Introduction

Homo sapiens as homo geographicus (an entity active in the geographical environment, in space) is a blend of homo categoricus (an entity that categorises, divides) and homo nominans (an entity that assigns names) (Solarz Reference Solarz and Solarz2018, 54). On one hand, it is natural for it to create divisions (segregate other people, things, phenomena, space, etc.); and on the other hand, to label the discerned fragments of reality. A world divided and named is a world that is familiar, tamed and friendly.

The purpose of this article is to define the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans. Designating these borders is a difficult task due to historical (tenuous source base), geographical (the lack of previous research of this type as well as of explicit and unique delimiting criteria), social (the lack of past and present subjective sense of identity in an objectively existing cultural group) and political reasons (the burden of difficult Polish-German relations during the period from the end of the 19th century). At the same time, however, the presented geographical problem concerns a densely populated region that has retained settlement continuity since the Middle Ages. Resolving it is crucial in the context of research into its past and present, and potentially also for the identity of the people who live there, especially since they can be hypothetically identified with Forest Germans. It is important in the context of possible (self-)discovery of their historical and simultaneously (paradoxically) new identity as Forest Germans, which was obscured and misrepresented for political and ideological reasons approximately 100 years ago [with new ethnographic groups being invented in their place during the interwar period (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 114)]. Defining the settlement region of Forest Germans is one of the first steps towards learning about them. On one hand, the presented analysis is a detailed case study of the forgotten community of Forest Germans; on the other hand, it illustrates broader phenomena that affect multiple cultural groups of the borderlands, which have complex identities, in a situation of a conflict between their communities of origin (in this case – Poles and Germans).

The process of final demarcation of the settlement region of Forest Germans will be subject to numerous criteria, including those pertaining to various relics of their material and non-material culture. However, the key issue in the Polish historical, cultural and geographical context is the non-specificity of potential markers that would allow for the area inhabited by them to be designated. The ubiquity of anthroponyms and toponyms of German origin in Poland, the geographical distribution of chain villages, so-called linear forest villages (in German Waldhufendorf), the long-term influence of the German language on the Polish language, etc. mean that it is likely impossible to distinguish the settlement region of Forest Germans from the remaining territory of Poland based solely on these criteria. The specificity of 1,000-year-old Polish-German relations (from the 10th to the 21st century), reflected in thorough intermingling of Polish and German elements throughout the territory of Poland over those 10 centuries, means that the first step must consist in verification of the possible location and borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans through reference to narrative historical sources that mention them in geographical context. Only then will it make sense to use other criteria in the Polish-German historical, geographical and cultural context. The focus of this article is therefore the first step in the process of defining the settlement region of Forest Germans, which is affected by quantitative and qualitative imperfections of the sources as well as subjectivity of the researchers tackling this academic challenge.

Theoretical and practical lessons from the Forest German study

The Forest Germans make for an intriguing study for several reasons. For one, they can provide new knowledge about a community that had never been the subject of scholarly research until the eve of the 2020s. This alone is an exciting prospect for the researcher, although the situation is more complex in practice. Even though scholars were interested in the people who lived in the Forest German settlement area, they did not perceive them as Forest Germans and did not study them in the context of the genesis and history of this settlement. As a result, they often, sometimes wilfully, disregarded or ignored certain historical facts and processes, and even fabricated social facts (as mentioned above, e.g. Polish ethnographers ‘invented’ new ethnographic groups and identities (Pogórzanie and Rzeszowiacy) to replace them in 1918–1939) (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 114). The researcher of Forest Germans thus becomes something of an archaeologist who has to unearth the distorted social reality buried beneath several layers of narrative. At this point, Forest Germans immediately invite deeper reflection on scientific cognition from two perspectives. On the one hand, they encourage reflection on its limitations and challenges. On the other, they serve as a warning to every researcher, as their case clearly illustrates the pitfalls of not keeping current policies and ideological considerations out of science.

Geographic considerations, i.e. identifying the region of interest and demarcating its boundaries, has to be the starting point for Forest German research. This determines or locates historical sources, interviews, or surveys to be investigated or performed respectively. Faced with a millennium of relations between neighbouring Poles and Germans, along with the complete polonisation of the Forest Germans, delimitating Forest Germany should assist in filtering out those traces exclusively associated with the Forest Germans from the many traces of German culture in the culture of Poland and the Polish Carpathians. The 700-year history of the Forest Germans and their complete polonisation bears out Michel Houellebecq’s claim that the map is more interesting than the territory (Houellebecq Reference Houellebecq2010). This is especially so as Forest Germany has yet to be delimited. This is a major hurdle in any study of this cultural and territorial community.

Forest German research comes under research on one of the most important historical processes that took place in the borderland of Latin Western and Orthodox Eastern Europe, viz. the eastern colonisation of the 13th and 14th centuries. In 1934, the French historian Marc Bloch wrote ‘The German expansion is not only a major event of European history in its own right. It places one of the most exciting experiences that researchers of human societies can dream of right before our eyes: the contact and reciprocal reactions between two types of civilisation’ (Higounet Reference Higounet2003, 19). The eastern colonisation consisted of German colonisation and the imposition of German law. These two strands proceeded in parallel and overlapped in certain places (Higounet Reference Higounet2003; Piskorski Reference Piskorski2001). One of the last and easternmost phases of this process was the colonisation of Forest Germany. This mediaeval eastern colonisation was pivotal to shaping the cultural landscape, as well as the national and international relations, of this part of Europe. It built an ethnic and political map of the region that prevailed until 1945, and a model of the landscape that is still current (Piskorski Reference Piskorski2001; Piskorski Reference Piskorski2005; Piskorski Reference Piskorski2006; Zaborski Reference Zaborski1926). One of the results of this was that the mediaeval (12th-14th century) ethnic boundary between Poles and Ruthenians, and by extension Western civilisation, probably moved 20–40 km eastward in the Polish Carpathian Foothills and the Jasło and Krosno Basins to the 17th century (Parczewski Reference Parczewski1991, 66). For this reason, Forest German research also comes under research on Central Europe as a distinct geographical unit (Škrabec Reference Škrabec2013) and on the east-west divide in Europe (Davies Reference Davies1998; Solarz Reference Solarz2022; Wolff Reference Wolff2020). The eastern border of Forest Germany is one of their possible eastern borders.

Forest German research lays bare the limitations of traditional methods of scientific cognition, especially when it comes to historical, linguistic, and landscape analysis. The key three research issues concerning the ethnogenesis of the Forest Germans are: (i) their source area(s) and the stages of their migration to Forest Germany; (ii) their original ethnic composition and their subsequent intermingling and assimilation with the Polish population; and (iii) their relations with other ethnic groups in the Carpathians. In his analysis of Romania, Lucian Boia noted that a populace is not something given once and for all, but a fluid synthesis that is in any event cultural and not biological (Boia Reference Boia2016, 53). The Forest Germans are obviously a fluid cultural synthesis, but as well biological. First, due to the paucity of sources, traditional research methodologies listed above cannot answer the three questions posed above. This has prompted the use of new research techniques, especially genetics. Geographical research has become all the more important given that delimitating Forest Germany has to be the first step in any genetic study, as it helps determine where the descendants of the original colonists, i.e. the study’s potential participants, are most likely to be found.

As indicated above, Forest Germans are also a fluid cultural synthesis. ‘The problems of colonisation, assimilation, and acculturation can only be identical from a current perspective. They should be separated, as the bare colonization of a territory usually lasted only a few decades, whereas assimilation and acculturation spanned several centuries and many generations, and the result only depended on an influx of colonists to a relatively minor extent. It more often depended on the territory’s subsequent political and cultural history.’ (Piskorski Reference Piskorski2006, 216). Forest Germany was colonised for no more than half a century and the process ceased around the turn of the 15th century. The western part was polonised in the 16th century, and the rest of it at the latest by the turn of the 19th century. Basing on Barbara Loyer’s observations on minorities (in fact a minority is any cultural and territorial group that maintains a distinctiveness from the society within which it operates), it should be noted that a separate cultural-territorial group is a community that: (i) by itself, objectively stands out from the rest of the population; (ii) considers itself distinct from the rest of society; and (iii) is perceived as such by the majority (Loyer Reference Loyer2011, 19). These three distinctiveness ‘indicators’ form a matrix of types of cultural-territorial groups, from actual outright minorities to exogenously invented minorities, with numerous intermediate types. Indicators (i) and (ii) do not apply to the Forest Germans. Centuries of assimilation and adaptation have blurred or diluted all conspicuous markers of distinctiveness (the clearest traces are preserved in toponymy and anthroponymy). The evolution of a Forest German identity was blocked from the top prior to 1950 and there is currently no such regional identity. In this respect, the situation only changed when the communist system collapsed in 1989, and freedom of scientific research was restored, censorship was lifted, and there was a warming of relations with Germany (i). During the 1990s, there was an increase in interest in microhistory, including genealogy (ii), and the 21st century has seen the rise of the Internet and social media (iii). The third indicator of distinctiveness (external perception), however, definitely applied to the Forest Germans until the mid-20th century which is at least indicated by the ethnonym and choronym created to name them and their territory. The specifics of the third indicator, however, consist in its effective removal from academic and popular discourse. This is because Polish historiography, geography and ethnography in the 19th and 20th centuries came to be contingent on the political and national needs of a nation without a state (1795–1918), immersed in conflict with Prussia (no later than 1772) and Germany (since 1870), and then a state threatened by German revisionism (1918–1970/1990) (Kroh and Dobroch Reference Kroh and Dobroch2024, 57; Górny Reference Górny2024, 255; Romer Reference Romer1939, 5-7). Nevertheless, Louis Wirth noted that the minority is not a statistical concept, but is characterized by a common experience of discrimination and stigmatisation, e.g. on account of their actual or purported background (Ndiaye Reference Ndiaye2011, 16). Objectively, this has also been the experience of Forest Germans and also indicates their certain distinctiveness as a cultural-territorial group in Polish society.

The partial maps and the summary map, which are the central and final result of the research presented in this article, have a specific character. As there are no old or historical maps depicting Forest Germany, there are no delineated borderlines that the geographer can critically analyse and superimpose on the contemporary map of the relevant part of Poland. Whatever map is used, it cannot be the result of field research, because Forest Germany has never been a distinct settlement unit with boundaries marked on the ground. As there is no Forest German identity, the area cannot be plotted on the basis of the mental maps of community members: If they do not define themselves as Forest Germans, then ipso facto they do not define their area. The only source for locating Forest Germany and reconstructing its boundaries are historical narratives. These in this case, however, are devoid of geographical precision. They have to be ‘translated’ into the language of geography that is a map. This involves a multi-stage spatial interpretation and concretisation of the geographical descriptions they contain. As a map is not only a collection of information but also the result of an interpretation of the world (Soini Reference Soini2001), the partial maps and the final map presented in this study thus become imaginary maps of a sort. This is because they not only allow for the presentation of Forest Germany as a fragment of the real world, which objectively exists, but also reflect its image in the imaginations of those who compiled documents about this region – in the imagination of the creator of a narrative historical source, the geographer who interpreted it spatially, and the cartographer who plotted them on the basis of the geographer’s instructions.

Forest Germans - complex and changing identities

The Polish term Głuchoniemcy is perfectly ambiguous as this single word simultaneously points to the genesis of this community (colonists clearing out the forest on the borders of the Latin world to make room for new villages) and to its characteristics (distinctness from the Polish and German populations, which gave rise to problems in communication). In other languages, such as German and English, the Polish term Głuchoniemcy (probably coined before the German one) and its double meaning must be conveyed using different words – Walddeutsche/Forest Germans and Taubdeutsche/Deaf Germans, respectively (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 122-123). While this term already emerged as an ethnonym in the second half of the 17th century (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 115-116), the first person to have used it in a form that suggested a choronym might have been Wincenty Pol in 1869 (Pol Reference Pol1869, 32). However, both uses were eliminated from academic and popular discourse by the mid-20th century during the escalating Polish-German conflict. There is only one known map on which their settlement region is marked; it contains errors is and highly schematic (Niemcówna Reference Niemcówna1923, n.p.). As a result, approximately seven centuries after the settlement initiative which led to the emergence of Forest Germans, we do not know where exactly they lived (and perhaps still live).

The establishment of the Forest German community is connected with political and settlement processes which began in the 1340s on what was at the time the south-east border of Poland. After Red Ruthenia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland, a large-scale colonisation initiative commenced in the former borderland region – in the river basin of Wisłoka and farther east in the river basin of Wisłok. It also relied, to an extent which is nowadays unknown, on settlers from the German cultural circle, likely including both ethnic Germans and partly Germanised Western Slavs from Slavic Germany. Over the following centuries, the first settlers representing (to varying degrees) the German and West Slavic (including Polish) cultural and ethnic circles were polonised as a whole as a result of intermixing with subsequent waves of settlers (typically of Polish origin), thus creating the Polish cultural group of Forest Germans. With respect to the present day, we are certainly not looking for a German population in this area since it is certain that no relic German community with medieval roots currently exists in the river basins of Wisłoka and Wisłok.

Delimitation of the Forest Germans settlement region according to sources: the challenge of source ambiguity and subjectivity of interpretation

In the light of the complex historical, cultural and geographical context of Central Europe, including long-term Polish-German proximity, delimiting the settlement region of Forest Germans requires its outline to be defined based on analysis of sources.

The research procedure aimed at demarcation of the settlement region of Forest Germans consisted of several stages and ultimately produced maps depicting the issue under consideration. The first step involved a query aimed at finding as many mentions placing Forest Germans in geographical context as possible. Only texts directly containing the relevant ethnonym or choronym associated with a specific territory were selected for further analysis. The source materials used for framework definition of the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans (handwritten documents, study manuscripts, printed monographs, press, maps) are dispersed, uncatalogued and unrefined. Without advanced digitisation allowing for automatic searches of archival and library resources, any research work is bound to be uncertain, incomplete and temporary. The search for geographical mentions of Forest Germans is reminiscent of looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack (especially with several countries and languages being involved; the relevant archival materials are or can be stored in Poland, Ukraine, Germany, Austria, Hungary and Slovakia). This is why digitisation of some of the printed monographs and press materials in a way which enabled automatic search by keywords undoubtedly made this work quicker and easier. It also likely revealed some geographical descriptions which could have been overlooked in a traditional query (Table 1). Table 1 contains information about the author and date of creation of the source, description or geographic context of a mention of Forest Germans and reference to the figure with geographical interpretation of the text.

Table 1. Settlement region of Forest Germans according to various sources, 1650–1950

Source: Biblioteka Warszawska. Pismo poświęcone naukom, sztukom i przemysłowi, 2 (1882), 304; Henryk Borcz, ‘Parafia Markowa w okresie staropolskim’, in Markowa - sześć wieków tradycji. Z dziejów społeczeństwa i kultury, ed. by Wojciech Blajer and Jacek Tejchma (Markowa: Urząd Gminy Markowa, 2005), pp. 72–189; Jan S. Bystroń, Megalomania narodowa (Warszawa: Towarzystwo Wydawdnicze „Rój”, 1935), p. 102; Benedykt Chmielowski, Nowe Ateny, volume 4 - extended edition (Lwów, 1756), p. 341; Jerzy Mycielski, ‘Nowa książka o Galicyi’, Czas 35 (1882), No. 3 (January 4th), 1; ‘Przegląd polityczny’, Czas 37 (1884), No. 23 (27th), pp. 1–2; Adam Fischer, Lud Polski. Podręcznik etnografji Polski (Lwów-Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Zakładu Narodowego im. Ossolińskich, 1926), p. 16; ‘Emigracja chłopska’, Gazeta Narodowa 23 (1884), No. 37 (February 14th), p. 2; Zygmunt Gloger, Obchody weselne, volume 1 (Kraków: published by the author, 1869), p. 111; Jan Karłowicz, Lud. Rys ludoznawstwa polskiego (Lwów: Macierz Polska, 1906), p. 185; Ignacy Karpiński, Krótki rys ustroju dawnej Polski i poglądy na przeszłość (Warszawa: Drukarnia „Kupiecka”, 1887), p. 160; Liber status ecclesiae parochialis in villa Krzemienica, 1617–1713, Archiwum Archidiecezjalne w Przemyślu (Archdiocesan Archives in Przemyśl) [hereafter AAPrz], Mss. 1038; Wacław A. Maciejowski, Historia prawodawstw słowiańskich, volume 3 (Warszawa: Drukarnia Komissyi Rządowey Sprawiedliwości Królestwa Polskiego, 1859), pp. 356-357; Stanisław Majerski, Geografja Polski dla niższych klas szkół średnich (Lwów: Polskie Towarzystwo Pedagogiczne, Drukarnia Udziałowa, 1921), p. 60; Stanisław Majerski, Opis ziemi, volume 2, (Berlin-Wiedeń: Franciszek Bonda, J. Philipp’s printing house, 1903), p. 271, Stanisław Majerski, Geografia handlowa (Lwów: Piller and Neumann, 1912), p. 95; Ludwik Dębicki, Z dawnych wspomnień (Kraków: Spółka Wydawnicza Polska, 1903), p. XXX; Wojciech Michna, Geografia dla szkół ludowych (Kraków: “Czas”, 1879), p. 20; Stanisława Niemcówna, Wincenty Pol jako geograf (Kraków: Księgarnia Geograficzna “Orbis”, 1923), p. 61; Kasper Niesiecki, 1842 (1989), Herbarz Polski Kaspra Niesieckiego S.J. powiększony dodatkami z późniejszych autorów, rękopisów, dowodów urzędowych i wydany przez Jana Nep. Bobrowicza, volume 9, (Lipsk: Breitkopf and Härtl, 1842; reprint Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1989), p. 11; Wincenty Pol, Historyczny obszar Polski (Kraków: Drukarnia C.K. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 1869), p. 32; Wincenty Pol, ‘Rzecz o dialektach mowy polskiej’ in Rocznik cesarsko-królewskiego Towarzystwa Naukowego Krakowskiego, 17 (1869), p. 87; Franciszek Siarczyński, Słownik historyczno-statystyczno-geograficzny królestwa Galicji. T. 1. Wiadomości ogólne, rkp. [Ossolineum] (1827), pp. 140, 154, 158-161; Franciszek Siarczyński, ‘Rozprawa o starodawnych osadnikach niemieckich na Podgórzu i Rusi Czerwoney’, in: Pątnik Narodowy (Lwów: Kuhn and Milikowski, 1827), pp. 129-147; Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, volumes 2, 8, 10 (Warszawa: „Wiek”, 1880-1892), pp. 612 (volume 2), 151 (volume 8), 155 (volume 10); Józef Szujski, Die Polen und Ruthenen in Galizien, (Wiedeń: Verlag von Karl Brochasta, 1882), pp. 17-18; Józef Szujski, Polacy i Rusini w Galicyi, (Kraków: Druk W. L. Anczyca i Spółki, 1896), pp. 17-18; Aleksander Świętochowski, Historia chłopów polskich, (Poznań: Wydawnictwo Polskie, 1939), p. 557; Aleksander Świętochowski, Historia chłopów polskich w zarysie, volume 2 (Lwów-Poznań: Wydawnictwo Polskie, 1928), p. 498; Lucjan Tatomir, Podręcznik geografii Galicyi, second edition (Lwów: Seyfarth and Czajkowski, 1876), p. 59; ‘Dowcipny manewr’, Prawda 4 (1884), No. 6, pp. 62-63; Jerzy Mycielski, ‘Nowa książka o Galicyi’, Czas 35 (1882), No. 3, p. 1; ‘Petersburg, 31 marca’, Kraj 3 (1884), No. 14, p. 4; ‘Przestroga’, Prawda 5 (1885), No. 48, p. 569.

The second research step consisted in geographical analysis and interpretation of the text descriptions extracted from sources and the aforementioned map from 1923 and, as a result, in drawing up appropriate maps (Fig. 1-23.). Descriptions which placed the specified ethnonym or choronym in geographical context but were too general and imprecisely formulated to serve as the basis for defining the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans were rejected.

Figure 1–23. Settlement region of Forest Germans according to various sources, 1650–1950.

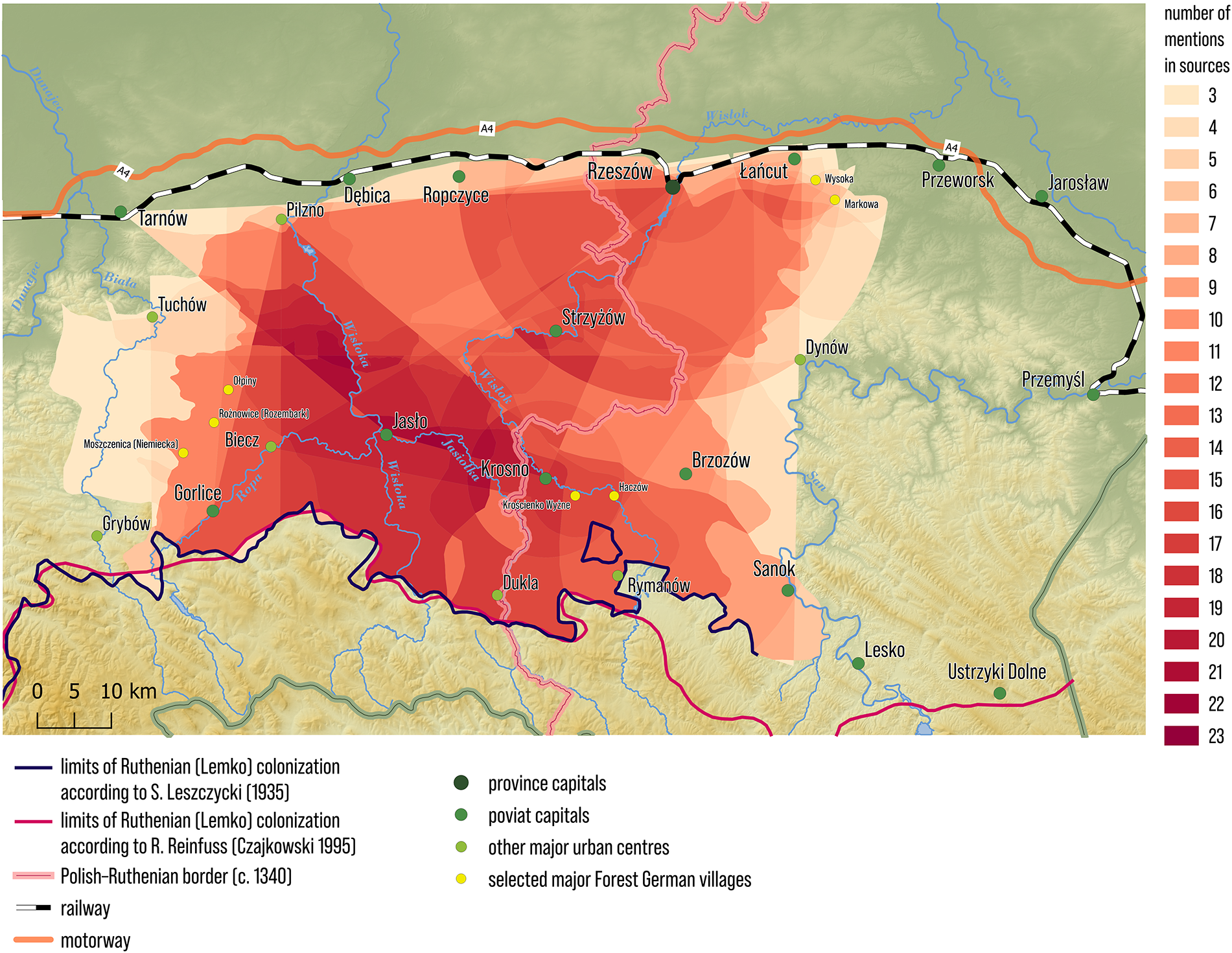

The third step involved imposing the partial maps obtained as a result of the aforementioned procedure on top of each other and covering the analysed area with the same colour of varying intensity, depending on the number of instances in the sources and the coverage of individual regionalisations from the partial maps (no colour means no mentions, while the most intense colour means the highest number of mentions) (Fig. 24).

Figure 24. Borders and area of Forest Germany – areas included in the territory of Forest Germany according to the number of mentions in historical sources (1650–1950)

During the fourth step, locations indicated merely once or twice were rejected as accidental or without sufficient basis in sources (Fig. 25).

Figure 25. Borders and area of Forest Germany – areas included in the territory of Forest Germany according to the number of mentions in historical sources (1650–1950), no less than 3 mentions in historical sources

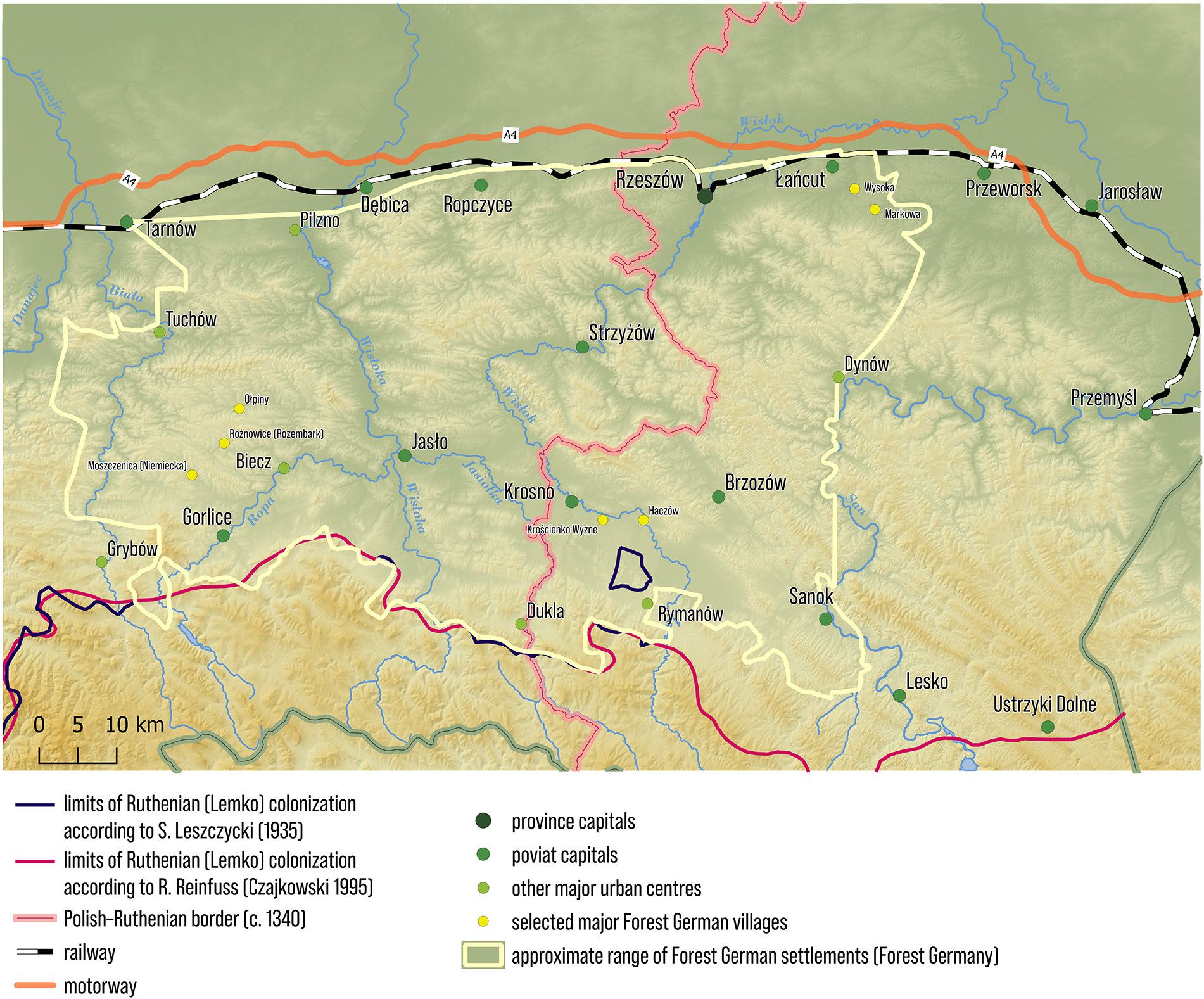

The fifth and final step consisted in drawing up a map with the border of the settlement region of Forest Germans, determined along the outline of the area defined as stated above and serving as the starting point for applying other non-specific markers to refine the borders of their settlements (Fig. 26.).

Figure 26. Approximate borders and area of Forest Germany

Each stage of research designed in this manner was accompanied by a lot of randomness or subjectivity. In view of the vast quantity of sources that should be objectively analysed, certainly not all possible geographic descriptions of the Forest German country were successfully captured. Another research challenge was the geographical and cartographic interpretation of those relatively few sources found (with their interdependence posing an additional challenge). Several detailed research challenges can be pointed out here:

-

1) In the delimitation process, only those sources which contained the term “Forest Germans” in geographical context were used; however, relatively few such descriptions were found during the more than two-year query. Although there are references to German settlements in general in the relevant geographical context, e.g. by Marcin Kromer (Kromer Reference Kromer1857, 361; Kromer Reference Kromer1984, 54-55), a 16th century Polish geographer and historian, they do not reference the analysed ethnonym or choronym, which gives rise to doubt as to the nature of the described community – whether they pertain to Germans or Forest Germans, which is important since these two communities are not identical. In the process of delimiting the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans based on sources, it is therefore preferable to choose a more conservative approach and only take into account those sources which directly refer to the analysed term in connection with a certain territory. However, this approach creates the risk that the recreated borders will be narrower than they were in reality.

-

2) Another issue is the credibility and hierarchy of the sources, as well as the basis of the geographical descriptions contained in them. The geographical references typically do not seem to be based on field research. Practical knowledge of the area described is also dubious. The same source can also be inconsistent and contain gaps, even a highly ambitious one like Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich [Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and Other Slavic Countries] (Słownik… 1880-1892). The geographical context of use of the term “Forest Germans” has appeared in sources with varying credibility and prominence, including proto-academic and popular science studies, historical-geographical and geographical dictionaries, church documents, opinion pieces or press, which makes comparison and compilation of information even more difficult, especially since higher credibility and prominence of a source does not always go hand in hand with the precision of the geographical description.

-

3) Geographical interpretation of the available source descriptions has proven to be quite difficult. The geographical descriptions found are unsystematic, imprecise, exemplifying, partial, frequently unclear and interdependent. They also contradict each other. Meanwhile, each source obviously required subjective, unambiguous and arbitrary interpretation in the process of its translation onto a map.

-

4) Another issue is the “chronological interpretation” of the geographical descriptions extracted from the sources. The range of settlements of Forest Germans certainly changed throughout centuries, so combining geographical hints from approximately 300 years (from the 17th to the 20th century) to draw up a single, aggregate map creates a somewhat ahistorical spatial reality. However, in view of the sparsity of sources, abandoning this approach puts the very determination of the region’s borders into question. The settlements from which the Forest German community emerged date back to the mid-14th century, but the first use of the ethnonym was only recorded in the second half of the 17th century, similarly to its first placement in geographical context (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 114-116). On the other hand, the choronym was only used for the first time in the 19th century. This gives rise to another element of uncertainty – the borders of the region inhabited by Forest Germans from the 14th century until the second half of the 17th century cannot be determined. Yet another area of uncertainty is due to the fact that the original geographical references (17th–18th century) are geographically narrower than later ones (19th–20th century). This gives rise to the hypothesis – which is impossible to confirm at the current stage of research (perhaps at all due to the exceptionally sparse sources, of three geographical descriptions prior to 1800) – that the relatively small original settlement area of Forest Germans in the 17th–18th century (“true” Forest Germans?; “lesser Forest Germany”) was somewhat artificially expanded to cover a larger territory in the 19th century (“greater Forest Germany”). Perhaps it was then that the ethnonym and choronym was expanded beyond the borders of the original “lesser Forest Germany” to cover new territories, which were nevertheless subject to processes analogous to those within the former territory in the past. However, this hypothesis might be completely false in connection with the insufficient number of sources that would allow for sensible reasoning or at least for its verification. The quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the corpus of currently known geographical names from the settlement region of Forest Germans also prevents recreation of its spatial evolution on their basis. Finally, the lack of common awareness of Forest Germans creates tension between subjective and objective existence of their settlement region.

The issue of delimiting the southern and eastern border of the settlement region of Forest Germans

While western, northern and partly eastern borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans can be considered somewhat by definition unclear and fluid (given the unclear criteria – in the Polish historical, cultural and geographical context – of division of Poles into Forest Germans and non-Forest Germans, as well as given the fact that they are supposed to distinguish this Polish cultural group from other Poles), at first glance, the southern and partly eastern border of their settlement region seems clear, determined by the (seemingly) distinct ethnic and religious border separating Poles from the Ruthenian population (including the Lemkos in the south) in the first half of the 20th century. However, this border is also imprecise and uncertain in different respects:

-

1. Due to the problem with definition of Forest Germans, as well as the lack of common Forest German identity: now and in the past, the Polish-Ruthenian border between the Biała and San rivers cannot be arbitrarily considered identical with the Forest German-Ruthenian border. This is highly probable, but not absolutely certain.

-

2. Precise delimitations of the northern border of Ruthenian settlements come from a period when Forest Germans were just being removed or had already been eliminated from academic and popular discourse. Therefore, the maps depict the border between Polish and Ruthenian populations, alternatively the Lemkos and related peoples as well as new Polish ethnographic groups created during the interwar period (Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk Reference Solarz and Raczyńska-Kruk2023, 114).

-

3. There are several demarcations of Lemko settlements drawn up on maps, which – despite being generally consistent – differ when it comes to details. In 1935, Stanisław Leszczycki noted, in reference to the borders of the Lemko Region, that its western part (situated to the west of the water divide of Jasiołka add Wisłok) is characterised by a sharp, linear Polish-Lemko border, whereas the eastern part exhibits high intermixing of the populations, resulting in the Polish-Lemko border to the east of the aforementioned water divide being blurry and difficult to define (Leszczycki Reference Leszczycki1935, 64-66). This situation is additionally complicated by the fact that Polish settlements to the south of the designated Polish-Lemko border and, respectively, Ruthenian settlements to the north of that border were also island-like (cf. the Ruthenian community of Zamieszańcy).

-

4. The border of Wallachian and Ruthenian settlements varied over time. These settlements emerged in a settlement vacuum on the border between Poland and Hungary at the time and gradually expanded to reach their final limits from the first half of the 20th century. Initially, they tended to cover uninhabited areas, but with time, they also entered areas which had already undergone Polish-German colonisation (Krasnowolski Reference Krasnowolski2010, 78-79, 90-92).

-

5. The existing Polish-Lemko delimitations pertain to a social reality that has not existed since the turn of the 1940s and 1950s. After 1947, the previous Polish-Ruthenian border in the Polish Carpathians became a relic as a consequence of mass compulsory resettlements to the USSR (1940–1941, 1944–1946) and Operation Vistula (resettlement within the borders of communist Poland in 1947) as well as migration of the Polish population (Barwiński Reference Barwiński2011, 140-142), including possibly Forest Germans, to depopulated territories. In view of the foregoing, after 1947, the border of the settlement area of Forest Germans might have moved to the south and east, beyond the former Polish-Ruthenian settlement border. However – even if all inhabitants of the Polish Carpathians to the north of the former Polish-Ruthenian border between the Biała and San rivers were hypothetically recognised as Forest Germans – given the intermixing of the populations in a settlement vacuum and the lack of adequate research and data, it would still be difficult to determine the contemporary southern and eastern range of Forest German settlements.

Conclusions

Defining the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans, including its delimitation based on sources that place the relevant ethnonym and choronym in geographical context, is difficult for the multiple reasons stated above and at the same time it may be of great importance in the context of complicated Polish-German relations. The picture obtained as a result of the source analysis presented here is merely preliminary. It requires further definition based on other indicators (toponyms, anthroponyms, traces of spatial layout of villages established in the Middle Ages under German law, location of settlement vacuums on the eve of colonisation under German law, other preserved traces of material and non-material culture, genetic test results). At the same time, it is fluid, subjective, hypothetical and ultimately ahistorical, existing outside the past and present. Paradoxically, it might only be adequate in relation to the future, when it will probably materialise in the form described in this article for the very first time (this is the first attempt at precise determination of its borders in geographical literature). Therefore, when tackling this crucial task – pertaining to a densely populated region that has retained settlement continuity since the Middle Ages – the criteria, sources and their interpretations should be chosen diligently, critically, carefully and prudently. Last but not least, another source of uncertainly is the tension (which is difficult to resolve in the above research) between the reconstructed world of Forest Germans that realistically existed in the past and its image created here based on subjectively interpreted sparse and unclear geographical descriptions. Hence, the picture obtained here serves as the starting point for further research, aimed at its verification, further definition and disambiguation.

Financial support

This work is a result of the research project No 2019/35/B/HS3/01274, financed using the funds of the National Science Centre, Poland.

Disclosure

This article is a result of the research project No 2019/35/B/HS3/01274, financed using the funds of the National Science Centre. Its fragments and some maps form a part of a chapter on the borders of the settlement region of Forest Germans, to be published in Polish, English and German in 2025-2026 as a monograph finishing the project, and a review article on Forest Germans in 2025 (in the case of the article only three summary maps).