Things seemed different on a spring day in 2016 when I walked into a humanitarian international nongovernmental organization (INGO) office in Beirut. I had been observing activities over the past few weeks there, but today the organization’s mostly local staff were not wearing their customary jeans and t-shirts, desks were tidied, and there was little conversation. The office receptionist rushed to greet me at the door and to tell me “the donors” were there. As an international visitor, I was politely introduced to two donor agency representatives, who I was told would soon depart for a field visit. INGO leaders had previously spoken to me with confidence, discussed their frustrations about donor priorities and blindness to operational challenges, and greeted these with the occasional joke. In that room they were formal and deferential to the donor agency representatives. The quiet that had fallen on the office remained for just a little while after “the donors” headed out in a convoy of INGO cars for the day.

This encounter occurred five years after the 2011 war in Syria had broken out and triggered the largest funded humanitarian response in history—that is, until response to the war in Ukraine broke new records. The largest donors to the Syrian refugee response in the neighboring host states of Lebanon and Jordan were the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. However, funding by top humanitarian donors quickly peaked in Jordan in 2013 and in Lebanon in 2014. The subsequent decline was significant. These donors together had funded 53% of the United Nations Syria Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan (3RP) appeal in Jordan in 2013 and 55% in Lebanon in 2014. By 2016, they were funding just 33% of the appeal in Jordan and 44% in Lebanon (UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS) 2017; see online appendix A). This decline occurred despite the UN’s appeal for more funds to meet the needs of Syrians living through protracted crisis.

Meanwhile, the war in Syria had heightened features typical of complex modern humanitarianism, including conflict, record displacement, and need, putting a great deal of pressure on humanitarian organizations. Describing the intertwined nature of funding and security pressures in the region (see Scott Reference Scott2022a; Bagshaw and Scott Reference Bagshaw and Scott2023), an INGO aid worker in Tripoli Lebanon said,

There’s been a budget cut this year and there’s a certain amount of chopping away at dead wood type thing going on. So, I mean that’s almost what they’re doing, kind of pruning the tree and making sure resources are in the right places. And, given that the region is in such a poor state, it’s descending into a warzone from Turkey all the way to Iran, and then all the way pretty much throughout Syria and Iraq. There’s just kind of one area of conflict … and then you’ve got Yemen. You’ve got Israel, Palestine. You’ve got—Lebanon’s always apparently sort of on the edge…. There’s a certain amount of angst about where resources should be allocated. And it also rises costs. And so, you have to kind of be focused on stability in funding.Footnote 1

At this time, donors also aimed to reduce overhead, capacity building, and management costs by bringing down the number of partners they funded. They reported “consolidating our portfolio in terms of partners” and funding “channeled through fewer partners.”Footnote 2

According to much of the existing literature, this funding decline—both in terms of the size of the total funding pie and the number of contracts—should have made humanitarian organizations more willing to do the bidding of donors who held the purse strings. They should have been more apt to concede to donor demands as they vied for limited contracts amid relative funding scarcity and increased marketization—greater reliance on competitive, renewable contracts to secure funding. The kind of deference I observed that day in an INGO office in Beirut should have been increasingly commonplace. However, this was not the case. Although competition for funds increased, many aid workers instead described feeling independent from donor influence. They said, for instance, “I don’t know what’s going on up in the clouds, in the donor world”Footnote 3 and “It is a privilege that we don’t need to think of money being in the field. It gives you even more freedom and everything.”Footnote 4 Some aid workers went so far as to describe being able to lead donors. One stated of his work in Syrian refugee response, “We undertake humanitarian need-based, ambitious projects with the self confidence that donors will follow.”Footnote 5

How can we understand this apparent contradiction between expectations and reality? What explains aid worker feelings of independence at a time when funding was contracting and competition for those funds was increasing? And why were INGOs not scrambling and feeling beholden to donors, as is now commonly expected by scholars? Building on theories of organizational behavior, resource dependence, culture, and practice in international relations and development studies, this article investigates the unexpected ways that INGOs can gain autonomy from and even influence over donors. It examines a puzzle of unexpected delegation and autonomy in the case of INGOs operating among Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. This occurs when donors delegate more decisional authority to contracted INGOs than their dependence on those donors would lead us to expect: INGOs either maintain autonomy within traditional principal-agent relationships with donors or by stepping outside these contracted relationships entirely. In the latter case, the INGO has become sufficiently independent to be able to refuse a donor contract.

Research draws on more than 120 semi-structured interviews with donor relations and operations staff, as well as over 10 months of political ethnography and content analysis of organizational documents, predominantly at three large, long-established INGOs working among Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan in 2016 and 2017—the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and Save the Children International (SCI)—with supplemental research conducted at additional INGOs as shadow cases.Footnote 6 It explores relationships between INGOs and donors during responses to refugee needs in host states of Lebanon and Jordan between 2011 and 2017, as well as the historical evolution of INGO–donor relations more broadly.

In a theory-building exercise, this article presents “negotiation experience” as an important and underresearched factor that is defined as the development of key bargaining strategies, skills, and tools to resist external demands. It enables organizations to mitigate the effects of resource dependence on organizations, even when they require state donor funds to continue operations. Experienced negotiators promote resistance to external actors in their culture, strategies, and day-to-day practice and hire and reward staff who demonstrate related skills. Notably, these are mutually reinforcing, co-constitutive dynamics: Organizations develop as negotiators both (1) because they nurture strategies, skills, and tools that support organizational autonomy and (2) because these strategies, skills, and tools become increasingly valued and promoted when an organization’s culture prizes autonomy. Organizations with negotiation experience are better able to develop and leverage their own advantages—for instance, their specialization in a particular area or their ability to speak publicly with authority—over donors and gain autonomy than their less experienced competitors. They shape relationships with donors over time, as well as the amount, conditionality, and diversity of funding they accept. Notably, INGO pathways to becoming experienced negotiators and improving their relative autonomy are not uniform, linear, or unidirectional. However, for humanitarian organizations, experience is often gained in operational and security practice, with strategies and skills learned by their donor relations branches informally and through demonstration.

Contrary to dominant thinking that commonly portrays INGOs as scrambling for donor funding (Cooley and Ron Reference Cooley and Ron2002), INGO autonomy can exist alongside funding cuts. My findings have significant implications. First, they reveal that organizations themselves often value autonomy, which scholars expect to be key to INGO reputation (Lake Reference Lake2010) and effectiveness (Barma, Levy, and Piombo Reference Barma, Levy and Piombo2020; Honig Reference Honig2018). They capture surprising, perverse effects of INGO donor-following behaviors and funding capture on INGO autonomy, which can direct attention away from valuing operational and strategic autonomy and developing the skills and capacities needed to gain and keep it. Second, these findings contribute to the study of resource dependence and to critical questions about who holds power in humanitarianism and over conflict-affected populations and why (Fassin Reference Fassin, Feldman and Ticktin2010; Feldman and Ticktin Reference Feldman and Ticktin2010; Pincock, Betts, and Easton-Calabria Reference Pincock, Betts and Easton-Calabria2020). Findings contribute to understandings of the mutual dependence of INGOs and donors. Third, they add to what we know about the abilities of INGOs to “resist and even reverse the direction of influence” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014, 74) in their dealings with donors (Cooley and Ron Reference Cooley and Ron2002; Heiss and Kelley Reference Heiss and Kelley2017) and to reshape the institutional and resource arrangements around them (Dellmuth and Bloodgood Reference Dellmuth and Bloodgood2019; Heiss Reference Heiss2019).Footnote 7 Negotiation experience and identified tactics help INGOs moderate the impacts of factors—such as funding diversification, specialization, and mandate or issue-area expertise—found in extant literatures on autonomy. In so doing, research findings complement scholarship that shows INGOs have incentives “to downplay their influence” (Stroup Reference Stroup and Davies2019, 39) and oversimplify or overemphasize the role of external forces in shaping what they do (Gerstbauer Reference Gerstbauer2010; Najam Reference Najam2000). These behaviors help INGOs sidestep responsibility for bad outcomes and complicate efforts to evaluate them and hold them accountable (DeMars and Dijkzeul Reference DeMars and Dijkzeul2015).

The article proceeds in five sections. I review approaches in international relations and development studies to INGO agency and autonomy, identifying a need for further exploration of the ways that organizations strategically resist donor demands. Second, I outline this study’s research design, methods, and case selection before discussing the factors expected to influence autonomy and how they are measured across three selected cases. I then conceptualize negotiation experience. I next present findings from three INGO case studies that illuminate how variations in negotiation experience shape INGO autonomy from donors.

INGO Agency and Autonomy

Organizational autonomy refers to an actor’s “collective decision rights, or discretion” over its strategic and operational decisions (Arregle et al. Reference Arregle, Dattée, Hitt and Bergh2023, 86; Pennings Reference Pennings1976; Puranam, Singh, and Zollo Reference Puranam, Singh and Zollo2006),Footnote 8 distinct from those taken by a principal actor.Footnote 9 Autonomy can be conceptualized as the independence to pursue set goals or agendas (operational autonomy) or independence in goal or agenda setting (strategic autonomy) or both (Arregle et al. Reference Arregle, Dattée, Hitt and Bergh2023; Lumpkin, Cogliser, and Schneider Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009). In INGO–donor relations, autonomy refers to the range of actions an INGO can potentially take based on its own motivations and values, after the donor sets control mechanisms; it is the INGO room to maneuver. For example, control is exerted not only through contracts that mandate INGO reporting or donor oversight through visits to the field but also through calls for proposals (CFPs) that set expectations about what activities might be funded. The former is an instance of donor control of an INGO’s freedom to pursue or implement its goals (its operations). The latter is an instance of limiting the scope or scale of INGO goals and activities (its strategies). Notably, this understanding recognizes that INGOs and donors continue to influence one another and maintain communications between or outside contracts; that is, the INGO–donor relationship is not only contractual. Measures of autonomy are discussed in the section on the research design.

At issue when discussing autonomy is the INGO’s capacity to self-govern and control how, when, where, and to whom aid will be distributed (Feinberg Reference Feinberg and Christman1989; Hawkins and Jacoby Reference Hawkins and Jacoby2006; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2000). For this reason, questions about if and how governments direct the activities of international NGOs and what autonomous space they have available to make independent choices motivate a crucial piece of the literature on organizational behavior. ECOSOC (1950) defines a nongovernmental organization as “any international organization, which is not established by intergovernmental agreement.” However, some INGOs still “receive the bulk of their resources from public coffers” (Gordenker and Weiss Reference Gordenker and Weiss1995, 361) and are highly dependent on public state funds. Meanwhile, international organizations, including INGOs, are often asked by states to carry out a particular function because collective action problems make it difficult for states to do so alone.

Dependence emerges when “the environment retains all choices and organizations have none” (Barnett Reference Barnett2009, 621; see also Salancik and Pfeffer Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978), leaving little room for INGO agency. The conventional wisdom of the resource dependence (RD) tradition is that states give funds in exchange for the power to direct aid activities, but to varying degrees (Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Bush Reference Bush2015; Lancaster Reference Lancaster2008; Svensson Reference Svensson2000). RD theories at their simplest suggest INGOs will try to reassure donors that they are more desirable contractors than others by increasing their follower behaviors vis-à-vis donors, especially under conditions of resource scarcity (Cooley and Ron Reference Cooley and Ron2002; Edwards and Hulme Reference Edwards and Hulme1996; Rauh Reference Rauh2010).

Drawing on principal–agent theory (PAT), Cooley and Ron (Reference Cooley and Ron2002) argue that, as competition in the political economy of aid increases, rational organizations are more likely to compete for donor state contracts and to follow donor demands. The growing marketization of aid funding is expected to increase focus on donor demands, rather than aid effectiveness among INGOs. Donor agencies should delegate less decision-making power to INGOs when resources are scarce (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2006), constraining INGO independence in goal and agenda setting, as well as their pursuit of those goals. These dynamics within the political economy of aid lead scholars to expect states to shape and authorize organization activities.

Scholars show that financial leverage works to constrain organizations. The possibility that a donor could withdraw funds is a “strong incentive for NGOs to meet donor standards,” whereas nonfinancial sanctions by other stakeholders are not (Hielscher et al. Reference Hielscher, Winkin, Crack and Pies2017, 1565). Bush (Reference Bush2015) shows that increasing donor demands can prevent INGOs from engaging in particular activities. Witesman and Heiss (Reference Witesman and Heiss2017) find that donor preferences and rules that pressure organizations to take on donor priorities produce gaps in response. Meanwhile, studies of accountability raise questions about how organizational goals come into conflict with responsibilities to stakeholders and the priorities of donors (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2008; Hilhorst et al. Reference Hilhorst, Melis, Mena and van Voorst2021; Schmitz, Raggo, and Bruno-van Vijfeijken Reference Schmitz, Raggo and Vijfeijken2012). Honig (Reference Honig2018) argues that a focus on accountability and measurement (Choudhury and Ahmed Reference Choudhury and Ahmed2002; Edwards and Hulme Reference Edwards and Hulme1996; Jordan and Tuijl Reference Jordan and van Tuijl2006) can undermine aid effectiveness by directing an INGO’s focus to what can be counted and externally verified, rather than to producing the most desired outcomes.

However, although organizations are not able to entirely “disregard market forces” without risking survival (Heiss and Kelley Reference Heiss and Kelley2017, 732), research also suggests they can “pursue their principled objectives within the economic constraints and political opportunity structures imposed by external conditions” (Mitchell and Schmitz Reference Mitchell and Schmitz2014, 489). In some cases, organizational goals remain relatively consistent, even where resource availability declines because of INGO internal balancing of programming and fundraising demands (ibid.). The effects of the political economy of aid can be mitigated by organizations that alter their strategies based on resource configurations (Heiss Reference Heiss2019). INGOs can also shape and reshape domestic and global opportunity structures at various points in policy-making processes—from strategic agenda setting to operations and contract enforcement (Dellmuth and Bloodgood Reference Dellmuth and Bloodgood2019).

Organizations that occupy a niche or are specialized, are difficult to replace or are leaders in their fields, are reliable and have strong implementation capacity, and develop diversified funding or geographic reach should be more competitive and less likely to follow donor demands (Bob Reference Bob2005; Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007; Reference Carpenter2014; Carroll and Stater Reference Carroll and Stater2009; Oster Reference Oster1992; Pugh and Hickson Reference Pugh and Hickson1989; Salancik and Pfeffer Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978). Some can buffer against external pressures and take advantage of gaps in oversight, even reshaping that external environment (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore1999; Weaver Reference Weaver2008) or “persuad[ing] donors to change their funding priorities” (Rubenstein Reference Rubenstein, Barnett and Weiss2008, 38). Relatively recent studies also suggest that INGOs that work in a popular issue area (Bush and Hadden Reference Bush and Hadden2019), have strong principles of independence (Barnett Reference Barnett2011; Steffek and Hahn Reference Steffek and Hahn2010; Stoddard Reference Stoddard2006), or are based in a nation where funding is not too restricted by government are likely to enjoy more freedom to act independently (Stroup Reference Stroup2012; Stroup and Murdie Reference Stroup and Murdie2012). These literatures tell us that both conditions of an INGO’s environment and its responses to it determine its ability to resist market forces.

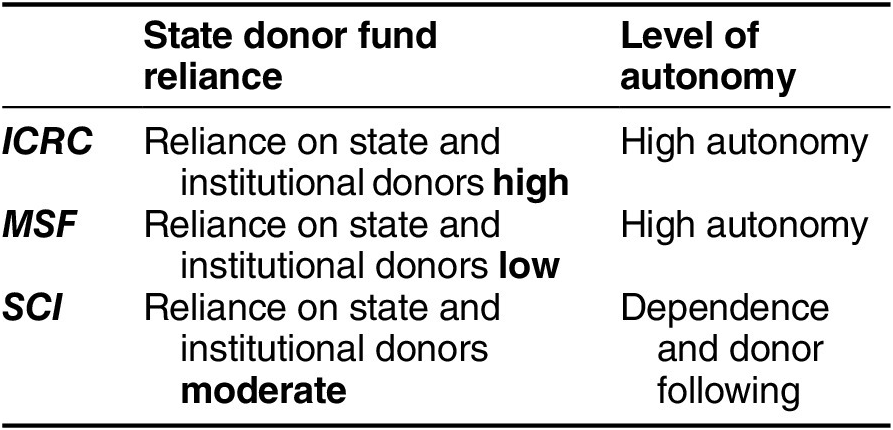

Yet, the existing literature is missing answers to two questions. First, why are some INGOs more able to secure autonomy than others? Second, what skills and strategies help an organization pursue its own objectives in the face of funding constraints? As funding contracted in the Middle East, both organizations that were highly reliant on donor funds to continue their activities and those that were least reliant could report autonomy. Table 1 provides an overview of state donor fund reliance and autonomy levels across three INGO case studies. It shows that, during the response to the Syrian refugee crisis, donor control did not correspond with reliance on state donors for funds.

Table 1 Donor Reliance and Levels of Autonomy

This article contributes to the literature by exploring how “independent agent strategies can influence a principal’s decision to delegate and the agent’s level of autonomy” (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2006, 200; Nielson and Tierney Reference Nielson and Tierney2003) It focuses on the decisions of aid workers, their day-to-day relations with donors, and their beliefs in their relative autonomy or dependence to understand what factors within organizations might drive organizational autonomy.

The next section outlines the ways in which my research was designed to study factors identified in extant literatures, as well as those factors potentially missing from our understandings of organizational autonomy as an outcome.

Research Design

I explore relationships between the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and Save the Children International (SCI) and top funders of the Syrian Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan (Syria 3RP): the European Union (EU), the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department (ECHO), the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID; now FCDO), and the United States (USAID). I collected data using a multimethod approach considered among the most reliable in studying autonomy by scholars of organization and management. Large-N studies using an autonomy scale often obscure determinants of autonomous outcomes, whereas interview methods, in particular, support identification of these factors (Arregle et al. Reference Arregle, Dattée, Hitt and Bergh2023). Self-reports from principals or agents, as standalone measures, can produce problems such as key informant bias (Kumar, Stern, and Anderson Reference Kumar, Stern and Anderson1993; Podsakoff and Organ Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986) or lead to reporting of “failures” as outside respondents’ control and successes as within them (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman2000). When reports from both principals and agents are combined with other measures, researchers gain crucial insights into how interviewees understand their own behavior and interactions with their environment.

I interviewed and observed aid workers working across levels, including INGO leaders in the field and at headquarters, as well as aid workers implementing activities. Interviews were semi-structured and lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours; lengthier interviews facilitated trust-building and deeper engagement, which helped tease out and address potential over- and underreporting of autonomy. These interviews were conducted in Lebanon, Jordan, and in headquarters in London, Geneva, and Paris (on approach, see Fujii Reference Fujii2018; Soss Reference Soss, Yaniv and Schwartz-Shea2015). Questions concerned operational decision making and how responses unfolded—from strategy and agenda setting to implementation. To avoid overreporting of donor relations as key to decision making, I did not prompt interlocutors to think about funding (see online appendix E for details). Snowball sampling supported the expansion of my selection (Cohen, March, and Olsen Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972; Tansey Reference Tansey2007). All interlocutors gave informed verbal consent and were offered opportunities to withdraw as security and reputational risks changed. Confidentiality reduces risks to staff who remain in field operations and avoids inadvertently overemphasizing the views of organizational leaders who could be identified more safely.

I also draw on interviews with key informants at the European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (ECHO) and the Department for International Development (DFID) to identify donor interests and perceptions of INGO autonomy and donor control and their drivers. Data derived from interviews with CARE, the International Medical Corps (IMC), and Handicap International (HI) staff facilitated assessment of how far findings might travel (Gerring Reference Gerring2006; Soifer Reference Soifer2021). Historical analysis of INGO–donor relationships supports understanding of how bargaining processes unfolded over time.Footnote 10 I traveled and lived with INGO aid workers and observed country-level and field-site annual planning and day-to-day meetings, as well as aid worker activities among refugees (see Schatz Reference Schatz2013 on political ethnography). I spent time at donor agency country offices and online, conducting interviews with donor agency staff responsible for funding decisions at both ECHO and DFID. Together, these methods support identification of processes and mechanisms affecting organizational autonomy.

Operational autonomy was identified when aid workers reported or were observed making independent decisions about the implementation of projects, including setting or adjusting activities (in shelter, food aid, health, protection, etc.) and shifting to different issue areas (for example, from shelter to water and sanitation), locations (of project sites), recipients (based on inclusion criteria), or scale (altering geographic reach or recipient numbers). Strategic autonomy was identified when aid workers reported or were observed setting and upholding their own goals and agendas, often through planning processes and observed or reported in higher-level meetings, or where field-based input on organizational direction was sought out and acted on. This kind of autonomy was also identifiable when an INGO spoke out about donor priorities being out of alignment with their own.

Case Selection

My analysis is focused on responses to the Syrian refugee crises in neighboring states of Lebanon and Jordan. The war in Syria was of moral and political interest to states, producing unprecedented need, funding, and organizational growth. A donor agency representative described, “There are major crises in the world. But nowadays, especially from Europe, this is war just around the corner.”Footnote 11 When funding from top donors to the Syria 3RP as a proportion of the appeal began to drop in Lebanon and Jordan in 2013 and 2014, it did so in an environment in which organizations had opened or dramatically expanded operations within the last two years (Clarke and Güran Reference Clarke and Güran2016; Ruiz de Elvira Reference Ruiz de Elvira2019; Sweis Reference Sweis2019). In 2011, “there were not many organizations ready for the flow of money into the country”Footnote 12 so INGOs had to expand rapidly. Subsequent contraction in the funding environment put significant pressure on INGOs that had grown and were working in a high-need protracted crisis.

Donor representatives also described a shift in “mood to [an] after-emergency mode”Footnote 13 ECHO interests in the MENA region in 2016 focused on an emergency humanitarian response: (1) seeking partner or “participatory” input into priorities before developing a Humanitarian Implementation Plan (HIP) for that year; (2) insisting that partner proposals aligned with set HIP priorities; (3) pulling back from funding projects geared toward “resilience” requiring donors with a “longer-term view” and looking for “projects that are lifesaving”; and (4) aiming to reduce partnerships because of limited financial resources and oversight capacities: “You shouldn’t have 40 partners if you don’t have the capacity to monitor and follow-up with them. You just throw money out of the window.”Footnote 14 The European Commission HIP clarified the boundaries of humanitarian action as providing humanitarian and food assistance, relief, and protection to persons in crisis and to existing crises “where the scale and complexity of the humanitarian crisis is such that it seems likely to continue.” (European Commission 2015, 7)

Yet, as crises in the region were being reclassified as protracted, funders were broadly shifting to a more long-term view in the region. A European Parliamentary brief in 2017 captures a shift toward multiyear, resilience activity:

In February 2016, at an international donor conference in London, the international community agreed on “a comprehensive new approach.” … Central to the new approach agreed during the conference is a shift of emphasis from traditional humanitarian aid to “resilience building.” This implies creating the long-term conditions that will allow Syrians to build a future for themselves and their children in the region, including acquiring the skills and tools to rebuild their own country once they are able to return. (Immenkamp Reference Immenkamp2017, 2)

DFID aimed to fund longer-term, resilience-focused activities. A representative said, “The way we fund projects is going beyond humanitarian support.”Footnote 15 They described looking for partners who could move between responding to a battle and resilience building:

Linking relief and rehabilitation and development, now resilience—It is the same thing under a different banner. Now looking at the protection concerns, how do we move from just these curative or treatment of symptom measures towards getting to the root causes of things?… The average is 17 years for somebody to be displaced. We are going to be here for at least 5 years.Footnote 16

DFID’s aims in the MENA region included: (1) asking partners to feed into priority setting and participate in coordination and joint assessment platforms; and (2) building confidence through evidence-based programming, monitoring progress against agreed indicators and efficient, responsive communication between INGO and donor. One representative said, “Pick up the phone.”Footnote 17 They also aimed to build complementarity across issue areas (Barbalet Reference Barbalet2019) and, like ECHO, channel funds through fewer partners, with the best “ones that can maneuver through changing contexts.”Footnote 18 DFID key informants described what they looked for in INGO partners: “The partners that are most flexible are proactive and say, ‘we can’t do this or meet these targets, but we can do…’ That’s good program management.”Footnote 19 They described partnerships that left behind the old donor–recipient model.

The ICRC, SCI, and MSF are comparable in terms of their large budgets, long histories, and operational capacities. Their differences in other features allowed me to consider various potential sources of autonomy among large INGOs. They are representative in the “minimal sense of [potentially] representing the full variation of the population” of large INGOs (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008, 297).

Founded in 1863, the ICRC aims to uphold international humanitarian law (IHL) and is mandated to do so. Its assistance activities, however, are also comprehensive and include livelihoods, protection, and health (see online appendix D). It is moderately specialized and highly dependent on state donors for funding. By contrast, MSF was founded in 1971 and is highly specialized in healthcare delivery, relying on little state donor funding for its activities while instead drawing heavily on private donors. Founded in 1919, SCI focuses on the rights of children and offers comprehensive services, including protection, nutrition, health, and shelter. It relies on state donors for more than half its global programming.

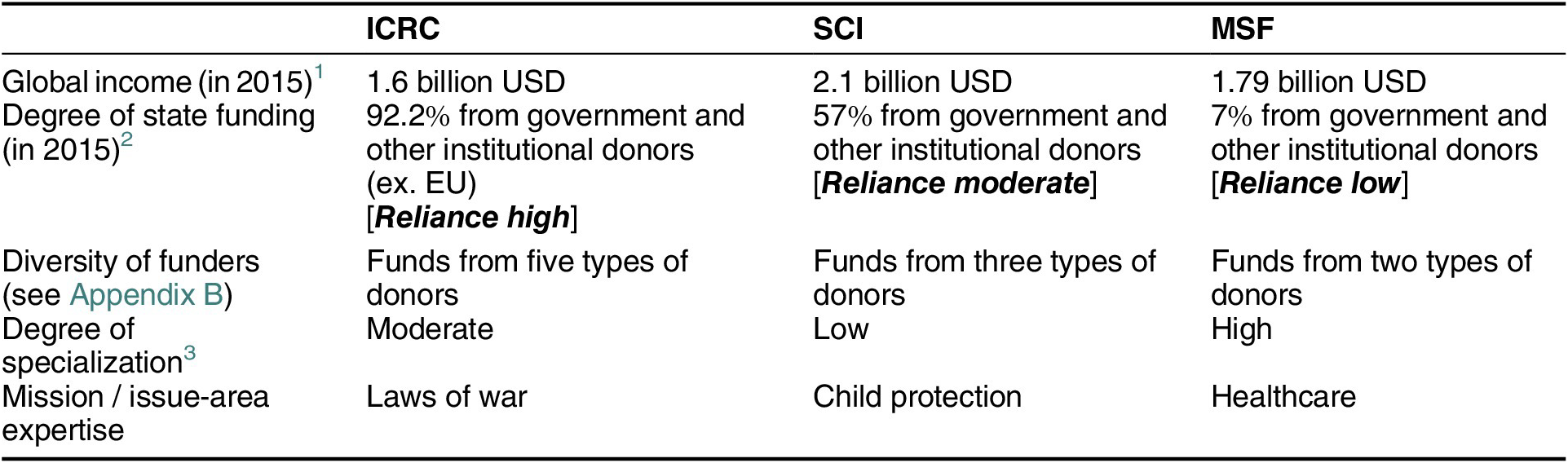

Existing literatures suggest that factors that influence INGO relationships with donors include budget, degree of state funding, diversity of funders, degrees of specialization and missions/issue-area expertise. Similarities and differences across factors expected to influence INGO autonomy are captured across the three organizations studied in table 2.

Table 2 Case Selection: Similarities and Differences

3 Specialization refers to the extent to which an organisation focuses on one issue area: ICRC is specialized in the laws of war, as well as health, but it also works comprehensively (assessed as moderately specialized); SCI has potential specialization in child protection and rights but works comprehensively with a partial focus on this area (low), and MSF is specialized in healthcare, offering some comprehensive services, such as shelter or water and sanitation during emergencies or when related to healthcare (high).

Between-case comparison supports analysis of dynamics affecting autonomy (see online appendix D), including key dynamics expected to affect autonomy in existing theory and through theory building. First, the cases capture high, moderate, and low reliance on state funds while funding availability and budget are relatively comparable. If organizations that are reliant on state funds to continue their activities are autonomous while less reliant organizations are dependent, this suggests that something other than funding levels and diversification affects organizational autonomy. Second, differences in degrees of specialization and mission/issue-area expertise allow me to investigate the relative influence of these factors on organizational autonomy. Notably, all three organizations studied had long-established issue areas of focus—the law for the ICRC, healthcare for MSF, and child protection for SCI. However, there was variation in donor-reported views of organizational reputations in these areas, as well as aid-worker–reported views of their organization’s reputations, and the opportunities and challenges these created.Footnote 20 Examining these factors historically—within cases with histories long enough to allow for them to change—facilitates analysis of the ways organizational dynamics affect autonomy over time and can be shaped and reshaped.

Finally, to identify what else was influencing INGO autonomy, theory building captures factors missing from existing literatures. I propose a theory of negotiation experience in the next section. Difficult-to-disentangle relationships among internal management structure, reputation, resistance, and autonomy—as well as how these relationships are negotiated—are examined and analyzed through the case studies.

Negotiating Autonomy

Research highlights the importance of negotiation experience—strategies, skills, and a culture of resistance—to INGO autonomy. This section provides an overview of these findings and of how empirical study and theorizing of negotiation experience can contribute to scholarly understanding of organizational autonomy.

INGOs can develop and strategically leverage skills and strategies (such as principled-wall or refusal tactics, introduced later), as well as specialization or issue-area expertise (for instance, in healthcare) to improve their position within the political economy of aid over time. Findings highlight that (1) INGOs and donors are mutually dependent, (2) negotiation experience is key to understanding strategic improvements to INGO autonomy within or outside relationships with state donors, and (3) although INGOs take different pathways to autonomy, specific negotiation tactics are identifiable across cases. Lastly, (4) negotiation experience—often gained in operational and security practice in the case of humanitarian INGOs—can be a crucial model and source of learning across institutional silos and for donor relations.

First, relationships between INGOs and donors are reciprocal, which makes negotiation between them both possible and necessary: “While donors offer resources, NGOs offer expertise, local knowledge, specialized capabilities, and legitimacy” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014, 82) This means that even though INGOs require funds, donors also need, for example, the moral authority and distributive capacities of INGOs if they wish to use service delivery to soften the blow of foreign policy decisions or prevent conflict spillover. Stated differently, INGOs and donors are mutually dependent with overlapping interests that cannot be realized independently, which are crucial conditions for bargaining and negotiation (Jönsson Reference Jönsson, Carlsnaes, Och and Simmons2002; Schelling Reference Schelling1980). INGOs that recognize this mutual dependence and develop the will and capacity to negotiate—or a culture of resistance—are more likely to secure autonomy within these relationships.

Second, negotiation experience shapes INGO–donor relationships and alters degrees of INGO autonomy by giving the INGO the tools to reduce constraints on its independent behavior, such as conditionality in contracts with donors or limited diversity in funding. Negotiation experience supports INGOs in moderating the effects of those factors previously identified in literatures on organizational behavior and resource dependence. Although the availability of funding matters, INGO levels of negotiation experience also determine the extent to which they will highlight their own offerings—from issue-area expertise in strategy and agenda setting to implementation capacity. This does not suggest that negotiation experience is deterministic—an INGO with developed strategies, skills, and a will to resist will not necessarily gain autonomy. In fact, an experienced negotiator might choose to follow donor demands on one contract because the INGO prioritizes resistance to the terms of another contract. Larger INGOs, like the ones studied here, often require large contracts to maintain themselves and so may make a trade-off in one area to gain in another (Balboa Reference Balboa2018; Stroup and Wong Reference Stroup and Wong2017). Overall, however, an INGO without experience negotiating is unlikely to gain autonomy, because even under conditions of high funding availability and diversification, a donor is likely to set conditions if an INGO does not resist.

As theorized in figure 1, negotiation experience shapes an INGO’s position in the political economy of aid and the extent to which funders can influence its activities. Negotiation experience tells an important—and previously missing—part of the story: An INGO can only turn funding availability into autonomy when it asks for what it wants in negotiations with donors and does so based on strategies and skills that will elicit donor concessions. A culture of resistance to external demands is crucial in understanding why some INGOs make their own demands—ask for what they want.

Figure 1 Understanding Autonomy: Two Key Factors

In the absence of negotiation experience, an INGO may take some independent action, but doing so requires that it take advantage of ambiguities or slack in contract or organizational design (Cohen, March, and Olsen Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972). The latter occurs when the INGO takes advantage of areas not monitored by a donor or of consequence to it, opportunities to disobey, or gray areas in the donor relationship (Weaver Reference Weaver2008) after agreeing to constraints. However, on balance, the INGO is unlikely to increase the scope for autonomous behavior through these means. Although there will be some self-directed activity in the spaces the donor does not oversee or control, the INGO is unlikely to strategically alter contract conditions, funding diversification, or its position within the political economy of aid over time—except perhaps where marginal changes to conditions are made because disobedience slowly shifts donor and INGO expectations.

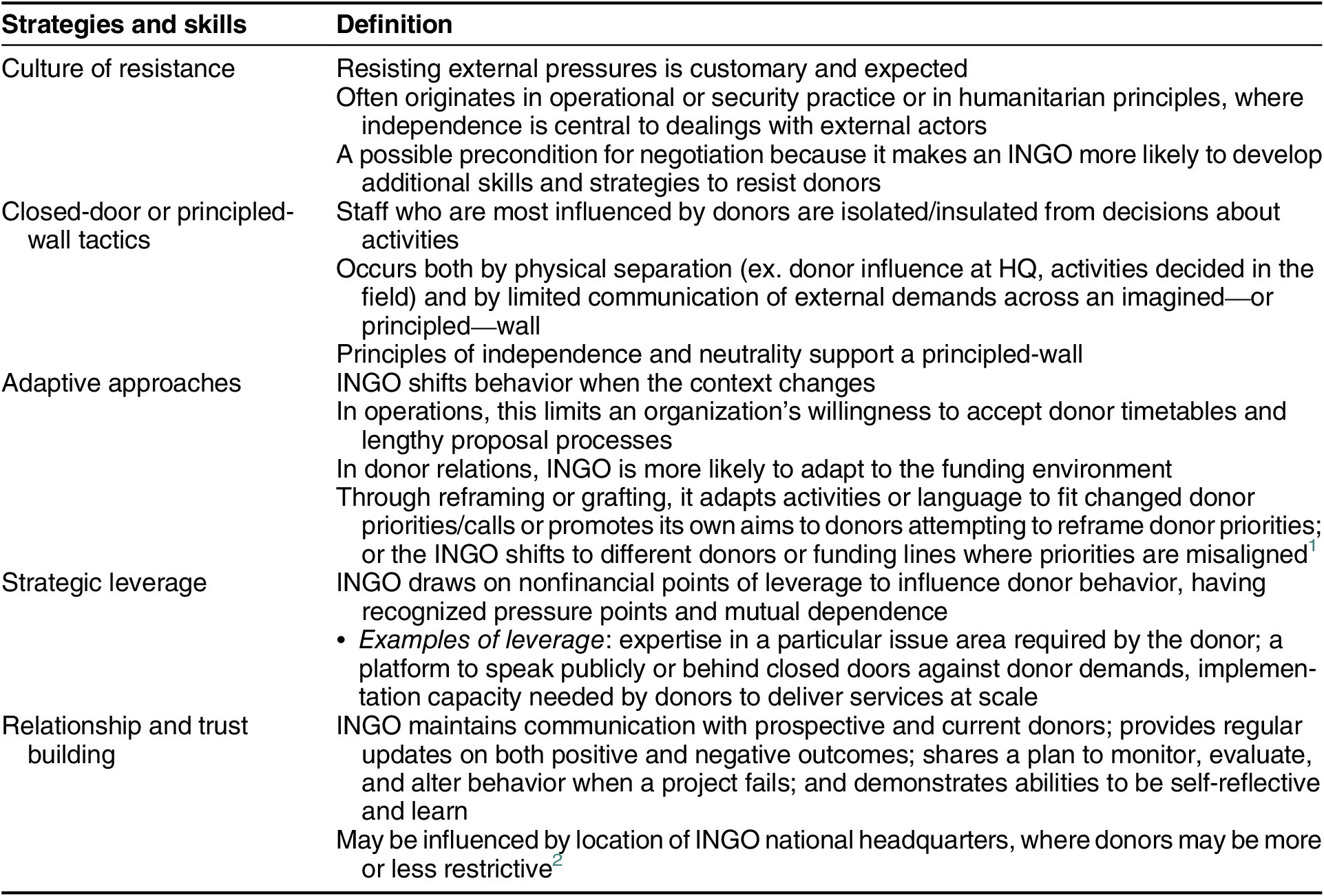

Third, studies that use negotiation as an explanatory variable tend to focus on skill levels, bargaining strategies (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2013; Snyder and Diesing Reference Snyder and Diesing2015), bargaining success (Zartman and Berman Reference Zartman and Berman1982), or experience (Hopmann Reference Hopmann1996). My research identifies specific INGO negotiation tactics, as outlined in table 3.Footnote 21 These strategies and skills can be learned, practiced, changed, and even lost over time.

Table 3 Tactics of Experienced Negotiators

1 Notably, when INGOs pursue various funders there are risks that it will alter priorities or missions, which can itself be destabilizing (AbouAssi Reference AbouAssi2013).

2 See Stroup Reference Stroup2012. Research does not suggest that the INGO’s national environment explains identified variation. See online appendix C.

Fourth, for humanitarian INGOs, negotiating in operations or security practice can have strong effect on negotiations with donors. Institutional knowledge about how best to approach bargaining with powerful actors can permeate institutional silos—from operations and security to donor relations departments. Scholars of negotiation have studied institutional learning through knowledge transfer but note that it is rarely costless or immediate (Argote Reference Argote1999; Huber Reference Huber1991; Szulanski Reference Szulanski2000). The findings presented later illustrate this. Both the ICRC and MSF developed their negotiation skills and strategies, as well as the expertise, reputations, and structures they needed to resist donors, over decades. Studies of the ways that organizations transfer knowledge and learn about negotiation, and related skills and strategies, show that challenges to knowledge transfer are diminished where value is placed on the capacity to negotiate or it is central to an organization’s functions (Kostova Reference Kostova1999). Scholars have shown that knowledge moves through ongoing, informal, and ad hoc discussion and demonstration (Pisano 1996; Szulanski Reference Szulanski2000).

Findings

Findings are presented in two sections: (1) an account and ranking of negotiation experience at the ICRC, MSF, and SCI; and (2) an analysis and comparison of the influence of negotiation experience—skills, strategies, and a culture of resistance—on organizational autonomy in relation to other factors. Table 2 outlines variation across expected factors. Recall that ICRC state donor reliance was high (with 92.2% of funds coming from government and other institutional donors globally), SCI’s moderate (at 57%), and MSF’s low (at 7%). Based on resource dependence alone and as discussed earlier, we might expect the ICRC to be most dependent because of its high reliance and MSF to be least so because of low reliance. Yet, although they sit at either end of the resource reliance spectrum, both the ICRC and MSF report feelings of autonomy; in fact, SCI reports higher-than-expected dependence, which is echoed by its donors and was observable during field observation.

Negotiation Experience Across Three Cases

Table 4 outlines negotiation experience levels and skills and strategies found across INGO cases, as well as examples of autonomy and dependence observed.

Table 4 Negotiation Skills and Strategies Across INGOs

The ICRC has a mandate to negotiate with a range of actors and commits to principles of independence, which helped it build a roster of staff with strong negotiation skills, as well as shared institutional knowledge surrounding best-practice negotiation strategies. There is also a cultural expectation within the organization that it will resist state control. Interlocutors describe ICRC aid workers, or delegates, as humanitarian “diplomats” who are trained to resist external influence and, as described by official organizational releases, “fight for impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian action and against misuse of humanitarian activities” (ICRC, n.d.). Staff report that “the position of Head of Delegation is a diplomatic one, internal level of ambassador,”Footnote 22 who handles negotiations with warring parties behind closed doors. Abilities to strategically “influenc[e] the parties to armed conflicts and others” (Harroff-Tavel Reference Harroff-Tavel2005) were traits that aid workers reported as most valued.Footnote 23 Humanitarian diplomacy was of such importance that it was the subject of the ICRC’s primary advocacy efforts at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in 2016 (Maurer Reference Maurer2015, 449)Footnote 24:

The ICRC’s diplomacy of access is based on a continued process of negotiation to set its presence in these areas, maintain proximity to the affected people and communities, and seek the consent of the relevant parties to allow humanitarian operations to take place. This is, as everybody knows, a risky and often very frustrating, long process: we negotiated for months a crossline operation in Aleppo, a license to operate in Sudan, minimal security guarantees for our field operations in Afghanistan, and many more examples.

Resisting external influence is also embedded in humanitarian principles of neutrality and independence adopted by the ICRC, which call for aid to be delivered without taking sides in hostilities. Staff must “always maintain their autonomy so that they may be able at all times” to deliver assistance based on need alone (ICRC 2016b, 5).

These organizational expectations were felt by aid workers in the field and altered their behavior. They reported being expected to adeptly navigate sensitive and tense situations with a range of actors, including conflict actors; acting as the “watchdog of international military law”Footnote 25; and negotiating for legal protections, better prisoner treatment, and their own personal security.Footnote 26 Some also said that organizational expectations surrounding negotiation were so sweeping as to be unreasonably high, placing them in dangerous situations.Footnote 27 One ICRC delegate met me at a busy train station in London. This was a follow up on a first interview at a field site in the MENA region. He told me of the pressure he felt to speak to and gain concessions from powerful and sometimes dangerous actors while in the field. While talking to me, he looked around the train station as if, even at a busy station in the United Kingdom, the ICRC might be listening and condemn his call for more limits on these expectations.

At MSF, negotiating access to populations in need of medical care is central to its mission and the skills it fosters among its staff. Like at the ICRC, negotiation experience emerges in the training of its staff, and related skills are sought out and fostered among its aid workers. In the MSF publication, Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed, writers reflect on the development and use of negotiation skills and strategies to secure access to hard-to-reach areas in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, and Yemen. They outline adaptive approaches to negotiation, which are required because assessment of changing situations must be based on ongoing judgment and engagement with local actors (Magone, Neuman, and Weissman Reference Magone, Neuman and Weissman2012, 5). In interviews in 2016, the then-director of the Humanitarian Analysis Unit said in Beirut, “We always negotiate with evil people. That’s not unique for MSF.”Footnote 28 In Paris, the president of MSF France said this of negotiations with the Islamic State: “It’s true that we were capable of cohabitating with radical groups two years at least in Syria up to the kidnapping. Negotiating with them.”Footnote 29

Second, MSF resists external influence based on an “ethics of refusal” (Rubenstein Reference Rubenstein2015, 163) and the idea that “moral outrage demands response” (Redfield Reference Redfield, Fassin and Pandolfi2010, 174). An aid worker explained, “If the state refused to give a work permit, MSF didn’t care, ‘oh, never mind, we go.’”Footnote 30 I observed a staff meeting in Jordan at one MSF section office, in which staff were debating how best to respond to the Jordanian government’s limits on access to the berm—a human-made sand barrier in the desert between Jordan and Syria that cut off Syrians seeking refuge there from international humanitarian assistance. One senior aid worker nearly shouted his displeasure at being unable to gain access to the area because of Jordanian military control, framing this as antithetical to MSF’s ability to negotiate with more violent actors, including the Taliban.

MSF is willing to resist and even contravene state laws or policies or to compromise their principles and stay silent where atrocities are witnessed if, on balance, it believes that these choices will help it preserve care. Despite being known today for outspoken resistance, MSF favors access and maintaining negotiations over public denouncements of warring groups. It speaks out strategically and according to context. In fact, MSF “has often opted to sacrifice its freedom of speech” (Magone, Neuman, and Weissman Reference Magone, Neuman and Weissman2012, 6) because “if doctors keep quiet, they’ll be allowed in” (178). For example, MSF stayed silent during bombings in Yemen and war in Sri Lanka in the 2000s. It also leverages its specialization in health strategically to gain acceptance from state and nonstate actors that want to placate or provide for their populations. Offers of medical care help it gain access, even where states might otherwise resist. Health activities are a “vector” for entry into places like Syria and a means to have unwilling states accept protection activities.Footnote 31 The ICRC behaves similarly.

By contrast, SCI adopts growth and partnership approaches (Mulley Reference Mulley2009; SCI 2011) and favors operating where economies of scale reduce risks and costs. An interlocutor emphasized the INGO’s growth mindset when stating, “Going back to the donor, it’s all about numbers, and how many, how many, how many. So, for us, it’s cost efficiency. If you’re going to spread out too thin in areas where you have a small number of refugees, operation is costly.”Footnote 32 Despite its long history of activity—it was founded in 1919—SCI engages less frequently than the ICRC or MSF in direct negotiation with dangerous actors or in hard-to-reach places, relying more on local actors to make these connections. Its staff does negotiate with officials in municipalities, managers of buildings that house refugees, or shop owners operating World Food Programme food distribution. One aid worker described, “We discuss and negotiate. We do talk a lot with the landowners. This is their land. Let’s say they don’t allow you to do things, you discuss why they don’t allow you. How can we limit the impact?”Footnote 33 Aid workers also highlighted the need to communicate about SCI’s priorities with municipalities and ministry leaders.

But resistance to external pressure is not a regular SCI practice or organizational norm.Footnote 34 My field notes record interactions between SCI staff and various refugee and local leaders as instances of gathering or communicating information, as well as crucial relationship building to facilitate donor-directed implementation; for example, of food aid programming commissioned by the World Food Programme. Although there is evidence that this communicative, partnership approach improves relationships with local leaders and facilitates getting project “green lights” from local governments, I saw no evidence of resistance. Day-to-day operational efforts were aimed at securing project permissions and access for donor-funded projects, which drew on and reinforced skills for donor following.

In negotiations with donors, an experienced negotiator would be expected to leverage its nonfinancial resources and comparative advantage, such as its issue-area specialization in child protection. However, an SCI aid worker explained, “NGOs like World Vision and Save the Children are the Walmart of NGOs whereas you have MSF who are more specialized. They do that thing and they do it really well. But you have agencies like Save the Children where you have a menu of options and you can choose whatever.”Footnote 35

Highlighting the ways in which SCI could do things differently, a former country director in Beirut told me, “SC keeps losing itself.”Footnote 36 He explained that although the organization could specialize in child rights or protection, it had not developed a strategy to excel in this area or learned to exploit it to gain autonomy from donors. SCI was unable to retain staff in this sector in Lebanon and had trouble securing crucial visas for international staff to fill in gaps. While sitting on a hillside in the Bekaa Valley with a technical expert working for SCI in 2016, the staff member described the reputational costs observed as a result: Donors had told SCI staff that they were falling short in child protection. The technical expert predicted that funding would be lost because SCI was not sufficiently specialized and was spreading itself too thin to be a desirable high-capacity partner to funders. I also noted vacancies in this sector and in others for SCI across field sites. One aid worker said of the impact of this issue, “For Save the Children there is also a need to invest in the technical people and be really relevant in what you propose. The donor is not stupid. You need the capacity.”Footnote 37 I saw the impact of this missing capacity when I was visiting an informal tented settlement. There, a child’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms were triggered when a plane flew overhead—the child rocked back and forth, covering their ears and crying. I noted no response from SCI staff, who were supposed to be trained in child protection first aid. When I raised this later with operational leadership, they told me they had recurring problems with staff not fully trained and referrals of child protection issues not being made.

Of these three INGOs, the level of negotiation experience at the ICRC is high with the longest history (going back to its founding in 1863); at MSF it is high but more recently earned (developing in the 1980s, as I discuss later); and at SCI, it is relatively low despite its long history (having been founded in 1919). The next section discusses what negotiation experience and its development over time can tell us about INGO autonomy.

INGO Autonomy in Three Cases

International Committee of the Red Cross

As funding contracted in Lebanon and Jordan, the ICRC was able to maintain organizational autonomy. Its assistance budget—mostly given by state donors—for the Middle East even rose from more than 252 million Swiss Francs in 2014 to over 349 million Swiss Francs in 2016.Footnote 38 Negotiation experience helped the INGO secure autonomy while accepting this high level of state funding. Specifically, expectations that staff resist external demands and the use of closed-door (or fire/principled-wall) tactics in operations and security practice were replicated in donor relations and were facilitated by new internal structures built by the ICRC.

Closed door (or fire/principled-wall) tactics make only a few delegates party to negotiations surrounding the Laws of War and a particular conflict, while others are kept out. This helps the ICRC cultivate trust in relationships with various actors. As an implication, the ICRC may call on parties to a conflict to facilitate its access and protect its operations under the Geneva Conventions but will (almost) never make public statements denouncing actors who fail to do so. One MSF doctor described this as “forced mutism” (Moorehead Reference Moorehead1999, 625). The ICRC prioritizes sovereign state permissions over public-facing resistance and has even accepted working with repressive regimes like the Assad regime to maintain activities and closed-door negotiations. This is a common tactic for humanitarian organizations that prioritize neutral and impartial provision of assistance on all sides of a conflict (Beals and Hopkins Reference Beals and Hopkins2016; New Humanitarian 2012).

Over the last two decades, the ICRC has institutionalized similar strategies in its donor relations departments, which are particularly evident in changes made to its internal structures and aid worker reports. After the Seville Agreement on cooperation was signed by members in 1997, the ICRC centralized points of donor influence at headquarters in Geneva through a Donor Support Group (DSG) and External Resources Division (EXR). This separated donor state and INGO interactions from decision makers in the field. The DSG and EXR were tasked with bringing together state funders to discuss ICRC programming and policies (ICRC 2018). Mirroring closed-door (or fire/principled-wall tactics) strategies, this limited points of contact with representatives from government or institutional donors and, according to various interviewees, produced autonomous space for country-based staff to make operational decisions with less influence from donors. Said one aid worker about the ICRC’s isolation from donors brought about by the EXR, “Some NGOs are miserable… other NGOs, you are in the budgeting with donors.”Footnote 39 Additionally, the ICRC’s results-based management process (or the Planning for Results [PfR] process) was set up so that programming and projects were developed and planned in the field and country offices before being sent to headquarters for approval. This meant that staff who may have been influenced by donors at headquarters in Geneva were more removed from the first stages of strategic and project planning and design, indicating strategic autonomy. Mimicking the closed-door approach that maintained its operational and security practice, the ICRC made it more difficult for funders to make demands of staff who made operational decisions.

Field and country-level staff in Lebanon and Jordan reported that they gained autonomous control over activity proposal and design, with less interference from donors, because of these changes.Footnote 40 “Things are less and less black and white. More and more conditions regionally. But we don’t accept.”Footnote 41 Once proposed, in-country delegates said that headquarters and the ICRC General Assembly were unlikely to reject field-proposed activities, which suggests that donors were also not influencing the final decision-making stages. One ICRC delegate described being removed from donors, saying, “In the field we don’t see it. We don’t even do reporting for donors. We have awards in HQ.”Footnote 42 Instead, funding was mostly an un-earmarked yearly “envelope” that could be distributed as a country office saw fit.Footnote 43 For example, funding allocated for certain uses could be moved in response to changing patterns of violence or refugee movement without involving headquarters, suggesting operational autonomy.Footnote 44 Reflecting on how new internal structures put a wall between himself and donors, an ICRC leader in the Middle East went so far as to state, as quoted at the beginning of this article, “We undertake humanitarian need-based, ambitious projects with the self-confidence that donors will follow.”Footnote 45 This leader attributed his autonomy to this changed structure and his ability to set his own expectations or conditions, saying, “Donors have conditions, but we also have conditions. I am not naïve, but Geneva negotiates…. It is a privilege that we don’t need to think of money being in the field.… It gives you even more freedom and everything. Maybe the guys in Geneva, they have more pressure and need to negotiate. I mean, I don’t know even if it is the Japanese government, if it’s ECHO, I don’t know.”Footnote 46

Interlocutors may have incentives to overstate their independence in this case, particularly because the ICRC has developed principles of, and a reputation for, independence from state influence despite its mandate (ICRC 2016b; Mierop Reference Mierop2015). However, an external evaluation in 2006 also found the new Planning for Results structure focused the ICRC’s activities on the field and population needs. It stated that the PfR process “ensures a certain degree of coherence, both vertically (between ICRC delegations and headquarters) and horizontally (between administrative departments and technical sectors, as well as between different delegations) and helps focus strategic thinking and activities on target populations.”Footnote 47

ICRC Framework Partnership Agreements (FPAs) also commit donors to the INGO’s independence in partnerships; they carefully avoid contractor language that might diminish its position. For example, the European Commission’s FPA states, “The actions of the components of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement are at all times directed in accordance with the values and principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement” (European Commission 2014, 6). This autonomy extends beyond ICRC activities under its protection mandate to its assistance activities in health, livelihoods, and more. An ECHO representative explained the ICRC’s unique strength: “We have a bit of a particular FPA (legal framework) with ICRC and this doesn’t allow us to negotiate with partners. The legal framework with ICRC is not that flexible, meaning that we fund what we fund, we cannot really pick up what we want differently from other partners.”Footnote 48 Thus, the ICRC’s significant autonomy is not only felt internally but also is understood by external evaluators and funders.

In sum, ICRC closed-door or principled-wall negotiation strategies and skills, commonly used in operations and security practice, also increasingly insulated those activities from donor influences over the last two decades. The INGO was able to limit the conditions placed on its behavior while in contracts with donors. An ICRC leader in Jordan described independence while still being donor reliant, in comparison to MSF: “MSF has 90% private funds, 10% institutional. ICRC has 90% institutional and 10% private. But, operationally, it’s the same thing.”Footnote 49

Médecins Sans Frontières

Notably, a resource dependence model would likely predict that MSF would achieve autonomy from state donors because it takes very little from state donor agencies. Indeed, there is ample evidence that MSF autonomy has grown over the last two decades: It reduced its relative reliance on state funds (and restricted funds), particularly in the 2000s. Consolidated financial reports became available in 2004 and show that more than 22% of MSF funds came from state donors and almost 98% of that funding was restricted at that time (MSF 2005, 11). By 2016, however, just over 3.5% of funds were coming from these donors, and those funds were 96% restricted (MSF 2017, 9; Weissman Reference Weissman2016, 5), indicating that MSF had dramatically reduced its acceptance of conditional funds.

However, MSF has not always had such a strong position within the political economy of aid. Negotiation experience is key to understanding how MSF shifted from a reliance on government funds in the 1970s and 1980s to a position of autonomy in the 2000s. It can also help us understand MSF’s refusal of a potential 60 million euros in European Union funding in 2016 (Kingsley Reference Kingsley2016; MSF 2016b),Footnote 50 just as funding for the Syrian refugee response was in decline and needs continued to rise—which a focus on financial resources could tell us less about. Although the refusal of funds is not, alone, an indication of autonomy, in this case it was accompanied by statements by MSF condemning state behavior, showing clear differences in interests, principles, and values. MSF demonstrated high degrees of strategic autonomy in expressing and acting on those differences.

In contrast, during the 1970s and 1980s MSF accepted state funding tied to foreign policy outcomes, including the pacification of societies (Fox Reference Fox2014; Redfield Reference Redfield2013). Soviet expansion, wars in Angola, Mozambique, Somalia, and Ethiopia, and refugee flight from Indochina provided MSF a “fertile field of action” (Weissman Reference Weissman, Magone, Neuman and Weissman2012, 23). MSF France’s president reported that the INGO started to develop a culture and expectation of resistance during its intervention in Lebanon in 1976,Footnote 51 and the shift to this culture accelerated when the Ethiopian government used humanitarian aid to fund forced relocations in the 1980s. The INGO started to resist the use of its activities for political purposes (Brauman and Tanguy Reference Brauman and Tanguy1998) and to develop an identity (and later, a reputation) as an “organization that dealt with dangerous emergencies” (18). MSF first spoke out in Ethiopia in 1985 and then during the 1991 civil war, the genocide of Rwandan Tutsis in 1994, after the 1995 massacre at Srebrenica, and in North Korea in the mid-1990s (Binet Reference Binet2019; Fuller Reference Fuller2012; MSF 2015). One of MSF’s researchers, in contrast, marks the beginning of its resistance of aid tied to liberal, democratizing missions to the failed peacekeeping operations in Somalia and Rwanda in the 1990s and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq (Weissman Reference Weissman2016). What is clear, is that by 1999, MSF had adopted an ethic of “refusal of all forms of problem solving through sacrifice of the weak and vulnerable” (Orbinski, quoted in Rubenstein Reference Rubenstein2015, 154). This challenged choosing who lived or died based on the political constraints created by powerful states.

Nonetheless, donor funding made MSF activities possible in its early years and helped develop its reputation. An MSF researcher wrote in the wake of MSF’s refusal of EU funds in 2016, “It is thanks to European funding that MSF has been able to access the club of billionaires NGOs and occupy a hegemonic position in the medical humanitarian field. This hegemonic position allowed MSF to raise a growing share of its income from private donors” (Weissman Reference Weissman2016, 5). By taking negotiation experience into account, we can explain how MSF made and leveraged reputational gains, diversified its income, increased private donations beginning in the 1990s (Herzer and Nunnenkamp Reference Herzer and Nunnenkamp2013), and refused more state funds over time.

Like the ICRC, MSF developed strategies and skills in its operations and security practice that benefited its donor relations activities. The latter eventually drew on MSF’s ethics of refusal and adaptive approaches to speak out against state donor demands. An aid worker explained how MSF’s reputation in the field and as a medical expert became the basis for resistance: “We send drugs, we send consumables, and they are very happy at the frequency, the reliability, the quality of the things we send, and through this, we are building credibility.”Footnote 52 When considering why MSF was able to do what other INGOs could not, another staff member said, “I mean, ICRC and MSF are the—to me, this is subjective—are the two biggest medical NGOs providing the highest quality of care and not everyone can do this kind of project.”Footnote 53 Finally, an aid worker tied these strategies to refusing millions of aid dollars and standing up against donor agendas:

It’s a very long process but I think the reputation of MSF by now after 45 years help to get the authorization [in the field]. People know that even if we’re a big mess and sometimes big troublemaker as we do at the moment with the European Union by refusing 62 millions of donations, of fundings. On this side, people know that we are neutral, that we provide very high quality of care and we’re not here to make trouble with politics.Footnote 54

MSF now cedes very little to states and donors. By demonstrating operational autonomy, it aims to remain adaptive and able to move quickly; it is unwilling to engage in lengthy negotiations with donors that will delay activities.Footnote 55 Others said that maintaining MSF’s reputation in health and for principled independence from state influence was a key strategy for securing private donor funding and that private donors were not likely to try and direct the INGO’s behavior.Footnote 56

Highlighting why MSF avoids donor dependence, an aid worker said, “Once you are restricted by donors, then you’re thinking about everything differently. Right? Like you might want to be a little more strategic about where you go, or you might have a little more leeway, but you’re still always bound by certain constraints.”Footnote 57 Another MSFer explained the current reality: “We can take decisions that we wouldn’t be able to take if we were tied up in a circle with USAID … with the power donors wield.”Footnote 58

MSF has strongly established itself as an autonomous actor today. A DFID representative recalled that, in the MENA region, “MSF didn’t want to take [funds], they were specific about the money they wanted to take.”Footnote 59 An ECHO representative cited MSF’s decision not to take EU funding; he said his organization had offered money, but MSF responded with an outright “no.” He chuckled at the strength MSF had to refuse donor funds, in contrast to his own donor agency’s weaker position in negotiations.Footnote 60

MSF’s adaptive and refusal approaches to negotiation led it to openly decline donor funds and snip its political strings; it did so by strategically leveraging its nonfinancial resources, including issue-area expertise and a reputation for resisting external demands. Negotiation experience helps us understand how this occurred and how dependence in its early decades turned into autonomy later.

Save the Children International (SCI)

SCI is moderately reliant on state funds. The INGO received between 49% and 58% of its funds from state institutions between 2012 and 2016. In the same period, private donations decreased from 28% to 25%. Corporate contributions grew from 13% to 19% of funding over the same timeframe (SCI 2013, 15; 2014, 21; 2016, 28; 2017, 27). If resource dependence was the main driver of donor-following behavior, SCI might have been able to secure some autonomy because of its moderate reliance on resources and funding diversification. In fact, SCI had more funding from donors than it anticipated it would need (and appealed for) to maintain its activities. An ECHO representative reported, “They receive too much money and have difficulties implementing programs, of getting approvals from [host state] government. It is not an underfunded intervention.”Footnote 61 SCI interlocutors, too, reported trouble spending funds and applying for “no-cost extensions” from donors, which allow an INGO to carry over money allocated for one year to the next.Footnote 62 SCI maintained a growth mindset and accepted the direction of donors. One day when going down the stairs to the parking lot under the SCI offices in Beirut so that we could get in an aid convoy headed to a project site, an INGO leader told me that they were distracted from the operational work they had to do: It was more pressing instead to secure one of these no-cost extensions on funding that SCI was not able to spend. Donor-following behavior was constraining operations and diverting INGO leadership focus from its own goals and activities because the INGO had received more money than it could spend.

SCI negotiation strategies and skills, as well as its organizational culture, were deeply rooted in a donor-pleasing approach. A member of senior leadership explained that Save the Children International was created—bringing together national sections— with growth in mind: “At one point ‘be larger than UNICEF’ was proposed as a goal.”Footnote 63 Aid workers regularly discussed their work in funding language, such as “You will work on the ECHO project in the Bar-Elias district today,”Footnote 64 suggesting a lack of operational autonomy; they expressed beliefs that donors would withdraw funding if they failed to follow donor directives, indicating a lack of strategic autonomy. In a high-speed ride from Akkar Governorate south to Beirut, a fieldworker giving me a lift told me that SCI staff was most focused on fulfilling donor wants, because they feared they would lose their jobs in coming months. SCI staff in Lebanon and Jordan expressed this feeling far more frequently than staff interviewed and observed at MSF, the ICRC, CARE, the International Medical Corps, and Handicap International. They were also significantly more likely to claim their activities were directed or hampered by donor priorities.Footnote 65 In contrast to the ICRC, SCI also delegated significant dealings with donors to country-level and project-level staff; I commonly observed external funders visiting SCI country offices and project sites. Donor following exacerbated SCI’s dependence and vulnerability, ultimately undermining its position.

Negotiation breakdowns are significant in explaining the failure of SCI in Lebanon to secure ECHO funding in 2016, after ECHO had funded 37.8 million dollars of SCI activity the year before.Footnote 66 One month before the SCI proposal was rejected, ECHO visited its projects. At one site, the donor found poor water and sanitation practices; interlocutors described SCI-hired water tank trucks (driven by subcontractors) moving through refugee settlements with hoses dragging in wastewater and mud while water drained onto the ground. Refugees told donor representatives that SCI had not been at the site for three months and that gravel and new branded water tanks had been delivered only days earlier.Footnote 67 Staff also reported that the poor performance of SCI and negative refugee accounts were only part of the problem, however.

Of equal importance was SCI’s failure to maintain relationships with ECHO and to proactively communicate challenges and failures; as discussed earlier, proactive communication is a key donor interest and is crucial to the success of partnerships. When SCI was implementing ECHO-funded projects in 2016, it was obligated to submit updates and amendments when security, logistical, or operational issues required changes to project plans. According to its own field staff, SCI did not report that the site ECHO was visiting had been out of reach due to insecurity or that the INGO was struggling to provide water because few competent contractors were available.Footnote 68 Nor had SCI indicated to ECHO that it was struggling, more broadly, with delivering water and sanitation services alongside its comprehensive suite of activities. When negative assessments came back, SCI did not remind the funder that it had taken on the task of providing water and sanitation in the area because there was a gap in those services there and that the INGO was still building its capacity in water and sanitation service delivery.Footnote 69 In addition, SCI staff reported they did not have the strategies or skills to push back against negative donor assessments or justify decisions or failures and that national offices and headquarters did not empower the field to speak up with donors.Footnote 70 SCI lacked a culture that would lead its staff to do so. One interlocutor recalled donor representatives condemning SCI for the piles of garbage found on the side of the road in an informal settlement while a national garbage strike was making headline news, and staying quiet.Footnote 71

Surprisingly, given its growth mindset and donor-following behaviors, SCI also did not adjust its programming to better suit donor interests. This is a key tactic available to NGOs that are resource dependent (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014, 74), although it can be problematic for INGOs wishing to maintain strategic coherence (AbouAssi Reference AbouAssi2013). As the Syrian refugee crisis became protracted and refugee needs changed, an ECHO representative said that SCI submitted projects based on concepts of resilience, which ran contrary to ECHO interests and desire to continue funding emergency projects, despite the changing context. Such resilience-based proposals were more suited to longer-term development funders.Footnote 72 SCI also did not target or accept requests for partnership from other funders interested in longer-term development projects, such as UNICEF.Footnote 73 An interlocutor at SCI involved in donor relations said, while reflecting on the loss of ECHO funding, “There are some donors that we will, by definition, not be able to engage in these kinds of projects. While others, certainly might be able to embed it in their structure.” They further described not adapting to changes in the funding environment, lamenting, “We need to acknowledge the donor and funding environment is out there. It doesn’t mean we will not continue advocating for certain priorities, but the funding options might be different in certain cases.”Footnote 74

A growth mindset ultimately, and perhaps paradoxically, hurt SCI relations with donors. SCI staff reported conflicts or “diplomatic issues” with various donor agencies, including ECHO and UNICEF, and pointed to gaps in communication between headquarters, country offices, and the field. There was a lack of clarity in terms of who was speaking to UNICEF or ECHO and at what level, as well as personality-dependent approaches to donors.Footnote 75 SCI accepted more money than it could spend and did not pivot to new funders or effectively maintain and negotiate relationships with existing funders. The negative effect of this approach on SCI in Lebanon was made clear by its loss of funds and by damaged INGO–donor relationships. An aid worker reflected on the exceptional finality of SCI’s refusal by ECHO: “For ECHO, I heard that they just said ‘no.’ There was no negotiation, but normally there’s a back-and-forth.”Footnote 76

Conclusion

Scholars of aid expect donor-following behaviors from INGOs in times of resource scarcity or an INGO “scramble” for funds (Cooley and Ron Reference Cooley and Ron2002). Yet, during the response to the war in Syria and to refugee needs in neighboring states, humanitarian INGOs reported autonomy over decision making, even in cases where they relied on state funds to continue operations. I explore this apparent contradiction in relationships between INGOs and donors working among Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan between 2011 and 2017; I draw on interview, content analysis, and political ethnographic methods to understand the extent to which factors identified in existing literatures can help us understand INGO autonomy. These include budgets, the degree of state funding, the diversity of funders, degrees of specialization, and missions/issue-area expertise. A theory-building exercise found that an INGO’s position within the political economy of aid vis-à-vis donors is significantly shaped by another factor—negotiation experience.

Although external factors such as funding availability will limit an INGO’s ability to secure funding from donor agencies, negotiation experience shapes whether and how an INGO (1) maneuvers within those limits by, for instance, negotiating for fewer conditions or securing contracts from various donors or (2) places itself outside them by refusing donor funds. Humanitarian INGOs can strategically develop negotiation skills and strategies to help them leverage their specialization and issue-area expertise, often learning to do so in operational and security practice. Importantly, those with organizational cultures and practices that promote resistance to external demands seem most likely to negotiate with donors.