1. Introduction

This article is a contribution to our understanding of the cross-linguistic properties of register-affecting phenomena such as downstep and upstep, looking specifically at the rare and intriguing characteristics of downstep in Drubea and Numèè, two Oceanic languages of New Caledonia.

Downstep is a well-attested prosodic phenomenon affecting register – that is, the pitch range within which tonal contrasts are to be realised, defined by a ‘floor’ (lowest pitch within the range) and a ‘ceiling’ (highest pitch within the range). Specifically, downstep is a contrastive pitch drop that sets a new, lower register ceiling for the remainder of its domain, most of the time the utterance.Footnote

1

In most documented cases, downstep is caused by a low (L) tone and targets a following high (H) tone. It is customary to distinguish between ‘automatic’ downstep, caused by an overt L tone, for example, ![]() =

= ![]() =

= ![]() , and ‘non-automatic’ downstep when the L tone trigger is not heard, for example, when it is deleted or set afloat, as in

, and ‘non-automatic’ downstep when the L tone trigger is not heard, for example, when it is deleted or set afloat, as in ![]() =

= ![]() =

= ![]() (Stewart Reference Stewart1965). One of the main characteristics of languages with non-automatic downstep is the ‘terracing effect’ (Winston Reference Winston1960; Connell Reference Connell, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Rice and Hume2011) created by multiple successive downsteps in an utterance, with each downstep bringing the pitch range (or register ceiling) down by one notch, for example, /HLHHHLHHH/ = [HꜜHHHꜜHHH] = [˥ ˦ ˦ ˦ ˧ ˧ ˧]. Since automatic downstep is not at issue here, I will use ‘downstep’ to refer to the non-automatic kind only.

(Stewart Reference Stewart1965). One of the main characteristics of languages with non-automatic downstep is the ‘terracing effect’ (Winston Reference Winston1960; Connell Reference Connell, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Rice and Hume2011) created by multiple successive downsteps in an utterance, with each downstep bringing the pitch range (or register ceiling) down by one notch, for example, /HLHHHLHHH/ = [HꜜHHHꜜHHH] = [˥ ˦ ˦ ˦ ˧ ˧ ˧]. Since automatic downstep is not at issue here, I will use ‘downstep’ to refer to the non-automatic kind only.

Downstep has been found to be triggered mostly by L tones, and to affect mostly H tones. Downstepped ![]() and

and ![]() tones are indeed very rare: I know of only 15 cases of the former in the literature,Footnote

2

and only eight languages are described as having a downstepped

tones are indeed very rare: I know of only 15 cases of the former in the literature,Footnote

2

and only eight languages are described as having a downstepped ![]() tone to my knowledge.Footnote

3

Cases of downstep not caused by L tones are rare, but attested. The downstepped L tone in Bamileke Dschang, for instance, has been analysed as being caused by a floating H (Hyman Reference Hyman1985b; Snider Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020). Cases where downstep is not caused by a floating tone are also attested, such as dissimilatory downstep between two H tones (

tone to my knowledge.Footnote

3

Cases of downstep not caused by L tones are rare, but attested. The downstepped L tone in Bamileke Dschang, for instance, has been analysed as being caused by a floating H (Hyman Reference Hyman1985b; Snider Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020). Cases where downstep is not caused by a floating tone are also attested, such as dissimilatory downstep between two H tones (![]() =

= ![]() ) in Shambala (Odden Reference Odden1982) or Supyire (Carlson Reference Carlson1983). However, cases of downstep not triggered by a L tone or affecting other tones than H are still considered exceptional, and are consequently still understudied (cf. Leben Reference Leben2018).

) in Shambala (Odden Reference Odden1982) or Supyire (Carlson Reference Carlson1983). However, cases of downstep not triggered by a L tone or affecting other tones than H are still considered exceptional, and are consequently still understudied (cf. Leben Reference Leben2018).

One additional point of interest is that downstep has until now been analysed only as a derived phenomenon emerging from tonal interaction, either in postlexical phonology or in phonetic implementation (see Connell Reference Connell, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Rice and Hume2011 for an overview). Until very recently, it had never been proposed that downstep could also be an underlying phonological primitive. I have shown elsewhere that in Paicî, another Oceanic language of New Caledonia, downstep is best viewed as a phonological object of its own, present in underlying representations (Lionnet Reference Lionnet2022b). A similar claim has been made by Rochant (Reference Rochant2023) about Baga Pukur, an Atlantic language of Guinea. In both cases, downstep is underlying in a system that also has underlying tones; for example, the three underlying prosodic primitives of Paicî are the two tones H and L and a downstep register feature. Underlying downstep is thus another attested, but non-canonical form of downstep.

The present article aims to contribute to a better understanding of non-canonical forms of downstep by offering a description and analysis of Drubea and Numèè, two very closely related Oceanic languages of New Caledonia whose word-prosodic system is typologically unique. Indeed, I show that the ‘tonal’ system of Drubea and Numèè, first expertly described by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973), can be analysed as consisting only of register features – specifically an underlying downstep and a postlexical epenthetic upstep – and no tone at all. The main underlying word-prosodic contrast is between downstepped register-bearing units (RBUs, defined as the mora, although the syllable also plays a role; see §4.2) and registerless RBUs, that is, a contrast between /ꜜ/ and

![]() $\varnothing $

. Upstep is optionally inserted on registerless RBUs immediately before a downstep in order to increase the downward contrast marked by the downstep, which gives rise to alternations of higher and lower pitch heights and thus to the illusion of a tonal H–L contrast.

$\varnothing $

. Upstep is optionally inserted on registerless RBUs immediately before a downstep in order to increase the downward contrast marked by the downstep, which gives rise to alternations of higher and lower pitch heights and thus to the illusion of a tonal H–L contrast.

This system is particularly interesting from a cross-linguistic and typological perspective, as it is the only word-prosodic system known to date that rests entirely on register features, without any need for tones. This enriches our understanding of word-prosodic typology, in particular, the range and variety of ‘non-canonical’ tone systems in Hyman’s (Reference Hyman2006) word-prosodic typology. This also calls into question the definition of ‘tone’ and what is required for a language to be considered ‘tonal’. Specifically, two types of tone systems must be recognised: in addition to the well-known tone-based systems, in which tonal contrasts are defined paradigmatically (e.g., H is realised with higher pitch than L in the same context), register-based systems like that of Drubea and Numèè must also be recognised, in which tonal contrasts are defined syntagmatically (e.g., a downstepped unit is realised with lower pitch than the preceding unit). From a theoretical perspective, this register-only system is highly relevant for debates regarding the representation of tone and register, in particular, the existence of dedicated register features, proposed by Snider (Reference Snider1990, Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020), and the relation between register and tone.

I address all these questions in the article. I first give in §2 some relevant background information about Drubea and Numèè and the data that serve as the empirical basis of the main claim of the article. I then describe the word-prosodic system of the two languages in §3, and propose a register-based analysis in §4, couched in a modified version of Snider’s (Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020) Register Tier Theory. This analysis is then shown to be superior to a purely tonal alternative in §5. The typological and theoretical implications of the recognition of register-based tonal languages such as Drubea and Numèè are then discussed in §6.

2. The data

2.1. Drubea and Numèè

Drubea [ɳaa ꜜɳɖumbea] (Glottocode: dumb1241) and Numèè [ɳaa ꜜɳumɛɛ] (nucl1484) are the two southernmost languages of Grande Terre, New Caledonia’s main island.Footnote 4 Together with Kwényï, spoken on the Isle of Pines, about 50 km southeast of Grande Terre, they constitute the Far South subgroup (Haudricourt Reference Haudricourt and Bowen1971) within the New Caledonian linkage of Southern Oceanic (Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Ross, Crowley, Lynch, Ross and Crowley2002), and count among the five tonal languages of New Caledonia, with Paicî and Cèmuhî, spoken in the central/northern region of Grande Terre.

Numèè and Kwényï are sometimes described as dialects of one language. I have excluded Kwényï from the present article because it differs markedly with respect to its prosodic system (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 154).Footnote 5 Drubea and Numèè, on the other hand, share the same tone system (with only minor differences), which is the focus of this article.

Drubea is spoken by approximately 1,000 people.Footnote 6 There are three dialectal variants: [ɳaa vũũnya] in Unya, on the east coast, as well as two dialects in Paita on the west coast – [ɳaa pwɛco] (lit. ‘language of the coast people’) on the coast, and [ɳaa ŋgakure] (lit. ‘language of the mountain people’) in the mountains.

Numèè is spoken by less than 1,000 speakers in three villages in the Far South of Grande Terre: Waho, Touaourou and Goro.Footnote 7 Dialectal variation in Numèè is minimal (Académie des Langues Kanak 2015; Wacalie Reference Wacalie2013).Footnote 8

2.2. Previous work and data sources

Significant work on the Far South languages started with Rivierre’s (Reference Rivierre1973) description of the phonological systems of the Unya dialect of Drubea (/ɳaa vũũnya/), the variety of Numèè spoken in Goro (/ɳaa xeɽe/), and Kwényï.Footnote 9

Additional work on Drubea includes Shintani and Païta’s grammar (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b) and dictionary (Reference Shintani and Païta1990a), based mostly on the mountain dialect of Paita, as well as a phonetic description of aspects of the consonant and vowel systems by Gordon & Maddieson (Reference Gordon and Maddieson1999). Shintani also collected texts which he published in two separate volumes: Genet et al. (Reference Genet, Païta, Caroline, Wamytan, Betto and Tadahiko1992) and Shintani (Reference Shintani2019). The latter is meant to serve as a language textbook, and was adapted to an online language tutorial in 2023 by the Académie des Langues Kanak (ALK), together with sound files of the original recordings (Académie des Langues Kanak 2023).Footnote 10

Additional work on Numèè includes a morphosyntactic description by Wacalie (Reference Wacalie2013), an unpublished lexicon by Rivierre & Vandégou (Reference Rivierre and Vandégoun.d.), as well as an M.A. thesis by Rendina (Reference Rendina2009), which I have not been able to consult. Texts recorded by A.-G. Haudricourt and J.-C. Rivierre in the 1960s are available in the online Pangloss collection, where they are transcribed, glossed and translated into French (Haudricourt & Rivierre, Reference Haudricourt and Rivierren.d.).

Table 1 Adaptation of Rivierre’s (Reference Rivierre1973) scale for pitch notation.

I have not collected any data on either Drubea or Numèè. The present article is thus entirely based on secondary data – mainly Rivierre’s (Reference Rivierre1973) phonological description and analysis of both languages; the Drubea grammar and Drubea-French dictionary published by Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b,Reference Shintani and Païtaa); texts collected by Shintani and published in Shintani (Reference Shintani2019) and Académie des Langues Kanak (2023); and Reference Haudricourt and RivierreHaudricourt & Rivierre’s (Reference Haudricourt and Rivierren.d.) recordings of Numèè texts. For Shintani’s Drubea recordings and transcriptions, two citations are given: Shintani’s (Reference Shintani2019) book, and the corresponding lesson number in the book and the online tutorial (Académie des Langues Kanak 2023), marked with an L. For example, ‘Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 254, L35’ refers to lesson 35, the text of which is found on page 254 of Shintani (Reference Shintani2019), and the recording under the link labelled ‘Leçon 35’ in the online tutorial.Footnote 11 Speakers in Shintani’s recordings were all women in their sixties and seventies at the time of recording in the 1990s: Augustine ‘Titine’ Betto (née Païta), Philomène ‘Philo’ Poarareu and Françoise Gaïa (née Païta).

Rivierre’s (Reference Rivierre1973) description is not accompanied by recordings (if the recordings exist, they are not available in any known online or physical repository) which would allow one to check Rivierre’s phonetic transcription of pitch heights. The analysis I present in this article thus partly rests on Rivierre’s transcriptions. Rivierre is said by linguists who knew him to have had an excellent ear, which I was able to verify myself when working on Paicî, another New Caledonian language whose tone system he described and analysed (in Rivierre Reference Rivierre1974). My findings concur with his almost perfectly, which gives me full confidence in his transcriptions. I was also able to find confirming evidence in Shintani’s Drubea recordings and Rivierre’s own recorded Numèè texts, both mentioned above.

Glosses for grammatical words follow Shintani & Païta’s (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b) grammatical analysis and terminology, including in examples borrowed from Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973), whose glosses of function words lacks precision. Translations to English are my own.

Throughout the article, detailed information on the phonetic realisation of pitch contrasts of each example is systematically provided. This comprises the original narrow transcription of pitch heights for examples found in Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973) and Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b), and actual pitch tracings for examples taken from recorded texts (Shintani Reference Shintani2019; Académie des Langues Kanak 2018; Haudricourt & Rivierre, Reference Haudricourt and Rivierren.d.), for which only a broad, phonological transcription is given in the original source. All transcriptions drawn from original sources are converted to standard IPA notation (modulo a few simplifications; see §2.3). This includes the notation of pitch realisations: I have converted Shintani & Païta’s schematic notation and Rivierre’s numerical notation to the more standard numerical system, using 1 to represent the lowest pitch and 5 the highest. To be faithful to the original transcriptions, I retain Rivierre’s use of half steps (e.g., 1.5, 3.5), although these are not standard IPA. The correspondences between Rivierre’s original transcription and my retranscription are given in Table 1.

2.3. Phonological sketch

Drubea and Numèè (as well as Kwenyï) have virtually the same consonant inventory, presented in (1), where the phonological transcription used in this article (in both underlying and surface transcriptions) is accompanied by a phonetic transcription. The only difference is that Drubea systematically has ![]() where Numèè has

where Numèè has ![]() . The plosive series is structured along a two-way contrast between voiceless and prenasalised voiced plosives, as in all the languages of Grande Terre. To simplify the transcriptions, prenasalised plosives will be systematically transcribed as plain voiced plosives in this article (e.g.,

. The plosive series is structured along a two-way contrast between voiceless and prenasalised voiced plosives, as in all the languages of Grande Terre. To simplify the transcriptions, prenasalised plosives will be systematically transcribed as plain voiced plosives in this article (e.g., ![]() =

= ![]() ), as is usual in New Caledonian linguistics.

), as is usual in New Caledonian linguistics.

The vowel inventories of the two languages are also very close, the only difference being the presence in Numèè of the three long front rounded vowels /üü øø ø̃ø̃/, absent from Drubea, as shown in (2).

Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973) only gives a partial account of syllable and word structure in Drubea and Numèè. He shows that coda consonants are not allowed: only open syllables are attested, with or without an onset consonant. Vowel length is said to be contrastive. Permissible syllable structures can thus be summarised by the formula (C)V(V), with VV representing a long vowel. According to Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973), sequences of unlike vowels are heterosyllabic, never diphthongs, and there are no heterosyllabic sequences of identical vowels – that is, ![]()

![]() ‘axe’ is disyllabic (not

‘axe’ is disyllabic (not ![]() ), whereas

), whereas ![]()

![]() ‘husband’ is monosyllabic (and

‘husband’ is monosyllabic (and ![]() is not attested). Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 1) propose the same analysis for Drubea. I will follow this analysis here.

is not attested). Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 1) propose the same analysis for Drubea. I will follow this analysis here.

Most monomorphemic stems are mono- or disyllabic, as illustrated in (3), where σ and σː stand for (C)V and (C)VV, respectively.Footnote 12

Stems of more than two syllables are also attested, although many appear to be morphologically complex – in particular, compounding (both in nouns and in verbs) is frequent. For lack of time and data, Rivierre does not provide a full analysis on the internal structure of words of more than two syllables. He mostly ignores these words in his analysis of the tone system, which I will also do, for the same reasons (cf. §3.8).

3. The word-prosodic system of Drubea and Numèè

As shown by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 124–153), the word-prosodic systems of Drubea and Numèè are virtually identical. The only significant difference lies in utterance-final prosodic phenomena, discussed in §3.4. Rivierre describes the two systems as one, illustrating his generalisations and analyses with examples taken from both. I do the same here, although I give more Drubea than Numèè examples, mainly because of the relative abundance of available Drubea data. The source language is always explicitly given in all examples.

In this section, I give a description of the surface prosodic patterns attested in both languages, using analytical categories (in particular, ‘downstep’ and ‘upstep’) that are fully developed in the analysis I propose in §4. I first describe the tonal behaviour of monosyllabic stems (henceforth, ‘monosyllables’; §§3.1–3.5), then that of disyllables (§3.6), before discussing the special case of CVꜜV syllables (§3.7). The issue of stems of more than two syllables is briefly addressed in §3.8, and morphophonological tonal effects in §3.9.

3.1. Downstepped vs. registerless monosyllabic stems

Monosyllables mostly fall into two prosodic types in Drubea and Numèè: those that are systematically realised lower than the preceding morpheme, and those that are not.Footnote 13 The latter tend to be realised at the same pitch as the preceding morpheme, all else being equal, but are also very frequently realised with higher pitch, as we will see in §3.2. I will, for now, call these two types same-pitch and lower-pitch syllables, respectively, and will transcribe the latter with a preceding downstep mark, a transcription which reflects the analysis I propose in §4. Note that I use the term ‘syllable’ in this section for ease of exposition. I will show in §§3.7 and 4.2 that the tone- (or rather register-) bearing unit is actually the mora (although the syllable also has a role to play).

Numerous minimal pairs are attested in both languages, as illustrated with Drubea examples in (4) (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 123–124; Shintani & Païta Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 17).

The contrast between same-pitch /be/ ‘die’ and lower-pitch /ꜜbe/ ‘niaouli tree’ is illustrated in (5) and (6) (the morpheme under consideration is underlined in the examples). As can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, /be/ ‘die’ is realised at the same pitch as the preceding syllable, while /ꜜbe/ ‘niaouli tree’ is realised at a lower pitch.Footnote 14

Figure 1 /… ꜜmwa be to ꜜɳe co + ꜛ%/ ‘[his son] died in the water’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 178, L24).

Figure 2 /dɪɪ ꜜbe/ ‘small niaouli’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 353, L49).

This same-pitch vs. lower-pitch realisation is seen irrespective of the prosodic type of the preceding syllable. Examples (7) and (8) illustrate the descriptive marker ![]() following the same-pitch noun

following the same-pitch noun ![]() ‘person’ in (7), and following the lower-pitch perfective marker

‘person’ in (7), and following the lower-pitch perfective marker ![]() in (8).Footnote

15

Figures 3 and 4 show that

in (8).Footnote

15

Figures 3 and 4 show that ![]() is realised at the same pitch as the immediately preceding syllable in both cases, irrespective of whether it is a same-pitch or lower-pitch syllable. Note that the speaker repeats the marker

is realised at the same pitch as the immediately preceding syllable in both cases, irrespective of whether it is a same-pitch or lower-pitch syllable. Note that the speaker repeats the marker ![]() in (7), and both instances are realised at the same pitch as the last two syllables of the noun

in (7), and both instances are realised at the same pitch as the last two syllables of the noun ![]() . The pitch rise seen in

. The pitch rise seen in ![]() need not concern us here, and will be dealt with in §3.2. The important point is that there is no pitch drop in the transition from the last syllable of

need not concern us here, and will be dealt with in §3.2. The important point is that there is no pitch drop in the transition from the last syllable of ![]() to the following same-pitch syllable

to the following same-pitch syllable ![]() .Footnote

16

.Footnote

16

Figure 3 /ꜜtaa aboɽu te || te wɪɪ-ɽe ɲi/ ‘someone is squeezing coconut pulp’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 172, L23).

Figure 4 /ko ꜜmwa te … / ‘I [work my field]’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 234, L32).

Examples (9) and (10) illustrate the lower-pitch word ![]() ‘fire(wood)’ after same-pitch

‘fire(wood)’ after same-pitch ![]() ‘smoke’ (9) and lower-pitch

‘smoke’ (9) and lower-pitch ![]() ‘take’ (10). As can be seen in Figures 5 and 6,

‘take’ (10). As can be seen in Figures 5 and 6, ![]() is realised lower than the preceding syllable in both cases.Footnote

17

is realised lower than the preceding syllable in both cases.Footnote

17

Figure 5 /kaa ꜜʈã/ ‘(fire) smoke’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 173, L23).

Figure 6 /kãꜜã ꜜvi ꜜʈã/ ‘[then we] take firewood’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 172, L23).

A sequence of same-pitch syllables is realised, unsurprisingly, with the same pitch throughout, as in the sequence […boɽu te || te wɪɪ-ɽe ɲi] in (7) and Figure 3. A sequence of lower-pitch syllables, on the other hand, is realised as a series of pitch drops (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 145; Shintani & Païta 1990b: 19). This is already illustrated in (10) and Figure 6. Two additional examples are given in (11) and (12).Footnote 18

Example (12) shows a succession of four lower-pitch syllables: /… ꜜmwa ꜜɳii ꜜyoo ꜜɳe…/, followed by the same-pitch word /xee/, itself followed by two lower-pitch syllables /… ꜜyɛ ꜜme/.

Figure 7 shows that the first four consecutive lower-pitch syllables [ꜜmwa ꜜɳii ꜜyoo ꜜɳe] in example (12) are realised with four consecutive drops in pitch. The successive pitch drops do not all have the same magnitude: the first drop [ko ꜜmwa] is sharp, while the following ones are less and less perceptible, because the intervals are successively smaller as the speaker reaches the lower end of her pitch range. The slight pitch rise seen on ![]() will be explained in §3.2.

will be explained in §3.2.

Figure 7 /ko ꜜmwa ꜜɳii ꜜyoo ꜜne-xee-ꜜyɛ ꜜme…/ ‘I said just now that…’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 306, L43 AT).

The behaviour of these two types of syllables suggests a contrast in register rather than in tone height: the lower-pitch syllables are realised in a lower register than the immediately preceding one.Footnote 19 This lower register is maintained for the remainder of the utterance, unless another lower-pitch syllable imposes a new register lowering. Furthermore, lower-pitch syllables are not associated with any particular pitch range: they are often realised toward the higher end of a speaker’s pitch range at the beginning of an utterance, especially utterances including many lower-pitch syllables, that is, many pitch drops. Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 153), who analyses lower-pitch syllables as low-toned and same-pitch ones as high-toned, as we will see in §5, says this explicitly: ‘[t]his contrastive nature [i.e., syntagmatic register contrast with the preceding syllable] of the low tone [= lower-pitch syllable] is more essential to its definition than its pitch height’. In other words, lower-pitch syllables behave like downstepped syllables. Same-pitched syllables, on the other hand, are inert from the point of view of register: they do not impose any register change, and their realisation is subject to contextual variation, as we will see in the next section. This suggests that they carry no underlying indication of pitch realisation. ‘Lower-pitch’ syllables will henceforth be referred to as ‘downstepped’, and ‘same-pitch’ ones as ‘registerless’, in accordance with the phonological transcription used so far, and the analysis fully developed in §4.

With only registerless and downstepped syllables, one should expect the pitch of an utterance to only ever go down – abstracting away from possible effects of intonation. This is mostly the case – and is, indeed, one salient characteristic of both Drubea and Numèè, which makes them noticeably different from the very closely related Kwényï (which, as noted by Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 154, is characterised by an overall rising melody profile). One major exception to this principle is the raising frequently undergone by registerless syllables in two contexts: before a downstepped syllable, and utterance-finally (in Drubea), as discussed in the following two sections.

3.2. Pre-downstep raising of registerless syllables

As noted by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 132), before a downstepped syllable, speakers oscillate between two realisations of what I analyse as registerless syllables: either at the same pitch as the preceding syllable, as with the descriptive marker /te/ in (13a), or higher than the preceding syllable as in (13b), the latter being more frequent according to Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973), which is confirmed by Shintani’s recorded texts.

This pre-downstep raising seen in (13b), which I transcribe and analyse as upstep (see §4.4), very frequently affects registerless syllables. As clearly described by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 153), this raising ‘reinforces and highlights the contrast marked by each low tone [= downstep] with the preceding syllable. […] A high-toned [= registerless] syllable is itself best defined as a syllable that does not mark a contrast of this type than as a high-pitched syllable’ (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 153). Note that pre-downstep raising rarely affects downstepped syllables, and when it does, it is realised differently, as we will see below (see example (18) and the adjacent text). This is one of the key differences between the two types of syllables.

Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 133) further notes that ‘the raised realisation of the H tone [= registerless syllable] before a L tone [= downstep] is common but not obligatory; understandably, it is largely used in ![]() [= registerless–downstepped–registerless–downstepped] sequences’ (emphasis in the original). Without this raising of registerless syllables, ‘each new L tone [= downstep] brings the speaker down toward lower and lower registers, making the register drop characteristic of the downstep more and more difficult to produce and perceive. The [raising of] H tones [=registerless syllables] is thus used in this context to maintain the register of the utterance within a range conducive to an economic and perceptible realisation of L tones [=downsteps]’ (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 133). Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 134) finally notes that ‘the raising of H-toned [= registerless] syllables rarely compensates for the lowering of the register caused by the preceding L tone [= downstep], which explains the overall descending trend in a downstepped–registerless–downstepped… sequence’. This is illustrated in (14) and (15). As seen in Figure 8, the successive valleys and peaks marked by the sequence of downsteps and upsteps in (15) are characterised by lower and lower pitch, and the overall pitch trajectory throughout the utterance follows a downward course.

[= registerless–downstepped–registerless–downstepped] sequences’ (emphasis in the original). Without this raising of registerless syllables, ‘each new L tone [= downstep] brings the speaker down toward lower and lower registers, making the register drop characteristic of the downstep more and more difficult to produce and perceive. The [raising of] H tones [=registerless syllables] is thus used in this context to maintain the register of the utterance within a range conducive to an economic and perceptible realisation of L tones [=downsteps]’ (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 133). Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 134) finally notes that ‘the raising of H-toned [= registerless] syllables rarely compensates for the lowering of the register caused by the preceding L tone [= downstep], which explains the overall descending trend in a downstepped–registerless–downstepped… sequence’. This is illustrated in (14) and (15). As seen in Figure 8, the successive valleys and peaks marked by the sequence of downsteps and upsteps in (15) are characterised by lower and lower pitch, and the overall pitch trajectory throughout the utterance follows a downward course.

Figure 8 /ꜜɳe-ꜜbʊʊ-V ꜜya yaa ꜜme a-ꜜʈe/ ‘Your face does not look good’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 130, L17).

Pre-downstep raising is not always limited to the syllable that immediately precedes the downstep; it sometimes extends through a sequence of registerless syllables. This pitch raising scoping over several successive registerless syllables may be abrupt, as in (16) and Figure 9, where one can see that the raising effect caused by the downstep on the second mora of the determiner ![]() does not affect only the preceding registerless mora, but extends to the entire sequence of preceding registerless syllables, with the same raised pitch throughout.Footnote

20

does not affect only the preceding registerless mora, but extends to the entire sequence of preceding registerless syllables, with the same raised pitch throughout.Footnote

20

Figure 9 /ꜜʈã ꜜmwa ŋe-ɽe maꜜa…/ ‘The fire burns these [stones]’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 172, L23).

Alternatively, the raising effect may be gradual, in which case, the pitch starts rising on the first registerless syllable of the affected sequence, and reaches its peak on the registerless syllable immediately before the downstep. This is illustrated in (17) and Figure 10, where the rise starts on the registerless syllable [pwe] immediately after the downstepped syllable [ꜜɳo], and rises gradually until it reaches its peak on the assertive marker [pa], immediately before the downstepped syllable [ꜜtũã] ‘see’. This gradual rise can be seen as a form of interpolation, that is, a gradual transition from the lower pitch of a downstepped syllable to the higher pitch of the next raised pre-downstep syllable. I transcribe this interpolation phenomenon with a northeast-pointing arrow [].

Figure 10 /ꜜɳopwe ki pa ꜜtũã-ɽe…/ ‘And you see [that it is good]…’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 41, L04).

Finally, as mentioned above, pre-downstep raising is also sometimes seen to affect downstepped syllables. In such cases, the downstep is never undone by the raising effect. Instead, the rise in pitch is heard on the end of the syllable, after the register lowering triggered by the downstep, in what can be described as a rising contour. This is attested even on monomoraic CV syllables, as seen in (18). ([] represents a monomoraic vowel affected by upstep on its second half.)

The realisation of registerless syllables is also sensitive to utterance-final phenomena, as seen in the next two sections: final raising in Drubea (§3.3), and final downstepping of light syllables in Numèè (§3.4).

3.3. Utterance-final raising in Drubea

A tendency toward raising of registerless syllables is also seen in utterance-final position in Drubea (Numèè differs from Drubea on this point, as discussed in the next section). This is particularly marked when the final syllables are preceded by one or more pitch drops caused by downstepped syllables. This effect is not explicitly described by either Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973) or Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b), but it can be seen in some of their transcriptions. Optional final raising is illustrated with the two examples below, from Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973). In both cases, the utterance ends with a sequence of two registerless syllables. In (19), there is no final raising, while in (20), the final registerless syllable is realised at a higher pitch than the immediately preceding one. I transcribe this final pitch rise with an upstep symbol followed by a percent sign (ꜛ%) at the end of the utterance in phonological transcription, and immediately before the final syllable in surface transcription. This transcription corresponds to the analysis of this rise as a final boundary upstep, which I propose in §4.8.

In the Unya dialect described by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973), this effect seems to be rare – at least the reader is led to infer so, as utterance-final registerless syllables are realised with the same pitch as the preceding syllable in all but two examples, of which (20) is one. Final raising is much more frequent in the Païta dialect. This is not explicitly said in Shintani & Païta’s (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 17–22) description, but it can be seen in the few phonetic transcriptions they give. A cursory survey of the 50 texts recorded by Shintani and available in the online Drubea tutorial (Académie des Langues Kanak 2023) suggests that the vast majority of utterance-final registerless syllables undergo this final raising in the Païta dialect. The example in (21) is taken from one of these texts. As can be seen in Figure 11, the final two syllables [pwɛ wẽ] are clearly realised with a higher pitch than the preceding registerless prefix a-, which is pronounced at the same lowered pitch as the downstepped final syllable of the verb [uꜜi] immediately before it (see also (7)).Footnote 21

Figure 11 /keꜜe kãꜜã uꜜi-a -wɛ wẽ + ꜛ%/ ‘We will do everything that way’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 172, L23).

3.4. Utterance-final downstepping in Numèè

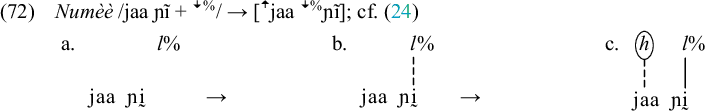

In Numèè – at least in the Goro dialect described by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973) – utterance-final light CV syllables are systematically downstepped if they are preceded by a registerless syllable; that is, ![]() (where σ stands for a registerless syllable). That this is indeed downstep is revealed by the fact that the preceding registerless syllable often undergoes pre-downstep raising, as is the case in (22) and in (23) and Figure 12, where the downstepping of final

(where σ stands for a registerless syllable). That this is indeed downstep is revealed by the fact that the preceding registerless syllable often undergoes pre-downstep raising, as is the case in (22) and in (23) and Figure 12, where the downstepping of final ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜜɳa] and

$\to $

[ꜜɳa] and ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜜwẽ] triggers raising of the preceding

$\to $

[ꜜwẽ] triggers raising of the preceding ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜛa] and

$\to $

[ꜛa] and ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜛgɪɪ], respectively. I analyse this final downstepping process as the realisation of a final boundary downstep, transcribed

$\to $

[ꜛgɪɪ], respectively. I analyse this final downstepping process as the realisation of a final boundary downstep, transcribed ![]() (cf. §4.8).Footnote

22

(cf. §4.8).Footnote

22

Figure 12 /… yaꜜa geꜜe ꜜmẽ ꜜʈõŋẽɽẽ xɪɪ-ꜜa ɲĩ püɽüco gɪɪ wẽ/ ‘[this child], we don’t know where he’s coming from!’ (Numèè; Ati & Rivierre Reference Ati and Rivierre1966: S54, 4:03).

Additional evidence in favour of viewing final downstepping as the assignment of a boundary downstep is that it affects underlyingly downstepped syllables as well, as shown by the fact that the contrast between the two types of syllables is maintained in utterance-final position. An utterance-final registerless light syllable is indeed not realised as low as a downstepped syllable in the same position, as noted by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 127) and illustrated in (24) and (25). This shows that downstepping is the realisation of an inserted extra downstep, not just the result of a change of the final syllable from registerless to downstepped. When realised on an already downstepped syllable, the boundary downstep results in a double downstep, which explains the lower realisation of underlying downstepped ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜜꜜɲĩ] in (25) compared to registerless

$\to $

[ꜜꜜɲĩ] in (25) compared to registerless ![]()

![]() $\to $

[ꜜɲĩ] in (24).

$\to $

[ꜜɲĩ] in (24).

Final downstepping affects only light syllables: CVV syllables remain registerless utterance-finally, as in (26) (cf. (22)) and in (27) and Figure 13.Footnote 23

Figure 13 /a-ꜜɽoo ꜜwɛcaaxɪɪ/ ‘… down near the channel’ (Numèè; Ati & Rivierre Reference Ati and Rivierre1966: S31, 1:58).

Finally, downstepping does not apply after a downstepped syllable, as shown in (28) and in (29) and Figure 14.

Figure 14 /… ɲĩ yʊʊ a-ꜜpaa kwẽ/ ‘… he berths on the sand’ (Numèè; Ati & Rivierre Reference Ati and Rivierre1966: S64, 4:57).

The latter examples suggest that the final boundary downstep ![]() is realised only on final light syllables following a registerless syllable, and left unrealised in all other contexts. From now on, the boundary downstep will be included in underlying form only when it is realised.

is realised only on final light syllables following a registerless syllable, and left unrealised in all other contexts. From now on, the boundary downstep will be included in underlying form only when it is realised.

3.5. Utterance-initial downstep

Downstep is not realised utterance-initially, where downstepped and registerless syllables are not phonetically distinct (unless they are followed by a downstepped syllable, as we will see below). This can be seen by comparing (30), which contains only registerless syllables, with (19), repeated here as (31), in which the initial syllable is downstepped. The two utterances start at the same pitch height. Non-realisation of the underlying downstep in (31) is indicated by parentheses.

This is easily explained if downstep is viewed as the realisation of an instruction to contrast downward with the immediately preceding syllable. In the absence of any preceding syllable, there is nothing to contrast with, and the utterance starts at what can be considered to be the pitch baseline. According to Rivierre and Shintani’s transcriptions as well as the selection of recordings from Shintani’s (Reference Shintani2019) text collection that I was able to process, the baseline in Drubea and Numèè can be schematically represented as mid-high, or 4 out of 5 on the pitch-height scale. This fairly high pitch level corresponds to the default pitch at the beginning of an unmarked utterance. The fact that the utterance starts by default at a rather high pitch is most likely meant to allow for a pitch decline in the course of the utterance, either because of the presence of following downstepped syllables (and the overall downward realisation of most utterances, noted by Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 153), or simply because of declination, a near-universal tendency for pitch to gradually lower over the course of an utterance. Declination is indeed attested in Drubea and Numèè, where an utterance containing only registerless syllables tends to ‘follow a straight-falling melodic line’ (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 131).

As shown by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 125), the contrast between utterance-initial downstepped and registerless syllables is maintained in the presence of a following downstepped syllable: in this context, an initial registerless syllable undergoes pre-downstep raising and is realised higher than the baseline, while an initial downstepped syllable does not, and is realised at the baseline. This is illustrated by the contrast between utterance-initial registerless ![]() in (32) and downstepped

in (32) and downstepped ![]() in (33).

in (33).

This partly explains why the default ceiling of the utterance-initial register is not at the highest point of the speaker’s range (i.e., level 5): it must remain possible to raise the default register when pre-downstep raising affects the utterance-initial syllable.

3.6. Disyllables

Disyllabic stems can be classified into three register classes (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 124, 126–127; Shintani & Païta Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 17–18).Footnote 24 These three classes are illustrated in (34) with a minimal triple.

Registerless disyllables (type 1) behave exactly like a succession of two registerless monosyllables: they are realised at the same pitch as the preceding syllable, as with ![]() ‘put’ in (35) and Figure 15; they may be affected by pre-downstep raising, as with

‘put’ in (35) and Figure 15; they may be affected by pre-downstep raising, as with ![]() ‘to go up’ and

‘to go up’ and ![]() ‘again’ in (36), or by either of the two utterance-final phenomena described in §§3.3 and 3.4: utterance-final raising in Drubea, for example,

‘again’ in (36), or by either of the two utterance-final phenomena described in §§3.3 and 3.4: utterance-final raising in Drubea, for example, ![]() ‘corrugated iron’ in (37) and Figure 16, and utterance-final dowstepping in Numèè, for example,

‘corrugated iron’ in (37) and Figure 16, and utterance-final dowstepping in Numèè, for example, ![]() ‘alive’ in (38), where downstepping of the final syllable causes pre-downstep raising of the initial.

‘alive’ in (38), where downstepping of the final syllable causes pre-downstep raising of the initial.

Figure 15 /…ꜜmwa veto ꜜtaa…/ ‘[I] put a [blanket on the table] (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 97, L12).

Figure 16 /ko te ꜜʈo-mwaɽi ꜜmwa… ꜜŋi kapwa + ꜛ%/ ‘I covered the house with corrugated iron' (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 147, L19).

The initial syllable of a type 2 disyllable behaves like a downstepped monosyllable: it is realised lower than the preceding syllable, irrespective of whether that syllable is downstepped or registerless. In example (39), the initial downstepped syllable of the verb ![]() ‘wake up’ is realised lower than the immediately preceding downstepped syllable

‘wake up’ is realised lower than the immediately preceding downstepped syllable ![]() , as seen in Figure 17. As with dowstepped monosyllables, the first syllable of type 2 disyllables frequently causes raising of the preceding registerless syllable(s), as illustrated in example (40), where the registerless descriptive marker

, as seen in Figure 17. As with dowstepped monosyllables, the first syllable of type 2 disyllables frequently causes raising of the preceding registerless syllable(s), as illustrated in example (40), where the registerless descriptive marker ![]() is clearly raised before the verb

is clearly raised before the verb ![]() ‘think’, as shown in Figure 18 (see also

‘think’, as shown in Figure 18 (see also ![]() ‘swim’ in (13b) and

‘swim’ in (13b) and ![]() ‘eat’ in (14)).

‘eat’ in (14)).

Figure 17 /ko ꜜmwa ꜜʈobe/ ‘I woke up’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 193, L26).

Figure 18 /ko te ꜜŋɛɽɛ-ɽe ꜜme…/ ‘I think that…’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 214, L29).

The second syllable of type 2 disyllables behaves like a registerless syllable. It is realised by default at the same pitch as the initial syllable, as in (40) and Figure 18. It is also subject to pre-downstep raising, as well as utterance-final raising in Drubea – although this is rarely the case for light syllables, and is seen mostly with long second syllables.Footnote

25

This is illustrated with the verb ![]() ‘plant’ in Drubea, affected by pre-downstep raising in (41) and Figure 19 and by utterance-final raising in (42) and Figure 20.Footnote

26

‘plant’ in Drubea, affected by pre-downstep raising in (41) and Figure 19 and by utterance-final raising in (42) and Figure 20.Footnote

26

Figure 19 /kãꜜã ꜜmwaɽii buꜜki/ ‘[I] planted flowers’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 147, L19).

Figure 20 /te ꜜmwaɽii-ɽe ku +ꜛ%/ ‘[I] plant yams’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 234, L32).

Finally, in type 3 disyllables, the second syllable is always realised at a lower pitch than the first one, just as a downstepped monosyllable would be. This is illustrated with the disyllable ![]() ‘to be sick, to die’ in (43) and (44). The pitch drop affecting the second syllable is clearly visible in Figures 21 and 22. As for the initial syllable, it behaves exactly like a registerless monosyllable: it either is realised at the same pitch as the preceding syllable, as in (43) and Figure 21, or undergoes pre-downstep raising, as in (44) and Figure 22.

‘to be sick, to die’ in (43) and (44). The pitch drop affecting the second syllable is clearly visible in Figures 21 and 22. As for the initial syllable, it behaves exactly like a registerless monosyllable: it either is realised at the same pitch as the preceding syllable, as in (43) and Figure 21, or undergoes pre-downstep raising, as in (44) and Figure 22.

Figure 21 /… kaꜜgwee te ki te veꜜyuu-ɽe/ ‘You look sick’ (lit. ‘it is like you are sick’; Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 130, L17).

Figure 22 /… ꜜmwa veꜜyuu wẽ teꜜe…/ ‘… [they] died because…’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 235, L32).

3.7. CVꜜV syllables

In addition to registerless CV(V) and downstepped ꜜCV(V) syllables, there is a third prosodic type which deserves attention: syllables with a long vocalic nucleus whose second mora is downstepped, that is, (C)VꜜV. The three-way contrast is firmly established in both languages, where minimal triplets are frequent. A few examples from Drubea are listed in (45).

The prosodic nature and behaviour of CVꜜV syllables is illustrated in (46) with the negative marker ![]() . As can be seen in Figure 23, the second mora is downstepped; that is, it is realised within a lower register than the preceding mora and imposes this lower register on the following registerless syllable. In most cases, the initial mora of

. As can be seen in Figure 23, the second mora is downstepped; that is, it is realised within a lower register than the preceding mora and imposes this lower register on the following registerless syllable. In most cases, the initial mora of ![]() syllables is realised with pre-downstep raising, which is seen in the realisation

syllables is realised with pre-downstep raising, which is seen in the realisation ![]() of the negative marker

of the negative marker ![]() in (46) and Figure 23, and more clearly in (47) and Figure 24.Footnote

27

However, this is not always the case, as shown in (48) and Figure 25, where the initial mora of

in (46) and Figure 23, and more clearly in (47) and Figure 24.Footnote

27

However, this is not always the case, as shown in (48) and Figure 25, where the initial mora of ![]() is clearly realised at the same pitch as the preceding subject pronoun

is clearly realised at the same pitch as the preceding subject pronoun ![]() .Footnote

28

.Footnote

28

Figure 23 /ɲi beꜜe ŋa-ɽe/ ‘[He said that] he doesn’t work’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 67, L8).

Figure 24 /ꜜɳi ꜜmwa beꜜe || …/ ‘They don’t [think about working]’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 306, L43).

Figure 25 /ꜜɳi beꜜe kwe-ɽe/ ‘They don’t eat [it]’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 187, L25).

The downstep affecting the second mora is frequently displaced and realised on the following syllable. If that syllable is underlyingly registerless, it is then realised with a downstep; that is, ![]()

![]()

![]() $\to $

$\to $

![]()

![]() . This is shown in (49) and Figure 26, and in (50), where the downsteps in the negative marker

. This is shown in (49) and Figure 26, and in (50), where the downsteps in the negative marker ![]() and the quantifier

and the quantifier ![]() are displaced and realised on the initial syllable of the following word. Note that pre-downstep raising also applies in

are displaced and realised on the initial syllable of the following word. Note that pre-downstep raising also applies in ![]() =

= ![]() and

and ![]() =

= ![]() .

.

Figure 26 /ko beꜜe jaaɳi-ɽe ꜜme tuꜜmwa …/ ‘I do not want other [people to come help me plant yams]’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 48, L05).

When the following syllable is underlyingly downstepped, downstep displacement creates a double downstep; that is, ![]()

![]() $\to $

$\to $

![]() , as illustrated by

, as illustrated by ![]()

![]() [bee ꜜꜜʈõkõ] in (51) and Figure 27, and by

[bee ꜜꜜʈõkõ] in (51) and Figure 27, and by ![]()

![]() [yaa ꜜꜜmḛ] and

[yaa ꜜꜜmḛ] and ![]()

![]() [gee ꜜꜜmḛ] in (52).

[gee ꜜꜜmḛ] in (52).

Figure 27 /ko beꜜe ꜜʈõkõ ꜜɳii-ɽe …/ ‘I cannot say…’ (Drubea; Shintani Reference Shintani2019: 67, L08).

That there is indeed a double downstep in such cases is confirmed by the fact that the contrast between registerless and downstepped syllables is maintained under downstep displacement, as illustrated by the near-minimal pair in (53): underlyingly downstepped ![]() ‘eat’ in (53b) is realised with a starker pitch drop under downstep displacement than registerless

‘eat’ in (53b) is realised with a starker pitch drop under downstep displacement than registerless ![]() ‘dance’ in (53a), which corresponds to the cumulative effect of its underlying downstep and the displaced downstep from preceding

‘dance’ in (53a), which corresponds to the cumulative effect of its underlying downstep and the displaced downstep from preceding ![]() .

.

CVꜜV syllables are attested in both monosyllables and disyllables. The latter are exclusively recent loanwords from French and English, in which the downstep is always in the initial syllable; that is, they all have the shape ![]() . A few Drubea examples are given in (54).

. A few Drubea examples are given in (54).

As seen above, ![]() sequences behave differently from

sequences behave differently from ![]() disyllables, with which there is no downstep displacement. It is not entirely clear whether

disyllables, with which there is no downstep displacement. It is not entirely clear whether ![]() disyllabic words (with two different vowels) behave similarly to or differently from

disyllabic words (with two different vowels) behave similarly to or differently from ![]() syllables. These are analysed as involving two syllables by Rivierre, an analysis I do not question in this article. There are only nine such words in Shintani & Païta’s (Reference Shintani and Païta1990a) Drubea dictionary, many of which are low-frequency words (e.g., specific worm or shellfish species). The only two that are found with mid-to-high frequency in Shintani’s recordings (Shintani Reference Shintani2019; Académie des Langues Kanak 2023) are the verbs

syllables. These are analysed as involving two syllables by Rivierre, an analysis I do not question in this article. There are only nine such words in Shintani & Païta’s (Reference Shintani and Païta1990a) Drubea dictionary, many of which are low-frequency words (e.g., specific worm or shellfish species). The only two that are found with mid-to-high frequency in Shintani’s recordings (Shintani Reference Shintani2019; Académie des Langues Kanak 2023) are the verbs ![]() ‘to do, to make’ and

‘to do, to make’ and ![]() ‘to arrive’. I have not found one clear instance of downstep displacement involving these two words in the corpus. The speech rate of the speakers is too high in most cases to make it possible to clearly determine the exact realisation, and in those rare cases of relatively careful speech, the downstep is not displaced, but clearly realised on the second vowel:

‘to arrive’. I have not found one clear instance of downstep displacement involving these two words in the corpus. The speech rate of the speakers is too high in most cases to make it possible to clearly determine the exact realisation, and in those rare cases of relatively careful speech, the downstep is not displaced, but clearly realised on the second vowel: ![]() ,

, ![]() . The Numèè cognate of the verb ‘to arrive’ is

. The Numèè cognate of the verb ‘to arrive’ is ![]() . This verb is used several times in every one of the eight Numèè texts collected by Haudricourt & Rivierre (Reference Haudricourt and Rivierren.d.) and archived in the Pangloss collection. In all instances, the downstep is clearly heard between the two vowels, with no displacement. This is not a full and detailed investigation of this question, for which more carefully articluated data are necessary, but it seems to at least suggest that Rivierre was likely correct in identifying

. This verb is used several times in every one of the eight Numèè texts collected by Haudricourt & Rivierre (Reference Haudricourt and Rivierren.d.) and archived in the Pangloss collection. In all instances, the downstep is clearly heard between the two vowels, with no displacement. This is not a full and detailed investigation of this question, for which more carefully articluated data are necessary, but it seems to at least suggest that Rivierre was likely correct in identifying ![]() syllables as having special status, different from

syllables as having special status, different from ![]() sequences (and more generally that his analysis of sequences of like vowels as long vowels and sequences of unlike vowels as heterosyllabic is likely correct).

sequences (and more generally that his analysis of sequences of like vowels as long vowels and sequences of unlike vowels as heterosyllabic is likely correct).

Note that the existence of ![]() syllables shows that the element carrying the indication of register is not the syllable, but the mora. I will come back to this in detail in §4.2.

syllables shows that the element carrying the indication of register is not the syllable, but the mora. I will come back to this in detail in §4.2.

3.8. Stems of more than two syllables

While most stems in Drubea and Numèè are either mono- or disyllabic, stems of more than two syllables (mostly three or four) are also attested. However, neither Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973) nor Shintani & Païta (Reference Shintani and Païta1990b) give a detailed description of their tonal behaviour. Rivierre acknowledges the difficulty of establishing the morphological structure of words of more than two syllables. Compounding is indeed frequent, and many of the long words that he was not able to identify as compounds may turn out to be complex, something he was not able to systematically verify in the field for lack of time (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 129–130).

On the basis of the limited data he collected, Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 130) hypothesizes that tri- and tetrasyllables, like mono- and disyllables (cf. §3.10 below), are limited to containing at most one downstep (‘L tone’ in his analysis).Footnote 29 Rivierre further surmises that those with more than one downstep are actually compounds. This implies that each member of a compound constitutes an independent prosodic domain (which I call ‘stem’ here). The culminativity constraint of downstep is enforced within this domain, but not at the level of the entire morphological word. Indeed, it is quite common for compounds to include more than one downstep when they combine several stems containing a downstepped element, as in the examples in (55) (compound elements are separated by a middle dot).

Rivierre’s hypothesis is supported by the fact that, cross-linguistically, compounds have a tendency not to constitute a single tonal or prosodic domain. Examples include such different languages as the isolate Laal of Chad (Lionnet Reference Lionnet2022a) and the Juǀ’hoan language of Namibia (Kx’a, formerly Northern Khoisan; Miller Reference Miller, Brenzinger and König2010). Closer to Drubea and Numèè, this is also the case in Paicî, another tonal language of New Caledonia, in which each member of a compound constitutes an independent tonal domain, notably for the application of a similar culminativity constraint limiting the number of downsteps per tonal domain to exactly one (Lionnet Reference Lionnet2022b).

I set tri- and tetrasyllabic words aside in this article. A full investigation of their prosodic behaviour requires additional data collection from native speakers, which I have not been able to conduct yet. I can only say that in transcribing a selection of Shintani’s (Reference Shintani2019) recorded texts, none of the (seemingly) monomorphemic tri- or tetrasyllabic words I have encountered contained more than one downstepped syllable, or jeopardised in any way the register analysis proposed in this article.

3.9. Verbal classifier prefixes

Morpheme concatenation in Drubea and Numèè, either by compounding or by affixation, does not seem to interact in any significant way with the prosodic behaviour of the morphemes involved. Affixes are all registerless, except verbal classifier prefixes.Footnote

30

These modify the meanings of verb bases in systematic ways, such as ![]() ‘verb with one’s teeth’,

‘verb with one’s teeth’, ![]() ‘verb with a knife’. These prefixes are always monosyllabic, and take on the prosodic specification of the initial syllable of the verb they are prefixed to (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 140–141; see also Shintani & Païta Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 46). This is illustrated with the Drubea prefix

‘verb with a knife’. These prefixes are always monosyllabic, and take on the prosodic specification of the initial syllable of the verb they are prefixed to (Rivierre Reference Rivierre1973: 140–141; see also Shintani & Païta Reference Shintani and Païta1990b: 46). This is illustrated with the Drubea prefix ![]() ‘verb with one’s hand’ in (56).

‘verb with one’s hand’ in (56).

The example in (57) shows that the prefix in ![]() [ꜜʈa-ꜜtie] is indeed downstepped, as can be seen from the fact that it triggers pre-downstep raising of the preceding registerless syllable

[ꜜʈa-ꜜtie] is indeed downstepped, as can be seen from the fact that it triggers pre-downstep raising of the preceding registerless syllable ![]() . The fact that the there is still a pitch drop between the prefix and the verb also shows that the downstep on the prefix is indeed a copy of the downstep of the initial syllable of the verb

. The fact that the there is still a pitch drop between the prefix and the verb also shows that the downstep on the prefix is indeed a copy of the downstep of the initial syllable of the verb ![]() rather than a realignment of this downstep to the left edge of the morphological word.

rather than a realignment of this downstep to the left edge of the morphological word.

3.10. Summary

The word-prosodic system of Drubea and Numèè is entirely built on one underlying binary contrast: registerless (i.e., prosodically unspecified) vs. downstepped elements. These elements are either entire syllables as in ![]() and

and ![]() , or the second mora of a syllable, as in the case of

, or the second mora of a syllable, as in the case of ![]() syllables, which suggests that both the syllable and the mora have a role to play, a point I address in more detail in §4.2. Downstep is realised as a downward register contrast with what precedes. It is not realised utterance-initially, where the conditions for this contrast are not met. In that case, the downstep is simply left unrealised, and downstepped elements are pronounced just like registerless ones at baseline pitch, a high-mid default pitch schematically represented as level 4 on the typical 1-to-5 scale. Registerless elements are prosodically inert; that is, their realisation is entirely context-dependent. When utterance-initial, they are realised at baseline pitch. In non-initial position, they are realised by default at the same pitch as the preceding (downstepped or registerless) element. When followed by a downstepped element (including when in utterance-initial position), they tend to undergo pitch raising, to emphasize the downward contrast that follows. Finally, registerless elements are sensitive to utterance-final prosodic phenomena: final raising in Drubea, final lowering in Numèè.

syllables, which suggests that both the syllable and the mora have a role to play, a point I address in more detail in §4.2. Downstep is realised as a downward register contrast with what precedes. It is not realised utterance-initially, where the conditions for this contrast are not met. In that case, the downstep is simply left unrealised, and downstepped elements are pronounced just like registerless ones at baseline pitch, a high-mid default pitch schematically represented as level 4 on the typical 1-to-5 scale. Registerless elements are prosodically inert; that is, their realisation is entirely context-dependent. When utterance-initial, they are realised at baseline pitch. In non-initial position, they are realised by default at the same pitch as the preceding (downstepped or registerless) element. When followed by a downstepped element (including when in utterance-initial position), they tend to undergo pitch raising, to emphasize the downward contrast that follows. Finally, registerless elements are sensitive to utterance-final prosodic phenomena: final raising in Drubea, final lowering in Numèè.

Table 2 Downstep distribution in mono- and disyllabic stems.

The distribution of downstep within mono- and disyllabic stems is summarised in Table 2. One interesting property that emerges is culminativity: a stem may include at most one downstep, as was already noted by Rivierre (Reference Rivierre1973: 128).Footnote

31

This downstep may affect the first or second syllable of disyllables. It may also affect the second mora of a bimoraic ![]() syllable. In the native vocabulary, this is found only with monosyllabic

syllable. In the native vocabulary, this is found only with monosyllabic ![]() stems.

stems. ![]() stems are also attested, but all are recent loanwords, mostly from English and French.

stems are also attested, but all are recent loanwords, mostly from English and French. ![]() stems are strictly unattested. (The optionality of the onset consonant is not indicated in the schematic syllable structures given in Table 2;

stems are strictly unattested. (The optionality of the onset consonant is not indicated in the schematic syllable structures given in Table 2; ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() stand for

stand for ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively.)

, respectively.)

4. Register analysis

In the preceding section, I described the word-prosodic system of Drubea and Numèè as consisting of a contrast between downstepped units and registerless units. In this section, I propose an analysis of this contrast and of the prosodic behaviour of these units in terms of register features, demonstrating that no tone or tonal feature is necessary to account for the word-prosodic system of Numèè and Drubea, which are thus not tonal languages stricto sensu, but languages that use register for lexical contrast.

4.1. A brief history of the representation of tone and register

The representation of register phonemona like downstep and upstep results from a long history of attempting to extend featural representations to tone – that is, to represent tone as a bundle of features, and explain tonal behaviour with the properties of these features (e.g., Wang Reference Wang1967; Yip Reference Yip1980, Reference Yip1989; Clements Reference Clements and Clements1981; Hyman Reference Hyman, Snider and van der Hulst1993; Pulleyblank Reference Pulleyblank1986; Snider Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020). The most widely used feature system is that proposed by Yip (Reference Yip1980) and refined by Pulleyblank (Reference Pulleyblank1986), which makes use of two features: one ‘register’ feature [±upper], dividing the tone range into an upper and a lower register, and a secondary feature [±high] (Yip) or [±raised] (Pulleyblank) further subdividing each register into two discrete tonal categories. In this system, a four-height tonal contrast would be analysed as in (58) below.Footnote 32

Snider’s (Reference Snider1999; Reference Snider2020) Register Tier Theory is superficially very similar to the above approaches in proposing a four-way contrast using two types of features: two register features h (high) and l (low), and two tone features H (High) and L (Low). Snider’s system is, however, different from all others in one crucial point: the definition of the register features. Indeed, while his two tone features H and L can be considered the exact unary equivalents of Yip’s and Pulleyblank’s binary [+raised]/[+high] and [−raised]/[−high], respectively, his two register features h and l are not equivalent to Yip’s and Pulleyblank’s register feature [±upper]. The latter is defined in purely paradigmatic terms: [+upper] tones are realised within the upper half of the register, while [−upper] tones in the same environment would be realised in the lower half of the same register. In contrast, Snider’s h and l register features are defined in syntagmatic terms: they ‘effect a register shift h = higher and l = lower relative to the preceding register setting’ (Snider Reference Snider2020: 25; emphasis mine; see also pp. 151–153). In other words, h and l are defined as overt representations of upstep ![]() and downstep

and downstep ![]() , which I show in this section are very well suited to account for the Drubea and Numèè facts described above.Footnote

33

, which I show in this section are very well suited to account for the Drubea and Numèè facts described above.Footnote

33

Snider (Reference Snider1999, Reference Snider2020) further refines the featural representation of tone by proposing a geometry in which register and tone features are linked to a tonal root node (TRN), which is itself associated with a tone-bearing unit (TBU), as shown in (59).

The TRN unites register and tone features into a single bundle defining individual tones (e.g., low = Ll, high = Hh, mid = Lh or Hl), exactly as the C and V root nodes in feature geometry unite segmental features into bundles defining individual segments (Sagey Reference Sagey1986; Clements & Hume Reference Clements, Hume and Goldsmith1995). This representation makes it possible to account for the fact that low tones have a very strong cross-linguistic tendency to downstep a following H tone. Indeed, a low tone is always specified as l on the register tier (and L on the tone tier), that is, as a downstep-inducing element.Footnote 34

In the rest of this section, I show that register features, in Snider’s syntagmatic definition, are sufficient to account for the word-prosodic system of Drubea and Numèè. In other words, register features need not be paired with tone features and may be active in a phonological system even in the absence of tone features.

4.2. Stem-level patterns and the register-bearing unit

I propose to analyse downstepped RBUs in Drubea and Numèè as being underlyingly associated with a l register feature. Note that in the absence of tone features, the TRN is unnecessary, and so I omit it from the representations. The distribution of this l feature in mono- and disyllabic stems, summarised in Table 2, has two characteristics: (i) there are only three stem-level register patterns:

![]() $\varnothing $

, l, and

$\varnothing $

, l, and

![]() $\varnothing $

l; and (ii) the RBU is the mora, with a strong syllabic constraint: register features associate with the leftmost mora of a syllable. This accounts for all the native mono- and disyllabic stem shapes described in §3 and listed in Table 2, that is, all register-less stems (the

$\varnothing $

l; and (ii) the RBU is the mora, with a strong syllabic constraint: register features associate with the leftmost mora of a syllable. This accounts for all the native mono- and disyllabic stem shapes described in §3 and listed in Table 2, that is, all register-less stems (the

![]() $\varnothing $

pattern), stems with an initial downstepped syllable (the l pattern), and stems with a downstepped second syllable (the

$\varnothing $

pattern), stems with an initial downstepped syllable (the l pattern), and stems with a downstepped second syllable (the

![]() $\varnothing $

l pattern). It also accounts for monosyllabic

$\varnothing $

l pattern). It also accounts for monosyllabic ![]() stems, as discussed below.

stems, as discussed below.

This analysis predicts that syllable-internal downstep (i.e., downstep affecting the second mora of a long vowel) should only be allowed in monosyllabic bimoraic stems, as a result of their combination with the

![]() $\varnothing $

l pattern. The l feature in this case exceptionally associates with the second mora, for lack of a second syllable. In disyllabic stems, on the other hand there are always enough syllables for all patterns to align their l feature with the leftmost mora of a syllable. As can be seen in Table 3, the constraint that l be aligned with the left edge of the syllable means that only mappings (a) (for l associated with a

$\varnothing $

l pattern. The l feature in this case exceptionally associates with the second mora, for lack of a second syllable. In disyllabic stems, on the other hand there are always enough syllables for all patterns to align their l feature with the leftmost mora of a syllable. As can be seen in Table 3, the constraint that l be aligned with the left edge of the syllable means that only mappings (a) (for l associated with a ![]() stem) and (c) (for

stem) and (c) (for

![]() $\varnothing $

l associated with a

$\varnothing $

l associated with a ![]() stem) are possible. As we saw in §3.10, mapping (d) is strictly unattested, and mapping (b) is found only in recent loanwords. I will ignore these loanwords in the remainder of this article. Nothing in their behaviour suggests any incompatibility with the register analysis proposed here. These could either be analysed as involving an exceptional

stem) are possible. As we saw in §3.10, mapping (d) is strictly unattested, and mapping (b) is found only in recent loanwords. I will ignore these loanwords in the remainder of this article. Nothing in their behaviour suggests any incompatibility with the register analysis proposed here. These could either be analysed as involving an exceptional

![]() $\varnothing $

l

$\varnothing $

l

![]() $\varnothing $

pattern confined to loanwords, or be treated as compounds, that is, two separate prosodic domains:

$\varnothing $

pattern confined to loanwords, or be treated as compounds, that is, two separate prosodic domains:

![]() $\varnothing $

l monosyllabic

$\varnothing $

l monosyllabic ![]() plus register-less monosyllabic

plus register-less monosyllabic ![]() .Footnote

35

Note that

.Footnote

35

Note that ![]() syllables constitute the only evidence that the mora plays any role in register feature association. Without these stems, the RBU would be defined as the syllable. All attested native mono- and disyllabic stem shapes are thus accounted for by the analysis, as shown in Table 4.

syllables constitute the only evidence that the mora plays any role in register feature association. Without these stems, the RBU would be defined as the syllable. All attested native mono- and disyllabic stem shapes are thus accounted for by the analysis, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3 Attested and unattested register pattern mappings on disyllables.

Table 4 Mapping of register patterns onto mono- and disyllabic native stems.

4.3. Register analysis: the basics

An utterance containing a sequence of downstepped monosyllabic morphemes, as in (11), is represented as in (60).Footnote 36

The utterance-initial downstep on ![]() is not realised, as seen in §3.5. We will see in §4.5 that this unrealised downstep is actually still phonologically active, and not deleted, hence its presence in parentheses in the surface transcription. Each one of the following l features is realised as a register drop, taking the speaker step by step all the way down to the lower end of their pitch range.

is not realised, as seen in §3.5. We will see in §4.5 that this unrealised downstep is actually still phonologically active, and not deleted, hence its presence in parentheses in the surface transcription. Each one of the following l features is realised as a register drop, taking the speaker step by step all the way down to the lower end of their pitch range.

An utterance involving only registerless morphemes remains devoid of any register indication, and is thus, by default, realised at the baseline. The same is true of utterances whose only l-bearing RBU is utterance-initial, as in example (31): the initial downstep is not realised, making such utterances prosodically identical to ones with no downstep at all (although see §4.5).

Registerless RBUs following a downstepped RBU are by default (and in the absence of any following downstep) realised at the same pitch as the downstepped RBU in question, as we saw in §§3.1 and 3.2. This could be interpreted as the result of spreading the l feature to all following registerless RBUs, as in (61), which shows the representation posited for (43); the same spreading also applies to ![]() in (60b). The final

in (60b). The final ![]() boundary feature will be discussed in §4.8.

boundary feature will be discussed in §4.8.

However, the realisation of registerless RBUs is highly variable, as we have seen. In addition to their utterance-initial default baseline realisation, they are also subject to pre-downstep raising, final raising (Drubea) or lowering (Numèè), and extrapolation. Spreading of the preceding register feature to account for same-pitch realisation is thus at best optional (if even necessary), and will henceforth not be represented. Registerless RBUs will be left unassociated, which is an apt representation of their availability to variable realisations.

4.4. Pre-downstep raising as h-epenthesis

Pre-downstep raising can be analysed as the optional postlexical assignment of a h register-raising (= upstep) feature, as illustrated in (62), where every registerless syllable followed by a downstep is affected.

This inserted h feature may not delete an underlying l. As we saw in §3.2, pre-downstep raising affects mostly registerless RBUs, and is rarely seen with downstepped RBUs. When it does affect a downstepped RBU, as in (18), the raising occurs after the pitch drop triggered by the downstep. That is, the postlexical insertion of the h feature creates a register contour l͡h on a single mora, as illustrated in (63), which shows the representation of (18).

4.5. Utterance-initial downstep

As we saw in §3.5, the downstep is not realised utterance-initially, where there is no distinction in pitch between a downstepped RBU and a registerless one – if the following RBU is registerless. The contrast between downstepped and registerless syllable is, however, maintained whenever the utterance-initial syllable is followed by a downstepped RBU. In this case, a registerless syllable undergoes pre-downstep raising, while a downstepped one does not. This can easily be accounted for by positing that the l feature on the utterance-initial RBU is not deleted, but only left unrealised, for lack of a preceding RBU to contrast with. That is, the lack of phonetic distinction between registerless and downstepped syllables in this position is the result of the identical phonetic implementation of two otherwise contrastive phonological objects.

The presence of this unrealised l feature is revealed by the fact that it prevents pre-downstep raising, that is, h-epenthesis.Footnote

37

This can be seen by comparing (64) and (65), which represent the minimal pair in (32) and (33). In (64), registerless ![]() ‘Hibbertia pancheri’ is targeted by h-epenthesis caused by the following downstepped adjective

‘Hibbertia pancheri’ is targeted by h-epenthesis caused by the following downstepped adjective ![]() . In (65), on the other hand, l-carrying

. In (65), on the other hand, l-carrying ![]() ‘tree’ fails to undergo h-epenthesis in the same context.

‘tree’ fails to undergo h-epenthesis in the same context.