1 IntroductionFootnote 1

Convening a meeting with members of the Russian Security Council over a week since the full-scale invasion of February 2022, President Vladimir Putin confirmed the first official death in the war – a young officer from Dagestan in the North Caucasus.Footnote 2 Weaving the announcement into a narrative of Russian unity, Putin remarked:

I am a Russian [russkii]…but when I see examples of such heroism as the feat of a young man — Nurmagomed Gadzhimagomedov, a native of Dagestan, a Lak by ethnicity, our other soldiers, I want to say: I am a Lak, I am a Dagestani, I am a Chechen, Ingush, Russian, Tatar, Jew, Mordvin, Ossetian. It is simply impossible to list all the more than 300 national and ethnic groups of Russia. I think you understand me. But I am proud that I am part of this world, part of the mighty, strong and multinational people of Russia. (“Soveshchanie s postoiannymi chlenami Soveta Bezopasnosti” 2022).

The ability for external conflict to catalyze national consolidation through state- and nation-building is well-documented (Tilly Reference Tilly1990; Doner, Ritchie, and Slater Reference Doner, Ritchie and Slater2005; Darden and Mylonas Reference Darden and Mylonas2016). At the individual level there is also evidence that national consolidation can dampen exclusionary attitudes towards out-groups when these groups are recategorized as members of a common ingroup (Gaertner et al. Reference Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman and Rust1993). Previous research has found evidence for this in the Russian case; not only did the annexation of Crimea in 2014 boost patriotic sentiment among Russians (Hale Reference Hale2018; Greene and Robertson Reference Greene and Robertson2022), but survey data pre- and post-Crimea found a sharp decrease in hostile attitudes towards minorities from the Caucasus (Levada Center Reference Center2014; Alexseev and Hale Reference Alexseev, Hale, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016). Meanwhile, there is also evidence of national consolidation in Ukraine post-2022 in terms of language use and ethnic self-identification (Kulyk Reference Kulyk2023, Reference Kulyk2024).

Whether the Russia-Ukraine War promotes centrifugal or centripetal forces (or both!) in Russian society is an increasingly important question for scholars and policymakers. While external conflicts can lead to national consolidation, they can also create new divides and exacerbate already-existing cleavages in society. Putin’s above announcement belied an uncomfortable pattern that emerged in the subsequent weeks and months: that ethnic minorities from poor regions appeared to feature disproportionately among the Russian military dead (Lenton Reference Lenton2022a; Bessudnov Reference Bessudnov2022; Kovalev Reference Kovalev2022; Vyushkova and Sherkhonov Reference Vyushkova and Sherkhonov2023). While protests have generally been infrequent and quickly repressed since February 2022, there have nevertheless been instances of unexpected protest activity in Russian regions, including the Northern Caucasus (Lenton Reference Lenton2022b), the republics and indigenous communities of Siberia (Balzer Reference Balzer2023), and most recently in Bashkortostan (Shkel et al. Reference Shkel, Dekalchuk, Grigoriev and Smyth2024). There is also some evidence that minorities are less supportive of the war (Marquardt Reference Marquardt2023). Putin himself implied that the West aims to stoke ethnic divisions in Russia in his 2024 Address to the Federal Assembly, where he described that the West, “with its colonial practices and penchant for inciting ethnic conflicts around the world,” seeks “to replicate in Russia what they have done in numerous other countries” (Putin Reference Putin2024).

This article contributes to this emerging discussion by exploring Russian national identity and nation-building in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine War. It leverages original survey data from questions fielded by Levada Center in December 2022 to explore citizen attitudes towards the political community. Notably, most Russians (65%) embraced a multiethnic vision of the political community, and this was greater in December 2022 – i.e., nearly a year into the war – than at any point since 1995, when the same question was first posed in surveys. Yet, when later asked about the boundaries of the political community, respondents tended to exclude ethnic minority groups and political opponents. Perhaps most surprising of all was that respondents displayed the most inclusive attitudes towards the only group that unambiguously does not consist of Russian citizens: citizens of former Soviet states who consider themselves to be “Soviet people.”

While puzzling at face value, this discrepancy is quite consistent with the government’s approach to nationalism and nation-building, which embraces a rhetorical commitment to a multinational vision of the Russian state while simultaneously privileging ethnic Russians as the “core” of an imagined rossiiskii political community. This vision, I argue, can be thought of as being “multinational in form, russkii in content.”

These findings make two contributions to scholarship. First, while scholars of Russian nationalism have long acknowledged the conceptual challenges associated with the russkii/rossiiskii dichotomy, less research has specifically attempted to quantify the dimensions across which these two terms may overlap for citizens.Footnote 3 The findings presented here suggest that this dichotomy may be overstated: just as scholars have cautioned against viewing russkii exclusively in ethnic terms, I suggest that rossiiskii oughtn’t be viewed as an exclusively non-ethnic category either. Second, the findings shed light on some of the political drivers of nationalist attitudes and preferences during wartime Russia. Russians continue to prefer a multiethnic vision of the Russian state – a finding that is well-reflected in the rhetorical commitment to multiethnicity at the official level – yet at the same time respondents tend also to display varying levels of exclusionary attitudes towards ethnic minorities and political opponents when prompted to think about the ideal boundaries of the political community. Meanwhile, I also find that those who disapprove of Putin and the government tend to display more ethnically exclusionary attitudes, while the data also suggest important differences along gender, income, and media consumption lines.

In the following section I review Russian nation-building policy and existing scholarly literature. In Section 3 I introduce the research design. Section 4 presents the results and their interpretation, and Section 5 concludes, outlining implications and further areas for study.

2 Ambiguities in Russian nation-building policy

It is worth briefly noting the challenges associated with the russkii/rossiiskii dichotomy. While both words translate as “Russian” in English, the former is both adjective and noun that usually refers to ethnic Russians and Russian culture and language, while the latter is an adjective describing belonging to Russia and/or the Russian state. Accordingly, I use the term “Rossian” to refer to Russian in the latter sense (from the Russian rossianin). While all citizens of Russia are Rossian, around 1/5 are not ethnic Russians.

In the early post-Soviet period under President Boris Yeltsin, the term “Rossian” was encouraged as a civic, supraethnic basis for the political community that could simultaneously avoid the twin threats of ethnonationalism and imperial nationalism while representing a clean break from the Soviet past (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023). This was best encapsulated in the 1993 Russian Constitution, which defines the political community as the “multinational people” (mnogonatsional’nyi narod) of the Russian Federation. That said, “Rossian” did not take off as a widely embraced term, and nation-building was largely overshadowed by struggles over political and economic transition that characterized the Yeltsin years (Rutland Reference Rutland, Newton and Tompson2010; Goode Reference Goode2019).

This tension around the russkii/rossiiskii dichotomy illustrates a more fundamental conceptual ambiguity at the heart of Russian nationalism: what are the boundaries of the “Russian” political community? Russia’s national identity has long been intensely debated, and particular attention has been paid to the complex relationship between empire and nation (Hosking Reference Hosking1997; Miller Reference Miller, Miller and Berger2015; Kolstø Reference Kolstø2019). This relationship has continued to shape differing answers to the above question as various forms of imperial and nation-state nationalism have emerged and compete with one another.Footnote 4 That these groups’ vision of the boundaries of “Russia” can differ quite significantly is, to use Roman Szporluk’s term, one of the principal “dilemmas” of Russian nationalism (Szporluk Reference Szporluk1989, 17). Furthermore, while competing nationalisms exist in most societies, in the Russian case some of the core questions of the nation remain unsettled in the context of imperial collapse (Tolz Reference Tolz2001, 12). Most instances of the end of empire in the twentieth century led to the shattering of multiethnic polities into smaller aspiring nation-states (Barkey Reference Barkey, Barkey and Von Hagen1997, 104). Russia, however, was unusual among the successor states of the Soviet Union insofar as it emerged post-1991 with an ethno-federal structure (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023, 3).

Accordingly, scholars have framed Russian nation-building in terms of being purposefully or by default ambiguous (Rutland Reference Rutland, Newton and Tompson2010; Shevel Reference Shevel2011; Goode Reference Goode2019; Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023). Paul Goode has argued that this is an outcome of institutional instability that carried over from the Yeltsin period (Goode Reference Goode2019). Others, such as Oxana Shevel and Marlène Laruelle, have emphasized the instrumental benefits of such ambiguity for policymakers (Shevel Reference Shevel2011; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2017). According to such accounts, the Kremlin is able to maintain situational flexibility vis-à-vis nationalist actors of various stripes and to “avoid tying themselves to an overly rigid concept that would limit their leeway for action” (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2017, 96). For Helge Blakkisrud, whilst this flexibility remains, an increasing shift to russkii represents an approach to “squaring the civic with the ethnic” which may constitute a more “viable base for its further nation-building project” (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023, 12). Thus, ambiguity not only enables tactical shifts where necessary, but may also be sufficiently vague to resonate with a broad spectrum of groups.

A common thread uniting these perspectives is that the ability of the Kremlin to rigidly enforce its nation-building policy has been rather limited. This can be seen when considering the state’s lack of capacity – and willingness – to commit to a single nation-building discourse (Shevel Reference Shevel2011), the prominent role of bottom-up grassroots and parastate actors in discussions thereof (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2017; Waller Reference Waller2021; Grek Reference Grek2023), as well as the uneven regional context, whereby Russia’s ethnic republics have had a variegated degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the federal center (Libman Reference Libman and Gill2023, 171).

Despite this ambiguity, there has been a clear trend towards carving out a privileged position for ethnic Russians as the “core” of an imagined rossiiskii political community, a trend which has coincided with the “conservative turn” taken by the Kremlin in Putin’s third term (2012-2018), largely interpreted as a response to growing middle-class opposition as exemplified in the large-scale “Bolotnaia” protests of late 2011 (Sharafutdinova Reference Sharafutdinova2014; Østbø Reference Østbø2017; Shcherbak Reference Shcherbak2022). Putin’s article on the nationalities question in the run-up to the 2012 presidential election captures this trend quite well – he simultaneously attacked the idea of a “monoethnic [Russian] state,” whilst also introducing an element of hierarchy by claiming that “the ethnic Russian people [russkii narod] are state-forming [gosudarstvoobrazuiushchiĭ]” (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016, 39; Putin Reference Putin2012). This very same turn of phrase would find itself in the 2020 constitutional amendments, notably Article 68, according to which “the state language across the entire territory of the Russian Federation is Russian, as the language of the state-forming people, entering into a multinational union of equal peoples of the Russian Federation” [italics indicate text added per the 2020 constitutional referendum] (“Novyi tekst Konstitutsii RF s popravkami 2020,” n.d.). Policies such as the curtailment of teaching ethnic minority languages in 2017, and the erosion of ethnic republics’ autonomy further testify to this trend (Yusupova Reference Yusupova2018; Lenton Reference Lenton2021; Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud and Gill2023).

At the same time, however, this growing emphasis on russkii characteristics is not incompatible with the multiethnic nature of the Russian state. We can see this in the thought of one of the most prominent figures to articulate the importance of a rossiiskii nation-building policy, Valerii Tishkov, Director of the Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1989-2015) and Chair of the State Committee of the RSFSR-RF for Nationalities Policy (1992).”Footnote 5 While Tishkov describes the rossiiskii nation as a “nation of nations”(Tishkov Reference Tishkov2008, 4) and is careful to note that the project is not aimed at “making Rossians [delat’ rossiian] out of ethnic Russians, Tatars, Chuvash, etc.” (Tishkov Reference Tishkov2008, 10; 2013, 11), he has also suggested that the “cultural basis for the formation of political (civic) nations is most often based on the culture and language of the dominant majority”(Tishkov Reference Tishkov2013, 586). For this reason Tishkov considers the French experience of nation-building an appropriate model for a multiethnic federation such as Russia, despite the former being treated as a textbook case of an assimilatory, anti-ethnic nation-building approach by scholars of nationalism (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2012).Footnote 6

Nor is the “conservative turn” incompatible with a commitment to multiethnicity. For one thing, the Kremlin’s focus on “traditional values” as central to the national community has not only been embraced by the Russian Orthodox Church, but has also preserved a degree of space for non-Orthodox communities to articulate distinct identity narratives (Yusupova Reference Yusupova2016; Sibgatullina Reference Sibgatullina2020). This convergence can be seen in the recent articulation of a supranational, “civilizational” understanding of identity, which leaves considerable ambiguity as to the boundaries of the in-group while allowing hybrid identities to exist at the sub-national level (Hale and Laruelle Reference Hale and Laruelle2021; Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023; Cerrone Reference Cerrone2023).

These ambiguities also extend to foreign policy. On the one hand, Russian foreign policy appeared to take a distinctly ethnonationalist turn in the 2010s. The 2014 annexation of Crimea and subsequent conflict in the Donbas were justified by the Kremlin in terms of the protection of co-ethnics and historical claims to Crimea as “historically Russian” territory (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016, 6). Starting in 2018 and leading up to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Putin’s presidential speeches also began to strongly favor the use of “russkii” over “rossiiskii” when making claims about historical relations with Ukraine and the West (Laruelle, Grek, and Davydov Reference Laruelle, Grek and Davydov2023, 16–17). Since then, the Kremlin has intensified its mythologization of Ukraine as part of a perceived “Russian world” [russkii mir], with officials regularly framing the invasion in ethnic nationalist language (The Moscow Times 2023).

On the other hand, however, many radical ethnonationalists were ultimately disappointed by Moscow’s partial and instrumental co-optation of Russian nationalism in the Donbas from 2014 (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2016a; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2016). Radical ethnonationalists have also been some of the Kremlin’s most ardent critics since February 2022, underscoring the extent to which such groups consider the government’s embrace of nationalism to be insincere and insufficient (Soldatov and Borogan Reference Soldatov and Borogan2022). Furthermore, the coalescence around conservative values and “civilizational” framings of identity have also allowed ethnic republics such as Chechnya and Tatarstan to partially compensate for their decreased autonomy at home by engaging in paradiplomacy abroad, notably in the Middle East (Galeeva Reference Galeeva2022; Klyszcz Reference Klyszcz2023).

In summary, both domestically and in foreign policy, a rhetorical commitment to the multinational nature of the Russian state has co-existed with attempts to amplify the significance of the ethnic Russian “core.”

2.1 Blurred semantic space between russkii and rossiiskii

To what extent is this ambiguity reflected in citizen attitudes? The blurred semantic space between russkii and rossiiskii presents a challenge for researchers: whilst in some cases russkii is used in a clearly ethnic sense, this is often highly contextual, preventing straightforward interpretation. Through the blurring and loosening of its ethnic connotations, russkii has been recast as both a state identity as well as functioning as a broader, “civilizational” identity united by values and adherence to the current regime (Goode Reference Goode, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2018; Hale and Laruelle Reference Hale and Laruelle2020; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2021; Laruelle, Grek, and Davydov Reference Laruelle, Grek and Davydov2023). Even seemingly clear-cut cases of Russian ethnic nationalism such as the slogan “Russia for Russians” [Rossiia dlia russkikh] are not always understood in exclusively ethnonationalist terms (Fediunin Reference Fediunin2023), rendering it a “crude measure” for ethnonationalism, since it doesn’t explain who the Russians are that it is referring to (Schenk Reference Schenk2012, 784). Indeed, survey data from 2013 find that when people were asked who the Russians were in “Russia for Russians,” only 39% opted for an exclusively ethnic definition (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016, 265). Thus, a shift towards the use of russkii does not necessarily imply a turn towards ethnic nationalism, but rather that the boundaries of russkii remain blurred (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2023).

Yet, rossiiskii also retains a considerable degree of ambiguity, despite being often framed as a civic term juxtaposed to a supposedly ethnic russkii. Indeed, as Goode has argued, President Yeltsin – often credited with pursuing a “civic” nation-building policy – did use the term rossiiskii to describe the nation but simultaneously presented the term in ways which privileged a perceived Russian ethnic ‘core,’ describing ethnic Russians “as the cornerstone of Russian statehood and their interests articulated in terms of all-state interests” (Goode Reference Goode2019, 151).

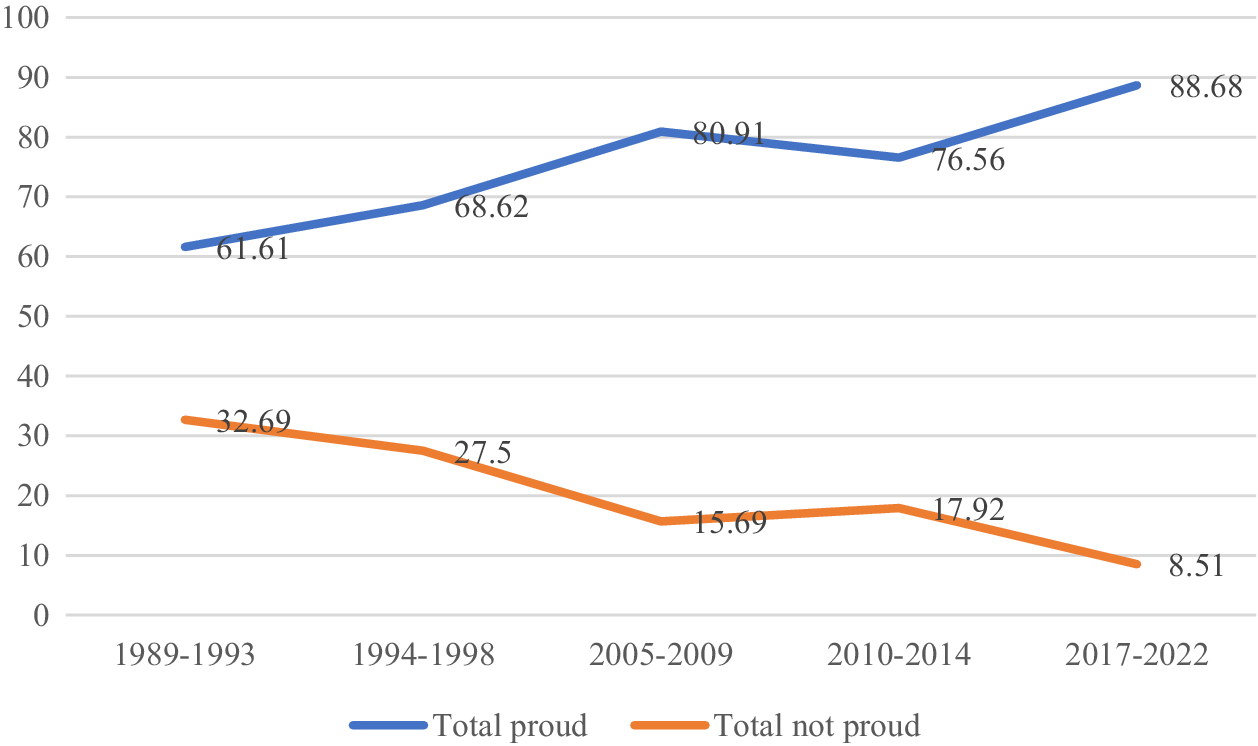

Existing survey data present a mixed picture of citizen “buy-in” to a rossiiskii identity. On the one hand, longitudinal data from the World Values Survey (WVS) suggest that growing numbers of Russians do display pride in their rossiiskii identity [Naskol’ko Vy gordites’ tem, chto Vy rossiianin?], as displayed in Figure 1 (Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Lagos, Norris, Ponarin and Puranen2022).

Figure 1. Russian citizens’ pride in rossiiskii identity [World Values Survey].

Moreover, while it is true that the term “Rossian” failed to resonate at the grassroots level in the 1990s, recent census data do suggest that after over 30 years of post-Soviet development, many citizens find the term to be sufficiently appropriate as a marker for respondents’ self-defined ethnicity. Indeed, 206,081 respondents declared their ethnicity to be “Rossian” in Russia’s most recent 2021 census – more than a tenfold increase since 2010. This makes “Rossians” the 28th largest ethnic group in Russia, comparable to the number of ethnic Belarusians (Lenton Reference Lenton2023).

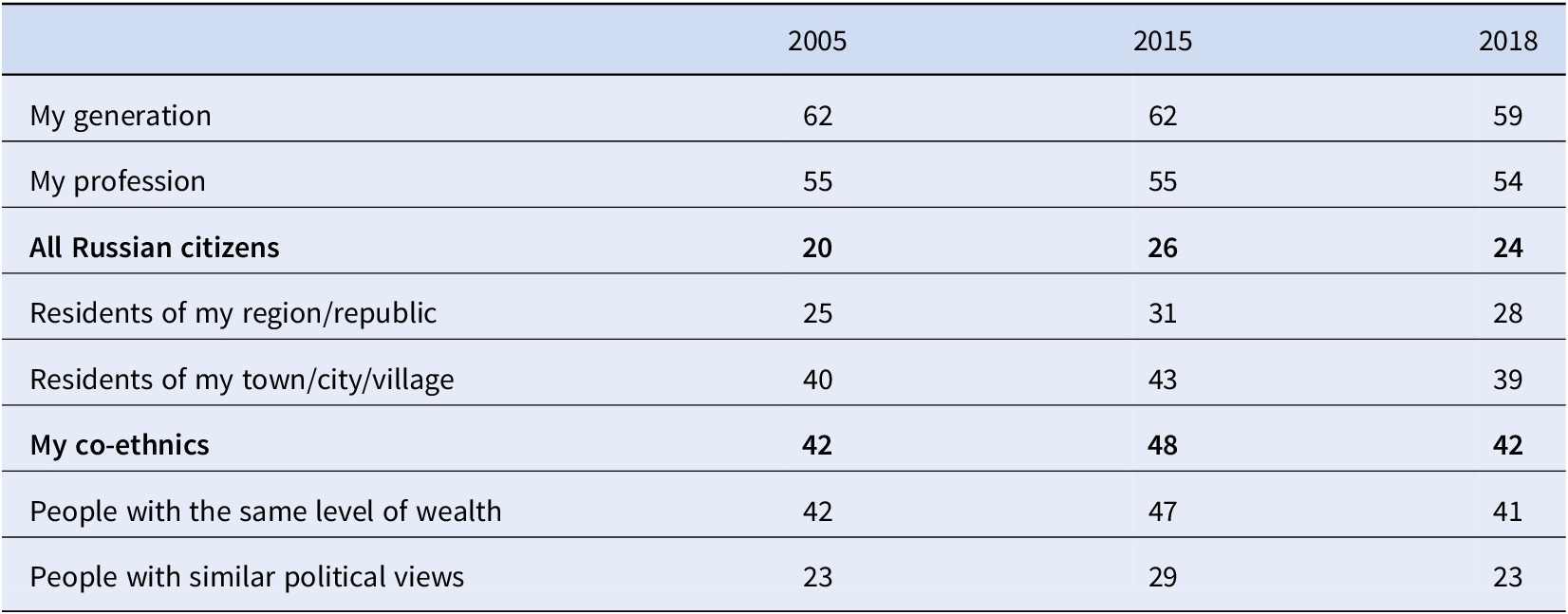

On the other hand, though, longitudinal studies carried out by the Russian Academy of Sciences continued to find that when asked the degree to which respondents “feel a sense of community, closeness with the following categories of people,” common citizenship is significantly less strong than ethnicity, as shown in Table 1 below (Drobizheva Reference Drobizheva2020; “Rossiyskaia Identichnost’ v Sotsiologicheskom Izmerenii” 2007).

Table 1. Feeling of community, closeness with the following categories, % responding “often” [Drobizheva Reference Drobizheva2020, Russian Academy of Sciences 2007]

3 Research design

To explore the extent to which russkii and rossiiskii may in practice overlap or be blurred, I included two questions in Levada Center’s monthly omnibus public opinion survey in Russia (N=1600), which was carried out in December 2022.Footnote 7

The first question, near the beginning of the survey, was a replication of a question posed across several sociological studies by Russian scholars since 1995, and asks respondents to select the statement they most agree with out of three possible options, which are as follows (respondents are also free to select “don’t know/hard to say”):

-

1. Russia is the shared home of many peoples, each influencing one another. All peoples of Russia should have equal rights, and nobody should have any advantages.

-

2. Russia is a multinational country, but ethnic Russians, comprising the majority, should have more rights, since they are predominantly responsible for the fate of the country.

-

3. Russia should be a state for ethnic Russians.

One advantage is that the question helps to neatly and unambiguously identify preferences that the semantic ambiguities discussed above can make challenging. Option 1 has been the default official position of the Russian government since 1992. Option 2 and 3 are both more clearly ethnic, hierarchical, and run counter to the Russian Constitution, though option 2 is arguably quite close to the government’s de facto position. Furthermore, fielding a question posed in multiple survey waves since 1995 allows for meaningful across-time trends to be drawn regarding citizen preferences.

The second question, asked towards the end of the survey, analyzes in greater detail the specific boundaries of the rossiiskii political community, asking respondents to assess “Which of the following groups, in your opinion, can be considered true Rossians [istinnymi rossiianami]”? This particular phrasing has been used in previous surveys (Levada Center Reference Center2012) to assess respondents’ subjective view of the ideal boundaries of the rossiiskii political community. Respondents are then presented a randomized list of categories and asked to rank them on a 4-point scale, where 4 represents “definitely can consider,” 3 represents “generally possible to consider,” 2 represents “generally not possible to consider,” and 1 represents “definitely cannot consider.” The categories are below:

-

1. All Eastern Slavs (Belarusians, Ukrainians)

-

2. People from other countries of the former USSR who consider themselves “Soviet people”

-

3. People of other traditional Russian religions who are not Orthodox (Islam, Buddhism, Judaism)

-

4. Atheists

-

5. Liberals

-

6. Russians who have left the countryFootnote 8

-

7. Ethnic minorities of Russia whose native language is not Russian

The rationale for selecting these categories was twofold. First, it builds upon previous scholarship’s insights on the changing dynamics of Russian identity by including categories which may plausibly exclude one from membership in russkii but not a broader, rossiiskii identity (Goode Reference Goode, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2018; Hale and Laruelle Reference Hale and Laruelle2020; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2021; Laruelle, Grek, and Davydov Reference Laruelle, Grek and Davydov2023). Indeed, all but (1) and (2) represent categories of people that unequivocally fall under the category of rossiiskii, being Russian citizens, making it possible to measure the relative degree to which certain groups are included or excluded from the boundaries of the political community and, by extension, the degree to which a rossiiskii identity may overlap with russkii. Second, it takes seriously the multidimensionality of national identities (Bochsler et al. Reference Bochsler, Green, Jenne, Mylonas and Wimmer2021). As a closed-ended question allowing respondents to rank several categories of potential “true Rossians,” it enables comparisons to be made between a broad possible range of components, including ethnic (1,2,3,8), religious (4,5), political (6,7), and linguistic (8).

It is also worth acknowledging some limitations. First, these categories are by no means exhaustive, and while the question offers insights into which components may be more or less necessary for consideration as a “true Rossian,” it is unable to provide insights into the relative salience of these components, nor is it able to indicate whether one, or a combination of components, is alone sufficient for consideration as a “true Rossian.”

There are also considerations when it comes to those categories (1, 2) which seek to capture overlap between non-citizenship and belonging in the Rossian political community. Absent the ability to disaggregate these further and with a limited number of categories, I decided upon two expansive renderings that seek to identify respondents’ attitudes to variations of “imperial” nationalism identified by previous research (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2016a; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2018, 7; Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø, Blakkisrud, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2018, 5). The first category sought to approach this from the perspective of East Slavic ethnicity, which includes both citizens of Russia and of other countries. The second sought to approach this from the perspective of identification with the Soviet Union in a way which was not explicitly ethnic, i.e., being neither rossiiskii nor necessarily russkii. That said, both categories would include ethnic Russians living abroad, and respondents may conceivably have had this community in mind when presented with these categories. As such, caution should be exercised when drawing conclusions from these categories beyond the degree to which non-citizenship may or may not be seen as compatible with a broader Rossian political community.

A final consideration is that these results represent a single snapshot of attitudes during wartime (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2022). Pressures to dissemble or misrepresent true beliefs out of considerations of social desirability (Hale Reference Hale2022) or fear of punishment (Reisinger, Zaloznaya, and Woo Reference Reisinger, Zaloznaya and Woo2022) may all be pertinent in the context of Russia in December 2022. I address these considerations in the following section.

4 Results and analysis

4.1 Majority support for a multinational state

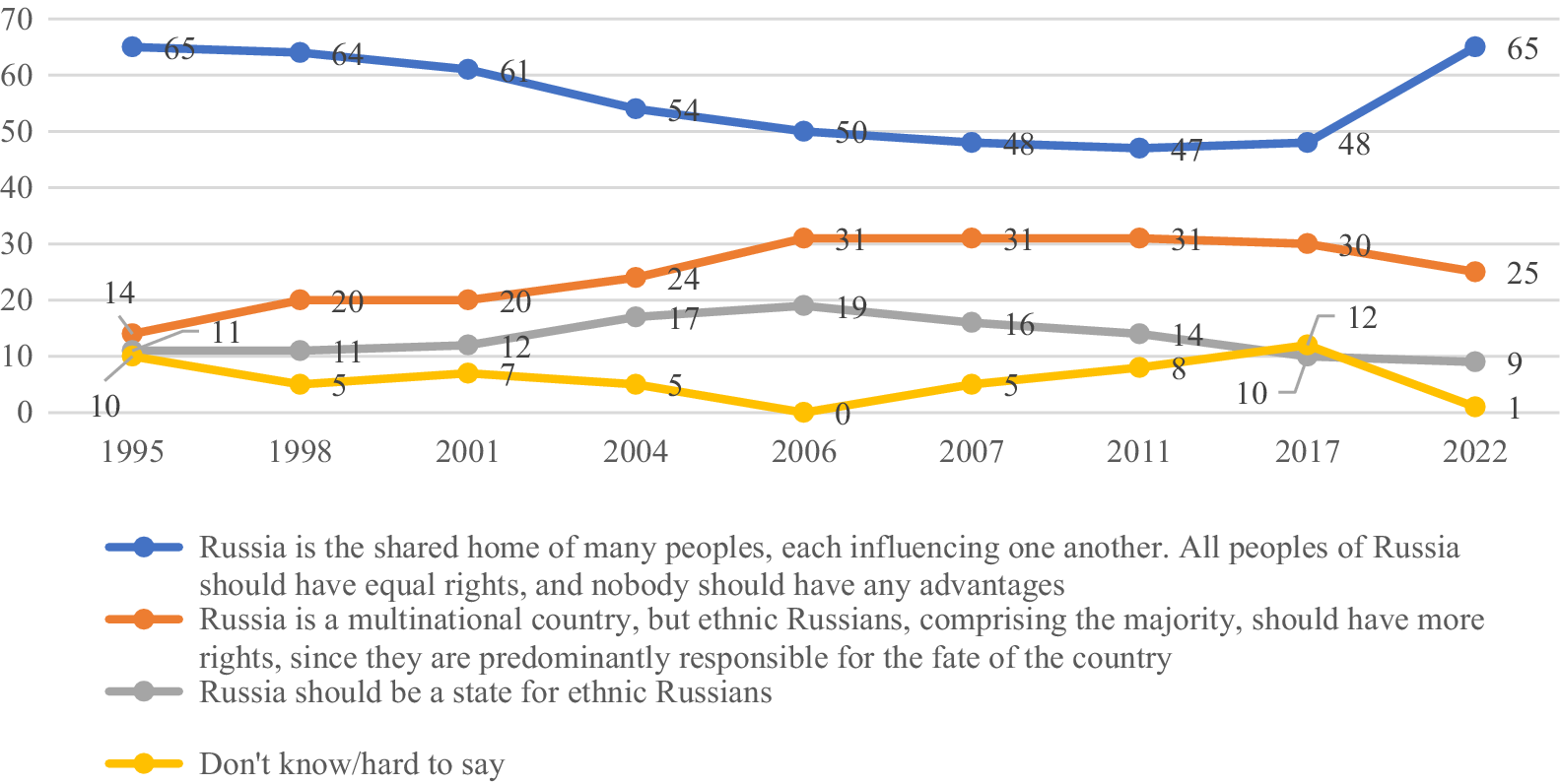

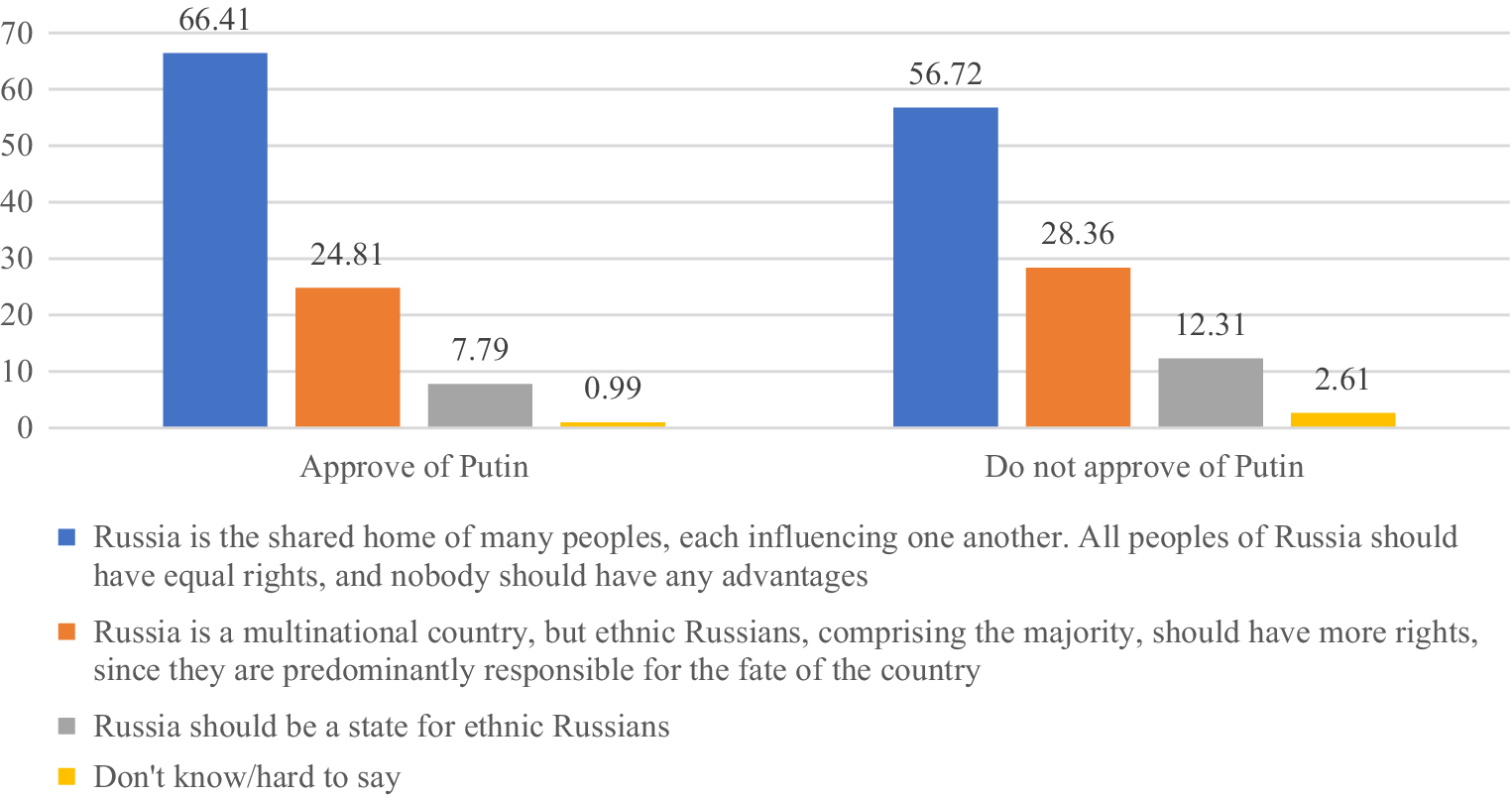

Figure 2 below presents longitudinal trends in Russian citizens’ attitudes towards the multinational character of the Russian state, compiling previous iterations of this question as reported from different sources (from 1995 through 2017), together with the response from the Levada omnibus in December 2022 (“Rossiiskaia Identichnost’ v Sotsiologicheskom Izmerenii” 2007, 96; Gorshkov, Krumm, and Petukhov Reference Gorshkov, Krumm and Petukhov2011, 207; Drobizheva Reference Drobizheva2018, 110). A couple of trends are noteworthy. First, Russian citizens have consistently displayed preferences for a multinational state, while only between 10-20% have opted for the ethnocentric, exclusionary “Russia for [ethnic] Russians.” This is not to say, however, that respondents eschew ethnocentric attitudes altogether. In fact, a sizeable – and growing – minority of respondents had opted for the second option throughout the 2000s and 2010s, embracing Russia’s multinational character while nevertheless positing that ethnic Russians constitute a privileged “core.” Second, the results from the December 2022 omnibus show that Russians continue to prefer a multinational state, with the level of support in 2022 at its highest point since 1995. While the magnitude of this increase is likely in part to a reduction in “don’t know/hard to say” responses in 2022 compared to 2017, the increase cannot fully be attributed to this. Similar results hold across the political divide, too, as shown in Figure 3. Those who disapprove of Putin tend to be less supportive of a multinational state – a trend which is discussed in more detail below – but even in this case a majority still expresses support for a multinational state. Moreover, two-sided t-tests compared the differences in means among those who expressed support for Putin versus those who did not: for all options except the second (“Russia is a multinational country…”) the means were statistically significant at the conventional p < 0.05 level, meaning that we can be confident that these differences are not due to chance alone.

Figure 2. Attitude of Russian citizens to the multinational character of the Russian state, % (one response allowed).

Figure 3. Attitude of Russian citizens to the multinational character of the Russian state by support for Putin, % (one response allowed).

4.2 “True” Rossians culturally Russian (russkii) and politically loyal

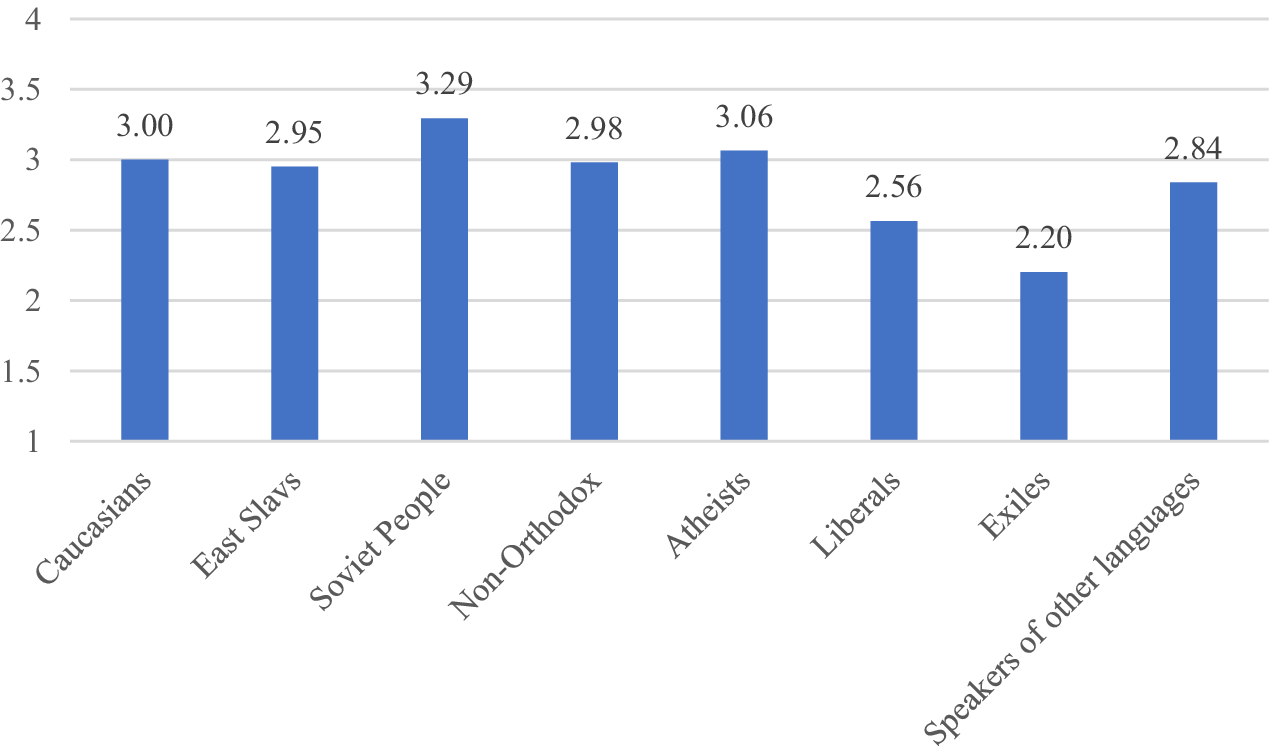

When later asked who counts as “true Rossians,” however, a more complex picture emerges. Figure 4 below shows the average score across the 8 categories asked, where 1 represents “definitely cannot be considered” and 4 represents that the group “definitely can be considered” true Rossians.Footnote 9

Figure 4. Which of the following groups, in your opinion, can be considered true Rossians [istinnymi rossiianami]? Average values, excluding “don’t know/hard to say”.

One thing to point out from the onset is that all these groups’ average score is lower than 4, meaning that all of the above categories are perceived to depart from fully belonging in the rossiiskii political community by respondents. At the same time, though, many of the results are around 3.0 out of 4, indicating that on average people considered that it was “generally possible to consider” these groups as “true Rossians.” Nevertheless, these findings also indicate that departure from russkii characteristics – being of Caucasian ethnicity, non-Orthodox faith, or being a speaker of another language – tends to exclude one from full consideration as a “true Rossian”, even though all these groups are Russian citizens. Of these, language appears to be slightly more important, as indicated by the fact that the lowest score among these is for ethnic minorities whose native language is not Russian.

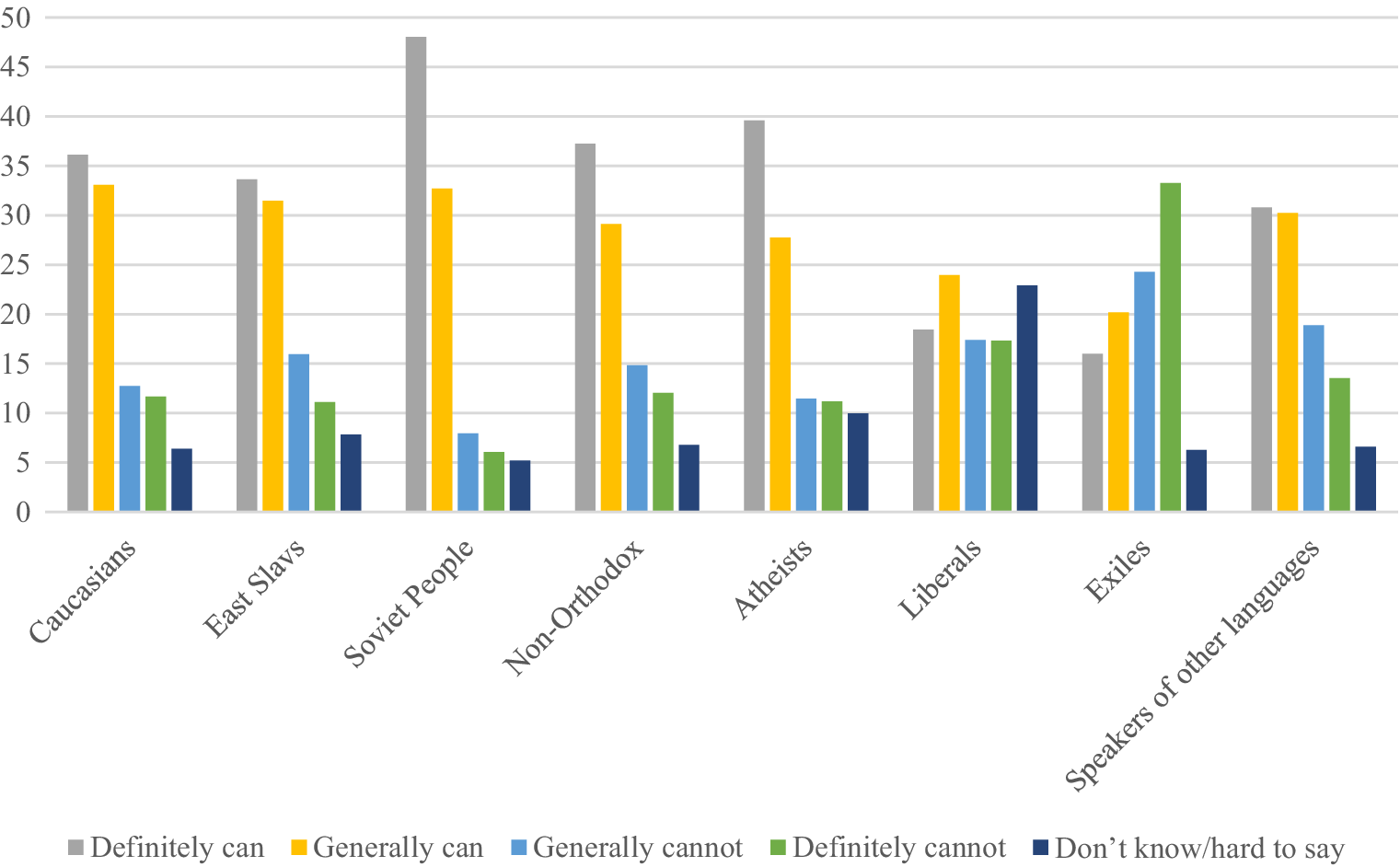

The starkest findings, however, were related to political attitudes. Both liberals and exiles were the lowest-ranked groups by some margin. These findings are consistent with a similar survey conducted by Levada Center in 2012 which found both russkii characteristics and respect of Russia’s political system to qualify one for membership as a “true Rossian” (Levada Center Reference Center2012). While leaving Russia appears to heavily disqualify one from being considered a “true Rossian” in the eyes of respondents, almost 25% of respondents selected “don’t know/hard to say” when it came to liberals (compared to just 7% for exiles), as indicated in the rightmost bars in Figure 5. The high non-response rate for liberals may reflect the fact that it remains a more ambiguous political category in its relationship to the national community. Interestingly, respondents’ greatest consensus formed around the only group which does not consist of Russian citizens – people from former Soviet countries who consider themselves to be “Soviet people.” This was also the category in which there were fewest “hard to say” responses and the standard deviation was the lowest. Put simply, responses were consistently inclusive towards this group.

Figure 5. Which of the following groups, in your opinion, can be considered true Rossians [istinnymi rossiianami]? Percentage of respondents.

4.3 Variation by socioeconomic and political factors

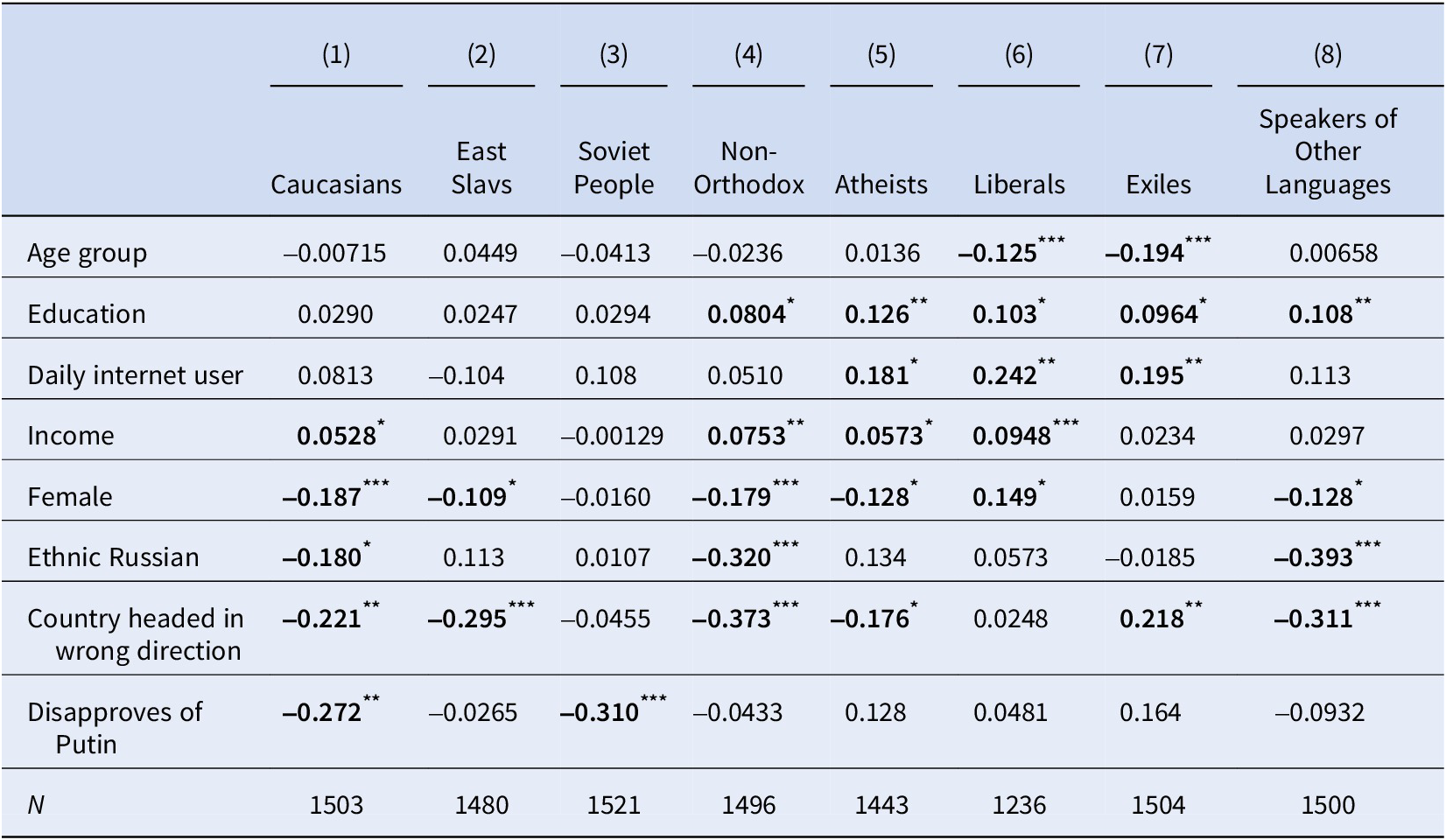

One way to further analyze the data is to see which types of respondents are more likely to be inclusive or exclusive towards the categories presented. To do this, I ran multiple regression models, drawing from socioeconomic and political questions posed by Levada Center earlier in the survey. Results are displayed in Table 2. The dependent variable across the models is the degree to which a specific group can be considered “true Rossians” according to respondents. The independent variables examine the specific effect of a marginal increase in that factor when holding all other factors constant. The values display the average predicted effect of a 1-unit increase in the given variable on the degree to which the corresponding category of people can be considered “true Rossians,” holding constant all other variables. Those values marked in bold meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05) meaning that we can be confident that these patterns are not the result of chance alone.

Table 2. Effect of socioeconomic and political variables on whether a respondent considers a given group to be considered “true Rossians”

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. OLS, no weights or clustering of standard errors. N refers to the number of observations. “Don’t know” responses were dropped, accounting for differences in the number of observations. Variables are coded 0 or 1, except for “income” (measured 1-4 where 4 represents the highest quartile of income and 1 the lowest), “education” (measured 1-3 where 1 represents middle school or below, 2 represents high school education, and 3 represents higher education), and “age group” (measured 1-4 where 1 represents 18-30, 2 represents 31-39, 3 represents 40-55, and 4 represents 55+).

Several noteworthy patterns emerge from the data. First, disapproval of the government predicts less inclusivity towards ethnic minorities. This is the case for those respondents who consider that the “Country is headed in the wrong direction,” as well as those who do not approve of Putin’s performance as president. Ethnic Russians are also much less likely to consider Caucasians, non-Orthodox Russian citizens, and speakers of other languages as “true Rossians.” These findings are consistent with previous research which has found that opposition to Putin and Russian ethnicity tend to be associated with greater xenophobia towards ethnic minorities (Gerber Reference Gerber2014; Herrera and Kraus Reference Herrera and Kraus2016; Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Marquardt, Herrera and Gerber2018). The size of these effects is also substantively significant; holding all other variables constant, believing that the country is headed in the wrong direction predicts over a 12% decrease in inclusiveness towards considering non-Orthodox Russian citizens as “true Rossians.”

Second, socioeconomic factors such as wealth and education predict marginally more inclusive attitudes, most commonly towards political opponents and nonreligious Russians. Media consumption – in this case, whether a respondent uses the internet daily – is associated with more positive attitudes towards atheists, liberals, and exiles, while greater education predicts more inclusion towards all categories.

Finally, there is a noticeable gender divide in the results: female respondents in the survey were more inclusive of liberals but less inclusive of other identity groups. These relationships are mostly statistically significant across the models, and contrast with findings from previous survey-based research on Russian nationalism, which has found the opposite (Gerber Reference Gerber2014; Herrera and Kraus Reference Herrera and Kraus2016). One explanation may be related to the specific international context in December 2022. In analyzing longitudinal data from the European Social Survey, Andrey Shcherbak notes that Russian women consistently held more conservative attitudes than men, except for in 2014, which he concludes is due to the “rally-round-the-flag” effect being “probably mostly a male story” (Shcherbak Reference Shcherbak2022, 213). Indeed, experimental evidence from 2015 found that reminding people about the Crimea annexation created a significant bump in support for Putin among male respondents but not among women (Hale Reference Hale2018, 375). If a “rally-round-the-flag” effect were taking place in Russia in December 2022 and embraced by men in similar ways to that of 2014, this might explain why women are more inclusive than men of opposition-leaning groups such as liberals and exiles.

Available evidence certainly points to a gendered difference in attitudes towards the war. For one thing, the war has been presented inside Russia in a highly masculinized form (Wood Reference Wood2024, 2), which may help to account for why women appear less supportive of the war than men. Military bloggers – a predominantly male group – have become key opinion leaders in the wake of the full-scale invasion, with hundreds of thousands and even millions of followers (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2024, 24). In contrast, emerging research has found women to be more active on anti-government YouTube channels (Savchenko and Freedman Reference Savchenko and Freedman2024). These differences also appear in public opinion data: as recently as September 2024, Levada Center data show that 62% of women endorsed beginning peace talks (compared to 45% of men) while 55% of women (compared to 38% of men) considered the so-called “Special Military Operation” to be more harmful than beneficial (Levada Center Reference Center2024).

This, however, does not in itself account for the gendered difference in attitudes towards religious and ethnic minorities. While the survey data here are limited in their ability to fully explain these findings, they do reveal important gendered differences that future research designs may be able to test. One such possibility is that it is a side effect of the sort of rallying identified above, whereby an overall bump in support for the war among Russian men has also led to greater inclusiveness towards ethnic and religious minorities. Given that the contributions of ethnic and religious minorities in the Russian military are prominent in the narratives of the Kremlin and military bloggers, this appears a plausible explanation.

An alternative explanation may be that there are greater rates of survey misreporting among male respondents due to the greater fear of repression (and direct risk of being mobilized). That said, I do not think that the post-2022 repressive environment is systematically biasing these results, for instance through systematically misreporting true attitudes. For one thing, respondents were free to select “don’t know/hard to say” for the questions posed and any of the categories in the second question: almost a quarter did exactly this for the category of “liberals,” per Figure 5. Moreover, if respondents were deliberately misreporting based on what they perceived the Kremlin wanted them to select, then the findings here strongly suggest that it is in the direction of indicating support for Putin and displaying more inclusive attitudes towards ethnic minorities. In other words, if we believe such misreporting is occurring, then the explanation is that it is because people believe the Kremlin supports a multinational state and therefore respondents express more inclusive attitudes.

Crucially, if this were the case, it would also mean that the rossiiskii category analyzed here is more ethnically exclusive in the eyes of respondents than the values presented in Figure 4. Of course, another explanation may be that misreporting may be taking place for some questions but not others. For instance, respondents could be misreporting their true opposition to Putin but not misreporting responses related to the nation. Yet even in this case, this would not invalidate the overall findings on attitudes towards the nation, though it might account for some of the differences across political and socioeconomic groups’ responses. Future research might explore the gendered effects of the war on nationalist attitudes, or examine citizens’ understandings of what Putin’s stance on the nation is, in order to further evaluate these findings.

5 Conclusion

This article explores developments in Russian nationalism and nation-building. Its findings make two contributions to scholarship. First, they provide quantitative evidence that a rossiiskii identity is multifaceted, and should not be seen as an exclusively “civic” or non-ethnic identity category juxtaposed to an “ethnic” russkii one. Use of russkii or rossiiskii alone is likely insufficient to infer the degree to ethnic inclusivity of populations without further contextualization, which has implications for researchers working on issues of identity in the Russian context, particularly those who use surveys or other quantitative data. Further investigation might explore which categories are seen to be as sufficient for consideration as russkii/rossiiskii, as well as the relative salience of different categories.

Second, the evidence points to some of the political drivers of nationalist attitudes and preferences during wartime Russia. Support for a multinational state reached its highest level in 2022. That said, this support coexists with a tendency to exclude groups who depart from russkii characteristics from fully being considered “true Rossians”. This tension of embracing a multinational vision of the state while simultaneously privileging ethnic Russians as the “core” of an imagined rossiiskii political community is not simply a top-down phenomenon, but also appears consistent with how citizens themselves understand the boundaries of the political community. Rather than be understood as a bug, this should be seen as a feature of Russia’s nation-building approach; indeed, nation-builders in multiethnic countries may have incentives to both cater to ethnic majorities while simultaneously signaling commitments to ethnic diversity.

This approach – one that is “multinational in form, russkii in content” – did not emerge in February 2022 but has maintained its relevance for contemporary Russian nation-building. Starker, however, were the exclusionary attitudes towards political, rather than ethnic categories of Russian citizens such as liberals and exiles. At the same time, disapproval of Putin predicts more ethnically exclusionary attitudes. Perhaps most surprising of all was that the group of individuals most likely to be considered “true Rossians” was the only group that unambiguously does not consist of Russian citizens: citizens of former Soviet states who consider themselves to be “Soviet people.” This finding suggests that the boundaries of the nation as perceived by Russian citizens may be situationally flexible, both regarding the role of ethnicity as well as citizenship therein.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Zsuzsa Csergo, Nathaniel Knight, and participants of the DC Area Postcommunist Politics Social Science Workshop and 2024 Association for the Study of Nationalities (ASN) Convention for helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. All errors remain my own.

Financial support

Funding for this research was supported by a Carnegie/Harriman Research Grant for Ph.D. Students in the Social Sciences.

Disclosure

None.