Non-technical Summary

Despite broad public interest, intellectual vitality, and evolving technology, paleontology as a discipline is threatened by a steady decline in the number of available permanent academic positions for early-career scientists. Using the best available data, we have assessed recent trends and current status of the supply of new paleontology doctorates and the number of available positions. Overall, employment trends are downward, although the production of early-career scientists has remained steady; it is highly unlikely that many of these young scientists will find permanent employment in academic paleontology. There has also been a steady decline in the number of regular members of professional societies, portending a long-term threat to their viability. Proactive steps need to be taken now, by both these societies and individual paleontologists, to address this existential issue.

Introduction

Paleontology today is as dynamic and intellectually vital as ever in its history. Recent years have seen a constant stream of new discoveries, the application of new and innovative technologies, and approaches establishing clear relevance to current global environmental issues. Public interest, media attention, and enrollment in paleontology-themed undergraduate courses remain high. The vitality of the field is mirrored by the energy and involvement of students and early-career professionals. At the same time, there is a growing perception (and visible frustration) among these same early-career members that academic job prospects in paleontology are dismal and perhaps getting worse.

As a result, in December 2021, the Paleontological Society (PS) formed an ad hoc committee on employment charged with assessing the current status of employment in paleontology and making recommendations for actions to enhance employment opportunities in academia and more broadly for early-career members. The committee membership, the authors of this article, was composed of paleontologists across a range of career stages.

In early 2022, the committee distributed an informal survey, the PS Employment Ideas Bank, with the goal of gathering perceptions on the status of employment in paleontology. A second notice was sent via Priscum in early 2023. We received a total of 250 responses from the members of the PS, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP), and the Cushman Society for Foraminiferal Research. When asked “In your opinion, what is/are the primary issue(s) or concern(s) regarding the state of the current job market for paleontologists?,” the majority indicated simply that the concern was a lack of jobs. Others indicated an issue was a lack of understanding of paleontology by those outside the field, especially its interdisciplinary nature, and that this lack can be a hindrance to jobs outside academia. Lack of funding was also brought up, both as a direct source of employment, such as postdoctoral and museum positions, and due to the perceived financial returns to a department/university in the form of grant overhead for hiring a paleontologist as opposed to a scientist in a different subdiscipline (because of the difficulty in obtaining National Science Foundation funding for paleontological research). These answers indicated a critical need to gather accurate information on these topics.

Understanding the state of the field from an employment perspective is a daunting task, given the lack of a comprehensive centralized data source. Earlier studies of employment in paleontology have been relatively limited in scope. Farley and Armentrout (Reference Farley and Armentrout2000) described a 90% decrease in paleontologists at major oil companies, long a mainstay of paleontology jobs for all degree levels. The brief overview by Flessa and Smith (Reference Flessa and Smith1997) focused exclusively on employment in academia in the United States. Using the Directory of Geoscience Departments published by the American Geological Institute (AGI; currently the American Geosciences Institute), they counted the number of paleontologists in 564 academic departments listed in both 1980 and 1995 and found the total number stable at about 480. They omitted emeritus, adjunct, and research faculty. About half the departments had no paleontologists and 34% had only one. One note of concern was that, in contrast with geophysicists and geochemists, there was a sharp decline in the number of assistant professors, indicating diminished recruitment at lower ranks.

Plotnick (Reference Plotnick2008) likewise used downloaded employment data from the AGI directory for 2007 to produce a self-admitted “somewhat fuzzy” snapshot of U.S. paleontology. He found the total number of tenure-track faculty and lecturers to be much higher than Flessa and Smith’s (Reference Flessa and Smith1997) count: about 615; but he included more departments in his count. Similar to Flessa and Smith’s (Reference Flessa and Smith1997) data, 44% of paleontologists were the sole representative of their discipline. Based on membership rolls of the PS and the SVP, Plotnick (Reference Plotnick2008) estimated that there were on the order of 100 professional paleontologists in departments not included in the AGI database.

Here, we summarize our efforts to get a sharper picture of the current status and trends in employment of paleontologists and summarize potential actions that the field and its representative professional societies can take. The goal is to help address “the critical question of whether young scientists have accurate information and counseling about future career prospects. Ideally, an informed decision…should be based on reliable employment information” (Levitt Reference Levitt2010: p. 2). The resulting data are admittedly incomplete and biased toward U.S. students and institutions and the Earth sciences. For a perspective from the United Kingdom, we recommend an essay by Butler and Maidment (Reference Butler and Maidment2019) in the Palaeontological Association’s Palaeontology Newsletter, who also stressed that “starting PhDs should receive realistic information on career prospects in academia and be made aware of alternative career paths” (p. 46).

Data: Scope, Limitations, and Reliability

There are currently no organizations that explicitly report employment statistics in paleontology, either the number of employed scientists or the number of job offerings. For this reason, there are very significant difficulties in accurately tracking changes in employment over time. The most comprehensive available data source is the AGI Directory of Geoscience Departments, currently in its 58th edition (Keane Reference Keane2023). The directory contains information on thousands of departments, including academic institutions, museums, and state surveys. Most are from the United States, but many departments outside the United States are included. Individual faculty members are associated with codes that indicate their research or teaching specialty. The directory also contains summary numbers for each code. We have worked directly with AGI to get current and historical counts for paleontology-specific codes.

Using the AGI data presents a number of challenges. First, before 2010, each faculty member was associated with a single code. AGI then changed its method to allow multiple specialties to be listed, causing an apparent increase in the numbers of individuals in all disciplines in the directory. Those who list “paleontology” as their second, third, etc., specialty are thus now counted in the total paleontology numbers. For example, the 2007 directory gave 1223 total paleontologists, whereas the 2019 edition gave the number as 1593. Second, AGI has also changed its subdiscipline definitions and codes, further complicating direct inter-year comparisons by subdiscipline. The 2008 directory had codes for “Paleobiology” and “Paleoecology and Paleoclimatology,” whereas the 2019 edition lacks the former code and splits the latter into separate categories; “Geobiology” is also renamed “Geomicrobiology.” Third, it is uncertain how many paleoclimatologists and geomicrobiologists would consider themselves paleontologists. Finally, the directories explicitly cover only geoscience departments; paleontologists outside those entities (in biological sciences departments, for example) would not be included. Coverage of non-U.S. entities is limited. Despite these issues, the AGI remains the single best source of data; we are not aware of similar coverage for the biological sciences.

To supplement the AGI data, we examined membership trends in professional societies, including the PS, SVP, Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM; formerly the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists), the Geological Society of America (GSA), the Palaeontological Association (PalAss), and the Paläontologische Gesellschaft (PG). The number of “regular” or “professional” member categories was presumed to include members who are currently making a full-time living in paleontology and is thus a rough underestimate of overall employment in the field. As a measure of potential demand for positions, we also tabulated the number of individuals in “student” and “early career” categories. It should be noted that these categories may not align among societies and that some have changed over time; for example, the SVP had 9 member categories in 2012 and 20 in 2023, whereas the PG separates doctoral and non-doctoral students.

We used publicly available data from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to determine the number of doctorates granted in paleontology by American universities. “Paleontology” is a subset of “Geological Sciences” and thus does not include paleontology-themed doctorates granted outside the geosciences. NSF data were also used to estimate funding levels for paleontological research and postdoctoral fellows, major factors in hiring and retention. We focused on the now archived Sedimentary Geology and Paleobiology (SGP) Program, recently renamed as “Life and Environments Through Time”, the major entity with dedicated paleontology grants, while recognizing that projects with paleontology as the major focus or an important component may be funded elsewhere within NSF. We also considered data on funding in Canada and Europe, although direct comparisons are difficult.

Our data compilations and analyses are biased toward permanent academic positions, that is, research (including museum curators) and/or teaching faculty. We focused on these positions because current academic graduate programs in the United States are geared primarily toward training graduates for academic careers. We acknowledge that students of paleontology may choose other careers in the field such as collections management, specimen preparation and conservation, science education and conservation, primary and secondary school teaching, and professional mitigation paleontology. We argue, however, that most current graduate programs do not emphasize training in these aspects of the field and that skills for these professions are often gained through apprenticeships, internships, or volunteer work experience. We also believe that most graduate students who enter doctoral programs in the field have a goal of entering the academic job market and are thus trained as future researchers and teachers.

The number of paleontology-oriented positions available each year was estimated from a range of online data sources that job applicants might search (see “Where Do Paleontologists Look for Jobs and How Many Jobs Are There?” and Supplementary Materials). These vary widely in scope and relevance. There is currently no single clearinghouse for positions in the field, which complicates the task of gathering accurate data on employment opportunities and how those opportunities are realized (or not) over time.

Finally, we conducted two informal surveys of the membership of the PS, the SVP, and the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research. These were not scientific surveys but were meant to obtain anecdotal information on employment of recent Ph.D.s and perceptions of the current job market: primary concerns regarding the state of the current job market; initiatives from the PS that would benefit job searches; and ways in which the PS can better serve early-career members.

How Many Paleontologists Are There?

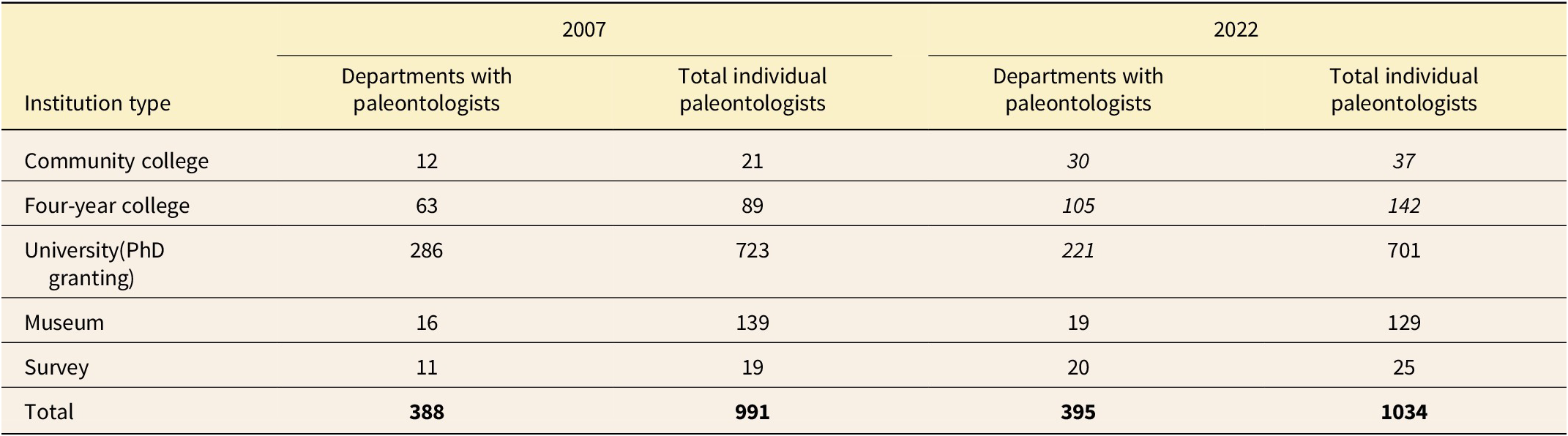

The biggest challenge in compiling a dataset of accurate numbers of paleontologists is that paleontologists are employed in a variety of academic departments, and no single compilation currently exists. We used a variety of approaches to estimate trends in the number of working paleontologists. Using AGI data, we examined trends in academic employment in paleontology in Earth science department in the United States from 2007 to 2022. As mentioned earlier, how AGI reports disciplines and subdisciplines has changed over time. On face (Table 1), there has been little change in the overall job numbers in American higher education (but see “Where Do Paleontologists Look for Jobs and How Many Jobs Are There?”). However, we did note a shift in where paleontologists are employed in geoscience. There is a notable drop (by 23%) in university (graduate degree–granting) departments with paleontologists, while the number in 4-year colleges (without graduate programs) and community colleges has increased (by 80%). This suggests a major shift from research to teaching emphasis in the field and a decline in the number of programs producing new academic paleontologists.

Table 1. Distribution of paleontologists among U.S. institution types in 2007 and 2022. Values in 2022 showing a notable change between the two years are in italics. Totals are in bold. Data from the American Geosciences Institute (see text)

We also compared changes in the distribution of academic rank among those who give their primary specialty as paleontology (Table 2). The numbers of emeritus, full, and associate professors have all increased, whereas the number of assistant professors has declined, suggesting those of more senior ranks are not being replaced. In contrast, the number of low-paid non–tenure track appointments has more than doubled. This is in keeping with the national trend within academia: “Non-tenure-track positions of all types now account for over 70 percent of all instructional staff appointments in American higher education” (Times Editorial Board 2024). Because non–tenure track faculty generally are hired only to teach, this is further evidence of a shift away from research in academic paleontology.

Table 2. Shifts in academic rank distributions of U.S. faculty with primary specialization as paleontology from 2007 to 2022, based on data from the American Geosciences Institute. Values in 2022 showing a notable change between the two years are in italics

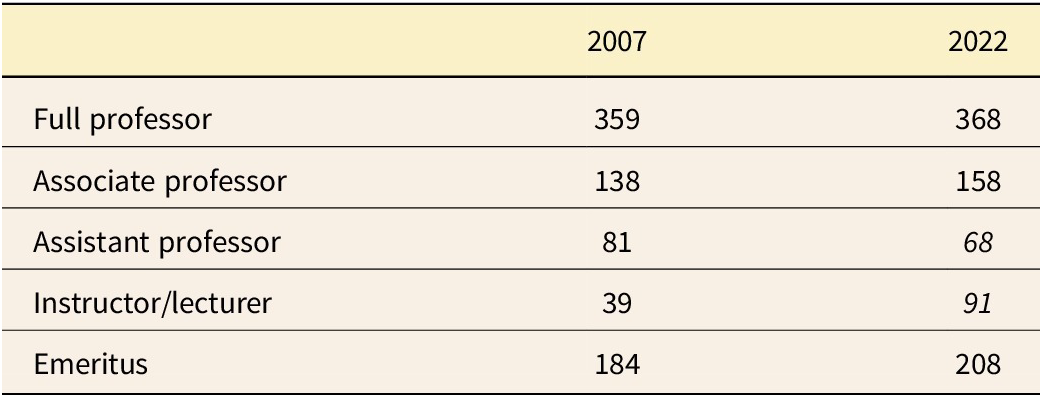

Composite data, globally and from all institutions, from eight distinct years (from 2007 to 2023) were obtained directly from AGI (Fig. 1A). First specialty numbers record those who indicated paleontology, in any subdiscipline, as their primary specialty in the Earth sciences. These worldwide numbers have increased very slightly over the years, by about 4%. Second specialty numbers record those who indicated paleontology as their secondary specialty (unique) and did not list paleontology as their primary specialty. The overall numbers since 2015 are largely stable. This may be partly attributable to the growth of or increased data on paleontologists outside Europe and North America, especially China. However, paleontologists represent a decreasing percentage of the total global Earth science community, particularly since 1994: 8.80% in 1994; 8.27% in 1996; 8.52% in 2003; 7.21% in 2007; 7.23% in 2012; and 6.84% in 2019.

Figure 1. Data on those reporting paleontology as primary or secondary specialty. A, Global and B, U.S.-only reports. Data courtesy of American Geosciences Institute (AGI).

AGI data also recorded the number of faculty in U.S.-only institutions who indicated paleontology as their primary or secondary specialty (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the global figures, those faculty indicating paleontology as their primary specialty decreased considerably by 12.8%. The decline of those who indicate paleontology as a first specialty is only partly balanced by those who list it as second. These may be stratigraphers, sedimentologists, and geobiologists who teach paleontology but may not (primarily) engage in paleontological research. It is currently impossible to determine this at a finer scale of analysis. Nevertheless, these numbers suggest a decline of American paleontology within geoscience departments as compared to that in other countries.

Using the AGI directory, we determined the number of paleontologists in different subdisciplines in 2007 and 2019 in the Big Ten and the Ivy League universities. From 2007 to 2019, the total number of geoscience paleontologists in the Ivy League declined from 18 to 16, while for “invertebrate paleontology” (as defined by Brandt and Smrecak Reference Brandt and Smrecak2016) the number decreased from 9 to 8. However, based on these institutions’ webpages (as of December 2023), those numbers are now 11 and 6, respectively. Brown and Dartmouth no longer have any paleontologists in their geoscience departments (although there may be some elsewhere in the university). For the Big Ten, there was relatively little change from 2007 to 2019, but based on their websites, a sharp decline has again occurred in 2023, with a more than 50% decline in “invertebrate paleontology” (from 30 to 13).

We should also note the closing of a number of Earth science departments, a major source of concern. These are often accompanied by loss of positions, including of tenured faculty. We are aware of recent closings or threatened closings of departments at Western Illinois University, North Dakota State University, University of Vermont, and Purdue Fort Wayne. There are also major budget cuts underway or anticipated at the University of Connecticut, the University of Arizona, and West Virginia University, as well as at the California Academy of Sciences and the Paleontological Research Institution. Outside the United States, wholesale reductions of curatorial staff, including paleontologists, are currently threatened at Macquarie University, the National Museum Wales, U.K., and the South Australian Museum, whereas the entire science community in Argentina is under threat due to rampant inflation and government cuts (Ambrosio and Koop Reference Ambrosio and Koop2024).

Overall, the available data for American geoscience departments highlight the dismaying situation that current graduates and early-career paleontologists who wish to enter academia and become paleontological professionals face. This decline of paleontology in the geosciences parallels a long-term trend in the drop of natural history instruction in biology departments (Tewksbury et al. Reference Tewksbury, Anderson, Bakker, Billo, Dunwiddie and Groom2014), which we suspect impacts biologically oriented paleontologists. This includes the devaluing of taxonomy and loss of positions for taxonomic specialists (Wägele et al. Reference Wägele, Klussmann-Kolb, Kuhlmann, Haszprunar, Lindberg, Koch and Wägele2011; Engel et al. Reference Engel, Ceríaco, Daniel, Dellapé, Löbl, Marinov and Zacharie2021). Also, as is the case for paleontology, those outside the disciplines of natural history have been slow to recognize the tremendous technical and theoretical advances that have transformed these fields (Tosa et al. Reference Tosa, Dziedzic, Appel, Urbina, Massey, Ruprecht and Eriksson2021).

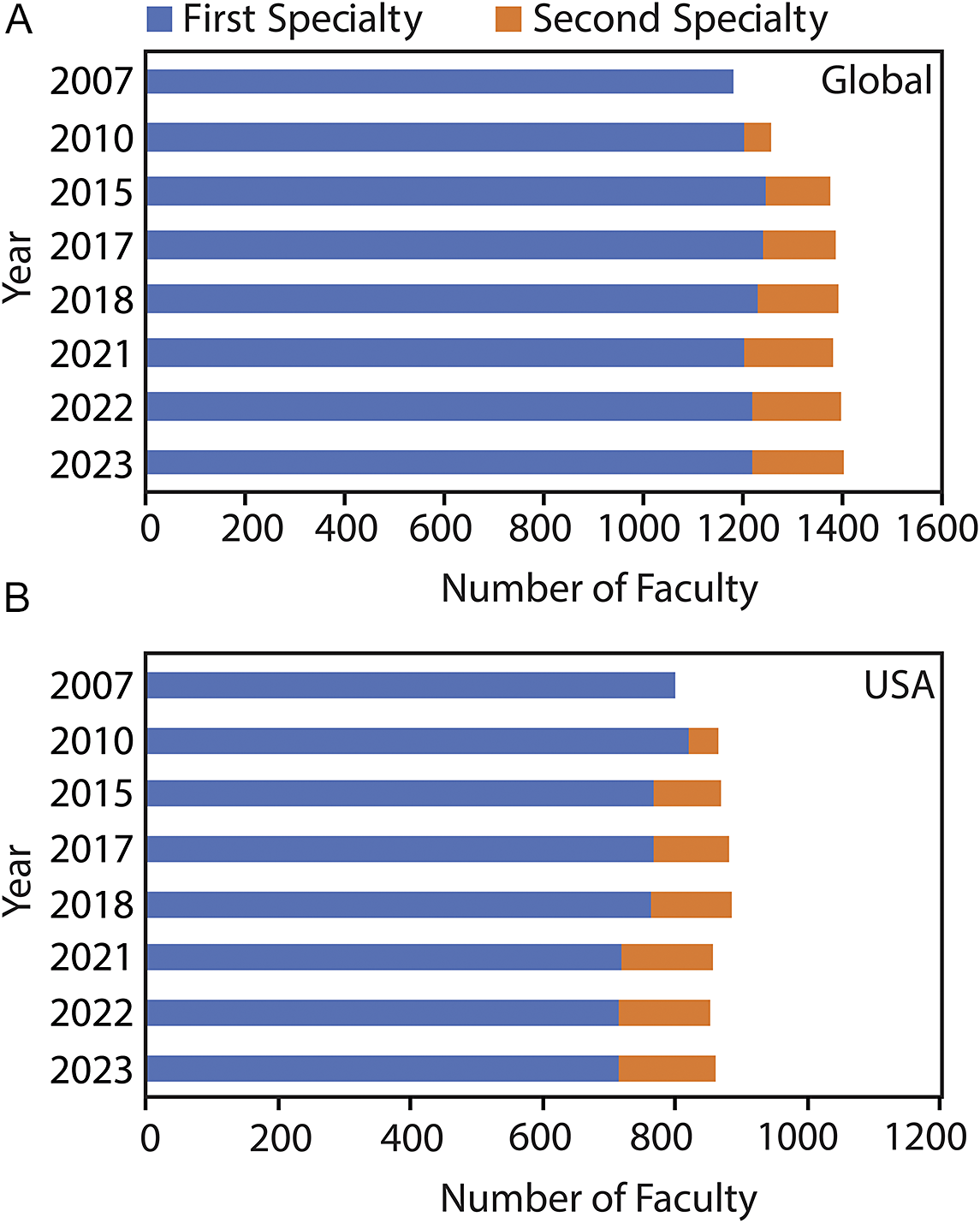

Membership in professional societies, in particular in “regular” or “professional” member categories, which is presumed to include mainly members who are currently making a full-time living in paleontology, is an approximate measure of overall employment in the field. Figure 2A shows recent trends in membership in the PS. Although total membership has been relatively constant, this pattern has been driven mostly by an increase in student/early-career members. Regular members have declined from 944 to 661 (by 30%) during this period. A similar trend has been seen by SEPM, whose total membership has declined from 3414 in 2012 to 1903 in 2022, with most of the decline driven by a 42% decrease in professional members (Fig. 2B; H Harper personal communication 2024). SVP membership (Fig. 2C) shows a similar trend, with a 23% decline from a total membership of 2532 (1868 non-student) in 2007 (Plotnick Reference Plotnick2008). Even more alarming is the trend for the GSA (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Total membership has declined by nearly 30% since 2010, with professional member numbers dropping by 52% and student members by 37%. Of all GSA members, 10% currently identify their professional interest as “Paleo sciences” (before 2014, these were paleobotany, paleontology, paleoecology, and paleoclimatology/paleoceanography); this number has declined 16% since 2010. These trends mirror, and perhaps are related to, the overall decline in U.S. geoscience enrollment at both undergraduate and graduate levels in recent years (Keane Reference Keane2022). Another potential factor in membership decline is the growth of open access society journals, which reduces what was once a major incentive to join professional societies. Increasing membership fees are likely also a factor.

Figure 2. Trends in membership of paleontological professional societies in different membership categories. A, Paleontological Society (PS) membership; B, Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM) membership; C, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) membership.

The two European societies examined also show comparable trends. The number of “ordinary” members of the PalAss has declined 22% since 2012 and that of full members of the PG is down 11% since 2015 (Supplementary Fig. S1B,C). Overall, these trends are worrying for the continued health of our professional societies.

How Many Paleontologists Are Looking for Employment?

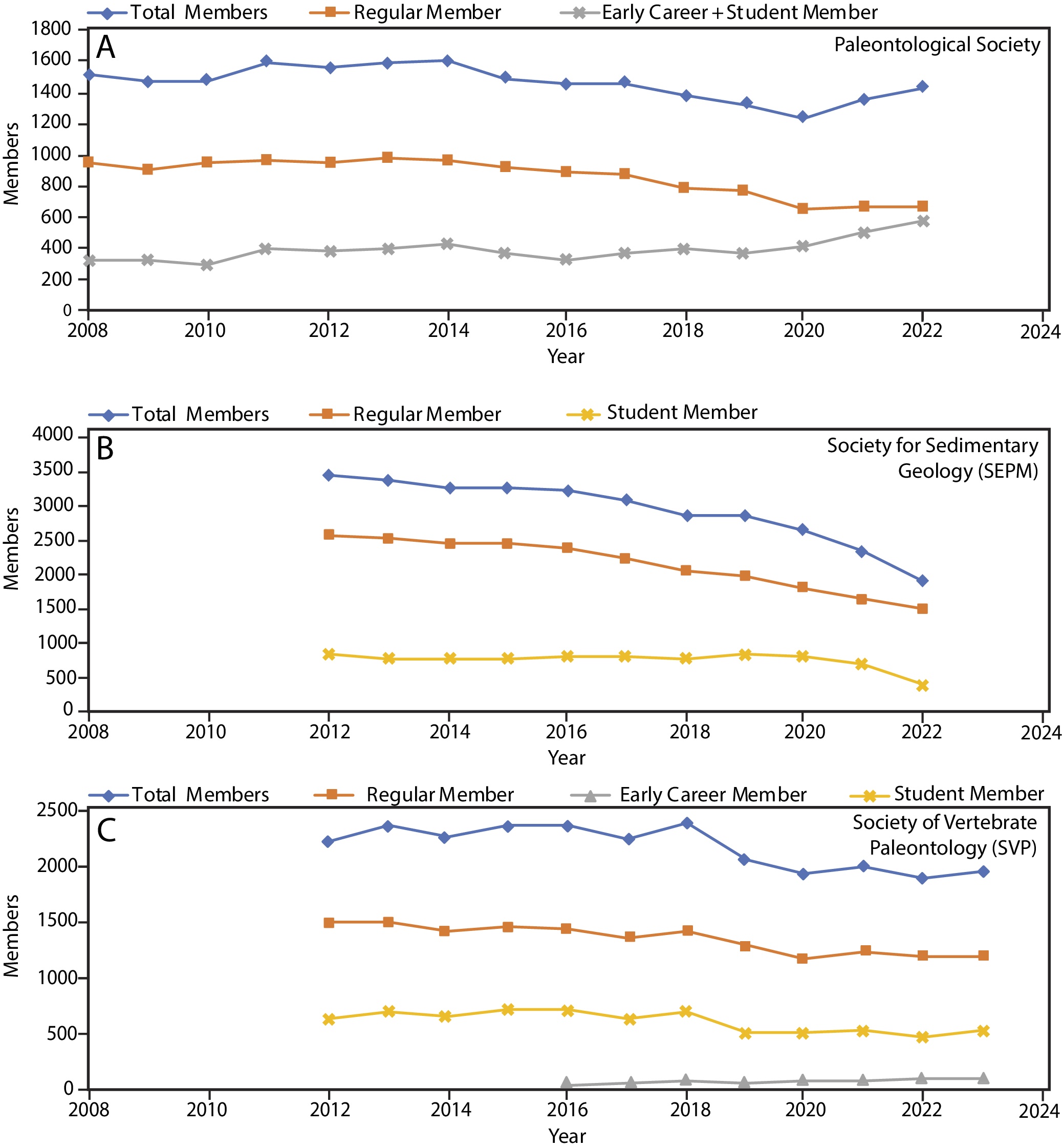

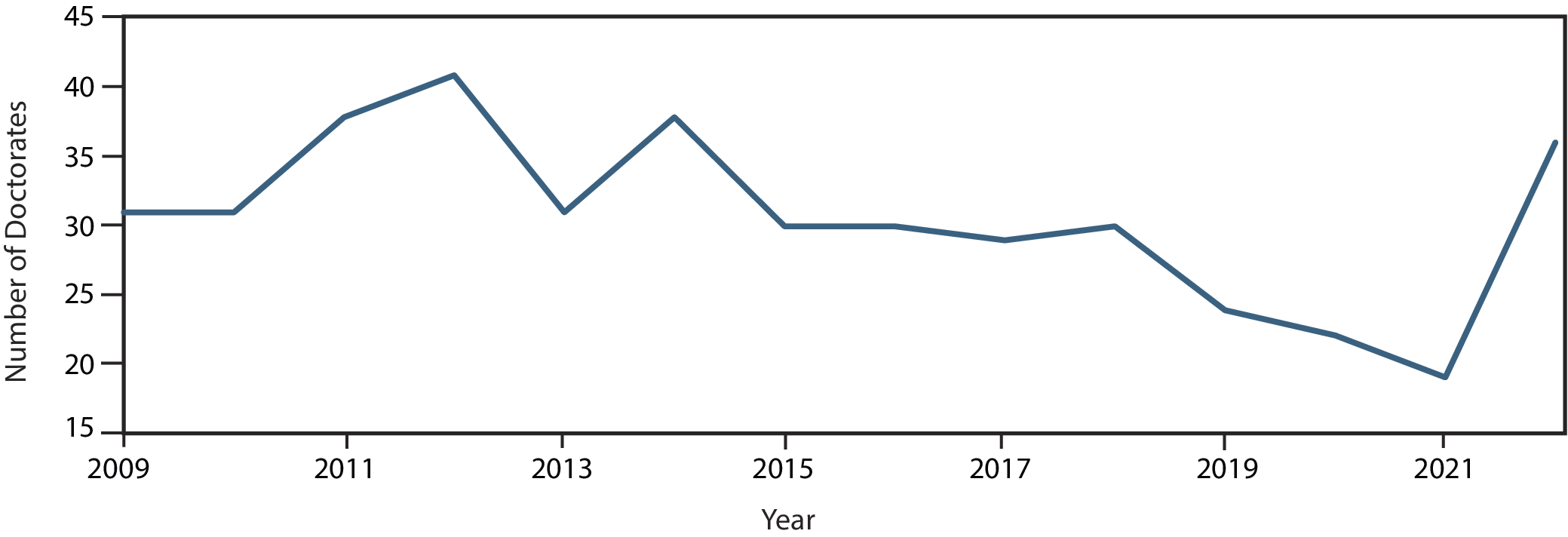

Based on NSF data (Fig. 3), an average of 31 geological science doctorates in paleontology were issued annually in the United States between 2009 and 2022. There was marked decline in 2019–2021, the latter years perhaps due to COVID-19 related delays in degree completion, followed by a rebound in 2022.This is roughly 6.4% of all geological science Ph.D.s. Paleontology degrees within the biological sciences are not tabulated separately; there are about 215 degrees per year in evolutionary biology, which likely include some paleontology-focused theses. We assume that students earning doctoral degrees have the primary goal of attaining an academic position, and therefore, we also assume that training provided in doctoral programs is geared largely toward academic positions.

Figure 3. Paleontology doctorates in the United States (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics 2022). Data for 2022 courtesy of RTI International (https://www.rti.org/) on behalf of the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics.

The number of student and early-career members in professional societies is another indicator of paleontologists seeking employment. From 2008 to 2022, the number of “early career/student” members of the PS increased from 317 to 568 and now makes up 40% of the total membership (Fig. 2A), which is the highest percentage among a group of professional biological societies recently surveyed by the American Society of Mammalogists (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Arbogast, Colella, Goheen, Green and Enrique Lessa2023). SEPM (Fig. 2B) and the GSA (Supplementary Fig. S1A) both have about 25–30% student members, although these numbers include mostly non-paleontologists. Students and early-career members make up 32% (624) of the membership of the SVP (Fig. 2C); this percentage has remained relatively steady, although the number has dropped in parallel with the overall membership decline. Thirty-one percent (323) of the PalAss members are students (an increase from 24% [268] in 2012), and 12% (90) of the PG. It can be assumed that most of these individuals are now or will soon be in the job market, although we admit that not all of these may have the goal of attaining an academic position. The increase in the number of early-career scientists may be partly driven by those in multiple successive postdoctoral positions.

The Unemployed/Underemployed Paleontologist Support Group on Facebook has 2400 members (as of August 2024). It is unclear how many of these are currently looking for work in the field; some members of the group are looking for jobs for their students, while others who may have secured permanent academic employment might not have exited the group. The group also includes non-academics and those who lack doctorates looking for jobs as preparators, museum educators, and so on.

Where Do Paleontologists Look for Jobs and How Many Jobs Are There?

In past years, paleontologists looking for employment would examine published ads in journals such as Geotimes or interview at the employment booths set up at the GSA annual meeting or the SVP meetings. These venues have more or less disappeared, to be replaced by a wide range of online resources. Online listings can be divided into those that cover all available jobs in higher education, which often list very few paleontology vacancies, or a variety of discipline-specific sites, which can include non-academic positions.

Sites that list all jobs in higher education include:

-

• HigherEdJobs: https://www.higheredjobs.com (This site can be particularly useful.)

-

• The Chronicle of Higher Education: https://jobs.chronicle.com/

-

• American Association for the Advancement of Science job Board: https://jobs.sciencecareers.org/jobs/

-

• Nature Careers

Paleontology and geology discipline-specific sites include:

-

• GSA Career Hub: https://careers.geosociety.org/ (Many of the jobs listed here also appear on the higher education sites.)

-

• PaleoNet Pages: https://paleonet.org/page-2/

-

• Earth Science Women’s Network (ESWN) Earth and Environmental Science Jobs List: https://eswnonline.org/online/earth-and-environmental-science-jobs/ (This is a crowd-sourced list that also archives older lists.)

-

• EcoEvoJobs: ecoevojobs.net (This is a crowd-sourced list of academic positions in ecology and evolutionary biology compiled every academic year that often includes paleontology, or adjacent positions. Archives from past years are searchable.)

-

• Association for Women Geoscientists: https://www.awg.org/page/CareerOpportunities

-

• Unemployed/Underemployed Paleontologist Support Group on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/PaleoJobs

-

• Paleobotany jobs: Employment ads are placed on the International Organisation of Palaeobotany home page. Members of the Palaeobotanical Section of the Botanical Society of America get notices of new positions from the Secretary Treasurer of the Section.

-

• Earthworks-Jobs.com: https://www.earthworks-jobs.com/ (This site lists positions in academia and industry, as well as graduate school advertisements.)

-

• Museum Jobs.com: https://www.museumjobs.com/ (This site includes positions almost exclusively in the United Kingdom.)

-

• American Geophysical Union: https://findajob.agu.org/jobs/

-

• European Geophysical Union: https://www.egu.eu/jobs/

-

• European Association of Geochemistry: https://www.eag.eu.com/jobs/

-

• Other country-specific higher education job boards

A survey of job postings to the PaleoNet Listserv from 2020 to 2023 (excluding student and postdoctoral positions) shows a general trend of recovery in open positions for paleontologists since the COVID-19 pandemic, but never exceeding 24 positions open in 1 year in total (Supplementary Figure Fig. S3). The majority of job postings were specifically for paleontology, paleontology subdisciplines, or closely related fields such as evolutionary biology, while others were positions that a paleontologist may qualify for (e.g., sedimentary geology). Over the 4 years of surveyed job opening announcements, a total of 78 positions were posted, with 16 of those positions being tenure-track faculty in paleontology or museum curator positions. The year 2021 saw the most tenure-track faculty in paleontology or museum curator positions open, at eight, and included vacancies in the United States and internationally; see Supplementary Materials, Summary of PaleoNet Listserv Job Postings (2020–2023). Twenty-nine permanent, full-time faculty (tenure track and non-tenure track) and museum positions (collections managers and curators) in paleontology specifically were announced on PaleoNet between 2020 and 2023.

Based primarily on the Earth and Environmental Science jobs database supplemented with additional jobs known to committee members from 2019 to 2022, there are on average seven to nine permanent paleontology-specific jobs advertised per year, and at least seven paleontology searches failed or were subject to hiring freezes in the past 4 years. Notably, this contains, but undersamples, European positions and includes some positions advertised as hiring ranks above assistant professor. The COVID-19 pandemic certainly influenced hiring patterns and may have disproportionately impacted the cohort completing postdocs/Ph.D.s around 2021, as indicated by the number of searches that were withdrawn due to hiring freezes or that did not result in a hire.

Increased competition in academia overall (especially through the loss of faculty positions) is coming at a time when diversity in graduating paleontologists is only just beginning to shift (marginally) toward reflecting the diversity of the broader community. Losing a cohort of talented individuals from diverse backgrounds because of the timing of their graduation and/or completion of postdocs is likely to have larger long-term consequences for efforts to improve diversity in the field (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Johnson and Schroeter2022). Heightened legitimate concerns about healthcare access, safety, and human rights for persons who have the capacity for pregnancy and LGBTQ+ individuals limit the number of locations in which people may choose to (or can) live, further increasing competition for jobs in places perceived as safe (Langin Reference Langin2023a; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Anderson, McLaughlin, Collins and Boys2023; Aghi et al. Reference Aghi, Anderson, Castellano, Cunningham, Delano, Dickinson and von Diezmann2024). Programs like postdoc-to-hire cohorts across university departments may be a means to address some of these issues, but notably these programs are rare and frequently only accept very recent graduates.

Are Recent Ph.D.s in Paleontology Achieving Employment in Higher Education?

An informal survey sent to PS members in 2022 focused on the current employment status of recent Ph.D. students in paleontology. We requested responses from faculty who advised doctoral students from 2012 to 2022 with the goal of trying to understand the success rate of paleontology graduates with doctorates in finding permanent academic positions. Information solicited was:

-

• The year a student entered and exited the degree program.

-

• If the student graduated with a Ph.D. degree from the program.

-

• The employment status of the student within 1 year of exiting the degree program. Was the student employed in the field of paleontology (or a closely related field) at the time?

-

• If known, does the student identify as a member of a group presently underrepresented in the geosciences (woman, underrepresented ethnic or racial group, LGBTQ+, etc.).

-

• What subdiscipline(s) was/were part of the student’s dissertation work?

We received responses from 45 advisors concerning 129 students from 2006 to 2022. Advisors were asked to report on all students who graduated from their programs in the last decade, regardless of subsequent employment status, in an effort to curb bias in the results from potential underreporting of students who left academia. Overall, 88% of graduates are employed 1 year after exiting the Ph.D. program. Of the employed graduates, 90% are employed in academia in paleontology or a closely related field 1 year after exiting the program, with the majority of these graduates in postdoctoral positions. We note that 45 faculty is a small sample size, and respondents likely skew toward those whose students were successful in finding employment in academia. A detailed summary of the key results is in Supplementary Materials, Paleontology Ph.D. Employment Survey Summary.

In comparison, Butler and Maidment (Reference Butler and Maidment2019) reported about 50% of U.K. students with a Ph.D. in paleontology were still involved in academic research a decade later, which they identified as “a reason to be positive about the long-term future of our discipline” (p. 46), especially compared with order-of-magnitude lower estimates for all U.K. science doctorates from the Royal Society. The situation was clearly more negative when compared by gender; the 10-year survivorship was about 60% for male paleontologists but only 20% for female paleontologists. Due to a lack of long-term employment data for paleontologists in the United States, we could not compare the status of the U.S. market with the U.K. market.

A recent detailed analysis of patterns of hiring among American universities (Wapman et al. Reference Wapman, Zhang, Clauset and Larremore2022) demonstrated marked disparities of faculty production. Eighty percent of all faculty with degrees from U.S. institutions came from just 20% of universities, with 14% from only five universities. They also tracked hiring patterns relative to the assessed “prestige” of the producing and hiring universities. In geology, 80% of faculty in lower-ranked universities came from higher-ranked institutions, whereas only 12% went from lower- to higher-ranked universities (the remaining 9% were self-hires). In evolutionary biology, the numbers are 71%, 16%, and 14%, respectively. Although the data were not fine-grained enough to examine paleontology specifically (D. Larremore personal communication 2022), we strongly suspect the patterns would be similar, as supported by a cursory inspection of Ivy League and Big Ten paleontology faculty in the 2019 AGI directory.

Trends in NSF Funding

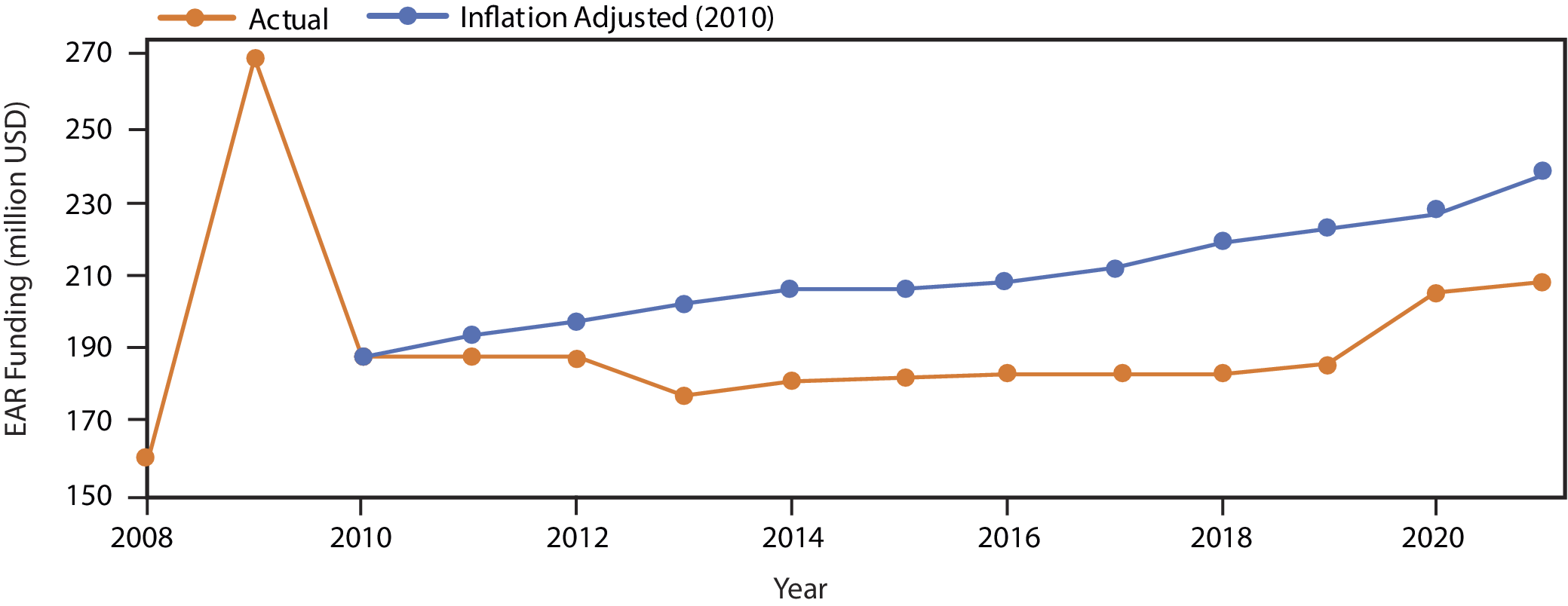

Hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions in many institutions of higher learning are driven by the ability of the applicant to obtain external funding to support research activities and to support graduate students and postdoctoral fellows involved in that research. With a few exceptions, only a small number of non-governmental grants are available to paleontologists. Most, but not all, federally supported paleontological research is funded by the SGP Program of the Division of Earth Sciences (EAR) of NSF. Figure 4 shows the history of EAR funding since 2008. EAR makes up about 20% of the total Directorate for Geosciences budget (in 2022, $201 million of $1.036 billion). Following the peak produced by the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, annual funding was virtually unchanged between 2010 and 2020, rising only in 2021 and 2022. This actually represents a substantial decline in funding when adjusted for inflation: $201 million in 2022 is equivalent to only $155 million in 2010 dollars (Fig. 2). In the current political environment, significant future increases should not be anticipated; Congress made substantial cuts to the requested 2024 NSF budget ($9.06 billion allocated vs. a request of $11.35 billion).

Figure 4. Division of Earth Sciences (EAR) funding 2008–2022. Actual and projected based on inflation-adjusted 2010 values. Based on data in National Science Foundation Budget Requests to Congress (most recent at: https://new.nsf.gov/about/budget/fy2024 ).

Apart from 2008, we lack separate comparative data for SGP; during that year, it was $5.9 million, 3.7% of the EAR budget, despite paleontology representing 7.2% of the Earth science community in 2007 (as noted previously). Assuming SGP still receives the same proportion of the EAR budget, an estimate for 2021 funding would be about $7.5 million (equivalent to $5.6 million in 2008 dollars).

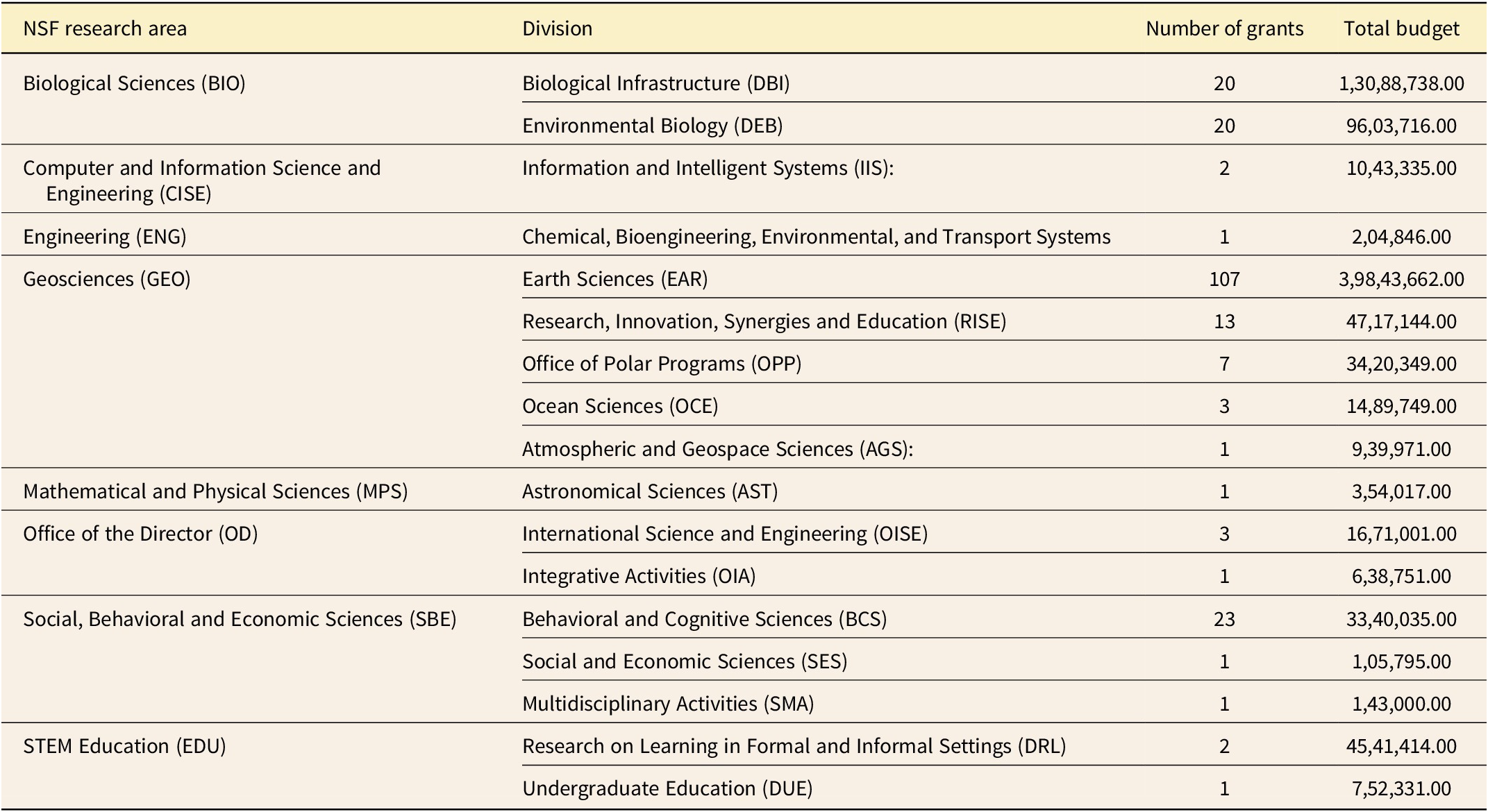

A keyword search on “paleontology” in the NSF database of currently active grants (https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/) yields 208 grants with a total funding of $85,897,854 as of April 2024. These comprise 137 separate projects (many projects are collaborative research). Table 3 shows a breakdown of these awards by NSF division; about half are funded by EAR. For many of these projects, paleontological research may not be the core activity. For example, Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences (BCS) grants fund archaeology and paleoanthropology projects, which may examine fossil humans, other fossil primates, and their paleoenvironments. The largest award, for $3,266,305, is for a STEM education project, producing a giant screen film on Antarctic dinosaurs. The second and third largest grants, totaling about $6 million are for postbaccalaureate mentoring projects that include paleontologists.

Table 3. Active National Science Foundation (NSF) awards with keyword “paleontology,” as of 5 February 2024. Downloaded from: https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

NSF directly funds some postdoctoral fellowships through programs such as Earth Sciences Postdoctoral Fellowships (EAR-PF) or as a budgetary component of a research grant. From 2019 to 2022, eight paleontologists received EAR-PF postdocs (Quirk and Bellocq Reference Quirk and Bellocq2022). A key issue is the low pay associated with most postdocs; most reflect the current National Institutes of Health (NIH) rate of $56,000 per year (Langin Reference Langin2023b), although many do not and may not adjust with inflation. NIH recently announced an increase in salary minima to $61,000 per year (Langin Reference Langin2024), but it is unclear whether other agencies will follow suit. Nevertheless, a single postdoctoral fellow can consume most of a project budget, reducing the incentive to include one in a research grant budget.

As a comparison with U.S. paleontology, we also obtained paleontology-related grant information for the European Research Council (ERC), the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), U.K., the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Supplementary Fig. S2). The data are not directly comparable, as NSERC also includes undergraduate, graduate, and postdoc awards, and the amount can be for the whole project (ERC and NERC) or per fiscal year (NSERC). The overall picture shows wide swings in both the number of projects and the amounts funded, with only NSERC showing a generally upward trend. As noted previously, in Argentina, a stronghold of paleontological research, scientific research is threatened by massive recent budget cuts to the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) (Ambrosio and Koop Reference Ambrosio and Koop2024).

What Should Professional Paleontological Societies Do?

The PS Employment Ideas Bank survey also gathered respondents’ thoughts on how professional societies should respond to concerns about employment. We received a wide variety of answers to the question “In your opinion, what initiatives from the Paleontological Society (or other related professional societies) would be beneficial in your own career or ongoing employment search?” Among the more common responses were: efforts to promote paleontology at colleges and universities; acting as a clearinghouse for paleontology positions, perhaps through a Listserv or website; and providing substantive guidance on alternative career paths that utilize knowledge obtained while completing a graduate degree in paleontology.

To the question “In your opinion, how can the Paleontological Society (or other related professional societies) better serve early career members?,” we identified as important answers: providing stopgap or bridge funding for those in between graduate school or postdoctoral fellowships and permanent jobs; providing other types of supportive funding; promoting the accomplishments of early-career members; and increasing opportunities for networking. More details are given in the Supplementary Materials, Brief Summary of the Employment Ideas Bank Responses.

Where Do We Stand?

The large number of student members in the PS and other professional societies, as well as their attendance and participation at national meetings, speaks well to the potential intellectual future of our discipline. But it is becoming increasingly clear, beyond anecdotal reports, that the employment prospects for young paleontologists have become increasingly grim. From our personal experiences, senior investigators are not being replaced as they retire, and in many cases, their positions, even their departments, are being eliminated. The number of available faculty positions falls far short of the number of doctorates awarded each year. Many of the jobs that do exist are non-tenure track and are not permanent and thus do not offer the prospect of longer-term financial security. The number of postdoctoral positions is inadequate; those that exist are underpaid. The limited number and size of available research grants negatively impacts decisions on hiring. As a result, an unacceptable percentage of those going through the lengthy academic process to become a paleontologist, a career that they want very much to pursue, end up leaving the field, even at the end of multiple postdoc appointments. The erosion of senior membership in our professional societies endangers these organizations’ long-term survival. The lack of positions also threatens efforts to increase diversity in the field (Berhe et al. Reference Berhe, Barnes, Hastings, Mattheis, Schneider, Williams and Marín-Spiotta2022; Arens et al. Reference Arens, Holguin and Sandoval2024). There is a clear existential threat to the future of our science unless these trends can be slowed and reversed. The need for effective action by our professional societies and by all paleontologists is urgent.

Recommendations

At the end of the day, we see the key overarching goal as first, to work to maintain or increase the number of paleontology positions going forward to ensure the sustainability of the discipline. This will require articulating the intrinsic value of our field to those outside it who can influence or control decisions on faculty positions and hiring. The second goal is to help inform early-career paleontologists accurately about the employment landscape in paleontology. A recent study of what it takes to get a tenure-track job in the ecological sciences in North America laid out a comprehensive analysis of the hires between 2016 and 2018, showing where doctoral graduates were getting academic jobs, and the various predictors (publications, postdoc tenure, teaching experience, etc.) of employment success (Fox Reference Fox2020). However, such data are sorely lacking in paleontology and challenging to compile, especially given the complex employment landscape for paleontologists in academia (Earth sciences, anatomy and medicine, ecology and evolution, etc.). But we believe that a coordinated data-collection effort by professional societies can ameliorate this issue. A third goal is to prepare early-career paleontologists to be as competitive as possible, including for positions in fields other than paleontology. Existing programs, such as the PS Boucot and Newell Grants are a good start but need to be added to and enhanced.

The committee recommends that the PS, other societies, and their members take the following actions:

-

1. We suggest that professional societies broadly distribute and promote position statements and webinars on the importance of paleontology, its interdisciplinary nature, and the transferable skills it provides. These should be targeted at decision makers outside paleontology, including Earth science and biology department heads, deans, and museum and university leaders, as well as government policy makers and industry professionals. As a first step, the essay “Paleontology Is Far More Than New Fossil Discoveries” was written by this committee and published online in Scientific American (Plotnick et al. Reference Plotnick, Anderson, Carlson, Jukar, Kimmig and Petsios2023). More such actions are needed.

-

2. Related to this, we urge all paleontologists to act as strong and active advocates for the science. They should take every formal and informal opportunity to not only promote their own work, but to emphasize paleontology’s importance within academia and to society. This paleontological advocacy can take many forms, including educating colleagues in academia, engaging in science policy activities, increasing outreach to K–12 students and community groups, and many others. We must become models for what paleontology is and does, what it looks like, and how it enriches science and society overall.

-

3. Individually, professional paleontological societies have relatively small memberships. It is vital that these societies explore methods to increase coordination, share information and resources, and speak with a shared voice. Such a consortium could also include international paleontological societies such as the PalAss and the International Palaeontological Association (IPA).

-

4. Individual professional societies must collect detailed, longitudinal membership data in order to track the health of their memberships in terms of employment: past, present, and future. The importance of this activity cannot be overemphasized in enabling employment changes over time to be quantified, compared, and evaluated. We also must better capture the number of paleontologists outside the geosciences. Mandatory surveys can be deployed at the time of membership renewal to gauge how many members are employed in full-time permanent positions, the nature of these positions (higher education/government/private sector/collections/preparation, active/emeritus, etc.), the various departments where paleontologists are employed (both geosciences and biosciences), and the number of members in temporary (postdoctoral fellowship, associate research scientist) and non–tenure track appointments (visiting assistant professorships, lecturers). Societies can collect and publish these data annually to give the membership a sense of the field as a whole, and how it changes over time. Examples are the annual report published by the American Historical Association (Grigoli Reference Grigoli2023) and the various documents on workforce released by AGI (e.g., Keane Reference Keane2022). This work will be vital to the future health of academic paleontology.

-

5. Efforts to communicate and coordinate with biological societies/programs (e.g., American Institute of Biological Sciences) and other geological societies, through AGI or otherwise, should be redoubled and diversified. We must find ways to improve our understanding of the variables that impact employment in science and to find ways to act in unison for shared goals. Opportunities for paleontologists to network with scientists in other disciplines, such as sessions at their meetings or presentations in their departments should be encouraged.

-

6. Societies should actively advocate for increases in relevant research funding within NSF. This should include regular face-to-face visits from leadership with program officers from several different NSF programs. Participation in the annual Geosciences Congressional Visits Day enables paleontologists to share information about their science with legislators and encourage them to support greater federal funding for science research.

-

7. Paleontological societies need to advertise better, and more broadly and frequently, what they already do to benefit the field, particularly to members of other societies.

-

8. We recommend that the societies, individually or together, establish a new fund to provide bridge funding for members who require short-term support between positions or require help to improve their chances of getting a job. Existing models are the PalAss Career Development Grant (https://palass.org/awards-grants/grants/career-development-grant) and the Association for Women Geoscientists Jeanne E. Harris Chrysalis Scholarship (https://www.awg.org/page/ScholarshipsandAwards).

-

9. Many job seekers and early-career paleontologists are not getting sufficient or effective support and mentoring. The opportunities offered by the Mentors in Paleontology Careers Event at GSA need to be expanded, broadened, and deepened by recruiting additional mentors who would be available for long-term consultation on a year-round basis.

-

10. The PS could host workshops or webinars to train early-career researchers (graduate students, postdoctoral fellows) to prepare them to excel during the application and faculty interview process by educating them about some components that they may experience during the faculty job-seeking process.

-

11. We urge paleontologists at degree-granting institutions to provide frank discussions of the employment situation in paleontology and to provide students with transferable skills that can be used in alternative careers (such as science policy, science writing, K–12 education and administration, data science, government, industry, and many others). The diverse knowledge and experience gained while completing a doctorate in paleontology will be extremely valuable to many different types of employers. A similar proposal was made by Butler and Maidment (Reference Butler and Maidment2019). This may include training in skills and certifications that are typically desirable for regulatory compliance paleontology positions, including project management, GIS, and regulatory compliance training.

-

12. Increasing the number and desirability of postdoctoral fellowships and permanent research positions should be a high priority. This can include:

-

a. Gathering more longitudinal data on the status of postdocs in the societies and the number of available postdocs. Of particular interest is how many early-career members have had more than one postdoctoral position, how that number has changed over time, and what the salary range of these positions has been.

-

b. Societies should advocate at NSF for higher minimum wages for postdoctoral fellows, in line with efforts at NIH.

-

c. We recommend that the societies consider fundraising to establish an annual competitive 2-year postdoctoral fellowship program for one or more graduate student members.

-

Conclusion

In an effort to better understand the employment landscape for academic paleontologists, largely in the United States, we present a rather gloomy and still somewhat murky picture. While it is often lamented that employment in the field of paleontology has always been uncertain and that job prospects have always been grim (e.g., Thayer and Brett Reference Thayer and Brett1985), as scientists we should take a data-driven approach to these problems. As professional paleontologists, it is our job to train the next generation and ensure that our field remains healthy and sustainable. But we are doing a disservice to our students and future generations of paleontologists if we are not honest with them about the availability of potential employment opportunities and do not provide them with the appropriate training to pursue this field professionally. Yes, we are all in this field because we love fossils and the mysteries of deep time, but at the same time, we are training students and imparting skills for an employable career. We need to ensure, with relevant, longitudinal data, that we are not only informing incoming and current students about the state of the discipline, and what it takes to succeed in academic paleontology 5, 10, or 20 years into the future, but also training them for a job that might be radically different from those available to them today. Paleontology is as dynamic and intellectually vital as ever; we must work harder to keep it thriving in academia.

Note: The text of this paper was completed before the 2024 U.S. presidential election and the subsequent and ongoing changes to the NSF and other granting agencies. These institutional and policy changes will be especially impactful to early-career paleontologists and paleontologists who have engaged in JDEI (justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion) work in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank F. Smith for providing the American Society of Mammalogists “vision document,” H. Harper for the membership data for SEPM, T. Schlüter for the membership data for the Paläontologische Gesellschaft, J. Hellawell for the membership data for the Palaeontological Association, and the Society for Vertebrate Paleontologists for making its data available. Updated NSF information on U.S. doctorates was provided by J. Gordon of RTI International. We gratefully acknowledge the willingness of SVP and the Cushman Society in distributing the Ideas Bank survey to their members. C. Keane (American Geosciences Institute) provided current academic employment numbers. M. Marshall provided invaluable assistance in getting the word out about our activities and surveys. We would also like to acknowledge the respondents to the PhD Employment Status and PS Employment Ideas Bank surveys. S. Maidment and an anonymous reviewer provided valuable comments on the original submission of this paper. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Additional information and figures are in the Supplementary Materials, available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11088008.