J’ai trouvé (RS474 = RS431) is a thirteenth-century dance song that, unusually for dance songs of this period, survives in more than one copy, one of which has musical notation.Footnote 1 Various scholars have pointed out its formal similarity to an estampie, a designation it may have had in a now-lost source, but its appearance in the surviving manuscripts suggests two further different generic designations.Footnote 2 In Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fr. 845 (hereafter N) it is called a note in the marginal rubrication, ‘la note Martinet’ (‘little Martin’s note’, or, to use an English diminutive, ‘Marty’s tune’).Footnote 3 It appears in the final few folios of N, a manuscript which is part of a family of tightly similar manuscripts.Footnote 4 Marty’s tune is in a now-disordered final section of N, with material not found in the other three manuscripts in the family, which includes motets entés and lais. In the original order, Marty’s tune may have been copied on a final bifolio.Footnote 5 In Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 308 (hereafter D308), which contains a songbook organised by genre, it is included in a clearly labelled subsection of pastourelles. These two surviving copies, while clearly of the same piece, differ in ways that have not been discussed in detail. Earlier scholars typically posited a ‘correct’ version in an editorial composite that irons out the form to give a more regular structure, which is found in neither version. While both versions may present errors – many of omission, some shared – I argue here that they offer a unique chance to view stages in the transfer to this unusually literate state of what was more often a non-literate genre. In the second half of this article, therefore, I compare the texts of the two copies and – by looking at what the musical form tells us about their textual differences – advance hypotheses about the compositional, scribal and performance processes that might have produced this song. First, however, I review the place this song has occupied in the work on French-texted medieval dance song in the period before the establishment of the formes fixes as featured in the work of Machaut. This review shows that scholars have differed in their assessment of what exactly this song is, both generically and, as we shall see, formally. Ultimately, this situation leads to my own re-reading of the musical, poetic and manuscript evidence.

Repeating the history of the note

Scholars have discussed J’ai trouvé (RS474) for well over a hundred years, but tend to repeat the same basic facts about it. They draw attention to its sequence-like melodic organisation and assert the likelihood it is some kind of estampie, a status befitting the pairing of nota (i.e., note) and stantipes (i.e., estampie) in theorist Johannes de Grocheio’s Ars musica. Footnote 6 In the process, the song goes from being the one surviving instance of a notated nota for the earliest twentieth-century musicological discussions, to being one of a very few explicitly labelled examples among a larger number of potential candidates for inclusion in the genre by the late 1980s. Its exemplification of the genre of the nota, as suggested by N’s rubric, is taken far more seriously than its inclusion in the pastourelles of D308. As I show, however, the idea that the note is a distinct genre or one that is some kind of estampie with special dance steps is unconvincing.

In his 1930 study of dancing in medieval churches, Hans Spanke emended Pierre Aubry’s rendering of a prohibition on various forms during Christmastide to read ‘notulis’ rather than ‘motulis’, with a footnote clarifying the nota or notula as an instrumental form related to the sequence and later given ‘worthless’ words.Footnote 7 Spanke further avers that RS474, for him the only surviving example of the nota, is ill aligned with Grocheio’s use of the number of puncti to differentiate it from the ductia and stantipes: ‘contrary to the (often unreliable) pronouncements of the theoretician [i.e., Grocheio], Note Martinet has more than four puncti and is thus closer to the estampie’.Footnote 8 Two years later, Friedrich Gennrich reported Spanke’s comments and offered a transcription of both RS474 and a second surviving notated example, Olim in harmonia, a Latin contrafact in Adam de la Bassée’s Ludus super anticlaudianum, which a rubric describes as a ‘notula’.Footnote 9 Gennrich comments that Adam’s contrafact is rather different from RS474, being more like a lai, while agreeing with Spanke that RS474 is closer to the estampie.Footnote 10 Both songs are similar to the extent that they have six stanzas (although on the issue of the stanza count for RS474, see later) and many of the stanzas have similar cadences at their end, at least for the last three notes, making their tonal shape very clear. But Olim in harmonia presents the first five stanzas in a double-versicle structure, the first four strictly and the fifth with only minor variations between the two versicles’ terminal cadences; only the last stanza, the sixth, significantly departs from this format, lacking repetition of melodic material.Footnote 11

In the same year as Spanke’s study, Jacques Handschin published the second part of an enquiry into estampie and sequence forms, in which he also offered a transcription of RS474.Footnote 12 Handschin explains that the sequence form was followed less rigidly in early sequences as well as in secular examples such as the estampie, and his transcription and analysis of RS474 exemplifies just how freely the double-versicle structure may be handled in the secular estampie.Footnote 13 His complex diagramming of the melody includes several sections labelled as ‘extended’ (erweitert) and he attempts to valorise the song’s organicism by comparison with a Beethoven sonata, claiming that its artistry likewise encompasses the relationship of small motivic elements, which can be similar and varied and in which there is a mirroring of the smallest in the largest.Footnote 14 Handschin finds this ‘dense network of motivic relationships familiar in later musical art’ most pronounced in sequence, lai and estampie in which he suspects one can ‘still grasp one of the Celtic roots of medieval intellectual life’.Footnote 15 While these organicist and originary ramifications might be used today only as evidence in a history of the pervasiveness of early twentieth-century racial teleologies, the way early commentators were struck by the complexity and motivic interest in La note Martinet’s melody remains persuasive once shorn of such earlier historiographical framing. And while Handschin, like Spanke and Gennrich, relates the nota closely to the estampie, unlike them he does not deny that Grocheio’s description for the nota fits RS474, claiming instead that the number of puncti that Johannes gives for the nota applies to RS474, as does the closed cadence’s greater length compared to the open cadence in each double versicle. Nevertheless, Handschin grants that La note Martinet seems less difficult – more popular, and tonally clearer – than Grocheio claims the nota to be.Footnote 16

The first mention of RS474 in English was made in 1940 by Gustave Reese, who includes La note Martinet as one of two surviving examples with the designation ‘notula’, in his discussion of the sequence-type forms of medieval music.Footnote 17 Reese, too, links the nota form to the estampie on account of the presence of recurrent terminations, so that for him RS474 is like a ‘sequence with a doubled cursus except that, in the group repetition, some units are omitted’.Footnote 18 He echoes Gennrich’s point that the number of puncti described by Grocheio for the nota do not agree with the examples, something that both think should make us doubt Grocheio’s reliability.Footnote 19 Reese directs his reader in a footnote to the two ‘somewhat different’ transcriptions of Gennrich and Handschin.Footnote 20

The attention of Spanke, Handschin and Reese was effectively all this song received until the late 1980s, when, in the course of treating the isostrophic estampies of D308 (nos. 1 and 6 in the estampie subsection of that manuscript), literary scholar Dominique Billy stated that no. 6 (i.e., RS474) is clearly out of place in the pastourelles. He aligns it rather with D308’s estampies, citing Handschin’s tight relation of it to the latter and remarking that it would have carried this label in the lost chansonnier de Mesmes.Footnote 21 Slightly later, Timothy McGee’s article comparing surviving dances with Grocheio’s descriptions of dance forms mentions RS474 as one of only two surviving compositions explicitly identified as a nota in medieval sources, both of which are texted.Footnote 22 Like Gennrich, McGee stresses the difference between Adam de la Bassée’s contrafact nota with its equal-length double-versicle structure and La note Martinet’s irregular phrases (‘some of them double versicles, others single’), and the refrain-like cadence ‘that recurs at irregular periods throughout the composition’. He concludes that ‘the irregular length of the phrases relate this piece to the estampie’.Footnote 23 McGee reads Grocheio as claiming that the nota is broadly akin to both ductia and estampie, without being truly either, hypothesising that ‘nota’ is a ‘catch-all’ for ‘dance compositions with unique forms that bear some resemblance to other forms’.Footnote 24

McGee wonders if the term ‘nota’ refers either to something specific about the kind of dance steps or to them being ‘notated’.Footnote 25 He cites one fourteenth-century literary use of ‘note’ in French, where he claims that a list in Jehan Maillart’s Roman du Comte d’Anjou means that ‘it is clear from this reference that the nota was a dance type distinct from estampie, “danse” and “baleriez”.’Footnote 26 I am not convinced that such a conclusion is at all clear from this passage, however: Maillart’s list is one of those that typify verse romances’ rhetorical strategies of conjuring up a rich diversity of musical entertainment within the constraints of rhymed couplets. While ‘lais et sons’ is a frequent doublet, ‘sons et notes’ or ‘lais et notes’ can also be used as a pair, or many of these combined in a list, which includes ‘chansons’ (songs), ‘notes’, ‘lais’ and ‘conduis’ (conducti). These are often ‘vïeleir’ (played on a fiddle) and/or sung (‘chanter’); ‘conduit’ typically rhymes with ‘deduit’ (delight), ‘note’ with ‘rote’ (rote) or ‘flote’ (flute); in one case, a manuscript variant substitutes ‘Chansons, notes’ for ‘chansenete’, and in another ‘flotes’ for ‘notes’.Footnote 27

McGee tentatively identifies four two-voice compositions (three in London, British Library, Harley 978 and the fourth in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 139) as examples of the nota purely because they all have double-versicle structures.Footnote 28 This seems to me to take the idea of note as a form and/or genre far too seriously. The phrases ‘a note’ and ‘sans note’ are used to mean works sung to a melody and spoken without one, respectively, and a wider consideration of literary examples from the standard dictionaries offers no example in which ‘note’ could not mean merely ‘melody’ in general.Footnote 29 In the Roman de la Rose, for example, the phrase ‘notes Loherenges’ is translated by Chaucer as ‘songs of Loreyne’ and then two lines later as ‘notes’, implying these terms are synonymous.Footnote 30

Plenty of literary examples suggest that the ‘note’ serves a poem that is in a different, specified genre. This supports the idea of ‘note’ as pertaining specifically to the melodic part of a song. In Gerbert de Montreuil’s Le Roman de la violette, for example, the sister of the Count of Saint-Pol ‘Commenche haut, a clere note, | Ceste chanchon en karolant’.Footnote 31 This wording implies that the song is a chanchon, sung with a distinct note to accompany someone karolant, giving a sense of a singer who ‘begins aloud, with a distinct tune, this song, while dancing a carole’. Similarly, at the opening of the anonymous Lai des amants, the singing first-person je says:

(Here begins, entirely in French, the noble Lai des amans. The song is distilled from love and a refined lover made it; the entire melody (note) of its little tune (sonet) is of love. The one who is good sings it from love and notes it [see below]: whoever puts it in their heart takes up something good.)

This song identifies itself as a lai, as a song, and the phrase ‘la note | Del sonet’ suggests at the least that it is a sonet made up of notes. Even here in a poem that, given its poetic form, would surely have had some kind of double-versicle musical structure (such as an estampie, lai or some of the stanzas in RS474), the term ‘note’ is not a generic or formal designation. And the ambiguity of ‘note’ in line 8 is that it contrasts with singing so perhaps means ‘writing down in musical notation’, or ‘putting musical notes to it’, but might also mean ‘noting’ in the sense of ‘taking notice of’ (given the sense of ‘note’ as sign) or, as the final couplet implies, learning by heart, that is, memorising.Footnote 33

One song, by the trouvère Colin Muset, self-identifies as a ‘note’ in its opening and closing lines: ‘En ceste note dirai | D’une amorete que j’ai’ and ‘Ceste note est fenie’.Footnote 34 This song has notation in its three manuscript sources, but only for the first stanza. Given that it is heterostrophic (i.e., that each of the six stanzas has a different versification), this notation can only work for the first stanza.Footnote 35 Callahan and Rosenberg consider it a ‘lai-descort’ (whereas Jeanroy, Brandin and Aubry consider it merely a lai), and claim that it more closely resembles a song than a sequence in (melodic) form. They remark that it is ‘qualified in the incipit with a vaguer appellation: note’.Footnote 36 Billy, rejecting the mixed genre label of ‘lai-descort’, links La note Martinet and Colin’s ‘note’ to support his doubt that these pieces fitted in with the framework of what was conceived as a lai in the Middle Ages. For Billy, Colin’s ‘note’ is an original creation with little attachment to the lai genre, much like the note RS474, which, as Billy repeats, would likely have been designated an ‘estampie’ in the lost chansonnier Mesmes.Footnote 37 Nonetheless, when Hans Tischler includes Marty’s tune in his collected edition of all the trouvère melodies, he places it among the lais.Footnote 38

As can be seen from this review of earlier discussions, scholars have been unsure about both what RS474 actually is and what defines it as being that thing. The verse form of its poetry and, to a lesser extent, its melody, suggest it may be, as the label in a now lost chansonnier – at least as transcribed by a sixteenth-century witness – designated it, an estampie. But the estampie, too, is a relatively little attested and thus debated form and genre, so to insist that La note Martinet is an estampie simply poses further questions. Hitherto, this song’s clear placement in the explicitly labelled pastourelle subsection of D308 has not been given serious consideration. Yet if this song were perceived more as an estampie than as a pastourelle, it seems unlikely that the manuscript’s compilers would have put it in the pastourelle subsection, especially as this very manuscript has one of the few larger collections of – again, explicitly generically labelled – estampies. That the idea of RS474 as a pastourelle is typically dismissed as erroneous, relies on a general dismissal of D308’s value as well as on a rather circular modern definition of the pastourelle.Footnote 39 The poetic content of this song does not align with the modern expectation that pastourelles should present a scene in which a knight propositions a shepherdess. Nonetheless, the pastourelle subsection of D308 contains a good number of other poems that do not do this, including nun and monk scenes and songs that have garnered different generic designations in modern scholarship, such as songs of ill-wed wives (‘chansons de malmariée’), peasant revels (‘bergeries’) and general love songs. As I argue elsewhere, the extensive contents of the pastourelle subsection in D308 might usefully recalibrate the modern understanding of this genre.Footnote 40

The link between the pastourelle and dancing is close: pastourelles often describe dances and frequently use refrains that are a marker of dance types. Therefore, the presence of this dance form as no. 9 in the pastourelle subsection of D308, where it fills the entire folio, ostensibly ties it to the sort of entertainment described in the narrative poem that was designed to be bound with the songs of D308, Le tournoi de Chauvency. RS474’s short rhyming lines with their syllabic musical setting and (varied) double-versicle structure with open and closed endings, express highly sexualised sentiments describing the physical appearance of the beloved. The song uses ‘-ette’ diminutives characteristic of pastourelle poetry, and it applies them to more intimate bodily parts that do not feature in the grand chants. For example, stanza 5 invokes the beloved’s ‘hanchettes’ (little haunches, line 42) and claims her little breasts are more pert than little apples (‘Mamaletes | Plus durettes | Ke pomettes’, lines 46–8) and while the colour of her golden hair is courtly enough, it goes down in waves to her rather uncourtly ‘rains’ (literally ‘kidneys’, effectively ‘hips’, line 61).

Furthermore, if, as seems likely, the Mesmes chansonnier did indeed label it an estampie, this would suggest that an estampie and a pastourelle were not thought by their medieval users to be mutually exclusive designations. Pastourelles, like estampies, show a number of formal types. In D308, for example, the most common formal type, making up over half the total number of pastourelles, resembles the ‘ballade’ type refrain song in D308’s ballette subsection, that is, with an unchanging refrain (or one very lightly modified for sense) at the end of each stanza. Far less common (but implicitly an option in most cases, since some songs are found in both formats) pastourelles can place their unchanging refrain additionally at the start of the stanza, thereby exhibiting instead the ‘virelai-type’ ballette form.Footnote 41 The second most frequent type, however, is the simple ‘song’ type, a stanzaic song, which lacks any refrain. In addition, the chanson avec des refrains, a form that has different refrains at the end of each stanza, is found in the pastourelle subsection, too. Moreover, pastourelle texts also occur in polyphonic motet contexts. This means that pastourelle is a more capacious genre than typically appreciated in modern scholarship. Moreover, it is one that is not connected to a particular poetic or musical form. Thus the inclusion of RS474 in the pastourelles of D308 means only that this was the generic aspect uppermost in the song’s presentation, at least for the scribe or planner of this particular manuscript. This might depend on the linguistic and poetic content, despite the song not exemplifying the ‘classic’ pastourelle scene. The estampies of D308 generally lack highly sexualised and lower-register language, and are generally more courtly.Footnote 42 This said, the musical and poetic form of RS474, like its generic status, has been in some doubt, partly on account of the factual aspects of its dual transmission, their relation and their likely correspondence to either an authorial original or, indeed, any real medieval performed version. The rest of this article outlines the problems of the form of RS474, taking greater account of the assistance lent by the survival of musical notation in one of the two copies while not assuming that either manuscript can be used to point to a pristine, earlier or authorial copy.

Variants and errors in La note Martinet

As already noted, beyond disagreements as to its genre, the precise musico-poetic form of RS474 has been subject to debate. The issue is complicated by the level of variation between the two surviving manuscript versions, in which the differences between variant and error (particularly errors of omission) are difficult to diagnose (the texts are presented for comparison in the Appendix). The melody given in N for RS474 is one in which both repetition and its modification are important, achieved through the stability of cadences (marked as X in the Appendix) and their allowance of other kinds of variation: RS474’s cadential formula provides a fairly constant ending at the end of each half stanza. On the basis of the musical repetitions, most writers recognise two large sections in the song, within which smaller sections are delineated by that specific terminal melodic formula. The second large section is deemed to begin with a repeat of the opening figure, found in line 42, but the two large sections are not exact repeats of one another. Handschin posits four melodic subsections in the first half, the first three of which are broadly double-versicle structures and of which subsection 3 is immediately repeated (‘3 bis’); the second half of the large structure lacks subsection 3 entirely and repeats subsection 2 (‘2 bis’) instead, although the repetitions are not regular but extended (erweitert).Footnote 43 Gennrich, in contrast, chooses to regularise completely the repetitions, which forces him to posit missing lines in several places.Footnote 44 Compared with the copy in N, the version in D308 does indeed have several missing lines, but Gennrich is compelled to see omissions besetting N’s fuller copy too. While possible, Gennrich’s presupposition seems, for me, too normative and literary, when what we seem to have here is something that is a rather less formal kind of song text.

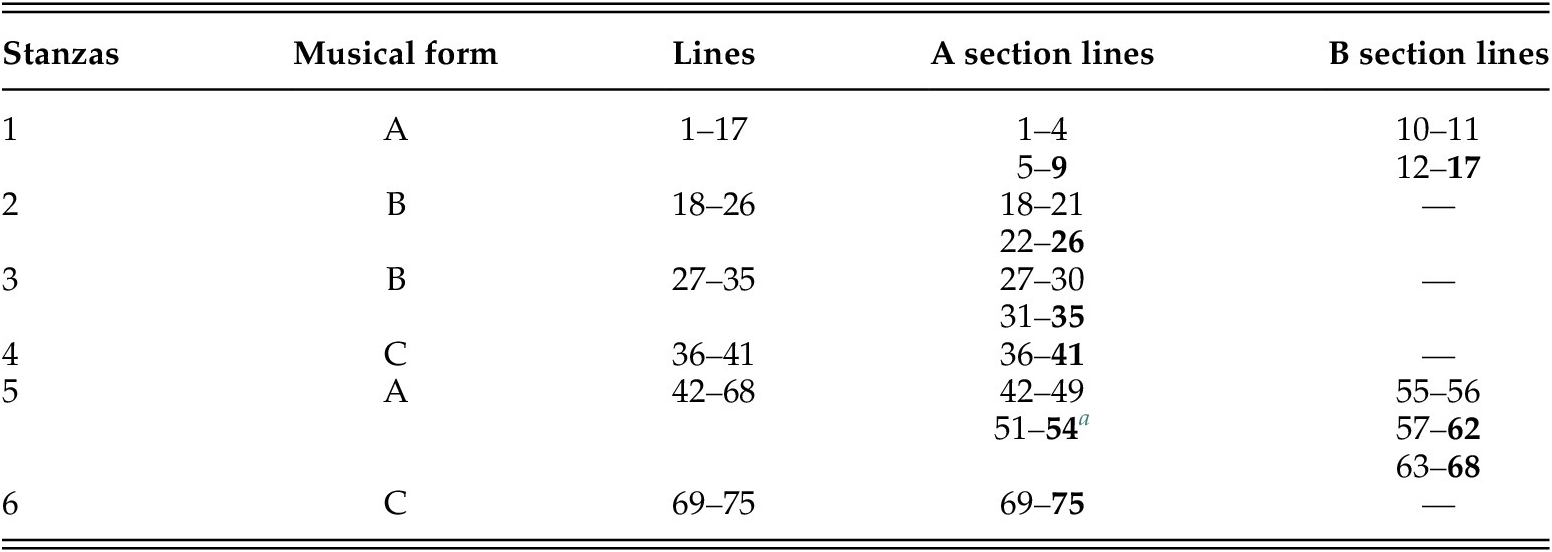

Within this overall form, therefore, something as fundamental as the number of stanzas present has been assessed differently by different writers (see the summary of approaches in Table 1). The manuscripts’ layout, also shown in Table 1, which might have aided this analysis, in fact complicates the picture: each copy places larger capitals at certain points, but the copies agree neither with each other nor with the structures suggested by the surviving music. D308 appears to signal only four stanzas. N appears to have ten, of which two (the first and the third) are marked by capitals illuminated with gold leaf; the second of these gold capitals (at line 27) adorns what can be seen musically as the almost direct repeat of the double-versicle melody of the previous nine (=4+5) lines. Neither manuscript has a capital letter for line 10, but Handschin, Gennrich and Christiane Schima all see the start of a new stanza there.Footnote 45 Except in placing this second stanza in line 10 (her line 9), Schima fits her form to nearly all of N’s capitals, with two exceptions: she does not consider the eighth or ninth capitals (my lines 57 and 63, her lines 53 and 58) as the start of a stanza, but instead views them as three subparts of stanza 8.

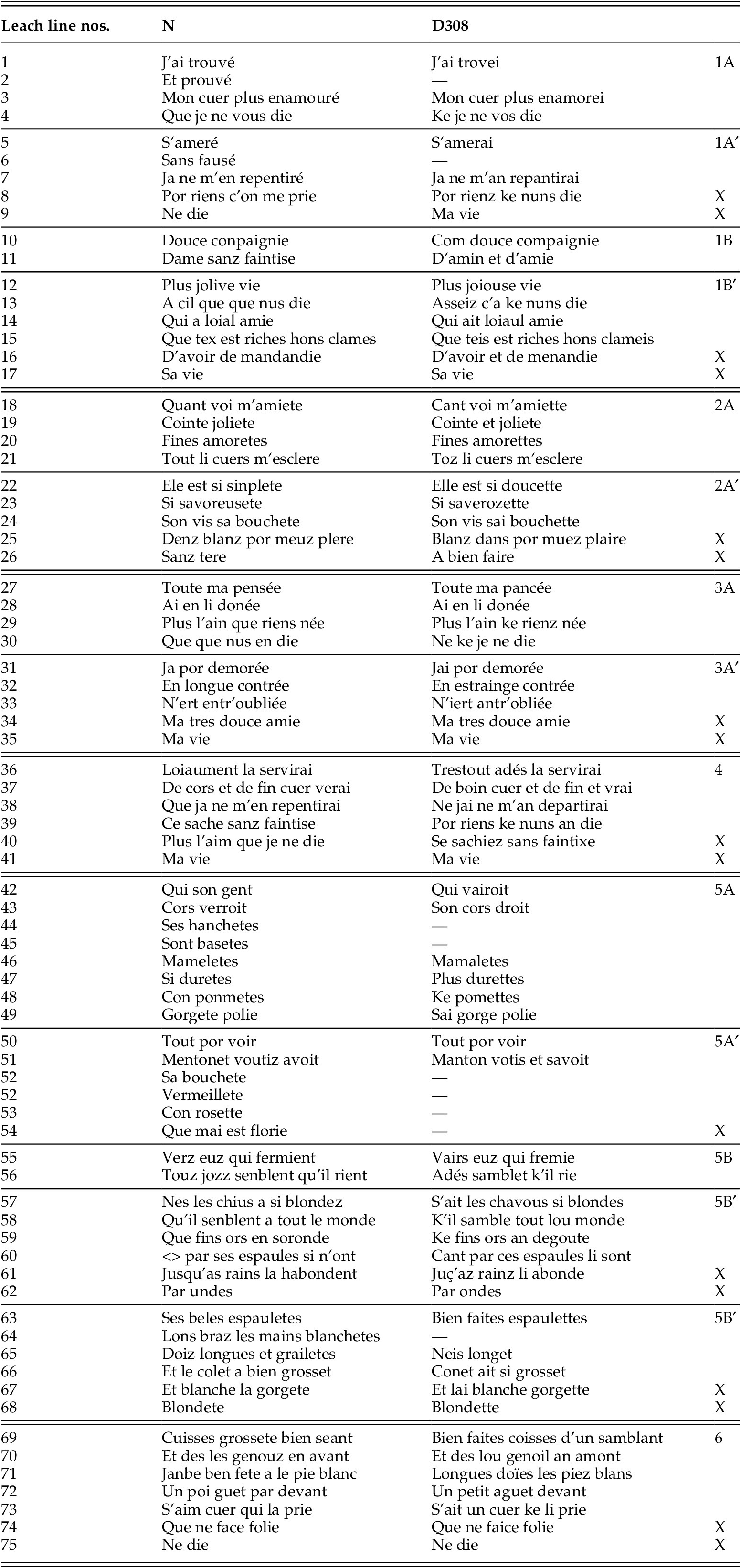

Table 1. Stanzaic structure as understood in earlier scholarship

a Line 39 deemed missing.

b Lines 52, 54 and 59 deemed missing; extra syllables supplied to line 53.

c Lines 68–9 deemed missing.

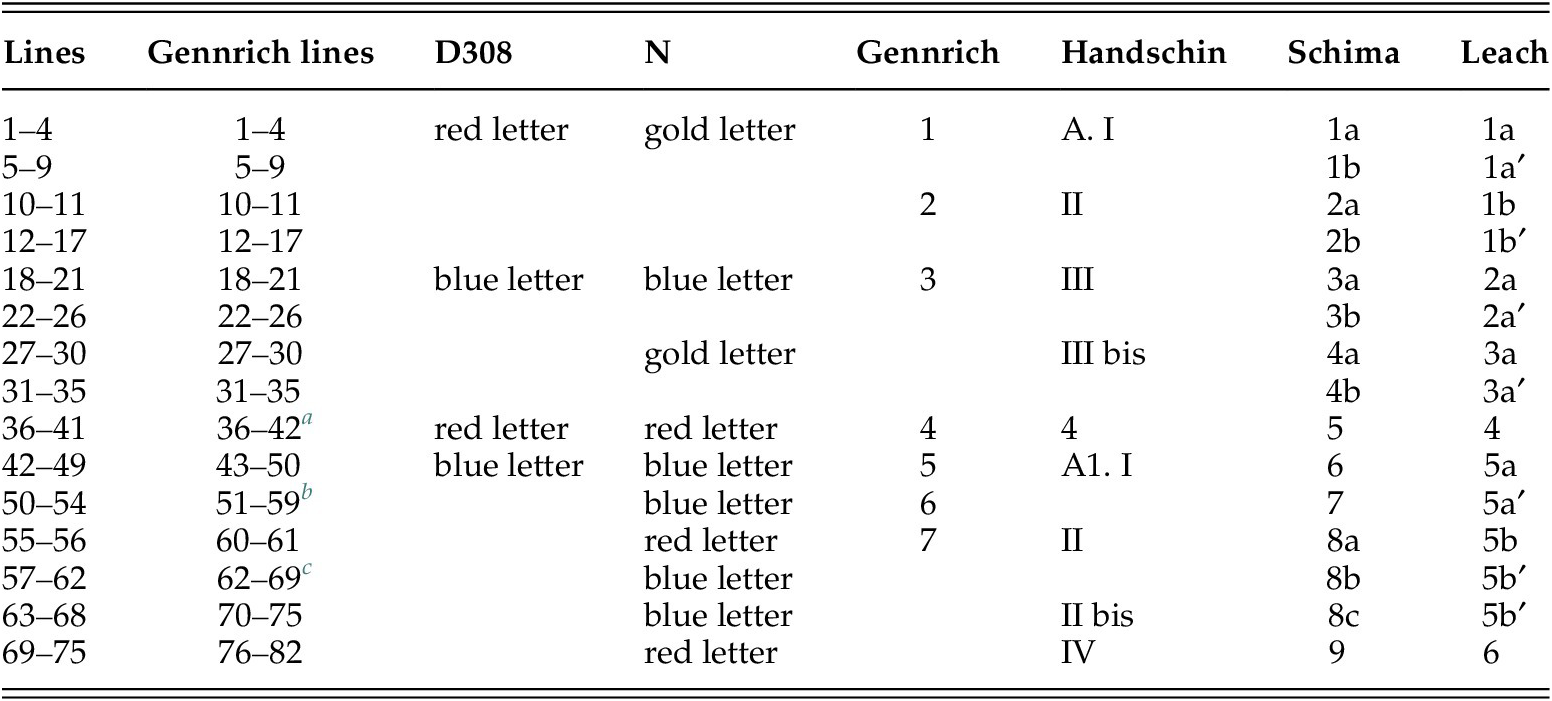

Example 1. A section of stanzas 1 and 5.

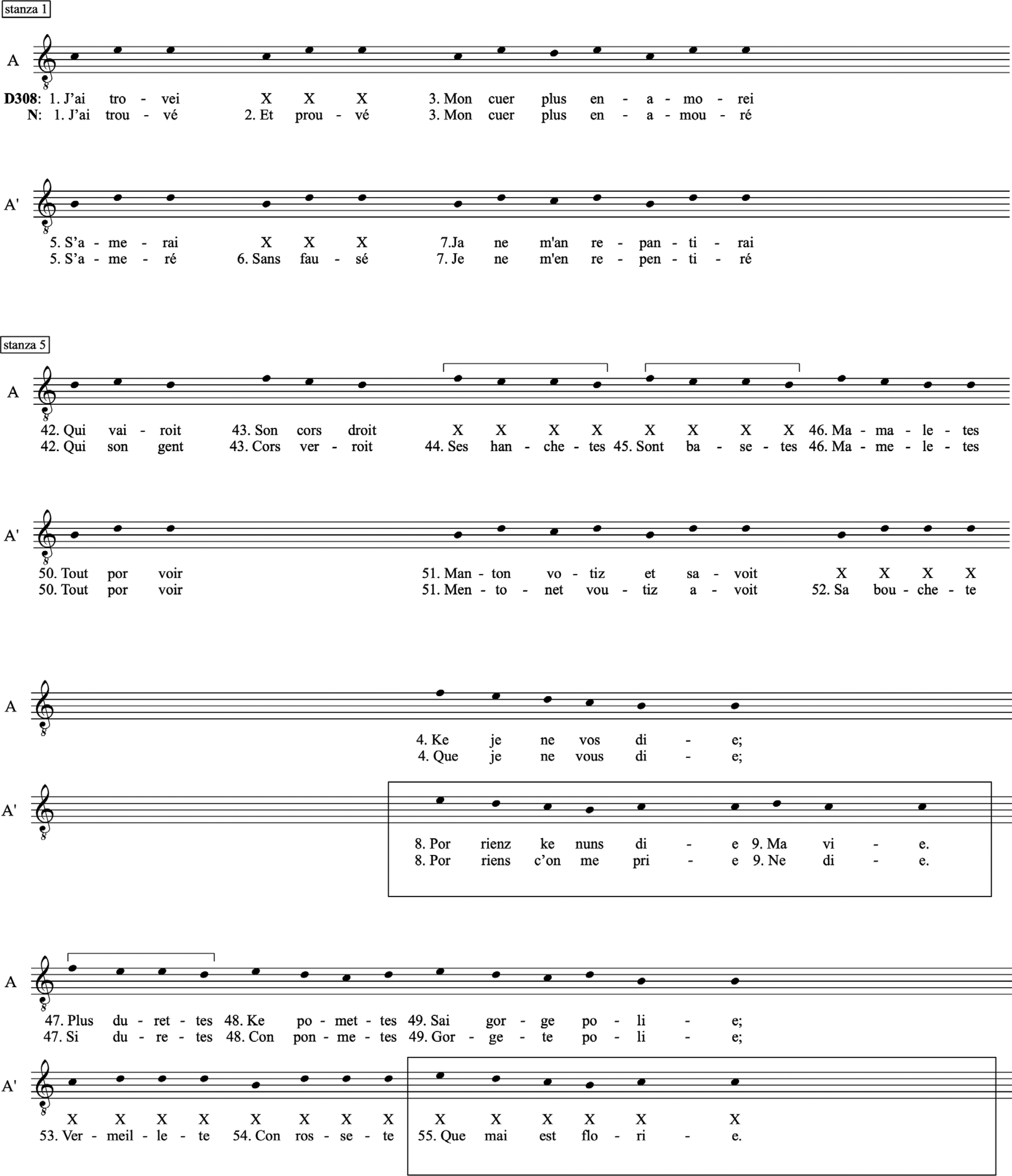

Example 2. B sections of stanzas 1 and 5.

For the purposes of the analysis that follows, I consider the song to have six stanzas (Table 2): my stanzas 1, 2, 4 and 5 are all signalled by capital letters in D308 (at lines 1, 18, 36 and 42); my stanza 3 is picked out by a gilded letter in N; and my final stanza (starting at line 69), while a point not marked visually in either manuscript, is marked musically by being an almost direct repeat of stanza 3.

Table 2. Diagnosis of the stanzaic structure (cadence formula in bold)

a Possibly short by a two–syllable paroxytonic line rhyming ‘–ie’.

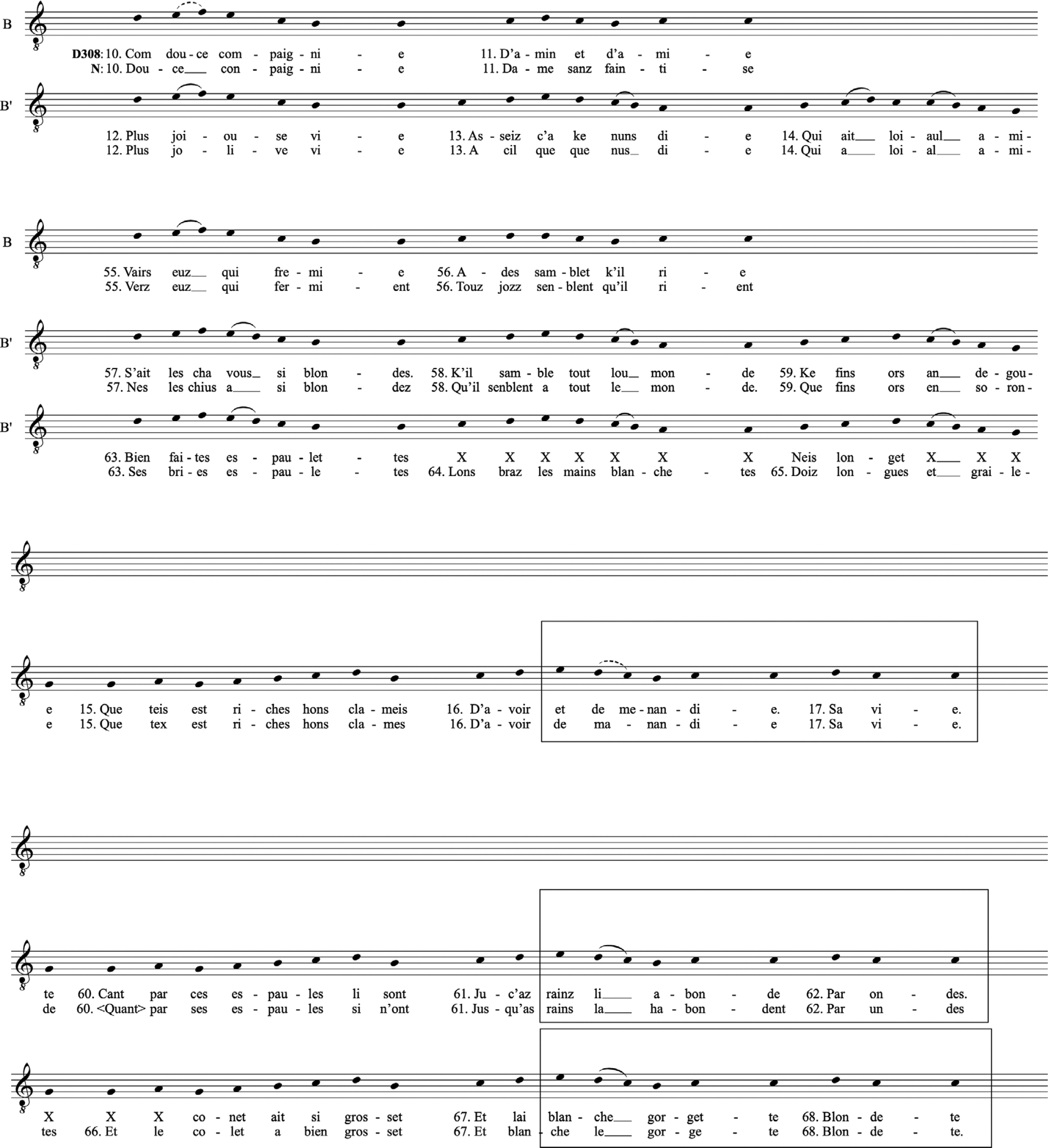

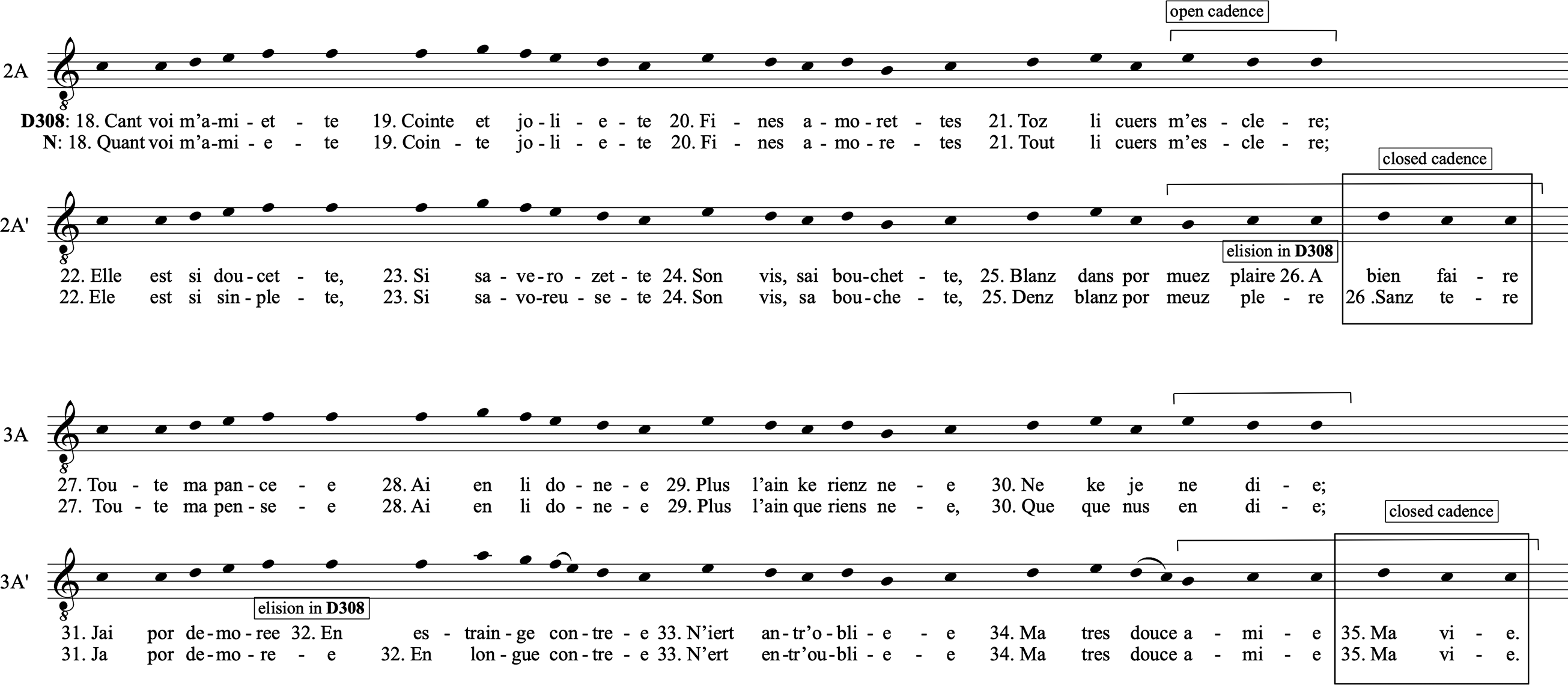

Example 3. Double versicle structure of stanzas 2 and 3.

These six stanzas yield three different poetico-musical structures. Broadly, the music of the first and fourth stanzas is reprised for the last two respectively, that is, stanza 5 is similar to stanza 1, and stanza 6 to stanza 4. In both cases, the melody undergoes amplification and extension in both music and poetry the second time through, albeit more obviously in N’s copy. As mentioned earlier, the music of stanza 2 is almost directly repeated for stanza 3. All stanzas have internal repetition structures too, with a very tight presentation of tonal space based on c, and a repeated cadential formula driven by a short-line with a paroxytonic rhyme (usually the rhyme ‘-ie’) that is found in all stanzas and was noted by all earlier commentators (shown in bold in Table 2).Footnote 46 Stanzas 2 and 3 are double-versicle structures; stanzas 4 and 6 are two similar stanzas of a through-composed stanzaic type. All four of those stanzas (i.e., both types) are formal types that are also found in the estampies of D308.Footnote 47 Stanzas 1 and 5, however, have a form not seen in the estampie. Arguably, this form might be considered an earlier version of the fourteenth-century balade form, with two distinct musical sections A and B, both repeated, the second repeated twice in stanza 5. The closed ending of the B section is similar to the closed ending of the A section, creating what scholars of later formes fixes musical balades (such as those by Machaut) typically term a ‘musical rhyme’.

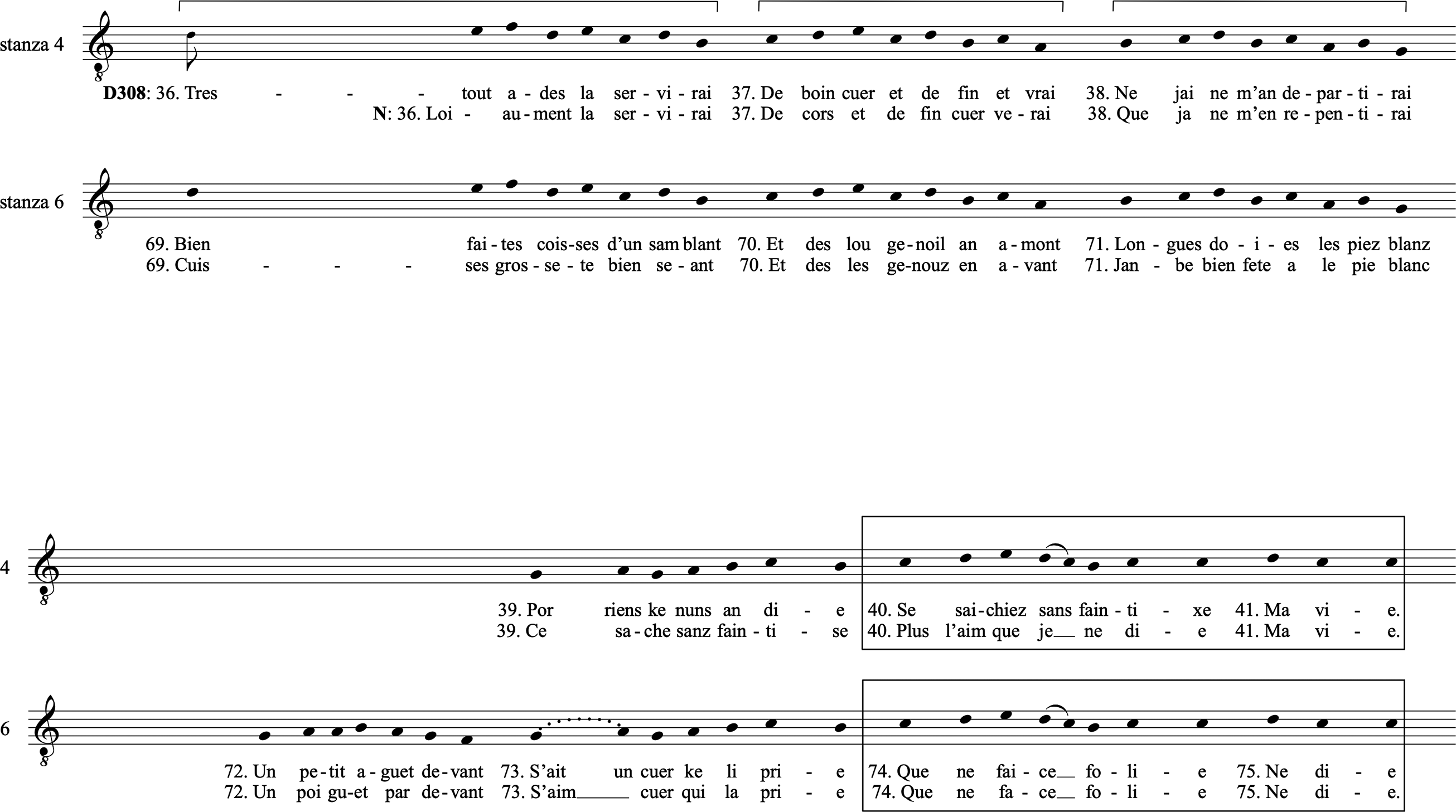

Example 4. Stanzaic structures of stanzas 4 and 6.

The variants between N and D308, once one considers the music that accompanies them in N, are suggestive of how scribal exigencies interact with the musico-poetic formal aspects to present particular possibilities, which in turn may lead to certain kinds of errors.Footnote 48 Diagnosing scribal practice is, as usual, hampered by a lack of knowledge of the source materials for surviving chansonniers.Footnote 49 It is impossible to know, for example, whether the scribe of D308 copied from a notated version or a text-only prompt, a difference that would have radically affected the visual aspect of the song’s layout. Some of the differences between the two surviving copies can be further informed by looking at the way that the repeated structures between similar stanzas – and between similar repeated parts within those stanzas – carry errors and omissions. I now treat the formal types in the order the song presents them.

The balade-type stanzas, 1 and 5

The first stanza of the song is in the musical form AA′BB′, a form akin to that seen later in the duplex balade. The copy in N has more text than that in D308, with lines 2 and 6 present in N but not in D308. Either these two lines are erroneously missing in D308 or they were creatively added to the song by the time N was copied. Importantly, these two lines occur in musically similar parts of the repeated A section, which might suggest, for example, a very concise exemplar with some kind of text-stacked notation from which the second layer of underlaid text has been lost. That is, if the exemplar or working copy had line 2 underlaid to line 1 (since they have identical melodies), and line 6 to line 5 (ditto), the loss of the second row of text would be cognate with the similar kinds of losses seen more extensively in repeated A sections in later fourteenth-century balades.Footnote 50 I would find this possibility more compelling, however, if the A′ section were a direct repeat of A, so that the text was already potentially doubly stacked, with these short internal repeats creating a short opening of quadruple text-stacking.Footnote 51 But the A′ melody as it stands is a tone lower than A so a basic double text stack would not work. And while this difference in pitch could be an error, it makes sense as a kind of extended ‘tonal answer’ to the ‘question’ posed in A, an answer confirmed by the extension of A′ to the cadence (boxed in Example 1). Moreover, as will be seen later, comparison with the same idea of an opening question and answer in stanza 5 suggests that the difference in pitch level between the melodies of A and A′ is intentional. Rather than a lost stacked text, then, D308 is either simply in error (albeit with two errors that coincidentally occur in suspiciously similar positions in the poetic structure), or it represents a legitimate – likely earlier – state of the song that does not yet include what later became lines 2 and 6 in stanza 1 of N. This latter hypothesis is plausible insofar as the absence of lines 2 and 6 in stanza 1 does not imperil the stanza’s verbal sense. The addition of these two lines is also a direct repetition of the melodic material, which would be easy to do: it might have been added to give a better sense of musico-poetic balance to the opening of the song (effectively lengthening short lines through repetition), and therefore have arisen from a later expansion of the form.Footnote 52 Equally, their repetition might have been omitted in a kind of haplography – whether aural/performative or scribal – but one that attends to a need to remove them in both corresponding places. Personally, I find the argument for expansion and the creation of balance easier to believe.

A comparison with the ‘same’ musical material in the cognate stanza 5 (the third and fourth systems in Example 1) is additionally instructive. The second line of the A′ material in stanza 5 – which is otherwise identical for its first two musical phrases with the A′ material of stanza 1 – is absent, even in N. Gennrich posits a missing line here, and if the idea of a missing three-syllable line between lines 50 and 51 of stanza 5 is accepted, the first thirteen syllables/notes of the A′ sections of stanzas 1 and 5 could be identical. But the equivalent first thirteen syllables of the A sections of these two stanzas differ a great deal in music and poetry. First, the opening couplet of three-syllable oxytonic lines 42 and 43 is deprived of its rhyme in N, with its sense units reversed compared to the rhymed version in D308, and with the non-rhyming synonym ‘gent’ substituted for the rhyming ‘droit’. The music, too, is not the repetitive figure found in the equivalent places in stanza 1 (A and A′, lines 1–2 and 5–6) and (partially) stanza 5 (A′, line 50). And immediately after stanza 5’s first two lines, N’s version breaks out into a repetitive series of three-syllable, paroxytonic (thus four-note) lines (44, 45, 46, 47 and 48), rather than having, as in stanza 1, longer, heptasyllabic, oxytonic lines (3 and 7). In N’s presentation, there are five lines (lines 44–48) using the ‘-ete’ rhyme, with a minimally varied repetitive figure descending from f to d. Three of these repeat the middle e (see bracketed lines 44, 45 and 47 in Example 1); one (line 46) repeats the d, and the last (line 48) falls below the d to c, pre-empting the melody of line 49, which as a cognate of line 4 (stanza 1) gets us ‘back in’ to the open cadence at the end of the A section the first time through.

The second time through, stanza 5 and stanza 1 are more similar, that is, the A′ material in stanza 5 is much closer to the A′ material in stanza 1 than are the two A sections of these two stanzas to each other. It seems plausible, therefore, that there is a line missing between lines 50 and 51, which would be in the same position as lines 2 and 6 in stanza 1, both of which are missing in D308 but present in N. Of all Gennrich’s posited missing lines, therefore, this is the candidate which seems most convincing. The current line 51, however, is the sort of heptasyllabic oxytonic line that rhymes with line 50 which might be expected here by comparison with lines 3 and 7 (but not lines 44–45).Footnote 53

After line 51, however, the same paroxytonic lines rhyming with ‘-ete’ get going as in stanza 5’s A section, although in A′ there are only three of these, because line 51 effectively takes the musico-poetic space of lines 44–5. In the A′ version, the melodic presentation is different from the A section, with all three lines (52–4) having the same insistent figure (b–d–d–d), an intensified version of the motive that opens the A′ section in stanzas 1 and 5. While the lead into the cadence in line 55 is identical to the melody of line 8, there is no equivalent in stanza 5 of line 9, in either music or poetry. Again, Gennrich assumes a missing line, which also seems highly possible in this case.Footnote 54 Nonetheless, it should be noted that none of the ‘-ete’ rhymes feature in D308’s presentation of the text, which lacks lines 52–5 entirely.

In the B section, too, stanza 5 expands the musico-poetic aspects of stanza 1. Stanza 1’s B section is bipartite, BB′. The first time through, B is a pair of phrases that match as question and answer, with open and closed terminations respectively (b, then c). The second time through, the B′ version not only takes a different tonal track in the second line (line 13 descending to a rather than, as in line 11, ascending to the closed tone c), but is then expanded by an extensive ‘second-time ending’ longer than the initial part (Example 2, lines 14–17). Overall, the phrases of B′ end successively on b, a, G, b, c, and then c again using the same cadential formula in lines 16–17 that ended A′ (lines 8–9).

D308’s text for Stanza 1’s B section is basically the same as N’s, without any missing lines. But the small differences that do exist are instructive. D308 has hypermetrical syllables in lines 10 and 16. In both cases these lines, which host the first two 2-note ligatures of the piece, have sufficient pitches that they would be able to accommodate these extra syllables (see dashed slurs in Example 2), which makes the version in D308 musically possible, if not ‘correct’ from a philological point of view. Moreover, accommodating the additional syllable in line 10 in this way causes it to resemble the text-setting in the two B′ parts of the cognate stanza 5 (lines 57 and 63), where the second and third pitches (e–f) are set syllabically.

In the cognate stanza 5 overall, the form of Stanza 1’s B section is expanded by the repeat of B′, giving an overall musical form of BB′B′. The first B melody has one change from the version in the opening stanza, which is the repetition of d in line 56 of stanza 5. This repetition accommodates the fact that this line is a six-syllable line compared to the five syllables in the equivalent line of stanza 1 (line 11); in a sense, this addition of a pitch at the start of the second phrase of the melody has already been heard in the B′ section of stanza 1 (line 13).

In the two B′ sections of stanza 5 (which are identical with each other), there are two minor differences compared with Stanza 1’s sole B′ section:

-

1. In the first phrase of each B′ section (lines 57 and 63) there is a melisma on the fourth syllable, filling in what was an e–c leap in stanza 1 (both B and B′) to give ed–c. This change may be designed to balance a feature already mentioned above: the syllabic setting of the second and third notes in this phrase (e–f) compared to their melismatic use for a single syllable (syllable 2) in stanza 5’s B section (line 55) and in both B and B′ sections of stanza 1 (lines 10 and 12, except implicitly in the D308 version, which has an extra syllable in line 10). Lines 10 (except in D308), 12 and 55 are paroxytonic five-syllable lines, whereas lines 57 and 63 (the lines that open B′ and its repeat in stanza 5) are paroxytonic six-syllable lines.

-

2. There is the removal of one melisma in B′ which tweaks the pitch content: lines 59 and 65 open syllabically with b–c–d compared to line 14’s opening of b–cd–c.

The textual omissions found in D308 resurface in stanza 5’s repeated B′ section, with all of line 64, the second half of line 65 and the first half of line 66 missing compared to N. The text here enumerates the lady’s physical qualities, so the sense is not much affected by D308’s relative abbreviation. What this means for the performance of D308’s version is hard to assess. In effect, there is a single line of nine syllables after line 63 and before line 67 when the B′ section available in that stretch sets lines of six and eight syllables. Stanza 1’s line 14 is the only line with nine available pitches since it repeats the c in the middle of the line compared to the same pitch string in stanza 5’s lines 59 and 65. If D308’s text represents a possible rendering, the repeat of B′ in stanza 5 could be brought closer to the melody heard in stanza 1 using line 14’s melody for the text that survives after line 63 and before line 67. This solution seems unlikely because the repeated pitches that terminate lines here are used for paroxytonic rhymes, which these nine syllables in D308 do not have. It is noticeable that in lacking all of line 64 and the end of line 65, D308 omits both lines that have the ‘-ete’ rhyme. This is a rhyme that, as discussed earlier, it similarly omits in stanza 5’s A section compared to the version in N. Does this suggest that the repeat of B′ in stanza 5 was originally more abbreviated, less literal, merely an extended version of a single B′ section so that, like stanza 1, this half of stanza 5 was also a double-versicle structure with an extended second-time ending? Or was it always full, with the missing parts in D308 merely errors? N’s version, if it represents an expanded version, with the music lengthened by repeated melodic motives setting easily supplied ‘-ete’ rhymes, could have been made as a lengthier presentation of the lady’s diminutive (pastourelle-type) qualities. Melodically, the first missing line in D308 (line 64) starts identically (c–d–e) with the first full musico-poetic line that is present after the omissions (line 67), and the melody with the bit of text that D308 skips directly to (line 65) starts almost the same, only a tone lower, b–c–d. It seems entirely possible that some kind of complex eye-skips might have taken place, especially if the scribe of D308 was copying from a musically notated exemplar where the similar melodic shape perhaps confused the text scribe.Footnote 55

Overall, the evidence from the two balade-type stanzas has been used here in several different ways. First, the intra-stanza repeats have shown a base line for a melody with a repetition structure that can be expanded. Then an inter-stanzaic comparison between how musical material from stanza 1 is repeated in expanded form in stanza 5 has offered potential insight into how this material is worked and re-worked, what might remain fixed and what might be more moveable. This comparison hints at the various ways in which these seldom literate forms were flexible, might bear a level of informality and musico-poetic accommodation, and might be tweaked (to greater or lesser degrees) in certain specific performances.Footnote 56 Then the evidence of the different verbal text in D308, in conjunction with the field of possibilities for working out the melodic form, prompts further considerations of all of these levels of flexibility. The evidence from the balade-type stanzas 1 and 5 suggest that melodies can accommodate an extra syllable with an extra note, especially at the start of a line as a ‘pick up’, can fill in a leap with a melisma, and that such an addition might serve to balance the loss of a melisma in the accommodation of an extra syllable when an extra note is less feasible (as, for instance, midline).

Double versicle stanzas (estampie type Ic): stanzas 2 and 3

The second and third stanzas of the song are almost identical and each presents a more regular, lai-like double-versicle structure, with open and closed endings, corresponding to the kind of structure seen in a subtype (1c) of the estampie (Example 3).Footnote 57 Each stanza here has two rhymes, both paroxytonic. Stanza 2 has the ‘-ete’ rhyme that features later in stanza 5 (discussed earlier) with ‘-ere’/‘-aire’; stanza 3 has ‘-ee’ and the ‘-ie’ rhyme that is strongly associated with the two-syllable/three-note (2′b) closed cadence lines of stanzas 1 and 5, which are identical with the closed cadences in both these two stanzas too (boxed in Example 3).

Textual variants mean that lines 26 and 32 in D308 have an extra syllable. While these could simply be errors, each hypermetrical line begins with a vowel when the line immediately before ends with an unstressed ‘-e’ from a paroxytonic rhyme. Thus the music of N (where the poetry is not hypermetrical) can readily accommodate D308’s hypermetrical lines if the singer simply makes an elision at the end of poetic lines 25 and 31 (labelled in Example 3). Such elision of the final syllable of a rhyme word at the end of a line is not a standard practice in the highly literate lyrics of trouvères, where the formal constraints of the stanza’s line boundaries are observed regularly. It is, however, a feature sometimes found in motet voices, the poetry of which is irregular, not usually stanzaic, and seemingly answers to the higher formal demands of the music.Footnote 58 D308’s version, therefore, to which the music would fit only by sacrificing the poetic regularity of this otherwise quite regular stanza, may be considered less ‘literate’ and perhaps closer to an earlier, performative version that treats lines 25–6 as effectively a single line, and lines 31–2 as another single line. Moreover, the hypermetrical line 32 coincides with a unique rise to the upper boundary pitch aa in the melodic setting, a point at which D308 has the phrase ‘En estrainge contrée’ (‘in a strange land’). This kind of stock phrase likely represents a more casual, perhaps improvised version of this line’s poetry, with the upper pitch insouciantly depicting the geographic distance of the je from his beloved by means of an extension of the vocal range. The melody of the other three presentations (lines 19, 23 and 28) is restored in time for the rhyme by the simple expedient of a 2-note ligature on ‘con-’ of ‘contrée’, which enables the singer to get down from the upper aa to the c at the end of the line in five syllables, despite having to sing six pitches. The more literate version in N retains this melodic variation, but the poetry is brought into line with the ‘proper’ (literate) syllable count, using the slightly more awkward phrase ‘En longue contrée’ (‘in a far off land’).

Stanzaic stanzas (estampie type II)

Stanzas 4 and 6, while roughly similar to each other, are, unlike the other stanzas, through-composed, corresponding to a minority type of estampie form (type II).Footnote 59 Instead of direct internal repetition, each stanza opens with a particularly striking linear intervallic pattern, essentially a three-member descending sequence (see the three square brackets in Example 4). Also unlike the other four stanzas, the two manuscript copies transmit exactly the same number of lines, although N has a single syllable fewer in two places (lines 36 and 73). While it might appear that D308 has another hypermetrical variant in stanza 4’s first line (line 36), I would argue that it is more likely that N is hypometrical and D308’s reading is better. Even though D308, which has the ‘correct’ number of syllables, has no melody, the similarity between stanzas 4 and 6 allows a solution to be proposed. In stanza 6, the three lines at the opening of the stanza (lines 69–71) make an exact descending linear intervallic pattern. Compared to stanza 6’s line 69, line 36 – the line which is a syllable shorter in N’s stanza 4 – merely lacks the initial d. If stanza 4, like stanza 6, originally opened with three octosyllabic lines (as it does in D308), the cognate melody of stanza 6 would serve equally for an octosyllabic line 36 (and D308’s text ‘Tres’ would work, too, even with N’s slightly different wording).Footnote 60 The text of D308 would fit exactly as it stands once this opening note is added (shown with an editorially supplied small quaver d in Example 4), and the three-member linear intervallic pattern of three lines rhyming 8a 8a 8a would be preserved.

The second half of both of these stanzas terminates with the cadential closed formula seen throughout the entire song. But compared to stanza 4, stanza 6 has a further poetic line in this second part. In stanza 6 the first half of the stanza (8a 8a 8a) is followed by 7a 6′b 6′b 2′b, the last two lines of which, underlined here, are the song’s pervasive cadential formula.Footnote 61 Typically, Gennrich assumes that these two stanzas would have been exactly similar and thus posits a missing line in both copies of stanza 4, between lines 38 and 39. As presented musically in stanza 6, the additional line (72) offers something new: repeated pitches and a descent to the lowest pitch of the stanza (F), an extension that arguably gathers musico-poetic tension for the final push to the familiar material and cadence of lines 73–5. If Gennrich’s correction is right, this phrase would already have been heard in stanza 4 in his putative missing line between 38 and 39, so this tension would not be reserved for the final stanza of the song, weakening its effect. Gennrich’s supposition would, however, have the merit of making the two halves of the stanzaic structure more balanced in both stanzas, with the octosyllabic first three lines answered by three hepta-neumatic lines plus the 2′b ‘cap’ of the closed cadence.Footnote 62

Conclusion

So what kind of song is La note Martinet – D308’s ninth pastourelle – in genre, form and type? The melody’s insistent, tonally clear, repeated-note terminations of lines and the syllabic nature of the textual delivery would make it easily something that could accompany a dance with fiddle and/or tabor. Spanke, Meyer and Billy all think it is in D308’s collection of pastourelles by mistake, preferring to see it as an estampie.Footnote 63 The texted estampie itself, however, is nearly as poorly attested in the written and musically notated record as the nota and equally poorly understood: it has a multiplicity of formal types, including (as seen in RS474) types where the form changes in the course of a single song.Footnote 64 Given, too, that D308 explicitly has a subsection of estampies, the question of why this song was placed in the pastourelles, and not in the estampies as it could have been, persists. I remain unpersuaded by easy allegations that this is an oversight caused by scribal laxity, not least because the first six genre subsections of D308 are particularly clearly planned, attested in internal tables of contents and are each especially tightly focused in their opening dozen or so songs. Moreover, the pastourelle subsection of D308 only appears to contain items that do not accord with our modern definition of the medieval pastourelle because that definition is based on a priori assumptions about what the genre contains. I have argued that we should expand our understanding of the pastourelle genre to view it as a kind of physical scene in which some type of embodied interaction accompanies an often fairly forthright delineation of carnal desire.Footnote 65 In this sense RS474 surely provides pastourelle-type enticement and perhaps brings us close to the sort of song that might have accompanied the robardel described in The Tournament at Chauvency, with which RS474 shares an emphasis on the thighs, breasts and body of the lady who is addressed by the je. While in RS474 she is not specifically named as a shepherdess, such identification would fit the register of the lexis. The estampies in D308’s estampie subsection, by contrast, are generally more elevated in tone in their poetry, and none of them exhibits the extent of formal variety between stanzas found in RS474, even in those where the form changes within the song.Footnote 66 No surviving estampie combines in the same song, as RS474 does, the formal type Ic with the stanzaic type (type II). In fact, none of the I subtypes is ever combined with type II. In addition, the extended duplex balade-type forms of stanzas 1 and 5 are unlike the forms seen in any of the surviving estampies.

The less fully worked out formal properties of the version of RS474 in D308 might stem from an earlier version of the song than that seen in N. If they are not merely errors, the route between the two surviving versions might imply a longer back-history of the song that places it closer to the sort of semi-improvised dance scenes of entertainment at court that are described in fictionalised accounts such as that of Chauvency. This greater informality might explain why the rather general term ‘note’ (i.e., tune) was used in this case, and also why so few of these ‘notes’ are found in the musically notated written record. The first phrase, in particular – two pitches a third apart – with its immediate repeat down a step, is highly memorable, especially with what I suspect are the additions of lines 2 and 6 in the version represented in N.Footnote 67 The unique preservation of the music in N occurs in what may be a specifically customised part of an otherwise fairly standard set of contents, which was placed in a final gathering of the book, where it shares folios with at least one other genre that is less frequently copied, notated and specifically labelled (namely, the motet enté).Footnote 68 The music of the melodies of all stanzas adds additional support to the idea of a song developed through semi-improvised, danced performances, possibly by an instrumentalist busking sung text while also playing: the piece is almost entirely syllabic, full of joyful melodic sequences and the repetition of short motives, terminating in the same repeated-note cadence for all the paroxytonic rhyme endings. While such a statement must necessarily remain speculative, it is possible that Marty’s tune, RS474, offers a tantalising glimpse of a larger vibrant repertoire of emotionally and erotically charged songs, which played an important role in court life throughout the later Middle Ages.

Appendix: a comparison of the two texts of RS474