The dynamics of international engagement in contemporary armed conflict have noticeably shifted over the past decade, from “top-down” or direct intervention by external actors, such as military personnel, peacekeepers, peacebuilders, humanitarians, and human rights activists, toward more “bottom-up” solutions to conflict challenges. International actors—whether national, intergovernmental, or nongovernmental—increasingly acknowledge that they are “second-best” players: where they once undertook activities to manage or mitigate conflict that others, usually local parties, were often better placed to perform, they are now consciously seeking to empower such actors. Reflecting this shift, the Biden administration pledged to direct 25% of the United States’ aid directly to local partners by the end of 2025 and 50% by 2030 (USAID 2023).

This move toward bottom-up approaches is both pragmatic and principled. It is partly a response to the backlash against external military intervention in contexts such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, where international actors were accused of overoptimistic assessments of the effects of their actions (Kuperman Reference Kuperman2013; Menon Reference Menon2016; Paris Reference Paris2014; Peksen Reference Peksen2012; Stewart Reference Stewart2021; Welsh Reference Welsh, Parsons and Wilson2021). It also stems from greater recognition of the challenges and risks of top-down approaches, the difficulties of securing long-term access and security guarantees for international staff, and concerns in Western capitals about the financial and reputational costs of open-ended and direct intervention with an extensive footprint. More broadly, local communities and organizations are directly challenging an “international-first” approach in which external actors drive policy to instead advocate various forms of “localization” (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2021; Firchow Reference Firchow2018; Kochanski et al. Reference Kochanski, Scott and Welsh2025; Mac Ginty Reference Mac Ginty2021; Pincock, Betts, and Easton-Calabria Reference Pincock, Betts and Easton-Calabria2020).

Although such changes may be normatively and practically desirable, scholars and policy makers have paid insufficient attention to the potential organizational risks for external actors that seek to support local actors and processes in conflict settings. While any policy intervention, including top-down action, could have unintended consequences, supporting bottom-up processes could generate particularly acute organizational risks, given that such action is indirect and heavily mediated, and thus involves a variety of actors with a range of intentions and objectives. At the same time, external actors pursuing localization conceive of their support as a form of empowerment rather than as delegation, thereby calling into question the explanatory power of principal–agent theory—one of the dominant frameworks employed to analyze the risks of mediated action in conflict through foreign support for rebel groups.Footnote 1

This article theorizes and analyzes organizational risk in contexts of mediated action by focusing on external support for nonviolent civilian self-protection (CSP)—actions taken by civilians during armed conflict in response to “direct threats to [their] physical security” (Jose and Medie Reference Jose and Medie2015, 516).Footnote 2 A growing body of scholarship has brought to light the agency of civilian populations and how they protect themselves during war (Arjona Reference Arjona2017; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2017; Krause Reference Krause2018; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Masullo, Rhoads and Welsh2023; Masullo Reference Masullo2021, Milliff Reference Milliff2024; Schubiger Reference Schubiger2021; Shesterinina Reference Shesterinina2021). In parallel, a range of international and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) with protection mandates have transformed their understanding of protection from an activity done exclusively to and for civilians to one done by civilians, with international actors in a supporting role. The approach to external support varies, from backing CSP practices that originate from within a community to working with a community to identify and develop new practices and structures (Gorur and Carstensen Reference Gorur, Carstensen, Willmot, Mamiya, Sheeran and Weller2016). Further, different forms of support are provided to communities in diverse conflict settings. Such support includes (1) providing material resources such as equipment to develop or improve early-warning capabilities and reduce exposure to threats; (2) skills building and training in advocacy, relevant legal frameworks, and negotiation techniques for engaging armed groups and government authorities; (3) sharing information and best practices, including threat assessment frameworks; (4) establishing and/or supporting local protection structures and initiatives; and (5) accompanying vulnerable individuals and groups on high-risk excursions or creating joint community patrols.

In the context of this evolving landscape of international engagement in conflict and civilian protection, we first examine whether external actors supporting CSP encounter unintended consequences. Leveraging insights from sociology and economics, we explore three primary types of negative unintended consequences: unexpected drawbacks (a detrimental effect occurs in addition to the desired effect of bolstering CSP); perverse effects (international support weakens CSP or causes harm); and complicity (CSP strategies contravene the values of the international actor and implicate it in a form of wrongdoing). We move beyond examining the general challenges of supporting CSP, which primarily relate to resource constraints and logistical barriers, to consider the potential for this assistance to create a fundamental dilemma for international actors: they can heed the imperative to support local community efforts to improve the effectiveness and legitimacy of protection work, yet in doing so they face risks of unintended consequences that could, in some cases, associate these international actors with practices that contravene their organizational identities, values, and even protection goals. These challenges, which can impact the sustainability of external engagement, represent a critical dimension of the civilian protection landscape that warrants further examination.

We then assess whether organizational type influences the prevalence of unintended consequences and how international actors supporting CSP manage the risk of their occurrence. The general explanations in the literature of why unintended consequences arise (Baert Reference Baert1991; Merton Reference Merton1936) focus on agent-centric factors. They point to insufficient knowledge of the context, an excessive focus on immediate interests that can result in neglecting the longer-term or side effects of an action, and the impact of an actor’s values and purposes on its capacity to foresee the potential negative consequences of its actions. Given the differences in mandates, structures, and “epistemic capacities” across organizations, we expect that the type of international actor seeking to enhance civilian protective agency could affect the prevalence of unintended consequences and how the risks of such consequences are managed.

We empirically address these issues by examining four international organizations (IOs) that have an explicit protection mandate and support CSP strategies through their programming: the United Nations (UN), Oxfam, the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC), and Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP). To assess whether the risk of unintended consequences is present across multiple IOs and to explore whether (and how) organizational type matters, we selected these organizations to exhibit variation in potentially consequential organizational dimensions. We collected and analyzed a wealth of primary public and internal documents for each organization, conducted 36 semistructured interviews with protection staff operating in various conflict settings, and organized a workshop with representatives of these organizations to further specify the consequences of their protection programming and to understand their successes, challenges, and lessons learned.

Our analysis shows that external support for CSP is indeed a risky business. Across a range of conflict settings, all four organizations encountered three main kinds of unintended consequences: increased vulnerability and insecurity for local communities, challenges to organizational mandates and values, and strained relations with key protection stakeholders. International actors supporting (or willing to support) CSP therefore face a dilemma: whether to try to enhance their effectiveness and legitimacy by “localizing” protection, given that this may create new risks and challenges and/or compromise their organizational identity. While this dilemma is inherent in external protection assistance and any organization is likely to face it, we find that organizational type can impact both how unintended consequences are experienced and how the risk of their occurrence is managed. Our analysis highlights the importance of actor embeddedness: organizations that are closer to the communities they work with are in a better position to minimize these unintended consequences and manage the risks inherent in supporting CSP.

In focusing on the risk of unintended consequences for external actors engaged in supporting CSP, we do not seek to suggest that these risks are greater or more severe than those associated with top-down intervention. Nor do we assess the overall effectiveness of CSP, or whether it is as effective as direct protection by external actors. However, it is important to acknowledge that efforts by organizations to mitigate the risks of supporting CSP may also constrain deeper engagement with local protection structures, potentially limiting the effectiveness of CSP efforts. As we discuss in the conclusion, future research should evaluate the implications of this trade-off for practice and theory. More broadly, given the risks we identify and analyze, researchers should consider whether efforts to “localize” or embrace bottom-up solutions in other policy domains generate similar kinds of unintended consequences.

The paper proceeds in four steps. First, we conceptualize international support for CSP as purposive and mediated action that potentially gives rise to unintended consequences, and then develop a framework for understanding the dilemma confronting external actors in conflict. Second, we present our research design, discussing case selection as well as our empirical source material. The next two sections present our empirical findings, while our conclusion discusses some of the implications of our analysis and highlights opportunities for further research.

Conceptualizing the Dilemma Facing International Actors

International support for CSP can be conceptualized as “purposive social action,” which entails explicit motivations and involves conscious policy or institutional choices (Merton Reference Merton1936, 895). External actors support CSP in an attempt to enhance the legitimacy and effectiveness of protection policies and programs while avoiding the pitfalls and costs of direct intervention. Yet as a form of mediated action in a dynamic and complex social context, international support for CSP presents a dilemma: supporting community actions leaves external actors vulnerable to negative unintended consequences—some of which could contravene their organizational identities and values.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a dilemma as a situation “in which a difficult choice has to be made between two or more alternatives, especially ones that are equally undesirable.” Our conception borrows from recent works in the field of conflict studies (e.g., Hegghammer Reference Hegghammer2013; Hoover Green Reference Hoover Green2018), which describe dilemmas as situations of competing imperatives. In our case, the imperative to shift from top-down protection to supporting local actors exists alongside the need to avoid negative unintended consequences.

This dilemma is distinct from the general challenges linked to external protection programming—such as resource constraints, logistical barriers, lack of political support, weak coordination among external actors, and security concerns—in two main ways. First, inaction is rarely a viable option for organizations with a protection mandate. Many organizations must therefore choose between direct engagement or support for CSP, which carry different risks. Second, while the more general challenges associated with protection programming usually entail political, financial, and logistical constraints that are beyond the organization’s direct control, the dilemma associated with supporting CSP implicates an external organization more directly: it largely stems from the consequences (or potential consequences) of the assistance this actor decides to give (or not give).

Understanding Unintended Consequences

The idea that actions can have unexpected outcomes dates back to Adam Smith and John Locke; sociologists and economists popularized it in the twentieth century (Merton Reference Merton1936; Reference Merton1968; Peltzman Reference Peltzman1975). Baert (Reference Baert1991, 201) defines an unintended consequence as “a particular effect of purposive action which is different from what was wanted at the moment of carrying out the act.” Some distinguish unintended consequences (a core focus of economics) from unanticipated consequences (a core focus of sociology and public policy). The latter can be defined as consequences that an actor “had not thought of at the moment of carrying out the act” (206). However, the two terms are often conflated, and the former has largely eclipsed the latter in popular usage (compare Merton Reference Merton1936; Reference Merton1968). While we employ the term “unintended consequences,” we accept the possibility of consequences that policy makers foresee but do not intend and agree that anticipating (or trying to anticipate) the outcomes of purposive social action is a core task of policy making (de Zwart Reference de Zwart2015).

Although all forms of purposive social action yield unintended consequences, we expect two specific features of international conflict engagement, and particularly external support for CSP, to increase their likelihood. First, external actors to a conflict have the potential to alter communities’ dynamics and equilibria, particularly between civilians and armed groups, in ways that can be difficult to foresee (Aoi, Coning, and Thakur Reference Aoi, de Coning and Thakur2007; Donini Reference Donini2012). Second, many conflicts feature what Rubenstein (Reference Rubenstein2016, 88) calls “dramatically distributed agency”—a situation in which the consequences of policy interventions are the result of the actions of various agents with a range of intentions and objectives who do not necessarily act or plan together. In the case of humanitarian assistance, Rubenstein argues that this gives rise to the problem of “spattered hands” (as opposed to “dirty hands”): even though there may be no specific prior knowledge that an actor’s purposive action could contribute to a particular outcome, actors (should) know that other actors could exploit or leverage their involvement for problematic ends.

International actors in conflict contexts therefore find it challenging to anticipate how others will use or leverage their involvement, since local actors heavily mediate policy interventions (Dobos Reference Dobos2012; Pattison Reference Pattison2015; Salehyan Reference Salehyan2010) and can substantially affect the degree to which external actors meet their objectives. As a result, international efforts to help local actors assert or strengthen their protective agency could be a double-edged sword. Although empowering local actors may boost legitimacy and effectiveness at a lower cost, embracing bottom-up protection can also create unintended consequences, given the potential lack of control over local civilians’ behavior and choices.Footnote 3 What is more, the fluidity of identities in contexts of armed conflict—that is, the fact that civilians often play multiple roles as victims, survivors, protectors, and even perpetrators of violenceFootnote 4—makes this social system even more dynamic and complex (Fujii Reference Fujii2009; Masullo Reference Masullo2021; Utas Reference Utas2005) and the effects of policy interventions difficult to predict (Brusset, Coning, and Hughes Reference Brusset, de Coning and Hughes2016).

While most typologies of unintended consequences discuss unexpected benefits (see Baert Reference Baert1991), we focus on three main forms of negative unintended consequences. The first is an unexpected drawback—a detrimental effect that occurs in addition to the desired effect. An example from the protection domain is an external actor that distributes cell phones to community members so they can protect themselves through early warning, but then they also use the phones to organize and coordinate illicit activity.

The second type of unintended consequence, a perverse effect, is an effect contrary to what was originally intended—for example, if support for CSP makes individuals less secure and diminishes their capacity to self-protect. Although perverse effects are, by definition, outcomes that undermine (or even contradict) the original intentions of an intervention, it is important to recognize that they can coexist with desired outcomes. While at a macro level an intervention might achieve its overarching goal, such as reducing community vulnerability, at a micro level specific groups or individuals might experience increased risks or harm, leading to what we refer to as “differential effects.” Thus the same intervention can produce positive outcomes for some and unintended negative consequences for others simultaneously.

A perverse effect from the phone example above would be if an armed group tracked the locations of civilian calls and subsequently targeted individuals or communities. Some conflict scholars employ principal–agent theory to illuminate how such effects can arise from “delegation,” especially where foreign actors back local rebel groups (Karlén et al. Reference Karlén, Rauta, Salehyan, Mumford, San-Akca, Stark and Wyss2021; Salehyan, Siroky, and Wood Reference Salehyan, Siroky and Wood2014). Perverse effects in this context can occur through “adverse selection,” whereby external states (the “principal”) lack information about the reliability or competence of local armed groups (the “agent”) and choose those that are less likely to be successful. They can also stem from “agency slack”—when local rebels take actions that are counter to the preferences or goals of their foreign supporter (Salehyan Reference Salehyan2010). The latter form of perverse effect can also result from “moral hazard,” when one party becomes involved in risky activities knowing that another actor will incur the cost (Kuperman Reference Kuperman2008).

While we entertain the possibility that perverse effects may be an unintended consequence of international support for CSP, we do not explicitly apply principal–agent theory. Though this framework has explanatory power in examining proxy warfare and external support for rebel groups, international efforts to support CSP are commonly conceived as a form of empowerment, rather than delegation. Civilians are reasserting their agency and often taking responsibility for their protection in contexts where neither state security forces nor international actors are able or willing to do so. Nevertheless, even well-intentioned efforts to empower civilians can generate perverse effects that create a dilemma for international actors engaged in supporting CSP.

Finally, in some instances perverse effects can be so substantial that they generate a third form of unintended consequences: complicity, defined as the “fact or condition of being involved with others in an activity that is unlawful or morally wrong” (Jackson Reference Jackson2015). We expect this type of unintended consequence to be especially problematic for IOs and NGOs that have identities closely intertwined with normative goals and values (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; von Billerbeck Reference von Billerbeck2020; Wong Reference Wong2012), and whose legitimacy could be jeopardized if the practices adopted by the local actors they support challenge or even contravene those values. In the latter case, such practices would not only be contrary to an organization’s “preferences” but pose a clear risk to its core identity.

For an actor to be complicit, it needs to knowingly contribute to a wrongdoing—even if it seeks to perform a greater good.Footnote 5 How an actor contributes to wrongdoing is also critical. For example, a state that knowingly provides support for another state’s commission of genocide should be held responsible for assisting an act of genocide, but not for the genocide itself (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, 3). Complicity is thus derivative: it ties the conduct of a secondary actor (in our case, the external actor) to the wrongdoing of the primary actor (the local civilians). External actors need not share the local agents’ intention or purpose; complicity requires only that they know, or should have known, that their actions are contributing (or could contribute) to harm or wrongdoing (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, 50–51; Lepora and Goodin Reference Lepora and Goodin2013, 79). While a legal conception of complicity often entails a shared intention to engage in wrongdoing, we are interested in a moral conception, which has weaker standards for invoking responsibility. The risk for IOs supporting CSP efforts is therefore not that they will become “coactors” actively participating in wrongdoing, but rather that they might facilitate transgressions by local actors.

Why Unintended Consequences Emerge

While different contexts may be more (or less) likely to generate unintended consequences, many of the primary explanations from sociology, economics, and political science focus on agent-centric factors (Baert Reference Baert1991; Merton Reference Merton1936; Nielson and Tierney Reference Nielson and Tierney2003; Salehyan Reference Salehyan2010).Footnote 6 Building on this literature, we posit three reasons why international actors that support CSP are likely to generate negative unintended consequences.

The first is ignorance, or what is sometimes referred to as “epistemic uncertainty.” We expect that international actors’ lack of knowledge of a conflict country’s social, political, and economic context—or of how local actors might respond to their efforts to support self-protection—will make it difficult for them to anticipate unintended consequences. Features that could increase the likelihood of such ignorance include language barriers, cultural differences, frequent staff rotation, lack of access or sustained field presence, and inadequate time to reflect on the possible outcomes of an action. The second factor is external actors’ pursuit of short-term goals or interests. Given that protection programming, including support for CSP, is often concerned with immediate threats to individual physical safety and integrity, international actors may focus excessively on short-term intended consequences and not on the longer-term or adjacent effects of their policies. A third reason for unintended consequences is the dominating influence of what Merton calls “basic values.” Those engaged in purposeful social action are frequently “not concerned with the objective consequences of their actions but only with the subjective satisfaction of a duty well-performed” (Merton Reference Merton1936, 903; emphasis added). The normative mission or “good” intentions that motivate an international actor to support CSP may therefore prevent it from fully considering the follow-on consequences of its actions, given the perceived benefits and legitimacy of empowering communities to self-protect.

These three factors do not operate in isolation; they influence organizations’ decision-making processes in complex ways. For instance, ignorance about local dynamics can cause external actors to engage in actions that are misaligned with an area’s key protection risks, that overestimate the likelihood that certain protection strategies will succeed, or that neglect intervening factors that can undermine or alter the effects of those strategies. Meanwhile, the pursuit of short-term goals may prioritize immediate protection outcomes over long-term effects. International actors’ organizational values may also overshadow practical considerations on the ground. Each of these factors can prompt organizations to take well-intentioned actions that inadvertently disrupt local practices, empower some actors over others, or even cause harm—thus linking the conditions to the manifestation of unintended consequences.

The Role of Organizational Type

Although these three factors suggest that the risk of unintended consequences will be relevant for all external actors that support CSP, we expect organizational type to affect the strength of these factors—and hence both the prevalence of negative unintended consequences and how the risk of such consequences are managed. General research on international institutions (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019; Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal Reference Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal2001; Voeten Reference Voeten2019) and NGOs (Slim and Bradley Reference Slim and Bradley2013) suggests that particular organizational features—such as the source and scope of their mandate, or their degree of autonomy from states—shape how such organizations and their staff behave (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Bradley Reference Bradley2016; Wong Reference Wong2012), including how they engage with relevant stakeholders, how they address challenges related to their programming, and the space they have to innovate (Campbell Reference Campbell2018; Li and Farid Reference Li and Farid2023; von Billerbeck Reference von Billerbeck2020).

We build on these previous studies to posit four organizational dimensions that are likely to be important in determining both the prevalence of unintended consequences and how the risks are managed. The first dimension (what we call the breadth of mandate) is whether the organization is multimandated or single mandated (i.e., focused exclusively on protection). This dimension can affect the types of resources that are dedicated to supporting CSP, assessing potential risks, and envisioning possible risk management strategies. In our analysis, resources primarily refer to human and logistical capacities, as the organizations rely on personnel and field presence to implement CSP strategies. Financial and equipment resources are implicit but not the focus of our analysis, which centers on how staffing levels, expertise, and organizational mandates impact CSP support. We expect organizations with a single mandate to be better at anticipating risks than those that cover multiple policy objectives, and to be better able to limit the scope for local civilians to pursue actions that diverge from the organization’s core objectives. Conversely, we expect multimandate organizations to be more likely to focus on the short-term intended effects of support for CSP as they have less bandwidth to reflect on long-term consequences and/or may be focused on other priorities.

The second dimension, constitution, captures whether the organization is intergovernmental (state mandated) or nongovernmental (self-mandated). The type of relationship between the organization and the host state (and other states) could determine how much leeway an international actor has when supporting CSP. We expect IOs to be more limited than NGOs in choosing which communities and CSP strategies to support since some community initiatives—particularly those relating to nonstate armed groups—might be perceived as challenging state authority. Supporting such initiatives might also create tensions between the international actor and host state, possibly resulting in diminished access to civilians and thus a greater likelihood of epistemic uncertainty.

The third dimension, degree of embeddedness, denotes the organization’s temporal and spatial proximity to the local population and context. It could affect an organization’s knowledge (or lack thereof) of conflict dynamics and social or cultural norms as well as its level of oversight of local actors. We expect embeddedness—through, for example, a sustained field presence in local communities—to improve the ability of organizations to foresee, identify, and even mitigate the potential risks of supporting CSP. Embeddedness may also reduce the likelihood of short-termism, as the follow-on or adjacent effects of support could be harder to ignore when an organization is present in the community and can thus more readily see (or receive information about) the effects of its actions. Relatedly, embeddedness is likely to lessen the potential influence of basic values. The inherent “goodness” of the goal—supporting CSP—and the “subjective satisfaction of a duty well-performed” (Merton Reference Merton1936, 903) are arguably harder to prioritize and sustain when an organization is more proximate to local actors and aware of the potential negative consequences of its support. A high degree of embeddedness entails a sustained and close physical presence in local communities, such as staff members living and working directly among those they support. Moderately embedded organizations maintain a regular presence in local communities, although staff may not be fully integrated or spend extended periods on the ground. Organizations with a low degree of embeddedness engage with local communities primarily through remote interactions and short deployments or field visits.

The last dimension considers whether an organization’s decisions are made at the local level or at central offices or headquarters. This degree of centralization will likely affect the field staff’s level of autonomy and readiness to adjust to the potential or actual risks associated with supporting CSP. We expect local staff in decentralized organizations to feel more responsible for their actions and thus to be more likely to consider the potential consequences, thereby reducing the likelihood of short-term thinking and the dominating influence of basic values. Staff in decentralized decision-making structures should also be swifter and more agile at managing risk than those in more centralized settings, as there is less need to consult multiple levels of governance.

Research Design

To investigate whether (and what types of) unintended consequences manifest in this policy domain as well as the potential impacts of organizational type, we explore the experiences of four IOs that have supported CSP in various conflict settings. We analyze their internal and public documents, original interview data, and the results of an in-person workshop with staff members of each organization.

Case Selection

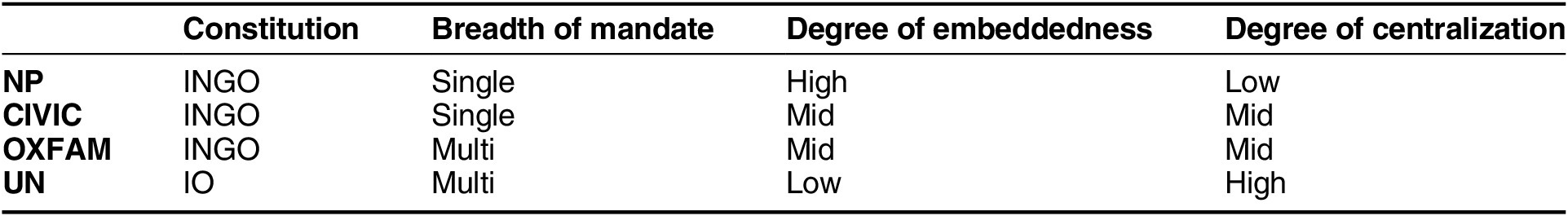

To select our cases, we first identified a universe of cases comprised of IOs that have supported CSP. From this pool, we looked for diverse organizations that exhibited variation across the four key organizational dimensions discussed above. This variation was necessary for (1) determining whether the risk of unintended consequences is a general issue related to supporting CSP or one driven by specific organizational features, and (2) assessing whether (and how) organizational type might affect the prevalence of factors that generate unintended consequences and affect actors’ ability to manage the risk of their occurrence. From the remaining organizations, we then selected those that have been significant in the international move toward supporting community-based programming since they are likely to have the most extensive experience with CSP and to influence future programming in this area by other organizations. Our final four cases were Nonviolent Peaceforce, the Center for Civilians in Conflict, Oxfam, and the UN (table 1).

Table 1 Case Selection: Organizational Variation across Key Dimensions

We acknowledge that variation in dimensions unrelated to organizational type (e.g., the type of armed conflict, the nature of armed groups, or the host country’s regime type) might also affect how international actors experience the risk of unintended consequences. However, since we are primarily interested in assessing the general prevalence of unintended consequences for actors supporting CSP, we use the organization as our unit of analysis and thus prioritize covering a range of organizational types. This choice is also consistent with the sociology and political science literatures on unintended consequences, which mainly focus on agent-centric factors.

To address the possibility that these contextual factors might drive our findings, we chose organizations that have operated in multiple and diverse conflict settings and explored their experiences supporting CSP in different conflicts. This allowed us to probe whether an organization faces the same risks across all conflict situations or if some risks are linked to a particular context. Since some of the organizations we study have supported CSP in the same conflict settings, this allows us to probe whether some of the challenges faced by multiple organizations arise from the same conflict type. However, rigorously investigating how different conflict types might affect these dynamics is beyond the scope of the paper.

Overview of the Cases

Nonviolent Peaceforce

Founded in 2003, NP is an international NGO (INGO) with a single mandate: to protect civilians in violent conflicts through unarmed strategies. Guided by the principles of “civilian-to-civilian action” and “the primacy of local actors,” NP staff work side by side with communities, an approach it calls Unarmed Civilian Protection (NP 2015; 2022). Unarmed Civilian Protection comprises four main activities: protective presence and accompaniment of civilians, relationship building within communities, capacity development programs to strengthen self-sustaining local protection infrastructure, and monitoring (e.g., ceasefire monitoring, rumor control, establishing early-warning systems) (NP 2020b). Unarmed Civilian Protection is practiced by civilian teams comprised of local and international staff, including members of violence-affected communities (NP 2020c). These field teams are firmly embedded in local communities: most staff members live in the areas where they support communities and have high degrees of local decision making (NP 2020a). NP operates in South Sudan, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Thailand, Ukraine, Iraq, Indonesia, Myanmar, the US, and the Philippines.

The Center for Civilians in Conflict

Founded in 2003, CIVIC is an INGO with the single mandate to prevent, mitigate, and remedy civilian harm in conflict by “support[ing] communities affected by conflict in their quest for protection and strengthen[ing] the resolve and capacity of armed actors to prevent and respond to civilian harm” (CIVIC 2020, 9). Community representatives lead Community Protection Groups, which aim to reduce civilian harm by disseminating knowledge about CSP strategies, advising individuals on accessing government and NGO resources, and advocating for community protection needs with armed actors (CIVIC 2019). CIVIC assists Community Protection Groups by establishing their terms of reference, developing communication channels with armed actors, and providing technical assistance to create protection strategies such as early-warning systems or evacuation plans (Aslami Reference Aslami2019; CIVIC 2019;2020). CIVIC is well embedded in local communities and has a sustained presence in its core areas. It prepares for its community-based protection work by conducting in-depth research into civilians’ needs and current CSP strategies (CIVIC 2017; 2020, 11). Decision making is somewhat centralized: key decisions are made at headquarters, but local offices retain some leeway for day-to-day decisions. CIVIC operates in Mali, Nigeria, Niger, and other countries in the Sahel, as well as in the DRC, Central African Republic (CAR), South Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Ukraine, and East Africa.Footnote 7

Oxfam

Oxfam is a multimandated INGO that seeks to “fight inequality to end poverty and injustice” (Oxfam 2021a). In 2016, it made protection a central function of its humanitarian action through a practice it refers to as “safe programming.” Oxfam supports communities’ “capacity for self-protection” by helping to develop community protection plans, using physical presence to deter threats, providing referrals to emergency medical care and legal assistance, and engaging with local authorities (Hastie and Duch Reference Hastie and Duch2017, 4; Hastie and Swithern Reference Hastie and Swithern2008, 33; Oxfam 2021b). Its community-based protection approach entails the cocreation of new structures that incorporate existing protection strategies and/or support formal organizations as registered partners. In many contexts, this takes the form of Community Protection Committees, which are typically comprised of 10 volunteers who vary in gender, age, and social status (Lindley-Jones Reference Lindley-Jones2018, 1; Oxfam 2021b). Oxfam’s degree of embeddedness is characterized as mid-level. While it works closely with communities in typically multiyear projects, its staff members have a less sustained physical presence within communities. Its decision-making structure exhibits mid-level degrees of centralization. Oxfam has standalone community-based protection projects in various contexts, including the DRC, CAR, Bangladesh, and Lebanon (Hastie and Duch Reference Hastie and Duch2017, 3; Oxfam 2021b).

The United Nations

The UN is an IO with a broad and multidimensional mandate that includes maintaining international peace and security, promoting and protecting human rights and ensuring the protection of civilians, and facilitating social and economic development. We focus on UN peacekeeping operations; in these types of operations, the core top-down approach to protection has evolved over the last decade to include more bottom-up community-based elements in settings such as South Sudan, the DRC, CAR, and Mali. UN missions there have created new structures and mechanisms to support CSP and deepen community engagement.

In some settings, the UN has hired local staff to serve as Community Liaison Assistants to support communication between the mission’s military component and local communities. Community Liaison Assistants work closely with Community Alert Networks, which were created to notify peacekeepers and authorities of imminent protection threats and reinforce “the capacities of communities to protect themselves” (DPO 2020, 97). In other contexts, the UN has supported protection structures that predate the conflict and/or have been developed by communities in response to conflict-related threats. UN peacekeepers have also provided training and material resources to Community Watch Groups in South Sudan, established by communities living in Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites, which serve as early-warning networks and routinely mediate communal disagreements. While UN missions have direct contact with local communities, particularly during crises, the relationship can be fleeting and staff are generally less embedded within communities. Military units are deployed to bases and are often prohibited from fraternizing with locals, while civilian staff are concentrated in urban areas and at national or regional headquarters. The organization’s decision making is highly centralized; field staff have less autonomy than those in the other IOs studied. While the UN is unique in that its peacekeeping missions include an armed component, we focus primarily on the civilian staff—who are a crucial element of its integrated approach to protection—and their engagement with CSP. Nevertheless, our analysis addresses the challenges generated by the presence of armed peacekeepers, which distinctly shapes the UN’s support for CSP.

Data Sources

Our empirical analysis draws on a combination of primary and secondary sources and testimonial data. We first systematically searched documents generated by our selected organizations and retrieved over 140 policy documents, reports, and programming reviews. While most documents were publicly available, we also reviewed internal documents that were particularly important given the possible incentives not to make public any information about negative unintended consequences.Footnote 8 To complement this information, between 2020 and 2023 we conducted 36 semistructured interviews with current and former staff members of the four organizations, including senior staff operating at headquarters and on-the-ground staff from country offices.Footnote 9

In addition, in February 2020, we held an in-person workshop under the Chatham House Rule in Montreal with representatives of our case organizations to probe their experiences supporting CSP in a more interactive setting. Representatives of organizations not in the sample also participated in this workshop, which allowed us to further explore the extent to which challenges related to unintended consequences were common across organizational types. This workshop was instrumental in strengthening our rapport with the four organizations, which helped us to gain access to conduct subsequent interviews on sensitive topics. Complementing primary sources with testimonial data was a fruitful technique, given that unintended consequences associated with well-intentioned protection programming is a complex and sensitive issue for organizations; staff rarely discuss it in public writing or in “cold” interviews. We are confident that working intensively with these organizations for over two years enabled us to build the trust and rapport needed to discuss risks and challenges more openly.

Our theoretical expectations, derived from the literatures on unintended consequences and IOs, structured our examination of primary documents as well as our interview guides. Interviews were also used to investigate insights gathered in public and internal documents that pointed to the possibility of unintended consequences. We sought to determine whether each organization encountered or foresaw the forms of unintended consequences that we theorized, and to understand the different ways in which they came about. In addition, we examined how aspects of each organization’s structure might have contributed to the prevalence of unintended consequences and collected information about whether (and how) they managed the risk of such consequences. We used the same questions across all four cases to collect comparable data.

To investigate how organizations experience the risks of supporting CSP and how they try to prevent or mitigate them, we analyzed material they created and interviewed their staff. We are aware that CSP and some of the unintended consequences we highlight directly and indirectly impact communities and the states where these organizations operate. To understand whether different types of international actors face these challenges, we worked in close cooperation with the organizations themselves. Further research should also include the voices of communities and partner states, especially when assessing the impact of international actors’ work in supporting CSP.

The Unintended Consequences of Supporting CSP

Our findings confirm the expectation that support for CSP entails risk. More specifically, we identified three types of negative unintended consequences for our case-study organizations across a range of conflict settings: increased vulnerability and insecurity for local communities, a challenge to organizational mandate and values, and strained relations with key stakeholders. In some instances, the organizations were able to foresee and mitigate potential unintended consequences, while in others they were identified afterward in internal assessments. This section discusses each type in turn using illustrative examples from the cases and explains how they create a dilemma for international actors supporting CSP.

Increased Vulnerability and Insecurity

The programming or presence of the external actor can unintentionally make individuals and communities engaged in self-protection less secure.Footnote 10 We found three sets of circumstances that can give rise to this perverse effect.

First, vulnerability and insecurity can increase when international support shapes the perceived affiliation of the person or population being supported. This can cause an individual or community to be targeted, including in retaliation. Supporting a given CSP strategy can give unwanted visibility to a community or send a signal (albeit mistakenly) about its loyalty. For example, when the UN established Community Alert Networks in the DRC, UN staff distributed phones and radios to Community Alert Network focal points near its bases; community members were expected to contact the mission to report threats. However, individuals who were given phones were potential targets for retaliation and reprisals. In response, the mission stopped providing phones and created a toll-free number that local residents could call (Henigson Reference Henigson2020, 21).

UN staff also recounted instances of retaliatory attacks against community members who shared information with the UN about threats in the DRC, CAR, South Sudan, and Mali.Footnote 11 UN documents provided evidence of this perverse effect. The Protection of Civilians handbook openly recognizes that “[community] engagement with the peacekeeping mission may stigmatize or even endanger communities, where an armed actor considers such engagement to be a threat” (DPO 2020, 108). Several interviewees highlighted Mali as a particularly risky context given the UN’s perceived partiality to the state; one official noted that “reports about communities suffering retaliation after receiving a field visit are plentiful … retaliation is real.”Footnote 12

The other cases also featured this form of unintended consequence. CIVIC confronted similar issues in Afghanistan, where supported individuals and communities engaged closely with former president Ashraf Ghani’s government but not with the Taliban.Footnote 13 These communities—and, by extension, CIVIC—risked being perceived as partial by nonstate armed groups, which had problematic effects when the conflict dynamics shifted in 2021 and the organization had to withdraw from the country. A former staff member explained that CIVIC’s departure not only shaped perceptions of the organization’s agenda; it also risked “put[ting] the groups on the ground in a bad light for having cooperated with us. … Questions could be raised by the Taliban, and they may make some assumptions about the affiliations of local populations.”Footnote 14

Second, the cessation of external support can increase vulnerability and insecurity. NP and Oxfam reported increased risks to individuals after their programs ended and they left a location. An internal assessment of programming in the DRC stated: “In most conflict-affected areas it was recognized that the formal structures of the protection committees meant that individuals were at risk of being targeted with violence or intimidation when the official project finished and Oxfam and partners were no longer physically present to support ongoing activities” (Green Reference Green2015, 10). While the study found that “serious attacks on project activists” did not materialize, members of protection committees did receive verbal threats such as “now you feel confident but wait until Oxfam is gone and we’ll see” (6). Further, the study reported that the perception of increased vulnerability persists within some communities when a program ends, underscoring how external support for CSP fundamentally alters local dynamics. A former NP staff member shared similar concerns, noting that such risks were heightened in the few instances in which the organization had to withdraw from or decrease its presence in an area due to insecurity or denial of access from authorities.Footnote 15

A final way in which international support can inadvertently increase vulnerability is through moral hazard: local civilians may expose themselves to greater risk because they expect the external actor to bear the costs and/or expect that additional support will be forthcoming. For example, several officials involved in the UN mission in the DRC recounted how expectations were raised within communities that believed—and by some accounts were led to believe—that the presence of a Community Alert Network or Community Liaison Assistant offered a “direct line” of communication to peacekeepers in times of crisis.Footnote 16 However, the mission did not always respond to warnings of impending violence. In Mutarule, South Kivu Province, civilians repeatedly called the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) for assistance during a massacre using mobile phones given to them by peacekeepers (Paddon Rhoads Reference Paddon Rhoads2016). While we focus on the UN’s civilian staff, this example illustrates how the presence of armed peacekeepers can complicate CSP support by creating unrealistic expectations among communities regarding the protection capabilities of armed forces. This distinction underscores the complexities of comparing the UN to smaller INGOs without armed personnel, raising the question of whether the existence of the Community Alert Network—and the expectations of protection it engendered—led civilians to abandon self-protection strategies that may have served them better than those developed in conjunction with international actors.

Challenges to Organizational Mandate and Values

CSP can also inadvertently undermine an organization’s mandate and values due to the sociocultural norms and practices involved in local self-protection strategies. This mostly took the form of “unexpected drawbacks,” which constitute negative effects for international actors in addition to the desired effect of strengthening CSP. However, in a few instances international support also created the potential for perverse effects or complicity in wrongdoing. We found two areas where the risk of this unintended consequence was prevalent: where support reinforced authorities’ abusive practices, and where it reinforced gender inequalities.

Constructive engagement with authorities and “duty bearers”Footnote 17—including chiefs, elders, and local and national state institutions—is a priority for several of the protection structures established and/or supported by the four organizations we examined. Although such engagement is not problematic per se, in some instances support for CSP inadvertently reinforced the controversial practices of those authorities. For example, in the Hauts Plateaux, a mountainous and inaccessible region in eastern DRC, Oxfam Community Protection Committees referred cases normally adjudicated in court to local chiefs. An Oxfam staff member reported that this policy ended up “shoring up the power and rent-seeking opportunities [the chiefs] traditionally enjoyed” (Green Reference Green2015, 8). Similarly, in Boga, a remote area in northeastern DRC, Oxfam staff recounted that village chiefs—elected by the community as “change agents” to expand the geographical impact of the Community Protection Committees’ work—illegally demanded money from residents.Footnote 18

We also found evidence that clashes with organizational mandates can create the risk of complicity. In South Sudan, for example, the potential for complicity partly explains the UN’s reluctance to support customary courts operating in PoC sites.Footnote 19 Although these sites offered a critical form of protection for many individuals,Footnote 20 court punishments and sentences relied on judgments and methods that could be harmful to civilians. In some instances, sentences resulted in beatings, canings, and forced relocation, and some survivors of sexual assault were forced to marry their attackers (Ibreck and Pendle Reference Ibreck and Pendle2017). Similarly, UN staff in PoC sites denied requests from Community Watch Groups for containers in which to detain people to avoid becoming complicit in unlawful detention practices (Paddon Rhoads and Sutton Reference Paddon Rhoads and Sutton2020).

NP grappled with similar risks in South Sudan. A staff member recounted an instance in which differences in how the organization and local protection committee members conceived of protection and sexual and gender-based violence presented a risk of complicity. NP learned that “displaced women who were seen as unfaithful (often because they had been raped) were being caged upon their return home.”Footnote 21 When the local protection committee asked NP to assist with returns, it “couldn’t in all good conscience” support the request, given what it knew about local practices. NP instead questioned the need for the return process and whether it was an appropriate measure.Footnote 22 This example illustrates a broader tension: where organizational values conflict with local protection practices, external actors may adopt more cautious approaches that prioritize minimizing organizational risks. While this approach protects the organization from complicity in harmful practices, it may also hinder deeper engagement with local protection structures, impacting CSP effectiveness.

Gender inequality is the second area where external support can reinforce norms and practices that challenge organizational mandates and values. All four organizations center gender in their protection programming and the importance of women’s participation in community structures and practices. Oxfam and NP have established all-female protection committees in certain contexts, CIVIC has “quotas” or “minimums” for female representation in its protection groups, and the UN actively recruits female Community Liaison Assistants. Nonetheless, each organization has grappled with instances in which supporting CSP has reinforced (or had the potential to reinforce) gender inequalities in contravention of the organization’s mandate.

In South Sudan, the UN’s support for Community Watch Groups in the PoC sites led to charges that it was condoning gender inequalities and a culture that pays little heed to female protection concerns. The UN allowed community members to nominate Community Watch Group members to ensure that communities retained decision-making power, but they mostly nominated men. While the UN advocated female participation, in some PoC sites the community resisted such efforts.Footnote 23 This form of unexpected drawback has been particularly prevalent where patriarchal norms are deeply entrenched. In Afghanistan, CIVIC had a target of 30% female participation in its Community Protection Groups, but staff stressed the challenges of “bringing women into the [protection] groups, especially in rural areas,” noting that women initially did not want to participate, as socially and culturally there was “less acceptance of them playing a role.”Footnote 24

Strained Relations with Protection Stakeholders

Finally, external support for CSP can unintentionally strain an organization’s relationship with the stakeholders involved in protection. These stakeholders encompass a broad range of state and nonstate actors, including national and local governments, NGOs, community leaders, and civilian populations.

Directly supporting specific subgroups in a community, such as women or members of a particular ethnic group, can create tensions within communities as well as between the organization and communities. This effect becomes particularly salient when international actors’ programming seeks to overcome inequalities, transform traditional social roles, and empower specific subgroups. It also emerges indirectly, for example if external actors support existing community protection strategies that are targeted and thus exclusionary (e.g., strategies designed by and for specific social groups, such as initiatives to create all-women protection structures). While increasing female participation in household and community decision making by enhancing the role of women in protection work is a seemingly positive development, staff members from the organizations we studied observed that increasing women’s involvement sometimes diminished men’s sense of self-worth, which created tensions within communities and hostility toward the organization. An Oxfam report noted the problematic effects of support strategies “primarily focused on opportunities—economic, social and political—for women, without creating positive opportunities for men, at a time when alternatives to participation in armed violence are needed more than ever, particularly for young, unemployed men.” The report describes a “crisis of masculinity … exacerbated by aid agencies’ almost exclusive focus on women” (Fanning and Hastie Reference Fanning and Hastie2012, 5–6). Oxfam staff observed that women were particularly attuned to this backlash and resulting tensions. They would repeatedly say, “That’s great for me—but what about my husband, what about my son, they matter too.”Footnote 25

Relationships with stakeholders can also be undermined if an external actor pursues activities beyond the scope of its protection mandate—what some refer to as “mission creep”—or if there are conflicting conceptions of protection.Footnote 26 Either situation can lead to a breakdown in trust between the community and the organization, and negatively impact the latter’s reputation. For example, in some contexts Oxfam-supported protection committees engaged in domestic violence mediation and made arbitrary arrests, for which they were neither trained nor equipped, and which fell beyond the organization’s purview. One Oxfam employee reported that “[r]ole expansion is absolutely a problem” and that “we are shaping or nudging [people] in what we think they should do, and there are all sort of issues with that. But what happens when they want to work on something we think is completely inappropriate?”Footnote 27 Another Oxfam representative articulated the core tension that can arise over differing interpretations of protection: “We should let communities decide what protection is, yet this risks losing our original intent. Oxfam has a dilemma between its participatory and inclusive approach, and its need to guard what protection is. [What we take as protection] cannot be completely open-ended.”Footnote 28 A senior member of the organization explained that the example of protection committees engaging in mediation “gets to the heart of the dilemma: how much control to cede, who gets to decide what is a threat, and what is protection.”Footnote 29

Lastly, in some contexts, supporting CSP strategies can strain relations between external organizations and state authorities that disapprove of community-based programming. A deterioration in these relationships can jeopardize grassroots protection work and cause organizations to be denied access—both of which can increase insecurity for civilians and prevent external organizations from engaging in other (potentially more effective) protective measures. As a senior UN civil affairs officer explained, “In South Sudan and DRC—either by design or by fear that the mission is ‘trying to do something behind their back’—government opposition can trickle down to the local level” in ways that make operations more difficult.Footnote 30 While a worsening of relations with state authorities was most prominent for the UN, which as an intergovernmental organization works in tandem with national authorities, we also found evidence of this dynamic among INGOs. For example, CIVIC officials stressed that they need host government authorization to operate, and thus support for CSP also needs government approval. This prevented it from working with communities that engaged with the Taliban in Afghanistan, which interviewees believed would have enhanced community protection.Footnote 31 NP and Oxfam staff spoke of similar challenges in Iraq and CAR. Our research design, which is based on organizational types (rather than types of conflict context), does not allow us to fully explore this challenge. However, all four organizations we analyzed exhibited the potential for tension with state authorities even though their programming took place in very different conflicts and regimes, which suggests this phenomenon could cut across conflict settings and regime types.Footnote 32 As one official put it, everyone needs to “maintain space for maneuver.”Footnote 33

The Dilemma Inherent in a “Risky Business”

Our analysis confirms that international actors supporting CSP do confront the dilemma that we theorize as inherent in this kind of mediated action. While the four organizations we examined recognize the importance of supporting CSP to improve the effectiveness and legitimacy of their protection work, they also acknowledge that doing so can generate unintended consequences that may increase civilians’ vulnerability, undermine their own mandate and values, and strain relations with key actors. This dilemma is present across various types of organizations and in countries and conflicts as different as Afghanistan, South Sudan, Iraq, CAR, and the DRC.Footnote 34

Nevertheless, this dilemma has not caused these organizations to abandon macrolevel support for CSP and community-based approaches, as these have become—or in NP’s case, have always been—fundamental to their mandates and core activities. Instead, we find that organizational staff grapple with the dilemma at the micro level by deliberating on how to manage the risks of providing support. As discussed below, the UN may prove to be an exception to that trend.

As for the form of unintended consequences, we uncovered relatively few instances that met our definition of complicity—that is, the actor knew (or should have known) that their support directly contributed to wrongdoing. In one sense, this is not surprising, given that organizational complicity goes beyond mere negligence. But other factors, related to the nature of our research, may also explain the difficulty associated with finding evidence of complicity. Organizations may naturally be reluctant to share information about instances that could give rise to complicity, given the reputational and institutional costs as well as the potential legal implications.Footnote 35 Yet our study also revealed that the nature of support provided by most external actors may make complicity less likely. Those actively participating in wrongdoing tend not to be civilians supported by external actors but rather other actors (e.g., armed groups, state security forces) who harm civilians.

Organizational Type, the Prevalence of Unintended Consequences, and Risk Management

Although our analysis reveals that each organization grapples with the dilemma at the heart of supporting CSP, our second main finding is that the experience of unintended consequences varies somewhat according to organizational type. The four organizational dimensions presented in the second section (i.e., constitution, mandate, embeddedness, and centralization of decision making) influence the degree to which the key agent-centered factors that give rise to unintended consequences are present. We find that deeper embeddedness and close local relationships allow organizations to reduce epistemic uncertainty through better understanding of the local context, early detection of inconsistencies and local tensions, and ongoing monitoring of local actors and the conflict context. Embeddedness also helps to prevent short-term thinking and the overriding influence of an organization’s basic values, as the long-term or adjacent effects of programming are more readily visible. For example, NP’s community embeddedness in South Sudan and deep knowledge of local practices helped its staff to foresee the risks of assisting with the return process.

While we assess the embeddedness of an organization as a whole, we find that the degree of embeddedness can vary within organizations and across contexts in ways that support our findings. For example, in the PoC sites in South Sudan, the UN—which typically engages in low levels of local embeddedness—was highly embedded (staff were colocated with civilians on UN bases). This proximity bolstered the UN’s knowledge of local dynamics and helped officials to be more discerning about who to support (e.g., deciding not to back customary courts due to the risk of complicity). Presence in these sites also enabled staff to monitor actors they supported, such as the local Community Watch Group, and adjust their support in response to potential risks (e.g., through efforts to increase female participation). In other contexts, where the UN is less embedded and relies more on remote networks (e.g., Community Liaison Assistants), epistemic uncertainty is greater and it is less able to monitor potential unintended consequences. Similarly, in Hauts Plateaux, where Oxfam was less embedded than in other contexts where it operates, it had less knowledge of local practices, and staff were less inclined to consider the possible negative effects of seemingly “good” programming given the difficulties associated with sustaining the organization’s presence in the area. Instead, the decision to support local authorities as “local change agents” was seen as a positive step toward expanding the geographical impact of the Community Protection Committees’ work.Footnote 36

Our findings also suggest that the constitution of an organization, along with its mandate and decision-making structures, can impact the prevalence of unintended consequences. We uncovered several instances in which the UN’s constitution, and specifically its relationship with the host state, hindered its access and thus increased the likelihood of epistemic uncertainty. Furthermore, its expansive mandate led to a focus on the short-term intended impacts of programming and neglected possible adjacent effects. The UN’s partiality to the host state and its state-building mandate, which inform its approach to protection, also meant that in some contexts antistate armed groups threatened and attacked civilians supported by the UN due to their perceived association with the organization. One official argued that the failure to identify this risk partly stemmed from “an over-reliance on the assumption that support for communities is inherently good” and compatible with the UN’s other policy objectives, thus neglecting how they may be at cross-purposes in some contexts.Footnote 37

Lastly, we detected some evidence that organizations with a decentralized structure, such as NP, are less likely to experience unintended consequences. In part, this is because staff feel a greater sense of responsibility for their decisions and are thus more likely to consider the adjacent and long-term effects of their actions. As discussed below, it is also because decentralized structures permit more rapid decision making and adjustments to programming and allow staff to depart from general templates to tailor their approach to the context.

In addition to impacting the prevalence of unintended consequences, our findings reveal that organizational type shapes how international actors supporting CSP manage the risks of such consequences. The clearest difference appears to be between the UN and the other organizations we analyzed, resulting from its status as an IO rather than an INGO, its modest degree of local embeddedness, its centralized decision making, and its multimandate constitution. All the UN sources we consulted cited harnessing sufficient local knowledge to engage effectively in CSP and address the risks of unintended consequences as a priority. Staff members, however, remarked on the challenge of sustaining a deep physical presence in local communities—even when missions are deployed over a long period.Footnote 38 “In most missions … it is very difficult to physically get to places,” recognized one former UN official. “You may have dozens of Civil Affairs Officers in a capital, but it is tough to get them to the countryside. Getting to remote places on a consistent basis is difficult.”Footnote 39 By contrast, NP and CIVIC often base part of their team in the areas where they support CSP.

The UN’s multifaceted mandate exacerbates these difficulties because not all its resources can be devoted to protection work, let alone to supporting CSP. As another UN official stated, “[T]he reality is that despite the large number [of staff], the resources in place are scattered, we are overstretched.”Footnote 40 Staffing shortages and rotations make it harder for personnel to build trust with local actors and acquire the contextual knowledge needed to understand the possible effects of programming. Compared with organizations like NP and CIVIC, which have single mandates focused on protection, multimandate organizations are more likely to need to diversify their resources to implement multiple activities and programs. Contrary to our expectation, Oxfam seems to have sidestepped this issue since protection is streamlined throughout its humanitarian activities. Staff members interviewed for this study described instances in which its diverse mandate, which includes programming on livelihoods, allowed the organization to build connections with communities that benefited from its support and from its monitoring of CSP.Footnote 41

Finally, the UN’s intergovernmental constitution has impacted its ability to manage the risk of unintended consequences. Several UN staff cited the importance of a UN mission’s relationship to the host state and the potential repercussions of being “too close” to certain communities by supporting CSP. As one official remarked, “No one is free to operate exactly as they wish. But a UN peace operation is set up to achieve something specific: giving communities more leverage but also recognizing that the main stakeholders are host governments. … There is constantly a tension in peacekeeping between the state-centric mandates we have (and that our key partner is the host government) and our softer people-centered approach. … The UN cannot just act with communities.”Footnote 42 Furthermore, in places like Mali and South Sudan, host governments dictate when and where mission staff can operate. Although INGOs also mentioned access concerns, they were far more pronounced for the UN given its intergovernmental constitution and relationship to the state. As discussed above, circumscribed access reduces epistemic certainty and can lead to short-termism.

Oxfam and CIVIC staff identified a different challenge, related to their constitutions, which affects their capacity to provide tailored CSP support and manage the risk of unintended consequences: the need for their donors to understand what they are funding. As one interviewee explained, while older practices of community-based protection were still largely driven by NGOs—as a way for “‘us humanitarians’ to train communities to do what we do, with our mindset”—supporting CSP requires NGOs to support what communities are already doing, “even if these activities do not correspond to what we usually do.”Footnote 43 In other words, for true CSP, the community must determine the nature and scope of the support. Yet donors require a clear breakdown of what they are financing and how resources are being deployed, which generates tensions for NGOs that are accountable to both donors and the communities they aim to support. This tension has arguably been less of an issue for NP, given its core principle of the “primacy of local actors” and the fact that its donors have long acknowledged and accepted that its work is “always community-led.”Footnote 44

Despite these differences, interviewees from all four organizations maintained that the dilemma associated with international support for CSP is largely unavoidable given the nature of the work. As an Oxfam staff member noted, “[T]he sheer complexity of the possible ripple effects of an action are relevant. A to B rarely happens—it almost never goes according to plan. … Uncertainty exists at such basic level, therefore [it] must be even more so with a more sophisticated program like support for civilian self-protection.”Footnote 45 Yet whether organizations view the dilemma as a barrier to the continued support of CSP also varies across organizations.

Given the perceived risks of negative unintended consequences, the UN has chosen to limit further expansion of its support for community-led protection, focusing instead on bolstering its community engagement and potential partnerships with NGOs that are better placed to manage the risks of CSP support.Footnote 46 Senior UN officials also cite the value of the UN’s comprehensive approach, including the threat or use of force by peacekeepers and high-level political engagement. They argue that these protection practices, which are largely unavailable to other actors and which bottom-up practices may compromise, are another reason to think twice about continuing to support CSP.Footnote 47

The other three organizations are, by contrast, focused on preventing negative unintended consequences; they remain committed to supporting CSP as long as there is a collective acceptance of the risks involved and deliberative practices of reflection. A senior Oxfam staff member stated: “We are always aware of the risks, these are always present. … The idea is you can take more risks if you manage risk well. … We are continually asking ourselves whether we are being savvy enough to really understand the consequences.”Footnote 48 In a similar vein, a former NP official noted: “We must always measure impact vs. risk. … Staff have to come to terms with the fact that they often have to make the least bad decision.”Footnote 49 This engagement in self-reflection is a reminder that—as Merton (Reference Merton1936) originally noted—not all unintended consequences are necessarily unanticipated: policy makers can take steps to improve their ability to foresee the effects of their actions (see also de Zwart Reference de Zwart2015). Some of the organizations studied here have accepted that international support for CSP is a risky business and are developing strategies to manage the risks.

In line with what some prior work on unintended consequences suggests, these organizations are, to varying degrees, aiming to enhance their epistemic capacities by better understanding local actors and the conflict context, compensate for a propensity to engage in short-term thinking, and more carefully select their local partners (see Salehyan Reference Salehyan2010; Salehyan, Siroky, and Wood Reference Salehyan, Siroky and Wood2014). CIVIC, for example, first finds local “champions” to help identify and assess prospective members of its Community Protection Groups. This vetting process involves interviewing elders, neighbors, and colleagues; it aims to ensure that those joining Community Protection Groups are perceived as impartial and legitimate community representatives, prioritize protection objectives, and do not pursue private agendas or reinforce power asymmetries.Footnote 50 CIVIC and Oxfam have developed staff guidelines on how to manage the challenges associated with CSP, and have fostered an internal culture of reflection that incorporates continual evaluation, monitoring, and contingency planning. These forms of risk management help to counteract the dangers of “short-termism” and facilitate discussion of the long-term or adjacent effects of programming. Oxfam staff noted that the organization’s reflective approach to supporting CSP “encourages constructive criticism, leading to … adaptive course corrections” (Green Reference Green2015, 11). Nonetheless, interviewees from all four organizations identified risk management as an area for improvement and noted that variation in levels of staff experience and training has translated into “different degrees of awareness of potential risks.”Footnote 51

To directly confront the potential for CSP support to entrench local hierarchies or forms of exclusion, two of the organizations we studied—Oxfam and NP—have changed how they tailor local protection committees to each conflict context. This sometimes requires adopting markedly different approaches in different countries. In Syria, for example, Oxfam learned that creating protection committees was inappropriate because formal structures could be seen as a form of surveillance by state authorities, thereby putting civilians in increased danger.Footnote 52 In other countries, like the DRC and CAR, it opted to create new structures to avoid the discriminatory power dynamics inherent in existing community organizations.Footnote 53 Following its principle of “the primacy of local actors,” NP’s approach also ensures that each protection structure is the result of an in-depth assessment of community needs. NP’s guiding philosophy makes it generally reluctant to question or judge a community’s protection practices, even if they run counter to how staff understand the organization’s values. Oxfam, by contrast, addresses the potential risk that local communities might engage in protection activities that the organization views as harmful by working closely with local actors to raise awareness of such practices, identify alternative ways to meet protection needs, and find local “allies” to deter such practices. In this way, Oxfam has begun to directly involve local communities in addressing the risk of unintended consequences and the deeper dilemma inherent in international support for CSP.

Conclusion

International support for CSP has become a desirable alternative to high-cost and high-risk direct protection through military, diplomatic, and humanitarian means. Yet our analysis demonstrates that it is not a panacea. As a form of mediated social action occurring in contexts of diffuse agency, international support for CSP interacts with local dynamics and sociocultural practices and is thus an inherently risky business. The growing body of scholarship on bottom-up or “localized” approaches to international engagement and wartime civilian agency has thus far overlooked or downplayed these risks. Our research reveals that this is a problematic omission and begins to fill that gap.