Scholars have documented the specific political significance of houses of worship; that is, how these institutions influence or at least correlate with the political attitudes and behaviors of individuals who attend them. Existing works have established relationships between worship service attendance and various political attitudes (Brooke, Chouhoud, and Hoffman Reference Brooke, Chouhoud and Hoffman2023; Lewis, MacGregor, and Putnam Reference Lewis, MacGregor and Putnam2013; Pepinsky, Liddle, and Mujani Reference Pepinsky, Liddle and Mujani2018), explored how the internal dynamics of houses of worship influence the political outlooks of their congregations (e.g., Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe and Gilbert2008; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2008), and examined how political actors co-opt houses of worship for political purposes (Brooke Reference Brooke2019; Wickham Reference Wickham2002).

The present study focuses on the broader political significance of houses of worship―how they influence the political attitudes and behaviors of the communities in which they are located. Exploring how houses of worship influence the community at large is more than an intriguing academic exercise, however; it is critical to our understanding of how these institutions contribute to democratic erosion and consolidation around the world.

On the one hand, houses of worship positively contribute to democratic life by promoting political participation, including among minority groups who have limited access to political resources (Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Westfall Reference Westfall2019). On the other hand, houses of worship may also spread illiberal attitudes. Religious institutions often reiterate traditional gender norms (Kalbian Reference Kalbian2005; Wickham Reference Wickham2002). The staunch support among Evangelicals for a figure as divisive as Donald Trump cannot be separated from the strong networks and beliefs formed in their churches (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Margolis Reference Margolis2020).

In the context of Muslim societies, both scholars and observers have expressed concerns that mosques may spread intolerant views (Hamid Reference Hamid2015; Tohamy Reference Tohamy2018; Wickham Reference Wickham2002). For example, in Indonesia, a 2017 study by the Association for the Development of Religious Boarding Schools and Society found that about 40% of mosques in government office complexes surveyed were spreading intolerant and antigovernment views (Jakarta Post 2018), such as support for turning Indonesia into a caliphate or anti-Christian and anti-Jewish messaging (Wardah Reference Wardah2018). In other cases, mosques may also embrace overtly partisan roles. During the heated 2017 gubernatorial election in Jakarta, for example, some mosques put up banners stating that they refused to give last rites to supporters of the Chinese Christian candidate Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Jakarta Post 2017).

Given the political significance of houses of worship, it is imperative to gain a more complete picture of how these institutions influence not only their congregations but also the broader communities where they are located. In this article, I examine the effects of houses of worship of the community’s majority religion, in this case mosques in Muslim-majority communities in Indonesia, on the majority group’s political attitudes. I combine information about attitudes of more than 16,000 panel respondents in the Indonesian Family Life Survey Round 4 (2007) and Round 5 (2014) who reside in more than 1,000 kecamatan (districts) with the locations of more than 300,000 mosques scraped from a government database.

Indonesia’s political and religious contexts offer a unique setting to examine how houses of worship, specifically mosques, influence their communities. Mosques in the country are important neighborhood institutions. They offer not only spaces to do salat (prayers) but also organize various religious and nonreligious activities for the whole community. These roles make them particularly likely to influence the community at large.

The country also has a relatively open and free society. Diverse religious views, ranging from those supporting sharia and a caliphate to those advocating secularism, are openly expressed (Pepinsky, Liddle, and Mujani Reference Pepinsky, Liddle and Mujani2018). Mosques also enjoy a high level of autonomy: the government neither regulates nor monitors sermons and mosque activities. This increases the likelihood that the findings here reflect the effects of mosques themselves and not the effects of government censorship.

Using a difference-in-difference approach, I find that an increase in the number of mosques in a district primarily corresponds with higher exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims among Muslim respondents. These exclusionary attitudes manifest in stronger objections to non-Muslims living in the village, the neighborhood, and in the same house as the respondent, as well as stronger objections to non-Muslim houses of worship and interfaith marriage. To a lesser extent, new mosques also correlate with a stronger emphasis on religious similarity in voting decisions.

In a more indirect, exploratory manner, I further examine the mechanisms through which mosques may shape their communities, comparing the relative explanatory powers of their roles in promoting religiosity (confessional mechanism), strengthening religious identity and networks (psychosocial mechanism), and channeling information (information mechanism) in explaining the observed effects. I find suggestive evidence for the importance of the information mechanism, because the influence of mosques is weaker among individuals who have access to alternative sources of information and who possess a stronger ability to critically evaluate information.

These effects, I argue, are unlikely to be fully attributable to a selection effect, in which mosques are more likely to be built in districts with higher religious exclusions from the outset. On the empirical front, I demonstrate the robustness of the effects through alternative model specifications, including an examination of parallel trends and a matching method. I also conduct placebo tests, which show that, without new mosques, there are no exclusionary effects.

On the theoretical front, the selection concern implies that exclusionary districts should be more likely to build mosques than those that are less exclusionary. However, it is unclear why this would be the case. Studies on religious discrimination in Indonesia actually show that exclusionary religious attitudes manifest in the rejection of non-Muslim houses of worship, not in the construction of new mosques (Ali-Fauzi et al. Reference Ali-Fauzi, Samsu Rizal Panggabean, Sumaktoyo, Husni Mubarak and Nurhayati2011; Crouch Reference Crouch2010).

Religious identity may be a theoretically relevant confounder. However, I find that new mosques are more strongly related to outgroup rejection than to a preference for Muslim candidates and trust toward fellow Muslims: two variables that are related to religious identity. In exploring potential mechanisms, I also find that a set of variables indirectly measuring religious attachment fail to significantly condition the effects of mosques.

I do not contend that religious identity does not matter or that mosque construction is exogenous to political attitudes. Rather, my argument is that, even if other factors matter, a process takes place within mosques after they have been built that influences their broader communities—in this case, the development of exclusionary attitudes. This process is facilitated by the mosques’ role as an information and communication channel for their communities and by the prevalence of discourses regarding relations between Muslims and non-Muslims in Indonesian mosques (al-Makassary Reference al-Makassary2013; al-Makassary and Gaus Reference al-Makassary and Gaus2010). It is this process that this study captures as the broader political effect of mosques on their communities.

These findings, in turn, carry significant policy implications. In contexts where houses of worship are central to a community’s life, addressing their potentially negative influence should not involve censorship or surveillance. Instead, promoting alternative sources of information and enhancing information literacy are key strategies. This approach will diminish the informational centrality of houses of worship and expose citizens to alternative viewpoints.

Specific Significance of Houses of Worship

Existing studies on the political significance of houses of worship generally have one of three research agendas: (1) those that establish correlations between religious attendance and political outcomes, (2) those that focus on the internal dynamics of houses of worship, and (3) those that study political elites’ use of houses of worship for political purposes.

Religious Attendance and Political Outcomes

Studies with the first agenda use public opinion surveys to establish correlations between participation in worship activities and political outcomes of interest. The effects of houses of worship are therefore measured only indirectly through the survey respondents’ reports of their activities in these places—primarily the extent to which they attend religious services.

These studies have uncovered noteworthy empirical patterns. Scholars find that attendance and participation in religious activities are positively correlated with political and civic participation (Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii 2011; Fleischmann, Martinovic, and Böhm Reference Fleischmann, Martinovic and Böhm2016; Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) and that the effect seems to be causal (Gerber, Gruber, and Hungerman Reference Gerber, Gruber and Hungerman2016).

There is evidence that the effects are more nuanced among minority groups. In a study of Muslim Americans, Westfall (Reference Westfall2019) finds that mosques facilitate political participation primarily among believers who visit mosques not just to pray but also to engage in social activities. In the British context, Sobolewska et al. (Reference Sobolewska, Fisher, Heath and Sanders2015) find that religious attendance boosts political participation among Muslims and Sikhs but not Hindus, attributing the finding to the latter’s lack of politicization in British politics.

Beyond political participation, studies also have established correlations between worship attendance and political attitudes, such as opposition to the death penalty among Catholics (Bjarnason and Welch Reference Bjarnason and Welch2004), more altruistic foreign policy views (Petrikova Reference Petrikova2019), lower support for redistribution (Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2013), and stronger environmentalism (Peifer, Khalsa, and Howard Ecklund Reference Peifer, Khalsa and Ecklund2016).

In a particularly creative study that examines data from the Arab world and uses variations in the interview day, Brooke, Chouhoud, and Hoffman (Reference Brooke, Chouhoud and Hoffman2023) find that Muslim respondents interviewed on a Friday, when Muslims practice the Friday prayer at mosques, express stronger exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims than those interviewed on other days. Overall, although this first research agenda measures the effects of houses of worship only indirectly through self-reported religious attendance, it offers initial evidence of the power of houses of worship in shaping political attitudes and behavior.

Internal Dynamics in Houses of Worship

The second research agenda explores the relationship between religious attendance and political behavior by examining the dynamics within houses of worship by surveying the clergy, congregation, or both (Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe and Gilbert2008; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2008; Smith Reference Smith2008; Wald, Owen, and Hill Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1988). Findings from this research confirm the capacity of houses of worship to influence believers, such as by cultivating civic skills conducive to political participation and shaping political attitudes, but not without adding nuances.

An ethnographic study by Lussier (Reference Lussier2019) of three mosques, two Protestant churches, and two Catholic churches in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, provides a compelling example. She finds that the churches provide more opportunities to develop civic skills than the mosques. She attributes this to the churches’ more formal and hierarchical organizational structures, in which they are parts of larger denominational structures and anointed clergy members hold positions of organizational significance. Such structures require believers to navigate decision-making processes more carefully and thoroughly when dealing both with internal church matters and with other churches. The mosques’ structures, in contrast, are more informal and rely on neighborhood ties more than organizational procedures. There are no anointed clergy members; the mosques are not parts of denominations and therefore are relatively independent in managing their own affairs based on community agreements.

Djupe and Gilbert (Reference Djupe and Gilbert2008) provide another example that is more specific to Christian congregations in the United States. They identify different elements of church life relevant to political behavior, such as social networks, the church environment, and personal attributes. These elements expose churchgoers to different pieces of information and influence their receptivity to this information. For example, rather counterintuitively, the more committed churchgoers are to their church, the more likely they are to misperceive clergy political cues (69). All these findings complement the first research agenda and more directly illustrate how houses of worship shape political attitudes and behaviors of their congregations.

Political Elites and Houses of Worship

A third research agenda on the effects of houses of worship highlights how political actors often use mosques for political purposes and public outreach. Primarily drawn from cases in Muslim societies, studies using this approach do not aim to directly establish correlations between activities in houses of worship and political attitudes but rather to highlight the centrality of mosques to believers and the community.

Brooke (Reference Brooke2019), for example, provides an extensive account of how Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and Anwar Sadat’s (and then Hosni Mubarak’s) administration competed in leveraging mosques to provide social services and win public approval, such as by attaching healthcare clinics to popular mosques. Wickham (Reference Wickham2002, 130) provides a similar account, highlighting the roles of mosques in Egypt as entry points for personal da’wah or persuasion. Mosque activists, trained and educated in mosque study groups, would approach people in the community—starting with relatives, neighbors, and close friends—and persuade them to practice Islam more fully and in a way that they considered more proper.

In addition to using mosques for public outreach and as mobilization hubs, political elites can also use them to suppress dissent and build cultural capital. The governments of some Muslim countries, for instance, put mosques under strict monitoring and set themes for sermons, in part to counter radical messages and in part to suppress dissent (Kuru Reference Kuru2019). Yet, the same governments also often shower mosques with money to gain influence or build relations with Islamist groups (Brooke Reference Brooke2019; Buehler Reference Buehler2016).

A Case for a Broader Political Significance

The preceding section outlined the different approaches scholars use to study the political significance of houses of worship and reviewed evidence for their specific significance. The goal of the present study, however, is to demonstrate a broader political significance of houses of worship; that is, how they influence the community at large and not just their congregation.

I define the influence of houses of worship on the community—or community influence—in the context of majority–majority relations: how houses of worship of the majority religious group in a community affect the politically relevant attitudes and behaviors of members of that group. For example, this includes how mosques shape Muslims’ political behavior in a Muslim-majority community, how Catholic churches shape Catholics’ attitudes in a Catholic-majority community, and so on. This scope carries three implications.

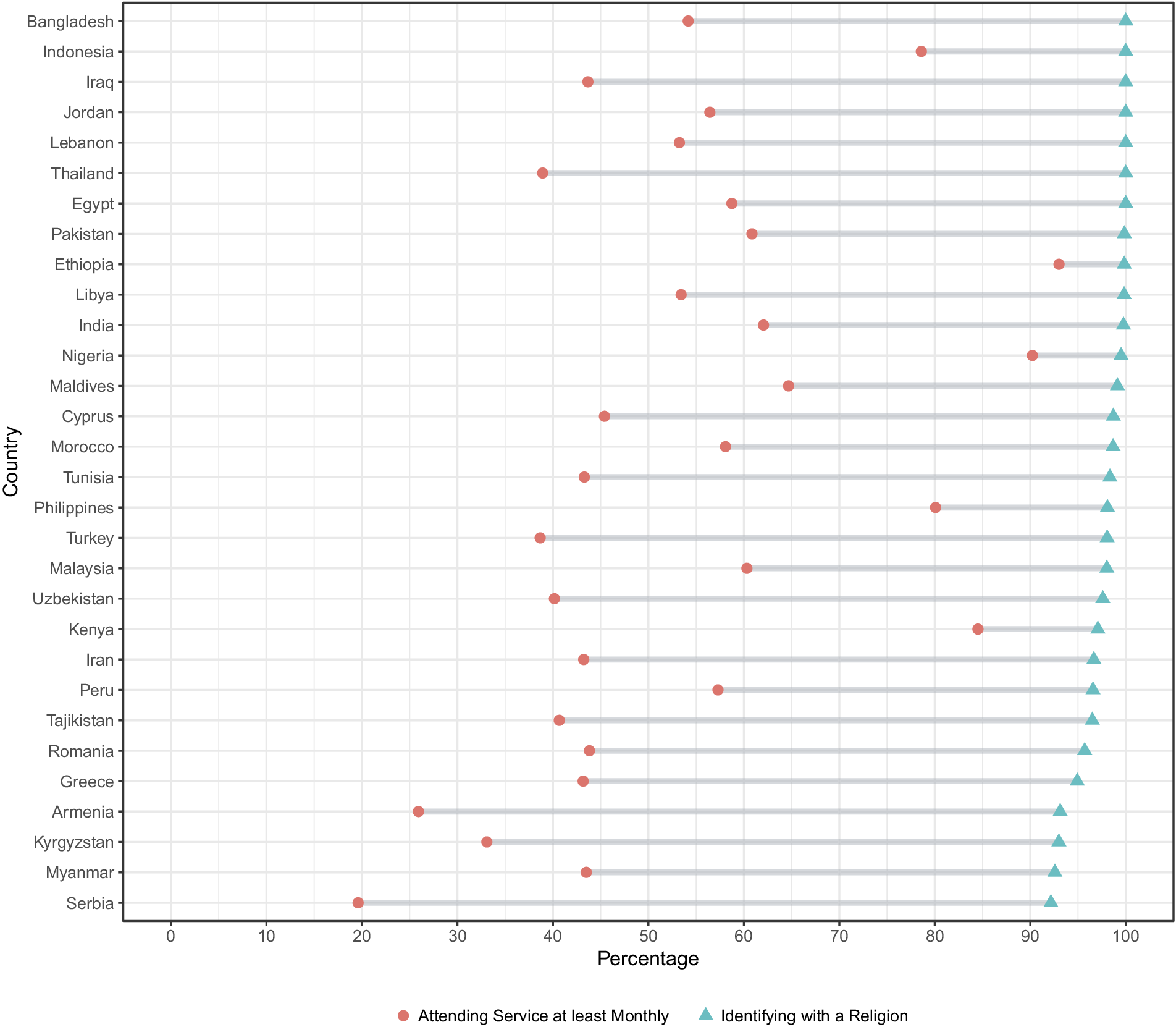

The first implication is that I do not make assumptions about whether the believers attend houses of worship but only that they live in the same area as these houses of worship. It is possible for people to identify with a religious group but not practice their faith; for example, by not praying or not attending religious services regularly (Smidt, Kellstedt, and Guth Reference Smidt, Kellstedt, Guth, Guth, Kellstedt and Smidt2009). Worldwide, religious attendance is always lower than religious identification (figure 1). This suggests that an inquiry into community influence is qualitatively distinct from inquiries into the effects of houses of worship on individuals who report attending them.

Figure 1 Religious Identification and Religious Attendance in 30 Countries with the Highest Levels of Religious Identification (World Values Survey 7)

The second implication is that the definition of community influence used here separates this study from others that examine how a minority religion’s houses of worship influence the community, such as a study on the effects of mosques on support for far-right movements in the Netherlands (Gravelle, Medeiros, and Nai Reference Gravelle, Medeiros and Nai2021) or a study on church construction and social tensions in Jakarta (Ali-Fauzi et al. Reference Ali-Fauzi, Samsu Rizal Panggabean, Sumaktoyo, Husni Mubarak and Nurhayati2011). It also means that the study is not focused on the effects of the majority religion’s houses of worship on members of the minority religious groups in the community. Although an important research topic, this question would require a different framework than ones in the existing literature on houses of worship; for example, through approaches that study how minority groups respond to real or perceived threats (Oskooii Reference Oskooii2020).

The third implication is that the present study treats houses of worship as a black box, measuring only their effects as a whole without disaggregating them into constituent components, such as the scripture, the sermons, the clergy, the congregation network, the organization hierarchy, or the history of the religious group itself. Although I agree that a more nuanced examination of community influence is a fruitful research avenue, the black box approach is more of a feature, not a limitation. Before diving into the details, one needs to ascertain first that there is enough empirical evidence for a community influence, regardless of specific antecedents.

Having discussed what community influence means, the next step is examining how houses of worship might actually shape political attitudes and behavior in the community. The literature on the effects of houses of worship on believers points to three mechanisms, which may be empirically interrelated but are nonetheless conceptually distinct: by promoting religiosity and instilling religious values (confessional mechanism), shaping social ties (psychosocial mechanism), or providing information and cultivating politically relevant skills (information mechanism). In the next section, I discuss how these mechanisms may play out more concretely in the context of the present study’s case of Indonesia.

Confessional Mechanism

The confessional mechanism highlights the most fundamental function of a house of worship: it is a place to practice and learn about one’s faith. Houses of worship may influence attitudes and behavior in the community by promoting religiosity—encouraging believers to be involved in their activities and emphasizing the importance of certain religious beliefs. Independent of religious beliefs, scholars have linked religiosity to political outcomes, such as political intolerance (Gibson Reference Gibson, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; Sumaktoyo Reference Sumaktoyo2021), redistributive politics (De La O and Rodden Reference De La, Ana and Rodden2008), and support for democracy (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2021).

Houses of worship are also essential for disseminating and maintaining the importance of religious beliefs. Through sermons, bulletins, and religious study groups, believers learn about the tenets of their faiths. Religious beliefs, in turn, are a potent factor shaping political attitudes and behavior. They shape immigration attitudes among Catholics, Muslims, and Jews (Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Reference Bloom, Pazit and Courtemanche2015); opposition to the death penalty (Bjarnason and Welch Reference Bjarnason and Welch2004); support for religious violence (Fair, Malhotra, and Shapiro Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2012); and how individuals seek information (Cragun Reference Cragun2022), among others.

These teachings and invitations to participate may be addressed both to the congregation and the community. Banners or signs outside a house of worship can “preach” to the community by displaying and making salient certain scriptural verses, which Condra, Isaqzadeh, and Linardi (Reference Condra, Isaqzadeh and Linardi2019) argue are a particularly powerful component of a religion.

Psychosocial Mechanism

The second avenue through which houses of worship, and religion in general, may influence political attitudes is through their roles in cultivating social networks and strengthening group identity (Everton Reference Everton2018; Ladam, Shapiro, and Sokhey Reference Ladam, Shapiro and Sokhey2019). Sermons and religious activities can bridge differences within a congregation, such as those concerning race and ethnicity or social status (Cobb, Perry, and Dougherty Reference Cobb, Perry and Dougherty2015; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2002), helping make people “united in faith.” But this unity in faith may also reinforce and make salient boundaries between fellow believers and religious outsiders. When houses of worship encourage members of the community to participate in their activities, whether religious or secular, such participation may also foster group consciousness (Jamal Reference Jamal2005) and religious identification (Zanna, Olson, and Fazio Reference Zanna, Olson and Fazio1981).

The psychosocial effects also cannot be separated from the nature of houses of worship as neighborhood institutions characterized by friendship and kinship ties (Wald, Owen, and Hill Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1988). Neighborhood bonds formed outside a house of worship influence interactions in the religious community. Similarly, religious bonds formed within a house of worship often persist in, and influence, daily social interactions.

That houses of worship often organize a wide range not only of religious but also of social activities implies that the initial social encounters may not be religious in nature, yet the resulting networks and identity are still religious. Wickham (Reference Wickham2002, 130), for instance, provides an example of an Egyptian mosque using sporting events to build ties with the community. Similarly, Salim, Kailani, and Azekiyah (Reference Salim, Kailani and Azekiyah2011) describe how Muslim activists cultivate networks and the religious identity of high school students in Indonesia through nonreligious activities. So important are social ties in Muslim identity that even among pietists known to devote themselves to reciting and discussing the Quran, “virtue is constituted primarily through social exchange and interaction (mu‘aamalaat) rather than simply through worship (‘ibaadaat) or ritual practices that discipline the self” (Anderson Reference Anderson2011, 3).

Information Mechanism

Lastly, the information mechanism emphasizes the roles of houses of worship as channels for communication and information. It is conceptually distinct from the confessional mechanism because, even though religious doctrine is also a type of information, the information mechanism focuses primarily on information about the world. It is also distinct from the psychosocial mechanism, which emphasizes the roles of social ties in fostering group identity and consciousness, rather than providing information.

Religious and nonreligious communal activities organized by a house of worship can inform the community about issues of interest, beyond their effects on strengthening group identity. Black churches, for example, were essential for educating and mobilizing African Americans during the civil rights movement (Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown2000). Houses of worship also cultivate civic skills conducive for political participation (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Studies, in turn, find that attitudes and behavior can spread through networks (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Adam, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012), suggesting that what believers learn in their places of worship may diffuse to the community as well.

It is reasonable to suspect that the same information effects apply equally, if not more strongly, to mosques in Muslim societies. More so than churches in Western societies, mosques fulfill a broad range of roles. During the founding era of Islam, mosques served as the center of government, in addition to many other functions (Muhammad Reference Muhammad1996): they literally fulfilled religious, political, and social functions.

Mosques may have lost their formal political roles in the contemporary world because governments no longer rule or hold courts from mosques and overt political campaigns conducted in mosques are increasingly frowned on (Channel News Asia 2023; Jakarta Post 2023). But their religious and social functions are largely intact, and the boundary between the two is not always clear.

Contemporary mosques conduct study groups, serve as community health centers, provide early childhood education, coordinate assistance for the poor, and cultivate financial literacy (Al-Krenawi Reference Al-Krenawi2016; Brooke Reference Brooke2019; Muhammad Reference Muhammad1996; Wickham Reference Wickham2002). Furthermore, just like in churches, sermons in mosques can touch on social or even political issues. These sermons are often broadcast through external speakers, reaching not only those praying inside but also those living around the mosque, thereby amplifying their effects on the community.

The use of loudspeakers to broadcast calls for prayer and religious sermons, as well as the various events and activities where social exchanges take place, constitutes public rituals that influence norms in the community and contribute to common knowledge (Chwe Reference Chwe2003). They shape not only community members’ perceptions of what are proper behaviors or acceptable views on an issue but also their perceptions of what fellow community members know. This condition, where residents get their information from local mosques and know that others get information from there as well, further reinforces the importance of mosques as channels for communication and sources of information in their communities.

Case and Context

I situate my study in the context of Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim-majority country and the third most populous democracy, for theoretical and practical reasons. On the theoretical front, studying Indonesia offers an opportunity to tackle questions pertaining to the effects of democratization on the interactions between religion and politics at the mass level. Indonesia’s dictator, Suharto, severely curtailed Muslim organizations and their influence during his rule from 1966 to 1998. These constraints weakened after his downfall, leading to a “conservative turn” (van Bruinessen Reference van Bruinessen2013) that is most visible among elites. Islamic organizations increasingly assume roles as political brokers (Sebastian, Hasyim, and Arifianto Reference Sebastian, Hasyim and Arifianto2020), and political elites, openly engage in religious politicking, such as by providing in-kind and financial aid to religious organizations or by advancing religious ordinances (Buehler Reference Buehler2016).

However, it is unclear to what extent this turn applies to Muslim voters. On the one hand, there is evidence that it is manifesting in societal discrimination against religious minorities (Sumaktoyo Reference Sumaktoyo2020), support for strict dress codes for women (Harsono Reference Harsono2021), increased prevalence of exclusionary sermons (al-Makassary and Gaus Reference al-Makassary and Gaus2010), and spatial segregation based on religion (Mulya and Schäfer Reference Mulya and Schäfer2023). Others argue that the conservative turn among Muslim Indonesians is more about personal piety than politics. Pepinsky, Liddle, and Mujani (Reference Pepinsky, Liddle and Mujani2018) find that there are practically no relationships between religious beliefs and political behavior at the individual level. Mietzner and Muhtadi (Reference Mietzner, Muhtadi, Fealy and Ricci2019) find religious intolerance actually declined from 2010 to 2017 and increased again only after a heavily politicized gubernatorial election in Jakarta, implying that the turn is more of an elite than a mass phenomenon. Ahnaf and Lussier (Reference Ahnaf and Lussier2019) find that Muslim clerics refrained from delivering political sermons even during a polarized local election in Yogyakarta.

The present study contributes to this debate by examining changes in Muslims’ political attitudes over time and situating them within the context of influences exerted by mosques, a socially significant religious institution. As detailed later, the picture that emerges is one where mosques contribute to a conservative turn among the masses, especially in the form of exclusionary religious attitudes toward non-Muslims.

Indonesia has a relatively democratic and open society, in which mosques are relatively independent from government interventions and citizens may freely express their political views. Unlike in some other Muslim-majority societies where the government regulates sermons or closely monitors mosques (Kuru Reference Kuru2019), mosques in Indonesia enjoy a high degree of autonomy.

There are no formal restrictions on sermons, and there are no reports of the government shutting down mosques, except for a few mosques of the Ahmadiyya and Shia communities that some consider heterodox (Burhani Reference Burhani2014). Even government efforts to certify preachers and limit the loudness of mosque speakers have been resisted by Islamist leaders (Suryana Reference Suryana2022). Similarly, at the mass level, people express their views on social, political, and religious issues relatively freely (e.g., Pepinsky, Liddle, and Mujani Reference Pepinsky, Liddle and Mujani2018). My findings therefore would reflect the effects of mosques themselves, and not the effects of government censorship.

Lastly, and most importantly, mosques in Indonesia are neighborhood institutions and thus particularly relevant to efforts to study community influence. As detailed later, mosques organize activities and provide social services for their neighborhoods. At the same time, residents hold mosques in high esteem and ensure they are well cared for. Data from the Ministry of Religious Affairs analyzed here show that well over 90% of mosques in Indonesia are built on community-donated land (i.e., waqf), as opposed to purchased land. In a waqf scheme, a member of the community donates their land to be used as a mosque site (or for other religious facilities), forgoing potential monetary benefits from the land. Bazzi, Koehler-Derrick, and Marx (Reference Bazzi, Koehler-Derrick and Marx2020) show that localities with more waqf lands have a stronger Islamist presence and slower economic growth. For this study, the waqf system illustrates how community members often prioritize supporting mosques over material interests, emphasizing the vital role these institutions play in their communities.

Before describing the data, it is useful to explain how the roles of mosques as neighborhood institutions relate to the three mechanisms of community influence described earlier. How do these mechanisms operate in the Indonesian context, and how are they reflected in different mosque activities or events?

Mosque Y, a neighborhood mosque on the outskirts of Jakarta, serves as an illustrative example of how these three mechanisms manifest in various mosque activities. Often, a single activity activates multiple mechanisms, highlighting that this study does not aim to isolate which mosque activities matter most. Rather, it focuses on understanding how these mechanisms emerge in different activities and why these activities are significant.

Regarding the confessional mechanism, one of the many ways Mosque Y promotes religiosity is through its calls to prayer (azan). Every day at around 4.30 a.m., the mosque’s loudspeakers broadcast the azan across the neighborhood. Some nearby mosques begin even earlier, preceding the azan with 15- to 20-minute recordings of prayers or Quranic recitations. Throughout the day, each mosque broadcasts at least five calls to prayer, marking the five mandatory daily salat in Islam. The loudness of these broadcasts varies from mosque to mosque and has sparked spirited debates. Islamist leaders have successfully resisted a recent government effort to standardize mosque speaker volume to a maximum of 100 decibels (Suryana Reference Suryana2022).

Another way in which Mosque Y promotes religiosity is through religious discussion groups and prayer sessions, including Friday prayers. Religious discussion groups are held twice a week and attended by about 10 to 20 people. The mosque invites an ustaz (teacher) to lead these sessions, during which he provides lessons on topics such as the life of the Prophet or the importance of salat. On Fridays, Muslim men from the neighborhood gather to pray and listen to the Friday sermon. Many of these sermons encourage believers to practice salat regularly or read the Quran. They are also broadcast throughout the neighborhood, allowing those who remain at home to listen.

In addition to promoting religiosity, Mosque Y also fosters group identity and solidarity among Muslims (the psychosocial mechanism). The calls to prayer mentioned earlier—broadcast five times a day through loudspeakers—not only reinforce religious devotion but also strengthen religious identity. For instance, on December 20, 2024, Nasaruddin Umar, Indonesia’s minister of religious affairs, expressed concern that in an elite residential complex in Jakarta, the azan could only be faintly heard. He emphasized that it serves as an expression of Muslim identity and, in a Muslim-majority province like Jakarta, no area should be devoid of it.

Religious discussion groups and Friday prayer sermons that emphasize Muslim solidarity and brotherhood (ukhuwah Islamiyyah) also promote group identity. These sessions and sermons often encourage believers not only to remain steadfast in their salat but also to support fellow Muslims; for example, through charitable giving or by donating to the construction of mosques in impoverished areas or in the eastern provinces where Muslims are a minority.

Activities that provide time and space for believers to connect with one another also contribute to the psychosocial mechanism. Some attendees stay after prayer sessions or discussion groups to chat and spend time together, thereby strengthening their bonds. Several times a year, notably during Eid al-Adha, Mosque Y distributes groceries or organizes charity drives to assist Muslim community members in need—reinforcing the obligation to help fellow Muslims and deepening group solidarity.

Lastly, various activities may contribute to the informational role of mosques as channels of communication within the neighborhood. The religious discussion groups and Friday sermons can deliver “knowledge,” regardless of its accuracy. This knowledge may be relatively innocuous, such as recommendations for books and websites that help individuals become better Muslims or encouragement to vote in upcoming elections.

At times, however, the knowledge shared can also be political or even partisan. Sermons and discussion groups, for instance, may disseminate information about perceived social injustices affecting the broader population or Muslims specifically or even about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. During the heated campaign for Jakarta’s 2016 gubernatorial election, for example, sermons over several weeks included admonitions against voting for the Chinese Christian candidate Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok).

The use of external loudspeakers facilitates the transmission of information from mosques to the broader community. The religious and sometimes political contents of sermons and discussion groups are broadcast throughout the neighborhood, in addition to more benign local news, such as the passing of a neighbor, opportunities to receive COVID vaccinations, or reminders to contribute to neighborhood funds.

However, public broadcasts are not the only way through which a mosque establishes its importance in the community. Network contagion (Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2007; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2008), whereby mosque attendees share what they learn and experience at mosques with others in their lives, represents another channel. People discuss significant matters with their close contacts, and in Indonesia, where 80% of the population reports attending religious services at least monthly and 98% considers religion very important (World Values Survey 7), religion is bound to be one of those significant matters.

Being relatively small, Mosque Y cannot offer some of the services provided by larger mosques. Many mosques accommodate government initiatives such as the integrated healthcare program (Posyandu, or Pos Pelayanan Terpadu), which educates the public about children’s health. Other mosques host neighborhood meetings, run childcare and early childhood education centers, operate co-op stores, provide ambulances for community use, and manage healthcare clinics, in addition to their religious functions.

Through these activities, mosques become important not only to those who regularly pray there but also to others in the community; for example, women in Indonesia typically do not attend Friday prayers, yet they may visit mosques for childcare services or monthly social savings group (arisan) meetings. Mosque loudspeakers serve as a source of both religious and secular information that people pay attention to, and mosques themselves provide spaces for people to meet and interact and, in doing so, strengthen their religiosity, build networks with fellow Muslims, or gain knowledge about the world around them.

Data and Methods

Although this article analyzes various sources of data, the core of the analysis relies on three datasets (Sumaktoyo Reference Sumaktoyo2025). The first data source is a dataset on mosques and musallas scraped from the Sistem Informasi Masjid (SIMAS, Mosques Information System).Footnote 1 SIMAS was introduced in 2014 and is managed by the Ministry of Religious Affairs. As of December 2023, it had records of 302,837 mosques and 367,742 musallas. Each record includes several pieces of information, including the mosque’s name, year of construction, and its location down to the kecamatan or district level (the third administrative subdivision in the country). The system is based on self-reporting, with the government encouraging mosque administrators (takmirs) to register their mosques. In return, registration in the system enables administrators to access government funding.

This self-report works in favor of my analysis. The act of registration indicates that takmirs are willing to work with the government. This suggests that registered mosques are likely less ideologically extreme than those whose takmirs refuse to participate, potentially underestimating the exclusionary effects presented here.

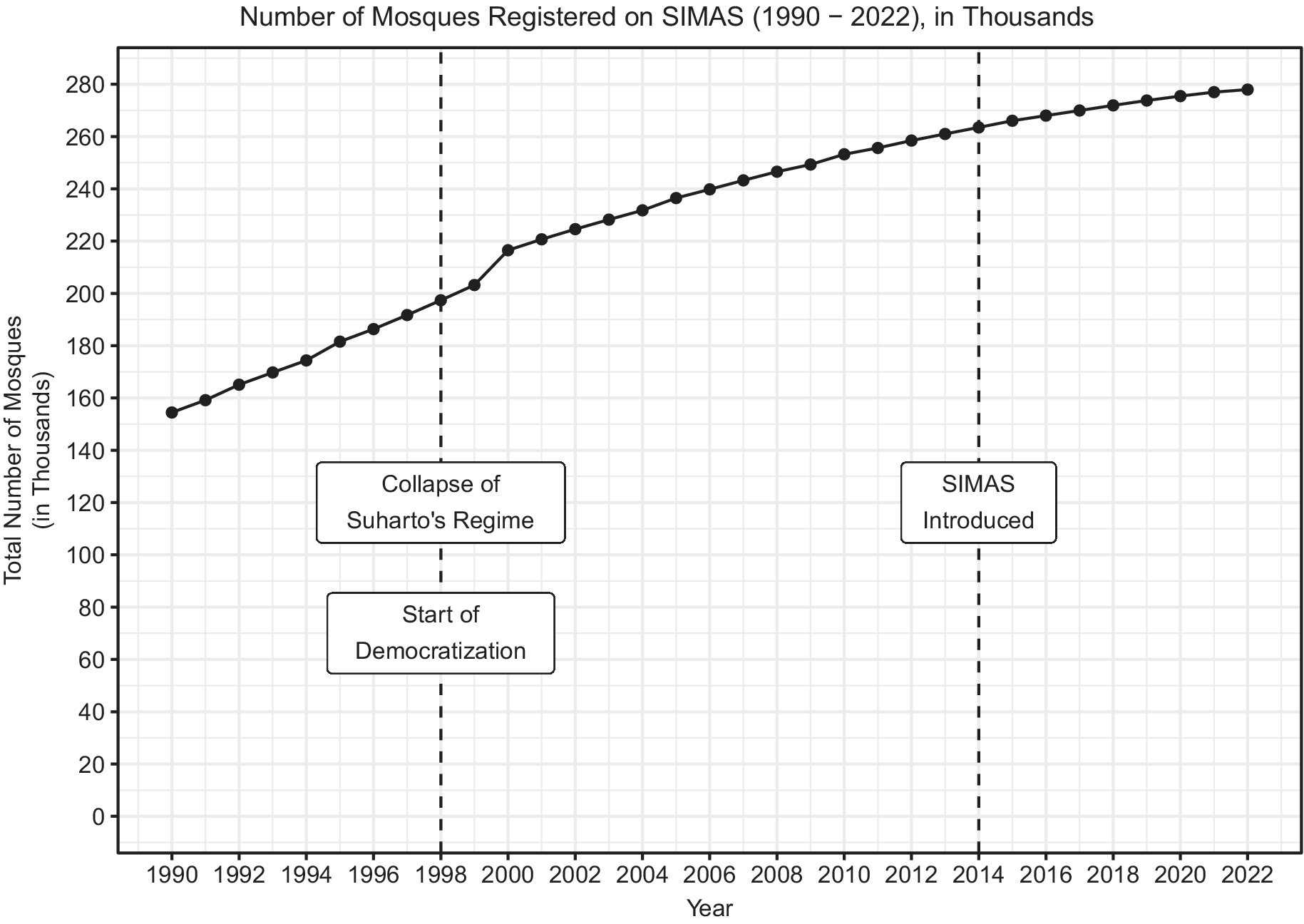

Figure 2 visualizes the growth in the number of mosques registered on SIMAS between 1990 and 2022. The database shows an 80% increase in the number of mosques in Indonesia between 1990 and 2022, compared to a 50% increase in the Indonesian population over the same period. It also reveals a notable surge in the number of mosques between 1998 and 2000, coinciding with the opening of Indonesia’s civic and political spheres, which contributed to the country’s “conservative turn” (van Bruinessen Reference van Bruinessen2013). In contrast, there was no noticeable increase around 2014, when SIMAS was introduced, indicating that the system’s introduction did not directly drive the registration of newly built mosques.

Figure 2 Growth in the Number of Registered Mosques (1990–2022)

The second dataset is Waves 4 and 5 of the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), fielded in 2007 and 2014, respectively. Designed to be representative of 83% of the Indonesian population, Wave 1 of IFLS was fielded in 1993 and contained information about 30,000 individuals living in 7,224 households. Subsequent waves tracked the same individuals and their new household members. Wave 4 includes records from 44,103 individuals living in 13,535 households, and Wave 5 includes records of 50,148 individuals living in 16,204 households.Footnote 2

The third dataset is derived from the 2010 census data, which I used to calculate various district characteristics, such as gender composition, religious composition, and educational attainment. These variables are included as covariates in some of the robustness check models and to examine the plausibility of the three mechanisms using interaction models.

Outcomes of Interest

I analyze 10 dependent variables that correspond to three categories of sociopolitical attitudes. The first category assesses Muslim respondents’ exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims. Questions in this category capture the extent to which respondents objected to people of a different religion living in the same village, living as neighbors, living in the same house, or building a house of worship in the village. Another question captures the extent to which respondents objected to interfaith marriage. All these variables are on a four-point scale ranging from no objection at all (1) to strong objection (4).

The second category captures political preferences. Respondents were presented with a list of factors and asked if they considered each factor important when deciding whom to vote for as regent (bupati) or city mayor. Two of the factors listed were religious similarity and ethnic similarity. Based on these questions, I created two binary variables: religious preference and ethnic preference. Respondents received a score of 1 on the corresponding variable if they mentioned religious or ethnic similarity as an important consideration and 0 otherwise.

The third category captures ingroup attitudes and good neighborliness. Respondents rated their agreements with three statements: (1) they were willing to help people in the village who needed help, (2) they trusted coreligionists more than those with different religions, and (3) they trusted co-ethnics more than people from different ethnic groups. Responses are on a four-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4).

Estimation Method

Consistent with the scope of community influence outlined earlier, I restrict the analysis to IFLS respondents who identified as Muslim and resided in the same Muslim-majority districts between 2007 and 2014. The effects of mosques should be constrained to those who neither moved out of nor into a district. Sample sizes vary slightly across model specifications, but these inclusion criteria provide us with more than 16,000 respondents living in more than 1,000 Muslim-majority districts.

I employ a difference-in-difference approach as the modeling strategy. The primary regression models can be expressed as:

The interaction term

![]() $ {b}_3 $

represents the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT).

$ {b}_3 $

represents the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT).

![]() $ {T}_i $

is a wave fixed-effect and takes the value of 1 if the observation comes from 2014.

$ {T}_i $

is a wave fixed-effect and takes the value of 1 if the observation comes from 2014.

![]() $ {D}_i $

is a treatment fixed-effect and takes the value of 1 if the respondent resided in a district with at least one new mosque between 2008 and 2013 (inclusive)—that is, between Waves 4 and 5 of the IFLS. About 16.2% of districts (175 of 1,080) had no new mosques. These districts accounted for 19.5% of analyzed respondents (3,164 of 16,238).Footnote

3

$ {D}_i $

is a treatment fixed-effect and takes the value of 1 if the respondent resided in a district with at least one new mosque between 2008 and 2013 (inclusive)—that is, between Waves 4 and 5 of the IFLS. About 16.2% of districts (175 of 1,080) had no new mosques. These districts accounted for 19.5% of analyzed respondents (3,164 of 16,238).Footnote

3

For brevity, I refer to districts with new mosques as “treated” districts and districts with no new mosques as “untreated” districts. This is not to suggest that there was a randomly assigned treatment. After presenting the results, I discuss challenges related to model specifications, placebo tests, and causal identification.

The primary regression models, one for each dependent variable, include no covariates to retain as many observations as possible and to present a transparent, bivariate relationship between the dependent variables and the presence or absence of new mosques. These models predict a dichotomized version of the dependent variables to facilitate the interpretation of effect sizes. For the four-point variables (i.e., every outcome variable except the candidate preference variables), responses of 3 and 4 are recoded as 1, and responses of 1 and 2 are recoded as 0. All models, including robustness check models, cluster the standard errors at the district level and are estimated in a multilevel framework with a random intercept.

Results

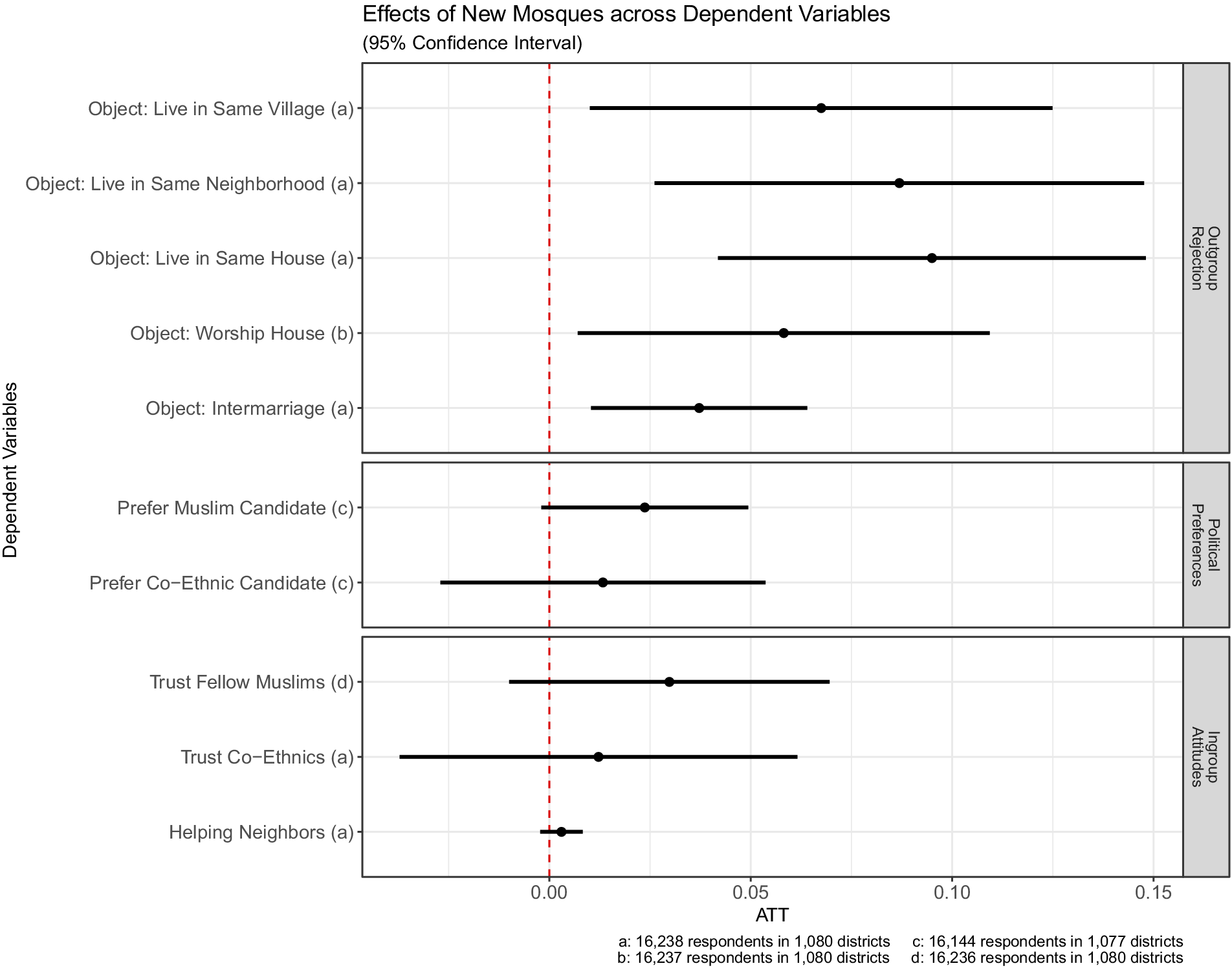

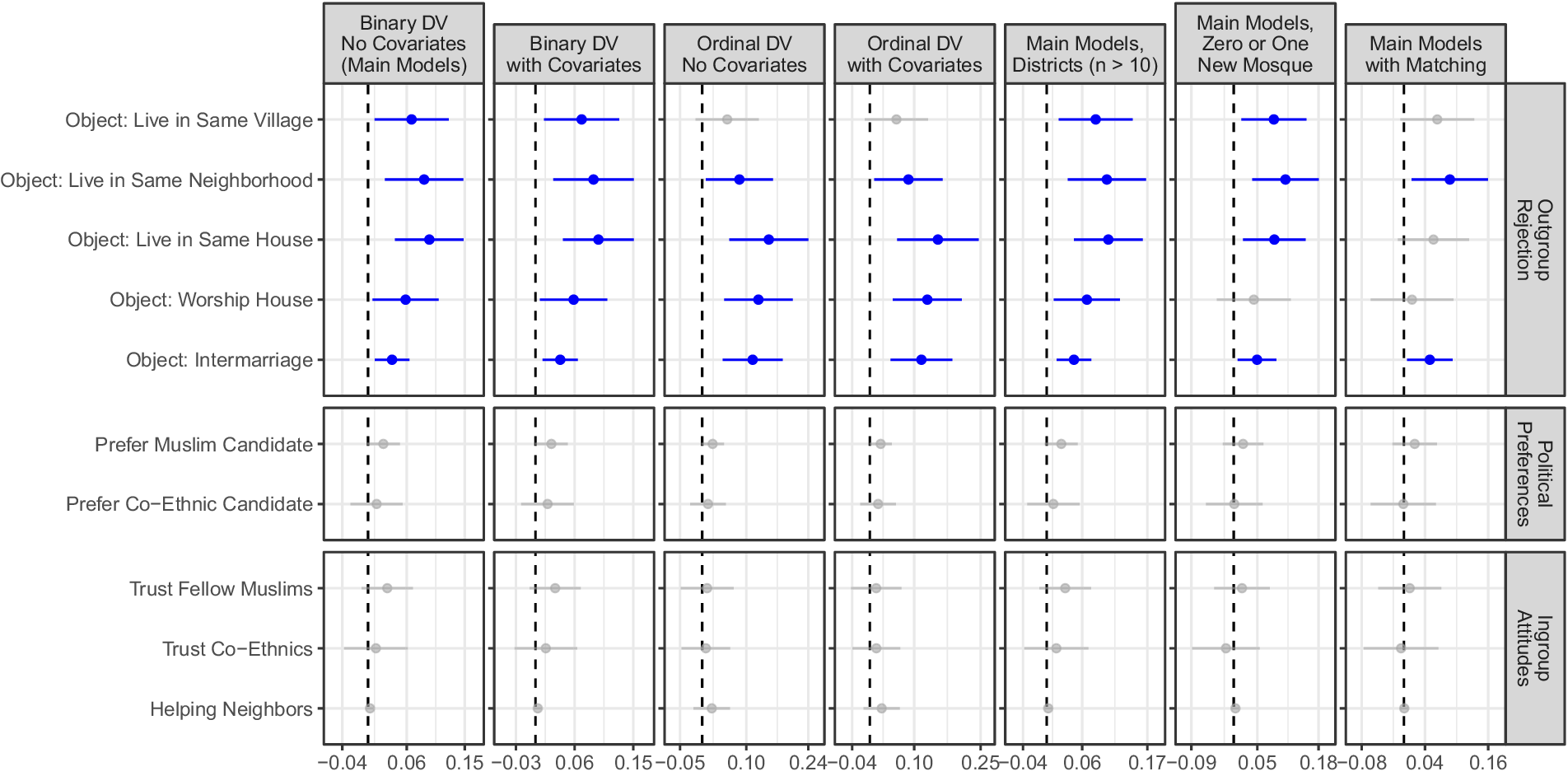

Figure 3 presents treatment effect estimates from 10 models corresponding to the 10 dependent variables. The presence of at least one new mosque is primarily associated with higher exclusionary attitudes. New mosques are associated with increased objections to non-Muslims living in the same village, the same neighborhood, and the same house as the respondent. New mosques are also linked to heightened objections to the presence of non-Muslim houses of worship in the village and to interfaith marriage.Footnote 4 To a lesser extent (marginally significant at p < .10), new mosques are associated with a stronger preference for Muslim candidates in elections. However, there is no evidence that new mosques shape political support and trust toward co-ethnics, trust toward fellow Muslims, or willingness to help neighbors in need. In other words, the effects of mosques are primarily related to exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims.

Figure 3 Estimated Treatment Effects of Mosques

Are these effects limited to attendees, or are they also evident in the broader community, including those who may not frequently attend mosques to pray―as the present study claims? The IFLS did not include questions that directly addressed how often respondents went to mosques to pray. However, mosque attendance can be reasonably proxied by two available questions: gender and attendance at communal prayers.

In Indonesia, it is uncommon for females to attend Friday prayers, so males are more likely to attend mosques. The second question, regarding attendance at communal prayers, asked respondents if they had attended a communal prayer in the neighborhood in the past 12 months. It is reasonable to suspect that those who are actively engaged in communal prayers are also more likely to go to mosques to pray.

In the online appendix, I find largely null evidence for gender effects—whether defined as the respondent’s gender or the proportion of males in a district—on conditioning the treatment effects. Not only are the effects statistically not significant but they also lack consistent directionality. However, there is some evidence for the role of engagement in communal prayers. The interaction effect is positive and statistically significant for objections to non-Muslims living in the neighborhood, suggesting that the effect of mosques on this dependent variable is stronger among individuals who attended past communal prayers. Other effects, although not statistically significant, consistently align in the same direction.

These findings suggest that even though the effects of mosques on some outcome variables may be stronger among individuals more likely to attend them, the overall lack of significant interaction effects demonstrates that community influence applies to both attendees and nonattendees. This supports the study’s argument that mosques shape sociopolitical attitudes not only among attendees but also within the broader communities they serve.

Robustness Tests

In this section, I outline results from placebo tests that examine whether the treatment (the presence of at least one new mosque) was necessary to observe the effects, as well as the results from regressions with different model specifications. I also discuss potential threats to causal identification and my approaches to address them.

I conducted three placebo tests to enhance confidence that the presence of new mosques indeed drives the results. The first placebo, an in-space placebo, restricts the analysis to 175 untreated districts that reported no new mosques between 2008 and 2013. I randomly “placed” new mosques in half of these districts, effectively creating a placebo treatment group to be compared to a true control group. Because the districts in this placebo treatment had no actual new mosques, no treatment effects should be observed.

The second placebo test, an in-time placebo, simulates as if the treatment had happened before 2007 (the pre-treatment wave). I define the placebo treatment as having at least one new mosque between 2000 and 2006. Because this placebo treatment was before the pre-treatment wave, new mosques during this period should not have any effects on the outcomes of interest, and we should not observe statistically significant treatment effects.

Lastly, the third placebo is an analysis of movers. It focuses on respondents who relocated from or to the districts studied between 2007 and 2014. Because these respondents were not fully present in the treated districts when the treatment occurred, we should not observe significant treatment effects.

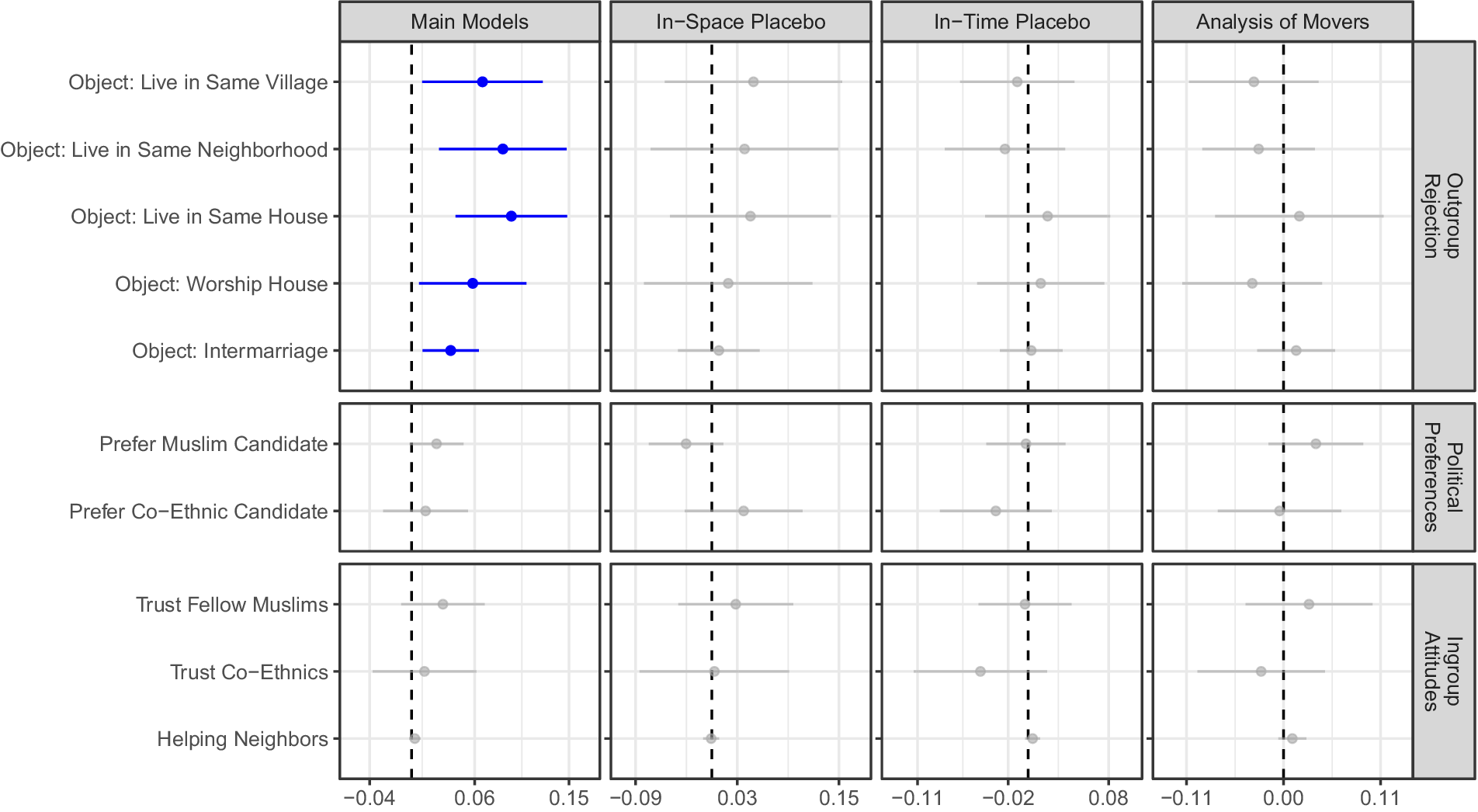

Figure 4 presents results from these placebo tests, with the full results available in the online appendix. The first column provides results from the main models as a comparison. Statistically significant effects are printed in thicker lines, whereas nonstatistically significant effects are grayed out. The results conform to the expectations. Unlike results from the main models, the placebo tests yield null findings, suggesting that there were no systematic changes in the outcome variables when the treatment itself was absent.

Figure 4 Pattern of Statistical Significance Across Placebo Tests

Alternative Specifications

To check how sensitive the findings are to modeling choices, I ran four alternative specifications. The first specification adds individual- and district-level covariates to the main models. The individual-level covariates include gender, age, level of education, self-rated religiosity, frequency of practicing salat (Islamic prayer), employment status, and marital status. Self-rated religiosity is measured with a question that asked the respondent how religious they considered themselves to be on a four-point scale of not very religious to very religious. Salat frequency is operationalized as a three-level categorical variable that records whether the respondent reported practicing salat less than five times a day, exactly five times, or more than five times a day.

The district-level variables include the logged number of mosques in the pre-treatment wave, as well as demographic and political covariates. The demographic covariates tap into whether the district is located on the Java island, the median age of the population, proportion of men in the population, proportion of the working population, the median level of education, proportion of Muslims, and language diversity, as calculated from the 2010 census.

The political covariates include the vote shares of Joko Widodo (Jokowi) in the 2014 and the 2019 elections and the vote share of Islamist parties in the 2019 national legislative election. The 2014 election data are based on the crowdsourcing website, kawalpemilu.org. The 2019 data were scraped directly from the electoral commission’s website. Because the elections were characterized by polarization, with nationalist parties supporting Jokowi and Islamist parties backing his opponent Prabowo Subianto, these three variables serve as indicators of the strength of Islamist sentiments at the district level.

The second alternative specification uses the original scales of the variables but excludes the covariates. All the outgroup rejection and the ingroup attitudes variables are on a 4-point scale, whereas the two political preferences variables are still binary. The third alternative specification combines the first and the second specifications. It analyzes the outcome variables on their original scales while including the aforementioned covariates.

The fourth specification accounts for the fact that the distribution of respondents across analyzed districts is right-skewed. Of 1,080 analyzed districts, 815 (75%) have 10 or fewer respondents. The perceptive reader might wonder whether these districts with few respondents disproportionately affect the results. This fourth specification therefore analyzes only 265 districts with more than 10 respondents.

The first five columns of figure 5 present estimates of treatment effects from these alternative specifications, with the full regression results available in the online appendix. Results from the main models are presented on the first column as a reference. Statistically significant effects are printed in thicker lines, whereas effects that are not statistically significant are printed in gray. The patterns are very similar across these different specifications. The presence of at least one new mosque is positively correlated with higher outgroup rejection but unrelated to the other outcome categories.

Figure 5 Pattern of Statistical Significance Across Model Specifications

Threats to Causal Identification

The placebo tests and the alternative specifications demonstrate both that there are no treatment effects when the treatment itself is absent and that the results are not sensitive to modeling specifications. However, two concerns related to causal identification remain that need to be discussed on their own. The first relates to treatment spillover, and the second relates to potential consequences of pre-treatment differences between treated and untreated districts.

The concern regarding treatment spillover suggests that respondents may not necessarily frequent mosques in their own districts, opting instead to visit mosques outside their districts. In such cases, the implementation of the treatment may not be entirely clean, and the estimated effects of mosques could be biased. This concern is possible, but arguably, any bias emerging from it would lead to an underestimation of the effects.

This downward bias results from respondents in treated districts who attended mosques in untreated districts or from respondents in untreated districts who attended mosques in treated districts. The first scenario would underestimate the treatment effects by lowering the averages of the treated districts, whereas the second scenario would underestimate the effects by inflating the averages of the untreated districts.

The concern regarding pre-treatment differences suggests that the observed effects might have been driven by preexisting differences between treated and untreated districts, rather than by the presence or absence of new mosques. To assess the plausibility of this concern, I conducted three additional analytical exercises.

The first exercise examines the parallel trends assumption of the difference-in-differences approach. The approach does not assume strict covariate balance as in a randomized experiment; it only requires treated and untreated units to have parallel trends on the outcome variables. However, it is not possible to explicitly test this assumption because the IFLS data used consist of only two waves. As an alternative, I analyze the number of violent incidents recorded in the National Violence Monitoring System (NVMS). Such incidents serve as indicators of the districts’ general susceptibility to violence and social tensions. If the treated districts already have an upward trend in violent incidents, then the treatment effects may simply reflect this trend and not the effects of mosques. In the online appendix, I show that such an upward trend did not exist and that the treated and untreated districts generally have parallel trends.

The second exercise narrows the definition of treated districts to having exactly one new mosque. If the likelihood of having new mosques is correlated with existing characteristics, focusing on districts with zero and one new mosque provides us with a set of districts that are more comparable. This exercise also allows us to address the possibility that the results are driven by a few districts with extremely high numbers of new mosques. Under this specification, attitudinal changes of 3,164 respondents in 175 untreated districts were compared to attitudinal changes of 1,920 respondents in 154 treated districts.

The third exercise pre-processes the data with a propensity score matching and analyzes only districts with common support. I define untreated districts as districts with no reported new mosques and treated districts as districts with exactly one new mosque. The matching procedure included as covariates all the aforementioned control variables and all the pre-treatment values of the dependent variables. The covariate balance before and after the matching and the distribution of propensity scores are available in the online appendix.

The last two columns in figure 5 present results from these second and third exercises. Even after limiting the data to districts with either zero or one new mosque and after pre-processing it with a matching method, we still have the same patterns of effects as the main models. New mosques are related to increased rejection of non-Muslims, but not to political preferences or ingroup attitudes.

To sum up, each modeling approach outlined earlier, on its own, is limited by various constraints. However, three placebo tests demonstrate that there are no effects without new mosques, and six alternative specifications provide little indication that the results are model-dependent. Combined with what studies have found on how preexisting exclusionary attitudes in Muslim-majority districts should manifest themselves more in rejections of non-Islamic places of worship, rather than in the building of new mosques (Ali-Fauzi et al. Reference Ali-Fauzi, Samsu Rizal Panggabean, Sumaktoyo, Husni Mubarak and Nurhayati2011; Crouch Reference Crouch2010), these findings, in turn, should add confidence to the reliability of the main results.

Probing Potential Mechanisms

Having obtained evidence for a broader political significance of mosques―that they shape exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims in the community―a natural follow-up question arises: through what mechanism do they exercise this effect?

As discussed in the literature review, there are three potential mechanisms: the confessional, psychosocial, and information mechanisms. No direct measures of these mechanisms are available in the analyzed datasets. Instead, I assess the relative influence of each explanation indirectly by deriving observable implications and testing these implications against the data. I consider this indirect approach to be more exploratory than the regressions in the previous sections, where I directly tested the hypothesis regarding community influence. The goal of probing the mechanisms is not to rule out some explanations as implausible but to assess which factors and processes are more closely related to or responsible for the effects of mosques.

Confessional Mechanism

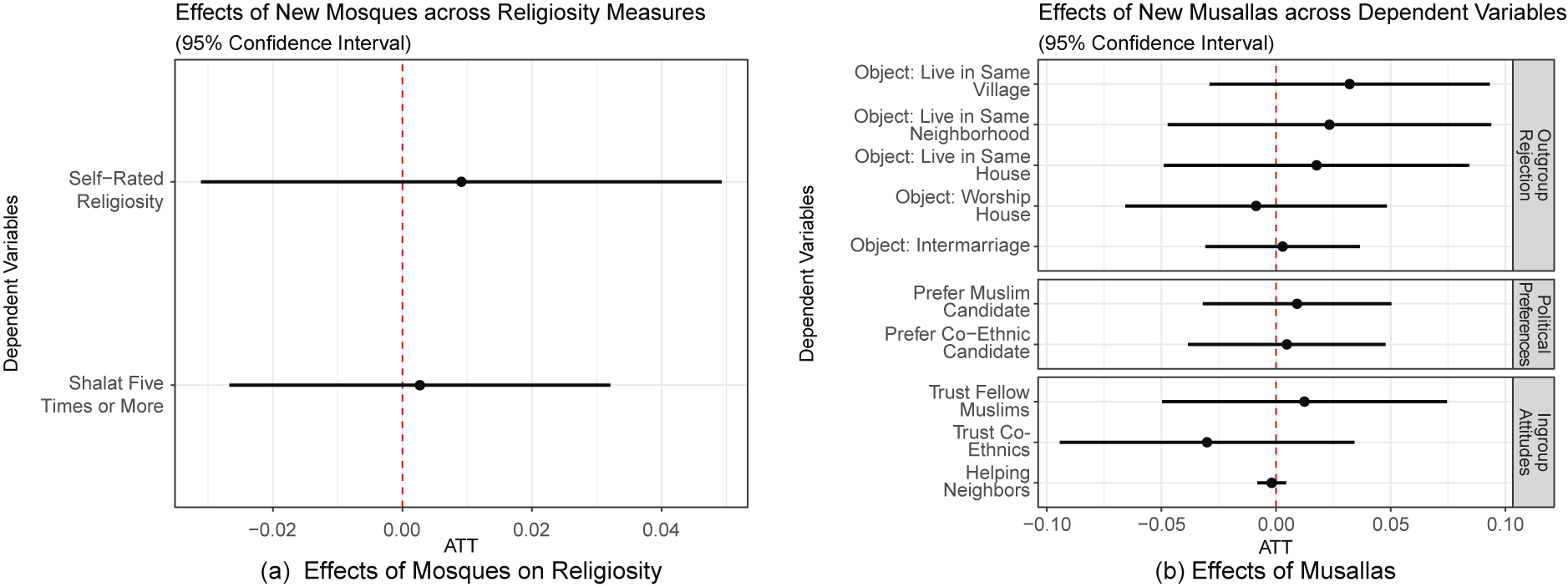

The confessional mechanism suggests that houses of worship influence sociopolitical attitudes in the community by shaping its level of religiosity. This suggests that we should expect new mosques to influence measures of religiosity, such as self-perception of religiosity and adherence to the obligatory five daily salat. Panel (a) of figure 6 presents the effects of new mosques on the predicted probabilities of respondents considering themselves religious and reporting practicing salat five or more times daily. None of the effects are statistically significant, suggesting that new mosques do not necessarily make individuals more religious.

Figure 6 Tests of the Confessional Mechanism

Notes. Panel (a) shows that new mosques do not correlate with higher reported religiosity. Panel (b) shows that musallas have no effects on the outcomes of interest. Together, these findings offer limited evidence for the confessional mechanism.

There is another observable implication of the mechanism. If the confessional mechanism is supported, then we should see similar effects when we substitute mosques with musallas. As mentioned earlier, musallas, like mosques, provide a space to pray but are much smaller and therefore can only accommodate fewer functions. If what matters is personal piety, then musallas as a place to pray should exert the same effects as mosques.

Panel (b) of figure 6 presents the effects of new musallas built between 2008 and 2013 (inclusive) on the outcomes of interest. I follow the same specification as the main models, except that mosques are now replaced with musallas. Unlike figure 3 that shows mosques significantly shaping measures of outgroup rejection, panel (b) of figure 6 shows no statistically significant treatment effects of musallas. These results, in turn, offer little evidence for the roles of confessional mechanism in explaining the observed effects of mosques on outgroup rejection.

Psychosocial Mechanism

The psychosocial mechanism emphasizes the importance of houses of worship in cultivating social networks and fostering group identity and cohesiveness. If this mechanism is supported, we should observe the magnitudes of the treatment effects to vary depending on individual- and district-level characteristics related to group identification. I specifically test six hypotheses derived from this prediction.

The first hypothesis uses variation in the interview day (Brooke, Chouhoud, and Hoffman Reference Brooke, Chouhoud and Hoffman2023). If networks and group identification drive the observed effects, then the effects of mosques should be stronger among respondents interviewed on a Friday, the day when Muslims attend mosques for Friday prayers and congregate with fellow believers. I created a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if the respondent was interviewed on a Friday and 0 otherwise. This variable is available in both pre- and post-treatment waves.

The second hypothesis concerns affiliations with Muslim organizations. If mosques shape attitudes through networks and group identity, then the effects should be stronger among those with strong and dense religious networks. I take advantage of a question in the post-treatment wave that asked respondents which Islamic organization they felt closest to. I focus on the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and the Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s two largest Muslim organizations.

Scholars often portray these organizations as moderate—though not liberal—and emphasize their commitment to democracy as a key factor in the country’s relative democratic resilience (Hefner Reference Hefner2011; Menchik Reference Menchik2016). Their deep societal roots ensure that individuals identifying with these organizations are embedded in their community networks. Among the respondents analyzed, 78% indicated feeling close to one of the two organizations, whereas 22% either reported no identification or identified with other groups. Respondents were assigned a value of 1 if they identified with NU or Muhammadiyah and a value of 0 if they either did not identify with any Islamic tradition or identified with another organization.Footnote 5

The third to sixth hypotheses concern district characteristics. The third hypothesis examines whether the effects of mosques on outgroup rejection are stronger in districts that are more religiously homogeneous. Religiously homogeneous communities are conducive for the development of intragroup ties that facilitate group attachment and exclusionary attitudes (Sumaktoyo Reference Sumaktoyo2021). If the exclusionary effects of mosques are due to the psychosocial mechanism, then we should observe these effects to be stronger in districts with higher proportions of Muslims. For this purpose, I calculated the proportion of Muslim population in each district based on the 2010 census.

The fourth hypothesis probes whether the effects of mosques are stronger in districts with higher proportions of waqf mosques. As Bazzi, Koehler-Derrick, and Marx (Reference Bazzi, Koehler-Derrick and Marx2020) note, waqf strengthens religious institutions at the expense of the state. With waqf lands, religious institutions have the capital to promote their ideology and strengthen their organizations. Accordingly, we should observe the effects of mosques to be stronger in districts with higher proportions of waqf mosques.

The fifth hypothesis explores whether the effects of mosques are stronger in districts with higher numbers of pre-treatment mosques. A higher number of mosques may indicate stronger religious identity and a more extensive religious network, potentially amplifying the effects of new mosques on exclusionary attitudes.

The sixth hypothesis, a derivative of the third one regarding Muslim organization identification, posits that if the psychosocial mechanism is significant, then the effects of mosques should be more pronounced in districts with higher percentages of respondents identifying with NU or Muhammadiyah.

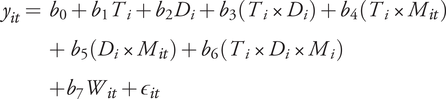

I test these predictions through three-way interaction models. For each prediction, I interacted the treatment effect in Equation (1) with the relevant moderating variable. I also included all covariates used in the alternative specifications and all lower-order interaction terms. The equation is presented as Equation (2) where

![]() $ W $

is a vector of individual- and district-level covariates and

$ W $

is a vector of individual- and district-level covariates and

![]() $ M $

is the moderator of interest. For moderators that were only measured once, I set their values to be the same in both pre- and post-treatment waves. The regression coefficient of interest would be

$ M $

is the moderator of interest. For moderators that were only measured once, I set their values to be the same in both pre- and post-treatment waves. The regression coefficient of interest would be

![]() $ {b}_6, $

which indicates whether the treatment effect varies by levels of the moderator.

$ {b}_6, $

which indicates whether the treatment effect varies by levels of the moderator.

$$ {y}_{it}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{b}_0+{b}_1{T}_i+{b}_2{D}_i+{b}_3\left({T}_i\times {D}_i\right)+{b}_4\left({T}_i\times {M}_{it}\right)\\ {}+\hskip2px {b}_5\left({D}_i\times {M}_{it}\right)+{b}_6\left({T}_i\times {D}_i\times {M}_i\right)\\ {}+{b}_7{W}_{it}+{\epsilon}_{it}\end{array}} $$

$$ {y}_{it}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{b}_0+{b}_1{T}_i+{b}_2{D}_i+{b}_3\left({T}_i\times {D}_i\right)+{b}_4\left({T}_i\times {M}_{it}\right)\\ {}+\hskip2px {b}_5\left({D}_i\times {M}_{it}\right)+{b}_6\left({T}_i\times {D}_i\times {M}_i\right)\\ {}+{b}_7{W}_{it}+{\epsilon}_{it}\end{array}} $$

Figure 7 shows that none of the interaction effects are statistically significant. This finding is also consistent with the main models in figure 3, which detect no effects of mosques on trust toward fellow Muslims.

Figure 7 Interaction Effects with Psychosocial Variables

Information Mechanism

The information mechanism highlights the role of houses of worship as channels of communication and information. In addition to cultivating religiosity or fostering networks and group identity, houses of worship also impart information that influences individuals’ worldviews. Two observable implications of this mechanism are that the effects of houses of worship should be weaker among individuals with access to multiple sources of information (thus diluting the impact of any single source) and among those who can critically evaluate information. I translated these implications into four hypotheses.

First, we should observe the exclusionary effects of mosques to be weaker among individuals with higher education. Education is “a universal solvent” (Converse Reference Converse, Campbell and Converse1972, 324). As individuals move up the education ladder, they accumulate more knowledge about the world around them (Carpini and Keeter Reference Carpini and Keeter1997); more importantly, they learn how to think.

Education helps people develop analytical thinking, which is necessary to integrate and critically evaluate information. It promotes cognitive sophistication in which information is not merely absorbed but also scrutinized and compared to other information. One of the reasons why education leads to political tolerance is because it cultivates cognitive sophistication and a critical approach to information (Bobo and Licari Reference Bobo and Licari1989).

Yet, education influences not only how people think but also their social standing (Campbell Reference Campbell2009; Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik-Barry1996). Higher levels of education situate individuals in more central positions within society and their networks. This network centrality yields greater social influence and access to wider sources of information.

To test this hypothesis, I interacted the treatment effect with the respondent’s level of education as moderator. The level of education is recorded as a six-point scale of no schooling, grade school, junior high, senior high, college or university, and postgraduate degree. This variable is available in both waves.

The second and the third information hypotheses aim to tease out the effects of education on strengthening cognitive ability and on diversifying information sources. The second hypothesis tests whether the effects of mosques are weaker among respondents with higher cognitive ability. The post-treatment wave includes a battery of questions adapted from the Health and Retirement Study intended to measure cognitive ability (Strauss and Witoelar Reference Strauss, Witoelar, Gu and Dupre2019). Among other questions, the battery asked respondents to predict a series of numbers and mention as many animals as possible within 60 seconds.

Because the variable aims to measure “fluid reasoning” (Strauss and Witoelar Reference Strauss, Witoelar, Gu and Dupre2019, 3), it allows us to test the roles of cognitive ability more explicitly than simply using education level. To operationalize this variable, I use the psychometric score calculated by the IFLS team (Blankson and McArdle Reference Blankson and McArdle2014).

The third hypothesis tests whether the effects of mosques are weaker among respondents with more diverse information sources, regardless of education level. I take advantage of five IFLS questions that tap into potential information sources. The first question, which is in the post-treatment wave, asked the respondent whether they owned a TV. The second and third questions asked the respondent whether they used their cellphones to access the internet and the social media. The fourth and five questions, fielded in both the pre- and the post-treatment waves, asked the respondent whether they could read newspapers in Indonesian or in their local language. I combine these two newspapers questions into one indicator that takes a value of 1 if the respondent was able to read in either language and 0 otherwise.

To operationalize the information source variable, I calculated how many of these four information sources (TV, internet, social media, and newspapers) the respondent had access to. The score of this variable ranges from 0 to 4. The more a respondent had access to these sources, the less reliant they should be on their neighborhood mosques to provide them with information. As such, the effects of mosques on exclusionary attitudes should be weaker among respondents with access to more information sources.

The fourth information hypothesis extends the first hypothesis to the district level. If the role of mosques as channels of communication and information drives the exclusionary effects, these effects should be weaker in districts with higher levels of education. To measure education, I use the districts’ median education levels from the 2010 census. The district-level education variable is based on the same six-point scale as the individual-level education variable, ranging from no schooling to a postgraduate degree.

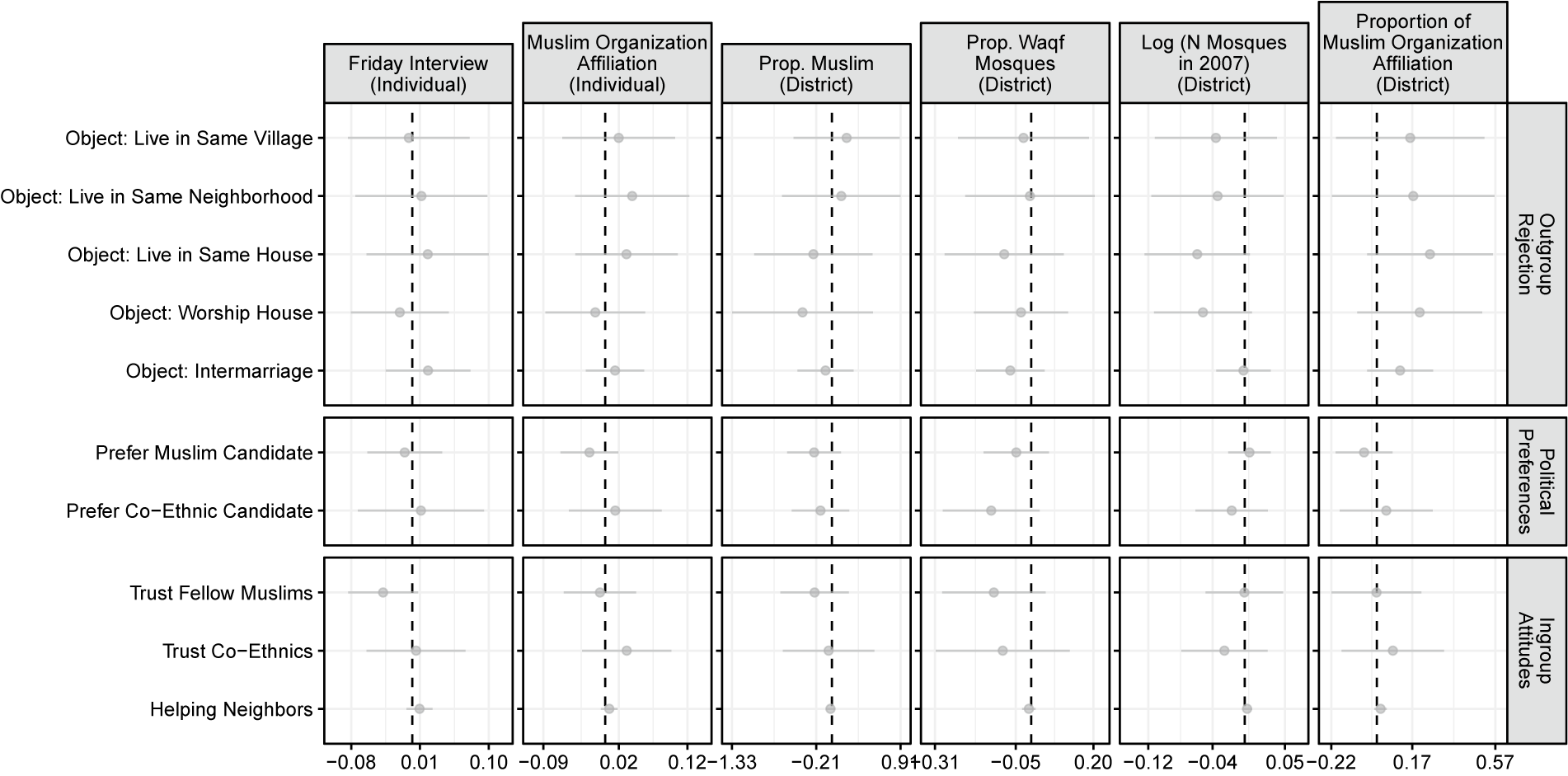

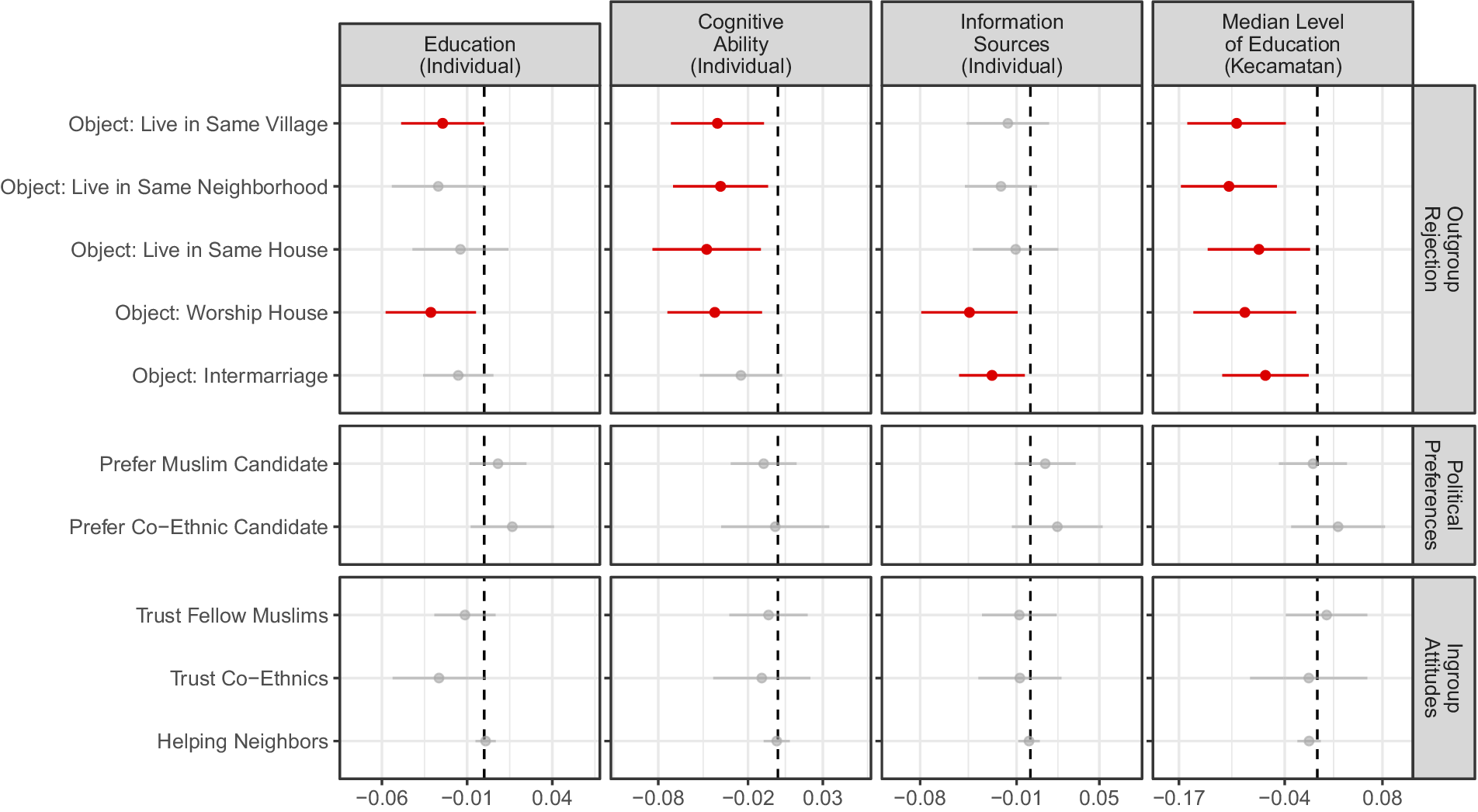

I test these hypotheses using the same specification as that used for the psychosocial hypotheses (Equation 2), with the results presented in figure 8. Unlike the confessional and psychosocial mechanisms, there is evidence that the four moderators related to information processing and alternative information sources significantly condition the effects of mosques. The effects of mosques on outgroup rejection are notably weaker among respondents with higher education, higher cognitive ability, and access to more alternative sources of information. These effects are also weaker in districts with higher education levels.

Figure 8 Interaction Effects with Information Variables

Notes. Higher education, stronger cognitive ability, and alternative sources of information are associated with weaker effects of mosques on exclusionary attitudes. The effects of mosques are also weaker in districts with higher education.

Discussion

Analyzing location data of more than 300,000 mosques in Indonesia and panel data on the sociopolitical attitudes of more than 16,000 Muslim respondents, I demonstrate that the presence of new mosques in a kecamatan (district) correlates with exclusionary attitudes toward non-Muslims among residents. I also find that the effects are conditioned by individual- and district-level factors that tap into the ability to critically evaluate information and access to multiple information sources, suggesting that the roles of mosques as an important source of information within the community significantly contribute to the effects documented.

This evidence, supportive of the information mechanism, should not be interpreted as conclusive evidence against other mechanisms, given the indirect nature of variables used in the analysis. Measurement errors and construct reliability remain potential reasons for the nonsignificance of the confessional and the psychosocial mechanisms. Future studies would benefit from using more direct measures to test these mechanisms. Survey questions are an obvious choice; however, behavioral measures such as the amount of almsgiving (zakat) or the actual number of communal prayers in the neighborhood may offer greater real-world validity.

Future studies may further enhance our understanding of community influence by exploring other potential mechanisms. One particularly interesting mechanism relates to social desirability. It is plausible that, rather than cultivating or strengthening exclusionary attitudes, new mosques create a space that allows existing exclusionary attitudes to be expressed more openly. The observable outcome would be similar to what this article has documented: an increase in exclusionary attitudes in treated districts. This mechanism is similar to how Trump, Modi, or other right-wing political leaders create a condition that enables their supporters to express anti-minority sentiments (Jardina and Piston Reference Jardina and Piston2023; Varshney and Staggs Reference Varshney and Staggs2024).

The IFLS lacks variables necessary to convincingly test this possibility, and exploring this mechanism would require a specialized research design. For instance, researchers could conduct a list experiment or an endorsement experiment in a sample of districts with varying numbers of mosques and examine how the magnitudes of the treatment effects vary across the number of mosques.

In addition to the question of mechanisms, generalizability is an important issue. How generalizable are the findings presented here? We can approach the question of generalizability from three perspectives: generalizability in relation to Indonesian political dynamics, generalizability in terms of other outcome variables, and cross-country generalizability. In terms of generalizability in relation to Indonesian political dynamics, despite the analysis being focused on the period between 2007 and 2014, I argue that the findings should be applicable to other years in post-Suharto Indonesia, including the years of Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi) administration.