Studying the varied abilities of followers to hold their political leaders accountable across diverse regime types is a central topic in the field of comparative politics (DeScioli and Bokemper, Reference DeScioli and Bokemper2019; Bøggild and Petersen, Reference Bøggild, Petersen, Todd and Ranald2015). This line of research draws heavily upon evolutionary theory, which suggests that in order to manage intragroup coordination challenges in ancestral societies, followers needed to attend to cues signaling exploitative leadership behavior (Cosmides, Reference Cosmides1989). Such cues include whether political leaders adhere to procedural fairness criteria during public decision-making such as displaying responsiveness to allow followers a voice, or acting impartially without considering personal interests.

Representing this latest evolutionary turn in the study of political behavior, Bøggild (Reference Bøggild2020) demonstrates that the average citizen in democratic societies like the United States and Denmark cannot reliably distinguish political leaders based on their ideological orientations. This finding aligns with existing political science insights on partisanship and ideology, which emphasize the fact that citizens often have difficulty in correctly locating party candidates on policy issues and ideological scales (e.g., Carpini and Keeter, Reference Carpini and Keeter1996; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). Rather, Bøggild discovers that in these democracies, citizens judge their leaders based on how fairly they govern, particularly whether they make decisions without personal motives and stay attuned to the needs and opinions of the public. This result, based on experiments utilizing the Wason selection task (WST), proposes that the human brain is inherently equipped with a built-in mechanism for detecting dishonesty, which helps citizens identify self-interested political leaders who violate social contracts and social exchange rules—in order for group living to offer survival advantages in ancestral societies, members had to tackle challenges such as coordinating collective efforts while preventing free-riding (Popper and Castelnovo, Reference Popper and Castelnovo2018).

Indeed, current research clearly demonstrates that voters in democracies are often swift to spot when politicians act out of self-interest and violate social expectations. However, mass democracies, where politicians present a number of options for voters to pick from, have only emerged in the past five centuries (Diamond, Reference Diamond1997). In autocracies where such accountability systems are lacking, we test if citizens possess similar ability to hold political leaders accountable for violating procedural fairness.

Democratic regimes allow people to choose their political leaders and grant them prestige (like political or social status) when those leaders serve public interests, such as by winning elections (Price and Van Vugt, Reference Price and Van Vugt2014). In contrast, autocratic regimes like China lack these democratic processes, often resulting in leaders being imposed on the population. Therefore, a critical element of leader–follower reciprocity—where followers elect and bestow prestige on leaders for delivering group benefits—can function differently across regime types. Consequently, a pressing call for political studies is to broaden the empirical investigation of followership dynamics beyond democratic settings: little is known about how citizens in autocracies evaluate politicians when the latter cheat.

In fact, psychological experiments backing the idea that humans have a specialized ability to detect cheaters have been conducted in various developed societies, such as the U.S., Hong Kong, the U.K., and Germany. While each study offers valuable insights, the evidence for this hypothesis becomes more compelling when tested across a diverse range of populations, not just those from democratic nations. Notably, research in evolutionary psychology has already shown that people from the Shiwiar community in the Ecuadorian Amazon were just as skilled at detecting cheaters as Harvard University students (Sugiyama et al., Reference Sugiyama, Tooby and Cosmides2002). Such studies inspire us to further test whether individuals residing in democratic and autocratic regimes possess the same cognitive ability to monitor social exchange. Thus, we investigate if Chinese citizens would display similar nuanced reasoning patterns as other populations do, in spite of stark differences in social and political contexts. After all, as Weber (Reference Weber1949) argues, “For a social science theory to be correct, it must also be valid for the Chinese” (p.58).

Accordingly, we conducted eight WST experiments in two studies (involving a total of 821 citizen subjects) to test such evolutionary propositions in China. The WST offers a standardized way to assess individuals’ cognitive ability in recognizing violations of various types of rules. Our findings confirm that an evolved cheater-detection ability is common to humankind and across regime types. In particular, our two studies reveal that while Chinese citizens struggle to identify rule violations in most scenarios, their performance increases markedly when the rules involve social exchange or when leaders violate exchange norms to pursue personal gain.

Our findings based on evolutionary psychology thus enrich the comparative politics literature, showing that even in autocracies with little political accountability, citizens retain a cognitive system to track self-serving actions of leaders as this universal cheater-detection system—rooted in our evolutionary history—continues to help individuals identify leaders who act out of self-interest and pose a threat to collective welfare.

1. An evolutionary turn for political science: cheater-detection in varied regimes

Evolutionary theorists hint that throughout human evolutionary history, our ancestors constantly endured survival challenges, prompting natural selection to shape the human mind with specialized psychological systems designed to address specific adaptive problems, particularly those arising during social cooperation aimed at ensuring individual and group survival (Petersen, Reference Petersen2012): To better gauge mechanisms sustaining social cooperation, scholars like Cosmides and Tooby (Reference Cosmides and Tooby1992) integrate studies of the ecology of hunger-gatherer life with results from evolutionary game theory to develop a social contract theory. This theory posits that social exchange is found in every human society, and historically, present among hominins as early as two million years ago. It tells us that humans were never under any evolutionary pressure to understand how electrons behave or how the universe began. Such knowledge did not enhance reproductive success. In contrast, to survive, humans became inclined to trade personal resources for state-provided benefits and to relinquish certain privileges to a subgroup of leaders under the framework of a social contract.

In other words, evolutionary psychology argues that to survive, humans need to become skilled cooperators with cognitive abilities that enable them to trade resources, form alliances, choose quality exchange partners (including leaders), and keep an eye out for cheaters during such coordination processes when working together (Alford and Hibbing, Reference Alford and Hibbing2004; Cosmides et al., Reference Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby2010). What this implies is that for social cooperation to function properly, humans must collaborate on the condition that others honor their commitments by adhering to social rules and agreements without cheating. Specifically, in leader–follower relationships, followers reward leaders who make decisions for the group with benefits such as resources and status. In return, they expect leaders to use their authority and status to make choices that serve the group’s interests. However, a persistent risk exists: leaders might exploit their position, using their power to serve their own interests at the expense of the group, thus violating the social contract. This risk is significant, and as an adaptive response, it is likely that humans have evolved to be highly attuned to any signs of exploitation or self-serving behavior by those in positions of authority (Boehm, Reference Boehm2000).

The challenge lies in the fact that identifying cheating leaders is not straightforward, as collective decision-makings entail complex outcomes and span over different time horizons (i.e., to balance followers’ short-term costs versus their long-term benefits). This is why relevant political science research (e.g., Bøggild and Petersen, Reference Bøggild, Petersen, Todd and Ranald2015) has increasingly focused on followers’ attention to procedural fairness as a proxy for assessing leaders’ prosocial dispositions. Procedural fairness typically concerns whether and how leaders respond to followers’ input—particularly their “voice”—in collective decision-making processes. For instance, using the WST, Bøggild (Reference Bøggild2020) finds that followers are very capable of identifying political leaders in breach of procedural fairness during collective decision-making involving social exchange rules—he reveals that American and Danish citizens react with hostility towards political leaders who seem self-interested. Likewise, others (e.g., Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) reveal that American citizens’ frustration with their government is less about bad decisions but more to do with decisions made for political leaders’ self-serving purposes. This is why some argue that if political processes could prevent leaders from acting out of self-interest, citizens would be less engaged in politics. As Alford and Hibbing (Alford and Hibbing, Reference Alford and Hibbing2004: 713) put it, for most people, political involvement stems not from a wish to be heard, but from a need to restrain the power of others.

Nevertheless, most current studies on evolved followership have been conducted with WEIRD (i.e., white, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) populations (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010). We aim to test whether these findings hold universally, as cultures and societies often respond differently when their respected leaders violate their own principles or act in self-serving ways. In some regimes, such violations are met with much less disapproval than in others, as shown in Effron et al.’s (Reference Effron, Markus and Jackman2018) comparative study of 48 nations. For example, Dong et al. (Reference Dong, van Prooijen and Wu2022) reveal that leadership dishonesty, such as discrepancies between words and actions, is condemned less harshly in China than in the U.S. Extending such research that examines cultural differences on how status-related transgressions are viewed, scholars have found that the social basis for leadership status varies significantly across different political systems and cultures. While there is considerable research on how status is earned and recognized (e.g., Anderson and Kilduff, Reference Anderson and Kilduff2009), much less attention has been given to how people from different cultures evaluate high-status individuals when they transgress.

In short, the idea that followers assess group leaders based on their perception of procedural fairness is one of the most well-established discoveries in social psychology (see a review by van den Bos et al., Reference van den Bos, Wilke and Lind1998). And it has been well tested in various leader–follower scenarios, inclusive of several managerial and legal contexts across different culture types (see a review by Bøggild and Petersen, Reference Bøggild, Petersen, Todd and Ranald2015). Specifically, followers’ focus on procedural fairness has been confirmed in the political realm when citizens assess politicians, with these evaluations influencing voters across varied segments and party lines (Tyler, Reference Tyler1994; Ulbig, Reference Ulbig2008). Our study builds on this extensive body of research to test whether followers’ attention to procedural fairness is accurate, as no existing research has explored how reliably followers in China perceive and judge politicians’ compliance with procedural fairness. In fact, there remains limited understanding of how citizens in autocratic regimes detect political leaders who violate procedural norms or engage in dishonest behavior.

2. Testing the cheater-detection hypothesis in China

Our ancestors faced numerous challenges critical for survival and reproduction, such as hunting, assessing resources, and cooperating with others. This paper explores social exchange and conditional cooperation as a key area of evolutionary development. Social exchange is a long-standing characteristic of humans, where one agrees to offer a benefit based on certain conditions—namely, the other person fulfilling their part of the deal. In the context of conditional cooperation, “cheaters” are those who break the social contract by accepting the benefit without fulfilling their end of the agreement.

Accordingly, evolutionary psychologists like Leda Cosmides and John Tooby have employed WST experiments to showcase that our brain contains specialized social exchange algorithms to detect such cheaters. Likewise, Bøggild (Reference Bøggild2020) claims that this cheater-detection ability can be naturally extended to leader–follower relationships during citizens’ evaluation of leaders, as he uses the WST to demonstrate that citizens base their trust in leaders on how fair the decision-making process seems, specifically whether leaders follow social contract principles, such as making unbiased policies and being receptive to public opinions. In contrast, his paper also reveals that in democracies, people have limited capacity to assess leaders for their ideological stances on political issues, as mass democracies have only existed for 500 years. Going beyond democracies, we aim to retest Bøggild’s cheater-detection hypothesis in China’s context:

H1: Followers have an inherent ability that helps them detect leaders who break social contract rules.

Certainly, the idea that our minds have specific mechanisms for detecting cheaters has been the subject of considerable debate (e.g., see Beaman, Reference Beaman2002). There are varied competing theories about social exchange relationships, but most stem from the core assumption in traditional behavioral sciences—the “blank slate” perspective. This view suggests that humans have a broad, general cognitive ability (like intelligence, reasoning skills, and rationality) that accounts for human thought and behavior in most situations: Humans’ general intelligence enables them to identify, gauge, or deduce advantageous actions. This idea has been key to most neuroscientists, psychologists, and social scientists when they study human behavior, though it has seldom been tested through direct empirical evidence, unlike theories in fields like physics or biology.

Consequently, we recognize the possibility of a general rationality hypothesis (H2), which suggests that people utilize their general intelligence (i.e., smartness or rationality) to find out cheating leaders. This means that a cheater-detection system may not exist, as people rather draw on a general-purpose cognitive system of intelligence to facilitate different forms of problem solving including during social exchange (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, DeYoung and Reis2011):

H2: Humans possess a natural ability, a general rationality system rather than a cheater-detection system, to facilitate diverse forms of problem solving.

Relatedly, we may also consider another alternative explanation by Johnson-Laird et al. (Johnson‐Laird et al., Reference Johnson‐Laird, Legrenzi and Legrenzi1972: 385) who argue that participants’ performance on the WSTs depends on whether researchers make the task feel relevant to participants by presenting problems that they can relate to from their day-to-day lives. This familiarity hypothesis(H3) suggests that people reason more effectively about any rule—whether or not it involves social contracts—when they have previously encountered similar scenarios in their own lives. Simply put, H3 implies that there is no specialized cheater-detection mechanism for spotting leaders’ actions. Instead, our brain has a learning capacity that helps individuals absorb information from their surroundings, and remember and recognize familiar patterns:

H3: Humans solve various versions of the Wason selection task depending on their familiarity with the rules presented in the task through past experience and a judgement of relevance, rather than on a specialized cheater-detection system.

Lastly, for H4, we would retest Cosmides et al. (Reference Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby2010)’s finding that the cheater-detection system operates with precision, specifically identifying violations of social exchange rules when these violations benefit the violators. The benefit thesis(H4) posits that a key feature distinguishing social contract rules is the presence of an offered benefit in the exchange, which defines a cheater as someone who accepts this benefit without fulfilling their obligations (Cosmides et al., Reference Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby2010). Essentially, H4 will help us test whether people’s ability to detect cheaters is heightened when the violation provides an explicit benefit to the violator, and if the absence of such a benefit changes their detection response. In short, H4 focuses on comparing participants’ performance based on whether the rule violation offers a benefit to the potential cheater.

H4: Followers possess a built-in cheater-detection system that becomes more active when leaders break social contract rules to gain the benefits those rules allocate.

3. Research design and data

The WST is an extensively studied task in psychology (Wason, Reference Wason1968): Its strength allows researchers to subtly change the conditional rule given to participants, providing a clear measure of their cognitive abilities when dealing with different types of rules. The rule can be modified to reflect various conditions—such as being indicative, precautionary, or a social contract—allowing for the testing of various reasoning theories.

In a standard WST, neutral elements like letters and numbers are used. For example, a rule might state, “If there’s an A on one side of the card, there must be a 7 on the other side.” This type of indicative rule could also be framed in more relatable terms, such as: “If someone is a sociologist, they enjoy doing social theory.” Each card in the task represents a different case, such as “sociologist” (P), “chemist” (Not-P), “enjoys doing social theory” (Q), and “does not enjoy doing social theory” (Not-Q). The participant can only see one side of each card and is asked to choose which cards need to be flipped over to check if the rule holds true. In one variant of the WST, rules related to social contracts or obligations are used, such as: “To drink alcohol, a person must be at least 18 years old” (Griggs and Cox, Reference Griggs and Cox1982). The correct answer in these cases would be to flip over the P and Not-Q cards, and none of the others. However, Johnson-Laird and Wason (Reference Johnson-Laird and Wason1970) found that 96% of participants in standard WSTs chose an incorrect combination of cards, often picking the P and Q cards instead. On the other hand, Cheng and Holyoak (Reference Cheng and Holyoak1985) observed that when the rule involved social obligations, correct responses (measured as “hit rate”) could reach 60%. This suggests that people are more likely to choose the P and Not-Q cards when the rule is framed in terms of a social contract. Essentially, in contexts entailing social or deontological duties, participants tend to reason more logically.

Why does this difference occur? Despite the progress since Wason’s seminal study, our understanding of the reasoning processes involved remains incomplete. This is reflected in the wide variety of theories proposed to explain the phenomena. A recent meta review of 228 WST studies (Ragni et al., Reference Ragni, Kola and Johnson-Laird2018) identified 16 different theories, each with a distinct approach (for a comprehensive review, see Evans, Reference Evans, Niall, Erica and David2016). Some of these theories focus on the processes involved (e.g., Relevance Theory; Sperber et al., Reference Sperber1995), while others propose intricate models of cognitive processing (e.g., Leighton and Dawson, Reference Leighton and Dawson2001).

One notable candidate theory is Cosmides’s (Reference Cosmides1989) evolutionary approach, which proposes that for cooperation to be stable and spread within a group, individuals must be able to identify those who exploit fairness in social interactions. This ability to detect cheaters is activated in situations where there is an exchange, a benefit, and the potential for cheating. Therefore, in the context of solving WSTs, the crucial insight is recognizing that someone might exploit the situation by reaping the benefits without fulfilling the required conditions.

Building on Cosmides’s insights, Bøggild (Reference Bøggild2020) concludes that his WST experiments demonstrate that citizens in democracies such as Denmark and the US can tap into their innate cheater-detection instincts to spot political leaders who break fundamental rules in decision-making processes (“the voice task”). This goes beyond their capacity to tackle other similar (logically equivalent) WST tests, such as those related to academic documents (“the student document task”) or political ideologies (“the ideology task”).

To examine such competing hypotheses using the WST, two studies were conducted among Chinese citizens: In Study 1, a total of 306 subjects (see their sample characteristics in Table 1, appendix) were randomly given one of the three WST tasks to complete (Figures 1–3), in order to test if their performance varied across them, and in particular, if they could identify political leaders who breach the standard of procedural fairness in group decision-making. Study 2 (Figures 1–3; Figures A and B, appendix) tested another 515 followers’ cheater-detection capacity to see if subjects’ (see sample characteristics in Table 3, appendix) ability to detect procedural fairness violations will decrease when political leaders do not get the benefits regulated by the conditional rule.

Figure 1. The student document task.

Figure 2. The ideology task.

Figure 3. The voice (cheater) task.

Figure 1 presents “the student document task” as our first WST. Subjects are asked to imagine they have been employed as a secretary at a local high school and their job is to make sure student documents follow a specific conditional rule: “If a student achieves a grade of ‘101’, their document should be marked with code ‘M’” (i.e., if P, then Q). Subjects are subsequently requested to identify any documents that break this rule, with four cards presented, each representing one of the categories: P (grade 101), Not-P (grade 103), Q (code M), and Not-Q (code F). The right response is to flip over the cards showing P and Not-Q. Essentially, this task functions as a baseline condition, designed to assess whether Chinese participants can detect violations of conditional rules in contexts that lack social interaction or exchange—providing a control for reasoning that is not linked to social contract detection.

Figure 2 presents our second WST: “The ideology task.” Here, subjects, who are instructed to envision themselves as journalists, face a conditional rule in their coverage of local village affairs: “If a village head decides to implement a spending cut on social welfare, then he/she is fiscally conservative.” Here, the background is set in village communal decision-making, whereby local village residents actively engage in self-governance: These villages in the region are led by their own elected councils consisting of five to eight representatives. Representatives are chosen by villagers through a democratic process. The head of the council, aka “village head,” is responsible for managing village economic issues, including the setting of village budgets and the use of village revenues. In general, if a village head decides to cut social welfare spending, then he/she is categorized as conservative, not liberal. However, subjects are also told that a fellow journalist believes that some village leaders do not fit this rule. Subjects are then presented with four cards as shown, and asked to identify which cards should be flipped to check for violations of the conditional rule. This task, while similar in structure to the first, differs in that it does not involve a context of social exchange or the risk of cheating.

It is notable that Wu and Meng (Reference Wu and Meng2023) have demonstrated that political preferences in China are organized around two axes: The first division centers on differing views about the state’s involvement in the economy, while the second reflects a clash between authoritarian and democratic perspectives. Further, as existing research (e.g., Wu, Reference Wu2023) shows, though many Chinese are open to positioning themselves on the political spectrum, their placements are influenced by biases in perception. The terms “left” and “right” lack clear, consistent meanings, and their associated ideological symbols are limited in salience and familiarity, unlike in many democracies. Thus, our ideology scenario task only takes on ideology’s economic dimension, focusing on public leaders’ positions on social welfare spending. Building on the work by Dalen (Reference Dalen2022) that reveals that support among Chinese citizens for government-provided social welfare has grown significantly since 2004, our experimental design classifies local leaders who cut down on social welfare spending as being “fiscally conservative.” This terminology was selected on the assumption that it reflects an intuitively accessible ideological category for our subjects within the Chinese socio-political context.Footnote 1

Figure 3 presents our third WST: “The voice task (cheater task).” Subjects are asked to investigate local village self-governance in a region with a conditional rule: “If a village head decides to implement a spending cut on social welfare, then he/she must first hold a village public meeting.” The background is similar to the ideology task’s but we add that according to a village collective-decision rule, if a village head decides to adjust village spending ratios, he/she must first hold a village public meeting for villagers to express their ideas and concerns on this decision. Subjects are placed in the role of a journalist, with a working hypothesis that not all village heads have adhered to this procedural requirement. Their task is to examine whether village leaders in the region complied with the rule—namely, whether those who implemented welfare cuts followed the mandated process of public consultation.

Technically, unlike those in the previous tasks, this rule in Figure 3 suggests that leaders must fulfill certain prerequisites before taking action. This establishes a context of social exchange, where followers are expected to interpret the situation as a social contract: Political leaders who attempt to influence the community—such as by reducing social welfare spending—are obligated to engage with the community’s concerns through a public meeting. Failure to do so constitutes a violation of procedural fairness and should activate cheater-detection mechanisms in subjects. Background-wise, since the early 2000s, China has rolled out various platforms for village deliberation, such as village discussion forums, a “village council” system, and assemblies open to all villagers. By 2012, over two million villagers had engaged in assessing the performance of village leaders through democratic evaluations, according to the State Council Information Office (Tong and He, Reference Tong and He2018). He et al. (Reference He, Baogang, Michael and James2021) further note that village deliberative democracy has advanced, particularly since 2005. For example, in the 2016 national survey, 36% of villagers reported that key decisions were made in all-villager meetings, a notable increase from 30.7% in 2005. This suggests that village public meetings have become a stable fixture in Chinese political life. Martinez-Bravo et al. (Reference Martinez-Bravo, Padró I Miquel and Qian2022) offer an underlying explanation for this trend, arguing that even authoritarian regimes have incentives to strengthen local accountability mechanisms. By leveraging villagers’ informational advantage, central authorities can better monitor local officials and maintain effective governance. Amid such political backdrops, we argue that the subjects under study can realistically relate to this local governance task scenario.

Figure A (in the appendix) presents our fourth WST: “The benefit task.” As Cosmides et al. (Reference Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby2010) suggest, social exchange is favored by evolutionary pressures whenever one organism (the provider) can manipulate the behavior of another organism (the recipient) to benefit itself, by tying the recipient’s access to a rationed benefit to their compliance with certain actions. That is, for a situation to qualify as a social exchange, a key criterion is the presence of a benefit being rationed or allocated. Thus, similar to the voice task, subjects are tasked with identifying if the same conditional rule has been violated. But we add a “benefit” element into this task scenario suggesting that there are many reported cases where some village heads had misused the village revenues saved from the welfare spending cuts for their own personal benefits. So, acting as a journalist, the subject will investigate whether the following village heads (as represented by the four cards) in the region under study adhere to the same conditional rule.

Figure B (in the appendix) presents our fifth WST: “The no-benefit task.” This task mirrors the voice task, with a crucial modification: It alters the scenario’s context by removing any potential benefits associated with the leader’s decision-making. In this case, subjects are asked to envision themselves as newly appointed assistants to a village leader, and are responsible for organizing public meetings and hearings related to community decision-making. But since no one in the village head’s office knows if public hearings are mandatory, subjects are tasked with investigating the practices of other villages to gauge what village heads typically do. At the same time, subjects are told that spending cuts would not benefit the village heads because all the saved amounts from the village public coffers in the region will be automatically transferred back to the central government by the end of each calendar month. This setting enables us to test whether individuals’ cheater-detection capacity is still triggered in the absence of personal gain for the rule violator (e.g., the village heads).

Crucially, the five tasks are functionally identical: Each presents a conditional “If P, then Q” structure, the same set of instructions, and four cards that correspond to the same logical categories. In every task, selecting the cards that verify the antecedent (P) and negate the consequent (Not-Q) is the correct approach for solving the WST.

Data: To test our hypotheses, we use the Chinese equivalent of Mechanical Turk (WJX: https://www.wjx.cn) for both studies. It is China’s largest online labor market for gathering crowd-sourced data, after having served the academic and advertising communities with 13 billion successful feedbacks. Usually, WJX users submit survey experiment requests to recruit human participants registered on the platform to complete tasks. This approach offers a quick solution to common challenges faced by social scientists, such as survey overload, low participation rates, and the high costs of recruiting respondents. On WJX’s platform, in 2022 for Study 1, we recruited 306 citizen subjects, who were randomly divided into three WSTs (each was attended by more than 100 subjects). In 2023 for Study 2, we recruited another 515 citizen subjects and randomly divided them into five WSTs.

For our cheater-detection hypothesis (H1) to be proved, if citizen subjects can rely on their innate cheater-detection abilities to spot political leaders who deliver decisions without giving citizens a say in village public meetings, then the WST hit rate for the voice task should be relatively high. However, the success (hit) rates for the ideology and student document tasks are likely to be much lower, as there is no built-in mechanism to detect violations of informal, non-contractual rules where breaches of social duties do not matter. Alternatively, the general rationality hypothesis (H2) predicts comparable hit rates across all tasks, implying that participants rely primarily on their general cognitive abilities—such as logical reasoning or intelligence—rather than any specialized detection system. A third possibility, the familiarity hypothesis (H3), posits that participants' judgments are influenced by how familiar or relevant the scenario appears to them; since the unfamiliar student document task is very different to the other tasks, which represent well-understood conditional rules, we can anticipate similar performance across them, with a marked decline in the student document task. Lastly, to test H4 (the benefit hypothesis), we check whether there is a significant difference between subjects’ hit rates on the voice, the benefit, and the no-benefit tasks. In short, our research design is summarized in Table 1, which shows how each hypothesis can be proved, clarifying the logic of pairwise comparisons of group hit rates performed via t-tests,Footnote 2 as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Table 1. Summary of hypotheses and tasks

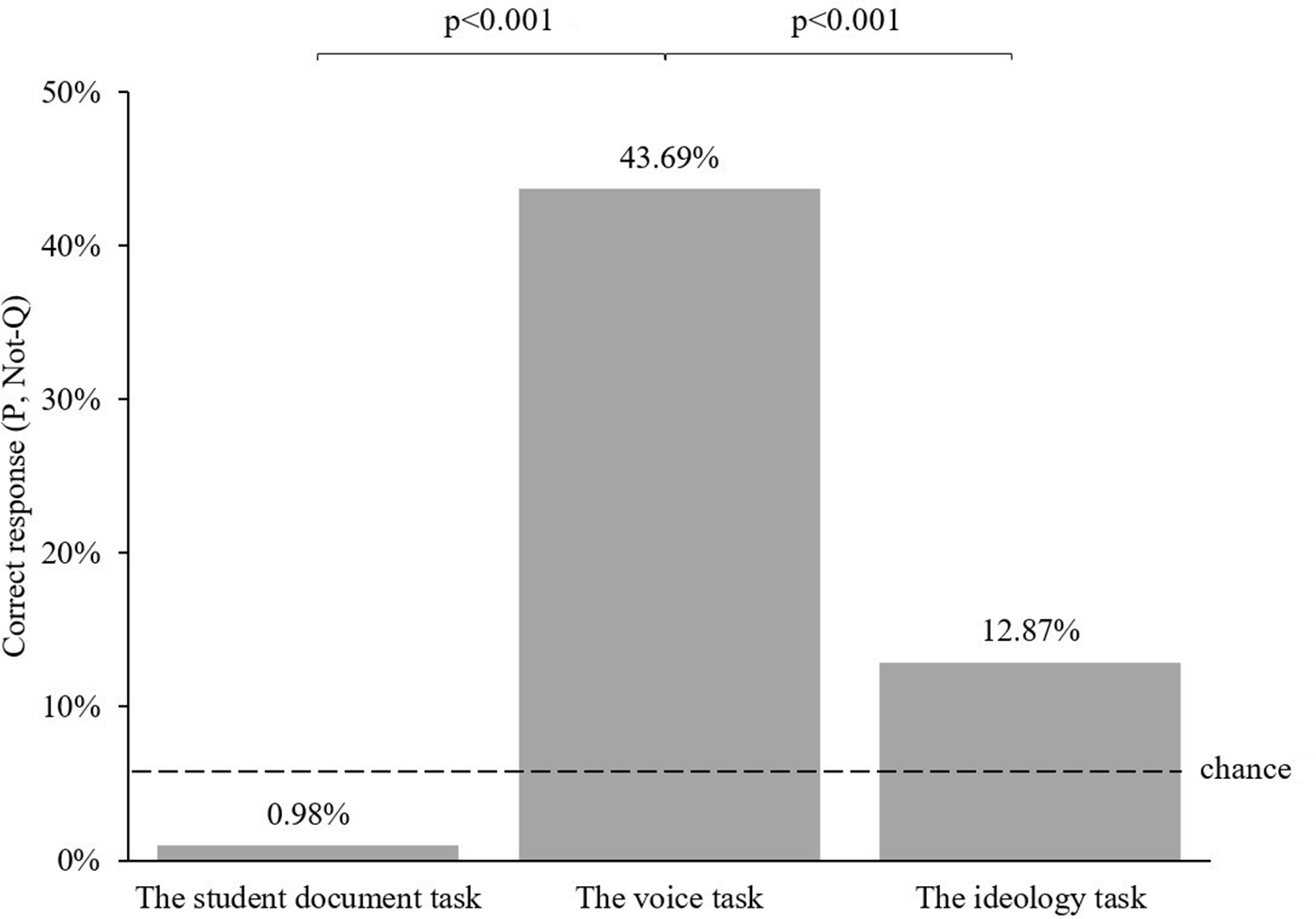

Figure 4. Percentage correct P, Not-Q responses across the three Wason selection tasks for study 1.

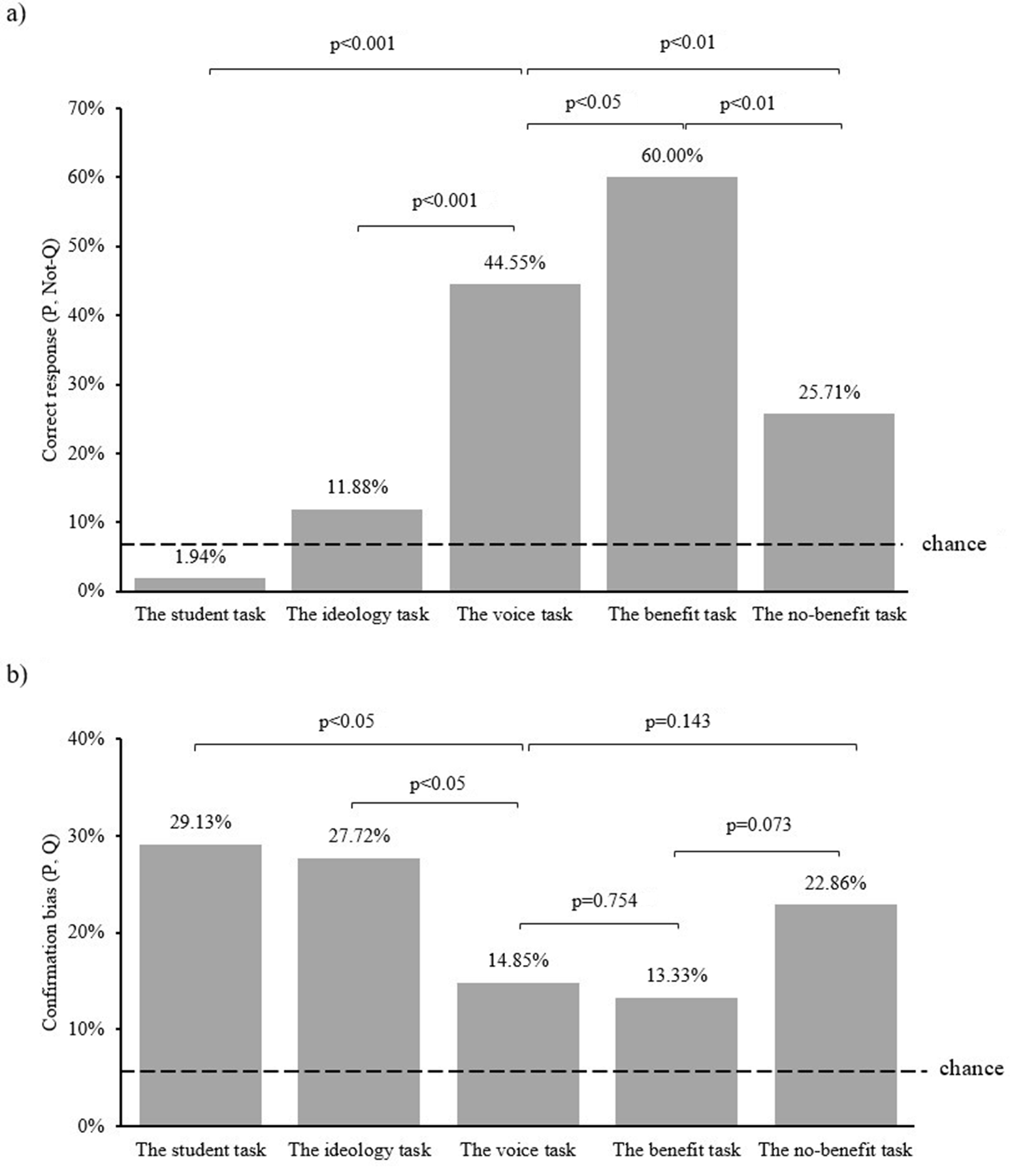

Figure 5. Percentage correct P, Not-Q responses (panel a) and incorrect P, Q responses (panel b) across the five Wason selection tasks for study 2.

4. Results: cheater-detection in Chinese politics

4.1. Study 1

Figure 4 entails a striking display of the proportion of correct answers across the triad of tasks in Study 1. Most notably, the voice task emerges as a standout, with participants achieving impressively high hit rates—far outshining the other two tasks. This dramatic contrast suggests that the human ability to detect cheating leaders is not a byproduct of everyday rational thinking, but rather, something deeper—an evolved, finely-tuned instinct that transcends baseline cognition (i.e., contradicting H2). Otherwise, the hit rates across these tasks should be roughly similar when people draw on the same general intelligence factor (Jensen, Reference Jensen1999) to solve all cognitive tasks.

Moreover, if the familiarity hypothesis (H3) holds, then given that both the voice and ideology tasks rely on familiar conditional rules, we would reasonably predict similar levels of performance on these two tasks. In contrast, the student document task—built on unfamiliar rules—should yield lower hit rates, regardless of whether any of these scenarios involve the detection of potential cheaters.

However, the hit rates across the tasks show that this is not the case, helping us reject H3 because subjects performed markedly better on the voice task than on the ideology task. This suggests that subjects managed to produce high hit rates on the voice task not because they had become familiar with the rule through cued relevance. As a robustness check, we use a political sophistication index (following Zaller’s methodology, Reference Zaller1992) to test whether the likelihood of a right answer in the voice task and the ideology task is related to people’s political knowledge and interest: The results (Table 2 in the appendix) are insignificant, meaning that people’s ability to identify the right answers in both scenarios operates independently of their prior political knowledge or familiarity with such rules. In other words, the hit rates are not driven by political experience or the perceived realism of the scenarios.Footnote 3 Such findings are not surprising because scholars already show that familiarity of scenario context is irrelevant to hit rates: Cosmides (Reference Cosmides1989) showed that participants could reason effectively even when the social contract scenario was entirely unfamiliar—like “if you tattoo your face, I will reward you with cassava root”—an alien scenario no one has likely encountered. This result is not due to learned experience, but rather points to a deep-rooted, evolved feature of the human mind: A built-in mechanism for spotting cheaters in social exchanges, one that emerges very early—even by the age of three (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Núñez and Brett2001).

In short, confirming H1, we find that the presence of a potential cheater increases the hit rate on the voice task as subjects produce significantly more correct responses (43.69%), compared to a mere 0.98% on the student document task and 12.87% on the ideology task, after accounting for education, age, occupation and gender (see Table 2 in the appendix).

4.2. Study 2

To further assess the validity of H1, in Study 2 (Figure 5, Panel a) with a different sample in a different year, we again find that subjects perform significantly well when a task involves a social contract.Footnote 4 Turning to H4, we find that a scenario change from the voice task (hit rate = 44.55%) to the benefit task (hit rate = 60%) causes a significant rise in correct responses (i.e., a 15.45% increase from the voice task hit rate, which is statistically significant: p < 0.05). Likewise, when shifting from the voice task to the no-benefit task, the impact is unmistakable—performance plunges from 44.55% to just 25.71%. This stark 18.84% drop reveals that stripping away the element of personal gain dramatically undermines participants’ ability to identify the correct responses, highlighting just how crucial perceived benefit is to cognitive performance in these tasks. Such findings support H4: Subjects show a heightened sensitivity to rule-breaking when political leaders bend decision-making rules—particularly when those leaders stand to gain from their cheating. To test the reliability of these findings, Dawson et al. (Reference Dawson, Gilovich and Regan2002) point out a critical flaw in how most people approach the WSTs: Instead of challenging the rule, they instinctively look for evidence that supports it. This reveals a deep-seated confirmation bias in human reasoning, where people tend to focus on verifying “if P, then Q” rather than actively seeking to falsify it.

Figure 5, Panel b, highlights how confirmation bias plays out across the various tasks in Study 2. Subjects showed a much lower tendency to search for evidence that supports a given rule in the voice (14.85%), benefit (13.33%), and no benefit (22.86%) tasks. In contrast, this bias was more pronounced in the student document (29.13%) and ideology (27.72%) tasks, where subjects were more inclined to seek rule-confirming examples. This significant difference in confirmation bias suggests that people become more alerted when WST tasks are embedded in social contract contexts.Footnote 5

Overall, our results confirm findings from the psychology literature that show that in tasks with social contract violations, people possess a cheater-detection system to infer contractual expectations: Similar to analysis by Cosmides et al. (Reference Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby2010) who revealed that when the benefit condition was removed in a social contract violation WST, people’s correct response dropped by about 20%, our results illustrate that in China’s context, people’s cheater-detection system is not specifically designed to detect breaches of social exchange rules when such violations do not benefit the violator.

5. Discussion

What do results across the tasks in two studies imply for studies of political leader–follower relations. From an evolutionary perspective, it is plausible that humans have developed sensitivity to two distinct behavioral patterns in potential allies or leaders: One marked by exploitation, where an individual accepts a benefit without returning the favor, and another characterized by reciprocal cooperation, where mutual exchanges of benefits occur over time. The findings from our experiments suggest that when political leaders violate procedural norms and stand to gain personally, followers are more likely to recognize and penalize such behavior, consistent with the logic of evolved cheater-detection systems. This finding builds on two central insights articulated by Cosmides and Tooby (Reference Cosmides and Tooby1992) and later expanded by Bøggild (Reference Bøggild2020) to back the idea that cheater-detection stems from a specialized evolutionary adaptation. First, they contend that this mechanism is universal—shared by all humans regardless of cultural background or political system. Second, they argue that it operates autonomously, functioning instinctively and without relying on general processing.

Our results further validate both insights in China’s autocratic context.

Regime variations: On their first point. Our findings provide empirical support from a non-Western, non-democratic context, lending strong cross-cultural validation to H1.

Initially, we suspect that given 5,000 years of continuous history and no single instance of democracy, compared to their Western counterparts, China’s citizens may possess different traits and cognitive tendencies during leader–follower interactions—Nathan and Shi (Reference Nathan and Shi1993) point to a revealing paradox in a 1990 survey: Although over half of Chinese respondents (55%) supported expanding democracy, an even greater proportion (76%) believed that such democracy should remain subordinate to the Communist Party. This tension remained evident decades later. In 2016, the Asian Barometer survey found that 76% of Chinese respondents viewed democracy as a viable solution to societal problems. Nonetheless, when asked to evaluate how democratic their own government is on a scale from one to ten, they assigned an average score of 6.5—surpassing the score given to Japan, a well-established democracy.Footnote 6 These findings raised the possibility that political culture or institutional context might condition the activation of cheater-detection mechanisms (Popper and Castelnovo, Reference Popper and Castelnovo2018).

Yet, our results challenge that expectation. Across two studies, we find consistent support for H1 and H4, suggesting that even in autocratic China, the human mind still reflects evolutionary adaptations tailored to survival challenges like social exchange. Among these is a highly specialized cheater-detection system—an innate cognitive mechanism finely tuned to spot violations in reciprocal interactions. Remarkably precise, this system stays dormant when faced with rules unrelated to social exchange and becomes less responsive in situations where the violator stands to gain nothing. Moreover, our findings reinforce and extend insights from political science. In democratic contexts, prior work has shown that citizens’ support for governance outcomes hinges significantly on procedural fairness (e.g., Rhodes-Purdy, Reference Rhodes-Purdy2021). Our study affirms that the importance of process-based legitimacy is not exclusive to democracies. In fact, existing political science literature has already shown that although the way a process is carried out plays a central role in shaping fairness perceptions within established democracies, the concept of “procedural fairness” is not confined to them. Research illustrates that this concept resonates beyond democratic borders. For example, Wilking (Reference Wilking2011), through experiments in both the U.S. and China, finds that how a decision is made shapes people’s sense of fairness, regardless of regimes. Similarly, Wilking and Zhang (Reference Wilking and Guan2018) use experiments to show that the procedural quality to nominate candidates in China’s village elections strongly influence how much citizens support the electoral process.

General processing: Rejections of H2 and H3 further strengthens the claim that the cheater-detection module operates independently of general cognitive processing and logical reasoning. Such results align with findings from the psychology literature: Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Núñez and Brett2001) reveal that humans at an early age can distinguish between social contracts and indicative rules (they indicate or describe a state of affairs). For instance, at age three, children show a sharp ability to recognize when someone gains a benefit through a social exchange but fails to uphold their end of the bargain. Yet, this cognitive skill does not transfer to those stimuli involving only indicative reasoning, as reflected by our ideology task.

Moreover, additional psychological research shows that the human ability to reason about social contracts can remain strong even when general logical thinking or cognitive ability is compromised. For example, people with schizophrenia typically perform poorly on standard tests of intellectual functioning. Yet studies reveal that their capacity to spot cheaters often remains unaffected (McKenna et al., Reference McKenna and Baddeley1995). In a study by Kornreich et al. (Reference Kornreich, Delle-Vigne and Brevers2017), 25 individuals with schizophrenia, 25 with depression, and 25 without mental illness were tested on reasoning using the WST across three types of rules: Precautionary rules, descriptive ones, and social contracts. While schizophrenia patients struggled across the board compared to the other groups, they performed notably better on tasks involving social contracts than on descriptive reasoning. These findings add weight to the idea from evolutionary theory that reasoning about social exchange is governed by a cognitive mechanism evolved specifically for that purpose.

Consistent with Bøggild’s (Reference Bøggild2020) observation that citizens in democratic societies often struggle to distinguish political leaders based on ideology, our findings suggest that Chinese citizens similarly lack the ability to identify leaders by their ideological stance. This finding aligns with research on political behavior that emphasizes that most citizens (in America) have difficulty correctly locating political parties and leaders on ideological terms (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), just as there is considerable debate over whether ideology is a weaker basis for political identity (e.g., see Malka and Lelkes, Reference Malka and Lelkes2010). Echoing Bøggild’s findings that citizens often find it difficult to grasp how a leader’s ideological beliefs influence their administrative choices and governing actions in America and Europe, our results raise fresh doubts over citizens’ ability to evaluate political leaders’ ideological orientations in China.

6. Conclusion

Cosmides and her colleagues emphasize that from an evolutionary perspective, social contract rules are fundamental to group life because they help mitigate the risk of leaders abusing their power for personal gain. Drawing on evolutionary theory, political science scholarship has long argued that governments—designed to deliver collective benefits—are rooted in this same idea of a social contract. Hobbes (Reference Hobbes1980) views peace as the ultimate public good, asserting that to avoid chaos, individuals surrender their personal authority to a central power, accepting the actions of rulers as their own in exchange for stability. Locke (Reference Locke1982), in contrast, envisions a more limited role for the government and its leaders, when such leaders are bound by the social contract to carry out essential duties, especially to resolve disputes.

This paper extends these classical insights by suggesting that modern citizens in democracies and autocracies alike possess a natural cheater-detection capacity to gauge whether political leaders have broken social contract rules. Our findings indicate that Chinese citizens, too, can employ this cheater-detection ability to assess whether political leaders follow fair decision-making practices—such as giving people a voice in collective choices—thereby gauging their commitment to procedural fairness.

Similarly, our results also enrich studies of political leadership and follower psychology, by pointing to evolutionary approaches (Laustsen and Petersen, Reference Laustsen and Petersen2015) as a useful framework to map out the cognitive abilities available to citizens when they act as followers to evaluate political leaders—existing political science work points to citizens’ mismatched abilities to reason about politics (for evidence, see Li et al., Reference Li, van Vugt and Colarelli2018). For instance, Hibbing and Alford (Reference Hibbing and Alford2004) argue that thriving within groups depends on people’s ability to detect when leaders act in their own interest. Yet, their experiments reveal something unexpected: If citizens believe the political system prevents leaders from exploiting their power for personal gain, they are remarkably willing to accept government decisions—even those that do not work in their favor.

This study furthers such work by adding that even when citizens struggle to differentiate political leaders based on ideology, they can still rely on a more reliable capacity to detect violations of procedural fairness. Here, evolutionary approaches could enable political scientists to see that people are wired to judge leaders based on cues that historically promoted group cohesion and survival (see Von Rueden and Van Vugt, Reference Von Rueden and Van Vugt2015). In much the same way, a social contract algorithm is seen as a universal cognitive tool essential to human cooperation and endurance.

But this is not the end of the story. Our results have several limitations that warrant future investigations. First, the external validity of our findings requires further scrutiny—while the WST is valuable for comparing how people think across various types of problems, it also places them in an artificial and highly simplified setting that does not fully reflect real-world decision-making. Incoming research should explore whether citizens actually apply logical rules to detect cheating by political leaders in real-life settings—such as within the public sector—and observe their behaviors across diverse regime types. Moreover, we should acknowledge that the WST does not capture a pure, standalone measure of people’s ability to detect cheaters. In the complex reality of everyday politics—where distrust runs high and cynicism is common—it is still an open question whether, and to what extent, this cheater-detection mechanism actually guides attention when competing with other biases or motivations. For instance, although the ideology task produces poor hit rates, future research may test what ordinary citizens are able to achieve in mundane settings when existing research (e.g., Carnes and Sadin, Reference Carnes and Sadin2018; Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Duell and Johannesson2019) reveals that citizens may use candidates’ socio-demographic attributes such as gender, age, race, class to infer their positions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10012. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OTTGKF.

Acknowledgement

We thank the editors and the reviewers for their insightful comments that significantly improved the paper. This work was supported by the Institute of Public Governance, Peking University, with grant number: YBXM202207.

Conflict of interest statement

The submission aligns with the journal’s ethics and integrity policies. And none of the contributing authors reports a conflict of interest.