. This desecuritization struggle is pervasive for transborder minorities whose home-states live in the shadow of powerful kin-states and former colonizers, frequently securitizing minorities for real or perceived threats.

Illuminating possible interrelations not captured by the triadic nexus approach opens new paths for theoretical, empirical, and methodological exploration of nation-building, ethnic politics, and securitization. Future research can focus on deepening our understanding of different strategic frames’ short- and long-term objectives. Targeting some minorities as “fifth columns” in exclusionary nation-states may be a transitional tactic designed to generate support for entirely removing this collective threat by, for instance, discoursively juxtaposing it against the “model minority.” Belligerent nationalism may then scapegoat the “model minority” as wealthy and overachievers (previously positively perceived attributes) at the expense of members of the titular nation in their own country. Finally, we also need to develop a comparative understanding of minority securitization triggers and how their institutionalization creates enduring legacies of ethnic inequalities.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Şener Aktürk, Matthias vom Hau, Eleanor Knott, Zsuzsa Csergő, Tutku Ayhan, and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank the participants of the 2023 World Convention of the Association for the Study of Nationalities, Columbia University, NY, the 2023 Jean Monet SECUREU Conference at Koç University, Turkey, and the 2024 Seminar Speaker Series at the University of Toronto for their valuable feedback on previous drafts.

Disclosure

None.