1. Introduction

This paper reports on an experimental study of grammatical gender among 12-year-old children in Oslo, Norway. Over the last two decades there has been extensive research on grammatical gender in Norway, documenting an ongoing change from a three-gender (masculine (M), feminine (F), neuter (N))Footnote 1 to a two-gender system in several dialects; Oslo (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018), Tromsø (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021), Trondheim (Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024), and also in contact dialects such as Nordreisa and several Finnmark dialects (Conzett et al. Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011, Stabell Reference Stabell2016) and multiethnolects (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009).Footnote 2 The change involves loss of feminine gender (which merges with the masculine forms), resulting in a two-gender system with common (C) and neuter. Typically, the feminine indefinite article ei and the feminine prenominal possessives mi/di/si are lost, while the definite suffix used with the previously feminine nouns, -a, and the postnominal possessives, remain (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024). The result is a more complex declension system for common gender, where the previously feminine nouns allow two definite suffixes (-a and -en) and two sets of postnominal possessives (mi/di/si and min/din/sin) that immediately follow the definite suffix, while previously masculine nouns only allow one form (-en and min/din/sin). Our results show that the loss of feminine gender is complete in the Oslo dialect in that ei and feminine prenominal possessives are no longer in use. Furthermore, the declension class associated with previously feminine nouns is also affected, in that the definite suffix -a and postnominal possessives are less frequently used. We argue that the erosion of the declension system is due to a lack of a systematic mapping determining the distribution of the definite suffix -a, also when immediately followed by a postnominal possessive. We compare two areas of Oslo, East and West, and in accordance with Lødrup’s (Reference Lødrup2011a) findings, our study shows that the process is more advanced in Oslo West than in Oslo East.

An ongoing debate concerns the status of the definite suffix and the feminine postnominal possessive (e.g. Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997, Enger Reference Enger2004a, b, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, b, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021, Åfarli, Nygård & Riksem Reference Åfarli, Nygård and Ramsevik Riksem2022, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024), i.e. whether they are exponents of gender or not. Based on our data, where we see optionality between the use of -a and -en, we discuss the status of the definite suffix and argue for an analysis where -a and -en are declension class markers associated with common gender. Occasional occurrences of previously masculine nouns with previously feminine forms indicate that the 12-year-olds in our study do not have issues with gender per se, but with the declension classes associated with common gender. Furthermore, our data confirm that the previously feminine forms of the possessives may still occur, but only when conditioned by the presence of the -a suffix on the noun, e.g. the first person form mi in boka mi ‘my book’, while this form is not allowed if the definite suffix is the one occurring with previously masculine nouns (-en), i.e. *boken mi. In the latter case, the form has to be boken min, i.e. with the previously masculine possessive. We argue that this supports Svenonius’s (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) analysis of the previously feminine possessive forms (such as mi ‘my’) as allomorphs of common gender possessives when occurring in postnominal position (see also Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024).

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides relevant background on grammatical gender in Norwegian, the Oslo dialects (East and West), and previous research. Our research questions are presented in Section 3, while methodology and participants are presented in Section 4. Our results are provided in Section 5, whereas Section 6 contains a discussion of our findings. We summarize and conclude in Section 7.

2. Background

2.1 Gender in Norwegian

Unlike its sister languages in Scandinavia, Swedish and Danish, which only have two grammatical genders, spoken Norwegian has traditionally had, and some varieties still have, a three-gender system with masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns (an exception being Bergen, where the three-gender system was lost centuries ago; see e.g. Jahr Reference Jahr and Håkon Jahr1998, Reference Jahr2001).Footnote 3 In the two written standards used in Norway, Bokmål and Nynorsk, a system with three genders is allowed and in fact obligatory for Nynorsk. However, since Bokmål is originally based on written Danish, users of this variety may – and often do – write Bokmål with just two genders, common and neuter. This reflects the change that has taken place historically in some Germanic languages (Dutch, Swedish, Danish), i.e. a loss of feminine gender, resulting in feminine forms merging with the masculine.

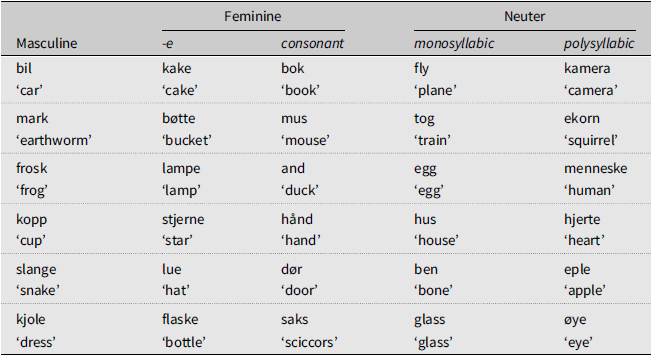

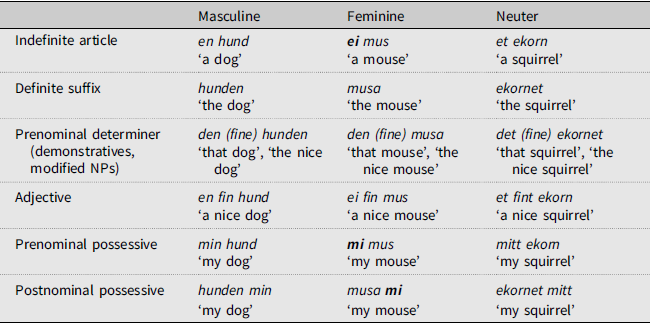

In the three-gender system of spoken Norwegian, illustrated in Table 1, the three genders are marked in the singular on indefinite articles, other prenominal determiners, adjectives, and pre- and postnominal possessives. The gender opposition is neutralized in the plural. Additionally, the definite suffix in Norwegian has three different forms, typically coinciding with the gender of the noun. Note the important fact that there is considerable syncretism between masculine and feminine forms, which means that the feminine is distinguishable from the masculine generally in only two forms, the indefinite article and the pre- and postnominal possessives (as well as a few additional forms; see Section 2.2 for specific information about the Oslo dialect). In Table 1 we use the possessives min/mi/mitt which are the three gendered forms of the first person possessive. Norwegian has separate possessive forms also for second person (din/di/ditt) and third person (sin/si/sitt); the latter are reflexive possessives. As the variation in person is not relevant for our study, we will use the notation MI, MIN, and MITT referring to all three persons, not first person only.

Table 1. Overview of the three-gender system of Norwegian

According to the standard definition of grammatical gender stated in Hockett (Reference Hockett1958) and Corbett (Reference Corbett1991), gender is agreement between a noun and other words which carry the morphological gender marking, e.g. articles, verbs, or adjectives. Thus, according to this definition, the definite form in Norwegian is not an exponent of gender, as definiteness is marked as a suffix on the noun itself. There is considerable disagreement among scholars with respect to the status of the definite suffix: Historically, the suffixes have evolved from postnominal demonstratives which expressed gender (see e.g. Stroh-Wollin Reference Stroh-Wollin2016 for this development in Scandinavian), and the reference grammar of Norwegian thus considers them to be gender forms (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997), as do some other scholars, e.g. Åfarli et al. (Reference Åfarli, Nygård and Ramsevik Riksem2022) and Johannessen & Larsson (Reference Johannessen and Larsson2015). Others consider them to be markers of declension class (e.g. Enger Reference Enger2004a, Reference Enger and Olivier2018, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Lohndal & Westergaard Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2016, Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2021, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017); see also Berg (Reference Berg, Cennamo and Fabrizo2019) for an overview of this discussion. A common argument for the former view is that the three suffixes coincide with gender, in that -en is used with masculine, -a with feminine, and -et with neuter nouns (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:150). An argument for the latter view, in addition to the standard definition mentioned above, is that the definite suffix does not behave like gender forms in development, in that it is acquired much earlier by Norwegian children (e.g. Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013, Busterud & Lohndal Reference Busterud and Lohndal2022) and it is considerably more stable in a situation of language change (e.g. Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024).

A somewhat similar discussion exists for the possessives, where a distinction is often assumed between the pre- and postnominal forms (see Table 1); that is, while the prenominal possessive is a clear gender marker, the status of the postnominal form is unclear.Footnote 4 Although it is a separate word and thus constitutes a gender marker according to Hockett’s (Reference Hockett1958) definition, it behaves more like a suffix in that nothing can intervene between the noun and the possessive. In recent research on the loss of feminine gender in spoken Norwegian (see Sections 2.2 and 2.3), the two possessives have been shown to develop differently: while the feminine prenominal possessive is undergoing a change, e.g. in the first person from mi to min ‘my’ (i.e. from feminine to common gender), the postnominal possessive is typically retained in the original form mi. This means that speakers produce min mus, but musa mi ‘my mouse’ (see Table 1). As mentioned in the Introduction, the use of the (previously feminine) postnominal possessive is dependent on the definite suffix -a, so that -a MI is a grammatical combination, while -a MIN and -en MI are not.

While Fretheim (Reference Fretheim, Ernst Hakon and Ove1985), Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001), Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011a), and Conzett et al. (Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011) have analysed the postnominal possessives as suffixes, Svenonius (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) takes a somewhat different approach (see also Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024). He argues against a suffixal analysis, based on data provided in Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011a,b) that a postnominal possessive in a two-gender dialect may have scope over coordination (e.g. buksa (mi) og lua mi ‘pants and hat my’) and also that the noun may undergo ellipsis in coordinated structures, e.g. den nye lua mi og den gamle _ din ‘the new hat my(f) and the old _ your(m)’. The existence of such examples is difficult to explain if the postnominal possessive is considered to be a suffix on the noun. Instead Svenonius (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) analyses the existence of previously feminine postnominal possessives in two-gender dialects as the result of phonologically conditioned allomorphy, where the form of the possessive is conditioned by the context of the immediately preceding vowel in the prosodic phrase (see also Enger Reference Enger2004a:138). That is, the previously feminine forms (mi, di, si) are simply allomorphs of the common gender forms (min, din, sin), meaning that they are variants of the common gender possessives which appear in specific contexts only. Furthermore, common gender nouns may have either -a or -en as the definite suffix, depending on declension class, i.e. for previously feminine nouns boka or boken ‘the book’, while previously masculine nouns only appear with -en, e.g. bilen ‘the car’. If the definite suffix on the noun is -a, the grammar will choose the previously feminine form MI (as in boka mi ‘book my’) while in all other cases, the selected form agreeing with a common gender noun will be MIN in prenominal as well as in postnominal position, e.g. min bok, boken min for previously feminine nouns and min bil, bilen min for previously masculine nouns. This means that following Hockett’s (Reference Hockett1958) definition, the postnominal possessives are exponents of gender, as they are separate words agreeing with the noun. More specifically, in two-gender dialects, the postnominal possessive MITT expresses neuter gender, while the postnominal allomorphs MIN and MI express common gender.

2.2 Gender in the Oslo dialect

The Oslo dialect landscape is characterized by at least two distinct varieties built on different historical origins (e.g. Johannessen Reference Johannessen and Helge2016). One is associated with the eastern, traditionally working-class areas of Oslo and is related to the surrounding central eastern (rural) dialects, with corresponding or related forms both in the inland areas around the city and in the coastal areas around the Oslo fjord. For our purposes, it is important that this variety is traditionally characterized by a three-gender system, originally with even more exponents of feminine gender than the ones included in this study (see Table 1); the system of eastern Oslo included feminine forms of some adjectives and prenominal determinatives and pronouns (e.g. lita ‘small’, noa ‘some’, inga ‘none’, as well as hu ‘she’ used to refer to inanimate feminines (Larsen Reference Larsen1907)). The other traditional Oslo variety is associated with the western, upper-middle class area and is based on the Dano-Norwegian koiné associated with the speech of the urban educated classes, sometimes referred to as colloquial standard (Haugen Reference Haugen1966:31) or educated casual style (dannet dagligtale) (Torp Reference Torp2005:1428). This variety has a two-gender system, which is to be expected given its close relationship to the Danish origin. It is worth noticing that the establishment of the Bokmål written standard (until 1929 called Riksmål) is based on (among other things) the everyday speech of the urban upper-middle classes, which had relatively few cues to support a three-gender system. Even though the modern Bokmål written standard today contains many optional and alternative forms, including a three-gender system, the latitude in the use of these options has been narrowed in recent years. Hence, the inventory of the western variety corresponds with, and its users may seek support in, a widely used written standard.

Due to decades of gentrification, new migration patterns, dialect contact, raised education levels, and social mobility, it is not straightforward to establish a clear-cut (socio-) linguistic contrast between Oslo East and Oslo West today (see Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2019). Nevertheless, fairly recent studies have shown how exponents of grammatical gender convey different meanings associated with ‘eastern’ or ‘western’ identities (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2013, Reference Stjernholm2019, Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021), and in experimental studies, speakers perform differently depending on their socio-geographical belonging (Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018). Our choice to include data from young participants from both Oslo East and West rests on a strong assumption that this will reveal some differences. Support for this assumption is also found in Johannessen (Reference Johannessen, Janne Bondi and Kristin2008:237), who extracted a group of what she refers to as ‘typically feminine words’, such as elv ‘river’ and avis ‘newspaper’, from the spoken language corpus NoTa-Oslo (collected in 2005), and showed how a declination pattern that favours the definite suffix -a over the definite suffix -en is found among speakers in the eastern parts of Oslo. In Oslo East, 62% of the definite forms of these typically feminine words have the definite suffix -a, whereas the corresponding number for Oslo West is 27%. Research has also pointed out that several speakers turn to ‘-a suffixes’Footnote 5 as an important signal, a shibboleth, for expressing and/or determining belonging to the eastern parts of the city (e.g. Western Reference Western1977, Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2013, Reference Stjernholm2019, Ims Reference Ims2019, Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021:130).

In addition to -a suffixes, the use of the feminine indefinite article ei – often realized as a monophthong /e/ (see Hårstad & Opsahl Reference Hårstad and Opsahl2021) – has been found to characterize the traditional eastern variety of Oslo. However, the feminine indefinite article has (more or less) disappeared among younger speakers of the Oslo varieties and is almost absent from some of the latest available data sets on Oslo speech (ibid., Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a). In fact, very few exponents of feminine gender are found in these studies. Still, the feminine article is sometimes included in stylistic performances and identity work corresponding to indexical meanings associated with the traditional eastern dialect, among writers, musicians, and comedians (Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2013, Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021). Hence, at least some differences between the two socio-geographical areas referred to as ‘East’ and ‘West’ can be expected in our study as well.

Our main questions in this study are related to feminine agreement. However, previous research on urban eastern Oslo varieties has displayed cases where neuter nouns are combined with the masculine article en, also in cases involving L1 speakers (e.g. Opsahl & Nistov Reference Opsahl, Nistov, Pia and Bente Ailin2010). Moreover, it is described as a feature characteristic of northern contact communities involving Norwegian, Sami, and Kven (Sollid et al. Reference Sollid, Conzett, Mette Johansen, Kurt, Steffen and Karoline2014) and of American-Norwegian heritage language (Johannessen & Larsson Reference Johannessen and Larsson2015, Lohndal & Westergaard Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2016). A tendency to overgeneralize the masculine gender to neuter nouns is typical of many speakers learning Norwegian as their L2 (Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2010, Anderssen & Busterud Reference Anderssen and Busterud2022). In both northern Norway and in Oslo, it has so far only been a marginal phenomenon, but it nevertheless receives metalinguistic attention (Sollid et al. Reference Sollid, Conzett, Mette Johansen, Kurt, Steffen and Karoline2014:200, Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021). In contemporary novels depicting urban youth communities in Oslo, overgeneralizations of the masculine gender to neuter nouns are common (e.g. Anda Reference Anda2019:62). These factors raise the question of how young Oslo speakers treat neuter nouns, which in turn may provide an impression of the degree to which the whole gender system is affected by the ongoing change. We therefore include a research question concerning neuter gender, more specifically, neuter nouns that have been described as prone to deviant gender marking in previous studies from Oslo. Among these, consonant-final monosyllabic nouns are mentioned as relevant (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009:97). The words used as stimuli in our study further allow for an explorative comparison of similar morphophonological cues relevant not only for neuter, but across all three traditional genders, for instance a possible relationship between disyllabic words ending in -e and the -a suffix (see Section 6.2). The overall relationship between syllable structure and gender is not the focus of this study, however, and should be included in future research pertaining also to types of nouns, as discussed by Haug (Reference Haug2019).

2.3 Grammatical gender in the Tromsø and Trondheim dialects

That a two-gender system has been developing in varieties of spoken Norwegian outside of Oslo was first attested by Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015) in an experimental gender study of five different age groups speaking the Tromsø dialect (adults, adolescents, and three groups of children). Their findings showed that while adults (age 30+) generally produce the feminine indefinite article ei with feminine nouns (99%), children aged 3;6–12;8 rarely produce this form (7–15%), replacing it with the masculine en, and adolescents aged 18–19 are in between, producing ei 56% of the time. In contrast, the definite suffix -a is retained in all groups, although slightly less for the children (89% in the lowest age group (3;6–6), 95% in the next age group (6;6–8;2), and 100% among the oldest children (11;9–12;8).Footnote 6 Based on the results of the Tromsø study, Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015) argued that feminine gender is in the process of being lost in the dialect, at a surprisingly rapid speed, with an intact gender system in the adult generation and hardly any trace of it in the data of the children. In a replication study carried out in Trondheim, Busterud et al. (Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019) found even less use of the feminine indefinite article ei: The three groups of children produced 4%, 0%, and 11% of this form with (previously) feminine nouns, the adolescents 19%, and the adults 35%. This means that even the adult population produced this feminine form relatively infrequently, and the authors argue that the development towards a two-gender system probably started earlier in Trondheim than in Tromsø, and it has also progressed further. Furthermore, there is a certain indication of an incipient change in the definite suffix, in that the -a used with feminine nouns is attested somewhat less than in Tromsø, in all age groups, i.e. 77%, 89%, and 99% in the three groups of children, 97% in the adolescents, and 87% in the adults.

So far, the only attested change affected the indefinite article, but a complete loss of feminine should affect all exponents of feminine gender. As mentioned above, the only other form that generally distinguishes the feminine from the masculine is the possessive (with a few minor exceptions, as mentioned above). For this reason, the possessive was the focus of a follow-up study carried out in Tromsø by Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021), using similar age groups and a slightly adjusted experimental design. The findings showed that the feminine form of the prenominal possessive followed an identical developmental pattern to that of the indefinite article, with an almost categorical use of the feminine among the adults and hardly any in the data of the children (who would produce e.g. min bok ‘my book’ and en bok ‘a book’ with the same frequency). In contrast, the postnominal possessive used for (previously) feminine nouns followed the distribution of the definite suffix -a, meaning that it was generally intact in all age groups. Thus, the children made a clear distinction between pre- and postnominal possessives, typically producing forms such as min bok, but boka mi, which corresponds with the pattern outlined in Section 2.1.

3. Research questions

The present study investigates grammatical gender in the Oslo dialect, using experimental methods. We are particularly interested in the status of feminine gender but will also study whether neuter is affected by the ongoing change. Following up on Lødrup’s (Reference Lødrup2011a) study, we investigate whether there are still differences between eastern and western areas of the city (referred to as East and West in the following), and we want to compare our results from Oslo with results from Trondheim and Tromsø, as we expect the loss of feminine gender to be more advanced in Oslo. Furthermore, we are interested in how our results can shed light on the debate on the relationship between gender and declension class. We ask the following research questions.

-

1. Are there any exponents of feminine gender in the Oslo dialect (see Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2013, Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018)?

-

a. Is the development more advanced than in Trondheim and Tromsø?

-

b. Are there differences between eastern and western parts of the city (see Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2019)?

-

-

2. Do morphophonological cues affect the use of feminine gender or the use of the definite suffix -a and/or the postnominal possessive (-a) MI?

-

3. Are there similarities between ei and prenominal use of MI, on the one hand, and the definite suffix -a and postnominal use of MI, on the other hand?

-

4. Are monosyllabic neuter nouns more likely to occur with masculine gender, the definite suffix -en, and postnominal possessive MIN as compared with di- or polysyllabic neuter nouns?

-

5. What does the pattern in the Oslo dialect tell us about the relationship between gender and declension class?

4. Informants and methodology

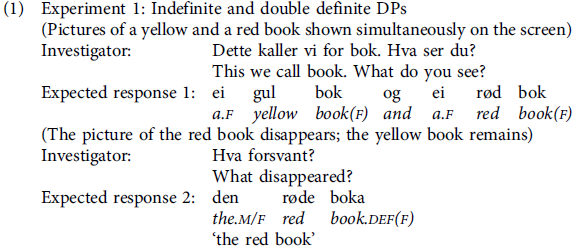

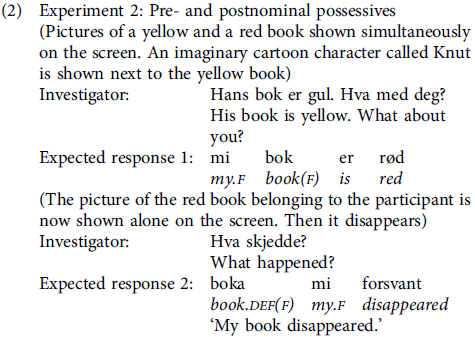

The participants in this study were 51 12-year-olds living in two different areas of Oslo – East and West.Footnote 7 There were 27 participants in the eastern group and 24 in the western group. We conducted two elicited production experiments based on the methodology used in Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021), with some changes in nouns and pictures. Experiment 1 elicited indefinite and double definite forms, and Experiment 2 elicited prenominal and postnominal possessives in a contrastive or a neutral context. The stimuli in both experiments consisted of 30 nouns: twelve feminine (six ending in a consonant and six so-called weak feminines ending in -e), twelve neuter (seven monosyllabic and five di- or polysyllabic), and six masculine nouns (see Appendix). All nouns depicted concrete objects and were presented as pictures. The nouns were presented in randomized order in the two tasks. During the elicitation procedure, the participants were shown coloured pictures of various objects depicting the target nouns. The elicitation questions and the target responses are illustrated in (1) and (2) for Experiments 1 and 2 respectively.

The experiments were conducted on a laptop computer and all responses were audio-recorded and later transcribed. A training session using plural nouns whose agreeing forms do not show gender (e.g. blå/mine ballonger ‘blue.pl/my.pl balloons’) preceded both experiments. The participants were tested individually in a quiet room at their schools. They completed both tasks on the same day. The investigators were speakers of either the Oslo dialect or another southern Norwegian dialect.

From Experiment 1, we included indefinite and suffixed definite forms in the analysis. Occasional responses where the target noun was missing were also included, as these responses contain the relevant grammatical information (e.g. ei rød _ og ei gul bok ‘a red _ and a yellow book’). From Experiment 2 we included the prenominal possessor and a combination of the suffixed definite article with a postnominal possessor.

5. Results

5.1 Indefinite articles

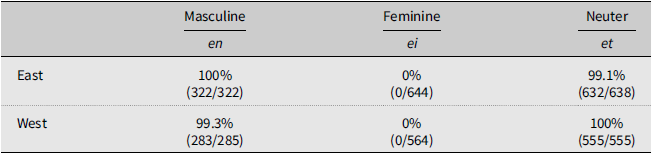

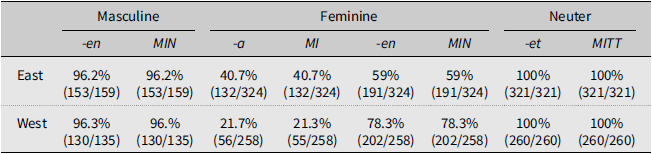

Table 2 shows the results for the use of indefinite articles with masculine, neuter, and previously feminine nouns. Previously masculine nouns always occur with en in the West and in 99.3% of the cases in the East, with a few occurrences of the neuter form et in the East. There are no occurrences of ei at all, implying that the occasional deviant forms in the masculine involve the use of et, and that deviant forms in the neuter involve the use of en. Four out of the six neuter nouns occurring with en are monosyllabic.

Table 2. Indefinite articles in Oslo East and West

5.2 Prenominal possessives

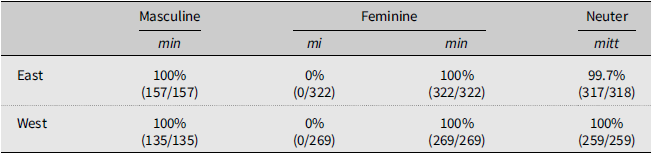

Results for prenominal possessives are shown in Table 3. Without exception, traditional masculine nouns occur with the masculine possessive min, and except for one case (min C menneske N ‘myM humanN’), neuter nouns always occur with the neuter possessive mitt. On a par with indefinite articles, the feminine possessive mi is never used. Previously feminine nouns consistently occur with the masculine prenominal possessive min.

Table 3. Prenominal possessives in Oslo East and West

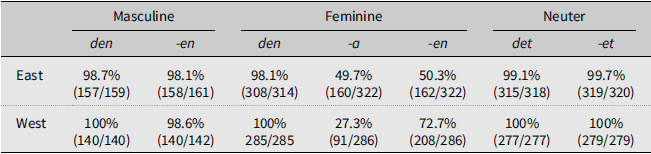

5.3 Double definiteness

Results for double definiteness are shown in Table 4. The deviant forms for neuter in the East all involve the use of the masculine/common definite article den combined with a di- or polysyllabic noun. In two of the cases the noun has the definite suffix used with neuter nouns (den grønne mennesket, ‘the green man’, den gråe flyet ‘the grey airplane’), while one single case involves the (formerly masculine) definite suffix -en (den gule ekornen ‘the yellow squirrel’). For previously feminine nouns there is an interesting difference between the East and West groups. While the definite suffix -a is used with such nouns in almost half of the cases in the East, only 27.3% occur with -a in the West. We explored the results by a logistic mixed-effects regression model using the R packages lme4 (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) and emmeans (Lenth et al. Reference Lenth, Henrik Singmann, Buerkner and Herve2018), with response as the dependent variable. The model included Condition (postnominal suffix in double definites, postnominal suffix in postnominal possessives, and postnominal possessive determiner) and Group as fixed effects as well as their interaction and random intercepts for Participants and Items. We found a significant effect of group (z value = –2.661, p = 0.007) suggesting that the participants in the West group used -a significantly less than the participants in the East group. The post hoc pairwise comparisons of postnominal forms are reported in Section 5.4. Additionally, we investigated the effect of the noun ending, which revealed no significant difference between feminine nouns ending in a consonant vs. -e (z value = 0.950, p = 0.34187). Thus, the noun ending (consonant vs. -e) does not affect the choice of postnominal suffix or possessive in double definites and postnominal possessives.

Table 4. Double definiteness in Oslo East and West

Nouns that were formerly masculine mainly occur with the -en suffix, but somewhat surprisingly, there are five nouns occurring with the definite suffix -a: den meitemarka ‘the.c earthworm.def(f)’, den slanga ‘the.c snake.def(f)’ (×3), den froska ‘the.c frog.def(f)’.Footnote 8

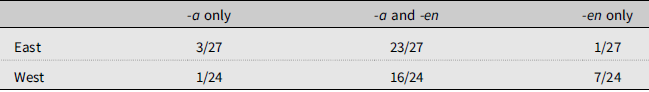

Individual results (Table 5) show that the majority of the 12-year-olds (76.5%, 39/51) use both -a and -en with formerly feminine nouns. Only four individuals (7.8%) consistently use -a, while eight (15.7%) consistently use -en. There are some minor differences between the East and West groups: While only one participant in the East group consistently uses -en, seven do so in the West. Three 12-year-olds in the East use -a consistently, while this is the case for only one participant in the West group.

Table 5. Individual results for definite suffixes with traditional feminine nouns. N participants/total

5.4 Postnominal possessives

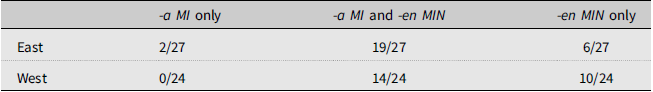

Results for postnominal possessives are shown in Table 6. In both East and West groups neuter nouns without exception occur with the neuter possessive MITT. Except for two occurrences (stjerne(t) mitt ‘star.n my. n’ and stjerna mitt ‘star.f my.n’), previously feminine nouns occur with both -a MI and -en MIN. There are no occurrences of the combinations -a MIN or -en MI. As was the case for the use of -a with double definiteness, the use of -a MI is lower in the West than in the East. Interestingly, for both groups the use of -a MI is approximately 9 percentage points lower compared with the use of -a in double definiteness: 40.7% in the East and only 21.7% in the West. The post hoc pairwise comparisons using emmeans for the logistic mixed-effects regression model reported in Section 5.3 revealed that the West group was significantly different from East in all three conditions: suffixed definite articles in double definites (z ratio = 2.661, p = 0.0078), suffixed definite articles in postnominal possessives (z ratio = 2.960, p = 0.0031), and postnominal possessives (z ratio = 2.841, p = 0.0045). It also revealed a significant effect of condition within each participant group suggesting that the use of -a MI was significantly lower than the use of -a in double definiteness (z ratio = 3.260, p = 0.0032 for East and z ratio = 3.156, p < 0.005 for West).

Table 6. Postnominal possessives in Oslo East and West

In contrast to neuter nouns, there are some unexpected, deviant uses of definite suffixes and postnominal possessives with (formerly) masculine nouns, both in the East and West groups. There are 11 deviant forms, all occurring with -a MI:Footnote 9 slanga mi (×4) ‘snake.m.def(f) my.f’, kjola mi (×3) ‘dress.m.def(f) my.f’, marka mi (×2) ‘earthworm.m.def(f) my.f’, froska mi (×2) ‘frog. m.def(f) my.f’. Note that three of these nouns also occurred with -a in double definites.

Individual results for the use of -a MI and -en MIN with previously feminine nouns are shown in Table 7. The majority of the 12-year-olds use both -a MI and -en MIN (64.7%, 33/51), but the total number is lower compared with individual results for the definite suffix. Only two out of 51 participants (3.9%) consistently use -a MI, while almost a third consistently use -en MIN (31.4%, 16/51). If we compare these numbers with the individual results for the definite suffix alone (in double definiteness constructions) in Table 5, we see that fewer participants consistently use feminine forms, while the number of participants who only use masculine/common gender forms (-en MIN) is doubled. More 12-year-olds in the West than the East group consistently use -en MIN, and no one uses -a MI consistently. One participant uses both -a and -a MI consistently.

Table 7. Individual results for postnominal possessives with traditional feminine nouns. N participants/total

5.5 Definite suffix and postnominal possessives

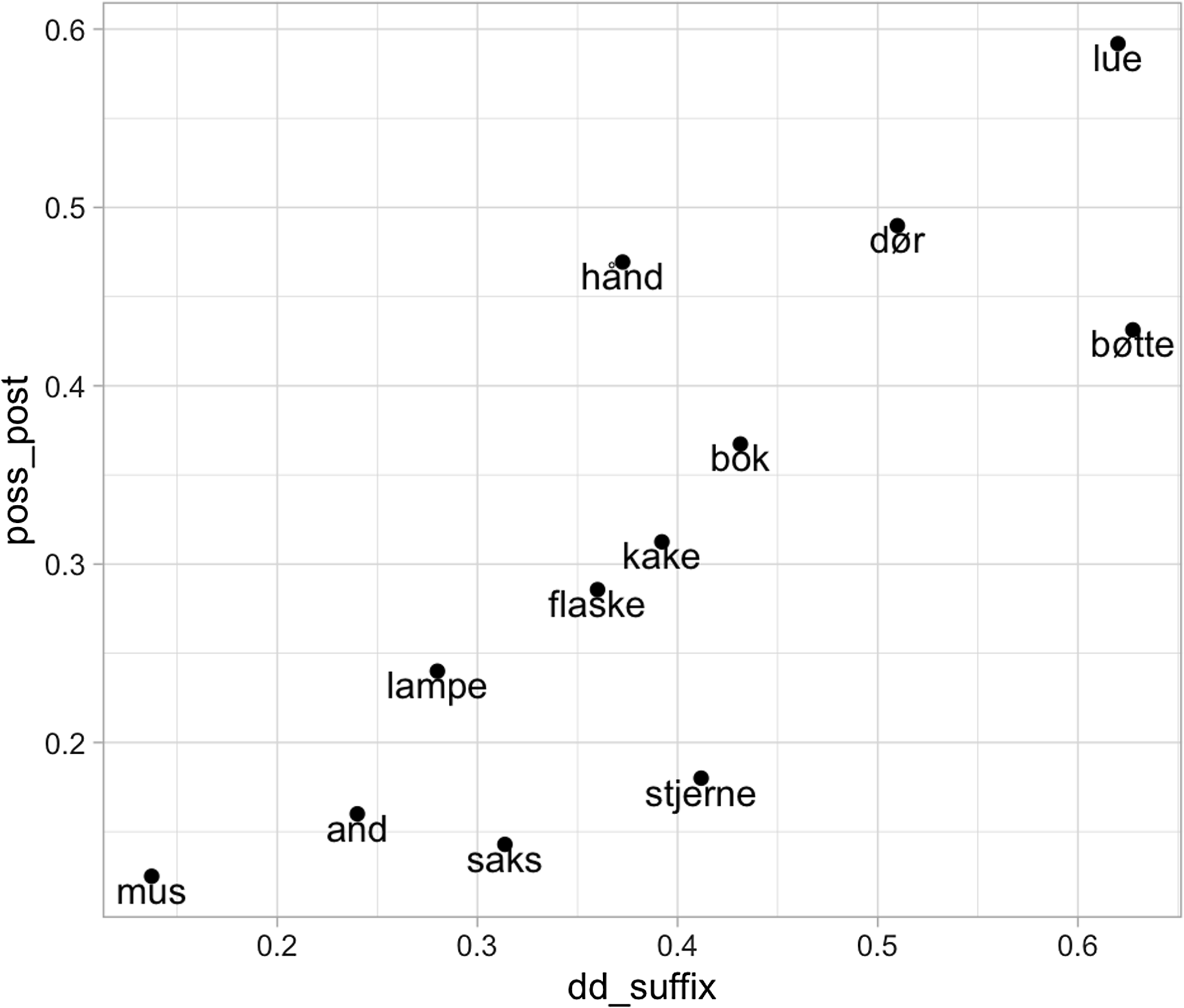

Even though the use of -a in double definites and -a MI on postnominal possessives is more frequent in Oslo East, the pattern is similar in that those nouns which often/seldom occur with -a/-a MI in Oslo East, also occur more often/seldom with -a/-a MI in Oslo West. The average group responses in Figure 1 show that both -a/-a MI and -en/-en MIN are used variably with a majority of the test nouns. At the same time, there are at least two nouns which show distinct patterns: lue ‘hat’ is used most consistently with -a and -a MI, while mus ‘mouse’ occurs almost exclusively with -en/-en MIN. Differences across individual nouns have also been found in written Bokmål; see Dyvik (Reference Dyvik2018).

Figure 1. Average use of -a and -a MI for individual feminine nouns: dd_suffix = suffixed definite articles in double definites, poss_post = postnominal possessives.

6. Discussion

A striking finding is that the feminine gender forms ei and prenominal MI are totally absent among 12-year-olds both in eastern and western parts of Oslo, although they produce a few occurrences of the definite suffix -a together with the postnominal possessive MI (see below for more on this). Our results for neuter nouns show that short monosyllabic nouns are not more likely to occur with masculine/common gender as compared with di- or polysyllabic nouns (see research question 4). While we find a few more instances of monosyllabic neuter nouns with the indefinite article en, the opposite is the case for double definites and prenominal possessives, as we find a few more instances of polysyllabic nouns with masculine forms. In this section we discuss our findings in relation to our research questions; that is, we focus on the loss of feminine gender, the new two-gender system, and the relationship between gender and declension class.

6.1 Oslo versus Trondheim and Tromsø

Unlike the data from previous research from Tromsø and Trondheim, where the indefinite article ei and prenominal possessive MI are still found among 12-year-olds, these forms are totally absent in Oslo. In this age group, Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021) found 7% and 29% use of ei in Tromsø in 2015 and 2021 respectively, and Busterud et al. (Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019) found 11% use of ei with traditionally feminine nouns in Trondheim. These three studies tested a total of five age groups and generally found less use of feminine gender with descending age, and they therefore argue for an ongoing change from a three-gender to a two-gender system. Concerning the prenominal possessive, van Baal et al. (Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023) found 11.1% use of prenominal mi among 18–19-year-olds in Trondheim, while Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021) found 16% use of prenominal MI among the 12-year-olds in Tromsø. Our results from Experiments 1 and 2 confirm that the loss of feminine gender is complete in the Oslo dialect, as the indefinite article ei and prenominal possessive MI are no longer in use (see research question 1a).

However, the most striking difference between Oslo on the one hand and Tromsø and Trondheim on the other is the difference in use of the definite suffix -a and the combination -a MI with previously feminine nouns. In Tromsø, the use of -a and -a MI is described as ‘intact and stable’ (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021:256), and in Trondheim, the occasional use of -en in double definiteness environments in the two youngest age groups (age 3;4–5;9) and adults was described as a possible ‘incipient change’ (Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019:162). Van Baal et al. (Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023) also found consistent use of -a and -a MI (97.2% and 97.9%, respectively) in Trondheim for 18–19-year-olds. Thus, the use of -a and -a MI with previously feminine nouns in Oslo differs dramatically from Trondheim and Tromsø. In total only 41.3% of the formerly feminine nouns occur with -a in double definites. A closer look at the individual data reveals interesting differences. In Trondheim, 13 out of 14 12-year-olds consistently used -a with these nouns, and only one individual used both -a and -en. In Oslo only four out of 51 individuals (7.8%) consistently use -a, and the majority (40/51) produce a mixture of -a and -en. However, there are differences between age groups in Trondheim; the two younger groups use -en a bit more than the older age groups. While no one (across all age groups) consistently used -en in Trondheim, eight individuals do so in Oslo. In Tromsø, the use of the definite suffix -a was consistent among 12-year-olds in both 2015 and 2021, and the same goes for -a MI. Even though there are some occurrences of -en and -en MIN attested in Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021:254), the authors argue that no one (across groups) uses -en and -en MIN productively.

According to van Baal et al. (Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023) and Solbakken et al. (Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024), the generalization across dialects for Norwegian is that ei and prenominal MI are lost on feminine nouns, while -a and -a MI are kept. Our data show that this is no longer the case in the Oslo dialect. We argue that this is due to the complete loss of ei and prenominal MI in Oslo. As a result of this, the associated declension class forms are now in competition within common gender, i.e. -a vs. -en. As the latter form is massively more frequent than the former (occurring with all formerly masculine nouns), this form wins out, and the definite suffix -a and postnominal MI become vulnerable and are currently in the process of being lost. We return to this in Section 6.5.

6.2 Oslo: East versus West

Research question 1b asks whether there are differences between East and West. While the indefinite article ei and prenominal possessive MI are generally lost, the definite suffix -a and postnominal possessive MI are still found in both eastern and western Oslo (see Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a). Our data show that in both East and West the definite suffix -a is used significantly more frequently than the postnominal possessive MI. This might be due to the definite suffix being more frequent in the input as compared to the postnominal possessive. However, this is more likely a task effect, as the experiment was designed in such a way that the participants, for every noun, always produced the prenominal possessive immediately before the postnominal possessive. Since prenominal MI has disappeared from the two-gender Oslo dialect, the participants always produced MIN prenominally with formerly feminine nouns. Thus, because of the methodological design, they might have primed themselves to produce MIN instead of MI also postnominally with these nouns.

As we saw in Section 2, previous studies have shown that western Oslo is more advanced when it comes to the loss of feminine gender. Features of the upper middle-class variety are arguably important in this regard, as this variety has a two-gender system (see Section 2.2), receiving continuous support from the most widely used variants of the written standard. Interestingly, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011a:133) predicted that children in Oslo will soon have a two-gender system. Our results show that only 12 years later, this is in fact the case.

Haug (Reference Haug2019) investigated the use of -a vs. -en on the 69 most frequent feminine nouns in the NoTa-Oslo corpus, collected in 2005, and found 64% usage of -a in eastern and 36% in western parts of the city. Even though the definite suffix -a is still in use, we also see a decline in the use of this suffix with double definites with 49.7% usage in Oslo East and 27.3% in Oslo West (see Table 4). The presence of -a and -a MI in the data from the East group may be seen as the result of the above-mentioned ‘shibboleth’ function associated with ‘-a suffixes’ in general, i.e. concerning both verbal and nominal domains, used as an important measure to express belonging to the eastern parts of the city (e.g. Ims Reference Ims2019, Stjernholm Reference Stjernholm2019, Opsahl Reference Opsahl2021:130). These features are more likely to be found in the input of the children growing up in eastern parts of Oslo. While 10 out of 27 speakers in eastern Oslo in the Lundquist & Vangsnes (Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018) study consistently produced -a with formerly feminine nouns, only three out of 27 did so in our study. This suggests a continued decline in the use of -a in eastern Oslo too.

We found no difference between East and West for formerly feminine nouns ending in a consonant vs. nouns ending in -e (see Figure 1). This is different from findings in Haug (Reference Haug2019), where there was a higher proportion of the -a suffix with nouns ending in -e in both eastern and western parts of the city. Haug also found more use of -a on nouns not ending in -e in the eastern part (65.9%) as compared with western Oslo (33.7%). These differences in findings might be due to our experiment only involving certain types of concrete nouns, while Haug investigated a spoken corpus with variation in the type of nouns. Further research is needed to detect whether there are still differences between different types of nouns (abstract vs. concrete, animates vs. inanimates, etc.) in the Oslo dialect. Taken together with other facts discussed in Sections 6.4 and 6.5, we argue that overall, what we currently see in the dialect of Oslo is the erosion of the declension system, which is a separate and more gradual process than the disappearance of the feminine gender markers ei and prenominal mi.

6.3 Ei and prenominal MI versus -a and -a MI

Research question 3 asks whether there are similarities between ei and prenominal use of MI on the one hand, and the definite suffix -a and postnominal use of MI, on the other hand. That is, do they behave as our theoretical assumptions and previous findings would lead us to expect? Our data show that ei and the prenominal possessive MI behave similarly in that they are no longer used among 12-year-olds, while the definite suffix -a and the postnominal possessive MI are still used to some extent.

As discussed above, there is a dissociation in the use of ei and the definite suffix -a found in several studies of L1 Norwegian (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, Busterud & Lohndal Reference Busterud and Lohndal2022, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024), in that whereas ei is lost the definite suffix -a is retained. A similar correspondence between ei and prenominal MI as well as -a and postnominal MI has been found both in L1 (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Solbakken et al. Reference Anderssen and Busterud2024) and L2 Norwegian (Anderssen & Busterud Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2022). These findings have been invoked as arguments in favour of a distinction between gender and declension class, where only ei and prenominal MI are exponents of feminine gender (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017, Lohndal & Westergaard Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2021, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024). Our data provide further support in favour of this conclusion, raising the theoretical question of what the patterns in the Oslo dialect tell us about the relationship between gender and declension class.

6.4 Gender and declension class

Research question 5 asks what the pattern in the Oslo dialect can tell us about the relationship between gender and declension class. Ei and prenominal MI are indisputable exponents of feminine gender, while the status of the definite suffix -a and postnominal MI is less clear; see Section 2. The fact that -a and -a MI are still being produced in Oslo, while ei and prenominal MI are totally absent, shows that the changes in these phenomena do not go hand in hand, as would be expected if they were part of the same grammatical phenomenon.

For the sake of the argument, let us pursue the possibility that definite suffixes and postnominal possessives are exponents of feminine gender, as has indeed been assumed by some scholars (see Section 2). If -a and -a MI were exponents of feminine gender, this would imply that they reflect assignment of feminine gender to nouns with which these morphemes occur. One might therefore expect to find other exponents of feminine gender used on the same noun by the same participant. Our data clearly show that this is not the case, as ei and prenominal MI are absent in the data set. The fact that only four out of 51 participants consistently used -a on double definites with traditionally feminine nouns, and only two out of 51 participants consistently used -a MI with such nouns, further suggests that -a and -a MI do not reflect assignment of feminine gender on the nouns with which they occur.Footnote 10

If one were to maintain an analysis where suffixed forms are exponents of gender, one solution would be to say that our participants have assigned feminine gender to the nouns in the definite form and masculine in the indefinite form, i.e. they have some kind of ‘mixed’ gender assignment system.Footnote 11 Another possibility would be to say that that these nouns can be assigned two genders, both masculine and feminine. Lastly, one could assume that the nouns are still feminine and suffixes mark gender, but there is more syncretism in the system than before. All options are highly unlikely and predict a range of forms that are not attested. Furthermore, they cannot explain why indefinite articles and prenominal possessives, without exception, are masculine, while suffixed forms vary between feminine and masculine forms. Most of the participants (40/51) used both -a and -en with traditionally feminine nouns in double definites as well as -a MI and -en MIN with postnominal possessives (33/51 participants). Thus, most of the occurrences of -a and -a MI are produced by participants who also produce -en and -en MIN with (previously) feminine nouns. None of these participants used ei or prenominal MI, and it is highly unlikely that individuals who use both -a and -en with traditionally feminine nouns have assigned feminine gender to the nouns in question, when we have no other indications of the existence of feminine gender in their mental grammar. We will argue that it is more reasonable to assume that formerly feminine and masculine nouns are categorized as common gender in the grammar of these speakers, and that -a and -en represent two possible declension classes associated with common gender.Footnote 12 Furthermore, following Svenonius’s (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) analysis (see Section 2.2), we argue that the postnominal possessive MI in two-gender dialects is an allomorph of MIN expressing common gender. This means that although the form MI is kept, the postnominal possessive no longer expresses feminine gender. As argued by Svenonius, the choice of MI vs. MIN for common gender nouns is conditioned by the morphophonological form of the immediately preceding definite suffix; -a or -en. Thus, neither the definite suffix -a nor the postnominal possessive MI express feminine gender in the two-gender dialect in Oslo. While the definite suffix represents declension class, the postnominal possessive MI is an allomorph of MIN expressing common gender, conditioned by the form of the definite suffix -a.

Assuming a two-gender system where definite suffixes are analysed as declension class markers also explains the empirical patterns found across dialects (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, Busterud & Lohndal Reference Busterud and Lohndal2022, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024), where we see that the change in the gender system does not go hand in hand with a change in the definite suffix: the definite article ei and prenominal possessive MI can disappear without any change in the use of definite suffixes. However, the loss of feminine gender creates a situation which paves the way for a subsequent change in the declension system, as the two declension classes of common gender are now in competition. Under the assumption that free morphemes and the definite suffix were both exponents of grammatical gender, a reverse order of change is theoretically possible: the suffix could in principle change without any changes in the indefinite article and prenominal possessive. However, this would be an unlikely change. It is much more common for change to happen when there is a situation of competition, i.e., in this case, two (non-productive) declension classes that belong to the same gender, especially when there are no morphophonological rules that will tell a learner which declension class to choose for a particular noun.

In summary, the data from this study strengthen the claim that neither the definite suffix -a nor the postnominal possessive MI are exponents of feminine gender in a two-gender dialect (see research question 5). Instead, the suffix is a declension class marker (as it was also before), while the postnominal possessive MI is an exponent of common gender. Put differently, even though these forms still exist in the Oslo dialect, they cannot be used as a diagnostic for the existence of feminine gender (see Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017:344).

Another group of data that speaks to this issue involves what we refer to as ‘deviant’ forms; that is, forms that are not expected. These are mainly of two types: either as the use of common gender forms with neuter nouns, or the use of -a and -a MI with formerly masculine nouns. An example of the first type is en (c) svart ekorn (n) ‘a.c black squirrel.n’ (neuter nouns never occur with -a and -a MI). These cases can be analysed as overgeneralizations of common gender as the default gender in a two-gender system (similar to the function of masculine in a three-gender system). The second type involves the occasional cases such as den slanga ‘that snake’ and kjola mi ‘my dress’. We argue that these are relevant for the discussion of gender versus declension class.Footnote 13 Given that the majority of informants who produce these examples use -en and -en MIN with the same nouns in other parts of the experiment, it cannot be that these informants have assigned feminine gender to these formerly masculine nouns. Instead, these data suggest that the competition between the two declension classes associated with common gender, caused by the loss of feminine gender, also occasionally affects formerly masculine nouns. According to this analysis, the speakers in question do not have problems with gender per se, but with declension classes associated with common gender. This claim is strengthened by the fact that neuter nouns never occur with -a and -a MI, and that common gender nouns never occur with -et and -et MITT, which we would expect if the entire gender system were changing. We return to this in Section 6.5.

The use of -a and -a MI used on previously masculine nouns can also shed light on the discussion regarding the status of the postnominal possessive in Norwegian. According to Svenonius (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017), the postnominal possessive MI is an allomorph of MIN conditioned by the morphophonological form of the definite suffix of the immediately preceding noun -a. Even though the feminine form of the postnominal possessive is retained, it no longer expresses feminine gender. The data from Oslo show a total of 11 occurrences of postnominal use of MI together with formerly masculine nouns. Importantly, when postnominal MI is used together with a noun which is not formerly feminine, the possessive is always accompanied by the definite suffix -a on the preceding noun, indicating that the presence of the -a suffix in itself conditions a phonological context in which MI can occur, not the gender of the noun. In accordance with Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021), we found no occurrences of the combinations -a MIN or -en MI, which strengthens the assumption of a close relationship between the noun’s phonological ending and the form of the postnominal possessive. We also did not find any occurrences of -et MI or -en MI. Thus, our data support Svenonius’s (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) allomorphy analysis.

6.5 A two-gender system

The data from Oslo reveal a two-gender system where masculine and feminine have merged into common gender. The exponents for common gender are the same as for masculine gender in a three-gender system. Furthermore, common gender has two declension classes: All common nouns allow for the definite suffix -en, while only formerly feminine nouns also allow for -a and -a MI. However, young speakers in Oslo seem to have certain difficulties in determining which nouns allow -a (and -a MI). As feminine gender is absent in their mental grammar and the indefinite article ei probably rarely occurs in their input, they lack a systematic mapping between individual nouns and the definite suffixes -a and -en.Footnote 14 Thus, it is not surprising to occasionally find -a and -a MI on formerly masculine nouns, as they are now categorized as common gender, and common gender allows for two declensional classes.

The language-internal factors syncretism, frequency, and acquisition have been used to explain the change from a three- to a two-gender system in Norwegian, and it has also been invoked to account for the discrepancy between ei and -a. These factors can probably explain the observed difference in the use of -a and -a MI in Oslo versus Trondheim and Tromsø.

Since adults in Tromsø maintain a three-gender system (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021), and definite suffixes are acquired early in Norwegian (Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013), we assume that the link between formerly feminine nouns and the definite suffix -a is robust in the input of young speakers of the Tromsø dialect. Thus, the change (so far) only concerns grammatical gender. In Oslo, on the other hand, a two-gender system allowing for the definite suffix -en on traditional feminine nouns has existed for years, and low type frequency of the feminine indefinite article ei has been well documented (Opsahl & Nistov Reference Opsahl, Nistov, Pia and Bente Ailin2010, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011a, Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018). The young speakers in our study have undoubtedly encountered less input, not only of ei and prenominal MI, but also of the definite suffix -a and -a MI. When exposed to a system with optionality between -a and -en for formerly feminine nouns, the link between the -a suffix and these nouns weakens. The optionality in the system is underlined by the fact that the majority of participants use both -en and -a with these nouns.

In a two-gender system, where the previously existing systematic mapping determining the distribution of the definite suffix -a is missing, it is less surprising that -a and -a MI also appear on formerly masculine nouns. The fact that this mainly occurs on disyllabic nouns ending in -e might be a result of the speakers trying to create a system for the distribution of -a and -en. Disyllabic nouns ending in -e have been argued to be a cue for feminine gender (Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001), even though recent studies on nonce words have shown that the contemporary predictive power of this tendency is weak (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012, Urek et al. Reference Urek, Lohndal and Westergaard2022). Fretheim (Reference Fretheim, Ernst Hakon and Ove1985:101) argues that the definite suffix -a on the masculine nouns bamse (‘teddy bear’) and kjele (‘boiler’), found in child L1 acquisition of Norwegian, shows that the children have discovered that nouns ending in -e tend to have the definite suffix -a. Haug (Reference Haug2019:61) reveals the same pattern in the NoTa corpus; nouns ending in -e were the formal factor that most clearly predicted the use of the definite suffix -a. Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011a:125f) did not find any occurrences of masculine nouns with -a in the NoTa corpus, but based on his own intuition and experience, he mentions that the following nouns, which are usually masculine in three-gender dialects, can occur with the -a suffix: kubbe (‘log of wood’), bakke (‘hill’), hage (‘garden’), planke (‘plank’), børste (‘brush’), pinne (‘stick’), and type (‘type’). As young speakers in Oslo do not have feminine gender, one might speculate that they treat the -e ending as a cue for declension class, i.e. the definite suffix -a.Footnote 15 The use of -a and -a MI on the masculine noun mark ‘earthworm’ might be explained by the fact that there is a homonym in Norwegian meaning ‘field’, which is traditionally feminine and often produced with an -a ending in the definite singular. According to the encyclopaedia Store norske leksikon,Footnote 16 the name Oslomarka has been used as the collective name for the contiguous areas of forest and open fields around Oslo and Oslo’s neighbouring municipalities since the 1930s. In the Oslo context, Oslomarka is often referred to only as Marka, and the use of -a and -a MI on mark can thus stem from this use. However, this does not explain the occurrence of the -a suffix on frosk ‘frog’.

Summarizing, the loss of feminine gender forms and corresponding declension class markers develops gradually across Norwegian varieties. In a cross-dialectal study, van Baal et al. (Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024) refer to a ‘cline’, ranging from a full three-gender system to a full two-gender system. We see that feminine gender disappears first, and then the declension class forms associated with formerly feminine nouns start eroding due to the lack of a clear systematic mapping that determines the distribution of the definite suffix -a. In Oslo this process seems to have started earlier in the western part than in the eastern part of the city. Because of the spread of upper middle-class speech in Oslo, a two-gender system with neuter and common co-existed with a three-gender system in the nineteenth century, and this two-gender system has gradually expanded at the expense of the three-gender system. Importantly, we now see that the declensional classes are also affected, which has recently also been attested for Stavanger (van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024).

7. Summary and conclusion

We have investigated the use of grammatical gender in a population of 12-year-olds in Oslo, Norway, using experimental methods. Previous studies have documented an ongoing change involving the loss of feminine gender in different dialects in Norway. Our findings clearly show that feminine gender no longer exists in the grammar of 12-year-olds speaking the Oslo dialect, neither in the western nor eastern parts of the city, as we find no occurrences of indefinite article ei and prenominal possessive MI in our data. The most striking difference between Oslo on the one hand and Tromsø and Trondheim on the other, is the difference in use of the definite suffix -a and postnominal possessive -a MI with formerly feminine nouns, which are less frequently used among the 12-year-olds in Oslo. We argue that the erosion of -a and -a MI is due to the lack of a systematic mapping which determines the distribution of the definite suffixes -a and -en of the new common gender. In Oslo this process seems to have started earlier in the western part than in the eastern part, which we argue is due to the spread of upper middle-class speech in Oslo. The -a suffix is still maintained in Tromsø because the change into a two-gender system is more recent (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015), while the incipient change reported in Trondheim (Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019) may be due to the change having started earlier than in Tromsø. However, the reduction in the gender system does not seem to necessarily lead to changes in the declension class system, as this has apparently not taken place in contact dialects of Norwegian (Conzett et al. Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011).

Our data show that the change in the gender system only affects feminine gender, not neuter, and we found no indications that syllabic structure (mono- vs. di- or polysyllabic) on neuter nouns makes the nouns more or less likely to occur with traditionally masculine gender.

Our finding of a similarity between ei and prenominal MI on the one hand, and -a and postnominal MI on the other, is consistent with previous findings (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015, Reference Rodina and Westergaard2021, Busterud et al. Reference Busterud, Lohndal, Rodina and Westergaard2019, Busterud & Lohndal Reference Busterud and Lohndal2022, van Baal et al. Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2023, Reference Yvonne van, Hedda, Ragnhild and Terje2024, Solbakken et al. Reference Solbakken, Eik, van Baal and Lohndal2024) and supports the claim that definite suffixes are not exponents of gender. Instead, the definite suffixes -a and -en are declension class markers associated with common gender. Our findings are also in line with Svenonius’s (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) claim that the postnominal possessive MI does not express feminine gender in two-gender dialects. Instead, this form is an allomorph of the common gender form MIN, which is conditioned by the morphophonological form of the definite suffix of the immediately preceding noun. Thus, MI and MIN are postnominal possessives associated with common gender, conditioned by the choice of definite suffix on the preceding noun (-a vs. -en). The reason why we see a complete correspondence between the use of -a and postnominal MI is that postnominal MI is licensed by the use of the definite suffix -a. Thus, if in the future the definite suffix -a disappears from the dialect, postnominal MI is also predicted to disappear. Ei and prenominal MI are indisputable exponents of feminine gender and no longer exist in the two-gender dialect with common and neuter. Occasional findings of formerly masculine nouns with -a and -a MI indicate that the 12-year-olds do not have problems with gender per se, but that there is a certain competition between the two declension classes associated with common gender. We speculate that the 12-year-olds in Oslo treat the -e ending on common nouns as a cue for the declension class marker -a. Furthermore, these data indicate that the presence of the -a suffix conditions a phonological context in which MI can occur regardless of the former gender of the noun being masculine, supporting Svenonius’s (Reference Svenonius, Gribanova and Shih2017) analysis of the postnominal possessive MI as an allomorph of the common gender form MIN.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the three reviewers for detailed comments and useful suggestions. We would also like to thank the research assistants Nora Abdeladim and Maria Gulliksen for their help in collecting and transcribing the data. This research was part of the MultiGender project at Centre for advanced study (CAS), 2019–2020, and the GenVAC project funded by the Research Council of Norway (grant number 301094).

Appendix

Table A1. List of stimuli used in Experiments 1 and 2