Introduction

On February 24, 2022, Russians awoke to a new reality with the declaration of a Special Military Operation by President Vladimir Putin and the launching of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Internationally, the war effectively closed off any avenues for Russia to restore antebellum normality, either politically for Russia’s government or economically with the imposition of unprecedented and sweeping sanctions. From February through September 2022, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine stagnated as it retreated from Kyiv, demolished Mariupol in order to occupy it, and failed to make significant advances on the eastern front. In domestic politics, the Russian government moved quickly to stifle opposition and dissent while committing the nation to war. The underlying message for Russians was clear: there would be no going back to the world before the invasion.

This article argues that depictions of the occupied territories on Russian television demonstrate how autocracies produce banal nationalism in unsettled times. The success of official nationalism in autocracies depends upon their successful monopolization of autocratic expression. However, unsettled times create demands for a return to normality, often envisioned as the status quo ante, that potentially pose political threats to autocracies. In Russia’s war, returning to normality as an achievable goal was displaced from Russia to the “return” of Ukrainian regions annexed by Russia on September 30, 2022: the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, as well as Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts. Today, televised coverage of occupied territories in Ukraine, referred to as the “new regions” [novye regiony], focuses on (re)building, returning, and restoring normal life. Just as the state appropriates everyday nationalist practices in national commemorations and memory politics, such performances in occupied territories are marshalled in Russian propaganda to demonstrate a return to normality. The voices and depictions of residents of the “new regions” confer emotional weight on these portrayals while providing moral examples for ordinary Russians — for example, though their fortitude in voting for Putin despite ongoing attacks; through their shared excitement in acquiring routine aspects of daily life from passports to pensions; and through their embodiment of Russia’s future.

This article begins with a brief overview of the theoretical literature on everyday nationalism and banal nationalism in autocracies. While banal and everyday nationalism as a general class of social and political phenomena are found in all kinds of states and regimes, most of the literature focuses on democratic or democratizing states in such a way that it often sidesteps the distinctive ways that regime type influences the structure and practice of national expression. Moreover, studies of everyday nationalism and banal nationalism typically focus on “settled times,” which are characterized by a low degree of uncertainty about the stability and persistence of social and political institutions. In settled times, banal nationalism tends toward the reinforcement of social structures, while everyday nationalism challenges it through a multitude of daily practices and routines. However, this relationship is upended during “unsettled times” in which official nationalism attempts to rationalize changing social and political orders while everyday nationalist practices seek a return to normality.

Today’s Russia provides a vivid illustration of these processes whereby the politics of banal and everyday nationalism in unsettled times are mediated by autocracy. Russia steadily autocratized under Vladimir Putin’s rule, with a marked growth of official (some might say imperial) nationalism over the decade since the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the undeclared war in Eastern Ukraine in 2014. Russia arguably never exited the protracted period of “unsettled times” that began with COVID-19 in 2020–2021, moving quickly from pandemic to war: before there were Zs on Russian tanks invading Ukraine, there was Sputnik V.

While one could imagine a return to normality after the pandemic, the launching of a full-scale war against Ukraine effectively closed off any avenues for Russia to restore antebellum normality. Consequently, this article argues that Russia (re-)produces banal nationalism by normalizing the war for its citizens and co-opting everyday nationalist practices in support of the “new normal” through its depiction of the “new regions.” An essential part of this co-optation of grassroots practices into the state’s repertoires is their recirculation in society through state-controlled media. After discussing the concepts of banal and everyday nationalism in relationship to autocracy and unsettled times, the analysis turns to depictions of the “new regions” on Russian television, focusing on the ways that the occupied territories are portrayed as returning to normality, inscribed into national holidays and commemorations, and embodied through emotional displays of joy and gratitude.

Banal and Everyday Nationalism in Autocracies

While nationalism is broadly understood to be a doctrine of popular sovereignty, the bulk of the literature on nationalism focuses on elite articulations of the nation in the course of contentious events while treating the popular resonance of nationalism as a given. Starting in the mid-1990s, scholars began to question this assumption and focused their attention on the various ways that the nation is reproduced in informal, routine ways (Billig Reference Billig1995; Palmer Reference Palmer1998; Skey and Antonsich Reference Skey and Antonsich2017), popular culture (Edensor Reference Edensor2002), and finally people’s everyday practices (Brubaker et al. Reference Brubaker, Feischmidt, Fox and Grancea2006; Fox and Miller-Idriss Reference Fox and Miller-Idriss2008). The crucial insight linking all of these works is that nationalism is pervasive even in “settled times” — not just in the midst of eventful social and political change (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2016). As Wilmers (Reference Wilmers2022) observes, notions of national continuity and progress are “constitutive components of banal nationalism.” Viewing nationalism as embedded in informal, routine daily existence further addresses two of the most common critiques of instrumentalist accounts of nationalism: it accounts for nationalism’s seemingly hidden persistence through time, as well as the variability of its emotional power.

The concepts of banal and everyday nationalism are often conflated in practice. To be sure, there is significant overlap among them with reference to the nature of agents (non-elites) and the contexts within which they act (routine, informal). However, they differ in terms of the scale of observed social interactions: whereas the heavy lifting in banal nationalism is performed by focusing on social structures (like the ubiquitous unwaved flags found in front of government buildings), everyday nationalism is distinguished by its focus on social practices (such as talking, choosing, performing, or consuming the nation) as driving observed outcomes (Goode Reference Goode2020a).

The focus on social practices as the unit of analysis is a key methodological move that makes it possible to examine how everyday nationalism overlaps with other categories of practice (Goode and Stroup Reference Goode and Stroup2015), including the practices that sustain ethnic minority boundaries (Brubaker et al. Reference Brubaker, Feischmidt, Fox and Grancea2006; Stroup Reference Stroup2022), co-create authoritarian rule (Dukalskis and Joo Reference Dukalskis and Joo2021; Glasius Reference Glasius2018; Greene and Robertson Reference Greene and Robertson2019; Sharafutdinova Reference Sharafutdinova2020) or constitute the “practice turn” in international relations (Adler and Pouliot Reference Adler and Pouliot2011; Adler-Nissen Reference Adler-Nissen2016; Bueger and Gadinger Reference Bueger and Gadinger2018; Gaufman Reference Gaufman2023). By contrast, the relationship between banal nationalism and autocracy remains underexplored. Banal nationalism conceptually assumes an already-existing relationship between state and nation such that the mode of that relationship is not explicitly theorized. To some extent, this oversight is understandable given that its conceptual focus concerns identifying ways that nations persist in a pervasively unnoticed fashion, while there is an enormous existing scholarship on nation-building and the origins of nationalism. Yet, if we are to close the gap between banal and everyday nationalism, we can look to domestic political regimes as mediating the relationship between state and nation, and particularly between (re)production of the nation as social structure and the ways the nation is experienced and practiced by individuals in their daily lives.

The process by which banal nationalism is produced (for example, in the wake of revolution, regime change, or state creation), or “banalization,” varies among democracies and autocracies.Footnote 1 In democracies and democratizing states, open competition among multiple autonomous actors in politics, the economy, and civil society incentivizes national expression. The content and boundaries of national identities develop through competitive dynamics, eventually settling on a finite (albeit flexible) range of national images and claims. Incentivization ultimately succeeds as a means of producing banal nationalism when citizens come to care about the contestation of national symbols and repertoires as a routine matter. By contrast, autocracies prefer instead to monopolize national expression to exclude challengers while cultivating competitive, routinized displays of loyalty. Monopolization succeeds to the extent that citizens cease to care about the routine imposition of national symbols and repertoires by the regime in public life.

In Russia’s case, monopolization unfolded from the start of Vladimir Putin’s rule with a particular emphasis on the top-down promotion of Soviet-style patriotism and commemoration of the memory of the Great Patriotic War (Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2009; McGlynn Reference McGlynn2023a). The state provided resources and platforms for (carefully curated) national expression in the form of official patriotism. However, official patriotism often failed to connect with Russians’ everyday senses of the term, especially with regard to emotional appeal or resonance (Goode Reference Goode2016; Reference Goode, Skey and Antonsich2017). It has long been understood that elites’ national projects must resonate with the people if they are to be perceived as meaningful (Whitmeyer Reference Whitmeyer2002). Sensing this gap, the Kremlin pointedly sought to co-opt everyday practices that conferred emotional authenticity. For commemorations of the Great Patriotic War, a telling case was the grassroots Bessmertnyi Polk [Immortal Regiment], which began in Tomsk alongside the official Victory Day parade and quickly gained in popularity until it was taken over by the state (Hobson Reference Hobson2016; Kurilla Reference Kurilla2023). The media plays a crucial role in the state’s monopolization strategy, especially in making up the gap between official and everyday patriotism. For example, in claiming and reproducing Russians’ everyday activities as evidence of support for government policy in Eastern Ukraine (prior to 2022) and Syria, Russia’s media sought to persuade viewers that their neighbors were patriots by projecting a “congruence between ordinary people’s everyday nationalism and the state’s own policies” (McGlynn Reference McGlynn2020, 1079). Similarly, the projection of everyday patriotic practices was later used to consolidate support for constitutional amendments that extended Putin’s rule (Goode, Reference Goode2021b).

Nationalism in Unsettled Times

Banal nationalism and everyday nationalism are associated with the routine reproduction or challenging of the status quo national order during “settled” or “quiet” times (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2016; Goode Reference Goode2012), in contrast with “hot” or “noisy” nationalisms that mobilize against the state during eventful or contentious politics (Jones and Merriman Reference Jones and Merriman2009). However, the politics of banal and everyday nationalism invert this relationship during “unsettled” times. Crisis events (like war or pandemic) create a sense of ontological instability by overturning assumed practices of nationhood and challenging the established symbolic order (Skey Reference Skey2011, 115). Unsettled times are thus periods marked by ontological uncertainty, when one can no longer take for granted “the future of social and political structures within which routine social practice takes place and derives meaning” (Goode, Stroup, and Gaufman Reference Goode, Stroup and Gaufman2022, 63).Footnote 2

During unsettled times, everyday nationalism manifests in attempts to recreate, reproduce, or maintain the routine practices associated with the nation’s normal existence. The recent experience of the COVID-19 pandemic provides a telling account of the risks that ruptures to normality present for autocracies. Chenchen Zhang (Reference Zhang2022) uses the term “disaster nationalism” to characterize the Chinese state’s attempt to manage the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic by repurposing existing banal nationalist narratives while appropriating everyday nationalist content to lend emotional weight. Zhang observes that the state’s management of national expression was challenged by the crisis, as “grieving in ways that demand recognition of structural failure or political responsibility can be fundamentally unsettling to the existing political order” (Zhang Reference Zhang2022, 227).Footnote 3

Disruptions to everyday life can further inflame ethno-nationalist sentiment among majorities, who come to view minorities’ public practices as rendering them outsiders and scapegoats for upending normality. In documenting the rise of Islamophobic discourse targeting China’s Hui minority during the pandemic, David Stroup (Reference Stroup2024, 1075) explains that, “those who violate what nationalists believe the nation ought to be, become themselves manifestations of disease to the nationalists who abuse them and their outward otherness a sign of contagion.”

Narrating national tragedy in China thus involved a combination of prior-existing media repertoires: celebrating the people’s heroism through sacrifice, reproducing victimhood in relation to the West, and reinventing the nation’s “seemingly timeless past” as perpetual survivors. Narratives of heroism particularly lent themselves to militarized language that demanded both gratitude and national unity. To provide emotional depth to these discourses, the state curated and promoted accounts of everyday heroism. At the same time, victimhood narratives provided the grounds and emotional disposition for rejecting the West’s criticisms as unjust and motivated by geopolitical interests (Zhang Reference Zhang2022, 230–36).

Russia’s own experience during the pandemic echoed China’s in certain respects. In responding to the pandemic, Russia’s state agencies echoed China’s strategy in cultivating online narratives about the state’s persistence in the face of crisis while depicting the West as a hostile force (Moral Reference Moral2024). Putin’s attempt to reassure the nation that Russia would survive the crisis recalled obscure historical refences (“Our country has gone through serious trials more than once: both the Pechenegs tormented it, and the Polovtsy — Russia coped with everything. We will defeat this coronavirus infection too.”) did little to encourage trust in government. On the contrary, “the unusual historical reference to the battles from almost a millennium ago that most Russians barely remember from their school history classes had the opposite effect and the RuNet clapped back hard” (Gaufman Reference Gaufman2023, 124).Footnote 4 The population’s low trust in Russia’s government also contributed to poor uptake in the domestically produced Sputnik V vaccine, which proved to be more impactful in Russia’s foreign policy (Gaufman Reference Gaufman2023, 119–120).

As Russia stumbled out of the pandemic, its neo-imperial rhetoric regarding Ukraine increased markedly with Putin’s article published in the summer of 2021 (Putin Reference Putin2021) and non-stop troop exercises on Ukraine’s border. In relations with the West, the Kremlin presented an ultimatum to roll back NATO’s presence in Eastern Europe to pre-1997. The decision to annex the separatist republics in Eastern Ukraine and the launching of full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 might thus be viewed as part of a continuous process rather than a disruption — perhaps most poignantly exemplified by a COVID crisis call center in Siberia that switched seamlessly to providing mobilization information for panicked wives and mothers (Balzer Reference Balzer2023). In effect, Russia never returned to “settled” times but instead created a new crisis in Ukraine of global proportions that forestalled any possible return to the status quo ante.

The Banal Politics of Neo-imperial Expansion

From a postcolonial perspective, today’s Russia continues the Tsarist and Soviet-era imperial projects with its war in Ukraine (Khylko and Khylko Reference Khylko and Khylko2024). Pain (Reference Pain, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016, 51) identifies core elements of imperial nationalism that have remained active in Russia’s politics since the 19th century: the claim of essentialism of the Russian people as distinct from the West; a defensive imperial character that aims at the preservation of empire; and the principle of the political domination of ethnic Russians.

The neo-imperial elements in Russia’s domestic politics further manifest in its relations with former colonies in Eurasia (Kang Reference Kang2020). At the root of Russia’s neo-imperialism is a claim to a civilizing mission that is premised upon a belief in Russia’s cultural exceptionalism and its asymmetric relationship with former colonies (Oskanian Reference Oskanian2018). Russian neo-imperialism presents “a set of mechanisms for the dissemination of Russian culture through various ideological apparatuses, such as religion, culture, education, or the media,” at the core of which is the sacralization of Russia’s political power (Zaporozhchenko Reference Zaporozhchenko2024, 126). While there may be tensions among Russian elites in domestic politics about the utility and goals of imperial expansion (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2022), their interactions with former colonies continue to feature expectations of political loyalty, knowledge of the Russian language, and unity in opposition to the West (Kassymbekov and Marat Reference Kassymbekova and Marat2022).

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 laid bare the merging of nationalism and neo-imperialism. The formal justification for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine — of preventing “genocide” in the Donbas regions — aimed “to correct the allegedly mistaken cultural code of Ukrainianness which does not recognize the superiority of Russianness, the Russian nation, culture, history and language” (Mälksoo Reference Mälksoo2023, 476). In the occupied territories of Ukraine, Russia’s neo-imperial policies entail rewriting Ukrainian history, forced passportization and indoctrination, torture and abductions, and cultural destruction. Oksamytna (Reference Oksamytna2023, 505) observes that the actions of Russian forces in Ukraine further “bore all hallmarks of imperial violence, including sexual abuse, the looting of cultural artifacts, dispossession, ethnic cleansing, and forced recruitment of people on occupied territories into the imperial army.”

The persistence of neo-imperialist motivations provides a politically convenient bridge between settled and unsettled times in the course of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, while official patriotism facilitates the merging of nationalist and neo-imperial sentiment. Indeed, an important and oft-overlooked facet of Russia’s official patriotism is its neo-imperial dimension. Part of the reason for this oversight is suggested by Pål Kolstø’s (Reference Kolstø2019) observation that patriotism is often treated as distinct from nationalism because it does not fit the Gellnerian definition of nationalism, while nationalism and imperialism are often treated as opposite concepts. Nevertheless, “the ideal of the Empire is alive and kicking among contemporary Russian nationalists of various hues” (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2019, 38).

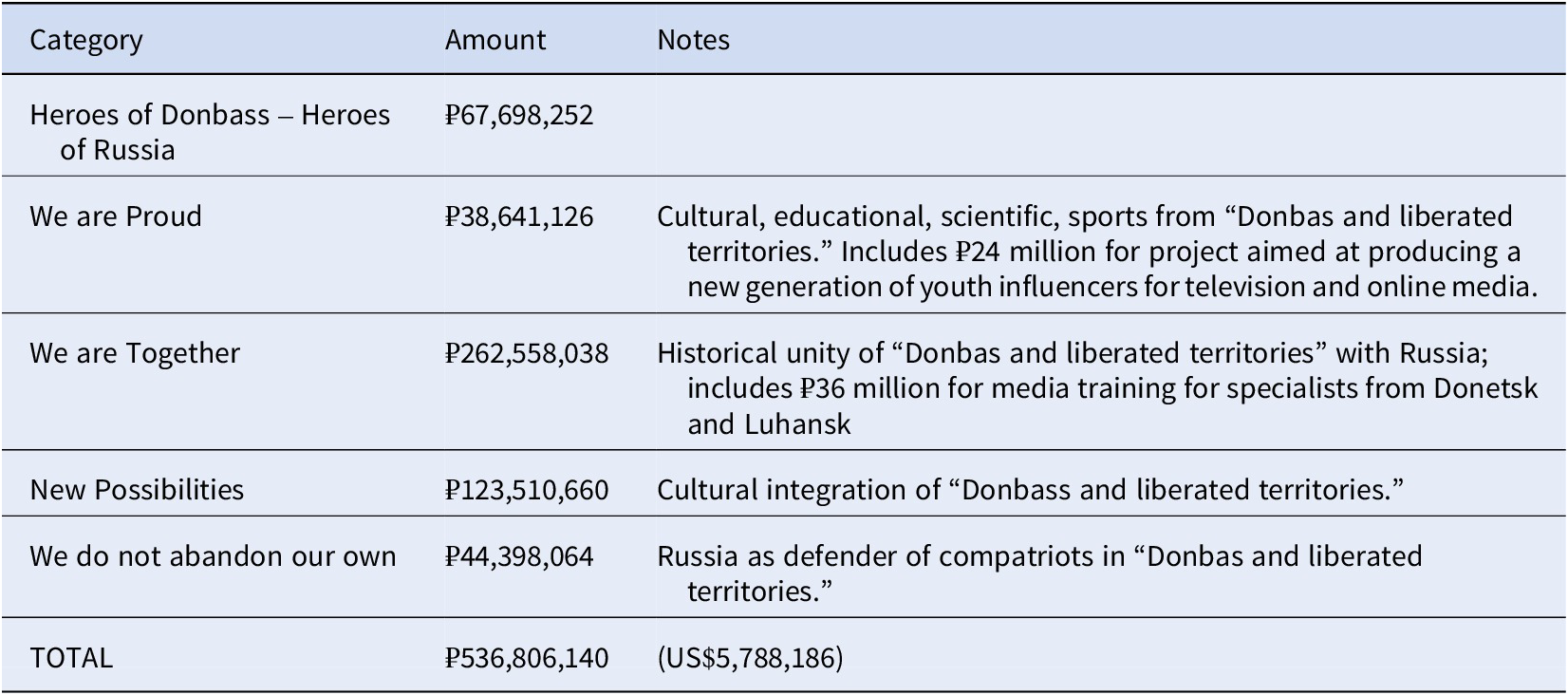

The regime’s need to co-opt everyday nationalist practices in support of imperialist expansion creates opportunities for those with political aspirations in the form of competitive patriotism. As Laruelle and Limonier (Reference Laruelle and Limonier2021) demonstrate, this field of competition extends even to the production of digital and broadcast media. The regime’s stimulation of this kind of competition might be observed in a variety of fields. One such case is the annual competition for grants from the Presidential Foundation for Cultural InitiativesFootnote 5 for projects focused on a variety of themes focused on Ukraine’s occupied territories (see Table 1), including: “Heroes of Donbass – Heroes of Russia”; “We are Proud” (promoting cultural, educational, scientific, and sports projects from Donbas and “liberated” territories); “We are Together” (promoting the claim of historical unity of Donbas and “liberated” territories and Russia); “New Possibilities” (promoting the cultural integration of Donbas and “liberated” territories and Russia); and “We do not abandon our own” (promoting Russia as defender of compatriots in Donbas and “liberated” territories). The total amount funded for these projects exceeds ₽536 million (US$5.8 million) — not counting contributions from non-governmental partners — with the largest projects allocating ₽24 million for producing a new generation of youth influences for television and online media and ₽36 million for media training for specialists from Donetsk and Luhansk. Perhaps more important than the funding amounts are the dozens of failed applicants from across Russia. These instances of “patriotism without patriots” (Goode Reference Goode2020b) enable the Kremlin’s monopolization of national expression in the pursuit of patronage.

Table 1. Presidential Grants Related to “New Regions”

Source: Presidential Foundation for Cultural Initiatives (https://фондкультурныхинициатив.рф/)

For Russia’s citizens, the Kremlin pursued a dual strategy: first, it sought to banalize the war by portraying the conditions surrounding it as the new normal, and second, it appropriated everyday nationalist demands for returns to normalcy by substituting the occupation (portrayed as their “return” to Russia) of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk.

Normalizing the War on Russian TV

Russia’s media is an important source of legitimation for the Kremlin. Russia’s media environment is somewhat anachronistic insofar as broadcast media and especially television remains the primary source of news for the majority of viewers (Volkov et al. Reference Volkov, Goncharov, Paramonova and Leven2021). While there is some separation among age groups, this is surprisingly the case even for a plurality of Russia’s youth despite the rising dependence on social networking since the pandemic. Unlike most countries, Russia’s media is hierarchically organized, and broadcast media tends to drive social media content rather than the reverse (Cottiero et al. Reference Cottiero, Kucharski, Olimpieva and Orttung2015; Kazun and Kazun Reference Kazun and Kazun2019). State control of broadcast media extends even to provincial and local media. In turn, provincial and local state actors distribute and stream broadcast news online while actively co-opting emerging independent news groups on Russian social media (Litvinenko and Nigmatullina Reference Litvinenko and Nigmatullina2020). This ordering of Russia’s domestic media environment is a relatively recent development, and it represents an acknowledgement that the international flow of online media poses a challenge to the Kremlin (Oates Reference Oates2016). In domestic media, this translates into a division of labor in which social media is used for selectively mobilizing different types of regime supporters, while broadcast media is an essential component of the regime’s strategy for keeping the general public demobilized (Alyukov, Kunilovskaya, and Semenov Reference Alyukov, Kunilovskaya and Semenov2022).

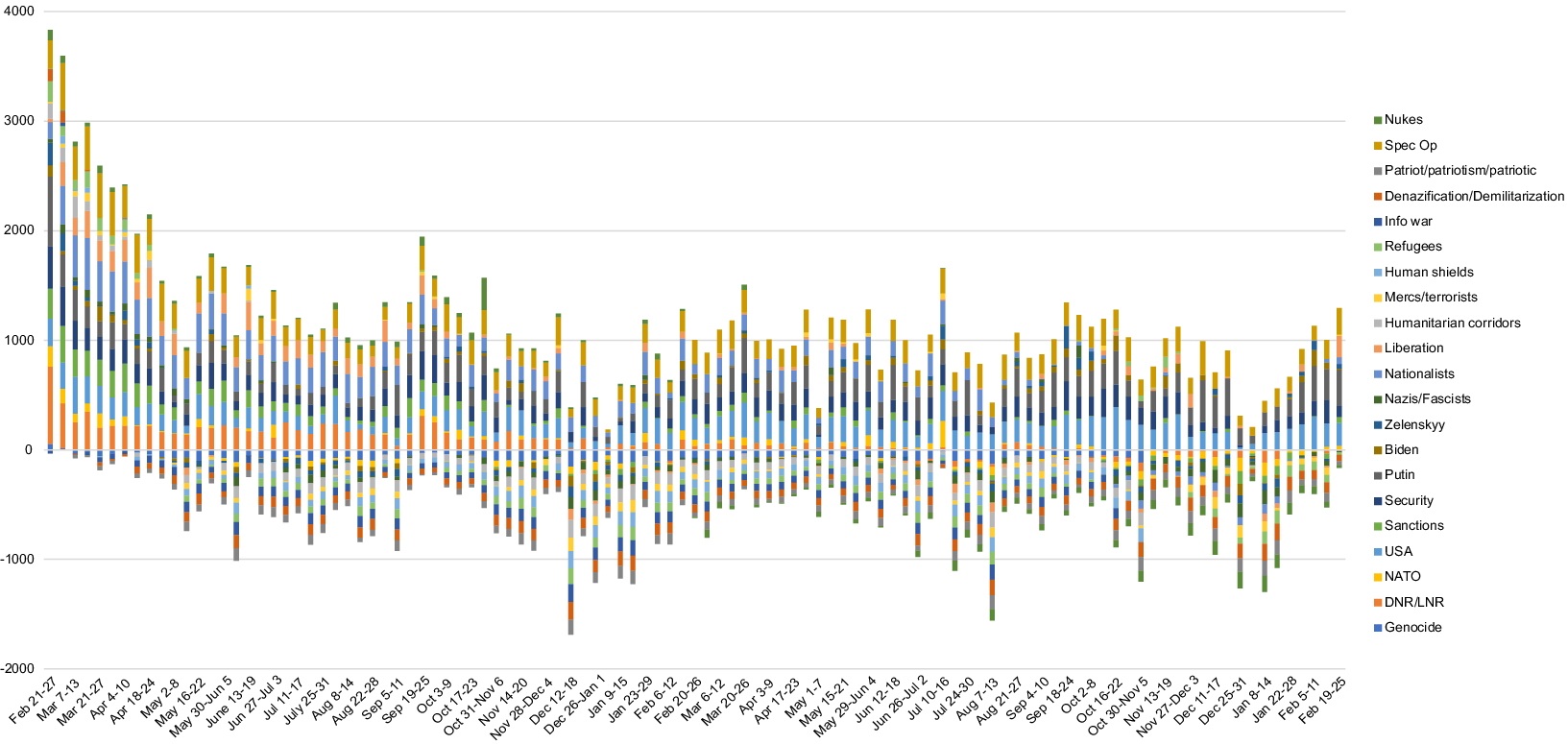

To assess the representation of war narratives on Russian television, this article uses data produced by Russian Media Observation and Reporting (RuMOR), which has tracked mentions of war narratives on four national television channels since the start of the war. These mentions are calibrated relative to mentions of the weather as a measure of their salience for viewers: narratives that are mentioned more often than the weather are more likely to be noticed in daily life and are considered salient, while narratives mentioned less often than the weather are not salient. Figure 1 presents the full range of narrative mentions through the first two years of war.

Figure 1. Topic Mentions on Russian TV (vs the weather), Feb 21, 2022-Feb 25, 2024

Source: Russian Media Observation and Reporting (RuMOR)

From the start of the full-scale invasion through the end of 2022, the war steadily faded into the background on Russian television. After presenting viewers with a dizzying array of war narratives at the start of the full-scale invasion, these narrowed through October 2022 until settling on a small range of salient clusters comprising mainly Russia’s enemies (primarily depicted as the Ukrainian nationalists and the USA), their Russophobic or hegemonic motivations, and legitimation of Russia’s invasion through patriotic and humanitarian appeals. While the Special Military Operation was mentioned constantly throughout this period, it is notable that official justifications for the Special Military Operation in Ukraine, such as preventing genocide in the Donbas or Putin’s proclaimed goal of “de-Nazifying” and de-militarizing Ukraine, ceased to be salient after just the first two weeks of the war. Even these sparing mentions of the war were further suppressed when Russia’s fortunes in war diminished until domestic media could produce counternarratives.Footnote 6

It has been argued that Russia’s domestic media provides a window into the ways the regime seeks to shape public opinion, as media framing shifts as the regime adapts to changing political circumstances (Lankina and Watanabe Reference Lankina and Watanabe2017). While these shifts in framing tend to occur in relation to fast-moving events — as observed in the first weeks following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine — the range of narrative clusters narrows by the fall of 2022 to the stable narratives previously promoted by Russia’s media since 2014: that Russia is a resurgent great nation; the West and NATO are out to destroy Russia; that Russia protects Russians no matter where they live; and that Western democracy is corrupt and failing. With specific regard to Ukraine, additional stable narratives include claims of the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians and that the West is exploiting Ukraine to divide it from Russia and to use it as a puppet state for NATO (Oates Reference Oates2023).

These elements of narrative continuity are important to understanding Russia’s media strategy of normalizing the war: rather than acknowledging the invasion as a rupture, it is presented as a logical continuation of the steady deterioration of relations with Ukraine and the West since 2014. By extension, Russian television diminishes the exceptionality of the pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression. Rather, unsettled times are presented as the product of Euromaidan and the West’s ambitions in Ukraine, with Russia and Russians stepping into the roles of both victim and defender.

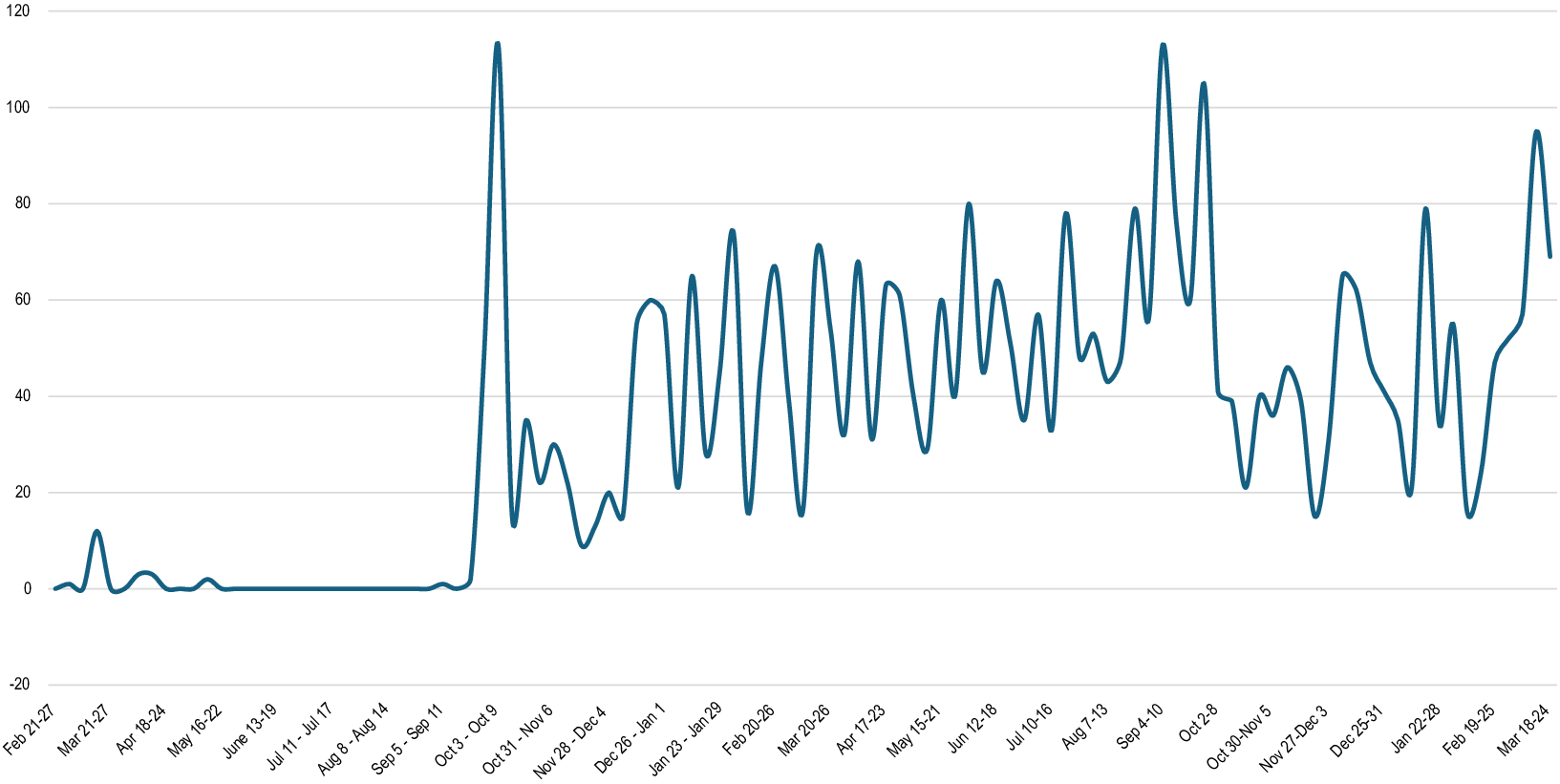

In the absence of an antebellum normality, the territories Russia (partially) occupied in Ukraine—Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, as well as Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts — became the focus for narratives justifying their occupation (“return”) under the rubric of novye regiony [new regions]. Previously, the term was used to refer to Crimea and Sevastopol following their annexation in 2014 and only reappeared during commemorations of that date. With the formal annexation ceremonies for the occupied territories on September 30, 2022, the new “new regions” instantly became a fixation of Russian television (see Figure 2). Interestingly, the reappearance of “new regions” as a category of discourse also occasioned a revival of the neo-imperial term “Novorossiia” to distinguish Kherson and Zaporizhzhia from the Donbas regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. “Novorossiia” was a term used in the Tsarist era to refer to territories that today comprise portions of Eastern and Southern Ukraine. The term was revived by Putin in connection with the attempted “Russian Spring” uprisings in 2014–2015 but quickly fell out of favor after the uprisings failed to spread beyond the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2016; Suslov Reference Suslov2017) The term’s reappearance also serves to portray the current war as a continuation of the period since 2014.

Figure 2. Mentions of “New Regions” on Russian TV, Feb 21, 2022-Mar 24, 2024

Source: Russian Media Observation and Reporting (RuMOR)

“New Regions” and The New Normal

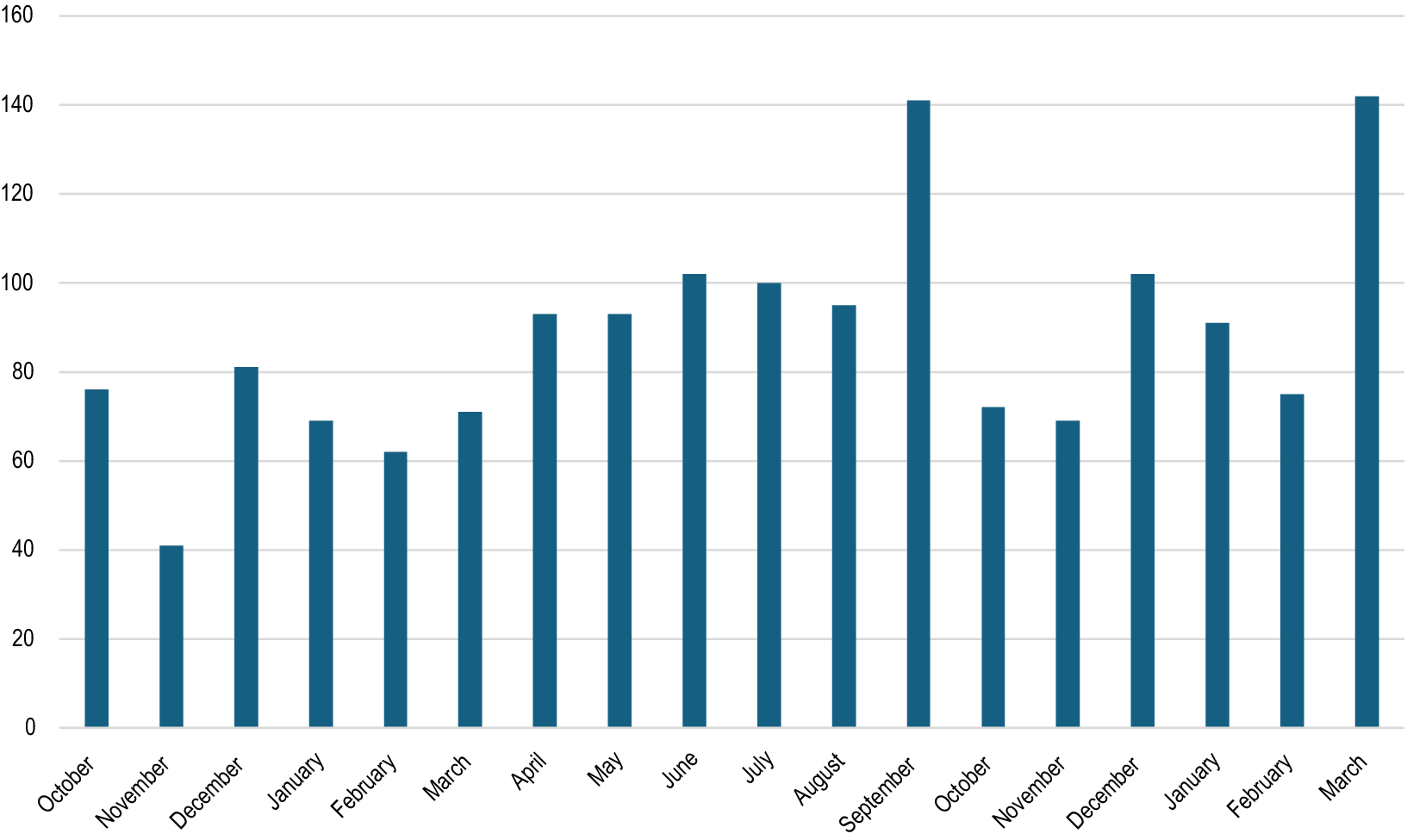

To examine the presentation of the “new regions” and the practices associated with them, this article draws from a corpus of 1,575 reports from broadcast transcripts of the state-run Pervyi Kanal [First Channel] mentioning the “new regions” from October 2022 through March 2024 (see Figure 3).Footnote 7 These reports were auto-coded in MaxQDA at the sentence level, followed by manual inspection to remove spurious matches (for example, removing mentions of Boris Nadezhdin from searches for nadezhda [hope]).Footnote 8

Figure 3. Mentions of “New Regions” on Pervyi Kanal, Oct 2022-Mar 2024

Source: Russian Media Observation and Reporting (RuMOR)

The reports were coded for official and everyday practices and propaganda terms (“Z-terms”) used in reference to the war (that is, Nazis, nationalists, fascists, terrorists, Collective West, Russophobia, etc.). Official practices are considered those undertaken by the state that connect the “new regions” with the nation in some fashion. Everyday practices are those that are claimed to be undertaken by ordinary Russians in their daily lives, either by attribution or interview with residents. The range of official and everyday practices was determined deductively in accordance with previous research on official and everyday patriotism in Russia (Goode Reference Goode2016; Reference Goode2021a). Word frequency lists were further used to identify additional practices for consideration.Footnote 9 Finally, the reports were coded for mentions of emotions attributed to or expressed by residents of the “new regions.” The codebook is provided in the article’s annex.

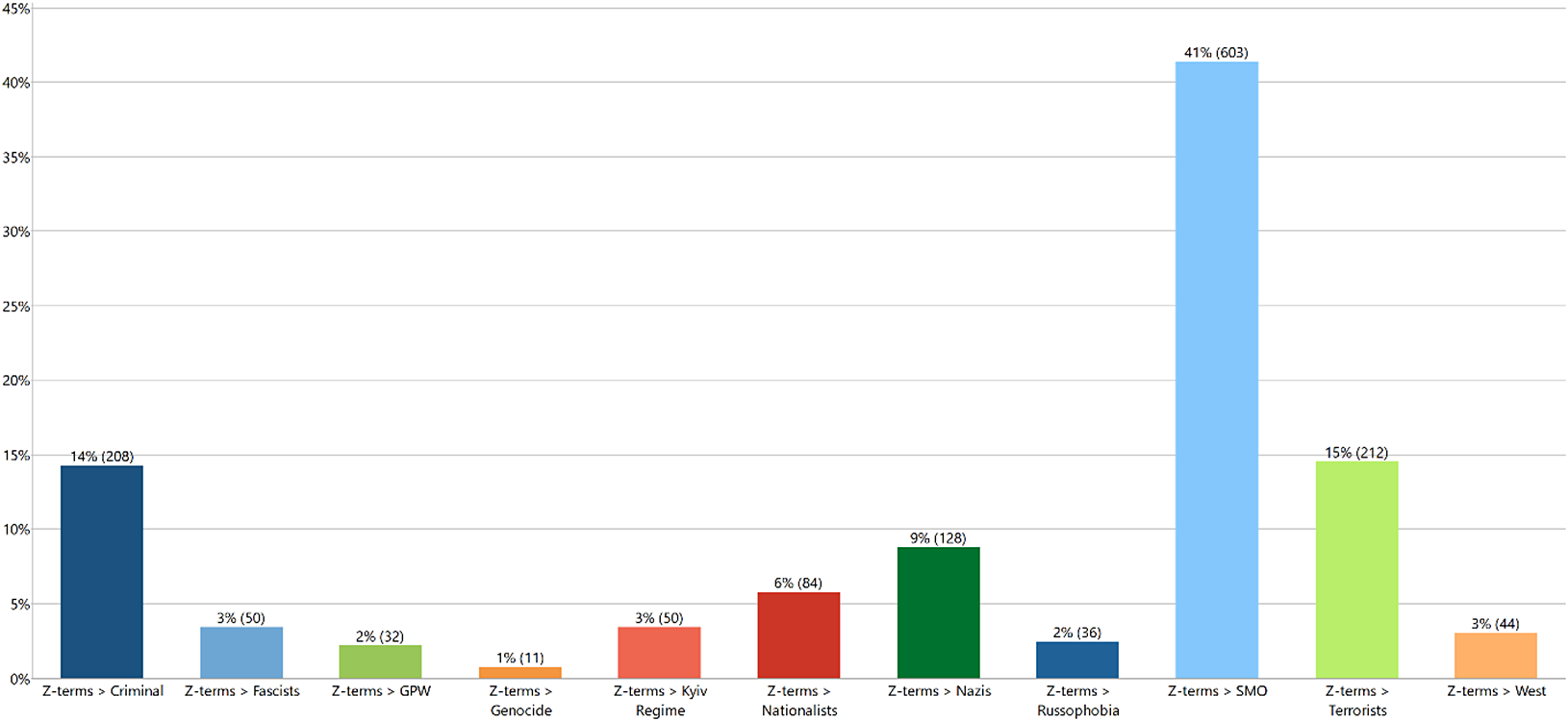

If we first examine the distribution of “Z-terms” in reports mentioning the new regions, there is obvious continuity with the broader strategy of normalizing the war (see Figure 4). As was the case with national television broadcasts generally since the start of the war, there are relatively few mentions of the war in Ukraine aside from a constant flagging of the Special Military Operation. Also consistent with the broader normalization of the war are the more numerous mentions of Russia’s enemies (criminals, terrorists, Nazis/fascists, nationalists). The diminished mention of the West is somewhat surprising, though this is consistent with the notion that Russia seeks to keep mentions of the war in the background. There may also be a need to avoid the impression that Russian territory is threatened by the West.Footnote 10 Indeed, the RuMOR project documented a similar tendency in the summer of 2023 when Russian partisan forces attacked the town of Shebekino in Belgorod oblast (along Ukraine’s border): Russian television outright denied the presence of enemy forces on Russian territory and the government even handed out medals for the successful defense of the region.Footnote 11

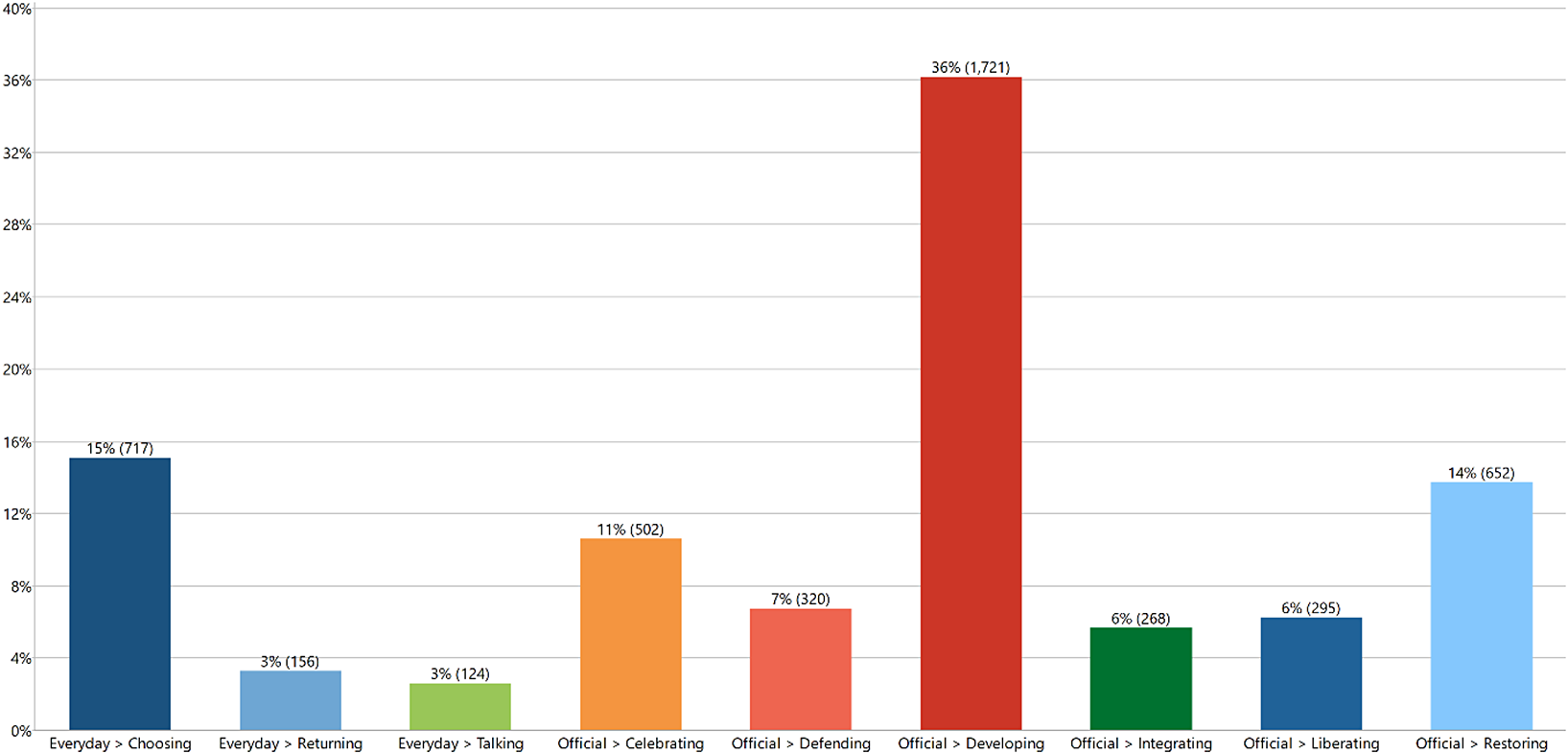

Figure 4. “Z-Terms” in reports mentioning New Regions (Coded Segments)

The distribution of official and everyday practices further evidences the separation of the war from mentions of the “new regions” (see Figure 5). Official practices emphasize developing infrastructure (including schools, roads, and police stations) in the occupied territories. As one might expect, the source of destruction is never attributed to Russia. Related to developing is integrating the infrastructure, bureaucracy, and budgets of the “new regions” into Russia’s national structures. Restoring is used to refer explicitly to peace, childhood, and other aspects associated with normal life. The implication is that normality was interrupted by the Ukraine and the West, while restoration is conferred by way of the regions’ “returning” to Russia. These themes of developing, integrating, and restoring further conform with the civilizing mission that is bound up with Russia’s neo-imperialist motives.Footnote 12 As Kassymbekova and Marat (Reference Kassymbekova and Marat2022) describe, “Russian rule over non-Russian populations is not colonialism but a gift of modernity. It is a deeply altruistic act for the sake of backward people.” The discourse of restoring and returning further echoes the treatment of Crimea as “returning” to Russia in 2014 and extends the perception of the present war as continuous with the period since 2014. However, the occupied regions were not part of Russia after 1991, nor were they part of the Soviet-era RSFSR. By way of this sleight of hand, “returning” to normality is not just about changing governments but also rejecting the legitimacy of Ukraine’s independence — which, of course, has been a constant refrain of Putin’s.

Figure 5. Official and Everyday Practices (Coded Segments)

Celebrating the nation is also significant in inscribing the “new regions” in the observation of Russia’s national holidays and commemorations. In this instance, however, they are usually mentioned in passing, often in the form of celebrations observed “in the new regions, as well” (“v tom chisle i v novykh regionakh…”). In this fashion, viewers are reminded that the “new regions” are joined to the nation through their (newly) shared observances of national holidays. At the same time, the nation is compelled to celebrate the “new regions” through a new holiday, Den’ vossoedineniia novykh regionov s Rossiei [Day of Reunion of the New Regions with Russia] on September 30th, created in 2023 to mark the anniversary of the annexations. The new holiday again emulates Crimea’s annexation, which is observed with the holiday, Den’ vossoedineniia Kryma s Rossiei [Day of Reunion of Crimea with Russia] on March 18.

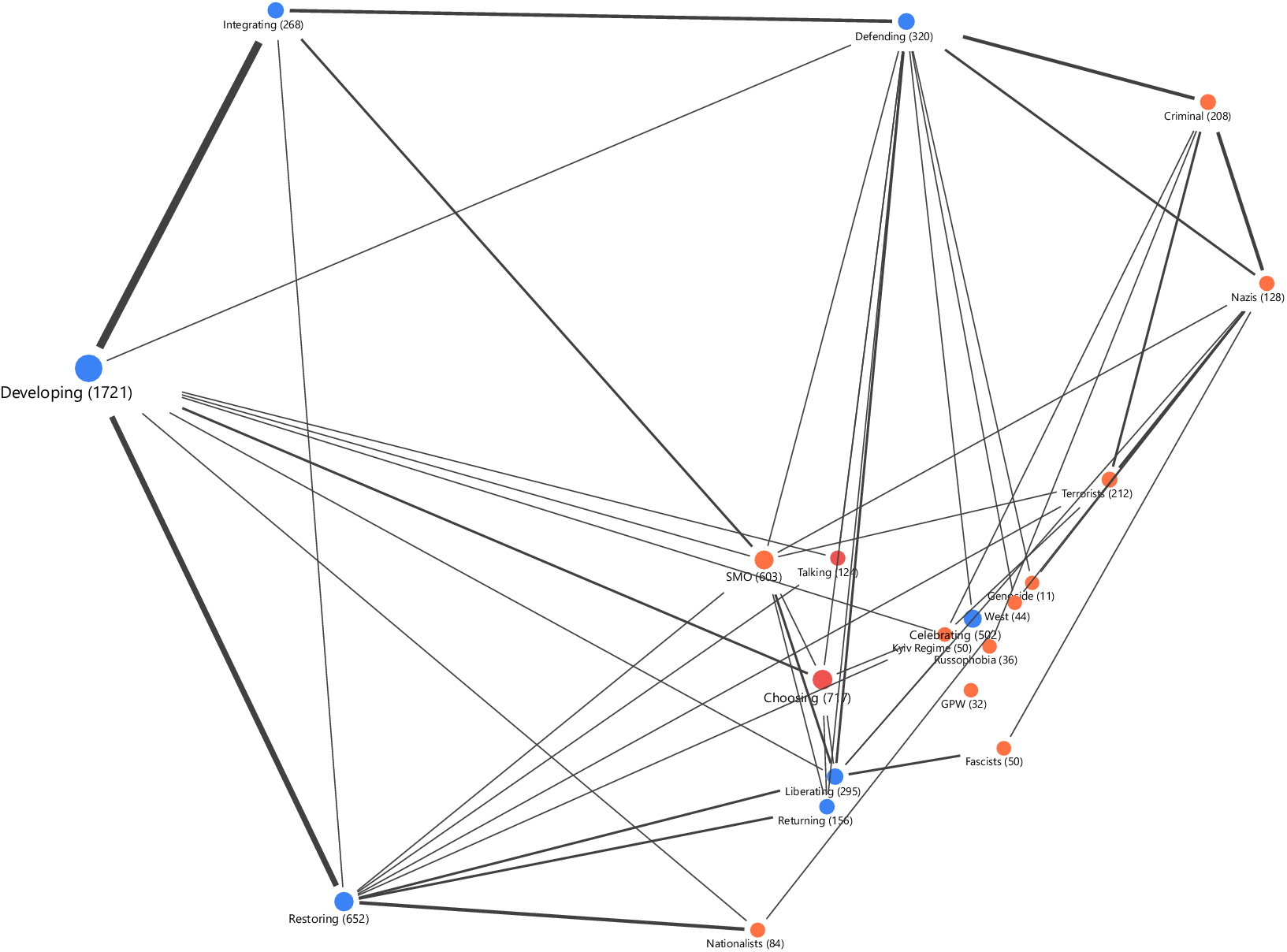

Official practices are thus kept distant from mentions of the ongoing war — a tendency consistent with the broader normalization of war on Russian television. Figure 6 illustrates how often coded segments intersect with other codes in the broadcast transcripts. The discourse of developing and rebuilding the “new regions” is kept well to the side, intersecting mainly with integrating and restoring. In other words, banal nationalism is boring (and normal). By contrast, the Z-terms cluster around official practices of celebrating and liberating (unsurprisingly), as well as everyday practices of returning and choosing.

Figure 6. Code Map of Practices and Z-Terms (Intersecting Codes)

While official practices are kept carefully apart from mentions of the war, everyday practices do the heavy lifting with residents’ voices, and their depictions are used to confirm the Kremlin’s war narratives about Ukraine and the West. Choosing the nation is the most prominent of everyday practices, though the bulk of mentions emerge in February–March 2024 in relation to Russia’s presidential election (see below). Returning is perhaps the most important of these because it legitimates the official practices of developing and restoring and binds the “return” to Russia with returning to normal, everyday life.

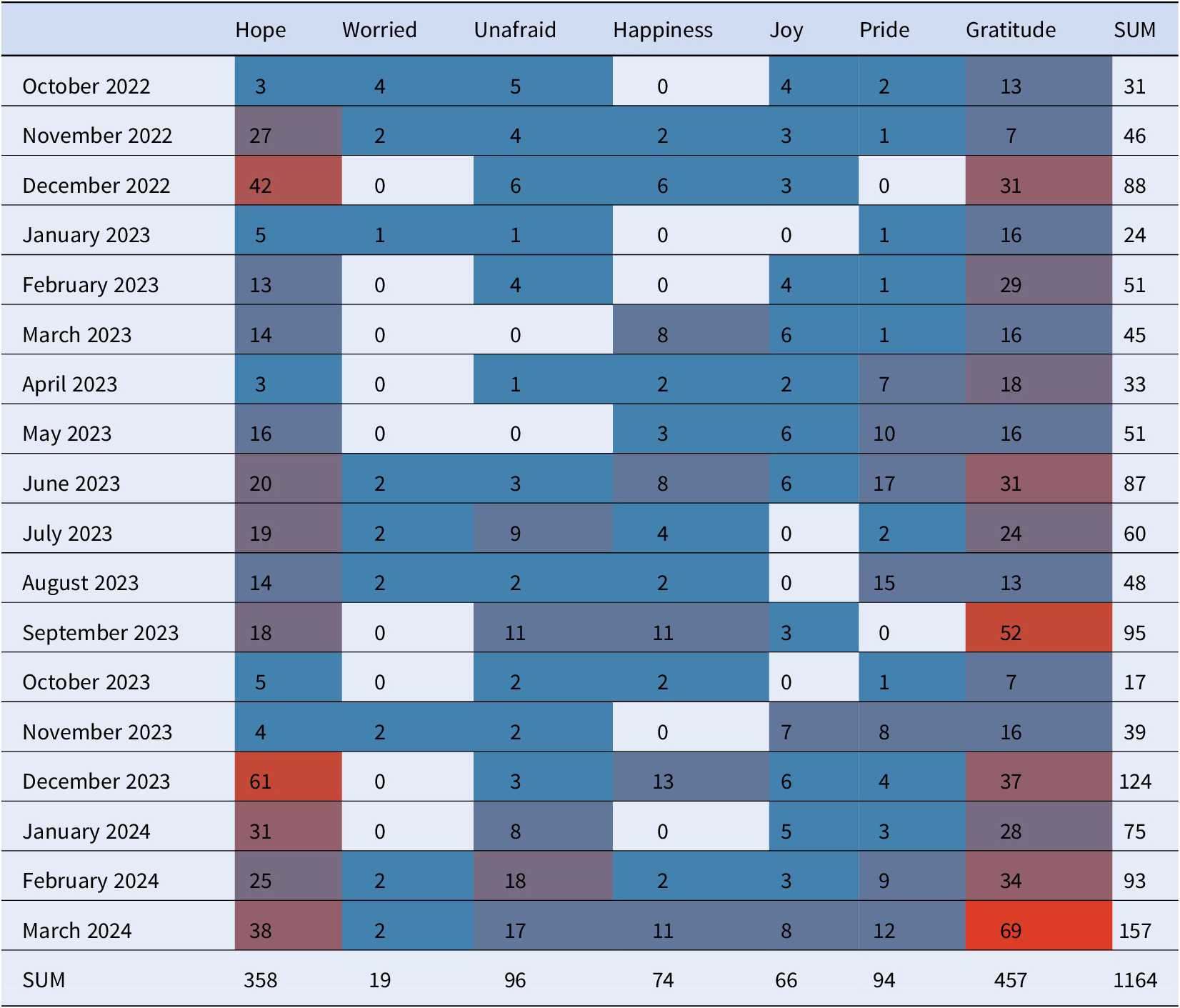

Talking with and about the nation is also significant in that residents are the most interviewed category of individuals after Putin, exceeding mentions of regional governors, members of Putin’s government, and even soldiers. Just as important, residents attach emotional weight to the “new regions” return to normality (see Table 2). Most prominent among the emotions attributed to residents are hope and gratitude. Gratitude especially surges in mentions around the anniversary of the annexations in September 2023, as well as the presidential election in March 2024. Pride and joy also figure prominently in mentions of residents’ emotional states, as well as the related observation that residents are unafraid (of war, of threats of violence, of the West). Indeed, there were no mentions of negative emotions in relation to the residents, despite their lives being upended by Russia’s invasion. While there were occasional mentions of the residents as worried, these typically were followed by reassurances. Other times, the correspondent invokes emotion to frame the actions of the West or Ukraine, followed by a resident’s defiant response. For example, in a report that mentioned attacks on residential homes, one resident replies, “It’s concerning, but you know the Donbas character: it won’t stop or scare us.”Footnote 13

Table 2. Emotional Attribution in Reports on “New Regions”

It is also worth mentioning, however, that this depiction is intended for a national audience in Russia. McGlynn (Reference McGlynn2023b) characterizes this nationally targeted messaging on Russian television as “Tier 1 propaganda,” while “Tier 2” propaganda is delivered by local media and specifically targets residents in the occupied territories with a different kind of emotional discourse. This targeted propaganda aims to demoralize residents by sowing doubt about Ukraine’s capacity to defeat Russia, characterizing Ukraine’s army as violent criminals, and spreading fear that they will be punished as collaborators if they try to escape to Ukraine.

Case Study: The “New Regions” in Russia’s Presidential Election

In the run-up to the heavily stage-managed presidential election in March 2024, coverage of the “new regions” mobilized images of both official and everyday practices. Elections in autocracies serve a variety of purposes unrelated to public choice (Gandhi and Lust-Okar Reference Gandhi and Lust-Okar2009). Even in personalist autocracies like Russia, elections are high-profile and high-stakes events that shape the strategies of incumbent regimes and opposition (Smyth Reference Smyth2020). Presidential elections are not so much contentious moments that promise eventful change as they are a means of activating banal repertoires and scripts that legitimize the existing social and political order, inducing competitive patriotism among elites and routinizing popular compliance. In the run-up to the March 2024 election, they provided a unique window into the Kremlin’s strategy of banalizing the occupation of Ukrainian territories that highlighted the utility of co-opted everyday nationalist practices.

First and foremost, the “new regions” were emphasized as being excited by the opportunity to vote for the first time in Russia’s presidential election. As voting began, commentators breathlessly pointed to the enormous turnout in each of the “new regions” relative to the rest of the country (see Figure 7). Since early voting was allowed in the zone of the Special Military Operation, each of the novye regiony appeared to set the pace for all other regions — in turn, legitimating Russia’s claim to the territories for domestic audiences.

Figure 7. Reporting the “New Regions” Voting Enthusiasm

Source: Pervyi Kanal, March 15, 2024.

Voters in the “new regions” were thus presented as moral guiderails for anyone who might be tempted to think about issues or candidates (other than Putin) instead of identity, security, and normality. In the same fashion, voters were depicted celebrating the occasion with over-the-top patriotic displays and (of course) flag-waving (see Figures 8–9). When interviewed, residents stated that they were voting for the greatness of Russia, for Russia’s future, and peace:

WOMAN: Because I love Russia and consider it necessary to elect a head of government who will lead us to new victories and successes.

Figure 8. Reporting the Patriotism of Voters in the “New Regions”

Source: Pervyi Kanal, March 16, 2024.

Figure 9. Reporting the Patriotism of Voters in the “New Regions”

Source: Pervyi Kanal, March 16, 2024.

MAN: I served in the military at the beginning of the SMO and consider it my civic duty, naturally, to be one of the first to vote!

WOMAN 2: so that we can have peace and live peacefully. Things are changing! Thank you, Russia!

WOMAN 3: Because I want a good future for the country [and] stability.

WOMAN 4: Our city is Russia. I’m so happy, so happy, and I’m only sad that my husband didn’t live to see this happy day.Footnote 14

Further connecting the election in the “new regions” with the normal life of the nation, family metaphors were everywhere. Family metaphors further naturalize and legitimize the bond between Russia and the occupied territories for domestic viewers. In an illustrative example (see Figure 10), a family in Luhansk was said to have begun “a new family tradition” of voting together. In this fashion, the depiction of voters in the new regions fused everyday nationalist practices concerning family and daily life with official practices while largely avoiding the Kremlin’s war narratives, creating an image of the ideal voter and lending it emotional weight.

Figure 10. Voting as a Family in the “New Regions”

Source: Pervyi Kanal, March 16, 2024.

Finally, a ragtag group of international observers served to underscore the international significance of Russia’s mission in Ukraine while obliquely confirming its war narratives (see Figure 11). One observer from Italy stated that he came to “bring truth to the West” about Donbas. An observer from France said that he wanted to see the election for himself “because Western media creates an alternate reality.” Another observer from Serbia lavished praise upon Russia as the “only country capable of holding elections during a Special Military Operation.”Footnote 15

Figure 11. International Observers of Voting in the “New Regions”

Source: Pervyi Kanal, March 16, 2024.

Finally, it is worth noting that each of these exemplars from Russia’s televised coverage of the 2024 presidential election in the “new regions” invoked elements of imperial nationalism identified by Pain (Reference Pain, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016) with the everyday patriotic practices of people in Ukraine’s occupied territories: the distinctiveness of the Russian people, the presentation of Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian territory as essentially defensive, and the desirability of the political domination of ethnic Russians. At its core was a heavily stage-managed celebration of Putin’s rule, further exemplifying the sacralization of political power at the core of Russian neo-imperialism (Zaporozhchenko Reference Zaporozhchenko2024).

Conclusion

This article has sought to demonstrate how autocracies manage nationalism in unsettled times by examining the depiction of Ukraine’s occupied territories on Russian television as “new regions.” In settled times, the production of banal nationalism in autocracies is distinguished by regime efforts to monopolize national expression (Goode Reference Goode2021a). Monopolizing the nation succeeds to the extent that citizens cease to care about the regime’s routine imposition of national symbols and expressions — in other words, when it becomes a pervasively unnoticed facet of daily life. In unsettled times, the banal potentially becomes volatile as everyday nationalism manifests in demands for a return to normality, whether meaning the status quo ante or simply an idealized version of the nation’s normal state of existence. In Russia, there is no plausible way for Putin’s regime to return to an antebellum normality. Instead, Russia has pursued a strategy of normalizing the war in daily life and connecting it with the post-2014 period — in a sense, redefining the prewar normality as if it was an extension of the current unsettled times. Interestingly, one might look to Russia’s foreign-focused propaganda that targets Russophone populations as early attempts to elaborate this strategy. Portraying normal life in Russia’s neighbors as a dreary experience in failing states has been a staple of Russia’s propaganda. Russophone consumers of Russia’s propaganda were also found to have become bored with the conflict in Ukraine by 2017–2019, in turn contributing to the normalization of the conflict as a routine news topic in their own countries (Vihalemm and Juzefovičs Reference Vihalemm and Juzefovičs2023).

In place of an antebellum normality, the Kremlin substitutes depictions of the occupied territories’ “return” to Russia. The role of the “new regions” in this strategy is to facilitate the ongoing monopolization of national expression while confirming the domestic political order. Television focuses on the mundane official tasks of rebuilding the “new regions” and integrating them into the nation — seeking to make the nation a banal reality throughout the occupied regions and, in doing so, providing an illustration of the new normal in the midst of unsettled times. At the same time, everyday practices and residents’ voices are presented in such a way as to confirm the Kremlin’s war narratives and grant them emotional weight.

The success of this strategy is difficult to assess in the absence of reliable ways to discern public opinion in Russia. Russia’s media aims not just to normalize occupation but also to build public silences around the consequences of imperial aggression: mass murder, mass abduction of children, destruction of Ukrainian cultural monuments and institutions, urbicide and ecocide, systematic use of torture, and (re-)imposition of settler colonial rule in the occupied territories. In this regard, comparison with Russia’s prior experience with demolishing Chechnya and reinstituting colonial rule may prove instructive of the durability and appeal of neo-imperial framing.Footnote 16

Future research might further focus on elite competition as one potential means of gauging the effectiveness of normalization strategies in perpetuating autocratic rule. The monopolization of national expression in autocracies turns nationalism into a means of signaling loyalty to autocratic regimes as well as a field for competition among regime subordinates as they attempt to divine the rulers’ preferences and to gain access to new sources of patronage (Goode, Reference Goode2012; Goode, Reference Goode2020b). National broadcast media arguably plays a crucial role in communicating the regime’s boundaries of expression, as well as enabling political entrepreneurs to innovate or simply to mimic the regime’s repertoires.

Finally, there is substantial comparative research on the uses and effectiveness of media in autocracies. While nationalism studies have lately focused on social media and social networking as a window into the substance and distribution of nationalist sentiment, the study of broadcast media remains important for nationalism studies (Skey Reference Skey2022) — especially for accounting for nationalism’s reach and its relationship to elite competition. This relationship is especially important for understanding the connections between regime type and the production of nationalism at the intersection of official and everyday nationalism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2025.28.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Adam Lenton, David Stroup, Hyerin Seo, the participants in the annual conferences of the George Washington University Russia Program, and the Association for the Study of Nationalities, as well as two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback. Any mistakes or omissions are the author’s sole responsibility.

Financial support

Support for the preparation of the data in this manuscript for publication was provided by an SSHRC Connection Grant.

Disclosure

None.